Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Changes from November 27, 2018 to March 16, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to

March 16, 2021

Investigational Drugs

Agata Bodie

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates the safety and effectiveness of

Analyst in Health Policy

drugs and biological products under its authorities in the Federal Food, Drug and

Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) and Public Health Service Act (PHSA). In general, a manufacturer may not sel a drug or biologic in the United States until FDA has

reviewed and approved its marketing application (i.e., a new drug application [NDA] or

biologics license application [BLA]).

The primary route for an individual to obtain an investigational (i.e., unapproved) drug is to enroll in a clinical trial testing that new drug. However, an individual may be excluded from the clinical trial because its enrollment is limited to patients with particular characteristics (e.g., in a particular stage of a disease, with or without certain

other conditions, or in a specified age range), or because the trial has reached its target enrollment number. In certain circumstances, FDA may al ow an individual to obtain an investigational drug outside of a clinical trial through its expanded access procedures. Another option, the pathway created by the Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiel o, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bel ina Right to Try Act of 2017 (“Right to Try Act,” P.L. 115-176),

does not require FDA permission.

Right to Try Act

The Right to Try Act became federal law on May 30, 2018. Prior to its passageRight to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Contents

- Introduction

- Expanded Drug Access: FDA Authority and Policy Before the Right to Try Act

- What Is FDA's Standard Drug Approval Procedure?

- How Does FDA Regulate Individual IND Applications?

- Expanded Drug Access: Obstacles

- FDA-Related Issues

- Difficult Process to Request FDA Permission

- FDA as Gatekeeper

- Manufacturer-Related Issues

- Available Supply

- Liability

- Limited Staff and Facility Resources

- Data for Assessing Safety and Effectiveness

- Disclosure

- Federal Legislation Before the Right to Try Act

- The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2017 (S. 204, P.L. 115-176)

- Provisions in the Right to Try Act

- Discussion of Selected Provisions in the Right to Try Act

- Eligible Patients

- Informed Consent

- Data to FDA

- Financial Cost to Patient

- Liability Protections

- Concluding Comments

Summary

The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try (RTT) Act of 2017 became federal law on May 30, 2018. Over the preceding five years, 40 states had enacted related legislation. The goal of these legislative efforts was to al owwas to allow individuals with imminently life-threatening diseases

or conditions to seek access to investigational drugs directly from the manufacturer without the step of procuring permission from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)FDA. Another goal—held by the Goldwater Institute, which led the initiative toward state bills, bil s, and some of the legislative proponents—was focused more on the process: to eliminate government'’s role in an

individual’s choice.

The Right to Try Acts role in an individual's choice.

The RTT Act (P.L. 115-176) offers eligible individuals and their physicians a pathway other than FDA'’s expanded access procedures to acquiringobtain investigational drugs. It defines an eligible patient as one who (1) has been diagnosed with a life-threatening disease or condition, (2) has exhausted approved treatment options and is unable to participate in a clinical trial involving the eligible investigational drug (as certified by a physician who meets specified criteria),

and (3) has given written informed consent regarding the drug to the treating physician.

It defines an eligible investigational drug as an investigational drug (1) for which a Phase 1 clinical trial has been

completed, (2) that FDA has not approved or licensed for sale in the United States for any use, (3) that is the subject of a new drug application an NDA or BLA pending FDA decision or is the subject of an active investigational new drug application being studied for safety and effectiveness in a clinical trialapplication and is being studied in a clinical trial that is intended to support the drug’s effectiveness, and (4) for which the manufacturer has not discontinued active development or production and for which the FDA has not

placed on clinical hold.

The RTT

The Right to Try Act also has provisions that limit how the Secretary of Health and Human Services (through the FDA) can use data regarding clinical outcomes of patients who get these drugs through the RTT pathway; require drug sponsors (usually the manufacturers) to report annually to the Secretarythis pathway; require a drug’s sponsor or manufacturer to report annual y to FDA on use of the pathway; and require the SecretaryFDA to post certain

annual summaries. FinallyFinal y, the RTTRight to Try Act states that the sponsor or manufacturer has "“no liability"” for actions under the RTTthese provisions. The no-liability provision applies also to a prescriber, dispenser, or "other individual entity"“other

individual entity” unless there is "“reckless or willfulwil ful misconduct, gross negligence, or an intentional tort."

Before the RTT Act”

Before the Right to Try Act was enacted, observers discussed several obstacles to access to investigational drugs through FDA’s expanded access procedures. These included some that were FDA-related: the reportedly difficult process to request FDA permission, concern about FDA use of adverse event data, and the role of FDA as gatekeeper. Some related to why a manufacturer might decline to provide an investigational drug: limited available available supply, liability, limited limited staff and facility resources, and concerns about use of outcomes data. The RTTRight

to Try Act directly eliminates some of these concerns, addresses some others, and leaves others alone.

Future Congresses could look at the RTT Act's effect on FDA, drug manufacturers, and terminally ill patients. Will more patients get investigational drugs? Congress could look at whether the law sufficiently removed obstacles to access. And how will the changes affect FDA? Four former FDA commissioners warned that the bill would "create a dangerous precedent that would erode protections for vulnerable patients." The first clue may come from how the current commissioner interprets FDA's role in the implementation of the new law.

Introduction

The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try (RTT) Act of 2017 became federal law on May 30, 2018. Over the preceding five years, 40 states had enacted related legislation. The goal was to allow individuals with unaddressed.

Congressional Research Service

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Opponents of the law have expressed concern about the erosion of protections for patients who may be exposed to drugs that are unsafe or ineffective. For example, in taking FDA out of the equation, the Right to Try Act limits the agency’s ability to make suggestions to the protocols under which investigational drugs are provided,

potential y compromising patient safety.

Congressional Considerations

While the Right to Try Act aimed to remove certain perceived obstacles to obtaining investigational drugs,

unknowns remain regarding its impact on patients, drug manufacturers, and FDA. These unknowns include (1) whether more patients have received investigational drugs than prior to the law ’s enactment, (2) whether manufacturers are granting more requests for investigational drugs under the Right to Try Act pathway than previously under expanded access, and (3) FDA’s role in implementing certain Right to Try Act requirements when the purpose of the law was to remove FDA from the situation. Congress may consider whether the law has

had the effect its sponsors intended or whether legislative changes are necessary.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 20 Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 FDA Regulation of Investigational Drugs ........................................................................... 2 Expanded Access and Obstacles ........................................................................................ 4

FDA Requirements .................................................................................................... 4 Obstacles to Access.................................................................................................... 5

FDA-Related Issues .............................................................................................. 6

Manufacturer-Related Issues .................................................................................. 9

The Right to Try Act...................................................................................................... 10

Provisions in the Right to Try Act .............................................................................. 11

Discussion of Selected Provisions in the Right to Try Act .............................................. 12

Eligible Patients ................................................................................................. 12 Informed Consent............................................................................................... 13 Data to FDA ...................................................................................................... 13 Disclosure ......................................................................................................... 14

Financial Cost to Patient...................................................................................... 14 Liability Protections ........................................................................................... 15

Concluding Comments................................................................................................... 15

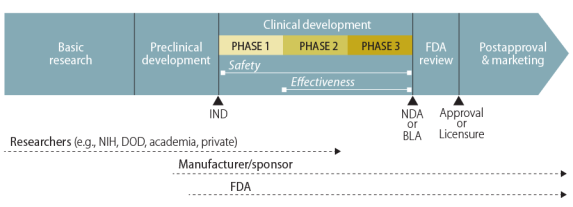

Figures Figure 1. Standard Drug Development Path......................................................................... 3

Tables

Table 1. Access to Investigational Drugs ............................................................................. 4

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 16

Congressional Research Service

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Introduction The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiel o, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bel ina Right to Try Act of 2017 (“Right to Try Act,” P.L. 115-176) became federal law on May 30, 2018. Prior to its

passage, 40 states had enacted related legislation. The law’s goal was to al ow individuals with imminently life-threatening diseases or conditions to seek access to investigational drugs without the step of procuring permission from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Another goal—held by the Goldwater Institute, which led the initiative toward state billsbil s, and some of the legislative legislative proponents—was focused more on the process: to eliminate government'’s role in an individual's choice.

individual’s choice.1

The effort to publicize the issue and press for a federal solution involved highlighting the poignant situations of individuals who sought access. For example, in March 2014, millionsmil ions of

of Americans heard about the plight of a seven-year-old boy with cancer. He was battling an infection following a bone marrow transplant that infection no antibiotic had been able to tame.1treat.2 His physicians thought an experimental antiviral drug might help. Because FDAdrug might help.

Because the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had not yet approved that experimental drug, it was not available in pharmacies. But FDA did have the authority to permit the use of an unapproved drug in certain circumstances—a process referred to as expanded accessaccess or compassionate use. For FDA to grant that permission, however, the manufacturer must have agreed to provide

the drug. The manufacturer, which was still stil testing the drug that the boy sought, declined.

Other stories often pointed

toward FDA as an obstacle.

During this time, certain groups—for example, the Goldwater Institute—encouraged Congress to act on right-to-try legislation (i.e., legislation that would al ow patients to access investigational drugs without FDA permission). The institute framed the issue as one of individual freedom and circulated model legislation.3 After 33 states4 enacted legislation reflecting the Goldwater Institute-provided model bil , in January 2017, some Members of Congress introduced a bil to try to address the issue. The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiel o, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew

Bel ina Right to Try Act of 2017—named for several individuals facing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease) or Duchenne muscular dystrophy—sought to remove what proponents saw as FDA obstacles to patient access. On May 30, 2018, President Trump signed

the bil into law (P.L. 115-176). This report discusses

1 Goldwater Institute, “President T rump Signs Right to T ry Act into Law,” May 30, 2018, https://goldwaterinstitute.org/article/president -trump-signs-right -to-try-act-into-law/. T he Goldwater Institute’s website describes itself as “a leading free-market public policy research and litigation organization that is dedicated to empowering all Americans to live freer, happier lives … the Institute focuses on advancing the principles of limited government, economic freedom, and individual liberty ” (Goldwater Institute, https://goldwaterinstitute.org/about/).

2 Steve Usdin, “Josh Hardy chronicles: How Chimerix, FDA grappled with providing compassionate access to Josh Hardy,” BioCentury, March 31, 2014, https://www.biocentury.com/biocentury/regulation/2014-03-31/how-chimerix-fda-grappled-providing-compassionate-access-josh-hardy; Kim Painter, “ Drug company changes course, gives drug to sick boy,” USA Today, March 12, 2014, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/03/11/chimerix-josh-hardy-drug/6308891/; and David Kroll, “ Josh Hardy Going Home After Getting Chimerix Anti-Viral Drug,” Forbes, July 17, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/07/17/josh-hardy-going-home-after-getting-chimerix-anti-viral-drug/.

3 Goldwater Institute, “Right to T ry Model Legislation,” https://goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/cms_page_media/2016/1/5/GoldwaterInstituteRighttoTryModel.pdf.

4 Starlee Coleman, “Ohio becomes 33rd state to adopt right to try law for terminally ill,” Goldwater Institute, January 5, 2017, https://goldwaterinstitute.org/article/ohio-33rd-state-to-adopt-right-to-try-law-terminally-ill/.

Congressional Research Service

1

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

how FDA regulates investigational drugs; FDA’s expanded access procedures and the perceived obstacles to individuals

accessing experimental drugs through this mechanism;

a summary of the provisions in the Right to Try Act and how they are meant to

addresstoward FDA as an obstacle. Until FDA approves a drug or licenses a biologic, the manufacturer cannot put it on the U.S. market.

During this time, Congress faced pressure to act, encouraged by the Goldwater Institute, which framed the issue as one of individual freedom—a right to try. The institute, which news accounts frequently refer to as a libertarian think tank,2 circulated model legislation.3 The bill's preface describes its scope:

A bill to authorize access to and use of experimental treatments for patients with an advanced illness; to establish conditions for use of experimental treatment; to prohibit sanctions of health care providers solely for recommending or providing experimental treatment; to clarify duties of a health insurer with regard to experimental treatment authorized under this act; to prohibit certain actions by state officials, employees, and agents; and to restrict certain causes of action arising from experimental treatment.

After 33 states4 enacted legislation reflecting the Goldwater Institute-provided model bill, in January 2017, legislators introduced a bill (S. 204) designed to address the issue. Their Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2017—named for several individuals facing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig's disease) or Duchenne muscular dystrophy—sought to remove what proponents saw as FDA obstacles to patient access.

On May 30, 2018, President Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-176).

This report discusses

- FDA's expanded access program, which many refer to as the compassionate use program, through which FDA allows manufacturers to provide to patients investigational drugs—drugs that have not completed clinical trials to test their safety and effectiveness;

- obstacles—perceived as the result of FDA or manufacturer decisions—to individuals' access to experimental drugs;

- a summary of the provisions in the Right to Try (RTT) Act and how they are meant to ease those obstacles;

a discussion ofthose obstacles; and selected provisions in theRTTRight to Try Act and what questions remain unresolved. FDA Regulation of Investigational Drugs The FDA regulates the safety and effectiveness of drugs and biological products (“biologics”) under its authorities in the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) and Public Health Service Act (PHSA).5 In general, a manufacturer may not sel a drug or biologicAct and what questions remain unresolved; and- comments about the broader implications of the RTT Act.

Expanded Drug Access: FDA Authority and Policy Before the Right to Try Act

What Is FDA's Standard Drug Approval Procedure?

In general, a manufacturer may not sell a drug or vaccine in the United States until FDA has reviewed and approved its marketing application (i.e., a new drug

application [NDA] or biologics license application [BLA]). That application for a new drug or biologic includesbiologic must include data from clinical trials as evidence of the product'’s safety and

effectiveness for its stated purpose(s).5

6

After laboratory and animal studies have identified a potential drug or vaccine, a sponsor, usually thebiologic, the sponsor of the clinical trial, usual y its manufacturer, may submit an investigational new drug (IND) application to FDA for permission to begin testing the drug in humans.7 An IND must include information about the proposed study design, chemistry and manufacturing of the drug, and the investigator’s qualifications, among other information.8 The investigator also must provide assurance that an

Institutional Review Board (IRB) wil provide initial and continuous review and approval of each of the studies in the clinical investigation to ensure that participants are aware of the drug’s investigative status and that any risk of harm wil be necessary, explained, and minimized.9 Sponsors of clinical trials also must comply with FDA regulations governing protection of human subjects (e.g., informed consent),10 adverse event reporting,11 and charging for investigational

new drugs,12 among other requirements.

FDA has 30 days to review an IND, after which a sponsor may begin clinical testing if the agency has not objected and imposed a clinical hold.13 In reviewing an IND, FDA’s primary objective is

to assure the safety and rights of human subjects, and with respect to Phase 2 and 3 trials

5 Whereas the FFDCA (§505) authorizes FDA to approve and regulate drugs, the Public Health Service Act (PHSA §351) authorizes FDA to license biological products (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, vaccines). Most FDA procedures regarding drugs also apply to the agency’s regulation of biological products. 6 FFDCA §505(b) [21 U.S.C. §355(b)], PHSA §351(a) [42 U.S.C. §262(a)], 21 C.F.R. §314.50, §601.2. For an overview of the general process of drug approval in t he United States, see CRS Report R41983, How FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. See, also, FDA, “ How Drugs are Developed and Approved,” http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/default.htm.

7 FFDCA §505(i) [21 U.S.C. §355(i)], PHSA §351(a)(3) [42 U.S.C. §262(a)(3)], 21 C.F.R. Part 312. 8 21 C.F.R. §312.23. 9 21 C.F.R. §312.23(a)(1)(iv) and 21 C.F.R. Part 56. 10 21 C.F.R. Part 50. 11 21 C.F.R. §312.32. 12 21 C.F.R. §312.8. 13 21 C.F.R. §312.20(c).

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 7 link to page 8

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

specifical y, to ensure that the quality of the scientific investigations and evaluations is adequate

to permit an evaluation of the drug’s safety and effectiveness.14

Once the IND application is approvedto FDA.6 With FDA permission, the sponsor may then start the first of three major phases

of clinical—human—trials. (Figure 1 illustrates the general path of a pharmaceutical product.)

Once the IND application is approved, researchers Researchers first test in a small smal number of human volunteers the safety they had previously demonstrated in animals. These trials, calledcal ed Phase I1 clinical trials, attempt "“to determine dosing, document how a drug is metabolized and excreted, and identify acute side effects."7”15 If a sponsor considers the product still stil worthy of investment based on the results of a Phase I1 trial, it

continues with Phase II2 and Phase III3 trials. Those trials look for evidence of the product'’s effectiveness—how well wel it works for individuals with the particular characteristic, condition, or disease of interest.16 Phase II2 is a first attempt at assessing effectiveness and its experience helps to plan the subsequent Phase III3 clinical trial, which the sponsor designs to be large enough to statistically

statistical y test for meaningful differences attributable to the drug.

Figure 1. Standard Drug Development Path |

|

Source: Created by CRS. Notes: The figure does not show the elements |

A manufacturer may distribute a drug or vaccine in the United States only if FDA has (1) approved its new drug application (NDA) or biologics license application (BLA) or (2) authorized its use in a clinical trial under an IND. Under standard procedures, individuals outside of the sponsor-run clinical trials do not have access to the investigational new drug. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), however, permits FDA in certain circumstances to allow access to an unapproved drug or to an approved drug for an unapproved use. One such mechanism is expanded access, commonly referred to as compassionate use, through individual or group INDs.

How Does FDA Regulate Individual IND Applications?

Key Expanded Access Source Documents FFDCA §561 (21 U.S.C. §360bbb). Expanded access to unapproved therapies and diagnostics.

|

The primary route for an individual to obtain an investigational drug is to enroll in a clinical trial testing that new drug.8 However, an individual may be excluded from the clinical trial because its enrollment is limited to patients with particular characteristics (e.g., in a particular stage of a disease, with or without certain other conditions, or in a specified age range), or because the trial has reached its target enrollment number.

Through FDA's expanded access procedure,9s expanded access procedure, a person, acting through a licensed physician, may request10request access to an investigational drug—through either a new IND or a revised protocol to an

existing IND—if11

- if19

a licensed physician determines (1) the patient has

"“no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy available"” the serious disease or condition; and (2)"“the probable risk to the person from the investigational drug scope of this report but is discussed in other CRS products. See, for example, CRS In Focus IF10745, Em ergency Use Authorization and FDA’s Related Authorities. 18 FDA, “Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for Industry, June 2016, updated October 2017, pp. 2 -3, https://www.fda.gov/media/85675/download. 19 FFDCA §561(b) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb(b)]. See, also, FDA, “Expanded Access: Information for Patients,” https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealt hFocus/ExpandedAccessCompassionateUse/ucm20041768.htm. In addition to the individual IND or protocol, regulations describe other categories of expanded use of investigational drugs: intermediate-size patient populations, with one IND or protocol that con solidates several individual access requests, and treatment IND or treatment protocol for “widespread treatment use” when a drug is farther along the clinical trial and marketing application process. See FFDCA §561(c) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb(c)]; and 21 C.F.R. §§312.305, 312.310, 312.315, and 312.320. Congressional Research Service 4 Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugsthe probable risk to the person from the investigational drugor investigational device is not greater than the probable risk from the disease orcondition"; - condition”;

the Secretary (FDA, by delegation of authority) determines (1)

"“that there is sufficient evidence of safety and effectiveness to support the use of the investigational drug"” for this person; and (2)"“that provision of the investigational drug ...willwil not interfere with the initiation, conduct, or completion of clinical investigations to support marketing approval"”; and the sponsor of the investigational drug, or clinical investigator, submits to FDA a; and "the sponsor, or clinical investigator, of the investigational drug ... submits" "to the Secretary aclinical protocol consistent with theprovisions of"requirements of FFDCA Section 505(i) and related regulations.

FDA makes most expanded access IND and protocol decisions on an individual-case basis.

Consistent with the IND process under which the expanded access mechanism fallsfal s, it considers the requesting physician as the investigator. The investigator must comply with informed consent and IRBand institutional review board (IRB) review of the expanded use.20 The sponsor of the IND The manufacturer must make required safety reports to FDA.21 FDA may permit a manufacturersponsor to charge a patient for the investigational drug, but "“only [for] the direct costs of making its investigational drug available"12 ”22 (i.e., not for development

costs or profit).

Expanded access could apply outside of the clinical trial arena in these situations:

(1) use in situations when a drug has been withdrawn for safety reasons, but there exists a patient population for whom the benefits of the withdrawn drug continue to outweigh the risks; (2) use of a similar, but unapproved drug (e.g., foreign-approved drug product) to provide treatment during a drug shortage of the approved drug; (3) use of an approved drug where availability is limited by a risk by a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for diagnostic, monitoring, or treatment purposes, by patients who cannot obtain the drug under the REMS; or (4) use for other reasons.13

23 Obstacles to Access The widespread use of expanded access is limited by an important factor: whether the manufacturer agrees to provide the drug, which—because it is not FDA-approved—cannot be obtained otherwise. FDA does not have the authority to compel a manufacturer to participate.

Expanded Drug Access: Obstacles

In addition, some manufacturers have expressed concern regarding how FDA would use adverse event data from expanded access when reviewing drug applications. Many highly publicized accounts of specific individuals'’ struggles with life-threatening conditions and efforts by activists influenced public debate over access. Another development was the model bill circulated in 2014 by the Goldwater Institute.14 Examples of public attitudes included news accounts of

specific individuals'’ struggles with life-threatening conditions.

Some found the process of asking FDA for a treatment IND too cumbersome. Others question FDA'questioned FDA’s right to act as a gatekeeper at all.15 Some point to manufacturers' refusal to provide their experimental drugs. Most

20 21 C.F.R. §312.305(c)(4). 21 21 C.F.R. §312.305(c)(5). 22 21 C.F.R. §312.8 and FDA, “Guidance for Industry: Charging for Investigational Drugs Under an IND—Questions and Answers,” Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, June 2016, https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm351264.pdf.

23 FDA, “Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for Industry, June 2016, updated October 2017, p. 3, https://www.fda.gov/media/85675/download.

Congressional Research Service

5

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

at al .24 Some pointed to manufacturers’ refusal to provide their experimental drugs.25 Most critics, therefore, see solutions as within the control of FDA or pharmaceutical companies. This critics, therefore, see solutions as within the control of FDA or pharmaceutical companies.

This section lays out key perceived obstacles and issues—both FDA- and manufacturer-related.

FDA-Related Issues

Difficult Process to Request FDA Permission

Have FDA's procedures discouraged patients and their physicians from seeking treatment INDs? For example: Does FDA ask for so much information that physicians or patients do not begin or complete the application? Does the FDA application process take too much time given the urgent need?

—with

respect to expanded access prior to the enactment of the Right to Try Act.

FDA-Related Issues

Difficult Process to Request FDA Permission

In February 2015, FDA issued draft guidance (finalized in June 2016 and updated in October 2017) on individual patient expanded access applications, acknowledging such difficulties.16 Itdifficulties with

requesting permission for access to investigational drugs from the agency.26 FDA developed a new form that a physician could use when requesting expanded access for an individual patient. It reduced the amount of information required from the physician by allowingal owing reference (with the sponsor'

sponsor’s permission) to the information the sponsor had already submitted to FDA in its IND.17 When a patient needs emergency treatment27

In October 2017, FDA modified its expanded access IRB review policy to al ow one IRB member to concur with the treatment use rather than the full IRB.28 This policy change was made pursuant to a statutory directive that FDA streamline IRB review of individual patient expanded access requests.29 A September 2019 report published by the Government Accountability Office (GAO)

found that the IRB update was helpful for physicians and patients, for example, by reducing the

amount of time for patients to obtain access to investigational drugs.30

In instances where a patient needs emergency treatment with the investigational product before a physician can submit a written request, FDA can authorize expanded access for an individual patient by phone or email, and the physician or sponsor must agree to submit an IND or protocol within 15 working days.18

Coincident with discussions preceding passage of the RTT

24 T he Abigail Alliance, formed by the father of a young woman with cancer who had unsuccessfully attempted to get an investigational drug, subsequently went to court, claimed “ as a fundamental aspect of constitutional due process, the right to choose to take medication of unknown benefit and risk that might potentially be lifesaving” (Linda Greenhouse, “Justices Won’t Hear Appeal on Drugs for T erminally Ill,” New York Times, January 15, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/15/washington/15appeal.html?_r=0). T he U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 2007 opinion found “that there is no Const itutional right to access to experimental drugs for terminally ill patients”; in 2008, the Supreme Court declined to consider an appeal (FDA, “Court Decisions, Fiscal Year 2008,” http://www.fda.gov/downloads/iceci/enforcementactions/enforcementstory/ucm129820.pdf). 25 Jonathan J. Darrow, Ameet Sarpatwari, Jerry Avorn, M.D., and Aaron S. Kesselheim, “Practical, Legal, and Ethical Issues in Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs,” New England Journal of Medicine, January 2015, vol. 372, pp. 279-286. 26 FDA, “Individual Patient Expanded Access Applications: Form FDA 3926,” Guidance for Industry, June 2016, Updated October 2017, p. 4, https://www.fda.gov/media/91160/download.

27 FDA estimated that it would take a physician about 45 minutes to complete the proposed new form rather than the 8 hours estimated for the original form (or 16 hours when the r equest was for emergency access) (80 FR 7318). FDA, “Guidance for Industry: Individual Patient Expanded Access Applications: Form FDA 3926.” 28 FDA, “Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new efforts to strengthen FDA’s expanded access program,” November 8, 2018, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-efforts-strengthen-fdas-expanded-access-program. FDA, “ Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for Industry, p. 6.

29 P.L. 115-52, §610(b). 30 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” GAO-19-630, September 2019, pp. 18-19, https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/701243.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

6

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

within 15 working days.31 In such emergency circumstances, treatment with the investigational

drug may begin prior to IRB approval, but the IRB must be notified within five working days.32

Coincident with discussions preceding passage of the Right to Try Act, FDA had commissioned

Act, FDA had commissioned an independent report on its expanded access program. Citing that report,1933 in November 2018, the commissioner then-FDA Commissioner Gottlieb announced several actions to improve its program.34 These includeincluded an enhanced webpage to help applicants navigate the application process and establishing an agency-wide Expanded Access Coordinating Committee. In July 2019, FDA launched the Oncology Center of Excel ence Project Facilitate, which provides a single point of

contact through which FDA oncology staff help physicians through the process of submitting an expanded access request for an individual patient with cancer.35 According to a 2019 GAO report, officials from one drug manufacturer indicated that Project Facilitate may help reduce the burden on oncologists seeking expanded access to investigational drugs for their patients. However, other officials from the same manufacturer “raised concerns about the potential for FDA to intentional y or unintentional y pressure companies to make their investigational drugs available

to patients, should FDA have increased involvement with drug manufacturers as part of the pilot

program.”36

Use of Adverse Event Data from Expanded Access

In October 2017, FDA updated its guidance to address how the agency reviews adverse event data in the expanded access context. In the guidance, FDA explains that reviewers are aware of the

context in which adverse event data are generated—for example, that patients who receive a drug through expanded access may have a more advanced stage of the disease than those enrolled in a clinical trial—and evaluate adverse events in that context. The guidance further states that “FDA is not aware of instances in which adverse event information from expanded access has prevented FDA from approving a drug.”37 However, FDA officials have indicated to GAO that “efficacy and

safety data from the expanded access program have been used to support drug approvals in several instances.”38 Further, expanded access use may al ow for the detection of rare adverse events or may contribute to information about use of the drug in certain populations that are not exposed to the drug in clinical trials.39 While some drug manufacturers have indicated that they

31 21 C.F.R. §312.310(d). FDA “For Physicians: How to Request Single Patient Expanded Access (“Compassionate Use”),” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/investigational-new-drug-ind-application/physicians-how-request-single-patient-expanded-access-compassionate-use.

32 FDA, “Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for Industry, p. 5.

33 FDA, “Expanded Access Program Report,” May 2018, https://www.fda.gov/media/119971/download. 34 FDA, “Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new efforts to strengthen FDA’s expanded access program,” November 8, 2018, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-efforts-strengthen-fdas-expanded-access-program.

35 FDA, “Project Facilitate,” https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-facilitate. GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” pp. 18-19. 36 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” p. 19. 37 FDA, “Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for Industry, p. 18.

38 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” p. 22. 39 FDA, “Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for T reatment Use—Questions and Answers,” Guidance for

Congressional Research Service

7

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

view FDA’s updated guidance as an improvement, others maintained that they stil had significant concerns about adverse event data from expanded access use negatively affecting

development of their investigational new drugs.40

FDA as Gatekeeper

FDA action is not the final obstacle to access, as the manufacturer stil needs to agree to provide

their product. Between FY2010 through FY2020, FDA received 16,380 expanded access requests

and granted 16,258 (99.3%) of them.41

Leading up to passage of the Right to Try Act, in August 2014, a USA Today editorial had cal ed

the FDA procedures that patients must follow for compassionate use access “bureaucratic absurdity,” “daunting,” and “fatal y flawed.” Echoing much of the criticism that FDA had received regarding the issue, it cal ed for one measure that would “cut out the FDA, which now has final say.”42 The solution the editorial proposed involved what proponents term “right to try” laws. By spring 2018, 40 states had passed right to try laws in the absence of federal legislation.43

The laws varied on the detail required in informed consent and liability establishing an agency-wide Expanded Access Coordinating Committee. Regarding the RTT Act's new pathway to investigational drug access, FDA has established a work group and set up a Right to Try webpage.20

FDA as Gatekeeper

In August 2014, a USA Today editorial called the FDA procedures that patients must follow for compassionate use access "bureaucratic absurdity," "daunting," and "fatally flawed." Echoing much of the criticism that FDA had received regarding the issue, it called for one measure that would "cut out the FDA, which now has final say."21 The solution the editorial proposed involved what proponents term "right-to-try" laws. By January 2018, 39 states had passed right to try laws in the absence of federal legislation.22 These laws were intended to allow a manufacturer to provide an investigational drug to a terminally ill patient if the case met certain conditions:

- the drug has completed Phase I testing and is in a continuing FDA-approved clinical trial;

- all FDA-approved treatments have been considered;

- a physician recommends the use of the investigational drug; and

- the patient provides written informed consent.

The state laws account for anticipated obstacles to the new arrangement. For example, they provide that insurers may, but are not required to, cover the investigational treatment, and that state medical boards and state officials may not punish a physician for recommending investigational treatment. The laws vary on the detail required in the informed consent and liability issues of the manufacturer and the patient'’s estate.2344 However, several experts had suggested that this state law approach is unlikely unlikely to directly increase patient access.2445 Before passage of the federal RTTRight to Try Act, analysts raised questions about how federal law (the FFDCA), which required FDA approval of such arrangements, might preempt this type of state law.25 With the federal RTT Act now in place46 After the enactment of the federal Right to Try Act, some legal analysts suggesthad predicted that the issue of federal preemption of state laws "will

laws would “likely be determined on a case-by-case basis."26 Second—and also relevant to the federal RTT Act—for a patient who follows FDA procedures, FDA action is not the final obstacle to access. During FY2010 through FY2017, FDA received 10,482 expanded access requests and granted 10,429 (99.5%) of them.27

Before the passage of the RTT Act, several bills were introduced at the federal level in the 113th, 114th, and 115th Congresses.28

Although the stated goal of these laws—allowing seriously ill people to try an experimental drug when other treatments have failed—may be understandable, provisions in the laws may be subject to legal,29 logistical, ethical, and medical obstacles.

Do these laws actually increase such access? Provisions in the federal and state right-to-try laws allow certain patients to obtain—without the FDA's permission—an investigational drug that has passed the Phase 1 (safety) clinical trial stage. A key obstacle to patients' obtaining investigational drugs nonetheless remains: FDA does not have "final say" because it cannot compel a manufacturer to provide the drug.

Manufacturer-Related Issues

Why would a manufacturer not give its experimental drug to every patient who requests it? The manufacturer faces a complex decision. Certainly profit plays a role: companies think about public relations problems and the opportunity costs of limited staff and facility resources, but companies must also consider the available supply of the drug, liability, safety, and whether adverse event or outcome data will affect FDA'”47

Industry, p. 18.

40 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” pp. 21-22. 41 Reports for 2010 through 2020 are at FDA, “Expanded Access INDs and Protocols,” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/ind-activity/expanded-access-inds-and-protocols.

42 T he Editorial Board, “FDA vs. right to try: Our view,” USA Today, August 17, 2014, http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2014/08/17/ebola-drugs-terminally-ill-right -to-try-editorials-debates/14206039/.

43 National Conference of State Legislatures, “‘Right to T ry’ Experimental Prescription Medicines State Laws and Legislation for 2014-2017,” March 7, 2018, http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-laws-and-legislation-related-to-biologic-medications-and-substitution-of-biosimilars.aspx#Right_to_Try. 44 For example: House Bill 14-1281, State of Colorado, Sixty-ninth General Assembly, http://www.leg.state.co.us/clics/clics2014a/csl.nsf/fsbillcont/CE8AAA4FAF92567487257C6F005C8D97?Open&file=1281_enr.pdf; House Bill No. 891, Enrolled, Louisiana, https://www.legis.la.gov/Legis/Vie wDocument.aspx?d=902583; Conference Committee Substitute No. 2 for Senate Substitute for House Committee Substitute for House Bill No. 1685, T ruly Agreed T o and Finally Passed, Missouri, 97th General Assembly, 2014, http://www.house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills141/billpdf/truly/HB1685T .PDF; Public Act Numbers 345 and 346 of 2014, State of Michigan, 97 th Legislature, http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(gb2onn55vxkuylrvqmn3axrp))/mileg.aspx?page=PublicActs.

45 Arthur Caplan, “Bioethicist: ‘Right to T ry’ Law More Cruel T han Compassionate,” NBC NEWS, May 18, 2014, http://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/bioethicist -right-try-law-more-cruel-compassionate-n108686; and David Kroll, “T he False Hope Of Colorado‘s ‘Right T o T ry’ Investigational Drug Law,” Forbes, May 19, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2014/05/19/the-false-hope-of-colorados-right-to-try-act/.

46 See, generally, Elizabeth Richardson, “Health Policy Brief: Right -to-T ry Laws,” Health Affairs, March 5, 2015, http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=135.

47 Phoebe Mounts, Kathleen Sanzo, and Jacqueline Berman, “A Closer Look At New Federal ‘Right T o T ry’ Law,” Law 360, June 1, 2018, https://www.law360.com/articles/1048871/a-closer-look-at-new-federal-right-to-try-law.

Congressional Research Service

8

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Manufacturer-Related Issues

The manufacturer faces a complex decision in determining whether or not to give its experimental drug to a patient who requests it. In making a decision in each case, the manufacturer considers available supply of the drug, liability, safety, and whether adverse event or outcome data wil

affect FDA’s consideration of a new drug application in the future.

Available Supply

s consideration of a new drug application in the future.

Available Supply

If a manufacturer has only a tiny amount of an experimental drug, that paucity may limit distribution, no matter what the manufacturer would like to do.48 Sponsors of early clinical research make small smal amounts of experimental products for use in small smal Phase I1 safety trials, and progressively more for Phase II2 and III3 trials. Although one or two additional patients may not

cause supply problems, a manufacturer does not know how many expanded access requests it will wil receive. Investment in building up to large-scale production usuallyusual y comes only after reasonable assurance that the product will wil get FDA approval. For a company to redirect its current

manufacturing capacity involves financial, logistic, and public relations decisions. A solution—though not immediately effective—might be committing additional resources to increase production.30

Liability

Liability

In discussing expanded access, some manufacturers have raised liability concerns if patients report injury from the investigational products.49 Whether these concerns become il ustrated by report injury from the investigational products.31 In the state right-to-try laws, there are some attempts to protect manufacturers or clinicians from state medical practice or tort liability laws.32 If there are legitimate concerns, Congress could consider acting as it has in past, choosing diverse approaches to protect manufacturers, clinicians, and patients in a variety of situations.33 Whether these concerns become illustrated by court cases and how any issues may be resolved in future laws are beyond the scope of this discussion.34

Limited Staff and Facility Resources

discussion.50

Limited Staff and Facility Resources

Any energy put into setting up and maintaining a compassionate usean expanded access program could take away from a company'’s focus on completing clinical trials, preparing an NDA, and launching a product into the market. While this delay would have bottom-line implications, one CEO, in denying expanded access, portrayed the decision as an equity issue, saying, "“We held firm to the ethical standard that, were the drug to be made available, it had to be on an equitable basis, and we couldn'

couldn’t do anything to slow down approval that will wil help the hundreds or thousands of [individuals]."” Pointing to ways granting expanded access might divert them from research tasks

and postpone approval, he said, "“Who are we to make this decision?"35

”51

48 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” p. 25. 49 For example, see Sam Adriance, “Fighting for the ‘Right T o T ry’ Unapproved Drugs: Law as Persuasion,” Yale Law Journal Forum , vol. 124, December 4, 2014, http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/right -to-try-unapproved-drugs; Darshak Sanghavi, Meaghan George, and Sara Bencic, “Individual Patient Expanded Access: Developing Principles For A Structural And Regulatory Framework,” Health Affairs Blog, July 31, 2014, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/07/31/individual-patient -expanded-access-developing-principles-for-a-structural-and-regulatory-framework/; and Elizabeth Richardson, “Health Policy Brief: Right -to-T ry Laws,” Health Affairs, March 5, 2015, http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=135.

50 CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10115, Federal “Right-to-Try” Legislation: Legal Considerations. 51 Steve Usdin, “Josh Hardy chronicles: How Chimerix, FDA grappled with providing comp assionate access to Josh Hardy,” BioCentury, March 31, 2014, https://www.biocentury.com/biocentury/regulation/2014-03-31/how-chimerix-fda-grappled-providing-compassionate-access-josh-hardy.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 11 link to page 11 Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Data for Assessing Safety and Effectiveness

Data for Assessing Safety and Effectiveness

By distributing the drug outside a carefully designed clinical trial, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to collect the data that would validly assess safety and effectiveness. Without those data, a manufacturer could be hampered in presenting evidence of safety and effectiveness when applying to FDA for approval or licensure.36

Clinical trials are structured to assess the safety of a drug as well wel as its effectiveness. The trial design may exclude subjects who are so ill il from either the disease or condition for which the drug is being

tested or another disease or condition. This allowsal ows, among other reasons, the analysis of adverse events in the context of the drug and disease of interest. The patients who would seek a drug under a right-to- to try pathway are likely to be very ill il and likely to experience serious health events. Those events could be a result of the drug or those events could be unrelated. They would present difficulties both scientific and public relations-wise to the manufacturer. A manufacturer would may

avoid those risks by choosing to not provide a drug outside a clinical trial.

Disclosure

As mentioned, FDA has indicated that it is not aware of any instances in which safety and effectiveness data obtained from expanded access have prevented approval of a drug, but there

are instances in which such data have been used to support approval (see the section “Use of

Adverse Event Data from Expanded Access”).

Disclosure

It is unclear how many people request and are denied expanded access to experimental drugs by manufacturers. This lack of information makes devising solutions to manufacturer-based

obstacles difficult. Although FDA reports the number of requests it receives, manufacturers do not (nor does FDA require them to do so). The number of individuals who approach

manufacturers is unknown.

In December 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act amended the FFDCA to require a manufacturer or distributor of an investigational drug intended for a serious disease or condition to make its policies on evaluating and responding to compassionate use requests publicly available.52 However, the law does not require manufacturers to disclose how many requests they receive,

grant, or deny.

A 2019 GAO study surveyed 29 drug manufacturers regarding their policies for individual patient access to investigational drugs.53 Of those surveyed, 23 reported using their websites to communicate whether they considered individual requests for access to investigational drugs

outside of clinical trials; the remaining 6 were in the process of developing this content for their websites. Of those 23 manufacturers, 19 stated they were wil ing to consider requests, while 4 stated they were not. Of the 19 drug manufacturers wil ing to consider requests, 13 indicated that they require the relevant regulatory authority to review requests, of which 6 specified that they

require FDA to review requests for access in the United States.

The Right to Try Act manufacturers is unknown, although some reports suggest that it is much larger than the number of successful requests that then go to FDA. For example, one report indicated that the manufacturer of an investigational immunotherapy drug, which does not have a compassionate use program, received more than 100 requests for it.37

Federal Legislation Before the Right to Try Act

For the past several Congresses, Members have introduced bills with varying approaches to increasing patient access to investigational drugs. Some followed the Goldwater Institute model (to take FDA out of the process) and some proposed requiring manufacturers to publicize their compassionate use policies and decisions or requiring that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) study the patterns of patient requests and manufacturer approvals and denials, barriers to drug sponsors, and barriers in the application process.

Congress enacted two larger bills that each included sections on expanded access: the 21st Century Cures Act (Section 3032, P.L. 114-255) and the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (Section 610, P.L. 115-52).

In December 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act added a new Section 561A to the FFDCA: "Expanded Access Policy Required for Investigational Drugs." It required "a manufacturer or distributor of an investigational drug to be used for a serious disease or condition to make its policies on evaluating and responding to compassionate use requests publicly available."38 In August 2017, the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 amended the date by which a company must post its expanded access policies and required the Secretary to convene a public meeting to discuss clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, issue guidance and a report, issue or revise guidance or regulations to streamline IRB review for individual patient expanded access protocols, and update any relevant forms associated with individual patient expanded access. It also required GAO to report to Congress on individual access to investigational drugs through FDA's expanded access program.39

The Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act of 2017 (S. 204, P.L. 115-176)

On January 24, 2017, Senator Johnson introduced S. 204, the Trickett Wendler Right to Try Act of 2017, and the bill bil had 43 cosponsors at that time. On August 3, 2017, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions discharged the bill bil by unanimous consent. The same day,

52 FFDCA §561A [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0], as added by P.L. 114-255, §3032. 53 GAO, “Investigational Drugs: FDA and Drug Manufacturers Have Ongoing Efforts to Facilitate Access for Some Patients,” pp. 24-26.

Congressional Research Service

10

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

by unanimous consent. The same day, the Senate passed S. 204, the Trickett Wendler, Frank MongielloMongiel o, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina

Bel ina Right to Try Act (P.L. 115-176) with a substantial amendment also by unanimous consent.

On March 13, 2018, Representative Fitzpatrick introduced a related bill, bil , H.R. 5247, the Trickett

Wendler, Frank MongielloMongiel o, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Bel ina Right to Try Act of 2018, and the bil the bill had 40 cosponsors at that time. On March 21, the House passed the bill bil (voting 267-149). The House accepted the Senate bill bil on May 22, 2018 (voting 250-169), and the President Trump

signed it into law on May 30, 2018.

This section of the report first summarizes the provisions in the Right to Try Act. It then discusses how those provisions address some of the obstacles described in the previous section.

Provisions in the Right to Try Act

The Right to Try Act adds to the FFDCA a newadded FFDCA Section 561B, Investigational Drugs for Use by Eligible Patients. It has a separate paragraph that is not linked to an FFDCA section to limit the liability to all to al entities involved in providing an eligible drug to an eligible patient. It concludes with a "“Sense

of the Senate"” section.

The new

FFDCA Section 561B has several provisions that mirror many steps in FDA'’s expanded access

program. A major difference is that the new section is designed to exist wholly outside the

jurisdiction and participation of FDA. These provisions

-

define an eligible patient as one who (1) has been diagnosed with a life-

threatening disease or condition, (2) has exhausted approved treatment options and is unable to participate in a clinical trial involving the eligible

- 54

define an eligible investigational drug as an investigational drug (1) for which a

Phase 1 clinical trial has been completed, (2) that FDA has not approved or licensed for sale in the United States for any use, (3) that is the subject of

a new drug applicationan NDA or BLA pending FDA decision or is the subject of an activeinvestigational new drug application being studied for safety and effectiveness in a clinical trialIND and is being studied in a clinical trial that is intended to form the primary basis of the drug’s effectiveness, and (4) for which the manufacturer has not discontinued active development or production and which the FDA has not placed on clinical hold;55 and and - exempt use under this section from parts of the FFDCA

sectionsand FDA regulations regarding misbranding, certain labeling and directions for use, drug approval,andinvestigational newdrugsdrug regulations;

The new , protection of human subjects, and IRBs.56

FFDCA Section 561B has provisions that had not been necessary when access had been granted under FDA auspices. These provisions

prohibit the Secretaryincludes provisions that address use of clinical outcomes and reporting of certain information to FDA. These provisions prohibit the Secretary (FDA) from using clinical outcome data related to use under this section"“to delay or adversely affect the review or approval of suchdrug"drug” unless theSecretaryFDA determines its use is"“critical to determining [its] safety,"” at which time theSecretaryFDA must provide written notice to the sponsor to include a 54 FFDCA §561B(a)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(a)(1)]. 55 FFDCA §561B(a)(2) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(a)(2)]. 56 FFDCA §561B(b) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(b)]. Congressional Research Service 11 Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs public health justification, or unless the sponsor requests use of such clinical outcome data;- 57

require the sponsor to submit an annual summary to

the SecretaryFDA to include"“the number of doses supplied, the number of patients treated, the uses for which the drug was made available,"; and require the Secretary”;58 and require FDA to post an annual summary onthe FDAits website to include the number of drugs for which (1)the SecretaryFDA determined the need to use clinical outcomes in the review or approval of an investigational drug, (2) the sponsor requested that clinical outcomes be used, and (3) the clinical outcomes were not used.

59

The act has an uncodified section titled "“No Liability," ” which does not correspond to actions inthe FDA's ’s expanded access program. ItThe provision states that, related to use of a drug under the new

FFDCA Section 561B,

" “no liabilityshall lieshal lie against ... a sponsor or manufacturer; or ... a prescriber, dispenser, or other individual entity ... unless the relevant conduct constitutes reckless orwillfulwil ful misconduct, gross negligence, or an intentional tort under any applicable State law"”; and-

no liability,

"“determination not to provide access to an eligible investigational drug."

”60 Discussion of Selected Provisions in the Right to Try Act

Will the RTT Act result in more patients getting access to investigational drugs? Will it ease hurdles for those who would have gone through FDA's expanded use process? This report discusses several provisions in the RTT Act that Congress could consider as it oversees the law's implementation.

Eligible Patients

The RTT

Eligible Patients

The Right to Try Act defines eligibility, in part, as a person diagnosed with a "“life threatening

disease or condition."” That definition differs from many of the state-passed laws, as well wel as from what FDA preferred: that the definition make clear patients were eligible only if they faced a "terminal illness."40 The commissioner noted that "“terminal il ness.”61 FDA Commissioner Gottlieb noted that “[many] chronic conditions are life-threatening, but medical and behavioral interventions make them manageable."41”62 Examples of

such diseases or conditions are diabetes and heart disease.

Speaking in support of right to try billsbil s, supporters told of people facing death who, with no alternatives remaining, would be willingwil ing to risk an experimental drug that might even hasten their death.4263 By not limiting eligibility eligibility to those at the end of options, the RTT Act could allow Right to Try Act could al ow

people with chronic conditions to take extreme risks rather than live a normal lifespan with treatments now available. Because of the broad eligibility, manufacturers could see a significant increase in requests.

If a new Congress revisits the RTT

57 FFDCA §561B(c) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(c)]. 58 FFDCA §561B(d)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(1)]. 59 FFDCA §561B(d)(2) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(2)]. 60 P.L. 115-176, §2(b). 61 Statement of Scott Gottlieb, M.D., Commissioner of Food and Drugs, before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, October 3, 2017, https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/T estimony/ucm578634.htm.

62 Statement of Scott Gottlieb, M.D., Commissioner of Food and Drugs, before the Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, October 3, 2017, https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/T estimony/ucm578634.htm.

63 For example, Rep. Barton during House floor debate on S. 204, Congressional Record, May 22, 2018, p. H4359, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/05/22/CREC-2018-05-22-pt1-PgH4355.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

12

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

increase in requests. If Congress revisits the Right to Try Act, Members might consider the

Act, Members might consider the definition and clarify what they want for patients and manufacturers.

Informed Consent

The RTT

The Right to Try Act makes it mandatory that before eligible patients receive an investigational drug, they give the treating doctor their informed consent in writing—but it does not define "

“informed consent."

Other right-to-try bills”64 Other right to try bil s, including the House-passed H.R. 5247 (115th Congress), included more specific direction for consent, such as criteria already laid out in 21 CFR Part 50.43 The new law65 The Right to Try Act neither provides nor requires the development of such criteria. It thus may weaken patient protections that FDA'’s expanded use policyaccess program provides. The Right to Try Act also eliminatesThe RTT Act also seems to eliminate the requirement that an IRB review the investigational use of

a drug.

66

If Congress decides to revisit RTTthe Right to Try Act, it may seek to create a more explicit informed consent requirement and some outside oversight to reduce the risk to patients either by well-wel -

meaning but less knowledgeable physicians or by unscrupulous actors some RTT opponents anticipate.44

Data to FDA

Is a drug effective—does it do what it is meant to do? Is a drug safe—do the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks? Neither of these questions can be discussed without data on what happened to those who used the drug.

Clinical Outcomes

opponents of the law

anticipate.67

Data to FDA

Clinical Outcomes

It sometimes takes thousands of patients to establish an accurate evaluation of a drug'’s safety and effectiveness. Researchers exclude from the clinical trial patients who—for reasons other than the drug's efficacydrug’s effectiveness—may not show evident benefit from the drug. Those are the patients who

would get access through the RTT pathway.

The RTT Act appears to protect the drug sponsor: it prohibits the SecretaryRight to Try Act pathway.

The Right to Try Act prohibits FDA from using clinical outcome data related to use under this section "“to delay or adversely affect the review or approval of such drug."”68 This might make a

sponsor more likely to approve the use of its investigational drug under this RTT pathway. The RTTRight to Try Act, however, includes an exception. It allowstwo exceptions. It al ows FDA to use those data if the Secretary agency determines their use is "“critical to determining [the drug'’s] safety."” or if the sponsor requests use of such outcomes.69 If drug sponsors find that this remains an obstacle to their permitting RTT access to investigational drugs, Congress could work with them, FDA, and patient advocacy groups to

devise another approach.

64 FFDCA §561B(a)(1)(C) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(a)(1)(C)]. 65 21 C.F.R. 312.305(c)(4); Rep. Walden, during House debate on S. 204, May 22, 2018, pp. H4357-4358, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/05/22/CREC-2018-05-22-pt1-PgH4355.pdf; and Letter to Speaker Ryan and Minority Leader Pelosi, dated May 21, 2018, from 104 advocacy groups, including the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, the American Lung Association, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, as entered into the record by Rep. Castor during House debate on S. 204, May 22, 2018, p. H4358, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/05/22/CREC-2018-05-22-pt1-PgH4355.pdf.

66 FFDCA §561B(b) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(b)]. 67 Rep. Pallone, during House floor debate on S. 204, Congressional Record, May 22, 2018, p. H4360, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/05/22/CREC-2018-05-22-pt1-PgH4355.pdf.

68 FFDCA §561B(c)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(c)(1)]. 69 FFDCA §561B(c)(1)(A) & (B) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(c)(1)(A)&(B)].

Congressional Research Service

13

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Adverse Events

The Right to Try Act requires the manufacturer to report once a year to FDA, including an account of al serious adverse events that occurred in the preceding 12 months.70 It does not require immediate reporting of adverse events.71 This is less than what FDA requires of sponsors of approved drugs and investigational drugs provided in clinical trials or under expanded access.

Al must periodical y inform FDA of such events—and immediately if the event is “serious and unexpected.”72 An adverse event may not be clearly attributable to a drug. A clustering of such

reports, though, could signal FDA that this might be something worth exploring.

If Congress were to reconsider the Right to Try Act, it could explore with stakeholders—FDA, drug sponsors, and physicians and patients who use this pathway—ways to make data available to advance the goal of developing safe and effective drugs while protecting the legitimate business

interests of manufacturers and the access of seriously il individuals to try risky drugs.

Disclosure

The Right to Try Act requires the manufacturer or sponsor to submit an annual summary to FDA to include “the number of doses supplied, the number of patients treated, the uses for which the drug was made available, and any known serious adverse events.”73 FDA has issued a proposed rule to implement this annual reporting requirement, which wil not become effective until FDA promulgates a final rule and establishes a deadline for such reports.74 The Right to Try Act also

requires FDA to post an annual summary on its website to include the number of drugs for which (1) the agency has determined the need to use clinical outcomes in the review or approval of an investigational drug, (2) the sponsor requested that clinical outcomes be used, and (3) the clinical

outcomes were not used.75

Congress may choose to revisit these reporting requirements, to require the manufacturer or sponsor to provide more information to FDA, to require FDA to make public additional

information, or both.

Financial Cost to Patient

FDA’s expanded use process permits a sponsor to charge a patient for the investigational drug, but only to recover the direct costs of making the drug available, as defined under 21 C.F.R. 312.8(d).76 This includes costs to manufacture the drug in the quantity needed or costs to acquire the drug from another source (e.g., shipping, handling, storage).77 The sponsor cannot charge for development costs or to make a profit. The Right to Try Act extends this requirement to drugs that

70 FFDCA §561B(d)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(1)]. 71 Letter to Speaker Ryan and Minority Leader Pelosi, dated May 21, 2018, from 104 advocacy groups, including the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, the American Lung Association, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Societ y, as entered into the record by Rep. Castor during House debate on S. 204, May 22, 2018, p. H4358, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2018/05/22/CREC-2018-05-22-pt1-PgH4355.pdf. 72 21 C.F.R. §314.80(c)(1)(i), 21 C.F.R. §312.32(c)(1). 73 FFDCA §561B(d)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(1)]. 74 FDA, “Annual Summary Reporting Requirements Under the Right to T ry Act,” 85 Federal Register 44803, July 24, 2020. 75 FFDCA §561B(d)(2) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(2)]. 76 21 C.F.R. §312.8(d)(1). 77 FDA, “Guidance for Industry: Charging for Investigational Drugs Under an IND—Questions and Answers,” p. 6.

Congressional Research Service

14

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

sponsors may provide under this pathway.78 However, it does not require insurers to pay for the drug—or pay for doctor office visits or hospital stays associated with its use or potential adverse outcomes—and these costs may therefore fal on the patient. Congress may consider examining

the effect of the Right to Try Act on costs incurred by patients.

Liability Protections

Manufacturers may see liability costs as an obstacle to providing an investigational drug to patients. The no-liability provision in the Right to Try Act seems to remove that obstacle, although it may leave the patient with limited legal recourse. In the past, Congress has sometimes tried to protect both recipients and the manufacturer from harm (e.g., the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 and the Smal pox Emergency Personnel Protection Act of 2003). In those cases, where Congress felt the public health benefit to the larger group outweighed the

smal er risk to some, the federal government accepted responsibility for compensating injured patients and indemnifying manufacturers from lawsuits.79 That has not been the motivating force behind the Right to Try Act. Discussions of earlier versions of liability protections raised concerns that they might not fully protect the manufacturer.80 As patients use drugs under the Right to Try Act pathway, it is possible that they wil test such protections in the courts. This is

yet another issue that Congress might pursue.

Concluding Comments Several questions remain regarding the impact of the Right to Try Act on patients, drug

manufacturers, and FDA.

First: Will more patients get investigational drugs? The Right to Try Act

requires manufacturers or sponsors to report each year on the number of doses supplied and patients treated as a result of the law, as wel as what the drugs were used for and any known serious adverse events.81 Over time—and perhaps with

requesting other data—Congress could determine whether the law has had the effect its sponsors intended.

Second: Has the law removed the obstacles to access to investigational

drugs? While the Right to Try Act achieves proponents’ objective of removing

the FDA application step in a patient’s quest for an investigational drug, it does not address other obstacles—such as a limited drug supply or limits on staff and facility resources—that could lead a manufacturer to refuse access to its drugs. Further, it is not clear whether it sufficiently deals with the obstacles it does address—use of clinical outcomes data and liability protection. While the

reporting required by the Right to Try Act was not designed to answer those questions, Congress could ask GAO to evaluate the law’s impact on manufacturers’ wil ingness to provide investigational drugs under this pathway.

78 FFDCA §561B(b) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(b)]. 79 T he National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-660) established the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. T he Smallpox Emergency Personnel Protection Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-20) established the Smallpox Vaccine Injury Compensation Program .

80 Bexis, “Federal Right to T ry Legislation—Is It Any Better?” Drug & Device Law, September 5, 2017, https://www.druganddevicelawblog.com/2017/09/federal-right-to-try-legislation. 81 FFDCA §561B(d)(1) [21 U.S.C. §360bbb-0a(d)(1)].

Congressional Research Service

15

Expanded Access and Right to Try: Access to Investigational Drugs

Third: How will this affect FDA? One news article referred to the Right to Try

Act’s “bizarre twist,” as FDA must determine its role in implementing a law whose function is to remove FDA from the situation.82 Writing in opposition to the bil , four former FDA commissioners warned that it would “create a dangerous precedent that would erode protections for vulnerable patients.”83 That is something Congress may choose to address.

The Right to Try Act concludes with a “Sense of the Senate” section that appears to acknowledge that this legislation offers minimal opportunity to patients. It is explicit in asserting that the new

law “wil not, and cannot, create a cure or effective therapy where none exists.” The legislation, it says, “only expands the scope of individual liberty and agency among patients.” The drafters

realistical y end that phrase with “in limited circumstances.”

Author Information

Agata Bodie

Analyst in Health Policy

Acknowledgments

Susan Thaul, retired CRS Specialist in Drug Safety and Effectiveness, was the author of a previous version of this report.

Disclaimer

This document was prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS serves as nonpartisan shared staff to congressional committees and Members of Congress. It operates solely at the behest of and under the direction of Congress. Information in a CRS Report should n ot be relied upon for purposes other than public understanding of information that has been provided by CRS to Members of Congress in

connection with CRS’s institutional role. CRS Reports, as a work of the United States Government, are not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Any CRS Report may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without permission from CRS. However, as a CRS Report may include copyrighted images or material from a third party, you may need to obtain the permission of the copyright holder if you wish to copy or otherwise use copyrighted material.

82 For almost a decade, the Goldwater Institute has been working toward the goal it achieved with the signing of the Right to T ry Act. It says that “devise another approach.

Adverse Events

The RTT Act requires the manufacturer to report once a year to the Secretary, including an account of all serious adverse events that occurred in the preceding 12 months. It does not require immediate reporting of adverse events.45

This is less than what FDA requires of sponsors of approved and investigational drugs. All must periodically inform FDA of such events—and immediately if the event is "serious and unexpected."46

An adverse event may not be clearly attributable to a drug. A clustering of such reports, though, could signal FDA that this might be something worth exploring.