Coast Guard Cutter Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from March 22, 2020 to April 15, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Older Ships to Be Replaced by NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

- Missions of NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

- NSC Program

- OPC Program

- Overview

- Competition and September 2016 Contract Award

- October 2019 Announcement of Contractual Relief and Follow-on Competition

- January 10, 2020, RFP for Industry Studies

- March 20, 2020, Contract Awards for Industry Studies

- Appendices with Additional Information

- FRC Program

- Funding in FY2013-FY2021 Budget Submissions

- Issues for Congress

- Potential Impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Situation

- Procurement Funding for 12th NSC

- Number of FRCs to Procure in FY2021

- Procurement Cost

and Cost Effectiveness ofGrowth on OPCs 1 Through 4 - Contractual Relief and Follow-on Competition for OPC Program

- Overall Course of Action

- Contractual Relief

- Follow-On Competition

- Notional Schedule

- November 25, 2019, House Committee Letter Regarding OPC Program

- Risk of Procurement Cost Growth on OPCs 5-25

- Annual OPC Procurement Rate

- Annual or Multiyear (Block Buy) Contracting for OPCs

- Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

- Legislative Activity for FY2021

- Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2021 Procurement Funding Request

Figures

- Figure 1. National Security Cutter

- Figure 2. Offshore Patrol Cutter

- Figure 3. Offshore Patrol Cutter

- Figure 4. Offshore Patrol Cutter

- Figure 5. Offshore Patrol Cutter

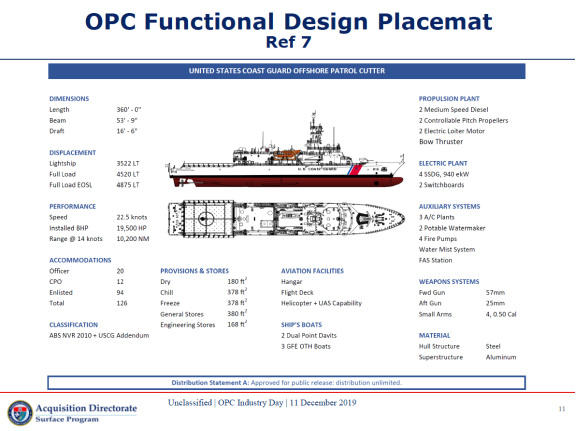

- Figure 6. OPC Functional Design

- Figure 7. Fast Response Cutter

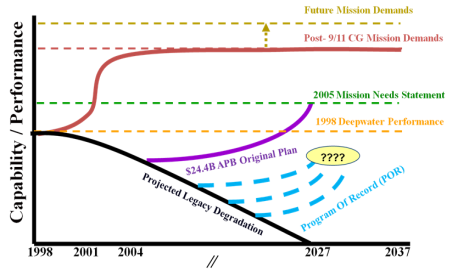

- Figure A-1. Projected Mission Demands vs. Projected Capability/Performance

Tables

- Table 1. NSC, OPC, and FRC Funding in FY2013-FY2021 Budget Submissions

- Table 2. Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2021 Procurement Funding Request

- Table A-1. Program of Record Compared to Objective Fleet Mix

- Table A-2. POR Compared to FMAs 1 Through 4

- Table A-3. Force Mixes and Mission Performance Gaps

- Table A-4. POR Compared to Objective Mixes in FMA Phases 1 and 2

- Table B-1. Funding in PC&I Account in FY2013-FY2020 Budgets

Appendixes

- Appendix A. Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

- Appendix B. Funding Levels in PC&I Account

- Appendix C. Information on NSC, OPC, and FRC Programs from GAO Report

- Appendix D. Some Considerations Relating to Warranties in Shipbuilding

- Appendix E. Impact of Hurricane Michael on OPC Program at Eastern Shipbuilding

- Appendix F. November 25, 2019, House Committee Letter Regarding OPC Program

Summary

The Coast Guard's program of record (POR) calls for procuring 8 National Security Cutters (NSCs), 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs), and 58 Fast Response Cutters (FRCs) as replacements for 90 aging Coast Guard high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and patrol craft. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests a total of $597 million in procurement funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs. It also proposes a rescission of $70 million in FY2020 procurement funding that Congress provided for the NSC program.

NSCs are the Coast Guard's largest and most capable general-purpose cutters; they are replacing the Coast Guard's 12 Hamilton-class high-endurance cutters. NSCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $670 million per ship. Although the Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 8 NSCs to replace the 12 Hamilton-class cutters, Congress through FY2020 has fully funded 11 NSCs, including the 10th and 11th in FY2018. In FY2020, Congress provided $100.5 million for procurement of long lead time materials (LLTM) for a 12th NSC, so as to preserve the option of procuring a 12th NSC while the Coast Guard evaluates its future needs. The funding can be used for procuring LLTM for a 12th NSC if the Coast Guard determines it is needed. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $31 million in procurement funding for activities within the NSC program; this request does not include further funding for a 12th NSC. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget also proposes a rescission of $70 million of the $100.5 million that Congress provided for a 12th NSC, with the intent of reprogramming that funding to the Coast Guard's Polar Security Cutter (PSC) program. Eight NSCs have entered service; the seventh and eighth were commissioned into service on August 24, 2019. The 9th through 11th are under construction; the 9th is scheduled for delivery in 2020.

OPCs are to be less expensive and in some respects less capable than NSCs; they are intended to replace the Coast Guard's 29 aged medium-endurance cutters. Coast Guard officials describe the OPC and PSC programs as the service's highest acquisition priorities. OPCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $411 million per ship. The first OPC was funded in FY2018. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $546 million in procurement funding for the third OPC, LLTM for the fourth, and other program costs. On October 11, 2019, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), of which the Coast Guard is a part, announced that DHS had granted extraordinary contractual relief to Eastern Shipbuilding Group (ESG) of Panama City, FL, the builder of the first four OPCs, under P.L. 85-804 as amended (50 U.S.C. 1431-1435), a law that authorizes certain federal agencies to provide certain types of extraordinary relief to contractors who are encountering difficulties in the performance of federal contracts or subcontracts relating to national defense. ESG reportedly submitted a request for extraordinary relief on June 30, 2019, after ESG's shipbuilding facilities were damaged by Hurricane Michael, which passed through the Florida panhandle on October 10, 2018. The Coast Guard intends to hold a competition for a contract to build OPCs 5 through 15.

FRCs are considerably smaller and less expensive than OPCs; they are intended to replace the Coast Guard's 49 aging Island-class patrol boats. FRCs have an estimated average procurement cost of about $65 million per boat. A total of 60 have been funded through FY2020, including four in FY2020. Four of the 60 are to be used by the Coast Guard in the Persian Gulf and are not counted against the Coast Guard's 58-ship POR for the program, which relates to domestic operations. Excluding these four FRCs, 56 FRCs for domestic operations have been funded through FY2020. The 36th FRC was commissioned into service on January 10, 2020. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $20 million in procurement funding for the FRC program; this request does not include funding for any additional FRCs.

Introduction

This report provides background information and potential oversight issues for Congress on the Coast Guard's programs for procuring 8 National Security Cutters (NSCs), 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs), and 58 Fast Response Cutters (FRCs). The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests a total of $597 million in procurement funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs.

The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Coast Guard's funding requests and acquisition strategies for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs. Congress's decisions on these three programs could substantially affect Coast Guard capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

The NSC, OPC, and FRC programs have been subjects of congressional oversight for several years, and were previously covered in other CRS reports dating back to 1998 that are now archived.1 CRS testified on the Coast Guard's cutter acquisition programs most recently in October and November of 2018.2 The Coast Guard's plans for modernizing its fleet of polar icebreakers are covered in a separate CRS report.3

Background

Older Ships to Be Replaced by NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

The 91 planned NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs are intended to replace 90 older Coast Guard ships—12 high-endurance cutters (WHECs), 29 medium-endurance cutters (WMECs), and 49 110-foot patrol craft (WPBs).4 The Coast Guard's 12 Hamilton (WHEC-715) class high-endurance cutters entered service between 1967 and 1972.5 The Coast Guard's 29 medium-endurance cutters included 13 Famous (WMEC-901) class ships that entered service between 1983 and 1991,6 14 Reliance (WMEC-615) class ships that entered service between 1964 and 1969,7 and 2 one-of-a-kind cutters that originally entered service with the Navy in 1944 and 1971 and were later transferred to the Coast Guard.8 The Coast Guard's 49 110-foot Island (WPB-1301) class patrol boats entered service between 1986 and 1992.9

Many of these 90 ships are manpower-intensive and increasingly expensive to maintain, and have features that in some cases are not optimal for performing their assigned missions. Some of them have already been removed from Coast Guard service: 8 of the Island-class patrol boats were removed from service in 2007 following an unsuccessful effort to modernize and lengthen them to 123 feet; additional Island-class patrol boats are being decommissioned as new FRCs enter service; the one-of-a-kind medium-endurance cutter that originally entered service with the Navy in 1944 was decommissioned in 2011; and Hamilton-class cutters are being decommissioned as new NSCs enter service. A July 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report discusses the generally poor physical condition and declining operational capacity of the Coast Guard's older high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and 110-foot patrol craft.10

Missions of NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs

NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, like the ships they are intended to replace, are to be multimission ships for routinely performing 7 of the Coast Guard's 11 statutory missions, including

- search and rescue (SAR);

- drug interdiction;

- migrant interdiction;

- ports, waterways, and coastal security (PWCS);

- protection of living marine resources;

- other/general law enforcement; and

- defense readiness operations.11

Smaller Coast Guard patrol craft and boats contribute to the performance of some of these seven missions close to shore. NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs perform them both close to shore and in the deepwater environment, which generally refers to waters more than 50 miles from shore.

NSC Program

National Security Cutters (Figure 1)—also known as Legend (WMSL-750)12 class cutters because they are being named for legendary Coast Guard personnel13—are the Coast Guard's largest and most capable general-purpose cutters.14 They are larger and technologically more advanced than Hamilton-class cutters, and are built by Huntington Ingalls Industries' Ingalls Shipbuilding of Pascagoula, MS (HII/Ingalls).

|

|

Source: U.S. Coast Guard photo accessed May 2, 2012, at http://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/5617034780/sizes/l/in/set-72157629650794895/. |

The Coast Guard's acquisition program of record (POR)—the service's list, established in 2004, of planned procurement quantities for various new types of ships and aircraft—calls for procuring 8 NSCs as replacements for the service's 12 Hamilton-class high-endurance cutters. The Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of a nine-ship NSC program at $6.030 billion, or an average of about $670 million per ship.15

Although the Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 8 NSCs to replace the 12 Hamilton-class cutters, Congress through FY2020 has fully funded 11 NSCs, including the 10th and 11th in FY2018. In FY2020, Congress provided $100.5 million for procurement of long lead time materials (LLTM) for a 12th NSC, so as to preserve the option of procuring a 12th NSC while the Coast Guard evaluates its future needs. The funding can be used for procuring LLTM for a 12th NSC if the Coast Guard determines it is needed. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $31 million in procurement funding for activities within the NSC program; this request does not include further funding for a 12th NSC. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget also proposes a rescission of $70 million of the $100.5 million that Congress provided for a 12th NSC, with the intent of reprogramming that funding to the Coast Guard's Polar Security Cutter (PSC) program. The remaining $30.5 million would be used for procuring mission equipment for the 10th and 11th NSCs.16

Eight NSCs have entered service; the seventh and eighth were commissioned into service on August 24, 2019. The 9th through 11th are under construction; the 9th is scheduled for delivery in 2020. For additional information on the status and execution of the NSC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C.

OPC Program

Overview

Coast Guard officials describe the Offshore Patrol Cutter program and the Coast Guard's Polar Security Cutter (PSC) program17 as the service's two highest acquisition priorities. The Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 25 OPCs as replacements for the service's 29 medium-endurance cutters. The first four ships in the OPC program are being built by Eastern Shipbuilding Group (ESG) of Panama City, FL.

OPCs (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6)—also known as Heritage (WMSM-915)18 class cutters because they are being named for past cutters that played a significant role in the history of the Coast Guard and the Coast Guard's predecessor organizations19—are to be less expensive and in some respects less capable than NSCs.20 OPCs are to have a length of 360 feet, which will make them about 86% as long as NSCs, which have a length of 418 feet. OPCs were earlier estimated to have a full load displacement of 3,500 tons to 3,730 tons, which would have made them about 80% as large in terms of full load displacement as NSCs, which have a full load displacement of about 4,500 tons21 As the OPC design has matured, however, its estimated displacement has grown to about 4,500 tons, making it essentially as large as the NSC in terms of full load displacement.22

|

Figure 3. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: "Offshore Patrol Cutter Notional Design Characteristics and Performance," accessed September 16, 2016, at https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-9/Surface/OPC/OPC%20Placemat%2036x24.pdf?ver=2018-10-02-134225-297. |

|

Figure 4. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: Eastern Shipbuilding Group (http://www.easternshipbuilding.com/), accessed September 9, 2019. |

The Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of the 25 ships at $10.270 billion, or an average of about $411 million per ship.23 The first OPC was funded in FY2018. The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $546 million in procurement funding for the third OPC, LLTM for the fourth, and other program costs.

|

Figure 5. Offshore Patrol Cutter Artist's rendering |

|

|

Source: Image received from Coast Guard liaison office, May 25, 2017. |

The Coast Guard's Request for Proposal (RFP) for the OPC program, released on September 25, 2012, established an affordability requirement for the program of an average unit price of $310 million per ship, or less, in then-year dollars (i.e., dollars that are not adjusted for inflation) for ships 4 through 9 in the program.24 This figure represents the shipbuilder's portion of the total cost of the ship; it does not include the cost of government-furnished equipment (GFE) on the ship,25 or other program costs—such as those for program management, system integration, and logistics—that contribute to the above-cited figure of $411 million per ship.26

Competition and September 2016 Contract Award

In response to the September 25, 2012, RFP, at least eight shipyards expressed interest in the OPC program.27 On February 11, 2014, the Coast Guard announced that it had awarded Preliminary and Contract Design (P&CD) contracts to three of those eight firms—Bollinger Shipyards of Lockport, LA; Eastern Shipbuilding Group (ESG) of Panama City, FL; and General Dynamics' Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME.28

On September 15, 2016, the Coast Guard announced that it had awarded the detail design and construction (DD&C) contract to ESG. The contract covered detail design and production of up to 9 OPCs and had a potential value of $2.38 billion if all options were exercised.29

October 2019 Announcement of Contractual Relief and Follow-on Competition

On October 11, 2019, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), of which the Coast Guard is a part, announced that DHS had granted extraordinary contractual relief to ESG under P.L. 85-804 as amended (50 U.S.C. 1431-1435), a law originally enacted in 1958 that authorizes certain federal agencies to provide certain types of extraordinary relief to contractors who are encountering difficulties in the performance of federal contracts or subcontracts relating to national defense.30

|

Figure 6. OPC Functional Design "Placemat" summary from Coast Guard |

|

|

Source: Slide 11 from Coast Guard presentation at OPC Industry Day, December 11, 2019, updated December 13, 2019, accessed December 17, 2019, at https://beta.sam.gov/opp/bf0b9b0a1fe2428e9a73043259641c13/view. |

ESG reportedly submitted a request for extraordinary relief on June 30, 2019, after ESG's shipbuilding facilities were damaged by Hurricane Michael, which passed through the Florida panhandle on October 10, 2018. The Coast Guard announced that the contractual relief is limited to the first four hulls in the OPC program. DHS stated that the Coast Guard would immediately transition to conducting a follow-on competition for subsequent ships in the OPC program,31 identified later as ships 5 through 15 in the program. Under P.L. 85-804 as amended, Congress had 60 days of continuous session to review the announced contractual relief, with the 60-day period in this case starting October 11.32

January 10, 2020, RFP for Industry Studies

On January 10, 2020, the Coast Guard released a request for proposals (RFP) for industry studies in connection with its intended follow-on competition for ships 5 through 15 in the OPC program. Responses to the RFP were due by January 31, 2020.

The RFP posting included an attached notional timeline for the follow-on effort. Under this notional timeline, the contracts for industry studies were to be awarded in early March 2020 (they were awarded on March 20—see next section), and the studies are to be completed by October 10, 2020. A draft RFP for the detail design and construction (DD&C) contract for ships 5 through 15 is to be released around July 31, 2020; the final RFP is to be released around October 10, 2020; and proposals under the RFP are to be submitted by a date late in the third quarter of FY2021.

Under the Coast Guard's notional timeline, the DD&C contract is to be awarded on January 30, 2022. Ships 1 through 7 in the 25-ship program are to be built at a rate of one per year, with OPC-1 completing construction in FY2022 and OPC-7 completing construction in FY2028. The remaining 18 ships are to be built at a rate of two per year, with OPC-8 completing construction in FY2029 and OPC-25 completing construction in FY2038. These dates are generally 10 months to about 2 years later than they would have been under the Coast Guard's previous (i.e., pre-October 11, 2019) timeline for the OPC program.33

Under the new notional timeline, the Coast Guard's 14 Reliance-class 210-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 54 to 67 years old, and the Coast Guard's 13 Famous-class 270-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 42 to 52 years old.34

An October 18, 2019, Coast request for information (RFI) for the follow-on effort stated that "it is assumed that Shipbuilders would utilize the mature parts of the existing OPC functional design—to the maximum extent possible—and mature any incomplete aspects of the [OPC] detail design." This suggests that the Coast Guard envisioned that the fifth and subsequent OPCs would be built to a design that is largely similar to that of ESG's design for the first four OPCs.

March 20, 2020, Contract Awards for Industry Studies

On March 20, 2020, the Coast Guard announced that it had awarded nine industry study contracts in support of the follow-on competition for the OPC program. The contracts were awarded to

- Austal USA of Mobile, AL;

- General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME;

- Bollinger Shipyards Lockport of Lockport, LA;

- Eastern Shipbuilding Group (ESG) of Panama City, FL;

- Fincantieri Marinette Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WS;

- General Dynamics/National Steel and Shipbuilding Company (GD/NASSCO) of San Diego, CA;

- Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS:

- Philly Shipyard of Philadelphia, PA;

- VT Halter Marine Inc. of Pascagoula, MS.

Most of the contracts have a base award value of $2.0 million and a total potential value of $3.0 million. The exceptions are the contract awarded to ESG, which has a base award value of $1.1 million and a total potential value of $1.2 million (a difference that appears to reflect ESG's status as the builder of the first OPCs), and the contract awarded to VT Halter, which has a total potential value of $2.9 million.

The Coast Guard stated in its contract-award announcement that

Under their respective contracts, the awardees will assess OPC design and technical data, provided by the Coast Guard, and the program's construction approach. Based on their analyses, the awardees will recommend to the Coast Guard potential strategies and approaches for the follow-on detail design and construction (DD&C). The awardees will also discuss how they would prepare the OPC functional design for production. The awardees may also identify possible design or systems revisions that would be advantageous to the program if implemented, with strategies to ensure those revisions are properly managed.

The Coast Guard will use the industry studies results to further inform its follow-on acquisition strategy and promote a robust competitive environment for the DD&C award. Participation in industry studies is not a pre-requisite for submitting a DD&C proposal.35

Appendices with Additional Information

For additional general information on the status and execution of the OPC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C. For additional background information on the impact of Hurricane Michael on the OPC program at ESG, see Appendix E. For the text of a November 25, 2019, letter to the Acting Secretary of DHS from the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Chair and Ranking Member of that committee's Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation subcommittee regarding the restructuring of the OPC program under P.L. 85-804, see Appendix F.

FRC Program

Fast Response Cutters (Figure 7)—also called Sentinel (WPC-1101)36 class patrol boats because they are being named for enlisted leaders, trailblazers, and heroes of the Coast Guard and its predecessor services of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, U.S. Lifesaving Service, and U.S. Lighthouse Service37—are considerably smaller and less expensive than OPCs, but are larger than the Coast Guard's older patrol boats.38 FRCs are built by Bollinger Shipyards of Lockport, LA.

The Coast Guard's POR calls for procuring 58 FRCs as replacements for the service's 49 Island-class patrol boats.39 The POR figure of 58 FRCs is for domestic operations. The Coast Guard, however, operates six Island-class patrol boats in the Persian Gulf area as elements of a Bahrain-based Coast Guard unit, called Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA), which is the Coast Guard's largest unit outside the United States.40 Providing FRCs as one-for-one replacements for all six of the Island-class patrol boats in PATFORSWA would result in a combined POR+PATFORSWA figure of 64 FRCs.

|

Figure 7. Fast Response Cutter With an older Island-class patrol boat behind |

|

|

Source: U.S. Coast Guard photo accessed May 4, 2012, at http://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/6871815460/sizes/l/in/set-72157629286167596/. |

The Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission estimated the total acquisition cost of the 58 cutters at $3.748.1 billion, or an average of about $65 million per cutter.41 A total of 60 have been funded through FY2020, including four in FY2020. Four of the 60 are to be used by the Coast Guard in the Persian Gulf and are not counted against the Coast Guard's 58-ship POR for the program, which relates to domestic operations. Excluding these four FRCs, 56 FRCs for domestic operations have been funded through FY2020. The 36th FRC was commissioned into service on January 10, 2020.

The Coast Guard's proposed FY2021 budget requests $20 million in procurement funding for the FRC program; this request does not include funding for any additional FRCs.

For additional information on the status and execution of the FRC program from a May 2018 GAO report, see Appendix C.

Funding in FY2013-FY2021 Budget Submissions

Table 1 shows annual requested and programmed acquisition funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs in the Coast Guard's FY2013-FY2021 budget submissions. Actual appropriated figures differ from these requested and projected amounts.

Table 1. NSC, OPC, and FRC Funding in FY2013-FY2021 Budget Submissions

Figures in millions of then-year dollars

|

Budget |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

|

NSC program |

|||||||||||||

|

FY13 |

683 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

||||||||

|

FY14 |

16 |

710 |

38 |

0 |

45 |

||||||||

|

FY15 |

638 |

75 |

130 |

30 |

47 |

||||||||

|

FY16 |

91.4 |

132 |

95 |

30 |

15 |

||||||||

|

FY17 |

127 |

95 |

65 |

65 |

21 |

||||||||

|

FY18 |

54 |

65 |

65 |

21 |

6.6 |

||||||||

|

FY19 |

65 |

57.7 |

21 |

6.6 |

0 |

||||||||

|

FY20 |

60 |

21 |

6.6 |

5 |

5 |

||||||||

|

FY21 |

31 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||||||

|

OPC program |

|||||||||||||

|

FY13 |

30 |

50 |

40 |

200 |

530 |

||||||||

|

FY14 |

25 |

65 |

200 |

530 |

430 |

||||||||

|

FY15 |

20 |

90 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

||||||||

|

FY16 |

18.5 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

430 |

||||||||

|

FY17 |

100 |

530 |

430 |

530 |

770 |

||||||||

|

FY18 |

500 |

400 |

457 |

716 |

700 |

||||||||

|

FY19 |

400 |

457 |

716 |

700 |

689 |

||||||||

|

FY20 |

457 |

716 |

700 |

689 |

715 |

||||||||

|

FY21 |

546 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||||||

|

FRC program |

|||||||||||||

|

FY13 |

139 |

360 |

360 |

360 |

360 |

||||||||

|

FY14 |

75 |

110 |

110 |

110 |

110 |

||||||||

|

FY15 |

110 |

340 |

220 |

220 |

315 |

||||||||

|

FY16 |

340 |

325 |

240 |

240 |

325 |

||||||||

|

FY17 |

240 |

240 |

325 |

325 |

18 |

||||||||

|

FY18 |

240 |

335 |

335 |

26 |

18 |

||||||||

|

FY19 |

240 |

340 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

||||||||

|

FY20 |

140 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

||||||||

|

FY21 |

20 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||||||

|

Total |

|||||||||||||

|

FY13 |

852 |

410 |

400 |

560 |

890 |

||||||||

|

FY14 |

716 |

885 |

348 |

640 |

585 |

||||||||

|

FY15 |

768 |

505 |

450 |

780 |

792 |

||||||||

|

FY16 |

449.9 |

557 |

865 |

700 |

370 |

||||||||

|

FY17 |

467 |

865 |

820 |

920 |

809 |

||||||||

|

FY18 |

794 |

800 |

857 |

763 |

724.6 |

||||||||

|

FY19 |

705 |

854.7 |

757 |

726.6 |

709 |

||||||||

|

FY20 |

657 |

757 |

726.6 |

714 |

740 |

||||||||

|

FY21 |

597 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

||||||||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on FY2013-FY2021 budget submissions. n/a means not available.

Issues for Congress

Potential Impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Situation

One issue for Congress concerns the potential impact of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) situation on the execution of U.S. military shipbuilding programs, including the ones discussed in this report. For additional discussion of this issue, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Procurement Funding for 12th NSC

Another issue for Congress concerns procurement funding for a 12th NSC—whether to approve, reject, or modify the Coast Guard's proposed rescission of $70 million of the $101.5 million in FY2020 procurement funding that Congress provided for purchasing LLTM for a 12th NSC (with the intent of reprogramming that $70 million to the PSC program), and whether to provide any further procurement funding in FY2021 for a 12th NSC. Both of these questions relate to the issue of whether to procure a 12th NSC.

Supporters of procuring a 12th NSC could argue that a total of 12 NSCs would provide one-for-one replacements for the 12 retiring Hamilton-class cutters; that Coast Guard analyses showing a need for no more than 9 NSCs assumed dual crewing of NSCs—something that has not worked as well as expected; that the Coast Guard's POR record includes only about 61% as many new cutters as the Coast Guard has calculated would be required to fully perform the Coast Guard's anticipated missions in coming years;42 that the Coast Guard has recently begun to place more emphasis on deploying cutters the Western Pacific—an action that could increase demands for NSCs beyond what the Coast Guard anticipated when it established its program of record in 2004; and that the increase in the estimated displacement of the OPC to 4,500 tons—a figure about equal to the displacement of NSCs—makes procuring additional NSCs more suitable as a near-term measure for responding to potential delays in the restructured OPC program.

Skeptics or opponents of procuring a 12th NSC could argue that the Coast Guard's POR includes only 8 NSCs; that the Coast Guard's fleet mix analyses (see Appendix A) have not shown a potential need for more than 9 NSCs; that the Coast Guard intends to move expeditiously to proceed with its restructured effort to procure OPCs; and that in a situation of finite Coast Guard budgets, procuring a 12th NSC might reduce funding available for other Coast Guard programs, including the PSC program.

Number of FRCs to Procure in FY2021

Another issue for Congress concerns whether to approve the Coast Guard's proposal to procure no FRCs in FY2021, or instead procure some number of FRCs, such as two (which would be enough to either complete the program of record's goal of 58 FRCs for domestic operations, or to provide one-for-one replacements for all six of the Island-class patrol boats that the Coast Guard operates in the Persian Gulf), or four (which would be enough to do both of these things).

Supporters of the Coast Guard's proposal to procure no FRCs in FY2021 could argue that in a situation of finite Coast Guard funding, procuring additional FRCS in FY2021 could reduce funding for other Coast Guard programs, including the OPC and PSC programs, and that even if no FRCs are procured in FY2021, additional FRCs could still be procured in FY2022 or subsequent years.

Supporters of procuring two or four (or some other number of) FRCs in FY2021 could argue that this could complete the FRC's 58-shp program of record goal for domestic use, and/or replace all six of the Coast Guard's Island-class patrol boats in the Persian Gulf. They could argue that waiting until FY2022 or a subsequent fiscal year to procure these FRCs would increase their cost by creating a break in the shipyard's production learning curve for building the boats and incurring other program stop-and-restart costs.

Procurement Cost and Cost Effectiveness ofGrowth on OPCs 1 Through 4

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns how, if at all,an increase in the estimated procurement cost of the first four OPCs has changed as a result of the contractual relief the Coast Guard has provided to ESG under P.L. 85-804OPCs 1 through 4, and what implications, if any, suchthis cost growth might have regarding the cost -effectiveness of building each of these four cutters.

The Coast Guard states that as of mid-April 2020, the combined estimated procurement cost of OPCs 1 through 4 had increased by a total of between $300 million and $400 million since the Coast Guard's 2017 Life Cycle Cost Estimate (LCCE) for the program, with the increase on the cost OPC-1 being larger than the increases on the costs of OPCs 2 through 4, and that almost all of the increase is attributable to relief provided under P.L. 85-804.43 A combined increase of $300 million to $400 million for OPCS 1 through 4 would represent an increase of 18% to 24% above the $411 million average procurement effectiveness of building each of these four cutters.

A November 25, 2019, letter to the Acting Secretary of DHS from the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Chair and Ranking Member of that committee's Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation subcommittee regarding the OPC program (see Appendix F) states that under the Coast Guard's plan for providing contractual relief under P.L. 85-804, DHS and the Coast Guard plan to "spend up to an additional $659 million to complete those [four] cutters…." A figure of $659 million, if applied to the procurement cost of the first four OPCs, would equate to an average increase of about $165 million per ship, which would be an increase of roughly 40% above the $411 million average cost for each of 25 OPCs as estimated under the Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission. Potential oversight questions for Congress include the following:

- What was the estimated procurement cost for each of the first four OPCs under the Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission, and what is the estimated procurement cost for each of the first four OPCs under the Coast Guard's FY2021 budget submission?

- To the extent that the estimated costs for any of these four OPCs is higher in the Coast Guard's FY2021 budget submission than it is in the Coast Guard's FY2020 budget submission, what portion of the increase reflects the contractual relief that the Coast Guard is providing under P.L. 85-804?

How cost-effective is itOf the increase of $300 million to $400 million in the combined estimated procurement cost of OPCs 1 through 4, how much was due to the effects of Hurricane Michael? How cost-effective would it be to build each of these first four OPCs at their new estimated procurement costs, relative to potential alternatives such as procuring up to four additional NSCs, or up to four more of the OPCs that are to be built under the follow-on OPC construction contract that the Coast Guard intends to compete and award?- What potential, if any, is there for further cost growth on

the first four OPCsOPCs 1 through 4? - At what procurement cost would one or more of these first four OPCs no longer be cost effective to procure, relative to the potential alternatives mentioned above?

Contractual Relief and Follow-on Competition for OPC Program

More generally, the Coast Guard's proposed course of action for the OPC program raises a number of potential oversight questions for Congress, including those below.

Overall Course of Action

Potential oversight questions relating to the announced overall course of action include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- What potential overall courses of action did DHS and the Coast Guard examine for responding to the situation at ESG created by Hurricane Michael? For example, did DHS and the Coast Guard examine the option of immediately terminating the OPC contract, paying ESG any resulting contract-termination costs, and conducting a new competition to build OPCs starting with the first ship in the program? Alternatively, for example, did DHS and the Coast Guard examine the option of providing contractual relief to ESG under P.L. 85-804 as amended while maintaining the plan to build up to nine OPCs at ESG? What other potential overall courses of action were examined?

- What were the potential advantages and disadvantages of these and other potential overall courses of action?

- Why does DHS believe that the best overall course of action is to provide extraordinary contractual relief for a limited number of OPCs under P.L. 85-804 as amended and then conduct a follow-on competition for the remaining ships in the OPC program?

- What impact, if any, does the announced overall course of action for the OPC program have on the issue discussed in the next section regarding funding for a 12th National Security Cutter (NSC)?

Contractual Relief

Potential oversight questions relating to specifically the contractual relief include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- Why is ESG being granted financial and other contractual relief as a consequence of hurricane damage, when hurricanes are a known risk for communities on the Gulf Coast? Did ESG have insurance covering hurricane damage? If so, how much coverage did ESG have, and what payments did the insurance firm make to ESG? If ESG did not have insurance covering hurricane damage, why not?

- Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Congress provided $1.7 billion in reallocated emergency supplemental appropriations to pay estimated higher shipbuilding costs for 11 Navy ships under construction at the Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula, MS, and the Avondale shipyard upriver from New Orleans, LA.

4344 In what ways is that relief similar to or different from the relief being provided to ESG under P.L. 85-804 following Hurricane Michael? If financial relief for hurricane damage was provided to the Ingalls and Avondale shipyards, why should it not also be provided to ESG? By providing relief to Gulf Coast shipyards for hurricane damage, is the government creating a moral hazard that encourages Gulf Coast shipyards to reduce the amount of insurance coverage they purchase for hurricane damage, and if so, how if at all does that affect the prices they are able bid in competitions against shipyards located in other parts of the country? - Why does the contractual relief extend to four OPCs, as opposed to a smaller or greater number of OPCs?

- What is the dollar value of the contractual relief? As mentioned earlier, letter to the Acting Secretary of DHS from the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Chair and Ranking Member of that committee's Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation subcommittee regarding the OPC program (see Appendix F) states that under the Coast Guard's plan for providing contractual relief under P.L. 85-804, DHS and the Coast Guard plan to "spend up to an additional $659 million to complete those [four] cutters…." Is this figure is correct? How was it calculated?

Follow-On Competition

Potential oversight questions relating specifically to the follow-on competition for OPCs 5 through 15 include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- If a follow-on competition is conducted for building ships 5 through 15 in the OPC program, how much of a production learning curve advantage would ESG have as a result of having some amount of production learning curve experience in building its OPC design?

- As mentioned earlier, the Coast Guard envisions that OPCs 5 through 15 would be built to a design that is largely similar to that of ESG's design for the first four OPCs.

4445 What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of this approach compared to an approach under which bidders would be permitted to submit bids for building their own OPC designs? What actions, if any, are needed for the government to secure from ESG any design data rights that might be needed to conduct a competition limited to ESG's OPC design? - If OPCs 5 through 15 would be built to a design that is largely similar to that of ESG's design for the first four OPCs, how much of a design-related advantage (as opposed to a production learning curve advantage), if any, would that provide to ESG in the competition? To what degree, if any, does ESG's design for the OPC include features that are optimized for ESG's construction facilities?

- If a follow-on competition were to permit bidders to submit bids for building their own designs for the OPC, and the winner of the competition is a builder that has submitted a design different from ESG's design, what might be the longer-term implications of operating and supporting a class of perhaps no more than four OPCs built to ESG's design?

- If a follow-on competition is conducted for building ships 5 through 15 in the OPC program, will the bidders be required to submit bids for only a contract with options, or for both a contract with options and, alternatively, a block buy contract? (See the section below on the issue of annual or multiyear [block buy] contracting for OPCs.)

Regarding the second question above, pertaining to design data rights, the Coast Guard stated the following to CRS in September 2017:

Eastern Shipyard Group, Inc. (ESG) (or its subcontractors) owns the data rights to specific vessel design elements (e.g., hull form, etc.) that were developed wholly with contractor funds; however, the Coast Guard (in the OPC contract) has the ability to purchase rights regarding the hull form for re-procurement purposes. The data rights options for hulls 10-25 are contained within the contract under Section B [of ESG's OPC contract, called the Phase II contract]. A part of the Phase II contract's data and software rights clauses, the Coast Guard obtained either unlimited or government purpose data rights to vessel components and systems that were designed and/or developed using government funds or a mixture of contractor and government funds. As a result, the Coast Guard has data rights licenses for parts of the vessel design but not the complete vessel design.

To construct the OPC with a yard other than ESG (i.e., potentially for hulls 10-25) the Coast Guard would need to complete its data library by purchasing the data rights owned by ESG (or its subcontractors); pricing for the Coast Guard to procure the additional data rights specifically needed for re-procurement was provided as part of the Phase II contract.45

Regarding the fifth question above, as shown earlier in the excerpts from the Coast Guard's October 18, 2019, RFI, the Coast Guard is requesting that firms responding to the RFI "provide input on the potential use of a block buy contracting approach during the course of the program and recommendations for incorporation of such an approach if your company deems that block buy contracting is feasible. Also, if your company deems that block buy contracting is not feasible, explain the rationale against using this approach."

Notional Schedule

Potential oversight questions relating specifically to the Coast Guard's notional schedule for acquiring OPCs 5 through 25 include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- Does the schedule for soliciting and awarding industry studies for OPCs the fifth and subsequent OPCs provide proper amounts of time for firms to prepare bids for these contracts and to conduct the studies?

- Does the schedule provide a proper amount of time for the Coast Guard to evaluate the results of the industry studies and use the studies to inform the RFP for the DD&C contract?

- Would the envisioned procurement rate for the OPCs complete the OPC program too slowly, too quickly, or in about the right amount of time?

Regarding the final question above, as mentioned earlier, under the Coast Guard's new notional timeline, the Coast Guard's 14 Reliance-class 210-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 54 to 67 years old, and the Coast Guard's 13 Famous-class 270-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 42 to 52 years old.

November 25, 2019, House Committee Letter Regarding OPC Program

A November 25, 2019, letter to the Acting Secretary of DHS from the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Chair and Ranking Member of that committee's Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation subcommittee regarding the OPC program poses a number of questions regarding the Coast Guard's proposed course of action for the OPC program. The text of this letter, including these questions, is presented in Appendix F.

Risk of Procurement Cost Growth on OPCs 5-25

Another issue for Congress is the risk of procurement cost growth on OPCs 5 through 25, particularly given the increase in the OPC's estimated full load displacement from 3,500 to 3,730 tons as of May 2017 to 4,500 tons as of November 2019—an increase of more than 20%—and how this risk might affect the probability that OPCs can be built within the Coast Guard's affordability requirement for the OPC program of an average unit price of $310 million per ship, or less, in then-year dollars for ships 4 through 9 in the program for the shipbuilder's portion of the ship's total cost. Since, as a general matter, the cost of a ship of a given type is roughly proportional to its displacement, the increase of more than 20% in the OPC's estimated full load displacement raises a possibility that the cost to build OPCs may have increased, perhaps substantially, from earlier estimates. The draft statement of work (SOW) for the Coast Guard's intended follow-on competition for the OPC program that the Coast Guard posted on November 22, 2019, requires contractors responding to the RFI to provide, among other things, "a risk assessment of achieving the OPC Program's previously established affordability target for production OPCs."

Annual OPC Procurement Rate

The current procurement profile for the OPC, which reaches a maximum projected annual rate of two ships per year, would deliver OPCs many years after the end of the originally planned service lives of the medium-endurance cutters that they are to replace. As mentioned earlier, under the Coast Guard's new notional timeline, the Coast Guard's 14 Reliance-class 210-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 54 to 67 years old, and the Coast Guard's 13 Famous-class 270-foot medium-endurance cutters would be replaced when they would be (if still in service) about 42 to 52 years old. These ages, particularly for the Reliance-class cutters, would be very high, raising questions as to whether the ships could be made to last that long, and whether they would be able to cost effectively perform their missions at such ages.

Coast Guard officials have testified that the service plans to extend the service lives of the medium-endurance cutters until they are replaced by OPCs. There will be maintenance and repair expenses associated with operating aged medium-endurance cutters, particularly during their final years of intended service, and if the Coast Guard does not also make investments to increase the capabilities of these ships, the ships may have less capability in certain regards than OPCs.46

One possible option for addressing this situation would be to increase the maximum annual OPC procurement rate from the currently planned two ships per year to three or four ships per year. Doing this could result in the 25th OPC being delivered a few to several years sooner than under the currently planned maximum rate. Increasing the OPC procurement rate to three or four ships per year would require a substantial increase to the Coast Guard's Procurement, Construction, and Improvements (PC&I) account,4748 an issue discussed in Appendix B, and/or providing additional funding for the procurement of OPCs through the Navy's budget.

Increasing the maximum procurement rate for the OPC program could, depending on the exact approach taken, reduce OPC unit acquisition costs due to improved production economies of scale. It could also create new opportunities for using competition in the program. Notional alternative approaches for increasing the OPC procurement rate to three or four ships per year include but are not necessarily limited to the following:

- increasing the production rate to three or four ships per year at a single shipyard—an option that would depend on that shipyard's production capacity;

- using two shipyards for building OPCs to a single OPC design;

- using two shipyards for building OPCs to two designs, with each shipyard building OPCs to its own design—an option that would result in two OPC classes (similar to how the Coast Guard currently operates two primary classes of medium-endurance cutters); or

- building additional NSCs in the place of some of the planned OPCs—an option that might include de-scoping equipment on those NSCs where possible to reduce their acquisition cost and make their capabilities more like that of the OPC.

The fourth alternative above—which could be viewed as broadly similar to how the Navy is using a de-scoped version of the San Antonio (LPD-17) class amphibious ship as the basis for its LPD-17 Flight II (LPD-30) class amphibious ships4849—could be pursued in combination with one of the first three alternatives.

Annual or Multiyear (Block Buy) Contracting for OPCs

Another issue for Congress is whether to acquire OPCs 5 through 25 using annual contracting or multiyear contracting. The Coast Guard typically uses contracts with options for its shipbuilding programs. Although a contract with options may look like a form of multiyear contracting, it operates more like a series of annual contracts. Contracts with options do not achieve the reductions in acquisition costs that are possible with multiyear contracting. Using multiyear contracting involves accepting certain trade-offs.49

One form of multiyear contracting, called block buy contracting, can be used at the start of a shipbuilding program, beginning with the first ship. (Indeed, this was a principal reason why block buy contracting was in effect invented in FY1998, as the contracting method for procuring the Navy's first four Virginia-class attack submarines.5051) Section 311 of the Frank LoBiondo Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2018 (S. 140/P.L. 115-282 of December 4, 2018) provides permanent authority for the Coast Guard to use block buy contracting with economic order quantity (EOQ) purchases (i.e., up-front batch purchases) of components in its major acquisition programs. The authority is now codified at 14 U.S.C. 1137.

CRS estimates that if the Coast Guard were to use block buy contracting with EOQ purchases of components for acquiring the first several OPCs beginning with OPC 5, and either block buy contracting with EOQ purchases or another form of multiyear contracting known as multiyear procurement (MYP)5152 with EOQ purchases for acquiring the remaining ships in the program, the savings on the total acquisition cost of the 25 OPCs (compared to costs under contracts with options) could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

Another issue for Congress concerns the Coast Guard's planned NSC, OPC, and FRC procurement quantities. The POR's planned force of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs is about equal in number to the Coast Guard's legacy force of 90 high-endurance cutters, medium-endurance cutters, and 110-foot patrol craft. NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, moreover, are to be individually more capable than the older ships they are to replace. Even so, a Coast Guard analysis conducted in 2011 (the most recent such analysis that the Coast Guard has released) concluded that the planned total of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs would provide 61% of the cutters that would be needed to fully perform the service's statutory missions in coming years, in part because Coast Guard mission demands are expected to be greater in coming years than they were in the past. For further discussion of this issue, about which CRS has testified and reported on since 2005,5253 see Appendix A.

Legislative Activity for FY2021

Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2021 Procurement Funding Request

Table 2 summarizes appropriations action on the Coast Guard's request for FY2021 procurement funding for the NSC, OPC, and FRC programs.

Table 2. Summary of Appropriations Action on FY2021 Procurement Funding Request

Figures in millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth

|

Request |

Request |

HAC |

SAC |

Final |

|

NSC program |

31 |

|||

|

OPC program |

546 |

|||

|

FRC program |

20 |

|||

|

TOTAL |

597 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Coast Guard's FY2021 budget submission, HAC committee report, and SAC chairman's mark and explanatory statement on FY2021 DHS Appropriations Act. HAC is House Appropriations Committee; SAC is Senate Appropriations Committee.

Appendix A. Planned NSC, OPC, and FRC Procurement Quantities

This appendix provides further discussion on the issue of the Coast Guard's planned NSC, OPC, and FRC procurement quantities.

Overview

The Coast Guard's program of record for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs includes only about 61% as many cutters as the Coast Guard calculated in 2011 would be needed to fully perform its projected future missions. (The Coast Guard's 2011 analysis is the most recent such analysis that the Coast Guard has released.) The Coast Guard's planned force levels for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs have remained unchanged since 2004. In contrast, the Navy since 2004 has adjusted its ship force-level goals multiple times in response to changing strategic and budgetary circumstances.53

Although the Coast Guard's strategic situation and resulting mission demands may not have changed as much as the Navy's have since 2004, the Coast Guard's budgetary circumstances may have changed since 2004. The 2004 program of record was heavily conditioned by Coast Guard expectations in 2004 about future funding levels in the PC&I account. Those expectations may now be different, as suggested by the willingness of Coast Guard officials in 2017 to begin regularly mentioning the need for a PC&I funding level of $2 billion per year (see Appendix B).

It can also be noted that continuing to, in effect, use the Coast Guard's 2004 expectations of future funding levels for the PC&I account as an implicit constraint on planned force levels for NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs can encourage an artificially narrow view of Congress's options regarding future Coast Guard force levels and associated funding levels, depriving Congress of agency in the exercise of its constitutional power to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States, and to set funding levels and determine the composition of federal spending.

2009 Coast Guard Fleet Mix Analysis

The Coast Guard estimated in 2009 that with the POR's planned force of 91 NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs, the service would have capability or capacity gaps5455 in 6 of its 11 statutory missions—search and rescue (SAR); defense readiness; counterdrug operations; ports, waterways, and coastal security (PWCS); protection of living marine resources (LMR); and alien migrant interdiction operations (AMIO). The Coast Guard judges that some of these gaps would be "high risk" or "very high risk."

Public discussions of the POR frequently mention the substantial improvement that the POR force would represent over the legacy force. Only rarely, however, have these discussions explicitly acknowledged the extent to which the POR force would nevertheless be smaller in number than the force that would be required, by Coast Guard estimate, to fully perform the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years. Discussions that focus on the POR's improvement over the legacy force while omitting mention of the considerably larger number of cutters that would be required, by Coast Guard estimate, to fully perform the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years could encourage audiences to conclude, contrary to Coast Guard estimates, that the POR's planned force of 91 cutters would be capable of fully performing the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years.

In a study completed in December 2009 called the Fleet Mix Analysis (FMA) Phase 1, the Coast Guard calculated the size of the force that in its view would be needed to fully perform the service's statutory missions in coming years. The study refers to this larger force as the objective fleet mix. Table A-1 compares planned numbers of NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs in the POR to those in the objective fleet mix.

|

Ship type |

Program of Record (POR) |

Objective Fleet Mix From FMA Phase 1 |

Objective Fleet Mix compared to POR |

||

|

Number |

% |

||||

|

NSC |

8 |

9 |

+1 |

+13% |

|

|

OPC |

25 |

57 |

+32 |

+128% |

|

|

FRC |

58 |

91 |

+33 |

+57% |

|

|

Total |

91 |

157 |

+66 |

+73% |

|

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, Table ES-8 on page ES-13.

As can be seen in Table A-1, the objective fleet mix includes 66 additional cutters, or about 73% more cutters than in the POR. Stated the other way around, the POR includes about 58% as many cutters as the 2009 FMA Phase I objective fleet mix.

As intermediate steps between the POR force and the objective fleet mix, FMA Phase 1 calculated three additional forces, called FMA-1, FMA-2, and FMA-3. (The objective fleet mix was then relabeled FMA-4.) Table A-2 compares the POR to FMAs 1 through 4.

|

Ship type |

Program of Record (POR) |

FMA-1 |

FMA-2 |

FMA-3 |

FMA-4 (Objective Fleet Mix) |

|

NSC |

8 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

|

OPC |

25 |

32 |

43 |

50 |

57 |

|

FRC |

58 |

63 |

75 |

80 |

91 |

|

Total |

91 |

104 |

127 |

139 |

157 |

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, Table ES-8 on page ES-13.

FMA-1 was calculated to address the mission gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "very high risk." FMA-2 was calculated to address both those gaps and additional gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "high risk." FMA-3 was calculated to address all those gaps, plus gaps that the Coast Guard judged to be "medium risk." FMA-4—the objective fleet mix—was calculated to address all the foregoing gaps, plus the remaining gaps, which the Coast Guard judge to be "low risk" or "very low risk." Table A-3 shows the POR and FMAs 1 through 4 in terms of their mission performance gaps.

Table A-3. Force Mixes and Mission Performance Gaps

From Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1 (2009)—an X mark indicates a mission performance gap

|

Missions with performance gaps |

Risk levels of these performance gaps |

Program of Record (POR) |

FMA-1 |

FMA-2 |

FMA-3 |

FMA-4 (Objective Fleet Mix) |

|

Search and Rescue (SAR) capability |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Defense Readiness capacity |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Counter Drug capacity |

Very high |

X |

||||

|

Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security (PWCS) capacitya |

High |

X |

X |

|||

|

Living Marine Resources (LMR) capability and capacitya |

High |

X |

X |

[all gaps addressed] |

||

|

PWCS capacityb |

Medium |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

LMR capacityc |

Medium |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Alien Migrant Interdiction Operations (AMIO) capacityd |

Low/very low |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

PWCS capacitye |

Low/very low |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, page ES-11 through ES-13.

Notes: In the first column, The Coast Guard uses capability as a qualitative term, to refer to the kinds of missions that can be performed, and capacity as a quantitative term, to refer to how much (i.e., to what scale or volume) a mission can be performed.

a. This gap occurs in the Southeast operating area (Coast Guard Districts 7 and 8) and the Western operating area (Districts 11, 13, and 14).

c. This gap occurs in Alaska and in the Northeast operating area (Districts 1 and 5).

d. This gap occurs in the Southeast and Western operating areas.

Figure A-1, taken from FMA Phase 1, depicts the overall mission capability/performance gap situation in graphic form. It appears to be conceptual rather than drawn to precise scale. The black line descending toward 0 by the year 2027 shows the declining capability and performance of the Coast Guard's legacy assets as they gradually age out of the force. The purple line branching up from the black line shows the added capability from ships and aircraft to be procured under the POR, including the 91 planned NSCs, OPCs, and FRCs. The level of capability to be provided when the POR force is fully in place is the green line, labeled "2005 Mission Needs Statement." As can be seen in the graph, this level of capability is substantially below a projection of Coast Guard mission demands made after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (the red line, labeled "Post-9/11 CG Mission Demands"), and even further below a Coast Guard projection of future mission demands (the top dashed line, labeled "Future Mission Demands"). The dashed blue lines show future capability levels that would result from reducing planned procurement quantities in the POR or executing the POR over a longer time period than originally planned.

FMA Phase 1 was a fiscally unconstrained study, meaning that the larger force mixes shown in Table A-2 were calculated primarily on the basis of their capability for performing missions, rather than their potential acquisition or life-cycle operation and support (O&S) costs.

Although the FMA Phase 1 was completed in December 2009, the figures shown in Table A-2 were generally not included in public discussions of the Coast Guard's future force structure needs until April 2011, when GAO presented them in testimony.5556 GAO again presented them in a July 2011 report.56

The Coast Guard completed a follow-on study, called Fleet Mix Analysis (FMA) Phase 2, in May 2011. Among other things, FMA Phase 2 includes a revised and updated objective fleet mix called the refined objective mix. Table A-4 compares the POR to the objective fleet mix from FMA Phase 1 and the refined objective mix from FMA Phase 2.

As can be seen in Table A-4, compared to the objective fleet mix from FMA Phase 1, the refined objective mix from FMA Phase 2 includes 49 OPCs rather than 57. The refined objective mix includes 58 additional cutters, or about 64% more cutters than in the POR. Stated the other way around, the POR includes about 61% as many cutters as the refined objective mix.

Table A-4. POR Compared to Objective Mixes in FMA Phases 1 and 2

From Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1 (2009) and Phase 2 (2011)

|

Ship type |

Program of Record (POR) |

Objective Fleet Mix from FMA Phase 1 |

Refined Objective Mix from FMA Phase 2 |

|

NSC |

8 |

9 |

9 |

|

OPC |

25 |

57 |

49 |

|

FRC |

58 |

91 |

91 |

|

Total |

91 |

157 |

149 |

Source: Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 1, Executive Summary, Table ES-8 on page ES-13, and Fleet Mix Analysis Phase 2, Table ES-2 on p. iv.

Compared to the POR, the larger force mixes shown in Table A-2 and Table A-4 would be more expensive to procure, operate, and support than the POR force. Using the average NSC, OPC, and FRC procurement cost figures presented earlier (see "Background"), procuring the 58 additional cutters in the Refined Objective Mix from FMA Phase 2 might cost an additional $10.7 billion, of which most (about $7.8 billion) would be for the 24 additional FRCs. (The actual cost would depend on numerous factors, such as annual procurement rates.) O&S costs for these 58 additional cutters over their life cycles (including crew costs and periodic ship maintenance costs) would require billions of additional dollars.57

The larger force mixes in the FMA Phase 1 and 2 studies, moreover, include not only increased numbers of cutters, but also increased numbers of Coast Guard aircraft. In the FMA Phase 1 study, for example, the objective fleet mix included 479 aircraft—93% more than the 248 aircraft in the POR mix. Stated the other way around, the POR includes about 52% as many aircraft as the objective fleet mix. A decision to procure larger numbers of cutters like those shown in Table A-2 and Table A-4 might thus also imply a decision to procure, operate, and support larger numbers of Coast Guard aircraft, which would require billions of additional dollars. The FMA Phase 1 study estimated the procurement cost of the objective fleet mix of 157 cutters and 479 aircraft at $61 billion to $67 billion in constant FY2009 dollars, or about 66% more than the procurement cost of $37 billion to $40 billion in constant FY2009 dollars estimated for the POR mix of 91 cutters and 248 aircraft. The study estimated the total ownership cost (i.e., procurement plus life-cycle O&S cost) of the objective fleet mix of cutters and aircraft at $201 billion to $208 billion in constant FY2009 dollars, or about 53% more than the total ownership cost of $132 billion to $136 billion in constant FY2009 dollars estimated for POR mix of cutters and aircraft.58

A December 7, 2015, press report states the following:

The Coast Guard's No. 2 officer said the small size and advanced age of its fleet is limiting the service's ability to carry out crucial missions in the Arctic and drug transit zones or to meet rising calls for presence in the volatile South China Sea.

"The lack of surface vessels every day just breaks my heart," VADM Charles Michel, the Coast Guard's vice commandant, said Dec. 7.

Addressing a forum on American Sea Power sponsored by the U.S. Naval Institute at the Newseum, Michel detailed the problems the Coast Guard faces in trying to carry out its missions of national security, law enforcement and maritime safety because of a lack of resources.

"That's why you hear me clamoring for recapitalization," he said.

Michel noted that China's coast guard has a lot more ships than the U.S. Coast Guard has, including many that are larger than the biggest U.S. cutter, the 1,800-ton [sic:4,800-ton] National Security Cutter. China is using those white-painted vessels rather than "gray-hull navy" ships to enforce its claims to vast areas of the South China Sea, including reefs and shoals claimed by other nations, he said.

That is a statement that the disputed areas are "so much our territory, we don't need the navy. That's an absolutely masterful use of the coast guard," he said.

The superior numbers of Chinese coast guard vessels and its plans to build more is something, "we have to consider when looking at what we can do in the South China Sea," Michel said.

Although they have received requests from the U.S. commanders in the region for U.S. Coast Guard cutters in the South China Sea, "the commandant had to say 'no'. There's not enough to go around," he said.59

Potential oversight questions for Congress include the following:

- Under the POR force mix, how large a performance gap, precisely, would there be in each of the missions shown in Table A-3? What impact would these performance gaps have on public safety, national security, and protection of living marine resources?

- How sensitive are these performance gaps to the way in which the Coast Guard translates its statutory missions into more precise statements of required mission performance?

- Given the performance gaps shown in Table A-3, should planned numbers of Coast Guard cutters and aircraft be increased, or should the Coast Guard's statutory missions be reduced, or both?

- How much larger would the performance gaps in Table A-3 be if planned numbers of Coast Guard cutters and aircraft are reduced below the POR figures?

- Has the executive branch made sufficiently clear to Congress the difference between the number of ships and aircraft in the POR force and the number that would be needed to fully perform the Coast Guard's statutory missions in coming years? Why has public discussion of the POR focused mostly on the capability improvement it would produce over the legacy force and rarely on the performance gaps it would have in the missions shown in Table A-3?

- What projected mission demands or other factors may have changed since the Coast Guard's 2011 Fleet Mix Analysis, and how might these changes affect future required numbers of Coast Guard cutters and other Coast Guard assets?

60

61Appendix B. Funding Levels in PC&I Account

This appendix provides background information on funding levels in the Coast Guard's Procurement, Construction, and Improvements (PC&I) account.61

Overview

Table B-1 shows funding programmed in the PC&I account under the Coast Guard's FY2013-FY2021 budget submissions.

Table B-1. Funding in PC&I Account in FY2013-FY2020 Budgets

Figures in millions of dollars, rounded to nearest tenth

|

Budget |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

Avg. |

|

FY13 |

1,217.3 |

1,429.5 |

1,619.9 |

1,643.8 |

1,722.0 |

1,526.5 |

||||||||

|

FY14 |

951.1 |

1,195.7 |

901.0 |

1,024.8 |

1,030.3 |

1,020.6 |

||||||||

|

FY15 |

1,084.2 |

1,103.0 |

1,128.9 |

1,180.4 |

1,228.7 |

1,145.0 |

||||||||

|

FY16 |

1,017.3 |

1,125.3 |

1,255.7 |

1,201.0 |

1,294.6 |

1,178.8 |

||||||||

|

FY17 |

1,136.8 |

1,259.6 |

1,339.9 |

1,560.5 |

1,840.8 |

1,427.5 |

||||||||

|

FY18 |

1,203.7 |

1,360.9 |

1,602.7 |

1,810.6 |

1,687.5 |

1,533.1 |

||||||||

|

FY19 |

1,886.8 |

1,473.0 |

1,679.8 |

1,555.5 |

1,698.5 |

1,658.7 |

||||||||

|

FY20 |

1,234.7 |

1,679.8 |

1,555.5 |

1,698.5 |

1,737.0 |

1,581.1 |

||||||||

|

1,637.1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Coast Guard FY2013-FY2020 budget submissions. n/a means not available.

The Coast Guard has testified that funding the PC&I account at a level of about $1 billion to $1.2 billion per year (the average levels under the FY2014-FY2016 budget submissions) would make it difficult to fund various Coast Guard acquisition projects, including the PSC program and improvements to Coast Guard shore installations. Coast Guard plans call for procuring OPCs at an eventual rate of two per year. If each OPC costs roughly $400 million, procuring two OPCs per year in a PC&I account of about $1 billion to $1.2 billion per year, as programmed under the FY2014-FY2016 budget submissions, would leave about $200 million to $400 million per year for all other PC&I-funded programs.

Since 2017, Coast Guard officials have been stating more regularly what they stated only infrequently in earlier years—that executing the Coast Guard's various acquisition programs fully and on a timely basis would require the PC&I account to be funded at a level of about $2 billion per year. Statements from Coast Guard officials on this issue in past years have sometimes put this figure as high as about $2.5 billion per year.

Using Past PC&I Funding Levels as a Guide for Future PC&I Funding Levels

In assessing future funding levels for executive branch agencies, a common practice is to assume or predict that the figure in coming years will likely be close to where it has been in previous years. While this method can be of analytical and planning value, for an agency like the Coast Guard, which goes through periods with less acquisition of major platforms and periods with more acquisition of major platforms, this approach might not always be the best approach, at least for the PC&I account.

More important, in relation to maintaining Congress's status as a co-equal branch of government, including the preservation and use of congressional powers and prerogatives, an analysis that assumes or predicts that future funding levels will resemble past funding levels can encourage an artificially narrow view of congressional options regarding future funding levels, depriving Congress of agency in the exercise of its constitutional power to set funding levels and determine the composition of federal spending.

Past Coast Guard Statements About Required PC&I Funding Level

At an October 4, 2011, hearing on the Coast Guard's major acquisition programs before the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation subcommittee of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, the following exchange occurred:

REPRESENATIVE FRANK LOBIONDO:

Can you give us your take on what percentage of value must be invested each year to maintain current levels of effort and to allow the Coast Guard to fully carry out its missions?

ADMIRAL ROBERT J. PAPP, COMMANDANT OF THE COAST GUARD:

I think I can, Mr. Chairman. Actually, in discussions and looking at our budget—and I'll give you rough numbers here, what we do now is we have to live within the constraints that we've been averaging about $1.4 billion in acquisition money each year.

If you look at our complete portfolio, the things that we'd like to do, when you look at the shore infrastructure that needs to be taken care of, when you look at renovating our smaller icebreakers and other ships and aircraft that we have, we've done some rough estimates that it would really take close to about $2.5 billion a year, if we were to do all the things that we would like to do to sustain our capital plant.

So I'm just like any other head of any other agency here, as that the end of the day, we're given a top line and we have to make choices and tradeoffs and basically, my tradeoffs boil down to sustaining frontline operations balancing that, we're trying to recapitalize the Coast Guard and there's where the break is and where we have to define our spending.62

An April 18, 2012, blog entry stated the following:

If the Coast Guard capital expenditure budget remains unchanged at less than $1.5 billion annually in the coming years, it will result in a service in possession of only 70 percent of the assets it possesses today, said Coast Guard Rear Adm. Mark Butt.

Butt, who spoke April 17 [2012] at [a] panel [discussion] during the Navy League Sea Air Space conference in National Harbor, Md., echoed Coast Guard Commandant Robert Papp in stating that the service really needs around $2.5 billion annually for procurement.63

At a May 9, 2012, hearing on the Coast Guard's proposed FY2013 budget before the Homeland Security subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Admiral Papp testified, "I've gone on record saying that I think the Coast Guard needs closer to $2 billion dollars a year [in acquisition funding] to recapitalize—[to] do proper recapitalization."64

At a May 14, 2013, hearing on the Coast Guard's proposed FY2014 budget before the Homeland Security Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Admiral Papp stated the following regarding the difference between having about $1.0 billion per year rather than about $1.5 billion per year in the PC&I account:

Well, Madam Chairman, $500 million—a half a billion dollars—is real money for the Coast Guard. So, clearly, we had $1.5 billion in the [FY]13 budget. It doesn't get everything I would like, but it—it gave us a good start, and it sustained a number of projects that are very important to us.

When we go down to the $1 billion level this year, it gets my highest priorities in there, but we have to either terminate or reduce to minimum order quantities for all the other projects that we have going.