Introduction

This report provides background information and potential oversight issues for Congress on war-related and other international emergency or contingency-designated funding since FY2001.

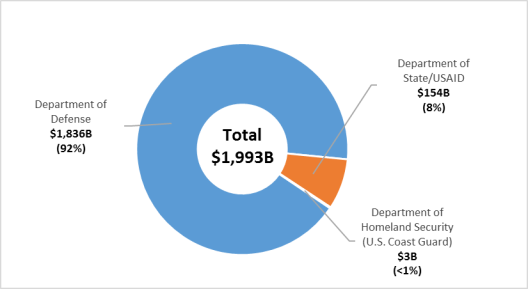

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress has appropriated approximately $2 trillion in discretionary budget authority designated for emergencies or OCO/GWOT in support of the broad U.S. government response to the 9/11 attacks and for other related international affairs activities.1 This figure includes $1.8 trillion for the Department of Defense (DOD), $154 billion for the Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and $3 billion for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Coast Guard (see Figure 1).2

This CRS report is meant to serve as a reference on certain funding designated as emergency requirements or for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT), as well as related budgetary and policy issues. It does not provide an estimate of war costs within the OCO/GWOT account (all of which may not be for activities associated with war or defense) or such costs in the DOD base budget or other agency funding (which may be related to war activities, such as the cost of health care for combat veterans).

For additional information on the FY2019 budget and related issues, see CRS Report R45202, The Federal Budget: Overview and Issues for FY2019 and Beyond, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS In Focus IF10942, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: An Overview of H.R. 5515, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R45168, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs: FY2019 Budget and Appropriations, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed].

For additional information on the Budget Control Act as amended, see CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report R44039, The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed].

For additional information on U.S. policy in Afghanistan and the Middle East, see CRS Report R45122, Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed], CRS Report R45096, Iraq: Issues in the 115th Congress, by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report RL33487, Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response, coordinated by [author name scrubbed].

|

Figure 1. Emergency and OCO/GWOT Discretionary Budget Authority, (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of Department of Defense, National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2019, Table 2-1: Base Budget, War Funding and Supplementals by Military Department, by P.L. Title (FY2001-FY2019), April 2019; Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications, FY2001-FY2019; Department of Homeland Security, Budget in Brief documents, FY2001-FY2019; Congressional Budget Office, Final Fiscal Year 2018 House Current Status of Discretionary Appropriations, as of September 30, 2018; Congressional Budget Office, Fiscal Year 2019 House Current Status of Discretionary Appropriations, as of October 5, 2018. Notes: Figures in nominal, or current, dollars (not adjusted for inflation). Totals may not sum due to rounding. FY2019 figure for State/USAID and DHS were not available because continuing resolutions P.L. 115-245 and P.L. 115-298 included partial-year funding. DHS (Coast Guard) figures do not include funding redirected from P.L. 107-38. Figures do not include funding for domestic programs, or other agency funding identified for OCO/GWOT or related purposes amounting to less than 1% of the total. |

Background

Increase in War-Related Appropriations after 9/11

Congress may consider one or more supplemental appropriations bills (colloquially called supplementals) for a fiscal year to provide funding for unforeseen needs (such as a response to a national security threat or a natural disaster), or to increase appropriations for other activities that have already been funded.3 Supplemental appropriations measures generally provide additional funding for selected activities over and above the amount provided through annual or continuing appropriations.4

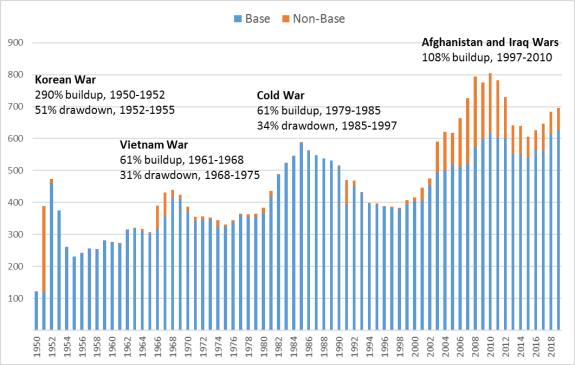

Throughout the 20th century, Congress relied on supplemental appropriations to fund war-related activities, particularly in the period immediately following the start of hostilities. For example, in 1951, a year after the start of the Korean War, Congress approved DOD supplemental appropriations totaling $32.8 billion ($268 billion in constant FY2019 dollars). In 1952, DOD supplemental appropriations totaled just $1.4 billion ($11 billion in constant FY2019), as the base budget incorporated costs related to the war effort. A similar pattern occurred, to varying degrees, during the Vietnam War and 1990-1991 Gulf War.5

During the post-9/11 conflicts, primarily conducted in Afghanistan and Iraq but also in other countries, Congress has, for an extended period and to a much greater degree than in previous conflicts in the 20th century, appropriated supplemental and specially designated funding over and above the base DOD budget—that is, funding for planned or regularly occurring costs to man, train, and equip the military force. Since FY2001, DOD funding designated for OCO/GWOT has averaged 17% of the department's total budget authority (see Figure 2). By comparison, during the conflict in Vietnam—the only other to last more than a decade—DOD funding designated for non-base activities averaged 6% of the department's total budget authority.6

Supplemental appropriations can provide flexibility for policymakers to address demands that arise after funding has been appropriated. However, that flexibility has caused some to question whether supplementals should only be used to respond to unforeseen events, or whether they should also provide funding for activities that could reasonably be covered in regular appropriations acts.7

Shift from Emergency Supplementals to Contingency Funding

Congress used supplemental appropriations to provide funds for defense and foreign affairs activities related to operations in Afghanistan and Iraq following 9/11, and each subsequent fiscal year through FY2010. Initially understood as reflecting needs that were not anticipated during the regular appropriations cycle, supplemental appropriations were generally enacted as requested, and almost always designated as emergency requirements.

Beginning in FY2004, DOD received some of its war-related funding in its regular annual appropriations; these funds were designated as emergency. When funding needs for war and non-war-related activities were higher than anticipated, the Bush Administration submitted supplemental requests.8

In the FY2011 appropriations cycle, the Obama Administration moved away from submitting supplemental appropriations requests to Congress for war-related activities and used the regular budget and appropriation process to fund operations. This approach implied that while the funds might be war-related, they largely supported predictable ongoing activities rather than unanticipated needs. In concert with this change in budgetary approach, the Obama Administration began formally using the term Overseas Contingency Operations in place of the Bush Administration's term Global War on Terror.9 Both the Obama and Trump Administrations requested that OCO funding be designated in a manner that would effectively exempt such funding from the BCA limits on discretionary defense spending.

Currently, there is no overall procedural or statutory limit on the amount of emergency or OCO/GWOT-designated spending that may be appropriated on an annual basis. Both Congress and the President have roles in determining how much emergency or OCO/GWOT spending is provided to federal agencies each fiscal year. Such spending must be designated as such within the President's budget request for congressional consideration. The President must separately designate the spending after Congress enacts appropriations for it to be available for expenditure.

Designation of Funding as Emergency or OCO/GWOT

The emergency funding designation predated the OCO/GWOT designation. Through definitions statutorily established by the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA; P.L. 99-177), spending designated as emergency requirements is for "unanticipated" purposes, such as those that are "sudden ... urgent ... unforeseen ... and temporary."10 The BBEDCA does not further specify the types of activities that are eligible for that designation. Thus, any discretionary funding designated by Congress and the President as being for an emergency is effectively exempted from certain statutory and procedural budget enforcement mechanisms, such as the BCA limits on discretionary spending.11

Debate of what should constitute OCO/GWOT or emergency activities and expenses has shifted over time, reflecting differing viewpoints about the extent, nature, and duration of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. Over the years, both Congress and the President have at times adopted more, and at times less, expansive definitions of such designations to accommodate the strategic, budgetary, and political needs of the moment.

Prior to February 2009, U.S. operations in response to the 9/11 attacks were collectively referred to as the Global War on Terror, or GWOT. Between September 2001 and February 2009, there was no separate budgetary designation for GWOT funds—instead, funding associated with those operations was designated as an emergency requirement.

The term OCO was not applied to the post-9/11 military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan until 2009. In February 2009, the Obama Administration released A New Era of Responsibility: Renewing America's Promise, a presidential fiscal policy document.12 That document did not mention or reference GWOT; instead, it used the term OCO in reference to ongoing military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The first request for emergency funding for OCO—not GWOT—was delivered to Congress in April 2009.13 Since the FY2010 budget cycle, DOD has requested both base budget and OCO funding as part of its annual budget submission to Congress.14

Beginning with the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (NDAA; P.L. 111-84), the annual defense authorization bills have referenced the authorization of additional appropriations for OCO rather than the names of U.S. military operations conducted primarily in Afghanistan and Iraq.15 In 2011, the BCA (P.L. 112-125) amended the BBEDCA to create the Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism designation, which provided Congress and the President with an alternate way to exempt funding from the BCA caps without using the emergency designation.16 Beginning with the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2012 (P.L. 112-74), annual appropriations bills have referenced the OCO/GWOT designation.17

The foreign affairs agencies began formally requesting OCO/GWOT funding in FY2012, distinguishing between what is referred to as enduring, ongoing or base costs versus any extraordinary, temporary costs of the State Department and USAID in supporting ongoing U.S. operations and policies in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.18 Congress, having used OCO/GWOT exemption for DOD, adopted this approach for foreign affairs, though its uses for State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) activities have never been permanently defined in statute. For the first foreign affairs OCO/GWOT appropriation, in FY2012, funds were provided for a wide range of recipient countries beyond the countries in the President's request, including Yemen, Somalia, Kenya, and the Philippines. In addition to country-specific uses, OCO/GWOT-designated funds were also appropriated for the Global Security Contingency Fund.19

OCO and the Budget Control Act (BCA)

All budgetary legislation is subject to a set of enforcement procedures associated with the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-344), as well as other rules, such as those imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-125) as amended. Those rules provide mechanisms to enforce both procedural and statutory limits on discretionary spending.20

The Budget Control Act of 201121

Enacted on August 2, 2011, the BCA as amended sets limits on defense and nondefense spending. As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the BCA aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.22

The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority.23 The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration automatically cancels previously enacted appropriations (a form of budget authority) by an amount necessary to reach prespecified levels.24 The BCA effectively exempted certain types of discretionary spending from the statutory limits, including funding designated for OCO/GWOT.25

As a result, Congress and the President have designated funding for OCO to support activities that, in previous times, had been funded within the base budget. This was done, in part, as a response to the discretionary spending limits enacted by the BCA. By designating funding for OCO for certain activities not directly related to contingency operations, Congress and the President can effectively continue to increase topline defense, foreign affairs, and other related discretionary spending without triggering sequestration.

Congress has repeatedly amended the legislation to raise the spending limits (thus lowering its deficit-reduction effect by corresponding amounts). Congress has passed four bills that revised the automatic spending caps initially established by the BCA, including the following:

- American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240);

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67);

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74); and

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123).

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018

On February 9, 2018, three days before President Donald Trump submitted his FY2019 budget request, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018, P.L. 115-123). The act raised the discretionary spending limits set by the BCA from $1.069 trillion for FY2017 to $1.208 trillion for FY2018 and to $1.244 trillion for FY2019. The BBA 2018 increased FY2019 discretionary defense funding levels (excluding OCO) by the largest amounts to date—$85 billion, from $562 billion to $647 billion, and nondefense funding (including SFOPS) by $68 billion, from $529 billion to $597 billion. It did not change discretionary spending limits for FY2020 and FY2021.26

OCO Funds for Non-War DOD Activities

DOD documents indicate the department in recent years has used OCO funding for activities viewed as unrelated to war.

For example, the department's FY2019 budget request estimates $358 billion in OCO funding from FY2015 through FY2019. Of that amount, DOD categorizes $68 billion (19%) for activities unrelated to operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. These activities are described as "EDI/Non-War," referring in part to the European Deterrence Initiative, and "Base-to-OCO," referring to OCO funding used for base-budget requirements.27

Similarly, a DOD Cost of War report from June 2018 shows $1.8 trillion in war-related appropriations from FY2001 through FY2018 for operations primarily conducted in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Of that total, DOD categorizes $219 billion (12%) as other than "war funds." These funds are described as "Classified," "Modularity," "Fuel (non-war)," "Noble Eagle (Base)," and "Non-War."28

International affairs agencies also began increasing the share of their budgets designated for OCO, and applying the designation to an increasing range of activities apparently unrelated to conflicts. OCO as a share of the international affairs budget grew from about 21% in FY2012 to nearly 35% in FY2017. Unlike DOD, however, the State Department and USAID have not specified whether any OCO-designated funds are considered part of the agencies' base budgets.

Previous Proposal to Move OCO Funding to Base Budget

According to a DOD budget document from FY2016, the Obama Administration planned to "transition all enduring costs currently funded in the OCO budget to the base budget beginning in 2017 and ending by 2020."29 The plan was to describe "which OCO costs should endure as the United States shifts from major combat operations, how the Administration will budget for the uncertainty surrounding unforeseen future crises, and the implications for the base budgets of DOD, the Intelligence Community, and State/OIP. This transition will not be possible if the sequester-level discretionary spending caps remain in place."30 The BCA remained in effect and OCO funding was used for base-budget requirements.

OCO: Safety Valve, Slush Fund, or Practical Solution?

Some defense officials and policymakers say OCO funding enables a flexible and timely response to an emergency or contingency and provides a political and fiscal safety valve to the BCA caps and threat of sequestration.31 They say if OCO funding were not used in such a manner and discretionary spending limits remained in place, DOD and other federal agencies would be forced to cut base budgets and revise strategic priorities. For example, former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has said if Congress allows the FY2020 and FY2021 defense spending caps to take effect, the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which calls for the United States to bolster its military advantage against potential competitors such as Russia and China, "is not sustainable."32

Critics, including Acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney, have described the OCO account as a "slush fund" for military and foreign affairs spending unrelated to contingency operations.33 Mulvaney, former director of the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), has described the use of OCO funding for base budget requirements as "budget gimmicks."34 Critics argue what was once generally restricted to a fund for replacing combat losses of equipment, resupplying expended munitions, transporting troops to and through war zones, and distributing foreign aid to frontline states has "ballooned into an ambiguous part of the budget to which government financiers increasingly turn to pay for other, at times unrelated, costs."35

OMB criteria for OCO funding include the combat losses of ground vehicles, aircraft, and other equipment; replenishment of munitions expended in combat operations; facilities and infrastructure in the theater of operations; transport of personnel, equipment, and supplies to and from the theater; among other items and activities.36

Determining which activities are directly related, tangentially related, or unrelated to war operations is often a point of debate. Some have questioned the use of OCO funding to purchase F-35 fighter jets: "It is jumping the shark.... There's no pretense that it has anything to do with the region."37 Others have argued it makes sense for the military to use OCO funding to purchase new aircraft to replace planes used in current conflicts and no longer in production: "What are the conditions that are making the combatant commanders and those with train/equip authority to say, 'We need more of this?'"38

GWOT/OCO Appropriations by Agency, FY2001-FY2019

Congress has appropriated approximately $2 trillion in discretionary budget authority for war-related and other international emergency or contingency-designated activities since 9/11. This figure is a CRS estimate of funding designated for emergencies or OCO/GWOT in support of the broad U.S. government response to the 9/11 attacks, as well as other foreign affairs activities, from FY2001 through FY2019. This includes $1.8 trillion for DOD, $154 billion for the Department of State and USAID, and $3 billion for DHS and the Coast Guard (see Table 1). These figures do not include emergency-designated funding appropriated in this period for domestic programs, such as disaster response.

|

Fiscal Year |

DOD |

State/USAID |

Homeland |

Total |

||||||||

|

2001 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2002 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2003 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2004 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2005 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2006 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2007 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2008 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2009 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2010 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2011 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2012 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2013 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2014 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2015 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2016 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2017 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2018 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

2019 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Agency % of Total |

92.1% |

|

|

|

DOD

OCO/GWOT Funding as a Share of the DOD Budget

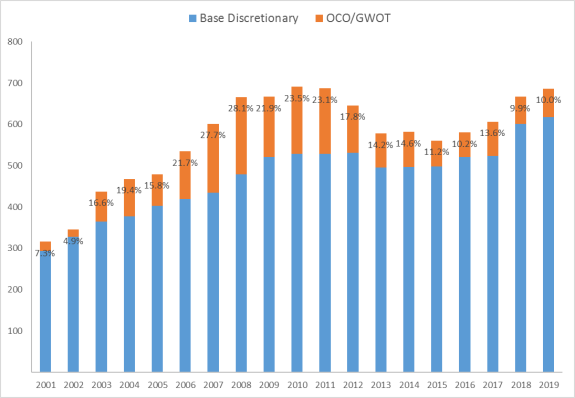

From FY2001 through FY2009, DOD received $1.8 trillion in appropriations for OCO/GWOT, or approximately 17% of the department's total discretionary budget authority of $10.8 trillion during the period.39

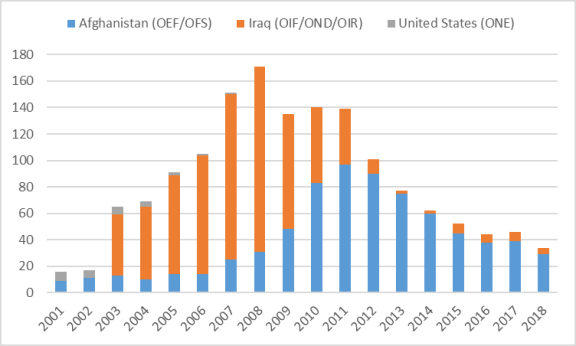

The department's OCO/GWOT funding peaked in FY2008 both in terms of nominal dollars, at $186.9 billion, and as a share of its discretionary budget, at 28.1% (see Figure 3), after the Bush Administration surged additional U.S. military personnel to Iraq. The department's OCO funding also increased as a share of its discretionary spending from FY2009 to FY2010 following the Obama Administration's deployment of more U.S. military personnel to Afghanistan, and again in FY2017 following enactment of legislation in response to the Trump Administration's request for additional appropriations.40

In FY2019, the department's OCO/GWOT funding totaled $68.8 billion, or 10% of its discretionary spending.41

OCO, Base Budget Comparisons by Appropriations Title, Military Service

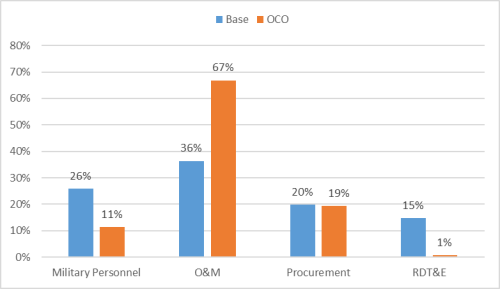

In terms of appropriations titles, more than two-thirds of OCO/GWOT funding since FY2001 has been for Operation and Maintenance (O&M)—nearly double the percentage of base budget funding for O&M over the same period (see Figure 4). O&M funds pay for the operating costs of the military such as fuel, maintenance to repair facilities and equipment, and the mobilization of forces. DOD describes "war-related operational costs" as operations, training, overseas facilities and base support, equipment maintenance, communications, and replacement of combat losses and enhancements.42

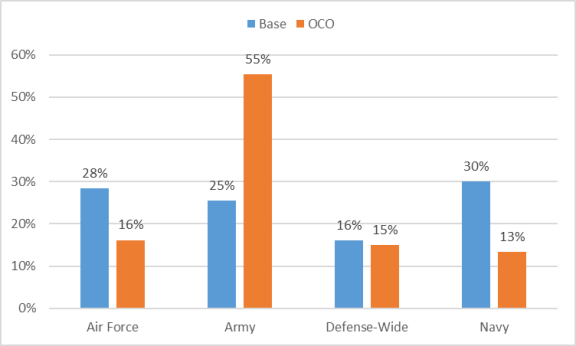

In terms of the military services, more than half (55%) of OCO/GWOT funding since FY2001 has gone to the Army—more than double the percentage of base budget funding for the service during this period (see Figure 5). Emergency appropriations were initially provided as general "defense-wide" appropriations. Beginning in FY2003, as operations evolved and planning developed, allocations increased and were specifically provided for the services.

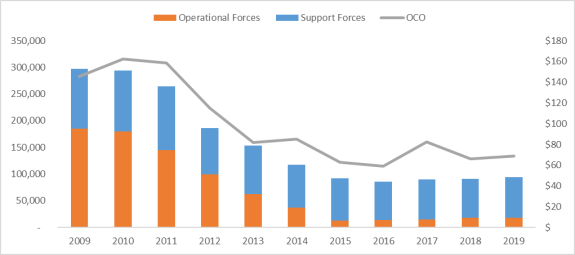

Trends in OCO Funding and Troop Levels

OCO funding for DOD has not decreased at the same rate as the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria has decreased.43 For example, the number of U.S. military personnel in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria decreased from a peak of 187,000 personnel in FY2008 (including 148,000 in Iraq and 39,000 in Afghanistan) to an assumed level of nearly 18,000 personnel in FY2019 (including 11,958 personnel in Afghanistan and 5,765 personnel in Iraq and Syria)—a decline of approximately 169,000 personnel (90%).44 Meanwhile, OCO funding decreased from a peak of $187 billion in FY2008 to $69 billion in FY2019—a decline of approximately $118 billion (63%).

While the number of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria has decreased since FY2009, the number of U.S. troops deployed or stationed elsewhere to support those personnel has fallen by a lesser degree and, in recent years, remained relatively steady. For example, the number of support forces—that is, personnel from units and forces operating outside of Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other countries (including those stationed in the continental United States or otherwise mobilized) decreased from 112,000 personnel in FY2009 to an assumed level of 76,073 personnel in FY2019—a decline of 35,927 personnel (32%). In addition, when these support forces are combined with in-country force levels, the total force level decreases by a percentage more similar to the OCO budget, from 297,000 personnel in FY2009 to an assumed level of 93,796 personnel in FY2019—a decline of 203,204 personnel (68%) (see Figure 6).

Some of these support forces serve in U.S. Central Command's area of responsibility, which includes 20 countries in West Asia, North Africa, and Central Asia, and whose forward headquarters is based in Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar.45

According to DOD, the reason OCO funding has not fallen in proportion to the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria is "due to the fixed, and often inelastic, costs of infrastructure, support requirements, and in-theater presence to support contingency operations."46 For example, in FY2019, the department requested $20 billion in OCO funding for "in-theater support"—nearly 30% of the OCO request and more than any other functional category.47

However, some analysts have noted the U.S. military's fixed costs in Afghanistan remained relatively stable at roughly $7 billion a year from FY2005 through FY2013 until after the BCA went into effect—and have since increased to roughly $32 billion a year, suggesting "that roughly $25 billion in 'enduring' or base budget costs migrated into the Afghanistan budget, effectively circumventing the budget caps. The actual funding needed for operations in Afghanistan is roughly $20 billion in FY2019."48

DOD Criteria for Contingency Operations

Title 10, Section 101, of the United States Code, defines a contingency operation as any Secretary of Defense-designated military operation "in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing military force." Since the 1990s NATO intervention in the Balkans, DOD Financial Management Regulations (FMR) have defined contingency operations costs as those expenses necessary to cover incremental costs "that would not have been incurred had the contingency operation not been supported."49 Such incremental costs would not include, for example, base pay for troops or planned equipment modernization, as those expenditures are normal peacetime needs of the DOD.50

In September 2010, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), in collaboration with DOD, issued criteria for the department to use in making war/overseas contingency operations funding requests (see Appendix A).

In January 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded the criteria for deciding whether items belong in the base budget or OCO funding "are outdated and do not address the full scope of activities" in the budget request.51 "For example, they do not address geographic areas such as Syria and Libya, where DOD has begun military operations; DOD's deterrence and counterterrorism initiatives; or requests for OCO funding to support requirements not related to ongoing contingency operations" it states.52

Section 1524 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-91), directed the Secretary of Defense to "update the guidelines regarding the budget items that may be covered by overseas contingency operations accounts."

Costs of Major DOD Contingency Operations

Congress has enacted legislation directing DOD to compile reports on the costs of certain contingency operations.

Section 1266 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-91) directs the Secretary of Defense to submit the Department of Defense Supplemental and Cost of War Execution report, known as the Cost of War report, on a quarterly basis to the congressional defense committees and the GAO: "Not later than 45 days after the end of each fiscal year quarter, the Secretary of Defense shall submit to the congressional defense committees and the Comptroller General of the United States the Department of Defense Supplemental and Cost of War Execution report for such fiscal year quarter."53

The conference report accompanying the Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-245) requires DOD to report incremental costs for operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility and directs:

the Secretary of Defense to continue to report incremental costs for all named operations in the Central Command Area of Responsibility on a quarterly basis and to submit, also on a quarterly basis, commitment, obligation, and expenditure data for the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund, the Counter-Islamic State of Iraq and Syria Train and Equip Fund, and for all security cooperation programs funded under the Defense Security Cooperation Agency in the Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide Account.54

DOD's June 2018 Cost of War report to Congress details $1.5 trillion in obligations associated with certain contingency operations from FY2001 through FY2018.55 That figure includes $757.1 billion for those conducted primarily in Iraq—Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation New Dawn (OND), and Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); $727.7 billion for those conducted primarily in Afghanistan—Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS); and $27.8 billion for those conducted primarily in the United States (see Table 2 and Figure 7).56

Table 2. OCO/GWOT Obligations of Major DOD Contingency Operations Since FY2001

(in billions of dollars)

|

Primary Country |

Major Operations |

Date(s) |

Cost ($) |

Description |

Related Missions |

||

|

Afghanistan |

Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) |

2001-December 2014 |

|

U.S. operation in response to 9/11 terrorist attacks; targeted Al Qaeda and Taliban; included operations in Afghanistan and other countries; succeeded by OFS. |

OEF-Horn of Africa (continues under OFS as Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa);a OEF-Trans Sahara (continues under OFS as Operation Juniper Shield);b OEF-Philippines (concluded in summer 2014);c OEF-Caribbean and Central America; Operation Spartan Shield (continues under OFS);d Other classified worldwide counterterrorism missions. |

||

|

Afghanistan |

Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS) |

January 2015-Current |

|

U.S. contribution to NATO Resolute Support mission to train, advise, and assist Afghan Security Forces; successor to OEF. |

Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa; Operation Spartan Shield |

||

|

Subtotal, Afghanistan |

|

||||||

|

Iraq |

Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) |

March 2003-September 2010- |

|

U.S.-led invasion of Iraq to oust Saddam Hussein; buildup of forces began in September 2002 for invasion in March 2003 |

|||

|

Iraq |

Operation New Dawn (OND) |

September 2010-December 2011 |

|

Focus on stability operations and training, advising, and assisting Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). |

Successor to OIF. |

||

|

Iraq/Syria |

Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) |

August 7, 2014-Current |

|

U.S. operation targeting the Islamic State (ISIS/ISIL) in Iraq and Syria; began with airstrikes and expanded to include ground forces. |

Office of Security Cooperation–Iraq; Other OND-related activities; Operation Yukon Journey in the Middle Eastg; Northwest Africa Counterterrorismh; East Africa Counterterrorismi; and Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines (OPE-P)j. |

||

|

Subtotal, Iraq |

|

||||||

|

Libya |

Operation Odyssey Lightning |

2016 |

|

U.S. warplanes struck Islamic State training camp in western Libya near the border with Tunisia. |

Airstrike intended to support the Libyan government's (Government of National Accord) counter-Islamic State operations.k |

||

|

United States |

Operation Noble Eaglef |

2001-Current |

|

Response to defend the U.S. homeland in the wake of the attacks of 9/11. |

Provides for enhanced security for military bases and other homeland defense activities. |

||

|

Total |

|

Source: Cost figures from Department of Defense, Cost of War report, June 2018; names and descriptions of operations from CRS research, DOD sources.

Notes: Figures may not include funding for certain overseas contingency operations, including three recently classified missions targeting militants affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State—Operation Yukon Journey in the Middle East, and Northwest Africa Counterterrorism and East Africa Counterterrorism in Africa. See the Limitations to Cost of War Data section below—as well as Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines (OPE-P).

a. OEF-Horn of Africa is headquartered at the U.S. Navy's Combat Command Support Activity at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti. It supports special operations forces conducting counterterrorism operations, civil affairs, and military information support operations in the Horn of Africa.

b. OEF-Trans Sahara, now known as Operation Juniper Shield, constitutes DOD's support to State Department-led Trans-Sahara Counter Terrorism Program (TSCTP); program also supports the Commander of U.S. Africa Command in carrying out the National Military Strategy for U.S. military operations in ten partner nations (Algeria, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Tunisia); the operation is currently funded in the DOD base budget.

c. The mission of OEF-Philippines was to advise and assist the Armed Forces of the Philippines in combatting terrorism, and specifically the activities of the terrorist group Abu Sayaf, in the Philippines. See table note below for later mission Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines (OPE-P).

d. Operation Spartan Shield contributes to U.S. Central Command missions.

e. Figure includes amounts for Operation New Dawn.

f. Initially funded with supplemental appropriations, ONE was transferred to the base budget in 2005. ONE obligations have totaled less than $1 billion since FY2008, according to DOD.

g. According to the Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, Operation Inherent Resolve and Other Overseas Contingency Operations, through September 30, 2018, "On February 9, 2018, the Secretary of Defense designated three new named contingency operations: Operation Yukon Journey, and operations in Northwest Africa and East Africa. These operations, which are classified, seek to degrade al Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated terrorists in the Middle East and specific regions of Africa."

j. According to the Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, Operation Inherent Resolve Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines, through September 30, 2018, "The Secretary of Defense designated OPE-P as a contingency operation in 2017 to support the Philippine government and military in their efforts to isolate, degrade, and defeat Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) affiliates and other terrorist organizations in the Philippines." The report references "$100.2 million in DoD obligations for OPE-P reported in FY2018."

k. The Administration's November 2016 amendment to the OCO budget included $20 million in funding to support U.S. counter-ISIL efforts and to finance the incremental Navy and Air Force cost of operations, flying hours, and deployments in Libya. See DOD Overview: Overseas Contingency Operations Budget Amendment FY2017, Figure 1 footnote.

l. Note this total reflects DOD obligations for selected overseas contingency operations and is different than the total OCO/GWOT figure cited earlier in this report, which reflects OCO/GWOT budget authority. Budget authority is provided by law to incur financial obligations; obligations are binding agreements that will result in outlays.

|

Figure 7. DOD OCO/GWOT Obligations, FY2001-FY2018 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: DOD, Cost of War report, June 2018. Notes: ONE obligations have totaled less than $1 billion since FY2008. |

Limitations to Cost of War Data

DOD's quarterly Cost of War reports are intended to provide Congress, GAO, and other stakeholders insight into the how the department obligates war-related appropriations. The reports include base and OCO obligations related to war activities, as well as obligation data broken down by certain major operations, service, component, agency, and appropriation.

However, as GAO has noted, "the proportion of OCO appropriations not associated with specific operations identified in the statutory Cost of War reporting requirement has trended upward" in part because the criteria DOD uses for making OCO funding requests is outdated and not always used.57

More recently, the June 2018 Cost of War report does not appear to reference three recently classified overseas contingency operations targeting militants affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS): Operation Yukon Journey in the Middle East, Northwest Africa Counterterrorism, and East Africa Counterterrorism.58

Some observers have noted other limitations to Cost of War reports, such as incomplete accounting of costs, limited distribution of the documents and underlying data, and formatting that makes it difficult to reconcile the data with information contained in budget justification documents.

State/USAID

Between FY2001 and FY2018, Congress appropriated a total of $154 billion in OCO funds for State Department and USAID. For FY2018 (the most recent full-year appropriations for foreign affairs agencies), OCO funding amounted to 22% of the total appropriations for State Department, Foreign Operations and Related Programs appropriation.

The Obama Administration's FY2012 International Affairs budget request was the first to include a request for OCO funds for "extraordinary and temporary costs of operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan."59 At the time, the Administration indicated that the use of this designation was intended to provide a transparent, whole-of-government approach to the exceptional war-related costs incurred in those three countries, thus better aligning the associated military and civilian costs. This first foreign affairs OCO request identified the significant resource demands placed on the State Department as a result of the transitions from military-led to civilian-led missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the importance of a stable Pakistan for the U.S. effort in Afghanistan.

The FY2012 foreign affairs OCO request included:

- for Iraq, funding for the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, consulates throughout Iraq, security costs in light of the then-planned U.S. military withdrawal, a then-planned civilian-led Police Development and Criminal Justice Program, military and development assistance in Iraq, and oversight of U.S. foreign assistance through the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction;

- for Afghanistan, funding to strengthen the Afghan government and build institutional capacity, support State/USAID and other U.S. government agency civilians deployed in Afghanistan, provide short-term economic assistance to address counterinsurgency and stabilization efforts, and provide oversight of U.S. foreign assistance programs in Afghanistan through the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction; and

- for Pakistan, funding to support U.S. diplomatic presence and diplomatic security in Pakistan, provide Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Funds (PCCF) to train and equip Pakistani forces to eliminate insurgent sanctuaries and promote stability and security in neighboring Afghanistan and the region.

In subsequent years, the Administration designated certain State Department activities in Syria and other peacekeeping activities as OCO, and Congress accepted and broadened this expanded use of OCO in annual appropriations. In the FY2017 budget request, the Administration further broadened its use of State OCO funds, applying the designation to funds for countering Russian aggression, counterterrorism, humanitarian assistance, and aid to Africa. In addition to OCO funds requested through the normal appropriations process, the Administration in recent years requested emergency supplemental funding (designated as OCO) to support State/USAID efforts in countering the Islamic State and to respond to global health threats such as the Ebola and Zika viruses.

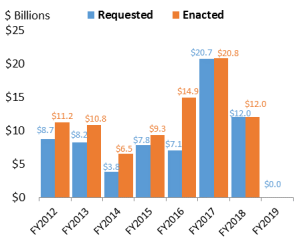

For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested no OCO/GWOT funding for the Department of State and USAID, although the FY2019 House and Senate SFOPS bills (H.R. 6385 and S. 3108, 115th Congress) would have appropriated approximately $8 billion in OCO-designated funding for various priorities.

The estimated $154.1 billion in emergency and OCO/GWOT appropriations enacted to date for State/USAID includes major non-war-related programs, such as aid for the 2004 tsunami along Indian Ocean coasts, 2010 earthquake in Haiti, 2013 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and 2015 worldwide outbreak of the Zika virus; as well as diplomatic operations (e.g., paying staff, providing security, and building and maintaining embassies). OCO/GWOT has also funded a variety of foreign aid programs, ranging from the Economic Support Fund to counter-narcotics in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq, among other activities in other countries.

Figure 8 depicts the emergency or OCO appropriations for foreign affairs activities. Since 2012, when the OCO designation was first used for foreign affairs, more OCO funds have been appropriated than were requested each year, and those have also been authorized to be used in additional countries.

|

Figure 8. State/USAID OCO Funding, FY2012-FY2019 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: Department of State Congressional Budget Justifications, FY2014, FY2015, FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018, P.L. 114-254 and P.L. 115-31, P.L. 115-141. Note: Totals include net rescissions. FY2019 appropriations have not been enacted. |

DHS (USCG)60

Since January 2002, approximately $3 billion of post-9/11 emergency and OCO-designated funding has been provided to the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) for its traditional homeland security missions and for USCG operations in support of U.S. Navy activities.61 This funding has been provided at various times as either an appropriation to the Coast Guard's operating expenses accounts, or as a transfer from Navy accounts to the Coast Guard.

Open-source information on the use of those funds has varied. One FY2009 supplemental appropriations request included funding as a transfer, with the intent of funding "Coast Guard operations in support of OIF and OEF, as well as other classified activities."62 The FY2017 OCO request for annual appropriations for Navy Operations and Maintenance included $163 million for Coast Guard operational support for the deployment of patrol boats to the Northern Arabian Gulf and a port security unit to Guantanamo Bay, among other pay and equipment expenses.63

FY2019 OCO Funding

President's FY2019 OCO Request

Budget Deal Prompts OCO-to-Base Shift

The Trump Administration initially requested a total of $89 billion in OCO funding for FY2019. All the funding was requested by DOD.64

In an amendment to the budget after Congress raised the BCA spending caps as part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), the Administration removed the OCO designation from $20 billion of the funding, in effect, shifting that amount into the DOD base budget request.65

In a statement on the budget amendment, Mulvaney said the request fixes "long-time budget gimmicks" in which OCO funding has been used for base budget requirements.66 Beginning in FY2020, "the Administration proposes returning to OCO's original purpose by shifting certain costs funded in OCO to the base budget where they belong," he wrote.67

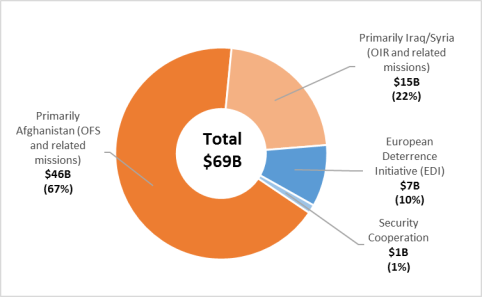

OCO Funding by Operation

Of the revised amount of $69 billion requested for DOD OCO funding in FY2019:

- $46.3 billion (67%) was for Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS) in Afghanistan and related missions;

- $13 billion (22%) for Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) in Iraq and Syria and related missions;

- $4.8 billion (9%) for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) to boost the U.S. military presence in eastern Europe to deter Russian military aggression; and

- $0.9 billion (1%) for security cooperation (see Figure 9).68

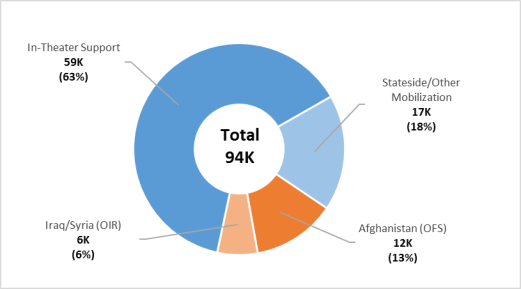

The FY2019 OCO budget assumes a total force level (average annual troop strength) of 93,796 personnel. That figure includes:

- 11,958 primarily in Afghanistan (OFS);

- 5,765 primarily in Iraq and Syria (OIR);

- 59,463 for in-theater support; and

- 16,610 primarily in the continental United States (CONUS) or otherwise mobilized (see Figure 10).

The number of personnel actually in-country or in-theater at any given time may exceed or fall below those assumed levels. The FY2019 force level assumes an increase of 3,153 personnel (3.5%) from the FY2018 assumed level, all of which is assumed for in-theater support.69 (For analysis of troop level and budget trends, see the section, "Trends in OCO Funding and Troop Levels," earlier in this report.)

As previously discussed, DOD acknowledges "OCO funding has not declined at the same rate as the in-country troop strength … due to the fixed, and often inelastic, costs of infrastructure, support requirements, and in-theater presence to support contingency operations." The departments lists the following as OCO cost drivers:

- In-theater support, including infrastructure costs like command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence (C4I) and base operations for U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) locations;

- Persistent demand for combat support such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets used to enhance force protection;

- Equipment reset, which lags troop level changes and procurement of contingency-focused assets like munitions, unmanned aerial vehicles and force protection capabilities that may not be linked directly to in-country operations; and

- International programs and deterrence activities, which are linked to U.S. engagement in contingency operations and support U.S. interests but are not directly proportional to U.S. troop presence.70

OCO Funding by Functional Category

DOD also breaks down the FY2019 OCO budget request by functional category (see Table 3). By this measure, the largest portion of OCO funding was $20 billion for in-theater support, followed by operations and force protection (including the incremental cost of military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other countries), at $14.7 billion; and unspecified classified programs, at $9.9 billion.

|

Functional/Mission Category |

FY2019 Budget Request |

% of Total |

|

In-Theater Support |

20.0 |

29% |

|

Operations/Force Protection |

14.7 |

21% |

|

Classified Programs |

9.9 |

14% |

|

Equipment Reset and Readiness |

8.7 |

13% |

|

European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) |

6.5 |

9% |

|

Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF) |

5.2 |

8% |

|

Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF) |

1.4 |

2% |

|

Support for Coalition Forces |

1.1 |

2% |

|

Security Cooperation |

0.9 |

1% |

|

Joint Improvised-Threat Defeat |

0.6 |

1% |

|

Total |

69 |

100% |

Sources: Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Defense Budget Overview, FY2019 budget request, Figure 4.4: OCO Functional/Mission Category, p. 4-4; Congressional Budget Office, Funding for Overseas Contingency Operations and Its Impact on Defense Spending, October 23, 2018.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), approximately $47 billion (68%) of the FY2019 OCO budget request consists of enduring activities—that is, "those that would probably continue in the absence of overseas conflicts"—that could be funded in the DOD base budget.71 CBO associates enduring activities with the following DOD functional categories: in-theater support, classified programs, equipment reset and readiness, European Deterrence Initiative, security cooperation, and joint improvised-threat defeat.

Differing OCO Projections

Executive Branch budget documents for FY2019 show differing projections for how much OCO would be apportioned over the Future Years Defense Program (also known as the FYDP, pronounced "fiddip," the five-year period from FY2019 through FY2023).72 For example, Table 1-11 in DOD's National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2019, citing OMB data, projects five-year OCO funding at $359 billion. However, Table 1-9 of the same document puts the figure at $149 billion after assuming a higher amount of OCO funding shifting into the base budget.73

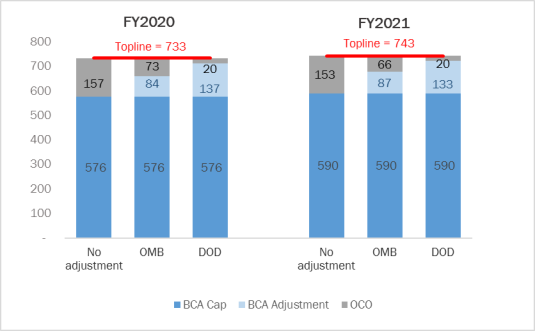

According to OMB, the President's initial FY2019 budget request projected increasing caps on defense discretionary base budget authority by $84 billion (15%) to $660 billion in FY2020 and by $87 billion (15%) to $677 billion in FY2021.74 It also projected defense funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) totaling $73 billion in FY2020 and $66 billion in FY2021.75 Thus, projected defense discretionary funding would total $733 billion in FY2020 and $743 billion in FY2021.

FY2019 DOD budget documents show the same defense discretionary topline for FY2020 and FY2021.76 But they list an "Outyears Placeholder for OCO" of $20 billion in fiscal years FY2020-FY2023, and an "OCO to Base" amount of $53 billion in FY2020 and $45.8 billion in each year from FY2021-FY2023. The documents do not break down what accounts or activities are included in these amounts.

The emergence of any new contingencies or conflicts would likely change DOD assumptions about OCO needs.

Congressional Action on the FY2019 OCO Request and Appropriations

Congress has appropriated a total of $68.8 billion for DOD OCO funding in FY2019, including the following amounts:

- $67.9 billion in defense funds provided in the Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-245), which Congress passed on September 26, 2018; and

- $921 million in defense funds provided in the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 115-244), which Congress passed on September, 21, 2018.

For the Department of State and USAID, as well as the Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Coast Guard, FY2019 OCO levels have not yet been determined. They remain at prorated FY2018 levels because of continuing resolutions (CR) to fund certain agencies through December 21, 2018.77

The FY2019 House and Senate SFOPS bills (H.R. 6385 and S. 3108, 115th Congress) would have appropriated approximately $8 billion in OCO-designated funding for various priorities. The House committee-reported version of the Homeland Security appropriations bill (H.R. 6776, 115th Congress) would not have appropriated any OCO/GWOT funding for the Coast Guard, while the Senate committee-reported version of the bill (S. 3109, 115th Congress) would have appropriated $165 million for OCO/GWOT funding for the Coast Guard.78

Issues for Congress

How Could the BCA Affect Future OCO Levels?

Any decision by the 116th Congress to change discretionary defense and nondefense spending limits that remain in effect for FY2020 and FY2021 under the Budget Control Act (BCA; P.L. 112-25) could impact future OCO funding levels.

Lawmakers may consider the following questions:

- Will Congress keep the BCA as is and rely on OCO funding that is not subject to the caps to meet agency requirements?

- Will Congress repeal the BCA and use less OCO funding?

- Will Congress amend the BCA limits for future years and continue to use OCO funding, as it has in the past?

- Will Congress significantly reduce DOD and international affairs funding to stay within the BCA caps and not use OCO funding?

In a November 2018 report, the National Defense Strategy Commission, a bipartisan panel created by Congress, issued recommendations related to OCO and the BCA.79 Recommendation No. 24 states, "Congress should eliminate the final two years of caps under the BCA." Recommendation 29 states, "To better prepare for major-power competition, Congress should gradually integrate OCO spending back into the base Pentagon budget. This also requires a dollar-for-dollar increase in the BCA spending caps, should they remain in force, so that this transfer does not result in an overall spending cut."80

Will Congress Continue to Use OCO for State/USAID?

Both House and Senate FY2019 committee-reported appropriations bills from the 115th Congress included about $8 billion in OCO funding for State/USAID. It remains to be seen if the 116th Congress will pass this OCO level as requested or extend the continuing resolution.

How Much Would Defense Spending Caps Increase under the Administration's Budget Plans?

Congress could enact legislation to authorize and appropriate a level of base and OCO spending to meet current or revised discretionary defense spending caps in any number of ways.

In FY2019 budget documents from OMB and DOD, the Trump Administration projected increasing defense spending in FY2020 and FY2021 beyond the statutory limits of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), but by differing amounts based on differing OCO projections. These figures serve as possible scenarios or options for Congress to consider.

FY2020 Projections

According to OMB budget documents, the President's initial FY2019 budget request projected $733 billion in defense discretionary spending in FY2020, including a base budget of $660 billion (which assumes an $84 billion, or 15%, increase in the BCA defense cap—or repeal of the legislation altogether) and an OCO defense budget of $73 billion (see Figure 11).81

According to DOD budget documents, the President's revised FY2019 budget request projected $733 billion in defense discretionary spending in FY2020, including a base budget of $713 billion (which assumes a $137 billion, or 24%, increase in the BCA defense cap—what would be the largest increase to the BCA defense caps yet—or repeal of the legislation altogether) and an OCO budget of $20 billion.82

Alternatively, assuming no change in the cap and congressional support for the Administration's projected $733 billion topline in FY2020, Congress could keep the BCA defense cap unchanged at $576 billion and designate an additional $157 billion for OCO.

FY2021 Projections

According to OMB budget documents, the President's initial FY2019 budget request projected $743 billion in defense discretionary spending in FY2021, including a base budget of $677 billion (which assumes an $87 billion, or 15%, increase in the BCA defense cap—or repeal of the legislation altogether) and an OCO budget of $66 billion (see Figure 11).83

According to DOD budget documents, the President's revised FY2019 budget request projected $743 billion in defense discretionary spending in FY2021, including a base budget of $723 billion (which assumes a $133 billion, or 23%, increase in the BCA defense cap—or repeal of the legislation altogether) and an OCO budget of $20 billion.84

Alternatively, assuming no change in the cap and congressional support for the Administration's projected $743 billion topline in FY2020, Congress could keep the BCA defense cap unchanged at $590 billion and designate an additional $153 billion for OCO.

Flat FYDP?

As previously discussed, these figures would change with different toplines for the national defense budget function (050).85

Former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and the National Defense Strategy Commission have recommended that Congress increase the defense budget between 3% and 5% a year above inflation ("real growth") to meet U.S. strategic goals.86

President Donald Trump has said the discretionary defense spending request would total $700 billion in FY2020, a decrease of 2% in nominal terms from FY2019. Trump said, "We know what the budget—the new budget is for the Defense Department. It will probably be $700 billion."87 However, some media outlets have since reported that the President intends to request a discretionary defense budget of $750 billion in FY2020.88

Senator James Inhofe, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Representative Mac Thornberry, ranking member of the House Armed Services Committees in the 116th Congress, have argued, "Any cut in the defense budget would be a senseless step backward."89 Thornberry has also said transferring recurring OCO costs into the regular budget "makes sense … it makes for more predictable budgeting, but it's all about what happens on the topline."90 Representative Adam Smith, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee in the 116th Congress, has said of the defense budget: "I think the number is too high, and it's certainly not going to be there in the future … We've got a debt, we've got a deficit, we've got infrastructure problems, we've got healthcare, education—there's a whole lot that is necessary to make our country safe, secure, and prosperous."91

Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan has talked about a flat topline for national defense: "When you look at the $700 billion, it's not just for one year drop down, [or] a phase, it's a drop and then held constant" over the FYDP.92 Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer David Norquist, who is also performing the duties of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, at one time was reportedly preparing two budgets for FY2020—one assuming $733 billion for national defense and another assuming $700 billion.93

An analyst has noted "returning enduring OCO costs to the base budget, particularly a vast majority of those enduring costs over a short period as DOD has outlined, could significantly complicate an agreement between congressional Democrats and Republicans to increase both the defense and nondefense BCA budget caps for FY2020 and FY2021."94

How Much OCO Funding Could Shift to the DOD Base Budget?

As analyst noted, "OCO has become an even less-defined pot of money … Congress needs to properly question the DOD budget planners on the future of OCO."95

In a January 2017 report, GAO concluded, "Without a reliable estimate of DOD's enduring OCO costs, decision makers will not have a complete picture of the department's future funding needs or be able to make informed choices and trade-offs in budget formulation and decision making."96

The department states it has not fully estimated those costs in part because of the BCA.97 In a response to GAO, DOD wrote, "Developing reliable estimates of enduring OCO costs is an important first step to any future effort to transition enduring OCO costs to the base budget. In the context of such an effort, the Department would consider developing and reporting formal estimates of those costs. However, until there is sufficient relief from the budgetary caps established in the Budget Control Act of 2011, the Department will need OCO to finance counterterrorism operations, in particular [OFS] and [OIR]."98

In an October 2018 report, the Congressional Budget Office estimated OCO funding for DOD enduring activities—that is, those that would probably continue in the absence of overseas conflicts—totaled more than $50 billion a year (in 2019 dollars) from 2006 to 2018—and are projected to total about $47 billion a year starting in FY2020.99

This figure appears to be consistent with projections published by DOD. According to the department's FY2019 budget documents, DOD projected $53 billion for "OCO to Base" in FY2020 and $45.8 billion for "OCO to Base" for FY2021 through FY2023.

How Does OCO Funding Affect Defense Planning?

Some analysts have concluded:

Uncertainty created by current reliance on OCO, particularly to fund base budget needs, could be detrimental to national security on three levels: (a) by undermining budget controls and contributing thereby to larger deficits, (b) by generating insecurity in the defense workforce and in defense suppliers, and (c) by creating long-term uncertainty in defense planning. The alternative, transitioning longer-term OCO expenses to the base budget, could be achieved through a combination of increased budget caps, targeted cuts in inefficient Defense programs, and increased revenues.100

For example, a potential enduring activity in the OCO budget is the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). It was previously known as the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), an effort that began in June 2014 to increase the number of U.S. military personnel and prepositioned equipment in Central and Eastern Europe intended in part to reassure NATO allies after Russia's military seized Crimea.101 As some analysts have noted, "Because it is in the OCO part of the budget request, EDI funding does not include a projection for how much funding will be allocated in future years, which can create uncertainty in the minds of allies and adversaries alike about the U.S. military's commitment to the program."102 On the other hand, some contend that it is precisely EDI's flexibility that allows the commander of European Command to quickly respond to changing security and posture needs in Europe, and ensure that monies intended for European deterrence will not be redirected to other DOD priorities.103

In its November 2018 report, the National Defense Strategy Commission quoted the late military strategist Bernard Brodie, who wrote "strategy wears a dollar sign."104 The panel concluded that relying on OCO funding to increase the defense budget "is not the way to provide adequate and stable resources" for the type of great power competition outlined in the Secretary of Defense's 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), which calls for the United States to bolster its competitive military advantage relative to threats posed by China and Russia:

Because of budgetary constraints imposed by the BCA, lawmakers and the Department of Defense have increasingly relied upon the overseas contingency operations (OCO) fund to pay for warfighting operations in the greater Middle East, as well as other activities and initiatives. Yet this approach to resourcing has produced problems and distortions of its own. For one thing, the amount of money devoted to OCO since the BCA was enacted no longer corresponds to warfighting operations in the greater Middle East. Furthermore, such operations are no longer a top priority as articulated in the NDS. Finally, reorienting the military toward high-end competition and conflict will require new capabilities beyond the current program of record. OCO is not the way to provide adequate and stable resources for such a long-term endeavor, given its lack of predictability and the limitations on what OCO funds can be used to buy."105

Appendix A. Statutes, Guidance, and Regulations

The designation of funding as emergency requirements or for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) is governed by several statues as well as Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance and the Department of Defense (DOD) Financial Management Regulation (FMR).

The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (BBEDCA) of 1985

BBEDCA, as amended, includes the statutory definitions of emergency and unanticipated as they relate to budget enforcement through sequestration. The act also allows for appropriations to be designated by Congress and the President as emergency requirements or for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism. Such appropriations are effectively exempt from the statutory discretionary spending limits.106

|

Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (2 U.S.C. §900) Definitions The term "emergency" means a situation that- requires new budget authority and outlays (or new budget authority and the outlays flowing therefrom) for the prevention or mitigation of, or response to, loss of life or property, or a threat to national security; and (B) is unanticipated. The term "unanticipated" means that the underlying situation is- sudden, which means quickly coming into being or not building up over time; urgent, which means a pressing and compelling need requiring immediate action; unforeseen, which means not predicted or anticipated as an emerging need; and (D) temporary, which means not of a permanent duration. Notes: As amended by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25). |

|

Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (2 U.S.C. §901) Enforcing Discretionary Spending Limits Enforcement Sequestration Within 15 calendar days after Congress adjourns to end a session there shall be a sequestration to eliminate a budget-year breach, if any, within any category. Eliminating a breach Each non-exempt account within a category shall be reduced by a dollar amount calculated by multiplying the enacted level of sequestrable budgetary resources in that account at that time by the uniform percentage necessary to eliminate a breach within that category. Adjustments to discretionary spending limits Concepts and definitions When the President submits the budget under section 1105 of title 31, OMB shall calculate and the budget shall include adjustments to discretionary spending limits (and those limits as cumulatively adjusted) for the budget year and each outyear to reflect changes in concepts and definitions. Such changes shall equal the baseline levels of new budget authority and outlays using up-to-date concepts and definitions, minus those levels using the concepts and definitions in effect before such changes. Such changes may only be made after consultation with the Committees on Appropriations and the Budget of the House of Representatives and the Senate, and that consultation shall include written communication to such committees that affords such committees the opportunity to comment before official action is taken with respect to such changes. Sequestration reports When OMB submits a sequestration report under section 904(e), (f), or (g) of this title for a fiscal year, OMB shall calculate, and the sequestration report and subsequent budgets submitted by the President under section 1105(a) of title 31 shall include adjustments to discretionary spending limits (and those limits as adjusted) for the fiscal year and each succeeding year, as follows: (A) Emergency appropriations; overseas contingency operations/global war on terrorism If, for any fiscal year, appropriations for discretionary accounts are enacted that - the Congress designates as emergency requirements in statute on an account by account basis and the President subsequently so designates, or the Congress designates for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism in statute on an account by account basis and the President subsequently so designates, the adjustment shall be the total of such appropriations in discretionary accounts designated as emergency requirements or for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism, as applicable. Notes: As amended by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25). |

Title 10, United States Code—Armed Forces

10 U.S.C. 101—Definitions

Section 101 provides definitions of terms applicable to Title 10. While it does not define overseas contingency operations, it does include a definition of a contingency operations.

|

10 U.S.C. §101- Definitions (13) The term "contingency operation" means a military operation that- is designated by the Secretary of Defense as an operation in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing military force; or results in the call or order to, or retention on, active duty of members of the uniformed services under section 688, 12301(a), 12302, 12304, 12304a, 12305, or 12406 of this title, chapter 15 of this title, section 712 of title 14, or any other provision of law during a war or during a national emergency declared by the President or Congress. |

Administration and Internal Guidance

In addition to statutory requirements, the DOD and the Department of State are subject to guidance on OCO spending from the Administration. In October 2006, under the Bush Administration, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon England directed the services to break with long-standing DOD regulatory policies and expand their request for supplemental funding to reflect incremental costs related to the "longer war on terror." There was no specific definition for the "longer war on terror," now one of the core missions of the DOD.

In February 2009, at the beginning of the Obama Administration, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued updated budget guidance that required DOD to move some OCO costs back into the base budget. However, within six months of issuing the new criteria, officials waived restrictions related to pay and that would have prohibited end-strength growth.107 In a letter from OMB to the then-Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Robert Hale, the agency characterized its 2009 criteria as "very successful" for delineating base and OCO spending but stated, "This update clarifies language, eliminates areas of confusion and provides guidance for areas previously unanticipated."108 GAO subsequently reported that the revised guidance significantly changed the criteria used to build the fiscal year 2010 OCO funding request by:

- specifying stricter definitions for repair and procurement of equipment;

- limiting applicability of OCO funds for RDT&E;

- excluding pay and allowances for end-strength above the level requested in the budget;

- excluding enduring family support initiatives; and

- excluding base realignment and closures (BRAC) amounts.109

OMB again revised its guidance in September 2010 following a number of GAO reports that had concluded DOD reporting on OCO costs was of "questionable reliability," due in part to imprecisely defined financial management regulations related to OCO spending.110

(as of September 9, 2010)

|

Item |

Definition of Criteria |

|

Geographic area covered/"Theater of operations"(for non-classified war/overseas contingency operations funding) |

Geographic areas in which combat or direct combat support operations occur: Iraq , Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, the Horn of Africa, Persian Gulf and Gulf nations, Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, the Philippines, and other countries on a case-by-case basis. Note: OCO budget items must also meet the criteria below. |

|

Major Equipment (General) |

Replacement of losses that have occurred but only for items not already programmed for replacement in the Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP)— no accelerations. Accelerations can be made in the base budget. Replacement or repair to original capability (to upgraded capability if that is currently available) of equipment returning from theater. The replacement may be a similar end item if the original item is no longer in production. Incremental cost of non-war related upgrades, if made, should be included in the base. Purchase of specialized, theater-specific equipment. Funding must be obligated within 12 months. |

|

Ground Equipment Replacement |

Combat losses and washouts (returning equipment that is not economical to repair); replacement of equipment given to coalition partners, if consistent with approved policy; in-theater stocks above customary equipping levels on a case-by-case basis. |

|

Equipment Modifications (Enhancements) |

Operationally required modifications to equipment used in theater or in direct support of combat operations, for which funding can be obligated in 12 months, and that is not already programmed in FYDP. |

|

Munitions |

Replenishment of munitions expended in combat operations in theater. Training ammunition for theater-unique training events is allowed. Forecasted expenditures are not allowed. Case-by-case assessment for munitions where existing stocks are insufficient to sustain theater combat operations. |

|

Aircraft Replacement |

Combat losses, defined as losses by accident or by enemy action that occur in the theater of operations. |

|

Military Construction |

Facilities and infrastructure in the theater of operations in direct support of combat operations. The level of construction should be the minimum to meet operational requirements. At non-enduring locations, facilities and infrastructure for temporary use are covered. At enduring locations, construction requirements must be tied to surge operations or major changes in operational requirements and will be considered on a case-by-case basis. |

|

Research and Development |

Projects required for combat operations in these specific theaters that can be delivered in 12 months. |

|

Operations |

Direct War costs:

Within the theater, the incremental costs above the funding programmed in the base budget:

Indirect War Costs: Indirect war costs incurred outside the theater of operations will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. |

|

Health |

Short-term care directly related to combat. Infrastructure that is only to be used during the current conflict. |

|

Personnel (Incremental Pay) |

Incremental special pays and allowances for Service members and civilians deployed to a combat zone; incremental pay. Special pays and allowances for Reserve Component personnel mobilized to support war missions. |

|

Special Operations Command |

Operations and equipment that meet the criteria in this guidance. |

|

Prepositioned Supplies and Equipment |

Resetting in-theater stocks of supplies and equipment to pre-war levels. Excludes costs for reconfiguring prepositioned sets or for maintaining them. |

|

Security Force Funding |

Training, equipping, and sustaining Iraqi and Afghan military and police forces. |

|

Fuel |

War fuel costs and funding to ensure that logistical support to combat operations is not degraded due to cash losses in DoD's baseline fuel program. Would fund enough of any base fuel shortfall attributable to fuel price increases to maintain sufficient on-hand cash for the Defense Working Capital Funds to cover seven days' disbursements. (This would enable the Fund to partially cover losses attributable to fuel cost increases.) |

|

Exclusions from war/overseas contingency funding - Appropriately funded in the base budget |

|

|

Training equipment |

Training vehicles, aircraft, ammunition, and simulators. Exception: training base stocks of specialized, theater-specific equipment that is required to support combat operations in the theater of operations, and support to deployment-specific training described above. |

|

Equipment Service Life Extension Programs (SLEPs) |

Acceleration of SLEPs already in the FYDP. |

|

Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) |

BRAC projects. |

|

Family Support Initiatives |

Family support initiatives to include the construction of childcare facilities; funding private-public partnerships to expand military families' access to childcare; and support for service members' spouses professional development. |

|

Industrial Base Capacity |

Programs to maintain industrial base capacity (e.g. "war-stoppers"). |

|

Personnel |

Recruiting and retention bonuses to maintain end-strength. Basic Pay and the Basic allowances for Housing and Subsistence for permanently authorized end strength. Individual augmentees will be decided on a case-by-case basis. Office of Security Cooperation Support for the personnel, operations, or the construction or maintenance of facilities, at U.S. Offices of Security Cooperation in-theater. |

|

Special Situations |

|

|

Reprogrammings and paybacks |

Items proposed for increases in reprogrammings or as payback for prior reprogrammings must meet the criteria above. |

Source: Letter from Steven M. Kosiak, Associate Director for Defense and Foreign Affairs, OMB, to Robert Hale, Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller, "Revised War Funding Criteria," September 9, 2010.

DOD Financial Management Regulations

DOD incorporated the September 2010 OMB criteria for war costs into the Financial Management Regulation. Table 1 includes the general cost categories DOD uses in accounting for costs of contingency operations.

|

Category |

Activity |

|

Personnel |

Incremental pay and allowances of DOD military and civilians participating in or supporting a contingency operation. |

|

Personnel Support |

Materials and services required to support Active and Reserve Component personnel and DOD civilian personnel engaged in the contingency operation. |