Navy Constellation (FFG-62) and FF(X) Class Frigate Programs: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from May 29, 2019 to June 7, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background

Background and Issues for Congress

Updated June 7, 2019

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

R44972

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Summary

The FFG(X) program is a Navy program to build a class of 20 guided-missile frigates (FFGs).

The Navy wants to procure the first FFG(X) in FY2020, the next 18 at a rate of two per year in

FY2021-FY2029, and the 20th in FY2030. The Navy’s proposed FY2020 budget requests

$1,281.2 million for the procurement of the first FFG(X). The Navy’s FY2020 budget submission

shows that subsequent ships in the class are estimated by the Navy to cost roughly $900 million

and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Navy's Force of Small Surface Combatants (SSCs)

- U.S. Navy Frigates in General

- FFG(X) Program

- Meaning of Designation FFG(X)

- Procurement Quantity and Schedule

- Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing

- Procurement Cost

- Acquisition Strategy

- Competing Industry Teams

- Program Funding

- Issues for Congress

- FY2020 Funding Request

- Cost, Capabilities, and Growth Margin

- Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities

- Balance Between Cost and Capabilities

- Number of VLS Tubes

- Growth Margin

- Parent-Design Approach

- Cost, Schedule, and Technical Risk

- Procurement of LCSs in FY2020 as Hedge against FFG(X) Delay

- Potential Industrial-Base Impacts of FFG(X) Program

- Shipyards

- Supplier Firms

- Number of FFG(X) Builders

- Potential Change in Navy Surface Force Architecture

- Legislative Activity for FY2020

- Summary of Congressional Action on FY2020 Funding Request

Figures

Tables

Summary

The FFG(X) program is a Navy program to build a class of 20 guided-missile frigates (FFGs). The Navy wants to procure the first FFG(X) in FY2020, the next 18 at a rate of two per year in FY2021-FY2029, and the 20th in FY2030. The Navy's proposed FY2020 budget requests $1,281.2 million for the procurement of the first FFG(X). The Navy's FY2020 budget submission shows that subsequent ships in the class are estimated by the Navy to cost roughly $900 million each in then-year dollars.

each in then-year dollars.

The Navy intends to build the FFG(X) to a modified version of an existing ship design—an

approach called the parent-design approach. The parent design could be a U.S. ship design or a

foreign ship design. At least four industry teams are reportedly competing for the FFG(X)

program. Two of the teams are reportedly proposing to build their FFG(X) designs at the two

shipyards that have been building Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) for the Navy—Austal USA of

Mobile, AL, and Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WI. The other two teams are

reportedly proposing to build their FFG(X) designs at General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works, of

Bath, ME, and Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding of Pascagoula, MS.

On May 28, 2019, it was reported that a fifth industry team that had been interested in the

FFG(X) program had informed the Navy on May 23, 2019, that it had decided to not submit a bid

for the program. This fifth industry team, like one of the other four, reportedly had proposed

building its FFG(X) design at F/MM.

The Navy plans to announce the outcome of the FFG(X) competition in July 2020.

The FFG(X) program presents several potential oversight issues for Congress, including the

following:

-

whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy

'’s FY2020 funding request for the -

whether the Navy has appropriately defined the cost, capabilities, and growth

-

the Navy

'’s intent to use a parent-design approach for the FFG(X) program rather - cost, schedule, and technical risk in the FFG(X) program;

-

whether any additional LCSs should be procured in FY2020 as a hedge against

-

the potential industrial-base impacts of the FFG(X) for shipyards and supplier

-

whether to build FFG(X)s at a single shipyard, as the Navy

'’s baseline plan calls -

the potential impact on required numbers of FFG(X)s of a possible change in the

Navy'Navy’s surface force architecture.

Introduction

This report provides background information and discusses potential issues for Congress regarding the Navy's FFG(X) program, a program to procure a new class of 20 guided-missile frigates (FFGs). The Navy's proposed FY2020 budget requests $1,281.2 million for the

Congressional Research Service

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Navy’s Force of Small Surface Combatants (SSCs) ................................................................. 1

U.S. Navy Frigates in General .................................................................................................. 2

FFG(X) Program ....................................................................................................................... 3

Meaning of Designation FFG(X) ........................................................................................ 3

Procurement Quantity and Schedule ................................................................................... 3

Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing ............................................................................. 5

Procurement Cost ................................................................................................................ 6

Acquisition Strategy............................................................................................................ 7

Competing Industry Teams ................................................................................................. 9

Program Funding .............................................................................................................. 10

Issues for Congress ........................................................................................................................ 10

FY2020 Funding Request ....................................................................................................... 10

Cost, Capabilities, and Growth Margin ................................................................................... 10

Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities .................................................................. 11

Balance Between Cost and Capabilities............................................................................. 11

Number of VLS Tubes ....................................................................................................... 11

Growth Margin.................................................................................................................. 12

Parent-Design Approach ......................................................................................................... 12

Cost, Schedule, and Technical Risk ........................................................................................ 13

Procurement of LCSs in FY2020 as Hedge against FFG(X) Delay ........................................ 13

Potential Industrial-Base Impacts of FFG(X) Program........................................................... 14

Shipyards .......................................................................................................................... 14

Supplier Firms................................................................................................................... 15

Number of FFG(X) Builders ................................................................................................... 19

Potential Change in Navy Surface Force Architecture ............................................................ 20

Legislative Activity for FY2020 .................................................................................................... 20

Summary of Congressional Action on FY2020 Funding Request .......................................... 20

FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act (H.R. 2968) ...................................................................... 21

House ................................................................................................................................ 21

Figures

Figure 1. Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) Class Frigate ..................................................................... 2

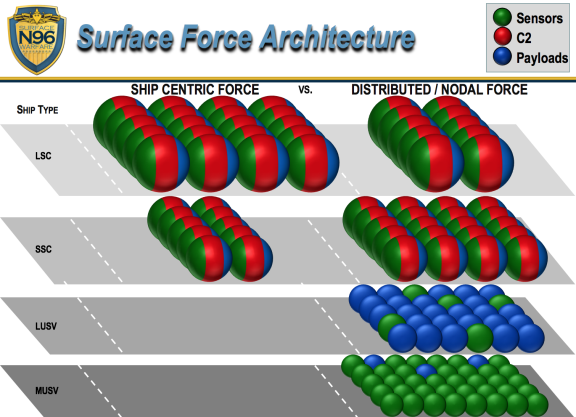

Figure 2. Navy Briefing Slide on Surface Force Architecture ........................................................ 4

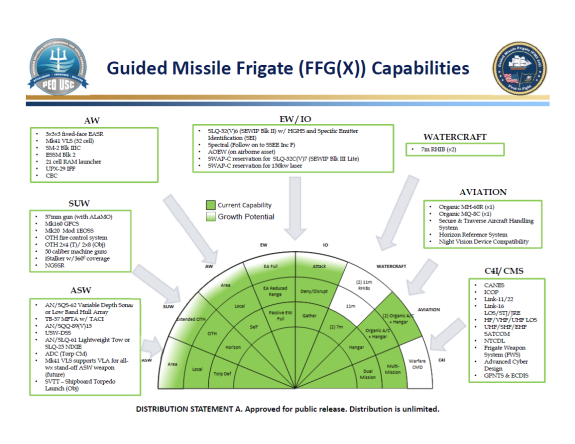

Figure 3. Navy Briefing Slide on FFG(X) Capabilities................................................................... 6

Tables

Table 1. Industry Teams Reportedly Competing for FFG(X) Program ........................................... 9

Table 2. FFG(X) Program Funding ............................................................................................... 10

Table 3. Congressional Action on FY2020 FFG(X) Program Funding Request ........................... 21

Congressional Research Service

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Appendixes

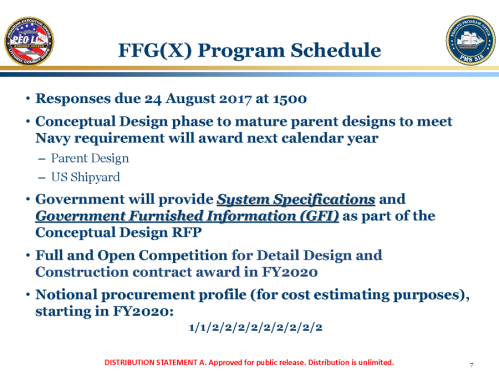

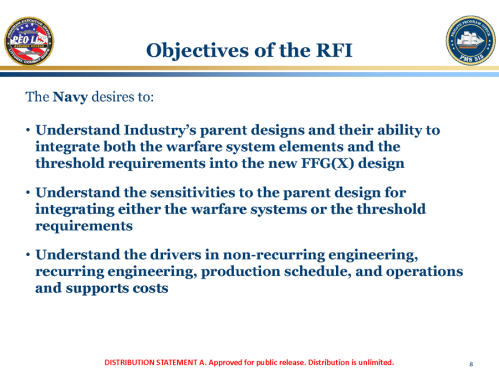

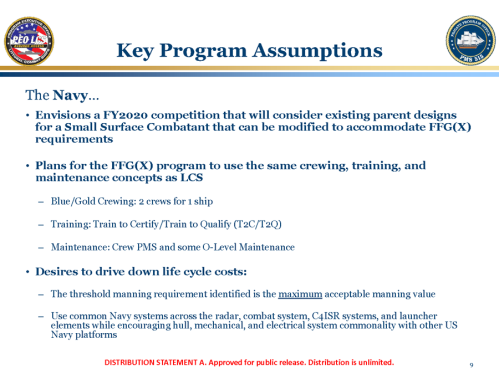

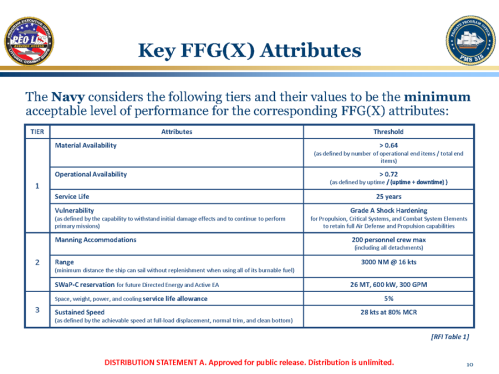

Appendix A. Navy Briefing Slides from July 25, 2017, FFG(X) Industry Day Event.................. 23

Appendix B. Competing Industry Teams ...................................................................................... 29

Contacts

Author Information........................................................................................................................ 31

Congressional Research Service

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Introduction

This report provides background information and discusses potential issues for Congress

regarding the Navy’s FFG(X) program, a program to procure a new class of 20 guided-missile

frigates (FFGs). The Navy’s proposed FY2020 budget requests $1,281.2 million for the

procurement of the first FFG(X).

procurement of the first FFG(X).

The FFG(X) program presents several potential oversight issues for Congress. Congress's ’s

decisions on the program could affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the

shipbuilding industrial base.

This report focuses on the FFG(X) program. A related Navy shipbuilding program, the Littoral

Combat Ship (LCS) program, is covered in detail in CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat

Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. Other CRS

reports discuss the strategic context within which the FFG(X) program and other Navy

acquisition programs may be considered.1

Background

Navy'1

Background

Navy’s Force of Small Surface Combatants (SSCs)

In discussing its force-level goals and 30-year shipbuilding plans, the Navy organizes its surface

combatants into large surface combatants (LSCs), meaning the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers,

and small surface combatants (SSCs), meaning the Navy'’s frigates, LCSs, mine warfare ships,

and patrol craft.22 SSCs are smaller, less capable in some respects, and individually less expensive

to procure, operate, and support than LSCs. SSCs can operate in conjunction with LSCs and other

Navy ships, particularly in higher-threat operating environments, or independently, particularly in

lower-threat operating environments.

In December 2016, the Navy released a goal to achieve and maintain a Navy of 355 ships,

including 52 SSCs, of which 32 are to be LCSs and 20 are to be FFG(X)s. Although patrol craft

are SSCs, they do not count toward the 52-ship SSC force-level goal, because patrol craft are not

considered battle force ships, which are the kind of ships that count toward the quoted size of the

Navy and the Navy'’s force-level goal.3

3

At the end of FY2018, the Navy'’s force of SSCs totaled 27 battle force ships, including 0 frigates,

16 LCSs, and 11 mine warfare ships. Under the Navy'’s FY2020 30-year (FY2020-FY2049)

shipbuilding plan, the SSC force is to grow to 52 ships (34 LCSs and 18 FFG[X]s) in FY2034,

reach a peak of 62 ships (30 LCSs, 20 FFG[X]s, and 12 SSCs of a future design) in FY2040, and

then decline to 50 ships (20 FFG[X]s and 30 SSCs of a future design) in FY2049.

1

See CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by

Ronald O'Rourke; CRS Report R43838, A Shift in the International Security Environment: Potential Implications for

Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke; and CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background

and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie.

2 See, for example, CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for

Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

3 For additional discussion of battle force ships, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding

Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Congressional Research Service

1

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

U.S. Navy Frigates in General

U.S. Navy Frigates in General

In contrast to cruisers and destroyers, which are designed to operate in higher-threat areas,

frigates are generally intended to operate more in lower-threat areas. U.S. Navy frigates perform

many of the same peacetime and wartime missions as U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers, but

since frigates are intended to do so in lower-threat areas, they are equipped with fewer weapons,

less-capable radars and other systems, and less engineering redundancy and survivability than

cruisers and destroyers.4

4

The most recent class of frigates operated by the Navy was the Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) class (

(Figure 1). A total of 51 FFG-7 class ships were procured between FY1973 and FY1984. The

ships entered service between 1977 and 1989, and were decommissioned between 1994 and 2015.

Figure 1. Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) Class Frigate |

|

Source: Photograph accompanying Dave Werner, |

.

In their final configuration, FFG-7s were about 455 feet long and had full load displacements of

roughly 3,900 tons to 4,100 tons. (By comparison, the Navy'’s Arleigh Burke [DDG-51] class

destroyers are about 510 feet long and have full load displacements of roughly 9,300 tons.)

Following their decommissioning, a number of FFG-7 class ships, like certain other decommissioned U.S. Navy ships, have been transferred to the navies of U.S. allied and partner countries.

4

Compared to cruisers and destroyers, frigates can be a more cost-effective way to perform missions that do not require

the use of a higher-cost cruiser or destroyer. In the past, the Navy’s combined force of higher-capability, higher-cost

cruisers and destroyers and lower-capability, lower-cost frigates has been referred to as an example of a so-called highlow force mix. High-low mixes have been used by the Navy and the other military services in recent decades as a

means of balancing desires for individual platform capability against desires for platform numbers in a context of

varied missions and finite resources.

Peacetime missions performed by frigates can include, among other things, engagement with allied and partner navies,

maritime security operations (such as anti-piracy operations), and humanitarian assistance and disaster response

(HA/DR) operations. Intended wartime operations of frigates include escorting (i.e., protecting) military supply and

transport ships and civilian cargo ships that are moving through potentially dangerous waters. In support of intended

wartime operations, frigates are designed to conduct anti-air warfare (AAW—aka air defense) operations, anti-surface

warfare (ASuW) operations (meaning operations against enemy surface ships and craft), and antisubmarine warfare

(ASW) operations. U.S. Navy frigates are designed to operate in larger Navy formations or as solitary ships. Operations

as solitary ships can include the peacetime operations mentioned above.

Congressional Research Service

2

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

decommissioned U.S. Navy ships, have been transferred to the navies of U.S. allied and partner

countries.

FFG(X) Program

FFG(X) Program

Meaning of Designation FFG(X)

In the program designation FFG(X), FF means frigate,55 G means guided-missile ship (indicating a

ship equipped with an area-defense AAW system),66 and (X) indicates that the specific design of

the ship has not yet been determined. FFG(X) thus means a guided-missile frigate whose specific

design has not yet been determined.7

7 Procurement Quantity and Schedule

Procurement Quantity

Procurement Quantity

The Navy wants to procure 20 FFG(X)s, which in combination with the Navy'’s planned total of

32 LCSs would meet the Navy'’s 52-ship SSC force-level goal. A total of 35 (rather than 32) LCSs

have been procured through FY2019, but Navy officials have stated that the Navy nevertheless

wants to procure 20 FFG(X)s.

The Navy'’s 355-ship force-level goal is the result of a Force Structure Analysis (FSA) that the

Navy conducted in 2016. The Navy conducts a new or updated FSA every few years, and it is

currently conducting a new FSA that is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2019. Navy

officials have stated that this new FSA will likely not reduce the required number of small surface

combatants, and might increase it. Navy officials have also suggested that the Navy in coming

years may shift to a new surface force architecture that will include, among other things, a larger

proportion of small surface combatants.

Figure 2 shows a Navy briefing slide depicting the potential new surface force architecture, with

each sphere representing a manned ship or an unmanned surface vehicle (USV). Consistent with

Figure 2, the Navy'’s 355-ship goal, reflecting the current force architecture, calls for a Navy with

twice as many large surface combatants as small surface combatants. Figure 2 suggests that the

potential new surface force architecture could lead to the obverse—a planned force mix that calls for twice as many small surface combatants than large surface combatants—along with a new

5

The designation FF, with two Fs, means frigate in the same way that the designation DD, with two Ds, means

destroyer. FF is sometimes translated less accurately as fast frigate. FFs, however, are not particularly fast by the

standards of U.S. Navy combatants—their maximum sustained speed, for example, is generally lower than that of U.S.

Navy aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers. In addition, there is no such thing in the U.S. Navy as a slow frigate.

6 Some U.S. Navy surface combatants are equipped with a point-defense AAW system, meaning a short-range AAW

system that is designed to protect the ship itself. Other U.S. Navy surface combatants are equipped with an areadefense AAW system, meaning a longer-range AAW system that is designed to protect no only the ship itself, but other

ships in the area as well. U.S. Navy surface combatants equipped with an area-defense AAW system are referred to as

guided-missile ships and have a “G” in their designation.

7 When the ship’s design has been determined, the program’s designation might be changed to the FFG-62 program,

since FFG-61 was the final ship in the FFG-7 program. It is also possible, however, that the Navy could choose a

different designation for the program at that point. Based on Navy decisions involving the Seawolf (SSN-21) class

attack submarine and the Zumwalt (DDG-1000) class destroyer, other possibilities might include FFG-1000, FFG2000, or FFG-2100. (A designation of FFG-21, however, might cause confusion, as FFG-21 was used for Flatley, an

FFG-7 class ship.) A designation of FFG-62 would be consistent with traditional Navy practices for ship class

designations.

Congressional Research Service

3

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

for twice as many small surface combatants than large surface combatants—along with a new

third tier of numerous USVs.8

third tier of numerous USVs.8

Procurement Schedule

Procurement Schedule

The Navy wants to procure the first FFG(X) in FY2020, the next 18 at a rate of two per year in

FY2021-FY2029, and the 20th in FY2030. Under the Navy'’s FY2020 budget submission, the

first FFG(X) is scheduled to be delivered in July 2026, 72 months after the contract award date of

July 2020.

8

For additional discussion of this possible change in surface force architecture, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force

Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Congressional Research Service

4

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing

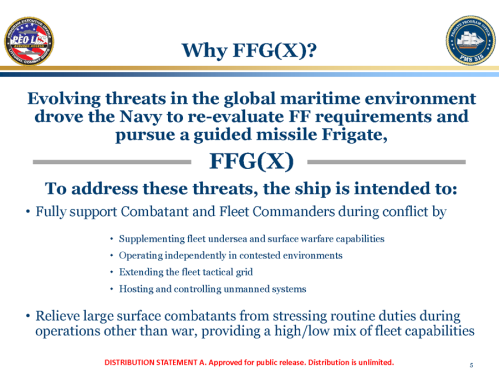

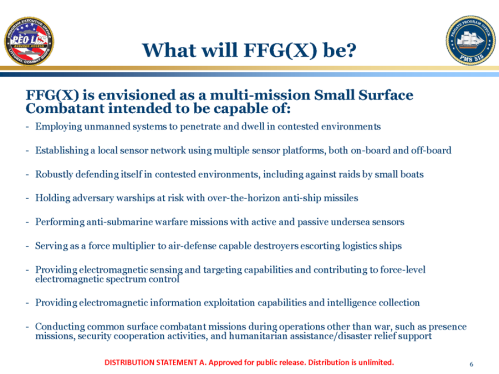

Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing

Ship Capabilities and Design

As mentioned above, the (X) in the program designation FFG(X) means that the design of the

ship has not yet been determined. In general, the Navy envisages the FFG(X) as follows:

-

The ship is to be a multimission small surface combatant capable of conducting

-

Compared to an FF concept that emerged under a February 2014 restructuring of

-

The ship

'’s area-defense AAW system is to be capable of local area AAW,area-defenseareadefense AAW that can be provided by the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers. -

The ship is to be capable of operating in both blue water (i.e., mid-ocean) and

-

The ship is to be capable of operating either independently (when that is

Given the above, the FFG(X) design will likely be larger in terms of displacement, more heavily

armed, and more expensive to procure than either the LCS or an FF concept that emerged from

the February 2014 LCS program restructuring.

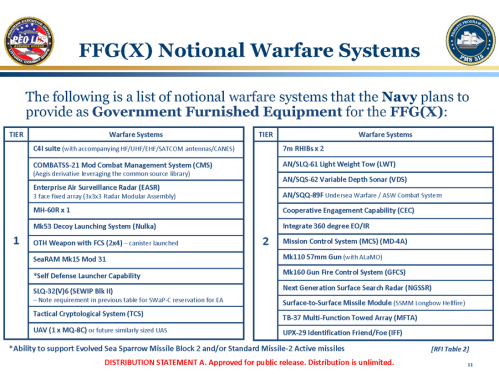

Figure 3 shows a January 2019 Navy briefing slide summarizing the FFG(X)'’s planned

capabilities. For additional information on the FFG(X)'’s planned capabilities, see the Appendix A.9

Dual Crewing

Appendix

A.9

Dual Crewing

To help maximize the time that each ship spends at sea, the Navy reportedly is considering

operating FFG(X)s with dual crews—an approach, commonly called blue-gold crewing, that the

Navy uses for operating its ballistic missile submarines and LCSs.10

Procurement Cost

The Navy wants the follow-on ships in the FFG(X) program (i.e., ships 2 through 20) to have an

average unit procurement cost of $800 million to $950 million each in constant 2018 dollars.11 The Navy reportedly believes that the ship'11

See Sam LaGrone, “NAVSEA: New Navy Frigate Could Cost $950M Per Hull,” USNI News, January 9, 2018;

Richard Abott, “Navy Confirms New Frigate Nearly $1 Billion Each, 4-6 Concept Awards By Spring,” Defense Daily,

January 10, 2018: 1; Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Navy Says It Can Buy Frigate For Under $800M: Acquisition Reform

Testbed,” Breaking Defense, January 12, 2018; Lee Hudson, “Navy to Downselect to One Vendor for Future Frigate

Competition,” Inside the Navy, January 15, 2018; Richard Abott, “Navy Aims For $800 Million Future Frigate Cost,

Leveraging Modularity and Commonality,” Defense Daily, January 17, 2018: 3. The $800 million figure is the

objective cost target; the $950 million figure is threshold cost target. Regarding the $950 million figure, the Navy states

that

The average follow threshold cost for FFG(X) has been established at $950 million (CY18$). The

Navy expects that the full and open competition will provide significant downward cost pressure

incentivizing industry to balance cost and capability to provide the Navy with a best value solution.

FFG(X) cost estimates will be reevaluated during the Conceptual Design phase to ensure the

program stays within the Navy’s desired budget while achieving the desired warfighting

capabilities. Lead ship unit costs will be validated at the time the Component Cost Position is

11

Congressional Research Service

6

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

The Navy reportedly believes that the ship’s cost can be held closer to the $800 million figure.12

s cost can be held closer to the $800 million figure.12 By way of comparison, the Navy estimates the average unit procurement cost of the three LCSs

procured in FY2019 at $523.7 million (not including the cost of each ship'’s embarked mission

package), and the average unit procurement cost of the three DDG-51 class destroyers that the

Navy has requested for procurement in FY2020 at $1,821.0 million.

As shown in Table 2, the Navy'’s proposed FY2020 budget requests $1,281.2 million for the

procurement of the first FFG(X). The lead ship in the program will be considerably more

expensive than the follow-on ships in the program, because the lead ship'’s procurement cost

incorporates most or all of the detailed design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the

class. (It is a traditional Navy budgeting practice to attach most or all of the DD/NRE costs for a

new ship class to the procurement cost of the lead ship in the class.) As shown in Table 2, the Navy'

Navy’s FY2020 budget submission shows that subsequent ships in the class are estimated by the

Navy to cost roughly $900 million each in then-year dollars over the next few years.

The Navy'’s FY2020 budget submission estimates the total procurement cost of 20 FFG(X)s at

$20,470.1 million (i.e., about $20.5 billion) in then-year dollars, or an average of about $1,023.5

million each. Since the figure of $20,470.1 million is a then-year dollar figure, it incorporates

estimated annual inflation for FFG(X)s to be procured out to FY2030.

Acquisition Strategy

Acquisition Strategy Parent-Design Approach

The Navy'’s desire to procure the first FFG(X) in FY2020 does not allow enough time to develop

a completely new design (i.e., a clean-sheet design) for the FFG(X). (Using a clean-sheet design

might defer the procurement of the first ship to about FY2024.) Consequently, the Navy intends

to build the FFG(X) to a modified version of an existing ship design—an approach called the

parent-design approach. The parent design could be a U.S. ship design or a foreign ship design.13

13

Using the parent-design approach can reduce design time, design cost, and cost, schedule, and

technical risk in building the ship. The Coast Guard and the Navy are currently using the parent-design approach for the Coast Guard'parentestablished in 3rd QTR FY19 prior to the Navy awarding the Detail Design and Construction

contract.

(Navy information paper dated November 7, 2017, provided by Navy Office of Legislative Affairs

to CRS and CBO on November 8, 2017.)

The Navy wants the average basic construction cost (BCC) of ships 2 through 20 in the program to be $495 million per

ship in constant 2018 dollars. BCC excludes costs for government furnished combat or weapon systems and change

orders. (Source: Navy briefing slides for FFG(X) Industry Day, November 17, 2017, slide 11 of 16, entitled “Key

Framing Assumptions.”)

12 See, for example, Justin Katz, “FFG(X) Follow-On Ships Likely yo Cost Near $800M, Down from $950M

Threshold,” Inside the Navy, January 21, 2019; Sam LaGrone, “Navy Squeezing Costs Out of GG(X) Program as

Requirements Solidify,” USNI News, January 22, 2019; David B. Larter, “The US Navy’s New, More Lethal Frigate Is

Coming into Focus,” Defense News, January 28, 2019.

13 For articles about reported potential parent designs for the FFG(X), see, for example, Chuck Hill, “OPC Derived

Frigate? Designed for the Royal Navy, Proposed for USN,” Chuck Hill’s CG [Coast Guard] Blog, September 15, 2017;

David B. Larter, “BAE Joins Race for New US Frigate with Its Type 26 Vessel,” Defense News, September 14, 2017;

“BMT Venator-110 Frigate Scale Model at DSEI 2017,” Navy Recognition, September 13, 2017; David B. Larter, “As

the Service Looks to Fill Capabilities Gaps, the US Navy Eyes Foreign Designs,” Defense News, September 1, 2017;

Lee Hudson, “HII May Offer National Security Cutter for Navy Future Frigate Competition,” Inside the Navy, August

7, 2017; Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Beyond LCS: Navy Looks To Foreign Frigates, National Security Cutter,” Breaking

Defense, May 11, 2017.

Congressional Research Service

7

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

design approach for the Coast Guard’s polar security cutter (i.e., polar icebreaker) program.14 The

s polar security cutter (i.e., polar icebreaker) program.14 The parent-design approach has also been used in the past for other Navy and Coast Guard ships,

including Navy mine warfare ships15ships15 and the Coast Guard'’s new Fast Response Cutters (FRCs).16

16 No New Technologies or Systems

As an additional measure for reducing cost, schedule, and technical risk in the FFG(X) program,

the Navy envisages developing no new technologies or systems for the FFG(X)—the ship is to

use systems and technologies that already exist or are already being developed for use in other

programs.

Number of Builders

Given the currently envisaged procurement rate of two ships per year, the Navy'’s baseline plan

for the FFG(X) program envisages using a single builder to build the ships.1717 Consistent with U.S.

law,1818 the ship is to be built in a U.S. shipyard, even if it is based on a foreign design. Using a

foreign design might thus involve cooperation or a teaming arrangement between a U.S. builder

and a foreign developer of the parent design. The Navy has not, however, ruled out the option of

building the ships at two or three shipyards. At a December 12, 2018, hearing on Navy readiness

before two subcommittees (the Seapower subcommittee and the Readiness and Management

Support subcommittee, meeting jointly) of the Senate Armed Services Committee, the following

exchange occurred:

SENATOR ANGUS KING (continuing):

Talking about industrial base and acquisition, the frigate, which we'’re talking about, there

are 5 yards competing, there are going to be 20 ships. As I understand it, the intention now

is to award all 20 ships to the winner, it'’s a winner take all among the five. In terms of

industrial base and also just spreading the work, getting the—getting the work done faster,

talk to me about the possibility of splitting that award between at least two yards if not

three.

SECRETARY OF THE NAVY RICHARD SPENCER:

You bring up an interesting concept. There'’s two things going on here that need to be

weighed out. One, yes, we do have to be attentive to our industrial base and the ability to

keep hands busy and trained. Two, one thing we also have to look at, though, is the balancing of the flow of new ships into the fleet because what we want to avoid is a spike because that spike will come down and bite us again when they all go through regular maintenance cycles and every one comes due within two or three years or four years. It gets very crowded. It's not off the table because we've not awarded anything yet, but we will—we will look at how best we can balance with how we get resourced and, if we have

14

For more on the polar security cutter program, including the parent-design approach, see CRS Report RL34391,

Coast Guard Polar Security Cutter (Polar Icebreaker) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald

O'Rourke

15 The Navy’s Osprey (MCM-51) class mine warfare ships are an enlarged version of the Italian Lerici-class mine

warfare ships.

16 The FRC design is based on a Dutch patrol boat design, the Damen Stan Patrol Boat 4708.

17 See, for example, Lee Hudson, “Navy to Downselect to One Vendor for Future Frigate Competition,” Inside the

Navy, January 15, 2018.

18 10 U.S.C. 7309 requires that, subject to a presidential waiver for the national security interest, “no vessel to be

constructed for any of the armed forces, and no major component of the hull or superstructure of any such vessel, may

be constructed in a foreign shipyard.” In addition, the paragraph in the annual DOD appropriations act that makes

appropriations for the Navy’s shipbuilding account (the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy account) typically contains

these provisos: “ ... Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this heading for the construction or

conversion of any naval vessel to be constructed in shipyards in the United States shall be expended in foreign facilities

for the construction of major components of such vessel: Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this

heading shall be used for the construction of any naval vessel in foreign shipyards.... ”

Congressional Research Service

8

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

balancing of the flow of new ships into the fleet because what we want to avoid is a spike

because that spike will come down and bite us again when they all go through regular

maintenance cycles and every one comes due within two or three years or four years. It

gets very crowded. It’s not off the table because we’ve not awarded anything yet, but we

will—we will look at how best we can balance with how we get resourced and, if we have

the resources to bring expedition, granted, we will do that.19

the resources to bring expedition, granted, we will do that.19

Block Buy Contracting

As a means of reducing their procurement cost, the Navy envisages using one or more fixed-price

block buy contracts to procure the ships.20

20 Competing Industry Teams

As shown in Table 1, at least four industry teams are reportedly competing for the FFG(X)

program. Two of the teams are reportedly proposing to build their FFG(X) designs at the two

shipyards that have been building Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) for the Navy—Austal USA of

Mobile, AL, and Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WI. The other two teams are

reportedly proposing to build their FFG(X) designs at General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works

(GD/BIW), of Bath, ME, and Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of

Pascagoula, MS.

As also shown in Table 1, a fifth industry team that had been interested in the FFG(X) program

reportedly informed the Navy on May 23, 2019, that it had decided to not submit a bid for the

program.2121 As shown in the table, this fifth industry team, like one of the other four, reportedly

had proposed building its FFG(X) design at F/MM.

|

Industry team leader |

Parent design |

Shipyard that would build the ships |

Industry team leader Parent design Shipyard that would build the ships At least four industry teams, shown below, are reportedly competing for the FFG(X) program | ||

|

Austal USA |

Austal USA Independence (LCS-2) class LCS design |

Austal USA of Mobile, AL

Fincantieri Marine

Group

|

|

Fincantieri Marine Group |

Italian Fincantieri FREMM (Fregata |

Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of |

General Dynamics/Bath | Spanish Navantia Álvaro de Bazán-class | General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works |

|

Huntington Ingalls Industries |

[Not disclosed] |

Huntington Ingalls Industries/ Ingalls |

A fifth industry team reportedly informed the Navy on May 23, 2019, that it had decided to not submit a | ||

|

Lockheed Martin |

Lockheed Martin Freedom (LCS-1) class LCS design | F/MM of Marinette, WI |

Source: Sam LaGrone and Megan Eckstein, "“Navy Picks Five Contenders for Next Generation Frigate FFG(X)

Program," ” USNI News, February 16, 2018; Sam LaGrone, "“Lockheed Martin Won't Submit Freedom LCS Design for FFG(X) Contest,"’t Submit Freedom LCS Design

19

Source: Transcript of hearing posted at CQ.com.

For more on block buy contracting, see CRS Report R41909, Multiyear Procurement (MYP) and Block Buy

Contracting in Defense Acquisition: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Moshe Schwartz.

21 Sam LaGrone, “Lockheed Martin Won’t Submit Freedom LCS Design for FFG(X) Contest,” USNI News, May 28,

2019.

20

Congressional Research Service

9

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

for FFG(X) Contest,” USNI News, May 28, 2019. See also David B. Larter, "“Navy Awards Design Contracts for

Future Frigate," ” Defense News, February 16, 2018; Lee Hudson, "“Navy Awards Five Conceptual Design Contracts

for Future Frigate Competition," ” Inside the Navy, February 19, 2018.

On February 16, 2018, the Navy awarded five FFG(X) conceptual design contracts with a value

of $15.0 million each to the leaders of the five industry teams shown in Table 1.22.22 Being a

recipient of a conceptual design contract was not a requirement for competing for the subsequent

Detailed Design and Construction (DD&C) contract for the program.

The Navy plans to announce the outcome of the FFG(X) competition—the winner of the DD&C

contract—in July 2020.

Program Funding

Program Funding

Table 2 shows funding for the FFG(X) program under the Navy'’s FY2020 budget submission.

Table 2. FFG(X) Program Funding

Millions of then-year dollars, rounded to nearest tenth.

Research and development

Procurement

Prior

years

FY18

FY19

84.6

137.7

132.8

59.0

85.3

75.4

70.7

72.1

0

0

0

1,281.2

2,057.0

1,750.4

1,792.1

1,827.9

(1)

(2)

(2)

(2)

(2)

FY20

(Procurement quantity)

FY21

FY22

FY23

FY24

Source: Millions of then-year dollars, rounded to nearest tenth.

|

Prior years |

FY18 |

FY19 |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

|

|

Research and development |

84.6 |

137.7 |

132.8 |

59.0 |

85.3 |

75.4 |

70.7 |

72.1 |

|

Procurement |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1,281.2 |

2,057.0 |

1,750.4 |

1,792.1 |

1,827.9 |

|

(Procurement quantity) |

(1) |

(2) |

(2) |

(2) |

(2) |

Source: Navy FY2020 budget submission.

Navy FY2020 budget submission.

Notes: Research and development funding is located in PE (Program Element) 0603599N, Frigate Development,

which is line 54 in the FY2020 Navy research and development account.

Issues for Congress

FY2020 Funding Request

One issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy'’s FY2020 funding

request for the program. In assessing this question, Congress may consider, among other things,

whether the work the Navy is proposing to do in the program in FY2020 is appropriate, and

whether the Navy has accurately priced that work.

Cost, Capabilities, and Growth Margin

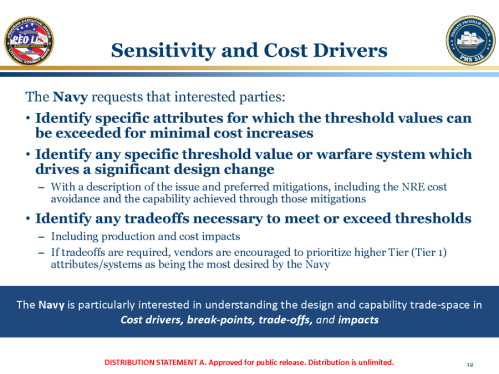

Another issue for Congress is whether the Navy has appropriately defined the cost, capabilities,

and growth margin of the FFG(X).

22

Department of Defense, Contracts, Press Operations, Release No: CR-032-18, February 16, 2018 (i.e., the DOD

contracts award page for February 16, 2018). See also Ben Werner, “Navy Exercises Options For Additional Future

Frigate Design Work,” USNI News, July 31, 2018; Rich Abott, “Navy Awards Mods To FFG(X) Design Contracts,”

Defense Daily, August 1, 2018; Kris Osborn, “The Navy Is Moving Fast to Build a New Frigate. Here Is What We

Know,” National Interest, August 1, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

10

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities

Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities

One aspect of this issue is whether the Navy has an adequately rigorous analytical basis for its

identification of the capability gaps or mission needs to be met by the FFG(X), and for its

decision to meet those capability gaps or mission needs through the procurement of a FFG with

the capabilities outlined earlier in this CRS report. The question of whether the Navy has an

adequately rigorous analytical basis for these things was discussed in greater detail in earlier

editions of this CRS report.23

23 Balance Between Cost and Capabilities

Another potential aspect of this issue is whether the Navy has arrived at a realistic balance

between its desired capabilities for the FFG(X) and the its estimated procurement cost for the

ship. An imbalance between these two could lead to an increased risk of cost growth in the

program. The Navy could argue that a key aim of the five FFG(X) conceptual design contracts

and other preliminary Navy interactions with industry was to help the Navy arrive at a realistic

balance by informing the Navy'’s understanding of potential capability-cost tradeoffs in the

FFG(X) design.

Number of VLS Tubes

Another potential aspect of this issue concerns the planned number of Vertical Launch System

(VLS) missile tubes on the FFG(X). The VLS is the FFG(X)'’s principal (though not only) means

of storing and launching missiles. As shown in Figure 3 (see the box in the upper-left corner

labeled "“AW,"” meaning air warfare), the FFG(X) is to be equipped with 32 Mark 41 VLS tubes.

(The Mark 41 is the Navy'’s standard VLS design.)

Supporters of requiring the FFG(X) to be equipped with a larger number of VLS tubes, such as

48, might argue that the FFG(X) is to be roughly half as expensive to procure as the DDG-51

destroyer, and might therefore be more appropriately equipped with 48 VLS tubes, which is one-halfonehalf the number on recent DDG-51s. They might also argue that in a context of renewed great

power competition with potential adversaries such as China, which is steadily improving its naval

capabilities,2424 it might be prudent to equip the FFG(X)s with 48 rather than 32 VLS tubes, and

that doing so might only marginally increase the unit procurement cost of the FFG(X).

Supporters of requiring the FFG(X) to have no more than 32 VLS tubes might argue that the

analyses indicating a need for 32 already took improving adversary capabilities (as well as other

U.S. Navy capabilities) into account. They might also argue that the FFG(X), in addition to

having 32 VLS tubes, is also to have a separate, 21-cell Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM) missile

launcher (see again the "AW"“AW” box in the upper-left corner of Figure 3), and that increasing the

number of VLS tubes from 32 to 48 would increase the procurement cost of a ship that is

intended to be an affordable supplement to the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers.

Potential oversight questions for Congress might be: What would be the estimated increase in unit

procurement cost of the FFG(X) of increasing the number of VLS tubes from 32 to 48? What

would be the estimated increase in unit procurement cost of equipping the FFG(X) with 32 VLS

tubes but designing the ship so that the number could easily be increased to 48 at some point later

in the ship'’s life?

23

See, for example, the version of this report dated February 4, 2019.

For more on China’s naval modernization effort, see CRS Report RL33153, China Naval Modernization:

Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

24

Congressional Research Service

11

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Growth Margin

s life?

Growth Margin

Another potential aspect of this issue is whether, beyond the specific question of the number of

VLS tubes, the Navy more generally has chosen the appropriate amount of growth margin to

incorporate into the FFG(X) design. As shown in the Appendix A, the Navy wants the FFG(X)

design to have a growth margin (also called service life allowance) of 5%, meaning an ability to

accommodate upgrades and other changes that might be made to the ship'’s design over the course

of its service life that could require up to 5% more space, weight, electrical power, or equipment

cooling capacity. As shown in the Appendix A, the Navy also wants the FFG(X) design to have

an additional growth margin (above the 5% factor) for accommodating a future directed energy

system (i.e., a laser or high-power microwave device) or an active electronic attack system (i.e.,

electronic warfare system).

Supporters could argue that a 5% growth margin is traditional for a ship like a frigate, that the

FFG(X)'’s 5% growth margin is supplemented by the additional growth margin for a directed

energy system or active electronic attack system, and that requiring a larger growth margin could

make the FFG(X) design larger and more expensive to procure.

Skeptics might argue that a larger growth margin (such as 10%—a figure used in designing

cruisers and destroyers) would provide more of a hedge against the possibility of greater-than-anticipatedthananticipated improvements in the capabilities of potential adversaries such as China, that a limited

growth margin was a concern in the FFG-7 design,2525 and that increasing the FFG(X) growth

margin from 5% to 10% would have only a limited impact on the FFG(X)'’s procurement cost.

A potential oversight question for Congress might be: What would be the estimated increase in

unit procurement cost of the FFG(X) of increasing the ship'’s growth margin from 5% to 10%?

Parent-Design Approach

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns the parent-design approach for the

program. One alternative would be to use a clean-sheet design approach, under which

procurement of the FFG(X) would begin about FY2024 and procurement of LCSs might be

extended through about 2023.

As mentioned earlier, using the parent-design approach can reduce design time, design cost, and

technical, schedule, and cost risk in building the ship. A clean-sheet design approach, on the other

hand, might result in a design that more closely matches the Navy'’s desired capabilities for the

FFG(X), which might make the design more cost-effective for the Navy over the long run. It

might also provide more work for the U.S. ship design and engineering industrial base.

Another possible alternative would be to consider frigate designs that have been developed, but

for which there are not yet any completed ships. This approach might make possible

consideration of designs, such as (to cite just one possible example) the UK'’s new Type 26 frigate

design, production of which was in its early stages in 2018. Compared to a clean-sheet design

approach, using a developed-but-not-yet-built design would offer a reduction in design time and

cost, but might not offer as much reduction in technical, schedule, and cost risk in building the

ship as would be offered by use of an already-built design.

25

See, for example, See U.S. General Accounting Office, Statement of Jerome H. Stolarow, Director, Procurement and

Systems Acquisition Division, before the Subcommittee on Priorities and Economy in Government, Joint Economic

Committee on The Navy’s FFG-7 Class Frigate Shipbuilding Program, and Other Ship Program Issues, January 3,

1979, pp. 9-11.

Congressional Research Service

12

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Cost, Schedule, and Technical Risk

Cost, Schedule, and Technical Risk

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns cost, schedule, and technical risk in the

FFG(X) program. The Navy can argue that the program'’s cost, schedule, and technical risk has

been reduced by use of the parent-design approach and the decision to use only systems and

technologies that already exist or are already being developed for use in other programs, rather

than new technologies that need to be developed.

Skeptics, while acknowledging that point, might argue that lead ships in Navy shipbuilding

programs inherently pose cost, schedule, and technical risk, because they serve as the prototypes

for their programs, and that, as detailed by CBO26CBO26 and GAO,2727 lead ships in Navy shipbuilding

programs in many cases have turned out to be more expensive to build than the Navy had

estimated. A May 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) on the status of

various Department of Defense (DOD) acquisition programs states the following about the

FFG(X) program:

Current Status

Current Status

The FFG(X) program continues conceptual design work ahead of planned award of a lead

ship detail design and construction contract in September 2020. In May 2017, the Navy

revised its plans for a new frigate derived from minor modifications of an LCS design. The

current plan is to select a design and shipbuilder through full and open competition to

provide a more lethal and survivable small surface combatant.

As stated in the FFG(X) acquisition strategy, the Navy awarded conceptual design

contracts in February 2018 for development of five designs based on ships already

demonstrated at sea. The tailoring plan indicates the program will minimize technology

development by relying on government-furnished equipment from other programs or

known-contractor-furnished equipment.

In November 2018, the program received approval to tailor its acquisition documentation

to support development start in February 2020. This included waivers for several

requirements, such as an analysis of alternatives and an affordability analysis for the total

program life cycle. FFG(X) also received approval to tailor reviews to validate system

specifications and the release of the request for proposals for the detail design and

construction contract….

Program Office Comments

We provided a draft of this assessment to the program office for review and comment. The

program office did not have any comments.28

28 Procurement of LCSs in FY2020 as Hedge against FFG(X) Delay

Another potential issue for Congress is whether any additional LCSs should be procured in

FY2020 as a hedge against potential delays in the FFG(X) program. Supporters might argue that,

as detailed by GAO,2929 lead ships in Navy shipbuilding programs in many cases encounter

See Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2019 Shipbuilding Plan, October 2018, p.

25, including Figure 10.

27 See Government Accountability Office, Navy Shipbuilding[:] Past Performance Provides Valuable Lessons for

Future Investments, GAO-18-238SP, June 2018, p. 8.

28 Government Accountability Office, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment[:] Limited Use of Knowledge-Based

Practices Continues to Undercut DOD’s Investments, GAO-19-336SP, p. 132.

29 See Government Accountability Office, Navy Shipbuilding[:] Past Performance Provides Valuable Lessons for

Future Investments, GAO-18-238SP, June 2018, p. 9.

26

Congressional Research Service

13

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

schedule delays, some quite lengthy, and that procuring additional LCSs in FY2020 could hedge

against that risk at reasonable cost by taking advantage of hot LCS production lines. Skeptics

might argue that the Navy does not have a requirement for any additional LCSs, and that funding

the procurement of additional LCSs in FY2020 could reduce FY2020 funding available for other

Navy or DOD programs, with an uncertain impact on net Navy or DOD capabilities.

Potential Industrial-Base Impacts of FFG(X) Program

Another issue for Congress concerns the potential industrial-base impacts of the FFG(X) for

shipyards and supplier firms.

Shipyards

Shipyards

One aspect of this issue concerns the potential impact on shipyards of the Navy'’s plan to shift

procurement of small surface combatants from LCSs to FFG(X)s starting in FY2020, particularly

in terms of future workloads and employment levels at the two LCS shipyards, if one or both of

these yards are not involved in building FFG(X)s.

If a design proposed for construction at one of the LCS shipyards is chosen as the winner of the

FFG(X) competition, then other things held equal (e.g., without the addition of new work other

than building LCSs), workloads and employment levels at the otherother LCS shipyard (the one not not

chosen for the FFG(X) program), as well as supplier firms associated with that other LCS

shipyard, would decline over time as the other LCS shipyard'’s backlog of prior-year-funded

LCSs is completed and not replaced with new FFG(X) work. If no design proposed for

construction at an LCS shipyard is chosen as the FFG(X)—that is, if the winner of the FFG(X)

competition is a design to be built at a shipyard other than the two LCS shipyards—then other

things held equal, employment levels at both LCS shipyards and their supplier firms would

decline over time as their backlogs of prior-year-funded LCSs are completed and not replaced

with FFG(X) work.30

30

As mentioned earlier, the Navy'’s current baseline plan for the FFG(X) program is to build

FFG(X)s at a single shipyard. One possible alternative to this baseline plan would be to build

FFG(X)s at two or three shipyards, including one or both of the LCS shipyards. This alternative is

discussed further in the section below entitled "“Number of FFG(X) Builders."

.”

Another possible alternative would be would be to shift Navy shipbuilding work at one of the

LCS yards (if the other wins the FFG(X) competition) or at both of the LCS yards (if neither wins

the FFG(X) competition) to the production of sections of larger Navy ships (such as DDG-51

destroyers or amphibious ships) that undergo final assembly at other shipyards. Under this option,

in other words, one or both of the LCS yards would function as shipyards participating in the

production of larger Navy ships that undergo final assembly at other shipyards. This option might

help maintain workloads and employment levels at one or both of the LCS yards, and might

alleviate capacity constraints at other shipyards, permitting certain parts of the Navy'’s 355-ship

force-level objective to be achieved sooner. The concept of shipyards producing sections of larger

naval ships that undergo final assembly in other shipyards was examined at length in a 2011

RAND report.31

Supplier Firms

31

For additional discussion, see, for example, Roxana Tiron, “Shipyards Locked in ‘Existential’ Duel for Navy’s New

Frigate,” Bloomberg, February 20, 2019; Paul McLeary, “Saudis Save Wisconsin Shipbuilder: Fills Gap Between LCS

& Frigates At Marinette,” Breaking Defense, January 17, 2019.

31 Laurence Smallman et al., Shared Modular Build of Warships, How a Shared Build Can Support Future

30

Congressional Research Service

14

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Supplier Firms

Another aspect of the industrial-base issue concerns the FFG(X) program'’s potential impact on

supplier firms (i.e., firms that provide materials and components that are incorporated into ships).

Some supporters of U.S. supplier firms argue that the FFG(X) program as currently structured

does not include strong enough provisions for requiring certain FFG(X) components to be U.S.-made, particularly since two of the five industry teams reported to be competing for the FFG(X)

program (see the earlier section entitled "“Competing Industry Teams"”) are reportedly using

European frigate designs as their proposed parent design. For example, the American

Shipbuilding Suppliers Association (ASSA)—a trade association for U.S. ship supplier firms—

states:

The US Navy has historically selected US manufactured components for its major surface

combatants and designated them as class standard equipment to be procured either as

government-furnished equipment (GFE) or contractor-furnished equipment (CFE). In a

major departure from that policy, the Navy has imposed no such requirement for the

FFG(X), the Navy'’s premier small surface combatant. The acquisition plan for FFG(X)

requires proposed offerings to be based on an in-service parent craft design. Foreign

designs and/or foreign-manufactured components are being considered, with foreign

companies performing a key role in selecting these components. Without congressional

direction, there is a high likelihood that critical HM&E components on the FFG(X) will

not be manufactured within the US shipbuilding industrial supplier base.….

The Navy'’s requirements are very clear regarding the combat system, radar, C4I suite,32 32

EW [electronic warfare], weapons, and numerous other war-fighting elements. However,

unlike all major surface combatants currently in the fleet (CGs [cruisers], DDGs

[destroyers]), the [Navy'’s] draft RFP [Request for Proposals] for the FFG(X) does not

identify specific major HM&E components such as propulsion systems, machinery

controls, power generation and other systems that are critical to the ship'’s operations and

mission execution. Instead, the draft RFP relegates these decisions to shipyard primes or their foreign-owned partners, and there is no requirement for sourcing these components

Shipbuilding, RAND, Santa Monica, CA, 2011 (report TR-852), 81 pp. The Navy in recent years has made some use of

the concept:

All Virginia-class attack submarines have been produced jointly by General Dynamics’ Electric Boat division

(GD/EB) and Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding (HII/NNS), with each yard in effect

acting as a feeder yard for Virginia-class boats that undergo final assembly at the other yard.

Certain components of the Navy’s three Zumwalt (DDG-1000) class destroyers were produced by HII’s

Ingalls Shipyard (HII/Ingalls) and then transported to GD’s Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW), the primary builder

and final assembly yard for the ships.

San Antonio (LPD-17) class amphibious ships were built at the Ingalls shipyard at Pascagoula, MS, and the

Avondale shipyard near New Orleans, LA. These shipyards were owned by Northrop and later by HII. To

alleviate capacity constraints at Ingalls and Avondale caused by damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005,

Northrop subcontracted the construction of portions of LPDs 20 through 24 (i.e., the fourth through eighth

ships in the class) to other shipyards on the Gulf Coast and East Coast, including shipyards not owned by

Northrop.

For more on the Virginia-class joint production arrangement, see CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774)

Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. Regarding the LPD17 program, see Laurence Smallman et al., Shared Modular Build of Warships, How a Shared Build Can Support

Future Shipbuilding, RAND, Santa Monica, CA, 2011 (report TR-852), pp. 45-48. See also David Paganie, “Signal

International positions to capture the Gulf,” Offshore, June 1, 2006; Peter Frost, “Labor Market, Schedule Forces

Outsourcing of Work,” Newport News Daily Press, April 1, 2008; Holbrook Mohr, “Northrop Gets LPD Help From

General Dynamics,” NavyTimes.com, April 1, 2008; and Geoff Fein, “Northrop Grumman Awards Bath Iron Works

Construction Work On LPD-24,” Defense Daily, April 2, 2008.

32 This is a reference to the ship’s collection of command and control, communications, and computer equipment.

Congressional Research Service

15

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

their foreign-owned partners, and there is no requirement for sourcing these components

within the US shipbuilding supplier industrial base.

within the US shipbuilding supplier industrial base.

The draft RFP also does not clearly identify life-cycle cost as a critical evaluation factor,

separate from initial acquisition cost. This ignores the cost to the government of initial

introduction [of the FFG(X)] into the [Navy'’s] logistics system, the training necessary for

new systems, the location of repair services (e.g., does the equipment need to leave the

US?), and the cost and availability of parts and services for the lifetime of the ship.

Therefore, lowest acquisition cost is likely to drive the award—certainly for component

suppliers.

Further, the US Navy'’s acquisition approach not only encourages, but advantages, the use

of foreign designs, most of which have a component supplier base that is foreign. Many of

these component suppliers (and in some cases the shipyards they work with) are wholly or

partially owned by their respective governments and enjoy direct subsidies as well as other

benefits from being state owned (e.g., requirements relaxation, tax incentives, etc.). This

uneven playing field, and the high-volume commercial shipbuilding market enjoyed by the

foreign suppliers, make it unlikely for an American manufacturer to compete on cost. As

incumbent component manufacturers, these foreign companies have a substantial

advantage over US component manufacturers seeking to provide equipment even if costs

could be matched, given the level of non-recurring engineering (NRE) required to facilitate

new equipment into a parent craft'’s design and the subsequent performance risk.

The potential outcome of such a scenario would have severe consequences across the US

shipbuilding supplier base…. the loss of the FFG(X) opportunity to US suppliers would

increase the cost on other Navy platforms [by reducing production economies of scale at

U.S. suppliers that make components for other U.S. military ships]. Most importantly,

maintaining a robust domestic [supplier] manufacturing capability allows for a surge

capability by ensuring rapidly scalable capacity when called upon to support major military

operations—a theme frequently emphasized by DOD and Navy leaders.

These capabilities are a critical national asset and once lost, it is unlikely or extremely

costly to replicate them. This would be a difficult lesson that is not in the government's ’s

best interests to re-learn. One such lesson exists on the DDG-51 [destroyer production]

restart,3333 where the difficulty of reconstituting a closed production line of a critical

component manufacturer—its main reduction gear—required the government to fund the

manufacturer directly as GFE, since the US manufacturer for the reduction gear had ceased

operations.34

34

Other observers, while perhaps acknowledging some of the points made above, might argue one

or more of the following:

-

foreign-made components have long been incorporated into U.S. Navy ships (and

-

U.S-made components have long been incorporated into foreign

warships35(andwarships35 (and other foreign military equipment); and -

requiring a foreign parent design for the FFG(X) to be modified to incorporate

FFG(X) or the FFG(X) program's acquisition risk (i.e., cost, schedule, and33 This is a reference to how procurement of DDG-51 destroyers stopped in FY2005 and then resumed in FY2010. For additional discussion, see CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. 34 Source: American Shipbuilding Suppliers Association (ASSA) point paper, “The Impact of FFG(X) on the US Shipbuilding Supplier Industrial Base,” undated, received by CRS from ASSA on May 1, 2019, pp. 1, 2-3. 35 For example, foreign warships incorporate, among other things, U.S.-made combat system components and U.S.made gas turbine engines. Congressional Research Service 16 Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress FFG(X) or the FFG(X) program’s acquisition risk (i.e., cost, schedule, and technical risk), or both.

Current U.S. law requires certain components of U.S. Navy ships to be made by a manufacturer

in the national technology and industrial base. The primary statute in question—10 U.S.C.

2534—states in part:

§2534. Miscellaneous limitations on the procurement of goods other than United States goods

goods

(a) Limitation on Certain Procurements.-The Secretary of Defense may procure any of the

following items only if the manufacturer of the item satisfies the requirements of subsection

(b):…

(3) Components for naval vessels.-(A) The following components:

(i) Air circuit breakers.

(ii) Welded shipboard anchor and mooring chain with a diameter of four inches or less.

(iii) Vessel propellers with a diameter of six feet or more.

(B) The following components of vessels, to the extent they are unique to marine

applications: gyrocompasses, electronic navigation chart systems, steering controls,

pumps, propulsion and machinery control systems, and totally enclosed lifeboats.

(b) Manufacturer in the National Technology and Industrial Base.-

(1) General requirement.-A manufacturer meets the requirements of this subsection if the

manufacturer is part of the national technology and industrial base….

(3) Manufacturer of vessel propellers.-In the case of a procurement of vessel propellers

referred to in subsection (a)(3)(A)(iii), the manufacturer of the propellers meets the

requirements of this subsection only if-

(A) the manufacturer meets the requirements set forth in paragraph (1); and

(B) all castings incorporated into such propellers are poured and finished in the United

States.

(c) Applicability to Certain Items.-

(1) Components for naval vessels.-Subsection (a) does not apply to a procurement of spare

or repair parts needed to support components for naval vessels produced or manufactured

outside the United States….

(4) Vessel propellers.-Subsection (a)(3)(A)(iii) and this paragraph shall cease to be

effective on February 10, 1998….

(d) Waiver Authority.-The Secretary of Defense may waive the limitation in subsection (a)

with respect to the procurement of an item listed in that subsection if the Secretary

determines that any of the following apply:

(1) Application of the limitation would cause unreasonable costs or delays to be incurred.

(2) United States producers of the item would not be jeopardized by competition from a

foreign country, and that country does not discriminate against defense items produced in

the United States to a greater degree than the United States discriminates against defense

items produced in that country.

(3) Application of the limitation would impede cooperative programs entered into between

the Department of Defense and a foreign country, or would impede the reciprocal

procurement of defense items under a memorandum of understanding providing for

reciprocal procurement of defense items that is entered into under section 2531 of this title,

Congressional Research Service

17

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

and that country does not discriminate against defense items produced in the United States

to a greater degree than the United States discriminates against defense items produced in

that country.

(4) Satisfactory quality items manufactured by an entity that is part of the national

technology and industrial base (as defined in section 2500(1) of this title) are not available.

(5) Application of the limitation would result in the existence of only one source for the

item that is an entity that is part of the national technology and industrial base (as defined

in section 2500(1) of this title).

(6) The procurement is for an amount less than the simplified acquisition threshold and

simplified purchase procedures are being used.

(7) Application of the limitation is not in the national security interests of the United States.

(8) Application of the limitation would adversely affect a United States company….

(h) Implementation of Naval Vessel Component Limitation.-In implementing subsection

(a)(3)(B), the Secretary of Defense-

(1) may not use contract clauses or certifications; and

(2) shall use management and oversight techniques that achieve the objective of the

subsection without imposing a significant management burden on the Government or the

contractor involved.

(i) Implementation of Certain Waiver Authority.-(1) The Secretary of Defense may

exercise the waiver authority described in paragraph (2) only if the waiver is made for a

particular item listed in subsection (a) and for a particular foreign country.

(2) This subsection applies to the waiver authority provided by subsection (d) on the basis

of the applicability of paragraph (2) or (3) of that subsection.

(3) The waiver authority described in paragraph (2) may not be delegated below the Under

Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics.

(4) At least 15 days before the effective date of any waiver made under the waiver authority

described in paragraph (2), the Secretary shall publish in the Federal Register and submit

to the congressional defense committees a notice of the determination to exercise the

waiver authority.

(5) Any waiver made by the Secretary under the waiver authority described in paragraph

(2) shall be in effect for a period not greater than one year, as determined by the Secretary....

In addition to 10 U.S.C. 2534, the paragraph in the annual DOD appropriations act that makes

appropriations for the Navy'’s shipbuilding account (i.e., the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy,

or SCN, appropriation account) has in recent years included this proviso:

…

…Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this heading for the construction

or conversion of any naval vessel to be constructed in shipyards in the United States shall

be expended in foreign facilities for the construction of major components of such

vessel….

10 U.S.C. 2534 explicitly applies to certain ship components, but not others. The meaning of "

“major components"” in the above proviso from the annual DOD appropriations act might be

subject to interpretation.

Congressional Research Service

18

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

The issue of U.S.-made components for Navy ships is also, for somewhat different reasons, an

issue for Congress in connection with the Navy'’s John Lewis (TAO-205) class oiler shipbuilding

program.36

36 Number of FFG(X) Builders

Another issue for Congress whether to build FFG(X)s at a single shipyard, as the Navy'’s baseline

plan calls for, or at two or three shipyards. As mentioned earlier, one possible alternative to the Navy'

Navy’s current baseline plan for building FFG(X)s at a single shipyard would be to build them at

two or three yards, including potentially one or both of the LCS shipyards. The Navy'’s FFG-7

class frigates, which were procured at annual rates of as high as eight ships per year, were built at

three shipyards.3737 Supporters of building FFG(X)s at two or three yards might argue that it could

-

boost FFG(X) production from the currently planned two ships per year to four

's’s small surface combatant force-level goal; -

permit the Navy to use competition (either competition for quantity at the margin,

38to38 to help restrain FFG(X) prices and ensure production quality and on-time deliveries;and -

and

perhaps complicate adversary defense planning by presenting potential

Opponents of this plan might argue that it could

-

weaken the current FFG(X) competition by offering the winner a smaller

-

substantially increase annual FFG(X) procurement funding requirements so as to

-

reduce production economies of scale in the FFG(X) program by dividing

36

See CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues

for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

37 The 51 FFG-7s were procured from FY1973 through FY1984 in annual quantities of 1, 0, 3, 6, 8, 8, 8, 5, 6, 3, 2, and

1. The three FFG-7 builders were GD/BIW, Todd Shipyards/San Pedro, CA, and Todd Shipyards/Seattle, WA. The two

Todd shipyards last built Navy ships in the latter 1980s. (See, for example, U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the

Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020, March 2019, p. 16.) Todd/San Pedro

closed at the end of the 1980s. Todd/Seattle was purchased by and now forms part of Vigor Shipyards, a firm with

multiple facilities in the Puget Sound area and in Portland, OR. Vigor’s work for the Navy in recent years has centered

on the overhaul and repair of existing Navy ships, although it also builds ships for other customers.

38 For more on PRO bidding, see Statement of Ronald O’Rourke, Specialist in Naval Affairs, Congressional Research

Service, before the House Armed Services Committee on Case Studies in DOD Acquisition: Finding What Works, June

24, 2014, p. 7.

Congressional Research Service

19

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Potential Change in Navy Surface Force Architecture

Potential Change in Navy Surface Force Architecture

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns the potential impact on required numbers

of FFG(X)s of a possible change in the Navy'’s surface force architecture. As mentioned earlier,

Navy officials have stated that the new Force Structure Assessment (FSA) being conducted by the

Navy may shift the Navy to a new fleet architecture that will include, among other thing, a larger

proportion of small surface combatants—and, by implication, a smaller proportion of large

surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers). A change in the required number of FFG(X)s

could influence perspectives on the annual procurement rate for the program and the number of

shipyards used to build the ships. A January 15, 2019, press report states:

The Navy plans to spend this year taking the first few steps into a markedly different future,

which, if it comes to pass, will upend how the fleet has fought since the Cold War. And it

all starts with something that might seem counterintuitive: It'’s looking to get smaller.

"

“Today, I have a requirement for 104 large surface combatants in the force structure

assessment; [and] I have [a requirement for] 52 small surface combatants,"” said Surface

Warfare Director Rear Adm. Ronald Boxall. "That'“That’s a little upside down. Should I push

out here and have more small platforms? I think the future fleet architecture study has

intimated '‘yes,'’ and our war gaming shows there is value in that."39

” 39 An April 8, 2019, press report states that Navy discussions about the future surface fleet include

the upcoming construction and fielding of the [FFG(X)] frigate, which [Vice Admiral Bill

Merz, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfare systems] said is surpassing

expectations already in terms of the lethality that industry can put into a small combatant.

"

“The FSA may actually help us on, how many (destroyers) do we really need to modernize,

because I think the FSA is going to give a lot of credit to the frigate—if I had a crystal ball

and had to predict what the FSA was going to do, it'’s going to probably recommend more