Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from June 25, 2019 to March 6, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

Summary

Over the past 30 yearsPoland: Background and U.S. Relations

March 6, 2023

Over the past three decades, the relationship between the United States and Poland has been close and cooperative. The United States strongly supported Poland'’s accession to

Derek E. Mix

the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1999 and backed its entry into the

Specialist in European

European Union (EU) in 2004. Poland has made significantmade strong contributions to U.S.- and NATO-

Affairs

led military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and. Poland and the United States continue to

work together closely on a range of foreign policy and international security issues.

Domestic Political and Economic Issues

The 2015 Polish parliamentary election resulted in a victory for the conservative-nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS), which won an absolute majority of seats in the lower house of parliament (Sejm). Mateusz Morawiecki (PiS) is Poland's prime minister and head of government. The center-right Civic Platform (PO) party led the government of Poland from 2007 to 2015. Since winning the election, Law and Justice has made changes to the country's judicial system and enacted other reforms that have generated concerns about backsliding on democracy and triggered an EU rule-of-law investigation.

Poland's next parliamentary election is due to occur in October or November 2019. European Parliament and regional election results indicate that support for Law and Justice remains strong, and the party is favored to win the 2019 election.

Law and Justice candidate Andrzej Duda won Poland's 2015 presidential election. The president is Poland's head of state and exercises a number of limited but important functions. The next presidential election is due to occur in May 2020.

Poland was one of the few EU economies to come through the 2008-2009 global economic crisis without major damage. As an EU member Poland is obligated to adopt the euro as its currency, but it has not set a target date for adoption and continues to use the złoty as its national currency.

Defense Modernization

Poland has been implementing an armed forces modernization plan since 2013, and it intends to spend approximately $49 billion on military equipment acquisitions and upgrades over the period 2017-2026. Completed and prospective purchases from U.S. suppliers, including advanced Patriot missiles and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, have a large role in this initiative. Poland is one of seven NATO members to meet the alliance',

mostly notably in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. In February 2023, U.S. President Joe Biden visited Poland for the second time in 11 months.

Response to Russia’s War Against Ukraine Poland has been a leader in Europe and NATO in supporting Ukraine following Russia’s February 2022 invasion. Poland is one of the leading providers of military assistance to Ukraine, and it serves as the main logistics and transit hub for international assistance to Ukraine. Poland also has taken in the most Ukrainian refugees of any country. Polish leaders have urged the EU adopt the strongest possible sanctions against Russia. Poland’s support for Ukraine has raised Poland’s profile in Europe and NATO and deepened the U.S.-Poland security and defense relationship.

Domestic Political Situation The conservative-nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) has led the government of Poland since 2015. Mateusz Morawiecki (PiS) is Poland’s prime minister (head of government). The center-right Civic Platform (PO) is the largest opposition party. Poland’s next parliamentary election is due to occur in autumn 2023.

Andrzej Duda is the president of Poland (head of state). Running as the candidate backed by PiS, Duda won a second term in office in Poland’s 2020 presidential election.

Law and Justice has made changes to the country’s judicial system and enacted other reforms that have generated concerns about democratic backsliding and caused tensions between Poland and the EU. As a result, the EU has withheld approximately $38.9 billion in grants and loans that Poland applied for from the EU pandemic recovery fund. The Polish government has initiated measures that attempt to address the EU’s concerns, but the dispute remains unresolved.

Defense Modernization and U.S.–Poland Defense Cooperation In 2022, Poland was one of nine NATO members to have met the alliance’s benchmark of spending at least 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) on defense. Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Poland adopted legislation that sets defense spending at a minimum of 3% of GDP and calls for doubling the size of the country’s armed forces over the next five years.

Arms purchases from the United States play a central role in Poland’s armed forces modernization planning. Over the past five years, U.S. defense sales to Poland have included F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, advanced Patriot air and missile defense systems, High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), and Abrams main battle tanks. In addition, the United States has approximately 10,000 military personnel deployed in Poland. At the 2022 NATO Summit, the United States announced that it would establish a permanent headquarters in Poland for the U.S. Army’s V Corps to command U.S. rotational forces in Europe.

Energy Security Poland has moved quickly to end reliance on Russia natural gas and oil imports, including by constructing a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal and a pipeline connecting Poland to Norwegian gas supplies. In 2022, Poland announced a deal with the U.S. company Westinghouse to build six nuclear reactors in Poland by the mid-2040s. Poland continues to rely on coal for more than two-thirds of its electricity generation.

Congressional Research Service

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, and it plans to reach 2.5% of GDP by 2030.

Defense Cooperation

Under the United States' European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) and the U.S. military's Operation Atlantic Resolve, as well as NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence mission, U.S. forces have expanded their presence in Poland since 2014 and increased joint training and exercises with their Polish counterparts. While U.S. forces participate in these missions on a rotational basis, the Polish government has proposed the establishment of a permanent U.S. base on Polish territory.

Visa Waiver Program

Although relations between Poland and the United States are largely positive, Poland's exclusion from the U.S. Visa Waiver Program (VWP) has been a point of contention for many years. Some Members of Congress have advocated extending the VWP to include Poland.

Relations with Russia

Relations between Poland and Russia have long been tense, and Polish leaders have tended to view Russian intentions with wariness and suspicion. Poland remains a leading advocate for forceful EU sanctions against Russia over its 2014 annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region and fostering of separatist conflict in eastern Ukraine.

Energy Security

Poland has promoted European energy integration, including projects to expand pipeline and electric grid interconnectivity in order to decrease reliance on Russia. Poland is a leading critic of Nord Stream 2, a Russian-owned pipeline project that would allow Germany to increase the amount of natural gas it imports directly from Russia via the Baltic Sea.

Outlook and Issues for Congress

Outlook and Issues for Congress Given its role as a close U.S. ally and partner, Poland and its relations with the United States are of continuing congressional interest. The main areas of interest include allied efforts to deter further Russian aggression and support Ukraine, bilateral defense cooperation, the future of NATO, energy security, and concerns about governance and democratic backsliding.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 18 Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Introduction and Issues for Congress .............................................................................................. 1 Response to Russia’s War Against Ukraine ..................................................................................... 2

Military Assistance .................................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Support ........................................................................................................................ 3

Domestic Political Situation ............................................................................................................ 4 Controversial Reforms and Tensions with the EU .......................................................................... 7 The Economy .................................................................................................................................. 9 Defense Spending and Modernization ........................................................................................... 10 Energy Security .............................................................................................................................. 11 Relations with the United States .................................................................................................... 12

Defense Relations.................................................................................................................... 13 Economic Ties ......................................................................................................................... 13

Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 14

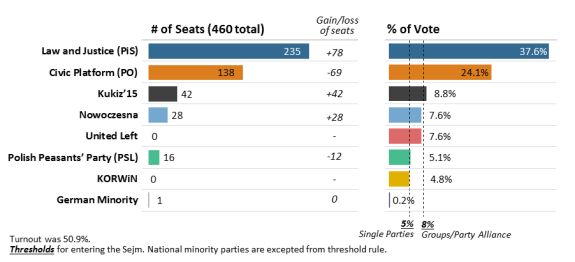

Figures Figure 1. Poland: Map and Basic Facts ........................................................................................... 1 Figure 2. Results of the 2019 Polish Parliamentary Election (Sejm) ............................................... 4

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 14

Congressional Research Service

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Introduction and Issues for Congress Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress consider Poland to be a strong ally of the United States and one of the most pro-U.S. countries in Europe. congressional interest. The main areas of interest include defense cooperation, energy security, and concerns about rule-of-law and governance issues.

Introduction and Issues for Congress

Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress consider Poland to be a key ally of the United States and one of most pro-U.S. countries in Europe. According to the U.S. State Department, areas of close bilateral cooperation with Poland include "NATO capabilities, counterterrorism, nonproliferation, missile defense, human rights, economic growth and innovation, energy security, and regional cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe."1

The Congressional Caucus on Poland is a bipartisan group of Members of Congress who seek to maintain and strengthen the U.S.-Poland relationship and engage in issues of mutual interest to both countries.2

Of the Central European and Baltic countries that have joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) since the end of the Cold WarUnion (EU), Poland is by far the most populous, has the largest economy, and is the most significant military actoractor in terms of security and defense issues. In 1999, with strong backing from the United States, Poland was among the first group of post-communist countries to join NATO. In 2004, again with strong support from the United States, it was among a group of eight post-communist countries to join the EU.

Figure 1. Polandpost-communist countries to join the EU. Many analysts assert that Poland, more than many other European countries, continues to look to the United States for foreign policy leadership.

Recently, developments related to Russia's resurgence and the attendant implications for U.S. policy and NATO are likely to have continuing relevance for Congress. A variety of factors make Poland a central interlocutor and partner for the United States in examining and responding to these challenges. Since Poland's 2015 parliamentary election, some Members of Congress also have expressed concerns about trends in the country's governance, discussed below.

Sources: Created by CRS using data from the U.S. Department of State and ESRI. FactFactual information from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database (April 2019October 2022) and CIA World Factbook.

Congressional Research Service

1

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the attendant effects on U.S. policy and NATO are likely to remain priority issues of interest and relevance for the 118th Congress. Poland is a central interlocutor and partner for the United States in responding to the war in Ukraine. Events in Ukraine have deepened U.S.-Poland security cooperation and brought increased urgency to security concerns along NATO’s eastern flank. Numerous congressional delegations have visited Poland since early 2022 to confer with Polish officials and conduct oversight of U.S. defense commitments and military activities in Central and Eastern Europe. Members of Congress visiting Poland also have examined humanitarian efforts to address the refugee crisis caused by the war in Ukraine.

Alongside the overall positive tone of U.S.-Poland relations and bilateral security cooperation, some Members of Congress have expressed concerns about democratic backsliding and rule of law issues in Poland since the country’s 2015 parliamentary election.

The Congressional Poland Caucus is a bipartisan group of Members of Congress who seek to maintain and strengthen the U.S.-Poland relationship and engage in issues of mutual interest to both countries.1

Response to Russia’s War Against Ukraine Poland is one of the international community’s biggest supporters of Ukraine and one of the strongest critics of Russia. Historically, Poland has had a difficult relationship with Russia. Poland’s view of Russia remains affected by the experience of Soviet invasion during World War II and Soviet domination during the communist era. Over the past two decades, Polish leaders have expressed warnings about the nature of Vladimir Putin’s government in Russia, tending to view Russia as a potential threat to Poland and its neighbors. Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and its initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014 sharpened Polish concerns about Russia’s intentions, and Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has put security at the top of Poland’s national agenda.

Following Russia’s February 2022 invasion, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki stated that, “Russia wants to annihilate Ukraine as a sovereign state” and called the invasion an existential threat to peace in Europe.2 Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau has described Russia’s targeting of the civilian population and infrastructure in Ukraine as “state terrorism.”3 Polish President Andrzej Duda has called Russia’s war on Ukraine “totally unprovoked aggression” and stated in January 2023 that it is “crucial to send additional support to Ukraine specifically modern tanks and modern missiles.”4 Polish leaders have argued for harsh sanctions against Russia, including the cancellation of energy imports and a total ban on trade, warned that Russia will not stop its aggression with Ukraine, and advocated for the EU to offer Ukraine a path to membership (the EU named Ukraine an official candidate country in June 2022).

Poland shares a 330-mile border with Ukraine. In November 2022, an errant Ukrainian air defense missile landed on Polish territory, killing two people. Earlier, in March 2022, Russia launched a missile attack against a military training base in Ukraine 15 miles from the Polish

1 For the 118th Congress, the co-chairs of the Congressional Poland Caucus are Representative Marcy Kaptur, Representative Bill Keating, Representative Chris Smith, and Representative Mike Turner.

2 “Mateusz Morawiecki Calls for a Strong European Army,” Visegrad Post, March 1, 2022. 3 Margaret Besheer, “OSCE Chair: Russian Actions in Ukraine ‘State Terrorism’,” Voice of America, March 14, 2022. 4 John Irish, “Davos 2023-Polish President Says Crucial to Give Ukraine Modern Weapons,” Reuters, January 18, 2023. Judy Woodruff and Dan Sagalyn, “Poland President Andrzej Duda on Russia’s War in Ukraine, Putin’s Nuclear Threats,” PBS News Hour, September 21, 2022.

Congressional Research Service

2

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

border, killings dozens of people. Such incidents have raised concerns about the conflict in Ukraine potentially spreading to NATO member countries. (Poland also shares a 130-mile border with Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave and a 260-mile border with Russia’s ally Belarus.)

Military Assistance As of early 2023, Poland is the third largest donor of military aid to Ukraine, behind the United States and the United Kingdom. Military assistance committed by Poland to Ukraine between January 2022 and January 2023 was valued at approximately $2.64 billion and included 240 T-72 main battle tanks, as well as infantry fighting vehicles, self-propelled howitzers, multiple rocket launchers, air defense systems, unmanned aerial vehicles, mortars, small arms, and ammunition.5

In January 2023, Polish officials announced plans to transfer German-made Leopard main battle tanks to Ukraine and urged other European countries to do likewise. Poland is training Ukrainian personnel on operating Leopard tanks at a military base in Poland.6

Poland also functions as the main logistics center and transit hub for delivering international military assistance to Ukraine. The city of Rzeszów, in southeastern Poland, has been a particularly important focus of such activity.

Refugee Support As of February 21, 2023, more than 1.56 million refugees from Ukraine had registered for temporary protection in Poland since February 2022, the largest number of Ukrainian refugees received by any country.7 In keeping with the EU Temporary Protection Mechanism adopted in March 2022, registered Ukrainian refugees receive the same access to public services and social benefits as Polish citizens.

Support thus far for assisting Ukrainian refugees has been widespread across Polish society and political parties. In a February 2023 speech, President Duda noted that “there are no refugee camps in Poland” due to the Polish people’s willingness to welcome Ukrainian refugees into their homes.8 Poland shares many cultural and historical ties with Ukraine; in total, approximately 3.5 million Ukrainians live in Poland. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that the cost to Poland of hosting and supporting Ukrainian refugees totaled €8.36 billion (approximately $9.2 billion) in 2022.9 Poland also is hosting a number of international humanitarian relief efforts for the refugees. (For additional information, see CRS Insight IN11882, Humanitarian and Refugee Crisis in Ukraine, by Rhoda Margesson and Derek E. Mix.)

5 Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Ukraine Support Tracker, February 21, 2023. According to the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker, between January 24, 2022 and January 15, 2023, the United States committed military assistance to Ukraine valued at €44.34 billion, the United Kingdom committed €4.89 billion, and Poland committed €2.43 billion. Germany committed the fourth most military assistance to Ukraine, €2.36 billion, and Canada the fifth most, €1.29 billion. 6 Lara Jakes, “Ukrainians Demonstrate Training on Leopard Tanks in Poland,” New York Times, February 13, 2023. 7 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Operational Data Portal, Ukraine Refugee Situation. As of February 20, 2023, nearly 4.9 million refugees from Ukraine had registered for Temporary Protection or similar national schemes in Europe.

8 Government of Poland, Message by the President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda, February 24, 2023. 9 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Migration Outlook 2022, p. 105.

Congressional Research Service

3

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Domestic Political Situation Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki of the conservative-nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) leads the government of Poland. United Right, an alliance of three political parties led by Law and Justice, won the 2019 parliamentary election with 43.6% of the vote, giving the parties 235 of the 460 seats in the Sejm, Poland’s lower house of parliament.10 (The coalition fractured in 2021, depriving the government of a parliamentary majority; see below.) Law and Justice has led Poland’s government since winning the 2015 election as the head of a similar electoral alliance that received 37.6% of the vote and 235 seats in the Sejm.

Civic Coalition, a centrist electoral alliance of parties led by the center-right Civic Platform (PO) party, came in second place in the 2019 election with 27.4% of the vote and 134 seats in the Sejm.11 Civic Platform led the government of Poland from 2007 to 2015, and it has since been the largest opposition party in the Sejm.

The Left (Lewica), an electoral alliance of left-wing parties, came in third place in the 2019 election with 49 seats; Polish Coalition, a center-right electoral alliance led by the Polish Peasants’ Party (PSL), won 30 seats; Confederation Liberty and Independence (Konfederacja), an electoral alliance of far-right parties, won 11 seats.

Figure 2. Results of the 2019 Polish Parliamentary Election (Sejm)

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Information from Poland National Electoral Commission, at https://pkw.gov.pl/uploaded_files/1571084597_obwieszczenie_sejm.pdf.

In the 2019 election, the Law and Justice-led coalition lost the majority it had held in the 100-seat Polish Senate, the country’s upper house of parliament, dropping from 61 seats to 48. Civic Platform, other opposition parties, and independent candidates won 52 seats. Winning the Senate allows opposition parties to propose amendments to legislation passed by the Sejm and to slow

10 The other parties in the 2019 United Right electoral alliance were the conservative-nationalist United Poland party, led by Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro, and the socially conservative-economically liberal Agreement party. The three parties subsequently formed a coalition government. Election results from the National Electoral Commission, at https://pkw.gov.pl/uploaded_files/1571084597_obwieszczenie_sejm.pdf.

11 The other parties in the 2019 Civic Coalition electoral alliance were the liberal Modern (Nowoczesna) party, the center-left Polish Initiative party, and the center-left Greens.

Congressional Research Service

4

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

down the legislative process. The two houses of parliament do not have equal status, however, as the Polish Constitution “provides the Sejm with a dominant role in the legislative process.”12

Andrzej Duda, the president of Poland, won the 2015 and 2020 presidential elections as the candidate backed by the Law and Justice party. He won re-election with 51.2% of the vote in the second round of voting in 2020, defeating the Civic Platform candidate and mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, in Poland’s closest presidential election since the end of communism in 1989. The president, who serves a five-year term, is Poland’s head of state and resigns party membership upon election. The president exercises functions including making formal appointments, overseeing the country’s executive authority, influencing legislation, representing the state in international affairs, and acting as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.13

Jarosław Kaczyński is head of the Law and Justice party; many observers assert that Kaczyński remains the most powerful politician in Poland who, as party chairman, exerts considerable influence behind the scenes.14 Jarosław Kaczyński co-founded Law and Justice with his twin brother Lech in 2001 and served as prime minister in 2006-2007. Lech Kaczyński was the president of Poland from 2005 to 2010, when he died in an airplane crash in Russia that also killed 95 other people, including many high-ranking Polish officials.

In winning the 2019 election, United Right received the largest share of the popular vote won by any political party or electoral alliance in a Polish election since 1989, but was unable to increase its number of seats in the Sejm.15 Voter support for Law and Justice increased despite strong criticism of the party’s policies by domestic political opponents, European officials, and international media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Particular targets of criticism have included a series of reforms to the judicial system and public media, the government’s contentious relationship with the EU, leaders’ anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rhetoric and regional “LGBT-free zones,” and the tightening of restrictions on abortion. Critics charge that the Law and Justice party’s policies and reforms since 2015 have undermined judicial independence and damaged democracy in Poland (see Controversial Reforms and Tensions with the EU section below).

Analysts attribute the success of Law and Justice partially to a perception among its voters that the party places strong emphasis on fulfilling election promises and reflecting the preferences of its voters.16 Law and Justice has moved to reform national institutions, most notably the judiciary, which it has argued were in need of rebalancing. The party, which has close ties with the Catholic Church, has appealed to socially conservative voters by pushing back against perceived cultural

12 Sejm of the Republic of Poland, Sejm in the System of Power, at https://www.sejm.gov.pl/english/sejm/sejm.htm. Only the Sejm decides on the final wording of legislation, and an absolute majority of the Sejm can vote to reject amendments proposed by the Senate or to deny a Senate motion to reject proposed legislation. The Sejm alone decides whether to accept or override a presidential veto, appoints the government and conducts oversight of its activities, and appoints judges to the constitutional tribunal. The Senate has a role in making some official appointments, and the consent of the Senate is required for constitutional amendments and ratifying international agreements. See Senate of the Republic of Poland, How an Act Is Made? and The Role of the Senate in the Constitutional Structure of the Polish State, at https://www.senat.gov.pl/en/about-the-senate/senat-wspolczesny/.

13 See Official Website of the President of Poland, at https://www.president.pl/en/president/competences/. 14 Sarah Huemer, “Poland’s Kaczyński to Quit Government Role and Focus on Party Leadership,” Politico Europe, October 13, 2021.

15 Members of the Sejm are elected to four-year terms through an open-list proportional representation system in which there are 41 multi-member constituencies with between 7 and 20 members each. Members of the Polish Senate are elected to four-year terms by plurality vote in 100 single-member constituencies.

16 Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse, Poland’s 2019 Parliamentary Election, Warsaw Institute, November 5, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

5

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

liberalism and promoting itself as the defender of the “traditional family, Polish national identity, and Christian values.”17

Civic Platform’s inability to make gains in the 2019 parliamentary election and its loss in the 2020 presidential election reflected analysts’ assertions that the party has struggled to find effective leadership and promote a counter-narrative that broadens its support.18 Despite arguments that Law and Justice policies endanger the country’s institutions and democracy, observers note that Civic Platform and other opposition parties have had difficulties formulating a persuasive campaign agenda other than a wish to defeat Law and Justice.19

Civic Platform received a boost in July 2021 when Donald Tusk, who was prime minister from 2007 to 2014 and president of the European Council (the leading political institution of the EU) from 2014 to 2019, announced his return to national politics and intention to lead the party in the next election.

In large part, Polish politics have become characterized by an entrenched social divide between national-oriented social conservatives, represented by Law and Justice, and Western-oriented liberals, represented by Civic Platform. In the 2019 election, Law and Justice and its allies overwhelmingly won in the country’s more rural districts, while Civic Platform and other opposition parties won mainly in Poland’s large cities. Many voters, including many younger voters, shifted their support towards the ends of the political spectrum; parties comprising The Left alliance and the Confederation of far-right parties re-entered the Sejm after being shut out in the 2015 election.20

The United Right governing coalition has faced significant internal tensions. While there have been disagreements about several policy issues, the in-fighting takes place in the context of a power struggle between two rival wings of the coalition attempting to position themselves for the future leadership of the political right in Poland. Prime Minister Morawiecki heads the relatively moderate wing; Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro of the United Poland party leads a more hardline faction.

In August 2021, Prime Minister Morawiecki fired the leader of the socially conservative-economically liberal Agreement party from his post as a deputy prime minister amid tensions over economic plans and a controversial media law. The departure of some Agreement members from the government’s parliamentary caucus left the coalition with 228 members in the Sejm, three short of a majority.21 The government has proceeded as a minority government, marshalling the support of smaller parties and independent members to pass legislation.

The next parliamentary election is due in autumn 2023. As of February 2023, polling indicates support for a Law and Justice-led coalition at 36%, versus 30% for Civic Coalition, 10% for the new, centrist Poland 2050 party, 9% for the Left, and 7% for the far-right Confederation.22

17 Aleks Szczerbiak, “Why Is Poland’s Law and Justice Party Still So Popular?,” Polish Politics Blog, September 23, 2019.

18 Daniel Tilles, “Civic Platform Turns 20: Is Poland’s ‘Zombie Party’ Now Undermining Opposition to PiS?,” Notes From Poland, January 24, 2021.

19 Claudia Ciobanu, “Election Blues: Why Poland’s Opposition Keeps Losing,” Reporting Democracy - Balkan Insight, July 22, 2020.

20 Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse, Poland’s 2019 Parliamentary Election, Warsaw Institute, November 5, 2019. 21 See Sejm of the Republic of Poland, Current Members, at https://www.sejm.gov.pl/Sejm9.nsf/poslowie.xsp. 22 “Poland - National Parliament Voting Intention,” Politico Europe, at https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/poland/.

Congressional Research Service

6

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Controversial Reforms and Tensions with the EU As noted above, the Law and Justice party-led government has been criticized by domestic opponents and the EU for a range of controversial reforms related to social policies (including those that affect women and LGBT rights), public media, and perhaps most prominently, the judicial system. Critics charge that numerous moves enacted regarding the judicial system since late 2015 subvert institutional checks and balances, undermine judicial independence and the rule of law, and place the country’s courts under political control.23 Party leaders maintain that the judicial system needed extensive reform because it was slow and inefficient, judges were not properly vetted after the transition from communism to democracy, and procedures for selecting new judges lacked fairness and accountability.24

Reforms to the judicial system have included the following:25

Changes to the functioning of the country’s constitutional tribunal, a court

composed of 15 judges who decide whether legislation is constitutional. Critics argue that the Law and Justice government has sought to diminish the constitutional tribunal’s role as a systemic check on legislative power and to mold it into a rubber stamp for the party’s policies.

The replacement of the 15 judges on the National Council of the Judiciary with

new judges chosen by the Sejm; previously, other judges selected the members of the council. The role of the National Council of the Judiciary is to select and discipline the country’s judges and to safeguard the independence of the courts.

New discretionary power for the justice minister (who is also the country’s

prosecutor general) to remove and replace district court judges.

The establishment of a disciplinary chamber in the country’s Supreme Court with

the power to punish or dismiss judges based on their decisions or their criticism of the government’s judicial reforms. (The government formally abolished the chamber in June 2022; see below.)

Beyond the judicial system, a law adopted in 2016 granted the government the power to hire and fire management of public broadcasting stations, a function previously performed by a non-partisan National Broadcasting Council. The government subsequently established a new National Media Council, controlled by Law and Justice members, to regulate broadcast media and oversee public radio and television.26 The government maintained that the moves were needed to correct political bias and restore balance in the public media. Critics argue that the reforms have compromised the independence of public media and relegated it to publicizing the government’s official narrative.27 The taxpayer-funded TVP, which encompasses a large network

23 See, for example, Brittany Benowitz, Threats to Judicial Independence – Not Discussion of the Holocaust – Are the Real Threat to Polish Democracy, American Bar Association, January 19, 2019 and Christian Davies, Hostile Takeover: How Law and Justice Captured Poland’s Courts, Freedom House, May 2018. 24 Rob Schmitz, “Poland’s Overhaul of Its Courts Leads To Confrontation With European Union,” NPR, February 13, 2020.

25 Alistair Walsh, “What Are Poland’s Controversial Judicial Reforms?,” Deutsche Welle, November 5, 2019. 26 Nathan Stormont, How Poland’s Government Set Out to Conquer a Free Press, Freedom House, June 28, 2017. 27 Dariusz Kalan, “Poland’s State of the Media,” Foreign Policy, November 25, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

7

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

of public television and radio stations, is Poland’s largest broadcaster and reaches by far the largest audience in the country.28

Critics have raised additional concerns about media freedom in Poland after the energy company PKN Orlen purchased regional newspaper publisher Polksa Press from a German publishing company in 2020.29 PKN Orlen, which owns oil refineries, gas stations, and other energy assets in multiple countries, is the largest company in Central Europe; the Polish state is the largest shareholder in the company, and the Polish government controls the management. The acquisition brought under Orlen’s control 20 of Poland’s 24 daily regional newspapers, 120 weekly newspapers, and news websites with an estimated 17.4 million users.30

Multiple democracy indexes have registered declines in the quality of democracy in Poland. The Nations in Transit 2022 report published by the non-governmental organization Freedom House, measuring the quality of democratic governance in 29 countries in Europe and Eurasia, downgraded Poland’s score for the eighth consecutive year due to concerns about democratic backsliding.31 According to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Poland was among the 10 most “autocratizing” countries globally between 2012 and 2022.32 Law and Justice leaders and supporters dispute such portrayals, alleging that their political opponents have crafted an exaggerated narrative in an attempt to undo the results of elections and block the government’s ability to implement its agenda.

The European Union has undertaken a number of measures challenging the Law and Justice party’s reforms. In 2016, the European Commission (the EU’s executive institution) launched an inquiry into the effects of the judicial reforms and other controversial legislation in Poland. The inquiry concluded that the measures “structurally undermine the independence of the judiciary” and pose “a systemic threat to the rule of law in Poland.”33 The Commission subsequently proposed that the Council of the EU (the EU institution representing the national member state governments) determine whether to initiate an “Article 7” procedure; Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union allows for suspension of a member’s voting rights in the Council if it is found to breach EU core values.34 The measure was never likely to be enacted, however, because Hungary (which has similar tensions with the EU) vowed it would veto actions against Poland.

The Commission additionally launched a series of legal challenges asking the European Court of Justice (ECJ) to suspend provisions of Poland’s judicial reforms and rule on their compatibility with EU law. The Polish government has generally rejected the EU’s challenges, objecting that the EU is interfering with the country’s sovereignty and does not understand its legal system, and that the EU’s actions are politically motivated.35 In 2018, however, Poland complied with an EU 28 Rob Schmitz, “Poland’s Government Tightens its Control Over Media,” NPR, January 4, 2021. 29 “Court Looks Into Polska Press Takeover by Oil Giant PKN Orlen,” Reuters, June 7, 2022. 30 Jan Cienski and Paola Tamma, “Poland’s State-Run Refiner Becomes a Media Baron,” Politico Europe, December 7, 2020.

31 Freedom House, Nations in Transit 2022, Poland, at https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/nations-transit/2022. 32 Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Democracy Report 2023: Defiance in the Face of Autocratization at https://www.v-dem.net/documents/29/V-dem_democracyreport2023_lowres.pdf.

33 European Commission, Commission Recommendation (EU) 2018/103 of 20 December 2017 Regarding the Rule of Law in Poland Complementary to Recommendations (EU) 2016/1374, (EU) 2017/146 and (EU) 2017/1520.

34 European Commission, Proposal for a Council Decision on the Determination of a Clear Risk of a Serious Breach by the Republic of Poland of the Rule of Law, December 20, 2017.

35 Anna Wolska, “Polish Government Reacts To EU Court Ruling On Judicial Reform,” Euractiv, March 4, 2021. Holly Ellyatt, “Controversial Judicial Reform Still ‘Needed,’ Polish Prime Minister Says After EU Battle,” CNBC, January 22, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

court order suspending a law that allowed the president to decide whether to retire Supreme Court judges over the age of 65. The episode marked the first time Law and Justice backtracked on any major element of its controversial reform program. In 2021, the ECJ imposed a fine of €1 million (approximately $1.1 million) per day until Poland complies with a ruling to dissolve the Supreme Court disciplinary chamber.

The EU also developed a regulation linking regional funding from the EU budget to judicial independence and rule of law standards (Poland is the largest beneficiary of such regional funds from the EU budget) and included a provision in its pandemic recovery fund that links funding access to rule of law criteria. Due to the ongoing dispute, the EU has continued to delay the approval of €35.4 billion (approximately $38.9 billion) worth of grants and loans that Poland has applied for from the EU pandemic recovery fund.36

President Duda prepared legislation that abolished the Supreme Court disciplinary chamber in June 2022, but the EU asserted that the reforms and the structure replacing the chamber (the Chamber of Professional Responsibility) did not satisfy its concerns about impartiality and independence. In an effort to end the dispute and unlock the money from the pandemic recovery fund, Prime Minister Morawiecki introduced new legislation in December 2022 that would move judicial disciplinary matters to the country’s Supreme Court of Administration and make other changes that had been negotiated with the European Commission.37 Some members of the governing coalition oppose the changes, however, and President Duda has been cautious about the bill, stating that he would study its compliance with the constitution “but also take into account Poland’s sovereign right to shape the justice system in the way we, as Poles, want to.”38

In 2021, Poland’s constitutional tribunal ruled that sections of the Treaty on European Union that grant the EU the power to set standards for the independence and impartiality of judges in all EU member states are incompatible with Poland’s constitution. In challenging the principle of the primacy of EU law, some observers suggested that Poland may be on a track to leave the EU, although Law and Justice leaders have dismissed the notion.39 Surveys show that a large majority of the Polish public views EU membership as beneficial.40

The Economy Poland’s economy is among the most successful in Central and Eastern Europe. Starting with post-communist reform programs in the 1990s and continuing beyond Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004, pro-market policies and stable institutions have underpinned strong economic growth, an expanding private sector, and a steady increase in per capita gross domestic product (GDP).41

36 Piotr Buras, The Final Countdown: The EU, Poland, and the Rule of Law, European Council on Foreign Relations, December 14, 2022.

37 Jan Cienski, “Poland’s Rule of Law Legislation Moves Forward—But Fights Remain,” Politico Europe, January 13, 2023.

38 “Poland’s New Judicial Reform in Limbo After President Voices Concerns,” Reuters, December 15, 2022. 39 “Poland: Ruling Party Chief Says ‘There Will Be No Polexit’,” Deutsche Welle, September 15, 2021. 40 Aleksandra Rebelińska, “Ponad 80 proc. Polaków za pozostaniem w Unii. Sondaż Kantar,” Bankier.pl, September 12, 2021.

41 For background on Poland’s economic development since communism, see World Bank, Lessons from Poland, Insights for Poland: A Sustainable and Inclusive Transition to High-Income Status, 2017, and Marcin Piatkowski, How Poland Became Europe’s Growth Champion: Insights from the Successful Post-Socialist Transition, Brookings

Congressional Research Service

9

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic negatively affected the economy, but less so than in most other EU countries. The Polish economy contracted by 2.2% in 2020 (the EU as a whole contracted by 5.7%), before rebounding with 5.9% growth in 2021 and 3.8% growth in 2022.42 Economic growth is projected to slow to 0.5% in 2023, as Poland’s economy faces challenges from high inflation and encounters lower demand for exports due to a projected economic slowdown in Poland’s main EU trading partners (Germany is Poland’s largest trading partner). Economic growth is projected to reach 3.1% in 2024. Unemployment was low, at 3.2% as of late 2022.

Although Poland joined the EU in 2004, it is not a member of the Eurozone.43 Poland continues to use the złoty (PLN) as its national currency, and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2008-2012 dampened Polish enthusiasm for adopting the euro. Under the terms of its EU accession treaty, Poland is bound to adopt the euro as its currency eventually, but there is no fixed target date for doing so.

Alongside the party’s right-wing ideology, Law and Justice has implemented a left-wing socioeconomic policy focusing on redistribution and the reduction of income inequality. The government’s flagship Family 500+ program, which provides a monthly PLN500 (approximately $111) allowance per child, has proven especially popular with much of the electorate.44 The Law and Justice-led government also has lowered the retirement age and increased the minimum wage. With inflation driving a cost-of-living crisis ahead of the 2023 election, the government has provided support packages that subsidize high energy costs for households and enterprises.

Since 2015, the Law and Justice-led government has sought to “repolonize” the economy by using state-owned enterprises to acquire businesses in sectors such as banking, energy, and media. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, about half of Poland’s 20 largest companies are state-controlled.45

Defense Spending and Modernization According to NATO, Polish defense expenditures were an estimated 2.42% of GDP in 2022, approximately $17.8 billion.46 (NATO member states have agreed to a target of spending at least 2% of GDP on defense.) Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted Poland to adopt legislation in 2022 that increases defense spending to a minimum of 3% of GDP starting in 2023. The legislation also calls for Poland to more than double the size of its armed forces over the next five years, to 300,000 personnel.47 In January 2023, Prime Minister Morawiecki stated that he wants to increase defense spending to 4% of GDP.48

Weapons and equipment purchases from the United States play a central role in Poland’s military modernization program. Approximately $20 billion in U.S. Foreign Military Sales cases to Institution, February 11, 2015.

42 Economic statistics from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022. 43 The twenty EU member countries that use the euro as their common currency are collectively referred to as the Eurozone.

44 Anna Louie Sussman, “The Poland Model—Promoting ‘Family Values’ With Cash Handouts,” Atlantic, October 14, 2019.

45 Economist Intelligence Unit, Poland Country Report, February 2023. 46 NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures of NATO Countries (2014-2022), June 27, 2022. 47 Matilde Stronell, “Poland Unveils Record 2023 Defence Budget,” Janes, September 1, 2022. 48 Alexandra Fouché, “Poland Boosts Defence Spending Over War in Ukraine,” BBC News, January 30, 2023.

Congressional Research Service

10

Poland: Background and U.S. Relations

Poland were active as of late 2022. Sales since 2016 have included 32 F-35 aircraft, 250 M1A2 Abrams main battle tanks and 116 M1A1 Abrams main battle tanks, Patriot-3+ integrated air and missile defense systems, High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), advanced air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles, and Javelin anti-tank missiles. In September 2022, Poland requested U.S. government approval for the purchase of 96 AH-64E Apache attack helicopters, valued at approximately $7 billion.49 Poland also is leasing MQ-9 Reaper drones from the United States to assist in conducting reconnaissance along Poland’s eastern border.

In 2022, Poland also concluded deals for arms purchases from South Korea valued at approximately $12.3 billion. Purchases from South Korea include 189 K2 main battle tanks, 212 K9 self-propelled howitzers, 48 FA-50 light combat aircraft, and 288 K239 multiple rocket launchers. Under the agreements, Poland intends to produce K2s and K9s domestically, and eventually to have 1,000 K2s and nearly 700 K9s.50

Energy Security Prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Poland had taken steps to diversify its energy supplies away from Russian oil and natural gas, including by expanding pipeline connections with its European neighbors and constructing a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal that receives gas from a U.S. supplier. Poland also was a leading opponent and critic of the halted Nord Stream 2 pipeline that would have increased direct Russian gas supplies to Germany via the Baltic Sea.

Before 2022, Poland had imported 53% of its gas from Russia. In April 2022, Russia halted supplies of natural gas to Poland, ostensibly because of Poland’s refusal to comply with demands to pay for gas deliveries in rubles. Polish officials described the cutoff as a breach of contract but indicated they would be able to prevent shortages by importing gas (including LNG) from other suppliers.51 Baltic Pipe, a new gas pipeline connecting Poland’s gas infrastructure to Norwegian supplies via Denmark, became fully operational in November 2022.52 Also in November 2022, Poland announced a $20 billion deal with the U.S. company Westinghouse to build six nuclear reactors in Poland by the mid-2040s, with the first expected to come online in 2033.53 Overall, Poland remains the most coal-dependent country in the EU, with coal accounting for approximately 72% of Poland’s electricity generation in 2021.54 In February 2023, Russia halted the delivery of oil via pipeline to Poland. The chief executive officer of Polish refining company PKN Orlen stated that they had been prepared for the cutoff, had reduced Russian supplies to 10% of Poland’s oil imports, and would be able to compensate with other suppliers.55

Successive U.S. presidential ) and CIA World Factbook.

Domestic Overview

Political Dynamics

The government of Poland is led by Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki of the conservative-nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS). Law and Justice won the October 2015 parliamentary election with 37.6% of the vote, giving the party 235 of the 460 seats in the Sejm (lower house of parliament).3 This was the first time since the end of communist rule in 1989 that a single party secured an absolute majority in parliament. Law and Justice had spent the previous eight years in opposition after leading the government from 2005 to 2007. The center-right Civic Platform (PO) party, which led the government of Poland from 2007 to 2015, came in second place in the 2015 election with 24.1% of the vote, dropping from 207 to 138 seats in the Sejm. The next parliamentary election is due to take place in October or November 2019.4

Poland's president is Andrzej Duda, who was the Law and Justice-backed candidate in the May 2015 presidential election. Law and Justice gained momentum five months prior to the parliamentary election with Duda's unexpected victory over the Civic Platform-supported incumbent. The president, who serves a five-year term, is Poland's head of state and resigns party membership upon election. The president exercises functions including making formal appointments, overseeing the country's executive authority, influencing legislation, representing the state in international affairs, and acting as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Jarosław Kaczyński is head of Law and Justice and a member of the Sejm. Despite his holding no formal post in the government, many observers assert that Kaczyński remains the most powerful politician in Poland who, as party chairman, exerts considerable influence behind the scenes.5 Jarosław Kaczyński co-founded Law and Justice with his twin brother Lech in 2001. Lech Kaczyński was the president of Poland from 2005 to 2010, when he died in an airplane crash in Russia that also killed 95 other people, including many high-ranking Polish officials.

|

|

|

A number of factors contributed to the 2015 election outcome. Law and Justice tapped into public unease over surging non-European migration to Europe by criticizing Civic Platform's willingness to accept migrants under an EU relocation plan. Law and Justice also appeared to gain support by advocating increased public spending for social support programs benefitting families with children, lower-income citizens, and the elderly. During the campaign, the party argued that the benefits of Poland's economic development had fallen unevenly across society and failed to reach many ordinary citizens.

At the same time, observers believe there was a sense of voter fatigue toward Civic Platform and, relatedly, public discontent with the country's political establishment. Civic Platform was damaged by a scandal in which secretly recorded conversations led to the resignation of several government officials in 2015. A changeover in leadership with the 2014 appointment of then-Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who co-founded Civic Platform, as President of the European Council in Brussels was also a factor in the party's decline.

More broadly, the 2015 election and its aftermath appeared to confirm the observation that Polish politics have become characterized by an entrenched social divide between national-oriented social conservatives, represented by Law and Justice, and Western-oriented liberals, represented by Civic Platform.6

Since taking office, the Law and Justice-led government has implemented numerous reforms that have proved contentious and raised tensions with the EU as well as domestic opponents; these reforms also have elicited some concern from the United States. Many members of Law and Justice maintain that Poland's post-communist development has been based in part on flawed institutions and values, and Law and Justice leaders interpreted the 2015 election results as a mandate to enact substantial reforms to the country's political system and public institutions. Some argue, therefore, that the party seeks to reduce the influence on national institutions of so-called liberal and secular "European" values and to recast those institutions in ways that promote what the party and its supporters view as traditional national-patriotic values, including close ties with the Catholic Church. Law and Justice also fiercely condemns the communist era and those associated with it, and the party holds a nationalist-oriented worldview that includes enduring suspicion toward Russia and unresolved tensions with Germany.

The results of regional elections in October 2018 and European Parliament (EP) elections in May 2019 indicate that support for the Law and Justice party has held relatively steady since Poland's 2015 election.

In the 2018 regional elections, Law and Justice won 34% of the vote and the most seats in 9 out of the country's 16 regional assemblies (with an absolute majority in 6). Previously, Law and Justice controlled one regional government.7Law and Justice did well among more rural and less affluent voters, while a coalition of opposition parties including Civic Platform did well among more liberal and urban voters. Law and Justice won 4 out of 107 municipal elections. The opposition won mayoral races in Poland's largest cities, including Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, and Gdańsk.8- In the May 2019 EP elections, Law and Justice came in first place, winning 27 seats with approximately 45% of the Polish vote. A coalition of opposition parties including Civic Platform won 22 seats with approximately 38% of the vote.9

Despite numerous public protests over the past three years against the government's reforms, critics observe that opposition parties including Civic Platform have struggled to offer an effective alternate message.10 Support for Law and Justice, meanwhile, appears to have been mostly unaffected by controversy over its domestic reforms or by a series of corruption scandals reported in late 2018 and early 2019.11 Given its close association with the Catholic Church, the party came under pressure prior to the EP election with the release of a documentary film about the sexual abuse of children by Polish priests and subsequent efforts to cover up those crimes.12 After the film was released, the government adopted increased prison sentences for those convicted of sexual abuse of a child.

Controversial Reforms and Tensions with the EU

The most prominent and controversial set of reforms undertaken by the Law and Justice-led government concerns the judicial system. Critics charge that several moves enacted since late 2015 subvert institutional checks and balances, undermine judicial independence and the rule of law, and place the country's courts under political control.13 The reforms have significantly increased executive and parliamentary powers to select and remove judges, decisions that previously were determined internally by professional bodies within Poland's judiciary. Law and Justice leaders, who blamed the courts for blocking many of the party's legislative priorities when it previously led the government (2005-2007), maintain that the judicial system needed extensive reform because it was slow and inefficient, judges were not properly re-vetted after the transition from communism to democracy, and procedures for selecting new judges lacked fairness and accountability.

Beyond the judicial system, a law adopted in 2016 granted the government the power to hire and fire management of public broadcasting stations, a function previously performed by an independent media supervisory committee. The government maintained that the move was needed to correct political bias and restore balance in the public media. Critics argue that it compromises the independence of state media and relegates it to publicizing the government's official narrative.14 The government also has cut public funding to some civil society organizations, particularly those supporting migrants and refugees. Critics charged that this move was intended to stifle opponents of government policies.15

In 2018, Poland adopted reforms to the country's electoral system. The government asserted that these changes, expected to take effect after the 2019 parliamentary elections, would increase fairness and transparency. Opponents argued that they would politicize the administration of elections and were intended to advantage Law and Justice.16 The reforms replace seven of the nine members (currently all judges) of the National Electoral Commission (responsible for conducting and overseeing all elections in Poland) with new members chosen by the Sejm according to party proportion. The reforms also call for the National Electoral Commission to appoint new local election commissioners, who are no longer required to be independent of political parties.

Overall, domestic political opponents and outside observers have expressed concern that the actions taken by the government amount to a rollback of Poland's democracy and a program to construct an "illiberal" state.17 Law and Justice leaders and supporters dispute this portrayal, alleging that their political opponents have crafted this narrative in an attempt to undo the results of the 2015 election and block the government's ability to implement its agenda.

In 2016, the European Commission (the EU's executive institution) launched an inquiry into the effects of the judicial and public media reforms on the rule of law in Poland. The EU subsequently set a series of deadlines for Poland to respond to recommended amendments that would address EU concerns about the ability of the executive and legislature to interfere with the independence of the judiciary. In 2016 and 2017, the Polish government consistently rejected the EU's recommended measures, objecting that the EU was interfering with the country's sovereignty and did not fully understand the Polish legal system. In December 2017, the European Commission recommended the EU move toward imposing an "Article 7" sanction, under which Poland's voting rights in the Council of the EU could be suspended.18 The measure is unlikely to be enacted, however; Hungary, which has similar Article 7 issues with the EU, has said it would veto the imposition of such a sanction against Poland, which requires unanimity in the Council.

The EU also has been developing plans to link the amount of regional funding allocated to Poland (and other countries, such as Hungary) to judicial independence and rule-of-law standards in the next EU budget framework.19 Poland is the largest beneficiary of funding from the EU budget. In the EU's 2014-2020 budget framework, €106 billion (approximately $120 billion) was allocated to Poland, with the majority of EU support funding regional and municipal infrastructure development.20

In October 2018, the Polish government complied with a ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ordering the suspension of a law that allowed the president to decide whether to retire Supreme Court judges over the age of 65. (The law affected 28 of 72 judges sitting on the appellate panels of the country's Supreme Court at the time it came into effect in July 2018.)21 The episode marked the first time Law and Justice backtracked on any major element of its controversial reform program. In April 2019, the European Commission launched a new complaint alleging that Poland's process for disciplinary proceedings against judges, enacted in 2017, infringes on EU requirements for judicial independence from political control.22

Migration policy has been another source of tension between Poland and the EU. Poland has been a leading opponent of EU policies attempting to relocate migrants and refugees throughout the member states. In 2015, the Civic Platform-led government voted to approve a mandatory EU relocation plan, agreeing to take in approximately 4,600 migrants from outside the EU. The agreement became a significant campaign issue in Poland's 2015 election, with debates about the migration crisis highlighting divisions in Polish society and politics.

Law and Justice strongly criticized approval of the plan, and after the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, the incoming Law and Justice-led government indicated that respecting the EU plan was not politically possible. Poland subsequently joined Hungary and the Czech Republic in defying the EU by refusing to the implement the plan, arguing that it infringed on their national sovereignty and that immigration policy was not a competence of the EU. In December 2017, the European Commission referred the three countries to the ECJ over their failure to implement the relocation plan.

Despite these tensions, Jarosław Kaczyński has stated that Law and Justice does not intend to take Poland out of the EU. Surveys show that a large majority of the Polish public views EU membership as beneficial.23

The Economy

Poland's economy is among the most successful in Central Europe. Starting with post-communist reform programs in the 1990s and continuing beyond Poland's accession to the EU in 2004, pro-market policies and stable institutions have underpinned strong economic growth, an expanding private sector, and a steady increase in per capita gross domestic product (GDP).24 Poland's economy was hurt by the 2008 global financial crisis and the ensuing Eurozone crisis but was less affected than most other EU members. The Polish economy was the only European economy to sustain growth in 2008-2009, and Poland avoided a domestic banking crisis.

Although Poland joined the EU in 2004, it is not a member of the Eurozone.25 Poland continues to use the złoty (PLN) as its national currency, and the Eurozone debt crisis that began in Greece in 2009 dampened Polish enthusiasm for adopting the euro. Under the terms of its EU accession treaty, Poland is bound to adopt the euro as its currency eventually, but there is no fixed target date for doing so.

Economic growth in Poland remains high compared to most other EU members. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), growth averaged 3.75% per year over the period 2014-2017 and reached 5.1% in 2018.26 Unemployment is low, decreasing from 10.3% in 2013 to an expected 3.6% in 2019. Forecasts project growth of 3.8% in 2019 and an average of 2.9% annually over the period 2020-2023.

The main drivers of the Polish economy recently have consisted of strong private consumption, investment derived from EU funding, and increased demand for exports. (Nearly 80% of Poland's exports are to other EU countries, with more than a quarter to Germany.27) Near-term risks to growth include a potential reduction in EU funding in the next EU budget framework (2021-2027) and a broader economic slowdown in the EU that could decrease demand for Polish exports.

After the Civic Platform-led government of 2011-2015 sought to consolidate public finances through tax increases and entitlement cuts, the Law and Justice-led government has taken steps to loosen fiscal policy in order to benefit lower-income households and families, encourage higher birth rates, and appeal to older voters.28 Under the "Family 500+" program, families are eligible to receive a tax-free monthly subsidy of PLN 500 (approximately $132) per month for their second child and every subsequent child, with lower-income families eligible starting with their first child.29 Additionally, the government reversed its predecessor's reform raising the retirement age to 67, returning it to 65 for men and 60 for women. Similar to EU-wide averages, the median age in Poland was approximately 38 years old in 2012 and is expected to be 51 years old in 2050.30 Declining birth rates and net emigration have been the main factors in demographic change in Poland. The aging of the country's population is expected to have challenging implications for Poland's health care and retirement systems.31

Concerns that increased government spending on child support and pensions (as well as on planned increases to defense spending) could negatively affect Poland's public finances have largely been balanced by the country's strong economic growth. The budget deficit was 0.6% of GDP in 2018 and is expected to be 2.2% of GDP in 2019. Public debt was approximately 43.6% of GDP in 2018, according to the IMF. (EU rules stipulate that deficits remain below 3% of GDP and that debt remain below 60% of GDP).

Defense Modernization

Poland has repeatedly been invaded by external powers throughout its history. These experiences continue to shape Poland's security perceptions. Territorial defense is the core mission of the Polish military, and Poland's current security strategy is focused primarily on deterring potential Russian aggression. Armed forces modernization, NATO membership, and close ties with the United States are the main components of this strategy. Poland has sought to build a multilayered security policy around this foundation, with participation in EU defense initiatives and cooperation with regional partners such as the Nordic and Baltic countries, the Visegrád Group, and the Bucharest Nine.32

Poland has the ninth-largest army in NATO, with 61,200 active personnel. In all, Poland has 117,800 total active military personnel across all branches of the armed forces.33 Poland ended military conscription in 2009. Poland is one of seven NATO countries meeting the alliance's recommendation of allocating 2% of GDP for defense spending. According to NATO, Polish defense expenditures were 2.05% of GDP ($12.156 billion) in 2018.34 The Polish government plans to raise defense spending to 2.1% of GDP in 2020 and to gradually increase defense spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2030.35

In 2016, the Polish Defense Ministry announced a revised "Technical Modernization Plan" prioritizing air defense, navy, cybersecurity, tanks and armored vehicles, and territorial defense capabilities. From 2017 to 2022, the plan called for approximately $14.5 billion in spending on weapons and equipment acquisition, including new air defense systems, helicopters, UAVs, coastal defense vessels, minesweeper ships, and submarines.36 In February 2019, the defense ministry announced that it had revised and expanded the plan to include approximately $49 billion in spending on armed forces modernization over the period of 2017-2026. Priorities in the revised plan include short-range anti-aircraft missiles, attack helicopters, submarines, cybersecurity, and the acquisition of fifth-generation combat aircraft.37

While foreign purchases continue to play a large role, the Polish government has linked the defense modernization program with efforts to develop Poland's defense-industrial base, seeking contracts and partnerships that include local manufacturing and technology transfers.

Another initiative of the Law and Justice-led government has been the establishment of a new territorial defense force, intended to eventually consist of 53,000 volunteers trained and equipped for tasks such as critical infrastructure protection and unconventional warfare.38

Relations with the United States

Since the end of the Cold War, Poland and the United States have had close relations. The United States strongly supported Poland's accession to NATO in 1999. Warsaw has been an ally in global counterterrorism efforts and contributed large deployments of troops to both the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq and the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan. Links between the United States and Poland are further anchored by extensive cultural ties; approximately 9.6 million Americans are of Polish heritage.

The Law and Justice-led government has sought to cultivate ties with the Trump Administration. In a visit to the United States in September 2018, Polish President Duda suggested that a permanent U.S. military base in Poland might be named "Fort Trump."39 On February 13-14, 2019, Poland and the United States co-hosted the "Ministerial to Promote a Future of Peace and Security in the Middle East," a conference attended by Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Michael Pompeo.40

President Trump earlier delivered a speech in Warsaw on July 6, 2017. The president's remarks on NATO, Russia, U.S.-Polish ties, and Poland's resilience throughout history were well received by many Polish observers, and especially by the Polish government and its supporters. At the same time, critics asserted that the tone of the President's visit, during which he apparently did not raise concerns about Poland's domestic policies, emboldened the government to move ahead with controversial new judicial bills shortly afterward.41

While relations between Poland and the United States remain largely positive, there have been points of tension over the past several years. Following President Trump's Warsaw speech, the U.S. State Department released a statement expressing concern about judicial independence and the rule of law in Poland.42 Some Members of Congress also have expressed concerns about the Polish government's judicial and media reforms. In February 2016, for example, Senators McCain, Durbin, and Cardin co-authored a letter urging Poland to "recommit to the core principles of the [Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe] and the EU, including the respect for democracy, human rights, and rule of law."43

U.S. officials (along with many of their European and Israeli counterparts) objected to controversial Holocaust-related legislation (amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance) passed by Poland's parliament and signed by President Duda in early 2018.44 The legislation initially criminalized attributing responsibility for Nazi crimes to the Polish state or nation, potentially punishable by a prison sentence of up to three years, with exemptions for art and academic research. Under continued international pressure, the Polish government amended the law in June 2018, making violations a civil (rather than criminal) offense.45

In recent years, Polish officials have objected to instances in which commentators and press articles have referred to Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps on Polish soil as "Polish death camps," preferring such phrasing as "Nazi concentration camp in German-occupied Poland" (President Obama apologized after using the term "Polish death camp" in 2012).46 Scholars agree that the term "Polish death camp" is inaccurate and misleading and that the Polish state did not collaborate in the Nazi genocide against Jews.47 At the same time, historical research has documented instances in which some Poles committed atrocities against Jews during and after World War II. Critics fear the 2018 legislation may serve to stifle debate about such issues and whitewash the culpability of individual Poles in such cases.

In November 2018, a leaked letter from U.S. Ambassador Georgette Mosbacher to Prime Minister Morawiecki reportedly angered some Polish officials by raising concerns about media freedom.48 The Polish government reportedly had contemplated prosecuting the Polish television station TVN, which is owned by U.S. company Discovery Communications, after it aired footage alleging to show a Polish neo-Nazi group celebrating Adolf Hitler's birthday.

Following the murder of Gdańsk Mayor Paweł Adamowicz in January 2019 by a mentally ill assailant, Representative Marcy Kaptur, a co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on Poland, expressed concern about whether Poland's divided political environment could have played a role in motivating the perpetrator.49 Adamowicz was a well-known liberal critic of the Law and Justice-led government.

In February 2019, Representative Kaptur introduced the Paweł Adamowicz Democratic Leadership Exchange Act of 2019 (H.R. 1270), a bill that would reauthorize the United States-Poland Parliamentary Exchange Program.

Defense Relations

Defense cooperation between Poland and the United States is especially close and extensive. Poland has been a focus of U.S. and NATO efforts to deter potential Russian aggression in the region. In the wake of Russia's aggression against Ukraine starting in 2014, Polish officials reemphasized their wish to permanently base U.S. forces on their territory, despite concerns by some U.S. and European officials that doing so could violate the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act. 50 In May 2018, the Polish government released a proposal under which it would contribute $2 billion toward establishing such a base.51 In a House Armed Services Committee hearing on March 13, 2019, acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs Kathryn Wheelbarger stated that the related negotiations with Poland were under way.52 Section 1280 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232) required the Secretary of Defense to report to the congressional defense committees on the "feasibility and advisability" of permanently stationing U.S. forces in Poland by March 2019. (With discussions between Poland and the U.S. Administration still in progress, the report had not been received as of June 2019.) As part of the United States' missile defense for Europe, an "Aegis-Ashore" site with radar and 24 SM-3 missiles is to become operational in Poland in 2020. Russian officials have characterized the establishment of U.S. missile defense installations in Europe as a "direct threat to global and regional security."53

Under the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), launched in 2014 (originally called the European Reassurance Initiative), the United States has bolstered security in Central and Eastern Europe with an increased rotational military presence, additional exercises and training with allies and partners, improved infrastructure to allow greater responsiveness, enhanced prepositioning of U.S. equipment, and intensified efforts to build partner capacity for newer NATO members and other partners. Approximately 6,000 U.S. military personnel are involved in the associated Atlantic Resolve mission at any given time, with units typically operating in the region under a rotational nine-month deployment.54

The United States has not increased its permanent troop presence in Europe (currently about 67,000 troops, including two U.S. Army Brigade Combat Teams, or BCTs), but it has rotated additional forces into the region, including nine-month deployments of a third BCT based in the United States.55 The BCT is based largely in Poland, with units also conducting training and exercises in the Baltic states, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania. A combat aviation brigade supports the activities of the BCT.56 The 4th Infantry Division Mission Command Element, based in Poznań, Poland, acts as the headquarters overseeing rotational units.

Following a meeting between President Trump and President Duda in Washington, DC, on June 12, 2019, President Trump announced that an additional 1,000 troops would be added to the rotational U.S. deployments in Poland. The additional troops are expected to come from units based in Germany.57 The two sides also announced plans for the U.S. military to expand its logistical, administrative, and training infrastructure in Poland, boost the presence of special operations forces, and establish a squadron of aerial reconnaissance drones.58

At the 2016 NATO Summit in Warsaw, the alliance agreed to deploy multinational battle groups (approximately 1,100 troops each) to Poland and the three Baltic countries. These "enhanced forward presence" units are intended to deter Russian aggression by acting as a "tripwire" that ensures a response from the entire alliance in the event of a Russian attack. The United States is leading the multinational battalion based in Orzysz, Poland.59 NATO continues to resist calls to deploy troops permanently in countries that joined after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Accordingly, the enhanced NATO presence has been referred to as "continuous" but rotational.

In recent years, Poland has made a number of significant defense purchases from the United States, and numerous elements of Poland's military equipment modernization plans are of interest and relevance to U.S. defense planners and the U.S defense industry:

- At a February 2019 press conference unveiling the updated Technical Modernization Plan for the Polish armed forces, Polish Defense Minister Mariusz Błaszczak indicated that the procurement of fifth-generation fighter aircraft was a top priority.60 In May 2019, Poland send a formal letter of request to the United States for the purchase of 32 F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, made by Lockheed Martin.61