U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Changes from April 21, 2020 to October 17, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- USACE Primer

- USACE Funding

- Annual Appropriations Process

- President's Budget Request

- Congressional Appropriation Acts

- Additional Funding

- Agency Work Plan

- Trends and Policy Questions

- Shift to Administration-Developed Work Plans

- Construction Backlog

- Shift to Operation and Maintenance

- Navigation

- Flood Risk Reduction

- Environment

Figures

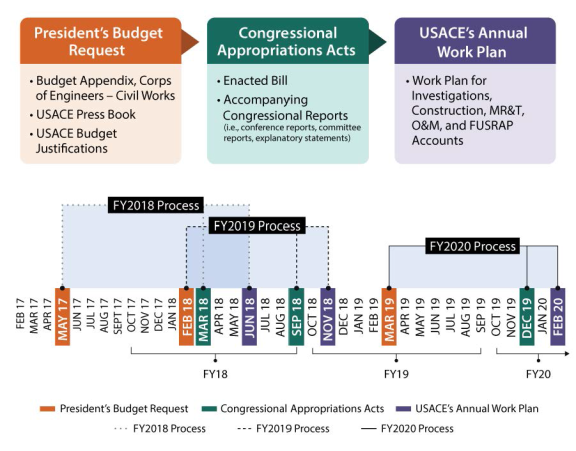

- Figure 1. FY2018 to FY2020 Appropriations Process Timeline

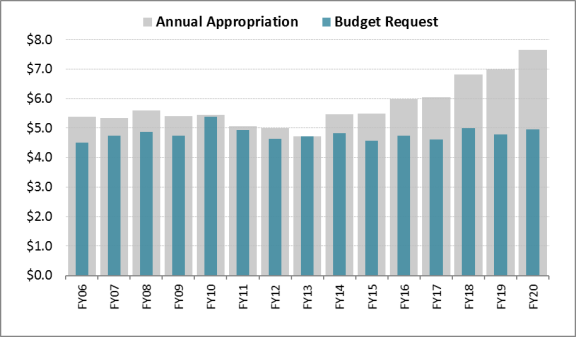

- Figure 2. Budget Request and Annual Appropriations for USACE Civil Works, FY2006 to FY2020

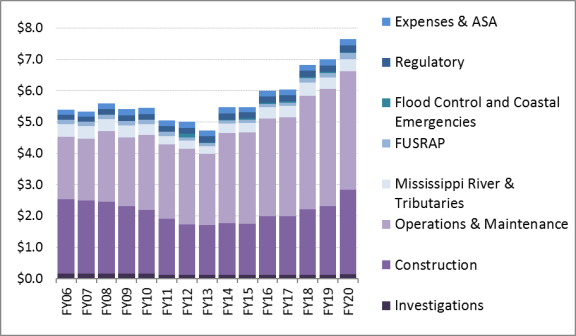

- Figure 3. USACE Annual Appropriations by Account, FY2006 to FY2020

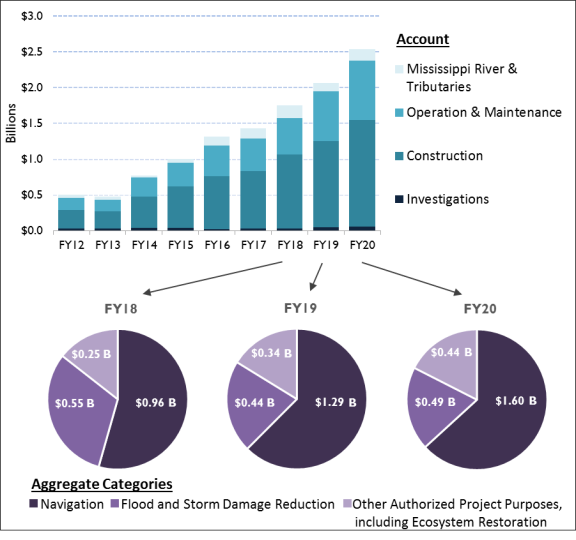

- Figure 4. Additional Funding in USACE Annual Appropriations by Account and Aggregated Categories

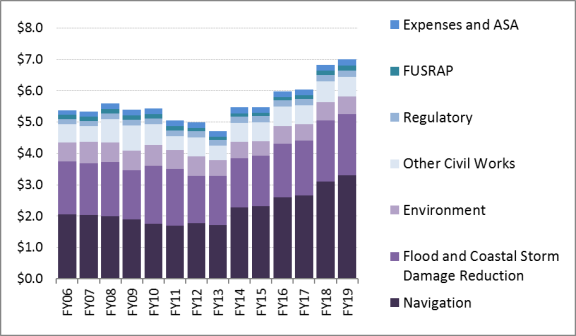

- Figure 5. USACE Annual Appropriations by Business Line, FY2006 to FY2019

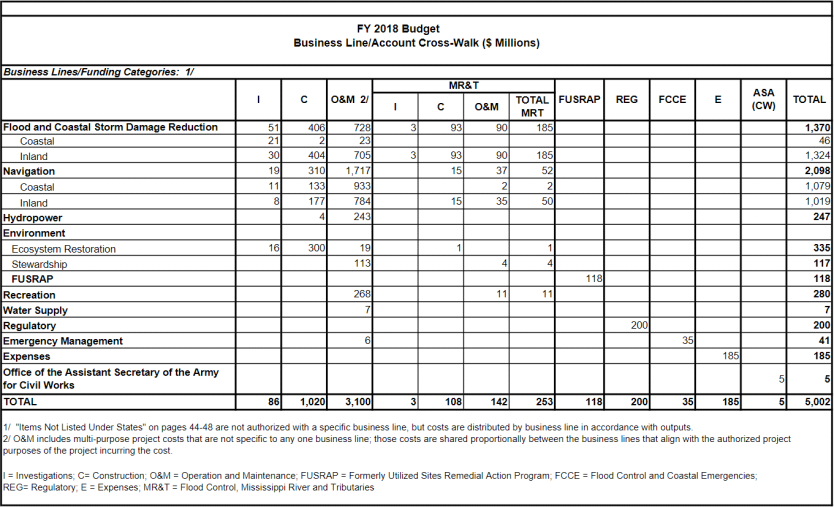

- Figure A-1. FY2018 Business Line/Account Crosswalk

Tables

Summary

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual

October 17, 2022

Appropriations Process

Anna E. Normand

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is an agency within the Department of Defense

Analyst in Natural

with both military and civil works responsibilities. The agency'’s civil works activities consist

Resources Policy

largely of the planning, construction, and operation of water resource projects to maintain

navigable channels, reduce the risk of flood and storm damage, and restore aquatic ecosystems.

Nicole T. Carter

Congress directs USACE'’s civil works activities through authorization legislation, annual and supplemental appropriations, and oversight.

Specialist in Natural

supplemental appropriations, and oversight.

Resources Policy

Unlike federal funding for highways and municipal water infrastructure, the majority ofmost federal funds provided to USACE are not distributed by formula to states or through competitive grant

programs. Instead, USACE generally is directly engaged in the planning and construction of projects. The majority of the agency'’s appropriations are used to perform work on geographically specific studies and congressionally authorized projects. Between FY2010 and FY2020FY2008 and FY2022, USACE discretionary appropriations, typically funded through Title I of annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts, have ranged from $4.72 billion in FY2013 to $7.65 8.34 billion in FY2020FY2022. Congress also hashas also provided USACE with emergency supplemental appropriations, most often as part of flood response and recovery efforts (see CRS In Focus IF11435, Supplemental Appropriations for Army Corps Flood Response and Recovery, for more information).

USACE'IF11945, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Supplemental Appropriations for more information).

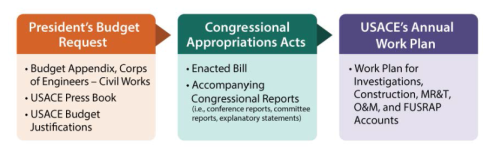

For the last decade, USACE’s annual appropriations process generally involveshas involved three major milestones: the President's ’s budget request, congressional deliberation and enactment of appropriations, and Administration development of a USACE work plan. Each of the milestones is accompanied by various documents, such as USACE budget justifications, congressional conference reports, and USACE work plans.

Figure 1. Appropriations Process Milestones for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Source: Congressional Research Service.

The process begins for an upcoming fiscal year with the submission of the President’s budget request, typically in early February; that is, the request for a fiscal year is submitted roughly eight months before the start of that fiscal year. The request’s appendix includes requested |

|

Notes: MR&T = Mississippi Rivers and Tributaries. O&M = Operation and Maintenance. FUSRAP = Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program. |

The process begins with the release of the President's budget request, typically in early February. The request's appendix includes funding levels for different USACE accounts (e.g., Investigations, Construction, Operation and Maintenance). USACE also releases more detailed documents (i.e., press book, budget justifications) providing information on the projects that the request would fund. Congress may consider the President'’s budget request, Member requests (e.g., Community Project Funding [CPF] and Congressional Directed Spending [CDS] requests), s budget request, stakeholder interests, and other factors when creating an annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill and its USACE civil works title. In reports accompanying appropriations bills, Congress provides direction to USACE on how to allocate enacted appropriations to various USACE activities and types of projects, including funding of CPF/CDS studies and projects. In the months following enactment, the Administration develops a work plan to allocate additional funding to specific studies and projects that aligns with congressional direction.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 2 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 18 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 19 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

USACE Primer .......................................................................................................................... 1

Annual Congressional Appropriations Process for USACE Funding ............................................. 2

President’s Budget Request ....................................................................................................... 4 Annual Congressional Appropriation Acts ................................................................................ 5

Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending ..................................... 8 Additional Funding ............................................................................................................. 9 New Starts ......................................................................................................................... 10

Agency Work Plan ................................................................................................................... 11

Figures Figure 1. Appropriations Process Milestones for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers .................... 2 Figure 2. Appropriations Process Timeline, FY2020-FY2022 ........................................................ 4 Figure 3. Budget Request and Annual Appropriations for USACE Civil Works, FY2008-

FY2022 ......................................................................................................................................... 6

Figure 4. Percent of USACE Annual Appropriations by Account, FY2008-FY2022 ..................... 8 Figure 5. USACE Annual Appropriations for Individual Studies and Projects, FY2012-

FY2022 ....................................................................................................................................... 10

Figure 6. Percent of USACE Annual Appropriations by Business Line, FY2008-FY2022 .......... 12

Figure A-1. FY2022 Enacted Annual Appropriations Business Line/Account Crosswalk ........... 14

Tables Table 1. USACE Civil Works Account Descriptions and Annual Appropriations, FY2020-

FY2022 ......................................................................................................................................... 6

Table B-1. Additional Funding Categories and Amounts .............................................................. 15

Appendixes Appendix A. USACE Business Line/Account Crosswalk ............................................................. 13 Appendix B. Additional Funding Categories and Amounts .......................................................... 15

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 16

Congressional Research Service

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Introduction . In the months following enactment, the Administration develops a work plan that adheres to congressional direction regarding the priorities for the funding provided above the requested amount (e.g., $2.7 billion for 26 categories of USACE activities in FY2020) and the number of new starts (e.g., six new studies and six new construction projects using FY2020 appropriations).

Some USACE-related topics repeatedly arise in congressional appropriations deliberations For example, Congress often considers how to address the increasing maintenance needs of USACE's aging infrastructure, stakeholder demand for USACE projects, and the number of finalized project studies awaiting construction. Issues for Congress also may include the distribution of appropriations (e.g., activity type, new starts, and geographic distribution) and the level of discretion Congress provides the Administration in allocating USACE's funding in the work plan.

Introduction

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is an agency within the Department of Defense with both military and civil works responsibilities. Congress directs USACE'’s civil works activities through authorization legislation, annual and supplemental appropriations, and oversight activities.1 This report summarizes USACE'’s annual discretionary appropriations for civil works activities, which typically are funded through Title I of annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts. First, the report introduces USACE and its funding. Second, it summarizes2 In particular, the report focuses on the appropriations process through discussions of three major milestones: President'’s budget request, congressional appropriations process, and annual USACE work plan. Third, the report provides a brief discussion of trends and policy questions related to USACE annual appropriations.

USACE Primer

A military Chief of Engineers commands USACE'’s civil and military operations. The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works (ASACW) provides civilian oversight of USACE. The agency'agency’s responsibilities are organized into eight geographically based divisions, which are further divided into 38 districts.1

3

As part of USACE'’s civil works activities, Congress has authorized and appropriated funds for the agency to perform the following:

-

water resource projects for maintaining navigable channels and harbors, reducing

risk of flood and storm damage, and restoring aquatic ecosystems, among other purposes;

-

environmental infrastructure assistance;

2 - 4 regulation of activities affecting certain waters and wetlands activities;

3 and - 5

1 For a primer and resources on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer’s (USACE’s) civil works activities, see CRS Insight IN11810, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Civil Works: Primer and Resources, by Anna E. Normand and Nicole T. Carter.

2 For more information on the Energy and Water appropriations acts, see CRS Report R46857, Energy and Water Development: FY2022 Appropriations, by Mark Holt, Corrie E. Clark, and Anna E. Normand.

3 A USACE division map and district links are available at https://www.usace.army.mil/Locations.aspx. Districts and divisions perform both military and civil works activities and are led by Army officers. The lead officer typically is in a district or division leadership position for three years.

4 Since 1992, Congress has authorized, and in most years funded, USACE assistance with planning, design, and construction of municipal drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects in designated communities, counties, and states (broadly known as environmental infrastructure, or EI). USACE’s EI assistance supports publicly owned and operated facilities, such as distribution and collection works, stormwater collection, recycled water distribution, and surface water protection and development projects. For more information on EI assistance, see CRS Report R47162, Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Environmental Infrastructure (EI) Assistance: Authorities, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Anna E. Normand.

5 USACE’s regulatory responsibilities for navigable waters extend to issuing permits for private actions that may affect navigation, wetlands, and other waters of the United States. Prominent among these responsibilities is USACE administration of §404 of the Clean Water Act. For more information on these permitting responsibilities, see CRS In Focus IF11339, Waters of the United States (WOTUS): Repealing and Revising the 2015 Clean Water Rule, by Laura Gatz and Stephen P. Mulligan; and CRS Report R44880, Oil and Natural Gas Pipelines: Role of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, by Nicole T. Carter et al.

Congressional Research Service

1

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

remediation of sites involved in the development of U.S. nuclear weapons from

remediation of sites involved in the development of U.S. nuclear weapons fromthe 1940s through the 1960s, administered under the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP).4

USACE Funding

From FY2010 to FY2020, Congress provided USACE with appropriations ranging from $4.72 billion in FY2013 to $7.65 billion in FY2020;6 and

the Corps Water Infrastructure Financing Program (CWIFP) funded through the

Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Program (WIFIP) account.7

Annual Congressional Appropriations Process for USACE Funding Congress generally funds USACE civil works through Title I of annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts. Unlike federal funding for highways and municipal water infrastructure, the majority of federal funds provided to USACE are not distributed by formula to states or through competitive grant programs. Instead, USACE generally expends the appropriations on its congressionally authorized water resource projects.58 That is, the majority of USACE'USACE’s appropriations are for the planning, construction, and operation of the agency'’s water resource projects, such as multipurpose dams and commercial navigation improvements along coasts and inland waterways.

Congress generally funds USACE civil works through Title I of annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts. Each year, some USACE projects receive construction funds; however, many authorized USACE construction projects have not been federally funded for years after their authorization.9 In addition to funding the agency'’s water resource activities, Congress provided $100 millionhas provided funding to USACE for environmental infrastructure assistance activities, $210 million for CWIFP, USACE regulatory activities, and FUSRAP.

Most USACE activities require a nonfederal sponsor to share some portion of project costs. For some project types (e.g., levees), nonfederal sponsors are required to perform operation, 6 The Atomic Energy Commission established the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) in 1974 under the Atomic Energy Act (42 U.S.C. §§2011 et seq.) to investigate the need for remediation at privately owned or operated sites that supported the development of U.S. nuclear weapons from the 1940s to the 1960s. The Department of Energy (DOE) assumed administration of FUSRAP, pursuant to the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-91). The Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act, 1998 (P.L. 105-62) authorized the transfer of 21 FUSRAP sites where remediation was not yet complete from DOE to USACE. DOE retained responsibility for the long-term stewardship of 25 FUSRAP sites where remediation was complete and responsibility for the remediation and long-term stewardship of federal facilities involved in the development of U.S. nuclear weapons. USACE later became responsible for the remediation of eight other sites added to FUSRAP. After USACE completes the remediation of a site, jurisdiction is transferred back to DOE for long-term stewardship. For information on the status of FUSRAP, see https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Environmental/FUSRAP.aspx. Although this report references USACE’s FUSRAP and regulatory accounts, the report’s discussion focuses on annual appropriations for the agency’s water resource projects. Lance Larson, CRS Analyst in environmental policy, covers FUSRAP activities.

7 For more information, see CRS Insight IN12021, Corps Water Infrastructure Financing Program (CWIFP), by Nicole T. Carter.

8 Congress generally authorizes USACE water resource studies and construction projects prior to funding them. For information on the authorization process, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

9 According to USACE,USACE regulatory activities, and $200 million for FUSRAP in FY2020.6

Each year, some USACE projects receive construction funds; however, many authorized USACE construction projects have not been federally funded for years after their authorization. That is, Congress has authorized construction projects and rehabilitation and repair work that totals an estimated $96 billion: approximately $32 billion of authorized but unfunded projects and approximately $64 billion of rehabilitation and repair work (e.g., for dam safety).7totaled an estimated $110 billion in 2021. Testimony of USACE Chief of Engineers Scott A. Spellmon at U.S. Congress, House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment, President Biden’s Fiscal Year 2022 Budget Request: Agency Policies and Perspectives (Part I), 117th Cong., 1st sess., June 24, 2021. This is often referred to as the agency'’s construction backlog. Since that June 2021 estimate, Congress has provided funding for USACE construction projects in FY2022 annual appropriations and in supplemental appropriations acts. As of September 2022, USACE had not updated its 2021 construction backlog estimate (information provided to CRS by USACE on September 20, 2022).

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 7 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

maintenance, repairs, replacement, and rehabilitation of the works once construction is complete.10 Some USACE activities also are supported by two navigation trust funds, as described in the text box titled “Navigation Funding and Navigation Trust Funds.”

Navigation Funding and Navigation Trust Funds

Two congressionally authorized trust funds support U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) navigation activities. These funds cover a portion of the amount that USACE spends on navigation improvements annual y.

The Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF; 26 U.S.C. §9505) pays for investments in federal navigation coastal channel and harbor operation and maintenance (O&M). The HMTF receives revenues from taxes on waterborne commercial cargo imports, domestic cargo, and cruise ship passengers at federally maintained ports.

The Inland Waterways Trust Fund (IWTF; 26 U.S.C. §9506) receives proceeds of a tax on barge fuel for vessels engaged in commercial transport on 27 designated inland and intracoastal waterways. Since 1986 (with exceptions that are noted below), Congress generally has required that construction and major rehabilitation for inland and intracoastal waterways be paid for 50% from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury and 50% from the IWTF.

Both trust funds require annual appropriations language instructing that funds for eligible activities are to be drawn from the trust fund accounts. As a result, funds drawn from the IWTF and the HMTF have historically fallen within congressional budget caps on discretionary spending and procedural limits for allocations of budget authority for a fiscal year (often referred to as 302(b) allocations). The HMTF had a balance of nearly $10 bil ion at the start of 2020, as funds drawn from the fund had been less than amounts accrued. In the CARES Act (P.L. 116-136) and the Water Resources Development Act of 2020 (WRDA 2020; Division AA of P.L. 116-260), Congress provided for an accounting change that makes certain amounts of discretionary spending from the HMTF not count toward the discretionary budget cap. For FY2022 appropriations, HMTF provided $2.049 bil ion toward eligible USACE O&M of which roughly $2.038 bil ion did not count toward the budget cap. In total, USACE used $2.839 bil ion of FY2022 annual appropriation toward studies, construction, and O&M of federal navigation coastal channels and harbors. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58) funded harbor maintenance at $2.000 bil ion for FY2022, $1.000 bil ion for FY2023, and $1.000 bil ion for FY2024; the IIJA did not require an HMTF contribution toward these costs. Congress authorized a $0.09 per gallon increase in the fuel tax, resulting in a barge fuel tax of $0.29 per gallon beginning in April 2015. Since FY2014, Congress has reduced the IWTF-required portion of funds for certain waterway construction projects, thereby increasing the funds for inland waterway construction that come from the General Fund. Congress in WRDA 2020 decreased the IWTF contribution from 50% to 35% for any inland navigation construction project receiving construction appropriations during any fiscal year from FY2021 through FY2031 until the project’s construction is complete. As part of annual appropriations provided for FY2022, the IWTF paid for $72 mil ion of the total $205 mil ion USACE used for inland waterway construction. In total, USACE used $1.293 bil ion of FY2022 annual appropriations for studies, construction, and O&M of inland and intracoastal waterways. The IIJA also funded inland waterway construction at $2.500 bil ion; the IIJA did not require an IWTF contribution toward these costs.

For the last decade, the annual appropriations process generally has involveds construction backlog. The backlog includes much more authorized work than can be accomplished with annual construction appropriations, which has ranged from $2.1 billion to $2.7 billion annually during FY2018 through FY2020. A subset of the projects in the backlog are funded in a given year, and many projects in the backlog receive no funds for years.

Congress also has provided USACE with emergency supplemental appropriations in some years, typically in response to floods. Most of these supplemental funds are directed to repairing damage to existing USACE facilities, paying for flood fighting and repair of certain levees and dams maintained by nonfederal entities, and constructing new riverine and coastal flood control improvements.8 For more information on supplemental funds for USACE and associated congressional direction, see CRS In Focus IF11435, Supplemental Appropriations for Army Corps Flood Response and Recovery, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

In addition to federal funding, most USACE activities require a nonfederal sponsor to share some portion of project costs. For some project types (e.g., levees), nonfederal sponsors are required to perform operation, maintenance, repairs, replacement, and rehabilitation of the works once construction is complete. For more information on nonfederal cost-share requirements, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

Annual Appropriations Process

The annual appropriations process generally involves three major milestones: President'the President’s budget request, congressional deliberation and enactment of appropriations, and Administration development of a USACE work plan (see Figure 1)2). The process begins with the release of the President'’s budget request, typically in early February (i.e., roughly eight months before the start of the fiscal year addressed by the request), although itthe request is sometimes delayed.911 Congress may consider the President'’s budget request, Member requests (including Community Project Funding [CPF] and Congressional Directed Spending [CDS] requests), s budget request, stakeholder interests, and other factors when creating an annual Energy and Water Development appropriations bill that includes USACE civil works activities. The length of

10 For more information on nonfederal cost-share requirements, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

11 Sometimes the President is delayed in releasing the request in early February. For example, in the past, the request has been delayed during the first year of a new Administration, such as for the FY2022 budget request.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 7

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

the congressional appropriations process varies from year to year, as shown inin Figure 12. Following enactment of the Energy and Water Development bill, the Administration develops a USACE work plan, which identifies the amount of based on instructions by Congress to allocate additional funding provided to specific studies and projects. The following sections describe these major milestones in more detail.

|

|

Notes: MR&T = Mississippi Rivers and Tributaries. O&M = Operation and Maintenance. FUSRAP = Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program. |

President'. Notes: Orange = month that the President’s Budget is delivered to Congress; Green = month that Congress enacted appropriations act; Purple = month that USACE releases annual work plan.

Supplemental Appropriations for USACE

Congress has occasionally also provided USACE with emergency supplemental appropriations. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58) provided $17.1 bil ion for infrastructure investments spanning USACE’s navigation, flood, and aquatic ecosystem restoration activities. While the majority of USACE’s IIJA funding became available for USACE to apply to projects in FY2022, a portion of the funds were provided as appropriations available starting in FY2023 and FY2024. While the IIJA focused on infrastructure investment, Congress at times uses supplemental appropriations to fund USACE’s response to floods. Most of these flood-related supplemental funds are directed to repairing damage to existing USACE facilities, paying for flood fighting and repair of certain levees and dams maintained by nonfederal entities, and constructing new riverine and coastal flood control improvements. Notes: For more information, see CRS Insight IN11723, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Funding for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Civil Works: Policy Primer, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand; and CRS In Focus IF11945, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Supplemental Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

President’s Budget Request s Budget Request

The President'’s budget request for USACE typically is forincludes funding at the account level (i.e., Investigation, Construction, and Operation and Maintenance), as shown in the appendix to the President'President’s FY2020 budget request.1012 The agency'’s budget justification includes more detailed

12 The portion of the appendix of the President’s FY2022 budget request related to USACE is available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BUDGET-2022-APP/BUDGET-2022-APP-1-20.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

s budget justification includes more detailed information regarding the request by providing information for specific activities, such as the level of funding requested for particular USACE studies and construction projects.1113 USACE also publishes a summary of this information in a document it refers to as the press bookpress book. The press book shows the requested funding for USACE projects for each state and identifies how the President'President’s requests for various accounts are distributed across the agency'’s business lineslines (i.e., types of activities, such as navigation, restoration, and recreation) in a crosswalk (see Appendix A).12

.14

In recent years, the executive branch has used various metrics, including benefit-cost ratios and other performance criteria, to identify which projects and activities to include in the President's ’s request. For example, to identify operation and maintenance investments, the Administration's ’s budget development guidance has used risk assessments, which consist of an evaluation of an existing project'’s condition and the consequences of reduced project performance (i.e., the consequence of not making an investment). USACE budget development guidance describes these metrics and other aspects of the budget development process each year.13 Recent Administrations15 Some Administrations’ requests also have limited funding for new starts to focus on completing existing projects and address aging infrastructure.

Annual Congressional Appropriation Acts From FY2008 to FY2022, Congress provided USACE with annual appropriations ranging from $4.72 billion (in FY2013) to $8.34 billion (in FY2022) in nominal dollars.16 projects and on actions to address aging infrastructure.

Congressional Appropriation Acts

As shown in Figure 23, since FY2006FY2008, Congress has appropriatedprovided more for USACE civil works annual appropriations than the President requested in all but one year. Figure 3 also shows a line illustrating the FY2008 through FY2021 annual appropriations in FY2021 dollars (i.e., the amounts have been inflation-adjusted to reflect 2021 as the base year).17 Figure 3 does not include supplemental appropriations in these fiscal years.

13 The detailed budget justification may be available the same day the President’s budget request is released or within a few weeks of the budget request’s release. USACE posts its budget justifications, along with other budget documents, at http://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Budget/.

14 Although some business line activities (e.g., navigation, flood damage reduction, restoration, recreation) are spread across accounts (e.g., Investigations, Construction, Operation and Maintenance), other business line activities and accounts are the same (e.g., FUSRAP, regulatory, expenses). The press book is published at http://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Budget/.

15 For example, see USACE, Civil Works Direct Program Development Policy Guidance, EC 11-2-225, March 2022, at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Users/182/86/2486/EC%2011-2-225.pdf. For more on benefit-cost ratios, see CRS Report R44594, Discount Rates in the Economic Evaluation of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Projects, by Nicole T. Carter and Adam C. Nesbitt.

16 The amounts discussed in this report are nominal unless otherwise stated. 17 When inflation-adjusted amounts are provided in this report, the appropriated amounts were adjusted to 2021 dollars using U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 1.1.9. FY2022 amounts were not adjusted.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Figure 3. Budget Request and Annual Appropriations for USACE Civil Works,

FY2008-FY2022

. In the text of enacted appropriations laws, Congress generally provides appropriations to USACE at the account level (see Table 1 for a description of the accounts and their FY2018 to FY2020 appropriations amounts). Accompanying appropriations reports (i.e., conference reports, committee reports, or explanatory statements), which sometimes are incorporated into law by reference, often identify specific USACE projects and programs to receive appropriated funds.

In addition to regular appropriations, Congress provided USACE with various emergency supplemental appropriations from FY2006 to FY2019. For example, Congress provided a total of more than $47 billion for flood fighting (e.g., construction of temporary levees) and flood recovery (e.g., construction of flood risk reduction in states and territories affected by flooding) over those years, as well as $4.6 billion for economic recovery as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). These supplemental appropriations are not shown in Figure 2.14

Table 1. USACE Civil Works Account Descriptions and Annual Appropriations, FY2018 to FY2020

Amounts adjusted to 2021 dol ars using U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 1.1.9.

In the text of enacted appropriations laws, Congress generally provides appropriations to USACE at the account level (see Table 1 for a description of the accounts and their FY2020-FY2022 appropriations amounts). Accompanying appropriations reports (i.e., conference reports, committee reports, or explanatory statements), which sometimes are incorporated into law by reference, often identify specific USACE studies, projects, and programs to receive appropriated funds (see section on “Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending”) and amounts of “additional funding” for USACE to allocate to studies and programs in a work plan (see section on “Additional Funding”).

Table 1. USACE Civil Works Account Descriptions and Annual Appropriations,

FY2020-FY2022

($ in millions, nominal)

Account

Description

FY2020

FY2021

FY2022

Investigations

Funds studies for authorized projects and

151

153

143

($ in millions, nominal)

|

Account |

Description |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

Investigations |

|

123 |

125 |

151 |

|

Construction |

|

2,085 |

2,183 |

2,681 |

|

Mississippi River and Tributaries (MR&T) |

|

425 |

368 |

375 |

|

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) |

|

3,630 |

3,740 |

3,790 |

|

Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (FCCE) |

|

35 |

35 |

35 |

|

Regulatory |

|

200 |

200 |

210 |

|

Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) |

Funds remedial activities at sites contaminated primarily as a result of the United States' early atomic weapons development program. |

139 |

150 |

200 |

|

General Expenses |

|

185 |

193 |

203 |

|

Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works; ASACW) |

|

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Total |

6,827 |

6,999 |

7,650 |

Sources: CRS, using enacted appropriations (P.L. 115-141; P.L. 115-244; P.L. 116-94); agency work plans at https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Budget/;116-94; P.L. 116-260; P.L. 117-103) and USACE, Civil Works Direct Program Development Policy Guidance, Fiscal Year 2020, EC 11-2-216225, March 20182022, at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerCirculars/EC_11-2-216.pdf?ver=2018-08-20-084953-930.

Note: Amounts do not include supplemental appropriations.

76/Users/182/86/2486/EC%2011-2-225.pdf. Notes: Amounts do not include supplemental appropriations. Totals might not sum because of rounding.

Generally, Congress provides the majority of USACE'’s funding to two accounts—the Construction account and the Operation and Maintenance (O&M) account. The O&M account has made up a growing portion of the agency'’s use of annual appropriations, as shown in Figure 34. Between FY2006 and FY2020FY2008 and FY2022, the O&M account increased from 3740% of USACE annual appropriations in FY2008 to 55% in FY2022.

Congressional Research Service

7

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Figure 4. Percent of appropriations in FY2006 and FY2007 to a high of 53% in FY2018 and FY2019.15

|

Navigation Trust Funds Two congressionally authorized trust funds support U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) navigation activities. The Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (HMTF; 26 U.S.C. §9505) pays for investments in federal navigation coastal channel and harbor operation and maintenance. The HMTF receives revenues from taxes on waterborne commercial cargo imports, domestic cargo, and cruise ship passengers at federally maintained ports. Since 1986, Congress generally has required that construction and major rehabilitation for inland waterways be paid for 50% from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury and 50% from the Inland Waterways Trust Fund (IWTF; 26 U.S.C. §9506). The IWTF receives proceeds of a tax on barge fuel for vessels engaged in commercial transport on 27 designated inland waterways. Both trust funds require annual appropriations language to draw on their balances. As a result, funds drawn from the IWTF and the HMTF historically have fallen within congressional budget caps on discretionary spending and procedural limits for allocations of budget authority for a fiscal year (often referred to as 302(b) allocations). The amount collected from the fuel tax since the mid-2000s has prevented the IWTF from supporting the level of construction sought by the waterway industry. In P.L. 113-295, Congress authorized a $0.09 per gallon increase in the fuel tax, resulting in a barge fuel tax of $0.29 per gallon beginning in April 2015. Since FY2014, Congress has reduced the IWTF-required portion of funds for certain waterway construction projects, thereby increasing the funds for inland waterway construction that come from the General Fund by more than $400 million. The IWTF's inability to support the level of construction on waterways included in Energy and Water appropriations acts without congressional adjustments to decrease the trust fund's role in funding some projects has raised the prospect of changes in inland waterway funding. For example, the Obama and Trump Administrations put forth proposals for new user fees in various budget requests. In FY2019, the IWTF was used to pay for $116 million of the total $1.25 billion in USACE costs for inland waterways, which consisted of $337 million in construction and $899 million in operation and maintenance. In contrast, the HMTF had developed a balance of nearly $10 billion at the start of 2020, as funds drawn from the fund have been less than amounts accruing to it. In the CARES Act (P.L. 116-136) in 2020, Congress provided for an accounting change that makes discretionary spending from the HMTF, in an amount up to the previous year's deposits (which were $1.769 billion in FY2019), not count toward budget caps. The provision takes effect the earlier of January 1, 2021, or the date of enactment of water resource authorizing legislation, and remains in effect thereafter. |

Additional Funding

For decades, Congress provided funding to USACE projects that were not included in the President's request until the House and Senate earmark moratoriums limited Congress's ability to select which site-specific projects would receive funding. Since the 112th Congress, in lieu of increasing funding for specific projects, Congress has provided additional funding for specified categories of work within some USACE budget accounts. That is, in recent appropriations cycles, Congress has included additional funding categories for various types of USACE projects (e.g., additional funding for inland navigation), along with directions and limitations on the use of these funds on authorized studies and projects. and projects. Recent levels of additional funding are shown in Figure 4. For example, Congress provided $2.69 billion more in P.L. 116-94 than the President'President’s request for FY2020. Of this $2.69 billion, $2.53 billion was identified as additional funding for 26 categories of USACE activities in four budget accounts (seesee Appendix B). While the 117th Congress reincorporated Member requests via CPF/CDS, the appropriations process still included additional funding in four USACE budget accounts, though at a lower amount and for less categories of activities than previous fiscal years (see Appendix B). For example, additional funding in FY2022 totaled $782 million, down from $2.25 billion in FY2021. Figure 5 shows USACE funding from FY2012 to FY2022 for individual studies and projects categorized by the amount Congress provided for (1) studies and projects as requested by the President’s budget request, (2) additional funding for USACE to allocate in a work plan, and (3) CPF/CDS items.

20 For continuing authorities program (CAP) funding, Congress provided an overall amount for each CAP. Any CPF/CDS projects under CAPs were then designated an allocation out of the total provided for the CAP. For more information on CAPs, see CRS In Focus IF11106, Army Corps of Engineers: Continuing Authorities Programs, by Anna E. Normand.

Congressional Research Service

9

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Figure 5. USACE Annual Appropriations for Individual Studies and Projects, FY2012-

FY2022

($ in billions, nominal)

Source: CRS, using conference reports for enacted appropriations for FY2012 and FY2014-FY2022. The FY2013 amount is a CRS estimate based on data in USACE, “Civil Works, FY2013 Work Plan,” 2013. Notes: Funding for Continuing Authorities Programs (CAPs) were not included in this analysis. Amounts shown do not include supplemental appropriations.

New Starts

USACE studies and construction projects selected to receive funding for the first time are referred to as new starts. Generally, the amount of existing authorizations and the rate of new study and construction authorizations exceed the rate of funding new study and construction projects. Budget requests from various Administrations have included requests for new studies or new construction projects, but some have not included any new starts (e.g., FY2018 and FY2019 budget requests). From FY2014 through FY2021, Congress specified in each annual appropriations bill the number of new studies and construction projects that USACE could allocate using additional funding in a work plan. For example, Congress directed USACE to use FY2020 annual appropriations to initiate a maximum of six new studies and six new construction projects.21 Conversely, with FY2022 annual appropriations, Congress recommended 18 new studies and 4 new construction projects in the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 117-103,

21 In the FY2020 explanatory statement, Congress provided direction for the type of studies and construction projects to fund as new starts. For studies, Congress directed one multipurpose watershed study to address coastal resiliency, one for environmental restoration, one for flood and storm damage reduction, one for either flood and storm damage reduction or environmental restoration, and two for navigation. For construction, Congress directed two for navigation and two for environmental restoration, including the one new construction start for an Everglades project that the Administration requested in an amendment to its budget request. The other two new construction starts could be flood and storm damage reduction, environmental restoration, or multipurpose projects. Although Congress allowed USACE to initiate two new environmental infrastructure assistance activities using FY2020 appropriations, the agency chose not to fund any new environmental infrastructure starts in that fiscal year.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

which included new starts requested by the Administration and CPF/CDS requests.22 In the explanatory statement, USACE was instructed not to fund additional new starts with additional funding, as was the practice in previous fiscal years.

Agency Work Plan Since FY2012, Congress has directed USACE to produce an annual work plan describing how additional funds are to be allocated at the project level. For example, in FY2022, the explanatory statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (P.L. 117-103), called for USACE, within 60 days after enactment of the appropriations bill, to issue a work plan that includes the specific amount of additional funding to be allocated to each project.23 The Administration develops the work plan, which typically consists of tables that list the projects, the amount of additional funding that each project is to receive, and a one- or two-sentence description of what USACE plans to accomplish with the funds for the project.24 For projects not in the budget justifications that accompanied the President’s budget request, the information included in the work plan may be the extent of the Administration’s public explanation of the project-level work to be accomplished during a fiscal year.25 Following transmission of the work plan to Congress, annual appropriations may be analyzed across business lines as shown in Figure 6.

22 In USACE supplemental appropriations acts, unlike in annual appropriations, Congress often does not limit the initiation of new USACE studies and construction projects. For example, USACE utilized IIJA funds to start 7 new studies and 31 new construction projects. Information provided to CRS by USACE on July 12, 2022.

23 Explanatory statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022, Congressional Record, vol. 168, no. 42, book III (March 9, 2022), pp. H2185, at https://www.congress.gov/117/crec/2022/03/09/168/42/CREC-2022-03-09-bk3.pdf.

24 Three executive branch entities typically develop the work plan: USACE, Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works), and the Office of Management and Budget.

25 USACE typically provides no details in the work plan identifying which CAP projects are funded by appropriations.

Congressional Research Service

11

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Figure 6. Percent of USACE Annual Appropriations by Business Line, FY2008-

FY2022

Source: CRS, using annual account and budget information from CRS correspondence with USACE. Notes: WIFIA = Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act; ASA = Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works); FUSRAP = Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program. “Environment” includes ecosystem restoration and environmental stewardship. “Other Civil Works” includes business lines such as water supply, hydropower, recreation, and emergency management. “Other Civil Works” also includes environmental infrastructure, although USACE does not consider environmental infrastructure as a business line. Amounts shown do not include supplemental appropriations.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 9 link to page 17 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Annual Appropriations Process

Appendix A. USACE Business Line/Account Crosswalk Appendix B). In Figure 4, categories are aggregated into navigation activities, flood risk reduction activities, and other authorized project purposes (e.g., environmental restoration). Since FY2014, Congress also has specified in each appropriations bill the number and types of studies and projects to be selected to receive funding for the first time (referred to as new starts). For example, Congress directed USACE to use FY2020-enacted funding to initiate a maximum of six new studies and six new construction projects.16

($ in billions, nominal) |

|

Source: CRS, using conference reports for enacted appropriations for FY2012 and FY2014 to FY2020. The FY2013 amount is a CRS estimate based on data in USACE, "Civil Works, FY2013 Work Plan," 2013.

|

Agency Work Plan

Since FY2012, Congress has directed USACE to produce an annual work plan describing how funds will be allocated at the project level. For example, in FY2020, the explanatory statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), called for USACE, within 60 days after enactment of the appropriations bill, to issue a work plan that includes the specific amount of additional funding to be allocated to each project.17 The Administration develops the work plan, which typically consists of tables that list the projects, the amount of additional funding that each project is to receive, and a one- or two-sentence description of what USACE is to accomplish with the funds for the project.18 For projects not in the budget justifications that accompanied the President's budget request, the information included in the work plan may be the extent of the Administration's public explanation of the project-level work to be accomplished during the fiscal year.19

During the FY2014 to FY2019 period, investments in some USACE business lines increased and investments in other business lines decreased.20 As shown in Figure 5, Congress provided year-to-year increases in funding for navigation, which exceeded annual navigation spending in the FY2006 to FY2013 period. In contrast, annual funding for the environment (i.e., environmental restoration and environmental stewardship business lines) was less from FY2014 to FY2019 (ranging from $470 million to $591 million annually) compared with funding in the earlier FY2006 to FY2012 period, which ranged from $609 million to $680 million annually.21

Funding for flood risk reduction has remained around 30% of the total annual appropriations for most of the years in the FY2006 to FY2019 period shown in Figure 5. The majority of the annual flood-related funds shown in Figure 5 are for riverine flood risk reduction activities. For example, of the construction funds for flood risk reduction provided in annual appropriations acts for FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019, funding for coastal storm damage reduction represented 11%, 9%, and 7%, respectively.22 The explanatory statement accompanying the FY2020 appropriations act (P.L. 116-94) includes the following statement: "Within the flood and storm damage reduction mission, the Corps is urged to strive for an appropriate balance between inland and coastal projects."23

Of the previously mentioned $47 billion in flood-related supplemental appropriations from FY2006 to FY2019, Congress provided around $24 billion for construction of flood risk reduction projects. Congress provided almost $15 billion of the $47 billion to the Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (FCCE) account for flood fighting and repair of certain nonfederal flood risk reduction projects during the FY2006 to FY2019 period. In contrast, annual appropriations for FCCE generally have been less than $35 million and used for emergency response training and preparedness (Table 1).

($ in billions, nominal) |

|

|

Source: CRS, using annual account and budget information from CRS correspondence with USACE. Notes: ASA = Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works); FUSRAP = Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program. "Environment" includes ecosystem restoration and environmental stewardship. "Other Civil Works" includes business lines such as water supply, hydropower, recreation, and emergency management. "Other Civil Works" also includes environmental infrastructure, although USACE does not consider environmental infrastructure as a business line. USACE has not released business line information for FY2020. Amounts shown do not include supplemental appropriations, which represent $47 billion for flood fighting and recovery for FY2006 to FY2019 and $4.6 billion for economic recovery through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). |

Trends and Policy Questions

Congress may consider the following trends and policy questions when determining future appropriations and funding allocation language directed to USACE.

Shift to Administration-Developed Work Plans

Since earmark moratorium policies were introduced in the 112th Congress, Congress has provided annual appropriations above the President's request to fund various additional categories of work (see Figure 4 for funding levels from FY2012 to FY2020). The Administration follows congressional guidance regarding priorities, new starts, and other matters, in part, to develop post-enactment agency work plans that specify which projects are to receive the additional funding. Unlike the justification documents that accompany the President's budget request, the Administration limits the project-level details in the work plan to a few sentences per project. Potential policy questions related to the shift to Administration-developed work plans include the following:

- What is the effect on congressional oversight when the USACE work plan provides fewer project-level details than the budget request?

- As Congress debates the limits on congressionally directed spending (or earmarks), will considerations include the type of direction Congress can provide USACE on the use of additional funding?

- How might Congress address differences between its priorities and the Administration's priorities for USACE in future fiscal years' appropriations?

According to USACE, in early FY2020, there was a construction backlog of $96 billion, including projects with signed Chief's reports (i.e., reports recommending new projects for congressional construction authorization), dam modifications, and deferred maintenance.24 At the FY2021 budget release press conference, the Chief of Engineers stated that since the enactment of the last Water Resources Development Act (Title I of America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018; P.L. 115-270), he had signed 19 Chief's reports, representing over $9 billion in proposed construction; he also said he anticipated signing another 19 Chief's reports by the end of CY2020. If Congress authorizes these projects, the construction backlog would likely continue to increase more quickly than construction would progress using available USACE appropriations. For example, Congress appropriated $2.2 billion in FY2019 and $2.7 billion in FY2020 for the Construction account and required five new construction starts in FY2019 and six new construction starts in FY2020. Potential policy questions related to the construction backlog include the following:

- How might Congress address the national demand for water resource infrastructure projects, in part illustrated by the USACE construction backlog?

- How might Congress address stakeholder interest in new starts and identify a path to construction for authorized but unfunded USACE projects?

Shift to Operation and Maintenance

U.S. water infrastructure is aging; the majority of the nation's dams, locks, and levees are more than 50 years old. An increasing share of USACE's annual discretionary appropriations goes to O&M activities, including activities to maintain USACE-constructed water infrastructure (see Table 1 for description of activities funded by the O&M account). The O&M account increased from 37% of USACE annual appropriations in FY2006 and FY2007 to a high of 53% in FY2018 and FY2019. The following is a potential policy question related to the shift toward more annual appropriations being used to for O&M:

- How might Congress address the funding of aging USACE infrastructure, while also meeting the other demands for agency projects and funds?

As discussed in the box titled "Navigation Trust Funds," in P.L. 116-136, Congress altered how some Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund spending is accounted for in relation to budget caps. Congress, as recently as for FY2020 appropriations in P.L. 116-94, has reduced the funds to be derived from the Inland Waterways Trust Fund for some projects to allow more inland waterway construction projects to proceed. The Administration has proposed identifying additional ways for waterway interests to contribute to the costs of inland waterway construction and O&M. Potential policy questions related to funding navigation actives include the following:

- How might Congress address the interest of the inland waterways industry and its stakeholders in spending on waterway construction that exceeds the Inland Waterways Trust Fund's ability to cover 50% of the construction costs?

- Will the anticipated changes to Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund accounting toward budget caps and allocations result in congressional adjustments to the annual appropriations levels for USACE or other federal agencies' appropriations?

Congress has directed around 30% of USACE's annual appropriations to support flood risk reduction activities, with around 90% of these funds, in most years, supporting riverine flood risk reduction. In addition, as previously noted, the FCCE account typically receives annual appropriations around $35 million, and its flood response and repair activities are primarily funded through supplemental appropriations. Potential policy questions related to funding flood risk reduction actives include the following:

- Will Congress or the Administration address the balance between inland and coastal projects referenced in the explanatory statement accompanying USACE's FY2020 appropriations in P.L. 116-94?

- What are the consequences of primarily using supplemental appropriations to fund FCCE activities, including repair of damaged nonfederal levees?

As previously noted, appropriations for USACE's environmental activities in recent years have been less than in the late 2000s. Annual funding for the environment was less from FY2014 to FY2019 (ranging from $470 million to $591 million) compared with funding in the earlier FY2006 to FY2012 period, which ranged from $609 million to $680 million annually. Postponed investments in aquatic ecosystem restoration may result in missed opportunities to attenuate wetlands loss and realize related ecosystem benefits. Potential policy questions related to the funding of USACE environmental actives include the following:

- What are the consequences of the current level and distribution of USACE restoration funding?

Appendix A.

USACE Business Line/Account Crosswalk

Congress appropriates funding to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) for its civil works activities at the account level (e.g., Investigation, Construction, and Operation and Maintenance [O&M]). Table 1 provides a description of each account. Activities funded in these accounts are categorized by business lines based on the type of activities. Whereas some business line activities (e.g., navigation, flood damage reduction, restoration, recreation) are spread across accounts (e.g., Investigations, Construction, O&M), other business line activities are exclusive to one account with the same name (e.g., Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program, regulatory, expenses). Along with the President'’s budget request, USACE publishes a press book that identifies in a crosswalk how the President'’s requests for various accounts are distributed across the agency'’s business lines. For example, Figure A-1 shows the crosswalk for the FY2018 President's budget request for USACEFY2022 enacted annual appropriations; the columns are the accounts, and the rows are the business lines. Following enactment of appropriations and work plan development, USACE typically also calculates the level of funding for each business line.

|

|

|

Appendix B.

Additional Funding Categories and Amounts

Since the 112th Congress, Congress has provided additional funding for specific categories of work within some USACE budget accounts (e.g., Investigations, Construction, O&M, Mississippi River and Tributaries). Table B-1 shows the additional funding Congress provided in FY2018 to FY2020 for 26 categories of USACE activities across four budget accounts. Congress directed USACE to produce a work plan no later than 60 days after enactment of the appropriations bill, allocating these additional funds to projects meeting the criteria of the categories and any other direction provided in the explanatory statement or conference report. Some states received funding for larger projects, whereas others received funding for less extensive work. For example, under the Construction account, the work plan allocated $100 million or more per state in additional funding to 10 states―Alabama, California, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, North Dakota, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas―in at least one of FY2018, FY2019, or FY2020; the work plans over that same period included between $1 million and $7 million annually per state for other states (e.g., Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah).

|

Account |

Category |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

Navigation |

||||

|

Investigations |

Unspecified Navigation |

6.6 |

10.0 |

7.0 |

|

Investigations |

Coastal and Deep Draft |

5.0 |

9.0 |

6.0 |

|

Investigations |

Inland |

5.0 |

5.5 |

9.8 |

|

Construction |

Unspecified Navigation |

337.1 |

509.0 |

377.9 |

|

Construction |

Inland Waterways Trust Fund Revenues |

112.0 |

110.8 |

75.6 |

|

Construction |

Regional Dredge Demonstration Program |

― |

― |

377.7 |

|

MR&T |

Dredging |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Unspecified Navigation |

24.3 |

23.9 |

40.2 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Deep-Draft Harbor and Channel |

341.4 |

475.0 |

532.5 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Donor and Energy Transfer Ports |

40.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Inland Waterways |

30.0 |

40.0 |

55.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Small, Remote, or Subsistence Navigation |

50.0 |

54.0 |

65.0 |

|

Flood and Storm Damage Reduction |

||||

|

Investigations |

Unspecified Flood and Storm Damage Reduction |

6.5 |

6.6 |

6.0 |

|

Investigations |

Flood Control |

5.0 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

|

Investigations |

Shore Protection |

2.0 |

2.0 |

4.0 |

|

Construction |

Unspecified Flood and Storm Damage Reduction |

180.0 |

150.1 |

150.0 |

|

Construction |

Flood Control |

188.0 |

150.0 |

170.0 |

|

Construction |

Shore Protection |

50.0 |

55.0 |

50.2 |

|

MR&T |

Unspecified Flood and Storm Damage Reduction |

117.1 |

73.1 |

105.1 |

|

Other Authorized Project Purposes |

||||

|

Investigations |

Unspecified |

3.0 |

6.5 |

6.0 |

|

Investigations |

Environmental Restoration or Compliance |

1.5 |

3.8 |

17.6 |

|

Construction |

Unspecified |

70.0 |

108.0 |

85.0 |

|

Construction |

Environmental Restoration or Compliance |

35.0 |

50.0 |

100.0 |

|

Construction |

Environmental Infrastructure |

70.0 |

77.0 |

100.0 |

|

MR&T |

Unspecified |

50.0 |

40.0 |

50.0 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

Unspecified |

24.0 |

50.0 |

85.0 |

Source: Category and amounts are based on data from conference reports and explanatory statements for enacted appropriations.

Notes: MR&T = Mississippi River and Tributaries. The explanatory statements provide some further direction on use of additional funds (e.g., for additional construction funding in FY2020, USACE was to allocate not less than $40.6 million to projects with riverfront development components). Congress first provided dedicated additional funding to the Regional Dredge Demonstration Program in FY2020.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

A U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) division map and district links are available at http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/Locations.aspx. Districts and divisions perform both military and civil works activities and are led by Army officers. The lead officer typically is in a district or division leadership position for three years. |

| 2. |

Since 1992, Congress has authorized, and in most years funded, USACE assistance with planning, design, and construction of municipal drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects in designated communities, counties, and states (broadly known as environmental infrastructure, or EI). USACE's EI assistance supports publicly owned and operated facilities, such as distribution and collection works, stormwater collection, recycled water distribution, and surface water protection and development projects. No Administration has ever requested authorization or appropriations for USACE to perform EI assistance. For more information on EI assistance, see CRS In Focus IF11184, Army Corps of Engineers: Environmental Infrastructure Assistance, by Anna E. Normand. |

| 3. |

USACE's regulatory responsibilities for navigable waters extend to issuing permits for private actions that may affect navigation, wetlands, and other waters of the United States. Prominent among these responsibilities is USACE administration of §404 of the Clean Water Act. For more information on these permitting responsibilities, see CRS In Focus IF11339, Waters of the United States (WOTUS): Repealing and Revising the 2015 Clean Water Rule, by Laura Gatz and Stephen P. Mulligan; and CRS Report R44880, Oil and Natural Gas Pipelines: Role of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, by Nicole T. Carter et al. |

| 4. |

The Atomic Energy Commission established the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) in 1974 under the Atomic Energy Act (42 U.S.C. §§2011 et seq.) to investigate the need for remediation at privately owned or operated sites that supported the development of U.S. nuclear weapons from the 1940s to the 1960s. The Department of Energy (DOE) assumed administration of FUSRAP, pursuant to the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-91). The Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act, 1998 (P.L. 105-62) authorized the transfer of 21 FUSRAP sites where remediation was not yet complete from DOE to USACE. DOE retained responsibility for the long-term stewardship of 25 FUSRAP sites where remediation was complete and responsibility for the remediation and long-term stewardship of federal facilities involved in the development of U.S. nuclear weapons. USACE later became responsible for the remediation of eight other sites added to FUSRAP. After USACE completes the remediation of a site, jurisdiction is transferred back to DOE for long-term stewardship. For information on the status of FUSRAP, see https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Environmental/FUSRAP.aspx. Although this report references USACE's FUSRAP and regulatory accounts, the report's discussion focuses on annual appropriations for the agency's water resource projects. |

| 5. |

Congress generally authorizes USACE water resource studies and construction projects prior to funding them. For information on the authorization process, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand. |

| 6. |

For information on FY2020 annual appropriations for USACE, see CRS Report R45708, Energy and Water Development: FY2020 Appropriations, by Mark Holt and Corrie E. Clark, and CRS In Focus IF11137, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2020 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand. For information on the FY2021 appropriations process, see CRS In Focus IF11462, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2021 Appropriations, by Anna E. Normand and Nicole T. Carter. |

| 7. |

Remarks by Lieutenant General Todd T. Semonite at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, "President's Fiscal 2021 Budget for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Civil Works Program Released," press conference, February 10, 2020. |

| 8. |

For more information on supplemental funds for USACE and associated congressional direction, see CRS In Focus IF11435, Supplemental Appropriations for Army Corps Flood Response and Recovery, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand. |

| 9. |

Sometimes the President is delayed in releasing the request in early February. For example, in the past, the request has been delayed during the first year of a new Administration, such as for the FY2018 budget request. |

| 10. |

The portion of the appendix of the President's FY2020 budget request related to USACE is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/coe-fy2020.pdf. |

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

|

| 13. |

For example, see USACE, Civil Works Direct Program Development Policy Guidance, Engineering Circular 11-2-220, March 31, 2019, at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Users/182/86/2486/EC_11-2-220.pdf?ver=2019-06-14-151345-087. For more on benefit-cost ratios, see CRS Report R44594, Discount Rates in the Economic Evaluation of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Projects, by Nicole T. Carter and Adam C. Nesbitt. |

| 14. |

For more on the flood-related supplementary appropriations, see CRS In Focus IF11435, Supplemental Appropriations for Army Corps Flood Response and Recovery, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand. |

| 15. |

In FY2020, Operation and Maintenance funding was 52% of USACE's annual appropriations. |

| 16. |

Congress provided direction in the FY2020 explanatory statement for the type of studies and construction projects to fund as new starts. For studies, Congress directed one multipurpose watershed study to address coastal resiliency, one for environmental restoration, one for flood and storm damage reduction, one for either flood and storm damage reduction or environmental restoration, and two for navigation. For construction, Congress directed two for navigation and two for environmental restoration. The other two new construction starts could be flood and storm damage reduction, environmental restoration, or multipurpose projects. Although Congress allowed USACE to initiate two new environmental infrastructure assistance activities using FY2020 appropriations, the agency chose not to fund any new environmental infrastructure starts. For information on USACE environmental infrastructure assistance authorities, see CRS In Focus IF11184, Army Corps of Engineers: Environmental Infrastructure Assistance, by Anna E. Normand. |

| 17. |

|

| 18. |

Three executive branch entities typically develop the work plan: USACE, Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works), and the Office of Management and Budget. |

| 19. |

USACE typically provides no details in the work plan on which projects in the continuing authorities programs are funded by appropriations. For more information on continuing authorities programs, see CRS In Focus IF11106, Army Corps of Engineers: Continuing Authorities Programs, by Anna E. Normand. |

| 20. |

USACE has not released business line information for FY2020. |

| 21. |

In FY2013, the environment business line was $510 million. The environment business line consists of the funding for USACE's ecosystem restoration projects and USACE's efforts to manage the natural resources of USACE-administered land and water. |

| 22. |

The construction fund includes funds in both the Construction account and the Mississippi River and Tributaries (MR&T) account. The MR&T construction is assumed to be riverine flood risk reduction. |

| 23. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, H.R. 1865 / Public Law 116–94, committee print, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., January 2020, 38-697, pp. 393-493, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-116HPRT38679/pdf/CPRT-116HPRT38679.pdf. |

| 24. |

See footnote 7 |