Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Changes from April 10, 2020 to July 28, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- The National Forest System

- Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber

- Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues

- Timber Harvests from the NFS

- Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests from NFS Lands

- Bureau of Land Management Lands

- Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber

- Planning, Sale Process, and Receipts

- Timber Harvests from BLM Lands

- Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests on BLM Lands

- Issues for Congress

Figures

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

July 28, 2021

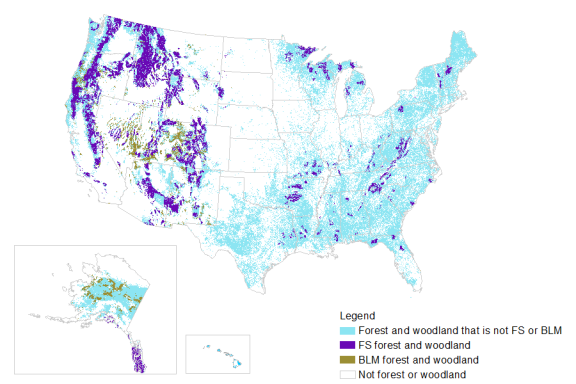

Congress has granted some federal land management agencies the authority to sell timber from federal lands. Two agencies, the Forest Service (FS) and the Bureau of Land Management

Anne A. Riddle

(BLM), conduct timber sales as an authorized use. Together, the FS and the BLM manage 76%

Analyst in Natural

of federal forest area. FS manages 144.9 million acres , while BLM manages 37.6 million acres .

Resources Policy

. The other major federal land management agencies, the National Park Service (NPS) and the Fish

and Wildlife Service (FWS), rarely conduct timber sales.

Lands managed by the FS, the National Forest System (NFS), are managed under a multiple use- -sustained yield model pursuant to the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960 (MUSYA). This statute directs FS to balance multiple uses of their lands and ensure a sustained yield of those uses in perpetuity. Congress, through the National Forest Management Act (NFMA), has directed FS to engage in long-term land use and resource management planning. Plans set the framework for land management, uses, and protection; they are developed through an interdisciplinary process with opportunities for public participation. In the case of timber, they describe where timber harvesting may occur and include measures of sustainable timber harvest levels. FS uses these plans to guide implementation of individual sales, which generate revenue. Congress has specified various uses for this revenue.

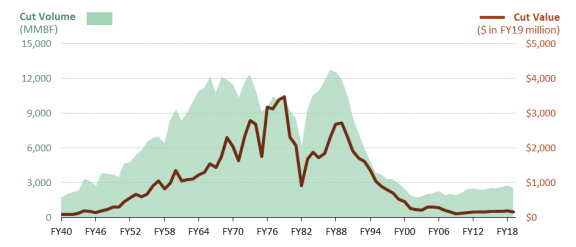

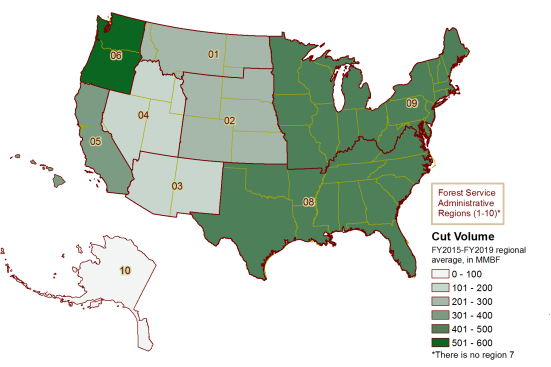

Timber harvest on FS lands has varied over time. FS harvest volumes in the 1940s were around 1-3 billion board feet per year. Annual harvest volumes rose from the 1950s through the 1980s, sometimes exceeding 10 billion board feet. Annual harvested volumes decreased in the early 1990s and have remained between 1.8 and 2.82.0 and 3.0 billion board feet since FY2003FY2010. The total dollar value of FS timber harvests generally rose from the early 1940s to over $3 billion in FY1979. Total value has been between $100 million and $300 million since FY2001. From FY2015 to FY2019, FY2016 to FY2020, the greatest average annual harvest volume on FS lands was from Oregon and Washington.

BLM lands are managed under a multiple use-sustained yield model pursuant to the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA). This statute directs BLM to balance multiple uses of their lands and ensure a sustained yield of those th ose uses in perpetuity. Congress has directed BLM to engage in long-term land use and resource management planning through FLPMA. Plans set the framework for land management, uses, and protection; they are developed made through an interdisciplinary process with opportunities for public participation. In the case of timber, they describe where timber harvesting may occur and contain measures of sustainable timber harvest levels. The FS and the BLM use these plans to guide implementation of individual sales, which generate revenue. Congress has specified various uses for this revenue.

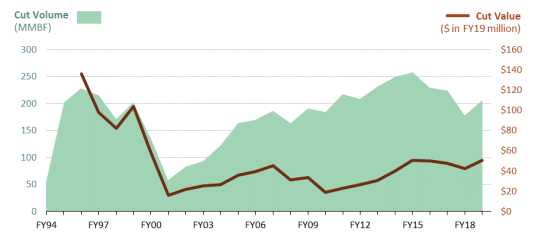

Although trends in timber activities on BLM lands are challenging to infer from the available data, volumes sold in the past appear to be larger than recent volumes offered for sale. Data on harvested volumes for the BLM are available from FY1994 onward. During that time, harvested volumes generally have been between 100 million and 300 million board feet annually, except in FY1994 and between FY2001-FY2003. Total harvest values have declined since the mid-1990s, and have generally been between $20 million and $5560 million annually since FY2011. From FY2015 to FY2019, FY2016 to FY2020, the greatest average annual harvest volume from BLM lands was from Oregon and Washington.

Congress has debated the appropriate balance of timber harvesting and other uses on federal lands. Determining the proportions of these uses, in whole and on individual lands, is challenging for land management agencies. Preferences for certain balances of these uses often stem from values about federal forests'’ purposes, such as consideration of economic, environmental, or recreational values. Debate has also centered on the relationship of timber harvesting levels to forest health, including whether changing harvest levels is a desirable forest management tool.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 10 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 5 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 18 link to page 17 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 20 link to page 23 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 The National Forest System .............................................................................................. 3

Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber................................................................... 4 Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues........................................................................... 4 Timber Harvests from the NFS .................................................................................... 7

Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests from NFS Lands..................................... 9

Bureau of Land Management Lands................................................................................. 10

Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber................................................................. 11 Planning, Sale Process, and Receipts .......................................................................... 11 Timber Harvests from BLM Lands ............................................................................. 13

Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests on BLM Lands ..................................... 15

Issues for Congress ....................................................................................................... 15

Figures Figure 1. FS, BLM, and Other Forest and Woodland............................................................. 2 Figure 2. Annual Cut Volume and Value, NFS ..................................................................... 8 Figure 3. Average Annual Cut Volume by NFS Region, FY2016-FY2020 .............................. 10 Figure 4. Annual Cut Volume and Value, BLM .................................................................. 15

Tables

Table 1. BLM Timber Sales, Historical ............................................................................. 14

Table A-1. Timber Revenue Funds: Forest Service ............................................................. 17 Table A-2. Timber Revenue Funds: Bureau of Land Management ......................................... 18

Appendixes

Appendix. Timber Receipt Funds..................................................................................... 17

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 20

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Introduction

Timber harvesting on federal lands is a long-

Forest Land, Woodland, and Timberland

standing activity which sometimes generates

Forest land, woodland, and timberland are al

controversy. Most timber harvesting on federal

classifications referring to lands dominated by trees.

lands occurs on lands directed to provide a

This report, and al reported data herein, use

regular output of multiple uses under current

definitions from the decennial assessment of forest resources prepared by the Forest Service as required

law. Determining the proportions of these

by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources

uses, in whole and on individual lands, is

Planning Act (RPA, P.L. 93-378).

chal enging for land management agencies.

Forest Land (also referred to as “forest” in this

Often at issue is the appropriate use of federal

report) is defined as land with at least 10% cover by

lands for timber harvesting under these

live trees, including lands that formerly had this tree

policies, including what amount of timber

cover and wil be regenerated.

harvesting should occur and what constitutes

Timberland is defined as forest land that is producing or is capable of producing crops of industrial wood and

proper balance among timber harvesting and

is not withdrawn from timber use by statute or

other uses.

regulation. Areas qualifying as timberland are capable of producing in excess of 20 cubic feet per acre per year

Congress has authorized timber harvesting on

of industrial wood. Timberland may be natural, if trees

certain federal lands under specified

are established by natural regeneration, or planted, if

circumstances. Most timber harvesting on

trees are established by human planting or seeding.

federal lands occurs on two land systems. The

Woodland is defined as land with sparse trees with a

majority of harvests occur on the National

tree canopy cover of 5% to 10%, combined with shrubs

Forest System (NFS), which is managed by

to achieve an overal cover of woody vegetation over

the Forest Service (FS) within the Department

10%. Woodland is not included in the definition of timberland because woodland is not general y capable

of Agriculture (USDA). Harvests also occur

of producing the timber volumes in the definition.

on the public lands managed by the Bureau of

However, timber harvesting could occur on woodland.

Land Management (BLM) within the

For further information regarding these definitions, see

Department of the Interior (DOI). The FS

Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al.,

manages 144.9 mil ionhealth, including whether changing harvest levels is a desirable forest management tool.

Introduction

|

Forest Land, Woodland, and Timberland Forest land, woodland, and timberland are all classifications referring to lands dominated by trees. This report, and all reported data herein, use definitions from the decennial assessment of forest resources prepared by the Forest Service as required by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA, P.L. 93-378). Forest Land (also referred to as "forest" in this report) is defined as land with at least 10% cover by live trees, including lands that formerly had this tree cover and will be regenerated. Timberland is defined as forest land that is producing or is capable of producing crops of industrial wood and is not withdrawn from timber use by statute or regulation. Areas qualifying as timberland are capable of producing in excess of 20 cubic feet per acre per year of industrial wood. Timberland may be natural, if trees are established by natural regeneration, or planted, if trees are established by human planting or seeding. Woodland is defined as land with sparse trees with a tree canopy cover of 5% to 10%, combined with shrubs to achieve an overall cover of woody vegetation over 10%. Woodland is not included in the definition of timberland because woodland is not generally capable of producing the timber volumes in the definition. However, timber harvesting could occur on woodland. For further information regarding these definitions, see Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A Technical Document Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessment. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (FS), GTR-WO-91, 2014. |

Timber harvesting on federal lands is a long-standing activity which sometimes generates controversy. Most timber harvesting on federal lands occurs on lands directed to provide a regular output of multiple uses under current law. Determining the proportions of these uses, in whole and on individual lands, is challenging for land management agencies. Often at issue is the appropriate use of federal lands for timber harvesting under these policies, including what amount of timber harvesting should occur and what constitutes proper balance among timber harvesting and other uses.

Congress has authorized timber harvesting on certain federal lands under specified circumstances. Most timber harvesting on federal lands occurs on two land systems. The majority of harvests occur on the National Forest System (NFS), which is managed by the Forest Service (FS) within the Department of Agriculture (USDA). Harvests also occur on the public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) within the Department of the Interior (DOI). The FS manages 144.9 million acres of forest, while the BLM manages 37.6 million acres of forest (see acres of forest, while

Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A Technical

the BLM manages 37.6 mil ion acres of forest

Document Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessment. U.S. Department of Agriculture

(see Figure 1).1 Together, FS and BLM forest

(USDA), Forest Service (FS), GTR-WO-91, 2014.

comprises 76% of federal forest area and 23% of all

of al forest in the United States. Within their respective forest, the FS has 96.1 millionmil ion acres of timberlands, and the BLM has 6.1 millionmil ion acres of timberlands. The United States has 765.5 million mil ion acres of forest, of which 514.4 millionmil ion acres is timberland and 57% is private. The United

States has 57.0 millionmil ion acres of woodland.2

2

Timber harvesting is the physical cutting and removal of trees or parts of trees from a given forested site. Harvested timber, or cut and removed trees, is the raw material for items made of wood, such as lumber, plywood, paper, and other products. Timber harvesting may occur on private, federal, or nonfederal publicly owned lands, and may be conducted by the landowner or

1 All following acreage data herein were generated as part of the forest and rangeland resources assessment process conducted by FS as required under the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA, P.L. 93-378). Data from Sonja Oswalt, Patrick Miles, and Scott Pugh, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2017: A Technical Docum ent Supporting the Forest Service 2020 Update of the RPA Assessm ent , Forest Service (FS), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2017, https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/program-features/rpa/docs/2017RPAFIAT ABLESFINAL_050918.pdf, hereinafter referred to as RPA 2017.

2 RPA 2017. T his source does not classify woodland by ownership.

Congressional Research Service

1

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

owned lands, and may be conducted by the landowner or by another entity they allowal ow to do so. Most timber harvesting in the United States is conducted on private lands: in 2011, 88% of timber harvests were conducted on private lands, and in 2012, 90%

of wood and paper products in the United States originated on private lands.3

in blue.

FS and BLM conduct timber sales as the most general way to allowal ow timber harvesting on their respective lands, although they may allowal ow harvesting in other ways.44 A timber sale is a formal process whereby an entity may purchase a contract to cut and remove specified timber. FS and BLM receive revenue from the sale of the contract. Information on timber harvesting in this report, such as harvested volume, harvested value, and other statistics, derives from FS and BLM

data and may include timber harvested through timber sales or other means.

3 Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A Technical Docum ent Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessm ent. FS, USDA, GT R-WO-91, 2014, and Sonja Oswalt and W. Brad Smith, U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends, FS, USDA, FS-1035, 2014.

4 For general authorities regarding timber sales on FS and BLM land, see “Statut ory Authorities for Harvesting T imber” in the FS and BLM sections. A detailed discussion of specific authorities allowing FS to sell or otherwise dispose of timber through various vehicles, or in specified circumstances, is beyond the scope of this report.

Congressional Research Service

2

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Both FS and BLM timber sale planning and implementation proceed under similar principles of achieving multiple use and sustained yield. Both agencies conduct timber harvesting for various purposes. Both plan long-term timber management by designating areas that can support sustainable timber harvest and calculating yields that can be taken without permanent impairment. In the short term, both agencies create plans for timber sales, determine the value of offered timber and specify what timber may be cut, and conduct sales in a competitive manner

open to the public.5

5

Timber harvesting may also occur on two other federal land systems, the National Park System,

managed by the National Park Service, and the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS), managed by the Fish and Wildlife Service (both agencies are within DOI). In the case of the National Park System, the Secretary may dispose of timber to control insects and diseases or to conserve natural or historic resources.66 In the case of the NWRS, the Secretary of the Interior may permit timber harvesting to achieve desired fish and wildlife habitat conditions. On both systems,

timber harvesting is rare, and harvested volumes are small.7

smal .7

This report provides an overview of timber harvesting on FS and BLM lands. The report describes general statutory authorities and regulations, planning activities, timber sales, and

trends in the volume and value of timber harvested, first from FS lands, and then for BLM lands.8 8 It concludes with a discussion of issues Congress has debated concerning timber harvesting and

federal lands.

The National Forest System

The National Forest System comprises nearly 193 millionmil ion acres. It is made up of 154 national forests, national grasslands, and other units such as research and experimental areas.9 9

Approximately 75% of national forest acreage is located in 15 states.1010 As discussed, the NFS

contains 144.9 millionmil ion acres of forest and woodland, of which 66% are considered timberland.11

11

5 For greater detail, see FS and BLM “Planning Rules and Process” sections. Some agency authorities and resources describe this this process; for BLM, see 43 C.F.R. §5410 and BLM Handbook H-5410-1, Annual Forest Product Sale Plan; for FS, see FS Manual 2431.04, Management of Tim ber Sale Program .

6 54 U.S.C. §100753. 7 For an overview of general purposes, authorities, and organization of the NWRS and the different units of the NPS, see respectively CRS Report R45265, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: An Overview, by R. Eliot Crafton, and CRS Report R41816, National Park System : What Do the Different Park Titles Signify? , by Laura B. Comay.

8 Unless otherwise specified, this report discusses harvested volume, also called cut volume, and harvested value, also called cut value. Harvested volume refers to the amount of timber physically removed in a given period of time. Volume of timber harvested in a given year typically differs from timber sold or timber offered for sale in that year. Harvested value refers to the amount paid for the cut timber after it is removed. 9 FS, USDA, Land Areas Report (LAR), 2018, T able 1, at https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2018/LART able01.pdf.

10 T hese states are FS regions 1 through 6, which includes the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

11 Data from RPA 2017. For more information on the NFS, see CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Managem ent: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber

Most of the lands contained in the modern Forest Service were reserved from the public lands in

the late 19th19th and early 20th20th centuries, in what were first called "forest reserves".12cal ed “forest reserves.”12 The forest reserves were initiallyinitial y managed by the DOI and later moved to the USDA and the Forest Service.1313 Through the Organic Administration Act, Congress specified that the purpose of these forests was to "“improve and protect the forest within the reservation … and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of the citizens of the United States,"” in

addition to protecting water flows.1414 The act authorized timber sales of "“dead, matured or large

growth of trees"” and set out procedures for conducting them.15

15

Congress expanded the purposes for the national forests, and developed management goals to

achieve those purposes, through the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960 (MUSYA).16 16 Congress added the provision of fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, energy and mineral development, and livestock grazing as official purposes of the national forests, in addition to timber harvesting and watershed protection. To supply these activities, management of the forests' ’ resources is to be organized for multiple uses in a "“harmonious and coordinated"” manner that

considers the combination of uses that best meets the needs of the American people, not that necessarily yields the largest dollar return or output. The act also directs a sustained yield of products and services, meaning high-level regular output in perpetuity without impairing the lands' productivity.17

lands’ productivity.17 Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues

Congress has directed FS to engage in long-term land use and resource management. Plans set the framework for land management, uses, and protection. They are developed through an

interdisciplinary process with opportunities for public participation. FS uses these plans to guide implementation of site-specific activities. In the case of timber, plans describe where timber harvesting may occur and include measures of sustainable timber harvest levels, and are used to

12 Congress granted the President the authority to establish forest reserves from lands in the public domain through the Forest Reserve Act of March 3, 1891, P.L. 51 -561. Congress repealed the President’s authority to establish forest reserves in certain states through the Agriculture Appropriations Act of March 4, 1907 (P .L. 60-242) and renamed the forest reserves “national forests.” Congress repealed the President’s authority to establish nat ional forests altogether with the passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA, P.L. 94-588; see “ Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues” in the FS section below). For example, in 1910, national forests comprised 172 million acres. See FS, USDA, Land Areas Report (LAR), 2018, T able 21 for data on historical NFS acres. 13 T he T ransfer Act of 1905 (33 Stat. 628, 16 U.S.C. §472) moved management of these lands to the Bureau of Forestry in the USDA. Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson changed the name of the Bureau of Forestry to the Forest Service through General Order No. 84, issued February 1, 1905. U.S. Congress, Senate, Rules and Regulations governing the Departm ent of Agriculture in its various branches, Furnished in response to a resolution adopted by the Senate of the United States , prepared by Government Printing Office, 59 th Cong., 2nd sess., 398 (Washington: GPO, 1907).

14 Act of June 4, 1897, Organic Administration Act, hereinafter referred to as the FS Organic Act (16 U.S.C. §473 -476); timber authorization in seventh and ninth paragraphs under “Surveying the Public Lands.” T he act was amended by the National Forest Management Act of 1976, described below in the FS “ Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues” section. 15 While the FS Organic Act provides a general authorization for harvesting timber, other laws have provided specific authorities. For example, salvage sale authority was provided in the National Forest Management Act, P.L. 94-588, among others. Detailed description of special authorities is beyond the scope of this report.

16 P.L. 86-517, 16 U.S.C. §§528 et seq. 17 16 U.S.C. §531b.

Congressional Research Service

4

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

harvesting may occur and include measures of sustainable timber harvest levels, and are used to guide implementation of individual sales. These sales generate revenues. Congress has specified

various uses for these revenues.

Congress directed the Forest Service to conduct long-term planning and management through the

passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA).1818 NFMA requires the FS to prepare a land and resource management plan—often called a "cal ed a “forest plan"”—for each NFS unit.19 19 These plans are to be revised at least every 15 years. The FS has issued regulations to implement the planning requirement—often called "cal ed “planning rules"”—and to establish the procedures for developing, amending, and revising forest plans. The first planning rule was issued in 1979 and

later revised; the current rule dates from 2012.2020 Forest planning and implementation generally general y proceed as described below. Forest Service timber planning and administration proceed under

general FS planning procedures.21

21

Forest plans guide management of the plan area by specifying objectives, standards, and guidelines for resources and activities. They contain certain components required by statute, such as components addressing provision of outdoor recreation, range, wildlife, fish, and timber. Among the most general required components addressing timber are requirements to identify areas and quantities for timber harvesting.2222 The FS must identify lands that may be not suited for timber production.23 All for

timber production.23 Al other lands in the NFS unit are considered suitable for timber production. The plan must contain the allowable sale quantity, the measure of timber that can be removed annuallyannual y without impairing future yield, although FS also considers other measures of sustainable yield in planning over various time horizons.24 The allowable24 The al owable sale quantity informs the amount of timber that can be removed annually annual y over a ten10-year plan period.2525 Plans are required to be developed with public participation and in accordance with various other administrative and

environmental statutes, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).26

26

18 P.L. 93-378 P.L. 94-588, 16 U.S.C. §1601 et al. (NFMA). NFMA amended the Forests and Rangelands Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA), P.L. 93-378, 16 U.S.C. §§1600 et seq.

19 NFS units may consist of more than one national forest. 20 36 C.F.R. §221. For greater detail on the history of the planning rule, see CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Managem ent: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover; see also Forest Service, “History of Forest Planning,” https://www.fs.usda.gov/main/planningrule/history. 21 Information in this section derives from a general survey of selected FS laws, regulations, and other authorities, such as manuals and handbooks. For FS timber planning and administration authorities, see 16 U.S.C. §472a, 16 U.S.C. §1611, 16 U.S.C. §1604, 36 C.F.R. §219, 36 C.F.R. §221, 36 C.F.R. §223, FS Manual Series 1900, FS Manual Series 2400, FS Handbook 1901.12, FS Handbook Series 2400. In general, if a c ited activity is addressed in statute, statute is cited, although other authorities may exist (for example, in regulation or agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives); if a cited activity is addressed in regulations, regulations are cited, although o ther authorities may exist (for example, in agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives); if a cited activity is addressed in agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives, at least one such authority is cited.

22 Statutes also require other components addressing timber harvesting in forest plans, such as components addressing circumstances wherein harvest levels may be increased based on intensified management practices, or components addressing circumstances under which harvests to regenerate even -aged stands may be used, among others. See, for example, 16 U.S.C. §1600(g)(3)(D-F), 16 U.S.C. §1600(m).

23 T he FS removes from consideration lands that cannot legally be harvested due to executive or legislative action, are not forested, have other desired conditions established in planning, or will be difficult to restock or damaging to harvest. 16 U.S.C. §1604(k).

24 16 U.S.C. §1611(a). 25 See FS Handbook 1901.20, Chapter 60, Forest Vegetation Resource Management, FS, Manual 2410, Timber Resource Managem ent Planning, and FS, FS Handbook 2409.13, Tim ber Resource Planning Handbook for a description of other concepts FS may use in planning for short - and long-term sustainable yield. 26 P.L. 91-190, 42 U.S.C. §§4321-4347; for an overview of NEPA, see CRS Report RL33152, The National

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 20 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Forest plans may consider harvesting for various purposes—for example, to produce timber or to achieve and maintain desired resource conditions, such as habitat improvement, fire risk reduction, and sanitation.2727 If the forest plan identifies lands as suitable for timber production, the plan must address timber harvesting on those lands.2828 If the forest plan considers timber harvesting for purposes other than producing timber, it must delineate areas where such activities

may occur. These areas may be identified by forest type, geographic area, or other criteria.29

29

FS conducts timber sales to achieve the objectives in the forest plan. FS establishes a sale schedule and timber sale project plan, which may include more than one timber sale.3030 The plan

estimates volume offered, acreage, and harvest methods for the relevant sales. Site-specific timber harvests must also comport with NEPA and relevant statutes, including any requirement for site-

specific environmental analysis and review.

Prior to an individual sale, FS marks and appraises the timber to be offered. FS may designate timber in one of three ways: physical marking, a written description of specific trees for harvest (called(cal ed description), or a written description of desired post-harvest stand characteristics (calledcal ed prescription).3131 FS creates a sale package, including a prospectus, sample contract, and other required documentation; some requirements are site-specific.3232 FS advertises the package at an

appraised starting price.3333 Interested parties may bid on the package. A contract is awarded to the highest bidder provided legal conditions are met.3434 The winning bidder conducts the timber harvest according to the terms—such as timeline, harvest method, and road construction conditions—specified in the contract. Timber harvests must generallygeneral y be completed in 3 years,

with a maximum term of 10 years.35

35

Timber sales generate revenue, and disposition of this revenue depends on several factors. Congress has established several funds for FS to retain and use timber sale receipts. Depending on the type of sale, among other factors, FS may be required to make certain deposits to these

funds. If any portion of receipts are not required to be deposited, FS may distribute receipts among funds at their discretion, including depositing all al revenue in a single fund. The money in these funds may be used by the FS for a variety of purposes, sometimes without further appropriation (i.e., as mandatory appropriations).36 See36 See Table A-1 for a list of these funds. A more Environm ental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Im plementation, by Linda Luther.

27 36 C.F.R. §219.11. 28 36 C.F.R. §219.11(b). 29 FS, Manual 1920, Land and Resource Management Planning and FS, FS Handbook 1909.12, Land and Resource Managem ent Planning Handbook.

30 FS, Manual 2431.04, Management of Timber Sale Program. 31 In 2014, P.L. 113-79 allowed the FS to denote trees by description or prescription. Before this, trees could only be denoted by physical marking. 16 U.S.C. §472a(g).

32 For example, if revenue will be deposited into a specific fund, additional documentation may be required in the package. FS, Manual 2430, Com m ercial Tim ber Sales, and FS, Handbook 2409.18, Tim ber Sale Preparation Handbook.

33 16 U.S.C. §472a(d). 34 16 U.S.C. §472a(e). 35 16 U.S.C. §472a(c). 36 For information on FS funds and receipts, see the “Revenue, Receipts, and T ransfers” section of the annual FS Budget Justifications, e.g., p. 12 of the FY2021 Budget Justification at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/usfs-fy-2021-budget -justification.pdf. FS allocates some revenues to entities as required under revenue-sharing programs, generally states or local governments. T he relationship between allocation of revenue in this manner and deposits into timber revenue funds is determined by law. A detailed discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this report. For more information on some revenue-sharing programs, see CRS Report RL31392, PILT

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 11 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Table A-1 for a list of these funds. A more detailed discussion of revenue levels, expenditures, and issues related to FS timber revenue funds

is outside the scope of this report.

Timber Harvests from the NFS

Timber harvesting is one of many authorized uses of the NFS. The amount of timber harvested from the NFS, and its relative proportion of total U.S. timber supply, has fluctuated over time. This section provides an overview of timber volume harvested from the NFS, and value of those harvests, along with some economic and historical factors which may have contributed to

observed changes.

The volume of timber harvested from the national forests (and their precursors, the forest reserves) increased slowly from 1898 until the 1940s.3737 Most demand for wood was met by

private timberlands; by 1940, for example, FS lands supplied 2% of U.S. timber supply.38

38

In the post-World War II era, timber harvest volume from the NFS grew (seesee Figure 2).3939 The timber supply from private forestry was unable to keep pace with the increased demand, due in

part to high harvest levels during WWII.4040 In the 1950s, the FS began to raise harvest limits.41 41 Harvests rose from 1-3 billionbil ion board feet (abbreviated BBF) annuallyannual y in the early 1940s to more than 10 BBF in some years of the 1960s and 1970s.4242 According to historical data from one source, harvest from the NFS rose from 9% of total U.S. harvest in 1952 to 16% in 1962 and

1970, and 15% in 1976.43

43

Harvest volume declined from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. Harvest on FS lands shifted to more marginal timberlands; in part, clear-cutting in the previous decades had reduced tree volume available available for harvest in productive areas.4444 This period also coincided with recessions in 1980 and

1982, which may have reduced demand.

|

|

Legislative Affairs Office. Notes: MMBF stands for |

Timber harvests rose from the early 1980s to the early 1990s, sometimes reaching levels of over 12 BBF per year. These timber harvests coincided with the 1986 U.S. peak in per capita

consumption of wood products, driven in part by an increase in housing starts following the 1982 recession.45

recession.45 In 1986, timber harvests from the NFS were 13% of total U.S. timber harvests.

In the early 1990s, harvested timber volume began a sustained decrease. In 1991, the NFS

supplied 11% of total U.S. harvested timber, and in 1997, the NFS supplied 5% of total U.S. harvested timber.4646 In 2011, NFS supplied 2% of U.S. wood and paper products.4747 Numerous interrelated factors, including statutory, administrative, biological, and market influences, may have contributed to this decline. The effect of each individual factor is not settled, as is the effect of each factor over time. These factors occurred at varying points in time and may not coincide

directly with observed harvest level changes. Some sources have noted that statutory changes added complexity to forest management and increasing litigation frequency, while also increasing transparency and public participation.4848 Other sources have noted changing management priorities.49

45 James Howard and Kwameka Jones, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics, 1965 -2013, USDA, FPL-RP-679, 2016.

46 Calculation from historical national forest timber harvest data and h istorical U.S. timber harvest data presented in Richard Haynes (T echnical Coordinator), An Analysis of the Tim ber Situation in the United States: 1952 to 2050 , FS, USDA, PNW-GT R-560, 2003.

47 Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A Technical Docum ent Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessm ent. Forest Service (FS), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), GT R-WO-91, 2014

48 For a historical perspective of FS timber administration, and a description of changes following the enactment of statutes such as NFMA, see Herbert Kaufman, The Forest Ranger: A Study in Adm inistrative Behavior (Johns Hopkins Press, 1967), T erence T ipple and J. Douglas Wellman, “ Herbert Kaufman’s Forest Ranger T hirty Years Later: From

Simplicity and Homogeneity to Complexity and Diversity,” Public Administration Review 51(5), 1991, pp. 421-428, and Paul Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optim ism : Managem ent of the National Forests since World War Two (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994). For FS analysis of the effect of procedural requirements on NFS management, see

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 13 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

priorities.49 Others have noted decreasing domestic demand, volatile prices, and the prevalence of less valuable timber due to high harvest levels in previous decades.5050 The listing of the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) under the Endangered Species Act in 1990 is often

discussed in regard to declining timber harvest levels.51

51

Harvested volumes have consistently been between 2 BBF and 3 BBF annuallyannual y from FY2004 onward. In FY2019FY2020, approximately 2.6 BBF were harvested from FS lands. Although the national timber market in the United States was affected by the 2008 housing market collapse and the subsequent decline in demand, timber volumes harvested from FS experienced relatively little

change in volume, for unclear reasons.52

In FY201952

In FY2020 dollars, harvest values from approximately FY2000 onward are similar to harvest values in the early 1940s. Harvest values generallygeneral y increased from the early 1940s to a peak of

approximately $3.5 billion (FY2019bil ion (FY2020 dollars) in FY1979, before a decline through FY1982. They rose again thereafter, reaching another peak of approximately $2.7 billion (FY20198 bil ion (FY2020 dollars) in FY1989, before again declining. Values from FY2001 onward have generallygeneral y been between approximately $100 million mil ion and $300 million mil ion in FY2019 dollars. In FY2019FY2020, cut value was approximately $166.8 million139.1 mil ion. FS harvest value declined during the recession and housing

collapse of 2008. Harvest value may vary due to quality, species, and age class of offered timber

and timber market conditions, and is correlated with volume harvested.

Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests from NFS Lands

FS harvest volume differs by region; these differences mirror the major production regions in private forestry (seesee Figure 3). FS Region 6 (the Pacific Northwest), Region 8 (the Southeast),

and Region 9 (the North), are the three largest producing regions in both private and public forestry.5353 In general, harvest volume and value by region is a function of many complex factors,

USDA, FS, The Process Predicam ent: How Statutory, Regulatory, and Adm inistrative Factors Affect NFS Managem ent, 2002. For a description of some changes to FS litigation patterns over time, see Robert Malmsheimer, Denise Keele, and Donald W. Floyd, “ National Forest Litigation and the U.S. Court of Appeals,” Journal of Forestry, vol.10, no.20 (2004), pp. 20-25, and Amanda Miner, Robert Malmsheimer, and Denise Keele, “ T wenty Years of Forest Service Land Management Litigation,” Journal of Forestry, vol. 112, no. 1 (2014), pp. 32-40. 49 For example, see Dale Bosworth and Hutch Brown, “After the T imber Wars: Community -Based Stewardship,” Journal of Forestry, vol. 105, no. 5 (2007), p. 271, and George Hoberg, “ T he Emerging T riumph of Ecosystem Management: T he T ransformation of Federal Forest Policy,” in Western Public Lands and Environmental Politics, ed. Charles David, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2018), pp. 55-86.

50 For information on market changes over time, see James Howard and Kwameka Jones, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consum ption, and Price Statistics, 1965 -2013, USDA, FPL-RP-679, 2016; Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A T echnical Document Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessment. FS, USDA, GT R-WO-91, 2014; and Paul Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optim ism : Managem ent of the National Forests since World War Two (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994). For perspectives on the relationship between timber availability and timber harvest trends before 2000, see Roger Sedjo (ed.), A Vision for the Forest Service: Goals for Its Next Century (Washington, DC: 2000). 51 See Steven Lewis Yaffee, The Wisdom of the Spotted Owl: Policy Lessons for a New Century (Washington, DC: Island Press, 1994) for a history of the listing of the spotted owl. For more information on the Endangered Species Act, see CRS Report R46677, The Endangered Species Act: Overview and Im plem entation , by Pervaze A. Sheikh, Erin H. Ward, and R. Eliot Crafton.

52 T he national timber market includes demand and supply from public and private sources. T he housing industry is the single largest consumer of wood products in the United States. For an overview of U.S. timber consumption, including discussion of timber consumption by sector, see James Howard and Kwameka Jones, U.S. Tim ber Production, Trade, Consum ption, and Price Statistics, 1965-2013, USDA, FPL-RP-679, 2016. 53 James Howard and Kwameka Jones, U.S. Timber Production, Trade, Consumption, and Price Statistics, 1965 -2013, USDA, FPL-RP-679, 2016.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 14

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

In general, harvest volume and value by region is a function of many complex factors, including the dominant timber type, age class, and condition; the suitability of FS sites for harvest

operations; the legal limitations on land uses; and the status of the local forest products industry.

Figure 3. Average Annual Cut Volume by NFS Region, |

|

FY2016-FY2020

Source: CRS. Calculation from Forest . Notes: MMBF = |

Bureau of Land Management Lands

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers about 246 million mil ion surface acres of federal lands, almost entirely located in 12 western states.5454 As noted, about 37.6 millionmil ion acres of BLM lands are forest; of that, 16% is considered timberland.5555 The Oregon and California (O&C) lands,

which comprise approximately 2.6 millionmil ion acres, contain 2.4 millionmil ion acres of forest (see "“Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber,",” below, for a description of the O&C lands).5656 The transfer of the forest reserves to FS administration in the early 1900s reduced the amount of forest

land and timberland under BLM management today.

54 T he 12 states are Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. BLM lands in these states comprise 99% of BLM lands.

55 RPA 2017. 56 BLM, DOI, BLM Facts: Oregon-Washington, 2017.

Congressional Research Service

10

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber

The modern BLM was formed in 1946 to manage the public domain lands.5757 At its formation,

BLM had no general authority to harvest timber on those lands.5858 Congress authorized BLM to dispose of forest materials through the Materials Act of 1947.5959 Congress later elaborated BLM's ’s management responsibilities with the passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA).6060 Like the MUSYA'’s mandate for the FS, FLPMA requires BLM to manage the public lands for multiple use and sustained yield in a "“harmonious and coordinated"” manner that

considers the combination of uses that best meets the needs of the American people, not necessarily yields the largest dollar return or output. The act directs a sustained yield of renewable resources, meaning high-level regular output in perpetuity without impairing the lands' productivity.61

’

productivity.61

The O&C lands are lands in western Oregon managed according to their own establishing statutes, mostly by BLM. FS manages 492 thousand acres of the O&C lands, or 18% of this total area. The lands consist of several areas, the Oregon and California lands and the Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands, which were revested to the federal government following violation of grant terms.62

terms.62 They are usuallyusual y referred to collectively as "“O&C lands"” and often grouped for legislative legislative purposes. BLM or FS'’s mandate to sell sel timber on the O&C lands derives directly from the O&C lands'’ establishing statute. The O&C Act directs that O&C lands be managed for sustained yield of permanent forest production, watershed protection, recreation, and contributing

to the economic stability of local communities and industries.63

63 Planning, Sale Process, and Receipts

Congress has directed BLM to engage in long-term land use and resource management planning. .

Plans set the framework for land management, uses, and protection. They are developed through an interdisciplinary process with opportunitiesopportunities for public participation. BLM uses these plans to guide implementation of site-specific activities. In the case of timber, plans describe where timber harvesting may occur and include measures of sustainable timber harvest levels. They are used to guide execution of individual sales sales, which generate revenues. Congress has specified various uses

for these revenues.

57 60 Stat. 1097, 5 U.S.C. §403. 58 For more information on BLM authorities at its formation, see Paul W. Gates, History of Public Land Law Development, written for the Public Land Law Review Commission (Washington, DC: GPO, November 1968), pp. 610-622 ; and James Muhn, Hanson R. Stuart, and Peter D. Doran, Opportunity and Challen ge: T he Story of BLM (Washington, DC, 1998). 59 61 Stat. 681, 30 U.S.C. §§601-604. While the Materials Act provides a general authority to conduct timber sales, other special authorities exist: for example, the salvage sale authority provided in the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act for FY1993 (P.L. 102-391). Detailed description of these special authorities is beyond the scope of this report.

60 P.L. 94-579, 43 U.S.C. §§1701 et seq. 61 43 U.S.C. §1702e(h). 62 T he CBWR lands were established by 40 Stat. 1179, which is not classified in the U.S. Code. T he Oregon and California lands were established by 50 Stat. 874; 43 U.S.C. §§2601-2634. For a more detailed history of the lands, see CRS Report R42951, The Oregon and California Railroad Lands (O&C Lands): Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover, and BLM, O&C Sustained Yield Act: the Land, the Law, the Legacy, http://www.blm.gov/or/files/OC_History.pdf.

63 50 Stat. 874; 43 U.S.C. §2601.

Congressional Research Service

11

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

BLM timber planning and administration follow general BLM land use planning procedures.64BLM timber planning and administration follow general BLM land use planning procedures.64 Through FLPMA, Congress directs BLM to develop, maintain, and revise plans for managing public lands. BLM issued the first regulations to implement the planning requirement in 1979, and subsequently revised them; the current BLM planning rule dates from 2005.6565 Plans must be developed with public participation and in accordance with various other administrative and

environmental statutes (e.g., NEPA).66

66

Under BLM'’s planning rule, resource management plans remain in effect indefinitely. They are to include monitoring and evaluation standards, and are to be amended or revised when

circumstances warrant.6767 The planning rule directs BLM to identify indicators that describe the desired forest outcomes in the plan area. BLM is to identify a suite of management actions to achieve those outcomes, including identifying sustained yield areas, areas that could support long-term timber harvest.6868 BLM personnel determine a harvest level for these areas that can be maintained without permanent impairment; this harvest level is known as the allowable sale quantity.69 Allowable

quantity.69 Al owable sale quantity is measured for a ten-year period.70

70

In addition, BLM generallygeneral y makes annual forest product sale plans.7171 These plans contain estimates of sale volume, acreage, and permitted harvest methods for any sales proposed for the year.72

year.72 Site-specific timber harvests must comport with NEPA and relevant statutes, including any additional

additional requirement for site-specific analysis and review.

To conduct an individual sale within the plan, BLM designates the timber for sale and appraises

the value of the timber.7373 BLM timber may be designated by physical marking or by enclosing timber in a sale boundary.7474 BLM prepares a sale contract, along with a prospectus describing the sale.7575 The sale is advertised at an appraised starting price.7676 Interested parties may bid on the

64 Information in this section derives from selected BLM law, regulation, and other authorities, such as manuals and handbooks. For BLM timber planning and administration authorities, see 43 U.S.C. §§1701 et seq., 43 U.S.C. §2601, 43 C.F.R. §1601.0-1601.8, 43 C.F.R. §5003.1-5511.5, BLM Manual Series MS-5000 through MS-5420, BLM Manual MS-1601, BLM Handbook 5000 Series, and BLM Handbook H-1601-1. In general, if an activity is addressed in statute, statute is cited, although other authorities may exist (for example, in regulation or agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives); if an activity is addressed in regulations, regulations are cited, although other authorities may exist (for example, in agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives); if an activity is addressed in agency handbooks, manuals, or other directives, at least one such authority is cited. 65 43 C.F.R. §1610. 66 P.L. 91-190, 42 U.S.C. §§4321-4347; for an overview of NEPA, see CRS Report RL33152, The National Environm ental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Im plementation, by Linda Luther.

67 43 C.F.R. §1610.4-9. 68 BLM Manual MS-5251, Timber Production Capability Classification. 69 Allowable sale quantity (ASQ) is the harvest level that can be maintained without decline over the long term if the schedule of harvests and regeneration is followed. An ASQ is not a co mmitment to offer for sale a specific level of timber volume every year. Volumes offered for harvest sale may vary in the short term if sustained yield is maintained. BLM Manual MS-5000, Forest Managem ent.

70 BLM Manual MS-5000, Forest Management. 71 43 C.F.R. §5410. 72 BLM Handbook H-5410-1, Annual Forest Product Sale Plan. 73 43 C.F.R. §5420. 74 BLM Manual M-5420, Preparation for Sale. 75 43 C.F.R. §5430.0-1. A prospectus is a descriptive document describing the sale in greater detail than the advertisement, but in less detail than the contract. It is available to interested bidders on request.

76 43 C.F.R. §5430.0-1.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 21 link to page 18 link to page 17 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Interested parties may bid on the contract. A contract is awarded to the highest bidder provided legal conditions are met.7777 The winning bidder conducts the timber harvest according to the terms specified in the contract, such as timeline and harvest method. Timber harvests must generallygeneral y be completed in three years, but

may be extended under certain circumstances.78

78

Timber sales generate revenues, and disposition of these revenues depends on a number of factors. Congress has established several funds for timber sale revenues. Depending on the type of sale and the originating lands, BLM may be required to make certain deposits to these funds. If any portion of revenues are not required to be deposited, BLM may allocateal ocate those revenues

among funds at its discretion, including depositing all al revenues in a single account. Some funds are permanently appropriated to BLM and may be used without further congressional action (i.e. as mandatory appropriations).79 See79 See Table A-2 for a list of these funds. A more detailed discussion of funding levels, expenditures, and issues related to BLM timber revenue funds is

outside the scope of this report.

Timber Harvests from BLM Lands

Timber harvesting is one of many authorized uses of BLM lands. Long-term historical data

regarding BLM timber harvesting is unavailable. Other data on past timber program activity show that BLM timber harvesting may have changed over time. This section provides data on timber offered for sale, timber sold, and timber harvested from BLM lands at various points in time, along with some economic and historical factors which may have contributed to observed changes.

changes.

Data on cut timber volume from BLM lands is available from FY1994 onward (seesee Figure 4). While complete historical cut data is unavailable prior to FY1994, some data exists about past sales (seesee Table 1). The intermittent nature of this data challengeschal enges drawing conclusions about

larger trends in these periods, especiallyespecial y in the missing decades. In addition, these data refer to either timber sold or timber offered for sale, which differs from volume of timber cut.8080 However, as an approximate comparison, the data show that the volumes sold prior to FY1990 are large compared to recent volumes offered for sale. Observers confirmed a decline in public domain timber offered for sale beginning in 1991, though the investigation did not consider the O&C

lands.81

77 43 C.F.R. §§5440-5450. 78 43 C.F.R. §5463.1, 43 C.F.R. §5473. 79 For information on BLM funds and receipts, see the annual BLM Budget Justifications on the Department of the Interior’s Budget Office website, e.g., https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2020. BLM allocates some revenues to entities as required under revenue-sharing programs. BLM allocation of revenue is determined by law, including law pertaining to individual funds and activities. A detailed discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this report. For more information on some revenue-sharing programs, see CRS Report RL31392, PILT (Paym ents in Lieu of Taxes): Som ewhat Sim plified, by Katie Hoover, and CRS Report R41303, The Secure Rural Schools and Com m unity Self-Determ ination Act: Background and Issues, by Katie Hoover.

80 Volume of timber offered for sale, volume of timber sold, and volume of timber cut typically differ in a given year. Volume of timber offered for sale differs from volume of timber sold in that not all offered sales may be completed. Both differ from timber cut for a number of reasons. For example, purchasers may have a period of several years to cut timber, they may not fully execute the cut specified in the contract, or disturbances may alter volume between the time the sale is made and the harvest is executed. 81 U.S. General Accounting Office, BLM Public Domain Lands: Volum e of Timber Offered for Sale Has Declined Substantially since Fiscal Year 1990, GAO-03-615, June 2003.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 18 link to page 18 Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Table 1. BLM Timber Sales, Historical

Timber Volume Sold

Timber Volume Offered

Fiscal Year

(MMBF)

for Sale (MMBF)

1948

431.8

NA

1951

499.5

NA

1960

359.8

NA

1970

1787.5

NA

1980

1196.8

NA

1990

1221.8

NA

2000

NA

277.8

2010

NA

92.5

Source: CRS. Sum of timber volume sales from public lands and O&C lands found in Report of the Director, 1948; Report of the Director, 1951; Statistical Appendix, Annual Report, 1960; and for each of Public Land Statistics, 1970; Public Land Statistics, 1980; Public Land Statistics, 1990; Public Land Statistics, 2000; and Public Land Statistics, 2010. Notes: These data report either volume of timber offered for sale, or volume of timber sold. Volume of timber offered for sale differs from volume of timber sold in that not al timber offered for sale beginning in 1991, though the investigation did not consider the O&C lands.81

|

Fiscal Year |

Timber Volume Sold (MMBF) |

Timber Volume Offered for Sale (MMBF) |

|

1948 |

431.8 |

NA |

|

1951 |

499.5 |

NA |

|

1960 |

359.8 |

NA |

|

1970 |

1787.5 |

NA |

|

1980 |

1196.8 |

NA |

|

1990 |

1221.8 |

NA |

|

2000 |

NA |

277.8 |

|

2010 |

NA |

92.5 |

Source: CRS. Sum of timber volume sales from public lands and O&C lands found in Report of the Director, 1948; Report of the Director, 1951; Statistical Appendix, Annual Report, 1960; and for each of Public Land Statistics, 1970; Public Land Statistics, 1980; Public Land Statistics, 1990; Public Land Statistics, 2000; and Public Land Statistics, 2010.

Notes: These data report either volume of timber offered for sale, or volume of timber sold. Volume of timber offered for sale differs from volume of timber sold in that not all offered sales may be purchased. Thus, volume of timber offered for sale is generally general y greater than volume of timber sold. BLM data sources reported timber volume sold in 1948, 1951, 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990. BLM data sources reported timber offered for sale in 2000 and 2010. "NA"“NA” means data were not reported in that year.

Volumes harvested from BLM lands were between 100 and 300 MMBF from FY1995 to FY2000 and from FY2004 to FY2019 (seesee Figure 4). Harvests were lower in FY1994 and between

FY2001 and FY2003. Harvested volumes have shown a generallygeneral y increasing trend since FY2001, with the largest recently recorded harvest in FY2015 (about 258 MMBF). Like the NFS, harvests from BLM lands during the recession and housing market collapse of 2008 experienced relatively little little change in volume, for unclear reasons. In FY2019, BLM harvested about 206 MMBF.

FY2020, about 239 MMBF were harvested from

BLM lands.

Data on cut timber value from BLM lands is available from FY1996 onward (seesee Figure 4). Total value of harvests has declined since FY1996. Harvest values have generallygeneral y increased since the low value of approximately $15.4 million mil ion in FY2001, and have been between $20 million and $55 million mil ion and

$60 mil ion since FY2011 (FY2019FY2020 dollars). In FY2019FY2020, cut value was $50.3 million58.8 mil ion. Like the FS, BLM harvest value during the recession and housing market collapse of 2008 declined, but the relative change was small smal compared to the decreases of the late 1990s. Harvest value may vary due to the quality, species, and age class of offered timber as well wel as timber market conditions, and is correlated with harvested volume. BLM harvest values per unit of timber are

higher than FS values per unit, due to the dominant timber type harvested from BLM lands,

among other factors.82

82 T he great majority of timber harvested from BLM land is from the O&C lands (see “ T imber Harvests on BLM Lands”). O&C lands are dominated by Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), a species used extensively for timber.

Congressional Research Service

14

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Figure 4. Annual Cut Volume and Value, BLM

Source: CRS. FY2012-FY2020 data: BLM, Bureau Wide Timber Data, Transaction Reports, among other factors.82

|

|

Notes: Complete |

Geographic Distribution of Timber Harvests on BLM Lands

Most timber harvests on BLM lands are conducted on the O&C lands. From FY2014 to FY2018, the average harvested volume from O&C lands was 93% of the average total volume. The large proportion of volume harvested from O&C lands reflects the forest cover and type, dominant use for forest production, and the size of the forest industry in the Pacific Northwest.8383 As with the NFS, in general, BLM harvest volume and value is a function of many complex factors, including

the dominant timber type, age class, and condition; the suitability of sites for harvest operations;

legal limitations on land uses; and the status of the local forest products industry.

Issues for Congress

Management of federal lands for multiple uses and sustained yield is challengingchal enging, including balancing timber harvesting with other uses. Timber production from federal lands is driven by a complex interaction of environmental factors, market forces, and land management policies.

Under current law, efforts to change harvest levels must comport with the provision of a sustained yield of multiple uses. Congress has sometimes considered legislation to prioritize or exclude some uses in a limited manner—in certain geographic regions, for example—but has not changed

these fundamental management concepts since their enactment in the 1960s and 1970s.

The public often expresses preferences for uses of federal forests, including with respect to timber harvesting. Some may support timber harvesting generallygeneral y, and believe the current levels of production are sufficient. Others may wish to see the levels of production increased or decreased,

83 T he largest forest producing regions in the United States are the Pacific Northwest and the Southeast. T he BLM does not manage any forestland in the Southeast.

Congressional Research Service

15

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

depending on their perspective. Those who support timber harvesting on federal lands may cite benefits to the local timber industry, a belief that harvesting is part of the core mission of federal forests, or a belief that timber harvesting is a tool for improving forest health conditions, among other reasons.8484 Proponents of timber harvesting on federal lands may also emphasize the role of timber harvesting in some forest-adjacent rural economies.85 85 Others may oppose timber harvesting due to concerns about ecological or human impacts: for example, they may cite beliefs

that timber sales have detrimental impacts on environmental quality, fish and wildlife habitat, forest character, recreation and tourism, or cultural and aesthetic values.86 86 Opponents may also

contend that conducting timber sales favors the timber industry over other interests.87

87

In addition to the themes identified above, Congress may also debate other issues related to federal timber harvests that are not discussed in detail in this report. For example, these include issues related to the disposition and use of timber sale revenues; the relationship between timber harvest planning and statutes such as NEPA and the Endangered Species Act (ESA); and special

harvest authorities, among others.

Appendix.

84 See Roger Sedjo, The Future of the Forest Service, Property and Environment Research Center, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2017; Greg Brown, “Relationships between spatial and non-spatial preferences and place-based values in national forests,” Applied Geography, vol. 44 (2013), pp. 1-11; and Greg Brown and Pat Reed, “Validation of a forest values typology for use in national forest planning,” Forest Science, vol. 46, no. 2 (2000), pp. 240-247. 85 For example, see U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Improving Forest Health and Socioeconomic Opportunities on the Nation’s Forest System , 114th Cong., 1st sess., 2015, S. Hrg. 114-262 (Washington: GPO, 2016).

86 Greg Brown, “Relationships between spatial and non-spatial preferences and place-based values in national forests,” Applied Geography, vol. 44 (2013), pp. 1-11; and Greg Brown and Pat Reed, “ Validation of a forest values typology for use in national forest planning,” Forest Science, vol. 46, no. 2 (2000), pp. 240-247. 87 See, for example, Mike Garrity, “T axpayer subsidized logging makes no sense,” Helena Independent Record, (2014).

Congressional Research Service

16

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Appendix. Timber Receipt Funds Timber Receipt Funds

The following tables list and describe the funds that receive timber sale revenues; the funds' ’ statutory authority is also shown. A detailed discussion of funding levels, expenditures, and issues

related to these funds is outside the scope of this report.

|

Name |

Description |

Authority |

|

Brush Disposal |

|

Act of August 11, 1916; 16 U.S.C. §490. |

Credits for Purchaser-Built Roads |

Purchasers elect for FS to build the |

National Forest Management Act, P.L. 94-588; 16 U.S.C. §472a(i). |

|

Knutson-Vandenberg (K-V) Fund |

Knutson-Vandenberg (K-V) Fund

The act authorizes FS to retain |

Knutson-Vandenberg Act, PL 71-319, as amended; 16 U.S.C. 576-576b. |

|

Salvage Sale Fund |

|

National Forest Management Act, P.L. 94-588; 16 U.S.C. §472a(h). |

|

Stewardship Contracting Fund |

|

Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA), P.L. 108-148, as amended; 16 U.S.C. §6591c. |

|

Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund |

|

Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996, P.L. 104-134 § 327; 16 U.S.C. §1611 note. |

Source: CRS. Table compiled using FS budget justifications from FY2010 onward; and David C. Powell, Powel , U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Forest Service, Fact Sheet: Forest Service Trust Funds, FS White Paper F14-SO-WP-SILV-17, UmatillaUmatil a National Forest, Pendleton, OR, last updated February 2014.

Notes: Funds are listed in alphabetical order by name of fund.

a. a. For more information on stewardship contracting, see CRS In Focus IF11179, Stewardship End Result

Contracting: Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, by Anne A. Riddle.

b. The sales were originally

b. The sales were original y made under the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act for FY1990 (

(P.L. 101-121) but were halted in 1992 due to a new Endangered Species Act listing in the region of the sales. The sales were reinstated under the 1995 Emergency Supplemental Appropriations and Rescissions Act (P.L. 104-19 § , §327). Prior to the passage of the Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations

Act of 1996, which authorized the Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund, revenues from the reinstated sales were disposed of as general timber receipts.

receipts.

|

Type of Land |

Name |

Description |

Authority |

|

Public Domain Lands |

Reclamation Fund |

|

Reclamation Act of June 17, 1902; 43 U.S.C. §391. |

|

Public Domain & O&C Lands |

Forest Ecosystem Health and Recovery Fund |

|

Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act for FY1993; P.L. 102-391. |

|

Public Domain Lands & O&C Lands |

Stewardship Contracting Excess Receipts |

|

Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA), P.L. 108-148, as amended; 16 U.S.C. §6591c. |

|

Public Domain Lands & O&C Lands |

Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund |

|

Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996, P.L. 104-134 § 327; 16 U.S.C. §1611. |

Source: Table compiled using BLM Budget Justifications from FY2010 onward.

Notes Notes: Funds are listed by the applicable lands. For each set of applicable lands, they are listed in alphabetical order by name of fund.

a. a. The 17 states are all al states west of the Mississippi, except Alaska and Hawaii and Hawai . Although statute specifies that monies received

monies received from 17 states are to be deposited in the fund, 99% of BLM land is located in 12 of those states. For more information on the Reclamation Fund, see CRS In Focus IF10042, The Reclamation Fund, by Charles V. Stern.

b.

b. For more information on stewardship contracting, see CRS In Focus IF11179, Stewardship End Result

Contracting: Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, by Anne A. Riddle.

c. The sales were originally

c. The sales were original y made under the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act for FY1990 (

(P.L. 101-121 ) but were halted in 1992 due to a new Endangered Species Act listing in the region of the sales. The sales were reinstated under the 1995 Emergency Supplemental Appropriations and Rescissions Act (P.L. 104-19 § , §327). Prior to the passage of the Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996, which authorized the Timber Sales Pipeline Restoration Fund, receipts from the reinstated sales were disposed of as general timber receipts.

Congressional Research Service

19

Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands

Author Information

Anne A. Riddle

Analyst in Natural Resources Policy

Disclaimer

This document was prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS serves as nonpartisan shared staff to congressional committees and Members of Congress. It operates solely at the behest of and under the direction of Congress. Information in a CRS Report should n ot be relied upon for purposes other than public understanding of information that has been provided by CRS to Members of Congress in

connection with CRS’s institutional role. CRS Reports, as a work of the United States Government, are not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Any CRS Report may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without permission from CRS. However, as a CRS Report may include copyrighted images or material from a third party, you may need to obtain the permission of the copyright holder if you wish to copy or otherwise use copyrighted material.

Congressional Research Service

R45688 · VERSION 6 · UPDATED

20 receipts.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

All following acreage data herein were generated as part of the forest and rangeland resources assessment process conducted by FS as required under the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA, P.L. 93-378). Data from Sonja Oswalt, Patrick Miles, and Scott Pugh, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2017: A Technical Document Supporting the Forest Service 2020 Update of the RPA Assessment, Forest Service (FS), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2017, https://www.fia.fs.fed.us/program-features/rpa/docs/2017RPAFIATABLESFINAL_050918.pdf, hereinafter referred to as RPA 2017. |

| 2. |

RPA 2017. This source does not classify woodland by ownership. |

| 3. |

Sonja Oswalt, W. Brad Smith, and Patrick Miles, et al., Forest Resources of the United States, 2012: A Technical Document Supporting the Forest Service Update of the 2010 RPA Assessment. FS, USDA, GTR-WO-91, 2014, and Sonja Oswalt and W. Brad Smith, U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends, FS, USDA, FS-1035, 2014. |

| 4. |

For general authorities regarding timber sales on FS and BLM land, see "Statutory Authorities for Harvesting Timber" in the FS and BLM sections. A detailed discussion of specific authorities allowing FS to sell or otherwise dispose of timber through various vehicles, or in specified circumstances, is beyond the scope of this report. |

| 5. |

For greater detail, see FS and BLM "Planning Rules and Process" sections. Some agency authorities and resources describe this this process; for BLM, see 43 C.F.R. §5410 and BLM Handbook H-5410-1, Annual Forest Product Sale Plan; for FS, see FS Manual 2431.04, Management of Timber Sale Program. |

| 6. |

54 U.S.C. §100753. |

| 7. |

For an overview of general purposes, authorities, and organization of the NWRS and the different units of the NPS, see respectively CRS Report R45265, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: An Overview, by R. Eliot Crafton, and CRS Report R41816, National Park System: What Do the Different Park Titles Signify?, by Laura B. Comay. |

| 8. |

Unless otherwise specified, this report discusses harvested volume, also called cut volume, and harvested value, also called cut value. Harvested volume refers to the amount of timber physically removed in a given period of time. Volume of timber harvested in a given year typically differs from timber sold or timber offered for sale in that year. Harvested value refers to the amount paid for the cut timber after it is removed. |

| 9. |

FS, USDA, Land Areas Report (LAR), 2018, Table 1, at https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2018/LARTable01.pdf. |

| 10. |

These states are FS regions 1 through 6, which includes the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. |

| 11. |

Data from RPA 2017. For more information on the NFS, see CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Management: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover. |

| 12. |

Congress granted the President the authority to establish forest reserves from lands in the public domain through the Forest Reserve Act of March 3, 1891, P.L. 51-561. Congress repealed the President's authority to establish forest reserves in certain states through the Agriculture Appropriations Act of March 4, 1907 (PL. 60-242) and renamed the forest reserves "national forests". Congress repealed the President's authority to establish national forests altogether with the passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA, P.L. 94-588; see "Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues" in the FS section below). For example, in 1910, national forests comprised 172 million acres. See FS, USDA, Land Areas Report (LAR), 2018, Table 21 for data on historical NFS acres. |

| 13. |

The Transfer Act of 1905 (33 Stat. 628, 16 U.S.C. §472) moved management of these lands to the Bureau of Forestry in the USDA. Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson changed the name of the Bureau of Forestry to the Forest Service through General Order No. 84, issued February 1, 1905. U.S. Congress, Senate, Rules and Regulations governing the Department of Agriculture in its various branches, Furnished in response to a resolution adopted by the Senate of the United States , prepared by Government Printing Office, 59th Cong., 2nd sess., 398 (Washington: GPO, 1907). |

| 14. |

Act of June 4, 1897, Organic Administration Act, hereinafter referred to as the FS Organic Act (16 U.S.C. 473-476); timber authorization in seventh and ninth paragraphs under "Surveying the Public Lands". The act was amended by the National Forest Management Act of 1976, described below in the FS "Planning, Sale Process, and Revenues" section. |

| 15. |

While the FS Organic Act provides a general authorization for harvesting timber, other laws have provided specific authorities. For example, salvage sale authority was provided in the National Forest Management Act, P.L. 94-588, among others. Detailed description of special authorities is beyond the scope of this report. |

| 16. |

P.L. 86-517, 16 U.S.C. §528 et seq. |

| 17. |

16 U.S.C. §531b. |

| 18. |

P.L. 93-378 P.L. 94-588, 16 U.S.C. §1601 et al. (NFMA). NFMA amended the Forests and Rangelands Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA), P.L. 93-378, 16 U.S.C. §§1600 et seq. |

| 19. |

NFS units may consist of more than one national forest. |

| 20. |