Harbor Dredging: Issues and Historical Funding

Changes from June 14, 2019 to November 6, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Congress is debating whether to support increased funding for dredging to better maintain harbor channel depths and widths. A bill approved by the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee passed by the House (H.R. 2440) seeks to boost dredging activity by utilizing more of the collections from a port tax levied to fund harbor maintenance. However, it is not clear howwhether the additional funding would changeincrease the volume of material dredged from U.S. harbors, as limits on the U.S. dredge fleet and environmental restrictions on when dredging can be performed, among othera variety of factors, affect the cost and performance of harbor dredging.

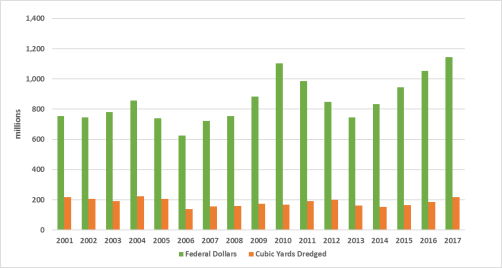

Data from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), the agency responsible for federal harbor maintenance, reveal that an increase in inflation-adjusted spending on routine maintenance dredging from 2001 to 2017 was not matched by an increase in the amount of material dredged (Figure 1). Over the five-year period from 2013 to 2017, spending on routine maintenance dredging was 22% higher (adjusted for inflation) than during the 2001-2005 period, but the actual amount of material dredged was 15% less. These data cover only routine dredging to maintain navigation channel depths and widths, excluding unplanned work such as dredging after hurricanes, which typically costs more. New construction dredging to expand shipping channels beyond existing authorized dimensions, which also is typically more costly than maintenance dredging, is also excluded from the data.

(adjusted to 2017 dollars) |

|

(fiscal years) Source: USACE Navigation Data Center, "Actual Dredging Cost Data for 1963-2018." |

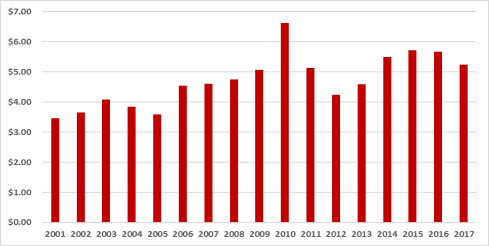

Looked at another way (Figure 2), the average annual cost per cubic yard of dredged material for regular harbor maintenance, adjusted for inflation, has risen from $3.46 in 20011.74 in 1970 to $5.24 in 201777 in 2018, an increase of 51% from 2001.

|

Figure 2. Cost Per Cubic Yard for ( |

|

|

Source: |

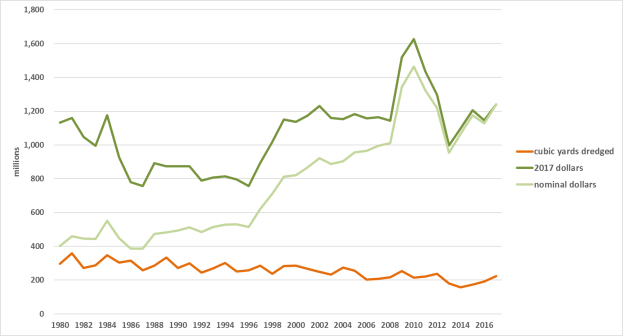

When including all maintenance dredging (i.e., unplanned work) and new construction dredging, USACE data show (Figure 3) a declining trend in the amount of material dredged since 1980 despite increases in federal funding.

|

|

Source: CRS, using data from USACE personal communication, June 8, 2019.

|

Multiple factors are believed to be causing recent cost increases—have contributed to the increased cost per cubic yard: changes in dredged material disposal, mobilization costs, cost inflation of inputs (fuel and steel), environmental factors, and a shortage of dredging firms—but therelatively little competition for dredging contracts. The relative significance of each is unknownunclear. Old disposal sites can be full and newer ones more distant. Unknown is whether enactment of P.L. 104-303 (§§201, 207, 217) in 1996 led to more federal dollars being used to build and maintain disposal facilities, treat contaminated sediments, or transport dredge spoils further for beneficial uses. Mobilization and demobilization of the several vessels typically required for a dredge project can be more than one-third of project cost in the United States. In addition to changes in the cost of fuel, steel, and labor (accounted for in Figure 1 and Figure 2 above by inflation adjustments), cost of dredged material disposal and compliance with environmental protection requirements may be increasing. For example, totransport dredged material further for beneficial uses such as restoring wetlands and beaches, and paying for disposal tipping fees. One dredge firm states it has performed many contracts that have required more nondredge work (such as upland disposal and environmental remediation) than dredging. The largest domestic marine dredge firm states that upland disposal can be as much as 90% of total project cost. Mobilization and demobilization of the several vessels typically required for a dredge project can be more than one-third of project cost. To protect endangered species such as sea turtles, dredging firms might have to employ fishing trawlers or restrict dredging and spoilsdredged material disposal to winter months when bad weather raises costs. Table 1 shows wide variation among USACE districts in the unit cost of dredging

Costs per cubic yard vary greatly among USACE districts, indicating that local circumstances are relevant (Table 1).

Table 1. Average Unit Cost of Dredging by Selected USACE District

Contracts(contracts >100,000 cubic yards, 2014 to 2018

|

USACE District |

Cubic Yards Dredged |

Cost per Cubic Yard |

|

San Francisco |

5,398,939 |

$ 24.27 |

|

New York |

11,908,916 |

$ 23.17 |

|

Philadelphia |

6,037,757 |

$ 19.93 |

|

Jacksonville |

22,447,059 |

$ 14.86 |

|

Los Angeles |

1,283,153 |

$ 13.20 |

|

Detroit |

3,064,310 |

$ 9.40 |

|

Alaska |

5,550,057 |

$ 8.58 |

|

Savannah |

37,140,202 |

$ 6.52 |

|

Portland (OR) |

30,983,332 |

$ 5.29 |

|

Galveston |

76,646,189 |

$ 3.80 |

|

New Orleans |

105,894,803 |

$ 2.62 |

Source: CRS, using USACE Dredging Information Statistics at https://publibrary.planusace.us/#/series/Dredging%20Information.

Congress, per 33 U.S.C. §622, hasIn 1978 (P.L. 95-269), Congress directed the USACE to contract out dredging work to private firms whenever possible. A handful of firms bid for USACE dredging projects; foreign in order to expand the private dredging fleet and encourage increased competition. Foreign firms and foreign-built dredges are prohibited prohibited in U.S. waters. While many firms bid for USACE dredging contract data projects, most individual projects draw few bidders. USACE data indicate that of the 701 dredging contracts the agency awarded from 2014 to 2018, 295 (42%) were sole-bid contracts and 178 (25%) attracted two bidders.

Hopper dredges are generally preferred for dredging coastal harbors because they can work in rough water and can more efficiently transport dredge spoils to disposal sites. The four U.S. firms that own the 15 hopper dredges in the U.S. fleet accounted for 59% of the USACE's dredging contracts awarded in dollar value and 32% of the total number of contracts awarded from 2014 to 2018. The USACE owns four hopper dredges employed for emergency work or when private industry submits bids much higher than the USACE's estimated cost. In 1978 (P.L. 95-269), Congress reduced the USACE-owned fleet in hopes of increasing the private fleet and competition among dredging firms.

According to the USACE, hopper dredges are generally the most efficient vessels for dredging coastal harbors. Four firms own 99% of U.S. hopper dredging capacity and accounted for 59% of all USACE dredging contracts by dollar value from 2014 to 2018. This private hopper dredge fleet is relatively old, with 11 of the 15 vessels in service for more than 20 years. The USACE owns four hopper dredges employed for emergency work or when submitted bids are more than 25% above the USACE's estimated cost. A study for the State of Louisiana, published in 2011, found dredging costs have trended downward in foreign markets. One reason foreign firms may have a cost advantage is their use of semi-submersible heavy-lift ships to transport their dredge fleets. U.S. dredging firms would be required by law to use a U.S.-built heavy-lift ship for transport, but none exist. The need to tow individual vessels to job sites likely raises U.S. firms' costs.The USACE is unable at times to schedule as much dredging as desired due to a lack of dredges. Compared to the fleets of the four European dredging firms considered world leaders, the U.S. fleet of hopper vessels is smaller and older. Each of the four European firms has a hopper fleet whose capacity is three to four times that of the entire U.S. fleet. According to an advocate for foreign investors in the United States, European dredging firms "could complete the U.S. projects for half the estimated cost and a third of the time." One analysis finds dredging costs have trended downward in foreign markets. Foreign firms use heavy-lift ships to transport their dredge fleets. U.S. dredging firms would be required by law to use a U.S.-built heavy-lift ship for transport, but none exist; U.S. firms therefore tow individual vessels to jobsites and stage equipment in various coastal locationsHowever, the accuracy of the USACE's figures is disputed. A 2015 Government Accountability Office audit found the USACE dredging contracts database to be incomplete and contain inaccurate information, but a dredging firm contends the USACE maintains the most complete budget and cost data.