Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from October 17, 2018 to April 9, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

- Overview and Recent Developments

- Country Background

- The Hashemite Royal Family

- Political System and Key Institutions

- Short-Term Outlook

- The Economy

- The War in Syria and Its Impact on Jordan

- Syrian Refugees in Jordan

- Israel, the Palestinians, and U.S. Policy

- 2018 Public Protests and International Response

- Syrian Refugees in Jordan

- Water Scarcity and Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian Water Deal

- U.S. Relations U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan

NewU.S.-Jordanian Agreement on Foreign Assistance- Economic Assistance

- Humanitarian Assistance for Syrian Refugees in Jordan

- Loan Guarantees

- Military Assistance

- Foreign Military Financing

Defense Department(FMF) and DOD Security Assistance- Excess Defense Articles

- Recent Legislation

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan

, SFOPS Appropriations: FY2014-FY2019: FY2015-FY2020 Request - Table 2. U.S. Foreign Aid Obligations to Jordan: 1946-

20162017

Summary

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is considered a key U.S. partner in the Middle East. Although the United States and Jordan have never been linked by a formal treaty, they have cooperated on a number of regional and international issues over the years. Jordan's strategic importance to the United States is evident given ongoing instability in neighboring Syria and Iraq, Jordan's 1994 peace treaty with Israel, and uncertainty over the trajectory of Palestinian politics. Jordan also is a longtime U.S. partner in global counterterrorism operations. U.S.-Jordanian military, intelligence, and diplomatic cooperation seeks to empower political moderates, reduce sectarian conflict, and eliminate terrorist threats.

U.S. officials frequently express their support for Jordan. U.S. support, in particular, has helped Jordan address serious vulnerabilities, both internal and externalSummary

This report provides an overview of Jordanian politics and current issues in U.S.-Jordanian relations. It provides a brief discussion of Jordan's government and economy and of its cooperation with U.S. policies in the Middle East.

Several issues are likely to figure in decisions by Congress and the Administration on future aid to and cooperation with Jordan. These include Jordan's continued involvement in attempting to promote Israeli-Palestinian peace and the stability of the Jordanian regime, particularly in light of ongoing conflicts in neighboring Syria and Iraq. U.S. officials may also consider potential threats to Jordan from the Islamic State organization (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da'esh).

Annual aid to Jordan has nearly quadrupled in historical terms over the last 15 years. The United States has provided economic and military aid to Jordan since 1951 and 1957, respectively. Total bilateral U.S. aid (overseen by the Departments of State and Defense) to Jordan through FY2017 amounted to approximately $20.4 billion. Jordan also hosts over 2,000 U.S. troops. Although the United States and Jordan have never been linked by a formal treaty, they have cooperated on a number of regional and international issues over the years. Jordan's small size and lack of major economic resources have made it dependent on aid from Western and various Arab sources. President Trump has acknowledged Jordan's role as a key U.S. partner in countering the Islamic State, as many U.S. policymakers advocate for continued robust U.S. assistance to the kingdom.

U.S. support, in particular, has helped Jordan address serious vulnerabilities, both internal and external. Jordan's geographic position, wedged between Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, has made it vulnerable to the strategic designs of more powerful neighbors, but has also given Jordan an important role as a buffer between these countries in their largely adversarial relations with one another.

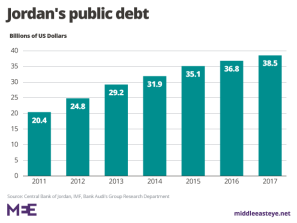

Public dissatisfaction with the economy is probably the most pressing concern for the Jordanian monarchy. Over the summer of 2018, widespread protests erupted throughout the kingdom in opposition to a draft tax bill and price hikes on fuel and electricity. Though peaceful, the protests drew immediate international attention because of their scale. Since then, the government has frozen or softened the proposed fiscal measures, but also has continued to work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on fiscal reforms to address a public debt that has ballooned to 96.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The United States has provided economic and military aid to Jordan since 1951 and 1957, respectively. Total bilateral U.S. aid (overseen by the Departments of State and Defense) to Jordan through FY2016 amounted to approximately $19.2 billion.

On February 14, 2018, then-U.S. Secretary of State Rex W. Tillerson and Jordanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ayman Safadi signed a new Memorandum of Understanding (or MOU) on U.S. foreign assistance to Jordan. The MOU, the third such agreement between the United and Jordan, commits the United States to provide $1.275 billion per year in bilateral foreign assistance over a five-year period for a total of $6.375 billion (FY2018-FY2022). This latest MOU represents a 27% increase in the U.S. commitment to Jordan above the previous iteration and is the first five-year MOU with the kingdom. The previous two MOU agreements had been in effect for three years. In line with the new MOU, for FY2019 President Trump is requesting $1.271 billion for Jordan, including $910.8 million in ESF, $350 million in FMF, and $3.8 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET).

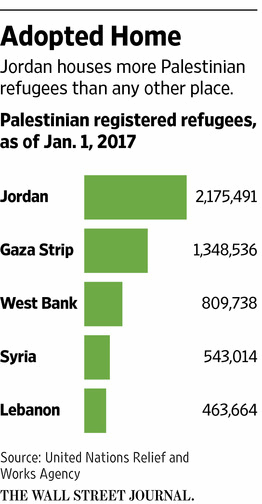

Overview

The 116th Congress may consider legislation pertaining to U.S. relations with Jordan. On February 18, 2016, President Obama signed the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-123), which authorizes expedited review and an increased value threshold for proposed arms sales to Jordan for a period of three years. It amended the Arms Export Control Act to give Jordan temporarily the same preferential treatment U.S. law bestows upon NATO members and Australia, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. S. 28, the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Extension Act, would reauthorize the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act (22 U.S.C. 275) through December 31, 2022.Since assuming the throne from his late father on February 7, 1999, Jordan's 56As the Trump Administration has enacted changes to long-standing U.S. policies on Israel and the Palestinians, which the Palestinians have criticized as unfairly punitive and biased toward Israel, Jordan has found itself in a difficult political position. While King Abdullah II seeks to maintain strong relations with the United States, he rules over a country where the issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the population; more than half of all Jordanian citizens originate from either the West Bank or the area now comprising the state of Israel. In trying to balance U.S.-Jordanian relations with Palestinian concerns, King Abdullah II has refrained from directly criticizing the Trump Administration on its recent moves, while urging the international community to return to the goal of a two-state solution that would ultimately lead to an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Overview and Recent Developments

Since assuming the throne from his late father on February 7, 1999, Jordan's 57-year-old monarch King Abdullah II bin Al Hussein (hereinafter King Abdullah II) has maintained Jordan's stability and strong ties to the United States. Although many

Although commentators frequently caution that Jordan's stability is fragile, the monarchy has remained resilient owing to a number of factors. These include a relatively strong sense of social cohesion, strong support for the government from both Western powers and the Gulf Arab monarchies, and an internal security apparatus that is highly capable and, according to human rights groups, uses vague and broad criminal provisions in the legal system to dissuade dissent.1

U.S. officials frequently express their support for Jordan. President Trump has acknowledged Jordan's role as a key U.S. partner in countering the Islamic State, as U.S. policymakers advocate for continued robust U.S. assistance to the kingdom. Annual aid to Jordan has nearly quadrupled in historical terms over the last 15 years. Jordan also hosts thousands of U.S. troops. According to President Trump's June 2018 War Powers Resolution Report to Congress, "At the request of the Government of Jordan, approximately 2,600 United States military personnel are deployed to Jordan to support Defeat-ISIS operations, to enhance Jordan's security, and to promote regional stability."2

Jordan may be addressing public discontent and bolstering nationalist sentiment at home by stoking tensions with Israel in support of the Palestinian cause.9 In late 2018, the king announced (via Twitter) that his government would not renew a provision in its 1994 peace treaty with Israel that allowed Israel access to the Jordanian territories of Baqoura and Al Ghumar, which are agricultural areas in northern and southern Jordan, respectively.10 According to one Jordanian commentator, "Domestically, the King's decision is a much-needed shot in the arm for the government at a time when it is facing public pressure over its unpopular economic policies."11

|

Holy Sites in Jerusalem12 Per arrangements with Israel dating back to 1967 (when the Israeli military seized East Jerusalem—including its Old City—from Jordan) and then subsequently confirmed in the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty, Israel acknowledges a continuing role for Jordan vis-à-vis Jerusalem's historic Muslim shrines.13 A Jordanian waqf (or Islamic custodial trust) has long administered the Temple Mount (known by Muslims as the Haram al Sharif or Noble Sanctuary) and its holy sites, and this role is key to bolstering the religious legitimacy of the Jordanian royal family's rule. Successive Jordanian monarchs trace their lineage to the Prophet Muhammad. Disputes over Jerusalem that appear to circumscribe King Abdullah II's role as guardian of the Islamic holy sites create a domestic political problem for the King. Jewish worship on the Mount/Haram is prohibited under a long-standing "status quo" arrangement that dates back to the era of Ottoman control before World War I. |

Several months later, Jordan expanded the membership of the Islamic Waqf Council (Islamic custodial trust), which Jordan appoints to oversee the administration of Jerusalem's Temple Mount (known by Muslims as the Haram al Sharif or Noble Sanctuary) and its holy sites. The Islamic Waqf Council, which had been made up of 11 individuals with close ties to the monarchy, was expanded to 18, including several officials from the Palestinian Authority. The newly expanded council immediately defied a 16-year Israeli ban on Muslim worship at the Bab al Rahma building on the Temple Mount. Israel responded by arresting worshippers and activists while also temporarily banning several leaders of the council from accessing the Temple Mount. In March 2019, King Abdullah II spoke in the industrial city of Zarqa, where he stated, "To me, Jerusalem is a red line, and all my people are with me.... No one can pressure Jordan on this matter, and the answer will be no. All Jordanians stand with me on Jerusalem."14

These types of steps for appeasing an increasingly restive public arguably are vital for the government of Jordan, which has limited financial options for addressing discontent.15 Although the government has continued to work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on fiscal reforms, public debt has ballooned to 95% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and most of the government's budget is dedicated to salaries, pensions, and debt servicing, leaving few additional options to fund public sector job programs.16 King Abdullah II recently traveled to the United Kingdom, where UK officials pledged to partially guarantee a $1.9 billion World Bank loan to Jordan. In summer 2018, Gulf countries pledged $2.5 billion to Jordan in combined grants and loans.

Country Background

Although the United States and Jordan have never been linked by a formal treaty, they have cooperated on a number of regional and international issues for decades. Jordan's small size and lack of major economic resources have made it dependent on aid from Western and various Arab sources. U.S. support, in particular, has helped Jordan deal with serious vulnerabilities, both internal and external. Jordan's geographic position, wedged between Israel, Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, has made it vulnerable to the strategic designs of its powerful neighbors, but has also given Jordan an important role as a buffer between these countries in their largely adversarial relations with one another.

Jordan, created by colonial powers after World War I, initially consisted of desert or semidesert territory east of the Jordan River, inhabited largely by people of Bedouin tribal background. The establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 brought large numbers of Palestinian refugees to Jordan, which subsequently unilaterally annexed a Palestinian enclave west of the Jordan River known as the West Bank.317 The original "East Bank" Jordanians, though probably no longer a majority in Jordan, remain predominant in the country's political and military establishments and form the bedrock of support for the Jordanian monarchy. Jordanians of Palestinian origin comprise an estimated 55% to 70% of the population and generally tend to gravitate toward the private sector due to their alleged general exclusion from certain public-sector and military positions.4

The Hashemite Royal Family

Jordan is a hereditary constitutional monarchy under the prestigious Hashemite family, which claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad. King Abdullah II (age 5657) has ruled the country since 1999, when he succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father, the late King Hussein, after a 47-year reign. Educated largely in Britain and the United States, King Abdullah II had earlier pursued a military career, ultimately serving as commander of Jordan's Special Operations Forces with the rank of major general. The king's son, Prince Hussein bin Abdullah (born in 1994), is the designated crown prince.5

The king appoints a prime minister to head the government and the Council of Ministers (cabinet). On average, Jordanian governments last no more than 15 months before they are dissolved by royal decree. This seems to be done in order to bolster the king's reform credentials and to distribute patronage among a wide range of elites. The king also appoints all judges and is commander of the armed forces.

Political System and Key Institutions

The Jordanian constitution, most recently amended in 2016, empowersgives the king with broad executive powers. The king appoints the prime minister and may dismiss him or accept his resignation. He also has the sole power to appoint the crown prince, senior military leaders, justices of the constitutional court, and all 75 members of the senate. The king appoints, as well as cabinet ministers. The constitution enables the king to dissolve both houses of parliament and postpone lower house elections for two years.620 The king can circumvent parliament through a constitutional mechanism that allows provisional legislation to be issued by the cabinet when parliament is not sitting or has been dissolved.721 The king also must approve laws before they can take effect, although a two-thirds majority of both houses of parliament can modify legislation. The king also can issue royal decrees, which are not subject to parliamentary scrutiny. The king commands the armed forces, declares war, and ratifies treaties. Finally, Article 195 of the Jordanian Penal Code prohibits insulting the dignity of the king (lèse-majesté), with criminal penalties of one to three years in prison.

Jordan's constitution provides for an independent judiciary. According to Article 97, "Judges are independent, and in the exercise of their judicial functions they are subject to no authority other than that of the law." Jordan has three main types of courts: civil courts, special courts (some of which are military/state security courts), and religious courts. In Jordan, state security courts administered by military (and civilian) judges handle criminal cases involving espionage, bribery of public officials, trafficking in narcotics or weapons, black marketeering, and "security offenses." Overall, theThe king may appoint and dismiss judges by decree, though in practice a palace-appointed Higher Judicial Council manages court appointments, promotions, transfers, and retirements.

Although King Abdullah II has envisionedin 2013 laid out a vision of Jordan's gradual transition from a constitutional monarchy into a full-fledged parliamentary democracy,822 in reality, successive Jordanian parliaments have mostly complied with the policies laid out by the Royal Court. The legislative branch's independence has been curtailed not only by a legal system that rests authority largely in the hands of the monarch, but also by carefully crafted electoral laws designed to produce propalace majorities with each new election.923 Due to frequent gerrymandering in which electoral districts arguably are drawn to favor more rural progovernment constituencies over densely populated urban areas, parliamentary elections have produced large progovernment majorities dominated by representatives of prominent tribal families. In addition, voter turnout tends to be much higher in progovernment areas since many East Bank Jordanians depend on family/tribal connections as a means to access patronage jobs.

Short-Term Outlook

In late 2018, the outlook for the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, a vital U.S. partner in the Middle East, is mixed. On the one hand, as conflicts in Syria and Iraq have abated somewhat, the kingdom faces improved prospects for stable borders, a resumption of trade with its neighbors, and the possible repatriation of hundreds of thousands of refugees. On the other hand, continuing economic discontent and sensitivity among the public regarding recent U.S. policy changes on Israel and the Palestinians have placed Jordan in a difficult political position.

Public dissatisfaction with the economy is probably the most pressing concern for the monarchy. Over the summer of 2018, widespread protests erupted throughout the kingdom in opposition to a draft tax bill and price hikes on fuel and electricity. Though peaceful, the protests drew immediate international attention because of their scale. Since summer, the government has continued to work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on fiscal reforms to address a public debt that has ballooned to 96.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

As the Trump Administration has enacted changes to long-standing U.S. policies on Israel and the Palestinians, which have been perceived by the Palestinians to be unfairly punitive and biased toward Israel, Jordan has been placed in a difficult political position. While King Abdullah II seeks to maintain strong relations with the United States, he rules over a country where the issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the Jordanian population; it is estimated that more than half of all Jordanian citizens originate from either the West Bank or the area now comprising the state of Israel. In trying to balance U.S.-Jordanian relations with concern for Palestinian rights, King Abdullah II has refrained from directly criticizing the Trump Administration on its recent moves, while urging the international community to return to the goal of a two-state solution that would ultimately lead to an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.10

|

|

Area: 89, Population: Ethnic Groups: Arabs Religion: Sunni Muslim 97.2%; Christian 2.2%; Buddhist 0.4%; Hindu 0.1% Percent of Population Under Age 25: Literacy: 95.4% (2015) Youth Unemployment: |

Source: Graphic created by CRS; facts from CIA World Factbook and World Bank.

The Economy

With few natural resources and a small industrial base, Jordan has an economy that depends heavily on external aid, tourism, expatriate worker remittances, and the service sector. Among the long-standing problems Jordan faces are poverty, corruption, slow economic growth, and high levels of unemployment. The government is by far the largest employer, with between one-third and two-thirds of all workers on the state's payroll. These public sector jobs, along with government-subsidized food and fuel, have long been part of the Jordanian government's "social contract" with its citizens.

In the past decade, this arrangement between state and citizen has become more strained. When oil prices skyrocketed between 2007 and 2008, the government had to increase its borrowing in order to continue fuel subsidies. The 2008 global financial crisis was another shock to Jordan's economic system, as it depressed worker remittances from expatriates. The unrest that spread across the region in 2011 further exacerbated Jordan's economic woes, as the influx of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees increased demand for state services and resources. Moreover, tourist activity, trade, and foreign investment decreased in Jordan after 2011 due to regional instability.

Finally, Jordan, like many other countries, has experienced uneven economic growth, with higher growth in the urban core of the capital Amman and stagnation in the historically poorer and more rural areas of southern Jordan. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Amman is the most expensive Arab city and the 25th-most expensive city to live in globally.24to live in.11

Popular economic grievances have spurred the most vociferous protests in Jordan. Youth unemployment is high, as it is elsewhere in the Middle East, and providing better economic opportunities for youngeryoung Jordanians outside of Amman is a major challenge. Large-scale agriculture is not sustainable because of water shortages, so government officials are generally left providing young workers with low-wage, relatively unproductive civil service jobs. How the Jordanian education system and economy can respond to the needs of its youth has been and will continue to be one of the defining domestic challenges for the kingdom in the years ahead.

|

|

|

Source: Middle East Eye |

2018 Public Protests and International Response

Over the past year, Jordan's efforts to cut spending and raise revenue have faced significant public resistance. In 2016, the IMF and Jordan reached a three-year, $723 million extended fund facility (EFF) agreement that commits Jordan to improving the business environment for the private sector, reducing budget expenditures, and reforming the tax code. As a result, in 2017 Jordan enacted a Value Added Tax (VAT) on common goods to raise revenue. The government also is in the process of eliminating popular subsidies on critical commodities such as flour.

To comply further with IMF-mandated reforms, the Jordanian government drafted a new tax bill to increase personal income taxes and thus raise government revenue and ease the public debt burden (see Figure 2). The draft tax bill would have lowered the minimum taxable income level in order to expand the tax base from 4.5% of workers to 10%.1225 It also would have raised corporate taxes on banks and reclassified tax evasion as a felony rather than a misdemeanor.

In late May 2018, as the bill drew closer to passage and after an IMF team visited Jordan to review its economic reform plan, demonstrations began across the country. On May 30, Jordanian unions and professional associations held a massive general strike against the tax bill and were joined by many younger protesters who denounced recent price hikes on fuel and electricity. Days later, King Abdullah II ordered the government to freeze a 5.5% increase in the price of fuel and a 19% increase in electricity prices. For days, protests continued throughout the country, with some protesters calling for parliament to be dissolved and the political system to be reformed.

On June 4, Prime Minister Hani Mulki resigned, and King Abdullah II appointed Education Minister and former World Bank economist Omar Razzaz as prime minister. A change in prime minister is considered fairly routine in Jordanian politics, and protesters decried it as an insufficient response to their demands. Large-scale demonstrations continued for two more days, and on June 7 the government announced that it was withdrawing the bill from immediate consideration and sending it back to parliament for revision.

On June 11, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia held a summit in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, where they collectively pledged $2.5 billion for Jordan. The aid includes a included a $1 billion deposit at the Central Bank of Jordan. The IMF also is supportingsupported the Jordanian government's decision to revise the tax bill, noting that fiscal reforms should not come at the expense of political stability.1326

This was not the first time that the Jordanian monarchy backtracked on reforms in the face of public pressure. In 1989, 1996, and 2012, Jordanian monarchs responded to mass demonstrations with limited political reforms (new elections and electoral laws, constitutional amendments, anticorruption measures) that did not fundamentally alter the political system. In times of crisis, the government often appeals for Jordanian unity, while calling the opposition divisive or even disloyal.1427 King Abdullah II's turn toward the Gulf for a financial bailout also has precedents. In 2012, at the height of unrest in the Middle East, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries pledged $5 billion to Jordan.

Protests in JordanThis year'sThe 2018 demonstrations were not organized by Islamists or pro-Palestinian activists focusing primarily on political grievances, but were decentralized and focused mainly on economic themes.1528 Many protesters hailed from traditional strongholds of the monarchy, calling into question how King Abdullah II will be able to manage in the future if he is pressured to enact fiscal austerity measures.

At the forefront of ongoing protests in Amman since 2018 have been participants in Hirak (tribal youth movements that began protesting in 2011).29 According to one account, "What makes this opposition volatile is its free-flowing, networked nature. Youth demonstrations are leaderless but come in weekly waves, with each successive protest often larger than the last as participants learn and adapt." 30

In fall 2018, the Jordanian government proposed a new draft tax bill which raises personal and family exemptions for the poorest citizens. The Gulf monarchies also followed through with their $2.5 billion pledge to Jordan, providing (as mentioned above) $1 billion in central bank deposits, $600 million in loan guarantees, $750 million in direct budgetary support (spread over five years), and $150 million for school construction.16

The War in Syria and Its Impact on Jordan

Throughout Syria's civil war, Jordan has prioritized stability on its northern border and has worked with select Syrian rebel groups, the Asad regime, Israel, the United States, and—since its intervention in 2015— the Russian government, in ways intended to shield the kingdom from the war's fallout. In 2017, the United States, Russia, and Jordan agreed to a de-escalation zone along the Jordanian-Syrian border in order to reduce fighting and ensure that no Iranian-backed militias would be based near Jordan or Israel.

In summer 2018, Syrian military forces recaptured southwest Syria. Since then, the Syrian and Jordanian governments have engaged in talks about opening border crossings to allow for a resumption in bilateral trade and the possible return of Syrian refugees residing in Jordan.17 The kingdom had wanted to ensure that before Syria and Jordan fully normalize relations and reopen borders, the two sides work out a process for legally dealing with Jordanian fighters who traveled to Syria and Iraq.18 On October 15, 2018, Syria and Jordan reopened the Nassib border crossing to people and goods with the Jordanian government noting that Syrians entering Jordan must first obtain the necessary clearance.19

|

Islamic State (IS) Sympathizers Kill Four Security Personnel in Jordan In August 2018, IS sympathizers placed an improvised explosive device (IED) under a police vehicle which was stationed at a music festival in a predominately Christian area in the town of Fuheis. The IED remotely detonated, killing one officer. In the process of searching for the perpetrators of the attack, security forces laid siege to their hideout in a residential area of the town of Salt. In an exchange of fire that killed three militants, three more Jordanian personnel were killed. Several other suspects were arrested. This incident was the first terrorist attack inside Jordan since December 2016. According to one analysis, "Returning Jordanian jihadists with operational experience in Syria and Iraq are bringing with them IED and tactical expertise, and the attack shows increased bomb-making capabilities."20 |

31 In December 2018, parliament approved final modifications to the law, and personal income tax rates were adjusted to ensure that the poorest taxpayers were not adversely affected.32

Beyond the Gulf Arab monarchies, the international community also has increased efforts to boost economic growth in Jordan. In February 2019, the United Kingdom hosted an international donor's conference for Jordan, referred to as The London Initiative 2019. At the conference, donors (UK, France, Japan, and the European Investment Bank) pledged $2.6 billion to Jordan spread over several years. At the conference, the World Bank also announced that pending final approval, it intended to provide $1.9 billion in concessional loans to Jordan over the next two years.

Figure 2. Jordan's Weak Economy

Source: Stratfor

Syrian Refugees in Jordan

Source: Stratfor

Since 2011, the influx of Syrian refugees has placed tremendous strain on Jordan's government and local economies, especially in the northern governorates of Mafraq, Irbid, Ar Ramtha, and Zarqa. Due to Jordan's low population, it has one of the highest per capita refugee rates in the world. As of March 2019. As of October 2018, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are 671,919670,238 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan; 83% of all Syrian refugees live in urban areas, while the remaining 17% live in three camps—Azraq, Zaatari, and the Emirati Jordanian Camp (Mrajeeb al Fhood). Due to Jordan's small population size, it has one of the highest per capita refugee rates in the world.

|

|

Source: CRS Graphics. Note: M5 (purple line) is the main north-south highway in Syria. |

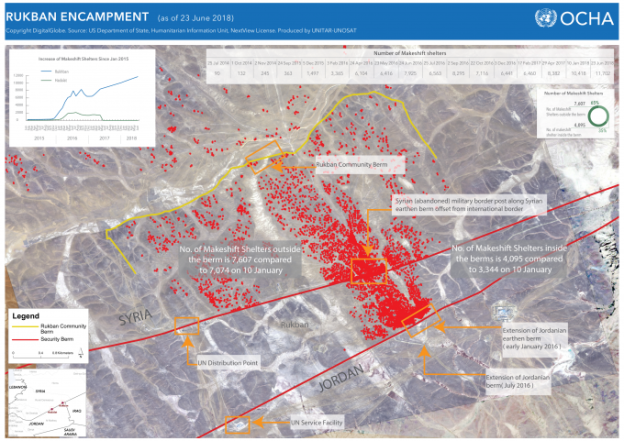

Another 4541,000 refugees are stranded in the desert along the northeastern Jordanian area bordering Syria and Iraq, known as Rukban. Though most of the refugees stranded at Rukban are women and children, a June 2016 IS terrorist attack near the border led Jordanian authorities to close the area, and access to Rukban is sporadic. In fall 2018, Syrian regime forces prevented food from entering the area from the Syrian side, eventually permitting a United Nations aid food delivery on October 17, 2018. According to one report,government forces reestablished control of southern Syria and often have prevented U.N. food shipments from reaching Rukban. Rukban is located within a 35-mile, U.S. -established "de-confliction zone" surrounding U.S. forces based at the At Tanf garrison near the Syrian-Iraqi-Jordanian triborder area.21

In recent months, Syrian and Russian reports have accused the United States of using refugees stranded at Rukban as "human shields" to protect the U.S. garrison at At Tanf from being attacked.34 In response, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a statement in March 2019, saying "Despite Syrian and Russian propaganda to the contrary, the United States is not restricting the movement of IDPs into or out of the camp at Rukban. The United States fully supports a process to allow IDPs freedom of movement that is free from coercion and allows for safe, voluntary, and dignified departures for those wishing to leave Rukban."35 According to the United Nations:

Discussions are ongoing with the main parties involved, including the Government of Syria, the Russian Federation, the United States and the Government of Jordan to further clarify the process and to address the concerns that have been raised by people in Rukban. The United Nations continues to reiterate the importance of a carefully planned, principled approach that ensures respect for core protection standards and does not expose vulnerable, and in many cases traumatized, displaced people to additional harm. All movements must be voluntary, safe, well-informed and dignified, with humanitarian access assured throughout. In parallel, the United Nations also continues to strongly advocate for additional humanitarian assistance for those who remain in Rukban.36

Figure 4. Rukban Camp

Triborder Area

|

|

|

Source: U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. |

Israel, the Palestinians, and U.S. Policy

The Jordanian government has long described efforts to secure a lasting end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as one of its highest priorities. In 1994, Jordan and Israel signed a peace treaty,22 and King Abdullah II has used his country's relationship with Israel to improve Jordan's standing with Western governments and international financial institutions, on which it relies heavily for external support and aid. Nevertheless, the persistence of Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues to be a major challenge for Jordan. The issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the population; it is estimated that more than half of all Jordanian citizens originate from either the West Bank or the area now comprising the state of Israel.23

|

Holy Sites in Jerusalem24 Per arrangements with Israel dating back to 1967 and then subsequently confirmed in their 1994 bilateral peace treaty, Israel acknowledges a continuing role for Jordan vis-à-vis Jerusalem's historic Muslim shrines.25 A Jordanian waqf (or Islamic custodial trust) has long administered the Temple Mount (known by Muslims as the Haram al Sharif or Noble Sanctuary) and its holy sites, and this role is key to bolstering the religious legitimacy of the Jordanian royal family's rule. Successive Jordanian monarchs trace their lineage to the Prophet Muhammad. Disputes over Jerusalem that appear to circumscribe King Abdullah II's role as guardian of the Islamic holy sites create a domestic political problem for the King. Jewish worship on the Mount/Haram is prohibited under a long-standing "status quo" arrangement. |

Since December 2017, when the Palestinians broke off high-level political contacts with the United States after President Trump's decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital and relocate the U.S. embassy there, Jordan has been caught in the middle of ongoing acrimony between the Trump Administration and the Palestinian Authority. Jordan has expressed solidarity with the Palestinians while also trying to encourage the Trump Administration to commit to the two-state solution. In a recent interview with Fox News, King Abdullah II said the following:

The President [Trump] from day one was committed to a fair and balanced deal for the Israelis and Palestinians to move the process forward. We're not too sure what the plan is, that's part of the problem, so it's more difficult for us to be able to step in and help. What I'm worried about is that we will go from the two state solution to a one state solution, which is a disaster for all of us in the region, including Israel. If most of the final status issues are being taken off the table then you can understand Palestinian frustration. So how do we build the bridges of confidence between Palestinians and the United States? Whatever people say, you cannot achieve a two state solution or a peace deal without the role of the Americans. So at the moment the Americans are speaking to one side and not speaking to the others and so that's the impasse we are at.26

During his January 2018 visit to Jordan, Vice President Mike Pence tried to reassure King Abdullah II that the United States is committed to "continue to respect Jordan's role as the custodian of holy sites; that we take no position on boundaries and final status. Those are subject to negotiation.... the United States of America remains committed, if the parties agree, to a two-state solution."27

In September 2018, the Administration announced that it would end all U.S. contributions to UNRWA. In Jordan, there are 2.1 million registered Palestinian refugees (or descendants of refugees) who have Jordanian citizenship. UNRWA serves the neediest of this population, administering facilities such as schools and health clinics within refugee "camps" (mostly urban neighborhoods) throughout Jordan.28 In 2017, UNRWA spent $175.8 million on operations in Jordan.29 To raise funds to cover UNRWA's budgetary shortfall, Jordan, the European Union, Sweden, Turkey, Germany, and Japan cochaired a September 2018 donor meeting in New York to garner financial and political support for UNRWA on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly.

|

|

Source: |

Water Scarcity and Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian Water Deal

Jordan is among the most water-poor nations in the world and ranks among the top 10 countries with the lowest rate of renewable freshwaterfresh water per capita.3037 According to the Jordan Water Project at Stanford University, Jordan's increase in water scarcity over the last 60 years is attributable to an approximate 5.5-fold population increase since 1962, a decrease in the flow of the Yarmouk River due to the building of dams upstream in Syria, gradual declines in rainfall by an average of 0.4 mm/year since 1995, and depleting groundwater resources due to overuse.31

To secure new sources of freshwater38 The illegal construction of thousands of private wells also has led to unsustainable groundwater extraction. The large influx of Syrian refugees has heightened water demand in the north and, according to USAID, "many communities in Jordan have long experienced tensions over water scarcity even before the arrival of 657,433 registered Syrian refugees in the last five years."39

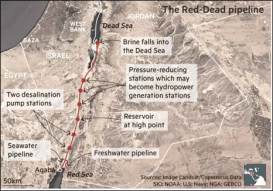

To secure new sources of fresh water, Jordan has pursued water cooperative projects with its neighbors. On December 9, 2013, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority signed a regional water agreement (officially known as the Memorandum of Understanding on the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project, see Figure 65) to pave the way for the Red-Dead Canal, a multibillion-dollar project to address declining water levels in the Dead Sea.40 The agreement was essentially a commitment to a water swap, whereby half of the water pumped from the Red Sea is to be desalinated in a plant to be constructed in Aqaba, Jordan. Some of this water is to then be used in southern Jordan. The rest is to be sold to Israel for use in the Negev Desert. In return, Israel is to sell fresh water from the Sea of Galilee to northern Jordan and sell the Palestinian Authority discounted fresh water produced by existing Israeli desalination plants on the Mediterranean. The other half of the water pumped from the Red Sea (or possibly the leftover brine from desalination) is to be channeled to the Dead Sea. The exact allocations of swapped water were not part of the 2013 MOU and were left to future negotiations.

|

|

Source: Financial Times, March 22, 2017. |

In 2017, with Trump Administration officials seemingly committed to reviving the moribund Israeli-Palestinian peace process, U.S. officials focused on finalizing the terms of the 2013 MOU. In July 2017, the White House announced that U.S. Special Representative for International Negotiations Jason Greenblatt had "successfully supported the Israeli and Palestinian efforts to bridge the gaps and reach an agreement," with the Israeli government agreeing to sell the Palestinian Authority (PA) 32 million cubic meters (MCM) of fresh water.3241

However, one recent2018 report indicatesindicated that some Israeli officials may have had misgivings about the project and arewere seeking to pull out of the deal.3342 According to one unnamed U.S. official cited by the report, "The United States told Israel that the U.S. supports the project and expects Israel to live up to its obligations under the Red-Dead agreement or find a suitable alternative that is acceptable to Israel and Jordan."34

Congress has supported the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project. P.L. 114-113, the FY2016 Omnibus Appropriations Act, specifies that $100 million in Economic Support Funds (ESF) be set aside for water sector support for Jordan, to support the Red Sea-Dead Sea water project. In September 2016, USAID notified Congress that it intended to spend the $100 million in FY2016 ESF-OCOOverseas Contingency Operations (OCO) assistance on Phase One of the project.35

U.S. officials frequently express their support for Jordan. President Trump has acknowledged Jordan's role as a key U.S. partner in countering the Islamic State, as many U.S. policymakers advocate for continued robust U.S. assistance to the kingdom. Annual aid to Jordan has nearly quadrupled in historical terms over the last 15 years. Jordan also hosts U.S. troops. According to President Trump's December 2018 War Powers Resolution Report to Congress, "At the request of the Government of Jordan, approximately 2,795 United States military personnel are deployed to Jordan to support Defeat-ISIS operations, enhance Jordan's security, and promote regional stability."46

The Trump Administration has enacted changes to long-standing U.S. policies on Israel and the Palestinians,47 which Palestinians have criticized as unfairly punitive and biased toward Israel,48 and Jordan has found itself in a difficult political position. While King Abdullah II seeks to maintain strong relations with the United States, the issue of Palestinian rights resonates with much of the Jordanian population; more than half of all Jordanian citizens originate from either the West Bank or the area now comprising the state of Israel. In trying to balance U.S.-Jordanian relations with concern for Palestinian rights, King Abdullah II has refrained from directly criticizing the Trump Administration, while urging the international community to return to the goal of a two-state solution that would ultimately lead to an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.49

U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan

The United States has provided economic and military aid to Jordan since 1951 and 1957, respectively. Total bilateral U.S. aid (overseen by State and the Department ofthe Departments of State and Defense) to Jordan through FY2016FY2017 amounted to approximately $19.220.4 billion. Jordan also has received hundreds of millions in additional military aid since FY2014 channeled through the Defense Department's various security assistance accounts.

Table 1. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Jordan, SFOPS Appropriations: FY2014-FY2019: FY2015-FY2020 Request

current dollars in millions

|

Account |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|

|

|

ESF |

$ |

$ |

$ |

$ |

$1,082.400 |

$910.800 |

|

FMF |

$ |

$ |

$ |

$ |

$425. |

$350.000 |

|

NADR |

$7. |

$ |

$ |

$13.600 |

$13.600 |

— |

|

IMET |

$3. |

$3. |

$3. |

$ |

$4.000 |

$3.800 |

|

Total |

$1, |

$1, |

$ |

$1, |

$1,525.000 |

$1, |

Source: U.S. State Department.

Notes: Funding levels in this table include both enduring (base) and Overseas Contingency Operation (OCO) funds. The Department of Defense also has provided Jordan with military assistance. According to the Department of State, "Jordan is the third largest recipient of FMF funds globally and the single largest recipient of DoD Section 333 funding."

New For FY2019, Congress made available $50 million for Jordan from the Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF).

U.S.-Jordanian Agreement on Foreign Assistance

On February 14, 2018, the United States and JordanU.S.-Jordanian Agreement on Foreign Assistance

Amman, Jordan |

|

|

Source: U.S. State Department. |

On February 14, 2018, then-U.S. Secretary of State Rex W. Tillerson and Jordanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Ayman Safadi signed a new Memorandum of Understanding (or MOU) on U.S. foreign assistance to Jordan (Figure 7). The MOU, the third such agreement between the United and Jordan, commits the United States to provide $1.275 billion per year in bilateral foreign assistance over a five-year period for a total of $6.375 billion (FY2018-FY2022). This latest MOU represents a 27% increase in the U.S. commitment to Jordan above the previous iteration and is the first five-year MOU with the kingdom. The previous two MOU agreements had been in effect for three years. According to the U.S. State Department, the United States is the single largest donor of assistance to Jordan, and the new MOU commits the United States to provide a minimum of $750 million of Economic Support Funds (ESF) and $350 million of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) to Jordan between FY2018 and FY2022.36 In line with the new MOU, for FY2019 President Trump is requesting $1.271 billion for Jordan, including $910.8 million in ESF, $350 million in FMF, and $3.8 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET).

Economic Assistance

The United States provides economic aid to Jordan for (1) budgetary support (cash transfer), (2) USAID programs in Jordan, and (3) loan guarantees. The cash transfer portion of U.S. economic assistance to Jordan is the largest amount of budget support given to any U.S. foreign aid recipient worldwide.50 In November 2018, USAID notified Congress that it intended to obligate a record $745 million in FY2018 ESF (base and OCO) for a cash transfer to Jordan.51 U.S. cash assistance is provided in order to help the kingdom with foreign debt payments, Syrian refugee support, and fuel import costs (Jordan is almost entirely reliant on imports for its domestic energy needs). According to USAID, ESF cash transfer funds are deposited in a single tranche into a U.S.-domiciled interest-bearing account and are not commingled with other funds.52

Source: CRS analysis of USAID Notifications to CongressThe United States provides economic aid to Jordan both as a cash transfer and for USAID programs in Jordan. The Jordanian government uses cash transfers to service its foreign debt. Approximately 40% to 60% of Jordan's ESF allotment may go toward the cash transfer.37 USAID programs in Jordan focus on a variety of sectors including democracy assistance, water preservation

Economic Assistance

USAID programs in Jordan focus on a variety of sectors including democracy assistance, water conservation, and education (particularly building and renovating public schools). In the democracy sector, U.S. assistance has supported capacity-building programs for the parliament's support offices, the Jordanian Judicial Council, the Judicial Institute, and the Ministry of Justice.

The International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute also have received U.S. grants to train, among other groups, the Jordanian Independent Election Commission (IEC), Jordanian political parties, and members of parliament. In the water sector, the bulk of U.S. economic assistance is devoted to optimizing the management of scarce water resources, as. As mentioned above, Jordan is one of the most water-deprived countries in the world. USAID is currently subsidizing53 USAID subsidizes several waste treatment and water distribution projects in the Jordanian cities of Amman, Mafraq, Aqaba, and Irbid. USAID also is helping Jordanian water utilities on advanced leak detection capability.3854

U.S. Sovereign Loan Guarantees (or LGs) allow recipient governments (in this case Jordan) to issue debt securities that are fully guaranteed by the United States government in capital markets,55 effectively subsidizing the cost for governments of accessing financing. Since 2013, Congress has authorized LGs for Jordan and appropriated $413 million in ESF (the "subsidy cost") to support three separate tranches, enabling Jordan to borrow a total of $3.75 billion at concessional lending rates.56

Humanitarian Assistance for Syrian Refugees in Jordan

The U.S. State Department estimates that, since large-scale U.S. aid to Syrian refugees began in FY2012, it has allocated more than $1.13 billion in humanitarian assistance from global accounts for programs in Jordan to meet the needs of Syrian refugees and, indirectly, to ease the burden on Jordan.39 U.S. aid supports refugees living in camps (~141,000) and those living in towns and cities (~500,000).57 According to the State Department, U.S. humanitarian assistance is provided both as cash assistance to refugees and through programs to meet their basic needs, such as child health care, education, water, and sanitation, water, and sanitation.

The U.S. government provides cross-border humanitarian and stabilization assistance to Syrians via programs monitored and implemented through the Embassy Amman-based Southern Syria Assistance Platform. This includes humanitarian assistance to areas of southern and eastern Syria that are otherwise inaccessible, as well as congressionally authorized stabilization and nonlethal assistance to opposition-held areas in southern Syria. According to USAID, U.S. humanitarian assistance funds are enabling UNICEF to provide health assistance for Syrian populationsaround 40,000 Syrians sheltering at the informal Rukban and Hadalat settlements along the Syria-Jordan border berm, including daily water trucking, the rehabilitation of a water borehole, and installation of a water treatment unit in Hadalat.40

Loan Guarantees

The Obama Administration provided three loan guarantees to Jordan, totaling $3.75 billion.41 These include the following:

- In September 2013, the United States announced that it was providing its first-ever loan guarantee to the Kingdom of Jordan. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate up to $120 million in FY2013 ESF-OCO to support a $1.25 billion, seven-year sovereign loan guarantee for Jordan.

- In February 2014, during a visit to the United States by King Abdullah II, the Obama Administration announced that it would offer Jordan an additional five-year, $1 billion loan guarantee. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate $72 million out of the $340 million of FY2014 ESF-OCO for Jordan to support the subsidy costs for the second loan guarantee.

- In June 2015, the Obama Administration provided its third loan guarantee to Jordan of $1.5 billion. USAID notified Congress of its intent to obligate $221 million in FY2015 ESF to support the subsidy costs of the third loan guarantee to Jordan.42

Military Assistance

Foreign Military Financing

U.S.-Jordanian military cooperation is a key component in bilateral relations. U.S. military assistance is primarily directed toward enabling the Jordanian military to procure and maintain conventional weapons systems.43 The United States and Jordan have jointly developed a five-year procurement plan for the Jordanian Armed Forces in order to prioritize Jordan's needs and procurement budget using congressionally appropriated Foreign Military Financing (FMF). FMF grants have enabled the Royal Jordanian Air Force to procure munitions for its F-16 fighter aircraft and a fleet of 28 UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters.44 On February 18, 2016, President Obama signed the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-123), which authorizes expedited review and an increased value threshold for proposed arms sales to Jordan for a period of three years.

Defense Department Assistance

As a result of the Syrian civil war and Operation Inherent Resolve against IS, the United States has increased military aid to Jordan and channeled these increases through Defense Department-managed accounts. Although Jordan still receives the bulk of U.S. military aid from the FMF account, Congress has authorized defense appropriations to strengthen Jordan's border security. Jordan may receive funding from various DOD accounts, such as the following:

- 10 U.S.C. 333—Commonly referred to as DOD's "Global Train and Equip authority." The Secretary of Defense may use this to build the capacity of a foreign country's national security forces for a range of purposes, including counterterrorism, countering weapons of mass destruction, counternarcotics, maritime security, military intelligence, and participation in coalition operations.45

- Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF) (FY2015-FY2016)—Under the FY2015 NDAA (P.L. 113-291) and the defense appropriations measure for the same year (P.L. 113-235), Congress established a DOD Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF), which provided increased funding resources for counterterrorism training and equipment transfers in Africa and the Middle East.46 Section 1534 of FY2015 NDAA stipulated that funds could be transferred to other accounts for use under existing DOD authority established by "any other provision of law." The FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328) expanded and consolidated DOD's "global train and equip" authority, along with various others, under Section 333 of a new Chapter 16 of Title 10, U.S.C (see above). Since then, Congress has not appropriated funds for DOD's CTPF, instead directing funds under DOD's Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account for a range of security cooperation activities.

- Coalition Support Fund (CSF)—CSF authorizes the Secretary of Defense to reimburse key cooperating countries for logistical, military, and other support, including access, to or in connection with U.S. military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria and to assist such nations with U.S.-funded equipment, supplies, and training. CSF is authorized by Section 1233 (FY2008 NDAA, P.L. 110-181), as amended and extended.

- Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF)—The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-328) and The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) created the Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund (CTEF), since renamed the Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund. The CTEF is designed to allow the Secretary of Defense, with the concurrence of the Secretary of State, to transfer funds, equipment, and related capabilities to partner countries in order to counter emergent ISIS threats. The CTEF is the primary account for the Syria and Iraq Train and Equip Programs.47 It replaced the Iraq Train and Equip Fund (ITEF).

- Cooperative Threat Reduction—DOD is authorized, under Chapter 48 of Title 10, U.S.C., to build foreign countries' capacity to prevent nuclear proliferation. Over the past five years, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency has provided training and equipment to border security forces in several Middle Eastern countries under this authority, including Jordan, Iraq, Turkey, and Tunisia.48

Excess Defense Articles

In 1996, the United States granted Jordan Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA) status, a designation that, among other things, makes Jordan eligible to receive excess U.S. defense articles, training, and loans of equipment for cooperative research and development.49 In the last five years, Jordan has received excess U.S. defense articles, including two C-130 aircraft, HAWK MEI-23E missiles, and cargo trucks.

Recent Legislation

P.L. 115-14, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, provided the following for Jordan:

- Appropriates "not less than" $1.525 billion in total U.S. assistance for Jordan, of which "not less than" $1.082 billion is ESF and "not less than" $425 million is FMF;

- Reauthorizes funds from the Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account to "enhance the ability of the armed forces of Jordan to increase or sustain security along its borders";

- Appropriates "up to" $500 million for the Defense Security Cooperation Agency in the Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account to be used to support the armed forces of Jordan and to enhance security along its borders;

- Reauthorizes funds from the Counter-ISIS Train And Equip Fund (CTEF) to enhance the border security of nations adjacent to conflict areas including Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia resulting from actions of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria;

- Reauthorizes ESF to be used to support possible new loan guarantees for Jordan;

- Authorizes ESF to be used to support the creation of an Enterprise Fund in Jordan.

P.L. 115-245, the Department of Defense and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Act, 2019 and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019, provides the following for Jordan:

- Reauthorizes funds from the Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account to "enhance the ability of the armed forces of Jordan to increase or sustain security along its borders";

- Appropriates "up to" $500 million for the Defense Security Cooperation Agency in the Operation and Maintenance, Defense-Wide account to be used to support the armed forces of Jordan and to enhance security along its borders;

- Reauthorizes funds from the Counter-ISIS Train And Equip Fund (CTEF) to enhance the border security of nations adjacent to conflict areas including Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia resulting from actions of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

H.R. 2646, United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Extension Act, would amend the United States-Jordan Defense Cooperation Act of 2015 to extend Jordan's inclusion among the countries eligible for certain streamlined defense sales until December 31, 2022. The bill also would authorize an enterprise fund to provide assistance to Jordan. It was passed in the House on February 5, 2018.

|

Account |

1946-2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

1946-2016 |

|

FMF |

3,380.800 |

300.000 |

284.800 |

300.000 |

385.000 |

450.000 |

5,100.600 |

|

ESF |

6,043.800 |

485.500 |

542.900 |

329.600 |

594.700 |

812.350 |

8,808.850 |

|

INCLE |

3.800 |

1.200 |

— |

0.800 |

0.200 |

— |

6.000 |

|

NADR |

110.600 |

18.400 |

12.200 |

6.100 |

5.400 |

8.850 |

166.300 |

|

IMET |

70.700 |

3.700 |

3.600 |

3.600 |

3.800 |

3.733 |

89.400 |

|

MRA |

82.100 |

35.200 |

167.100 |

157.600 |

162.500 |

tbd |

604.500 |

|

Other |

2,963.500 |

330.100 |

199.400 |

345.700 |

365.400 |

322.930 |

4,527.030 |

|

Total |

12,655.300 |

1,174.100 |

1,210.000 |

1,143.400 |

1,517.000 |

1,597.863 |

19,297.663 |

Source: USAID Overseas Loans and Grants, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2015.

Notes: "Other" accounts include economic and military assistance programs administered by USAID, State, and other federal agencies which are funded at less than $2 million annually. It also includes larger, more recent funding through the International Disaster Assistance account (IDA), Millennium Challenge Account, and several defense department funding accounts. It also encapsulates much larger legacy programs (food aid), some of which have been phased out over time.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Human Rights Watch, Jordan. See https://www.hrw.org/middle-east/n-africa/jordan. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Text of a Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, June 8, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

U.S.-Jordanian military cooperation is a key component in bilateral relations. U.S. military assistance is primarily directed toward enabling the Jordanian military to procure and maintain U.S.-origin conventional weapons systems.58 According to the State Department, Jordan receives one of the largest allocations of International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding worldwide, and IMET graduates in Jordan include "King Abdullah II, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Vice Chairman, the Air Force commander, the Special Forces commander, and numerous other commanders."59 Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and DOD Security AssistanceFMF overseen by the State Department is designed to support the Jordanian armed forces' multiyear (usually five-year) procurement plans, while DOD-administered security assistance supports ad hoc defense systems to respond to immediate threats and other contingencies. FMF may be used to purchase new equipment (e.g., precision-guided munitions, night vision) or to sustain previous acquisitions (e.g., Blackhawk helicopters, AT-802 fixed-wing aircraft). FMF grants have enabled the Royal Jordanian Air Force to procure munitions for its F-16 fighter aircraft and a fleet of 28 UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters.60 As a result of the Syrian civil war and U.S. Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State, the United States has increased military aid to Jordan and channeled these increases through DOD-managed accounts. Although Jordan still receives the bulk of U.S. military aid through the FMF account, Congress has authorized defense appropriations to strengthen Jordan's border security. Since FY2015, total DOD security cooperation funding for Jordan has amounted to $887.7 million.61 Excess Defense ArticlesIn 1996, the United States granted Jordan Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA) status, a designation that, among other things, makes Jordan eligible to receive excess U.S. defense articles, training, and loans of equipment for cooperative research and development.62 In the last five years, excess U.S. defense articles provided to Jordan include two C-130 aircraft, HAWK MEI-23E missiles, and cargo trucks. Table 2. U.S. Foreign Aid Obligations to Jordan: 1946-2017current U.S. Dollars in millions

Source: USAID Overseas Loans and Grants, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2017. Author Contact Information Jeremy M. Sharp, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Footnotes1.

|

|

Human Rights Watch, Jordan. See https://www.hrw.org/middle-east/n-africa/jordan. 2.

|

|

"Jordan faces Wave of Dissent as Government's Troubles Mount, Reuters, November 26, 2018. 3.

|

|

"IMF Staff Reaches Agreement on Policies for the Completion of the Second Review of Jordan's Extended Fund Facility," International Monetary Fund, February 7, 2019. 4.

|

|

"Social Media Use Continues to Rise in Developing Countries but Plateaus Across Developed Ones," Pew Research Center, June 18, 2018. 5.

|

|

Jordan faces Wave of Dissent as Government's Troubles Mount, Reuters, November 26, 2018. 6.

|

|

"Jordan King eats Falafel at Popular Amman Restaurant," Gulf Today, December 22, 2018. 7.

|

|

Over the past year, several prominent Jordanians have publicly criticized the government and the King for failing to tackle corruption. In September 2018, King Abdullah II's half-brother (and former crown prince), Prince Hamzah bin al Hussein criticized the government's response to alleged corruption. See, "Leading Jordanian Royal blasts Kingdom's Corruption Problem," The New Arab, September 26, 2018. In February 2019, one of the leaders of the National Follow-up Committee (a group of former high level officials and retired army officers) Amjad Hazza al Majali, a former royal advisor, circulated a letter to the king online, writing, "We demand that you make practical and effective arrangements to tackle corruption and hunt corrupt individuals, including the corrupt circle that is close to you." See, "Jordanian Politician slams King Abdullah for 'Sponsoring' Corruption," Middle East Eye, February 15, 2019. 8.

|

|

"Jordan to rethink Controversial Cybercrimes Law," Reuters, December 9, 2018. 9.

|

|

"Defusing the Crisis at Jerusalem's Gate of Mercy," International Crisis Group, Briefing 67, April 3, 2019. 10.

|

|

These two Jordanian-leased agricultural territories to Israel are known in Hebrew as Naharayim and Tzofar, where Israeli farmers have tilled the land since 1949. In 1997, three years after the Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty, on the island of Naharayim, a Jordanian soldier killed seven Israeli schoolgirls who were visiting Naharayim on a field trip. The late King Hussein of Jordan visited Israel after the shooting, and Naharayim was renamed the "Isle of Peace" (it is a man-made island in the vicinity of the Jordan River) to commemorate those killed. See, "At Bloodied Isle of Peace, some Israelis still Hope to Bridge Divide with Jordan, Times of Israel, March 13, 2019. 11.

|

|

"King's Termination of Peace Treaty Annexes unites Jordanians," Jordan Times, October 23, 2018. 12.

|

|

For more information on Jerusalem and its holy sites, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti. 13.

|

|

Article 9, Clause 2 of the peace treaty says that "Israel respects the present special role of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Muslim Holy shrines in Jerusalem. When negotiations on the permanent status will take place, Israel will give high priority to the Jordanian historic role in these shrines." In 2013, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) reaffirmed in a bilateral agreement with Jordan that the King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan will continue to serve as the "Custodian of the Holy Sites in Jerusalem," a title that successive Jordanian monarchs have used since 1924. 14.

|

|

"Jerusalem is a Red Line, and all My People are with Me — King," Jordan Times, March 21, 2019. 15.

|

|

"Beware the Mideast's Falling Pillars," New York Times, March 19, 2019. 16.

|

|

"Jordan PM calls for 'Critical' Support from Western and Arab Allies," Financial Times, February 28, 2019. |

Though there was little international recognition of Jordan's annexation of the West Bank, Jordan maintained control of it (including East Jerusalem) until Israel took military control of it during the June 1967 Arab-Israeli War, and maintained its claim to it until relinquishing the claim to the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1988. |

||||||

|

Speculation over the ratio of East Bankers to Palestinians (those who arrived as refugees and immigrants since 1948) in Jordanian society |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In July 2009, King Abdullah II named Prince Hussein (then 15 years old), as crown prince. The position had been vacant since 2004, when King Abdullah II removed the title from his half-brother, Prince Hamzah. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The king also may declare martial law. According to Article 125, "In the event of an emergency of such a serious nature that action under the preceding Article of the present Constitution will be considered insufficient for the defense of the Kingdom, the King may by a Royal Decree, based on a decision of the Council of Ministers, declare martial law in the whole or any part of the Kingdom." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

New amendments to Article 94 in 2011 have put some restrictions on when the executive is allowed to issue temporary laws. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See "Making Our Democratic System Work for All Jordanians," Abdullah II ibn Al Hussein, January 16, 2013, available online at http://kingabdullah.jo/index.php/en_US/pages/view/id/248.html. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"How Jordan's Election Revealed Enduring Weaknesses in Its Political System," Washington Post, October 3, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. |

For example, see Remarks by His Majesty King Abdullah II at the Plenary Session of the 73rd General Assembly of the United Nations, New York, New York, September 25, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Austerity and Fury in Jordan," Economist, June 7, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"IMF Reassures Jordan of Continuing Support," Economist Intelligence Unit, June 13, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Jordan's Solid National Unity is what makes it Special — King," Jordan Times, September 16, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Jordan's Young Protesters say they Learned from Arab Spring Mistakes," Christian Science Monitor, June 5, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Syria approves U.N. Aid Delivery to Remote Camp on Jordan-Syria Border," Reuters, October 17, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

U.S. Central Command, USCENTCOM Statement regarding internally displaced persons (IDPs) at Rukban, Syria, March 7, 2019. 36.

|

|

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, On Behalf of The Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mr. Mark Lowcock, UN OCHA, Director of the Coordination Division, Mr. Ramesh Rajasingham, March 27, 2019. 37.

|

|

38.

|

|

Dr. Steven Gorelick, Cyrus F. Tolman Professor and Senior Fellow, Woods Institute for the Environment - Stanford University, Jordan Water Project, https://pangea.stanford.edu/researchgroups/jordan/. 39.

|

|

USAID, Jordan: Water Resources & Environment, https://www.usaid.gov/jordan/water-and-wastewater-infrastructure. 40.

|

|

On February 26, 2015, Israel and Jordan signed a bilateral agreement ("Seas Canal" Agreement) on the implementation of the Red-Dead Sea Conveyance Project, specifically on the construction of a desalination plant north of Aqaba that would supply water to the Aravah region in Israel and to Aqaba in Jordan. |

For additional background on Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin, see https://fanack.com/jordan/population/. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24. |

For more information on Jerusalem and its holy sites, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

Article 9, Clause 2 of the peace treaty says that "Israel respects the present special role of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Muslim Holy shrines in Jerusalem. When negotiations on the permanent status will take place, Israel will give high priority to the Jordanian historic role in these shrines." In 2013, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) reaffirmed in a bilateral agreement with Jordan that the King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan will continue to serve as the "Custodian of the Holy Sites in Jerusalem," a title that successive Jordanian monarchs have used since 1924. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. |

"King Abdullah of Jordan on Syria, ISIS and Mideast Peace," Fox News, September 26, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. |

Remarks by Vice President Mike Pence and His Majesty King Abdullah II of Jordan, Al Husseiniya Palace, Amman, Jordan, January 22, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

There are ten Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. Throughout the kingdom, UNRWA administers 171 schools and 25 healthy centers. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. |

"Jordan Seeks to Replace Lost Aid," Wall Street Journal, September 20, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31. |

Dr. Steven Gorelick, Cyrus F. Tolman Professor and Senior Fellow, Woods Institute for the Environment - Stanford University, Jordan Water Project, https://pangea.stanford.edu/researchgroups/jordan/. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Donald J. Trump Administration Welcomes Israeli-Palestinian Deal to Implement the Red-Dead Water Agreement, July 13, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Scoop: U.S. Pressing Israel to implement Pipeline Project with Jordan," Axios, July 26, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

45.

"Israel Ready to Build Red Sea-Dead Sea Project with Jordan," Bloomberg, January 2, 2019. |

According to USAID, "Phase 1 includes construction of a seawater desalination plant located in Aqaba, Jordan on the Red Sea, that will produce 65 MCM of water to be shared between Israel and Jordan, and a pipeline to convey approximately 100 MCM of brine mixed with 135 MCM of seawater, to the Dead Sea. Plans include 35 MCM of desalinated water from Aqaba to the Israeli Water Authority to serve populations in southern Israel, and the purchase up to 50 MCM of fresh water from the Sea of Galilee for use in northern Jordan. As part of the regional project, Israel will sell up to 30 MCM of fresh water to the Palestinian Authority for use in the West Bank and Gaza." See, USAID Congressional Notification # 146, Jordan Country Narrative, September 30, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Text of a Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, December 7, 2018. 47.

|

|

For example, see CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti and CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti. 48.

|

|

"For Palestinians, US Embassy move a Show of pro-Israel Bias," Associated Press, May 13, 2018. 49.

|

|

For example, see Remarks by His Majesty King Abdullah II at the Plenary Session of the 73rd General Assembly of the United Nations, New York, New York, September 25, 2018. 50.

|

|

Other budget support aid recipients include: the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau. 51.

|

|

USAID, Congressional Notification, CN #4, November 13, 2018. 52.

|

|

Ibid. 53.

|

|

"Five Countries with the Greatest Water Scarcity Issues," Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, March 31, 2016. 54.

|

|

USAID, "USAID Improves Water Security in Jordan," Office of Press Relations, August 8, 2018. 55.

|

|

"A Helping Hand," International Financial Law Review, April 2014. 56.

|

|

For the latest Loan Guarantee Agreement between the United States and Jordan, see Treaties and other International Acts Series 15-624, Loan Guarantee Agreement between the United States of America and Jordan, Signed at Amman May 31, 2015. 57.

|

|

U.S. Department of State, Fact Sheets: U.S. Humanitarian Assistance in Response to the Syria Crisis, March 14, 2019. 58.

|

|

According to Jane's Defence Procurement Budgets, Jordan's 2019 defense budget is $2.012 billion. See Jane's Defence Budgets, Jordan, February 19, 2019. 59.

|

|

U.S. Department of State, U.S. Security Cooperation with Jordan, Fact Sheet, Bureau Of Political-Military Affairs, October 26, 2018. 60.

|

|

U.S. Department of State, U.S. Security Cooperation with Jordan, Fact Sheet, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, March 23, 2018. 61.

|

|

DOD congressional notifications to Congress. |

U.S. State Department, New U.S.-Jordan Memorandum of Understanding on Bilateral Foreign Assistance to Jordan, Fact Sheet, February 14, 2018. |

|||||||

| 37. |

In 2016, the United States provided $470 million in ESF to Jordan as a cash transfer (59% of the total ESF allocation for Jordan). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38. |

Congressional Notification #53, Country Narrative, Jordan, USAID, February 16, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39. |

U.S. State Department, Fact Sheet: New U.S.-Jordan Memorandum of Understanding on Bilateral Foreign Assistance to Jordan, February 14, 2018. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40. |

USAID, "Syria Complex Emergency - Fact Sheet #4," April 27, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41. |