U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from January 31, 2019 to August 23, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

China's ActionsU.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Implications for U.S. Interests—Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Focus of Report

- Issue for Congress

- Terminology Used in This Report

- Background

- U.S. Interests in SCS and ECS

- U.S. Regional Allies and Partners, and U.S. Regional Security Architecture

- Principle of Nonuse of Force or Coercion

- Principle of Freedom of the Seas

- Trade Routes and Hydrocarbons

- Interpreting China's

RiseRole as a Major World Power - U.S.-China Relations in General

- Overview of Maritime Disputes in SCS and ECS

- Maritime Territorial Disputes

- Dispute Regarding China's Rights within Its EEZ, and Associated U.S.-Chinese Incidents at Sea

- Maritime Territorial Disputes

- EEZ Dispute

- Relationship of Maritime Territorial Disputes to EEZ Dispute

- China's Approach to the SCS and ECS

- In General

- "Salami-Slicing" Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

- Island Building and Base Construction

- Other Chinese Actions That Have Heightened Concerns

- Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

- Apparent Narrow Definition of "Freedom of Navigation"

- Preference for Treating Territorial Disputes on Bilateral Basis

- Depiction of United States as Outsider Seeking to "Stir Up Trouble"

- July 2018 Press Report Regarding Chinese Radio Warnings

- U.S. Position on

Maritime Disputes inRegarding Issues Relating to SCS and ECS - Some Key Elements

- Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program

- Assessments of China's Strengthening Position in SCS

- Issues for Congress

- U.S. Response to China's Actions in SCS and ECS

- Overview

- Review of China's Approach

- Potential U.S. Goals

- Aligning Actions with Goals

- Contributions from Allies and Partners

- U.S. Actions During Obama Administration

- U.S. Actions During Trump Administration

- Freedom of Navigation (FON) Operations in SCS

- Cost-Imposing Actions

- Potential Further U.S. Actions Suggested by Observers

- Strategy for Competing Strategically with China in SCS and ECS

- Overview

- Potential U.S. Goals in a Strategic Competition

- Some Additional Considerations Regarding Strategic Competition

- Trump Administration's Strategy for Competing Strategically

- Assessing the Trump Administration's Strategy

- Risk of United States Being Drawn into a Crisis or Conflict

- Whether United States Should Ratify UNCLOS

- Legislative Activity in

20182019

- FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act

for Fiscal Year 2019/John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (H.R. 5515/S. 2987/P.L. 115-232) - House Committee Report

- House Floor Action

- Senate

- Conference

- House

- South China Sea and East China Sea Sanctions Act of 2019 (H.R. 3508/S. 1634)

- House

- Senate

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Act of 2019 (S. 987)

- Senate

Figures

- Figure A-1. Maritime Territorial Disputes Involving China

- Figure A-2. Locations of 2001, 2002, and 2009 U.S.-Chinese Incidents at Sea and In

- Figure E-1. Map of the Nine-Dash Line

- Figure E-2. EEZs Overlapping Zone Enclosed by Map of Nine-Dash Line

- Figure

FG-1. EEZs in South China Sea and East China Sea - Figure

FG-2. Claimable World EEZs

Appendixes

- Appendix A.

Strategic Context from U.S. PerspectiveMaritime Territorial and EEZ Disputes in SCS and ECS

- Appendix B. U.S. Security Treaties with Japan and Philippines

- Appendix C. Treaties and Agreements Related to the Maritime Disputes

- Appendix D. July 2016 Tribunal Award in SCS Arbitration Case Involving Philippines and China

- Appendix E.

Additional Elements ofChina's Approach to Maritime Disputes Appendix Fin SCS and ECS- Appendix F. Assessments of China's Strengthening Position in SCS

Appendix G. U.S. Position on Operational Rights in EEZs- Appendix

G. Options Suggested by Observers for Strengthening U.S. Actions

Summary

In an international security environment described as one of renewed great power competition, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS forms an element of the Trump Administration's more confrontational overall approach toward China, and of the Administration's efforts for promoting its construct for the Indo-Pacific region, called the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).China's actions in recent years in the South China Sea (SCS)—particularly its island-building and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is rapidly gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners, particularly those in the Indo-Pacific region. U.S. Navy Admiral Philip Davidson, in his responses to advance policy questions from the Senate Armed Services Committee for an April 17, 2018, hearing to consider his nomination to become Commander, U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM), stated that "China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States." Chinese control of the SCS—and, more generally, Chinese domination of China's near-seas region, meaning the SCS, the East China Sea (ECS), andH. U.S. Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program

Summary

Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. security relationships with treaty allies and partner states; maintaining a regional balance of power favorable to the United States and its allies and partners; defending the principle of peaceful resolution of disputes and resisting the emergence of an alternative "might-makes-right" approach to international affairs; defending the principle of freedom of the seas, also sometimes called freedom of navigation; preventing China from becoming a regional hegemon in East Asia; and pursing these goals as part of a larger U.S. strategy for competing strategically and managing relations with China.

Potential specific U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: dissuading China from carrying out additional base-construction activities in the SCS, moving additional military personnel, equipment, and supplies to bases at sites that it occupies in the SCS, initiating island-building or base-construction activities at Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, declaring straight baselines around land features it claims in the SCS, or declaring an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS; and encouraging China to reduce or end operations by its maritime forces at the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, halt actions intended to put pressure against Philippine-occupied sites in the Spratly Islands, provide greater access by Philippine fisherman to waters surrounding Scarborough Shoal or in the Spratly Islands, adopt the U.S./Western definition regarding freedom of the seas, and accept and abide by the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China.

The Trump Administration has taken various actions for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS. The issue for Congress is whether the Trump Administration's strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both.

Introduction

This report provides background information and issues for Congress regarding U.S.-China strategic competition in the South China Sea (SCS) and East China Sea (ECS). In an international security environment described as one of renewed great power competition,1 the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS forms an element of the Trump Administration's more confrontational overall approach toward China, and of the Administration's efforts for promoting its construct for the Indo-Pacific region, called the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).2

China's actions in the SCS in recent years have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China's maritime forces at the Japan-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China's near-seas region3 could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.The issue for Congress is whether the Trump Administration's strategy for competing strategically with China in the SCS and ECS is appropriate and correctly resourced, and whether Congress should approve, reject, or modify the strategy, the level of resources for implementing it, or both. Decisions that Congress makes on these issues could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

For a brief overview of maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS that involve China, see "Maritime Territorial Disputes," below, and Appendix A. Other CRS reports provide additional and more detailed information on these disputes.4 Background U.S. Interests in SCS and ECSAlthough disputes in the SCS and ECS involving China and its neighbors may appear at first glance to be disputes between faraway countries over a few rocks and reefs in the ocean that are of seemingly little importance to the United States, the SCS and ECS can engage U.S. interests for a variety of strategic, political, and economic reasons, including but not necessarily limited to those discussed in the sections below.

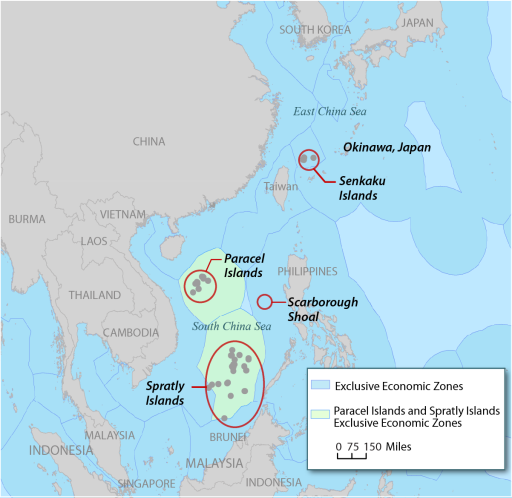

U.S. Regional Allies and Partners, and U.S. Regional Security Architecture The SCS, ECS, and Yellow Sea border three U.S. treaty allies: Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines. (For additional information on the U.S. security treaties with Japan the Philippines, see Appendix B.)China is a party to multiple territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS, including, in particular, disputes with multiple neighboring countries over the Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, and Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, and with Japan over the Senkaku Islands in the ECS. Up through 2014, U.S. concern over these disputes centered more on their potential for causing tension, incidents, and a risk of conflict between China and its neighbors in the region, including U.S. allies Japan and the Philippines and emerging partner states such as Vietnam. While that concern remains, particularly regarding the potential for a conflict between China and Japan involving the Senkaku Islands, U.S. concern since 2014 (i.e., since China's island-building activities in the Spratly Islands were first publicly reported) has shifted increasingly to how China's strengthening position in the SCS may be affecting the risk of a U.S.-China crisis or conflict in the SCS and the broader U.S.-Chinese strategic competition.

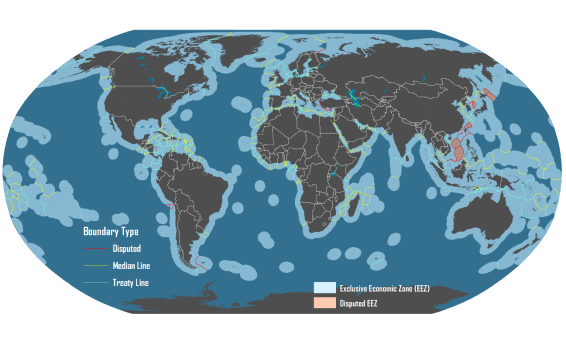

In addition to territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS, China is involved in a dispute, particularly with the United States, over whether China has a right under international law to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating within China's exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The position of the United States and most other countries is that while international law gives coastal states the right to regulate economic activities (such as fishing and oil exploration) within their EEZs, it does not give coastal states the right to regulate foreign military activities in the parts of their EEZs beyond their 12-nautical-mile territorial waters. The position of China and some other countries (i.e., a minority group among the world's nations) is that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities, but also foreign military activities, in their EEZs. The dispute appears to be at the heart of multiple incidents between Chinese and U.S. ships and aircraft in international waters and airspace since 2001, and has potential implications not only for China's EEZs, but for U.S. naval operations in EEZs globally, and for international law of the sea.

A key issue for Congress is how the United States should respond to China's actions in the SCS and ECS—particularly its island-building and base-construction activities in the Spratly Islands—and to China's strengthening position in the SCS. A key oversight question for Congress is whether the Trump Administration has an appropriate strategy—and an appropriate amount of resources for implementing that strategy—for countering China's "salami-slicing" strategy or gray zone operations for gradually strengthening its position in the SCS, for imposing costs on China for its actions in the SCS and ECS, and for defending and promoting U.S. interests in the region.

Introduction

Focus of Report

This report provides background information and issues for Congress regarding China's actions in the South China Sea (SCS) and East China Sea (ECS), with a focus on implications for U.S. strategic and policy interests. Other CRS reports focus on other aspects of maritime territorial disputes involving China.1

Issue for Congress

The issue for Congress is how the United States should respond to China's actions in the SCS and ECS—particularly China's island-building and base-construction activities in the Spratly Islands in the SCS—and to China's strengthening position in the SCS. A key oversight question for Congress is whether the Trump Administration has an appropriate strategy—and an appropriate amount of resources for implementing that strategy—for countering China's "salami-slicing" strategy or gray zone operations for gradually strengthening its position in the SCS, for imposing costs on China for its actions in the SCS and ECS, and for defending and promoting U.S. interests in the region. Decisions that Congress makes on these issues could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere.

Terminology Used in This Report

In this report, the term China's near-seas region refers to the SCS, ECS, and Yellow Sea.2 The term first island chain refers to a string of islands, including Japan and the Philippines, that encloses China's near-seas region. The term second island chain, which reaches out to Guam, refers to a line that can be drawn that encloses both China's near-seas region and the Philippine Sea between the Philippines and Guam.3 The term exclusive economic zone (EEZ) dispute is used in this report to refer to a dispute principally between China and the United States over whether coastal states have a right under international law to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating in their EEZs.4

Background

U.S. Interests in SCS and ECS

Although maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS involving China and its neighbors may appear at first glance to be disputes between faraway countries over a few rocks and reefs in the ocean that are of seemingly little importance to the United States, the situation in the SCS and ECS can engage U.S. interests for a variety of strategic, political, and economic reasons, including but not necessarily limited to those discussed in the sections below.5

U.S. Regional Allies and Partners, and U.S. Regional Security Architecture

The SCS, ECS, and Yellow Sea border three U.S. treaty allies—Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines. In addition, the SCS and ECS (including the Taiwan Strait) surround Taiwan, regarding which the United States has certain security-related policies under the Taiwan Relations Act (H.R. 2479/P.L. 96-8 of April 10, 1979), and the SCS borders Southeast Asian nations that are current, emerging, or potential U.S. partner countries, such as Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

In a conflict with the United States, Chinese bases in the SCS and forces operating from them would add to a regional network of Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) forcescapabilities intended to keep U.S. military forces outside the first island chain (and thus away from China's mainland). Among other things, and Taiwan).5 Chinese bases in the SCS and forces operating from them could also help create a bastion (i.e., a defended operating sanctuary) in the SCS for China's emerging sea-based strategic deterrent force of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). In a conflict with the United States, Chinese bases in the SCS and forces operating from them would be vulnerable to U.S. attack. Attacking the bases and the forces operating from them, however, would tie down the attacking U.S. forces for a time at least, delaying the use of those U.S. forces elsewhere in a larger conflict, and potentially delay the advance of U.S. forces into the SCS.

Short of a conflict with the United States, Chinese bases in the SCS, and more generally, Chinese domination over or control of its near-seas region could help China to do one or more of the following on a day-to-day basis:

- control fishing operations and oil and gas exploration activities in the SCS;

- coerce, intimidate, or put political pressure on other countries bordering on the SCS;

- announce and enforce an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the SCS;

- announce and enforce a maritime exclusion zone (i.e., a blockade) around Taiwan;6

- facilitate the projection of Chinese military presence and political influence further into the Western Pacific; and

- help achieve a broader goal of becoming a regional hegemon in its part of Eurasia.

7

In light of some of the preceding points, Chinese bases in the SCS, and more generally, Chinese domination over or control of its near-seas region could complicate the ability of the United States to

- intervene militarily in a crisis or conflict between China and Taiwan;

- fulfill U.S. obligations under U.S. defense treaties with Japan and the Philippines and South Korea;

8 - operate U.S. forces in the Western Pacific for various purposes, including maintaining regional stability, conducting engagement and partnership-building operations, responding to crises, and executing war plans; and

- prevent the emergence of China as a regional hegemon in its part of Eurasia.

9

7A reduced U.S. ability to do one or more of the above could encourage countries in the region to reexamine their own defense programs and foreign policies, potentially leading to a further change in the region's security architecture. Some observers believe that China is trying to use disputes in the SCS and ECS to raise doubts among U.S. allies and partners in the region about the dependability of the United States as an ally or partner, or to otherwise drive a wedge between the United States and its regional allies and partners, so as to weaken the U.S.-led regional security architecture and thereby facilitate greater Chinese influence over the region.

Some observers remain concerned that maritime territorial disputes in the ECS and SCS could lead to a crisis or conflict between China and a neighboring country such as Japan or the Philippines, and that the United States could be drawn into such a crisis or conflict as a result of obligations the United States has under bilateral security treaties with Japan and the Philippines.10 Most recently, those concerns have focused more on the possibility of a crisis or conflict between China and Japan over the Senkaku Islands.

Principle of Nonuse of Force or Coercion

A key element of the U.S.-led international order that has operated since World War II is the principle that force or coercion should not be used as a means of settling disputes between countries, and certainly not as a routine or first-resort method. Some observers are concerned that China's actions in SCS and ECS challenge this principle and—along with Russia's actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine—could help reestablish the very different principle of "might makes right" (i.e., the law of the jungle) as a routine or defining characteristic of international relations.11

Principle of Freedom of the Seas

Overview

Another key element of the U.S.-led international order that has operated since World War II is the principle of freedom of the seas, meaning the treatment of the world's seas under international law as international waters (i.e., as a global commons), and the principle of freedom of operations in international waters. The principle of freedom of operations in international waters is often referred to in shorthand as freedomFreedom of the seas. It is also is sometimes referred to as freedom of navigation, although thisthe term can befreedom of navigation is sometimes defined—particularly by parties who might not support freedom of the seas—in a narrow fashion, to include merely the freedom for commercial ships to navigate (i.e., pass through) sea areas, as opposed to the freedom for both commercial and naval ships civilian and military ships and aircraft to conduct various activities at sea or in the airspace above. A more complete way to refer to the principle of freedom of the seas, as stated in the Department of Defense's (DOD's) annual Freedom of Navigation (FON) report, is "all of the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea and airspace, including for military ships and aircraft, guaranteed to all nations under international law."12 The principle of freedom of the seas dates back hundreds of years.13

includes more than the mere freedom of commercial vessels to transit through international waterways. While not a defined term under international law, the Department uses "freedom of the seas" to mean all of the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea and airspace, including for military ships and aircraft, recognized under international law. Freedom of the seas is thus also essential to ensure access in the event of a crisis.10 The principle of freedom of the seas dates back about 400 years, to the early 1600s,11 and has long been a matter of importance to the United States. DOD states that Throughout its history, the United States has asserted a key national interest in preserving the freedom of the seas, often calling on its military forces to protect that interest. Following independence, one of the U.S. Navy's first missions was to defend U.S. commercial vessels in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea from pirates and other maritime threats. The United States went to war in 1812, in part, to defend its citizens' rights to commerce on the seas. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson named "absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas" as one of the universal principles for which the United States and other nations were fighting World War I. Similarly, before World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt declared that our military forces had a "duty of maintaining the American policy of freedom of the seas."12Some observers are concerned that China's actions in the SCS appear to challenge the principle that the world's seas are to be treated under international law as international waters. If such a challenge were to gain acceptance in the SCS region, it would have broad implications for the United States and other countries the rights, freedoms, and uses of the sea and airspace guaranteed to all nations by international law."9 DOD states that freedom of the seas

China's Position

Some observers are concerned that China's interpretation of law of the sea and its actions in the SCS pose a significant challenge to the principle of freedom of the seas. Matters of particular concern in this regard include China's nine-dash line in the SCS, China's apparent narrow definition of freedom of navigation, and China's position that coastal states have the right to regulate the activities of foreign military forces in their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) (see "China's Approach to the SCS and ECS," below, and Appendix A and Appendix E).13

Observers are concerned that a challenge to freedom of the seas in the SCS could have implications for the United States not only in the SCS, but around the world, because international law is universal in application, and a challenge to a principle of international law in one part of the world, if accepted, could serve as a precedent for challenging it in other parts of the world. Overturning the principle of freedom of the seas, so that significant portions of the seas could be appropriated as national territory, would overthrow hundreds of years of international legal tradition relating to the legal status of the world's oceans and significantly changeIn general, limiting or weakening the principle of freedom of the seas could represent a departure or retreat from the roughly 400-year legal tradition of treating the world's oceans as international waters (i.e., as a global commons) and as a consequence alter the international legal regime governing sovereignty over much of the surface of the world.14

Some observers are concerned that if China's position thatMore specifically, if China's position on the issue of whether coastal states have a right under international law the right to regulate the activities of foreign military forces in their EEZs were to gain greater international acceptance under international law, it could substantially affect U.S. naval operations not only in the SCS and ECS, but around the world, which in turn could substantially affect the ability of the United States to use its military forces to defend various U.S. interests overseas. Significant portions of the world's oceans are claimable as EEZs, including high-priority U.S. Navy operating areas in the Western Pacific, the Persian Gulf, and the Mediterranean Sea.15 The legal right of U.S. naval forces to operate freely in EEZ waters—an application of the principle of freedom of the seas—is important to their ability to perform many of their missions around the world, because many of those missions are aimed at influencing events ashore, and having to conduct operations from outside a country's EEZ (i.e., more than 200 miles offshore) would reduce the inland reach and responsiveness of U.S. ship-based sensors, aircraft, and missiles, and make it more difficult for the United States to transport Marines and their equipment from ship to shore. Restrictions on the ability of U.S. naval forces to operate in EEZ waters could potentially require changes (possibly very significant ones) in U.S. military strategy or, U.S. foreign policy goals, or U.S. grand strategy.16

Trade Routes and Hydrocarbons

Major commercial shipping routes pass through the SCS, which links the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. An estimated $3.4 trillion worth of international shipping trade passes through the SCS each year.17 DOD states that "the South China Sea plays an important role in security considerations across East Asia because Northeast Asia relies heavily on the flow of oil and commerce through South China Sea shipping lanes, including more than 80 percent of the crude oil [flowing] to Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan."18 In addition, the ECS and SCS contain potentially significant oil and gas exploration areas.19 Exploration activities there could potentially involve U.S. firms. The results of exploration activities there could eventually affect world oil prices.

20Interpreting China's Rise as a Major World Power

As China continues to emerge as a major world power, observers are assessing what kind of international actor China will ultimately be. China's actions in the SCS and ECS could influence assessments that observers might make on issues such asRole as a Major World Power

China's actions in the SCS and ECS could influence assessments that U.S. and other observers make about China's role as a major world power, particularly regarding China's approach to settling disputes between states (including whether China views force and coercion as acceptable means for settling such disputes, and consequently whether China believes that "might makes right"), China's views toward the meaning and application of international law,20 and whether China views itself more as a stakeholder and defender of the current international order, or alternatively, more as a revisionist power that will seek to change elements of that order that it does not like.

U.S.-China Relations in General

Developments in the SCS and ECS could affect U.S.-China relations in general, which could have implications for other issues in U.S.-China relations.21

Overview of Maritime Disputes in SCS and ECS

Maritime Territorial and EEZ Disputes Involving China

This section provides a brief overview of maritime territorial and EEZ disputes involving China. For additional details on these disputes (including maps), see Appendix A. In addition, other CRS reports provide additional and more detailed information on the maritime territorial disputes.22 For background information on treaties and international agreements related to the disputes, see Appendix C. For background information on a July 2016 international tribunal award in an SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China, see Appendix D.

Maritime Territorial Disputes

China is a party to multiple maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS, including in particular the following (see Figure 1 for locations of the island groups listed below):

- a dispute over the Paracel Islands in the SCS, which are claimed by China and Vietnam, and occupied by China;

- a dispute over the Spratly Islands in the SCS, which are claimed entirely by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam, and in part by the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei, and which are occupied in part by all these countries except Brunei;

- a dispute over Scarborough Shoal in the SCS, which is claimed by China, Taiwan, and the Philippines, and controlled since 2012 by China; and

- a dispute over the Senkaku Islands in the ECS, which are claimed by China, Taiwan, and Japan, and administered by Japan.

The island and shoal names used above are the ones commonly used in the United States; in other countries, these islands are known by various other names.22

These island groups are not the only land features in the SCS and ECS—the two seas feature other islands, rocks, and shoals, as well as some near-surface submerged features. The territorial status of some of these other features is also in dispute.23 There are additional maritime territorial disputes in the Western Pacific that do not involve China.24 Maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS date back many years, and have periodically led to diplomatic tensions as well as confrontations and incidents at sea involving fishing vessels, oil exploration vessels and oil rigs, coast guard ships, naval ships, and military aircraft.25

Dispute Regarding China's Rights within Its EEZ, and Associated U.S.-Chinese Incidents at Sea

In addition to maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS, China is involved in a dispute, principally with the United States, over whether China has a right under international law to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating within China's EEZ. The position of the United States and most other countries is that while the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which established EEZs as a feature of international law, gives coastal states the right to regulate economic activities (such as fishing and oil exploration) within their EEZs, it does not give coastal states the right to regulate foreign military activities in the parts of their EEZs beyond their 12-nautical-mile territorial waters.26

The position of China and some other countries (i.e., a minority group among the world's nations) is that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities, but also foreign military activities, in their EEZs. In response to a request from CRS to identify the countries taking this latter position, the U.S. Navy states that

countries with restrictions inconsistent with the Law of the Sea Convention [i.e., UNCLOS] that would limit the exercise of high seas freedoms by foreign navies beyond 12 nautical miles from the coast are [the following 27]:

Bangladesh, Brazil, Burma, Cambodia, Cape Verde, China, Egypt, Haiti, India, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, North Korea, Pakistan, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Vietnam.27

Other observers provide different counts of the number of countries that take the position that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities but also foreign military activities in their EEZs. For example, one set of observers, in an August 2013 briefing, stated that 18 countries seek to regulate foreign military activities in their EEZs, and that 3 of these countries—China, North Korea, and Peru—have directly interfered with foreign military activities in their EEZs.28

The dispute over whether China has a right under UNCLOS to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating within its EEZ appears to be at the heart of incidents between Chinese and U.S. ships and aircraft in international waters and airspace, including

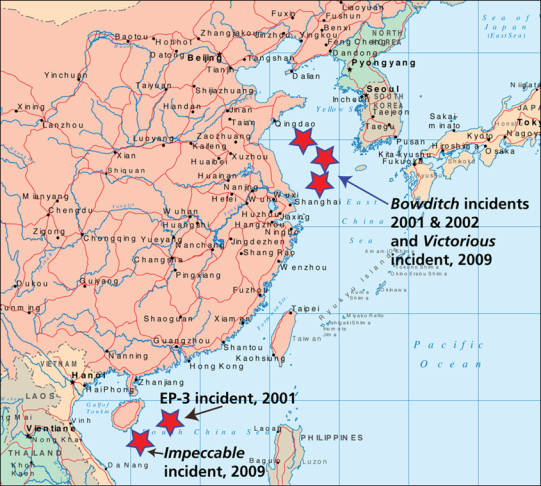

- incidents in March 2001, September 2002, March 2009, and May 2009, in which Chinese ships and aircraft confronted and harassed the U.S. naval ships Bowditch, Impeccable, and Victorious as they were conducting survey and ocean surveillance operations in China's EEZ;

- an incident on April 1, 2001, in which a Chinese fighter collided with a U.S. Navy EP-3 electronic surveillance aircraft flying in international airspace about 65 miles southeast of China's Hainan Island in the South China Sea, forcing the EP-3 to make an emergency landing on Hainan Island;29

- an incident on December 5, 2013, in which a Chinese navy ship put itself in the path of the U.S. Navy cruiser Cowpens as it was operating 30 or more miles from China's aircraft carrier Liaoning, forcing the Cowpens to change course to avoid a collision;

- an incident on August 19, 2014, in which a Chinese fighter conducted an aggressive and risky intercept of a U.S. Navy P-8 maritime patrol aircraft that was flying in international airspace about 135 miles east of Hainan Island30—DOD characterized the intercept as "very, very close, very dangerous";31 and

- an incident on May 17, 2016, in which Chinese fighters flew within 50 feet of a Navy EP-3 electronic surveillance aircraft in international airspace in the South China Sea—a maneuver that DOD characterized as "unsafe."32

Figure 2 shows the locations of the 2001, 2002, and 2009 incidents listed in the first two bullets above. The incidents shown in Figure 2 are the ones most commonly cited prior to the December 2013 involving the Cowpens, but some observers list additional incidents as well.33

DOD stated in 2015 that

The growing efforts of claimant States to assert their claims has led to an increase in air and maritime incidents in recent years, including an unprecedented rise in unsafe activity by China's maritime agencies in the East and South China Seas. U.S. military aircraft and vessels often have been targets of this unsafe and unprofessional behavior, which threatens the U.S. objectives of safeguarding the freedom of the seas and promoting adherence to international law and standards. China's expansive interpretation of jurisdictional authority beyond territorial seas and airspace causes friction with U.S. forces and treaty allies operating in international waters and airspace in the region and raises the risk of inadvertent crisis.

There have been a number of troubling incidents in recent years. For example, in August 2014, a Chinese J-11 fighter crossed directly under a U.S. P-8A Poseidon operating in the South China Sea approximately 117 nautical miles east of Hainan Island. The fighter also performed a barrel roll over the aircraft and passed the nose of the P-8A to show its weapons load-out, further increasing the potential for a collision. However, since August 2014, U.S.-China military diplomacy has yielded positive results, including a reduction in unsafe intercepts. We also have seen the PLAN implement agreed-upon international standards for encounters at sea, such as the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES),34 which was signed in April 2014.35

A recent incident in the SCS occurred on September 30, 2018, between the U.S. Navy destroyer Decatur (DDG-73) and a Chinese destroyer, as the Decatur was conducting a freedom of navigation (FON) operation near Gaven Reef in the Spratly Islands. In the incident, the Chinese destroyer overtook the U.S. destroyer close by on the U.S. destroyer's port (i.e., left) side, requiring the U.S. destroyer to turn starboard (i.e., to the right) to avoid the Chinese ship. U.S. officials stated that at the point of closest approach between the two ships, the stern (i.e., back end) of the Chinese ship came within 45 yards (135 feet) of the bow (i.e., front end) of the Decatur. As the encounter was in progress, the Chinese ship issued a warning by radio stating, "If you don't change course your [sic] will suffer consequences." One observer, commenting on the incident, stated, "To my knowledge, this is the first time we've had a direct threat to an American warship with that kind of language." U.S. officials characterized the actions of the Chinese ship in the incident as "unsafe and unprofessional."36

A November 3, 2018, press report states the following:

The US Navy has had 18 unsafe or unprofessional encounters with Chinese military forces in the Pacific since 2016, according to US military statistics obtained by CNN.

"We have found records of 19 unsafe and/or unprofessional interactions with China and Russia since 2016 (18 with China and one with Russia)," Cmdr. Nate Christensen, a spokesman for the US Pacific Fleet, told CNN.

A US official familiar with the statistics told CNN that 2017, the first year of the Trump administration, saw the most unsafe and or unprofessional encounters with Chinese forces during the period.

At least three of those incidents took place in February, May and July of that year and involved Chinese fighter jets making what the US considered to be "unsafe" intercepts of Navy surveillance planes.

While the 18 recorded incidents only involved US naval forces, the Air Force has also had at least one such encounter during this period….

The US Navy told CNN that, in comparison, there were 50 unsafe or unprofessional encounters with Iranian military forces since 2016, with 36 that year, 14 last year and none in 2018. US and Iranian naval forces tend to operate in relatively narrow stretches of water, such as the Strait of Hormuz, increasing their frequency of close contact.37

DOD states that

Although China has long challenged foreign military activities in its maritime zones in a manner that is inconsistent with the rules of customary international law as reflected in the LOSC, the PLA has recently started conducting the very same types of military activities inside and outside the first island chain in the maritime zones of other countries. This contradiction highlights China's continued lack of commitment to the rules of customary international law.

Even though China is a state party to the LOSC [i.e., UNCLOS], China's domestic laws restrict military activities in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), including intelligence collection and military surveys, contrary to LOSC. At the same time, the PLA is increasingly undertaking military operations in other countries' EEZs. The map on the following page [not reproduced here] depicts new PLA operating areas in foreign EEZs since 2014. In 2017, the PLAN conducted air and naval operations in Japan's EEZ; employed an AGI [intelligence-gathering ship] ship, likely to monitor testing of a THAAD system in the U.S. EEZ near the Aleutian Islands; and employed an AGI ship to monitor a multi-national naval exercise in Australia's EEZ. PLA operations in foreign EEZs have taken place in Northeast and Southeast Asia, and a growing number of operations are also occurring farther from Chinese shores.38

In addition to maritime territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS, China is involved in a dispute, principally with the United States, over whether China has a right under international law to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating within China's EEZ. The position of the United States and most other countries is that while the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which established EEZs as a feature of international law, gives coastal states the right to regulate economic activities (such as fishing and oil exploration) within their EEZs, it does not give coastal states the right to regulate foreign military activities in the parts of their EEZs beyond their 12-nautical-mile territorial waters.24 The position of China and some other countries (i.e., a minority group among the world's nations) is that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities, but also foreign military activities, in their EEZs. The dispute over whether China has a right under UNCLOS to regulate the activities of foreign military forces operating within its EEZ appears to be at the heart of incidents between Chinese and U.S. ships and aircraft in international waters and airspace dating back at least to 2001.

Relationship of Maritime Territorial Disputes to EEZ Dispute

The issue of whether China has the right under UNCLOS to regulate foreign military activities in its EEZ is related to, but ultimately separate from, the issue of territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS:

- The two issues are related because China can claim EEZs from inhabitable islands over which it has sovereignty, so accepting China's claims to sovereignty over inhabitable islands in the SCS or ECS could permit China to expand the EEZ zone within which China claims a right to regulate foreign military activities.

- The two issues are ultimately separate from one another because even if all the territorial disputes in the SCS and ECS were resolved, and none of China's claims in the SCS and ECS were accepted, China could continue to apply its concept of its EEZ rights to the EEZ that it unequivocally derives from its mainland coast—and it is in this unequivocal Chinese EEZ that several of the past U.S.-Chinese incidents at sea have occurred.

Press reports of maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS sometimes focus on territorial disputes while devoting little or no attention to the EEZ dispute, or do relatively little to distinguish the EEZ dispute from the territorial disputes. From the U.S. perspective, the EEZ dispute is arguably as significant as the maritime territorial disputes because of the EEZ dispute's proven history of leading to U.S.-Chinese incidents at sea and because of its potential for affecting U.S. military operations not only in the SCS and ECS, but around the world.

For background information on treaties and international agreements related to the disputes, see Appendix C.

For background information on the July 2016 tribunal award in the SCS arbitration case involving the Philippines and China concerning maritime territorial issues in the SCS, see Appendix D.

China's Approach to the SCS and ECS

In General

In general, China's approach to the China's Approach to the SCS and ECS

This section provides a brief overview of China's approach to the SCS and ECS. For additional information on China's approach to the SCS and ECS, see Appendix E.

In General

China's approach to maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS, and to strengthening its position over time in the SCS, can be characterized in general as follows:

- China appears to have identified the assertion and defense of its maritime territorial claims in the SCS and ECS, and the strengthening of its position in the SCS, as important national goals.

- To achieve these goals, China appears to be employing an integrated, whole-of-society strategy that includes diplomatic, informational, economic, military, paramilitary/law enforcement, and civilian elements.

3925

- In implementing this integrated strategy, China appears to be persistent, patient, tactically flexible, willing to expend significant resources, and willing to absorb at least some amount of reputational and other costs that other countries might seek to impose on China in response to China's actions.

"Salami-Slicing" Strategy and Gray Zone Operations

Observers frequently characterize China's approach to the SCS and ECS as a "salami-slicing" strategy that employs a series of incremental actions, none of which by itself is a casus belli, to gradually change the status quo in China's favor. At least one Chinese official has used the term "cabbage strategy" to refer to a strategy of consolidating control over disputed islands by wrapping those islands, like the concentric leaves of a cabbage, in successive layers of occupation and protection formed by fishing boats, Chinese Coast Guard ships, and then finally Chinese naval ships.40 Other observers have referred to China's approach as a strategy of gray zone operations (i.e., operations that reside in a gray zone between peace and war), of creeping annexation4126 or creeping invasion,4227 or as a "talk and take" strategy, meaning a strategy in which China engages in (or draws out) negotiations while taking actions to gain control of contested areas.43

Island Building and Base Construction

Perhaps more than any other set of actions, China's island-building (aka land-reclamation) and base-construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Paracel Islands and Spratly Islands in the SCS have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is rapidly gaining effective control of the SCS. China's large-scale island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS appear to have begun around December 2013, and were publicly reported starting in May 2014. Awareness of, and concern about, the activities appears to have increased substantially following the posting of a February 2015 article showing a series of "before and after" satellite photographs of islands and reefs being changed by the work.44

China occupies seven sites in the Spratly Islands. It has engaged in island-building and facilities-construction activities at most or all of these sites, and particularly at three of them—Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef, all of which now feature lengthy airfields as well as substantial numbers of buildings and other structures. Although other countries, such as Vietnam, have engaged in their own island-building and facilities-construction activities at sites that they occupy in the SCS, these efforts are dwarfed in size by China's island-building and base-construction activities in the SCS.45 DOD stated in 2017 that

In 2016, China focused its main effort on infrastructure construction at its outposts on the Spratly Islands. Although its land reclamation and artificial islands do not strengthen China's territorial claims as a legal matter or create any new territorial sea entitlements, China will be able to use its reclaimed features as persistent civil-military bases to enhance its presence in the South China Sea and improve China's ability to control the features and nearby maritime space. China reached milestones of landing civilian aircraft on its airfields on Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef for the first time in 2016, as well as landing a military transport aircraft on Fiery Cross Reef to evacuate injured personnel....

China's Spratly Islands outpost expansion effort is currently focused on building out the land-based capabilities of its three largest outposts—Fiery Cross, Subi, and Mischief Reefs—after completion of its four smaller outposts early in 2016. No substantial land has been reclaimed at any of the outposts since China ended its artificial island creation in the Spratly Islands in late 2015 after adding over 3,200 acres of land to the seven features it occupies in the Spratlys. Major construction features at the largest outposts include new airfields—all with runways at least 8,800 feet in length—large port facilities, and water and fuel storage. As of late 2016, China was constructing 24 fighter-sized hangars, fixed-weapons positions, barracks, administration buildings, and communication facilities at each of the three outposts. Once all these facilities are complete, China will have the capacity to house up to three regiments of fighters in the Spratly Islands.

China has completed shore-based infrastructure on its four smallest outposts in the Spratly Islands: Johnson, Gaven, Hughes, and Cuarteron Reefs. Since early 2016, China has installed fixed, land-based naval guns on each outpost and improved communications infrastructure.

The Chinese Government has stated that these projects are mainly for improving the living and working conditions of those stationed on the outposts, safety of navigation, and research; however, most analysts outside China believe that the Chinese Government is attempting to bolster its de facto control by improving its military and civilian infrastructure in the South China Sea. The airfields, berthing areas, and resupply facilities on its Spratly outposts will allow China to maintain a more flexible and persistent coast guard and military presence in the area. This would improve China's ability to detect and challenge activities by rival claimants or third parties, widen the range of capabilities available to China, and reduce the time required to deploy them....

China's construction in the Spratly Islands demonstrates China's capacity—and a newfound willingness to exercise that capacity—to strengthen China's control over disputed areas, enhance China's presence, and challenge other claimants....

In 2016, China built reinforced hangars on several of its Spratly Island outposts in the South China Sea. These hangars could support up to 24 fighters or any other type of PLA aircraft participating in force projection operations.46

In April, May, and June 2018, it was reported that China has landed aircraft and moved electronic jamming equipment, surface-to-air missiles, and anti-ship missile systems to its newly built facilities in the SCS.47 In July 2018, it was reported that "China is quietly testing electronic warfare assets recently installed at fortified outposts in the South China Sea…."48 Also in July 2018, Chinese state media announced that a Chinese search and rescue ship had been stationed at Subi Reef—the first time that such a ship had been permanently stationed by China at one of its occupied sites in the Spratly Islands.49

For additional discussion of China's island-building and facility-construction activities, see CRS Report R44072, Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options, by Ben Dolven et al.

Other Chinese Actions That Have Heightened Concerns

In addition to the island-building and base-construction activities discussed above, additional Chinese actions in the SCS and ECS that have heightened concerns among U.S. observers. Following a confrontation in 2012 include the following, among others:China's actions in 2012, following a confrontation between Chinese and Philippine ships at Scarborough Shoal, China gained in the SCS, to gain de facto control over access to the shoal and its fishing grounds. Subsequent Chinese actions that have heightened concerns among U.S. observers, particularly since late 2013, include the following, among others:

- ;

China's announcement on November 23, 2013, of an air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the ECS that includes airspace over the Senkaku Islands;

5031

- frequent patrols by Chinese Coast Guard ships—some observers refer to them as harassment operations—at the Senkaku Islands;

- Chinese pressure against the small Philippine military presence at Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly Islands, where a handful of Philippine military personnel occupy a beached (and now derelict) Philippine navy amphibious ship;

51 - the implementation on January 1, 2014, of fishing regulations administered by China's Hainan province applicable to waters constituting more than half of the SCS, and the reported enforcement of those regulations with actions that have included the apprehension of non-Chinese fishing boats;52 and

- a growing civilian Chinese presence on some of the sites in the SCS occupied by China in the SCS, including both Chinese vacationers and (in the Paracels) permanent settlements; and the movement of some military systems to its newly built bases in the SCS.

Use of Coast Guard Ships and Maritime Militia

China asserts and defends its maritime claims not only with navy shipsits navy, but also with its coast guard cutters andand its maritime militia vessels. Indeed, China employs its coast guard and maritime militia more regularly and extensively than its navy in its maritime sovereignty-assertion operations. DOD states that China's navy, coast guard, and maritime militia together "form the largest maritime force in the Indo-Pacific."53

Coast Guard Ships

DOD states that the China Coast Guard (CCG) is the world's largest coast guard.54 It is much larger than the coast guard of any country in the region, and it has increased substantially in size in recent years through the addition of many newly built ships. China makes regular use of CCG ships to assert and defend its maritime claims, particularly in the ECS, with Chinese navy ships sometimes available over the horizon as backup forces.55 The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) states the following:

Under Chinese law, maritime sovereignty is a domestic law enforcement issue under the purview of the CCG. Beijing also prefers to use CCG ships for assertive actions in disputed waters to reduce the risk of escalation and to portray itself more benignly to an international audience. For situations that Beijing perceives carry a heightened risk of escalation, it often deploys PLAN combatants in close proximity for rapid intervention if necessary. China also relies on the PAFMM—a paramilitary force of fishing boats—for sovereignty enforcement actions….

China primarily uses civilian maritime law enforcement agencies in maritime disputes, employing the PLAN [i.e., China's navy] in a protective capacity in case of escalation.

The CCG has rapidly increased and modernized its forces, improving China's ability to enforce its maritime claims. Since 2010, the CCG's large patrol ship fleet (more than 1,000 tons) has more than doubled in size from about 60 to more than 130 ships, making it by far the largest coast guard force in the world and increasing its capacity to conduct extended offshore operations in a number of disputed areas simultaneously. Furthermore, the newer ships are substantially larger and more capable than the older ships, and the majority are equipped with helicopter facilities, high-capacity water cannons, and guns ranging from 30-mm to 76-mm. Among these ships, a number are capable of long-distance, long-endurance out-of-area operations. In addition, the CCG operates more than 70 fast patrol combatants ([each displacing] more than 500 tons), which can be used for limited offshore operations, and more than 400 coastal patrol craft (as well as about 1,000 inshore and riverine patrol boats). By the end of the decade, the CCG is expected to add up to 30 patrol ships and patrol combatants before the construction program levels off.56

In March 2018, China announced that control of the CCG would be transferred from the civilian State Oceanic Administration to the Central Military Commission.57 The transfer occurred on July 1, 2018.58 On May 22, 2018, it was reported that China's navy and the CCG had conducted their first joint patrols in disputed waters off the Paracel Islands in the SCS, and had expelled at least 10 foreign fishing vessels from those waters.59

Maritime Militia

China also uses the People's Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM)—a force that essentially consists of fishing ships with armed crew members—to defend its maritime claims. In the view of some observers, the PAFMM—even more than China's navy or coast guard—is the leading component of China's maritime forces for asserting its maritime claims, particularly in the SCS. U.S. analysts in recent years have paid increasing attention to the role of the PAFMM as a key tool for implementing China's salami-slicing strategy, and have urged U.S. policymakers to focus on the capabilities and actions of the PAFMM.60

DOD states that "the PAFMM is the only government-sanctioned maritime militia in the world," and that it "has organizational ties to, and is sometimes directed by, China's armed forces."61 DIA states that

The PAFMM is a subset of China's national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization to perform basic support duties. Militia units organize around towns, villages, urban subdistricts, and enterprises, and they vary widely from one location to another. The composition and mission of each unit reflects local conditions and personnel skills. In the South China Sea, the PAFMM plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China's political goals without fighting, part of broader Chinese military doctrine that states that confrontational operations short of war can be an effective means of accomplishing political objectives.

A large number of PAFMM vessels train with and support the PLA and CCG in tasks such as safeguarding maritime claims, protecting fisheries, and providing logistic support, search and rescue (SAR), and surveillance and reconnaissance. The Chinese government subsidizes local and provincial commercial organizations to operate militia ships to perform "official" missions on an ad hoc basis outside their regular commercial roles. The PAFMM has played a noteworthy role in a number of military campaigns and coercive incidents over the years, including the harassment of Vietnamese survey ships in 2011, a standoff with the Philippines at Scarborough Reef in 2012, and a standoff involving a Chinese oil rig in 2014. In the past, the PAFMM rented fishing boats from companies or individual fisherman, but it appears that China is building a state-owned fishing fleet for its maritime militia force in the South China Sea. Hainan Province, adjacent to the South China Sea, ordered the construction of 84 large militia fishing boats with reinforced hulls and ammunition storage for Sansha City, and the militia took delivery by the end of 2016.62

Apparent Narrow Definition of "Freedom of Navigation"

China regularly states that it supports freedom of navigation and has not interfered with freedom of navigation. China, however, appears to hold a narrow definition of freedom of navigation that is centered on the ability of commercial cargo ships to pass through international waters. In contrast to the broader U.S./Western definition of freedom of navigation (aka freedom of the seas), the Chinese definition does not appear to include operations conducted by military ships and aircraft. It can also be noted that China has frequently interfered with commercial fishing operations by non-Chinese fishing vessels—something that some observers would regard as a form of interfering with freedom of navigation for commercial ships. An August 12, 2015, press report states the following (emphasis added):

China respects freedom of navigation in the disputed South China Sea but will not allow any foreign government to invoke that right so its military ships and planes can intrude in Beijing's territory, the Chinese ambassador [to the Philippines] said.

Ambassador Zhao Jianhua said late Tuesday [August 11] that Chinese forces warned a U.S. Navy P-8A [maritime patrol aircraft] not to intrude when the warplane approached a Chinese-occupied area in the South China Sea's disputed Spratly Islands in May....

"We just gave them warnings, be careful, not to intrude," Zhao told reporters on the sidelines of a diplomatic event in Manila....

When asked why China shooed away the U.S. Navy plane when it has pledged to respect freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, Zhao outlined the limits in China's view.

"Freedom of navigation does not mean to allow other countries to intrude into the airspace or the sea which is sovereign. No country will allow that," Zhao said. "We say freedom of navigation must be observed in accordance with international law. No freedom of navigation for warships and airplanes."63

A July 19, 2016, press report states the following:

A senior Chinese admiral has rejected freedom of navigation for military ships, despite views held by the United States and most other nations that such access is codified by international law.

The comments by Adm. Sun Jianguo, deputy chief of China's joint staff, come at a time when the U.S. Navy is particularly busy operating in the South China Sea, amid tensions over sea and territorial rights between China and many of its neighbors in the Asia-Pacific region.

"When has freedom of navigation in the South China Sea ever been affected? It has not, whether in the past or now, and in the future there won't be a problem as long as nobody plays tricks," Sun said at a closed forum in Beijing on Saturday, according to a transcript obtained by Reuters.

"But China consistently opposes so-called military freedom of navigation, which brings with it a military threat and which challenges and disrespects the international law of the sea," Sun said.64

A March 4, 2017, press report states the following:

Wang Wenfeng, a US affairs expert at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, said Beijing and Washington obviously had different definitions of what constituted freedom of navigation.

"While the US insists they have the right to send warships to the disputed waters in the South China Sea, Beijing has always insisted that freedom of navigation should not cover military ships," he said.65

A February 22, 2018, press report states the following:

Hundreds of government officials, experts and scholars from all over the world conducted in-depth discussions of various security threats under the new international security situation at the 54th Munich Security Conference (MSC) from Feb. 16 to 18, 2018.

Experts from the Chinese delegation at the three-day event were interviewed by reporters on hot topics such as the South China Sea issue and they refuted some countries' misinterpretation of the relevant international law.

The conference included a panel discussion on the South China Sea issue, which China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries have been committed to properly solving since the signing of the draft South China Sea code of conduct.

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo, director of the Security Cooperation Center of the International Military Cooperation Office of the Chinese Ministry of National Defense, explained how some countries' have misinterpreted the international law.

"First of all, we must abide by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)," Zhou said. "But the problem now is that some countries unilaterally and wrongly interpreted the 'freedom of navigation' of the UNCLOS as the 'freedom of military operations', which is not the principle set by the UNCLOS," Zhou noted.66

A June 27, 2018, opinion piece in a British newspaper by China's ambassador to the UK stated that

freedom of navigation is not an absolute freedom to sail at will. The US Freedom of Navigation Program should not be confused with freedom of navigation that is universally recognised under international law. The former is an excuse to throw America's weight about wherever it wants. It is a distortion and a downright abuse of international law into the "freedom to run amok".

Second, is there any problem with freedom of navigation in the South China Sea? The reality is that more than 100,000 merchant ships pass through these waters every year and none has ever run into any difficulty with freedom of navigation....

The South China Sea is calm and the region is in harmony. The so-called "safeguarding freedom of navigation" issue is a bogus argument. The reason for hyping it up could be either an excuse to get gunboats into the region to make trouble, or a premeditated intervention in the affairs of the South China Sea, instigation of discord among the parties involved and impairment of regional stability….

China respects and supports freedom of navigation in the South China Sea according to international law. But freedom of navigation is not the freedom to run amok. For those from outside the region who are flexing their muscles in the South China Sea, the advice is this: if you really care about freedom of navigation, respect the efforts of China and Asean countries to safeguard peace and stability, stop showing off your naval ships and aircraft to "militarise" the region, and let the South China Sea be a sea of peace.67

A September 20, 2018, press report stated the following:

Chinese Ambassador to Britain Liu Xiaoming on Wednesday [September 19] said that the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea has never been a problem, warning that no one should underestimate China's determination to uphold peace and stability in the region….

Liu stressed that countries in the region have the confidence, capability and wisdom to deal with the South China Sea issue properly and achieve enduring stability, development and prosperity.

"Yet to everyone's confusion, some big countries outside the region did not seem to appreciate the peace and tranquility in the South China Sea," he said. "They sent warships and aircraft all the way to the South China Sea to create trouble."

The senior diplomat said that under the excuse of so-called "freedom of navigation," these countries ignored the vast sea lane and chose to sail into the adjacent waters of China's islands and reefs to show off their military might.

"This was a serious infringement" of China's sovereignty, he said. "It threatened China's security and put regional peace and stability in jeopardy."

Liu stressed that China has all along respected and upheld the freedom of navigation and over-flight in the South China Sea in accordance with international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

"Freedom of navigation is not a license to do whatever one wishes," he said, noting that freedom of navigation is not freedom to invade other countries' territorial waters and infringe upon other countries' sovereignty.

"Such 'freedom' must be stopped," Liu noted. "Otherwise the South China Sea will never be tranquil."68

In contrast to China's narrow definition, the U.S./Western definition of freedom of navigation is much broader, encompassing operations of various types by both commercial and military ships and aircraft in international waters and airspace. As discussed earlier in this report, an alternative term for referring to the U.S./Western definition of freedom of navigation is freedom of the seas, meaning "all of the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea and airspace, including for military ships and aircraft, guaranteed to all nations under international law."69 When Chinese officials state that China supports freedom of navigation, China is referring to its own narrow definition of the term, and is likely not expressing agreement with or support for the U.S./Western definition of the term.70

Preference for Treating Territorial Disputes on Bilateral Basis

China prefers to discuss maritime territorial disputes with other regional parties to the disputes on a bilateral rather than multilateral basis. Some observers believe China prefers bilateral talks because China is much larger than any other country in the region, giving China a potential upper hand in any bilateral meeting. China generally has resisted multilateral approaches to resolving maritime territorial disputes, stating that such approaches would internationalize the disputes, although the disputes are by definition international even when addressed on a bilateral basis. (China's participation with the ASEAN states in the 2002 declaration of conduct DOC and in negotiations with the ASEAN states on the follow-on binding code of conduct (COC) [see Appendix C] represents a departure from this general preference.) Some observers believe China is pursuing a policy of putting off a negotiated resolution of maritime territorial disputes so as to give itself time to implement the salami-slicing strategy.71

As mentioned earlier, the position of China and some other countries (i.e., a minority group among the world's nations) is that UNCLOS gives coastal states the right to regulate not only economic activities, but also foreign military activities, in their EEZs.

Depiction of United States as Outsider Seeking to "Stir Up Trouble"

Along with its above-discussed preference for treating territorial disputes on a bilateral rather than multilateral basis (see Appendix E for details), China resists and objects to U.S. involvement in maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS. Statements in China's state-controlled media sometimes depict the United States as an outsider or interloper whose actions (including freedom of navigation operations) are seeking to "stir up trouble" in an otherwise peaceful regional situation. Potential or actual Japanese involvement in the SCS is sometimes depicted in China's state-controlled media in similar terms. Depicting the United States in this manner can be viewed as consistent with goals of attempting to drive a wedge between the United States and its allies and partners in the region and of ensuring maximum leverage in bilateral (rather than multilateral) discussions with other countries in the region over maritime territorial disputes.

July 2018 Press Report Regarding Chinese Radio Warnings

A July 31, 2018, press report stated the following:

The Philippines has expressed concern to China over an increasing number of Chinese radio messages warning Philippine aircraft and ships to stay away from newly fortified islands and other territories in the South China Sea claimed by both countries, officials said Monday.

A Philippine government report showed that in the second half of last year alone, Philippine military aircraft received such Chinese radio warnings at least 46 times while patrolling near artificial islands built by China in the South China Sea's Spratly archipelago.

The Chinese radio messages were "meant to step up their tactics to our pilots conducting maritime air surveillance in the West Philippine Sea", the report said, using the Philippine name for the South China Sea.

A Philippine air force plane on patrol near the Chinese-held islands received a particularly offensive radio message in late January according to the Philippine government report.

It was warned by Chinese forces that it was "endangering the security of the Chinese reef. Leave immediately and keep off to avoid misunderstanding," the report said.

Shortly afterwards, the plane received a veiled threat: "Philippine military aircraft, I am warning you again, leave immediately or you will pay the possible consequences."

The Filipino pilot later "sighted two flare warning signals from the reef", said the report, which identified the Chinese-occupied island as Gaven Reef.

Philippine officials have raised their concern twice over the radio transmissions, including in a meeting with Chinese counterparts in Manila earlier this year that focused on the Asian countries' long-unresolved territorial disputes, according to two officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorised to discuss the issue publicly.

It is a new problem that emerged after China transformed seven disputed reefs into islands using dredged sand in the Spratlys…

The messages used to originate from Chinese coastguard ships in past years but US military officials suspect transmissions now are also being sent from the Beijing-held artificial islands, where far more powerful communications and surveillance equipment has been installed along with weapons such as surface-to-air missiles.

"Our ships and aircraft have observed an increase in radio queries that appear to originate from new land-based facilities in the South China Sea," Commander Clay Doss, public affairs officer of the US 7th Fleet, said by email in response to questions about the Chinese messages.

"These communications do not affect our operations," Doss said….

US Navy ships and aircraft communicate routinely with regional navies, including the Chinese navy.

"The vast majority of these communications are professional, and when that is not the case, those issues are addressed by appropriate diplomatic and military channels," Doss said.72

For discussion of some additional elements of China's approach to maritime disputes in the SCS and ECS, including China's nine-dash line in the SCS, see Appendix E.

U.S. Position on Maritime Disputes in SCS and ECS

Some Key Elements

The U.S. position on territorial and EEZ disputes in the Western Pacific (including those involving China)Assessments of China's Strengthening Position in SCS

Some observers assess that China's actions in the SCS have achieved for China a more dominant or more commanding position in the SCS. For example, U.S. Navy Admiral Philip Davidson, in responses to advance policy questions from the Senate Armed Services Committee for an April 17, 2018, hearing before the committee to consider nominations, including Davidson's nomination to become Commander, U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM), stated that "China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States." For additional assessments of China's strengthening position in the SCS, see Appendix F.

U.S. Position on Regarding Issues Relating to SCS and ECS

Some Key Elements

The U.S. position regarding issues relating to the SCS and ECS includes the following elements, among others:

- The United States supports the principle that disputes between countries should be resolved peacefully, without coercion, intimidation, threats, or the use of force, and in a manner consistent with international law.

- The United States supports the principle of freedom of the seas, meaning the rights, freedoms, and uses of the sea and airspace guaranteed to all nations in international law. The United States opposes claims that impinge on the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea that belong to all nations.

- The United States takes no position on competing claims to sovereignty over disputed land features in the ECS and SCS.

- Although the United States takes no position on competing claims to sovereignty over disputed land features in the ECS and SCS, the United States does have a position on how competing claims should be resolved: Territorial disputes should be resolved peacefully, without coercion, intimidation, threats, or the use of force, and in a manner consistent with international law.

- Claims of territorial waters and EEZs should be consistent with customary international law of the sea and must therefore, among other things, derive from land features. Claims in the SCS that are not derived from land features are fundamentally flawed.

- Parties should avoid taking provocative or unilateral actions that disrupt the status quo or jeopardize peace and security. The United States does not believe that large-scale

land reclamationisland-building with the intent to militarize outposts on disputed land features is consistent with the region's desire for peace and stability. - The United States, like most other countries, believes that coastal states under UNCLOS have the right to regulate economic activities in their EEZs, but do not have the right to regulate foreign military activities in their EEZs.

- U.S. military surveillance flights in international airspace above another country's EEZ are lawful under international law, and the United States plans to continue conducting these flights

as it has in the past.73.

- The Senkaku Islands are under the administration of Japan and unilateral attempts to change the status quo raise tensions and do nothing under international law to strengthen territorial claims.

For additional information regarding the U.S. position on the issue of operational rights of military ships in the EEZs of other countries, see Appendix F.

Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program

U.S. Navy ships challenge what the United States views as excessive maritime claims andmade by other countries, and otherwise carry out assertions of operational rights, as part of the U.S. Freedom of Navigation (FON)FON program for challenging maritime claims that the United States believes to be inconsistent with international law.74 The FON program began in 1979, involves diplomatic activities as well as operational assertions by U.S. Navy ships, and is global in scope, encompassing activities and operations directed not only at China, but at numerous other countries around the world, including U.S. allies and partner states.