“Waters of the United States” (WOTUS): Current Status of the 2015 Clean Water Rule

Changes from December 6, 2018 to December 12, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

"Waters of the United States" (WOTUS): Current Status of the 2015 Clean Water Rule

Contents

Summary

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the principal federal law governing pollution of the nation's surface waters. The statute protects "navigable waters," which it defines as "the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas." The scope of the term waters of the United States, or WOTUS, is not defined in the CWA. Thus, the Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have defined the term in regulations several times as part of their implementation of the act.

Two Supreme Court rulings (Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Rapanos v. United States), issued in 2001 and 2006 (respectively), interpreted the scope of the CWA more narrowly than EPA and the Corps had done previously in regulations and guidance. However, the rulings also created uncertainty about the intended scope of waters that are protected by the CWA. In 2014, the Corps and EPA proposed revisions to the existing 1980s regulations in light of these rulings. After reviewing over 1 million public comments and holding over 400 meetings with diverse stakeholders, the Corps and EPA issued a final rule in June 2015. The final rule—the Clean Water Rule—focused on clarifying the regulatory status of waters with ambiguous jurisdictional status following the Supreme Court rulings, including isolated waters and streams that flow only part of the year and nearby wetlands.

Since the Clean Water Rule was finalized in 2015, its implementation has been influenced both by the courts and administrative actions. Following issuance of the 2015 Clean Water Rule, industry groups, more than half the states, and several environmental groups filed lawsuits challenging the rule in multiple federal district and appeals courts. A federal appeals court ordered a nationwide stay of the 2015 Clean Water Rule in October 2015 and later ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear consolidated challenges to the rule. In January 2018, the Supreme Court unanimously held that federal district courts, rather than appellate courts, are the proper forum for filing challenges to the 2015 Clean Water Rule. As a result, the appeals court vacated its nationwide stay. Three district courts have issued preliminary injunctions on the 2015 Clean Water Rule effective in the states challenging the rule in those courts. Accordingly, the 2015 Clean Water Rule is currently enjoined in 28 states and in effect in 22 states. In states where the 2015 Clean Water Rule is enjoined, regulations promulgated by the Corps and EPA in 1986 and 1988, respectively, are in effect.

The Trump Administration has taken actions to delay implementation of the 2015 Clean Water Rule and rescind and replace it:

- In February 2018, the Corps and EPA published a rule that added an "applicability date" to the 2015 Clean Water Rule delaying implementation until February 2020. However, environmental groups and states filed lawsuits challenging the 2018 Applicability Date Rule, and in August 2018, a district court issued a nationwide injunction.

- The Trump Administration has also taken steps to rescind and replace the 2015 Clean Water Rule. In February 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13778 directing the Corps and EPA to review and rescind or revise the rule and to consider interpreting the term navigable waters in a manner consistent with Justice Scalia's opinion in Rapanos, which proposed a narrower test for determining WOTUS. In July 2017, the Corps and EPA published a proposed rule that would "initiate the first step in a comprehensive, two-step process intended to review and revise the definition of 'waters of the United States' consistent with the Executive Order." The proposed step-one rule would rescind the 2015 Clean Water Rule and re-codify the regulatory definition of WOTUS as it existed prior to the rule. In July 2018, the agencies published a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to solicit comment on additional considerations supporting the agencies' proposed repeal. A final step-one rule has not been issued.

According to a statement reportedly made by the acting EPA Administrator on October 2, 2018, the agency planned to release a proposal for the step-two replacement rule sometime "over the next 30 days or so."

On December 11, 2018, the Corps and EPA announced a proposed step-two rule that would revise the definition of WOTUS. In the 115th Congress, some Members have introduced free-standing legislation and provisions within appropriations bills that would either repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule, allow the Corps and EPA to withdraw the rule without regard to the Administrative Procedures Act, or amend the definition of navigable waters in the CWA. Two bills—H.R. 2 and H.R. 6147—have each passed the House and Senate in different forms. The House-passed versions of both bills would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule, while the Senate-passed versions of both bills do not include such provisions.

The conference report for H.R. 2, released on December 11, 2018, did not include a provision to repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule.Brief History of the 2015 Clean Water Rule

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the principal federal law governing pollution of the nation's surface waters.1 The CWA protects "navigable waters," defined in the statute as "waters of the United States, including the territorial seas."2 The scope of this term—waters of the United States, or WOTUS—determines which waters are federally regulated and has been the subject of debate for decades.3 The CWA does not define the term. Thus, in implementing the CWA, the Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have defined the term in regulations. For much of the past three decades, regulations promulgated by the Corps and EPA in 1986 and 1988, respectively, have been in effect.4

In 2001 and 2006, the Supreme Court issued rulings pivotal to the definition of WOTUS—Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Rapanos v. United States, respectively.5 Both rulings interpreted the scope of the CWA more narrowly than the Corps and EPA had done previously in regulations and guidance, but they created uncertainty about the intended scope of waters that are protected by the CWA. The Court's decision in Rapanos, split 4-1-4, yielded three different opinions. The four-Justice plurality decision, written by Justice Scalia, states that the dredge and fill provisions in the CWA apply only to wetlands connected to relatively permanent bodies of water (streams, rivers, lakes) by a continuous surface connection. Justice Kennedy, writing alone, demanded a "significant nexus" between a wetland and a traditional navigable water, using a case-by-case test that considers ecological connection. Justice Stevens, for the four dissenters, would have upheld the existing reach of Corps/EPA regulations.

In response to the rulings, the agencies developed guidance in 20036 and 20087 to help clarify how EPA regions and Corps districts should implement the Court's decisions. This guidance identified categories of waters that remained jurisdictional or not jurisdictional and required a case-specific analysis to determine whether jurisdiction applies. The guidance did not resolve all interpretive questions, and diverse stakeholders requested a formal rulemaking to revise the existing rules.8

Accordingly, the Corps and EPA proposed a rule in April 2014 defining the scope of waters protected under the CWA.9 On June 29, 2015, the Corps and EPA finalized the rule—known as the Clean Water Rule or WOTUS rule.10 It reflects over 1 million public comments on the 2014 proposed rule as well as input provided through public outreach efforts that included over 400 meetings with diverse stakeholders.11

Brief Overview of the 2015 Clean Water Rule

The 2015 Clean Water Rule retained much of the structure of the agencies' prior definition of WOTUS. It focused on clarifying the regulatory status of waters with ambiguous jurisdictional status following the Supreme Court's rulings, including isolated waters and streams that flow only part of the year and nearby wetlands. As explained in the 2015 Clean Water Rule's preamble, the Corps and EPA used Justice Kennedy's "significant nexus" standard in developing the rule as well as the plurality opinion (written by Justice Scalia) in establishing boundaries on the scope of jurisdiction.

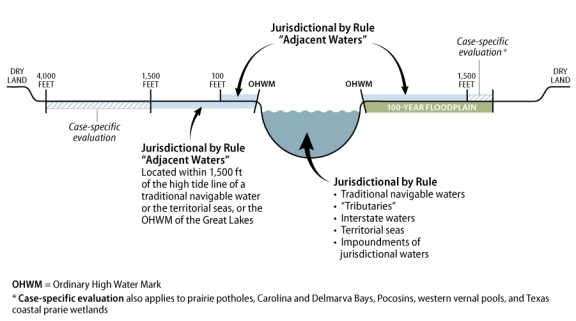

The 2015 Clean Water Rule identified categories of waters that are and are not jurisdictional as well as waters that require a case-specific evaluation (see Figure 1). Broad categories under the final rule include the following:

- Jurisdictional by rule in all cases. Traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, the territorial seas, and impoundments of these waters are jurisdictional by rule. All of these waters were also jurisdictional under pre-2015 rules.

- Jurisdictional by rule, as defined. Two additional categories—tributaries and adjacent waters—are jurisdictional by rule if they meet definitions established in the 2015 Clean Water Rule. According to the rule's preamble, the definitions ensure that the rule covers waters that meet the significant nexus standard.12 Tributaries, under pre-2015 rules, were jurisdictional by rule without qualification but lacked a regulatory definition. The 2015 Clean Water Rule newly defined tributaries. Tributaries that meet the new definition are jurisdictional by rule.13

- Similarly, "adjacent waters"—including wetlands, ponds, lakes, oxbows, impoundments, and similar waters that are adjacent to traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, the territorial seas, jurisdictional tributaries, or impoundments of these waters—are jurisdictional by the 2015 Clean Water Rule if they meet the rule's established definition. Under the 2015 Clean Water Rule, adjacent means "bordering, contiguous, or neighboring" one of the aforementioned waters. The rule established a definition of neighboring that set new limits for the purposes of determining adjacency. Neighboring is defined to include waters (1) located within 100 feet of the ordinary high water mark (OHWM)14 of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, the territorial seas, jurisdictional tributary, or impoundment of these waters; (2) located in the 100-year floodplain and within 1,500 feet of the OHWM of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, the territorial seas, jurisdictional tributary, or impoundment of these waters; or (3) located within 1,500 feet of the high tide line of a traditional navigable water or the territorial seas and waters located within 1,500 feet of the OHWM of the Great Lakes. Under pre-2015 rules, adjacent was defined to mean "bordering, contiguous, or neighboring" and did not include specific limits on "neighboring."

- Waters requiring a case-specific evaluation. Some types of waters—but fewer than under practices used prior to the 2015 Clean Water Rule—would remain subject to a case-specific evaluation of whether or not they meet the standards for federal jurisdiction. This case-specific evaluation examines whether the water has a significant nexus to traditional navigable waters, interstate waters or wetlands, or the territorial seas. Similarly situated waters (i.e., prairie potholes, Carolina bays and Delmarva bays, pocosins, western vernal pools, and Texas coastal prairie wetlands) are combined for the purposes of a significant nexus analysis.15 In addition, the 2015 Clean Water Rule provides that two other categories of waters are subject to case-specific significant nexus analysis: (1) waters within the 100-year floodplain of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, or the territorial seas; and (2) waters within 4,000 feet of the high tide line or the OHWM of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, the territorial seas, impoundments, or jurisdictional tributary.

- Exclusions. Certain waters would be excluded from CWA jurisdiction. Some were restated exclusions under pre-2015 rules (e.g., prior converted cropland). Some have been excluded by practice and would be expressly excluded by rule for the first time (e.g., groundwater and some ditches). Some were new in the final rule (e.g., stormwater management systems). The 2015 Clean Water Rule did not affect existing statutory exclusions—that is, exemptions for existing "normal farming, silviculture, and ranching activities" and for maintenance of drainage ditches (CWA §404(f))16 as well as for agricultural stormwater discharges and irrigation return flows (CWA §402(l) and CWA §502(14)).17

Issues and Controversy

Much of the controversy since the Supreme Court's rulings has centered on instances that have required CWA permit applicants to seek a case-specific analysis to determine if CWA jurisdiction applies to their activity. The Corps and EPA's stated intention in promulgating the Clean Water Rule was to clarify questions of CWA jurisdiction in view of the rulings while also reflecting their scientific and technical expertise.18 Specifically, they sought to articulate categories of waters that are and are not protected by the CWA, thus limiting the water types that require case-specific analysis.

Industries that are the primary applicants for CWA permits and agriculture groups raised concerns over how broadly the 2014 proposed rule would be interpreted. They contended that the proposed definitions were ambiguous and would enable agencies to assert broader CWA jurisdiction than is consistent with law and science. The final 2015 Clean Water Rule added and defined key terms, such as tributary and significant nexus, and modified the proposal in an effort to improve clarity, but the concerns remained.

Some local governments that own and maintain public infrastructure also criticized the 2014 proposed rule. They argued that it could increase the number of locally owned ditches under federal jurisdiction because it would define some ditches as WOTUS under certain conditions. Corps and EPA officials asserted that the proposed exclusion of most ditches would decrease federal jurisdiction, but the issue remained controversial. The final 2015 Clean Water Rule excluded most ditches and expressly excluded stormwater management systems and structures from jurisdiction.

Some states supported a rule to clarify the scope of CWA jurisdiction,19 but there was no consensus on the 2014 proposed rule or the final 2015 Clean Water Rule. Many states asserted that the changes would too broadly expand federal jurisdiction, some believed that the agencies did not adequately consult with states, and some were largely supportive.20

Environmental groups generally supported the agencies' efforts to protect waters and reduce uncertainty. Still, some argued that the scope of the 2014 proposed rule should be further expanded—for example, by designating additional categories of waters and wetlands (e.g., prairie potholes) as categorically jurisdictional. The final 2015 Clean Water Rule did not do so. Instead, such waters would require case-specific analysis to determine if jurisdiction applies.

Corps and EPA officials under the Obama Administration defended the 2014 proposed rule but acknowledged that it raised questions they believed the final 2015 Clean Water Rule clarified. In their view, the 2015 Clean Water Rule did not protect any new types of waters that were not protected historically, did not exceed the CWA's authority, and would not enlarge jurisdiction beyond what is consistent with the Supreme Court's rulings as well as scientific understanding of significant connections between small and ephemeral streams and downstream waters.21 The agencies asserted that they had addressed criticisms of the 2014 proposed rule by, for example, defining tributaries more clearly, setting maximum distances from jurisdictional waters for the purposes of defining neighboring waters, and modifying the definition of WOTUS to make it clear that the rule preserves agricultural exclusions and exemptions.22

Issuance of the final 2015 Clean Water Rule did not diminish concerns amongst stakeholders. Many groups contended that the rule did not provide needed clarity, that its expansive definitions made it difficult to identify any waters that would fall outside the boundary distances established in the rule, and that the threshold for determining "significant nexus" was set so low that virtually any water could be found to be jurisdictional.23 The 2015 Clean Water Rule would impose costs, critics said, but have little or no environmental benefit. Environmental groups were supportive but also faulted parts of the final rule. Some environmental groups believed the rule reduced the jurisdictional reach of the CWA and rolled back protections for certain waters, including minor tributaries and some ephemeral aquatic habitats.24

Current Status of the 2015 Clean Water Rule

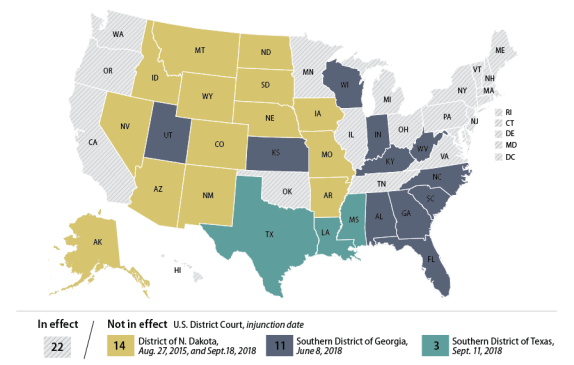

Currently, the 2015 Clean Water Rule is in effect in 22 states and enjoined in 28 states (see Figure 2). In states where the 2015 Clean Water Rule is enjoined, regulations promulgated by the Corps and EPA in 1986 and 1988, respectively, are in effect. Since the 2015 Clean Water Rule was finalized, its implementation has been influenced both by the courts and administrative actions.

|

Figure 2. Status of the 2015 Clean Water Rule as of |

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Court Actions

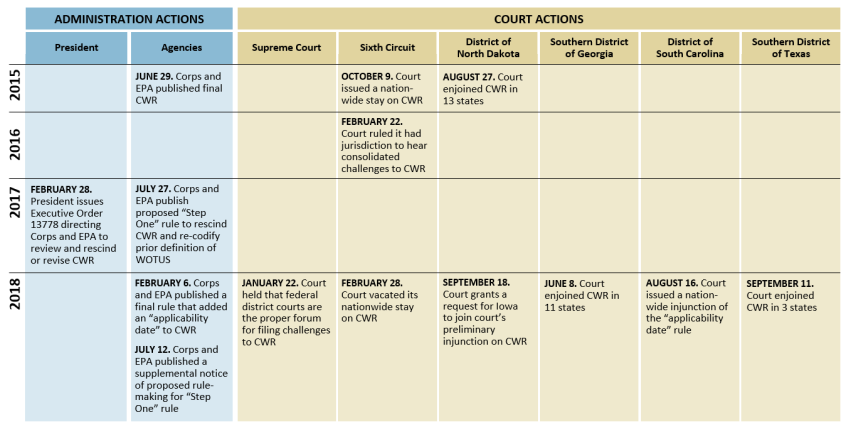

Following issuance of the 2015 Clean Water Rule, industry groups, more than half the states, and several environmental groups filed lawsuits challenging the rule in multiple federal district and appeals courts. By the time the 2015 Clean Water Rule entered into effect (August 28, 2015), a district court had already prevented its enforcement in 13 states. Specifically, on August 27, 2015, the U.S. District Court for the District of North Dakota issued a preliminary injunction on the 2015 Clean Water Rule in the 13 states challenging the rule in that court.25 In October 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ordered a nationwide stay of the 2015 Clean Water Rule and later ruled (in February 2016) that it had jurisdiction to hear consolidated challenges to the rule.26 However, in January 2018, the Supreme Court unanimously held that federal district courts, rather than appellate courts, are the proper forum for filing challenges to the 2015 Clean Water Rule.27 Accordingly, on February 28, 2018, the appeals court vacated its nationwide stay.28

On November 22, 2017, the Corps and EPA proposed to add an "applicability date" to the 2015 Clean Water Rule.29 The agencies finalized this rule on February 6, 2018, effectively delaying the implementation of the 2015 Clean Water Rule until February 6, 2020.30 According to the preamble of the 2018 Applicability Date Rule, the agencies' intention in adding an applicability date to the 2015 Clean Water Rule was to maintain the legal status quo and provide clarity and certainty for regulated entities, states, tribes, agency staff, and the public regarding the definition of waters of the United States while the agencies work on revising the 2015 Clean Water Rule.

Environmental groups and states immediately filed lawsuits challenging the 2018 Applicability Date Rule, asserting that it violated the Administrative Procedures Act. On August 16, 2018, the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina issued a nationwide injunction of the rule.31 As a result, the 2015 Clean Water Rule went into effect in the states where injunctions had not been issued. During the period between when the 2018 Applicability Date Rule was finalized and the district court issued a nationwide injunction of that rule, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Georgia enjoined the 2015 Clean Water Rule in 11 states.32 Since that time, two additional court actions have enjoined the 2015 Clean Water Rule in four additional states. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas enjoined the 2015 Clean Water Rule in three states on September 11, 2018. On September 18, 2018, the U.S. District Court for the District of North Dakota granted a request from the Governor of Iowa to clarify that the preliminary injunction applied to Iowa.33 Accordingly, the 2015 Clean Water Rule is currently in effect in 22 states and enjoined in 28 states. (See Figure 3 for a timeline of actions.)

|

Figure 3. Timeline of Selected Administrative and Court Actions Related to the Status of the 2015 Clean Water Rule (CWR) |

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Administrative Actions

The Administration has also taken steps to rescind and revise the 2015 Clean Water Rule. On February 28, 2017, President Trump issued an executive order directing the Corps and EPA to review and rescind or revise the rule and to consider interpreting the term navigable waters as defined in the CWA in a manner consistent with Justice Scalia's opinion in Rapanos.34 On July 27, 2017, the agencies proposed a rule that would "initiate the first step in a comprehensive, two-step process intended to review and revise the definition of 'waters of the United States' consistent with the Executive Order."35 The first step proposes to rescind the 2015 Clean Water Rule and re-codify the regulatory definition of WOTUS as it existed prior to the rule. On July 12, 2018, the Corps and EPA published a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to clarify, supplement, and seek additional comment on the agencies' proposed repeal.36 The public comment period closed on August 13, 2018. The agencies have not yet issued a final step-one rule.

On October 2, 2018, the acting EPA Administrator reportedly said he expected the agency to release a proposal for the step-two replacement rule sometime "over the next 30 days or so."37

Actions in the 115th Congress

Considering the numerous court rulings, ongoing legal challenges, and issues that Administrations have faced in defining the scope of WOTUS, some stakeholders have urged Congress to define WOTUS through amendments to the CWA. In the 115th Congress, Members of Congress have shown continued interest in the 2015 Clean Water Rule and the scope of WOTUS. Some Members have introduced the following free-standing legislation and provisions within appropriations bills that would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule, allow the Corps and EPA to withdraw the rule without regard to the Administrative Procedures Act, or amend the CWA to add a narrower definition of navigable waters.

- H.R. 1105 would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule.

- H.R. 1261 would nullify the 2015 Clean Water Rule and amend the CWA by changing the definition of navigable waters. The language, as proposed, would narrow the scope of waters subject to CWA jurisdiction.

- H.R. 7194 would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule and amend the CWA by changing the definition of navigable waters. The language, as proposed, would narrow the scope of waters subject to CWA jurisdiction. H.Res. 152 and S.Res. 12 would express the sense of the House and Senate, respectively, that the 2015 Clean Water Rule should be withdrawn or vacated.

- H.R. 2 (the farm bill)

includesincluded an amendment (H.Amdt. 633) in the House-passed version that would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule. However, the Senate-passed versiondoesdid not include that provision.Members of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees held a conference in September 2018 to reconcile the different versions of H.R. 2.The conference report—as released on December 11, 2018, and agreed to in the Senate—did not contain a provision to repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule.

- H.R. 6147—the Interior, Environment, Financial Services and General Government, Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Transportation, Housing and Urban Development Appropriations Act of 2019—includes a provision in the House-passed version that would repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule. However, the Senate-passed version does not include that provision. On September 6, 2018, the Senate agreed to the House's request for a conference to reconcile differences on H.R. 6147.

- The House-passed version of H.R. 5895—the Energy and Water, Legislative Branch, and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act, 2019—included a provision that would have repealed the 2015 Clean Water Rule. However the Senate-passed version and enacted public law (P.L. 115-244) did not include that provision.

- Two House-passed appropriations bills (H.R. 3219, Make America Secure Appropriations Act, 2018, and H.R. 3354, Interior and Environment, Agriculture and Rural Development, Commerce, Justice, Science, Financial Services and General Government, Homeland Security, Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, State and Foreign Operations, Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, Defense, Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, Legislative Branch, and Energy and Water Development Appropriations Act, 2018) contain provisions that would have authorized withdrawal of the 2015 Clean Water Rule "without regard to any provision of statute or regulation that established a requirement for such withdrawal" (e.g., the Administrative Procedures Act).

Conclusion

For several decades, Administrations have struggled to interpret the term navigable waters for the purpose of implementing various requirements of the CWA, and courts have been asked repeatedly to weigh in on those interpretations as manifest in regulations and policy. Stakeholders have asked the various Administrations and the courts to resolve issues involving scope, clarity, consistency, and predictability. Some stakeholders assert that the scope of waters under federal jurisdiction is overly broad, infringing on the rights of property owners, farmers, and others. Other stakeholders argue that the scope of federally protected waters is too narrow, leaving some hydrologically connected waters and aquatic habitats unprotected.

The regulations the Corps, EPA, and states are currently using to determine which waters are protected under the CWA vary across the United States. The jurisdictional scope as laid out in the 2015 Clean Water Rule is in effect in 22 states, while the jurisdictional scope laid out in regulations from the late 1980s is in effect in 28 states. Actions from the courts, the Administration, and Congress all have the potential to continue to alter the scope of federal jurisdiction under the CWA. Some observers argue that the term navigable waters, defined under the act as WOTUS, is too vague and should be addressed by Congress or the courts. Others argue that the Corps and EPA, with their specific knowledge and expertise, are in the best position to determine the scope of the term.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

33 U.S.C. §1251 et seq. |

| 2. |

CWA §502(7); 33 U.S.C. §1362(7). |

| 3. |

For a more in-depth discussion of the federal regulations, legislation, agency guidance, and case law that have shaped the meaning of waters of the United States over time, see CRS Report R44585, Evolution of the Meaning of "Waters of the United States" in the Clean Water Act, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 4. |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, "Final Rule for Regulatory Programs of the Corps of Engineers," 51 Federal Register 41206, November 13, 1986; EPA, "Clean Water Act Section 404 Program Definitions and Permit Exemptions; Section 404 State Program Regulations," 53 Federal Register 20764, June 6, 1988. |

| 5. |

531 U.S. 159 (2001) and 547 U.S. 715 (2006). |

| 6. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Appendix A, Joint Memorandum," 68 Federal Register 1995, January 15, 2003. |

| 7. |

Benjamin H. Grumbles, Assistant Administrator for Water, EPA, and John Paul Woodley Jr., Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works), Department of the Army, Clean Water Act Jurisdiction Following the U.S. Supreme Court's Decision in Rapanos v. United States & Carabell v. United States, memorandum, December 2, 2008. |

| 8. |

See EPA Web Archive at https://archive.epa.gov/epa/cleanwaterrule/what-clean-water-rule-does.html, which includes a list of stakeholders requesting a rulemaking (https://archive.epa.gov/epa/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/wus_request_rulemaking.pdf). |

| 9. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Definition of 'Waters of the United States' Under the Clean Water Act," 79 Federal Register 22188, April 21, 2014. |

| 10. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Clean Water Rule: Definition of 'Waters of the United States'; Final Rule," 80 Federal Register 37054, June 29, 2015 (hereinafter "2015 Clean Water Rule"). |

| 11. |

2015 Clean Water Rule (80 Federal Register 37057). |

| 12. |

2015 Clean Water Rule (80 Federal Register 37058). |

| 13. |

Under the 2015 Clean Water Rule, tributaries (including ephemeral and intermittent streams) are jurisdictional by rule if they have certain features that are indicators of flow (e.g., a bed and bank and an ordinary high water mark)—and contribute flow directly or indirectly to a traditional navigable water, an interstate water, or the territorial seas. |

| 14. |

OHWM is defined in Corps and EPA regulations as "that line on the shore established by the fluctuations of water and indicated by physical characteristics such as a clear, natural line impressed on the bank, shelving, changes in the character of soil, destruction of terrestrial vegetation, the presence of litter and debris, or other appropriate means that consider the characteristics of the surrounding areas." |

| 15. |

In the 2015 Clean Water Rule (80 Federal Register 37056), EPA and the Corps note Justice Kennedy concluded that wetlands possess the requisite significant nexus if the wetlands "either alone or in combination with similarly situated [wet]lands in the region, significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of other covered waters more readily understood as 'navigable.'" 547 U.S. at 780. |

| 16. |

33 U.S.C. §1344(f). |

| 17. |

33 U.S.C. §1342(l) and 33 U.S.C. §1362(14). |

| 18. |

2015 Clean Water Rule (80 Federal Register 37054). |

| 19. |

See EPA Web Archive at https://archive.epa.gov/epa/cleanwaterrule/what-clean-water-rule-does.html, which includes a list of stakeholders requesting a rulemaking (https://archive.epa.gov/epa/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/wus_request_rulemaking.pdf). |

| 20. |

EPA, Clean Water Rule Response to Comments—Topic 1: General Comments, pp. 90-133, https://www.epa.gov/cwa-404/response-comments-clean-water-rule-definition-waters-united-states. |

| 21. |

EPA published the following report, which according to the Clean Water Rule preamble (80 Federal Register 37057) provides much of the technical basis for the rule: EPA, Connectivity of Streams and Wetlands to Downstream Waters: A Review and Synthesis of the Scientific Evidence, EPA/600/R-14/475F, 2015. |

| 22. |

2015 Clean Water Rule (80 Federal Register 37055, 37079, 37082). |

| 23. |

See testimony of Tom Buchanan, American Farm Bureau Federation, in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Subcommittee on Superfund, Waste Management, and Regulatory Oversight, American Small Businesses' Perspectives on Environmental Protection Agency Regulatory Actions, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., April 12, 2016, S.Hrg.114-352. See U.S. Chamber of Commerce, "U.S. Chamber Statement on EPA's Final Clean Water Rule," press release, May 27, 2015, https://www.uschamber.com/press-release/us-chamber-statement-epa-s-final-clean-water-rule. Also see Opening Brief of State Petitioners and Opening Brief for the Business and Municipal Petitioners, Murray Energy Corp. v. United States DOD, No. 15-3751, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 9987 (6th Cir. Apr. 21, 2016). |

| 24. |

See Waterkeeper Alliance and Center for Biological Diversity, "EPA and Army Corps Issue Weak Clean Water Rule," press release, May 27, 2015, https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/press_releases/2015/clean-water-rule_05-27-2015.html. Also see Opening Brief of Petitioners Waterkeeper Alliance et al., Murray Energy Corp. v. United States DOD, No. 15-3751, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 9987 (6th Cir. Apr. 21, 2016). |

| 25. |

North Dakota v. United States EPA, 127 F. Supp. 3d 1047 (D.N.D. 2015). |

| 26. |

Ohio v. United States Army Corps of Eng'rs (In re EPA & DOD Final Rule), 803 F.3d 804 (6th Cir. 2015); Murray Energy Corp. v. United States DOD (In re United States DOD), 817 F.3d 261 (6th Cir. 2016). |

| 27. | |

| 28. | |

| 29. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Definition of 'Waters of the United States'—Addition of an Applicability Date to 2015 Clean Water Rule," 82 Federal Register 55542, November 22, 2017. |

| 30. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Definition of 'Waters of the United States'—Addition of an Applicability Date to 2015 Clean Water Rule," 83 Federal Register 5200, February 6, 2018. |

| 31. |

S.C. Coastal Conservation League v. Pruitt, 318 F. Supp. 3d 959 (D.S.C. 2018). |

| 32. |

Georgia v. Pruitt, No. 2:15-cv-79, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 97223 (S.D. Ga. June 8, 2018). |

| 33. |

North Dakota v. United States EPA, No. 3:15-cv-59, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 180503 (D.N.D. Sep. 18, 2018). |

| 34. |

Executive Order 13778, "Restoring the Rule of Law, Federalism, and Economic Growth by Reviewing the 'Waters of the United States' Rule," 82 Federal Register 12497, March 3, 2017. Note the Federal Register notice indicates that the executive order was issued on February 28, 2017. |

| 35. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Definition of 'Waters of the United States'—Recodification of Pre-Existing Rules," 82 Federal Register 34899, July 27, 2017. |

| 36. |

Army Corps of Engineers and EPA, "Definition of 'Waters of the United States'—Recodification of Preexisting Rule," 83 Federal Register 32227, July 12, 2018. |

| 37. |

|