Kosovo: Background and U.S. Policy

Changes from February 11, 2020 to May 5, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Kosovo: In Brief

Background and U.S. Policy

Contents

- Overview

- Domestic Issues

- Politics

- Kosovo Serbs and Northern Kosovo

- Economy

- Relations with Serbia

- War and Independence

- European Union-Facilitated Dialogue

: Status and Prospects - Transitional Justice

- Relations with the EU and NATO

- European Union

- NATO

- U.S.-Kosovo Relations

- Financial Assistance

- Cooperation on Transnational Threats and Security Issues

- Congressional Engagement

Summary

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008, and it has since been recognized by over, a country in the Western Balkans with a predominantly Albanian-speaking population, declared independence from Serbia in 2008, less than a decade after a brief but lethal war. It has since been recognized by about 100 countries. The United States and most European Union (EU) member states recognize Kosovo, whereas. Serbia, Russia, China, and various other countries (including some EU countriesmember states) do not.

Key issues for Kosovo include the following:

- New government. Nearly four months after early parliamentary elections, Kosovo formed a government on February 3, 2020. The new governing coalition, led by Prime Minister Albin Kurti of the Self-Determination Party (Vetëvendosje), comprises parties that were previously in opposition. The government has pledged to tackle problems with socioeconomic conditions and rule of law concerns; its approach to normalizing relations with Serbia remains to be seen.

- Resuming talks with Serbia. An EU-brokered dialogue to normalize relations between Kosovo and Serbia stalled in 2018 when Kosovo imposed tariffs on Serbian goods in response to Serbia's efforts to undermine Kosovo's international recognition. Despite U.S. and EU pressure, the parties have not resumed talks.

Strengthening the rule of law.The victory of Prime Minister Kurti's Vetëvendosje in the 2019 election is considered to partly reflectResuming talks with Serbia. An EU-facilitated dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia, aimed at normalization of relations, stalled in 2018 when Kosovo imposed tariffs on Serbian goods in response to Serbia's efforts to undermine Kosovo's international legitimacy. Despite U.S. and EU pressure, the parties have not resumed talks. On April 1, 2020, acting Prime Minister Albin Kurti conditionally lifted tariffs against Serbian imports; this step was praised by EU officials but drew U.S. criticism because of the government's simultaneous pledge to gradually introduce measures to match Serbian barriers to the movement of goods and people.- Government collapse. The governing coalition led by Albin Kurti of the Self-Determination Party (Vetëvendosje) lost a vote of confidence in March 2020, less than two months after it had formed. The outgoing government comprises two parties formerly in opposition, both of which had campaigned on an anti-corruption platform. Among other factors, the collapse was attributed to divisions over managing relations with Serbia amid U.S. pressure on the government to immediately lift tariffs against Serbian imports, as well as to domestic political infighting. Kosovo's leaders disagree over how to proceed from the current political crisis.

Strengthening the rule of law. The victory of Kurti's Vetëvendosje in the October 2019 election partly reflected widespread voter dissatisfaction with corruption. Weakness in the rule of law contributes to Kosovo's difficulties in attracting foreign investment and complicates the country's efforts to combat transnational threats.- Relations with the United States. Kosovo regards the United States as a key ally and security guarantor. Kosovo receives the largest share of U.S. foreign assistance to the Balkans, and the two countries cooperate on numerous security issues. The United States is the largest contributor of troops to the NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR), which has contributed to security in Kosovo since 1999. In 2019, the Trump Administration appointed a Special Representative for the Western Balkans and a Special Presidential Envoy for Serbia and Kosovo Peace Negotiations. These appointments are considered to reflect

renewed U.S. engagement in the region,the Administration's interest inexpeditiously reaching an agreementsecuring a comprehensive settlement between Kosovo and Serbia, andand may signal a potentially greater U.S. role in a process that the EU has largely facilitated to date. Leaders in Kosovo generally have welcomed greater U.S. engagement, but some observers expressed concern over reported U.S. pressure on the Kurti government to lift tariffs on Serbian goods—including pausing some U.S. assistance to Kosovo—and over perceived U.S. support for the no-confidence session that resulted in the March 2020 government collapse. U.S. officials maintain that the United States is committed to working with any government formed in compliance with constitutional processes.- Transatlantic cooperation. Since the Kosovo war ended in 1999, the United States, the EU, and key EU member states have largely coordinated their efforts to promote regional stability in the Western Balkans, including efforts to normalize relations between Kosovo and Serbia. More recently, however, some observers have expressed concern that transatlantic coordination has weakened on some issues relating to the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue and to Kosovo's current political impasse.

a potentially greater U.S. role in a process that the EU has largely facilitated to date.

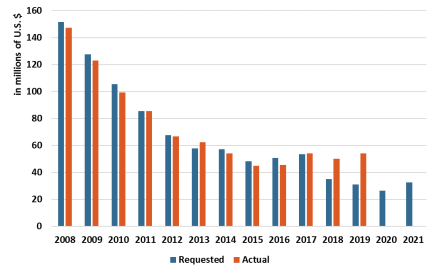

Congress was actively involved in debates over the U.S. response to a 1998-1999 conflict in Kosovo and subsequently supported Kosovo's declaration of independence. Today, many inMembers of Congress continue to support Kosovo through country- or region-specific hearings, congressional visits, and foreign assistance funding levels averaging around $50 million per year since 2015.

Overview

|

Kosovo at a Glance Capital: Pristina Population: 1.82 million (2019 est.) Ethnic Groups: Albanian (92.9%), Bosniak (1.6%), Serb (1.5%) Languages: Albanian (94.5%), Bosnian (1.7%), Serbian (1.6%), Turkish (1.1%) Religions: Muslim (95.6%), Catholic (2.2%), Orthodox Christian (1.5%) Leadership: Acting Prime Minister Albin Kurti (since Sources: CIA World Factbook; International Monetary Fund; 2011 Kosovo Census. Note: Population share for ethnic Serbs, Serbian language, and Orthodox Christians is likely closer to 5%-9%. Serbs largely boycotted the 2011 census. |

The Republic of Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008, nearly a decade after the end of a brief but lethal conflict between Serbian forces and a Kosovo Albanian insurgency led by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). Since 2008, Kosovo has been recognized by more than 100 countries. The United States and most European Union (EU) member states recognize Kosovo, whereas. Serbia, Russia, China, and various other countries (including some EU member states) do not. The United States has strongly supported Kosovo's state-building and development efforts, as well as its ongoing dialogue with Serbia to normalize their relations.

Congress has maintained interest in Kosovo for many decades—from concerns over Serbia's treatment of ethnic Albanians in the former Yugoslavia to the armed conflict in Kosovo in 1998-1999 after the Yugoslav federation disintegrated. Many Members were active in debates over the U.S.- and NATO-led military intervention in the conflict. After Serbian forces withdrew in 1999, many Members backed Kosovo's independence. Today, many in Congress continue to support Kosovo through country- or region-specific hearings, congressional visits, and foreign assistance funding levels averaging around $50 million per year since 2015.

Looking ahead, Members may consider how the United States can support the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, Kosovo's Euro-Atlantic ambitions, transitional justice processes, and regional security. U.S. support for the rule of law and reform may be particularly significant in light of growing uncertainty over the Western Balkan countries' prospects for EU membershipthe ongoing political crisis arising from the March 2020 government collapse, and regional security.

Domestic Issues

KeyCurrent key issues in Kosovo's domestic situation include the formation of a new government in February 2020;March 2020 collapse of the government; responding to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic; managing relations with the country's ethnic Serb minority, particularly in northern Kosovo; and economic growth and job creation.

Politics

Kosovo is a parliamentary republic with a prime minister, who serves as head of government, and an indirectly elected president, who serves as head of state and has largely ceremonial powers. The unicameral National Assembly has 120 seats, of which 20 are reserved for ethnic minorities. Albin Kurti currently serves as acting Prime Minister. In 2016, the National Assembly elected Hashim Thaçi to a five-year term as president. Thaçi previously served as prime minister and has long been a major political figure in the country.

Kosovo's domestic politics have been volatile for much of the past year, marked by government turnover, escalating tension between the president and prime minister, and divisions over various issues—including a stalled dialogue to normalize relations with Serbia. More recently, the country entered a period of uncertainty when the Kurti government lost a vote of confidence on March 25, 2020, less than two months after it had formed (see textbox below, "March 2020 Government Collapse and Aftermath"). Many had viewed that government as a potentially pivotal shift in power from long-ruling parties to the opposition. The government breakdown coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, and some have expressed concern that the ensuing political crisis could impede the public health response. Party Vote (%) Seats (#) Vetevëndosje 26.27 29 Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) 24.55 28 Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) 21.23 24 Coalition led by Alliance for the Future of Kosovo 11.52 13 Serbian List 6.4 10 Coalition led by Social Democratic Initiative 5.0 6 Other 5.0 10 Total 100% 120 seats Source: Republic of Kosovo Electoral Commission.

. The unicameral National Assembly has 120 seats, of which 20 are reserved for ethnic minorities, including 10 for ethnic Serbs. Prime Minister Albin Kurti leads the current government. In 2016, the National Assembly elected Hashim Thaçi, previously prime minister from 2008 to 2014, to a five-year term as president.

On February 3, 2020, the National Assembly approved a new government under Albin Kurti, marking the end of nearly eight months of political uncertainty. In July 2019, then-Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj received summons to a special war crimes court (see "Transitional Justice," below) and announced his resignation. Kosovo held early parliamentary elections on October 6, 2019. Kurti, leader of the left-wing Self-Determination Party (Vetëvendosje), appeared poised to quickly form a government with the center-right Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK); the two parties combined received just over 50% of votes (see Table 1). After protracted negotiations, in the two parties agreed to the current Kurti government in February 2020. One-third of ministers in the government are women, an unprecedented share in independent Kosovo. Vjosa Osmani, who was the LDK's prime minister candidate in the October 2019 election, became Speaker of Parliament and is the first woman to hold this position.1

The victory of Vetëvendosje and the LDK, both of which were previously in opposition, is considered to reflect deep voter dissatisfaction with corruption and economic conditions, as well as a desire to hold accountable the small number of parties that have largely rotated in government over the past several decades. Prior to the 2019 election considered to reflect deep voter dissatisfaction with corruption and economic conditions, as well as a desire to hold accountable the small number of parties that have largely rotated in government over the past several decades.1 Prior to 2020, the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK), led by Thaçi until 2016, had participated in all governments since independence. The PDK and Haradinaj's Alliance for the Future of Kosovoseveral other former ruling parties grew out of factions of the KLA resistance and, along with several other parties, sometimes are referred to as the war wing. Critics charge that these parties became entrenched in state institutions.2

By contrast, neither Vetëvendosje nor its leader, Albin Kurti, had been in national government prior to 2020. The party grew out of a 2000s-era protest movement that channeled popular frustration with government corruption. Vetëvendosje also railed against aspects of post-1999 international administration of Kosovo, accusing international missions of failing to establish the rule of law despite their vast powers. The party has steadily built support across election cycles.3 In the past, Vetëvendosje was criticized for using obstructionist tactics, (including releasing tear gas in parliament. Longtime Vetëvendosje leader) and for seeking to subvert several agreements with Serbia and Montenegro that were seen as important to regional reconciliation. Kurti maintains that the party will govern responsibly and prioritize socioeconomic reforms and the rule of law. Vetëvendosje at times has floated the idea of eventual unification with Kosovo's neighbor and close ally, Albania; however, this issueunification does not appear likely to become a serious proposal to be a priority for Vetëvendosje or to be likely under current conditions, not least of all due to U.S. and EU objections.4

March 2020 Government Collapse and Aftermath Less than two months after Vetëvendosje and the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) formed a governing coalition, LDK triggered a vote of no confidence that passed on March 25, 2020. Analysts largely attributed the government breakdown to political infighting and divisions over how to respond to reported U.S. pressure on Kurti to immediately and unconditionally lift tariffs against Serbia. (Kurti remained opposed to unconditionally lifting tariffs, whereas LDK's leader expressed concern that not doing so could damage relations with the United States.) The United States, which indicated support for the no-confidence session, took a different position from that of France and Germany, which issued a joint statement urging the parties to postpone the no-confidence procedure until the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis abated. Acting Prime Minister Kurti alleged that the United States aided efforts to unseat his government (see "U.S.-Kosovo Relations"). Disagreement over the next steps has fueled an ongoing political crisis. Kurti supports holding early elections after the COVID-19 pandemic is under control, noting that Vetëvendosje's approval ratings have surged above 50% since the government collapse. President Thaçi and others have called for the formation of a new government without new elections. Thaçi initially offered Vetëvendosje, the largest party in parliament, the opportunity to propose a new government, but the party has not done so. Vetëvendosje would be unlikely to find majority backing for a new government under the current parliament. On April 30, President Thaçi formally offered LDK's Avdullah Hoti the opportunity to nominate a new government for parliamentary approval after LDK leadership indicated it had reached agreement with several parties in opposition. Kurti's Vetëvendosje challenged the move before the Constitutional Court, which suspended the presidential decree until May 29, 2020, pending further consideration. Kurti remains acting prime minister, but the situation is fluid. Sources: "Joint Declaration of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of France and Germany on the Situation in Kosovo," March 24; U.S. Embassy in Pristina, "Statement from U.S. Embassy on Extraordinary Session Tomorrow," March 24, 2020; Fatos Bytyci, "Kosovo Coalition Partner to File No-Confidence Vote in Government," Reuters, March 18, 2020; Shaun Walker, "Kosovan Acting PM Accuses Trump Envoy of Meddling," The Guardian, April 20, 2020; Amy MacKinnon, "Q&A: 'In the Balkans, if You Neglect History, it Will Backfire'," Foreign Policy, April 23, 2020; "Kosovo's Constitutional Court Delays Parliamentary Vote on New Prime Minister," RFE/RL, May 1, 2020.Analysts generally have been positive in their assessments of Kosovo's democratic development since 2008, particularly its active civil society, pluralistic media sector, and track record of competitive elections.5 At the same time, many regard corruption and weak rule of law to be serious problems.6

Analysts generally have been positive in their assessments of Kosovo's democratic development since 2008, particularly its active civil society, pluralistic media sector, and track record of competitive elections.5 At the same time, U.S. and EU officials, as well as watchdog groups such as the U.S.-based nongovernmental organization Freedom House, have urged Kosovo to more rigorously enforce anti-corruption rules and uphold judicial independence.6 Many regard corruption and weak rule of law to be serious problems.7 The so-called Pronto Affair, one of several scandals to emerge in recent years, raised allegations of nepotism on the part of the then-governing PDK. In 2018, 11 PDK officials, including a minister and a lawmaker, were indicted for allegedly offering public jobs to party backers. According to the U.S.-based nongovernmental organization Freedom House, the Pronto case showed "a systemic abuse of power and informal control over state structures."

7 Further, U.S. and EU officials, as well as watchdog groups such as Freedom House, have urged Kosovo to more rigorously enforce anti-corruption rules and uphold judicial independence.8

|

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kosovo government has adopted measures similar to those of other European countries, including restricted movement into and within the country, social distancing, and closure of schools and nonessential businesses. On March 30, 2020, the government approved a €179.6 million (about $194.7 million) emergency fiscal package to expand social support and aid economic sectors impacted by the crisis. (As of late April 2020, Kosovo had about 800 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 22 deaths attributed to the virus; as elsewhere in the world, those figures may be expected to change rapidly.) Kosovo has received assistance from its allies to address COVID-19. The United States has committed $1.1 million to Kosovo out of the $775 million made available as of May 1, 2020, for global emergency health, humanitarian, and economic assistance relating to COVID-19. The EU provided €5 million (about $5.5 million) in emergency vital supplies and has announced that it will further reallocate €68 million (about $74.3 million) in bilateral assistance to support Kosovo's recovery. The European Commission subsequently proposed additional macro-financial assistance to help mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic. On April 10, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved $56.5 million in emergency financial assistance to Kosovo to meet immediate needs stemming from COVID-19. Sources: Klaudjo Jonuzaj, "Kosovo Govt Approves 179.6 mln Euro Coronavirus Relief Package," SeeNews, March 31, 2020; European Commission, EU Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic in the Western Balkans Factsheet, March 30, 2020; U.S. Department of State, "UPDATE: The United States is Continuing to Lead the Humanitarian and Health Assistance Response to COVID-19," May 1, 2020; World Bank, Europe and Central Asia Economic Update Spring 2020: Fighting COVID-19; European Commission, "Coronavirus: Commission Proposes €3 Billion in Macro-Financial Assistance Package to Support Ten Neighboring Countries," April 22, 2020. |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Kosovo Serbs and Northern Kosovo

About 100,000 to 120,000 Serbs live in Kosovo, primarily in semi-isolated rural communities.910 Kosovo Serbs are accorded various forms of representation and partial autonomy under the 2008 constitution and related legislation. This framework is partly the result of U.S. and other foreignexternal pressure on Kosovo's leaders to incorporate power-sharing measures to bolster minority rights and protection.1011 These provisions established a municipal level of governance with specific areas of responsibility (most Serbs live in minority-majority municipalitiesmunicipalities where they form a majority). Power-sharing arrangements require Serb representation in parliament, the executive, and other institutions. Majority consent from minority members of parliament is mandatory on some votes, and Serbian has official language status. Nevertheless, some have questionedquestion the actual effectiveness of these measures in integrating Serbs.11

More than half of Kosovo Serbs live in minority-majority municipalities in central and southeastern Kosovo. These municipalities do not border Serbia and are largely integrated into Kosovo institutions, although wartime legacies of distrust and fear persist. By contrast, the situation in northern Kosovo is one of the most enduring challenges in Kosovo's state building since independence (see also "Relations with Serbia," below). About 40% of the Serb population lives in four Serb-majority municipalities north of the Ibar River that are adjacent to Serbia (see map in Figure 1).

Pristina has been unable to exert full authority in northern Kosovo, whereas Serbia has retained strong influence (albeit not full authority) therein the region despite the withdrawal of its forces in 1999. Kosovo Serbs turned to Serbian-supported parallel structures for security, health care, education, and other services.1213 Due to its grey-zone status, northern Kosovo is considered a regional hub for smuggling and other illicit activities.1314

Serbian List (Srpska Lista), the party that has dominated recent elections in northern Kosovo, is considered to be close to the Serbian government. There have been reports of harassment and intimidation against opposition Serb politicians in the north, most recently in the October 2019 elections.1415 The 2018 murder of opposition Serb politician Oliver Ivanović raised questions about the power structures and vested interests that prevail in northern Kosovo.1516

Economy

The 1998-1999 war with Serbia caused extensive damage to Kosovo's infrastructure and economy. Two decades later, economic recovery continues. Employment is an acute policy challenge; Kosovo's average 40% labor force participation rate is the lowest in the Western Balkans. The unemployment rate stood at about 2926% in 20182019, with disproportionately higher levels foramong working-age females and youth.1617 The economy and perceived limits to upward socioeconomic mobility contribute to high rates of emigration.

Kosovo's gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.8% in 2018 and is expected to grow by 4.2% in 2019. Recent growth is driven by investment, services exports, and consumption.4.2% in 2019. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that Kosovo's economy could contract by 5% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.18 Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Kosovo in 2018 was €214 million (about $240232 million), the lowest in the regionWestern Balkans. By contrast, remittances received from citizens abroad (primarily in European countries) amounted to €801 million (about $899868.6 million) in 2018, equivalent to 12% of GDP.1719

Kosovo's key trade partners are the EU and neighboring countries in the Western Balkans. Kosovo has largely liberalized trade with both blocs through its Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU (a cooperation framework that includes steps to liberalize trade) and as a signatory to the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) alongside other non-EU Balkan countries.18 Of 20 Kosovo's 2018 exports (totaling €367.5 million, about $412.6 million), nearly half went to CEFTA countries and about 30% to the EU2019 exports totaled about €382 million ($414 million), of which the largest shares went to CEFTA countries and the EU. India, Switzerland, and Turkey were other significant export markets. Kosovo's top exports are metals; mineral products; plastics and rubber; and prepared foods, beverages, and tobacco.1921

In lobbying for greater FDI, Kosovo officials tout the country's young workforce, natural resources, low corporate tax rate, use of the euro, and preferential access to the EU market. However, various impediments to investment remain, including corruption, weak rule of law, uncertainties over Kosovo's dispute with Serbia, and energy supply disruptions.2022

Relations with Serbia21

23

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008 with U.S. support. Serbia does not recognize Kosovo and relies on Russia in particular for diplomatic support. Many believe that Kosovo and Serbia's non-normalized relations impedethe lack of normalized relations between Kosovo and Serbia impedes both countries' prosperity and progress toward EU membership, imperil and imperils Western Balkan stability, and detract from pressing domestic reforms.

War and Independence

After centuries of Ottoman rule, Kosovo became part of Serbia in the early 20th century. After World War II, Kosovo eventually had the status of a province of Serbia, one of six republics of Yugoslavia. Some Serbian perspectives view Kosovo's incorporation as the rightful return of territory that was the center of a medieval Serbian kingdom and is prominent in national identity narratives. Kosovo Albanian perspectives, by contrast, largely view Kosovo's incorporation into Serbia as an annexation that resulted in the marginalization of the Albanian-majority population.2224

During the 1980s, Kosovo Albanians grew increasingly mobilized and sought separation from Serbia. In 1989, Serbia—then led by autocrat Slobodan Milošević, who leveraged Serbian nationalism to consolidate power—imposed direct rule in Kosovo. Throughout the 1990s, amid Yugoslavia's violent breakup and Milošević's continued grip on power in Serbia, human rights groups condemned Serbian repression of Albanians in Kosovo, including suppression of the Albanian language and culture, mass arrests, and purges of Albanians from the public sector and education institutions.25.23 In the late 1990s, the Albanian-led Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) launched an insurgency against Serbian rule in Kosovo. Serbia responded with increasingly heavy force in 1998 and 1999 (see "Transitional Justice," below).

Following a NATO air campaign against Serbian targets in early 1999, Serbia agreed to end hostilities and withdraw its forces from Kosovo. U.N. Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1244 authorized the U.N. Interim Administration Mission (UNMIK) to provide transitional civil administration and the NATO-led KFOR mission to provide security (both missions still operate on a smaller scale). Milošević lost power in 2000 amid mass protests in Serbia.

Kosovo's decision to declare independence in 2008 followed protracted, and ultimately unsuccessful efforts on the part of the international community to broker a settlement with Serbia. Serbia challenged Kosovo's actions before the International Court of Justice (ICJ); however, the ICJ's 2010 advisory opinion found that Kosovo had not contravened international law.

European Union-Facilitated Dialogue: Status and Prospects

Following the ICJ ruling, the EU and the United States urged Kosovo and Serbia to participate in a dialogue aimed at eventual normalization of relations, but with an initial focus on technical measures to facilitate the movement of goods and people and otherwise improve the quality of life. In 2012, the talks advanced to a political level, bringing together leaders from the two countries for EU-brokered meetings.24 Among the most contentious issues have been northern Kosovo, the situation of Serbian cultural and religious sites in Kosovo, and strategic resources like water, energy, and mines. 26 Leaders in both countries are constrained by public opinion and a political climate that tends to make major concessions costly.

Kosovo and Serbia's desiregoal to join the EU helps incentivize their participation in the dialogue; the EU maintains that neither country can join the union until they normalize relations. The EU at times has linked incremental progress in the dialogue to advancement in the EU accession process, leveraging domestic support for EU membership in both countries and the economic benefits of closer cooperation with the EU. Kosovo's participation in the dialogue also is motivated by its desire to clear a path to U.N. membership and, eventually, NATO and EU membership (Serbian recognitionapproval is seen as a key step to unlocking Kosovo's U.N. membership).

To date, the dialogue has produced 33 agreements, mostly of a technical nature. In 2013, Serbia and Kosovo reached the Brussels Agreement, which set out principles to normalize relations, including measures to dismantle Serbian-backed parallel structures in northern Kosovo and create an Association of Serb Municipalities (ASM) linking Kosovo's 10 Serb-majority municipalities. Implementation of the dialogue's agreements has progressed in some areas, such as Kosovo Serb electoral participation and the integration of law enforcement and the judiciary in the north into statewide institutions. It has lagged in other areas, such as in the energy sector and in the ASM.2527

Although the dialogue format does not predetermine a specific outcome, the EU has urged a "comprehensive, legally binding" agreement between the parties.2628 Two particularly thorny issues in any such agreement are the scope of Serbian recognition of Kosovo and the situation in northern Kosovo. It remains undetermined whether Serbia would fully recognize Kosovo or accept Kosovo's institutions and U.N. membership without formal recognition. It is also uncertain how northern Kosovo would be addressed in any final settlement. Prior to 2018 (see below), U.S. and EU officials rejected local (primarily Serbian) leaders' occasional hints at partition as a potential solution. The United States and the EU feared that transferring territory or changing borders along ethnic lines could set a dangerous precedent and destabilize the region. Alternatively, some consider the integration of the north into statewide institutions through autonomy measures, such as the ASM, to be a potential compromise that could preserve Kosovo's territorial integrity while offering concessions to Kosovo Serbs. However, the ASM has faced resistance from some in Kosovo due to concerns that it could, if undermine state integrity if it is endowed with significant executive functions and formalized links to Serbia, undermine state integrity.27.29

Since late 2015, there has been little progress in reaching new agreements or implementing existing ones. Further, a shift in focus absorbed some of the dialogue's energies: in 2018, Kosovo President Thaçi and Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić raised the prospect of redrawing borders as an approach to normalizing relations (sometimes described as a land swap, a partition, or a border adjustment). Analysts believe such a measure could entail transferring Serb-majority municipalities in northern Kosovo to Serbia, possibly in exchange for Albanian-majority areas of Serbia's Preševo Valley. To the surprise of some, Trump Administration officials broke with long-standing U.S. and EU opposition to redrawing borders/partition by signaling willingness to consider such a proposal if Kosovo and Serbia were to reach a mutually satisfactory agreement.2830 However, some European allies, particularly Germany, remain opposed. Both parties in the Kurti government and much of the to any such proposal. Acting Prime Minister Kurti and much of Kosovo's political class and population also oppose ceding territory.2931

The dialogue has been suspended since late 2018, when Kosovo imposed tariffs on Serbian goods in retaliation for Serbia's campaign to block Kosovo's Interpol membership bid and its efforts to lobby countries to "de-recognize" Kosovo. Serbian leaders say they will not return to negotiations until the tariffs are lifted. U.S. and European officials have repeatedly urgedrepeatedly called upon the two parties to restartreturn to talks.

In March 2020, Prime Minister Kurti announced the repeal of tariffs on raw material imports from Serbia. The following month, amid continued U.S. pressure, he announced the decision to conditionally repeal tariffs against Serbian goods and replace them with gradual reciprocity measures to match existing Serbian measures impacting the movement of goods and people.32 EU officials welcomed the tariff removal; however, U.S. officials expressed dissatisfaction with the reciprocity measures.33

Kosovo's parties and leaders have become increasingly divided over several aspects of the dialogue, particularly the terms of lifting tariffs against Serbia. Furthermore, acting Prime Minister Kurti has challenged President Thaçi's leadership of Kosovo's participation in the dialogue, arguing that the authority of the government (rather than the head of state) to lead efforts was confirmed in a prior Constitutional Court ruling.34

If the dialogue resumes, several issues could affect talks going forward. The Kurti government's approach to normalizing relations with Serbia remains to be seen. In opposition, Kurti's Vetëvendosje was critical of the dialogue and protested some of its agreements, including the ASM. In 2019 postelection interviews, Kurti hinted at raising the issue of wartime reparations, rejected the notion of a quick deal, and stated his intention to review existing agreements. Kurti also said he would assume leadership of the dialogue from President Thaçi, who has largely led Kosovo's participation to date.30 In February 2020, Kurti stated that he intended to lift the tariffs, conditional on "full reciprocity" measures in economic and political relations with Serbia.31

Separately, some observers caution that growing uncertainty over the Western Balkan countries' EU membership prospects could alter the incentive structure weaving together the dialogue and the accession process. Observers are also watching the effects of EU leadership changes.

Transitional Justice

Transitional justice relating to the 1998-1999 war is a sensitive, emotionally charged issue in Kosovo and Serbia and a source of friction in efforts to normalize relations. Serbian police, soldiers, and paramilitary forces were accused of systematic, intentional human rights violations during the conflict. About 13,000 people were killed, and nearly half of the population was forcibly driven out of Kosovo. An estimated 20,000 people were victims of conflict-related sexual violence. The vast majority of all victims were ethnic Albanians. On a smaller scale, some KLA fighters—particularly at the local level—carried out retributive acts of violence against Serb civilians, other minority civilians, and Albanian civilians whom they viewed as collaborators.3235

Before closing in 2017, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia tried several high-profile cases relating to the Kosovo conflict, including those of deposed Serbian leader Milošević, who died before his trial finished, and former Kosovo Prime Minister Haradinaj, who was twice acquitted of charges relating to his role as a KLA commander. Domestic courts in Kosovo and Serbia now handle most war crimes cases. Weak law enforcement and judicial cooperation between Kosovo and Serbia is an impediment in the many cases in which evidence, witnesses, victims, and alleged perpetrators are no longer in Kosovo.3336 Critics assert that low political will in Serbia in particular hampers transitional justice. Officials from successive post-Milošević Serbian governments have been criticized for downplaying or failing to acknowledge Serbia's role in the wars in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo in the 1990s and for fostering a climate that is hostile to transitional justice and societal reconciliation with the past.34

Transitional justice processes concerning the KLA are controversial in Kosovo. Under U.S. and EU pressure, in 2015 the National Assembly adopted a constitutional amendment and legislation to create the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor's Office. These institutions are part of Kosovo's judicial system but are primarily staffed by international jurists and located in The Hague, Netherlands, to allay concerns over witness intimidation and political pressure. They are to investigate the findings of a 2011 Council of Europe report concerning allegations of war crimes committed by some KLA units. The Specialist Chambers is controversial in Kosovo, because it is to try only alleged KLA crimes. In 2017, lawmakers from the then-governing coalition moved to abrogate the Specialist Chambers but backed down after the United States and allies warned that doing so would have "severe negative consequences."3538 More than 120 former KLA fighters are reported to have received summons for questioning during 2019, and analysts believe some Kosovo politicians could face indictment.3639

Relations with the EU and NATO

Both theThe EU and NATO have played key roles in Kosovo; these institutional relationships continue to evolve alongside Kosovo's state-building processes.

European Union

The EU has played a large role in Kosovo's postwar development. A European Union Rule of Law Mission (EULEX) was launched in 2008, assuming some tasks that UNMIK had carried out since 1999. The mission's scope has decreased over time as domestic institutions assume more responsibilities; today, EULEX's primary role is to monitor and advise on rule-of-law issues, with some executive functions.3740 EULEX's current mandate runs through June 2020. Additionally, the EU provided over €1.48 billion (about $1.656 billion) in assistance from 2007 to 2020.38

Kosovo is a potential candidate for EU membership and signed a Stabilization and Association agreement with the EU in 2014.3942 The next steps in Kosovo's EU membership bid are obtaining candidate status and launching accession negotiations, which would commence the lengthy process of harmonizing domestic legislation with that of the EU. Kosovo's EU membership bid is complicated by the fact that five EU member states do not recognize it.40

Kosovo's more immediate goal in its relationship with the EU is to obtain for its citizens visa-free entry into the EU's Schengen area of free movement, which allows individuals to travel without passport checks between most European countries. Kosovo is the only Western Balkan country that does not have this status, and its leaders assert that the country has met the EU's conditions.41

NATO

The NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR) was launched in 1999 with 50,000 troops as a peace-support operation with a mandate under UNSC Resolution 1244. KFOR's current role is to maintain safety and security, support free movement of citizens, and facilitate Kosovo's Euro-Atlantic integration. As the security situation in Kosovo improved, NATO defense ministers in 2009 resolved to shift KFOR's posture toward a deterrent presence. Some of KFOR's functions have been transferred to the Kosovo Police. The United States remains the largest contributor to KFOR, providing about 660 of the 3,500 troops deployed as of November 2019.4245 Any changes to the size of the mission would require approval from the North Atlantic Council, and be "dictated by continued positive conditions on the ground."4346 Many analysts assert that KFOR continues to play an important role in regional security.44

KFOR has played a key role in developing the lightly armed Kosovo Security Force (KSF) and bringing it to full operational capacity. KSF's current role is largely nonmilitary in nature, and is focused instead on emergency response. A recurring issue is how KSF may transform into a regular army. In December 2018, Kosovo lawmakers amended existing legislation to gradually transform KSF, drawing sharp objections from Kosovo Serb leaders and Serbia.4548 NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg called the measure "ill timed" given heightened tensions with Serbia, cautioned that the decision could jeopardize cooperation with NATO, and expressed concern that the decisionmaking process had not been inclusive.4649 The United States, however, expressed support for the Kosovo government's decision and urged officials to ensure that the transformation is gradual and inclusive of all communities.4750

U.S.-Kosovo Relations

The United States enjoys broad popularity in Kosovo due to its support during the Milošević era, its leadership of NATO's 1999 intervention, and its diplomatic support for Kosovo since 2008. The United States backs Kosovo's Euro-Atlantic ambitions, as well as the EU-facilitated dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia in the Kosovo war, its backing of Kosovo's independence in 2008, and its subsequent diplomatic support. The United States supports Kosovo's Euro-Atlantic ambitions. Kosovo regards the United States as a security guarantor and critical ally, and many believe the United States retains influence in domestic policymaking and politics.

The Trump Administration has signaled growing interest in securing a deal to resolve the Kosovo-Serbia dispute and stepping up U.S. engagement in the Western Balkans more broadly. U.S. officials assert that the full normalization of Kosovo-Serbia relations is a "strategic priority."4851 In August 2019, U.S. Secretary of State MikeMichael Pompeo appointed Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Matthew Palmer as his Special Representative for the Western Balkans, and shortly. Shortly thereafter, President Donald Trump appointed U.S. Ambassador to Germany (now also Acting Director of National Intelligence) Richard Grenell as Special Presidential Envoy for Serbia and Kosovo Peace Negotiations. Some analysts and Members of Congress question the logic of two high-level appointments with seemingly similar mandates but welcome increased U.S. engagement overall.49 Many officials in Kosovo and Serbia likewise supporthave welcomed the prospect of a greater U.S. role in efforts to normalize relations.

Ambassador Grenell has engaged in the issue of normalization on a number of fronts.50 He and other U.S. officials continue to urge Kosovo to revoke the tariffs against Serbia and call on Serbia to end its de-recognition campaign (see "European Union-Facilitated Dialogue: Status and Prospects," above). In January 2020, Ambassador Grenell and other U.S. officials announced two new Kosovo-Serbia agreements on air and rail links, pursuant to a strategy that focuses on economic growth and job creation as foundations for the normalization process.51 The direct U.S. role in brokering these agreements—seemingly outside of the EU-led dialogue—is In January 2020, U.S. officials announced two new Kosovo-Serbia agreements on transportation links, pursuant to a strategy that focuses on economic growth and job creation as foundations for the normalization process.52 In March 2020, the White House hosted informal talks between President Thaçi and President Vučić. U.S. efforts currently center on bringing the two parties back to negotiations. As mentioned, U.S. officials criticized the reciprocity principles that acting Prime Minister Kurti announced in April 2020 alongside the conditional lifting of tariffs.

The direct U.S. role in brokering the recent transportation agreements and greater U.S. involvement in efforts to normalize Kosovo-Serbia relations is largely a departure from the approach taken under previous Administrations, which strongly supported EU-led efforts to normalize relations but did not play a formal, direct role. News of the January 2020 U.S.-brokered agreements reportedly came as a surprise to some EU officials.52European officials, who in turn have underscored the EU's long-standing role in the normalization process and appointed an EU special representative for the dialogue.53 Some analysts, while welcoming greater U.S. involvement, nevertheless cautionassert that the United States is more effective in engaging the Western Balkans when its aimsactions and positions are in accordaligned with those of the EU and key allies in the EUits European allies; they contend that recent gaps between the United States and allies such as Germany on the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, as well as on the March 2020 no-confidence session, have undercut overall have undercut engagement efforts.53 The EU reportedly is considering appointing an EU envoy to Kosovo-Serbia negotiations, similar to the recent U.S. measure, although EU officials have publicly underscored that they do not view the EU and the United States to be competitors in brokering talks between Kosovo and Serbia.54

Financial Assistance

54

Some observers and several Members of Congress have expressed concern over recent U.S. policies toward Kosovo's government, such as pausing implementation of a $49 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Threshold Program and delaying the development of its proposed Compact Program, until Kosovo rescinds the tariffs. 55 Some Kosovo officials expressed dismay over what they describe as U.S. pressure on Kosovo to lift tariffs against Serbia without equivalent pressure on Serbia to cease its campaign to undercut Kosovo's international legitimacy. On April 13, 2020, the Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Ranking Member of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations released a joint letter to Secretary Pompeo that welcomed greater U.S. diplomatic engagement in efforts to normalize relations between Kosovo and Serbia but expressed concern over what they described as "heavy-handed" treatment of the weeks-old Kurti government. They urged greater cooperation with the EU and restarting implementation of Kosovo's MCC Threshold Program.56

Separately, acting Prime Minister Kurti alleged that U.S. officials had aided efforts to unseat his government in the March 2020 no-confidence session in hopes that a more pliable government in Pristina would quickly reach a deal with Serbia.57 U.S. officials have underscored that the United States is "committed to working with any government formed through the constitutional process" and rejected speculation that the United States was brokering a "secret plan for land swaps."58

Foreign AidThe United States is a significant source of foreign assistance to Kosovo (see Figure 2). U.S. assistance aims to support the implementation of agreements from the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue and to improve transparent and responsive governance, among other goals.5559 Additional assistance is provided through a $49 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Threshold Program that launched in 2017, with focus on governance and energy efficiency and reliability. Threshold programs are intended to help countries become eligible to participate in a larger Compact Program; in December 2018 and again in December 2019, the MCC board determined that Kosovo was eligible to participate in a compact.

|

|

Source: U.S. State Department Congressional Budget Justifications. The table excludes assistance extended through the Millennium Challenge Corporation and the Peace Corps. |

Cooperation on Transnational Threats and Security Issues

The United States and Kosovo cooperate to combat transnational threats and bolster security. Like elsewhere in the Western Balkans, Kosovo is a transit country and in some cases a source country for trafficking in humans, contraband smuggling (including illicit drugs), and other criminal activities. Kosovo is consideredObservers consider Kosovo to have a relatively strong legal framework to counter trafficking, smuggling, and other transborder crimes. At the same time, the United States and the EU have urged officials in Kosovo to better implement the country's domestic laws by more strenuously investigating, prosecuting, and convicting traffickers, as well as by improving victim support.5660

Combatting terrorism and violent extremism is a core area of U.S.-Kosovo security cooperation. Kosovo is a secular state with a moderate Islamic tradition, but an estimated 400 Kosovo citizens traveled to Syria and Iraq in the 2010s to support the Islamic State amid the terrorist group's growing recruitment efforts. As this policy challenge emerged, the United States assisted Kosovo with tightening its legal framework to combat recruitment, foreign fighter travel, and terrorism financing, as well as strengthening its countering violent extremism strategy.5761

The United States also provides support to Kosovo law enforcement and judicial institutions to combat terrorism and extremism. The State Department's Antiterrorism Assistance program, for example, has provided training or capacity-building support for the Kosovo Police's Counterterrorism Directorate and for the Border Police. Kosovo and the United States agreed to an extradition treaty in March 2016. In April 2019, the United States provided diplomatic and logistical support for the repatriation of about 110 Kosovo citizens from Syria—primarily women and children—who had supported the Islamic State or were born to parents who had. Some repatriated persons were indicted on terrorism-related charges.58

Kosovo has a sister-state relationship with Iowa that grew out of a 2011 State Partnership Program (SPP) between the Iowa National Guard and the Kosovo Security Force. That relationship has been hailed as a "textbook example" of the scope and aims of the SPP.5963

Congressional Engagement

Congressional interest in Kosovo predates Yugoslavia's disintegration. Through resolutions, hearings, and congressional delegations, many Members of Congress highlighted the status of ethnic Albanian minorities in Yugoslavia, engaged in heated debates over intervention underduring the Clinton Administration, urged the George W. Bush Administration to back Kosovo's independence, and supported continued financial assistance.

Congressional interest and support continues. In the 116th Congress, several hearings have addressed Kosovo in part or in whole, including an April 2019 House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on Kosovo's wartime victims and recent hearings on Western Balkan issues held by the Senate Armed Services Committee and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee's Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation.

Given Kosovo's geography, history, and current challenges, the country also factors into wider U.S. foreign policy issues in which Congress remains engaged. Such issues include transitional justice, corruption and the rule of law, combatting human trafficking and organized crime, U.S. foreign assistance, security in Europe, and EU and NATO enlargement.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

|

||||||

| 2. |

Freedom House, Nations in Transit 2018: Kosovo Country Profile, 2017. Hereinafter, Freedom House, Kosovo Country Profile. See also discussion in U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Kosovo Political Economy and Analysis, Final Report, December 2017. Hereinafter, USAID, Kosovo Political Economy and Analysis. |

||||||

| 3. |

Freedom House, Kosovo Country Profile; Franziska Tschinderle, "The Split Opposition," ERSTE Stiftung, 2019. |

||||||

| 4. |

While unification appears to have considerable (if fluctuating) support in Albania and Kosovo, some observers contend that politicians at times have strategically used pan-Albanian statements to mobilize political support or to pressure the |

||||||

| 5. |

Freedom House, Kosovo Country Profile. |

||||||

| 6. |

Freedom House, Kosovo Country Profile; European Commission, Kosovo 2019 Progress Report; U.S. State Department, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2019.

|

||||||

|

Freedom House, Kosovo Country Profile. The Basic Court of Pristina acquitted the 11 defendants in early 2020 citing lack of proof; however, the prosecutor in the case has pledged to appeal the verdict. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

See estimates in Tim Judah, "Kosovo's Demographic Destiny Looks Eerily Familiar," BalkanInsight, November 7, 2019; Florian Bieber, "The Serbs of Kosovo," in Sabrina Ramet et al., eds., Civic and Uncivic Values in Kosovo, (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2015), pp. 175-197. Hereinafter, Bieber, "Serbs of Kosovo." |

|||||||

|

Florian Bieber, "Power Sharing and Democracy in Southeast Europe," Taiwan Journal of Democracy, (Special Issue 2013); Ilire Agimi, "Governance Challenges to Interethnic Relations in Kosovo," in Mehmeti and Radeljić, eds., Kosovo and Serbia: Contested Options and Shared Consequences (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016), pgs. 85-105. Hereinafter, Agimi, "Governance Challenges." |

|||||||

|

See discussion in Agimi, "Governance Challenges." |

|||||||

|

Bieber, "Serbs of Kosovo"; OSCE Mission in Kosovo," Parallel Structures in Kosovo, October 2003. |

|||||||

|

See, for example, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Hotspots of Organized Crime in the Western Balkans, May 2019; Marko Prelec, "North Kosovo Meltdown," International Crisis Group, September 6, 2011. |

|||||||

|

European External Action Service, "Well-Administered and Transparent Elections Affected by an Uneven Playing Field, and Marred by Intimidation and Lack of Competition in the Kosovo Serb Areas," October 8, 2019. |

|||||||

|

"Ivanovic Named Radoicic as North Kosovo Dark Ruler," BalkanInsight, February 27, 2018. |

|||||||

|

World Bank, Fighting COVID-19; World Bank, Western Balkans Regular Economic Report: Rising |

|||||||

|

International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020.

|

|||||||

|

CEFTA countries include Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

U.S. Department of State, 2019 Investment Climate Statements: Kosovo. |

|||||||

|

For simplification, this report uses Serbia to refer to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992-2003) and the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro (2003-2006); Serbia was the dominant entity in both configurations. |

|||||||

|

See Leandrit I. Mehmeti and Branislav Radeljić, "Introduction" in Mehmeti and Radeljić, eds., Kosovo and Serbia: Contested Options and Shared Consequences (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016), pp. 3-13. |

|||||||

|

See, for example, Human Rights Watch, HRW World Report 1990-Yugoslavia, January 1, 1991. |

|||||||

|

On the early stages of the dialogue, see International Crisis Group, Kosovo and Serbia after the ICJ Opinion, 2010. |

|||||||

|

Donika Emini and Isidora Stakic, Belgrade and Pristina: Lost in Normalisation?, EU Institute for Security Studies, April 2018; Martin Russell, Serbia-Kosovo Relations: Confrontation or Normalisation? European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2019; BIRN, Big Deal: Lost in Stagnation, April 2015; Marta Szpala, Serbia-Kosovo Negotiations: Playing for Time Under Pressure from the West, Centre for Eastern Studies (Warsaw), August 21, 2018. A 2015 agreement elaborated on the proposed ASM's competences. |

|||||||

|

European Commission, 2019 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, May 29, 2019. |

|||||||

|

See footnote |

|||||||

|

"Bolton Says U.S. Won't Oppose Kosovo-Serbia Land Swap Deal," RFE/RL, August 24, 2018; U.S. Embassy in Kosovo, "Ambassador Kosnett's Interview with Koha Ditore," December 2, 2019. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

| |||||||

| 31. |

"U.S. Envoy Urges Kosovo to Drop Tariffs on Serbian Goods 'With No Reciprocity,'" RFE/RL, February 10, 2020. |

||||||

| 33.

|

|

"Kosovo Announces Removal of Tariffs on Serbian and Bosnian Goods," EuroNews, April 2, 2020. 34.

|

|

Perparim Isufi, "Pandemic Adds Fresh Uncertainty to Kosovo-Serbia Dialogue," BalkanInsight, April 16, 2020; "Kurti Expects to Enter Office in November," European Western Balkans, October 23, 2019. |

For further information, see Human Rights Watch (HRW), Under Orders: War Crimes in Kosovo, 2001 (hereinafter, HRW, Under Orders); Amnesty International, "Wounds That Burn Our Souls": Compensation for Kosovo's Wartime Rape Survivors, But Still No Justice, 2017; Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Kosovo/Kosova As Seen, As Told: The Human Rights Findings of the OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission |

||

|

|

|||||||

|

On Serbia, see Milica Stojanovic, "Serbia: A Year of Denying War Crimes," BalkanInsight, December 26, 2019; HRW, Under Orders; Humanitarian Law Centre (Belgrade), Report on War Crimes Trials in Serbia, 2019; and relevant sections in European Commission, Serbia Progress Report 2019. |

|||||||

|

U.S. Embassy in Kosovo, "Quint Member States Statement," January 4, 2018. |

|||||||

|

Serbeze Haxhiaj, "Kosovo: War Commanders Questioned as Prosecutors Step up Probes," BalkanInsight, December 27, 2019; Dean Pineles, "American Dilemma: What If Kosovo's Thaci is Indicted?" BalkanInsight, January 24, 2019. |

|||||||

|

European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo, "About EULEX;" UNMIK, "Rule of Law in Kosovo and the Mandate of UNMIK." |

|||||||

|

European Commission, "Kosovo on Its European Path," July 2018. |

|||||||

|

European Commission, Kosovo 2019 Progress Report. The SAA entered into force in 2016. |

|||||||

|

The five EU member states that do not recognize Kosovo are Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain. |

|||||||

|

Kosovo fulfilled a key requirement, the ratification of a border demarcation agreement with Montenegro, in 2018. European Commission, "Visa Liberalisation: Commission Confirms Kosovo Fulfils All Required Benchmarks," July 18, 2018; Die Morina, "Kosovo's EU Visa Liberalisation Hopes Dwindle in 2019," BalkanInsight, January 16, 2019. 45 | |||||||

|

NATO, "KFOR: Key Facts and Figures," November 2019; NATO, "NATO's Role in Kosovo," November 19, 2019. |

|||||||

|

NATO, "The Evolution of NATO's Role in Kosovo," November 19, 2019. |

|||||||

|

"Is KFOR Still Guaranteeing Stability and Security in Kosovo?" European Western Balkans, December 17, 2018. |

|||||||

|

"Kosovo Votes to Turn Security Force into Army," BalkanInsight, December 14, 2018. |

|||||||

|

"NATO Chief Warns Kosovo Over 'Ill-Timed' Army Plans," RFE/RL, December 5, 2018. |

|||||||

|

Fatos Bytyci, "NATO, U.S. Slap Kosovo's Move to Create National Army," Reuters, March 8, 2017. |

|||||||

|

U.S. Embassy in Pristina, "Special Representative for the Western Balkans Matthew Palmer," November 1, 2019. | |||||||

| 49. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation, Successes and Unfinished Business in the Western Balkans, hearing, 116th Cong., 1st sess., October 23, 2019. |

||||||

| 50. | See also "Trump Gave Grenell Full Mandate to Clinch a Quick Deal on Kosovo," Bloomberg, October 9, 2019. |

||||||

|

Julija Simic, "U.S. Envoy Tells Serbia, Kosovo to Make Concessions, Cooperate," Euractiv, January 24, 2020 |

|||||||

|

"Brisel 'zatečen' dogovorom o letu od Beograda do Prištine," Radio Slobodna Evropa, January 21, 2020. |

|||||||

|

"U.S., Germany Diverge on Serbia-Kosovo Plan to Redraw Border," Bloomberg, October 19, 2018; Florian Bieber, Leadership Adrift: American Policy in the Western Balkans, Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, August 2019; Austin Davis and Anila Shuka, "Trump Ally Richard Grenell's Kosovo-Serbia Post a Mixed Bag for Rapprochement," |

|||||||

|

| |||||||

| 56.

|

|

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Relations, "Engel & Menendez Express Concern about Trump Administration Approach to Serbia and Kosovo," press release, April 13, 2020. 57.

|

|

"Kosovo's Kurti Accuses U.S. Envoy of 'Direct Involvement' in Collapse of His Government," RFE/RL, April 20, 2020; Shaun Walker, "Kosovan Acting PM Accuses Trump Envoy of Meddling," The Guardian, April 20, 2020. 58.

|

|

U.S. Embassy in Pristina, "Joint Statement of Special Presidential Envoy Richard Grenell, Ambassador Kosnett, and Special Representative for the Western Balkans Matthew Palmer," March 26, 2020. |

U.S. Department of State, U.S. Relations with Kosovo, October 31, 2019. |

|

U.S. Department of State, 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report: Kosovo (Tier 2). |

|||||||

|

See U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Terrorism: Kosovo for 2014-2018. |

|||||||

|

"Kosovo is Trying to Reintegrate ISIL Returnees. Will It Work?" Al Jazeera, June 9, 2019. |

|||||||

|

"Iowa, Kosovo a Model National Guard State Partnership Program," National Guard, November 25, 2015. |