Overview

The 115th Congress and the Trump Administration are reviewing existing U.S. policies and programs in sub-Saharan Africa (henceforth, "Africa") as they establish their budgetary and policy priorities toward the region while also responding to emerging crises. Key issues for Congress include the authorization and appropriation of U.S. aid to Africa, the authorization and appropriation of funds for U.S. military activities on the continent, and oversight of U.S. programs and policies. In support of congressional deliberations, this report provides background on select issues related to Africa and U.S. policy in the format of frequently asked questions.

Much of Africa experienced rapid economic growth starting in the early 2000s, which spurred middle class expansion. Growth in many countries has slowed since 2015, however, and most African countries still face significant development challenges. These include unmet needs for health, education, and other social services—particularly for large youth populations—as well as climate and environmental shocks. Among the factors that hinder investment and economic growth are poor governance and infrastructure, poverty and low domestic demand, a lack of skilled labor, limited access to inputs and capital, political instability, and insecurity.

Since the early 1990s, nearly all African countries have transitioned from military or single-party rule to at least nominally multiparty political systems in which elections are held regularly. Nonetheless, the development of accountable, functional democratic institutions remains limited in many countries. State institutions often lack sufficient human and financial capacities and/or are beset by problems such as corruption and mismanagement. Enhancing democracy, the rule of law, and respect for human rights in the region have long been U.S. policy priorities, often as mandated by Congress. U.S. efforts to promote democracy, human rights, and economic development on the continent have been pursued through the use of diplomacy, foreign aid or restrictions on assistance, preferential tariff treatment, or the sanctioning or prosecution of human rights violators, often under close congressional oversight.

Armed conflict and instability continue to threaten regional security, impede development, and contribute to widespread human suffering and humanitarian crises. Long-running civil conflicts continue to affect parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia, and Sudan, while newer conflicts have unfolded in recent years in the Lake Chad Basin, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, and South Sudan. In a number of African countries, porous borders, weak state institutions, and corruption have created permissive environments for transnational threats, including terrorism, illicit trafficking, and maritime piracy. Three African countries—South Sudan, Nigeria, and Somalia—face famine or a credible risk of famine in 2017; in each case, security-related restrictions have hindered humanitarian access to the affected populations.

The Obama Administration pursued several global development initiatives that sought to benefit Africa, as well as a number of Africa-specific initiatives and major programs. In 2012, the Obama Administration released a policy document entitled U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa, which prioritized as U.S. goals the strengthening of democratic institutions; the expansion of economic growth, trade, and investment; the advancement of peace and security; and the promotion of opportunity and development. The document did not represent a dramatic departure from traditional U.S. policy goals in Africa, but it signaled a high-level effort to promote an integrated, comprehensive U.S. approach toward sub-Saharan Africa. Analysts continue to debate whether that Strategy reflected an appropriate mix and ranking of priorities, and the degree to which the Obama Administration's actions reflected its stated goals.

Trump Administration views on many U.S.-Africa policy issues have not been publicly stated. In his first weeks in office, President Trump called the presidents of several key African states, including South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya. Nationals of two African countries, Somalia and Sudan, are subject to a revised Executive Order on immigration signed by President Trump in March 2017 that temporarily suspends, with some exceptions, entry into the United States by nationals of six countries identified as presenting a security threat. Other Administration priorities remain unspecified, and may be contingent on forthcoming senior official appointments.

Economic and Development Challenges

What are Africa's notable development challenges?

Starting in the early 2000s, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa exhibited high rates of annual economic growth, albeit starting from a low base by global standards. These trends spurred middle class expansion in some countries, a rapid spread in access to digital communications, and infrastructure construction. Health indicators improved, as did primary school enrollment rates.1 Poverty alleviation was more limited than in other developing-country regions with similar growth rates, however, and many African economies continue to face diverse structural challenges. Most African countries failed to achieve most of the U.N. Millennium Development Goals by the deadline of 2015.

Many countries have confronted economic headwinds since 2015. African countries that rely on raw commodity exports, for instance, have suffered declining growth due to generally weak global commodity prices, even as low oil prices have aided countries that are net energy importers. Notably, Africa's largest economy, Nigeria, a major oil exporter, experienced a recession in 2016—its worst economic contraction since 1987, according to World Bank data.2 A previous trend in which African governments sought to access financing through international bond offerings has slowed in the face of low growth and increasing public deficits in several countries. Some economic challenges are weather-related: since 2015, countries in Southern Africa and the Horn of Africa have faced food security crises and low growth due to drought associated with the El Niño weather phenomenon.

Economic growth rates and the quality of economic policy performance vary widely among countries in the region, and generalizations about trends in the region often do not hold true for specific countries. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in late 2016 described the region's outlook as one of "multispeed growth," with growth projections in commodity exporting countries revised downward to reflect weak global commodity prices but with continued robust growth expected in the region's non-resource exporters.3 In countries that have experienced growth, rising national incomes have often not been equally distributed or inclusive, and in many countries the informal sector remains large and unemployment rates high. In addition, growth has not always been effectively marshalled to address the region's development challenges.4

Income increases have often not been as significant in real terms as growth rates suggest. For example, one sub-Saharan African country (the Seychelles) qualifies as "high income" as defined by the World Bank; seven more (Angola, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Mauritius, Namibia, and South Africa) qualify as "upper-middle-income" economies—although wealth is unequally distributed and welfare indicators remain low in several of these countries. All other countries in the region are either "lower-middle-income" or "low-income."5

What major human development challenges does Africa face?

On a per-capita basis and by other measures, Africa remains among the poorest global regions. According to United Nations (U.N.) data, as of 2015, 41% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lived on less than $1.25 per day.6 Africa was also the most malnourished region in the world, with an under-nourishment prevalence rate of 23%.7 Many countries lack the institutional capacity to provide effective public services (e.g., healthcare and education) or public goods (e.g., electricity and transportation infrastructure) considered necessary for sustained growth and human development. Corruption and insecurity hinder improvements in many countries.

Consequently, despite considerable progress in certain areas—particularly related to combatting communicable disease, reducing infant and child mortality, and improving life expectancy—the region continues to face significant human development challenges. Africa's maternal mortality rates remain the highest of any region in the world; in 2015, the region accounted for almost two-thirds of all maternal deaths globally.8 Africa's child mortality and stunted growth prevalence rates are also the highest in the world, as are rates of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.9 Ensuring access to improved drinking water and sanitation facilities continues to pose a steep challenge: the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that in 2012, 45% of all deaths due to exposure to unsafe water (largely attributable to infectious disease) occurred in Africa.10

The provision of quality education is another major challenge facing the region, notwithstanding marked gains in primary school enrollment and youth literacy rates across the continent. The U.N. estimates that one-third of children between the ages of 12 and 14 and more than half of children between the ages of 15 and 17 in Africa are not in school.11 One-third of those enrolled fail to complete primary education.12 Literacy rates continue to lag behind those of other regions: in 2015, the average youth literacy rate in sub-Saharan African countries for which data were available was just under 70%, as compared to an average of 88% in other developing countries.13 African girls continue to be disproportionately excluded from school, despite considerable progress. Africa's gap between male and female literacy is the highest of any region.14

Africa also has a proportionally large youth population. According to U.S. Census estimates, in 2016, 60% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa was aged 24 or younger, and the proportion was significantly higher in some sub-regions.15 While youthful populations hold significant socioeconomic promise, realizing their potential presents governments with profound challenges related to the provision of education, job creation, and socio-political enfranchisement. The risk to governments that do not meet such challenges is high. In many countries, youth are a major source of dissent and protest and, in some cases, instability. Youth recruitment into armed groups has contributed to the persistence of armed conflicts throughout the region.

|

|

Source: CRS graphic created by Calvin DeSouza using data from ESRI. Notes: This map is a general reference map. Boundaries may not be authoritative. Mauritius is not shown. |

Trade, Investment, and Economic Cooperation

What is the nature and focus of U.S.-Africa trade and economic relations?

As of 2016, the United States ran a goods trade deficit ($-6.5 billion) with sub-Saharan Africa, importing $20.1 billion worth of goods, and exporting $13.6 billion.16 Major U.S. exports to Africa are diverse. They include machinery, vehicles, refined fuel products, aircraft, and wheat. Oil constitutes the largest share of U.S. imports from Africa, although U.S. energy imports from Africa have declined dramatically in both value and volume as U.S. domestic energy production has grown and global energy prices have declined. From 2011 to 2016, U.S. crude oil imports from the region fell from $56.4 billion to $7.2 billion. Key nonenergy U.S. imports include metals, vehicles, and cocoa.

Nigeria and South Africa have the continent's largest economies and are sub-Saharan Africa's largest U.S. trade partners, accounting for roughly half of all such trade. Nigeria has historically been a major oil exporter to the United States.17 The stock of U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region is concentrated in a few countries, including Mauritius ($6.9 billion in 2015, the last year for which data are available), South Africa ($5.6 billion), Nigeria ($5.5 billion), and Equatorial Guinea ($4.2 billion). The stock of sub-Saharan African FDI in the United States is relatively small, totaling less than $1 billion, with Liberia ($500 million), Mauritius ($385 million), and Angola ($207 million) accounting for the bulk of such activity.

U.S. trade and investment policy toward Africa is focused on encouraging economic growth and development through trade within the region, with the United States, and internationally. The U.S. government also seeks to facilitate U.S. firms' access to future opportunities for trade and investment in Africa. A growing number of Members of Congress have supported expanded efforts to pursue such goals, and multiple committees have held hearings addressing these topics in recent years.

Africa is a key supplier of some U.S. natural resource imports, such as oil, minerals, and metals, and improving economic and political climates in some African countries have led to increasing interest in the region as a destination for U.S. goods, services, and investment. Despite these trends, many U.S. businesses remain skeptical of the region's investment and trade potential and focus their investment interest in regions thought to offer more opportunity and less risk. Many avoid engaging in business in Africa due to the daunting economic governance challenges that a number of African countries continue to confront, the relative difficulty of doing business in many African countries, and in some instances, political instability.18 To some extent, the lack of U.S. business interest may also stem from lack of knowledge about opportunities, challenges, and differences among African countries and, in some cases, from negative perceptions of the region.

What factors hinder business interest in the region?

Despite impressive economic growth in many African countries in recent years, several factors continue to hamper the region's business climate and economic potential. Key factors include the following:

- Infrastructure. Africa has poor electrical, transportation, and maritime infrastructure. Roads, when present, are often unpaved and poorly maintained, rail networks are unreliable and limited, and ports are inefficient and lack capacity. These problems increase production and transportation costs, harm product quality, and lead to shipment delays.

- Market size. Low per capita incomes across much of Africa limit domestic demand. Efforts to deepen regional and sub-regional integration and thereby boost market size and diversity vary considerably among regions and in their relative effectiveness. As a result, most foreign business interest in sub-Saharan Africa continues to focus on the region's major economies, such as South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya.

- Labor force. Much of the region suffers from a scarcity of skilled labor owing to under-investment in education. Further, in many countries, low-skill agriculture production (including subsistence agriculture) remains the principal form of employment; by some estimates, farming provides up to 60% of all jobs on the continent.19

- Economic diversification and value chain enhancement. Many economies in Africa remain highly dependent on labor-intensive, small-scale, and often low-profit and highly variable rain-fed agricultural production, or on exports of unrefined commodities, especially in the energy, mining, and agricultural sectors. Many countries have also failed to pursue value-added processing and production. This has often limited growth potential, inhibited business sector development, constrained market size and complexity, and undermined the growth of skilled work forces. The result has been unrealized potential income earnings and low levels of competitiveness vis-à-vis other world regions.

- Access to inputs. Capital markets and markets for other inputs, such as spare parts and manufacturing supplies, are limited compared with other regions. Such shortfalls increase production costs and inhibit growth of integrated manufacturing sectors and cross-sectoral linkages.

- Regulatory and legal environments. Governments have often provided an inadequate enabling environment for private sector activity, including through failing to enforce contracts or protect property rights. Corruption also remains a challenge. Inefficient cross-border trade procedures and a lack of trade regulation and tariff harmonization also often impose high costs on import and export flows, both within Africa and with other regions.

- Political instability and security. Many countries continue to be beset by political instability and conflict, undermining business confidence in the region.

What programs support expanded U.S.-Africa trade and economic relations?

President Obama's Africa Strategy emphasized the need to improve

- legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks to enable trade and investment;

- economic governance and regional economic and trade integration; and

- African capacity to access and participate in global markets.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, see below) has been the cornerstone of U.S.-Africa trade policy since it was established by Congress in 2000. Working with Congress to secure a long and timely reauthorization of AGOA in 2015 was a key focus of the Obama Administration. To advance its goals for African trade and investment, the Obama Administration also launched the Doing Business in Africa campaign and the Trade Africa Initiative. Efforts initiated prior to the Obama presidency include three African trade hubs established by the George W. Bush Administration that work to increase African producers' export competitiveness and increase the use of AGOA. The Obama Administration sought to transform these hubs into two-way U.S.-Africa trade and investment centers, in addition to their prior mandates to increase intraregional trade and economic integration and exports to the United States under AGOA, among other ends. This was done to facilitate U.S. trade and investment in the region and support broader U.S.-African business linkages.20 Several U.S. agencies have also provided trade capacity building (TCB) programs in Africa not directly related to AGOA.

|

Background on Trade Capacity Building Trade capacity building (TCB)—which the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) also calls trade and investment capacity building (TICB)—refers to a broad range of activities designed to promote and expand countries' and regions' participation in international trade. Core TCB activities help build or strengthen physical, human, and institutional capacities to help recipient countries facilitate the flow of goods and services across borders. Among other ends, they also seek to help countries participate in trade negotiations; implement trade agreements; comply with food safety, manufacturing, and other standards; join and comply with World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements; and increase economic responsiveness to trade opportunities through business and trade training.21 Such aid may complement, overlap with, or be tied to other types of economic growth aid, but is generally separate, and often comprises a relatively small portion of overall economic growth assistance.22 Agency TCB funding allocations vary by year, but USAID is generally the lead funding agency of TCB projects. Some aspects of Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC, see below) Compacts, including infrastructure, are also considered TCB assistance. Other agencies providing TCB include the Departments of State, Agriculture, Commerce, Justice, and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency.23 |

Other U.S. trade and investment policy tools in place with African countries include Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs)—intergovernmental forums for dialogue on trade and investment issues—and bilateral investment treaties, which advance rules to facilitate and protect foreign investment. The United States has a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Morocco, in North Africa, but there are no existing U.S. FTAs with sub-Saharan African countries. Negotiations on a potential U.S.-Southern African Customs Union (SACU) FTA were initiated in 2003 but suspended in 2006 due to divergent views on the agreement's scope.

In September 2016, the Obama Administration released a "Beyond AGOA" report examining potential next steps to move U.S. trade and investment policy toward more reciprocal agreements with the region. A key challenge identified in the report was economic diversity among African countries and varying levels of interest and capacity to undertake FTA commitments, which typically include comprehensive tariff coverage as well as protections for intellectual property rights, investment, worker rights, and the environment, among others.24 The report also highlighted the need to ensure that U.S. trade policy in the region continues to support ongoing regional integration efforts and to promote diversified and greater value-added production and broader economic reforms. Determining whether and how to advance U.S. trade relations beyond unilateral trade preferences, particularly with the larger sub-Saharan African economies, is an ongoing policy question for the Trump Administration and the 115th Congress.

What is AGOA? What is the AGOA Forum?25

AGOA (Title I, P.L. 106-200, as amended) is a nonreciprocal U.S. trade preference program that provides duty-free tariff treatment on certain imports from eligible sub-Saharan African countries. Congress first passed AGOA in 2000 as part of an ongoing U.S. effort to promote African development, deepen economic integration within the region, and strengthen U.S.-African trade and investment ties. The Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-27) extended AGOA's authorization for an unprecedented 10 years to September 2025.

U.S. trade with Africa has fluctuated considerably since 2001, the first full year AGOA was in effect. Trade in energy products dominates U.S. trade flows with the region and accounts for much of the variation—U.S. energy imports rose from $15 billion in 2001 to $72 billion in 2008 and have since declined to $8 billion in 2016.26 Most analysts, however, focus on AGOA and its relation to nonenergy trade as a potential catalyst for economic development in Africa. U.S. imports of such products from the region nearly doubled between 2001 and 2016 ($7 billion to $12 billion).

Total U.S. imports under AGOA were $10.6 billion in 2016, but a handful of countries and products account for the bulk of these imports.27 Despite the decline in recent years, energy products, mostly crude oil, remain the top import under AGOA (62% of the total in 2016). The remaining $4.2 billion in nonenergy imports under AGOA comes largely from South Africa ($2.8 billion), which exports the most diverse range of products, including motor vehicles, under the preference program. Kenya, Lesotho, and Mauritius export primarily apparel products under AGOA, and together account for nearly $900 million of U.S. nonenergy AGOA imports. The remaining 34 AGOA beneficiary countries together accounted for 10% or $428 million of U.S. nonenergy imports under the program in 2016.

AGOA also requires the President, in consultation with Congress and AGOA beneficiary governments, to hold an annual U.S.-Africa Trade and Economic Cooperation Forum.28 The original AGOA legislation states that the purpose of the Forum, which is held in alternate years in the United States and Africa, is to "discuss expanding [U.S.-Africa] trade and investment relations" and to encourage "joint ventures between small and large businesses," as well as to foster the broader goals of AGOA. Civil society and private sector events are typically held in conjunction with the Forum.29 The 15th Forum was held in September 2016 in Washington, DC. In addition, AGOA directs the President to provide U.S. government technical and trade capacity building (TCB) assistance aimed at developing stronger trade linkages between U.S. and African firms and promoting AGOA beneficiary countries' abilities to engage in international trade.

What are the key provisions of AGOA's 2015 reauthorization?

AGOA has been amended six times since its initial passage. The June 2015 reauthorization included an extension of two critical components: the apparel provision, which allows for duty-free treatment of eligible apparel items, and the third-country fabric provision, which enables African firms to assemble textiles and apparel products with fabric from other regions and export them to the United States duty-free. Other key provisions of the reauthorization include the following:

- Rules of origin. Determine if a product originates from a beneficiary AGOA country and is eligible for duty-free treatment. The origin rules are broadened to allow for greater cumulation (i.e., use of inputs from peer AGOA countries) to promote value-added processing across beneficiary countries.

- Country eligibility reviews. Codifies the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) annual review process on AGOA country compliance with certain eligibility criteria. The process includes an annual public comment period and hearing, a public petition process for input on eligibility compliance, and an out-of-cycle review process. It also required an out-of-cycle review of South Africa's AGOA eligibility. South Africa ultimately maintained its AGOA eligibility, but only after removing certain import restrictions on U.S. agricultural exports, as stipulated in the review.

- Termination and partial withdrawal. Requires USTR to notify Congress 60 days before any eligibility termination, and provides additional alternatives to termination, including partial withdrawal of preferences.

- Utilization strategies. AGOA utilization is heavily concentrated in select countries and products. The legislation encourages beneficiary countries and regional economic communities to develop AGOA utilization strategies and directs U.S. trade capacity building agencies to assist in strategy development.

- Role of women in development. States AGOA policy promoting the role of women in development and clarifies that AGOA eligibility requires protecting private property rights "for men and women."

- Other trade and investment agreements. Promotes the negotiation of other trade and investment agreements with AGOA countries, including a specific plan for free trade agreements. Also encourages implementation of WTO commitments, and stipulates objection to third-party agreements not covering substantially all trade. The original AGOA legislation similarly mandated potential FTA negotiations, but such efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.

- Agriculture capacity building funding. Requires the President to identify African countries with the greatest potential to increase agriculture exports and increases, from 20 to 30, workers required to assist AGOA agriculture exporters in meeting U.S. laws.

- Reporting requirements. Reinstates a previous AGOA requirement for a report within one year of passage, and biennially thereafter, addressing overall U.S. trade and investment relations with Africa, changes in country AGOA eligibility, the status of regional integration efforts, and a summary of U.S. trade capacity building efforts. The first report was released in June 2016.30

Governance, Democracy, and Human Rights

What is the state of democracy and human rights in Africa?

Types of government and levels of democratic accountability vary widely among sub-Saharan Africa's 49 countries. Democracy, rule of law, and human rights trends have long been a prominent focus of U.S. policy toward Africa, in part due to congressional interest and legislation.

Democratic Progress. Since the early 1990s, nearly all African countries have transitioned from military or single-party rule to at least nominally multiparty political systems in which elections are regularly held. Countries such as Senegal, Cabo Verde, and Ghana have had multiple peaceful, democratic transfers of power. Several southern African states, such as South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia, have developed strong institutions, though their political systems remain dominated by single parties that, in a number of cases, were born of liberation struggles against colonial or white-minority rule. Nigeria's 2015 elections were widely viewed as historic, marking the country's first peaceful transition of power from an incumbent president to an opposition candidate. The departures of long-serving leaders in Burkina Faso in 2014 and The Gambia in 2017 have also been heralded as positive signs of democratic progress in West Africa.

Challenges to Democracy. Despite this progress, the development of accountable democratic institutions remains limited in much of Africa. While most countries hold regular elections, many are marred by fraud, violence, or irregularities that often favor dominant political parties. Analysts have also noted a trend of "third-termism" in Africa, whereby leaders attempt to extend their mandates by circumventing, altering, or abolishing constitutional term limits (as in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda, among others). Seven African leaders have been in office for more than 30 years. In Zimbabwe, opposition to the long tenure in office of President Robert Mugabe, age 93, and dissatisfaction over poor economic conditions are generating a growing protest movement in the country, which also faces a potentially unstable succession. In countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Rwanda, and Sudan, viable democratic competition or independent civil society activism are very limited. Some governments have used repressive laws to restrict political and media freedoms. In several other countries, such as Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, and Guinea-Bissau, governments have been ousted by military coups in recent years. Weak parliamentary oversight capacity and legislative dominance by the executive branch are also problems in many African countries.

Governance Hurdles. Policies and budget allocations often benefit incumbent majority parties or special interests. Moreover, state institutions in Africa often fail to respond adequately to citizens' needs because they lack sufficient human and financial capacity or are beset by problems such as corruption and mismanagement. Countries such as Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Guinea-Bissau, Eritrea, Zimbabwe, and Burundi are ranked near the bottom of Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index.31 Endemic corruption also continues to corrode state effectiveness in Nigeria and Kenya and has challenged or dimmed the reputation of purportedly reform-oriented leaders in countries such as Liberia, Malawi, and Mali. The corrosive impacts of transnational drug trafficking have also impaired institutional capacity in some countries, notably in West Africa. The justice sector in many countries in the region is often subject to political influence and corruption; this can weaken public trust in justice and law enforcement systems and has spurred incidents of vigilante justice in many countries.

Conflict and State Collapse. In Somalia, the Central African Republic (CAR), and South Sudan, among other countries, state weakness and violent conflict impede the provision of even the most basic public services, and the conflicts have also resulted in widespread and severe human rights abuses. There is often a lack of accountability for such abuses, prompting international support for transitional justice processes and institutions, which seek to redress legacies of large-scale human rights violations, as a component of conflict resolution and postconflict processes.

How does the United States support democracy and human rights in Africa?

Several key tools are used by U.S. policymakers to promote democracy and human rights in Africa, including the following:

Diplomacy and Reporting. U.S. diplomats often publicly criticize or condemn undemocratic actions and human rights violations in Africa, and reportedly raise human rights concerns regularly in private meetings with African leaders. Some Members of Congress likewise raise concerns directly with African leaders, or through legislation. The State Department publishes annual congressionally mandated reports on human rights conditions globally, and on other issues of concern, such as international religious freedom and trafficking in persons (TIP). Such reports both document violations and, in some cases, provide the basis for U.S. policy actions, such as restrictions on assistance. The State Department and USAID also finance international and domestic election observer missions in Africa that produce reports assessing the relative credibility of electoral contests.

Foreign Aid. Multiple U.S. aid programs support African electoral institutions; train African political parties, civil society organizations, parliaments, and journalists; assist local government officials in improving service delivery; and provide expert advice to African governments considering legal changes pertaining to more accountable governance, among other areas of activity. Some U.S. security assistance programs are also designed to improve the human rights records of African security forces and/or advance the rule of law by building the capacity of judicial and law enforcement bodies

Foreign Aid Restrictions. Congress has imposed human rights-related restrictions or conditions on aid to specific African countries (e.g., Ethiopia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe, in P.L. 114-113), often through the enactment of foreign aid appropriations measures. Aid to multiple African governments is also restricted due to legislation curtailing or denying certain types of aid to any country that fails to observe a range of human rights norms regarding, for instance:

- religious freedom (under the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, with Sudan and Eritrea currently designated);

- the use of child soldiers (under the Child Soldiers Prevention Act and related legislation, with DRC, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan listed in 2016); and

- trafficking in persons (under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act and related legislation, with Burundi, CAR, Comoros, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe listed in 2016).32

Sanctions. Executive orders authorize U.S. sanctions targeting individuals implicated in human rights violations and/or undermining democratic transitions or peace processes in countries including Burundi, CAR, DRC, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Zimbabwe. In January 2017, citing progress by the Sudanese government on a number of peace and humanitarian issues and cooperation with the United States on counterterrorism and regional security efforts, the Obama Administration took actions to ease sanctions on Sudan, though many restrictions remain in place.

Prosecutions. The United States has helped fund special tribunals that investigated and prosecuted human rights violations in Sierra Leone, Rwanda, and Chad. The United States is not a state party to the International Criminal Court (ICC) but has provided diplomatic, informational, and logistical aid in support of some ICC prosecutions. U.S. courts have also tried some persons accused of human rights abuses in African countries, notably Rwanda and Liberia, often using violations of immigration laws as a basis for prosecution. The United States has been a proponent of the establishment by the African Union of a court to investigate abuses in South Sudan.

Peace and Security Issues

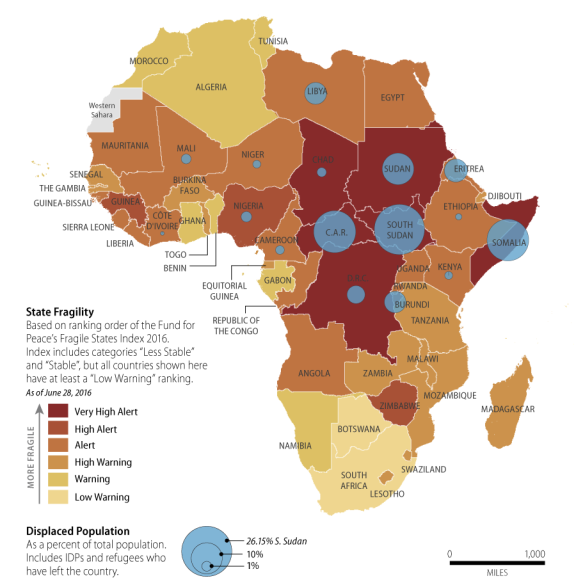

Armed conflict and instability in parts of Africa continue to threaten regional security, impede development and investment, and contribute to widespread human suffering. This is underscored by the fact that multiple African countries rank among the most fragile states globally, according to the Fragile States Index (see Figure 2).33 A majority of the U.N.'s peacekeeping operations are located in sub-Saharan Africa, with eight missions currently authorized in the region.34 The U.N.-authorized African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is not U.N.-conducted, but it carries out peacekeeping activities, as well as broader stabilization and counterterrorist operations, primarily against the Al Qaeda-linked group Al Shabaab. Under the U.N. system of assessed financial contributions to peacekeeping, the United States is the top source of funding for U.N. peacekeeping missions, providing over a quarter of their cost. The United States is a major funder of regional stabilization operations in Africa, drawing on bilateral security assistance funding to prepare troop contributors and support deployment logistics. The United States also supports various conflict prevention, mitigation, and mediation efforts in Africa.

In addition to intrastate conflicts and localized instability, the continent faces diverse transnational threats, which continue to pose a challenge to both African and U.S. interests. Across Africa, porous borders, weak government institutions, and corruption have created permissive environments for such threats, including operations by terrorist groups, illicit trafficking (e.g., of narcotics and people), and maritime piracy.

Violent Extremism.35 Violent Islamist extremist groups in Northwest and East Africa—including Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Al Shabaab (Somalia), Boko Haram (the Lake Chad Basin region), and several emergent groups active in Mali—threaten state stability, regional security, and U.S. national security interests. While such groups have historically been most active in rural areas where there is little government presence, since 2013 there have been several mass casualty terrorist attacks targeting big city hotels, malls, and restaurants popular with Westerners (e.g., in Nairobi, Kenya; Bamako, Mali; Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; and Grand Bassam [near Abidjan],Cote d'Ivoire).

Other Transnational Threats. In some parts of the continent, weak law enforcement and justice mechanisms—as well as collusion by state actors—have allowed transnational crime networks to operate with relative impunity. In some countries, these syndicates may threaten state stability. U.S. concern has grown over potential links between Africa-based drug traffickers and terrorist groups—notably in connection with the transit through Africa of Latin American cocaine bound for Europe and Southwest Asian heroin bound for various destinations. Reported links between armed extremist or insurgent groups and wildlife trafficking networks are another growing security concern, as is a rise in illegal poaching and wildlife trafficking generally.36

Maritime Security. Africa's coastal waters, particularly along the Gulf of Guinea, the Gulf of Aden, and the western Indian Ocean, have been highly susceptible to illegal fishing, trafficking, and piracy in recent years. African governments have generally been unable to adequately police the region's waters. Criminal elements exploiting the absence of state controls smuggle people, drugs, and weapons, and dump hazardous waste. Maritime commerce and offshore oil production facilities in some regions have faced high rates of maritime piracy, involving both theft and kidnapping for ransom, and sabotage. Waters off Nigeria and in the broader Gulf of Guinea rank among the most dangerous in the world for acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea. While the waters off the Somali coast have seen a dramatic reduction in pirate attacks in the past five years as a result of international antipiracy efforts, analysts warn of the continued threat of piracy in the region. In March 2017, pirates seized an oil tanker off the Somali coast of the Indian Ocean, marking the first hijacking of a large commercial vessel in waters off the Somali coast since 2012.

What are the major armed conflicts in Africa today?

Several countries, including Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Angola, continue to rebuild after civil wars in the 1990s and early 2000s, while others, such as Cote d'Ivoire and Guinea-Bissau, confront the legacy of more recent conflicts. Meanwhile, parts of DRC, Somalia, and Sudan remain afflicted by long-running patterns of instability. Newer conflicts have broken out in recent years in CAR, Mali, and South Sudan. Other African countries, such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali, and the countries of the Lake Chad Basin region (Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon) face threats from armed violent extremist or insurgent groups. Major conflicts include the following:

East Africa

The conflict in South Sudan, which erupted in late 2013, is of significant concern for U.S. and African policymakers.37 A shaky peace agreement, signed in August 2015, collapsed in July 2016, spurring a new round of violence. By some estimates, more than 50,000 people have been killed and more than 3.4 million people have been displaced.38 It is Africa's largest refugee crisis and the third largest in the world. Some 4.9 million people face "severe" food insecurity, with more than 100,000 experiencing famine and 1 million on the brink.39 The United States is South Sudan's largest bilateral donor of humanitarian aid.

Conflict and insecurity persist in parts of Sudan, notably the Darfur region and Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states.40 Over a decade since the United States declared that genocide was occurring in Sudan's western Darfur region, the conflict eludes resolution, and violence from 2015 into early 2016 resulted in displacement at a level not seen since the early years of the crisis. The government declared a cessation of hostilities in mid-2016, but periodic skirmishes and attacks against civilians continue. More than 3.2 million Sudanese are displaced internally and over half a million are refugees in neighboring countries.41 By some estimates, 5.8 million people in the country are in need of humanitarian aid.42

The threat posed by the insurgent and terrorist group Al Shabaab in war-torn Somalia remains severe.43 Drought conditions, combined with security restrictions on humanitarian access, have worsened the food security situation, and parts of Somalia face the threat of famine in 2017. Roughly 1.2 million people remain displaced in Somalia, and almost 900,000 live as refugees in neighboring countries and Yemen.44 Al Shabaab has demonstrated its intent and ability to conduct terrorist attacks against targets in the broader East Africa region—most notably Kenya, which has seen a significant increase in Al Shabaab attacks since 2011. Kenya, along with Uganda, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone, has also been the target of terrorist attacks in retaliation for its role in AMISOM, which has led the military offensive against Al Shabaab.

Central Africa

The 2013 rebel overthrow of CAR's central government triggered a crisis that led to the collapse of an already fragile state.45 Widespread violence followed, much of it playing out along ethno-religious lines, and resulted in massive displacement and human suffering. With the support of the international community, CAR established a transitional government and held elections in early 2016, but internal stability and the continuing actions of armed groups remain a challenge. Ongoing insecurity in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) continues to pose a threat to the broader Great Lakes region, despite the presence of a U.N. peacekeeping operation with a robust mandate to disarm militias.46 Continuing controversy over election delays, restrictions on some opposition figures, and a bid by the incumbent regime to extend its tenure have led to mass protests that have sometimes turned violent, resulting in fatalities. The operational capacity of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), a small armed group of Ugandan origin responsible for thousands of civilian kidnappings and murders, has been reduced through a combination of U.S., Ugandan, and multilateral efforts, but it continues to terrorize civilian populations in remote areas.47 In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza's reelection to a third term in 2015, which many viewed as unconstitutional and a violation of a landmark peace accord, has sparked a violent political crisis with regional implications.48 In Republic of Congo, some signs point to a renewed insurgency in the wake of disputed elections in 2016 that maintained longtime leader Denis Sassou-Nguesso in office.

West Africa

In the Lake Chad Basin region, Boko Haram, a violent extremist group, has grown increasingly deadly in its attacks against state and civilian targets since 2010 in Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon.49 Tens of thousands have been killed in Boko Haram attacks, and more than 2.6 million people have been displaced across the region.50 In 2015, the group formally affiliated with the Islamic State organization, although the extent of operational ties remains unclear; an apparent leadership split in 2016 raised further questions about the group's cohesion and direction. Mali continues to struggle in the wake of its 2011-2013 political, humanitarian, and security crisis, despite assistance from the French military and a U.N. peacekeeping operation. While a coalition of northern rebel groups agreed to a peace accord with the government in 2015, the complex array of underlying causes of Mali's crisis has not been resolved and security conditions have deteriorated since 2014. In addition to domestic armed groups, Malian and international troops continue to face asymmetric attacks from Islamist extremist groups.

Southern Africa

Since 2012, Mozambique has faced a low-level armed insurgency by the main opposition party, RENAMO, which, among other goals, seeks electoral reforms, the decentralization of governance, and a more prominent provincial governing role for itself. Various domestic and internationally aided efforts to negotiate an end to the conflict have yielded few tangible successes to date. Angola has also faced long-running sporadic armed rebellion by the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) in Cabinda, a small oil-rich province that is separated from the rest of Angola by the DRC.

U.S. Assistance Programs in Africa

What are the objectives of U.S. assistance to Africa?

U.S. foreign aid programs aim to address Africa's many development challenges, meet urgent humanitarian needs, and improve security. Much of this aid is administered by USAID, typically under country strategies that target each country's specific development needs, as well as under multiple global and Africa-specific presidential development initiatives. The State Department administers additional programs aimed at bolstering health, encouraging the rule of law, countering trafficking, and improving military and police professionalism, often in coordination with other executive branch agencies. The Department of Defense (DOD) implements some State Department-funded assistance programs and, in certain circumstances, is authorized to provide its own assistance to foreign militaries and internal security forces. DOD also carries out military-to-military cooperation activities in many African countries. The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) supports large-scale, multiyear development projects in selected countries under agreements known as Compacts. Compacts are typically five-year aid programs targeting a limited number of crucial impediments to economic growth (e.g., building roads or irrigation infrastructure) that the recipient country carries out under MCC oversight.51

How much aid does the United States provide to sub-Saharan Africa?52

In recent years, sub-Saharan Africa has generally received between 20% and 25% of total U.S. bilateral aid, the bulk of which supports health programs in the region. Nearly $8.27 billion in State Department and USAID-administered funds were allocated specifically for sub-Saharan Africa from FY2015 appropriations, and the initial estimate for FY2016 stood at $7.03 billion as of mid-2016—not yet including emergency food aid, which totaled $1.28 billion in FY2015 and is allocated during the year according to need. Many countries receive additional globally or functionally allocated funding, such as humanitarian and disaster aid. Some also receive MCC-funded assistance, which is not included in the above totals. The Obama Administration requested $7.10 billion specifically for Africa FY2017, not including most types of humanitarian aid or MCC funding. The United States also channels substantial aid to Africa through international financial institutions and U.N. entities.

African recipients of $300 million or more in FY2015 bilateral assistance included Nigeria, Tanzania, South Africa, Uganda, Kenya, Zambia, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (see Table A-1). Between FY2003 and FY2010, U.S. aid to Africa grew rapidly due to global health spending increases, notably for HIV/AIDS, and to more moderate increases in economic and security aid. In recent years the topline figure has stabilized at roughly $7.5 billion to $8 billion (including food aid)—roughly seven times as large, in nominal terms, as in FY2002, when it stood at $1.1 billion.

Under the Obama Administration, which global presidential development initiatives channeled U.S. aid to Africa?

A large portion of U.S. bilateral aid to African countries is provided under presidential development initiatives. These are typically large, broad-based programs that reflect the policy priorities and program implementation approach of a particular administration. Most have a global focus, but some are targeted specifically toward Africa. Key Obama Administration initiatives with a major or sole focus on Africa included the following:

The Global Health Initiative (GHI). The GHI was created in 2009 to coordinate and integrate the implementation of three global health initiatives launched during the George W. Bush Administration: the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI), and the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) Program. The GHI also seeks to strengthen domestic health systems in developing countries, and promotes increased country "ownership" and financing of health assistance programs that U.S. assistance has supported.53 Key GHI program areas include maternal and child health; family planning and reproductive health; nutrition; social services for vulnerable children; HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment; and a range of disease-specific and other pandemic outbreak efforts.

Feed the Future (FtF)/New Alliance.54 FtF is a government-wide, USAID-led initiative launched in 2009 to fulfill U.S. commitments under a global food security initiative of the Group of Eight (G-8). It seeks to reduce poverty and malnutrition by helping selected countries to improve food security, boost agricultural production, and expand related market value chains. It focuses on 19 focus countries—12 of which are in Africa—and selected regions.55 FtF complements the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, an international initiative to promote the formation of public-private partnerships in Africa that foster agricultural policy reforms by African governments, marshal related private sector investments, and increase aid by G-8 countries. At the 2014 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit (ALS),56 the Obama Administration and the AU Commission jointly announced "more than $10 billion in planned socially responsible private sector investments through the New Alliance."57 The Administration also pledged to provide, through FtF, 1,300 youth fellowships and training opportunities.

Global Climate Change Initiative (GCCI). Africa is considered to be among the geographic regions most likely to experience negative social and environmental impacts attributable to climate change. The Obama Administration's GCCI seeks to respond to anticipated climate shocks by

- building social resilience and adaptation to extreme weather and climate events to reduce associated risk of damage, loss of life, and instability;

- promoting clean energy technologies, supportive regulatory environments, and low-emission development strategies in selected countries; and

- supporting environmental conservation and sustainable land and forest uses to reduce carbon emissions, preserve species, and protect biodiversity.

What were the Obama Administration's Africa-specific presidential aid initiatives?

Power Africa.58 Power Africa is a five-year, USAID-led, multiagency presidential initiative launched in 2013 to increase access to electricity in Africa, the most electrification-poor global region. The initiative fosters public-private partnerships, facilitates access to private and U.S. export financing, provides technical assistance for power-related projects, and supports cooperation with other international donors and development agencies. U.S. export credit agencies have set out financing targets for Power Africa, but meeting those targets depends on private business demand for their financial products. When Power Africa was first launched, it was supported with a mix of technical assistance and potential U.S. trade agency loan and financial service commitments worth up to $7.8 billion, complemented by a reported $9 billion in private sector project commitments.59 Key initial targets included the creation of more than 10,000 megawatts (MW) of new, cleaner electricity generation capacity and new power connections for 20 million households and businesses.

During the 2014 ALS, President Obama renewed his commitment to Power Africa and announced expanded initiative goals of an aggregate of 30,000 MW in additional capacity and 60 million or more new power connections. Additionally, he pledged new technical assistance, primarily administered by USAID, of $300 million per year starting in FY2016, on top of an FY2013-FY2015 USAID total of $285 million. He also announced new private sector pledges. A 2015 White House release indicated that a mid-year total of nearly $31.5 billion had been committed to Power Africa by the private sector ($20 billion) and by other donor governments and multilateral agencies ($11.5 billion). By early 2016, USAID reported, total commitments had grown to $43 billion.60

Congress has shown substantial interest in the goals and implementation of Power Africa. Several bills were introduced in the 113th and 114th Congresses that sought to authorize an approach similar to that pursued under Power Africa. In early 2016, President Obama signed into law the Electrify Africa Act of 2015 (EAA, P.L. 114-121), which makes it U.S. policy to pursue a range of U.S. and international efforts to expand African access to power. It requires the President to submit to Congress "a comprehensive, integrated, multiyear strategy" to encourage African governments to "implement national power strategies and develop an appropriate mix of power solutions to provide access to sufficient reliable, affordable, and sustainable power in order to reduce poverty and drive economic growth and job creation." The act lays out a range of criteria that the strategy must take into account, but its approach is broadly analogous to that pursued under Power Africa. While the act did not make any new appropriations and required the Obama Administration to submit a strategy, its enactment suggests that there is broad congressional support for continuing Power Africa-like activities. Whether Congress may appropriate funding at levels similar to those allocated by the Obama Administration and whether and in what manner the Trump Administration may continue Power Africa or pursue similar activities under the EAA has yet to be determined.

Trade Africa. Trade Africa is a multiagency initiative that aims to encourage U.S. private sector trade and investment activities in Africa and boost trade among African countries. In its initial phase, the program focused on the East African Community (EAC, comprising Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi), with two main goals: to deepen the U.S.-EAC Trade and Investment Partnership begun in 2012, and to establish a USAID-led East Africa Trade and Investment Hub, an expansion of an existing "trade hub." Specific program objectives included increasing EAC exports to the United States by 40%, doubling intra-EAC trade, and reducing selected intra-EAC transit times by 30%. The Obama Administration held up Trade Africa's initial phase as having contributed to "dramatic progress" in the U.S.-EAC trade relationship, which saw EAC exports to the United States increase by 24% in 2013-2014.61

The Obama Administration also expanded the Trade Africa initiative to several new partner countries, including Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Mozambique, Senegal, and Zambia. The State Department's FY2017 budget request includes $75 million in Development Assistance (DA) for Trade and Investment Capacity Building in Africa. This assistance, an expansion of Trade Africa, was designed to "improve sub-Saharan Africa's capacity for trade and export competitiveness, including trade facilitation to reduce the time and cost to trade, while increasing opportunities for U.S. businesses to positively participate in and benefit from African economic growth."62

Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI). YALI, initiated by President Obama in 2010, is a joint State Department- and USAID-administered initiative that fosters the development of young African business, civic, and public management leaders through exchange-based fellowships. The initiative's flagship program, the Mandela Washington Fellowship for Young African Leaders, brings youth leaders to the United States to participate in a six-week leadership course at a partnering U.S. college or university. At the 2014 ALS, President Obama pledged that the Mandela Fellowship would be expanded from 500 participants to 1,000. He also announced that YALI would provide a set of online mentoring and networking resources for program fellows, and that the Administration would launch four Regional Leadership Centers (RLCs) to foster leadership development through trainings, networking forums, and related activities.

The State Department's FY2017 budget request includes $20 million in Educational and Cultural Exchange (ECE) funding for YALI, with an additional $10 million in DA to support the RLCs, which are located in South Africa, Kenya, Ghana, and Senegal.

Security Governance Initiative (SGI). Launched in 2014, SGI is a "joint endeavor between the United States and six African partners that offers a comprehensive approach to improving security sector governance and capacity to address threats."63 The initiative is focused on both civilian (e.g., police) and military security institutions, and on the cabinet ministries that oversee the security sector. The initial partners are Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Tunisia. The Administration committed $65 million for SGI in FY2015 and $83 million per year thereafter, with no specified end-date. Country plans vary; some seek to enhance particular security agencies, while others focus on strategy formulation and planning, or interagency coordination. Objectives also vary; examples include border control and justice sector strengthening. The State Department's FY2017 request includes $14 million in Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) account funding for SGI, with additional resources expected to come from regional allocations from other accounts, such as International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) funding. DOD Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funds have been identified as another source of requested SGI funding—DOD's FY2016 budget request included $47 million for SGI under the Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF).64

African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership (APRRP). Initiated in 2014, APRRP seeks to provide specific African countries with relatively high-level military capabilities for use in AU and U.N. peacekeeping deployments. Aid provided under APRRP may include equipment transfers and other support for military logistics, airlift, field hospitals, and formed police units.65 In the near term, APRRP is focused on six countries: Senegal, Ghana, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. The Administration has committed $110 million per year for APRRP, starting in FY2015 and lasting three to five years.66 The FY2017 request includes that amount in PKO funding for APRRP.

How does the United States respond to African security challenges?

The United States has invested significant resources in promoting peace and stability in Africa and countering threats to U.S. interests, such as those posed by drug traffickers, pirates, and violent extremist groups. U.S. security assistance in Africa involves a range of activities, including military training and equipment programs, education and professionalization initiatives, and law enforcement assistance. U.S. security assistance has increasingly focused on building counterterrorism capacity, with significant new funding allocated through the CTPF, which was proposed by President Obama in 2014 and first authorized and funded by Congress in P.L. 113-291 and P.L. 113-235. The Department of State and DOD each administer some types of security assistance.67 U.S. military advisors are also periodically deployed to work with African countries and regional organizations.

The United States plays a key role in U.N. Security Council deliberations on African conflicts, notably, in recent years, on Burundi, CAR, the DRC, Mali, Somalia, and the Sudans. The United States is also a major funder of peacekeeping missions in the region, and has provided significant bilateral training, equipment, and logistical support to African militaries contributing troops to these missions. Much of this bilateral aid is provided under the State-Department-run African Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA) program and the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI). As described above, the APRRP provides additional, more advanced military capabilities to selected partner states. U.S. efforts have also sought to bolster the role of the AU and sub-regional entities in conflict mediation and peacekeeping efforts.

What is the U.S. response to terrorist threats in Africa?68

The United States engages in a range of efforts, both military and civilian, to prevent and deter terrorism in Africa. The Obama Administration's 2015 National Security Strategy identified "violent extremists fighting governments in Somalia, Nigeria, and across the Sahel"—along with other ongoing conflicts in Africa—as "threats to innocent civilians, regional stability, and our national security." Consistent with the Administration's National Strategy for Counterterrorism, its Africa Strategy set out as a goal "disrupting, dismantling, and eventually defeating Al-Qa'ida and its affiliates and adherents in Africa," in part by strengthening the capacity of "civilian bodies to provide security for their citizens and counter violent extremism through more effective governance, development, and law enforcement efforts." In its FY2017 budget requests for foreign aid and DOD activities, the Obama Administration indicated that its counterterrorism partnership efforts in Africa sought to deny terrorists safe havens, operational bases, and recruitment opportunities. Specific efforts toward these ends included programs to build regional intelligence, military, law enforcement, and judicial capacities; strengthen aviation, port, and border security; stem terrorist financing; and counter the spread of extremist ideologies.

Current U.S.-led regional counterterrorism efforts include two multifaceted interagency efforts: the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP, established in 2005) in North-West Africa and the Partnership for Regional East Africa Counterterrorism (PREACT, established in 2009). TSCTP includes military and police train-and-equip programs and border security initiatives, justice sector support, counterradicalization programs, and public diplomacy efforts. It is led by the State Department's Africa Bureau, with USAID and DOD implementing components and playing a role in strategic guidance. Assistance to Lake Chad Basin states in countering Boko Haram has become a growing focus for TSCTP, with significant additional assistance provided under other programs. PREACT, modeled on TSCTP, is a smaller initiative that is part of a broader array of counterterrorism-related assistance efforts in East Africa, many of them bilateral. Some TSCTP and PREACT programs seek to encourage regional cooperation through multinational training events, while other TSCTP and PREACT assistance is provided to individual countries. Other U.S. regional security initiatives, such as the State Department Bureau of Counterterrorism's Regional Strategic Initiative (RSI), overlap with these programs and seek to cover some gaps, including in the Lake Chad Basin area. DOD, for its part, conducts regional operations in which U.S. military personnel work with local counterparts to improve intelligence, regional coordination, logistics, border control, and targeting, notably through surveillance assistance.

What roles does the U.S. military play in Africa?

U.S. Africa Command's (AFRICOM's) Theater Campaign Plan for FY2016-FY2020 identifies five key goals for the U.S. military in Africa: (1) neutralize Al Shabaab and transition the mandate of the AMISOM to the Somali government; (2) degrade violent extremist organizations in the Sahel-Maghreb and contain instability in Libya; (3) contain Boko Haram; (4) interdict illicit activity in the Gulf of Guinea and Central Africa; and (5) build African peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance, and disaster response capacities. Protecting U.S. personnel and facilities and securing U.S. access is characterized as an "enduring task" in the plan. The approach of AFRICOM, as outlined in the plan and in the command's 2016 Posture Statement, emphasizes counterterrorism cooperation with African "partners" and international allies (e.g., France and the United Kingdom), as well as with U.S. civilian agencies.

The U.S. military periodically takes direct action against terrorist threats in sub-Saharan Africa, including through airborne or ground assault-based strikes on targeted terrorist group members in Somalia. It has also interdicted several suspected terrorists and extremist group interlocutors.69 The Obama Administration broadened its justification for direct U.S. military action in Somalia in 2015, indicating in a notification to Congress consistent with the War Powers Resolution that its operations in Somalia were carried out not only "to counter Al Qaeda and associated elements of Al Shabaab" (as previously reported), but also "in support of Somali forces, AMISOM forces, and U.S. forces in Somalia."70 The United States has not deployed combat troops to Somalia, but it does have U.S. military advisors posted in the country to provide support to African partners. The United States has also provided logistical and intelligence support to French military counterterrorism operations in the Sahel since 2013.

A long-running contingency operation, Operation Enduring Freedom-Trans-Sahara (OEF-TS; funded annually at over $80 million), which supports TSCTP, does not limit its focus to counterterrorism, according to DOD's FY2017 budget request.71 Rather, it focuses on "overall security and cooperation" by "forming relationships of peace, security, and cooperation" among countries in the region. In East Africa, Operation Enduring Freedom-Horn of Africa (OEF-HOA) has a different scope, supporting activities at the U.S. military's only permanent base in Africa, in Djibouti; Special Operations Command operations in the Horn of Africa (and Afghanistan); and Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) operations in the region. Other ongoing operations include the deployment, since 2013, of up to 350 U.S. military personnel and surveillance assets to Niger and, since October 2015, of up to 300 U.S. military personnel and surveillance aircraft to Cameroon, to conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations.72 Since 2011, DOD has also provided logistics and advisory support to African forces, primarily from Uganda, to counter the LRA in Central Africa under Operation Observant Compass (OOC). DOD may provide support (up to $85 million globally) to forces (including irregular forces or nonstate groups) supporting counterterrorism operations in which U.S. special operations forces are engaged, including in Africa, as authorized via Section 1208 of the FY2005 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 108-375), as amended. Recipients and funding levels are classified.

Beyond counterterrorism missions, U.S. forces routinely conduct joint exercises with African militaries, and share disaster response, humanitarian assistance, maritime security, antipiracy, and counterterrorism skills, among others. The U.S. military has also played a role in encouraging security sector reform in some African countries, such as Liberia and DRC. A small number of U.S. military personnel are deployed on the continent with U.N peacekeeping operations.

Outlook

The 115th Congress has commenced consideration of current and prospective U.S. policies toward Africa, as well as appropriations for U.S. foreign assistance, diplomacy, and military activities. These discussions are progressing in the context of the Trump Administration's release on March 16, 2017, of its FY2018 "budget blueprint," which suggests significant shifts in executive branch foreign policy priorities and foreign aid funding levels. The implications for U.S. Africa policy, U.S. diplomatic relations with African governments, and aid programs on the continent remain to be seen. Other legislative initiatives and oversight activities are also likely to shape U.S. policy toward Africa and toward specific countries, as was the case in the 114th and previous Congresses. Congressional responses to emerging crises, such as famine concerns in three African countries, increasingly intractable conflicts in South Sudan and Mali (among others), transnational security threats, and the appropriate balance between U.S. diplomacy, development, and defense priorities in Africa, may also influence or direct U.S. policy.

Appendix. U.S. Assistance to Africa

Table A-1. U.S. Bilateral Foreign Assistance to Africa, by Country/Regional Program

State Department- and USAID-administered funds; Appropriations; $ Millions. Figures are rounded.

|

Country |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 (req.) |

|

TOTAL |

7,815.1 |

7,826.2 |

7,511.1 |

8,265.4 |

6,881.0 |

|

Angola |

59.7 |

53.7 |

54.8 |

54.8 |

50.4 |

|

Benin |

28.6 |

23.7 |

23.5 |

23.3 |

23.7 |

|

Botswana |

67.0 |

55.0 |

50.6 |

37.3 |

46.3 |

|

Burkina Faso |

35.1 |

16.0 |

15.7 |

23.4 |

14.3 |

|

Burundi |

41.4 |

53.3 |

30.0 |

57.6 |

43.8 |

|

Cabo Verde |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Cameroon |

14.0 |

25.6 |

38.8 |

49.0 |

45.8 |

|

CAR |

10.1 |

32.2 |

30.5 |

41.3 |

14.7 |

|

Chad |

85.0 |

58.0 |

67.2 |

62.0 |

0.3 |

|

Comoros |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Cote d'Ivoire |

150.7 |

156.8 |

121.0 |

138.8 |

145.7 |

|

DRC |

254.4 |

322.9 |

331.2 |

320.4 |

277.6 |

|

Djibouti |

7.7 |

8.8 |

11.5 |

16.0 |

12.9 |

|

Ethiopia |

706.7 |

619.6 |

583.7 |

650.9 |

403.9 |

|

Gabon |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

Ghana |

172.7 |

154.6 |

137.1 |

137.6 |

146.3 |

|

Guinea |

23.7 |

20.4 |

22.0 |

24.0 |

23.7 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

- |

- |

- |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Kenya |

507.2 |

557.5 |

645.0 |

741.8 |

630.3 |

|

Lesotho |

15.8 |

33.2 |

32.1 |

38.4 |

47.6 |

|

Liberia |

209.8 |

190.1 |

165.8 |

112.1 |

125.4 |

|

Madagascar |

69.5 |

58.0 |

63.0 |

70.2 |

68.9 |

|

Malawi |

183.7 |

203.5 |

196.0 |

222.4 |

201.8 |

|

Mali |

235.6 |

132.1 |

135.4 |

147.7 |

118.4 |

|

Mauritania |

12.1 |

8.8 |

5.3 |

8.7 |

2.4 |

|

Mauritius |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Mozambique |

347.3 |

381.8 |

402.4 |

450.2 |

409.1 |

|

Namibia |

90.9 |

32.2 |

23.6 |

16.8 |

43.7 |

|

Niger |

58.9 |

32.1 |

34.4 |

58.9 |

9.9 |

|

Nigeria |

646.9 |

699.8 |

703.0 |

642.8 |

607.5 |

|

ROC |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

|

Rwanda |

197.1 |

203.6 |

187.5 |

169.2 |

160.9 |

|

Sao Tome and Principe |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Senegal |

109.6 |

105.1 |

118.3 |

113.9 |

102.3 |

|

Seychelles |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Sierra Leone |

17.7 |

13.3 |

15.5 |

11.7 |

6.8 |

|

Somalia |

302.7 |

319.6 |

302.0 |

373.6 |

209.2 |

|

South Africa |

542.2 |

513.6 |

286.3 |

323.7 |

374.2 |

|

South Sudan |

619.6 |

556.9 |

434.6 |

576.1 |

265.0 |

|

Sudan |

196.0 |

153.2 |

168.9 |

130.6 |

9.1 |

|

Swaziland |

31.4 |

26.1 |

43.5 |

46.8 |

43.5 |

|

Tanzania |

480.6 |

565.9 |

591.5 |

634.1 |

590.6 |

|

The Gambia |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

Togo |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

|

Uganda |

460.1 |

487.2 |

491.9 |

505.5 |

469.1 |

|

Zambia |

312.8 |

395.4 |

359.1 |

414.1 |

415.9 |

|

Zimbabwe |

167.1 |

161.9 |

169.0 |

171.6 |

161.6 |

|

African Union |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

1.2 |

|

State – AF |

80.4 |

90.7 |

97.0 |

206.6 |

211.8 |

|

USAID – AF |

68.3 |

101.8 |

100.4 |

150.2 |

120.2 |

|

USAID – CA |

22.6 |

30.7 |

39.4 |

57.8 |

16.6 |

|

USAID – EA |

62.7 |

57.0 |

70.6 |

70.7 |

65.1 |

|

USAID – SAH |

- |

7.6 |

18.4 |

18.4 |

28.3 |

|

USAID – SA |

28.1 |

26.1 |

25.5 |

45.4 |

34.2 |

|

USAID – WA |

79.6 |

79.2 |

65.1 |

95.9 |

79.3 |

Source: State Department Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2014-FY2017.

Notes: Does not include additional funding that may be allocated from regionally or centrally managed programs, or additional funding from other agencies such as the MCC or DOD. FY2016 and FY2017 funding levels do not include emergency humanitarian aid. Does not include U.S. contributions to multilateral aid organizations (such as U.N. entities and international financial institutions) active in Africa. Totals may not add up due to rounding.

CAR=Central African Republic; DRC=Democratic Republic of Congo; ROC=Republic of Congo.

Regional Programs: AF=Africa Regional; CA=Central Africa Regional; EA=East Africa Regional; SAH=Sahel Regional; SA=Southern Africa Regional; WA=West Africa Regional.

Table A-2. U.S. Bilateral Foreign Assistance to Africa, by Account

State Department- and USAID-administered funds; Appropriations; $ Millions. Figures are rounded.

|

Country |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 (req.) |

|

TOTAL |

7,815.1 |

7,826.2 |

7,511.1 |

8,265.4 |

6,881.0 |

|

Enduring |

7,620.4 |

7,471.1 |

7,326.1 |

7,586.2 |

6,881.0 |

|

DA |

1,002.1 |

1,170.1 |

1,118.2 |

1,161.0 |

1,044.5 |

|

ESF |

607.7 |

352.8 |

416.0 |

182.0 |

479.2 |

|

FMF |

16.8 |

15.8 |

15.3 |

11.0 |

19.2 |

|

GHP - State |

2,993.3 |

3,173.6 |

3,017.4 |

3,346.7 |

3,398.2 |

|

GHP - USAID |

1,375.6 |

1,419.3 |

1,458.5 |

1,472.2 |

1,442.0 |

|

IMET |

15.2 |

13.6 |

16.1 |

16.7 |

15.7 |

|

INCLE |

85.9 |

53.3 |

66.2 |

29.1 |

49.2 |

|

NADR |

35.5 |

39.2 |

36.6 |

41.9 |

44.9 |

|

PL 480 Title II (food aid) |

1,305.3 |

1,063.6 |

1,069.2 |

1,275.1 |

86.0 |

|

PKO |

183.0 |

169.8 |

112.5 |

50.6 |

302.3 |

|

OCO |

194.8 |

355.0 |

185.0 |

679.2 |

- |

|

ESF |

- |

148.6 |

- |

275.1 |

- |

|

FMF |

- |

- |

- |

57.9 |

- |

|

INCLE |

- |

35.0 |

- |

49.7 |

- |

|

NADR |

7.8 |

7.4 |

5.0 |

- |

- |

|

PKO |

187.0 |

164.1 |

180.0 |

296.5 |

- |

Source: State Department Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2014-FY2017.