The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees the approval and regulation of drugs entering the U.S. market. The agency, part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is led by the Commissioner of Food and Drugs,1 who executes the agency's responsibilities on behalf of the HHS Secretary. Two regulatory frameworks support the FDA's review of prescription drugs. First, FDA reviews the safety and effectiveness of new drugs that manufacturers2 wish to market in the United States; this process is called premarket approval or preapproval review. Second, once a drug has passed that threshold and is FDA-approved, FDA acts through its postmarket or postapproval regulatory procedures.

This report is a primer on drug approval and regulation: it describes (1) how drugs are approved and come to market, including FDA's role in that process and (2) FDA and industry roles once drugs are on the pharmacy shelves.

Legislative History of Drug Regulation

The regulation of drugs by the federal government began with the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which prohibited the interstate commerce of adulterated and misbranded drugs.3 The law did not require drug manufacturers to demonstrate safety or effectiveness prior to marketing.

Over the next half-century, Congress and the President enacted two major pieces of legislation expanding FDA's authority. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA)4 was enacted in 1938, requiring that drugs be proven safe before manufacturers may sell them in interstate commerce. Then, in 1962, in the wake of deaths and birth defects from the tranquilizer thalidomide marketed in Europe, the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments to the FFDCA was enacted,5 increasing safety provisions and requiring that manufacturers show drugs to be effective as well.6

The FFDCA has been amended many times, leading to FDA's current mission of assuring Americans that the medicines they use do no harm and actually work—that they are, in other words, safe and effective. In recent decades Congress and the President have enacted additional laws to boost pharmaceutical research and development and to speed the approval of new medicines. (See Table 1 for examples.) The history of FDA law, regulation, and practice reflects the tension between making drugs available to the public and ensuring that those drugs be safe and effective. Advocates of industry, public health, consumers, and patients with specific diseases urge FDA (and Congress) to act—sometimes to speed up and sometimes to slow down the approval process. As science evolves and public values change, finding an appropriate balance between access and safety and effectiveness is an ongoing challenge.

Since the 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), the budget for FDA's human drugs program has had two funding streams: budget authority (annual discretionary appropriations from the General Fund of the Treasury) and user fees. The user fee supplementation of the program's budget initially went to a narrowly defined set of activities to eliminate the backlog of new drug applications pending FDA review and to maintain an increased staff effort on incoming applications. With each five-year reauthorization, Congress and the President have expanded the range of activities the fees may cover.7 The 2012 reauthorization added similar fee collection authority for the review of generic drug applications.8

While not the focus of this report, FDA also regulates products other than drugs—for example, biological products,9 medical devices, dietary supplements, foods, cosmetics, animal drugs, and tobacco products.10 Sometimes the agency addresses issues that straddle two or more product types that the law treats differently.

|

How FDA Approves New Drugs

To market a prescription drug in the United States, a manufacturer needs FDA approval.11 To get that approval, the manufacturer must demonstrate the drug's safety and effectiveness according to criteria specified in law and agency regulations, ensure that its manufacturing plant passes FDA inspection, and obtain FDA approval for the drug's labeling—a term that covers all written material about the drug, including, for example, packaging, prescribing information for physicians, and patient brochures.

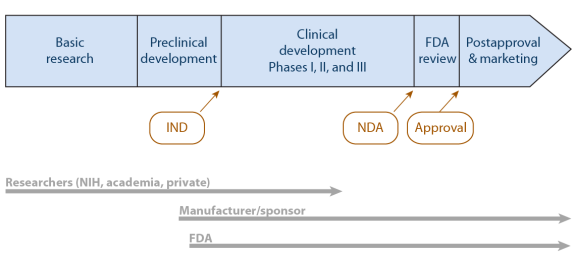

The drug development process begins before the law requires FDA involvement. Figure 1 illustrates a product's timeline both before and during FDA involvement.

The research and development process for a finished drug usually begins in the laboratory—often with basic research conducted or funded by the federal government.12 When basic research yields an idea that someone identifies as a possible drug component, government or private research groups focus attention on a prototype design. At some point, private industry (either a large, established company or a newer, smaller, start-up company) continues to develop the idea, eventually testing the drug in animals. When the drug is ready for testing in humans, the FDA must get involved.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Note: FDA = Food and Drug Administration. IND = investigational new drug application. NDA = new drug application. NIH = National Institutes of Health. |

The Standard Process of Drug Approval

This section outlines key activities leading to FDA's approval of a new drug for marketing in the United States. The law also provides for an abbreviated process for a generic drug—one chemically and therapeutically identical to an already approved drug.13

Investigational New Drug (IND) Application

Except under very limited circumstances, FDA requires data from clinical trials—formally designed, conducted, and analyzed studies of human subjects—to provide evidence of a drug's safety and effectiveness. Before testing in humans—called clinical testing—the drug's sponsor (usually its manufacturer) must file an investigational new drug (IND) application with FDA.14 The IND application includes information about the proposed clinical study design, completed animal test data, and the lead investigator's qualifications. It must also include the written approval of an Institutional Review Board,15 which has determined that the study participants will be made aware of the drug's investigative status and that any risk of harm will be necessary, explained, and minimized. The application must include an "Indication for Use" section that describes what the drug does and the clinical condition and population for which the manufacturer intends its use. Trial subjects should be representative of that population. The FDA has 30 days to review an IND application. Unless FDA objects, a manufacturer may then begin clinical testing.

Clinical Trials

With IND status, researchers test in a small number of human volunteers the safety they had demonstrated in animals. These trials, called Phase I clinical trials, attempt, in FDA's words, "to determine dosing, document how a drug is metabolized and excreted, and identify acute side effects." If the sponsor considers the product still worthy of investment, it continues with Phase II and Phase III clinical trials. Those trials gather evidence of the drug's efficacy and effectiveness in larger groups of individuals with the particular characteristic, condition, or disease of interest, while continuing to monitor safety.16

|

Safety, Efficacy, and Effectiveness Safety is often measured by toxicity testing to determine the highest tolerable dose or the optimal dose of a drug needed to achieve the desired benefit. Studies that look at safety also seek to identify any potential adverse effects that may result from exposure to the drug. Efficacy refers to whether a drug demonstrates a health benefit over a placebo or other intervention when tested in an ideal situation, such as a tightly controlled clinical trial. Effectiveness describes how the drug works in a real-world situation. Effectiveness is often lower than efficacy because of, for example, interactions with other medications or health conditions of the patient, or a sufficient dose or duration of use was not prescribed by the physician or followed by the patient.17 |

New Drug Application (NDA)

Once a manufacturer completes clinical trials, it submits a new drug application (NDA) to FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). In addition to the clinical trial results, the NDA contains information about the manufacturing process and facilities, including quality control and assurance procedures. Other mandatory information: a product description (chemical formula, specifications, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics)18; the indication (specifying one or more diseases or conditions for which the drug would be used and the population who would use it); labeling; and a proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), if appropriate.19

There are generally two types of NDAs that a manufacturer may submit, named for their locations in the FFDCA

- A 505(b)(1) NDA is an application that contains full reports of investigations of safety and effectiveness conducted by or for the applicant or for which the applicant has a right of reference or use.

- A 505(b)(2) NDA is an application that contains full reports of investigations of safety and effectiveness, where at least some of the information required for approval comes from studies not conducted by or for the applicant and for which the applicant has not obtained a right of reference or use (e.g., published literature, FDA's finding of safety and/or effectiveness for a listed drug).20

During the NDA review, CDER officials evaluate the drug's safety and effectiveness data, analyze samples, inspect the facilities where the finished product will be made, and check the proposed labeling for accuracy.

FDA Review

FDA considers three overall questions in its review of an NDA21

- Whether the drug is safe and effective in its proposed use, and whether the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks.

- Whether the drug's proposed labeling (package insert) is appropriate, and what it should contain.

- Whether the methods used to manufacture the drug and the controls used to maintain the drug's quality are adequate to preserve the drug's identity, strength, quality, and purity.

FDA scientific and regulatory personnel consider the NDA and prepare written assessments in several categories, including Medical, Chemistry, Pharmacology, Statistical, Clinical, Pharmacology, Biopharmaceutics, Risk Assessment and Risk Mitigation, Proprietary Name, and Label and Labeling.22

The FFDCA requires "substantial evidence" of drug safety and effectiveness.23 FDA has interpreted this term to mean that the manufacturer must provide at least two adequate and well-controlled Phase III clinical studies, each providing convincing evidence of effectiveness.24 The agency, however, exercises flexibility in what it requires as evidence.25 As its regulations describe in detail, FDA can assess safety and effectiveness in a variety of ways, relying on combinations of studies by the manufacturer and reports of other studies in the medical literature.26 For some NDAs, FDA convenes advisory panels of outside experts to review the clinical data.27 While not bound by their recommendations regarding approval, FDA usually follows advisory panel recommendations.

FDA approves an NDA based on its review of the clinical and nonclinical research evidence of safety and effectiveness, manufacturing controls and facility inspection, and labeling. An approval may include specific conditions, such as required postapproval studies (or postapproval clinical trials, sometimes referred to as Phase IV clinical trials) that the sponsor must conduct after marketing begins. An approval may also include restrictions on distribution, required labeling disclosures, or other elements of REMS, which are described below in the section titled "How FDA Regulates Approved Drugs."

The statute requires FDA to approve an NDA within 180 days after the filing of an application, or an additional period agreed upon by FDA and the applicant.28 In 1992, pursuant to PDUFA, FDA agreed to specific goals and created a two-tiered system of review times: Standard Review and Priority Review. Compared with the amount of time standard review generally takes (approximately 10 months), a Priority Review designation means FDA's goal is to take action on an application within 6 months.29 If FDA finds deficiencies, such as missing information, the clock stops until the manufacturer submits the additional information. If the manufacturer cannot respond to FDA's request (e.g., if it has not done a required study, making it impossible to evaluate safety or effectiveness), the manufacturer may voluntarily withdraw the application. If and when the manufacturer can provide the information, the clock resumes and FDA continues the review.

When FDA makes a final determination to approve an NDA, the agency sends the applicant an approval letter or a tentative approval letter if the NDA meets requirements for approval but cannot be approved due to a patent or exclusivity period for the listed drug.30 If FDA determines that an NDA does not meet the requirements for approval, the agency sends a "complete response letter" describing the specific deficiencies the agency identified and recommending ways to make the application viable.31 An unsuccessful applicant may request a hearing. Regulations identify the reasons for which FDA can reject an NDA, which include problems with clinical evidence of safety and effectiveness for its proposed use, manufacturing facilities and controls, labeling, access to facilities or testing samples, human subject protections, and patent information.32

Supplemental NDA. In order to make a change to an approved NDA—for example, to change the labeling, manufacturing process, or dosing, or to add a new indication (i.e., new use)—the manufacturer must submit a supplement (also referred to as a supplemental NDA). Agency regulations describe the required contents of those applications. Regarding clinical data, the applicant must submit descriptions and analysis of controlled and uncontrolled clinical studies, as well as "a description and analysis of any other data or information relevant to an evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of the drug product obtained or otherwise received by the applicant from any source, foreign or domestic, including information derived from clinical investigations, including controlled and uncontrolled studies of uses of the drug other than those proposed in the application, commercial marketing experience, reports in the scientific literature, and unpublished scientific papers."33 The 21st Century Cures Act amended these requirements to allow reliance upon qualified data summaries to support approval of a supplemental application for a qualified use of a drug. Data summaries may be used only if existing safety data are available and acceptable to FDA, and all data used to develop the qualified data summaries are submitted as part of the supplemental application.34 The 21st Century Cures Act also required the establishment of a program at FDA to evaluate the potential use of real world evidence (RWE) to support a new indication for an approved drug.35 The law defines RWE to mean "data regarding the usage, or the potential benefits or risks, of a drug derived from sources other than randomized clinical trials."36

Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA)

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 ("Hatch-Waxman Act," P.L. 98-417) established an abbreviated approval pathway for generic drugs, allowing a manufacturer to submit to FDA an abbreviated NDA (ANDA), rather than a full NDA, demonstrating that the generic product is the same as the brand drug (i.e., the reference listed drug [RLD]).37 Rather than replicate and submit data from animal, clinical, and bioavailability studies, the generic drug applicant relies on FDA's previous findings of safety and effectiveness of the approved brand drug. To obtain premarket approval of the generic, the sponsor submits an ANDA demonstrating that the generic product is pharmaceutically equivalent (e.g., has the same active ingredient[s], strength, dosage form, route of administration) and bioequivalent38 to the brand-name product. It also must meet other requirements (e.g., reviews of chemistry, manufacturing, controls, labeling, and testing). The generic and brand drugs may differ in certain characteristics (e.g., shape, excipients, packaging).39

Special Mechanisms to Expedite the Development and Review Process

Not all reviews and applications follow the standard procedures. For drugs that address unmet needs or serious conditions, have potential to offer better outcomes or fewer side effects, or meet other criteria associated with improved public health, FDA uses several formal mechanisms to expedite the development or review processes40

- Fast track and breakthrough product designations affect the administrative processes for the development of a drug and review of an application, for example, by providing for more frequent drug development-related meetings and interactions between the sponsor and FDA. Such designation does not alter the types of evidence required to demonstrate safety and effectiveness.

- Accelerated approval and animal efficacy approval change what is needed in an application. For accelerated approval, rather than requiring evidence of effectiveness on the final clinical endpoint, approval may be based on effectiveness on a surrogate or intermediate clinical outcome.41 Under the Animal Rule, when human efficacy trials are not ethical or feasible, approval may be based on adequate and well-controlled animal efficacy studies.42

- Priority review designation affects the timing of the review, not the process (neither content nor timing) leading to submission of an application.

Table 2 compares these mechanisms across several development and review characteristics.

In addition to the five mechanisms described above, various laws have provided FDA with other tools aimed at bringing products to the public. Through statutory authorities and regulatory actions, FDA provides incentives to those who would develop certain categories of drugs. The main set of incentives is the granting of market exclusivity, while a newer incentive is providing priority review vouchers. The FFDCA has provisions to grant regulatory exclusivity for statutorily defined time periods (in months or years) to the holder43 of the NDA for a product that is, for example, the first generic version of a drug to come to market, a drug used in the treatment of a rare disease or condition,44 certain pediatric uses of approved drugs, and new qualified infectious disease products.45 During the period of exclusivity, FDA does not grant marketing approval to another manufacturer's product. FDA may award a priority review voucher (shortening the time from an application's submission to FDA's approval decision) to the manufacturer with a successful NDA for a drug used for certain tropical diseases, rare pediatric diseases, or agents that present national security threats.46 The manufacturer may use the voucher (or sell it to another manufacturer) to get priority review of a subsequent NDA.

Other options fit limited situations and support shorter times from idea to approved public use. For example, the Project BioShield Act of 2004 and the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act of 2013 (PAHPRA) allow the HHS Secretary to authorize in certain circumstances the emergency use of products or uses that do not yet have FDA approval.47

|

Attribute |

Fast Track |

Breakthrough Therapy |

Accelerated Approval |

Animal Efficacy |

Priority Review |

|

Nature of program |

Product designation |

Product designation |

Process alteration |

Process alteration |

Product designation |

|

Authority |

FFDCA §506(b) |

FFDCA §506(a) |

21 C.F.R. 314 Subpart H FFDCA §506(c) |

21 C.F.R. 314 Subpart I |

CDER MAPP 6020.3 CBER SOPP 8405 |

|

Establishing vehicle |

FDAMA, FDASIA |

FDASIA |

rules, FDASIA |

rules |

policy, PDUFAa |

|

Qualifying criteria |

Would treat a serious condition (variously defined) |

||||

|

AND nonclinical or clinical data demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical need |

AND preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement on a clinically significant endpoint(s) over available therapies |

AND generally provides meaningful advantage over available therapies AND demonstrates an effect on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit or on an intermediate clinical endpoint |

AND human efficacy studies cannot be ethically or feasibly conducted AND safety has been established AND "adequate and well-controlled animal studies ... establish that the drug product is reasonably likely to produce clinical benefit in humans" |

AND if approved, would provide a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness |

|

|

Alternate qualifying criteria |

|

||||

|

Benefits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Postmarket requirements |

|

|

|||

Sources: FFDCA §506; 21 C.F.R. 314 Subparts H and I; and table from FDA, "Guidance for Industry: Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions––Drugs and Biologics," CDER and CBER, May 2014, http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM358301.pdf.

Notes:

BLA=biologics license application. CBER=Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. CDER=Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDAMA=FDA Modernization Act. FDASIA=FDA Safety and Innovation Act. FFDCA=Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. IND=investigational new drug application. MAPP=CDER Manual of Policies and Procedures. NDA=new drug application. PDUFA=Prescription Drug User Fee Act. SOPP=CBER Standard Operating Procedures and Policies.

a. Although priority review is not explicitly required by law, FDA has established it in practice. Various statutes, such as the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), refer to and sometimes require it.

b. Title VIII of FDASIA entitled "Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN)" provides incentives for the development of antibacterial and antifungal drugs for human use intended to treat serious and life threatening infections. Under GAIN, a drug may be designated as a qualified infectious disease product (QIDP) if it meets the criteria outlined in the statute. A drug that receives QIDP designation is eligible under the statute for fast track designation and priority review. However, QIDP designation is beyond the scope of this guidance.

c. Any supplement to an application under FFDCA §505 that proposes a labeling change pursuant to a report on a pediatric study under this section shall be considered to be a priority review supplement per FFDCA §505A as amended by Section 5(b) of the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act.

d. Any application or supplement that is submitted with a priority review voucher will be assigned a priority review. Priority review vouchers will be granted to applicants of applications for drugs for the treatment or prevention of certain tropical diseases, as defined in FFDCA §524(a)(3) and (4); for treatment of rare pediatric diseases, as defined in FFDCA §529(a)(3); or for treatments for agents that present national security threats, as defined in FFDCA §565A.

How FDA Regulates Approved Drugs

FDA's role in making sure a drug is safe and effective continues after the drug is approved and it appears on the market. FDA acts through its postmarket regulatory procedures after a manufacturer has sufficiently demonstrated a drug's safety and effectiveness for a defined population and specified conditions and the drug is FDA-approved. Manufacturers must report all serious and unexpected adverse reactions to FDA, and clinicians and patients may do so. FDA oversees surveillance, studies, labeling changes, and information dissemination, among other tasks, as long as the drug is sold.

FDA Entities Responsible for Drug Postapproval Regulation

Offices throughout FDA, mostly in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, address the safety of the drug supply. The primary focus of activity is the Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE). OSE uses reports of adverse events that consumers, clinicians, or manufacturers believe might be drug-related to "identify drug safety concerns and recommend actions to improve product safety and protect the public health."48 FDA activities regarding drug safety once a drug is on the market (postmarket or postapproval period) are diverse. FDA staff

- look for "signals" of safety problems of marketed drugs by reviewing adverse event reports through the MedWatch program;

- review studies conducted by manufacturers when required as a condition of approval;

- monitor relevant published literature;

- conduct studies using computerized databases;

- review errors related to similarly named drugs;

- conduct communication research on how to provide balanced benefit and risk information to clinicians and consumers; and

- remain in contact with international regulatory bodies.

Other CDER units evaluating safety issues include the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion; the Division of Drug Information; and the Office of Compliance, which has offices addressing drug security, manufacturing quality, and unapproved drugs and labeling. Outside of CDER, the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) performs field activities, including domestic and foreign inspections. The FDA human drugs program budget includes funding for CDER and the CDER-related activities of ORA.

Among the many advisory groups that work with FDA, two focus specifically on drug safety. The Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee met for the first time with this name in July 2002.49 Members, appointed by the commissioner, are nonfederal and represent areas of expertise in science, risk communication, and risk management. One member may be designated to represent consumer concerns; one nonvoting member may represent industry concerns. The group "advises the Commissioner or designee in discharging responsibilities as they relate to helping to ensure safe and effective drugs for human use."50

FDA created the Drug Safety Oversight Board as part of its 2005 Drug Safety Initiative and later required by FDAAA in 2007.51 Its members include both FDA personnel and representatives of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Defense, the Indian Health Service, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Its roles are to advise the CDER director "on the handling and communicating of important and often emerging drug safety issues" and to provide "a forum for discussion and input about how to address potential drug safety issues."52

FDA Drug-Regulation Activities

FDA postmarket drug safety and effectiveness activities address aspects of drug production, distribution, and use. This section highlights nine activities that have traditionally interested Congress in relation to drug safety and effectiveness: product integrity, labeling, reporting, surveillance, drug studies, risk management, information dissemination, off-label use, and direct-to-consumer advertising.

Product Integrity

Ensuring product integrity53 was the key task of FDA's predecessors in the early 1900s. Protecting the supply chain from counterfeit, diverted, subpotent, substandard, adulterated, misbranded, or expired drugs remains an essential concern of the agency. But as drug production has shifted to a global supply chain, FDA has broadened the scope of the way it monitors manufacturers, processers, packagers, importers, and distributors.54 The FFDCA dictates requirements that manufacturers must meet, and it allows FDA to regulate manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and transportation plans.55 For example, among many other requirements, the FFDCA requires (1) annual registration, including a unique facility identifier, of any domestic or foreign establishment "engaged in the manufacture, preparation, propagation, compounding, or processing of a drug or drugs" or their excipients (such as fillers, preservatives, or flavors) for U.S. distribution;56 (2) registration of importers;57 (3) submission of lists of products, including ingredients and labeling;58 (4) adherence to current good manufacturing practice (cGMP);59 (5) various inspection requirements including risk-based facility inspections, inspection of drug lots for packaging and labeling control,60 and "sampling and testing of in-process materials and drug products;"61 and (6) numerous reporting requirements, among other actions.

FDA monitors product integrity beyond the drug's initial manufacture. It continues as the drug moves throughout the supply chain from its manufacturer to one or more wholesale distributors to the entity that dispenses it to the patient. Title II of the Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013 (DQSA; P.L. 113-54), the Drug Supply Chain Security Act, established track-and-trace requirements for prescription drugs, to be implemented over a period of 10 years. Among other things, the law requires manufacturers and repackagers to a put a product identifier, including a standardized numerical identifier, on each package and homogenous case.62 With certain exceptions, exchange of transaction information, histories, and statements is required when a manufacturer, repackager, wholesale distributor, or dispenser transfers or accepts a drug. The law also requires a system of verification and notification when FDA or a trading partner within the supply chain suspects that a product may be suspect or illegitimate,63 and for the Secretary to establish national standards for the licensing of wholesale distributors and third-party logistics providers.64

One area of federal and state interest is the practice of drug compounding. While FDA regulates drug manufacturers, the regulation of pharmacies and pharmacists has generally resided with state boards of pharmacy. The regulation of compounding pharmacies—where a pharmacist compounds (mixes) ingredients to create a product that differs from an FDA-approved drug based on a prescription for a specific patient—is a state function. However, in past years, some businesses licensed as pharmacies have engaged in compounding large amounts of a drug without corresponding patient-specific prescriptions and then selling the drug out of state. In 2012, long-term concern about the practice came to the forefront with an epidemic of fungal meningitis that CDC and FDA have traced back to a compounding business. The following year, Title I of the DQSA, the Compounding Quality Act, created a new category of drug compounders called outsourcing facilities, a term that describes entities that compound sterile drugs in circumstances that go beyond what the FFDCA allows pharmacies to do under state regulation (e.g., an outsourcing facility might compound drugs in bulk for use in hospitals and other facilities).65 Unlike traditional compounding pharmacies, outsourcing facilities are required to register with FDA and are subject to CGMPs, in addition to other requirements.66

Reporting and Surveillance

One way FDA monitors the safety of approved drugs involves gathering information about possible adverse reactions to the products it has approved for U.S. use. Manufacturers must report all serious and unexpected adverse events (AEs) to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) within 15 days of becoming aware of them.67 Health professionals and patients may report adverse events to FDA's reporting system at any time.68 According to the July 2017 report from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), in CY2016, FDA received 1.2 million new reports of adverse events for prescription and over-the-counter drugs.69

The agency collects AE reports through MedWatch and uses the FAERS database70 to store and analyze them. Not all AEs may be actual drug reactions.71 Using large surveillance data sets such as FAERS and with an understanding of the pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic functioning of various drugs, FDA scientists review the reported AEs to assess which ones may indicate a drug problem. They then use information gleaned from the surveillance data to determine a course of action. FDA might recommend a change in drug labeling to alert users to a potential problem or, perhaps, require the manufacturer to study the observed association between the drug and the adverse event.

Unlike planned studies with hypotheses to support or refute, for which researchers gather information, most surveillance activities are characterized as passive, in that the information is submitted by others.72 The agency only learns of an adverse event when someone reports it. There are limitations to that approach. The reported event may signal a problem with the drug or be unrelated but have occurred coincident with the dosing. Other actual drug effects may be unrecognized as such and consequently not be reported. In addition, it is difficult to interpret the extent of a problem without knowing how many people took a specific drug.

In 2008, FDA began work on its Sentinel Initiative, both recognizing these limitations and responding to a requirement in FDAAA to create and maintain a Postmarket Risk Identification and Analysis System.73 With Sentinel, FDA began moving from its predominantly passive surveillance system to an active one. Building on surveillance activities already in place (e.g., MedWatch and FAERS) and using evolving computer technology, Sentinel uses data from public and private sources such as electronic health records and insurance claims and registries to expand its information base while protecting patient confidentiality.74 In 2016, Sentinel moved out of its pilot phase and began operating on a larger scale. An FDAAA-required independent, third-party interim assessment in 2015 noted that Sentinel had already formed partnerships with 19 data organizations covering 178 million lives, allowing more precise estimates of usage and possible adverse events. The analyses had informed FDA decisions to both take and not take actions.75 However, a 2017 article presented more mixed opinions. It described several researchers' disappointment in Sentinel's utility, noting "little measureable impact" despite the resources already committed. Other researchers, noting the difficulties in data surveillance, pointed to the value of Sentinel's continued efforts.76

Drug Studies

After a drug is on the market, FDA can recommend and ask product sponsors to conduct studies. As described below, the law authorizes FDA to require studies in the postapproval period. Two sets of situations—distinguished by when the requirement is set—involve required postapproval studies: when a requirement is attached to the initial approval of the drug and when FDA informs the sponsor of a required study once a drug is on the market.

Postmarket Studies Required upon Drug Approval

Accelerated Approval. When FDA grants accelerated approval, it attaches a postmarket study requirement to that approval.77 FDA regulations state, "Approval under this section will be subject to the requirement that the applicant study the drug further, to verify and describe its clinical benefit, where there is uncertainty as to the relation of the surrogate endpoint to clinical benefit, or of the observed clinical benefit to ultimate outcome."78

Animal Efficacy. When FDA grants approval based on its animal efficacy rule, it attaches a postmarket study requirement to that approval. The Animal Efficacy Rule allows manufacturers to submit effectiveness data from animal studies as evidence to support applications of certain new products "when adequate and well-controlled clinical studies in humans cannot be ethically conducted and field efficacy studies are not feasible."79 The regulations state,

The applicant must conduct postmarketing studies, such as field studies, to verify and describe the drug's clinical benefit and to assess its safety when used as indicated when such studies are feasible and ethical. Such postmarketing studies would not be feasible until an exigency arises.… Applicants must include as part of their application a plan or approach to postmarketing study commitments in the event such studies become ethical and feasible.80

Pediatric Assessments. When FDA approves a drug for which it has deferred the required pediatric assessment, it attaches a postmarket pediatric assessment requirement to that approval. The Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA, first authorized in P.L. 108-155) required that manufacturers submit a pediatric assessment with each submission of an application to market a new active ingredient, new indication, new dosage form, new dosing regimen, or new route of administration.81 The law specified situations in which the Secretary might defer or waive the pediatric assessment requirement. For a deferral, an applicant must include a timeline for completion of studies. The Secretary must review each approved deferral annually, for which the applicant must submit evidence of documentation of study progress.

When Otherwise Required by the Secretary. The FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-85) added another opportunity for a postmarket requirement at the time of approval. The Secretary may include in a drug's approval the requirement for specific postapproval studies or clinical trials.82

Postmarket Studies Required After Drug Approval

Pediatric Assessment. In addition to the pediatric assessment required as part of a drug's approval, PREA allows the Secretary, in certain circumstances, to require a pediatric assessment of a drug already on the market.83

Based on New Information Available to Secretary. The Secretary, under specified conditions after a drug is on the market, may require a study or a clinical trial.84 The Secretary may determine the need for such a study or trial based on newly acquired information. To require a postapproval study or trial, the Secretary must determine that (1) other reports or surveillance would not be adequate and (2) the study or trial would assess a known serious risk or signals of serious risk, or identify a serious risk. The law directs the Secretary regarding dispute resolution procedures.

Risk Management

With authority under the FFDCA or by its own practices, FDA has long implemented various tools in its attempt to ensure that the drugs it has approved for marketing in the United States are safe and effective for their intended and approved uses. In addition to the actions the agency requires of the manufacturers of all approved drugs, it may deem additional actions appropriate for specific drugs or specific circumstances surrounding a drug's use. Some of those additional actions are risk-management processes to identify and minimize risk to patients. The FDA Manual of Policies and Procedures notes that risk management attempts to "minimize [a drug's] risks while preserving its benefits."85 In that 2005 document, FDA described its approach to risk management as "an iterative process" that includes both risk assessment and risk minimization.

The FDAAA named the risk-management process risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) and expanded the risk-management authority of FDA.86 FDA practice had long included most of the elements that a REMS may include, but FDAAA gave FDA, through the REMS process, the authority for structured follow-through, dispute resolution, and enforcement.

FDA may require a REMS under specified conditions—including if it determines such a strategy is necessary to ensure that the benefits of a drug outweigh its risks. It may make the requirement when a manufacturer submits a new drug application, after initial approval or licensing, when a manufacturer presents a new indication or other change, or when the agency becomes aware of new information and determines a REMS is necessary.

As part of a REMS, the Secretary may require instructions to patients and clinicians, and restrictions on distribution or use (and a system to monitor their implementation). A REMS may include the following components:

Patient information. The manufacturer must develop material "for distribution to each patient when the drug is dispensed."87 This could be a Medication Guide, "as provided for under part 208 of title 21, Code of Federal Regulations (or any successor regulations),"88 or a patient package insert.89

Health care provider information. The manufacturer must create a communication plan, which could include sending letters to health care providers; disseminate information to providers about REMS elements to encourage implementation or explain safety protocols; disseminate information through professional societies about any serious risks of the drug and any protocol to assure safe use; or disseminate to health care providers information about drug formulations or properties, including the limitations of those properties and how they may be related to serious adverse events.90

Elements to assure safe use (ETASU). An ETASU is a restriction on distribution or use that is intended to (1) allow access to those who could benefit from the drug while minimizing their risk of adverse events and (2) block access to those for whom the potential harm would outweigh potential benefit. By including these restrictions, FDA can approve a drug that it otherwise would have to keep off the market because of the risk it would pose. FFDCA Section 505-1(f)(3) lists the types of restrictions FDA could require as

- health care providers who prescribe must have particular training or experience, or be specially certified;

- pharmacies, practitioners, or health care settings that dispense must be specially certified;

- the drug must be dispensed to patients only in certain health care settings, such as hospitals;

- the drug must be dispensed to patients with evidence or other documentation of safe-use conditions, such as laboratory test results;

- each patient using the drug must be subject to certain monitoring; and

- each patient using the drug must be enrolled in a registry.

Any approved REMS must include a timetable of when the manufacturer will provide reports to allow FDA to assess the effectiveness of the REMS components.91

Information Dissemination

FDA maintains several communications channels through which it distributes information on drug safety and effectiveness to clinicians, consumers, pharmacists, and the general public. An FDA web page titled "Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers" includes links to drug-specific information, potential signals of serious risks and summary statistics from FAERS,92 Drug Safety Communications, and FDA Drug Safety Podcasts.93 Other channels include FDA Drug Info Rounds94 and FDA Drug Information on Twitter.95

FDA has been required by law to take various actions regarding how it informs the public, expert committees, and others about agency actions and plans and information the agency has developed or gathered about drug safety and effectiveness. Examples include directing FDA to establish advisory committees (e.g., an Advisory Committee on Risk Communication to "advise the Commissioner on methods to effectively communicate risks associated with" FDA-regulated products);96 to report certain information to Congress (e.g., annual fiscal and performance reports related to user fees);97 to hold public meetings with stakeholders (e.g., public meeting with patients, health care providers, and others to discuss clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria);98 and to make certain information available on the agency's website (e.g., publication of action packages for product approval or licensure, including certain reviews).99

Labeling

What Is Labeling?

A drug's labeling is more than the sticker the pharmacy places on the amber vial it dispenses to a customer. FFDCA Section 201(m) defines labeling to include "... all labels and other written, printed, or graphic matter ... accompanying" the drug. FDA regulations on labeling100 dictate the material the labeling must provide along with required formatting.101 FDA included the following description when it issued its 2006 final rule on labeling:102

A prescription drug product's FDA approved labeling (also known as "professional labeling," "package insert," "direction circular," or "package circular") is a compilation of information about the product, approved by FDA, based on the agency's thorough analysis of the new drug application (NDA) or biologics license application (BLA) submitted by the applicant. This labeling contains information necessary for safe and effective use. It is written for the health care practitioner audience, because prescription drugs require "professional supervision of a practitioner licensed by law to administer such drug" (section 503(b) of the act (21 U.S.C. 353(b))).

FDA regulations on prescription drug advertising refer to examples of labeling:103

Brochures, booklets, mailing pieces, detailing pieces, file cards, bulletins, calendars, price lists, catalogs, house organs, letters, motion picture films, film strips, lantern slides, sound recordings, exhibits, literature, and reprints and similar pieces of printed, audio or visual matter descriptive of a drug and references published (for example, the Physician's Desk Reference) for use by medical practitioners, pharmacists, or nurses, containing drug information supplied by the manufacturer, packer, or distributor of the drug and which are disseminated by or on behalf of its manufacturer, packer, or distributor are hereby determined to be labeling as defined in section 201(m) of the FD&C Act.

FDA requires that labeling begin with a highlights section that includes, if appropriate, black-box warnings, so called because they are bordered in black to signify their importance.104 The regulations list the required elements of labeling: indications and usage, dosage and administration, dosage forms and strengths, contraindications, warnings and precautions, adverse reactions, drug interactions, use in specific populations, drug abuse and dependence, overdosage, clinical pharmacology, nonclinical toxicology, clinical studies, references, how supplied/storage and handling, and patient counseling information.105

How Is Labeling Used?

Labeling plays a major role in the presentation of safety and effectiveness information. It is a primary source of prescribing information used by clinicians. The manufacturer submits labeling for publication in the widely used Physician's Desk Reference and is the basis of several patient-focused information sheets that manufacturers, pharmacy vendors, and many Web-based drug information sites produce.106 When FDA determines that additional information is necessary for safe use, it may require the manufacturer to produce a Medication Guide.107 The agency, through its Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP), conducts and supports research on risk and benefit communication to both professionals and consumers.108 OPDP looks for ways to present information to consumers that is accessible, accurate, and up-to-date. FDA-approved labeling is relevant to discussions of insurance or benefits coverage, market exclusivity periods, and liability.109

When and How May Labeling Be Changed?

Adverse events sometimes warrant regulatory actions such as labeling changes, letters to health professionals, or, once in a great while, a drug's withdrawal from the market. The regulations refer to required labeling revisions as soon as there is reasonable evidence—not proof—of a causal association with a clinically significant hazard.110

FDA can request labeling changes based on information it gathers from mandatory industry reports to FAERS, manufacturer-submitted postmarket studies, and voluntary adverse event reports from clinicians and patients.111 The agency may, upon learning of new relevant safety information, require a labeling change.112

When a manufacturer of an innovator (brand-name) drug believes data from original or published studies support a new use for a drug, a manufacturer itself can initiate a label change to support a new marketing claim.113 The manufacturer can submit to FDA the new data in a supplement to the original NDA and request that FDA allow it to modify the labeling. In addition, if a manufacturer of an innovator drug submits a supplement to strengthen warning labeling, regulations describe when the change can be made prior to FDA approval.114

The FFDCA requires that a generic drug have the same labeling as the innovator drug on which its application draws, with some exceptions.115 For example, a generic drug may omit from its labeling certain patent- and exclusivity-protected information concerning the pediatric use of the brand-name drug, and may be required to include a disclaimer with respect to the omitted information.116 This sameness requirement has implications when an injured party seeks to sue the generic manufacturer, and when new safety information becomes available when only generic products remain on the market.117

In November 2013, FDA issued a proposed rule to allow ANDA holders to voluntarily update drug labeling to reflect certain types of newly acquired information related to drug safety even if that labeling differs from that of the brand reference drug.118 Specifically, the ANDA holder would be allowed to distribute the revised product labeling with respect to the safety-related change, on a temporary basis, upon submission to FDA of a ''changes being effected'' supplement. The safety-related change(s) proposed in the supplement would be made publicly available to prescribers and the public on the agency's website while FDA reviews the supplement. The ANDA supplement for that safety-related labeling change would be approved upon approval of the same labeling change for the RLD (i.e., the brand-name or innovator drug). This proposed change has been met with some opposition, including from the generic drug industry, which has claimed that the rule would expose generic companies to new legal liability.119 A final rule has not been promulgated.

Off-Label Use

As described earlier, FDA approves a drug for U.S. sale based on its manufacturer's new drug application, which contains evidence of safety and effectiveness in its intended use, manufacturing requirements, and labeling. Despite the indications for use in the approved labeling, a licensed physician may—except in highly regulated circumstances120—prescribe the approved drug without restriction. A prescription to an individual whose demographic or medical characteristics differ from those indicated in a drug's FDA-approved labeling is called off-label use and is accepted medical practice.121 The FFDCA prohibits a manufacturer from selling a misbranded product, and deems a drug to be misbranded if its labeling is false or misleading.122 FDA has interpreted the FFDCA, therefore, to prohibit a manufacturer from promoting or advertising a drug for any use not listed in the FDA-approved labeling, which contains those claims for which FDA has reviewed safety and effectiveness evidence.123 However, FDA's interpretation has been challenged and is in dispute.124

|

Examples of Off-Label Use

|

Off-label use presents an evaluation problem to FDA safety reviewers. Using drugs in new ways for which researchers have not yet demonstrated safety and effectiveness can create problems that premarket studies did not address. Manufacturers rarely design studies to establish the safety and effectiveness of their drugs in off-label uses, and individuals and groups wanting to conduct such studies face difficulties finding funding.

Drug and device companies have argued that current regulations prevent them from distributing important information to physicians about unapproved, off-label uses of their products.125 In November 2016, FDA held a two-day public meeting to obtain input from various groups regarding off-label uses of approved or cleared medical products.126 In January 2017, FDA issued draft guidance explaining the agency's policy about medical product communications that include data and information that are not contained in FDA-approved labeling, but that concern the approved uses of their products.127 The draft guidance is in a question and answer format and addresses frequently asked questions. Among other things, the draft guidance provides examples of the kinds of information that the agency considers consistent with FDA-required labeling for a product (e.g., information that provides additional context about adverse reactions associated with a drug's approved use[s] as reflected in the FDA-required labeling), as well as the kinds of information that are not consistent with FDA-required labeling for a product (e.g., if a drug is approved for treatment of only one disease, and the company's communication provides information about using the product to treat a different disease).

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Advertising

FDA regulates the advertising of prescription drugs.128 Although the Federal Trade Commission regulates nonprescription drug advertising, the FDA regulates the product labeling that the nonprescription drug ads must reflect. While the law generally prohibits FDA from requiring preapproval of an ad, manufacturers are required to submit their ads to the agency upon release.129

FDAAA expanded and strengthened FDA's enforcement tools regarding advertising, including by authorizing the agency to require submission of a television advertisement for review not later than 45 days before its dissemination.130 In conducting a review of a television advertisement, the Secretary may make recommendations with respect to information included in the label of the drug on (1) changes that are necessary to protect the consumer good and well-being, or that are consistent with prescribing information for the product under review, and (2) "statements for inclusion in the advertisement to address the specific efficacy of the drug as it relates to specific population groups, including elderly populations, children, and racial and ethnic minorities," if appropriate and if such information exists. The law allows the agency to recommend, but not require, changes in the ad. The law also allows FDA to require that an ad include certain disclosures without which it determines that the ad would be false or misleading. These disclosures could include the date of drug's approval, as well as information about a serious risk listed in a drug's labeling. In 2012, FDA issued draft guidance addressing for which categories of TV ads the agency generally intends to enforce the pre-dissemination review requirement.131 This guidance has not been finalized.

Television and radio ads must present the required information on side effects and contraindications in a "clear, conspicuous, and neutral manner."132 Civil penalties are authorized for the dissemination of a false or misleading DTC advertisement. Any published DTC advertisement must include the following statement printed in conspicuous text: "You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit http://www.fda.gov/medwatch, or call 1-800-FDA-1088."133

Appendix. Abbreviations and Acronyms

|

AERS |

Adverse Event Reporting System, now FAERS |

|

ANDA |

abbreviated new drug application |

|

BLA |

biologics license application |

|

BPCA |

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act |

|

CBER |

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CDER |

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research |

|

C.F.R. |

Code of Federal Regulations |

|

DTC |

direct-to-consumer, as in advertising |

|

ETASU |

elements to assure safe use, as in REMS |

|

FAERS |

FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, formerly AERS |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FDAAA |

Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, 2007 |

|

FDAMA |

Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act, 1998 |

|

FDASIA |

Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, 2012 |

|

FDARA |

FDA Reauthorization Act, 2017 |

|

FFDCA |

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act |

|

GAIN |

Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now Act |

|

GDUFA |

Generic Drug User Fee Amendments |

|

IND |

investigational new drug |

|

MAPP |

Manual of Policies and Procedures |

|

NDA |

new drug application |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

OPDP |

Office of Prescription Drug Promotion |

|

ORA |

Office of Regulatory Affairs |

|

OSE |

Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, formerly Office of Drug Safety |

|

PAHPRA |

Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act |

|

PDUFA |

Prescription Drug User Fee Act or Amendments |

|

PREA |

Pediatric Research Equity Act |

|

QIDP |

qualified infectious disease product |

|

REMS |

risk evaluation and mitigation strategy |

|

SOPP |

Standard Operating Procedures and Policies |

|

USC |

United States Code |