Introduction

"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is the concept that a financial firm's disorderly failure would cause widespread disruptions in financial markets and result in devastating economic and societal outcomes that the government would feel compelled to prevent, perhaps by providing direct support to the firm. Such firms are a source of systemic risk—the potential for widespread disruption in or even total collapse of the financial system.1

Although TBTF has been a perennial policy issue, it was highlighted by the near-collapse of several large financial firms in 2008. Some of these large firms were nonbank financial firms, but a few were depository institutions. To avert the imminent failures of Wachovia and Washington Mutual, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) arranged for them to be acquired by other banks without government financial assistance. Citigroup and Bank of America were offered additional preferred shares through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and government guarantees on selected assets they owned.2 In many of these cases, policymakers justified government intervention on the grounds that the firms were "systemically important" (popularly understood to be synonymous with too big to fail). Some firms were rescued on those grounds once the crisis struck, although the government had no explicit policy to rescue TBTF firms beforehand.

In response to the crisis, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (hereinafter, the Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203), a comprehensive financial regulatory reform, was enacted in 2010.3 Among its stated purposes are "to promote the financial stability of the United States…, to end "too big to fail," to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts."

The Dodd-Frank Act took a multifaceted approach to addressing the TBTF problem. This report focuses on one pillar of that approach—the Federal Reserve's (Fed's) enhanced (heightened) prudential regulation for all banks that have more than $50 billion in assets. Recent Congresses have debated modifying this enhanced regulatory regime, with several proposals to reduce the number of firms subject to the regime. In the 115th Congress, H.R. 10, the Financial CHOICE Act of 2017, would provide banks with an "off ramp" from enhanced regulation if they maintained a leverage ratio of 10%.4 H.R. 3312, the Systemic Risk Designation Improvement Act of 2017, would replace the $50 billion threshold with a case-by-case designation process, while automatically subjecting banks that have been designated as globally-systemically important banks (G-SIBs) by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international forum. Section 401 of S. 2155, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, would automatically subject banks that had been designated as G-SIBs and banks with over $250 billion in assets to enhanced regulation. Banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets would still be subject to supervisory stress tests, and the Fed would have discretion to apply other individual enhanced prudential provisions to these banks if it would promote financial stability or the institution's safety and soundness. Banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion would no longer be subject to enhanced regulation, except for the risk committee requirement.

This report begins with a description of enhanced prudential regulation. It discusses the advantages and disadvantages to this approach to mitigating TBTF. It then considers whether banks with more than $50 billion in assets are systemically important, and then discusses proposals to modify the current regime, notably the $50 billion threshold. Finally, the report presents its key findings.

Enhanced regulation of banks with more than $50 billion in assets is only one facet of the current approach to addressing TBTF. This report focuses on enhanced regulation and does not analyze other current policies or proposed alternatives to address TBTF. For an overview of the TBTF issue and policy options, see CRS Report R42150, Systemically Important or "Too Big to Fail" Financial Institutions, by [author name scrubbed].

Who Is Subject to Enhanced Prudential Regulation?

Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act creates an enhanced prudential regulatory regime that automatically applies to all bank holding companies with total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more and nonbank financial firms that are designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) as systemically important. Title I allows the Fed to tailor differing prudential standards by institution or subgroup based on any risk-related factor.

Banks

Enhanced regulation automatically applies to U.S. bank holding companies (BHCs) with more than $50 billion in assets. The BHC structure allows for a large, complex financial firm to operate multiple subsidiaries in different financial sectors, including banks. In general, the regime's requirements are applied to all parts of the bank holding company, not just its banking subsidiaries. If a bank does not have a holding company structure, it is not subject to enhanced regulation. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) found one bank that is currently over $50 billion and does not have a BHC structure.5

Some large investment banks, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, were granted bank holding company charters in 2008, whereas others failed or were acquired by BHCs; as a result, all of the largest U.S. investment banks are now BHCs, subject to the enhanced prudential regime. Under Title I's "Hotel California" provision, investment banks or other BHCs with more than $50 billion in assets that participated in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) cannot escape enhanced regulation by debanking (i.e., divesting of their depository business).6

The enhanced prudential regime also applies to foreign banking organizations that have more than $50 billion in global assets and operate in the United States.7 However, the implementing regulations have imposed significantly lower requirements on foreign banks with less than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets compared to those with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets.8 Foreign banks with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets must form intermediate holding companies for their U.S. operations; those intermediate holding companies are essentially treated as equivalent to U.S. banks for purposes of applicability of the enhanced regime and bank regulation more generally.9 For example, the intermediate holding company is also subject to the same general capital requirements applicable to all U.S. banks. For foreign banks with less than $50 billion in U.S. assets, the rule defers to the parent bank's home country regulation in several areas (e.g., stress testing) when it is comparable to U.S. regulation. But they must still comply with the emergency debt-to-equity ratio, the risk committee requirements, and a streamlined version of the living wills requirements.

Hereafter, the report will refer to the bank holding companies and foreign banking operations meeting the criteria described above as banks with more than $50 billion in assets, unless otherwise noted.

CRS was not able to locate an official list of banks subject to enhanced regulation (which varies, depending on the requirement, for foreign banks). There is, however, official information available on which banks have participated in two specific requirements under enhanced regulation. In 2017, 27 BHCs and 12 intermediate holding companies of foreign banks were subject to the Title I Federal Reserve stress test or would be subject to future stress tests because they had more than $50 billion in U.S. assets (see Table 1).10 About 130 banks (foreign and domestic) submitted resolution plans (or living wills) pursuant to Title I when the requirement came into effect, however, because they have more than $50 billion in worldwide assets and operate in the United States.11

Table 1. Banks with More Than $50 Billion in Assets

(as of June 30, 2017; dollar amounts in billions)

|

Institution Name |

Assets |

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

$2,563 |

|

Bank Of America Corporation |

$2,256 |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

$1,931 |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

$1,864 |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

$907 |

|

Morgan Stanley |

$841 |

|

U.S. Bancorp |

$464 |

|

PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. |

$372 |

|

Bank Of New York Mellon Corporation |

$355 |

|

Capital One Financial Corporation |

$351 |

|

TD Group U.S. Holdings LLC |

$349 |

|

HSBC North America Holdings Inc. |

$308 |

|

State Street Corporation |

$238 |

|

BB&T Corporation |

$221 |

|

Credit Suisse Holdings (USA), Inc. |

$215 |

|

Suntrust Banks, Inc. |

$207 |

|

DB Usa Corporation |

$191 |

|

Barclays US LLC |

$179 |

|

American Express Company |

$167 |

|

Ally Financial Inc. |

$164 |

|

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. |

$152 |

|

MUFG Americas Holdings Corporation |

$151 |

|

RBC USA Holdco Corporation |

$147 |

|

UBS Americas Holding LLC |

$143 |

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

$141 |

|

BNP Paribas USA, Inc. |

$140 |

|

Keycorp |

$136 |

|

Santander Holdings USA, Inc. |

$135 |

|

BMO Financial Corp. |

$130 |

|

Northern Trust Corporation |

$126 |

|

Regions Financial Corporation |

$125 |

|

M&T Bank Corporation |

$121 |

|

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated |

$101 |

|

Discover Financial Services |

$94 |

|

BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc. |

$87 |

|

Comerica Incorporated |

$72 |

|

Zions Bancorporation |

$65 |

|

CIT Group Inc. |

$50 |

Source: Federal Reserve data reported on Form Y-9C.

There are a number of other large financial firms operating in the United States that are not BHCs and are not automatically subject to enhanced regulation, which are discussed below.

Thrifts

Similar to BHCs, thrift holding companies (THCs) have subsidiaries that accept deposits, make loans, and can also have nonbank subsidiaries. THCs are also regulated by the Fed. However, to date, enhanced prudential regulatory requirements have not been applied to thrift (savings and loan) holding companies with $50 billion or more in assets, because implementation of the Dodd-Frank Act is ongoing and prefatory material accompanying a 2014 regulation noted that "the Board may apply additional prudential requirements to certain savings and loan holding companies that are similar to the enhanced prudential standards if it determines that such standards are consistent with the safety and soundness of such companies."12 Official regulatory data report six THCs with more than $50 billion in assets; they are predominantly insurance or investment companies.

Other Financial Firms

Credit unions, securities holding companies, and other nonbank financial firms with more than $50 billion in assets are also not automatically subject to enhanced regulation. However, the FSOC may designate any nonbank financial firm as a systemically important financial institution (SIFI) if its failure or activities could pose a risk to financial stability. Designated SIFIs are then subject to the Fed's enhanced prudential regulation. Since inception, FSOC has designated three insurers (AIG, MetLife, and Prudential Financial) and one financial firm (GE Capital) as SIFIs. MetLife's designation was subsequently invalidated by a court decision13, and GE Capital's and AIG's designations were later rescinded by FSOC.14 Because rules implementing most provisions for nonbank SIFIs have not yet been issued—and because this report focuses on banks—the application of the provisions discussed below to nonbank SIFIs is not covered.

Although there is not an official source, a query of the private firm SNL Financial's database identified 43 U.S. nonbank financial firms with more than $50 billion in assets in 2016. These firms include broker-dealers, insurance underwriters, specialty lenders, asset managers, investment companies, and financial technology companies. A Credit Union Times database includes only one credit union with more than $50 billion in assets (Navy Federal Credit Union).15 Many investment companies have more than $50 billion in assets under management; these are not assets that they own, but rather assets that they invest at the behest of customers.

What Requirements Must Banks Comply With Under Enhanced Regulation?

All bank holding companies are subject to long-standing prudential (safety and soundness) regulation conducted by the Fed. The novelty in the Dodd-Frank Act was to create a group of specific prudential requirements that apply only to large banks as described in the previous section.16 Many of these requirements overlap with parts of Basel III, an international agreement reached after the financial crisis to which the United States is a party.

Under Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Fed is responsible for administering enhanced prudential regulation. It promulgates regulations implementing the regime (based on recommendations, if any, made by FSOC) and supervises firms subject to the regime. The Dodd-Frank regime is referred to as enhanced or heightened because it involves higher or more stringent standards to banks with more than $50 billion in assets than it applies to smaller banks. It is a prudential regime because the regulations are intended to contribute toward the safety and soundness of the banks subject to the regime. The Fed's cost of administering the regime is financed through assessments on firms subject to the regime.

The following sections provide more detail on the requirements that Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act places on banks with more than $50 billion in assets.17 As noted below, some parts of enhanced regulation have still not been implemented through final rules.

Stress Tests and Capital Planning

Stress tests and capital planning are two enhanced requirements that have been implemented together. Title I requires company-run stress tests for any (bank or nonbank) financial firm with more than $10 billion in assets and Fed-run stress tests (called DFAST) for any bank holding company or nonbank SIFI with more than $50 billion in assets. These requirements were implemented through final rules in 2012 and were effective beginning in 2013.18

Stress tests attempt to project the losses that banks would suffer under a hypothetical deterioration in economic and financial conditions to determine whether banks would remain solvent in a future crisis. Unlike general capital requirements that are based on current asset values, the stress tests incorporate an adverse scenario that focuses on specific areas of concern each year. For example in 2017, the adverse scenario is "characterized by a severe global recession that is accompanied by a period of heightened stress in corporate loan markets and commercial real estate markets."19

Capital requirements are intended to ensure that banks have enough capital backing their assets to absorb any unexpected losses on those assets without resulting in insolvency. Title I requires enhanced capital requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. Overall capital requirements were revamped after the financial crisis through Basel III. Basel III did not include enhanced capital requirements at the $50 billion threshold, but it did include more stringent capital requirements for the largest banks (described below in "What Other Size-Based Requirements Exist in Bank Regulation?"). For banks with more than $50 billion in assets, enhanced capital requirements were primarily implemented through capital planning requirements that are tied to stress test results.

The final rule for capital planning was implemented in 2011.20 Under the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR), banks must submit a capital plan to the Fed annually. The capital plans must include a projection of the expected uses and sources of capital, including the planned issuance of debt or equity and the planned payment of dividends. The plan must demonstrate that the bank will remain in compliance with capital requirements under the stress tests.

If the Fed rejects the bank's capital plan (because the bank would have insufficient capital under the stress tests, for example), the bank will not be allowed to make any capital distributions, including dividend payments, until a revised capital plan is resubmitted and approved by the Fed. In 2017, the Fed removed qualitative requirements from the capital planning process for banks with less than $250 billion in assets that are not complex.21 Each year, the Fed has required some banks to revise their capital plans or objected to them on qualitative or quantitative grounds, or due to weaknesses in their process.22

Resolution Plans ("Living Wills")

Policymakers claimed that one reason they intervened to prevent large financial firms from failing during the financial crisis was because the opacity and complexity of these firms made it too difficult to wind them down quickly and safely. Title I requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets to periodically submit resolution plans (popularly known as "living wills") to the Fed, FSOC, and FDIC that explain how they can be safely wound down in the event of their failures.23 The living wills requirement was implemented through a final rule in 2011, and it became fully effective at the end of 2013.24 The final rule required resolution plans to include details of the firm's ownership, structure, assets, and obligations; information on how the firm's depository subsidiaries are protected from risks posed by its nonbank subsidiaries; and information on the firm's cross-guarantees, counterparties, and processes for determining to whom collateral has been pledged.

In the final rule, the regulators highlighted that the resolution plans would help them understand the firms' structure and complexity, as well as their resolution processes and strategies, including cross-border issues for banks operating internationally. Notably, the resolution plan is required to explain how the firm could be resolved without disrupting financial stability under the bankruptcy code25—as opposed to being liquidated by the FDIC under the Orderly Liquidation Authority created by Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act.26 The plan is required to explain how the firm can be wound down in a stressed environment in a "rapidly and orderly" fashion without receiving "extraordinary support" from the government (as some firms received during the crisis) or posing systemic risk. To do so, the plan must include information on core business lines, funding and capital, critical operations, legal entities, information systems, and which jurisdictions it is operating in.

The resolution plans are divided into a public part that is disclosed and a private part that contains confidential information. Some of the resolution plans submitted have been tens of thousands of pages long.27 For banks with less than $100 billion in assets that are mainly depositories, there are reduced requirements for the plans. In addition, foreign banks with less than $50 billion in U.S. assets must file a limited resolution plan. Regulators have discussed further streamlining.28

If regulators find that a plan is incomplete, deficient, or not credible, they may require the firm to revise and resubmit. If the firm cannot resubmit an adequate plan, regulators have the authority to take remedial steps against it—increasing its capital and liquidity requirements; restricting its growth or activities; or ultimately taking it into resolution. Multiple firms' plans have been found insufficient since the process began in 2013, including all eleven that were submitted and subsequently resubmitted in the first wave.29 In 2016, Wells Fargo became the first bank to be sanctioned for failing to submit an adequate living will.30

Liquidity Requirements

Bank liquidity refers to a bank's ability to meet cash flow needs and readily convert assets into cash. Banks are vulnerable to liquidity crises because of the liquidity mismatch between illiquid loans and deposits that can be withdrawn on demand. Although all banks are regulated for liquidity adequacy, Title I requires more stringent liquidity requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. These liquidity requirements are being implemented through three rules: (1) a 2014 final rule implementing firm-run liquidity stress tests, (2) a 2014 final rule implementing the Fed-run liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), and (3) a 2016 proposed rule that would implement the Fed-run net stable funding ratio (NSFR).31 The firm-run liquidity stress tests apply to all banks with more than $50 billion in assets, including intermediate holding companies of foreign banks. The LCR and NSFR apply to two sets of banks. A more stringent version applies to banks with at least $250 billion in assets and $10 billion in on-balance sheet foreign exposure. A less stringent version applies to banks with $50 billion to $250 billion in assets, except those with significant insurance or commercial operations. Regulators plan to issue rules extending the LCR and NSFR to large foreign banks operating in the United States at a later date.

A final rule implementing firm-run liquidity stress tests was issued in 2014, effective January 2015 for U.S. banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.32 The rule requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets to establish a liquidity risk management framework involving a bank's management and board, conduct monthly internal liquidity stress tests, and maintain a buffer of high quality liquid assets.

A final rule implementing the liquidity coverage ratio was issued in 2014.33 The LCR came into effect at the beginning of 2015 and was fully phased in at the beginning of 2017. The LCR aims to require banks to hold enough high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to match net cash outflows over 30 days in a hypothetical scenario of market stress where creditors are withdrawing funds.34 An asset can qualify as a HQLA if it has lower risk, has a high likelihood of remaining liquid during a crisis, is actively traded in secondary markets, is not subject to excessive price volatility, can be easily valued, and is accepted by the Fed as collateral for loans. Different types of assets are relatively more or less liquid, and there is disagreement on what the cutoff point should be to qualify as a HQLA under the LCR. In the LCR, eligible assets are assigned to one of three categories. Assets assigned to the most liquid category are given more credit toward meeting the requirement, and assets in the least liquid category are given less credit.

A proposed rule to implement the net stable funding ratio was issued in 2016.35 The NSFR is proposed to come into effect at the beginning of 2018. The NSFR would require banks to have a minimum amount of stable funding backing their assets over a one-year horizon. Different types of funding and assets receive different weights based on their stability and liquidity, respectively, under a stressed scenario. The rule defines funding as stable based on how likely it is to be available in a panic, classifies it by type, counterparty, and time to maturity. Assets that do not qualify as HQLA under the LCR require the most backing by stable funding under the NSFR. Long-term equity gets the most credit toward fulfilling the NSFR, insured retail deposits get medium credit, and other types of deposits and long-term borrowing get less credit. Borrowing from other financial institutions, derivatives, and certain brokered deposits cannot be used to meet the rule.

Counterparty Exposure Limits

One source of systemic risk associated with TBTF comes from "spillover effects." When a large firm fails, it imposes losses on its counterparties. If large enough, these losses could be debilitating to the counterparty, thus causing stress to spread to other institutions and further threaten financial stability. Title I requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets to limit their exposure to unaffiliated counterparties on an individual counterparty basis and to periodically report on their credit exposures to counterparties. In 2011, the Fed proposed rules implementing these provisions, but these provisions were not included in subsequent final rules.36 In 2016, the Fed reproposed a rule to implement a single counterparty credit limit (SCCL); to date, the counterparty exposure reporting requirements have not been reproposed.37

Counterparty exposure for all banks was subject to regulation before the crisis, but did not cover certain off balance sheet exposures or exposures at the holding company level.38 In the 2016 proposal, the SCCL was tailored to have increasingly stringent requirements as asset size increases. For banks with more than $50 billion in assets and less than $250 billion in total assets or $10 billion in foreign assets, net counterparty credit exposure would be limited to 25% of the bank's capital. There are two higher thresholds for larger banks that further limit counterparty exposure based on the systemic importance of the bank and its counterparty.

The 2011 credit exposure reporting proposal would have required banks to regularly report on the nature and extent of their credit exposures to significant counterparties. These reports would help regulators understand spillover effects if firms experienced financial distress. The proposed SCCL rule states that future rulemaking implementing the credit exposure reports will be "informed" by the SCCL framework.

Risk Management Requirements

The board of directors of publicly traded companies oversees the company's management on behalf of shareholders. Title I requires publicly traded banks with at least $10 billion in assets to form risk committees on their boards of directors that include a risk management expert responsible for oversight of the bank's risk management. Title I also requires the Fed to develop overall risk management requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. A final rule implementing this provision was issued by the Fed in 2014, effective in January 2015 for domestic banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.39 The rule requires that banks with more than $10 billion in assets form a risk committee led by an independent director. The rule requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets to employ a chief risk officer responsible for risk management.

Provisions That Are Triggered in Response to Financial Stability Concerns

Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act provides several powers to—depending on the provision—FSOC, the Fed, or the FDIC to use when the respective entity believes that a bank with more than $50 billion in assets poses a threat to financial stability. Unlike the provisions described earlier in this section, these provisions generally do not require any ongoing compliance and would be triggered only when a perceived threat to financial stability had arisen.

Some of the following powers are similar to powers that bank regulators already have over all banks, but are new powers over nonbank SIFIs. However, they are noted here because they, to varying degrees, expand regulatory authority (or extend authority from bank subsidiaries to bank holding companies) over banks with more than $50 billion in assets vis-a-vis smaller banks.

FSOC Reporting Requirements. To determine whether a bank with more than $50 billion in assets poses a threat to financial stability, FSOC may require the bank to submit certified reports. FSOC may make information requests only if publicly available information is not available, however.

Mitigation of Grave Threats to Financial Stability. When at least two-thirds of FSOC find that a firm poses a grave threat to financial stability, the Fed may limit the firm's mergers and acquisitions, restrict specific products it offers, and terminate or limit specific activities. If none of those steps eliminates the threat, the Fed may require it to divest assets. The firm may request a hearing with the Fed to contest the Fed's actions. To date, this provision has not been triggered, and the FSOC has never identified any bank as posing a grave threat.

Acquisitions. Title I broadens the requirement for banks with more than $50 billion in assets to provide the Fed with prior notice of U.S. nonbank acquisitions that exceed $10 billion in assets and 5% of the acquisition's voting shares, subject to various statutory exemptions. The Fed is required to consider whether the acquisition would pose risks to financial stability or the economy.

Emergency 15-to-1 Debt-to-Equity Ratio. For banks with more than $50 billion in assets, Title I creates an emergency limit of 15-to-1 on its ratio of liabilities to equity capital (sometimes referred to as a leverage ratio).40 A final rule implementing this provision was issued by the Fed in 2014 and was implemented in June 2014 for domestic banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.41 The ratio is applied only if a bank receives written warning from FSOC that it poses a "grave threat to U.S. financial stability," and ceases to apply when the bank no longer poses a grave threat. To date, this provision has not been triggered, and FSOC has never identified any bank as posing a grave threat.

Early Remediation Requirements. Early remediation is the principle that financial problems at banks should be addressed early before they become more serious. Title I requires the Fed to "establish a series of specific remedial actions" to reduce the probability that a bank with more than $50 billion in assets experiences financial distress will fail. This establishes a requirement for bank holding companies similar in spirit to the prompt corrective action requirements that apply to insured depository subsidiaries. Unlike prompt corrective action, the early remediation requirements are not based only on capital adequacy. As the financial condition of the firm deteriorates, statute requires the steps taken under early remediation to become more stringent, increasing in four steps from heightened supervision to resolution. The Fed issued a proposed rule in 2011 to implement this provision that to date has not been finalized.42

Expanded FDIC Examination and Enforcement Powers. Title I expands the FDIC's examination and enforcement powers. In order to determine whether an orderly liquidation under Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act is necessary, the FDIC is granted authority to examine the condition of banks with more than $50 billion in assets. Title I also grants the FDIC enforcement powers over banks with more than $50 billion in assets that pose a risk to the Deposit Insurance Fund.

What Other Size-Based Requirements Exist in Bank Regulation?

U.S. regulators have described the current bank prudential regulatory regime as tiered regulation, meaning that increasingly stringent regulatory requirements are applied as metrics, such as a bank's size, increase.43 These different tiers are applied on an ad hoc basis; in some cases, statute requires a given regulation to be applied at a certain size; in some cases, regulators have discretion to apply a regulation at a certain size; and in other cases, regulators must apply a regulation to all banks. In addition to $50 billion, notable thresholds found in bank regulation are $1 billion, $10 billion, "advanced approaches" banks, and "global systemically important banks" (G-SIBs).

Prudential Requirements for Advanced Approaches and G-SIBs. In conjunction with the Dodd-Frank Act, bank regulation was reformed after the financial crisis by Basel III, a nonbinding international agreement that the United States is currently implementing.44 One tier of enhanced regulation applies to banks subject to the Basel III "advanced approaches" rule, which are those banks with $250 billion or more in assets or $10 billion or more in foreign exposure.45 Another tier of regulation applies to G-SIBs. Since 2011, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international forum that coordinates the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies, has annually designated G-SIBs based on the banks' cross-jurisdictional activity, size, interconnectedness, substitutability, and complexity.46 The FSB has currently designated 30 banks as G-SIBs, 8 of which are headquartered in the United States. In addition, several of the foreign G-SIBs have U.S. subsidiaries.47 U.S. bank regulators have incorporated the Advanced Approaches and G-SIB definitions into U.S. regulation for purposes of applying the following regulations:

- Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). Leverage ratios determine how much capital banks must hold relative to their assets without adjusting for the riskiness of their assets. Advanced approaches banks must meet a 3% SLR, which includes off-balance-sheet exposures. In April 2014, the U.S. bank regulators adopted a joint rule that would require the G-SIBs to meet an SLR of 5% at the holding company level in order to pay all discretionary bonuses and capital distributions and 6% at the depository subsidiary level to be considered well capitalized as of 2018.48

- G-SIB Capital Surcharge. Basel III also required G-SIBs to hold relatively more capital than other banks in the form of a common equity surcharge of at least 1% to "reflect the greater risks that they pose to the financial system."49 In July 2015, the Fed issued a final rule that began phasing in this capital surcharge in 2016.50 Currently, the surcharge applies to the eight G-SIBs, but under its rule, it could designate additional firms as G-SIBs, and it could increase the capital surcharge to as high as 4.5%. The Fed stated that under its rule, most G-SIBs would face a higher capital surcharge than required by Basel III.

- Countercyclical Capital Buffer. In addition, the banking regulators issued a final rule implementing a Basel III countercyclical capital buffer applied to the advanced approaches banks. The countercyclical buffer would require advanced approaches banks to hold more capital than other banks when regulators believe that financial conditions make the risk of losses abnormally high. It is currently set at zero, but can be modified over the business cycle.51 Because the countercyclical buffer has not yet been in place for a full business cycle, it is unclear how likely it is that regulators would raise it above zero, and under what circumstances an increase would be triggered.

- Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity (TLAC). To further the policy goal of preventing taxpayer bailouts of large financial firms, the Fed issued a 2017 final rule implementing a TLAC requirement for U.S. G-SIBs and the U.S operations of foreign G-SIBs effective at the beginning of 2019.52 The rule requires G-SIBs to hold a minimum amount of capital and long-term debt at the holding company level so that these equity- and debt-holders can absorb losses and be "bailed in" in the event of the firm's insolvency.

In addition, the Fed tailored some of the Title I requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets in its implementation so that more stringent regulatory or compliance requirements were applied to advanced approaches banks or G-SIBs. For example, more stringent versions of the LCR, NSFR, and SCCL are all applied to advanced approaches banks than to banks with more than $50 billion in assets that are not advanced approaches banks. The SCCL as proposed also includes a third, most stringent, requirement that applies to only G-SIBs.

These requirements all determine how the largest banks have to fund all of their activities on a day-to-day basis. In that sense, these requirements arguably have a larger ongoing impact on banks' marginal cost of providing credit and other services than most of the Title I provisions discussed in the last section that impose only fixed compliance costs on banks.53

Other Provisions Using Size Thresholds. As noted in the previous section, two Title I requirements in the Dodd-Frank Act (company-run stress tests and risk committee requirements) were applied to banks with more than $10 billion rather than $50 billion in assets.

Size thresholds are also used in other regulations besides enhanced regulation. For example, by statute, only banks with more than $10 billion in assets are subject to the Durbin Amendment, which caps debit interchange fees, and CFPB supervision for consumer compliance. By regulation, there are additional compliance standards for the Volcker Rule for firms with more than $10 billion and $50 billion in assets.54 Executive compensation rules for financial firms pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act apply to only firms with more than $1 billion in assets by statute, with more stringent requirements for firms with more than $50 billion and $250 billion proposed by regulation.

Should Large Banks Be Regulated Differently Than Other Banks?

Fear of financial instability being triggered by the failure of large firms led the government to provide extraordinary assistance to prevent the failure of firms, such as Bear Stearns and AIG, during the financial crisis—hence the assertion that large financial firms were "too big to fail." In addition to fairness issues, economic theory suggests that expectations that a firm will not be allowed to fail create moral hazard—if the creditors and counterparties of a TBTF firm believe that the government will protect them from losses, they have less incentive to monitor the firm's riskiness because they are shielded from the negative consequences of those risks. If so, TBTF firms could have a funding advantage compared with other banks, which some call an implicit subsidy.55

According to Section 165 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the purpose of enhanced regulation is "to prevent or mitigate risks to the financial stability of the United States that could arise from the material financial distress or failure, or ongoing activities, of large, interconnected financial institutions." General prudential regulation applying to all banks is intended to be microprudential, focusing mainly on the individual institution's safety and soundness. Enhanced regulation is intended to be macroprudential, focusing mainly on the broader systemic risk posed by large institutions. Enhanced regulation is not necessarily mutually exclusive with other policy approaches to eliminating TBTF, although combining approaches could dilute any single approach's effectiveness. Different parts of the Dodd-Frank Act pursue several different approaches to eliminating TBTF.56

One rationale for enhanced prudential regulation holds that restraints on risk-taking at systemically important banks must be in place because eliminating such banks is infeasible or impractical, as is credibly eliminating all expectations of future government support. In this view, at least a few firms will likely come to dominate certain segments of the financial system due to economic incentives to grow larger, such as achieving economies of scale or increasing market power. Thus, breaking up large banks or eliminating all spillover effects would reduce the efficiency of the financial system. Eliminating TBTF through assurances that large firms would not be bailed out may lack credibility with market participants who witnessed the bailout of firms without a prior commitment to provide assistance in the previous crisis. If TBTF institutions cannot be eliminated, then enhanced regulation may be the most practical option for containing it.57

Few claim that prudential regulation can prevent all failures from occurring; regulated depository institutions have failed throughout U.S. history. Nor is a system without any failures necessarily a desirable one, since risk is inherent in all financial activities. However, enhanced regulation could potentially prevent large banks from taking greater risks due to moral hazard than their smaller counterparts. If successful, fewer large failures or market disruptions would occur, creating a more stable financial system and limiting potential taxpayer exposure through FDIC-insured losses.

Certain observers are skeptical of the ability of the enhanced prudential regulatory regime to successfully increase systemic stability and eliminate the TBTF problem. Critics cite the fact that most large banks have grown or remained the same size in dollar terms since the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act as evidence that TBTF has not been solved.

Some critics argue that in general, more prudential regulation may be counterproductive because it curbs the role of market discipline, resulting from such things as creditors monitoring and disincentivizing risky behavior. Enhanced prudential regulation may arguably have a limited effect on market discipline, however, because it only incrementally increases the regulation of large banks. Although regulation is intended to limit risky behavior, it may inadvertently increase systemic risk by causing greater correlation of losses across firms by encouraging all firms to engage in similar behavior. For example, one economist testified that "many financial sector experts believe that coordinated supervisory stress tests encourage a 'group think' approach to risk management that may increase the probability of a financial crisis."58

Other critics question the effectiveness of regulators to prevent the buildup of excessive risk, pointing out they were arguably unable or unwilling to prevent excessive risk-taking before and during the crisis, including in some cases by large banks they directly regulated.59 Although regulators have adapted in response to weaknesses raised by the crisis, the next crisis is likely to pose a novel set of problems. In addition, some critics fear that the enhanced regime is particularly vulnerable to "regulatory capture," the phenomenon in which the regulated exercise influence over their regulators to undermine the intended goals of regulation. Some have argued that large banks are "too complex to regulate," meaning regulators are incapable of identifying or understanding the risks inherent in complicated transactions and corporate structures. For example, the six largest BHCs had more than 1,000 subsidiaries each, and the two largest had more than 3,000 each in 2012. Further, their complexity has increased over time—only one BHC had more than 500 subsidiaries in 1990, and the share of assets held outside of depository subsidiaries has grown over time for the largest BHCs.60 Arguably, one of the benefits of enhanced regulation is that it provides opportunities (through living wills, for example) for the Fed and FSOC to better understand the risks institutions pose and the characteristics that could make certain banks systemically important.

Enhanced regulation could also fail to reduce systemic risk if problems at large firms during the crisis—such as excessive leverage, a sudden loss of liquidity, concentrated or undiversified losses, and investor uncertainty caused by opacity—were not caused by large firms per se, but were instead inherent in certain financial activities. If, in fact, they were representative of problems that firms of all sizes were experiencing, policy should directly treat these problems in a systematic and uniform way for all firms. In other words, prudential regulation could be applied to all firms operating in a given activity or area rather than just large banks, so arguments for and against these policy options do not apply only to their application to large banks. If systemic risk is caused mainly by activities, not large firms, then enhanced regulation could cause systemic risk to migrate away from large banks to other—potentially less regulated—firms, rather than being reduced.

Costs and Benefits of Enhanced Regulation

Specific components of the enhanced regulatory regime are arguably well targeted to mitigating some of the sources of systemic risk. Stress tests are intended to verify that large banks could survive another crisis, living wills are intended to explain to regulators how a failing bank can be safely wound down, counterparty credit limits are intended to limit spillover effects when firms fail, and liquidity requirements attempt to reduce reliance on funding sources that proved to be unreliable during the crisis.61 However, the degree to which these benefits are realized and the question of whether these benefits justify the cost the regulation may impose are contentious issues.

Quantifying the benefits of systemic risk provisions is difficult because the benefits of preventing another financial crisis are large, but the probability of another crisis at any given time is small. Furthermore, the ability to isolate the benefits of any particular provision is hindered by the fact that maintaining financial stability likely depends on the joint effects of a number of policies. Some of these provisions come from the Dodd-Frank Act, and others come from Basel III.

Comparing the magnitude of benefits to the costs they impose involves additional difficulty. Generally, enhanced prudential requirements impose costs on large banks.62 However, the extent to which those costs are passed on to customers potentially depends on a variety of economic factors, such as the degree of market competition and the price sensitivity of customers. Furthermore, from an economic net benefit perspective, the cost to large banks is less relevant than the overall effects on the costs and availability of credit. At least partly offsetting the higher costs of credit by banks subject to enhanced regulation would be relatively lower costs of capital for other firms.63 Some of these firms will be small banks, but some financial intermediation could also migrate from large banks to firms that are not regulated for safety and soundness. In that sense, even if a heightened prudential regime worked as planned, net benefits (i.e., reduction of overall systemic risk) could be smaller than anticipated.

The possibility that TBTF banks create market distortions creates additional considerations. Normally, higher costs imposed by regulation reduce economic efficiency, which must be balanced against the benefits they provide. However, if TBTF banks create moral hazard (a market failure that reduces efficiency), then regulatory costs may increase efficiency (from a societal perspective) by reducing risk-taking. Put differently, if there is a TBTF subsidy, then enhanced regulation may reduce that subsidy by mitigating large banks' lack of prudence.64

Regardless of whether the benefits of enhanced regulation outweigh the costs, there is also the question of whether the regime could be modified to reduce costs without a meaningful decline in benefits. In particular, there are areas of potential overlap among provisions that potentially raise costs. Capital planning requirements impose a de facto additional capital requirement in addition to existing capital requirements that apply to all banks. There are three separate liquidity requirements imposed on banks with more than $50 billion in assets (in addition to liquidity requirements that apply to all banks). Banks with more than $50 billion in assets are required to prepare both living wills and credit exposure reports, both of which require banks to report on their counterparties. Banks with more than $50 billion in assets must also participate in company-run and Fed-run stress tests.

Are All Banks with More Than $50 Billion Systemically Important?

Although systemic importance is not the only rationale provided for enhanced prudential regulation, it is the primary one.65 This section reviews data to attempt to determine whether all of the banks subject to enhanced regulation are systemically important. In particular, critics of the $50 billion threshold distinguish between regional banks (which tend to be at the lower end of the asset range and, it is claimed, have a traditional banking business model comparable to community banks) and Wall Street banks (a term applied to the largest, most complex organizations that tend to have significant nonbank financial activities).66 Definitively identifying banks that are systemically important is not easily accomplished, in part because potential causes and mechanisms through which a bank could disrupt the financial system and spread distress are numerous and not well understood in all cases.

Size is one factor that could make a bank systemically important.67 For example, a bank with a large amount of liabilities would inflict larger losses on counterparties in the event of default. In addition, because such a bank has larger funding needs, if it experienced liquidity problems and was forced to sell assets—often referred to as forced deleveraging—the large selloff could decrease certain asset prices and trigger fire sales. These are just two examples of how size can cause spillover effects that spread systemic risk more broadly throughout the financial system.

When examining banks' asset sizes, there is substantial variation across a number of bank characteristics, but none that clearly identify a cutoff point at which banks begin or cease to be systemically important. Among banks above the $50 billion threshold, organizations vary greatly in size, and except for the very largest, there are no natural breaking points that clearly distinguish one group of banks from another. The largest banks hold about 40 times as many assets as those near the threshold (as shown in Table 1), but beyond the largest handful of banks, size decreases fairly incrementally. Although not depicted in the table, the same difficulties are present when analyzing banks near but below the $50 billion threshold—asset size decreases incrementally, with no natural breaking points.

|

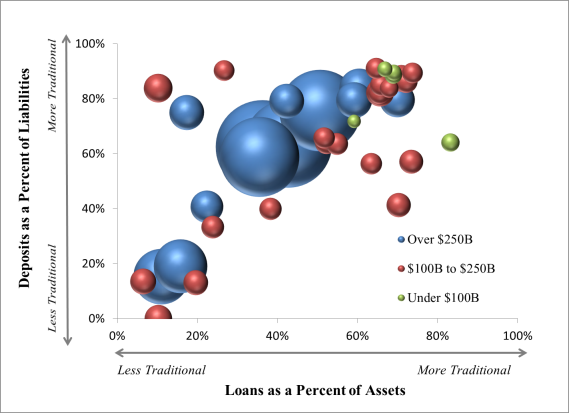

How Many Large Banks Are "Traditional" Banks? Sometimes it is posited that traditional banks do not require enhanced regulation because they are not complex. Figure 2 presents data on the traditional banking activities of lending and deposit-taking of banks with more than $50 billion in assets. It shows that there is significant variation across these banks—loans range from 6% to 73% of total assets and deposits range from 0% to 91% of total liabilities. Some banks with more than $250 billion (represented by blue circles) have high shares of loans and deposits (those in the top right portion of the figure), whereas others have low shares (those in the bottom left of the figure). Banks in the $100 billion to $250 billion asset range (red circles) vary greatly across loans and deposits. None of the banks in the $50 billion to $100 billion range (green circles) are highly nontraditional on both measures, but some are less traditional than a few of the largest banks. These variations suggest that $50 billion is not necessarily the best threshold if the goal is to apply enhanced regulation to only nontraditional institutions. However, it also suggests that regional banks with traditional commercial banking businesses cannot necessarily be identified by simply establishing a new, higher asset threshold, as certain smaller banks have relatively low shares of loans and deposits compared to certain larger banks with high shares. Another way to define traditional banking is by legal charter. Fed data indicate that 33 out of 37 bank holding companies with more than $50 billion in assets at the end of 2015 were registered as financial holding companies, which allow them to own subsidiaries that participate in a wider range of nonbank financial activities. By this measure, arguably four banks with over $50 billion in assets are engaged solely in traditional banking. 68 |

Size is not the only potential characteristic through which a bank could disrupt financial stability.69 Regulators have developed certain methodologies to empirically measure systemic importance. A prominent example is the "method 1 systemic score" used to determine which institutions are designated as G-SIBs.70 The scoring methodology uses 12 indicators across five categories to calculate a bank's score. In addition to size, these categories are as follows:

- Interconnectedness. How interconnected one institution is to other financial companies could lead to contagion effects if its default results in destabilizing losses at other institutions or markets. Interconnectedness is measured in method 1 by a bank's intra-financial system assets and liabilities.

- Substitutability. This metric determines whether other banks or financial institutions could perform the critical functions currently performed by the bank in question should it fail. Substitutability is measured in method 1 by a bank's assets under custody, payments activity, and underwriting.

- Complexity. Banks differ substantially across their business models, and certain activities could make them more or less risky and, in the event they experienced distress or failure, more or less likely to destabilize the financial system.71 Many large bank organizations are engaged in numerous lines of business, including securities trading, insurance, swap dealing, custodial services, credit card issuance, merchant banking, and clearing and settlement services, among others.72 These activities may not necessarily be systemically risky (diversifying business lines could arguably make an individual institution less risky), but they may warrant additional regulatory scrutiny because they are outside the traditional prudential regulatory model for commercial banking and increase the number of markets and activities through which an institution could trigger a systemic event or spread systemic risk. Complexity is measured in method 1 by over the counter (OTC) derivatives, level 3 (i.e., illiquid) assets, and trading and available for sale (AFS) securities.73

- Cross-Jurisdiction Activity. Measured by cross-jurisdictional claims and liabilities, this metric captures the degree to which the bank operates internationally.

The score is a weighted average of each institution's share of a global aggregate of each of the 12 indicators, expressed in basis points. Any institution with a score of more than 130 is determined to be systemically important to the global financial system.74 One drawback to using this indicator is that it is intended to measure global systemic importance, whereas the enhanced prudential regime is intended to apply to domestic systemically important banks. For example, cross-jurisdictional metrics may be more pertinent to global importance than domestic importance. Nevertheless, banks with low scores arguably may not be domestically systemically important.

Examining the U.S. banks with more than $50 billion in assets reveals a wide range of scores, as seen in Table 2. Eight banks exceed the 130 threshold. The rest are not close to this number, and half have a score of less than 15, including all of the banks with less than $100 billion in assets. Some relatively large banks have low scores. For example, Capital One had $334 billion in assets at the end of 2015, but a score of 20. Conversely, State Street, the smallest bank by asset size to be designated a G-SIB, had assets of $224 billion and a score of 148. Such scoring may suggest that size alone is not well correlated with systemic importance, and may also support assertions that the $50 billion threshold is set too low.

|

Institution Name |

Total Assets |

Score |

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

$2,352 |

464 |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

$1,731 |

430 |

|

Bank Of America Corporation |

$2,147 |

345 |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

$861 |

252 |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

$1,788 |

250 |

|

Morgan Stanley |

$787 |

212 |

|

Bank Of New York Mellon Corp |

$394 |

160 |

|

State Street Corporation |

$245 |

148 |

|

Northern Trust Corporation |

$117 |

56 |

|

HSBC North America Holdings Inc. |

$272 |

44 |

|

U.S. Bancorp |

$422 |

41 |

|

PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. |

$359 |

34 |

|

Charles Schwab Corporation |

$184 |

25 |

|

Deutsche Bank Trust Corporation |

$54 |

23 |

|

Capital One Financial Corporation |

$334 |

20 |

|

TD Group Us Holdings Llc |

$267 |

18 |

|

American Express Company |

$161 |

15 |

|

BB&T Corporation |

$210 |

14 |

|

Suntrust Banks, Inc. |

$191 |

14 |

|

BMO Financial Corp. |

$126 |

13 |

|

Ally Financial Inc. |

$159 |

13 |

|

MUFG Americas Holdings Corp. |

$116 |

11 |

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

$141 |

11 |

|

Santander Holdings Usa, Inc. |

$128 |

10 |

|

M&T Bank Corporation |

$123 |

7 |

|

Keycorp |

$95 |

7 |

|

Discover Financial Services |

$87 |

7 |

|

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated |

$71 |

7 |

|

Regions Financial Corporation |

$126 |

7 |

|

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. |

$139 |

7 |

|

BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc. |

$90 |

5 |

|

Comerica Incorporated |

$72 |

5 |

|

Bancwest Corporation |

$95 |

4 |

|

Zions Bancorporation |

$60 |

3 |

Source: CRS calculations, using Federal Reserve data reported on Form Y-9C.

Notes: Charles Schwab is a thrift holding company, and is not currently subject to enhanced prudential regulation. Four intermediate holding companies listed in Tables 1 and 2 are not listed here, because they were not required to participate in G-SIB scoring in 2015.

However, given uncertainty about the relative importance to financial stability of the various indicators that comprise the score, it is useful to observe whether any banks play an outsized role in any individual activity that makes up the score. Table 3 illustrates that some banks with low aggregate scores nevertheless have individual indicators that are at least three times the median value for this group of banks. For example, five banks with aggregate scores under 15 have three times the median value for the underwriting indicator. Similarly, there are low-aggregate-scoring banks with high concentrations in payments, level 3 assets, and cross-jurisdictional indicators. Overall, 18 banks have three times the median value for multiple indicators, and 4 banks have three times the median for one indicator. Two of the four banks that have high values for one indicator have less than $100 billion in total assets. If the G-SIB indicators accurately correlate with systemic riskiness, it is unlikely that the 12 banks with values below three times the median for all of the indicators are systemically important. If a higher multiple of the median value is chosen to identify banks that play outsized roles in the activities shown in Table 3, fewer banks would qualify. For example, if 10 times the median value were used as a threshold, then 11 banks would meet that threshold in multiple categories, and 3 banks would meet it in one category.

Table 3. BHCs with Three Times the Median Value in Individual Indicators

(cells marked with "X" indicate value at least 3x the median; see key in notes for full indicator names)

|

Institution Name |

TE |

IA |

IL |

SO |

P |

AUC |

U |

OD |

TAS |

L3A |

XJC |

XJL |

Score |

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

464 |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

430 |

|

Bank Of America Corporation |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

345 |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

252 |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

250 |

|

Morgan Stanley |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

212 |

|

Bank Of New York Mellon Corp. |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

160 |

|

State Street Corporation |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

148 |

|

Northern Trust Corporation |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

56 |

|

HSBC North America Holdings Inc. |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

44 |

|

U.S. Bancorp |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

41 |

|

PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

34 |

|

Charles Schwab Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

25 |

|

Deutsche Bank Trust Corporation |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

|

Capital One Financial Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

TD Group Us Holdings Llc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

18 |

|

American Express Company |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

15 |

|

BB&T Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

Suntrust Banks, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

14 |

|

BMO Financial Corp. |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

13 |

|

Ally Financial Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

|

MUFG Americas Holdings Corp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

Santander Holdings Usa, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

M&T Bank Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

Keycorp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

Discover Financial Services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

7 |

|

Regions Financial Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

Comerica Incorporated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

Bancwest Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

Zions Bancorporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

Source: CRS calculation, based on Federal Reserve Y-15 data.

Notes: Four intermediate holding companies listed in Tables 1 and 2 are not listed here, because they were not required to submit data for G-SIB scoring in 2015. Charles Schwab is a thrift holding company, and is not currently subject to enhanced prudential regulation. Four intermediate holding companies listed in Tables 1 and 2 are not listed here, because they were not required to participate in G-SIB scoring in 2015. Key: TE= Total Exposures; IA= Intra-Financial System Assets; IL= Intra-Financial System Liabilities; SO= Securities Outstanding; P= Payments; AUC = Assets Under Custody; U= Underwriting; OD= OTC Derivatives; TAS = Trading and AFS Securities; L3A = Level 3 Assets; XJC= Cross-Jurisdictional Claims; XJL = Cross-Jurisdictional Liabilities

Legislative Options

Fed officials,75 former Representative Barney Frank,76 and critics of the Dodd-Frank Act77 have called for a higher threshold or for replacing the threshold with an alternative method, but no consensus has emerged over what should take its place. Others have called for eliminating enhanced regulation. The Treasury Department's June 2017 report on regulatory relief for banks (hereafter, the Treasury report) "recommends that Congress amend the $50 billion threshold under Section 165 of Dodd Frank for the application of enhanced prudential standards to more appropriately tailor these standards to the risk profile of bank holding companies," but does not contain a specific proposal for how it should be altered.78

This section reviews proposals to alter which banks are subject to enhanced regulation. It does not cover legislative proposals that would revise or eliminate specific provisions of enhanced regulation, such as stress tests or living wills.

Status Quo

If Congress does not act, the Fed (at the recommendation of FSOC) has discretion to maintain the existing threshold at $50 billion indefinitely, or raise it at any time. If the Fed chooses to raise it, however, it can do so only for certain enhanced regulatory provisions. Statute does not allow the Fed to change the $50 billion threshold for capital planning, liquidity requirements, Fed-run stress tests, risk management requirements, certain assessments, and the requirements listed above in the section entitled "Provisions That Are Triggered in Response to Financial Stability Concerns." However, statute allows the Fed to raise the threshold for resolution plans, credit exposure reports,79 and 25% concentration limits,80 as well as for some discretionary authority to impose additional requirements that the Fed has not exercised to date. Statute also requires the Fed to maintain a $10 billion threshold for risk committee and company-run stress test requirements.

The Fed also has the authority to tailor the application of enhanced regulation for individual banks or groups of banks, increasing the stringency of regulation based on a number of "risk-related factors." The Fed has already tailored the application of a number of prudential requirements, as discussed in the section above entitled "What Other Size-Based Requirements Exist in Bank Regulation?"

Eliminate the Threshold

Another option is to regulate all banks similarly, regardless of size. This approach is compatible with eliminating the enhanced regulatory requirements or subjecting all banks to those requirements. An example of the former is H.R. 2094 in the 114th Congress, which would have repealed Title I (and Title II) of the Dodd-Frank Act. Were Congress to repeal Title I, the Fed would still have broad authority to apply prudential standards differently based on size or other factors. For example, stress tests for large banks predated the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act requirements.

The efficacy of enhanced regulation for a subset of banks depends on whether one believes that size (or another attribute well correlated with size) is a unique cause of systemic risk. If one believes that systemic risk stems primarily from specific bank activities or attributes, such as bank runs, then there is little benefit from basing regulations on size.81 In that case, legislation could apply specific enhanced regulatory provisions to all or no banks. Alternatively, if one believes that some subset of banks poses unique risks, then a threshold-based regime can address those risks, in its current state or under one of the below proposals to modify it.

Modify Who Is Subject to Enhanced Regulation

A number of proposals would modify who is subject to the enhanced regulatory regime. This could be done by raising the threshold's asset value, using a different measure than total assets for a threshold, switching from a threshold to a case-by-case designation process, or some combination of proposals.

Proposals to modify who is subject to enhanced regulation can be evaluated by comparing costs and benefits. These proposals are motivated by concerns that some of the banks with more than $50 billion do not pose systemic risk (discussed in the section above entitled "Are All Banks with More Than $50 Billion Systemically Important?") and do not benefit from a perception that they are TBTF that results in excessive risk taking. If a bank does not pose systemic risk or is not perceived as TBTF, the main benefit of enhanced regulation is not present, "and it is subjected to unnecessary costs without any offsetting benefits."82

Although systemic risk mitigation is the main purpose of enhanced regulation, there are other potential benefits. First, enhanced regulation could reduce the likelihood that a bank's failure would result in taxpayer exposure to FDIC insurance losses or due to "bailouts," as the government lost money on TARP investments following the financial crisis in some midsized institutions (such as Ally Financial and CIT Group, which had between $50 billion and $250 billion in assets) although they were not viewed as systemically important.83 Second, a midsized bank that did not pose systemic risk could nevertheless potentially result in localized or sectoral disruptions to the availability of credit and the provision of financial services.84 Finally, some have argued that some enhanced prudential requirements (e.g., risk committees, chief risk officers, company-run stress tests) represent good risk management practices that any well-managed firm should apply in the interest of shareholders.85

There is also concern that enhanced regulation poses disproportionately greater compliance costs on banks closer to the threshold than the largest banks. This may be the case because of the relatively fixed compliance costs associated with certain elements of the enhanced regime, such as living wills, risk management, and stress tests. In contrast, some elements of the regime have already been tailored in an effort by the Fed to reduce the costs for smaller banks.

One second-order benefit of setting the threshold relatively low is that it may avoid causing moral hazard. According to former Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo, "by setting the threshold for these standards at firms with assets of at least $50 billion, well below the level that anyone would believe describes a TBTF firm, Congress has avoided the creation of a de facto list of TBTF firms."86 Proposals to decrease the number of firms subject to enhanced regulation risk creating the perception of a list of TBTF firms.

Raise the Asset Value

Congress could decide to raise the numeric threshold to a dollar amount above $50 billion. In 2014, former Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo suggested $100 billion.87 Former Representative Barney Frank reportedly suggested raising the threshold to $125 billion and indexing it.88 National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn reportedly suggested raising it to at least $200 billion (or replacing it).89 Higher thresholds have also been proposed, although more often using some hybrid method (see below). Any threshold above $225 billion would currently not capture all of the G-SIBs.

If Congress chose to raise the threshold, it could do so only in Section 165, throughout Title I, or throughout the Dodd-Frank Act (see Appendix for more details). Alternatively, Congress could provide the Fed with broader discretion to raise the $50 billion threshold for more or all of the requirements found in the Dodd-Frank Act, instead of the current subset enumerated above. It would then depend on the Fed to decide which, if any, requirements merited a higher threshold.

If policymakers believe that bank size is in itself an important determinant of systemic riskiness, then a numerical threshold is the best approach, although policymakers may debate the most appropriate number. Consensus on a revised threshold is hindered by, among other things, the lack of a natural breakpoint in the data. Just as there are banks just above and below the $50 billion threshold, there are currently banks just above and below $100 billion, $150 billion, $200 billion, and $225 billion in assets. In addition, the total assets of individual banks naturally fluctuate over time, due in part to factors such as inflation.

Even if size is not the only determinant of systemic importance, size is a much simpler and more transparent metric than some alternatives discussed below. As a practical matter, if size is well correlated with systemic importance—so that policymakers could choose a threshold that did not apply enhanced regulation to too many firms above the threshold that are not systemically important and did not leave out too many firms below the threshold that are not systemically important—it could serve as a good proxy that was easy and inexpensive to administer.

Critics of size-based thresholds are skeptical of this criterion. The presence of banks just below the threshold could distort behavior and reduce economic efficiency if banks take actions solely for the purpose of staying under the threshold. Acting Comptroller of the Currency Keith Noreika argues that "for midsize institutions, the threshold approach … represents a barrier to growth because, above that line, compliance costs rise so dramatically. The effect is to discourage competition with the largest institutions."90

In addition, many economists believe that the economic problem of "too big to fail" is actually a problem of firms that are too complex or too interdependent to fail. Size correlates with complexity and interdependence, but not perfectly, as discussed in the section above entitled "Are All Banks with More Than $50 Billion Systemically Important?"91 If size is not perfectly correlated with systemic risk, it follows that a size threshold is unlikely to successfully capture all those—and only those—firms that are systemically important. A size threshold will capture some firms that are not systemically important if set too low, or leave out some firms that are systemically important if set too high.

Replace with a Different Measure

If size is not well correlated with systemic risk or other policy goals, then Congress could consider replacing it with a numerical measure that is better correlated. This option could retain the automatic nature of the current threshold, or, as discussed in the next section, defer to regulators' judgment. An automatic alternative threshold could potentially be relatively simple or complex. Crafting a detailed, complex threshold likely involves the type of technical decisionmaking that Congress would delegate the Fed or FSOC to work out in subsequent rulemaking. The formula based on 12 metrics (with different relative weights) to determine which firms are G-SIBs is an example of a more complex numerical indicator (discussed in the section above entitled "Are All Banks with More Than $50 Billion Systemically Important?"). Notably, the eight G-SIBs under this metric are not the eight largest banks (they are the six largest, plus two others). Although the value is set to designate eight U.S. banks with the highest rating currently for G-SIB purposes, it could be set lower to potentially capture more than the current eight for domestic purposes.92

Replace with a Designation Process

If no quantitative measure lines up well with systemic importance, another legislative option would be to replace the numerical threshold with a process to designate banks as "systemically important" on a case-by-case basis. Congress could consider whether or not to include restrictions such as a minimum size, below which designation would not be allowed. Notably, the Fed has already voluntarily identified large banks as systemically important for supervisory—as opposed to rulemaking—purposes. Currently, 12 banks (8 domestic G-SIBs and 4 foreign G-SIBs operating in the United States) are supervised by the Fed's Large Institution Supervision Coordinating Committee.93 According to Tarullo, "in determining which banking organizations belong in the LISCC portfolio, the Federal Reserve has focused on the risks to the financial system posed by individual firms—size has not been the dispositive factor. For example, three large banking organizations are not in that portfolio, even though they have larger balance sheets than the processing- and custody-focused bank holding companies that are in the LISCC portfolio."94 The Fed has also classified another set of banks as "large and complex."95