Global Economic Effects of COVID-19

Changes from March 26, 2020 to April 10, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Overview

- Estimated Economic Effects

- Policy Response

- Global Growth

- Global Trade

- Economic Policy Challenges

- Economic Developments

- Policy Responses

- The United States

- Monetary Policy

- Fiscal Policy

- Europe

- The United Kingdom

- Japan

- China

- Multilateral Response

- International Monetary Fund

- World Bank and Regional Development Banks

- International Economic Cooperation

- Estimated Effects on Developed and Major Economies

- Emerging Markets

- Looming Debt Crises

- Other Affected Sectors

- Conclusions

Figures

Tables

Summary

Since the CovidCOVID-19 outbreak was first diagnosed, it has spread to over 150190 countries and all U.S. states. The pandemic is having a noticeable impact on global economic growth. Estimates so far indicate the virus could trim global economic growth by at least 0.5% to 1.5%, but thecould rise to 2.0% per month if current conditions persist. Global trade could fall by 13% to 32%, depending on the depth and extent of the global economic downturn. The full impact will not be known until the effects of the pandemic peak. This report provides an overview of the global economic costs to date and the response by governments and international institutions to address these effects.

Overview

Since theThe World Health Organization (WHO) first declared CovidCOVID-19 a world health emergency in January 2020, the virus . Since the virus was first diagnosed in Wuhan, China, it has been detected in over 150 countries and all U.S. states.1 The infection has sickened more than 490,000190 countries and all U.S. states.1 In early March, the focal point of infections shifted from China to Europe, especially Italy, but by April 2020, the focus shifted to the United States, where the number of infections was accelerating. The infection has sickened over 1.5 million people, with thousands of fatalities. More than 80 countries have closed their borders to arrivals from countries with infections, ordered businesses to close, and instructed their populations to self-quarantine.2 After a delayed response, central banks have engaged in a, and closed schools to an estimated 1.5 billion children.2 In late January 2020, China was the first country to impose travel restrictions, followed by South Korea and Vietnam. Over the four-week period from mid-March to early April 2020, more than 17 million Americans filed for unemployment insurance, raising the prospect of a deep economic recession and a significant increase in the unemployment rate.3

After a delayed response, central banks are engaging in an ongoing series of interventions in financial markets and national governments are announcing spending initiatives to stimulate their economies. Similarly, international organizations are taking steps to provide loans and other financial assistance to countries in need. The Federal Reserve, in particular, has taken extraordinary steps not experienced since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis to address the growing economic effects of COVID-19, and the U.S. Congress approved a historic fiscal spending package. In other countries, central banks have lowered interest rates and reserve requirements, announced new financing facilities, and relaxed capital buffers and, in some cases, countercyclical capital buffers,4 adopted after the 2008-2009 financial crisis, potentially freeing up an estimated $5 trillion in funds.5 Capital buffers were raised after the financial crisis to assist banks in absorbing losses and staying solvent during financial crises. In some cases, governments have directed banks to freeze dividend payments and halt pay bonuses.

On March 11, the WHO announced that the outbreak was officially a pandemic, the highest level of health emergency.3 It has become clear that the outbreak is negatively impacting6 A growing list of economic indicators makes it clear that the outbreak is having a significant negative impact on global economic growth.4 7 Global trade and gross domestic product (GDP) are forecast to decline sharply at least through the first half of 2020. The global pandemic is affecting a broad swath of international economic and trade activities, from tourismservices generally to tourism and hospitality, medical supplies and other global value chains, consumer electronics, and financial markets to energy, transportation, food, and a range of social activities, to name a few. The health and economic crises could have a particularly negative impact on the economies of developing countries that are constrained by limited financial resources and where health systems could quickly become overloaded. Without a clear understanding of when the global health and economic effects may peak and some understanding of the impact on economies, forecasts must necessarily be considered preliminary. Efforts to reduce social interaction to contain the spread of the virus are disrupting the daily lives of most Americans and adding to the economic costs.

Economic Forecasts

Global Growth

The economic situation remains highly fluid. Uncertainty about the length and depth of the health crisis-related economic effects are fueling perceptions of risk and volatility in financial markets and corporate decision-making. In addition, uncertainties concerning the global pandemic and the effectiveness of public policies intended to curtail its spread are adding to market volatility.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on March 2, 2020, lowered its forecast of global economic growth by 0.5% for 2020 from 2.9% to 2.4%, if the economic effects of the virus peakpeaked in the first quarter of 202058 (see Table 1). If the The OECD estimated that if the economic effects of the virus do not peak in the first quarter, as now seems unlikely, the OECD estimates that the global economy could only grow by 1.5% in 2020. peaked in the first quarter, which is now apparent that it did not, global economic growth would increase by 1.5% in 2020. That forecast now seems to have been highly optimistic.

On March 23, 2020, OECD Secretary General Angel Gurria stated that:

The sheer magnitude of the current shock introduces an unprecedented complexity to economic forecasting. The OECD Interim Economic Outlook, released on March 2, 2020, made a first attempt to take stock of the likely impact of COVID-19 on global growth, but it now looks like we have already moved well beyond even the more severe scenario envisaged then…. the[T]he pandemic has also set in motion a major economic crisis that will burden our societies for years to come.6

Concerns over economic and financial risks have whipsawed financial markets as investors have searched for safe-haven investments, such as the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year security, which experienced a historic drop in yield to below 1% on March 3, 2020.7 The yield dropped again to historic levels on March 6, 2020, and March 9, 2020, as investors moved out of stocks and into Treasury securities due in part to concerns over the impact the pandemic would have on economic growth and expectations the Federal Reserve would lower short-term interest rates for a second time in March 2020.8

In overnight trading in various sessions between March 8, and March 24, U.S. stock market indices moved sharply (both higher and lower), triggering automatic circuit breakers designed to halt trading if the indices rise or fall by more than 5% when markets are closed.9 By March 19, 2020, investors were also moving out of corporate and municipal bonds, a traditional safe-haven investment, as firms and other financial institutions attempted to increase their cash holdings. Compared to previous financial market dislocations in which stock market values declined while bond prices rose, stock and bond values fell at the same time in March, 2020 as investors reportedly adopted a "sell everything" mentality to build up cash reserves.10

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the global economy was struggling to regain a broad-based recovery as a result of the lingering impact of growing trade protectionism, trade disputes among major trading partners, falling commodity and energy prices, and economic uncertainties in Europe over the impact of the UK withdrawal from the European Union. Individually, each of these issues presented a solvable challenge for the global economy. Collectively, however, the issues weakened the global economy and reduced the available policy flexibility of many national leaders, especially among the leading developed economies. In this environment, COVID-19 could have an outsized impact. While the level of economic effects will eventually become clearer, the response to the pandemic could have a significant and enduring impact on the way businesses organize their work forces, global supply chains, and how governments respond to a global health crisis.10

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|||

|

November |

Difference |

November |

Difference |

||

|

World |

2.9 |

2.4 |

-0.5 |

3.3 |

0.3 |

|

G20 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

-0.5 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

|

Australia |

1.7 |

1.8 |

-0.5 |

2.6 |

0.3 |

|

Canada |

1.6 |

1.3 |

-0.3 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

|

Euro area |

1.2 |

0.8 |

-0.3 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

|

Germany |

0.6 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

|

France |

1.3 |

0.9 |

-0.3 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

|

Italy |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

|

Japan |

0.7 |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

|

Korea |

2.0 |

2.0 |

-0.3 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

|

Mexico |

-0.1 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

|

Turkey |

0.9 |

2.7 |

-0.3 |

3.3 |

0.1 |

|

United Kingdom |

1.4 |

0.8 |

-0.2 |

0.8 |

-0.4 |

|

United States |

2.3 |

1.9 |

-0.1 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

|

Argentina |

-2.7 |

-2.0 |

-0.3 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

|

Brazil |

1.1 |

1.7 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

0.0 |

|

China |

6.1 |

4.9 |

-0.8 |

6.4 |

0.9 |

|

India |

4.9 |

5.1 |

-1.1 |

5.6 |

-0.8 |

|

Indonesia |

5.0 |

4.8 |

-0.2 |

5.1 |

0.0 |

|

Russia |

1.0 |

1.2 |

-0.4 |

1.3 |

-0.1 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.0 |

1.9 |

0.5 |

|

South Africa |

0.3 |

0.6 |

-0.6 |

1.0 |

-0.3 |

Source: OECD Interim Economic Assessment: CoronavirusCOVID-19: The World Economy at Risk, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. March 2, 2020, p. 2.

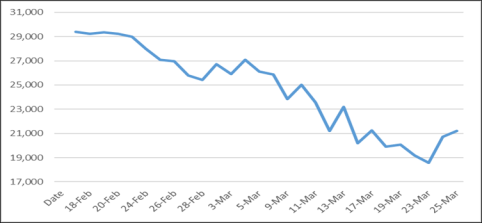

Financial markets from the United States to Asia and Europe are volatile as investors are concerned that the virus is creating a global economic and financial crisis with few metrics to indicate how prolonged and expansive the economic effects may be.11 Between February 14, 2020 and March 23, 2020, for instance, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) lost about one-third of its value, as indicated in Figure 1. Expectations that the U.S. Congress would adopt a $2.0 trillion spending package moved the DJIA up by more than 11% on March 24, 2020. For some policymakers, the drop in equity prices has raised concerns that foreign investors might attempt to exploit the situation by increasing their purchases of firms in sectors considered important to national security. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, urged EU members to better screen foreign investments, especially in areas such as health, medical research and critical infrastructure.12

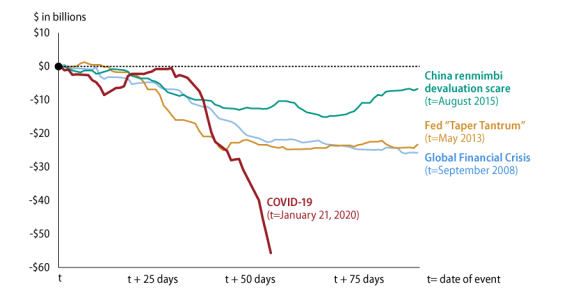

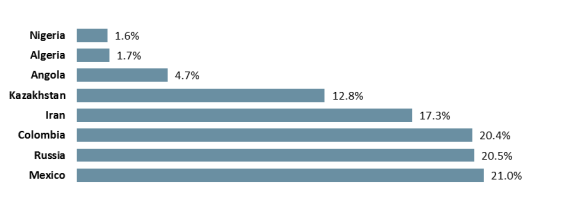

According to the OECD's updated forecast: In addition, the OECD argues that China's emergence as a global economic actor marks a significant departure from previous global health episodes. China's growth, in combination with globalization and the interconnected nature of economies through capital flows, supply chains, and foreign investment, magnify the cost of containing the spread of the virus through quarantines and restrictions on labor mobility and travel.14 China's global economic role and globalization mean that trade is playing a role in spreading the economic effects of COVID-19. More broadly, the economic effects of the pandemic are affecting the global economy through three trade channels: (1) directly through supply chains as reduced economic activity is spread from intermediate goods producers to finished goods producers; (2) as a result of a drop overall in economic activity, which reduces demand for goods in general, including imports; and (3) through reduced trade with commodity exporters that supply producers, which, in turn, reduces their imports and negatively affects trade and economic activity of exporters. Annual percent change Historical Optimistic scenario Pessimistic scenario 2018 2019 2020 2021 2020 2021 Volume of world merchandise trade 2.9 -0.1 -12.9 21.3 -31.9 24.0 Exports North America 3.8 1.0 -17.1 23.7 -40.9 19.3 South and Central America 0.1 -2.2 -12.9 18.6 -31.3 14.3 Europe 2.0 0.1 -12.2 20.5 -32.8 22.7 Asia 3.7 0.9 -13.5 24.9 -36.2 36.1 Other regions 0.7 -2.9 -8.0 8.6 -8.0 9.3 Imports North America 5.2 -0.4 -14.5 27.3 -33.8 29.5 South and Central America 5.3 -2.1 -22.2 23.2 -43.8 19.5 Europe 1.5 0.5 -10.3 19.9 -28.9 24.5 Asia 4.9 -0.6 -11.8 23.1 -31.5 25.1 Other regions 0.3 1.5 -10 13.6 -22.6 18.0 Real GDP at market exchange rates 2.9 2.3 -2.5 7.4 -8.8 5.9 North America 2.8 2.2 -3.3 7.2 -9.0 5.1 South and Central America 0.6 0.1 -4.3 6.5 -11 4.8 Europe 2.1 1.3 -3.5 6.6 -10.8 5.4 Asia 4.2 3.9 -0.7 8.7 -7.1 7.4 Other regions 2.1 1.7 -1.5 6.0 -6.7 5.2 Source: Trade Set to Plunge as COVID-19 Pandemic Upends Global Economy, World Trade Organization, April 8, 2020. Notes: Data for 2020 and 2021 are projections; projections for GDP are based on scenarios simulated with the WTO Global Trade Model. The forecast estimates indicate that all geographic regions will experience a double-digit drop in trade volumes, except for "other regions," which consists of Africa, the Middle East, and the Commonwealth of Independent States. North America and Asia could experience the steepest declines in export volumes. The forecast also projects that sectors with extensive value chains, such as automobile products and electronics, could experience the steepest declines. Although services are not included in the WTO forecast, this segment of the economy could experience the largest disruption as a consequence of restrictions on travel and transport and the closure of retail and hospitality establishments. Such services as information technology, however, are growing to satisfy the demand of employees who are working from home. The challenge for policymakers has been one of implementing targeted policies that address what has been expected to be short-term problems without creating distortions in economies that can outlast the impact of the virus itself. Policymakers, however, are being overwhelmed by the quickly changing nature of the global health crisis that appears to be turning into a global trade and economic crisis whose potential effects on the global economy are rapidly growing. If the economic effects of the pandemic continue to grow, policymakers are likely to give more weight to policies that address the immediate economic effects at the expense of longer-term considerations. Initially, many policymakers had felt constrained in their ability to respond to the crisis as a result of limited flexibility for monetary and fiscal support within conventional standards, given the broad-based synchronized slowdown in global economic growth, especially in manufacturing and trade that had developed prior to the viral outbreak. Initially, the economic effects of the virus were expected to be short-term supply issues as factory output fell because workers were quarantined to reduce the spread of the virus through social interaction. The drop in economic activity, initially in China, has had international repercussions as firms experienced delays in supplies of intermediate and finished goods through supply chains. Concerns have grown, however, that the virus-related supply shock is creating more prolonged and wide-ranging demand shocks as reduced activity by consumers and businesses lead to a lower rate of economic growth. As demand shocks unfold, businesses experience a decline in activity, reduced profits, and potentially escalating and binding credit and liquidity constraints. While manufacturing firms are experiencing supply chain shocks, reduced consumer activity through social distancing is affecting the services sector of the economy, which accounts for two-thirds of annual U.S. economic output. In this environment, manufacturing and service firms are hoarding cash, which affects market liquidity. In response, central banks have lowered interest rates where possible and expanded lending facilities to provide liquidity to financial markets and to firms potentially facing insolvency. If the economic effects persist, they can be spread through trade and financial linkages to an ever-broadening group of countries, firms and households. This potentially can further increase liquidity constraints and credit market tightening in global financial markets as firms hoard cash, with negative fallout effects on economic growth. At the same time, financial markets have been factoring in an increase in government bond issuance in the United States and Europe as government debt levels are set to rise to meet spending obligations during an expected economic recession and increased fiscal spending to fight the effects of COVID-19. Unlike the 2008-2009 financial crisis, reduced demand by consumers, labor market issues, and a reduced level of activity among businesses, rather than risky trading by global banks, has led to corporate credit issues and potential insolvency. These market dynamics have led some observers to question if these events mark the beginning of a full-scale global financial crisis.16 Liquidity and credit market issues present policymakers with a different set of challenges than addressing supply-side constraints. As a result, the focus of government policy has expanded from a health crisis to macroeconomic and financial market issues that are being addressed through a combination of monetary, fiscal, and other policies, including border closures, quarantines, and restrictions on social interactions. Essentially, while businesses are attempting to address worker and output issues at the firm level, national leaders are attempting to implement fiscal policies to prevent economic growth from falling sharply by assisting workers and businesses that are facing financial strains, and central bankers are adjusting monetary policies to address mounting credit market issues. In the initial stages of the health crisis, households did not experience the same kind of wealth losses they saw during the 2008-2009 financial crisis when the value of their primary residence dropped sharply. However, with unemployment numbers rising rapidly, job losses could result in defaults on mortgages and delinquencies on rent payments, unless financial institutions provide loan forbearance or there is a mechanism to provide financial assistance. In turn, mortgage defaults could negatively affect the market for mortgage-backed securities, the availability of funds for mortgages, and negatively affect the overall rate of economic growth. Losses in the value of most equity markets in the U.S. Asia, and Europe could also affect household wealth, especially retirees living on a fixed income and others who own equities. Investors that trade in mortgage-backed securities reportedly have been reducing their holdings while the Federal Reserve has been attempting to support the market.17 In the current environment, even traditional policy tools, such as monetary accommodation, apparently have not been processed by markets in a traditional manner, with equity market indices displaying heightened, rather than lower, levels of uncertainty following the Federal Reserve's cut in interest rates. Such volatility is adding to uncertainties about what governments can do to address weaknesses in the global economy. Between late February and early April, 2020, financial markets from the United States to Asia and Europe have been whipsawed as investors have grown concerned that COVID-19 would create a global economic and financial crisis with few metrics to indicate how prolonged and extensive the economic effects may be.18 Investors have searched for safe-haven investments, such as the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year security, which experienced a historic drop in yield to below 1% on March 3, 2020.19 In response to concerns that the global economy was in a freefall, the Federal Reserve lowered key interest rates on March 3, 2020, to shore up economic activity, while the Bank of Japan engaged in asset purchases to provide short-term liquidity to Japanese banks; Japan's government indicated it would also assist workers with wage subsidies. The Bank of Canada also lowered its key interest rate. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced that it was making about $50 billion available through emergency financing facilities for low-income and emerging market countries and funds available through its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT).20Similar to the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, central banks are implementingThe OECD estimates that increased direct and indirect economic costs through global supply chains reduced demand for goods and services, and declines in tourism and business travel mean that, "the adverse consequences of these developments for other countries (non-OECD) are significant."11 Global trade, measured by trade volumes, slowed in the last quarter of 2019 and was expected to decline further in 2020, as a result of weaker global economic activity associated with the pandemic, which is negatively affecting economic activity in various sectors, including airlines, hospitality, ports, and the shipping industry.12

|

Figure 1. Dow Jones Industrial Average February 14, 2020 to |

|

|

Source: Financial Times. |

Source: Financial Times.

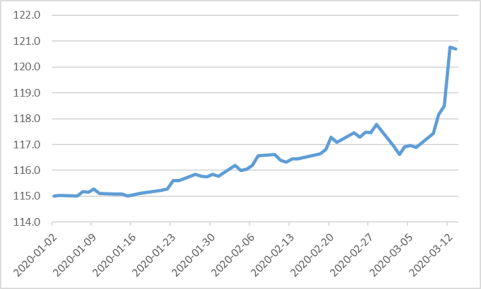

Similar to conditions during the 20072008-2009 financial crisis, however, the dollar has emerged as the preferred currency by investors, givenreinforcing its role as the dominant global reserve currency. As indicated in Figure 2, the dollar appreciated more than 3.0% during the period between March 3, and March 13, 2020, reflecting increased international demand for the dollar and dollar-denominated assets. According to a recent survey by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS),1322 the dollar accounts for 88% of global foreign exchange market turnover and is key in funding an array of financial transactions, including serving as an invoicing currency facilitatingto facilitate international trade, accounting. It also accounts for two-thirds of central bank foreign exchange holdings, half of non-U.S. banks foreign currency deposits, and two-thirds of non-U.S. corporate borrowings from banks and the corporate bond market.1423 As a result, disruptions in the smooth functioning of the global dollar market can have wide-ranging repercussions on international trade and financial transactions.

The international role of the dollar also increases pressure on the Federal Reserve essentially to assume the lead role as the global lender of last resort. Similar to conditions during the 2007-2009Reminiscent of the financial crisis, the global economy has experienced a period of dollar shortage, requiring the Federal Reserve to take numerous steps to ensure the supply of dollars to the U.S. and global economies. , including activating existing currency swap arrangements, establishing such arrangements with additional central banks, and creating new financial facilities to provide liquidity to central banks and monetary authorities.24 Typically, banks lend long-term and borrow short-term and can only borrow from their home central bank. In turn, central banks can only provide liquidity in their own currency. Consequently, a bank can become illiquid in a panic, meaning it cannot borrow in private markets to meet short-term cash flow needs. Swap lines are designed to allow foreign central banks the funds necessary to provide needed liquidity to their country's banks in dollars. The pandemic is also affecting global politics as world leaders are cancelling international meetings1525 and some nations reportedly are stoking conspiracy theories that shift blame to other countries.1626

|

Figure 2. U.S. Dollar Trade-Weighted Broad Index, Goods and Services |

|

|

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank. Notes: January 2006 = 100. |

The challenge for policymakers is to implement targeted policies that address what has been expected to be short-term problems without creating distortions in economies that can outlast the impact of the virus itself. Policymakers, however, are being overwhelmed by the quickly changing nature of the global health crisis that appears to be turning into a global trade and economic crisis whose potential effects on the global economy are rapidly growing. If the economic effects of the pandemic continue to grow, policymakers are likely to give more weight to policies that address the immediate economic effects at the expense of longer-term considerations. Initially, many policymakers felt constrained in their ability to respond to the crisis, with limited flexibility for monetary and fiscal support within conventional standards, given the broad-based synchronized slowdown in global economic growth, especially in manufacturing and trade, which had developed prior to the viral outbreak.

|

Comparing the Current Crisis and the 2008 Crisis Sharp declines in the stock market and broader financial sector turbulence; interest rate cuts and large-scale Federal Reserve intervention; and discussions of massive government stimulus packages have led some observers to compare the current market reaction to that experienced a little over a decade ago. There are similarities and important differences between the current economic crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Foremost, the earlier crisis was rooted in structural weakness in the U.S. financial sector. Following the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble, it became impossible for firms to identify demand and hold inventories (across many sectors (construction, retail, etc.). This led to massive oversupply and sharp retail losses which extended to other sectors of the U.S. economy and eventually the global economy. Moreover, financial markets across countries were linked together by credit default swaps. As the crisis unfolded, large numbers of banks and other financial institutions were negatively affected, raising questions about capital sufficiency and reserves. The crisis, then quickly engulfed credit-rating agencies, mortgage lending companies and the real estate industry broadly. Market resolution came gradually with a range of monetary and fiscal policy measures that were closely coordinated at the global level. These were focused on putting a floor under the falling markets, stabilizing banks, and shoring up investor confidence to get spending started again. Starting in September 2007, The Federal Reserve cut interest rates from over 5% in September 2007 to between 0 and 0.25% before the end of the 2008. Once interest rates approached zero, the Fed turned to other so-called "unconventional measures," including targeted assistance to financial institutions, encouraging Congress to pass the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to prevent the collapse of the financial sector and boost consumer spending. Other measures included swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank and smaller central banks, and so-called "quantitative easing" to boost the money supply. On a global level, the United States and other countries tripled the resources of the IMF (from $250 billion to $750 billion) and coordinated domestic stimulus efforts. Unlike the 2008 crisis, the current crisis began as a supply shock. As the global economy has become more interdependent in recent decades, most products are produced as part of a global value chain (GVC), where an item such as a car or mobile device consists of parts manufactured all over the world, and involving multiple border crossings before final assembly. The earliest implications of the current crisis came in January as plant closures in China and other parts of Asia led to interruptions in the supply chain and concerns about dwindling inventories. As the virus spread from Asia to Europe, the crisis switched from supply concerns to a broader demand crisis as the measures being introduced to contain the spread of the virus (social distancing, travel restrictions, cancelling sporting events, closing shops and restaurants, and mandatory quarantine measures) prevent most forms of economic activity from occurring. Thus, unlike the 2008 crisis response, which involved liquidity and solvency-related policy measures to get people spending again, the current crisis did not start as a financial crisis, but could evolve into one if a recovery in economic activity is delayed. While larger firms may have sufficient capital to wait out a crisis, many aspects of the economy (such as restaurants or retail operations) operate on very tight margins and would likely not be able to pay employees after closures lasting more than a few days. Many people will also need to balance child care and work during quarantine or social distancing measures. During this type of crisis, while monetary policy measures play a part -- and the Federal Reserve has once again cut rates to near zero -- they cannot compensate for the physical interaction that the global economy is dependent upon. As a result, fiscal stimulus will likely play a relatively larger role in this crisis in order to prevent personal and corporate bankruptcies during the peak crisis period. Efforts to coordinate U.S. and foreign economic policy measures will also have an important role in mitigating the scale and length of any global economic downtown. |

Estimated Economic Effects

The economic situation remains highly fluid. Uncertainty about the length and depth of the health crisis-related economic effects are fueling perceptions of risk and volatility in financial markets and corporate decision-making. In addition, uncertainties concerning the global pandemic and the effectiveness of public policies intended to curtail its spread are adding to market volatility.

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, the global economy was struggling to regain a broad-based recovery as a result of the lingering impact of growing trade protectionism, trade disputes among major trading partners, falling commodity and energy prices, and economic uncertainties in Europe over the impact of the UK withdrawal from the European Union. Individually, each of these issues presented a solvable challenge for the global economy. Collectively, however, the issues weakened the global economy and reduced the available policy flexibility of many national leaders, especially among the leading developed economies. In this environment, Covid-19 could have an outsized impact. While the level of economic effects will eventually become clearer, the response to the pandemic could have a significant and enduring impact on the way businesses organize their work forces, global supply chains, and how governments respond to a global health crisis.17

The OECD estimates that increased direct and indirect economic costs through global supply chains reduced demand for goods and services, and declines in tourism and business travel mean that, "the adverse consequences of these developments for other countries (non-OECD) are significant."18 Global trade, measured by trade volumes, slowed in the last quarter of 2019 and was expected to decline further in 2020, as a result of weaker global economic activity associated with the pandemic, which is negatively affecting economic activity in various sectors, including airlines, hospitality, ports, and the shipping industry.19

In addition, the OECD argues that China's emergence as a global economic actor marks a significant departure from previous global health episodes. China's growth, in combination with globalization and the interconnected nature of economies through capital flows, supply chains, and foreign investment, magnify the cost of containing the spread of the virus through quarantines and restrictions on labor mobility and travel.20 China's global economic role and globalization mean that trade is playing a role in spreading the economic effects of Covid-19. More broadly, the economic effects of the pandemic are affecting the global economy through three trade channels: (1) directly through supply chains as reduced economic activity is spread from intermediate goods producers to finished goods producers; (2) as a result of a drop overall in economic activity, which reduces demand for goods in general, including imports; and (3) through reduced trade with commodity exporters that supply producers, which, in turn, reduces their imports and negatively affects trade and economic activity of exporters.

Initially, the economic effects of the virus were expected to be short-term supply issues as factory output fell because workers were quarantined to reduce the spread of the virus through social interaction. The drop in economic activity, initially in China, has had international repercussions as firms experienced delays in supplies of intermediate and finished goods through supply chains. Concerns have grown, however, that the virus-related supply shock is creating more prolonged and wide-ranging demand shocks as reduced activity by consumers and businesses lead to a lower rate of economic growth. As demand shocks unfold, businesses experience a decline in activity, reduced profits, and potentially escalating and binding credit and liquidity constraints. While manufacturing firms are experiencing supply chain shocks, reduced consumer activity through social distancing is affecting the services sector of the economy, which accounts for two-thirds of annual U.S. economic output. In this environment, manufacturing and service firms are hoarding cash, which affects market liquidity. In response, central banks have lowered interest rates where possible and expanded lending facilities to provide liquidity to financial markets and to firms potentially facing insolvency.

If the economic effects persist, they can be spread through trade and financial linkages to an ever-broadening group of countries, firms and households. This potentially can further increase liquidity constraints and credit market tightening in global financial markets as firms hoard cash, with negative fallout effects on economic growth. In some financial markets, fund managers reportedly are selling government securities to increase their cash reserves. At the same time, financial markets are factoring in an increase in government bond issuance in the United States and Europe as government debt levels are set to rise to meet spending obligations during an expected economic recession and increased fiscal spending to fight the effects of Covid-19. Unlike the 2008-2009 financial crisis, reduced demand by consumers, labor market issues, and a reduced level of activity among businesses, rather than risky trading by global banks, has led to corporate credit issues and potential insolvency. These market dynamics have led some observers to question if these events mark the beginning of a full-scale global financial crisis.21

Liquidity and credit market issues present policymakers with a different set of challenges than addressing supply-side constraints. As a result, the focus of government policy has expanded from a health crisis to macroeconomic and financial market issues that are being addressed through a combination of monetary, fiscal, and other policies, including border closures, quarantines, and restrictions on social interactions. Essentially, while businesses are attempting to address worker and output issues at the firm level, national leaders are attempting to implement fiscal policies to prevent economic growth from falling sharply by assisting workers and businesses that are facing financial strains, and central bankers are adjusting monetary policies to address mounting credit market issues.

So far, households have not experienced the same kind of loss in wealth they saw during the 2007-2009 financial crisis when the value of their primary residence dropped sharply. Losses in the value of most equity markets in the U.S. Asia, and Europe, however, could affect household wealth, especially retirees living on a fixed income those and others who own equities. Job losses also could result in defaults on mortgage payments, which could have a negative impact on the market for mortgage-backed securities and, in turn, on the availability of funds for mortgages. Investors that trade in mortgage-backed securities reportedly have been reducing their holdings while the Federal Reserve has been attempting to support the market.22 In the current environment, even traditional policy tools, such as monetary accommodation, apparently are not being processed by markets in a traditional manner, with equity market indices displaying heightened, rather than lower, levels of uncertainty following the Federal Reserve's cut in interest rates. Such volatility is adding to uncertainties about what governments can do to address weaknesses in the global economy.

Policy Response

In response to growing concerns over the global economic impact of the pandemic, G-7 finance ministers and central bankers released a statement on March 3, 2020, indicating they will "use all appropriate policy tools" to sustain economic growth.23 The Finance Ministers also pledged fiscal support to ensure health systems can sustain efforts to fight the outbreak.24 In most cases, however, countries have pursued their own divergent strategies, in some cases including banning exports of medical equipment. Following the G-7 statement, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered its federal funds rate by 50 basis points, or 0.5%, to a range of 1.0% to 1.25% due to concerns about the "evolving risks to economic activity of the coronavirus."25 At the time, the cut was the largest one-time reduction in the interest rate by the Fed since the financial crisis of 2008.

After a delayed response, other central banks have begun to follow the actions of the G-7 countries. Most central banks have lowered interest rates and acted to increase liquidity in their financial systems through a combination of measures, including lowering capital buffers and reserve requirements, creating temporary lending facilities for banks and businesses, and easing loan terms. In addition, national governments have adopted various fiscal measures to sustain economic activity. In general, these measures include making payments directly to households, temporarily deferring tax payments, extending unemployment insurance, and increasing guarantees and loans to businesses.

See the Appendix to this report for detailed information about the policy actions by governments.26

The United States

In a sign of growing concern over strains in financial markets and economic growth, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has taken a number of steps to promote economic and financial stability involving the Fed's monetary policy and "lender of last resort" roles. Some of these actions are intended to stimulate economic activity by reducing interest rates and others are intended to provide liquidity to financial markets so that firms have access to needed funding. In announcing its decisions, the Fed indicated that "….The coronavirus outbreak has harmed communities and disrupted economic activity in many countries, including the United States. Global financial conditions have also been significantly affected.27"

Monetary Policy 28

yield on U.S. Treasury securities dropped to historic levels on March 6, 2020, and March 9, 2020, as investors continued to move out of stocks and into Treasury securities and other sovereign bonds, including UK and German bonds, due in part to concerns over the impact the pandemic would have on economic growth and expectations the Federal Reserve and other central banks would lower short-term interest rates.27 On March 5, the U.S. Congress passed an $8 billion spending bill to provide assistance for health care, sick leave, small business loans, and international assistance. At the same time, commodity prices dropped sharply as a result of reduced economic activity and disagreements among oil producers over production cuts in crude oil and lower global demand for commodities, including crude oil.

The drop in some commodity prices has raised concerns about corporate profits and has led some investors to sell equities and buy sovereign bonds. In overnight trading in various sessions between March 8, and March 24, U.S. stock market indexes moved sharply (both higher and lower), triggering automatic circuit breakers designed to halt trading if the indexes rise or fall by more than 5% when markets are closed and 7% when markets are open.28 By early April, the global mining industry had reduced production by an estimated 20% in response to falling demand and labor quarantines and as a strategy to raise prices.29

Ahead of a March 12, 2020, scheduled meeting of the European Central Bank (ECB), the German central bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) announced a package of measures to provide liquidity support to German businesses and financial support for public infrastructure projects.30 At the same time, the Fed announced that it was expanding its repo market transactions (in the repurchase market, investors borrow cash for short periods in exchange for high-quality collateral like Treasury securities) after stock market indexes fell sharply, government bond yields fell to record lows (reflecting increased demand), and demand for corporate bonds fell. Together these developments raised concerns for some analysts that instability in stock markets could threaten global financial conditions.31

On March 11, as the WHO designated COVID-19 a pandemic, governments and central banks adopted additional monetary and fiscal policies to address the growing economic impact. European Central Bank (ECB) President-designate Christine Lagarde in a conference call to EU leaders warned that without coordinated action, Europe could face a recession similar to the 2008-2009 financial crisis.32 The Bank of England lowered its key interest rate, reduced capital buffers for UK banks, and provided a funding program for small and medium businesses. The UK Chancellor of the Exchequer also proposed a budget that would appropriate £30 billion (about $35 billion) for fiscal stimulus spending, including funds for sick pay for workers, guarantees for loans to small businesses, and cuts in business taxes. The European Commission announced a €25 billion (about $28 billion) investment fund to assist EU countries and the Federal Reserve announced that it would expand its repo market purchases to provide larger and longer-term funding to provide added liquidity to financial markets.

President Trump imposed restrictions on travel from Europe to the United States on March 12, 2020, surprising European leaders and adding to financial market volatility.33 At its March 12 meeting, the ECB announced €27 billion (about $30 billion) in stimulus funding, combining measures to expand low-cost loans to Eurozone banks and small and medium-sized businesses and implement an asset purchase program to provide liquidity to firms. Germany indicated that it would provide tax breaks for businesses and "unlimited" loans to affected businesses. The ECB's Largarde roiled markets by stating that it was not the ECB's job to "close the spread" between Italian and German government bond yields (a key risk indicator for Italy), a comment reportedly interpreted as an indicator the ECB was preparing to abandon its support for Italy, a notion that was denied by the ECB.34 The Fed also announced that it would further increase its lending in the repo market and its purchases of Treasury securities to provide liquidity. As a result of tight market conditions for corporate bonds, firms turned to their revolving lines of credit with banks to build up their cash reserves. The price of bank shares fell, reflecting sales by investors who reportedly had grown concerned that banks would experience a rise in loan defaults.35 Despite the various actions, the DJIA fell by nearly 10% on March 12, recording the worst one-day drop since 1987. Between February 14 and March 12, the DJIA fell by more than 8,000 points, or 28% of its value. Credit rating agencies began reassessing corporate credit risk, including the risk of firms that had been considered stable.36

On March 13, President Trump declared a national emergency, potentially releasing $50 billion in disaster relief funds to state and local governments. The announcement moved financial markets sharply higher, with the DJIA rising 10%.37 Financial markets also reportedly moved higher on expectations the Fed would lower interest rates. House Democrats and President Trump agreed to a $2 trillion spending package to provide sick leave, unemployment insurance, food stamps, support for small businesses, and other measures.38 The EU indicated that it would relax budget rules that restrict deficit spending by EU members. In other actions, the People's Bank of China cut its reserve requirements for Chinese banks, potentially easing borrowing costs for firms and adding $79 billion in funds to stimulate the Chinese economy; Norway's central bank reduced its key interest rate; the Bank of Japan acquired billions of dollars of government securities (thereby increasing liquidity); and the Reserve Bank of Australia injected nearly $6 billion into its financial system.39 The Bank of Canada also lowered its overnight lending rate.

The Federal Reserve lowered its key interest rate to near zero on March 15, 2020, arguing that the pandemic had "harmed communities and disrupted economic activity in many countries, including the United States" and that it was prepared to use its "full range of tools."40 It also announced an additional $700 billion in asset purchases, including Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities, expanded repurchase operations, activated dollar swap lines with Canada, Japan, Europe, the UK, and Switzerland, opened its discount window to commercial banks to ease household and business lending, and urged banks to use their capital and liquidity buffers to support lending.41

Despite the Fed's actions the previous day to lower interest rates, interest rates in the U.S. commercial paper market, where corporations raise cash by selling short-term debt, rose on March 16, 2020, to their highest levels since the 2008-2009 financial crisis as investors called on the Federal Reserve to intervene.42 The DJIA dropped nearly 3,000 points, or about 13%. Most automobile manufacturers announced major declines in sales and production;43 similarly, most airlines reported they faced major cutbacks in flights and employee layoffs due to diminished economic activity.44 Economic data from China indicated the economy would slow markedly in the first quarter of 2020, potentially greater than that experienced during the global financial crisis.45 The Bank of Japan announced that it would double its purchases of exchange traded funds. The G-7 countries46 issued a joint statement promising "a strongly coordinated international approach," although no specific actions were mentioned. The IMF issued a statement indicating its support for additional fiscal and monetary actions by governments and that the IMF "stands ready to mobilize its $1 trillion lending capacity to help its membership." The World Bank also promised an additional $14 billion to assist governments and companies address the pandemic.47

Following the drop in equity market indexes the previous day, the Federal Reserve unveiled a number of facilities on March 17, 2020, in some cases reviving actions it had not taken since the financial crisis. It announced that it would allow the 24 primary dealers in Treasury securities to borrow cash collateralized against some stocks, municipal debt, and higher-rated corporate bonds; revive a facility to buy commercial paper; and provide additional funding for the overnight repo market.48 The UK government proposed government-backed loans to support business; a three-month moratorium on mortgage payments for homeowners; a new lending facility with the Bank of England to provide low-cost commercial paper to support lending; and loans for businesses.

In an emergency session on March 18, the ECB announced a Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program to acquire an additional €750 billion (over $820 billion) in bond purchases.49 The ECB also broadened the types of assets it would accept as collateral for non-financial commercial paper and eased collateral standards for banks.50 The Federal Reserve broadened its central bank dollar swap lines to include Brazil, Mexico, Australia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Automobile manufacturers announced they were suspending production at an estimated 100 plants across North America, following similar plant closures in Europe.51 Major U.S. banks announced a moratorium on share repurchases, or stock buy-backs, denying equity markets a major source of support and potentially amplifying market volatility.52 During the week, more than 22 central banks in emerging economies, including Brazil, Turkey, and Vietnam, lowered their key interest rates.

By March 19, 2020, investors had begun selling sovereign and other bonds as firms and other financial institutions attempted to increase their cash holdings, although actions central banks took during the week appeared to calm financial markets. Compared to previous financial market dislocations in which stock market values declined while bond prices rose, stock and bond values fell at the same time in March 2020 as investors reportedly adopted a "sell everything" mentality to build up cash reserves.53 Senate Republicans introduced the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act to provide $1 trillion in spending to support the U.S. economy.

By the close of trading on March 20, the DJIA index had fallen by 17% from March 13. At the same time, the dollar continued to gain in value against other major currencies and the price of oil dropped close to $20 per barrel on March 20, as indicated in Figure 3. The Federal Reserve announced that it would expand a facility to support the municipal bond market. Britain's Finance Minister announced an "unprecedented" fiscal package to pay up to 80% of an employee's wages and deferring value added taxes by businesses.54 The ECB's Largarde justified actions by the Bank during the week to provide liquidity by arguing that the "coronavirus pandemic is a public health emergency unprecedented in recent history." Market indexes fell again on March 23 as the Senate continued to debate the parameters of a new spending bill to support the economy. Oil prices also continued to fall as oil producers appeared to be in a standoff over cuts to production.Figure 3. Brent Crude Oil Price Per Barrel in Dollars Source: Markets Insider.

Financial markets continued to fall on March 23, 2020, as market indexes reached their lowest point since the start of the pandemic crisis. The Federal Reserve announced a number of new facilities to provide an unlimited expansion in bond buying programs. The measures include additional purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities; additional funding for employers, consumers, and businesses; establishing the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) to support issuing new bonds and loans and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) to provide liquidity for outstanding corporate bonds; establishing the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), to support credit to consumers and businesses; expanding the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF) to provide credit to municipalities; and expanding the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) to facilitate the flow of credit to municipalities.55 The OECD released a statement encouraging its members to support "immediate, large-scale and coordinated actions." These actions include (1) more international cooperation to address the health crisis; (2) coordinated government actions to increase spending to support health care, individuals, and firms; (3) coordinated central bank action to supervise and regulate financial markets; (4) and policies directed at restoring confidence.56

Reacting to the Fed's actions, the DJIA closed up 11% on March 24, marking one of the sharpest reversals in the market index since February 2020. European markets, however, did not follow U.S. market indexes as various indicators signaled a decline in business activity in the Eurozone that was greater than that during the financial crisis and indicated the growing potential for a deep economic recession.57 U.S. financial markets were buoyed on March 25 and 26 over passage in the Congress of a $2.2 trillion economic stimulus package.

On March 27, leaders of the G-20 countries announced through a video conference they had agreed to inject $5 trillion into the global economy and to do "whatever it takes to overcome the pandemic." Also at the meeting, the OECD offered an updated forecast of the viral infection, which projected that the global economy could shrink by as much as 2% a month. Nine Eurozone countries, including France, Italy, and Spain called on the ECB to consider issuing "coronabonds," a common European debt instrument to assist Eurozone countries fight against COVID-19.58 The ECB announced that it was removing self-imposed limits followed in previous asset purchase programs that restricted its purchases of any one country's bonds.59 Japan announced that it would adopt an emergency sending package worth $238 billion, or equivalent to 10% of Japan annual GDP.60 Despite the various actions, global financial markets turned down March 27 (the DJIA dropped by 900 points) reportedly over volatility in oil markets and concerns that the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were worsening.61

By March 30, central banks in developing countries from Poland, Columbia, South Africa, the Philippines, Brazil, and the Czech Republic reportedly began adopting monetary policies similar to that of the Federal Reserve to stimulate their economies.62 In commodity markets, Brent oil prices continued to fall, reaching a low of $22.76. Strong global demand for dollars continued to put upward pressure on the international value of the dollar. In response, the Federal Reserve introduced a new temporary facility that would work with its swap lines to allow central banks and international monetary authorities to enter into repurchase agreements with the Fed.63 In March and early April, U.S. workers' claims for unemployment benefits reached over 17 million as firms facing a collapse in demand and requirements for employees to self-quarantine began furloughing or laying off employees. Financial markets began to recover somewhat in early April in response to the accumulated monetary and fiscal policy initiatives, but remained volatile as a result of uncertainty over efforts to reach an output agreement among oil producers and the continued impact of the viral health effects.

The Federal Reserve announced on April 8 that it was establishing a facility to fund small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program. Japan also announced that it was preparing to declare areas around Tokyo to be in a state of emergency and that it would adopt a $989 billion funding package.64

On April 9, OPEC and Russia reportedly agreed to cut oil production by 10 million barrels per day; G-20 ministers were set to discuss the agreement on April 10.65 Eurozone finance ministers also announced a €500 billion (about $550 billion) emergency spending package to support governments, businesses, and workers. The spending measure will be considered by EU leaders the following week. Reportedly, the measure will provide funds to the European Stability Mechanism, the European Investment Bank, and for unemployment insurance.66 The IMF announced that it was doubling its emergency lending capability to $100 billion, in response to requests from more than 90 countries for assistance.67 The Bank of England announced that it would take the unprecedented move of temporarily directly financing UK government emergency spending needs through monetary measures rather than through the typical method of issuing securities to fight the effects of COVID-19.68

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, stating that the U.S. economy was deteriorating "with alarming speed," announced that the Fed would provide an additional $2.3 trillion in loans, including a new financial facility to assist firms by acquiring shares in exchange traded funds that own the debt of lower-rated, riskier firms that are among the most exposed to deteriorating economic conditions associated with COVID-19 and low oil prices.69 The U.S. Labor Department reported that 6.6 million Americans filed for unemployment insurance the previous week, raising the total since mid-March to over 17 million.70

|

Comparing the Current Crisis and the 2008 Crisis Sharp declines in the stock market and broader financial sector turbulence; interest rate cuts and large-scale Federal Reserve intervention; and discussions of massive government stimulus packages have led some observers to compare the current market reaction to that experienced a little over a decade ago. There are similarities and important differences between the current economic crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Foremost, the earlier crisis was rooted in structural weakness in the U.S. financial sector. Following the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble, it became impossible for firms to identify demand and hold inventories across many sectors (construction, retail, etc.). This led to massive oversupply and sharp retail losses which extended to other sectors of the U.S. economy and eventually the global economy. Moreover, financial markets across countries were linked together by credit default swaps. As the crisis unfolded, large numbers of banks and other financial institutions were negatively affected, raising questions about capital sufficiency and reserves. The crisis then quickly engulfed credit-rating agencies, mortgage lending companies, and the real estate industry broadly. Market resolution came gradually with a range of monetary and fiscal policy measures that were closely coordinated at the global level. These were focused on putting a floor under the falling markets, stabilizing banks, and shoring up investor confidence to get spending started again. Starting in September 2007, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates from over 5% in September 2007 to between 0 and 0.25% before the end of the 2008. Once interest rates approached zero, the Fed turned to other so-called "unconventional measures," including targeted assistance to financial institutions, encouraging Congress to pass the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to prevent the collapse of the financial sector and boost consumer spending. Other measures included swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank and smaller central banks, and so-called "quantitative easing" to boost the money supply. On a global level, the United States and other countries tripled the resources of the IMF (from $250 billion to $750 billion) and coordinated domestic stimulus efforts. Unlike the 2008 crisis, the current crisis began as a supply shock. As the global economy has become more interdependent in recent decades, most products are produced as part of a global value chain (GVC), where an item such as a car or mobile device consists of parts manufactured all over the world, and involving multiple border crossings before final assembly. The earliest implications of the current crisis came in January as plant closures in China and other parts of Asia led to interruptions in the supply chain and concerns about dwindling inventories. As the virus spread from Asia to Europe, the crisis switched from supply concerns to a broader demand crisis as the measures being introduced to contain the spread of the virus (social distancing, travel restrictions, cancelling sporting events, closing shops and restaurants, and mandatory quarantine measures) prevent most forms of economic activity from occurring. Thus, unlike the 2008 crisis response, which involved liquidity and solvency-related policy measures to get people spending again, the current crisis did not start as a financial crisis, but could evolve into one if a recovery in economic activity is delayed. While larger firms may have sufficient capital to wait out a crisis, many aspects of the economy (such as restaurants or retail operations) operate on very tight margins and would likely not be able to pay employees after closures lasting more than a few days. Many people will also need to balance child care and work during quarantine or social distancing measures. During this type of crisis, while monetary policy measures play a part—and the Federal Reserve has once again cut rates to near zero—they cannot compensate for the physical interaction that the global economy is dependent upon. As a result, fiscal stimulus will likely play a relatively larger role in this crisis in order to prevent personal and corporate bankruptcies during the peak crisis period. Efforts to coordinate U.S. and foreign economic policy measures will also have an important role in mitigating the scale and length of any global economic downtown. |

In response to growing concerns over the global economic impact of the pandemic, G-7 finance ministers and central bankers released a statement on March 3, 2020, indicating they will "use all appropriate policy tools" to sustain economic growth.71 The Finance Ministers also pledged fiscal support to ensure health systems can sustain efforts to fight the outbreak.72 In most cases, however, countries have pursued their own divergent strategies, in some cases including banning exports of medical equipment. Following the G-7 statement, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered its federal funds rate by 50 basis points, or 0.5%, to a range of 1.0% to 1.25% due to concerns about the "evolving risks to economic activity of the COVID-19."73 At the time, the cut was the largest one-time reduction in the interest rate by the Fed since the global financial crisis.

After a delayed response, other central banks have begun to follow the actions of the G-7 countries. Most central banks have lowered interest rates and acted to increase liquidity in their financial systems through a combination of measures, including lowering capital buffers and reserve requirements, creating temporary lending facilities for banks and businesses, and easing loan terms. In addition, national governments have adopted various fiscal measures to sustain economic activity. In general, these measures include making payments directly to households, temporarily deferring tax payments, extending unemployment insurance, and increasing guarantees and loans to businesses.

See the Appendix to this report for detailed information about the policy actions by individual governments.74 The United StatesIn a sign of growing concern over strains in financial markets and economic growth, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has taken a number of steps to promote economic and financial stability involving the Fed's monetary policy and "lender of last resort" roles. Some of these actions are intended to stimulate economic activity by reducing interest rates and others are intended to provide liquidity to financial markets so that firms have access to needed funding. In announcing its decisions, the Fed indicated that "[t]he COVID-19 outbreak has harmed communities and disrupted economic activity in many countries, including the United States. Global financial conditions have also been significantly affected.75" On March 31, 2020, the Trump Administration announced that it was suspending for 90 days tariffs it had placed on imports of apparel and light trucks from China, but not on other consumer goods and metals.76

Monetary Policy77Forward Guidance

Forward guidance refers to Fed public communications on its future plans for short-term interest rates, and it took many forms following the 2008 financial crisis. As monetary policy returned to normal in recent years, forward guidance was phased out. It is being used again today. For example, when the Fed reduced short-term rates to zero on March 15, it announced that it "expects to maintain this target range until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals."

Quantitative Easing

Large-scale asset purchases, popularly referred to as quantitative easing or QE, were also used during the financial crisis. Under QE, the Fed expanded its balance sheet by purchasing securities. Three rounds of QE from 2009 to 2014 increased the Fed's securities holdings by $3.7 trillion.

On March 23, the Fed announcedannounced that it would increase its purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS)—including commercial MBS—issued by government agencies or government-sponsored enterprises to "the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy.... " These would be undertaken at the unprecedented rate of up to $125 billion daily during the week of March 23. As a result, the value of the Fed's balance sheet is projected to exceed its post-financial crisis peak of $4.5 trillion. One notable difference from previous rounds of QE is that the Fed is purchasing securities of different maturities, so the effect likely will not be concentrated on long-term rates.

Actions to Provide Liquidity

Reserve Requirements

On March 15, the Fed announced that it was reducing reserve requirements—the amount of vault cash or deposits at the Fed that banks must hold against deposits—to zero for the first time everever. As the Fed noted in its announcement, because bank reserves are currently so abundant, reserve requirements "do not play a significant role" in monetary policy.

Term Repos

The Fed can temporarily provide liquidity to financial markets by lending cash through repurchase agreements (reposrepos) with primary dealers (i.e., large government securities dealers who are market makers). Before the financial crisis, this was the Fed's routine method for targeting the federal funds rate. Following the financial crisis, the Fed's large balance sheet meant that repos were no longer needed, until they were revived in September 2019. On March 12, the Fed announcedannounced it would offer a three-month repo of $500 billion and a one-month repo of $500 billion on a weekly basis through the end of the month in addition to the shorter-term repos it had already been offering. These repos would be larger and longer than those offered since September.

Discount Window

In its March 15 announcement, the Fed encouragedDiscount Window

In its March 15 announcement, the Fed encouraged banks (insured depository institutions) to borrow from the Fed's discount window to meet their liquidity needs. This is the Fed's traditional tool in its "lender of last resort" function. The Fed also encouraged banks to use intraday credit available through the Fed's payment systems as a source of liquidity.

Foreign Central Bank Swap Lines

Both domestic and foreign commercial banks rely on short-term borrowing markets to access U.S. dollars needed to fund their operations and meet their cash flow needs. But in an environment of strained liquidity, only banks operating in the United States can access the discount window. Therefore, the Fed has standing "swap lines" with major foreign central banks to provide central banks with U.S. dollar funding that they can in turn lend to private banks in their jurisdictions. On March 15, the Fed reducedreduced the cost of using those swap lines and on March 19 it extended swap lines to nine more central banks.

Emergency Credit Facilities for the Nonbank Financial System

In 2008, the Fed created a series of emergency credit facilities to support liquidity in the nonbank financial system. This extended the Fed's traditional role as lender of last resort from the banking system to the overall financial system for the first time since the Great Depression. To create these facilities, the Fed relied on its emergency lending authority (Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act). To date, the Fed has created six facilities—some new, and some reviving 2008 facilities—in response to COVID-19.

- On March 17, the Fed

revivedrevived the commercial paper funding facility to purchase commercial paper, which is an important source of short-term funding for financial firms, nonfinancial firms, and asset-backed securities (ABS). - Like banks, primary dealers are heavily reliant on short-term lending markets in their role as securities market makers. Unlike banks, they cannot access the discount window. On March 17, the Fed

revivedrevived the primary dealer credit facility, which is akin to a discount window for primary dealers. Like the discount window, it provides short-term, fully collateralized loans to primary dealers. - On March 19, the Fed

createdcreated the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF), similar to afacilityfacility created during the 2008 financial crisis. The MMLF makes loans to financial institutions to purchase assets that money market funds are selling to meet redemptions. - On March 23, the Fed created two facilities to support corporate bond markets—the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility to purchase newly issued corporate debt and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility to purchase existing corporate debt on secondary markets.

- On March 23, the Fed revived the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility to make nonrecourse loans to private investors to purchase ABS backed by various nonmortgage consumer loans.

Many of these facilities are structured as special purpose vehicles controlled by the Fed because of restrictions on the types of securities that the Fed can purchase. Although there were no losses from these facilities during the financial crisis, assets of the Treasury's Exchange Stabilization Fund have been pledged to backstop any losses on several of the facilities today.

Fiscal Policy

In terms of a fiscal stimulus, Congress H.R. 6074 on March 5, 2020 (P.L. 116-123), to appropriate $8.3 billion in emergency funding to support efforts to fight CovidCOVID-19; President Trump signed the measure on March 6, 2020. President Trump also signed on March 18, H.R. 6201 (P.L. 116-127), the Families First CoronavirusCOVID-19 Response Act, that provides paid sick leave and free coronavirusCOVID-19 testing, expands food assistance and unemployment benefits, and requires employers to provide additional protections for health care workers. Other countries have indicated they will also provide assistance to workers and to some businesses. Congress also is considering other possible measures, including contingency plans for agencies to implement offsite telework for employees, financial assistance to the shale oil industry, a reduction in the payroll tax,2979 and extended of the tax filing deadline.3080 President Trump has taken additional actions, including:

- Announcing on March 11, 2020, restrictions on all travel from Europe to the United States for 30 days, directed the Small Business Administration (SBA) to offer low-interest loans to small businesses, and directed the Treasury Department to defer tax payments penalty-free for affected businesses.

3181 - Declaring on March 13, a state of emergency that frees up disaster relief funding to assist state and local governments to address the effects of the pandemic. The President also announced additional testing for the virus, a website to help individuals identify symptoms, increased oil purchases for the Strategic Oil Reserve, and a waiver on interest payments on student loans.

3282 - Invoking on March 18, 2020, the Defense Production Act (DPA) that gives him the authority to require some U.S. businesses to increase production of medical equipment and supplies that are in short supply.

33

83On March 19, the Senate introduced a bill, the Coronavirus25, 2020, the Senate adopted the COVID-19 Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (S. 3548), to formally considerimplement President Trump's proposal by providing direct payments to taxpayers, loans and guarantees to airlines and other industries, and assistance for small businesses, actions similar to those of various foreign governments. The bill, set to be adopted March 25, 2020, would:

ProvideHouse adopted the measure as H.R. 748 on March 27, and President Trump signed the measure (P.L. 116-136) on March 27. The law:Provides funding for $1,200 tax rebates to individuals, with additional $500 payments per qualifying child. The rebate begins phasing out when incomes exceed $75,000 (or $150,000 for joint filers).AssistAssists small businesses by providing funding for, forgivable bridge loans; and additional funding for grants and technical assistance; authorizes emergency loans to distressed businesses, including air carriers, and suspends certain aviation excise taxes.CreateCreates a $367 billion loan program for small businesses, establish a $500 billion lending fund for industries, cities and states, a $150 billion for state and local stimulus funds, and $130 billion for hospitals.IncreaseIncreases unemployment insurance benefits, expand eligibility and offer workers an additional $600 a week for four month, in addition to state unemployment programs. 84

EstablishesEstablishspecial rules for certain tax-favored withdrawals from retirement plans; delays due dates for employer payroll taxes and estimated tax payments for corporations; and revise other provisions, including those related to losses, charitable deductions, and business interest.ProvideProvides additional funding for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of COVID-19; limit liability for volunteer health care professionals; prioritize Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review of certain drugs; allow emergency use of certain diagnostic tests that are not approved by the FDA; expand health-insurance coverage for diagnostic testing and requires coverage for preventative services and vaccines; and revise other provisions, including those regarding the medical supply chain, the national stockpile, the health care workforce, the Healthy Start program, telehealth services, nutrition services, Medicare, and Medicaid.- Temporarily

suspendsuspends payments for federal student loans and revise provisions related to campus-based aid, supplemental educational-opportunity grants, federal work-study, subsidized loans, Pell grants, and foreign institutions. AuthorizeAuthorizes the Department of the Treasury temporarily to guarantee money-market funds.

For additional information about the impact of CovidCOVID-19 on the U.S. economy see CRS Insight IN11235, COVID-19: Potential Economic Effects.3485

Europe

To date, European countries have not had the kind of synchronized policy response they developed during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. Instead, they have used a combination of fiscal policies and bond buying by the ECB. Individual countries have adopted quarantines and required business closures, travel and border restrictions, tax holidays for businesses, extensions of certain payments and loan guarantees, and subsidies for workers and businesses. The economic effects of the pandemic reportedly are having a significant impact on business activity in Europe, with some indexes falling farther then they had during the height of the financial crisis and others indicating that Europe may well experience a deep economic recession in 2020.35 86 France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK reported steep drops in industrial activity in March 2020. EU countries have issued travel warnings, banning all but essential travel across borders, raising concerns that even much-needed medical supplies could stall at borders affected by traffic backups.36

The European Commission announced that it was relaxing rules on government debt to allow countries more flexibility in using fiscal policies. The European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it was ready to take "appropriate and targeted measures," if needed. France, Italy, Spain and six other Eurozone countries have argued for creating a "coronabond," a joint common European debt instrument. Similar attempts to create a common Eurozone-wide debt instrument have been opposed by Germany and the Netherland, among other Eurozone members.3789 With interest rates already low, however, it indicated that it would expand its program of providing loans to EU banks, or buying debt from EU firms, and possibly lowering its deposit rate further into negative territory in an attempt to shore up the Euro's exchange rate.3890 ECB President-designate Christine Lagarde called on EU leaders to take more urgent action to avoid the spread of CovidCOVID-19 triggering a serious economic slowdown. The European Commission indicated that it was creating a $30 billion investment fund to address CovidCOVID-19 issues.3991 In other actions:

- On March 12, 2020, the ECB decided to: (1) expand its longer-term refinance operations (LTRO) to provide low-cost loans to Eurozone banks to increase bank liquidity; (2) extend targeted longer-term refinance operations (TLTRO) to provide loans at below-market rates to businesses, especially small and medium-sized businesses, directly affected by