Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from November 21, 2019 to May 27, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Historical Background

- Egypt Under Sisi: 2013 to 2019

- Domestic Developments

- Democracy, Human Rights, and Religious Freedom

- Detention of American Citizens in Egypt

- Coptic Christians

- The Economy

- Macroeconomic Improvement, Microeconomic Pressures

- Energy Sector Increasingly Contributes to Growth

- Terrorism and Islamist Militancy in Egypt

- Sinai Peninsula

- Beyond the Sinai: Other Egyptian Insurgent Groups

- Egypt's Foreign Policy

- Israel and the Palestinians

- Gulf Arab Monarchies

- Libya

- The Nile Basin Countries

- Russia

- France

- U.S.-Egyptian Relations

- Current Issues in U.S.-Egyptian Relations

- Possible Egyptian Purchase of Russian Advanced Fighter Aircraft

- Possible Muslim Brotherhood Designation

- The April Corley Case

- Recent Action on U.S. Foreign Aid to Egypt

Figures

- Figure 1. Map of Egypt

- Figure 2. President Abdel Fattah al Sisi

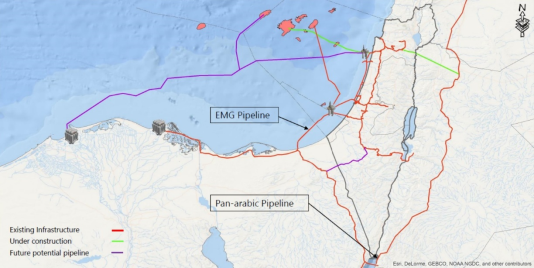

- Figure 3.Natural Gas Pipelines in Egypt, Israel, and the Eastern Mediterranean

- Figure 4.The Sinai Peninsula

- Figure 5.Israel Participate in Egypt-led Gas Forum

- Figure 6.GERD Talks in Washington

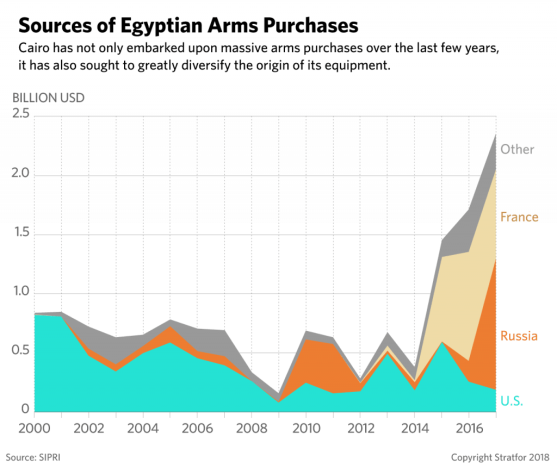

- Figure 7.Growing Russian and French Arms Sales to Egypt

- Figure 8.The aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln transits the Suez Canal.

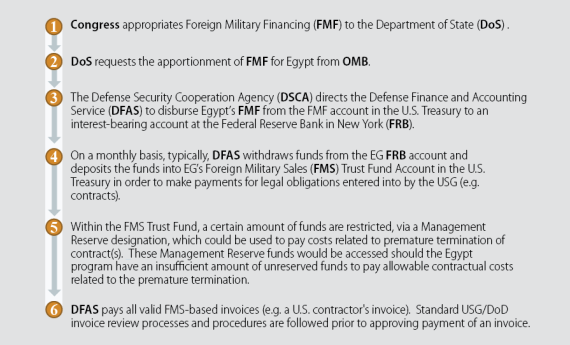

- Figure A-1. The Military Aid "Pipeline"

Tables

Summary

Historically, Egypt has been an important country for U.S. national security interests based on its geography, demography, and diplomatic posture. Egypt controls the Suez Canal, which is one of the world's most well-known maritime chokepoints, linking the Mediterranean and Red Seas. Egypt's population of more than 100 million people makes it by far the most populous Arabic-speaking country. Although today it may not play the same type of leading political or military role in the Arab world as it has in the past, Egypt may retain some "soft power" by virtue of its history, media, and culture. Cairo hosts both the 22-member Arab League and Al Azhar University, which claims to be the oldest continuously operating university in the world and has symbolic importance as a leading source of Islamic scholarship.

Additionally, Egypt's 1979 peace treaty with Israel remains one of the most significant diplomatic achievements for the promotion of Arab-Israeli peace. While people-to-people relations remain cold, the Israeli and Egyptian governments have increased their cooperation against Islamist militants and instability in the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip.

Personnel moves and amendments to the Egyptian constitution highlight apparent efforts by President Abdel Fattah al Sisi to consolidate power with the help of political allies, including colleagues from Egypt's security establishment. President Sisi, who first took power in 2013 after the military deposed his predecessor, has come under repeated international criticism for an ongoing government crackdown against various forms of political dissent and freedom of expression. The Egyptian government has defended its human rights record, asserting that the country is under pressure from terrorist groups seeking to destabilize Arab nation-states.

Egypt has a positive macroeconomic outlook, but significant challenges remain, and many Egyptian workers have endured several years of increases in the cost of living. In fall 2019, with many Arab governments facing youth-driven unrest, a few thousand Egyptians protested across several cities denouncing the Sisi-led government. Authorities responded with a wave of arrests and security forces deployed in urban areas across the country to deter additional protest.

The United States has provided significant military and economic assistance to Egypt since the late 1970s. Successive U.S. Administrations have justified aid to Egypt as an investment in regional stability, built primarily on long-running cooperation with the Egyptian military and on sustaining the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty.

All U.S. foreign aid to Egypt (or any recipient) is appropriated and authorized by Congress. Since 1946, the United States has provided Egypt with over $83 billion in bilateral foreign aid (calculated in historical dollars—not adjusted for inflation). Annual appropriations legislation includes several conditions governing the release of these funds. All U.S. military aid to Egypt finances the procurement of weapons systems and services from U.S. defense contractors.

For FY2019, Congress has appropriated $1.4 billion in total bilateral assistance for Egypt, the same amount it provided in FY2018. For FY2020, the President is requesting a total of $1.382 billion in bilateral assistance for Egypt. Nearly all of the U.S. funds for Egypt come from the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) account and provide grant aid with which Egypt purchases and maintains U.S.-origin military equipment.

Beyond the United States, President Sisi has broadened Egypt's international base of support to include several key partners, including the Arab Gulf states, Israel, Russia, and France. Since 2014, French-Egyptian ties have improved and Egypt has purchased major air and naval defense systems from French defense companies.

Historical Background

Since 1952, when a cabal of Egyptian Army officers, known as the Free Officers Movement, ousted the British-backed king, Egypt's military has produced four presidents; Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954-1970), Anwar Sadat (1970-1981), Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011), and Abdel Fattah al Sisi (2013-present). In general, these four men have ruled Egypt with strong backing from the country's security establishment. The only significant and abiding opposition has come from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, an organization that has opposed single party military-backed rule and advocated for a state governed by a vaguely articulated combination of civil and Shariah (Islamic) law.

Egypt's sole departure from this general formula took place between 2011 and 2013, after popular demonstrations sparked by the "Arab Spring," which had started in neighboring Tunisia, compelled the military to force the resignation of former President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011. During this period, Egypt experienced tremendous political tumult, culminating in the one-year presidency of the Muslim Brotherhood's Muhammad Morsi. When Morsi took office on June 30, 2012, after winning Egypt's first truly competitive presidential election, his ascension to the presidency was supposed to mark the end of a rocky 16-month transition period. Proposed timelines for elections, the constitutional drafting process, and the military's relinquishing of power to a civilian government had been constantly changed, contested, and sometimes even overruled by the courts. Instead of consolidating democratic or civilian rule, Morsi's rule exposed the deep divisions in Egyptian politics, pitting a broad cross-section of Egypt's public and private sectors, the Coptic Church, and the military against the Brotherhood and its Islamist supporters.

The atmosphere of mutual distrust, political gridlock, and public dissatisfaction that permeated Morsi's presidency provided Egypt's military, led by then-Defense Minister Sisi, with an opportunity to reassert political control. On July 3, 2013, following several days of mass public demonstrations against Morsi's rule, the military unilaterally dissolved Morsi's government, suspended the constitution that had been passed during his rule, and installed an interim president. The Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters declared the military's actions a coup d'etat and protested in the streets. Weeks later, Egypt's military and national police launched a violent crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood, resulting in police and army soldiers firing live ammunition against demonstrators encamped in several public squares and the killing of at least 1,150 demonstrators. The Egyptian military justified these actions by decrying the encampments as a threat to national security.1

Egypt Under Sisi: 2013 to 2019

Since taking power in 2013, President Abdel Fattah al Sisi's tenure has been predicated on the idea that a significant segment of the public, exhausted after several years of unrest and distrustful of Islamist rule, remains willing to forgo democratic liberties in exchange for the rule of a strongman hailing from the military. The authorities have maintained a constant crackdown against dissent, which initially was aimed at the Muslim Brotherhood but has evolved to encompass a broader range of political speech, encompassing anyone criticizing the government.

Egypt has experienced moderate macroeconomic growth under Sisi's rule, due largely to economic reforms under the International Monetary Fund's three-year, $12 billion Extended Fund Facility; grants, loans, and investments from Gulf Arab states (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait); and the revitalization of the oil and natural gas sector. However, as the economy has grown as a whole, many individual Egyptians have seen their standards of living decline due to rising prices and IMF-driven subsidy cuts. One recent Egyptian government study noted that the country's overall poverty rate increased 5% in the last two to three years and now nearly one in three Egyptians live below the poverty line.2

In 2019, with many Arab governments facing youth-driven protests, the sustainability of the political quiescence that has prevailed in Egypt since 2013 may be in question. In September 2019, after a former Egyptian defense contractor posted a series of social media videos accusing President Sisi and his family of corruption (see text box below), several thousand Egyptians protested across several cities denouncing the Sisi-led government. Authorities responded with a new wave of arrests, and security forces deployed in urban areas across the country to deter additional protest. While these protests represented the first large-scale anti-government demonstrations in several years, polls indicate that many Egyptians, even with their economic concerns, continue to trust law enforcement and security sector institutions.3

Under presidents Sisi and Trump, the tone of U.S.-Egyptian relations has been cordial. The President and Secretary of State have each praised President Sisi for combatting terrorism, promoting women's rights, and advancing religious freedom.4 On the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019, President Trump responded to a question about the aforementioned protests in Egypt saying, "I'm not concerned with it. Egypt has a great leader. He is highly respected, he's brought order. Before he was here, there was very little order. There was chaos. And so I'm not worried about that."5 In Congress, some Members have criticized Egypt's poor record on human rights and appropriators have passed legislation (see "U.S.-Egyptian Relations") that withholds the obligation of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) to Egypt until the Secretary of State certifies that Egypt is taking various steps toward supporting democracy and human rights.

|

|

Source: Map Resources, adapted by CRS. |

Domestic Developments

While successive Egyptian presidents since 1952 were effective at centralizing power, both within the ruling system and outside it, certain institutions (judiciary, military) and individuals enjoyed a considerable degree of independence from the executive. However, under President Sisi, there has been an unprecedented attempt to consolidate control over all branches of government while stymying opposition to his rule. In April 2019, voters approved amendments to the constitution that extend Sisi's current term until 2024 and permit him to run for a third term, potentially keeping him in office until 2030. The amendments also granted the president the authority to appoint all chief justices of Egyptian judicial bodies and the public prosecutor. During summer 2019, Sisi made those judicial appointments, leading one anonymous Egyptian judge to question this authority, saying that "The role of the judge is to be at arm's length from the executive, but this is inconsistent now with the fact the president of the republic is involved with a judge's transfer, promotion and accountability."6 Sisi also has inserted his older brother and oldest son into key security and intelligence positions. President Sisi's son Mahmoud is deputy head of the General Intelligence Services (GIS).

|

|

|

Source: Egyptian State Information Service. |

Egypt's one-chamber parliament consists of several parties and has largely been supportive of the government's legislative agenda. One report suggests that the parliament is generally pliant to the presidency and that lawmakers who have opposed government initiatives have at times been subject to smear campaigns and intimidation.7

Parliamentary elections were last held in late 2015. New elections are anticipated in spring 2020 for the House/Chamber of Representatives (HOR—450 seats) and a to-be-resurrected upper chamber (Consultative Assembly—180 seats). The Economist Intelligence Unit expects that "parliament will remain subservient to the interests of Mr Sisi and to those of the military and other favoured institutions. The public is broadly aware that this will be the case, and turnout is likely to be low at both the municipal and parliamentary votes."8 In summer 2019, when a group of leftist and labor activist politicians attempted to form what they referred to as a "coalition of hope" to compete in the 2020 elections, the Interior Ministry arrested several of the coalition's members, charging them with attempting to bring down the state using entities connected to the Muslim Brotherhood.9

|

Social Media Videos Allege Corruption and Spark Protest In 2019, 45-year-old Mohamed Ali, a former government defense contractor and actor now living in Spain, published a series of videos on social media in which he accused President Sisi and the Egyptian military of corruption. In his videos, Ali, who asserted that he was never fully compensated by the military for services rendered, alleged that the military spent millions of dollars constructing presidential palaces for Sisi and hotels for top ranking military officials that were either wasteful or never finished. Ali's videos circulated widely throughout Egypt, as his allegations broke taboos against speaking candidly about the role of the military in Egypt's economy. Such accounts of official corruption come at a time when many Egyptians have been experiencing higher prices on food and fuel due to inflation and IMF-mandated subsidy cuts. Ali admitted to his audience that he has been a willing participant in a corrupt system, saying "We are all corrupt, but we are not to blame. The system is to blame. He [Sisi] does not want to change the system. We need a new system."10 After Ali called for protests in September, several thousand Egyptians took to the streets across several cities, and authorities responded by imprisoning hundreds of demonstrators. Ali has vowed to continue to call for protests against Sisi, who in turn has argued that Ali is defaming the entire military and that any construction projects were built for the state. According to Sisi, "They say 'you're building palaces.' Yes, of course, I am…. I have built presidential palaces, and will build more, is it for me? … I'll build and build and build, but I am not doing it for me…. it's in Egypt's name."11 |

Democracy, Human Rights, and Religious Freedom

President Sisi has come under repeated international criticism for an ongoing government crackdown against various forms of political dissent and freedom of expressionEgypt: Background and U.S. Relations

May 27, 2020

Historical y, Egypt has been an important country for U.S. national security interests based on its geography, demography, and diplomatic posture. Egypt controls the Suez

Jeremy M. Sharp

Canal, which is one of the world’s most wel -known maritime chokepoints, linking the

Specialist in Middle

Mediterranean and Red Seas. Egypt’s population of more than 100 mil ion people makes Eastern Affairs it by far the most populous Arabic-speaking country. Although today it may not play the

same type of leading political or military role in the Arab world as it has in the past,

Egypt may retain some “soft power” by virtue of its history, media, and culture. Cairo hosts both the 22-member Arab League and Al Azhar University, which claims to be the oldest continuously

operating university in the world and has symbolic importance as a leading source of Islamic scholarship.

Additional y, Egypt’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel remains one of the most significant diplomatic achievements for the promotion of Arab-Israeli peace. While people-to-people relations remain cold, the Israeli and Egyptian

governments have increased their cooperation against Islamist militants and instability in the Sinai Peninsula and

Gaza Strip.

Throughout the first half of 2020, the Trump Administration has continued its policy of fostering good relations

with the Egyptian government by advancing military-to-military ties, trade, and investment. Several issues have caused tensions in U.S.-Egyptian relations, including Egypt’s continued detention of American citizens and the Egyptian military’s possible purchase of advanced Russian fighter jets.

Since 1946, the United States has provided Egypt with over $84 bil ion in bilateral foreign aid (calculated in historical dollars—not adjusted for inflation), with military and economic assistance increasing significantly after

1979. Annual appropriations legislation includes several conditions governing the release of these funds. Successive U.S. Administrations have justified aid to Egypt as an investment in regional stability, built primarily on long-running cooperation with the Egyptian military and on sustaining the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty. Al U.S. military aid to Egypt finances the procurement of weapons systems and services from U.S. defense

contractors.

For FY2021, the President is requesting a total of $1.4 bil ion in bilateral assistance for Egypt. Nearly al of the U.S. funds for Egypt come from the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) account and provide grant aid with which

Egypt purchases and maintains U.S.-origin military equipment.

As the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to spread throughout Egypt, the economy is facing a downturn due to the loss of tourism, private sector investment, foreign remittances, and Suez Canal revenue. To date, Egypt’s economic downturn has not outwardly affected the stability of the Egyptian

government, led by Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al Sisi. To minimize economic damage from COVID-19 countermeasures, the Egyptian government has enacted stimulus packages and borrowed $2.7 bil ion from the International Monetary Fund. President Sisi has maintained stability during the pandemic by continuing to use emergency powers and broad legal authority granted to the executive by parliament to suppress opposition.

Beyond the United States, President Sisi has broadened Egypt’s international base of support to include several

key partners, including the Arab Gulf states, Israel, Russia, China, France, and Italy.

In April 2019, Egyptian voters approved constitutional amendments that extend Sisi’s current term until 2024 and

permit him to run for a third term, potential y keeping him in office until 2030.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 17 link to page 20 link to page 23 link to page 26 link to page 32 link to page 12 link to page 28 Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1 Issues for Congress ......................................................................................................... 3

Egyptian Cooperation with Israel ................................................................................. 3

Egypt, Israel, and the Palestinians ........................................................................... 3 Sinai Peninsula .................................................................................................... 4 Natural Gas ......................................................................................................... 5

Democracy, Human Rights, and Religious Freedom ........................................................ 7

Detention of American Citizens in Egypt ................................................................. 8 Coptic Christians.................................................................................................. 9 Possible Egyptian Purchase of Russian Advanced Fighter Aircraft ............................. 11

Historical Background ................................................................................................... 12 Domestic Developments ................................................................................................ 12 Egypt’s Foreign Policy .................................................................................................. 14

Libya ..................................................................................................................... 15 The Nile Basin Countries .......................................................................................... 16 Russia.................................................................................................................... 18 France.................................................................................................................... 20

U.S.-Egyptian Relations ................................................................................................. 20

Other Issues in U.S.-Egyptian Relations ...................................................................... 22

Possible Muslim Brotherhood Designation ............................................................. 22 The April Corley Case......................................................................................... 23

Recent Action on U.S. Foreign Aid to Egypt ................................................................ 24

Figures Figure 1. Map of Egypt .................................................................................................... 2 Figure 2. The Sinai Peninsula............................................................................................ 5 Figure 3.Israel Participates in Egypt-led Gas Forum ............................................................. 6 Figure 4. Competition for Natural Gas in the Mediterranean .................................................. 7 Figure 5. President Abdel Fattah al Sisi ............................................................................ 13 Figure 6.GERD Talks in Washington DC .......................................................................... 16 Figure 7.Growing Russian and French Arms Sales to Egypt................................................. 19 Figure 8.The aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln transits the Suez Canal............................ 22

Figure A-1. The Military Aid “Pipeline” ........................................................................... 28

Tables Table 1. Democracy, Human Rights, and Development Indicators........................................... 8 Table 2. U.S. Bilateral Aid to Egypt: FY2016-FY2021 ........................................................ 24

Congressional Research Service

link to page 33 link to page 29 link to page 35 Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Table A-1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Egypt: 1946-2020..................................................... 29

Appendixes Appendix. Background on U.S. Foreign Assistance to Egypt................................................ 25

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 31

Congressional Research Service

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Overview Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous country of over 100 mil ion people,1 faces an uncertain future with the COVID-19 pandemic coming after several years of modest economic growth.

Prior to the outbreak, macroeconomic trends had appeared to be moving in a somewhat positive direction, and financial analysts considered Egypt to be one of the most promising emerging market destinations for foreign investment worldwide.2 As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads throughout Egypt, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that in 2020 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) wil grow 2%, a figure wel below pre-pandemic forecasts of over 5.5% growth.3 The pandemic is depressing a number of economic sectors in Egypt, such as tourism, which

accounts for 9.5% of employment and 5.5% of GDP.4 Lower natural gas prices and drops in worker remittances also are expected to depress government revenue and household incomes.

As of May 2020, Egypt’s economic downturn has not outwardly affected the stability of the Egyptian government, led since 2014 by Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al Sisi (herein referred to as President Sisi). In order to minimize economic damage from COVID-19 countermeasures,

the government has instituted a policy it cal s “co-existing with coronavirus,” in which seeks to balance restrictions such as partial curfews and quarantines with continued economic activity. The Egyptian government also has enacted stimulus packages directed to the tourism sector, increased the budget of the Ministry of Health, and upped its unemployment benefits for furloughed workers. However, despite the government’s attempt to continue economic activity, according to

one account, “The looser lockdown has not spared Egypt an economic crisis….The private sector, weak to start, is in free fal .”5 Although Egypt previously received IMF support ($12 bil ion loan for 2016-2019)6 geared toward reducing overal debt, the IMF also has added a new $2.77 bil ion tranche of financing to help Egypt during the pandemic.

In addition to expanding government benefits to low-income workers, President Sisi has maintained stability during the pandemic by continuing to use emergency powers and broad legal

authority granted to the executive by parliament to suppress opposition. Authorities have used media laws to arrest journalists who questioned government caseload statistics on charges of spreading “false news.”7 The Egyptian parliament also has amended and extended the nationwide 1 Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, Egypt has long struggled with strained domestic resources due overpopulation, which surpassed 100 million in 2020 and is predicted to rise as high as 150 million by 2050 (United Nations – World Population Prospects – 2019). In Egypt, overpopulation, particularly in the Cairo metropolis, has resulted in overcrowded classrooms, unemployment, and crippling traffic. See, “ As Egypt’s Population Hits 100 Million, Celebration is Muted,” Fanack.com, December 19, 2019. T he Egyptian government has launched family planning initiatives, which is a challenge in more rural areas. See, “'T wo is Enough,' Egypt T ells Poor Families as Population Booms,” Reuters, February 20, 2019. 2 While the Egyptian economy has experienced growth in tourism and energy, non -oil business activity had declined for six straight months prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, signaling that private sector growth was below expectations. See, “Egypt Non-Oil Private Sector Shrinks Faster in Jan – PMI,” Reuters, February 3, 2020. 3 International Monetary Fund, Confronting the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Middle East and Central Asia, April 2020. 4 “Egypt: Country Outlook,” Economist Intelligence Unit, April 24, 2020. 5 “Egypt Chose a Looser Lockdown. Its Economy is Still in Crisis,” The Economist, May 23rd 2020 edition. 6 In 2016, the IMF and Egypt reached a three-year, $12 billion loan agreement predicated on Egypt undertaking key reforms such as depreciating the currency, reducing public subsidies, and increasing taxes. While reforms such as reduced subsidies for electricity helped to reduce the annual deficit, poverty rates in Egypt have increased from 28% in 2015 to 33% in 2019. See, “Arab States and the IMF: A Bit too Austere,” The Economist, February 22, 2020. 7 Amnesty International, “Egypt: Prisons Are Now Journalists' Newsrooms,” Public Statement, May 3, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

state of emergency, which has been in place since April 2017. While the government claims these expansions were needed to cope with COVID-19, according to Human Rights Watch, only a few of the new amendments are “clearly tied to public health developments.”8

Figure 1. Map of Egypt

Source: Map Resources, adapted by CRS.

Throughout the first half of 2020, the Trump Administration has continued its policy of fostering good relations with the Egyptian government by advancing military-to-military ties,9 trade, and investment. Although the Administration has refrained from publicly rebuking the Sisi regime over its human rights record, several issues have caused tensions in U.S.-Egyptian relations, including Egypt’s continued detention of American citizens and the Egyptian military’s possible

purchase of advanced Russian fighter jets (see Issues for Congress section below). According to multiple reports, the U.S. Defense Department is actively pursuing a policy review of longstanding U.S. participation in the Sinai Peninsula peacekeeping and monitoring mission, known as the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO).10

8 Human Rights Watch, “ Egypt: Covid-19 Cover for New Repressive Powers,” May 7, 2020. 9 In May 2020, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency notified Congress of a potential sale to Egypt of up tp 43 refurbished AH-64E Apache attack helicopters for an estimated cost of $2.3 billion. See, U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Security Cooperation Agency, T ransmittal No: 19-74, May 7, 2020. 10 See CRS Insight IN11403, Possible Withdrawal of U.S. Peacekeepers from the Sinai Peninsula , by Jeremy M. Sharp.

Congressional Research Service

2

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Issues for Congress

Egyptian Cooperation with Israel Egypt’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel remains one of the single most significant diplomatic achievements for the promotion of Arab-Israeli peace. Congress has long been concerned with the preservation of the peace treaty and has appropriated foreign assistance and exercised oversight to

ensure that both parties maintain it. Since 2012, congressional appropriators have included in foreign operations appropriations law a requirement that before foreign aid funds can be provided to Egypt, the Secretary of State must certify that Egypt is meeting its obligations under the 1979

Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty.11

While people-to-people relations remain cold, Egypt and Israel have continued to find specific areas in which they can cooperate, such as containing Hamas in the Gaza Strip, countering

terrorism, and developing natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean (see sections below).

Egypt, Israel, and the Palestinians

Egypt’s triangular relationship with Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip is complex. On the one hand, Israel and Egypt cooperate against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, as they have since 2013. Egypt is opposed to Islamist groups wielding political power across the Middle East, and opposes Turkish and Qatari support for Hamas.12 On the Egyptian-Gaza border, Egypt has tried to thwart arms tunnel smuggling into Gaza and has accused Palestinian militants in Gaza of aiding terrorist

groups in the Sinai. On the other hand, in an acknowledgement of Hamas’ entrenched rule in Gaza, now in its second decade, Egypt couples its policy of containment with ongoing dialogue. The Egyptian-Hamas relationship has provided the Egyptian security and intel igence services an opportunity to play the role of mediator between Israel and Hamas. Egypt, at times, has attempted

to broker a long-term Israel-Hamas truce.13

Egypt controls the Rafah border crossing into Gaza, making Rafah the only non-Israeli-controlled passenger entryway into the Strip, which it periodical y closes for security reasons. Control over the Rafah border crossing provides Egypt with some leverage over Hamas, though Egyptian

authorities appear to use it carefully in order not to spark a humanitarian crisis on their border.14 Egypt also controls the Salah al Din Gate, a previously used crossing north of Rafah that opened for commercial use in 2018. According to one report, both Hamas and Egypt tax imported goods moving into Gaza through the gate, earning Hamas tens of mil ions of dollars per year in

revenue.15

After President Trump released his long-promised “Peace to Prosperity” plan for Israel and the Palestinians on January 28, 2020, the Egyptian Foreign Ministry released a statement that recognized “the importance of considering the U.S. administration’s initiative from the

perspective of the importance of achieving the resolution of the Palestinian issue, thus restoring to

11 See Section 7041(a)(1) of P.L. 116-94, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020. In addition to sustaining the treaty, the certification also requires Egypt to sustain its “ strategic relationship with the United States.”

12 “How Israel and Egypt are Coordinating on Gaza,” Al Monitor, July 12, 2018. 13 “Egypt T rying to Broker Broad Israel-Hamas T ruce, Hamas Says,” Associated Press, August 2, 2018. 14 “For Hamas, Reconciliation with Egypt Worth More than Qatari Cash,” Al Monitor, January 31, 2019. 15 “New Gaza Crossing Raises Questions about Blockade Policies,” PolicyWatch, number 3205, T he Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 23, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

3

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

the Palestinian people their full legitimate rights through the establishment of a sovereign independent state in the Palestinian occupied territories in accordance with international

legitimacy and resolutions.”16

President Sisi has refrained from making any public statements assessing the U.S. peace plan or the possibility of Israeli West Bank annexation. Instead, Egypt’s foreign ministry has worked collectively with other Arab states through the Egypt-based Arab League to express opposition to annexation. In late April 2020, Arab League foreign ministers issued a statement saying “The implementation of plans to annex any part of the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967,

including the Jordan Valley ... and the lands on which Israeli settlements are standing represents a

new war crime ... against the Palestinian people.”17

Sinai Peninsula

Several terrorist groups based in the Sinai Peninsula (the Sinai) have been waging an insurgency against the Egyptian government since 2011. The Islamic State’s Sinai Province affiliate (IS-SP)

is the most lethal terrorist organization in the peninsula.18 Since its inception in 2014, IS-SP has attacked the Egyptian military continual y, targeted Coptic Christian individuals and places of worship,19 and occasional y fired rockets into Israel. From January to November 2019, IS-SP conducted 282 attacks in Sinai that resulted in the deaths of 269 people, most of whom were

Egyptian security personnel.20

16 Facebook, Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Press Statement (unofficial translation), January 28, 2020. 17 “Arab League Slams Israeli Plan to Annex Occupied West Bank,” Al Jazeera, April 30, 2020. 18 T his group was formerly known as Ansar Bayt al Maqdis (Supporters of the Holy House or Partisans of Jerusalem). It emerged after the Egyptian revolution of 2011 and affiliated with the Islamic State in 2014. Estimates of its numerical composition range from 500 to 1,000. In Arabic, it is known as Wilayat Sinai (Sinai Province). Also referred to as ISIS-Sinai, ISIS-Egypt, and the Islamic State in the Sinai.

19 In November 2018, IS-SP claimed responsibility for an attack against Coptic Christian pilgrims traveling to t he monastery of Saint Samuel the Confessor 85-miles south of Cairo in the western desert.

20 Amos Harel, “ ISIS Is Still Alive and Well in Sinai, and Israel Fears a Major Attack on Its Egypt Border ,” Ha’aretz (Israel), December 18, 2019. T his article suggests that IS-SP attacks in the Sinai have decreased significantly, from 603 in 2017 to 333 in 2018.

Congressional Research Service

4

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

At times, Egypt and Israel have cooperated to counter terrorism in the Sinai. In a

Figure 2. The Sinai Peninsula

televised interview in 2019, President Sisi responded to a question on whether Egyptian-Israeli military cooperation was the closest it has ever been, saying “That is

correct. The [Egyptian] Air Force sometimes needs to cross to the Israeli side. And that’s why we have a wide range of coordination with the Israelis.”21 One news account suggested that, as of February 2018, Israel,

with Egypt’s approval, had used its own drones, helicopters, and aircraft to carry out more than 100 covert airstrikes inside Egypt

against militant targets.22

The 1979 Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty limits the number of soldiers that Egypt can deploy in the Sinai, subject to the parties’ negotiation of changes to address particular

circumstances. Egypt and Israel agree upon any short-term increase of Egypt’s military presence in the Sinai and to the construction of military and/or dual-use infrastructure.

Since Israel returned control over the Sinai

Source: http://www.mfo.org

to Egypt in 1982, the area has been partial y demilitarized, and the Sinai has served as an effective buffer zone between the two countries. The Multinational Force and Observers, or MFO,

are deployed in the Sinai to monitor the terms of the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty (see Figure 1).

Natural Gas

Israeli-Egyptian energy cooperation has significantly expanded since 2018. For Egypt,

cooperation with Israel is a key component of its broader regional strategy to become a key player in the development of undersea natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean. 23 Egypt is attempting to position itself as a regional gas hub, whereby its own gas fields meet domestic demand while imported gas from Israel and Cyprus can be liquefied in Egypt and reexported.24 Egypt has the Eastern Mediterranean’s only two large-scale liquefied natural gas terminals (located at Idku and Damietta), operating as partnerships between the state and foreign companies such as Italy’s ENI

and Royal Dutch Shel .

In 2018, Israeli and Egyptian companies entered into a decade-long agreement by reaching a $15

bil ion natural gas deal, according to which Israeli off-shore natural gas is exported to Egypt for

either domestic use or liquefaction before being exported elsewhere.

21 “Egypt’s President El-Sisi Denies Ordering Massacre in Interview his Government Later T ried to Block,” 60 Minutes, January 6, 2019.

22 “Secret Alliance: Israel Carries Out Airstrikes in Egypt, with Cairo’s O.K,” New York Times, February 3, 2018. 23 T he COVID-19 pandemic is significantly slowing natural gas production in the Eastern Mediterranean in spring 2020, as many analysts expect weaker demand in the months ahead. See, Clifford Krauss, “ Natural Gas Exports Slow as Pandemic Reduces Global Demand,” New York Tim es, May 11, 2020. 24 “Egypt Says U.S. Oil Firms Showing Appetite for Offshore P rojects,” Reuters, November 24, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

5

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 3.Israel Participates in Egypt-led Gas Forum

Source: Egypt’s Ministry of Petroleum. Note: Photo also features former U.S. Secretary of Energy Rick Perry (second from left).

Israeli and Egyptian companies have bought significant shares of an unused undersea pipeline (the EMG pipeline) connecting Israel to the northern Sinai Peninsula. The pipeline is now used to transport natural gas from Israel to Egypt as part of the previously mentioned gas deal between the U.S.-based company Noble Energy, its Israeli partner Delek, and the Egyptian company

Dolphinus Holdings.

As energy ties bind Israel and Egypt closer together, it also has made both parties wary of competitors such as Turkey. In January 2019, Egypt convened the first ever Eastern

Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), a regional consortium consisting of Egypt, Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian Authority, Cyprus, Greece, and Italy, intended to consolidate regional energy policies and reduce costs.25 Since then, it has held two other EMGFs, most recently in January 2020. Turkey, which is considered a rival in the competition to secure energy resources in the Mediterranean, is not a member of the EMGF. As Turkey has expanded its role in Libya, Libya’s

Government of National Accord (GNA) signed a maritime boundary agreement with Turkey in late 2019 which many observers view as favorable for Turkish interests in the Eastern Mediterranean.26 Afterward, Egypt cal ed the deal “il egal and not binding;” Israel said the deal

could “jeopardize peace and stability in the area.”27

25 “Natural Gas Fields Give Israel a Regional Political Boost,” Associated Press, January 23, 2019. 26 Selcan Hacaoglu and Firat Kozok, “T urkish Offshore Gas Deal with Libya Upsets Mediterranean Boundaries,” Bloom berg, December 6, 2019. 27 “T urkey-Libya Maritime Deal Rattles East Mediterranean,” Reuters, December 25, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

6

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 4. Competition for Natural Gas in the Mediterranean

Source: Bloomberg

Democracy, Human Rights, and Religious Freedom Egypt’s record on human rights and democratization has sparked regular criticism from U.S. officials and some Members of Congress. The Egyptian government rejects foreign criticism of its human rights practices as illegitimateil egitimate interference in Egypt'’s domestic affairs.1228 Certain

practices of Sisi'’s government, the parliament, and the security apparatus have been the subjects of U.S criticism. According to the U.S. State Department'’s report on human rights conditions in

Egypt in 2019:

Significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings by the government or its agents and terrorist groups; forced disappearanceEgypt in 2018

Human rights issues included unlawful or arbitrary killings by the government or its agents and terrorist groups; forced disappearances; torture; arbitrary detention; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; political prisoners; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; undue the worst forms of restrictions on free expression, the press, and the internet, including arrests or prosecutions against journalists, censorship, site blocking, and the existence of unenforced criminal libel; substantial interference with the rights of peaceful assembly and freedom of association, including government control over registration and financing of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); the rights of peaceful assembly and freedom of association, such as overly restrictive laws governing civil society organizations; restrictions on political participation; use of the law to arbitrarily arrest and prosecute violence involving religious minorities; violence targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; violence targeting LGBTI persons and members of other minority groups, and use ofuse of the law to arbitrarily arrest and prosecute LGBTI persons; and forced or compulsory child labor. The government inconsistently punished or prosecuted officials whowh o committed abuses,

28 “Egypt calls on US not to interfere in its Affairs,” The Middle East Monitor, March 15, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

7

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere in government. In most cases the government did not comprehensively investigate allegations of human rights abuses, including most incidents of violence by security forces, contributing to an environment of impunity.13

29

Authorities restrict access to the internet, censor online content, and monitor private online communications.1430 In 2018, parliament passed amendments to the Media and Press Law that, among other things, grantschanges, grant the regulatory body known as the Supreme Media Council the authority to suspend a social media account that has 5,000 followers or more if it posts false

news, promotes violence, or spreads hateful views.15”31 The Egyptian government also has attempted to require that technology companies share their user data with authorities.1632 In October 2019, the Egyptian cabinet issued a resolution mandating, among other things, that ride-sharing companies such as Uber submit to the Ministry of Transportation six months'’ worth of customers' data from all rides.17

’ data from al rides.33 Select international human rights, democracy, and development monitoring organizations provide the following global rankings for Egypt.

Table 1. Democracy, Human Rights, and Development Indicators

Issue

Index

Ranking

Democracy

Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2020

“Not Free”

Press Freedom

Reporters Without Borders, World Press

166/180 Countries

Freedom Index 2020

Corruption

Transparency International, Corruption

106/180 Countries

Perceptions Index 2019

Human

United Nations Human Development

116/189 Countries

Development

Programme, Human Development Index 2019

Source: Freedom House, Reporters Without Borders, Transparency International, and United Nations Human Development Programme.

Table 1. Democracy, Human Rights, and Development Indicators

|

Issue |

Index |

Ranking |

|

|

Democracy |

Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2019 |

"Not Free" |

|

|

Press Freedom |

Reporters Without Borders, World Press Freedom Index 2019 |

163/180 Countries |

|

|

Corruption |

Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2018 |

105/180 Countries |

|

|

Human Development |

United Nations Human Development Programme, Human Development Index 2018 |

115/189 Countries |

Source: Freedom House, Reporters Without Borders, Transparency International, and United Nations Human Development Programme.

Detention of American Citizens in Egypt

Detention of American Citizens in Egypt

The detention of American citizens/dual nationals in Egypt has strained U.S.-Egyptian relations at times. On January 13, 2020, Mustafa Kassem, a dual U.S.-Egyptian citizen who had been detained in Egypt since 2013, died of heart failure in an Egyptian prison after a two-year hunger strike. Some Members of Congress had long been concerned for Kassem, arguing that Egyptian authorities unlawfully detained and wrongfully convicted him.34 The Egyptian government has

defended its treatment of Kassem, claiming that he received adequate medical care and legal rights. After Kassem’s death, one report suggests that the State Department’s Bureau of Near

29 U.S. State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2019, Egypt

30 See, “T he Eye on the Nile,” Check Point Research, October 3, 2019. 31 “Egypt: Parliament Passes Amendments to Media and Press Law,” Global Legal Monitor, the Law Library, Library of Congress, August 6, 2018. 32 “Dilemma for Uber and Rival: Egypt’s Demand for Data on Riders,” New York Times, June 10, 2017. 33 “Egypt: Ministerial Resolution Issued to Regulate Activities of Ride-Sharing Companies,” Global Legal Monitor, T he Law Library, Library of Congress, October 22, 2019.

34 For additional background, see CRS Insight IN11216, Egypt: Death of American Citizen and Congressional Response, by Jeremy M. Sharp.

Congressional Research Service

8

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Eastern Affairs had raised the option of possibly cutting up to $300 mil ion in foreign aid to

Egypt.35

Although some U.S.times. In October 2019, Vice President Pence met with Egyptian Prime Minister Dr. Mostafa Madbouly, who committed to "advance discussions on several human rights cases of mutual concern, including Americans detained in Egypt."18 Although some American citizens may be detained in Egypt on non-political charges (such as narcotics

possession), notable detainee cases that may involve politically political y motivated charges include the following:

Mustafa Kassemfollowing: Khaled Hassan. Detained sinceJune 2013, Kassem is an auto parts dealerJanuary 2018, Hassan is a limousine driver from New York who has been accused of joining Islamic State-Sinai Province (IS-SP). Human rights organizations al ege that Hassan has been tortured while in prison.36 Hassan is a dual U.S. and Egyptian citizen. Mohammed al Amashah. Detained since March 2019, al Amashah is a 23-year- old medical student who was arrested in Tahrir Square on charges of misusing social media and helping a terrorist group after he displayed a sign that read, “Freedom for al prisoners.” In March 2020, he went on a hunger strike to protest his imprisonment. Al Amashah is a dual U.S. and Egyptian citizen. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread worldwide, particularly in prisons, some human rights advocates and Members of Congress37 have cal ed on the Egyptian government to release some of its detainees, including the few American citizens held on political y motivated charges.38 On April 10, a bipartisan group of Senators wrote a letter to Secretary of State Michael Pompeo urging him to “publicly cal for the release of Americans and political prisoners locked up abroad on baseless charges” to include detained American citizens in Egypt.39 The Egyptian government claims that it is taking preventive and protective measures for prisoners and prison staff and has suspended family visits to prisons to limit risk of infection.40 On April 23 in a phone cal between Secretary of State Pompeo and Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, Secretary Pompeo “emphasized that detained U.S. citizens be kept safe and provided consular access during the COVID-19 pandemic.”41 In early May 2020, Reem Mohamed Desouky,from New York who was sentenced to 15 years in prison in a mass trial in September 2018 for his alleged support of the Muslim Brotherhood. Kassem is a diabetic with a heart condition, and his health condition has deteriorated while incarcerated.19 Kassem is a dual U.S. and Egyptian citizen.- Khaled Hassan. Detained since January 2018, Hassan is a limousine driver from New York who has been accused of joining Sinai Province (IS-SP), an Islamic State affiliate group in Egypt. Human rights organizations alleged that Hassan has been tortured while in prison.20 Hassan is a dual U.S. and Egyptian citizen.

Reem Mohamed Desouky.Detained since July 2019, Desouky is a teacher from Pennsylvania who was arrested ata teacher from Pennsylvania who was arrested at the Cairo airport on charges of improper use of social media and who had been detained since July 2019, was released from prison and returned safely to the United States after she renounced her Egyptian citizenship. Desouky had been. Desouky isa dual U.S. and Egyptian citizen.

Coptic Christians

For years, the minority Coptic Christian community in Egypt has called

Most Egyptians are Sunni Muslims, but a smal percentage (perhaps 5% or less) are Coptic Christians, and this minority has faced discrimination and persecution, from the government as wel as from other citizens and terrorist groups. Congress has at times urged the government of

35 Jack Detsch, Robbie Gramer, Colum Lynch, “After Death of U.S. Citizen, State Department Floats Slashing Egypt Aid,” Foreignpolicy.com , March 31, 2020. 36 “Jailed in Egypt, American Limo Driver Attempts Suicide,” Washington Post, August 9, 2019. 37 https://www.murphy.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/murphy-statement-on-us-citizens-unjustly-detained-in-egypt

38 “Working Group on Egypt Call to Release Detainees,” March 26, 2020. Available online at: [https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/03/26/working-group-on-egypt-call-to-release-detainees-pub-81381] 39 See Senators T oomey, Casey Urge Release of Americans and Political Prisoners Detained Abroad to Protect them from COVID-19, April 10, 2020.

40 “Fear of Coronavirus Haunts Egypt's Cramped Jails,” Reuters, April 22, 2020. 41 U.S. State Department, Secretary Pompeo’s Call with Egyptian Foreign Minister Shoukry, April 23, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

9

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Egypt to protect this community. For example, in the 116th Congress, H.Res. 49, among other provisions, urges the Government of Egypt to enact “reforms to ensure Coptic Christians are

given the same rights and opportunities as al other Egyptian citizens…”

For years, the Coptic Christian community in Egypt has cal ed for equal treatment under the law.42 Since taking office, President Sisi has publicly calledcal ed for greater Muslim-Christian coexistence and national unity. In January 2019, he inaugurated Egypt'’s Coptic Cathedral of Nativity in the new administrative capital east of Cairo saying, "“This is an important moment in

our history. ... We are one and we will wil remain one."21

”43

Despite these public callscal s for improved interfaith relations in Egypt, the minority Coptic Christian community continues to face professional and social discrimination, along with occasional sectarian attacks. According to the latest annual U.S. Commission on International Religious

Freedom report, “religious discrimination [in Egypt] remained pervasive, including a disparity in policies regarding places of worship, a lack of opportunities for non-Muslims to work in key areas of government service, state security harassment of former Muslims, and recurring incidents

of anti-Christian violence, particularly in rural areas.”44

Major terrorist attacks against Christian places of worship also continue to threaten the Coptic community. Suicide bomber attacks against Coptic cathedrals in 2011, 2016, and 2017 collectively kil ed over 95 people and injured hundreds of others. In spring 2020, the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior broke up a terrorist cel planning attacks over Coptic Easter. One

policeman and seven suspects were kil ed in the operation.45

U.S. State Department report on religious freedom in Egypt, "Christians remained underrepresented in the military and security services. Christians admitted at the entry-level of government institutions were rarely promoted to the upper ranks of government entities."22

Coptic Christians also have long voiced concern about state regulation of church construction. They have demanded that the government reform long-standing laws (with two dating to 1856 and 1934, respectivelysome dating back to the

nineteenth century) on building codes for Christian places of worship. Article 235 of Egypt's ’s 2014 constitution mandates that parliament reform these building code regulations. In 2016, parliament approved a church construction law (Law 80 of 2016) that expedited the government

approval process for the construction and restoration of Coptic churches, among other structures.

Although Coptic Pope Tawadros II welcomed the law,23 others claim46 critics claimed that it continues to be discriminatoryal ow for discrimination. According to Human Rights Watch, "“the new law allowsal ows governors to deny church-building permits with no stated way to appeal, requires that churches be built '‘commensurate with'’ the number of Christians in the area, and contains security provisions that

risk subjecting decisions on whether to allowal ow church construction to the whims of violent

mobs.”47

42 In late 2019, an Egyptian Coptic woman won a landmark inheritance case before the Cairo Court of Appeal. T he court granted the plaintiff, a Coptic Christian woman, a share of her late father’s inheritance equal to that of her two male brothers by applying Christian Orthodox Personal Status Bylaws rather than Islamic law (which grants sons twice the share of daughters). T he plaintiff had argued that, per the Egyptian Constitution of 2014, she should not be subject to Islamic law in matters related to family law. See, George Sadek, “ Egypt: Court Grants Christian Woman Share of Father’s Estate Equal to Share of Her T wo Brothers,” Library of Congress, Global Legal Monitor, January 9, 2020. 43 “Egypt’s Sisi Opens Mega-Mosque and Middle East’s Largest Cathedral in New Capital,” Reuters, January 6, 2019. 44 Annual Report of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, April 2020. 45 Samy Magdy, “Egypt: Police Kill 7 Suspected Militants in Cairo Suburb, ABC News, April 14, 2020. 46 “HH Pope T awadros II: Church Construction Law Corrected an Error and Bandaged W ounds,” Coptic Orthodox Cultural Center, September 1, 2016.

47 “Egypt: New Church Law Discriminates Against Christians,” Human Rights Watch, September 15, 2016.

Congressional Research Service

10

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Possible Egyptian Purchase of Russian Advanced Fighter Aircraft

For over a year,48 there have been periodic reports of Egyptian plans to purchase Russian Sukhoi Su-35 Multi-Role Fighter Aircraft, a move that could potential y trigger U.S. sanctions under the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44/H.R. 3364, Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA], Title II – hereinafter

referred to as CAATSA).49 In May 2020, TASS Russian News Agency reported that the Gagarin Aircraft Manufacturing Association in Komsomolsk-on-Amur had started production of the aircraft under a contract signed in 2018.50 As of May 2020, U.S. officials have not publicly confirmed that Egypt and Russia are moving ahead with the deal. The Su-35 is Russia’s most

advanced fighter aircraft. Indonesia and Turkey also may purchase the Su-35.51

Section 231 of CAATSA requires that the President impose a number of sanctions on a person or entity who knowingly engages in a significant transaction with anyone who is part of, or operates for or on behalf of, the defense or intel igence sectors of the Government of the Russian

Federation. The Secretary of State has determined that the manufacturer of the Su-35, Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aviation Production Organization (KNAAPO) is a part of, or operates on behalf of, Russia’s defense and intel igence sectors for the purpose of meeting the definitional requirements of CAATSA Section 231.52 On September 20, 2018, the U.S. Treasury Department made its first designations pursuant to Section 231 against the Equipment Development Department of China’s Central Military Commission, as wel as its director, for taking delivery

from Russia of 10 Su-35 combat aircraft in December 2017 and S-400 surface-to-air missile

system-related equipment in 2018.53

On April 8, 2019, a bipartisan group of 17 Senators wrote a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo expressing concern regarding Egypt’s possible purchase of the Su-35.54 The next day, in testimony before the Senate, Secretary Pompeo remarked that “We’ve made clear that, if those systems were to be purchased, [under] statute CAATSA would require sanctions on the regime…. We have received assurances from [the Egyptians] that they understand that [sanctions wil be imposed] and I am very hopeful that they wil decide not to move forward with that

acquisition.”55

In November 2019, new reports surfaced indicating that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and

Secretary of Defense Mark Esper warned the Egyptian government that “Major new arms deals with Russia would—at a minimum—complicate future U.S. defense transactions with and

48 In April 2019, reports surfaced that the Egyptian Air Force was considering procuring over 20 Russian Sukhoi Su-35 Multi-Role Fighter Aircraft in a deal worth $2 billion . See, “ Egypt Signs $2 bln Deal to Buy Russian Fighter Jets – Kommersant,” Reuters, March 18, 2019. 49 Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 , title II, Countering America’s Adversaries T hrough Sanctions Act (CAAT SA; P.L. 115-44). For additional background, see CRS Report R45415, U.S. Sanctions on Russia, coordinated by Cory Welt . 50 Derek Bisaccio , “Su-35 Production for Egypt Begins,” Defense and Security Monitor, May 18, 2020. 51 “Russia Completes Deliveries of SU-35 Fighter Aircraft to China,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, April 16, 2019. 52 See, U.S. State Department, Section 231 of CAAT SA, https://www.state.gov/t/isn/caatsa/ 53 https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20180920_33.aspx. 54 Senator Bob Menendez website, Leading Senators Call on Sec. Pompeo to Raise Key Concerns during Bilateral Meeting with Egyptian President Sisi, April 8, 2019.

55 Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State and Foreign Operations Holds Hearing on Fiscal 2020 Budget Request for the State Department , CQ Transcripts, April 9, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

11

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

security assistance to Egypt.”56 Another U.S. official cautioned that the purchase puts Egypt “at risk of sanctions and it puts them at risk of loss of future acquisition.”57 Since then, there have

been no additional official U.S. public statements regarding the possibility of sanctioning Egypt.

Historical Background Since 1952, when a cabal of Egyptian Army officers, known as the Free Officers Movement, ousted the British-backed king, Egypt’s military has produced four presidents; Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954-1970), Anwar Sadat (1970-1981), Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011), and Abdel Fattah al Sisi (2013-present). These four men have ruled Egypt with strong backing from the country’s security establishment almost continual y. The one exception has been the brief period of rule by

Muhammad Morsi, who was affiliated with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (see below). That organization that has opposed single party military-backed rule and advocated for a state governed by a vaguely articulated combination of civil and Shariah (Islamic) law. For the most part, the Muslim Brotherhood has been the only significant and abiding opposition during the

decades of military-backed rule.

The one departure from Egypt’s decades of military rule, the brief period in which Morsi ruled, took place between 2011 and 2013, after popular demonstrations dubbed the “Arab Spring,” which had started in neighboring Tunisia, compel ed the military to force the resignation of

former President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011. During this period, Egypt experienced tremendous political tumult, culminating in Morsi’s one-year presidency. When Morsi took office on June 30, 2012, after winning Egypt’s first truly competitive presidential election, his ascension to the presidency was expected to mark the end of a rocky 16-month transition period. Proposed timelines for elections, the constitutional drafting process, and the military’s relinquishing of

power to a civilian government had been constantly changed, contested, and sometimes even overruled by the courts. Instead of consolidating democratic or civilian rule, Morsi’s rule exposed the deep divisions in Egyptian politics, pitting a broad cross-section of Egypt’s public and private

sectors, the Coptic Church, and the military against the Brotherhood and its Islamist supporters.

The atmosphere of mutual distrust, political gridlock, and public dissatisfaction that permeated Morsi’s presidency provided Egypt’s military, led by then-Defense Minister Sisi, with an opportunity to reassert political control. On July 3, 2013, following several days of mass public demonstrations against Morsi’s rule, the military unilateral y dissolved Morsi’s government,

suspended the constitution that had been passed during his rule, and instal ed Sisi as interim president. The Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters declared the military’s actions a coup d’etat and protested in the streets. Weeks later, Egypt’s military and national police launched a violent crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood, resulting in police and army soldiers firing live ammunition against demonstrators encamped in several public squares and the kil ing of at

least 1,150 demonstrators. The Egyptian military justified these actions by decrying the

encampments as a threat to national security.58

Domestic Developments President Abdel Fattah al Sisi’s tenure appears to have been predicated on the idea that a significant segment of the public, exhausted after several years of unrest and distrustful of Islamist rule, remains wil ing to forgo democratic liberties in exchange for the rule of a 56 “Pompeo Warns Egypt of Sanctions Over Russian Arms,” The Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2019. 57 “US: Egypt Could Face Sanctions if it Purchases Russian Fighter Jets,” Associated Press, November 18, 2019. 58 “Egyptian Cabinet Vows to Disperse Pro-Morsi Protest Camps,” The Guardian (UK), July 31, 2013.

Congressional Research Service

12

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

strongman hailing from the military. The authorities have limited dissent by maintaining a constant crackdown, which initial y was aimed at the Muslim Brotherhood but has evolved to

cover a broader range of political speech, encompassing anyone criticizing the government.

While successive Egyptian presidents since 1952 were effective at centralizing power, both within the ruling system and outside it, certain institutions (judiciary, military) and individuals enjoyed a considerable degree of independence from the executive. However, under President Sisi, there has been arguably an unprecedented attempt to consolidate control over al branches of government while stymying opposition to his rule. In April 2019, voters approved amendments to

the constitution that extend Sisi’s current term until 2024 and permit him to run for a third term, potential y keeping him in office until 2030. The amendments also granted the president the authority to appoint al chief justices of Egyptian judicial bodies and the public prosecutor. During summer 2019, Sisi made those judicial appointments, leading one anonymous Egyptian judge to question this authority, saying that “The role of the judge is to be at arm’s length from the executive, but this is inconsistent now with the fact the president of the republic is involved

with a judge’s transfer, promotion and accountability.”59 Sisi also placed his older brother and

oldest son in key security and intel igence positions, although his son is no longer in that role.60

Egypt’s unicameral parliament consists of several parties and has been largely

Figure 5. President Abdel Fattah al Sisi

supportive of the government’s legislative agenda. One report suggests that the parliament is general y pliant to the presidency and that lawmakers who have

opposed government initiatives have at times been subject to smear campaigns and

intimidation.61

Parliamentary elections were last held in late 2015. New elections are anticipated in late 2020 for the House/Chamber of

Representatives (HOR—450 seats) and a to-

Source: Egyptian State Information Service.

be-resurrected upper chamber (Consultative Assembly—180 seats). The Economist Intelligence Unit expects that “parliament wil remain subservient to the interests of Mr Sisi and to those of the military and other favoured institutions. The public is broadly aware that this wil be the case, and turnout is likely to be low at both the municipal and parliamentary votes.”62 In summer 2019, when a group of leftist and labor activist politicians attempted to form what they referred to as a “coalition of hope” to compete in the 2020 elections, the Interior Ministry arrested several of the

59 “Fears Over Egypt’s Judiciary Abound After Sisi Appointments,” Agence France Presse, August 21, 2019. 60 Reportedly, President Sisi has since removed his son Mahmoud from the deputy head of the GIS. According to one controversial report in the Egyptian publication Mada Masr, Mahmoud Sisi lost his position in the GIS after the

president’s inner circle concluded that his reputation was harmful to the Sisi regime. See, “President’s Eldest Son, Mahmoud al-Sisi, Sidelined from Powerful Intelligence Position to Diplomatic Mission in Russia,” Mada Masr, November 20, 2019. After Mada Masr published this account, security services temporarily detained an editor and two journalists and had their personal electronics confiscated. See, “Egypt News Outlet Raided after Report on Sisi’s Son,” Financial T imes, November 24, 2019.

61 “How Egypt’s President T ightened his Grip,” Reuters, August 1, 2019. 62 “Election Preparations Get Under Way,” Economist Intelligence Unit, October 23, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

13

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

coalition’s members, charging them with attempting to bring down the state using entities

connected to the Muslim Brotherhood.63

Egypt’s Foreign Policy Under President Sisi, Egypt’s foreign policy has been more active after a period of dormancy during the latter years of the late President Hosni Mubarak and the tumultuous two-and-a-half-year transition that followed Mubarak’s resignation.64 While President Sisi has continued Egypt’s

longtime policy of playing an intermediary role between Israel and the Palestinians, Egypt under Sisi has attempted to play a bigger role in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Since 2014, as Egypt has developed off-shore natural gas in the eastern Mediterranean, President Sisi has modernized the Egyptian Navy and improved economic ties with Israel, Italy, and Cyprus while also looking to deter regional rivals, such as Turkey. In January 2020, Egypt inaugurated a

new base (Berenice) on the Red Sea which, according to one account, wil al ow Egypt to

“project military power into the southern Red Sea.”65

As part of President Sisi’s strategy to revitalize Egyptian power in its immediate vicinity, it has

maintained longstanding U.S.-Egyptian security ties while prioritizing defense relationships with other actors.66 During Sisi’s presidency, Egypt has diversified its military-to-military and trade relationships away from the United States to include closer relations with Russia, China, and European nations such as France, Italy,67 and Germany.68 Between 2014 and 2018, Egypt was the third-largest arms importer global y (after Saudi Arabia and India) with France and Russia being

Egypt’s principal suppliers.69

63 “Prosecution T akes Up Political Line in Interrogation of Several Coalition for Hope Defendants, Hands Down 15 -day Detention Orders,” Mada Masr, June 27, 2019. 64 From about 2000 to 2013, Egypt had turned inward, unable to either lend its support or unilaterally advance major U.S. initiatives in the region, such as the war in Iraq or the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Moreover, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 profoundly and negatively impacted how some U.S. policymakers viewed Egypt. Whereas the bilateral relationship had previously focused on promoting regional peace and stability, the 9/11 attacks reoriented U.S. policy during the George W. Bush Administration, as Americans considered the possibility that popular disillusionment from authoritarianism might contribute to terrorism. Egypt has been a key element of this reorientation, as several Egyptian terrorists helped form the original core of Al Qaeda. For example, see Nabil Fahmy, “ Egypt in the World,” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, Summer 2012.

65 Jeremy Binnie, “Egypt Inaugurates Major Red Sea Base Complex,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, January 16, 2020. 66 T he United States continues to fund the procurement of major defense systems, as the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) has notified Congress of potential defense sales to Egypt worth an estimated $1.8 billion since 2017. For a list of major arms sales notifications to Egypt, see https://www.dsca.mil/tags/Egypt .

67 T he Egyptian Navy is reportedly in discussions to purchase two Italian FREMM Frigates from the Italian defense contractor Fincantieri for an estimated $1.3 billion. See, T om Kington, “ Italy in T alks to Sell Frigates to Egypt ,” Defense News, February 18, 2020. 68 T hyssenKrupp Marine Systems (T KMS) supplies the Egyptian Navy with T ype 209/1400mod submarines. T he same German company also is providing the navy with MEKO A‑200 frigates.

69 “T rends in International Arms T ransfers, 2018,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute ( SIPRI), March 2019. “Egypt looks beyond the US to meet Defence Needs,” Economist Intelligence Unit, April 15, 2019. Report used data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s database on arms transfers.

Congressional Research Service

14

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Libya The Egyptian government supports Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar and the Libyan National Army

(LNA) movement, which controls most of eastern Libya and has sought to take control of the rest of the country by force since April 2019. Haftar’s politics closely align with President Sisi’s, as both figures hail from the military and broadly oppose Islamist political forces. From a security standpoint, Egypt seeks the restoration of order on its western border, which has experienced occasional terrorist attacks and arms smuggling.70 From an economic standpoint, thousands of

Egyptian guest workers were employed in Libya’s energy sector prior to unrest in Libya in 2011, and Egypt seeks their return to Libya and a resumption of the vital remittances that those workers

provided the Egyptian economy.

As the war in Libya has escalated since Haftar launched his April 2019 offensive to seize Tripoli, there has been renewed attention to the role of outside actors in the Libya conflict. Although Egypt has participated in international diplomatic efforts (such as the January 2020 Berlin Conference) to halt fighting and reunify Libya, broadly speaking, Egypt’s policy toward Libya also is closely aligned with other foreign backers of the LNA, including Russia, France, and the

United Arab Emirates (UAE). As Turkey’s support for the Government of National Accord (GNA) has increased over the past year, there is some concern that foreign backers of Haftar wil increase their support and further destabilize Libya. In late 2019, President Sisi responded to reports of Turkey’s increased role by stating, “We wil not al ow anyone to control Libya ... it is a

matter of Egyptian national security.”71 To date, Egypt’s support for the LNA has included, among other things, the following:

In 2014, Egypt donated used combat aircraft (MiG-21s) and helicopters from its

own air force to the LNA.72

According to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Libya, Egypt conducted air

strikes against targets in Libya’s oil producing regions to support the LNA’s offensive there in 2017.73

According to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Libya, Egypt al owed the

United Arab Emirates to refuel aircraft in Egypt before launching sorties in Libya.74

According to one source, Egypt al owed the UAE to base its fleet of armed

Chinese-manufactured unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) at air bases in western Egypt.75

70 Egyptian officials have argued that terrorist violence emanating from Libya and directed against Egyptian citizens living and working there has compelled Egypt to militarily intervene in its neighbor’s civil war. On February 15, 2015, Islamists allied with the Islamic State released a video in which 21 hostages, most of whom were Egyptian Coptic Christians, were beheaded on a beach near the central Libyan town of Sirte. T he following morning, Egypt resp onded with air strikes against terrorist camps in Derna, which had been a former Islamic State stronghold in eastern Libya.

71 “Egypt's Sissi Slams Attempts to 'Control Libya,'” Agence France-Presse, December 17, 2019. 72 “T he Rise of Libya’s Renegade General: How Haftar built his War Machine,” Middle East Eye, May 14, 2019. 73 Letter dated 5 September 2018 from the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/2018/812, September 5, 2018.

74 Letter dated 29 November 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/2019/914, December 9, 2019.

75 Christopher Biggers, “Wing Loong II UAVs Deployed to Western Egyptian Base,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, February 27, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

15

Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations

Egypt has al owed UAE aircraft to deliver equipment to Libya via Egyptian

airspace.76

Egypt may have permitted the UAE’s Mirage 2000-9 fighter aircraft to be housed

at Sidi Barrani Air Base in western Egypt between deployments to Libya.77

The Nile Basin Countries Egypt relies on the Nile River78 for

hydroelectricity, agriculture, and most of its

Figure 6.GERD Talks in Washington DC