This report addresses frequently asked questions about the federal and state standards that regulate fuel economy and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new passenger cars and light trucks. The regulations include the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards promulgated by the U.S. Department of Transportation's National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Light-Duty Vehicle GHG emissions standards promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and California's Advanced Clean Car program. The agencies refer to the standards collectively as the National Program. The report looks at the origins of the standards, reviews the current and proposed future regulations, and discusses recent actions and relevant vehicle industry trends. It also examines the relationship between the California and the federal vehicle emissions programs.

What Is NHTSA's Authority to Regulate the Fuel Economy of Motor Vehicles?

NHTSA derives its authority to regulate the fuel economy of motor vehicles from the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 (EPCA; P.L. 94-163) as amended by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA; P.L. 110-140).

The origin of federal fuel economy standards dates to the mid-1970s. The oil embargo of 1973-1974 imposed by Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the subsequent tripling in the price of crude oil brought the fuel economy of U.S. automobiles into sharp focus. The fleet-wide fuel economy of new passenger cars had declined from 15.9 miles per gallon (mpg) in model year (MY) 1965 to 13.0 mpg in MY 1973.1 In an effort to reduce dependence on imported oil, EPCA established CAFE standards for passenger cars beginning in MY 1978 and for light trucks2 beginning in MY 1979. The standards required each auto manufacturer to meet a target for the sales-weighted fuel economy of its entire fleet of vehicles sold in the United States in each model year. Fuel economy—expressed in miles per gallon (mpg)—was defined as the average mileage traveled by a vehicle per gallon of gasoline or equivalent amount of other fuel.

EPCA required NHTSA to establish and amend the CAFE standards; promulgate regulations concerning procedures, definitions, and reports; and enforce the regulations. CAFE standards, and new-vehicle fuel economy, rose steadily through the late 1970s and early 1980s. After 1985, Congress did not revise the legislated standards for passenger cars, and they remained at 27.5 mpg until 2011. The light truck standards were increased to 20.7 mpg in 1996, where they remained until 2005.3

New-vehicle fuel economy began to rise again in the mid-2000s, due, in part, to a steady increase in gasoline prices that led many consumers to purchase smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles. NHTSA promulgated two sets of standards in the mid-2000s affecting the MY 2005-2007 and MY 2008-2011 light truck fleets, increasing their average fuel economy to 24.0 mpg. Further, Congress enacted EISA in 2007, which, among other provisions, revisited the CAFE standards. EISA required NHTSA to increase combined passenger car and light truck fuel economy standards to at least 35 mpg by 2020,4 up from the combined 26.6 mpg in 2007. Along with requiring higher vehicle standards, EISA changed the structure of the program (in part due to concerns about safety and consumer choice).5

What Is EPA's Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?

EPA derives its authority to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles from the Clean Air Act, as amended (CAA).6

In 1998, during the Clinton Administration, EPA General Counsel Jonathan Cannon concluded in a memorandum to the agency's Administrator that GHGs were air pollutants within the CAA's definition of the term, and therefore could be regulated under the CAA.7 Relying on the Cannon memorandum as well as the statute itself, a group of 19 organizations petitioned EPA on October 20, 1999, to regulate GHG emissions from new motor vehicles under CAA Section 202.8 That section directs the EPA Administrator to develop emission standards for "any air pollutant" from new motor vehicles "which, in his judgment cause[s], or contribute[s] to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."9 On August 28, 2003, EPA denied the petition10 because the agency determined that the CAA does not grant EPA authority to regulate carbon dioxide (CO2) and other GHG emissions based on their climate change impacts.11 Massachusetts, 11 other states, and various other petitioners challenged EPA's denial of the petition in a case that ultimately reached the Supreme Court.12

In April 2007, the Supreme Court held that EPA has the authority to regulate GHGs as "air pollutants" under the CAA.13 In the 5-4 decision, the Court determined that GHGs fit within the CAA's "unambiguous" and "sweeping definition" of "air pollutant."14 The Court's majority concluded that EPA must, therefore, decide whether GHG emissions from new motor vehicles contribute to air pollution that may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare, or provide a reasonable explanation why it cannot or will not make that decision.15 If EPA made a finding of endangerment, the CAA required the agency to establish standards for emissions of the pollutants.16

Following the Court's decision, the George W. Bush Administration's EPA did not respond to the original petition or make a finding regarding endangerment. Its only formal action following the Court decision was to issue a detailed information request, called an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR), on July 30, 2008.17 The Obama Administration's EPA, however, made review of the endangerment issue a high priority. On December 15, 2009, it promulgated findings that GHGs endanger both public health and welfare, and that GHG emissions from new motor vehicles contribute to that endangerment.18

With these findings, the Obama Administration initiated discussions with major stakeholders in the automotive and truck industries and with states and other interested parties to develop and implement vehicle GHG standards. Because CO2 from mobile source fuel combustion is a major source of GHG emissions, the White House directed EPA to work with NHTSA to align the GHG standards with CAFE standards. In addition, the CAA grants the state of California unique status to receive a waiver to issue motor vehicle emission standards provided that they are at least as stringent as federal ones and are necessary to meet "compelling and extraordinary conditions." California had already promulgated GHG emissions standards prior to 2009, for which it had requested an EPA waiver under provisions in the CAA. EPA granted California a waiver in July 2009, and President Obama directed EPA and NHTSA to align the federal fuel economy and GHG emission standards with those developed by California. The Administration referred to the coordinated effort as the National Program.

EPA and NHTSA promulgated joint rulemakings affecting MY 2012-2016 light-duty motor vehicles on May 7, 2010. These are known as the Phase 1 standards.19

What Is California's Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions from Motor Vehicles?20

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) derives its authority to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles from California Assembly Bill (AB) 1493.21

Questions of federal preemption of state regulations can arise when state law operates in an area that may also be of concern to the federal government. Under the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution,22 state law that conflicts with federal law must yield to the exercise of Congress's powers.23 When it acts, Congress can preempt state laws or regulations within a field entirely, preempt only state laws or regulations that conflict with federal law, or allow states to act freely.24

Title II of the CAA generally preempts states from adopting their own emission standards for new motor vehicles or engines.25 However, CAA Section 209(b) provides an exception to federal preemption of state vehicle emission standards:

The [EPA] Administrator shall, after notice and opportunity for public hearing, waive application of this section [the preemption of State emission standards] to any State which has adopted standards (other than crankcase emission standards) for the control of emissions from new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines prior to March 30, 1966, if the State determines that the State standards will be, in the aggregate, at least as protective of public health and welfare as applicable Federal standards.26

Only California can qualify for such a preemption waiver because it is the only state that adopted motor vehicle emission standards "prior to March 30, 1966."27 According to EPA records, since 1967, CARB has submitted over 100 waiver requests for new or amended standards or "within the scope" determinations (i.e., a request that EPA rule on whether a new state regulation is within the scope of a waiver that EPA has already issued).28

On July 22, 2002, California became the first state to enact legislation requiring reductions of GHG emissions from motor vehicles. The legislation, AB 1493, required CARB to adopt regulations requiring the "maximum feasible and cost-effective reduction" of GHG emissions from any vehicle whose primary use is noncommercial personal transportation.29 The reductions applied to motor vehicles manufactured in MY 2009 and thereafter. Under this authority, CARB adopted regulations on September 24, 2004, and submitted a request to EPA on December 21, 2005, for a preemption waiver.

In 2008, EPA denied California's request for a waiver.30 As explained in its decision, EPA concluded that "California does not need its GHG standards for new motor vehicles to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions" because "the atmospheric concentrations of these greenhouse gases is [sic] basically uniform across the globe" and are not uniquely connected to California's "peculiar local conditions."31 However, under the Obama Administration, EPA reconsidered and reversed the denial, and granted the waiver in 2009.32 In reversing its denial, EPA determined that it is the "better approach" for the agency to evaluate whether California "needs" state standards "to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions" based on California's need for its motor vehicle program as a whole, and not solely based on GHG standards addressed in the waiver request.33 Under this approach, EPA concluded that it cannot deny the waiver request because California has "repeatedly" demonstrated the need for its motor vehicle problem to address "serious" local and regional air pollution problems.34

Upon receiving the waiver, CARB joined EPA and NHTSA to develop the National Program. Three key provisions of the 2009 agreement between the Administration, the auto manufacturers, and the State of California were that EPA would grant California the waiver for MYs 2017-2025 (the agency did so on January 9, 2013),35 that California would accept vehicles complying with the federal greenhouse standards as meeting the California standards,36 and that the auto manufacturers would drop their suit against the California standards.

Additionally, the CAA allows other states to adopt California's motor vehicle emission standards under certain conditions.37 Section 177 requires, among other things, that such standards be identical to the California standards for which a waiver has been granted. States are not required to seek EPA approval under the terms of Section 177. Twelve other states have adopted California's GHG standards under these provisions, bringing approximately 35% of domestic automotive sales under the California program.38

What Are the Current CAFE and GHG Standards?

NHTSA and EPA promulgated the second (current) phase of CAFE and GHG emissions standards affecting MY 2017-2025 light-duty vehicles on October 15, 2012.39 Like the Phase 1 standards, the Phase 2 standards were preceded by a multiparty agreement, brokered by the White House. The Phase 2 agreement involved the State of California, 13 auto manufacturers, and the United Auto Workers union. The manufacturers agreed to reduce GHG emissions from new passenger cars and light trucks by about 50% by 2025, compared to 2010, with fleet-wide average fuel economy rising to nearly 50 miles per gallon. GHG emissions would be reduced to about 160 grams per mile by 2025 under the agreement (see Table 1).40

The standards are applicable to the fleet of new passenger cars and light trucks with gross vehicle weight rating less than or equal to 10,000 pounds sold within the United States. Fuel economy and carbon-related emissions are tested over EPA's two test cycles (the Federal Test Procedure (FTP-75), weighted at 55%; and the Highway Fuel Economy Test (HWFET), weighted at 45%).41 In addition to the standards for fleet-average fuel economy and GHG emissions (measured and referred to as "CO2-equivalent emissions" under the regulations),42 the rule also includes emission caps for tailpipe nitrous oxide emissions (0.010 grams/mile) and methane emissions (0.030 grams/mile).

As with the Phase 1 standards, the agencies used the concept of a vehicle's "footprint" to set differing targets for different size vehicles.43 These "size-based," or "attribute-based," standards were structurally different than the original CAFE program, which grouped domestic passenger cars, imported passenger cars, and light trucks into three broad categories.44 Generally, the larger the vehicle footprint (in square feet), the lower the corresponding vehicle fuel economy target and the higher the CO2-equivalent emissions target. This allowed auto manufacturers to produce a full range of vehicle sizes, as opposed to focusing on light-weighting and downsizing45 the entire fleet in order to meet the categorical targets.

Upon the rulemaking, the agencies expected that the technologies available for auto manufacturers to meet the MY 2017-2025 standards would include advanced gasoline engines and transmissions, vehicle weight reduction, lower tire rolling resistance, improvements in aerodynamics, diesel engines, more efficient accessories, and improvements in air conditioning systems. Some increased electrification of the fleet was also expected through the expanded use of stop/start systems, hybrid vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, and electric vehicles.

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

GHG Standard (grams per mile) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

GHG-Equivalent Fuel Economy (miles per gallon equivalent) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standard (miles per gallon) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS, from EPA and NHTSA, "2017 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards," 77 Federal Register 62624, October 15, 2012.

Notes: The values are based on projected sales of vehicles in different size classes. The standards are size-based, and the vehicle fleet encompasses large, medium, and small cars and light trucks. Thus if the sales mix is different from projections, the achieved CAFE and GHG levels would be different. For example, CAFE numbers are based on NHTSA's projection using the MY 2008 fleet as the baseline. A different projection, based on the MY 2010 fleet, leads to somewhat lower numbers (roughly 0.3—0.6 mpg lower for MYs 2017-2020 and roughly 0.7-1.0 mpg lower for MY 2021 onward).

GHG-Equivalent Fuel Economy (miles per gallon equivalent) is the value returned if all of the GHG reductions were made through fuel economy improvements. However, in practice, other strategies are used to reduce GHG emissions to the actual GHG standard (for example, improved vehicle air conditioners).

CAFE standards for MYs 2022-2025 are italicized because they are non-final (or "augural"). NHTSA has authority to set CAFE standards only in five-year increments. Thus, only rules through MY 2021 have been finalized. To set standards for MY 2022 onward, NHTSA has to issue a new rule.

|

What Does a "Standard of 54.5 mpg in MY 2025" Mean? The 54.5 number is not a requirement for every—or for any specific—vehicle or manufacturer; it is an estimate for what the agencies deemed likely to be achieved, on average, by the sales-weighted U.S. fleet of light-duty vehicles in MY 2025. There are several caveats to this number: 1. The number is not for every—or for any specific—size or compliance category of vehicle or manufacturer. Different sizes and categories of vehicles have different mpg compliance targets. The number is an estimate of what the average fuel economy achievement would be for a sales-weighted fleet of all vehicles produced by all manufacturers under a specific scenario. This number was estimated during the Phase 2 rulemaking in 2012 using the MY 2008 fleet as the baseline. Thus, if the MY 2025 sales mix and sales volumes are different from projections, the achieved CAFE and GHG levels would be different. An analysis by EPA in 2016 adjusted this number to 50.8 mpg based on updated projections.46 2. This number is based on the fuel economy values returned from EPA's City and Highway laboratory test procedures. The number does not reflect real-world performance. Real-world adjusted fuel economy values are about 20% lower, on average, than the unadjusted fuel economy values that form the starting point for CAFE and GHG standard compliance. 3. The number is based on EPA's GHG emissions estimates, not NHTSA's fuel economy estimates. Thus, it represents the GHG-equivalent fuel economy (in miles per gallon equivalent) for an emissions estimate of 163 grams of CO2-equivalent per mile. While a significant portion of GHG reductions would likely come from greater fuel economy, GHG reductions can come from other sources on the vehicle (e.g., methane and nitrous oxide reductions, air-conditioning improvements). NHTSA's 2012 projection for fuel economy achievement is 49.7 mpg. 4. This number, as an estimate, also includes some of the flexibilities, credits, and incentives available to manufacturers under the standards that can be used in lieu of fuel economy achievements. |

How Do Manufacturers Comply with the Standards?

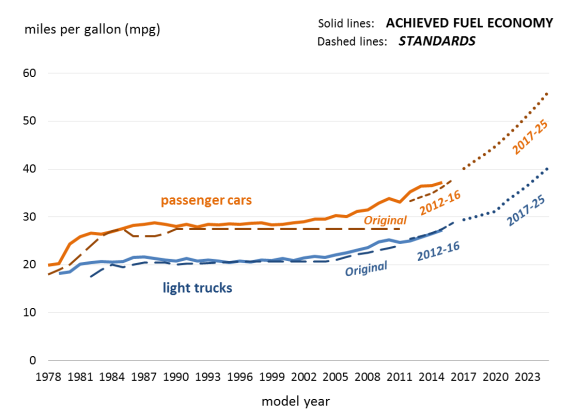

Manufacturers comply with the standards by reporting to EPA and NHTSA annually with information regarding their MY fleet production and sales numbers, their MY fleet characteristics, and the fuel economy and emissions results from the EPA-approved test cycles. This information allows the agencies to calculate each manufacturer's specific CAFE and GHG emissions standards given its fleet-wide sales numbers. The agencies compare the calculated standard against the manufacturer's fleet-wide adjusted test results to determine compliance. Accordingly, compliance is based on the vehicles sold, not the vehicles produced. Figure 1 compares CAFE standards, as promulgated for both passenger cars and light trucks over MYs 1978-2025, against the U.S. fleets' adjusted performance data as reported by NHTSA for the given MYs. Table 2 lists the most recent adjusted performance data reported by the agencies—MY 2016—for each manufacturer and its fleets.

Because of the "attribute-based" standards, compliance targets are different for each manufacturer depending on the vehicles it produces. As stated by NHTSA: "Manufacturers are not compelled to build light-duty vehicles of any particular size or type, and each manufacturer will have its own standard which reflects the vehicles it chooses to produce."47 Further, the agencies contend: "Under the National Program automobile manufacturers will be able to continue building a single light-duty national fleet that satisfies all requirements under both programs while ensuring that consumers still have a full range of vehicle choices that are available today."48

To facilitate compliance, the agencies provide manufacturers various flexibilities under the standards. A manufacturer's fleet-wide performance (as measured on EPA's test cycles) can be adjusted through the use of flex-fuel vehicles, air-conditioning efficiency improvements, and other "off-cycle" technologies (e.g., active aerodynamics, thermal controls, and idle reduction).49 Further, manufacturers can generate credits for overcompliance with the standards in a given year. They can bank, borrow, trade, and transfer these CAFE and/or GHG emission credits, both within their own fleets and among other manufacturers, to facilitate current compliance. They can also offset current deficits using future credits (either generated or acquired within three years) to determine final compliance. A CAFE credit is earned for each 0.1 mpg in excess of the fleet's standard mpg. A GHG credit is earned for each megagram (Mg, or metric ton) of CO2-equivalent saved relative to the standard as calculated for the projected lifetime of the vehicle.50 Table 3 summarizes GHG credits that are available to each manufacturer after MY 2016, reflecting all completed trades and transfers, as reported by EPA. (NHTSA's CAFE credit balances for MY 2016 have yet to be reported.)

Under the CAFE program, manufacturers can comply with the standards by paying a civil penalty. The CAFE penalty is currently $5.50 per 0.1 mpg over the standard, per vehicle.51 Historically, some manufacturers have opted to comply with the standards in this way. Beginning with MY 2019, NHTSA is scheduled to assess a civil penalty of $14 per 0.1 mpg over the standard as provided by the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act Improvements Act of 2015 within the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) and subsequent rulemaking.52

Under the CAA, manufacturers that fail to comply with the GHG emissions standards are subject to civil enforcement. The EPA Administer and the U.S. Attorney General determine the amount of the civil penalty based on numerous factors, but it could be as high as $37,500 per vehicle per violation.53 As of MY 2015, EPA has not determined any manufacturer to be out of compliance with the light-duty vehicle GHG emissions standards.

Table 2. MY 2016 Manufacturer Fuel Economy and GHG Values

(CAFE data are provisional. GHG data are final. Italicized values show performance data that do not meet the standards, but before the manufacturer's use of compliance flexibilities.)

|

Manufacturer |

Fleet |

CAFE Standard (mpg) |

CAFE Performance (mpg) |

GHG Standard (g/m) |

GHG Performance (g/m) |

|

BMW |

IPC |

36.2 |

34.0 |

235 |

249 |

|

LT |

29.9 |

28.8 |

286 |

292 |

|

|

Daimler/Mercedes |

IPC |

35.5 |

34.4 |

239 |

254 |

|

LT |

29.5 |

27.3 |

290 |

326 |

|

|

Fiat Chrysler * |

DPC |

35.6 |

31.6 |

237 |

267 |

|

IPC |

37.4 |

31.1 |

|||

|

LT |

29.0 |

26.5 |

295 |

321 |

|

|

Ford |

DPC |

36.5 |

36.0 |

234 |

243 |

|

IPC |

38.0 |

30.8 |

|||

|

LT |

27.2 |

25.7 |

315 |

339 |

|

|

GM |

DPC |

36.2 |

34.5 |

233 |

246 |

|

IPC |

39.9 |

38.7 |

|||

|

LT |

27.0 |

25.0 |

318 |

350 |

|

|

Honda |

DPC |

37.3 |

41.9 |

227 |

202 |

|

IPC |

40.3 |

45.3 |

|||

|

LT |

30.4 |

30.9 |

281 |

275 |

|

|

Hyundai |

IPC |

36.8 |

38.3 |

231 |

228 |

|

LT |

30.5 |

26.3 |

280 |

329 |

|

|

Jaguar Land Rover |

IPC |

34.3 |

27.3 |

250 |

299 |

|

LT |

29.8 |

24.9 |

288 |

330 |

|

|

Kia |

IPC |

37.1 |

36.2 |

229 |

239 |

|

LT |

29.6 |

26.7 |

288 |

321 |

|

|

Mazda |

DPC |

40.9 |

50.2 |

228 |

214 |

|

IPC |

37.2 |

41.8 |

|||

|

LT |

31.4 |

34.3 |

271 |

259 |

|

|

Mitsubishi |

IPC |

38.9 |

36.2 |

219 |

238 |

|

LT |

32.9 |

33.9 |

260 |

244 |

|

|

Nissan |

DPC |

37.2 |

42.0 |

229 |

212 |

|

IPC |

36.9 |

38.0 |

|||

|

LT |

30.2 |

30.7 |

284 |

286 |

|

|

Subaru |

IPC |

37.9 |

38.2 |

224 |

241 |

|

LT |

32.4 |

36.4 |

262 |

243 |

|

|

Tesla |

DPC |

32.1 |

320.4 |

267 |

-6 |

|

Toyota |

DPC |

36.4 |

37.2 |

228 |

214 |

|

IPC |

37.9 |

41.2 |

|||

|

LT |

29.3 |

26.7 |

292 |

328 |

|

|

Volkswagen * |

DPC |

36.2 |

38.7 |

226 |

239 |

|

IPC |

38.1 |

32.1 |

|||

|

LT |

30.6 |

27.8 |

279 |

308 |

|

|

Volvo |

IPC |

35.9 |

35.3 |

238 |

241 |

|

LT |

29.6 |

29.7 |

289 |

288 |

Source: CRS, from NHTSA, "Projected Fuel Economy Performance Report," February 14, 2017, Table 1; EPA, "GHG emissions standards for Light-Duty Vehicles: Manufacturer Performance Report for the 2016 Model Year," EPA-420-R-18-002, January 2018, Table 3-35.

Notes: CAFE values in miles per gallon (mpg); GHG values in grams per mile (g/m). CAFE compliance is divided into three fleets: domestic passenger cars (DPC), import passenger cars (IPC), and light trucks (LT); GHG compliance is divided into two fleets: passenger cars and light trucks. CAFE and GHG performance values are after fleet adjustments but before credit banking, borrowing, trading, or transferring by manufacturer. A higher CAFE performance value than CAFE standard value is in compliance; a lower GHG performance value than GHG standard value is in compliance. Values listed in italics show performance data that do not meet the standards after the 2-cycle test and adjustments, but before the manufacturer's use of compliance flexibilities.

* Fiat Chrysler and Volkswagen are under ongoing investigations and/or corrective actions. Investigations and corrective actions may yield different final data.

|

Manufacturer |

Total Credits Carried Forward to MY 2017 |

|

|

Toyota |

|

|

|

Honda |

|

|

|

Nissan |

|

|

|

Ford |

|

|

|

Hyundai |

|

|

|

GM |

|

|

|

Fiat Chrysler * |

|

|

|

Subaru |

|

|

|

Mazda |

|

|

|

Kia |

|

|

|

BMW |

|

|

|

Daimler/Mercedes |

|

|

|

Volkswagen * |

|

|

|

Mitsubishi |

|

|

|

Suzuki |

|

|

|

Karma Auto |

|

|

|

BYD Motors |

|

|

|

Tesla |

|

|

|

Volvo |

|

|

|

Jaguar Land Rover |

|

Source: CRS, from EPA, "GHG emissions standards for Light-Duty Vehicles: Manufacturer Performance Report for the 2016 Model Year," EPA-420-R-18-002, January 2018, Table 5-2.

Notes: A GHG credit is earned for each megagram (Mg, or metric ton) of CO2-equivalent saved relative to the standard as calculated for the projected lifetime of the vehicle. EPA estimates the lifetime of a passenger car to be 14 years and the lifetime of a light truck to be 16 years. Accordingly, outstanding credits for all manufacturers carried forward to MY2017 are equivalent to 262 million metric tons CO2-equivalent saved. For comparison, CO2-equivalent emissions from all on-road passenger cars and light trucks in the United States in 2016 were 1,058 million metric tons (EPA, "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 1990-2016," EPA 430-R-18-003, April 12, 2018, Table 3-12).

Some companies on the list produced no vehicles for the U.S. market in the most recent model year, but the credits generated in previous model years continue to be available. Manufacturers can offset current deficits using future credits (either generated or acquired within three years) to determine final compliance.

* Fiat Chrysler and Volkswagen are under ongoing investigations and/or corrective actions. Investigations and corrective actions may yield different final data.

What Is the Midterm Evaluation?

As part of the Phase 2 rulemaking, EPA and NHTSA made a commitment to conduct a midterm evaluation (MTE) for the latter half of the standards, MYs 2022-2025.54 The agencies deemed an MTE appropriate given the long time frame during which the standards were to apply and the uncertainty about how motor vehicle technologies would evolve. EPA, NHTSA, and California also have differing statutory obligations. That is, EPA, California, and some other states—through their authorities under the CAA, California AB 1493, and other state statutes—have finalized GHG emissions standards through MY 2025. Under the MTE, EPA and CARB were to decide whether to revise their standards. NHTSA, through its authorities under EPCA, has finalized standards only through MY 2021, and would require new rulemaking for the period MYs 2022-2025.

Through the MTE, the EPA Administrator was to determine whether EPA's standards for MYs 2022-2025 were still appropriate given the latest available data and information.55 A final determination could result in strengthening, weakening, or retaining the current standards. If EPA determined that the standards were appropriate, the agency would "announce that final decision and the basis for that decision." If EPA determined that the standards should be changed, EPA and NHTSA would be required to "initiate a rulemaking to adopt standards that are appropriate." Throughout the process, the MY 2022-2025 standards were to "remain in effect unless and until EPA changes them by rulemaking."

The Phase 2 rulemaking laid out several formal steps in the MTE process, including

- a Draft Technical Assessment Report issued jointly by EPA, NHTSA, and CARB with opportunity for public comment no later than November 15, 2017;

- a Proposed Determination on the MTE, with opportunity for public comment; and

- a Final Determination, no later than April 1, 2018.

EPA, NHTSA, and CARB jointly issued the Draft Technical Assessment Report for public comment on July 27, 2016.56 This was a technical report, not a decision document, and examined a wide range of technology, marketplace, and economic issues relevant to the MY 2022-2025 standards. It found

- auto manufacturers are innovating in a time of record sales and fuel economy levels;

- the MY 2022-2025 standards could be met largely with more efficient gasoline-powered cars and with only modest penetration of hybrids and electric vehicles; and

- the "attribute-based" standards preserve consumer choice, even as they protect the environment and reduce fuel consumption.

On November 30, 2016, the Obama Administration's EPA released a proposed determination stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards remained appropriate and that a rulemaking to change them was not warranted.57 The agency based its findings on a Technical Support Document,58 the previously released Draft Technical Assessment Report, and input from the auto industry and other stakeholders. On January 12, 2017, then-EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy finalized the determination, stating that "the standards adopted in 2012 by the EPA remain feasible, practical and appropriate."59

The final action arguably accelerated the timeline for the MTE, and EPA announced it separately from any NHTSA or CARB announcement. EPA noted its "discretion" in issuing a final determination, saying that the agency "recognizes that long-term regulatory certainty and stability are important for the automotive industry and will contribute to the continued success of the national program."60

Some auto manufacturer associations and other industry groups criticized the results of EPA's review and reportedly vowed to work with the Trump Administration to revisit EPA's determination. These groups sought actions such as easing the MY 2022-2025 requirements and/or better aligning NHTSA's and EPA's standards.

What Is the Status of CAFE and GHG Standards Under the Trump Administration?

On March 15, 2017, after President Trump took office, EPA and NHTSA announced their joint intention to reconsider the Obama Administration's final determination and reopen the midterm evaluation process. EPA announced a 45-day public comment period on August 21, 2017, and held a public hearing on September 6, 2017, receiving more than 290,000 comments.61

On April 2, 2018, EPA released a revised final determination, stating that the MY 2022-2025 standards are "not appropriate and, therefore, should be revised."62 The notice states that the January 2017 final determination is based on "outdated information, and that more recent information suggests that the current standards may be too stringent." In making the revised determination, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt cited and provided comment on several factors from the Phase 2 rulemaking that governed analysis for the midterm evaluation process. These factors include63

- the availability and effectiveness of technology, and the appropriate lead time for introduction of technology;

- the cost to the producers or purchasers of new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines;

- the feasibility and practicability of the standards;

- the impact of the standards on emissions reduction, oil conservation, energy security, and fuel savings by consumers;

- the impact of the standards on the automobile industry;

- the impact of the standards on automobile safety;

- the impact of the GHG emissions standards on the CAFE standards and a national harmonized program; and

- the impact of the standards on other relevant factors.

The revised final determination states that EPA and NHTSA will initiate a new rulemaking to consider revised standards for MY 2022-2025 vehicles.64 Until that new rulemaking is completed, the current standards remain in effect.

Can EPA Reverse Its Decision to Grant California's Waiver for MYs 2017-2025?

The CAA does not address the process or the requirements to reverse or revoke a preemption waiver. It is unclear what process EPA would follow if it were to reverse its grant of California's waiver.

In 2013, EPA granted California a preemption waiver to regulate GHG emissions from light-duty vehicles through MY 2025 pursuant to CAA Section 209(b).65 In response to the announcements from the Trump Administration regarding potential revisions to standards, California restated its "continued support for the current National Program and California's standards." On March 24, 2017, CARB passed a resolution to accept its staff's midterm evaluation of the state's Advanced Clean Car program—which includes MY 2017-2025 vehicle GHG standards in line with EPA's 2017 final determination and the 2012 rulemaking.66

EPA and NHTSA have reportedly met with CARB to discuss the MTE and post-2025 GHG standards, on which CARB officials have said they are already working. Efforts have focused on establishing a single national standard for fuel economy and GHG emissions, in order to avoid a situation in which manufacturers must deal with a patchwork of competing state regulations.67 However, because EPA has concluded in its revised final determination that the MY 2022-2025 GHG emissions standards for light-duty vehicles "are not appropriate and, therefore, should be revised,"68 the agency might decide to reconsider California's preemption waiver for the state's GHG standards for MYs 2017-2025.69 Although EPA has previously denied a request for a preemption waiver (and subsequently reversed its denial),70 the agency has never reversed its grant of a waiver. Similar to changing agency policy or reversing the denial of a waiver, EPA might determine that it has the ability to reverse its decision to grant the waiver so long as it is "aware that it is changing positions and that there are good reasons for the change in position."71

However, CAA Section 209(b), which provides the waiver requirements, does not address the process or requirements to reverse or revoke a preemption waiver. EPA has stated previously that its Section 209(b) waiver proceeding and actions are "informal adjudications."72 The Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which governs formal and informal rulemaking and judicial review of most types of final agency actions, contains no explicit procedures or requirements for informal adjudications or for reversing decisions made in previous informal adjudications.73

To reverse the grant of the waiver, EPA could decide to follow the requirements in CAA Section 209(b) that the agency followed when it reversed its 2008 denial of California's application for a waiver.74 CAA Section 209(b) directs EPA, after notice and opportunity for a public hearing, to grant preemption waivers unless certain factors warrant denial. The section provides that EPA "shall ... waive" the preemption on state emission standards "if the State determines that the State standards will be, in the aggregate, at least as protective of public health and welfare as applicable Federal standards."75 If California were to determine that its standards will be at least as protective as applicable federal standards, EPA could deny a preemption waiver request only if it finds that (1) California's determination is arbitrary and capricious; (2) California does not need state standards "to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions"; or (3) California's standards are technologically infeasible, or that California's test procedures impose requirements inconsistent with the federal test procedures under CAA Section 202(a).76

EPA would likely need to rely on one of these grounds to justify a potential reversal of its previous decision to grant the preemption waiver. As explained in a previous waiver determination, EPA must make "a reasonable evaluation of the information in the record in coming to the waiver decision."77 The APA permits judicial review of final agency actions, such as EPA's waiver determinations.78 The APA directs reviewing courts to "hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions" that are, among other things, "arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law."79 The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit cautioned that "if the [EPA] Administrator ignores evidence demonstrating that the waiver should not be granted, or if he seeks to overcome that evidence with unsupported assumptions of his own, he runs the risk of having his waiver decision set aside as arbitrary and capricious.''80

What Is Meant by "Harmonizing" or "Aligning" the Standards?

Many auto manufacturers and industry stakeholders have argued that the CAFE and GHG emission standards are intended to be a joint set of rules that would allow auto manufacturers to comply with both programs through a single unified fleet. In practice, however, differences in the test procedures, flexibilities, and credit systems used by NHTSA and EPA have created the possibility that a manufacturer's fleet may be in compliance with one agency's program but not the other's. Although the agencies have acted to integrate the standards, differences remain. Some stakeholders argue for statutory or regulatory changes to further integrate—or what they refer to as "harmonize" or "align"—the standards.

Table 4 outlines a selection of the differences between the federal programs. Many of NHTSA's requirements are statutory; and thus, any potential adjustments to NHTSA's CAFE program would likely require legislation.

Lawmakers have proposed several bills in the 114th and 115th Congresses to address some of the statutory limitations of the CAFE program vis-à-vis the GHG program. These include

- S. 1273/H.R. 4011 (115th), the "Fuel Economy Harmonization Act," would amend 49 U.S.C. Chapter 329 to extend NHTSA's credit banking period, ease the limits on credit trading and transferring between fleets, and allow for Phase 1 off-cycle credits.

- H.R. 1593 (115th), the "CAFE Standards Repeal Act of 2017," would repeal 49 U.S.C. Chapter 329.

- S.Amdt. 3251 to S. 2012 (114th) would have modified the calculation of fuel economy for gaseous fuel dual fueled automobiles under 49 U.S.C. Chapter 329.

Table 4. Selected Differences Between NHTSA's CAFE and EPA's GHG Programs

(citations to the U.S.C. and C.F.R. are provided where appropriate)

|

Item |

NHTSA CAFE Program |

EPA GHG Program |

|

Authority |

EPCA, EISA |

CAA |

|

Citations |

49 U.S.C. §§32901-32919; 49 C.F.R. Parts 523, 531, 533, and 600 |

42 U.S.C. §§7521-7554; 40 C.F.R. Parts 85, 86, and 600 |

|

Stated Purpose |

"To increase domestic energy supplies and availability; to restrain energy demand; [and] to prepare for energy emergencies" EPCA 1975 |

To prevent the "emission of any air pollutant from any class or classes of new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines, which … cause, or contribute to ... air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare" CAA 1970 |

|

Considerations |

EPCA requires that NHTSA establish separate passenger car and light truck standards (49 U.S.C. §32902(b)(1)) at "the maximum feasible average fuel economy level that it decides the manufacturers can achieve in that model year" (49 U.S.C. §32902(a)), based on the agency's consideration of four statutory factors: "technological feasibility, economic practicability, the effect of other motor vehicle standards of the Government on fuel economy, and the need of the United States to conserve energy" (49 U.S.C. §32902(f)) |

CAA requires that EPA consider issues of technical feasibility, cost, and available lead time. Standards under section CAA 202 (a) take effect only "after providing such period as the Administrator finds necessary to permit the development and application of the requisite technology, giving appropriate consideration to the cost of compliance within such period" (42 U.S.C. §7512 (a)(2)) |

|

Compliance Categories |

"Passenger car" and "light truck" as defined in 49 C.F.R. Part 523 |

"Light-duty vehicle," "light-duty truck," and "medium-duty passenger vehicle" as defined in 40 C.F.R. §86.1803-01 |

|

Control |

Fleet average fuel economy as measured by vehicle miles per gallon (49 U.S.C. §32901(11)) |

Fleet average CO2-equivalenta emissions as measured by grams per mile |

|

Duration |

5 years; MYs 2017-2021 (49 U.S.C. §32902(b)(3)(B)); and the proposal of non-final "augural" standards for MYs 2022-2025 |

MYs 2017-2025 (EPA's duration is unlimited under the CAA) |

|

Minimum Standard |

Minimum Fleet Standard: 35 mpg by MY 2020 (49 U.S.C. §32902(b)(2)(A)); Minimum Domestic Passenger Car Standard: 27.5 mpg or 92 percent of the average fuel economy of the combined domestic and import passenger car fleets in that model year, whichever is greater (49 U.S.C. §32902(b)(4)) |

None |

|

Cost of Non-compliance |

Fines can be paid to satisfy compliance. Fee of $5.50 per 0.1 mpg over the standard, per vehicle (49 U.S.C. §32912); starting 2019, $14 per 0.1 mpg over the standard (NHTSA, "Civil Penalties: Final Rule," 81 Federal Register 95489, December 28, 2016) |

Civil enforcement; unknown penalty, but could be as high as $37,500 per vehicle per violation of the CAA (42 U.S.C. §7524) |

|

Credits |

||

|

Definition of Credit |

0.1 mpg above manufacturer's required mpg standard for fleet (49 U.S.C. §32903(d)) |

1.0 megagram (or metric ton) of CO2-equivalent as estimated over the lifetime of the vehicle below the manufacturer's standard |

|

Compliance Categories |

Domestic Passenger Cars, Import Passenger Cars, and Light Trucks (49 U.S.C. §32903(g)(6)(b)) |

Passenger Cars and Light Trucks |

|

Credit Banking |

5-year banking period (49 U.S.C. §32903(a)(2)) |

5-year banking period with the exception that credits earned between MYs 2010-2016 can be carried forward through MY 2021 |

|

Credit Borrowing |

3-year carryback period (49 U.S.C. §32903(a)(1)) |

3-year carryback period |

|

Limits |

Limits on credits that can be transferred between compliance fleet categories; adjustment factors placed on traded or transferred credits to preserve "fuel savings" over the vehicle miles traveled (VMT) of the vehicle (49 U.S.C. §32903(f-g)) |

No limits on credits transferred between compliance categories; VMT calculation incorporated into definition of credit |

|

Provisions for Alternative-Fueled Vehicles |

Credits for ethanol and methanol fuels; electricity use in electric vehicles is converted to "equivalent gallons of gasoline" and only 15% of that is counted for compliance (49 U.S.C. §§32905-32906) |

Allows manufacturers to count each alternative-fueled vehicle as more than a single vehicle—multipliers range from 1.3 to 2.0 depending on the extent of alternative fuel used and the MY; emissions from battery electric vehicles assumed to be zero |

|

Exemptions |

Secretary of Transportation's decision on exemptions for manufacturers with limited production lines of fewer than 10,000 passenger automobiles in the model year 2 years before the model year for which the application is made (49 U.S.C. §32902(d)); generally, fines can be paid to satisfy compliance |

Temporary Lead-time Allowance Alternative Standards for manufacturers with limited product lines through MY 2015 |

Source: CRS, from EPA and NHTSA, "2017 and Later Model Year Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards; Final Rule," 77 Federal Register 62624, October 15, 2012; 49 U.S.C. §§32901-32919; 42 U.S.C. §§7401-7671q; 49 C.F.R. Parts 523, 531, 533, and 600; and 40 C.F.R. Parts 85, 86, and 600.

Notes: (a) Although CO2 is the primary GHG, other gases, such as methane (CH4) and fluorinated gases (e.g., air conditioner refrigerants), also act as greenhouse gases. The calculations of the weighted fuel economy and carbon-related exhaust emission values are provided for in 40 C.F.R. §600.113-12, and require input of the weighted grams/mile values for CO2, total hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO), and, where applicable methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (HCHO), ethanol (C2H5OH), acetaldehyde (C2H4O), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4). Reductions in other (i.e., non-tailpipe) GHG emissions are captured in adjustments made to the compliance standards based on the manufacturer's use of flex-fuel vehicle, air-conditioning, "off-cycle," and CH4 and N2O deficit credits.

Other differences between NHTSA's CAFE and EPA's GHG standards stem from the agencies' regulatory interpretations. These differences could potentially be addressed through new rulemaking. In June of 2016, the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and the Association of Global Automakers submitted to EPA and NHTSA a Petition for a Direct Final Rule.81 The petition asked the agencies to address some of the regulatory differences between the two programs, such as the calculations and applicability of off-cycle credits, air-conditioning efficiency credits, fuel savings adjustment factors, vehicle miles traveled (VMT) estimates, and alternative-fueled vehicle multipliers.

NHTSA partially granted the petition for rulemaking on December 21, 2016, agreeing "to address the changes requested in the petition in the course of the rulemaking proceeding, in accordance with statutory criteria."82 Under the Trump Administration, both NHTSA and EPA have reportedly engaged with stakeholders in discussions of regulatory alignment.83 Most of these discussions have reportedly focused on loosening the stringency of NHTSA's statutory and regulatory requirements so that they more closely match the flexibilities under EPA's standards. In the near term, this could serve the purpose of allowing many auto manufacturers to avoid paying compliance penalties under NHTSA's CAFE program, as they would be allowed to account for more credits in a revised system. Greater alignment, however, could also be achieved through tightening some of EPA's flexibilities so that they more closely adhere to NHTSA's requirements.

What Are Some of the Issues That Are Informing the Discussion on the Standards?

Below is a selected list of broader policy issues regarding the CAFE and GHG emission standards, their design, purpose, and potential revision. The issues are organized according to the specific factors listed in the requirements for the midterm evaluation.84

(1) The Availability and Effectiveness of Technology

The CAFE and GHG emissions standards are technology-forcing standards (i.e., they are standards that Congress authorized to set performance levels that, while not achievable immediately, are demonstrated to be achievable in the future based on information available today). Such policies date to the 1970s in environmental law and are now commonplace among health, safety, and environmental statutes. In the case of automotive controls, Congress enacted the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act (P.L. 89-272) in 1965, authorizing the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to establish motor vehicle standards to reduce tailpipe emissions. Dissatisfied with the agency's lack of progress in the years following the law's enactment, Congress amended the statute to specify not only emission limits, but also deadlines for meeting the standards, and an enforcement program to ensure compliance. These changes became a major part of the Clean Air Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-604) and its subsequent amendments. Lawmakers recognized that the technology needed to meet the standards they enacted did not yet exist, and the schedule for compliance was ambitious; however most agreed that the only way to motivate the vehicle manufacturers to develop the necessary technology was to create the incentive to force such development.

The MY 2017-2025 CAFE and GHG emissions standards are based on EPA's and NHTSA's technology analysis from the 2012 rulemaking. In a 2015 report by the National Research Council, the council "found the analysis conducted by NHTSA and EPA in their development of the [MY] 2017-2025 standards to be thorough and of high caliber on the whole" and "concurred with the Agencies' costs and effectiveness values for many technologies."85 But the council, as well as various stakeholders, expressed some concern that technologies may not be in place or achievable to attain the most stringent MY 2025 standards.

According to EPA's most recent Manufacturers' Report (MY 2016), 7 of the 13 major auto manufacturers decreased CO2-equivalent emissions and 5 increased fuel economy from MY 2015 to MY 2016. Four of the manufacturers' average adjusted CO2-equivalent emissions declined between MY 2015 and MY 2016 due, in part, to their fleets' increase in the share of light trucks. Preliminary MY 2017 adjusted CO2-equivalent emissions are projected to be 352 grams per mile and fuel economy is projected to be 25.2 mpg. These projections, if realized, would be an improvement over MY 2016. Some stakeholders have noted that many new product lines are scheduled to be introduced over the next few MYs that may further facilitate manufacturers' compliance with the standards. EPA will not have final MY 2017 data until 2019.86

According to EPA's analysis, 26% of the MY 2017 vehicles already meet or exceed the MY 2020 emissions targets, with the addition of expected air conditioning improvements and off-cycle credits. The number of vehicles meeting or exceeding the MY 2020 standards has steadily increased with each model year (e.g., fewer than 5% of MY 2012 vehicles met or exceeded the MY 2020 standards). Looking ahead, about 5% of MY 2017 vehicles could meet the MY 2025 emissions targets. These vehicles are currently comprised solely of hybrids (HEV), plug-in hybrids (PHEV), electric vehicles (EV), and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCV).87

EPA's Draft Technical Assessment Report released in July 2016 states that the technology needed to meet the MY 2025 standards would likely include "advanced gasoline vehicle technologies ... with modest levels of strong hybridization and very low levels of full electrification (plug-in vehicles)."88 Technologies considered in the report include more efficient engines and transmissions, aerodynamics, light-weighting, improved accessories, low rolling resistance tires, improved air conditioning systems, and others. Beyond the technologies the agencies considered in the 2012 final rule, several others have emerged, such as higher compression ratio, naturally aspirated gasoline engines, and an increased use of continuously variable transmissions. Further, the agencies expect other new technologies that are under active development to be in the fleet before MY 2025 (e.g., 48-volt mild hybrid systems). Stakeholders have heavily debated the level of advanced gasoline, hybrid, and/or electric penetration needed to meet the MY 2025 standards.

Table 5 shows fleet-wide penetration rates for a subset of the technologies that could be utilized to comply with the MY 2025 standards, as assessed by each agency's separate evaluation in the Draft Technical Assessment Report.

|

Technology |

EPA |

NHTSA |

|

Turbocharged and downsized gasoline engines |

33% |

54% |

|

Higher compression ratio, naturally aspirated gasoline engines |

44% |

<1% |

|

8-speed and other advanced transmissions |

90% |

70% |

|

Mass reduction |

7% |

6% |

|

Stop-start |

20% |

38% |

|

Mild Hybrid |

18% |

14% |

|

Full Hybrid |

<3% |

14% |

|

Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle |

<2% |

<1% |

|

Electric vehicle |

<3% |

<2% |

Source: CRS, from EPA, NHTSA, and CARB, "Draft Technical Assessment Report: Midterm Evaluation of Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards and Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards for Model Years 2022-2025," EPA-420-D-16-900, July 2016, Table ES-3.

Notes: Percentages shown are absolute rather than incremental. These values reflect both EPA and NHTSA's primary analyses; both agencies present additional sensitivity analyses in the Draft TAR at Chapter 12 (EPA) and Chapter 13 (NHTSA).

The 2018 revised final determination, however, reports that the Draft Technical Assessment Report's analysis "was optimistic in its assumptions and projections with respect to the availability and effectiveness of technology and the feasibility and practicability of the standards."89 It calls into question the prior assumptions regarding electrification and notes an overreliance on future and/or proprietary technologies.

(2) The Cost on the Producers or Purchasers of New Motor Vehicles

The addition of fuel efficiency technologies in the U.S. fleet of passenger cars and light trucks incurs an initial set of costs on manufacturers and, by extension, consumers. However, these initial, incremental costs may be recouped by consumers through fuel savings over the lifetime of the vehicles. Both EPCA and CAA contain provisions that require the agencies to consider costs when promulgating standards.90 The agencies are also subject to executive orders—such as E.O. 12866, "Regulatory Planning and Review"—that require the estimation of costs and benefits any time they develop "economically significant" regulations.91 E.O. 12866 further states that, "Each agency shall assess both the costs and the benefits of the intended regulation and, recognizing that some costs and benefits are difficult to quantify, propose or adopt a regulation only upon a reasoned determination that the benefits of the intended regulation justify its costs."

Based on the updated assessments provided in the Draft Technical Assessment Report, the projections for the average, initial costs of meeting the MY 2025 standards (incremental to the costs already incurred to meet the MY2021 standards) are approximately $1,100 per vehicle. Total industry-wide costs of meeting the MY 2022-2025 GHG standards are estimated at approximately $36 billion (at a 3% discount rate).

Benefits of the CAFE and GHG emission standards as measured by the agencies include impacts such as climate-related economic benefits from reducing emissions of CO2, reductions in energy security externalities caused by U.S. petroleum consumption and imports, the value of certain particulate matter-related health benefits (including premature mortality), the value of additional driving attributed to the VMT rebound effect, and the value of reduced refueling time needed to fill up a more fuel-efficient vehicle.

According to the 2016 Draft Technical Assessment Report, EPA estimates that GHG emissions would be reduced by about 540 million metric tons (MMT) and oil consumption would be reduced by 1.2 billion barrels over the lifetimes of MY 2022-2025 vehicles. Consumer pretax fuel savings are estimated to be $89 billion over the lifetime of vehicles meeting the MY 2022-2025 standards. Net benefits (inclusive of fuel savings) are estimated at $92 billion. EPA's analysis indicates that, compared to the MY 2021 standards, the MY 2025 standards will result in a net lifetime consumer savings of approximately $1,500 per vehicle with a payback period of about 5 years.92

The 2018 revised determination, however, states that the Draft Technical Assessment Report may underestimate costs and overstate benefits.93 Referencing analyses provided by the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and Global Automakers, it identifies direct technology costs, indirect cost multipliers, and cost learning curves as areas that need further assessment. It also contends that the Draft Technical Assessment Report does not give appropriate consideration to the effect of the standards on low-income consumers.94

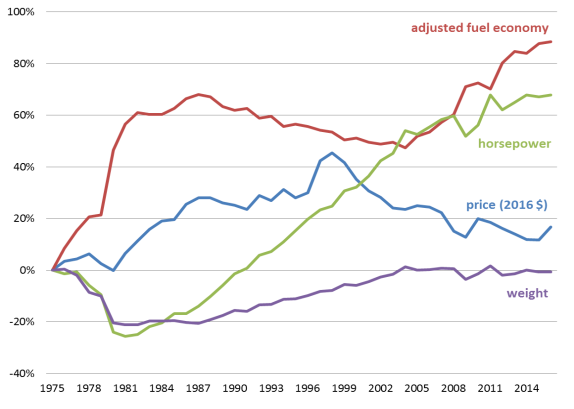

(3) The Feasibility and Practicability of the Standards

In both the 2017 and 2018 final determinations, EPA interpreted an analysis of the feasibility and practicability of the standards to include an analysis of consumer choice. Many factors drive consumer buying decisions, including vehicle costs, the price of gas, and business and family needs. The CAFE and GHG emissions standards are designed with the intention that consumers can continue to buy the differing types of vehicles they need, from compact cars, to SUVs, to larger trucks suitable for towing and carrying heavy loads. Under the "attribute-based" standards, owners of every type of new vehicle are potentially afforded gasoline savings and improved fuel economy with a reduced environmental impact. Notwithstanding, the agencies continue to research consumer issues, including an assessment of vehicle affordability, a study of willingness-to-pay for various vehicle attributes, and the content analysis of auto reviews.95 During Phase 1 of the standards, vehicle sales were close to record levels; fuel efficiency, vehicle footprint, and horsepower had increased slightly; and the weight and the inflation-adjusted price of a new vehicle stayed relatively constant (see Figure 2 for the changes in some of these attributes since the passage of EPCA in 1975). Leading up to the Draft Technical Assessment Report, the agencies did not find evidence that the standards have posed significant obstacles to consumer acceptance.96

However, economic conditions change. The market has seen a sustained drop in fuel prices as a result of increased oil supply and/or reduced global demand since the origin of CAFE and GHG emission standards. Under these conditions, manufacturers are more challenged to design and sell advanced-technology, fuel-efficient vehicles at costs above the value of fuel savings captured by the new vehicle buyer. Research has shown a relationship between gasoline prices and the demand for fuel efficient vehicles.97 Accordingly, lower gasoline prices tend to incentivize consumers to purchase new vehicles with lower fuel economy. Under these conditions, consumers focus less on fuel efficiency and more on increased horsepower, size, safety, comfort, and other features. Additionally, consumers are less likely to consider alternative-fueled vehicles, such as hybrid and electric vehicles. Thus, while manufacturers may be able to engineer vehicles that meet the more stringent CAFE and GHG emission standards, the choice of consumers to focus less on fuel efficiency has presented challenges to some manufacturers' sales-weighted fleet-wide conformity.

Further, as the standards become more stringent, uncertainties may arise as to which technologies will be necessary to achieve them. While the agencies have projected that the standards could be met primarily with gasoline vehicles, alternative-fueled vehicles may gain greater penetration in the years ahead. For gasoline vehicles, consumer acceptance would likely depend on the costs, effectiveness, and potential tradeoffs or synergies of those technologies with other vehicle attributes. For alternative-fueled vehicles, the higher standards could raise the possibility of new and additional challenges to consumer acceptance (e.g., availability, incentives, infrastructure, and the complexities of understanding cost, consumption, range, and recharging patterns).

Finally, the 2018 revised final determination argues that increased prices for new motor vehicles due to advanced fuel-efficient technologies may have the unintended consequence of taking some consumers out of the market for new motor vehicles. The Administration contends that higher costs could delay fleet turnover, slow new vehicle sales, and keep less efficient vehicles on U.S. roads. In this case, fewer benefits in fuel economy and GHG emissions would be realized, as many consumers would retain their current vehicles or purchase used ones.

(4) The Impact of the Standards on Reduction of Emissions, Oil Conservation, Energy Security, and Fuel Savings by Consumers

In the final Phase 2 rulemaking, EPA and NHTSA estimated that the standards would save approximately 4 billion barrels of oil and reduce GHG emissions by the equivalent of approximately 2 billion metric tons over the lifetimes of those light-duty vehicles produced in MYs 2017-2025. Based on the updated assessments provided in the Draft Technical Assessment Report, EPA estimates that over the lifetime of vehicles meeting the second half of the standards (MYs 2022-2025), GHG emissions would be reduced by about 540 MMT and oil consumption would be reduced by 1.2 billion barrels. Consumer pretax fuel savings are estimated to be $89 billion over the lifetime of vehicles meeting the MY 2022-2025 standards.

GHG Emissions and the Transportation Sector

The statement of purpose in the CAA includes protecting against "air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare."98 EPA's 2009 endangerment finding determined that "the combined emissions of ... greenhouse gases from new motor vehicles and new motor vehicle engines contribute to the greenhouse gas air pollution that endangers public health and welfare under CAA section 202(a)."99 This finding formed the basis of EPA's GHG emission regulations on new motor vehicles.

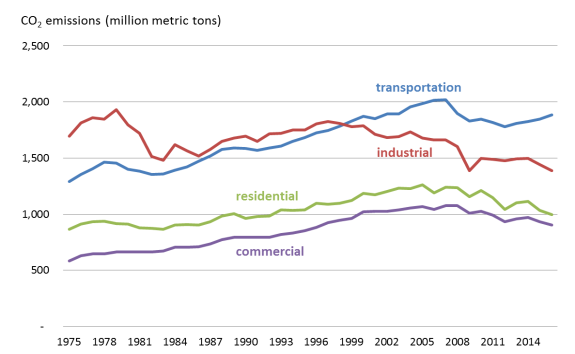

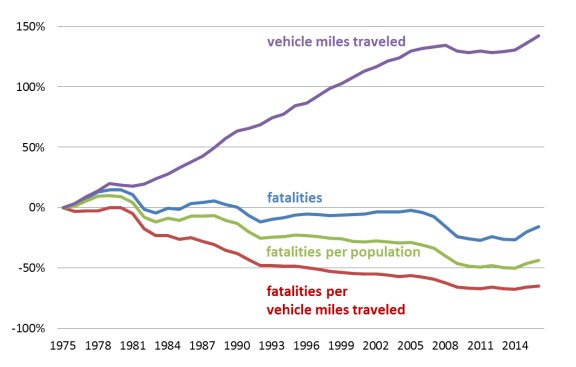

Various trends from the mid-1990s through today have informed the discussion on GHG emissions in the transportation sector. Transportation is one of the largest contributors to man-made GHG emissions in the United States. According to EPA's "Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks," transportation represented 27% of total U.S. GHG emissions in 2015 (up from 24% in 1990), and light-duty vehicles contributed 60% of the sector's total emissions (thus, passenger cars and light trucks represented one-sixth of all U.S. GHG emissions).100 In 2015, emissions from the transportation sector surpassed those from the electric-power sector for the first time. This transition was as much the product of the electric-power sector's increased efficiency (due to the substitution of renewables and natural gas for coal-fired power generation) as it was the transportation sector's continued growth. Nevertheless, transportation remains the only broad category of the economy in which emissions have risen in recent years (see Figure 3).101

Energy Conservation and the Transportation Sector

The statement of purpose in EPCA includes requirements "to conserve energy supplies through energy conservation programs, and, where necessary, the regulation of certain energy uses ... and to provide for improved energy efficiency of motor vehicles."102 Further, in regard to NHTSA's specific requirement to set "the maximum feasible average fuel economy level that it decides the manufacturers can achieve in that model year," EPCA requires NHTSA to consider four factors: "technological feasibility, economic practicability, the effect of other motor vehicle standards of the Government on fuel economy, and the need of the United States to conserve energy."103 The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has stated that "EPCA clearly requires the agency to consider these four factors, but it gives NHTSA discretion to decide how to balance the statutory factors—as long as NHTSA's balancing does not undermine the fundamental purpose of the EPCA: energy conservation."104

Various trends from the mid-1970s through today have informed the discussion on energy conservation in the transportation sector. As some of these trends highlight an increase in available petroleum products for the United States, various stakeholders have argued that more stringent fuel economy standards for vehicles are unnecessary. However, other trends show a movement away from energy conservation, and, arguably, a greater need to ensure fuel economy benefits in order to conserve oil.

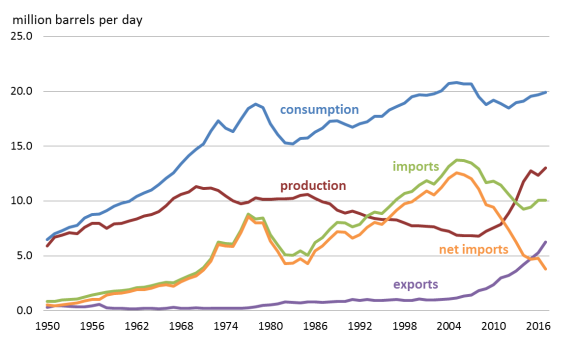

For example, in 1975, U.S. net imports (imports minus exports) of petroleum from foreign countries were equal to about 36% of U.S. petroleum consumption, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).105 However, as of late, U.S. production of petroleum (including crude oil and natural gas liquids) has reached a level not seen in decades; and net imports of petroleum have dropped to 24% of consumption. Nonetheless, net imports averaged 4.8 million barrels per day in 2016, and petroleum consumption has increased steadily since 2011 (see Figure 4).

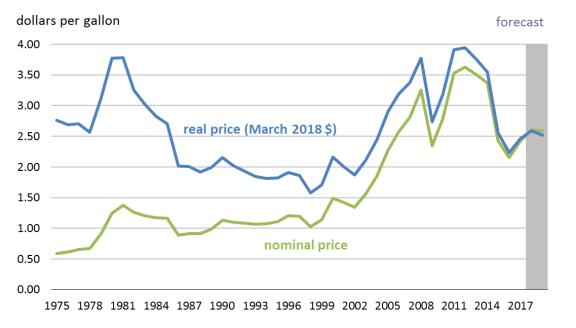

The price of gasoline at the pump has likewise seen fluctuations since 1975 (see Figure 5). The second half of the 1970s saw a doubling in the nominal price of gasoline. As recently as 2010-2014, the inflation-adjusted price of a gallon of regular grade gasoline had hovered over $3.50 per gallon (in constant 2018$). Lately, however, that price has returned to levels comparable to 1975 (approximately $2.50 per gallon in constant 2018$). EIA projects that gasoline will remain below $3.00 a gallon through 2019. Gasoline prices were $2.92 on May 21, 2018.106

|

Figure 5. Annual Motor Gasoline Regular Grade Retail Price (1975-2018) |

|

|

Source: CRS, from EIA, "Short-Term Energy Outlook," March 6, 2018. |

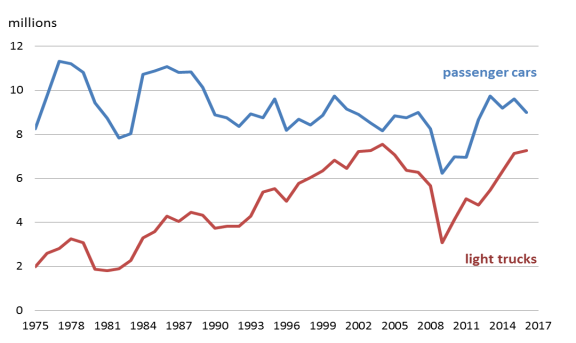

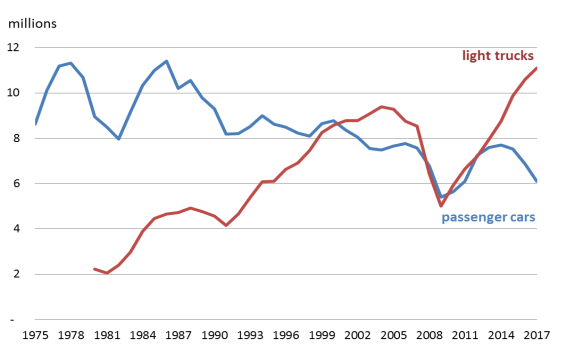

Recent trends in the vehicle sector also affect the discussion on energy conservation. For nearly 25 years, the U.S. vehicle fleet has seen a decline in passenger car sales in favor of larger pickup trucks, SUVs, and crossover vehicles, a trend that has accelerated since the end of the 2008-2009 recession (see Figure 6). In 2000, 49% of U.S. light-duty vehicles sales were pickups and SUVs; by 2017 the share of that segment rose to 65%. The changing U.S. fleet mix is driven by several factors; newer SUVs and crossovers

- have more fuel-efficient engines that make them more attractive to car buyers than previous models with lower gas mileage; and

- offer more space and greater versatility of use than a standard passenger car.

Further, some automakers reportedly have a low profit margin on their passenger cars, prompting the manufacturers to shift away from these vehicles.107

For compliance purposes, the CAFE and GHG emissions standards define vehicle categories slightly differently than industry. Nevertheless, the trend toward light trucks over passenger cars is similar, although not as pronounced (see Figure 7).

Finally, another measure relevant to motor vehicle analysis is the total vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by on-road motor vehicles in the United States. Between 1975 and 2017, VMT increased nearly 150%, from approximately 1.3 trillion miles to 3.2 trillion miles.108

|

Figure 6. U.S. Vehicles Sold, as Defined by Industry Categories (1975-2017) |

|

|

Source: CRS, from Ward's Auto Database. |

(5) The Impact of the Standards on the Automobile Industry

In both the 2017 and 2018 final determinations, EPA interpreted an analysis of the impacts of the standards on the automotive industry to include an analysis of industry costs, vehicle sales, and automotive sector employment. While the 2017 final determination finds that the standards would impose a reasonable per vehicle cost to manufacturers, it returns no evidence in support of adverse impacts on vehicle sales or on other vehicle attributes, or on employment in the automotive industry sector.109 The 2018 final determination, however, finds that the standards potentially impose unreasonable per-vehicle costs resulting in decreased sales and potentially significant impacts to both automakers and auto dealers. Further, it states recognition of significant unresolved concerns regarding the impact of the current standards on U.S. auto industry employment.110

Notwithstanding, both determinations comment on the potential for the standards to lead to macroeconomic and employment benefits through their effects on innovation, investment in key technologies, and a competitive advantage for U.S. companies in the global marketplace.

(6) The Impacts of the Standards on Automobile Safety

The primary goals of the CAFE and GHG emission standards are to reduce fuel consumption and GHG emissions from the on-road light-duty vehicle fleet. But in addition to these intended effects, the agencies also consider the potential of the standards to affect vehicle safety. As a safety agency, NHTSA has long considered the potential for adverse safety consequences when establishing CAFE standards. Similarly, under the CAA, EPA considers factors related to public health and welfare, including safety, in regulating emissions of air pollutants from mobile sources.

Research has shown that safety trade-offs associated with fuel economy increases have occurred in the past, particularly before NHTSA switched its CAFE program to an "attribute-based" standard. In a 2002 report, the National Research Council concluded that "the preponderance of evidence indicates that this downsizing of the vehicle fleet [in response to original CAFE program] resulted in a hidden safety cost, namely, travel safety would have improved even more had vehicles not been downsized."111 These past safety trade-offs occurred, in part, because manufacturers chose at the time to build smaller and lighter vehicles rather than adding more expensive fuel-saving technologies. The regulatory decision to move to an "attribute-based" standard in NHTSA's MY 2008-2011 light truck proposal—as well as in Phase 1 of the rulemaking—was due, in part, to these concerns over safety.

Debate over the hidden safety cost of the CAFE and GHG emission standards has continued. Vehicles have gotten safer—vehicle fatalities per mile traveled are significantly lower than they were in the 1970s. However, some argue that fatalities would be even lower in the absence of the standards. Total fatalities and fatalities per mile traveled have declined by 15% and 65%, respectively, between 1975 and 2016 (see Figure 8). However, the fatality rate has been trending upward since 2013. Additionally, the 2016 fatality count is the highest since 2007 and the fatality rate is the highest since 2008.112 These trends may be due to many factors, including less use of restraints, alcohol impairment, speed, and distraction (e.g., cell phones and texting), as well as the downsizing and light-weighting of vehicles. The fatality rates also include the increased count of pedestrian fatalities. Nevertheless, vehicle design remains a concern, and the agencies continue to investigate the amount of mass reduction that is affordable and feasible while maintaining overall fleet safety and functionality, such as durability, drivability, noise, handling, and acceleration performance.

Safety may be evaluated with other metrics, such as the health and welfare impacts of reduced air pollution. In addition to reducing the emissions of GHGs, the Phase 2 standards influence ''non-GHG'' pollutants, that is, ''criteria'' air pollutants, their precursors, and air toxics, which may lead to the reduction in the respiratory health effects of air pollution (e.g., the exacerbation of asthma symptoms, diminished lung function, adverse birth outcomes, and incidences of cancer).113

(7) The Impact of the Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards on the CAFE Standards and a National Harmonized Program

The CAFE and GHG emission standards are a set of performance standards, based on an evaluation of future technological and economic feasibility. While fuel economy, rated in miles per gallon achieved, has risen from 13 mpg to 25 mpg under the CAFE standards (i.e., since 1978), the program is only one of many possible policy options that could conserve fuel and reduce GHG emissions. Some have argued that market-based approaches such as a gasoline tax, a GHG emissions fee on motor vehicles, or an economy-wide policy to constrain GHG emissions, could be more efficient and cost-effective. Similarly, in lieu of or in addition to a federally mandated performance standard, some state and local governments have proposed or promulgated policies to serve similar ends. These include—but are not limited to—mandates or incentives for the sale or use of alternative-fueled vehicles, access limits for petroleum-fueled vehicles in cities or on state highways, and congestion charges and other efforts to limit vehicle use. Further, other transportation-related policies are being fashioned that will have significant—albeit uncertain—impacts on fuel economy and GHG emissions. These include connected and autonomous vehicle technologies, ride-sharing services, and investments in mass transit and bicycle infrastructure, among others. As more city, state, and national governments investigate options to conserve fuel and reduce emissions, these and other policies are likely to become more common, potentially impacting the design and purpose of vehicle performance standards.

The CAFE and GHG emission standards are a federal program, and both EPCA and CAA generally preempt state and local governments from regulating fuel economy and air pollution emissions from mobile sources. Auto manufacturers have been supportive of the regulatory certainty provided by a single national standard with a long lead time, partly because of concerns that states could implement divergent standards in the absence of a uniform federal standard. This regulatory certainty was a principal component of the agreement brokered between the auto manufacturers, EPA, NHTSA, and the State of California at the inception of the National Program. Revising the federal standards could reintroduce divergence if California and the Section 177 states choose to maintain higher standards. This possibility has generated discussion that spans from revoking California's CAA waiver to keeping the standards in place but providing greater compliance flexibilities.

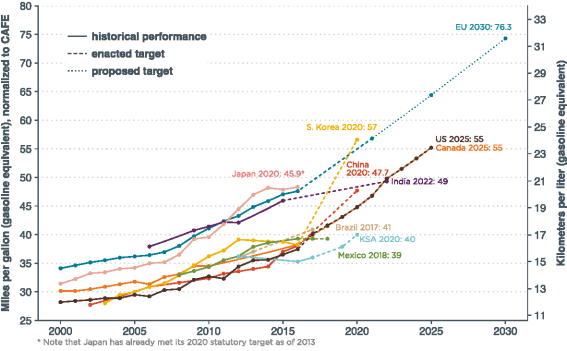

Finally, discussion of regulatory alignment also extends to the global marketplace. Auto manufacturers produce and sell vehicles in all major international markets and they increasingly see the benefit of aligning vehicle safety and emission standards in North America, Europe, and Asia. As the United States reconsiders its vehicle fuel economy and GHG emissions standards through MY 2025, the major auto manufacturers remain attuned to the standards being adopted by other countries. For example, Canada's vehicle standards closely align with the current CAFE and GHG emission standards; Canada has not announced that they are under review. China, India, Japan, South Korea, and many European nations have announced GHG emissions standards and alternative-fueled vehicle mandates that would be more stringent than the existing U.S. program (see Figure 9). As more foreign governments move to increase their standards, auto manufacturer may potentially pursue these developments in their product planning to stay competitive globally.114

|

Figure 9. Selection of International Vehicle Standards Historical fleet CO2 emissions performance and current standards for passenger cars |

|

|

Source: The figure is provided courtesy of Zifei Yang and Anup Bandivadekar, "2017 Global Update: Light-Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas and Fuel Economy Standards," International Council on Clean Transportation, 2017, figure 4, page 11. As per ICCT's terms of use, all materials are available under the Share Alike license of Creative Commons, https://creativecommons.org. Notes: The ICCT analysis converts all international fuel economy and GHG emissions standards to mpg targets normalized to U.S. CAFE test cycles. |