Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Changes from February 19, 2020 to June 13, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Contents

- Introduction

- Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

- Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Short-Term Disability Insurance

- State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Short-Term Disability Insurance Programs

- Research on Paid Family and Medical Leave

- Research on Paid Parental Leave in California

- Research on Paid Family Caregiving and Medical Leave

- Paid Family and Medical Leave in OECD Countries

- Recent Federal PFML Legislation and Proposals

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Private Sector Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Employer-Supported Short-term Disability Insurance, March 2019

- Table 2. State Family and Medical Leave Insurance Program Provisions, as of February 2020

- Table 3. Job Protection for State Leave Insurance Program Beneficiaries

- Table 4. Paid Family Caregiving Leave Policies in Selected OECD Countries as of June 2016

- Table 5. Sickness Benefit Policies in OECD Countries, September 2016

Summary

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the

June 13, 2022

United States

Sarah A. Donovan

Paid family and medical leave (PFML) refers to partially or fully compensated time away from

Specialist in Labor Policy

work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs, such as the arrival of a new

child or serious illness of a close family member, or an employee'’s own serious medical needs. In general, day-to-day needs for leave to attend to family matters (e.g., a school conference or

lapse in child care coverage), a minor illness, and preventive care are not included among family and medical leave categories.

Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA; P.L. 103-3) provides eligible workers with a federal entitlement to unpaidunpaid leave for a limited set of family caregiving and medical needs, no federal law requiresdoes not require private-sector employers to provide paidpaid leave of any kind. Currently, employees may access paid family or medical leave if it is offered by an employer or they may use leave insurance benefits (such as temporary disability insurance or, less commonly, family leave insurance) to finance unpaid medical leave or family caregiving leaveoffered by an employer or, in the case of serious medical needs, finance medical leave by combining unpaid leave with short-term disability insurance. In addition, workers in certain states may be eligible for state family and medical leave insurance benefits that can provide some income support during periods of leave.

Employer provision of PFML in the private sector is voluntary, although some states and localities require employers to allow employees to accrue paid sick leave or paid time off that may, in some cases, be used for short family and medical absences. According to a national survey of employers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1823% of private-industry employees had access to paid family leave (i.e., parental leave and family caregiving leave) through their employers in March 20192021, and 42% had access to employer-supported short-term disability insurance policies. The availability of these benefits was more prevalent among professional and technical occupations and industries, high-paying occupations, full-time workers, and workers in large companies (as measured by number of employees). Announcements by several large companies in recent years indicate that access may be increasing among certain groups of workers.

In addition, some states 12 states (including the District of Columbia) have enacted legislation to create state paid family and medical leave insurance programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain caregiving activities or for whom a serious medical issue interferes with their regular work duties. California, Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, and Washington currentlyAs of May 2022, eight states operate such programs, which offer 168 to 52 weeks of total benefits to eligible workers in a benefit year (in those states, total family leave insurance benefits are limited to 4 to 12 weeks). The New York program began phased implementation in 2018 and will be fully implemented in 2021. Three other states and the District of Columbia5 to 12 weeks). Four other states have enacted laws creating such programs, but they are not yet implemented and paying benefits.

implemented and paying benefits. The District of Columbia legislation took effect in April 2017, with benefit payments scheduled to start in July 2020. Massachusetts's program was signed into law in June 2018; its benefit payments are to begin in January 2021. Connecticut and Oregon enacted legislation in 2019; benefit payments are to begin in January 2022 and January 2023, respectively.

Many advanced-economy countries entitle workers to some form of compensated family and medical leave. Whereas some provide for leave to employees engaged in family caregiving (e.g., of parents, spouses, and other family members), many emphasize leave for new parents, mothers in particular. TheAs of 2020, the United States is the only OrganizationOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member country to not provide for paid leave to new mothers employed in the private sector. A smaller majority of member countries provides benefits to fathers and other non-birth parents. Caregiving benefits of some type are provided in nearly 75% of OECD countries. Few OECD member countries do not provide a medical leave benefit (either through social insurance, an employer mandate, or both) for absences resulting from workers’ serious medical needs.

private sector. Medical leave policies also vary across OECD countries, with most providing for at least six months of leave with some pay. According to analysis by the World Policy Analysis Center, South Korea and the United States are the only OECD member countries that do not provide paid medical leave to employees.

There is currently a tax incentive in the United States for employers that provide qualifying paid family and medical leave to low- and moderate-incomecertain employees. This incentive is temporary, and is scheduled to expire at the end of 20202025. Proposals to expand national access to paid family and medical leave have been introduced in the 116th Congress, such as the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act; S. 463/H.R. 1185), which proposes to create a national wage insurance program for persons engaged in family caregiving activities or who take leave for their own serious health condition (i.e., a family and medical leave insurance program), and the New Parents Act (S. 920/ H.R. 1940) which would allow parents of a new child to receive advanced Social Security benefits for the purposes of financing parental leave. Several legislative proposals in the 116th Congress would use the tax code to support family and medical leave taking.

Introduction

117th Congress. For example, the Build Back Better Act (H.R. 5376) proposed, among other things, a new federal cash benefit for eligible individuals engaged in certain types of family and medical caregiving. Using a different approach, the Expanding Small Employer Pooling Options for Paid Family Leave Act of 2021 (H.R. 5161) proposed to allow multiple employer welfare arrangements that may potentially create additional opportunities for certain employers to pool risk and affect the costs of providing such benefits.

This report provides an overview of PFML in the United States, summarizes state-level family and medical leave insurance program provisions, reviews PFML policies in other advanced-economy countries, and describes recent federal legislative action to increase access to paid family leave.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 15 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 33 link to page 38 link to page 38 link to page 41 link to page 24 link to page 37 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States ...................................................................... 2

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Short-Term Disability Insurance ......................... 3 State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Temporary Disability Insurance

Programs ................................................................................................................................ 7

Research on Paid Family and Medical Leave ......................................................................... 12

Research on Paid Parental Leave in California ................................................................. 13 Research on Paid Family Caregiving and Medical Leave ................................................ 14

Family and Medical Leave Benefits in OECD Countries ............................................................. 16

Parental Leave Benefits ........................................................................................................... 16 Other Family Caregiving Benefits .......................................................................................... 18 Medical Leave Benefits ........................................................................................................... 19

Recent Federal PFML Legislation and Proposals ......................................................................... 19

Figures Figure 1. Weeks of Total Benefits Available in a Benefit Year under State Leave

Insurance Programs, May 2022 .................................................................................................... 8

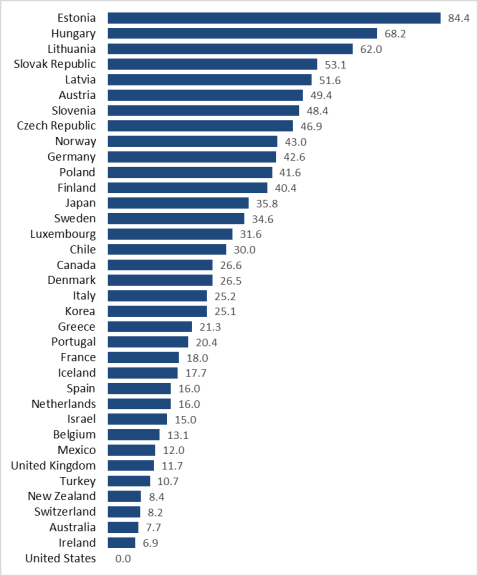

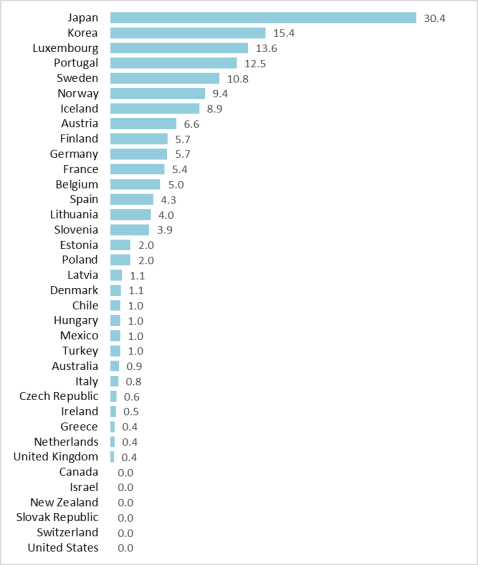

Figure 2. State Leave Insurance Programs, Selected Benefit Information as of May 2022 ........... 11 Figure 3. Average Full-Wage Equivalent Weeks of Paid Leave Available to Mothers .................. 17 Figure 4. Average Full-Wage Equivalent Weeks of Paid Leave Available to Fathers ................... 18

Tables Table 1. Private Sector Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave

and Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance, March 2021 .................................... 5

Table A-1. State Family and Medical Leave Insurance Program Provisions, as of May

2022 ............................................................................................................................................ 20

Table A-2. Job Protection for State Leave Insurance Program Beneficiaries ................................ 29 Table B-1. Paid Family Caregiving Leave Policies in Selected OECD Countries as of

January 2020 .............................................................................................................................. 34

Table B-2. Medical Leave Benefits in OECD Member Countries ................................................ 37

Appendixes Appendix A. State Leave Insurance Programs, Selected Provisions as of May 2022 ................... 20 Appendix B. Caregiving Leave and Medical Leave Benefits in OECD Countries ....................... 33

Congressional Research Service

link to page 46 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 42

Congressional Research Service

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Introduction Paid family and medical leave (PFML) refers to partially or fully compensated time away from work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs (paid family leave) or for the employee'employee’s own serious medical condition (paid medical leave). Family caregiving needs include those such as the arrival of a new child or serious illness of a close family member. Medical conditions that may qualify for medical leave generally must be severe enough to require medical intervention and interfere with a worker'’s performance of key job responsibilities. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA; P.L. 103-3, as amended) provides eligible workers with a federal entitlement to unpaid leave for a limited set of family caregiving needs, no federal law requiresdoes not require private-sector employers to provide paid leave of any kind.1

1

Currently, employees may access PFML if offered by an employer.22 Employers that provide paid family and medical leavePFML may qualify for a federal tax credit (the Employer Credit for Paid Family and Medical Leave). The tax credit is up to 25% of paid leave wages paid to qualifying employees.3, and is designed to encourage employers to provide PFML to their employees by reducing the cost to employers of providing such leave.3 Qualifying employees include those whose earnings do not exceed 60% of a "“highly compensated employee" threshold ($72,000 in 2018). This tax credit was first enacted as part of the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97, of commonly the "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act"). It was extended through 2020 as part of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94).

Some workers may finance unpaid absences for certain serious medical needs through short-term disability insurance. ” threshold (the tax credit earnings threshold is 60% x $135,000 = $81,000 in 2022). The tax credit is available through December 2025.

Some workers may use leave insurance benefits (such as temporary disability insurance or, less commonly, family leave insurance4) to finance unpaid medical leave or family caregiving leave. In addition, some states have created family and medical leave insurance programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain (state-identified) family caregiving activities or who must be absent from work as a result of the worker'’s own significant medical needs.45 In these states, workers can mitigate lost earnings during periods of unpaid

1 The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) allows employees to use employer-provided paid leave during periods of unpaid FMLA-entitled leave. An overview of FMLA is in CRS Report R44274, The Family and Medical Leave Act: An Overview of Title I, by Sarah A. Donovan. Workers who are covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may also qualify for unpaid leave in certain cases, and employers cannot apply separate rules governing paid leave for workers with and without disabilities. For more information see Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Employer-Provided Leave and the Americans with Disabilities Act, May 9, 2016, https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/publications/ada-leave.cfm.

2 The federal government, for example, became one such employer in December 2019 with the enactment of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (FY2020 NDAA, P.L. 116-92). The FY2020 NDAA created a new paid parental leave benefit (i.e., leave for the arrival of a new child and for bonding with that child) for most federal civil service employees. The paid leave must be taken together with the federal employee’s FMLA entitlement. An overview of the FY2020 NDAA, including information on the paid parental leave benefit is in CRS Report R46144, FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act: P.L. 116-92 (H.R. 2500, S. 1790), by Pat Towell.

3 For more information see CRS In Focus IF11141, Employer Tax Credit for Paid Family and Medical Leave, by Molly F. Sherlock.

4 For example, certain employees in New Hampshire will soon be able to opt in to a family leave insurance program operated by a commercial insurance carrier that is to cover New Hampshire state employees. Governor Chris Sununu, “Full Steam Ahead: NH Releases Paid Family Medical Leave Request for Proposal (RFP),” press release, March 2022, https://www.governor.nh.gov/news-and-media/full-steam-ahead-nh-releases-paid-family-medical-leave-rfp. In April 2022, Virginia law established family leave insurance as a class of insurance in the state. The law defines family leave insurance as an insurance policy issued to an employer and related to an employee benefit program to cover a portion of earnings lost due to specified family care reasons. It provides that policies may be included in a short-term disability policy (including as an amendment or rider to such a policy), or written as a separate group insurance policy purchased by an employer. Virginia General Assembly, Acts of Assembly, Ch. 131, approved April 7, 2022.

5 In some states, medical leave is financed through state short-term disability insurance programs (sometimes called temporary disability insurance (TDI), in this context).

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 16 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

family and medical leave by combining an entitlement to unpaid leave with state-provided insurance benefits.

Some congressional proposals introduced in the 117th Congress seek to enhance national access to paid family and medical leave by expanding upon existing mechanisms (i.e., voluntary employer provision or financing of leave through social insurance). For example, the Expanding Small Employer Pooling Options for Paid Family Leave Act of 2021 (H.R. 5161, 117th Congress) proposes to allow multiple employer welfare arrangements (MEWAs), as covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA; P.L. 93-406), to include family and medical leave benefits, which may potentially create additional opportunities for certain employers to pool risk and affect the costs of providing such benefits. Similar to the state leave insurance approach, the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act; H.R. 804 and S. 248, 117th Congress) proposes to create a national wage insurance program for persons engaged in family caregiving activities or who are unable to work as a result of their own serious health condition.

In these states, workers can finance family and medical leave by combining an entitlement to unpaid leave with state-provided insurance benefits.

Some congressional proposals seek to enhance national access to paid family and medical leave by expanding upon existing mechanisms (i.e., voluntary employer provision or financing of leave through social insurance). The Paid Family Leave Pilot Extension Act (S. 1628/H.R. 4964) proposes to support voluntary employer-provided PFML by extending the employer tax credit for such leave to December 2022, and—similar to the state insurance approach—the Family and Medical Insurance Act (FAMILY Act; S. 463/H.R. 1185) proposes to create a national wage insurance program for persons engaged in family caregiving activities or who take leave for their own serious health condition. Other proposals such as the New Parents Act (S. 920/ H.R. 1940) would allow parents of a new child to receive Social Security benefits, to be repaid at a later date, for the purposes of financing parental leave. Another set of proposals would amend the tax code to support individuals saving for their own family and medical leave purposes (e.g., the Working Parents Flexibility Act of 2019 (H.R. 1859) and the Freedom for Families Act (H.R. 2163)); the Support Working Families Act (S. 2437) would provide a parental leave tax credit to individuals taking parental leave.

Members of Congress who support increased access to paid leave generally cite as their motivation the significant and growing difficulties some workers face when balancing work and family responsibilities, and the financial challenges faced by many working families that put unpaid leave out of reach. Expected benefits of expanded access to PFML include stronger labor force attachment for family caregivers and workers experiencing serious medical issues, and greater income stability for their families; and improvements to worker morale, job tenure, and other productivity-related factors. Some studies identify a relationship between paid leave and family well-being as measured by a range of outcomes (e.g., child health, mothers'’ mental well-being).56 Some Members have expressed concerns about new policies to expand access to paid family and medical leave citing the potentially high costs of such policies. Potential costs include the financing of payments made to workers on leave, other expenses related to periods of leave (e.g., hiring a temporary replacement or productivity losses related to an absence), and administrative costs. In the case of tax incentives, there is a cost in terms of forgone federal tax revenue.67 The magnitude and distributions of costs and benefits would depend on how the policy is implemented, including the size and duration of benefits, how benefits are financed, and other policy factors.

This report provides an overview of PFML in the United States, summarizes state-level family and medical leave insurance program provisions, reviews PFML policies in other advanced-economy countries, and describes recent federal legislative action to increase access to paid family leave.

and medical leave. Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Throughout their careers, many workers encounter a variety of medical needs and family caregiving obligations that conflict with work time. Some of these are broadly experienced by working families but tend to be short in duration, such as episodic child care conflicts, school meetings and events, routine medical appointments, and minor illnesses experienced by the employee or an immediate family member. Others are more significant in terms of their impact on families and the amount of leave needed, but occur less frequently in the general worker population, such as the arrival of a new child or a serious medical condition that requires inpatient 6 For a discussion see the “Research on Paid Family and Medical Leave” section of this report. 7 The tax credit for employer provided paid family and medical leave was estimated to reduce federal income tax revenue by $4.3 billion when it was first enacted for 2018 and 2019 as part of P.L. 115-97. The 10-year budget window estimate of the two-year tax credit can be found in Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,” JCX-67-17, December 18, 2017. Congressional Research Service 2 link to page 11 link to page 11 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States care or continuing treatment. Although all these needs for leave may be consequential for working families, the term family and medical leave is generally used to describe the latter, more significant and disruptive group of needs that can require longer periods of time away from work.

As defined in recent federal proposals, family caregiving and medical needs that would be eligible for leave generally include the following:

caring for and bonding with the arrival and care of a newborn child or a newly-placed adopted or fostered child (i.e., a"“newly-arrived child"),attending to”), the serious medical needs of certain close family members, andattending to the employee'’s own serious medical needs that interfere with the performance of his or her job duties.7

8

In practice, day-to-day needs for leave to attend to family matters (e.g., a school conference or lapse in child care coverage), minor illness (e.g., common cold), or preventive care are not generally included among family and medical leave categories.8

9

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Short-Term Disability Insurance

Disability Insurance Although federal law does not require private sector employers to provide paid family or medical leave to their employees, some employers offer such paid leave to their employees as a voluntary benefit.910 Employers can provide the paid leave directly (i.e., by continuing to pay employees during period of leave), but financing potentially-financing potentially-long periods of leave can be cost prohibitive in some cases. As an alternative, some employers offer short-term disability insurance (STDI) to employees to reduce wage-loss during periods of unpaid medical leave (i.e., when employees are unable to work due to a non-work-related injury or illness).1011 Such policies can be purchased from privatecommercial insurance companies, which pay cash benefits to covered employees when certain conditions are met.

STDI reduces wage-loss (during periods of unpaid leave) related to a covered employee'’s own medical needs, but does not pay benefits when an employee'’s absence is related to caregiving, bonding with a new child, or the family military needs that are included in some definitions of family leave. STDI benefits may be claimed for pregnancy- or childbirth related disabilities, however, and -related disabilities, and

8 Some recent federal proposals would also provide paid leave or cash benefits to workers with certain military family needs (e.g., the FAMILY Act) or for needs related to the death of a family member (e.g., the Build Back Better Act, as introduced in H.R. 5376 [117th Congress] on September 27, 2021).

9 Some federal proposals would increase access to other types of paid leave, such as paid sick leave that could be used for absences related to minor illness, routine care, and other needs. Proposed paid sick leave entitlements are often relatively short in duration. For example, the Healthy Families Act (H.R. 2465 and S. 1195, 117th Congress) would require certain employers to allow their employees to earn 1 hour of leave per 30 hours of work, up to a maximum of 56 hours per year. The bill would allow employees to use such leave to attend to medical needs (including routine medical appointments), to attend a child’s school meeting, and for certain medical, legal or other needs related to domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking, among other uses.

10 In some states, an employer’s provision of or contributions to short-term disability insurance (or temporary disability insurance)—one mechanism workers can use to finance unpaid medical leave—is not voluntary. See the “State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Temporary Disability Insurance Programs” section of this report for a discussion.

11 Workers’ compensation provides cash and medical benefits to workers who suffer a work-related injury or illness, and benefits to the survivors of workers killed on the job. For discussion see CRS Report R44580, Workers’ Compensation: Overview and Issues, by Scott D. Szymendera.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 5 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

as such may be used to finance a portion of maternity leave in some circumstances.12as such may be used to finance a portion of maternity leave in some circumstances.11 Family leave insurance (FLI), a newer concept, provides cash benefits to workers engaged in certain caregiving activities. Currently, FLI is not broadly available from private insurance companies.12 13 As a result, many employers seeking to provide leave for family caregiving must provide the leave benefit directly (i.e., offer paid family leave).

According to a national survey of employers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 1823% of private-industry employees had access to paid family leave (separate from other leave categories) through their employer in March 2019.132021.14 The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave provided specifically to care for a family member, parental leave (i.e., for a new child's ’s arrival), and maternity leave that is granted in addition to any sick leave, annual leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee. BLS does not collect information on employer-provided paid medical leave, but does estimate access to employer-supported STDI.1415 In March 20192021, 42% of private sector employees had access to STDI policies that were financed fully or in-part by their employers. STDI benefits often replace a set percentage of an employee'’s earnings, sometimes up to a maximum weekly benefit amount (e.g., a policy might replace 50% of earnings lost while the employee is unable to work up to $600 per week); in other cases the wage replacement rate may vary by workers'’ annual earnings or workers may receive a flat dollar amount (e.g., $200 per week). BLS reports that among workers who receive a fixed percentage of lost earnings (72% of those private industry workers with STDI coverage), the median fixed percentage was 60%. Of those subject to a maximum weekly benefit, the median maximum benefit was $637881 per week. The median number of benefit weeks available to employees with access to STDI plans was 26 weeks.15

As shown in Table 1, 16

12 This is because maternity leave generally describes time off work for a combination of needs: (1) leave for a mother’s physical recovery from childbirth, and (2) time to care for and bond with a new child. The first is technically medical or disability-related leave, as it is leave from work for the mother’s own incapacitation. STDI benefits may be paid to a pregnant woman or new mother under these circumstance, but are not available to non-birth parents (e.g., fathers, parents of adopted children). The second component of maternity leave is considered family or caregiving leave, taken to care for or bond with the newly-arrived child, and is not covered by STDI.

13 Some states with leave insurance programs allow employers to purchase private leave insurance plans—including plans that cover family leave insurance claims—and New York state requires that employers purchase such privately-insured coverage. If interest from employers in private plans is sufficiently large, the availability of private FLI policies may increase (i.e., such that employers in states without leave insurance programs may purchase FLI policies). See footnote 4 for information on a change in Virginia law that may increase employers’ access to commercial FLI policies in that state. As of 2022, the market is too small to be reported as a separate line of insurance (i.e., it is subsumed in other lines of insurance) when reported to insurance regulators.

14 The BLS-measure is inclusive of paid maternity- or paternity- only plans (i.e., it may be the case the share of private sector workers with access to employer-provided paid leave to care for a seriously-ill spouse was less than 23% in March 2021). An employer that makes a full or partial payment towards an insurance plan (including a state leave insurance plan covering family leave) is considered by BLS to provide paid family leave. If there is no employer contribution to the plan (employee-paid only), then such an insurance plan is not considered to be an employer-provided benefit.

15 BLS also collects information on employer-provided paid sick leave, which may be used for needs that would qualify for medical leave (e.g., an overnight hospital stay) and for a broader set of needs as well (e.g., minor ailments, annual physical). Whereas federal proposals seek to provide several weeks or months of paid medical leave, employer-provided sick leave tends to be one week or less per year. BLS estimates that 77% of private sector workers had access to employer-provided paid sick leave in March 2021; the median number of days that could be earned in a given year was six (among those limited to a fixed number of sick days per year). BLS, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2021, September 2021.

16 The 90th percentile value was also 26 weeks, suggesting that STDI plans offering more than 26 weeks of benefits were relatively rare. Ninety percent of workers with access to plans had at least 12 weeks of benefits and 75% had at least 13 weeks of benefits.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9 link to page 9 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

As shown in Table 1, employee access to employer-provided paid family leave and employer-supported STDI is not uniform across occupations and industries, and varies widely across wage groups. In particular, access was more prevalent among managerial and professional occupations; information, financial, and professional and technical service industries; high-paying occupations; full-time workers; and workers in relatively large companies (as measured by number of employees). Announcements by several large companies suggest that access to related types of paid leave may be increasing among certain groups of workers.17 This is also may be partially-reflected in BLS statistics which indicate a 25 percentage point increase in private sector workers'’ access to paid family leave between March 2018 (162019 (18%) and March 2019 (18%). The share of 2021 (23%).18 However, access rates did not increase for all groups over this period (e.g., the share of private sector workers in the leisure and hospitality industry with access to employer-provided paid family leave fell from 11% in March 2019 to 9% in March 2021; trend not shown in Table 1). The share of all private sector employees with access to employer-supported STDI did not increase over that time period; it was 42% in March 20182019 and March 2019.2021.

Table 1. Private Sector Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family

Leave and Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance, March 2021

Employer-Supported

Employer-Provided

Short-Term Disability

Paid Family Leave

Insurance

Category

(% of workers)

(% of workers)

All Workers

23%

42%

By Occupation

Management, professional, and related

37%

57%

Service

13%

22%

Sales and office

25%

41%

17 Among new company policies announced in recent years, some emphasize parental leave (i.e., leave taken by mothers and fathers in connection with the arrival of a new child), and others offer broader uses of leave. Examples of companies that offer paid leave benefits for broader purposes include Google, which recently increased the number of weeks of leave available to employees who give birth from 18 to 24, the number of weeks of parental leave for non-birthing parents from 12 to 18, and the number of weeks for caregiver leave from 4 to 8; Goldman Sachs, which, in addition to preexisting family leave policies, now offers 5 days of paid bereavement leave for a non-immediate family member, 20 days of paid leave for the loss of an immediate family member, and 20 days of paid leave if the employee, employee’s spouse, or surrogate experiences a miscarriage or stillbirth; Levi Strauss & Co.’s, which offers employees 8 weeks of paid family leave to care for family members with serious health conditions in addition to 8 weeks of paid leave to care for a new child; the U.S. Steel Corporation, which offers non-union ("non-represented”) employees 8 weeks of paid time off for a new child (in addition to 6-8 weeks of short-term disability for birth mothers), extended bereavement leave (up to 15 days) for the death of an immediate family member, and the ability to purchase additional vacation days. Google’s policy change announcement was reported in several newspapers, including at https://www.businessinsider.com/google-increases-vacation-days-and-parental-leave-for-employees-benefits-2022-1; Godman Sachs’s policy change was reported at https://www.wsj.com/articles/goldman-sachs-rolls-out-new-worker-benefits-to-combat-employee-burnout-11638210617; Levi Strauss & Co. announced its new policy at https://www.levistrauss.com/2020/02/27/levi-strauss-co-introduces-paid-family-leave/; U.S. Steel Corporation announced its new policy on March 21, 2019 at https://www.ussteel.com/media/newsroom/-/blogs/u-s-steel-announces-enhanced-benefits-for-workforce.

18 The increase in access to paid family leave between March 2019 and March 2021 may also reflect a compositional change in the employment, resulting from the disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on certain groups of workers, such as those employed in the leisure and hospitality sector, who tend to have relatively low access to paid leave. Disproportionate job loss among such groups can raise the share of workers with access to paid leave even if employer policies do not change (i.e., because a portion of workers without such access to the benefit are no longer included among employed workers).

Congressional Research Service

5

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Employer-Supported

Employer-Provided

Short-Term Disability

Paid Family Leave

Insurance

Category

(% of workers)

(% of workers)

Natural resources, construction, and maintenance

15%

36%

Production, transportation, and material moving

13%

48%

By Industry

Construction

12%

28%

Manufacturing

21%

64%

Trade, Transportation, and Utilities

21%

42%

Information

45%

71%

Financial Activities

41%

67%

Professional and Technical Services

37%

61%

Administrative and Waste Services

9%

20%

Education and Health Services

28%

35%

Leisure and Hospitality

9%

18%

Other Services

15%

29%

By Average Occupational-Wage Distribution

Bottom 25%

12%

19%

Second 25%

21%

42%

Third 25%

25%

48%

Top 25%

37%

64%

By Hours of Work Status

Ful -time

27%

50%

Part-time

11%

18%

By Establishment Size

1 to 99 employees

17%

31%

100 to 499 employees

28%

51%

500 or more employees

35%

64%

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2021 Employee Benefits Survey, September 2021, Table 17 (insurance) and Table 33 (paid leave). Notes: The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave “mothers and fathers in connection with the arrival of a new child), and others offer broader uses of leave.16

Table 1. Private Sector Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance, March 2019

|

Category |

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave (% of workers) |

Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance (% of workers) |

|

|

All Workers |

18% |

42% |

|

|

By Occupation |

|||

|

Management, professional, and related |

30% |

58% |

|

|

Service |

12% |

24% |

|

|

Sales and office |

18% |

41% |

|

|

Natural resources, construction, and maintenance |

11% |

35% |

|

|

Production, transportation, and material moving |

9% |

48% |

|

|

By Industry |

|||

|

Construction |

8% |

29% |

|

|

Manufacturing |

5% |

65% |

|

|

Trade, Transportation, and Utilities |

14% |

43% |

|

|

Information |

46% |

77% |

|

|

Financial Activities |

30% |

66% |

|

|

Professional and Technical Services |

34% |

57% |

|

|

Administrative and Waste Services |

6% |

19% |

|

|

Education and Health Services |

23% |

39% |

|

|

Leisure and Hospitality |

11% |

20% |

|

|

Other Services |

11% |

27% |

|

|

By Average Occupational-Wage Distribution |

|||

|

Bottom 25% |

8% |

18% |

|

|

Second 25% |

17% |

42% |

|

|

Third 25% |

20% |

53% |

|

|

Top 25% |

30% |

63% |

|

|

By Hours of Work Status |

|||

|

Full-time |

21% |

51% |

|

|

Part-time |

8% |

17% |

|

|

By Establishment Size |

|||

|

1 to 99 employees |

14% |

32% |

|

|

100 to 499 employees |

18% |

48% |

|

|

500 or more employees |

29% |

64% |

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2019 Employee Benefits Survey, September 2019, Table 16 (insurance) and Table 31 (paid leave).

Notes: The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave "granted to an employee to care for a family member and includes paid maternity and paternity leave. The leave may be available to care for a newborn child, an adopted child, a sick child, or a sick adult relative. Paid family leave is given in addition to any sick leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee."” The BLS survey defines short-term disability plans as those that "“provide benefits for non-work-related illnessesil nesses or accidents on a per-disability basis, typically for a 6-month to 12-month period. Benefits are paid as a percentage of employee earnings or as a flat dollardol ar amount. Short-term disability insurance (STDI) benefits vary with the amount of predisabilitypre-disability earnings, length of service with the establishment, or length of disability."” An employer that makes a full ful or partial payment towards a STDI plan is considered by BLS to provide employer-supported STDI . If there is no employer contribution to the plan (i.e., if it is entirely employee-financed), then such an insurance plan is not considered to be employer-supported STDI. Employees may also be able to use other forms of paid leave not shown in this table (e.g., vacation time), or a combination of them, to provide care to a family member or for their own medical needs.

Congressional Research Service

6

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

A 2017 study by the Pew Research Center (Pew) examined U.S. perceptions of and experiences with paid family and medical leave and provides insights into the need for such leave among U.S. workers and its availability for those who need it.1719 Pew reports, for example, that 27% of persons who were employed for pay between November 2014 and November 2016 took leave (paid and unpaid) for family caregiving reasons or their own serious health condition over that time period, and another 16% had a need for such leave but were not able to take it.1820 Among workers who were able to use leave, 47% received full pay, 36% received no pay, and 16% received partial pay. Consistent with BLS data, the Pew study indicates that lower-paid workers have less access to paid leave; among leave takers, 62% of workers in households with less than $30,000 in total annual earnings reported they received no pay during leave, whereas this figure was 26% among those with total annual household incomes at or above $75,000.

The Pew survey reveals differences in access to family and medical leave across demographic groups. For example, 26% of blackBlack workers and 23% of Hispanic workers indicated that there was a time in the two years before the interview they needed or wanted time off (paid or unpaid) for family or medical reasons and were not able to take it; by contrast 13% of whiteWhite workers reported they were unable to take such leave. Relatedly, among those who did take leave, Hispanic leave-takers were more likely than black or whiteBlack or White workers to report they took leave with no pay.19

21

State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Short-TermTemporary Disability Insurance Programs

Some states have enacted legislation to create state leave insurance programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who to take time away from work to engage in certain caregiving activities and for qualifying healthmedical reasons. As of May 2022, eight states (including the District of Columbia [DC])—California, Connecticut, DC, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode

19 Juliana Horowitz, Kim Parker, Nikki Graf, and Gretchen Livingston, Americans Widely Support Paid Family and Medical Leave, but Differ Over Specific Policies, Pew Research Center, March 2017, http://pewresearch.org; hereinafter “Horowitz et al., 2017.” Pew’s findings are based on two large-scale, nationally representative surveys. The first survey collected data from the general population, and is used to measure U.S. attitudes toward and perceptions of paid family leave, as well as the availability of leave for those who had a recent (i.e., within the last two years) need for family or medical leave. The second survey collected information from individuals who had a recent need for family or medical leave, and is used to study leave-taking in detail (e.g., economic and demographic characteristics of workers who were able and unable to meet their needs for leave, reasons the workers needed leave, duration of leave when taken, and the percentage of pay provided to those who were able to take leave).

20 These survey results are summarized on page 52 of Horowitz et al., 2017. For workers who took family and medical leave and those who had such a need but were unable to take leave, the areas of greatest demand were for leave to care for the worker’s own serious health condition and for leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition. The survey questionnaire defines a serious health condition as “a condition or illness that lasted at least a week and required treatment by a health care provider … required an overnight hospital stay … [or] was long-lasting, requiring treatment by a health care provider at least twice a year.” See https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/dataset/family-and-medical-leave-study/.

21 This finding is consistent with research by Ann Bartel et al., (2019), who also find that “Hispanic workers have lower rates of paid-leave access and use than their White non-Hispanic counterparts.” Ann Bartel, Soohyn Kim, Jaehyun Nam, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel, “Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: evidence from four nationally representative datasets,” Monthly Labor Review, January 2019, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2019/article/pdf/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-access-to-and-use-of-paid-family-and-medical-leave.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 12 link to page 15 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 5

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Island, and reasons (Table 2). As of February 2020, five states—California, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington—have active programs.22 Four additional programs—those in Connecticut, the District of Columbia (DC), Massachusetts, and Oregon—await implementation.20

Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, and Oregon—await implementation.23

In May 2022, total benefits available in a benefit year (typically a 12-month period) under the state leave insurance program to eligible claimants ranged from 8 to 52 (Figure 1). Selected information on state leave insurance benefits is displayed in Figure 2 and Table A-1 provides a summary of key provisions of state leave insurance laws.

Figure 1. Weeks of Total Benefits Available in a Benefit Year under State Leave

Insurance Programs, May 2022

Source: CRS based on information in Table A-1 on state leave insurance laws. Notes: The figure provides total weeks of benefits available in a benefit year (typically a 12-month period) to eligible claimants covered by a state leave insurance program. In some cases, states limit the number of weeks that may be claimed during a benefit year for particular family or medical leave events, and those limits may be less than the total amount shown in this figure. For example California limits claims for family leave events to 8 weeks in a benefit year. Benefits are subject to eligibility conditions, and are calculated using state-specific benefit formulae. Some states provide additional weeks of benefits if certain conditions are met.

The first four states to offer family leave insurance (FLI)—California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—did so by building upon existing state STDI temporary disability insurance (TDI) programs (i.e., that provide benefits to workers absence from work due to significant health a significant medical condition).24 As a result, these programs tend to offer separate entitlements to FLI benefits and STDITDI benefits. (To simplify the discussion, the terms STDITDI and medical leave insurance (MLI) benefits are used interchangeably in this section.2125) For example, eligible California workers may

22 Hawaii and Puerto Rico require employers to provide short-term disability insurance but not family leave insurance to their employees, and as such are not included in this discussion. New Hampshire is to allow private sector employers with more than 50 employees and certain individuals to opt in to its leave insurance program for state employees. Because participation is voluntary for all private sector employers, the program is not included in this discussion. See footnote 4 for more information on the NH program.

23 Benefit payments for the Oregon program are to start in September 2023; benefits payments for the Colorado program are to start in January 2024; benefits for the Maryland program are to start in January 2025; and benefits for the Delaware program are to start in January 2026.

24 California was the first state to provide family leave insurance (FLI) benefits; the program took effect (FLI benefits became payable) on July 1, 2004. FLI benefits became payable in New Jersey on July 1, 2009, in Rhode Island on January 1, 2014, and in New York on January 1, 2018.

25 Whereas these four states provide for TDI benefits for serious health-related absences, the newer programs use the term medical leave insurance benefits. Broadly speaking, the terms temporary disability absence and medical leave both describe a workplace absence due to a significant health condition that prevents a worker from performing his or her regular work duties. Definitions vary from state to state, but they are broadly similar. These types of leave differ from sick leave, which can be used for more minor ailments and for routine medical care. In addition, paid sick leave tends to be compensated at regular rates of pay, whereas state TDI and MLI benefits are generally paid at less than the

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 33 link to page 8 link to page 12 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

) For example, eligible California workers may take up to 52 weeks of MLI and up to 68 weeks FLI. By contrast, newer programs tend to offer a total amount of annual benefit weeks to workers, who may allocate them across the various needs categories (e.g., caregiving needs, medical needs) with some states capping the maximum amount that can be allocated to a single category. For example, Washington provides a total of 16 benefit weeks per year that may be used for a variety of family or medical needs, but limits FLI claims to 12 weeks and MLI claims to 12 weeks.26 All states included in Table A-1weeks per year, of which up to 12 weeks of benefits may be claimed for FLI, and up to 12 weeks of benefits for MLI.22 All states included in Table 2 offer (or will offer) FLI benefits through their programs to eligible individuals who take leave from work for the arrival of a new child by birth or placement, and to care for close family members with a serious health condition; some states provide family leave insurance in other circumstances.23

Table 2 summarizes key provisions of state leave insurance laws, and shows the following:24

- 27

Table A-1 shows the following:28

Benefit Duration: The maximum weeks of insurance benefits available to

workers vary across states.

ExistingLonger-running state programs offer between 26 weeks (New York) and 52 weeks (California) in20202022, but most weeks of benefits are set aside for MLI in these states.States that will implementNewer programs (i.e., those that implemented their programs inJuly2020 or later) tend to offer fewer total weeks of benefits—the rangewill beis 8 total (DC) to 25 total (Massachusetts), but generally allow workers to take more weeks of FLI benefits than do existing programs. Benefit Amount: Weekly benefits amounts in existing programs vary around 60-70% of the employee's average weekly earnings, with some exceptions,; generally this is because newer programs offer fewer weeks of medical leave than longer-running programs. Benefit Amount: Weekly benefits amounts range from 50% to 100% of an employee’s average weekly earnings and all states cap benefits at a maximum weekly amount ($170 per week for MLI benefits in New York to $1,540 per week for FLI or MLI benefits in California)weekly amount. Most states with leave insurance programs have or plan to have a progressive benefit formula.- Eligibility: Program eligibility typically involves in-state employment of a minimum duration, minimum earnings in covered employment, or contributions to the insurance funds.

- Delaware’s program further conditions benefit eligibility on a worker’s tenure with the current employer.

Financing: All programs are financed through payroll taxes, with some variation

in how taxes are allocated between employers and employees.

Some state leave insurance programs provide job protection directly to workers who receive insurance benefits, meaning that employers must allow such a worker to return to her or his job after leave (for which the employee has claimed insurance benefits) has ended. For example, Oregon is to provide job protection to leave insurance claimants who worked at least 90 days with their current employer before taking leave. Workers may otherwise receive job protection if they are entitled to leave under (the federal) FMLA or state family and medical leave laws, and coordinate such job-protected leave with the receipt of state insurance benefits. (See Table A-2 for a summary of relevant state laws). For example, job protection does not accompany leave

worker’s regular rate of pay (an exception is lower wage workers in Oregon). A waiting period is often required before the payment of TDI or MLI benefits; such a waiting period is generally not required for sick leave pay. Finally, paid sick leave benefits are generally available for shorter total durations than TDI or MLI benefits, see footnote 15 for additional discussion.

26 Washington provides 2 additional weeks of benefits for a serious health condition if an employee’s pregnancy results in incapacitation, raising the limit on MLI benefits to 14 weeks and bringing total benefits to 18 weeks in such cases.

27 For example, some states provide family leave insurance for certain military family needs, for time away from work to address needs related to sexual or domestic violence (i.e., safe leave).

28 For reasons noted in footnote 22, Hawaii, New Hampshire, and Puerto Rico are not included in the table.

Congressional Research Service

9

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

insurance benefits in California. However, California employees claiming FLI benefits may be eligible for job protection under the FMLA (federal protections) or the California Family Rights Act; California workers claiming MLI for pregnancy or childbirth-related disabilities may be eligible for job protection under FMLA or the California Fair Employment and Housing Act. A California worker otherwise claiming benefits for a serious health condition that makes her or him unable to perform his or her job functions may be eligible for job protection under FMLA for up to 12 weeks.29

29 Although California workers may qualify for up to 52 weeks of temporary disability insurance under the state program, FMLA provides only 12 weeks of job-protected leave (for workers meeting eligibility conditions).

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 24

Figure 2. State Leave Insurance Programs, Selected Benefit Information as of May 2022

Source: CRS, based on information in Table A-1 on state leave insurance laws. Notes: This graphic summarizes program information for states that provide for a family leave insurance benefit. “FLI” indicates family leave insurance, “MLI” indicates medical leave insurance, and “TDI” indicates temporary disability insurance. “Total” weeks of benefits indicates the maximum number of combined benefit weeks available in a state benefit period (generally a 12-month period). Where states limit the category of leave insurance benefits (e.g., FLI, MLI) that may be counted toward that total, these limits are noted in parentheses. Benefit durations for the DC program are scheduled to increase in 2022.

CRS-11

link to page 11 link to page 11 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Research on Paid Family and Medical Leave A relatively small literature examines relationships between U.S. workers’ access to and use of paid family and medical leave and related labor market and social outcomes. Much of this research emphasizes experiences and outcomes related to parental leave (i.e., leave related to the birth and care of new children), which is a subset of the broader family caregiving category. The focus on parental leave is driven in part by data availability, as the arrival of a new child is somewhat easier to observe in large-scale survey data than other family and medical events.30 Parental leave—and maternity leave in particular—is also a more prevalent and better understood workplace benefit than family caregiving or medical leave. For this reason survey respondents may be more likely to identify a reported workplace absence as maternity or paternity leave than they are to specify their use of medical leave or caregiving leave with great precision.31

Survey data generally allow a period of leave to be observed (and therefore studied) if the worker is taking leave at the time of the interview, or if the survey asks for information on past leave-taking. That is, information on leave is generally available conditional on the worker’s use of such leave. Some workers may have access to workplace leave, but not take it for a variety of reasons. Information on workplace access to paid family and medical leave, including parental leave, in survey data is comparatively scarce, as are details of parental leave benefits (e.g., duration, eligibility conditions, and wage replacement) offered by employers.32 For these reasons studies of the state leave insurance programs (see the “State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Temporary Disability Insurance Programs” section of this report) form an important branch of research on U.S. workers. The parameters of these programs are clearly established in state laws. In addition, the broad coverage of these programs and, in some cases, the availability of

30 Many household surveys ask participants directly about births or researchers can infer the arrival of a new child in the demographic information collected from family members; for example, from birth dates or new names added to the family rosters. By contrast, detailed information on the incidence, timing, duration, and severity of a medical condition or family caregiving arrangement, as defined in federal policy or proposals, is less visible outside of surveys designed to collect those particular data; for example, the National Study of Caregiving (NCOS) collects information on caregiving as well as labor earnings, health status, and to some extent workplace leave. A helpful discussion of data availability and the limitations of commonly-used surveys is in Amy Batchelor, Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States: A Data Agenda, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, March 2019, https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/030719-paid-leave-data-report-1.pdf.

31 For example the Current Population Survey (CPS) asks a worker who reports that she or he is absent from work during the survey reference week to indicate the main reason for the absence. “Maternity/Paternity leave” is among the 14 options (including “other”) provided to the respondent to characterize the main reason for the absence, which allows for a parental leave absence to be observed. The survey also asks if the worker is being paid by her or his employer during the time off, allowing for the leave to be characterized as paid or unpaid. Respondents who are away from work for needs related to a serious health condition could select the response “own illness/injury/medical problems” but this category would also capture those on leave for minor issues or preventive care. Similarly, a worker who takes leave to care for seriously ill close family member could indicate the leave was for “other family/personal obligation[s],” but again this category would include a range of family and personal needs that are not strictly considered to be family leave. See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/questionnaires.html.

32 Some researchers have worked to fill gaps in this area by collecting their own data. For example Claudia Goldin, Sari Pekkala Kerr, and Claudia Olivetti compiled data on a sample of private sector firms (1,135 firms) from multiple sources, including through direct contact with some firms, to learn the details of employers’ paid parental leave policies. They describe these policies as complex and sometimes opaque: “Firms do not always clearly state whether their short-term (or temporary) disability program is included in the number of [paid parental leave (PPL)] weeks they claim to offer and whether workers who take PPL are first required to exhaust their vacation, and sick days. Even more difficult is figuring whether all workers at the firm are covered.” Claudia Goldin, Sari Pekkala Kerr, and Claudia Olivetti, Why Firms Offer Paid Parental Leave: an Exploratory Study, NBER Working Paper 26617, January 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26617.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 7 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

administrative data provide methodological advantages over studies of workers with employer-provided leave.33

Research on Paid Parental Leave in California

In 2004, California was the first state to launch a family leave insurance program, building upon its existing temporary disability insurance program, and currently is the most studied.34 Research findings indicate that greater access to paid family leave (i.e., through the California program) resulted in greater leave-taking among workers with new children, with some evidence that the increase in leave-taking was particularly pronounced among women who are less educated, unmarried, or nonwhite.35 Although the program has been associated with greater leave-taking—in terms of incidence and duration of leave—for mothers and fathers, there is some indication that some workers are not availing themselves of the full six-week entitlement offered by the California program, suggesting that barriers to leave-taking remain (e.g., financial constraints, work pressures, concerns about employer retaliation).36 One study observes that employer characteristics appear to matter to workers’ use of the California leave insurance benefits, raising the possibility that workplace culture plays a role in workers’ leave-taking decisions.37

Some studies of the California program have considered the relationship between paid parental leave and parents’ (mothers especially) attachment to the labor market. In theory, the availability of such a benefit may encourage parents to stay in work prior to the birth or arrival of a child (e.g., to qualify for benefits) and, because a full separation has not occurred, facilitate the return to work. Further, if the job held prior to leave sufficiently accommodates the needs of a working parent of a young child (e.g., if work hours align with traditional child care facility hours), a parent may be more likely to return to his or her same employer, which can benefit both the

33 As noted in the “Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave” section of this report, employer-provided leave is concentrated among higher-paying occupations, larger firms, and certain industries. This lack of broad coverage creates challenges for researchers trying to disentangle, for example, the effects of leave-taking on employment and earnings outcomes from the effects of holding a high-paying professional job on the same outcomes. On the other hand, broad program coverage can complicate the identification of a meaningful comparison group in studies that seek to contrast outcomes for workers with access to paid leave to those otherwise similar workers without access to paid leave.

34 A smaller body of research studies has considered the social and economic effects of state leave insurance program in New Jersey and Rhode Island. For example, Tanya Byker examines the impacts of state leave insurance in California and New Jersey on mothers’ labor force attachment. Tanya Byker, “Paid Parental Leave Laws in the United States: Does Short-Duration Leave Affect Women’s Labor-Force Attachment?” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, vol. 106, no. 5 (2016), pp. 242-246 hereinafter “Byker, 2016.” It is worth noting that the California legislature has amended the program several times since it took effect in 2004—for example, in 2018 the state changed the benefit formula from a flat 55% of usual wages to a progressive formula that replaces 60%-70% of usual wages—and for this reason the findings of earlier studies may not hold for the current program. This change was made by California Assembly Bill No. 908, which was signed into law on April 11, 2016; see https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB908.

35 Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel, “The Effect of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 32, no. 2 (2013), pp. 224-245.

36 Charles Baum and Christopher Ruhm, The Effects of Paid Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes, NBER Working Paper 19741, 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19741; Ann Bartel, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, Jenna Stearns, and Jane Waldfogel, Paid Family Leave, Fathers’ Leave-Taking, and Leave-Sharing in Dual-Earner Households, NBER Working Paper no. 21747, 2015, http://www.nber.org/papers/w21747.

37 In particular, program claims are higher among workers employed in higher-paying firms; this relationship is particularly strong among lower-paid workers in such firms. See Sarah Bana, Kelly Bedard, Maya Rossin-Slater, and Jenna Stearns, Unequal Use of Social Insurance Benefits: The Role of Employers, NBER Working Paper no. 25163, October 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w25163.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 20 link to page 20 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

worker (e.g., who avoids costly job search, and the loss of job-specific skills and benefits of company tenure) and employers (e.g., who avoid the costs of finding a replacement worker). Empirical findings are mixed, with some studies observing a positive relationship between paid parental leave and mothers’ labor force attachment, and others finding little evidence of such a connection.38 Another branch of research examines linkages between paid parental leave and family well-being. These generally find positive relationships along a variety of measures (e.g., timing of children’s immunizations, mothers’ mental health, and breastfeeding duration).39

Economist Maya Rossin-Slater reviews the broader literature on the impacts of maternity and paid parental leave in the United States, Europe, and other high-income countries.40 She notes the wide variation in paid leave policies across countries (see “Family and Medical Leave Benefits in OECD Countries” section of this report), but nonetheless offers four general observations: (1) greater access to paid leave for new parents increases leave-taking; (2) access to leave can improve labor force attachment among new mothers, but leave entitlements in excess of one year can have the opposite effect (i.e., long separations can weaken labor force attachment among mothers); (3) access to leave can improve children’s well-being, but extending the length of existing entitlements does not appear to further improve child outcomes; and (4) a limited literature on U.S. state-level leave insurance programs does not reveal notable impacts (positive or negative) of these programs on employers, but further research on employers’ experiences is needed.

Research on Paid Family Caregiving and Medical Leave

A smaller but growing number of studies examine the social and economic impacts of paid family caregiving leave more generally (i.e., to care for a seriously ill or injured family member) or paid medical leave, despite the prevalence of such leave among U.S. workers.41 In addition to data

38 A summary of earlier studies’ findings for labor market outcomes is in Maya Rossin-Slater, “Maternity and Family Leave Policy,” in The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, ed. Susan L. Averett, Laura M. Argys, and Saul D. Hoffman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); hereinafter “Rossin-Slater 2018.” More recently, Tanya Byker finds a positive association between state leave insurance benefits in California and New Jersey and women’s labor force attachment in the months before and after a birth; see Byker, 2016. By contrast, one study considered the labor market outcomes of first-time mothers who claimed California’s paid family leave insurance benefits just as the program launched (i.e., in the months around July 2004). The results indicate a decrease in employment and earnings for this group in both the short-run (1-5 years later) and long-run (6-11 years later). See Martha Bailey, Tanya Byker, Elena Patel, and Shanthi Ramnath, The Long-Term Effects of California’s 2004 Paid Family Leave Act on Women’s Careers: Evidence from U.S. Tax Data, NBER Working Paper no. 26416, October 2019, http://www.nber.org/papers/w26416.

39 For example, Choudhury and Polacek found that the rate of late infant immunizations fell by about five percentage points for children born in California after the implementation of the California Paid Family Leave Program in 2004. Improvements in on-time immunization rates were greater for poor children relative to non-poor children. See Agnitra Roy Choudhury and Solomon Polachek, The Impact of Paid Family Leave on the Timing of Infant Vaccinations, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12483, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, 2019. Another team of researchers observed positive relationships between the implementation of the California program and breastfeeding duration, with larger effects for some disadvantaged mothers (e.g., mothers with less than a high school education, mothers with family incomes below the federal poverty line). See Jessica E. Pac, Ann P. Bartel, Christopher J. Ruhm, Jane Waldfogel, Paid Family Leave and Breastfeeding: Evidence from California, NBER Working Paper No. 25784, Issued in April 2019.

40 Rossin-Slater 2018. 41 Among workers reporting they took leave for an FMLA-qualifying reasons (even if they were not eligible for FMLA-protected leave) in 2018, most (50.5%) reported that leave was taken for the worker’s own illness; about 18.6% reported leave to care for a child, spouse, or parent with a serious medical need (and other 5.3% report taking leave to care for a non-FMLA covered individual). Scott Brown, Jane Herr, Radha Roy, and Jacob Alex Klerman, Employee and Worksite Perspectives of the Family and Medical Leave Act: Supplemental Results from the 2018 Surveys, Appendix Exhibit B4-3, Abt Associates Inc. (Prepared for the Dept. of Labor), July 2020, https://www.dol.gov/

Congressional Research Service

14

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

availability issues noted earlier in this section, the wide variety of needs encompassed by these types of leave create methodological hurdles. For example, the impacts of medical leave (or caregiving leave) for workers and for their employers may differ if leave is used rarely (e.g., to recover from a one-off surgical procedure) than for a chronic ailment. Medical leave needs can also vary in terms of duration, further complicating efforts to establish generalizable findings.

Nonetheless, the introduction of broad-coverage state leave insurance programs creates the potential for additional research in these areas. For example, one recent study asks whether greater access to paid caregiving leave through the California and New Jersey state programs helped workers remain attached to the labor market when their spouse became disabled or otherwise experienced a serious health shock. They find some evidence that access to paid caregiving leave reduces the likelihood that such workers decrease their work hours due to providing care, but did not find similar effects for other measures of labor supply (such as employment or full-time status). They suggest that the lack of broader labor supply impacts may be influenced by the relatively short period of caregiving leave (6 weeks in each state during the study time period), which may be insufficient in some cases (e.g., severe chronic illness or extended recovery periods), or because caregivers were unaware that the state programs offer benefits for spousal care. Lack of program awareness was identified in another study of the California and New Jersey programs as a potential reason that the programs had not been associated with an increase in leave taking among those likely to provide elder care.42 The study also considered that the structure of the state leave insurance benefits (e.g., definition of caregiving, timing and duration of leave, employer notice requirements, lack of job protection) do not meet the needs of caregivers in those states.

Some studies examine employers’ experiences with the increased access to paid leave through the state programs. One study compares employer outcomes in New York, following the state’s adoption of a family leave insurance program, to those of similar employers in Pennsylvania, a neighboring state that does not have a leave insurance program.43 The study focused on employers with 10-99 employees. They found that in the first year of implementation, employers with 50-99 employees reported an increase in the ease of dealing with employee absences (statistically significant results were not observed for employers with 10-49 employees). At the same time, however, they found that the albeit-small share of employers who report opposition to the state program has increased from 4.1% in 2016 to 9.5%.44 (A subsequent study by the same research team found that employers’ support for state programs increased during the COVID-19 pandemic).45 Another study looked at the relationship between the establishment of state programs and firm-level performance (as measured by firms’ return on assets and other financial

agencies/oasp/evaluation/fmla2018.

42 See Brant Morefield, Abby Hoffman, Jeremy Bray, and Nicholas Byrd, Leaving it to the Family: the Effects of Paid Leave on Adult Child Caregivers, L&M Policy Research (Prepared for the Dept. of Labor), July 2016, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/Paid_Leave_Leaving_it_to_the_family_Report.pdf.

43 The research team collected information from employers in both states before and after the implementation of the New York program, allowing them to assess how the new policy may have changed employer views and outcomes. Ann P. Bartel, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Meredith Slopen, and Jane Waldfogel, The Impact of Paid Family Leave on Employers: Evidence from New York, NBER Working Paper 28672, April 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w28672.

44 The authors note that opposition appears pronounced among smaller employers. 45 The research team re-contacted as many employers from the original study sample as possible. Ann P. Bartel, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, Meredith Slopen, and Jane Waldfogel, Support for Paid Family Leave among Small Employers Increases during the COVID-19 Pandemic, NBER Working Paper 29486, December 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29486.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 21 Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

measures).46 It found evidence of improved firm-level performance after the establishment of state programs for firms headquartered in states with leave insurance laws; the study’s authors attribute improvements to greater employee retention and the nomination of women to executive positions.47

Some additional insights to the potential impacts of paid medical leave, as defined in federal proposals, can be gained from research on the social and economic impacts of paid sick leave.48 For example, one study found that access to paid sick leave is associated with lower (involuntary) job separation rates.49 By extension, one might speculate that access to paid medical leave may have similar impacts on job stability. Some caution is warranted however, in directly applying the results of paid sick leave studies to medical leave. Research on paid sick leave will likely capture the impacts of relatively short period of leave (e.g., less than one week), as well as the effects of preventive care and absences for minor illness and injury. Paid medical leave, by definition, does not include preventive care, and tends to allow for several weeks of leave.