The Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Changes from April 21, 2020 to June 6, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Contents

- Background

- Forest Service 25 Percent Payments

- Bureau of Land Management O&C and CBWR Revenue-Sharing Payments

- Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program

- Revenue-Sharing Program Concerns and Issues

- Payment Stability

- Linkage

- Declining Timber Receipts

- Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000

- SRS Payment Formula

- Payment Election

- Payment Allocations: Title I, Title II, and Title III

- Resource Advisory Committees (RACs)

- Payment Data and Analysis

- FY2017 and FY2018 Payments

- FY2019 and FY2020 Payments

- Sequestration

- Legislative Issues

- Payment Formula

- Lands Covered

- Geographic Distribution of SRS and PILT Payments

- Source of Funds

- Authorized and Required Uses of the Payments

- Reauthorization and Duration of the Programs

- COVID-19

Figures

- Figure 1. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments

- Figure 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments by Title

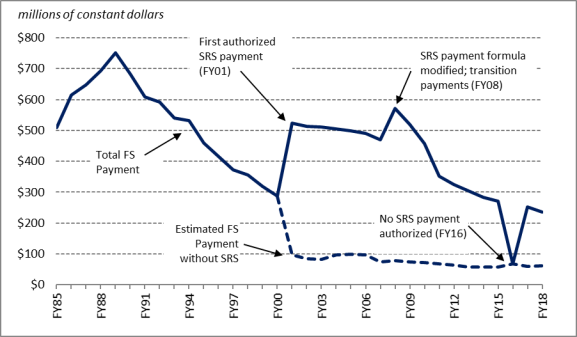

- Figure 3. Forest Service (FS) Payments and Estimated Payments

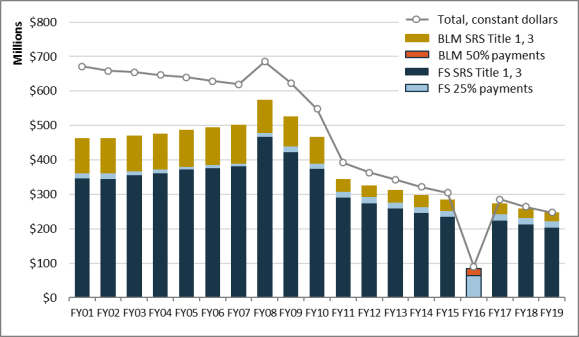

- Figure 4. FS and BLM Payments, FY2001-FY2019

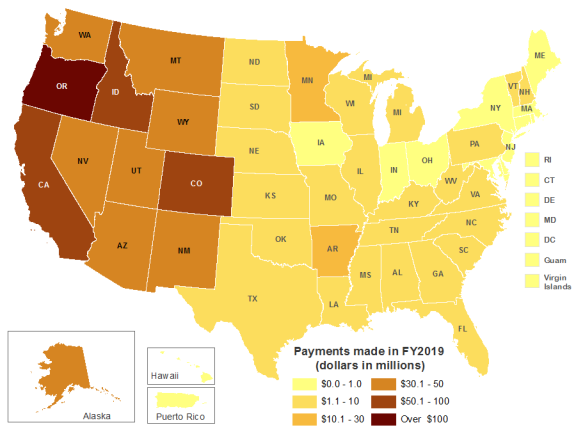

- Figure 5. PILT, BLM, and FS Payments Made in FY2019

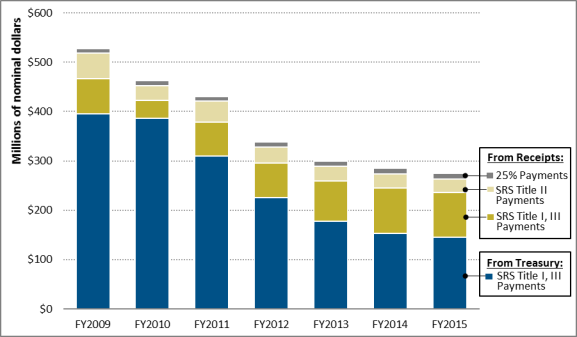

- Figure 6. Source and Distribution of Forest Service (FS) Payments

Tables

- Table 1. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Legislative History

- Table 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments, FY2001-FY2019

- Table 3. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Title Allocations

- Table 4. Forest Service (FS) Payments

- Table 5. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Payments

- Table 6. FS, BLM, and PILT Payments Made in FY2019, by State

Summary

The Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-

June 6, 2023

Determination Act: Background and Issues

Katie Hoover

Under federal law, state and local governments receive payments through various programs due

Specialist in Natural

to the presence of federally owned land within their jurisdictions. Some of these payment

Resources Policy

programs are based on the revenue generated from specific land uses and activities. For example,

Congress has authorized payments to the counties containing national forests—managed by the Forest Service—based on the revenue generated from those lands. In addition, Congress has

authorized the 18 counties in western Oregon containing the Oregon and California (O&C) lands and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands—managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM)—to also receive a payment based on the revenue generated from those lands.

Revenue-generating activities include timber sales, recreation, grazing permits, and land use rentals, among other activities; timber sales have been the largest historical source of revenue. Starting in the 1990s, however, federal timber sales began to decline substantially, which led to substantially reduced payments to the counties. In response, Congress enacted the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS; P.L. 106-393) as a temporary, optional program of payments, starting in FY2001. Congress has since extended the payments for every year —except FY2016—through FY2023. Counties with eligible lands (national forests, O&C, and CBWR lands) canmay opt to receive either an SRS payment or a revenue-sharing payment, althoughbased payment; most counties have elected to receive the SRS payment. Because a larger subset of counties are eligible, the bulk of the SRS payment goes to the lands managed by the Forest Service.

Each county'’s SRS payment is determined by a formula based on historic revenues, area of eligible federal lands, and county incomes. Because theypayments are based on historic, rather than current, revenue, the SRS payments are not affected by any annual fluctuations in the revenue streams from the specified lands. (This means that the SRS payments would not be impacted by any potential revenue fluctuations associated with COVID-19). The total SRS payment, however, declines by 5% annually revenue, fluctuations in current revenue streams from the specified lands do not affect SRS payments. Congress has changed the SRS payment formula several times. For example, Congress amended the formula so the payment declined by 10% annually from FY2008 through FY2011 and again amended the formula so the payment declined by 5% annually from FY2012 to FY2020. More recently, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58) removed the annual decline and established a set annual payment amount. The program is funded through mandatory spending, with funds coming first from agency receipts and then from the Treasury. SRS payments are disbursed after the fiscal year ends, so the FY2020FY2023 SRS payment—the last authorized payment—areis due to be made in FY2021.

FY2024.

The SRS payment is divided into three parts, each named after its respective title in the authorizing law and each with different requirements for how the funds may be used. Title I payments are to be used in the same manner as the revenue-sharingbased payment (restricted to roads and schools purposes for the Forest Service payment but available for a broader range of governmental purposes for the BLM payment). Title II payments are retained by the relevant federal agency to be used for projects on or to benefit the federal lands within the county. Title III payments are to be used for specified county purposes. There are different requirements for how a county may allocate its payment among the three titles, and those requirements vary depending on the total payment amount the county is set to receivereceives. The bulk of the payment, however, is allocated to the Title I payment (around 80%-85% of the payment for most counties). Congress has continued the allocations of the total payment among titles set by each county in FY2013.

Prior to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (P.L. 117-58), Congress had frozen the payment allocations chosen by each county for the FY2013 payment and continued that allocation through the FY2020 payment.

When SRS payments temporarily expired for FY2016, county payments returned to the revenue-based system and were significantly lower than the payments received under SRS. With the pending expiration of SRS after the FY2020 paymentFY2023 payments, county payments arewould be set to return to the revenue-based system for FY2024. Congress may consider several options to address county payments, including reauthorizing SRS (with or without modifications), implementing other legislative proposals to address the county payments, and taking no action, among others. Congressional debates over reauthorization have considered the basis, level, and distribution of payments and interaction with other compensation programs (e.g., the Payments in Lieu of Taxes program); the authorized and required uses of the payments; the duration of any changes (temporary or permanent); and the source of funds (receipts, the Treasury, or other revenue source). In addition. More generally, legislation with mandatory spending—such as SRS—raises policy questions about congressional control of appropriations. Current budget rules to restrain deficit spending typically impose a procedural barrier to such legislation, generally requiring offsets by additional receipts or reductions in other spending.

The FY2019 SRS payment was distributed in April 2020. The totalIn addition, as with non-defense mandatory spending, SRS payments are generally subject to sequestration, though that has varied over the years based on when payments were reauthorized.

The FY2022 SRS payment was distributed in spring 2023. The total, post-sequester FY2022 SRS payment (Titles I, II, and III) was $254.3267.0 million ($225.8239.0 million FS; $28.427.9 million BLM). The total FY2022 SRS payment made to counties (Titles I and III only) was $228.7241.1 million ($202.6215.5 million FS; $26.0 million BLM).

Under federal law, local governments are compensated25.6 million BLM).

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 22 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 10 link to page 12 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 28 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Contents

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 2

Forest Service 25 Percent Payments ......................................................................................... 2 Bureau of Land Management O&C and CBWR Revenue-Based Payments ............................ 3 Revenue-Based Program Concerns and Issues ......................................................................... 4

Payment Stability ................................................................................................................ 4 Linkage ............................................................................................................................... 5 Declining Timber Receipts ................................................................................................. 5

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 ........................................ 6

SRS Payment Formula .............................................................................................................. 9 Payment Election .................................................................................................................... 10 Payment Allocations: Title I, Title II, and Title III ................................................................... 11

Resource Advisory Committees (RACs) .......................................................................... 14

Payment Data and Analysis ........................................................................................................... 15

FY2019 and FY2020 Payments .............................................................................................. 19 FY2021-FY2023 Payments ..................................................................................................... 19 Sequestration ........................................................................................................................... 20

Legislative Issues .......................................................................................................................... 21

Payment Formula .................................................................................................................... 22 Lands Covered ........................................................................................................................ 22 Geographic Distribution of SRS and PILT Payments ............................................................. 22 Source of Funds....................................................................................................................... 25 Authorized and Required Uses of the Payments ..................................................................... 26 Reauthorization and Duration of the Programs ....................................................................... 26

Figures Figure 1. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments ............................................. 9 Figure 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments by Title ............................... 11 Figure 3. FS and BLM Payments, FY2001-FY2022 ..................................................................... 18 Figure 4. PILT, BLM, and FS Payments Made in FY2022 ........................................................... 23 Figure 5. Source and Distribution of Forest Service (FS) Payments ............................................. 25

Tables Table 1. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Legislative History .............................................................. 6 Table 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments, FY2001-FY2022 ................. 8 Table 3. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Title Allocations ................................................................. 12 Table 4. Forest Service (FS) Payments .......................................................................................... 15 Table 5. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Payments.............................................................. 16 Table 6. FS, BLM, and PILT Payments Made in FY2022, by State .............................................. 24

Congressional Research Service

link to page 32 link to page 35 link to page 37 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Appendixes Appendix A. SRS Reauthorizations Through FY2017 .................................................................. 28 Appendix B. FY2013 Sequestration Issues ................................................................................... 31

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 33

Congressional Research Service

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

nder federal law, local governments receive federal funding through various programs due to the presence of federal lands within their borders. Federally-This is in part because federally

U owned lands cannot be taxed, but may create demand for services from state or local

entities, such as fire protection, police cooperation, or longer roads to skirt the property. Many of the compensation programs are based on revenue generated from specific land uses and activities (referred to as revenue-sharingbased programs throughout this report).

Counties containing national forests managed by the Forest Service (FS) have historically received a percentage of agency revenues. Similarly, counties containing the Oregon and California (O&C) and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands, primarily managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), also have received a payment based on agency revenues. For many decades, the primary source of revenue from those lands was the sale of timber.11 In the 1990s, timber sales declined substantially from the historic levels in the 1980s—by more than 90% in some areas—which led to substantially reduced payments to the counties. In response, Congress enacted the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS) to provide a temporary, optional system to supplant the FS and BLM revenue-sharingbased programs.22 The authorization for the SRS payments originally expired at the end of FY2006, but Congress extended the payments an additional 1316 years—through FY2020FY2023, with a one-year lapse in the authorization for FY2016—through several reauthorizations.3 SRS is set to expire after the FY2020FY2023 payments are made, after which county payments are to return to a revenue-based system.

This report provides background information on FS and BLM revenue-sharingbased payments and a brief overview of a related payment program—the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program.3 4 Because the revenue-sharingbased, SRS, and PILT payments interact with each otherone another in varying ways, proposals to amend the revenue-sharingbased programs or SRS have often included modifications to the PILT program as well. This report then provides on overview of the SRS payments and a discussion of some of the legislative issues facing Congress when considering these payment programs, including the potential effects from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.4

Background

programs.

Payment Terminology

The fol owing definitions reflect how the different payments are defined and referred to in this report (note that other sources may use different terms or report the data differently). For the payments in which both Forest Service (FS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands are applicable, the appropriate agency wil be specified in the text. BLM payment reflects the payments made to the counties containing the Oregon and California (O&C) and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands as authorized for that year. For years prior to FY1993, this was the respective revenue-based payment; starting in FY1993, this was the BLM safety-net payment. For years starting in FY2001, however, this generally refers to the BLM Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (SRS) Title I and Title II payments. BLM total payment includes the BLM payment plus the SRS Title II payment retained by the agency. FS 25 Percent Payments are the revenue-based payments authorized through the Act of May 23, 1908. Data for the 25 Percent Payments may also include the Special Act Payments as specified, such as the Payments to Minnesota

1 For more information on federal timber sales, see CRS Report R45688, Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands. 2 The Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS; P.L. 106-393), 16 U.S.C. §§7101-7153.

3 SRS payments for FY2021-FY2023 were reauthorized in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58, §41202).

4 Payments in Lieu of Taxes Act of 1976 (PILT; P.L. 94-565 as amended, 31 U.S.C. §§6901-6907). For more information, see CRS Report R46260, The Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program: An Overview.

Congressional Research Service

1

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Counties. For the years FY1993 through FY2000, the data for the 25 Percent Payments also include the FS safety-net payments. FS payment reflects the payments authorized to be made to eligible counties for that year. Prior to FY2001, this includes the FS 25 Percent Payment and the FS safety-net payment. Starting in FY2001, this includes the FS revenue-based payment plus the SRS Title I and Title II payments, except in FY2016, when SRS payments were not authorized. FS total payment includes the FS county payment plus the SRS Title II payment retained by the agency. Revenue-based payment for the FS comprises the 25 Percent Payments. For the BLM, this comprises the O&C and CBWR payments. Safety-net payment includes payments made from FY1993 to FY2000 to certain counties in Washington, Oregon, and California for both FS and BLM (for Oregon, only BLM). SRS Title I, II, or III payment reflects the payment made pursuant to one or more of the SRS titles, as specified in the text. SRS total payment includes the sum of the Title I, Title II, and Title III payments.

Background

Forest Service 25 Percent Payments Forest Service 25 Percent Payments

Congress has authorized several different revenue-sharingbased payments for the counties containing lands managed by the FS.55 SRS affects one of those payments—the payments authorized under the Act of May 23, 1908, referred to as the "25 Percent Payments" in this report. The other payments (e.g., Payments to Counties for the national grasslands and Special Act Payments) are much narrower in scope and application and, consequently, much smaller.66 These payments are sometimes included in FS revenue-sharingbased payment totals, but they are not affected by the SRS payments.

Congress first directed the FS to begin revenue-sharingbased payments in appropriations laws for 1906 and 1907. For those years, the requirement was for the FS to pay 10% of its gross receipts per year to states for use on roads and schools in the counties in which the national forests are located. In 1908, Congress raised the payment to 25% of gross receipts and permanently authorized the 25 Percent Payments as mandatory spending.77 The compensation rate remained at 25% of gross receipts annually for the next 100 years, until it was changed in 2008 to 25% of average gross receipts over the previous 7 years—essentially a 7-year rolling average of receipts.8 8 Receipts come from eligible sales, leases, rentals, or other fees for using national forest lands or

5 Compensation programs related to energy and mineral development on national forest system lands are administered by the Department of the Interior (DOI) and are not addressed in this report.

6 The Payments to Counties program requires payments of 25% of net receipts generated on the national grasslands to be paid directly to the counties ($52.0 million for FY2021). Special Act Payments include various other revenue-based payments authorized for specific purposes or limited to specific places, such as the Payments to Minnesota Counties program, which provides payments to three counties in northern Minnesota based on the appraised value of certain lands within the Superior National Forest ($5.7 million for FY2021). Special act payments also include payments for quartz mined from the Ouachita National Forest in Arkansas and for revenue generated on the Quinault Special Management Area in the Olympic National Forest in Washington (~$4,000 in FY2020 for both). Data from the Forest Service (FS), FY2022 Budget Justification and FS’s Payments to Counties website at https://www.fs.usda.gov/working-with-us/secure-rural-schools/bankhead-jones-payments. For more information on these programs and FS’s mandatory appropriations generally, see CRS Report R46557, Forest Service Appropriations: Ten-Year Data and Trends (FY2011-FY2020).

7 Act of May 23, 1908, 16 U.S.C. §500. 8 P.L. 110-343 §601.

Congressional Research Service

2

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Receipts come from eligible sales, leases, rentals, or other fees for using national forest lands or resources (e.g., timber sales, recreation fees, and communication site leases), although Congress has designated some activities exempt from the revenue-sharing requirement.9 Because the payments areFS revenues for the purposes of revenue-sharing payments.9 Because the payment amounts are calculated based on the average annual revenue generated during a seven-year period, the payment amounts cannot be calculated—and thus payments cannot be made— until after the most recent fiscal year in each period is completed (for example, payments reflecting the annual average for FY2014-FY2020 are to bewere made in FY2021).

The 25 Percent Payments are sometimes referred to as the Payments to States program because the FS first sends the payment to the states.1010 The states have no discretion in assigning the funds to the appropriate county, however. FS determines the amount of the total state payment to be allocated to each county based on each county'’s national forest acreage and provides that amount to the state. The states cannot retain any of the funds; the funds must be passed through to local governmental entities for use at the county level (but not necessarily to county governments themselves).1111 Each state must spend the funds on road and school programs, and state law sets forth how the payments are to be allocated between road and school projects. The state laws differ widely, generally ranging from 30% to 100% for school programs, with a few states providing substantial local discretion on the split.

Bureau of Land Management O&C and CBWR Revenue-Sharing Payments

Based Payments Congress has also enacted revenue-sharingbased programs for BLM lands for various types of resource use, including the Oregon and California (O&C) payments and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) payments.12payments.12 The O&C payments are made to the 18 counties in western Oregon containing the revested Oregon and California grant lands, which are lands that were returned to federal ownership for failure of the state to fulfill the terms of the grant. The O&C counties receive 50% of the receipts from these lands, and the funds may be used for any local governmental purposes.1313 The CBWR lands are located in two of the same counties in western Oregon that also contain O&C lands. A portion of the revenue generated from the CBWR lands also must be paid to the two counties, and those funds may be used for schools, roads, bridges, and highways.14

14

The O&C and CBWR payments are mandatory payments that are paid directly to the counties. The CBWR and O&C lands and payments are often grouped together, and in this report "O&C" “O&C” refers to both, unless otherwise specified.

9 For example, revenue generated through stewardship contracts is not counted toward the revenue-based requirement (16 U.S.C. §6591c(e)(3)(A)). For more information on the authorized uses and revenue-generating activities on the national forests, see CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Management: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress.

10 FS sometimes includes other payment programs within the Payments to States program, which is also the name of the Treasury account from which the payments are made. This includes the Payments to Counties and Payments to Minnesota Counties. SRS is included when authorized.

11 For example, funds may be allocated directly to a school district. 12 FS also manages a portion (19%) of the O&C lands. For more information, see CRS Report R42951, The Oregon and California Railroad Lands (O&C Lands): Issues for Congress. Compensation programs related to grazing, land sales, and energy and mineral development are not addressed in this report.

13 43 U.S.C. §§2601 et seq. 14 Per statute (43 U.S.C. §§2621 et seq.), 75% of the gross receipts from Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands are deposited to a special fund and used to make tax-equivalency payments; any portion remaining in the fund after a 10-year period is transferred to the General Fund of the Treasury.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 30 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program

Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program

In addition to the FS and BLM revenue-sharingbased programs, Congress has enacted other programs to compensate for the presence of federal land. The most widely applicable program, administered by the Department of the Interior, is the Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program.15 (31 U.S.C. §§6901-6907). PILT payments to counties are calculated in dollarsdol ars per acre of federal land and are based on eligible federal lands, as specified in statute (the total payment amounts are restricted in counties with very low populations). The eligible lands include national forests and O&C lands, among others, in each county.

PILT payments are reduced (to a minimum payment per acre) by other payment programs as specified in statute.16 The PILT payments are reduced by the FS payments but not by the O&C payments. This means that the PILT payment for counties containing national forests is affected by the FS payment (either revenue-sharingbased or SRS), but the PILT payment for counties containing O&C lands is not similarly affected. This also means that decreases in FS payments may increase a county'’s payments under PILT in the followingfol owing year (and vice versa), although the difference is rarely proportionate. Proposals to amend the revenue-sharingbased programs or SRS have often included modifications to the PILT program.

Revenue-SharingPILT payments are reduced (to a minimum payment per acre) by other payment programs as specified in statute. For more information, see CRS Report R46260, The Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) Program: An Overview.

Revenue-Based Program Concerns and Issues Program Concerns and Issues

Prior to the enactment of SRS, Congress, counties containing FS and O&C lands, and other observers raised three principal concerns about FS and O&C revenue-sharing programs,17 which werethree principal concerns about FS and O&C revenue-based programs had been raised by Congress, counties containing FS and O&C lands, and other observers:15 (1) payment stability and the annual uncertainty about payment amounts; (2) the linkage between timber revenue and county payments; and (3) the decline in FS and O&C receipts due to the decline in timber sales. SRS addresses some of these concerns, but they may again be at issue when SRS expires.

if the authorization for SRS payments were to expire. Payment Stability

One concern about the FS and O&C revenue-sharingbased payments was that payments would fluctuate annually based on the revenue received in the previous year. Even in areas with modest declines or increases in revenuetimber sales, payments have varied widely from year to year. For example, from FY1985 to FY2000, the payments from each national forest fluctuated an average of nearly 30% annually—that is, on average, a county'’s payment in any year was likely to be nearly 30% higher or lower than its payment the preceding year. This is in part due to fluctuations in timber sale locations and market forces, among other factors. Such wide annual fluctuations imposed serious budgeting uncertainties on the counties.

The concern over annual fluctuations led to Congress changing the compensation rate to a rolling seven-year average of receipts in 2008.1816 Thus, payments increase more slowly than in the past when and where national forest receipts are rising but decline more slowly when and where receipts are falling. The extent to which this provides more stability for the counties is not clear. Since this change has been enacted, most counties have opted to receive an SRS payment instead of the revenue-sharingbased payment, except for the one year when the SRS payments were not authorized. Relatedly, however, the expiration and reauthorization of the SRS payments over the past few years has introduced a different kind of budgeting uncertainty for the counties, discussed further in the " “Reauthorization and Duration of the Programs" ” section of this report.

Linkage

15 Forest Counties Payments Committee, Recommendations for Making Payments to States and Counties: Report to Congress (Washington: GPO, 2003). Hereinafter referred to as Forest Counties Payments Committee Report, 2003. The committee was established in Section 320 of the FY2001 Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, P.L. 106-291.

16 P.L. 110-343 §601.

Congressional Research Service

4

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Linkage

A longer-term concern is referred to as linkage. Some observers noted that because the counties received a portion of receipts, they were financially rewarded for advocating receipt-generating activities (principally timber sales) and for opposing management decisions that might reduce or constrain such activities, thus reducing the direct financial benefits from receipts (e.g., designating wilderness areas or protecting commercial, tribal, or sport fish harvests). Some interests support retaining the linkage between county compensation and agency receipts because such activities usually also provide local employment and income, especially in rural areas where unemployment is often high. Others assert that ending the linkage is important so that the direct financial incentive for maximizing receipts would be removed as one of the factors for local government officials to consider in their decisionmaking regarding use of the lands for activities other than timber sales.19

17 Declining Timber Receipts

A primary concern about the FS 25 Percent Payments and O&C payments was the effect of declining timber sale revenue on counties. National forest receipts (subject to the 25% sharing) declined from their peak of $3.02.9 billion in FY1989 to $664.3691.0 million in FY1999, in inflation-adjusted FY2019 dollars.20constant FY2022 dollars.18 The decline was primarily due to declining receipts from decreasing timber production. For example, FS harvested 12.0 billion board feet of timber in FY1989 (at a value of $2.72 billion in FY2019constant dollars); in FY1999, FS harvested 2.9 billion board feet (at a value of $525.8 million in FY2019constant dollars).2119 The decline in timber sales began in the Pacific Northwest but eventually was experienced nationwide, owing to a combination of changing forest management policies and practices, increased planning and procedural requirements, changing public preferences, economic and industry factors, and other developments. BLM experienced a similar trend in receipts over the same time period.

Consequently, the revenue-sharingbased payments to counties also declined. For example, the FY1989 FS 25 Percent Payments totaled $751.4 million (FY2019 dollars).22722.3 million.20 By FY1993, the payment was $540.6 million (FY2019 dollars).23 Similar0 million.21 Similarly to the decline in timber receipts, the decline in the revenue-sharingbased payments also began in the Pacific Northwest. For example, payments to the counties in Oregon containing national forests decreased by 20% from FY1989 to FY1993, and payments to the counties containing the

17 Forest Counties Payments Committee Report, 2003, p. 24. 18 FS revenue data compiled from annual budget documents. In nominal dollars, the receipts in FY1989 were $1.44 billion and the receipts in FY1999 were $432.5 million. Figures adjusted to constant (estimated FY2022) dollars using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Chained Price Index (CPI) from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Table 10.1, “Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables” at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/.

19 FS timber data compiled from annual Cut & Sold reports available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/forestmanagement/products/cut-sold/index.shtml. In nominal dollars, the value of the FY1989 timber sales was $1.31 billion, and the value of the FY1999 timber sales was $342.3 million. Figures adjusted to constant (estimated FY2022) dollars using the GDP-CPI from the White House OMB Table 10.1, “Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables” in Historical Tables. For more information on federal timber sales, see CRS Report R45688, Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands.

20 FS historical payment data provided by FS Legislative Affairs office, 2005. In nominal dollars, the FY1989 25 Percent Payment was $361.9 million and was adjusted to constant (estimated FY2022) dollars using the GDP-CPI from the White House OMB Table 10.1, “Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables” in Historical Tables.

21 FS historical payment data provided by FS Legislative Affairs office, 2005. In nominal dollars, the FY1993 25 Percent Payment was $304.7 million and was adjusted to constant (estimated FY2022) dollars using the GDP-CPI from the White House OMB Table 10.1, “Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables” in Historical Tables.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 10 link to page 32 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

forests decreased by 20% from FY1989 to FY1993, and payments to the counties containing the O&C lands decreased by 28%.2422 In California, FS payments to counties decreased by 30% over that same time frame, and in Washington, FS payments decreased by 35%. The extent of declining revenues in individual counties within those states varied, ranging from minimal to substantial (and often was a function of the amount of applicable federal land located within the county).

In 1993, Congress authorized FS and BLM to make "safety-net payments" to several counties in the Pacific Northwest, including in Oregon, California, and Washington.2523 These payments were set at a declining percentage of the average revenue-sharingbased payments made to those counties between FY1986 and FY1990.2624 As federal timber sales—and revenue-sharingbased payments—began to decline nationwide, however, Congress replaced the regional safety-net payments with the nationwide SRS program starting in FY2001.

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000

In 2000, Congress enacted the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (SRS) after extensive debates and several different bill versions.2725 The act established an optional alternative to the revenue-sharingbased payments for FS and O&C lands, starting with the FY2001 payment. Each county with FS or O&C land could choose to receive either the regular revenue-sharingbased payments or the SRS payment.

SRS was originally enacted as a temporary program, expiring after payments were made for FY2006. However, SRS was reauthorized and modified several times, and payments were authorized annually through the FY2015 payment (see Table 1 and Appendix B)A). The authorization lapsed for the FY2016 payment, but payments were reauthorized starting in FY2017 and extended through FY2023.26 SRS payments—like the revenue-basedFY2017 and are set to expire at the end of FY2020. The longest reauthorization was for four years; otherwise, the reauthorizations have extended the payments for one or two years each. SRS payments—like the revenue-sharing payments—are disbursed after the end of the fiscal year, so, barring any congressional action, payments are set to expire after the FY2023 the FY2020 payment is to be made in FY2021.

payment is made in FY2024.

Table 1. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Legislative History

Statute (Date

Enacted)

Duration

Authorized Payment Level

Major Changes

P.L. 106-393

FY2001-FY2006 Determined by formula; average

Established program

(10/30/00)

annual payment was around $500 mil ion total

Table 1. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Legislative History

|

Statute (Date Enacted) |

Duration |

Authorized Payment Level |

Major Changes |

|

P.L. 106-393 (10/30/00) |

FY2001-FY2006 |

Determined by formula; average annual payment was around $500 million total |

Established program |

P.L. 110-28 |

FY2007 |

$525 million |

$425 million was paid from discretionary appropriations |

(10/03/08) |

FY2008-FY2011 |

|

|

rol ing seven-year average

P.L. 112-141 |

FY2012 |

95% of FY2011 level ($344 million) |

Modified the declining full funding amount to -5% annually |

§100101

FY2012

95% of FY2011 level ($344 mil ion) Modified the declining ful funding

(07/06/12)

amount to -5% annually

P.L. 113-40 |

FY2013 |

95% of FY2012 level ($329 million) |

None |

§10

FY2013

95% of FY2012 level ($329 mil ion) None

(10/02/13)

P.L. 114-10 (04/16/15) |

FY2014-FY2015 |

|

None |

|

P.L. 115-141 Division O, §401 (03/23/18) |

FY2017-FY2018 |

95% of FY2015 level ($281 million for FY2017, $268 million for FY2018) |

Modified payment allocations |

P.L. 116-94 (12/20/19) |

FY2019-FY2020 |

95% of the previous year funding ($254 million for FY2019, ~$241 million estimated for FY2020) |

None |

Division

FY2019-FY2020

95% of the previous year funding

None

H, Title III

($254 mil ion for FY2019, ~$241

(12/20/19)

mil ion estimated for FY2020)

P.L. 117-58 Division

FY2021-FY2023

Equal to the payment made in

Established a set ful funding

D, Title XII (11/15/21)

FY2017 (~$282 mil ion)

amount and removed the annual decline; reauthorized payment elections and allocations; and modified membership requirements for Resource Advisory Committees

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Notes: Except for the FY2007 payment, Congress authorized the payments as mandatory spending, with a portion of the payment derived from agency revenue and the balance from the General Fund of the Treasury. Duration reflects the fiscal years in which authorized payments were based, not the year the payments were made. The payments were made in the followingfol owing fiscal year (e.g., the payment authorized for FY2018 was disbursed in FY2019). For more information on the reauthorizations through FY2015FY2017, see Appendix B.

a. A. a. The transition payments for specific states authorized in P.L. 110-343 for FY2008-FY2010 resulted in the

total payment amount exceeding the "full funding" amount defined in the act.

The SRS payments are determined by a formula based on historic revenue generated on the applicable federal lands. Originally, each county'’s SRS payment was calculated as the average of the three highest payments received by the county between FY1986 and FY1999. The formula was later amended to include other factors and to decline annually, as discussed in the " “SRS Payment Formula"” section. . Funds needed to achieve the full payment are mandatory spending and come first from agency receipts (excluding deposits to special accounts and trust funds) and then from "“any amounts in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated."28”27 The program is also authorized to receive discretionary funding, although this has happened only one time (FY2007, see Appendix B A for more information).

27 16 U.S.C. §7112(b)(3).

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

The SRS payment is divided into three parts, based on three of the titles in the authorizing law. Each county can allocate the payment among the three titles, with different requirements depending on the amount a county was set to receive.

-

• Title I payments are to be used in the same manner as the revenue-

sharingbased payment (for roads and schools purposes for the FS payment, or, for the BLM payment, for any governmental purpose).29 - 28

• Title II payments are not made to the county but are retained by FS or BLM to be

used for projects on the relevant federal lands within the county.

30 - 29

• Title III payments are made to the county, and the funds are to be used for

specified county projects.

31

30

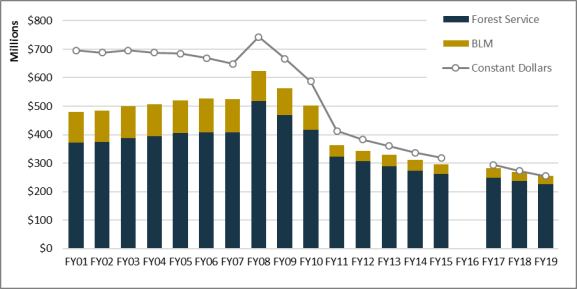

The bulk of the SRS payment (8384% on average) is for counties containing the national forests (see Table 2 andand Figure 1). This is because the FS payment is more broadly applicable, whereas the BLM payment is applicable only for the 18 counties in one state—Oregon—containing the O&C lands. Because a portion of the SRS payment is retained by the agency, it is common to see only the portion of the payment that was made to the county—the Title I and Title III payments—provided in various reports.

Table 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments, FY2001-FY2019

FY2022

(nominal dollars in millions)

Receipt

TOTAL

Receipt

TOTAL

Yeara

FS

BLM

SRS

Yeara

FS

BLM

SRS

FY2001

$371.1

$109.7

$480.8

FY2012

$305.9

$38.0

$343.9

FY2002

373.9

110.6

484.5

FY2013

289.0

39.6

328.6

FY2003

388.8

111.9

500.7

FY2014

273.9

38.3

312.2

FY2004

393.9

113.3

507.2

FY2015

261.0

35.6

296.6

FY2005

404.9

115.9

520.9

FY2016b

—

—

—

FY2006

409.0

117.1

526.1

FY2017

249.3

32.2c

281.5

FY2007

408.1

116.9

525.0

FY2018

237.5

30.1

267.6

FY2008

517.9

105.4

623.3

FY2019

225.8

28.4

254.3

FY2009

467.6

94.9

562.4

FY2020

214.7

25.4

240.1

FY2010

415.8

85.5

501.3

FY2021

250.7

30.1

281.7

FY2011

321.9

40.0

361.9

FY2022

239.0

27.9

267.0

Sources: FS FY2001-FY2005, FY2007 data from FS legislative affairs office; FS FY2006, FY2008-FY2022 data from annual FS report, All Service Receipts: Title I, II, and III Region Summary (ASR-18-3), available at https(nominal dollars in millions)

|

FS |

BLM |

TOTAL SRS |

|

FS |

BLM |

TOTAL SRS |

|

|

FY2001 |

$371.1 |

$109.7 |

$480.8 |

FY2011 |

$321.9 |

$40.0 |

$361.9 |

|

|

FY2002 |

373.9 |

110.6 |

484.5 |

FY2012 |

305.9 |

38.0 |

343.9 |

|

|

FY2003 |

388.8 |

111.9 |

500.7 |

FY2013 |

289.0 |

39.6 |

328.6 |

|

|

FY2004 |

393.9 |

113.3 |

507.2 |

FY2014 |

273.9 |

38.3 |

312.2 |

|

|

FY2005 |

404.9 |

115.9 |

520.9 |

FY2015 |

261.0 |

35.6 |

296.6 |

|

|

FY2006 |

409.0 |

117.1 |

526.1 |

|

— |

— |

— |

|

|

FY2007 |

408.1 |

116.9 |

525.0 |

FY2017 |

249.3 |

|

281.5 |

|

|

FY2008 |

517.9 |

105.4 |

623.3 |

FY2018 |

237.5 |

30.1 |

267.6 |

|

|

FY2009 |

467.6 |

94.9 |

562.4 |

FY2019 |

225.8 |

28.4 |

254.3 |

|

|

FY2010 |

415.8 |

85.5 |

501.3 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Sources: FS FY2001-FY2005, FY2007 data from FS legislative affairs office; and FS FY2006, FY2008-FY2018 data from annual FS report, All Service Receipts: Title I, II, and III Region Summary (ASR-18-3), available at http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/pts/home://www.fs.usda.gov/working-with-us/secure-rural-schools/payments. BLM data from annual Official Payments Made to Counties reports, available at https://www.blm.gov/programs/natural-resources/forests-and-woodlands/oc-lands.

oc-lands. Notes: FS = Forest Service; BLM = Bureau of Land Management. Some years may reflect sequestration. Totals may not add due to rounding.

a.

28 P.L. 106-393, Title I, Secure Payments for States and Counties Containing Federal Land (16 U.S.C. §§7111-7113). 29 P.L. 106-393, Title II, Special Projects on Federal Land (16 U.S.C. §§7121-7128). 30 P.L. 106-393, Title III, County Funds (16 U.S.C. §§7141-7144).

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 32

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Notes (continued): a. Receipt Year reflects the fiscal year in which the payment is based, not the year the payments are made.

The payments are made in the followingfol owing fiscal year (e.g., the FY2018 payment was disbursed in FY2019).

b.

b. SRS payments were not authorized for the FY2016 receipt year.

c. c. BLM does not include the $18.5 millionmil ion revenue-sharingbased payment made prior to the reauthorization of the

SRS payment for FY2017 as part of the total SRS payment for that year. Instead, BLM reports the FY2017 SRS payment to be $14.0 millionmil ion. This is a departure from how the FY2014 SRS payment was reported, which was also reauthorized after the revenue-sharingbased payment had been disbursed. For this report, however, the revenue-sharingbased payment is included in the Title I payment for consistency purposes.

. Figure 1. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments (FY2001-FY2019) |

|

. Notes: FS = Forest Service; BLM = Bureau of Land Management.

|

The following sections discuss the payment formula, payment allocations, and use of the funds in more depth and provide payment data and analysis. Information on the two most recent reauthorizationsreauthorization (authorizing payments for FY2017FY2021 through FY2020FY2023) is included in the payment data section. Information on the prior reauthorizations is available in Appendix B.

A. SRS Payment Formula

The SRS payment formula has been modified several times. When SRS was first enacted, each county'county’s payment was calculated as the average of the three highest revenue-sharingbased payments received by the county between FY1986 and FY1999. The total authorized payment for FY2001-

Congressional Research Service

9

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

FY2006 was the sum of the payments calculated for each participating county for each year. When the program was reauthorized in FY2008, however, Congress modified the program in several ways, including by establishing a new payment formula and specifying the total authorized payment level.

The payment formula is still based on each eligible county’s historic revenue-sharingbased payments, but it also takes into account each county'the changes incorporated the county’s share of federal land and relative income level into the calculation.31 In essence, the new formula differed from the original SRS formula by basing half the payment on relative historic revenue and half on relative proportion of FS and O&C land, with an adjustment based on relative county income. This was done because the majority of payments under the original SRS went to Oregon, Washington, and California (more than 65% of payments in FY2006). Because of the altered allocation, several counties opted out of the amended SRS system, and others opted in. Because payments are based on historic revenue, fluctuations in current revenue streams from the specified lands do not affect SRS payments.

Under the modified formula, the total authorized SRS payment level—defined as full funding—was set at $500 million for FY2008.32 From FY2008 through FY2020, this full funding amount was set to decline annually (originally by 10%, later changed to 5%). The annual decline, however, was removed starting with the FY2021 payment, with the full funding amount set to a constant amount equal to the FY2017 payment.33 The full funding amount is allocated among all counties that elect to receive an SRS payment in lieu of the revenue-based payment. Thus, the fewer counties that participate (i.e., the more that opt for the revenue-based payment programs rather than SRS), the more each eligible county receives.

s share of federal land and relative income level.

Under the modified formula, the total SRS payment level—defined as full funding—is set at $500 million for FY2008, and this full funding amount declines annually (originally by 10%, later changed to 5%).32 The full funding amount is allocated among all counties that elect to receive an SRS payment in lieu of the revenue-sharing payment (eligible counties). Thus, the fewer counties that participate (i.e., the more that opt for the revenue-sharing payment programs rather than SRS), the more each eligible county receives. Each eligible county's payment is calculated using multiple steps:

- Step 1. Determine the three highest revenue-sharing payments (high-three) between FY1986 and FY1999 for each eligible county, and calculate the average of the three.33

- Step 2. Calculate the proportion of these payments in each eligible county: divide each county's high-three average [from Step 1] by the total of the high-three averages in all eligible counties, with separate calculations for FS lands and O&C lands.

- Step 3. Calculate the proportion of FS and O&C lands in each eligible county: divide each eligible county's FS and O&C acreage by the total FS and O&C acreage in all eligible counties, with separate calculations for FS lands and O&C lands.

- Step 4. Determine the base share for counties with FS lands and the 50% base share for counties with O&C lands: add the payment proportion [from Step 2] and the acreage proportion [from Step 3] and divide by 2, with separate calculations for FS lands and O&C lands.

- Step 5. Calculate each county's income adjustment: divide the per capita personal income in each county by the median per capita personal income in all eligible counties, and then square the result.34

- Step 6. Divide each county's base share or 50% base share [from Step 4] by its income adjustment [from Step 5].

- Step 7. Calculate each county's adjusted share or 50% adjusted share: divide each county's result from Step 6 by the total for all eligible counties (FS and O&C combined).

- Step 8. Calculate each county's payment: multiply each county's adjusted share or 50% adjusted share by the full funding amount.

In essence, the new formula differed from the original SRS formula by basing half the payment on relative historic revenue and half on relative proportion of FS and O&C land, with an adjustment based on relative county income. This was done because the majority of payments under the original SRS went to Oregon, Washington, and California (more than 65% of payments in FY2006). Because of the altered allocation, several counties opted out of the amended SRS system, and others opted in.

FY2008-FY2010 Transition Payments FY2008-FY2010 Transition Payments

In lieu of the payments calculated using the formula described above, counties in eight states—California, Louisiana, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and Washington—received transition payments for three fiscal years, FY2008 through FY2010 (16 U.S.C. §7113). These counties were included in the calculations, but received payments of a fixed percentage of the FY2006 payments they received under |

Payment Election

Initially, each county could elect to receive the revenue-sharingbased payment or the SRS payment and could transmit that election to the respective Governor, who transmitted the elections to the appropriate Secretary (for FS, the Secretary of Agriculture; for BLM, the Secretary of the Interior).35

31 Eligible counties are those that choose to receive payments under this program; counties that choose to continue to receive payments under the original revenue-based programs are excluded from these calculations. Relative income is calculated using an income adjustment based on the per capita personal income in each county relative to the median per capita personal income in all eligible counties. Income data is calculated using the most recent data available from the Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. For a step-by-step guide on calculating payments, see FS’s SRS website at https://www.fs.usda.gov/working-with-us/secure-rural-schools/payments. 32 16 U.S.C. §7102(11). 33 IIJA, P.L. 117-58, §41202.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Interior).34 Although the election was good for two years, a county could opt to receive an SRS payment one year and the revenue-sharingbased payment the following year.36 However, the The authority to make such an election had expired at the end of FY2013, and an extension hashad not been included in the three reauthorizations that since have been enacted. following three reauthorizations. Essentially, Congress had frozen the payment elections each county made for the FY2013 payment and continued that election through the FY2020 payment. Those counties that opted to receive an SRS payment in FY2013 have continued to receive an SRS payment (for those years that payments arewere authorized). Counties; counties that opted to receive a revenue-sharingbased payment in FY2013 continuecontinued to receive the revenue-sharingbased payment and havedid not hadhave the opportunity to opt in to SRS. Most (90%) counties have elected to receive the SRS payment.

The FY2021 reauthorization ended the freeze on payment elections. Initially, the freeze on payment elections was set to end for the FY2023 payment, but Congress enacted legislation removing the sunset date on the payment freeze.35 Payment Allocations: Title I, Title II, and Title III

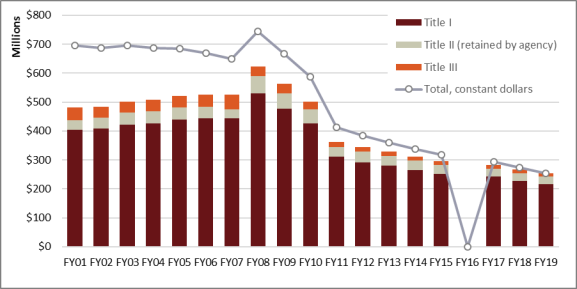

The SRS payment is divided into three parts, based on three of the titles in the SRS statute (see Figure 2 and Table 3). There are different requirements for how the payment is allocated among the three titles, depending on the payment amount a county is set to receive (see Table 3 for descriptions). Since the original authorization, Congress has modified the required allocations as well as the authorized uses of Title II and Title III funds.

Figure 2. FS and BLM Total Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments by Title (FY2001-FY2019) |

|

oc-lands.

34 16 U.S.C. §§7112(b)(1)-(2). Election submissions must be submitted to the respective Secretary by August every two years. If no election is made, counties receive an SRS payment.

35 The timing of the reauthorization of SRS payments as enacted in IIJA in November 2022 was after the August deadline specified in statute for making payment elections for the following two years. P.L. 117-102, however, allowed for a payment election to be made for FY2021.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 17 link to page 30 link to page 30 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Notes: FS = Forest Service; BLM = Bureau of Land Management. Some years reflect sequestration. The bars reflect nominal |

Regardless of the allocation, however, the bulk of each county'’s payment is allocated to Title I payments, and those funds are to be used in the same manner as the revenue-sharingbased payment (for roads and schools purposes for the FS payment; schools, roads, bridges, and highways for the CBWR lands; or any governmental purpose for the O&C lands). The Title II payment is not made to the county, but is retained by the relevant federal agency to be used for projects on the federal lands within the county and supported by local Resource Advisory Committees (RACs; see " “Resource Advisory Committees (RACs)" ” for further information). The Title III payment is made to the county, and the funds are to be used for specified county projects, such as community wildfire preparedness planning and to reimburse county expenditures for emergency services related to the federal lands.37

36

The authority to initiate projects under Title II or Title III expires on September 30, 20222025; project funds not obligated by September 30, 20232026, are to be returned to the Treasury.37

Table 3. Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Title Allocations

SRS Payment

Use of Funds

Allocation Requirements

Title I

Same as specified in the revenue-based, are to be returned to the Treasury.38 The authority for RACs to initiate projects and to obligate Title II funds had expired at the end of FY2013 and FY2014, respectively, but has been reauthorized and extended in each of the three previous SRS reauthorizations.

|

SRS Payment |

Use of Funds |

Allocation Requirements |

Title I Secure Payments |

| 80%-85%, except counties with minor distributions (less than $100,000) may allocate up to 100% |

Title II Special Projects on Federal Lands |

(less than $100,000) may

§7112d(1)(A))

allocate up to 100%

Title II

Funds may be used on projects on or to benefit the federal

0%-20%

Special Projects on

land within the county as suggested or approved by

Federal Lands

Resource Advisory Committees (RACs). At least 50% of the funds should be for projects primarily dedicated to road

maintenance or decommissioning or stream and watershed restoration. Up to 10% of the funds may be used to cover administrative expenses for RAC operations.a The authority to initiate projects expires at the end of |

0%-20% |

Title III County Funds |

Funds may not be used for lobbying activities.b The authority to initiate projects expires at the end of |

0%-20% for all other counties |

Source: CRS, compiled from 16 U.S.C. §§7101-7153.

Notes: The authorized uses and allocation requirements are as of the FY2019 reauthorization (P.L. 116-94, , Division H, Title III). The allocation requirements are codified at 16 U.S.C. §7112d(1). Counties may also allocate up to 20% of the payment to be returned to the Treasury (16 U.S.C. §§7112(d)(1)(B)(iiii i), 7112(d)(1)C(iiii i)). a. )).

a. Prior to FY2017, a portion of the Title II funds was also to be used for a program piloting the use of

separate contracts for the harvesting and sale of merchantable material. This requirement was removed in the FY2017 reauthorization (P.L. 115-141, Division O, §401(b)(1)).

b.

b. Prior to FY2008, Title III funds were not available for training and equipment costs or law enforcement

patrols but could have been used for other activities, such as for reimbursing costs associated with community service work centers, acquiring conservation or access easements, or conducting forestry education programs. The authorized uses and prohibitions were subsequently amended in several of the reauthorizations, starting in FY2008 (P.L. 110-343, §601) and most recently in the FY2017FY2021 reauthorization (P.L. 115-141(P.L. 117-58, Division O, §402).

c. D, §41202).

c. Prior to FY2008, all counties had the option to allocate up to 20% of their payment to Title III. This

requirement was added in the FY2008 reauthorization (P.L. 110-343, §601).

, §601).

In the original SRS authorization, counties with minor distributions (less than $100,000 in annual payments) could allocate 100% of the payment to Title I purposes. Counties receiving more than $100,000 in annual payments, however, could allocate only 80%-85% of their payment to Title I. The remaining 15%-20% of the payment could be allocated to Title II or Title III purposes, or the funds could be returned to the Treasury.

The allocation requirements were changed, however, in the FY2008 reauthorization.3938 Starting in FY2008, counties with modest distributions (annual payments between $100,000 and $350,000) could continue to allocate any portion of the remaining 15%-20% to Title II or Title III, as previously authorized. Counties with distributions above $350,000 were limited to allocating up to 7% of the payment to Title III. (Counties with minor distributions could continue to allocate 100% of the payment to Title I.)

The legislative text was also changed in the FY2017 reauthorization by defining counties with major distributions (payments more than $350,000 annually), but this did not result in any substantive changes to the allocation system.40 In the previous three reauthorizations, however, Congress has continued the payment allocations the counties made for the FY2013 payment. This means that counties have had the same payment allocations since that time and have not had the option to make any changes.

39

The authority to make changes to a county’s payment allocations was frozen from FY2013 through the FY2020 payment similarly to how the payment election decisions were frozen. The FY2021 reauthorization ended the freeze on payment allocations.40

38 P.L. 110-343, §601. 39 P.L. 115-161, Division O, §401(a)(3)(C). 40 Initially, the reauthorization enacted in IIJA would have set the payment allocations for the FY2021 payment at the default allocation (80% to Title I; 20% to Title II). Similar to the issue with payment elections, this was a function of (continued...)

Congressional Research Service

13

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Resource Advisory Committees (RACs)

Resource Advisory Committees (RACs)

SRS authorized both FS and BLM to establish RACs to improve collaborative relationships and to provide recommendations for Title II projects.4141 Both agencies had established advisory committees for various purposes prior to the enactment of SRS. For instance, BLM'’s preexisting advisory councils in Oregon are charged with administering the duties of the RACs as established by SRS.4242 RACs also must operate in accordance with the provisions of the Federal Advisory Committee Act.4343 Pursuant to SRS, each unit of eligible federal land has access to a RAC, although the Secretary concerned may combine RACs as needed. For example, a single RAC may cover multiple national forests, or a single RAC may cover part of a national forest while other RACs cover the rest.44

44

RACs generally must consist of 15 members appointed by the respective Secretary and representing a broad and balanced range of specified community interests (i.e., 5 members each from user interests, environmental interests, and the general public). A majority of the members must be present for a meeting to achieve a quorum, and a majority of the members representing each community interest must agree for a project to be approved and for project funds to be obligated.

Because many of the RACs have been unable to meet the membership or project agreement requirements, they have been unable to approve projects. In some cases, the funds were returned to the Treasury because they were not obligated before the authority to obligate funds expired or was reauthorized. For example, over $9 million of Title II funds were returned to the Treasury at the end of FY2014.45 However, the45

To address this issue, Congress has enacted several changes to the RAC membership requirements. The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the 2018 farm bill) authorized the Secretary concerned to reduce the membership requirement to nine members if there are not enough qualified candidates.46 In addition, the46 The 2018 farm bill also established a pilot program in Montana and Arizona to allow the Secretary concerned to name a designee to appoint RAC members through FY2023 (rather than requiring the Secretary to make the appointment).47

Payment Data and Analysis48

In any given year, a combination of different FS and BLM payments may be authorized and made. Some of these payments are made entirely to counties (e.g., the FS 25 Percent Payments), whereas the agencies retain a portion of the SRS payment. Because the agency, type of payment, and payment recipient vary by year, it may sometimes be unclear which data are being reported. This is particularly an issue for the FS payment because even when SRS payments are authorized, some counties may still receive a 25 Percent Payment. This is less of an issue for the BLM payment, however, because all 18 eligible counties have elected to receive the SRS payment.

|

Payment Terminology The following definitions reflect how the different payments are defined and referred to in this report (note that other sources may use different terms or report the data differently). For the payments in which both Forest Service (FS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands are applicable, the appropriate agency will be specified in the text. BLM payment reflects the payments made to the counties containing the Oregon and California (O&C) and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands as authorized for that year. For years prior to FY1993, this was the respective revenue-sharing payment; starting in FY1993, this was the BLM safety-net payment. For years starting in FY2001, however, this generally refers to the BLM Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (SRS) Title I and Title II payments. BLM total payment includes the BLM payment plus the SRS Title II payment retained by the agency. FS 25 Percent Payments are the revenue-sharing payments authorized through the Act of May 23, 1908. Data for the 25 Percent Payments may also include the Special Act Payments as specified, such as the Payments to Minnesota Counties. For the years FY1993 through FY2000, the data for the 25 Percent Payments also include the FS safety-net payments. FS payment reflects the payments authorized to be made to eligible counties for that year. Prior to FY2001, this includes the FS 25 Percent Payment and the FS safety-net payment. Starting in FY2001, this includes the FS revenue-sharing payment plus the SRS Title I and Title II payments, except in FY2016, when SRS payments were not authorized. FS total payment includes the FS county payment plus the SRS Title II payment retained by the agency. Revenue-sharing payment for the FS includes the 25 Percent Payments. For the BLM, this includes the O&C and CBWR payments. Safety-net payment includes payments made from FY1993 to FY2000 to certain counties in Washington, Oregon, and California for both FS and BLM (for Oregon, only BLM). SRS Title I, II, or III payment reflects the payment made pursuant to one or more of the SRS titles, as specified in the text. SRS total payment includes the sum of the Title I, Title II, and Title III payments. |

Table 4 and Table 5 appointments).47 The FY2021 reauthorization renamed the farm bill pilot as the Regional Pilot Program (RPP) and established a separate National Pilot Program (NPP) available for all other states (other than Montana and Arizona) through FY2023.48 The NPP allows the FS Chief or BLM Director to nominate RAC members, with automatic approval after 30 days if the applicable Secretary does not act on the nomination.

the timing of IIJA’s enactment relative to a statutory deadline for transmitting payment allocations. P.L. 117-102, however, allowed for counties to make payment elections for FY2021.

41 16 U.S.C. §7125(a)(2). 42 43 U.S.C. §1739. For more information on BLM’s Resource Advisory Councils (RACs), see https://www.blm.gov/get-involved/resource-advisory-council.

43 5 U.S.C., App. 2. For more information, see CRS Report R44253, Federal Advisory Committees: An Introduction and Overview.

44 For more information on FS RACs, see https://www.fs.usda.gov/main/pts/specialprojects/racs. 45 U.S. Department of Agriculture Office of Inspector General, Forest Service Secure Rural Schools Program, Audit Report 08601-006-41, August 2017. Hereinafter referred to as USDA OIG 2017.

46 P.L. 115-334, Title VIII, §8702. 47 P.L. 115-334, Title VIII, §8702. 48 P.L. 117-58, Division D, §41202.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Payment Data and Analysis49 In any given year, a combination of different FS and BLM payments may be authorized and made. Some of these payments are made entirely to counties (e.g., the FS 25 Percent Payments), whereas the agencies retain a portion of the SRS payment. Because the agency, type of payment, and payment recipient vary by year, it may sometimes be unclear which data are being reported. This is particularly an issue for the FS payment because even when SRS payments are authorized, some counties may still receive a 25 Percent Payment. This is less of an issue for the BLM payment, however, because all 18 eligible counties have elected to receive the SRS payment. Table 4 and Table 5 provide data on FS and BLM payments, respectively, since the first SRS payments were made in FY2001.

Payments made to counties under SRS are substantial and significantly greater than the revenue-sharingbased payments. For example, in FY2000, counties received an FS payment of $193.4 million (all figures in the text are in nominal dollars unless otherwise specified).4950 In FY2001, the first year SRS payments were made, counties received an FS payment of $361.8 million.5051 For the initial six years SRS was authorized, the counties received $359.1 million annually on average for FS SRS Title I and III payments. That was more than 55% above what the counties received annually on average for the six years prior to the enactment of SRS ($231.4 million).5152 Over the life of the program, the FS SRS Title I and III payments have averaged $325.9303.6 million annually, and the BLM SRS Title I and III payments have averaged $7263.7 million per year ($398.5 million combined, FS and BLM).52

. Table 4. Forest Service (FS) Payments

(nominal dollars in millions)

Secure Rural Schools (SRS)

Total FS

Payment

Receipt

25%

SRS

FS Total

(to

Yeara

Paymentsb

Title I

Title II

Title III

Total

Paymentc

Counties)d

FY2001

$15.6

$311.7

$24.9

$34.5

$371.1

$386.7

$361.8

FY2002

17.7

313.7

30.4

29.8

373.9

391.6

361.2

FY2003

11.2

326.6

32.6

29.5

388.8

400.0

367.3

FY2004

11.0

330.4

33.0

30.4

393.9

404.8

371.8

FY2005

8.8

340.0

33.6

31.3

404.9

413.7

380.0

FY2006

8.6

343.2

32.3

33.5

409.0

417.6

385.3

FY2007

8.1

345.0

26.5

36.6

408.1

416.2

389.7

49 Unless otherwise specified, FS data are from various reports available from https://www.fs.usda.gov/main/pts/securepayments/projectedpayments and BLM data from annual Official Payments Made to Counties reports, available from http://www.blm.gov/or/rac/ctypaypayments.php.

50 This figure includes the FS revenue-based payments as well as the safety-net payments, which were made only to certain counties in California, Oregon, and Washington.

51 This figure reflects an FS SRS Title I and III payment ($346.2 million) plus the FS revenue-based payment ($15.6 million). Including the SRS Title II payment ($24.9 million, retained by the agency), the FS SRS total payment in FY2001 was $371.1 million and the FS total payment was $386.7 million. Revenue-based data provided by FS Legislative Affairs office, 2005. FS SRS data from annual Forest Service report, All Service Receipts: Title I, II, and III Region Summary (ASR-18-3), available from http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/pts/home.

52 Including SRS Title II, the average SRS total payment for FS over the first six years the program was authorized (FY2001 through FY2007) was $392.8 million annually. The FS payments for the six years prior to the authorization of SRS (FY1995-FY2000) include the revenue-based payments plus the safety-net payments.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act: Background and Issues

Secure Rural Schools (SRS)

Total FS

Payment

Receipt

25%

SRS

FS Total

(to

Yeara

Paymentsb

Title I

Title II

Title III

Total

Paymentc

Counties)d

FY2008

11.8

439.8

51.8

26.3

517.9

529.7

477.9

FY2009

15.9

397.5

45.1

25.0

467.6

483.5

438.4

FY2010

15.9

353.4

42.0

20.4

415.8

431.7

389.7

FY2011

16.4

276.3

30.7

15.0

321.9

338.3

307.7

FY2012

17.4

259.9

31.9

14.1

305.9

323.3

291.4

FY2013

17.2

245.8

29.9

13.2

289.0

306.2

276.3

FY2014

17.2

233.0

28.3

12.6

273.9

291.0

262.7

FY2015

17.4

222.1

26.8

12.1

261.0

278.4

251.6

FY2016

64.4

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

64.4

64.4

FY2017

18.4

212.2

25.5

11.5

249.3

267.7

242.1

FY2018

18.3

202.2

24.4

11.0

237.5

255.8

231.5

FY2019

18.8

192.3

23.2

10.4

225.8

244.6

221.4

FY2020

18.6

182.7

22.0

9.9

214.7

233.3

211.2

FY2021

19.6

213.4

25.8

11.5

250.7

270.2

244.5

FY2022

19.0

202.6

23.6

12.9

239.0

258.1

234.5

Sources: FS FY2001-FY2005, FY2007 data from FS legislative affairs office; and FS FY2006, FY2008-FY2022 data (nominal dollars in millions)

|

|

Secure Rural Schools (SRS) |

|

| |||

|

Title I |

Title II |

Title III |

SRS Total |

||||

|

FY2001 |

$15.6 |

$311.7 |

$24.9 |

$34.5 |

$371.1 |

$386.7 |

$361.8 |

|

FY2002 |

17.7 |

313.7 |

30.4 |

29.8 |

373.9 |

391.6 |

361.2 |

|

FY2003 |

11.2 |

326.6 |

32.6 |

29.5 |

388.8 |

400.0 |

367.3 |

|

FY2004 |

11.0 |

330.4 |

33.0 |

30.4 |

393.9 |

404.8 |

371.8 |

|

FY2005 |

8.8 |

340.0 |

33.6 |

31.3 |

404.9 |

413.7 |

380.0 |

|

FY2006 |

8.6 |

343.2 |

32.3 |

33.5 |

409.0 |

417.6 |

385.3 |

|

FY2007 |

8.1 |

345.0 |

26.5 |

36.6 |

408.1 |

416.2 |

389.7 |

|

FY2008 |

11.8 |

439.8 |

51.8 |

26.3 |

517.9 |

529.7 |

477.9 |

|

FY2009 |

15.9 |

397.5 |

45.1 |

25.0 |

467.6 |

483.5 |

438.4 |

|

FY2010 |

15.9 |

353.4 |

42.0 |

20.4 |

415.8 |

431.7 |

389.7 |

|

FY2011 |

16.4 |

276.3 |

30.7 |

15.0 |

321.9 |

338.3 |

307.7 |

|

FY2012 |

17.4 |

259.9 |

31.9 |

14.1 |

305.9 |

323.3 |

291.4 |

|

FY2013 |

17.2 |

245.8 |

29.9 |

13.2 |

289.0 |

306.2 |