The federal government pays benefits to coal miners affected by coal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP, commonly referred to as black lung disease) and other lung diseases linked to coal mining in cases where the responsible mine operators are not able to pay. Benefit payments and related administrative expenses are paid out of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. The primary source of revenue for the trust fund is an excise tax on coal produced and sold domestically. If excise tax revenue is not sufficient to finance Black Lung Program benefits, the trust fund may borrow from the general fund of the Treasury, which contains federal receipts not earmarked for a specific purpose.

For 2018, the tax rates on coal were $1.10 per ton of underground-mined coal or $0.55 per ton of surface-mined coal, limited to 4.4% of the sales price. Starting in 2019, under current law, these tax rates are $0.50 per ton of underground-mined coal or $0.25 per ton of surface-mined coal, limited to 2% of the sales price. This decline in the excise tax rates will likely put additional financial strain on a trust fund that already borrows from the general fund to meet obligations. The decline in domestic coal production, recent increases in the rate of CWP, and bankruptcies in the coal sector also contribute to the financial strain on the trust fund.1

This report provides background information and policy options to help inform the debate surrounding the coal excise tax rate, and other considerations related to the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. The report begins with an overview of the federal black lung program, providing information on black lung disease and benefits under the program. The report proceeds to examine Black Lung Disability Trust Fund revenues, focusing on the coal excise tax and its history. The report closes with a discussion of policy options, evaluating various revenue- and benefits-related policy options that could improve the fiscal outlook of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund.

Federal Black Lung Program

The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund is used to finance the payment of federal Black Lung Program benefits under Part C of the Black Lung Benefits Act (BLBA) when a responsible coal operator does not meet its obligations under the law to pay benefits.

Black Lung Disease

Coal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP, commonly referred to as black lung disease) is an interstitial lung disease caused by the inhalation of coal dust.2 Like in other types of pneumoconioses, the inhalation of coal dust results in the scarring of the lung tissue and affects the gas-exchanging ability of the lungs to remove carbon dioxide and take oxygen into the bloodstream.3 Exposure to coal dust over an extended period of time can lead to CWP and continued exposure can lead to the progression from the early stages of CWP referred to as "simple CWP," to more advanced stages of scarring referred to as "complicated CWP" or progressive massive fibrosis (PMF). There is no cure for CWP and PMF. CWP can lead to loss of lung function, the need for lung transplantation, and premature death. CWP can be identified by observing light spots, or opacities, in x-ray images of the lungs and can be classified using guidelines established by the International Labour Organization (ILO).4

Despite technological advances in mining dust control, mandatory chest x-rays for miners,5 free CWP surveillance offered to miners by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH),6 the enactment of numerous pieces of mine safety and health legislation,7 and the promulgation and enforcement of mine safety and health standards by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA),8 CWP persists in American coal miners, especially those in the Appalachian region. After reductions in rates of PMF in the 1990s, this advanced form of CWP has recently been found in Central Appalachia at rates not seen since the early 1970s.9 In 2017 researchers discovered, among coal miners mostly living in Kentucky and Virginia and served by three federally funded Black Lung Clinics in Virginia,10 what may be the largest cluster of PMF ever recorded.11

This cluster of miners with PMF includes a relatively high number of miners with less than 20 years of mining experience as well as cases of PMF in current miners. The occurrence of this advanced stage of CWP in short-tenured and current miners is noteworthy since MSHA standards require that any miner with evidence of CWP be given the option, without loss of compensation or other penalty, to work in an area of the mining operation in which the average concentration of coal dust in the air is continuously maintained at or below an established level that is lower than the permissible exposure level for all miners with the goal of preventing the progression of CWP.12

Federal Black Lung Program

The federal Black Lung Program was created in 1969 with the enactment of Title IV of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 (Coal Act, P.L. 91-173, later renamed the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 by P.L. 95-164). Section 401 of the Coal Act provides the congressional justification for the federal Black Lung Program and cites the lack of benefits for disability and death caused by CWP provided by existing state workers' compensation systems as justification for the creation of a federal program. This section also states that the program is intended to be a cooperative effort between the federal government and the states.

The Coal Act also established mandatory safety and health standards for coal mines, including standards limiting exposure of miners to coal dust and giving miners with CWP the option of being moved, without loss of compensation or penalty, to an area of the mine with lower dust concentrations. The Coal Act was later amended by the Black Lung Benefits Act of 1972 (BLBA, P.L. 92-303).

Part B

The Coal Act established Part B of the federal Black Lung Program to provide cash benefits to miners totally disabled due to CWP and to the survivors of miners who die from CWP.13 Part B only applies to cases filed on or before December 31, 1973. Part B benefits are paid out of general revenue and were initially administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA). Today, with the exception of a small number of pending appellate cases, Part B benefits are administered by the Department of Labor (DOL), Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP).

Part C

The Coal Act established Part C of the Federal Black Lung Program for cases filed after December 31, 1973, and was later amended by the BLBA. Under Part C of the BLBA, all claims for benefits for disability or death due to CWP are to be filed with each state's workers' compensation system, but only if such systems have been determined by DOL as providing benefits that are equivalent to or greater than the cash benefits provided by the federal government under Part B of the BLBA and the medical benefits provided to disabled longshore and harbor workers under the federal Longshore and Harbor Workers' Compensation Act (LHWCA).14 If a state's workers' compensation system is not determined by DOL to meet these standards, then Part C benefits are to be paid by the each miner's coal employer, or, if no such employer is available to pay benefits, by the federal government.

In 1973, Maryland, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia submitted their state workers' compensation laws to DOL for approval, but were denied.15 To date, no state workers' compensation system has been approved by DOL under Part C of the BLBA.

Operator Responsibility

Because no state's workers' compensation system has been determined to be sufficient to pay benefits under Part C, each operator of an underground coal mine is responsible for the payment of benefits to that operator's miners. Operators are required to provide for these benefits either by purchasing insurance for benefits or through self-insurance approved by DOL.

A self-insured operator is required to purchase an indemnity bond or provide another form of security (such as a deposit of negotiable securities in a Federal Reserve Bank or the establishment of a trust) in an amount specified by DOL. In order to be approved for self-insurance, federal regulations require that a mine operator have been in business for at least the three previous years and have average assets over the previous three years that exceed current liabilities by the sum of expected benefit payments and annual premiums on the indemnity bond.16

When a claim for benefits is approved, benefits are to be paid by the "responsible" operator, which is generally the last coal operator to employ the miner.17 If a company has acquired the assets of a mine operator, then that company is considered a "successor operator" and is responsible for the payment of claims related to the original operator.18

Federal Payment of Benefits and Expenses

The federal government pays benefits in cases in which the responsible operator no longer exists and has no successor operator, or is unable to pay benefits. The federal government pays benefits when an operator has not made payment within 30 days of a determination of eligibility or when benefits are otherwise due to be paid. Initially, under Part C of the Coal Act, these federal benefits were paid out of general revenue. However, pursuant to the Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-227), these benefits are now paid from the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund established by this law and primarily financed by an excise tax on coal. If a responsible operator can later be identified, the trust fund is authorized by law to seek to recover from this operator the amount of benefits paid by the trust fund and any interest earned on these amounts.

The trust fund is also used for the following federal Black Lung Program-related expenses:

- the payment of benefits for miners whose last coal mine employment was before January 1, 1970;

- reimbursement to the Treasury for the costs of Part C benefits paid from general revenue before April 1, 1978, for periods of benefit eligibility after January 1, 1974;

- the repayment and payment of interest on advances made from the general fund to the trust fund;

- the payment of administrative expenses related to Part C of the BLBA and the coal excise tax incurred after March 1, 1978; and

- the reimbursement of coal operators who paid Part C benefits before April 1, 1978, for miners whose last coal mine employment ended before January 1, 1970.19

Eligibility for Black Lung Benefits

A miner is eligible for benefits if that miner is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis arising out of coal mine employment. The survivors of a miner are eligible for benefits if the miner's death was due to pneumoconiosis arising out of coal mine employment.

Benefits are only available to miners and their survivors. The BLBA defines a miner as

any individual who works or has worked in or around a coal mine or coal preparation facility in the extraction or preparation of coal. Such term also includes an individual who works or has worked in coal mine construction or transportation in or around a coal mine, to the extent such individual was exposed to coal dust as a result of such employment.20

Thus, other workers who may be exposed to coal dust in their work, such as railroad workers or workers at coal-fired power plants are not eligible for benefits. Persons who live near coal mines or power plants are also not eligible for benefits even if they are exposed to coal dust. In addition, while a miner's family members may receive benefits as survivors and the number of family members can increase the amount of a miner's monthly benefits, family members may not claim benefits on their own due to exposure to coal dust in the home such as from cleaning the miner's soiled clothing.

The BLBA defines pneumoconiosis for the purposes of benefit eligibility as "a chronic dust disease of the lung and its sequelae, including respiratory and pulmonary impairments, arising out of coal mine employment."21 The BLBA directs the Secretary of Labor to develop, through regulations, standards for determining if a miner is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis or died due to pneumoconiosis.22

Clinical and Legal Pneumoconiosis

The federal Black Lung Program regulations provide that the definition of pneumoconiosis includes medical or "clinical" pneumoconiosis and statutory or "legal" pneumoconiosis. Clinical pneumoconiosis is defined as follows:

"Clinical pneumoconiosis" consists of those diseases recognized by the medical community as pneumoconioses, i.e., the conditions characterized by permanent deposition of substantial amounts of particulate matter in the lungs and the fibrotic reaction of the lung tissue to that deposition caused by dust exposure in coal mine employment. This definition includes, but is not limited to, coal workers' pneumoconiosis, anthracosilicosis, anthracosis, anthrosilicosis, massive pulmonary fibrosis, silicosis or silicotuberculosis, arising out of coal mine employment.23

Legal pneumoconiosis is defined as

any chronic lung disease or impairment and its sequelae arising out of coal mine employment. This definition includes, but is not limited to, any chronic restrictive or obstructive pulmonary disease arising out of coal mine employment.24

Through these definitions, DOL has established that benefits are available not just to miners with CWP, but also to those miners with other respiratory diseases arising out of coal mine employment such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) even though these diseases are not pneumoconioses and may be linked to other factors unrelated to exposure to coal dust such as cigarette smoking.25

Eligibility Presumptions

The BLBA contains five presumptions used to determine if a miner is eligible for black lung benefits.26 Three of these presumptions are "rebuttable," meaning that, in the absence of any contrary evidence, eligibility is presumed. One presumption is "irrebutable" and eligibility for Black Lung program benefits is established if the statutory requirements of the presumption are met. Three of these presumptions apply to current Black Lung Program claims while two apply only to cases filed before the end of 1981. Table 1 provides a summary of the following five presumptions provided by the BLBA.27

- 1. A rebuttable presumption that the pneumoconiosis of a miner who was employed in mining for at least 10 years was caused by his or her employment.

- 2. A rebuttable presumption that the death of a miner who worked in mining for at least 10 years and who died of any respirable disease, was due to pneumoconiosis. This presumption does not apply to claims filed on or after January 1, 1982, the effective date of the Black Lung Benefits Amendments of 1981 (P.L. 97-119).

- 3. An irrebuttable presumption that a miner with any chronic lung disease which meets certain statutory tests or diagnoses is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis or died due to pneumoconiosis.

- 4. A rebuttable presumption that a miner employed in mining for at least 15 years, and who has a chest x-ray that is interpreted as negative with respect to certain statutory standards but who has other evidence of a totally disabling respiratory or pulmonary impairment, is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis or died due to pneumoconiosis. This presumption may only be rebutted by the Secretary of Labor establishing that the miner does not or did not have pneumoconiosis or that the miner's respiratory or pulmonary impairment did not arise out of connection to mine employment.

- 5. A presumption that a miner who died on or before March 1, 1978, and who was employed in mining for at least 25 years before June 30, 1971, died due to pneumoconiosis, unless it is established that at the time of the miner's death, he or she was not at least partially disabled due to pneumoconiosis. This presumption does not apply to claims filed on or after June 29, 1982, which is 180 days after the effective date of the Black Lung Benefits Amendments of 1981. This presumption is not listed in the law as either rebuttable or irrebuttable.

Affordable Care Act Amendments

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (commonly referred to as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), P.L. 111-148) included two provisions that amended the BLBA to reinstate one of the eligibility presumptions and a provision affecting survivors' benefits. The effect of these changes was to increase the opportunity to establish eligibility through the statutory presumptions and make it easier for certain survivors to receive benefits.

Pursuant to Section 202(a) of the Black Lung Benefits Amendments of 1981, the fourth presumption did not apply to cases filed on or after January 1, 1982. Section 1556(a) of the ACA removed the prohibition on applying the fourth presumption to cases filed on or after January 1, 1982. It is expected that this ACA provision will increase the number of miners eligible for benefits.

The BLBA provides that, for Part C claims, the survivors of a miner who was determined to be eligible to receive benefits at the time of his or her death are not required to file new claims for benefits or revalidate any claim for benefits, thus permitting the payment of survivors' benefits in these cases even if the miner's death was not caused by pneumoconiosis.28 Pursuant to Section 203(a)(6) of the Black Lung Benefits Amendments of 1981, this provision did not apply to claims filed on or after January 1, 1982. Section 1556(b) of the ACA removed from this provision the exception for claims filed on or after January 1, 1982. It is expected that this ACA provision will increase the number of survivors eligible for benefits.

The amendments to the BLBA provided in Section 1556 of the ACA apply to any claims filed under Part B or C of the act after January 1, 2005, that were pending on or after March 23, 2010, the date of enactment of the ACA.

Table 1. Eligibility Presumptions Provided in the BLBA, as Amended by Section 1556 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

|

Presumption Numbera |

Type of Presumption |

Minimum Number of Years of Mine Employment |

Basic Presumption |

Exception |

|

1 |

Rebuttable |

10 |

If a miner has pneumoconiosis, then pneumoconiosis was caused by employment |

None |

|

2 |

Rebuttable |

10 |

If death was from respirable disease, then death was due to pneumoconiosis |

Does not apply to claims filed on or after January 1, 1982 |

|

3 |

Irrebuttable |

None |

If a miner has chronic dust disease of the lung which meets statutory standards, then he or she is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis or died due to pneumoconiosis |

None |

|

4 |

Rebuttable |

15 |

If a miner has negative chest roentgenogram, but has other evidence of respiratory or pulmonary impairment, then he or she is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis or died due to pneumoconiosis |

Noneb |

|

5 |

—c |

25, before June 30, 1971 |

If a miner died before March 1, 1978, then miner died due to pneumoconiosis, unless it is established that the miner did not have at least a partial disability due to pneumoconiosis at the time of death |

Does not apply to claims filed on or after June 29, 1982 |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

a. The presumption number corresponds to the paragraph number in Subsection (c) of Section 411 of the Black Lung Benefits Act [30 U.S.C. §921(c)] and listed in this report.

b. Prior to the enactment of the ACA, this presumption did not apply to claims filed on or after January 1, 1982.

c. This presumption is not listed in the law as either rebuttable or irrebuttable.

Black Lung Program Benefits

Medical Benefits

Eligible miners receiving benefits under Parts B and C are entitled to medical coverage for their pneumoconiosis and related disability. This medical coverage is provided at no cost to the miner and can generally be obtained from the miner's choice of medical providers.

Disability Benefits

Eligible miners are also entitled to cash disability benefits. The basic benefit rate is set at 37.5% of the basic pay rate at GS-2, Step 1, on the federal pay schedule without any locality adjustment.29 If the miner has one dependent (a spouse or minor child) the miner is eligible for a benefit of 150% of the basic benefit. A miner with two dependents is eligible for 175% of the basic benefit and a miner with three or more dependents is eligible for 200% of the basic benefit. Benefits may also be paid to the divorced spouse of a miner if the marriage lasted at least 10 years and the divorced spouse was dependent on the miner for at least half of the spouse's support at the time of the miner's disability. A child is considered a dependent until the child marries, or reaches age 18, unless the child is either disabled using the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) definition of disability or is under the age of 23 and a full-time student.30 The benefit rates are adjusted whenever there are changes to the federal employee pay schedules, but are not separately adjusted to reflect changes in the cost of living. Table 2 provides the benefit rates for 2019. Benefits are offset by state workers' compensation or other benefits paid on account of the miner's disability or death due to pneumoconiosis. Part C benefits, but not Part B benefits, are considered workers' compensation for the purposes of reducing a miner's SSDI benefits.31

|

Category |

Monthly Benefit Amount |

|

Claimant with no dependents |

$660.10 |

|

Claimant with one dependent |

$990.10 |

|

Claimant with two dependents |

$1,155,10 |

|

Claimant with three or more dependents |

$1,320.10 |

Source: Office of Worker's Compensation Programs (OWCP) website at https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dcmwc/regs/compliance/blbene.htm.

Notes: Benefits listed are for Part C claims, which are rounded up to the nearest 10 cents. Benefits for Part B claims are the same amount as for Part C, but rounded to the nearest dollar.

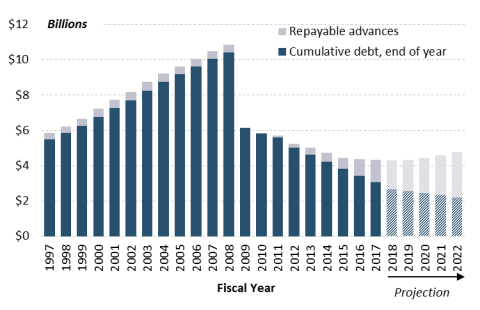

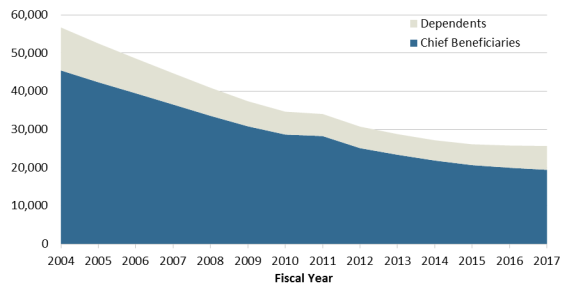

The total amount paid in cash disability benefits has fallen over time, as illustrated in Figure 1. More is paid in cash disability benefits than is paid in medical benefits.

|

Figure 1. Black Lung Part C Benefit Costs CY2005-CY2015 |

|

|

Source: Christopher F. McLaren and Marjorie L. Baldwin, Workers' Compensation: Benefits, Coverage, and Costs, (2015 Data), National Academy of Social Insurance, October 2017, p. 70, https://www.nasi.org/research/2017/report-workers%E2%80%99-compensation-benefits-coverage-costs-%E2%80%93-2015. |

Survivors' Benefits

Certain survivors of a miner whose death was due to pneumoconiosis are eligible for cash benefits. In the case of a surviving spouse or divorced spouse, the spouse's benefit is equal to what the miner would have received and is based on the number of dependents of the spouse as provided in Table 2. If there is no surviving spouse, then benefits are awarded to the surviving minor children in equal shares. If there are no surviving minor children, then benefits can be paid to the miner's dependent parents or dependent siblings. If there are no eligible survivors, no benefits are paid upon the miner's death and benefits do not go to the miner's estate or to any other person, including a person named by the miner in a will. The number of miners and survivors receiving benefits has declined over time, as illustrated in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2. Black Lung Part C Beneficiaries FY2004-FY2017 |

|

|

Source: Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP) website at https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dcmwc/statistics/PartsBandCBeneficiaries.htm. Note: Chief Beneficiary is either the miner or the miner's primary survivor. |

Black Lung Disability Trust Fund Revenues

The primary revenue source for the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund is a per-ton excise tax on coal. Historically, the coal excise tax has not generated enough revenue to meet the trust fund's obligations. Thus, additional funds have been provided from the general fund of the Treasury.32 The general fund includes governmental receipts not earmarked for a specific purpose, the proceeds of general borrowing, and is used for general governmental expenditures.

Excise Tax on Coal

Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 4121 imposes the black lung excise tax (BLET) on sales or use of domestically mined coal.33 Generally, a producer that sells the coal is liable for the tax. Producers that use their own domestically mined coal, such as integrated utilities or steel companies, are also liable for the tax.

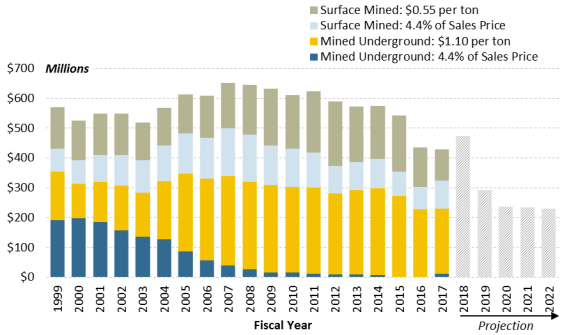

The tax rate depends on how coal is mined. Effective January 1, 2019, the tax on underground-mined coal is the lesser of (1) $0.50 per ton, or (2) 2% of the sale price. The tax on surface-mined coal is the lesser of (1) $0.25 per ton, or (2) 2% of the sales price. Before 2019, the tax rates were $1.10 per ton for coal from underground mines or $0.55 per ton for coal from surface mines, with the tax being no more than 4.4% of the sale price. In FY2017, $229 million was collected on coal mined underground (see Figure 3). Nearly all of this coal was taxed at the $1.10 per ton rate. In FY2017, $200 million was collected on surface-mined coal. Just over half of this coal was taxed at the $0.55 per ton rate, with the rest subject to the 4.4% of sales price maximum tax.

On January 1, 2019, the BLET rates declined to their current levels. The rates that took effect January 1, 2019, would also have taken effect if the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund had repaid, with interest, all amounts borrowed from the General Fund of the Treasury.

The tax is imposed on "coal from mines located in the United States" and does not apply to imported coal. The tax is designed to support the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund for domestic miners. Very little domestically consumed coal is imported.34

The BLET also does not apply to exported coal under the Export Clause of the United States Constitution.35 A credit or refund can be claimed if coal is taxed before it is exported.

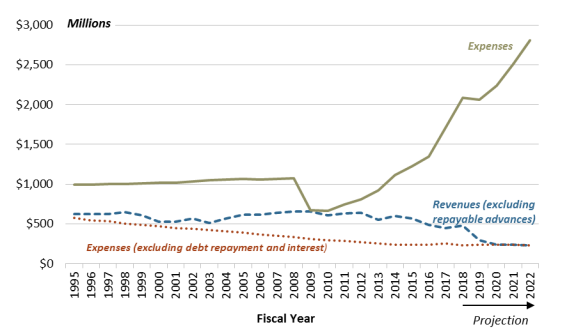

|

Figure 3. Coal Excise Tax Collections FY1999 - FY2022 |

|

|

Sources: IRS SOI Bulletin Historical Table 20, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-historical-table-20; and Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, Treasury Bulletin, March 2018, pp. 90-91, http://www.fiscal.treasury.gov. |

Black lung excise tax collections have generally declined in recent years (see Figure 3). In FY2009, more than $650 million was collected from the BLET. In FY2017, collections were about $429 million. The decline in BLET collections follows the general decline in U.S. coal production.36 As the price of coal rose in the 2000s, coal mined underground tended to pay the tax at a fixed rate of $1.10 per ton, as opposed to paying 4.4% of the sales price.

In the years beyond 2018, coal excise tax receipts are expected to fall sharply, reflecting the decrease in the coal excise tax rate (see Figure 3).

Legislative History

The excise tax on coal was established to help ensure the coal industry shared in the social costs imposed by black lung disease. Over time, the rate of the tax has been increased, in an effort to provide sufficient revenue to meet this objective.

Establishing an Excise Tax on Coal

The Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-227) first imposed the Section 4121 excise tax on coal. When enacted, the tax was $0.50 per ton for coal from underground mines, and $0.25 per ton for coal from surface mines. The tax was limited to 2% of the sales price. The tax was effective for sales after March 31, 1978.

Before P.L. 95-227 was enacted there was considerable debate surrounding how black lung benefits programs should be financed.37 Various mechanisms to shift the costs of the black lung benefits program to the coal industry and its customers were considered. These debates ultimately led to the establishment of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund and the related excise tax on coal.

There was also debate about how to structure the proposed tax. Some suggested a graduated tax, with higher rates imposed on coal with a higher British thermal unit (Btu) content, as such coal was believed to be more likely to cause black lung disease.38 There were concerns, however, that such a tax could be difficult to administer. Other proposals suggested that coal be subject to a uniform rate, with coal mined from underground deposits subject to a higher rate than other coal (including lignite). A concern with this approach was that coal prices vary substantially per ton for different types of coal (lignite is less expensive than anthracite), meaning that the tax as a percent of the sales price could differ substantially across different types of coal. One answer to this concern is to impose an ad valorem tax, or a tax based on the sales price. Another approach that was considered was to impose a "premium rate" at a level that would fully finance the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, giving authority to the Department of Labor to adjust the fee as necessary. The tax as enacted was the lesser of the per-unit price or the ad valorem rate of 2%.

Increasing the Rate of Tax

In the early 1980s, it was observed that coal excise tax revenues were not sufficient to meet the trust fund's obligations. The Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1981 (P.L. 97-119) doubled the excise tax rates to $1.00 per ton for coal from underground mines, and $0.50 per ton for coal from surface mines, not to exceed 4% of the sales price. The higher rates were effective January 1, 1982. The doubled rates were temporary, and scheduled to revert to the previous rates on January 1, 1996. Further, the rates could be reduced earlier if the trust fund repaid all advances and interest from the general fund of the Treasury. A stated goal of this legislation was to eliminate the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund's debt.39

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-272) again increased the BLET rates to $1.10 for underground-mined coal, and $0.55 for surface-mined coal, not to exceed 4.4% of the sales price. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (P.L. 100-203) extended these rates through 2013.

Increased excise tax rates on coal were again extended in 2008. Current-law rates were extended through 2018 as part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA; P.L. 110-343). When extending the increased rates, Congress reiterated the original intent of establishing trust fund financing for black lung benefits, observing that it is "to reduce reliance on the Treasury and to recover costs from the mining industry."40 It was also observed that the program's expenses had continued to exceed revenues over time, and that the debt to the Treasury was not likely to be paid off by 2013. For these reasons, "the Congress believe[d] that it [was] appropriate to continue the tax on coal at the increased rates beyond the expiration date."41

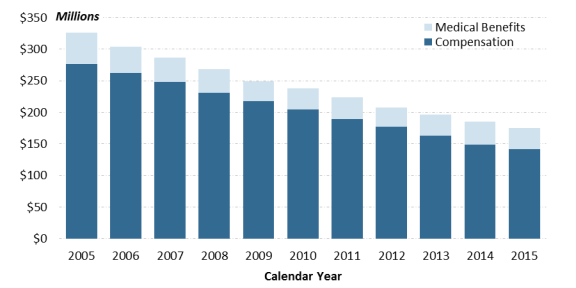

Borrowing and Debt

When receipts of the trust fund are less than expenditures, advances are appropriated from the general fund of the Treasury to the trust fund. These advances are repayable, and interest charged on these advances is also payable to the general fund.42 The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-272) provided a five-year forgiveness of interest on debt owed to the Treasury's general fund. As a result, the principal amount of trust fund debt outstanding was relatively unchanged throughout the late 1980s.43 The moratorium on interest payments ended September 30, 1990.

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, the cumulative end-of-year debt of the trust fund grew, and the trust fund continued to receive repayable advances from the general fund to cover expenses. The trust fund was subject to financial restructuring when the current excise tax rate was extended until January 1, 2019, in EESA.

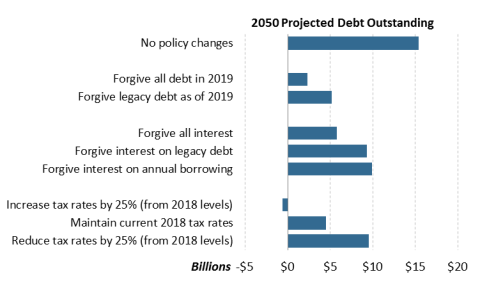

The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund debt was restructured in FY2009. Essentially, the partial forgiveness and restructuring allowed the trust fund to refinance outstanding repayable advances and unpaid interest on those advances. As a result of the partial forgiveness and refinancing, the cumulative debt was reduced from $10.4 billion at the end of FY2008 to $6.2 billion by the end of FY2009. At the time of the restructuring it was expected that the trust fund's debt would be fully eliminated by FY2040.44 The trust fund's cumulative debt has trended downward since the restructuring (see Figure 4). However, coal excise tax revenue has been less than anticipated in recent years. As a result, current projections suggest that the trust fund debt will rise over time when considering annual borrowing as well as legacy debt. The trust fund's debt is therefore not on a path to be eliminated. By FY2050, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) projects the trust fund's debt will be $15.4 billion without any changes in current policy.45

Other Revenue Sources

In addition to revenue from the BLET and repayable general fund advances, the trust fund receives revenue from the collection of certain fines, penalties, and interest paid by coal operators and miners and reimbursements from responsible operators.

Fines, Penalties, and Interest

Part C of the BLBA authorizes the following fines and penalties for violations of the act:

- a civil penalty of up to $1,000 per day for a mine operator's failure to secure benefits through insurance or approved self-insurance;46

- a fine of up to $1,000 upon conviction of the misdemeanor offense of knowingly destroying or transferring property of a mine operator with the intent to avoid the payment of benefits for which the mine operator is responsible;47

- a fine of up to $1,000 upon conviction of the misdemeanor offense of making a false or misleading statement or representation for the purposes of obtaining benefits;48 and

- a civil penalty of up to $500 for a mine operator's failure to file a report on miners who are or may be entitled to benefits as required by DOL.49

The amount of these penalties and fines, as well as interest assessed, is paid into the trust fund. In FY2017, trust fund receipts from fines, penalties, and interest totaled $1.2 million. This is a small source of trust fund revenue relative to the coal excise tax, which generated $428.7 million in trust fund revenues in FY2017.50

Collection from Responsible Mine Operators

The trust fund is authorized to begin paying benefits within 30 days if no responsible operator has begun payment. If, after paying benefits, DOL is able to identify a responsible operator, the trust fund may seek to collect from that operator the costs of benefits already paid by the trust fund and interest assessed on this amount.51 The amount of these collections is paid into the trust fund. In FY2017, $19.9 million was collected from responsible mine operators. The amount collected from responsible mine operators has fluctuated over time, but has averaged about 1% of total receipts since 1995.52

Financial Condition and Outlook

Various factors have contributed to the ongoing situation of trust fund expenditures exceeding trust fund revenues. Throughout the 1980s, black lung benefit payments and administrative expenditures exceeded trust fund revenue. As a result, the trust fund accumulated debt. As discussed above, over time, various efforts have been made to improve the fiscal condition of the trust fund. However, as of the end of FY2017, the trust fund remains in debt. The trust fund's cumulative debt at the end of FY2017 was $3.1 billion.53 The trust fund also borrowed $1.3 billion from the general fund that same year.

Projections suggest that borrowing from the general fund will increase over the next few years, even as cumulative (or legacy) debt is paid down. Under the current excise tax rates, benefit payments and administrative expenses will be approximately equal to trust fund revenues in FY2020 through FY2022 (see Figure 5). However, revenues are not projected to be sufficient to repay debt, and expenses are projected to rise over time when debt and interest expenses are included. Specifically, by FY2022, it is projected that the trust fund will borrow $2.6 billion in repayable advances from the general fund.54

Policy Issues and Options

There are various policy options that Congress might consider to improve the fiscal condition of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. Broadly, increasing taxes on the coal industry (or maintaining 2018 rates) would pass the costs associated with paying black lung benefits onto the coal industry. Alternatively, forgiving trust fund interest or debt or financing black lung benefits out of general fund revenues would pass the costs of federal black lung benefits onto taxpayers in general. Another option would be to reduce federal black lung benefits.

Revenue Options

Additional revenue would likely need to be provided to the trust fund if the trust fund is to pay for past black lung benefits and maintain current benefit levels. Additional revenue may be needed even if past debt is forgiven (or assumed by the general fund), as anticipated trust fund revenues are not likely to be sufficient to cover anticipated trust fund expenditures.

Change the Coal Excise Tax

As discussed above, in the past, Congress and the President have opted to increase the excise tax on coal to address shortfalls in the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. These increased rates have been temporary, and scheduled to revert back to the reduced rate if the trust fund's debt is eliminated. Congress has chosen to extend the increased rates beyond their scheduled expiration when the trust fund is in debt. One option would be to extend 2018 rates.. The GAO projects that if 2018 coal excise tax rates are extended, the trust fund will have a debt of $4.5 billion in 2050 (see "GAO Options for Improving Trust Fund Finances" below).55 GAO projections suggest that increasing 2018 tax rates by 25% would eliminate the trust fund's debt, leaving the trust fund with a surplus of $0.6 billion in 2050.

Modify Coal Industry Tax Benefits

An alternative way to raise revenue from the coal industry is to scale back or eliminate various tax expenditures, or tax preferences, from which the coal industry benefits. For example, coal producers benefit from being able to expense exploration and development costs and are able to recover costs using percentage depletion (depletion based on revenue from the sale of the mineral asset) instead of cost depletion (depletion based on the amount of the mineral asset exhausted and the amount invested in the asset). The Obama Administration regularly proposed repealing these tax incentives as part of the Administration's annual budget.56

It could be difficult to assign the revenues raised via the repeal of tax benefits to the trust fund. With an excise tax, it is straightforward to identify the revenue generated by the tax and earmark the revenue for a trust fund. It is not as straightforward to determine the amount of revenue that is raised through the repeal of an income tax expenditure, or direct the additional revenue raised because a certain preference is no longer in the code to a trust fund. Repeal of coal-industry tax benefits could, however, be used to offset the cost of a one-time transfer from the general fund to the trust fund.

Provide Additional General Fund Revenue

Revenue from various sources, including the general fund, could be used to supplement trust fund revenue generated from current sources. General fund revenues are not earmarked for a specific purpose, and there is generally no direct link between the source of general fund revenue and the government good or service provided. Black lung benefits were paid out of general revenue before the trust fund was established in 1977.

Trust funds are generally established when there is a link between the government benefits or services being provided and the revenue source funding those benefits or services.57 The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund was established because Congress believed that the costs of the part C black lung program should be borne by the coal industry.58 Financing black lung benefits with general fund revenue would weaken the link between the industry and black lung benefits, while reducing the burden on the industry associated with paying for black lung benefits.

Forgive Trust Fund Interest or Debt

In the past the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund's fiscal outlook has been improved through interest and debt forgiveness. As discussed above, in the late 1990s, there was a five-year forgiveness of interest on debt owed to the Treasury's general fund. More recently, debt was forgiven as part of the 2008 restructuring of the trust fund's debt.

The GAO projects that if all current debt were forgiven, the trust fund would accumulate $2.3 billion in new debt by 2050. If all interest were forgiven, the trust fund debt is projected to be $5.8 billion by 2050. Forgiving the trust fund's interest or debt obligations would shift the burden of paying for black lung disability benefits from the coal industry to general taxpayers. However, a one-time appropriation to forgive interest or debt is a transparent option for satisfying the trust fund's obligations to the general fund.59

|

GAO Options for Improving Trust Fund Finances In a May 2018 report the Government Accountability Office (GAO) projected the debt of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund under a variety of policy scenarios. These scenarios are summarized in Figure 6. Broadly, benefit payments and administrative costs are expected to increase in the near term (into the mid-2020s), but eventually decline over time. Trust fund revenue, however, is expected to fall sharply after excise tax rates are reduced in 2019. Even if all current debt is forgiven, projections suggest trust fund revenues will not be sufficient to cover trust fund obligations, under current policy. Similarly, forgiving interest on the debt is not expected to eliminate trust fund debt over the longer term (by 2050). Extending the 2018 excise tax rates on coal is also not sufficient to achieve zero trust fund debt by 2050. However, projections suggest that increasing excise tax rates by 25% above 2018 levels would lead to a trust fund surplus of $0.6 billion by 2050. Policies combining debt forgiveness and additional revenues may also be considered. For example, GAO projects that the trust fund would have zero debt in 2050 if 2018 coal excise tax rates were extended and $2.4 billion in debt were forgiven.

|

Expenditure Options

The primary expenditures of the trust fund are for the payment of Part C benefits to miners in cases in which there is no responsible operator. In order to reduce expenditures and improve the long-term financial health of the trust fund, Congress could consider several options to reduce the generosity and scope of benefits or increase the ability of the federal government to ensure that coal operators, even those who are in the bankruptcy process, pay benefits for their miners.

Reduce Benefit Amounts

A reduction in the amount of Part C benefits would result in lower Part C expenditures from both responsible coal operators and the trust fund. However, as compared to other workers' compensation benefits, Part C benefits are relatively low. The basic Part C benefit rate for a single miner is equal to 37.5% of the base rate of pay for federal employees at the GS-2, Step 1 level. For 2019 this benefit is just over $660 per month, or under $8,000 per year. In the majority of state workers' compensation programs, the basic benefit rate is set at two-thirds of the worker's pre-disability wage, subject to statutory minimums and maximums.60 The other workers' compensation programs administered by DOL, the LHWCA, and the Federal Employees' Compensation Act (FECA) use two-thirds of a worker's pre-disability wage as the basis for their benefits.61 A federal worker with a spouse or dependent in the FECA program is entitled to 75% of his or her pre-disability wage. The minimum benefit for total disability or death in the FECA program, 75% of GS-2, Step 1, is twice the amount of the Part C benefit rate. In addition, unlike the other federal workers' compensation programs and many state programs, there is no automatic adjustment to Part C benefits to reflect increases in the cost of living. Part C benefits instead increase only when federal pay rates are increased.

Restrict Benefit Eligibility

The eligibility of miners and survivors to Part C benefits could be restricted to reduce expenditures from responsible operators and the trust fund. In 1981, Congress enacted several eligibility restrictions to miners and survivors as part of the Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1981, to address concerns about the financial insolvency of the trust fund. Specifically, this law removed the following three eligibility presumptions for new claims going forward:

- A rebuttable presumption that the death of a miner who worked in mining for at least 10 years and who died of any respirable disease, was due to pneumoconiosis (listed as presumption 2 in Table 1).

- A rebuttable presumption that a miner employed in mining for at least 15 years, and who has a chest x-ray that is interpreted as negative with respect to certain statutory standards but who has other evidence of a totally disabling respiratory or pulmonary impairment, is totally disabled due to pneumoconiosis, or died due to pneumoconiosis. This presumption may only be rebutted by the Secretary of Labor establishing that the miner does not or did not have pneumoconiosis or that the miner's respiratory or pulmonary impairment did not arise out of connection to mine employment (presumption 4 in Table 1).

- A presumption that a miner who died on or before March 1, 1978, and who was employed in mining for at least 25 years before June 30, 1971, died due to pneumoconiosis, unless it is established that at the time of the miner's death, he or she was not at least partially disabled due to pneumoconiosis (presumption 5 in Table 1).

In addition to removing three of the five existing eligibility presumptions, the 1981 law also removed the right of the survivors of a miner who is determined to be eligible for Part C benefits at the time of his or her death to receive survivors' benefits without filing a new claim, thus permitting the payment of survivors' benefits in the case of a current beneficiary, even if the beneficiary's death is not proven to be linked to pneumoconiosis.

Two of the restrictions put in place by the 1981 legislation were later removed by the ACA. The ACA reinstated the fourth eligibility presumption and expanded rights for survivors' benefits, thus expanding eligibility for both miners and certain survivors.

Increase the Ability of the Federal Government to Recover Benefit Costs from Responsible Operators

Under Part C of the BLBA, the federal government may recover the costs of benefits, and interest accrued on those benefits, paid by the trust fund from identified responsible operators. In addition, Part C allows the federal government to place a lien on the property and rights to property of an operator that refuses to pay the benefits and interest it owes to the trust fund. In the case of a bankruptcy or insolvency proceeding, this lien is to be treated in the same manner as a lien for taxes owed to the federal government.

However, in a 2016 letter to the Comptroller General requesting a GAO review of the trust fund, Representatives Bobby Scott, Ranking Member of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, and Sander Levin, Ranking Member of the House Committee on Ways and Means, claimed that the number of current and potential bankruptcies among coal operators is placing stress on the trust fund.62 Representatives Scott and Levin cited the example of Patriot Coal which, according to their letter, transferred $62 million in Part C liabilities to the trust fund when it became insolvent. In addition, this letter claims that insolvent coal operators may be able to avoid trust fund liens by continuing to make benefit payments until after the court in their bankruptcy cases has approved the sale of their assets to another company. Because the original company was never in default of its payments, no lien was filed, and these assets were able to be purchased by another company without any lien or future liability to the trust fund.

Congress may examine the issue of the impact of coal operator bankruptcies and the interaction of bankruptcy law and the BLBA's lien provisions, to strengthen both the federal government's ability to ensure that responsible operators are paying for benefits and reduce the benefit expenditures of the trust fund.