Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief

Changes from September 10, 2018 to September 17, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief

Contents

Summary

Afghanistan has been a central U.S. foreign policy concern since 2001, when the United States, in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led a military campaign against Al Qaeda and the Taliban government that harbored and supported Al Qaeda. In the intervening 16 years, the United States has suffered more than 2,000 casualties in Afghanistan (including 6 in 2018 thus far) and has spent more than $120 billion for reconstruction there. In that time, an elected Afghan government has replaced the Taliban, and nearly every measure of human development has improved, although future prospects of those measures remain mixed.

While military officials profess greater optimism about the course of the war in early 2018, other policymakers and analysts have described the war against the insurgency (which controls or contests nearly half of the country's territory, by Pentagon estimates) as a stalemate. Furthermore, the Afghan government faces broad public criticism for its ongoing inability to combat corruption, deliver security, alleviate rising ethnic tensions, and develop the economy. Contentious parliamentary and presidential elections, scheduled for October 2018 and April 2019, respectively, may further inflame political tensions. Meanwhile, a series of developments in 2018 may signal greater U.S. urgency to begin peace talks to bring about a negotiated political settlement, the stated goal of U.S. policy.

This report provides an overview of current political and military dynamics, with a focus on the Trump Administration's new strategy for Afghanistan and South Asia, the U.S.-led coalition and Afghan military operations, and recent political developments, including prospects for peace talks and elections. For more detailed background information and analysis on Afghan history and politics, as well as U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, see CRS Report RL30588, Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Overview

The U.S. and Afghan governments, along with partner countries, remain engaged in combat with a resilient Taliban-led insurgency. U.S. military officials increasingly refer to "momentum" against the Taliban,1 however, by some measures insurgents are in control of or contesting more territory today than at any point since 2001.2 The conflict also involves an array of other armed groups, including active affiliates of both Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS, ISIL, or by the Arabic acronym Da'esh). Since early 2015, the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan, known as "Resolute Support Mission" (RSM), has focused on training, advising, and assisting Afghan government forces; combat operations by U.S. counterterrorism forces, along with some partner forces, also continue and have increased since 2017. These two "complementary missions" make up Operation Freedom's Sentinel (OFS).3

The United States has contributed more than $126 billion in various forms of aid to Afghanistan over the past decade and a half, from building up and sustaining the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) to economic development. This assistance has increased Afghan government capacity, but prospects for stability in Afghanistan appear distant. President Donald Trump announced what he termed "a new strategy" for Afghanistan and South Asia in August 2017 that prioritizes "fighting to win," downplays "nation building," and includes a stronger line against Pakistan, a larger role for India, no set timetables, expanded targeting authorities for U.S. forces, and additional troops.4 It is unclear how the strategy has impacted Taliban forces, which have continued to carry out major attacks in Kabul as well as large-scale assaults on urban areas; two provincial centers have been briefly overrun by insurgents in 2018. Efforts by the Afghan government and others to mitigate and eventually end the conflict through peace talks have been complicated by ethnic divisions, political rivalries, and the unsettled military situation, though a series of developments in 2018, including a nationwide ceasefire and reports of direct U.S.-Taliban talks, may portend greater progress on that front.

The Afghan government faces domestic criticism for its failure to guarantee security and prevent insurgent gains, and for internal divisions that have spurred the formation of new political opposition coalitions. In September 2014, the United States brokered a compromise "national unity government" to address the disputed 2014 presidential election, in which both candidates claimed victory, but subsequent parliamentary and district council elections were postponed; after years of delay, they are now scheduled for October 2018. The Afghan government has made some notable progress in reducing corruption and implementing its budgetary commitments, and almost all measures of economic and human development have improved since the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban in 2001. Some U.S. policymakers still hope that the country's largely underdeveloped natural resources and/or geographic position at the crossroads of future global trade routes might improve the economic, and by extension the social and political, life of the country. Nevertheless, Afghanistan's economic and political outlook remains uncertain, if not negative, in light of ongoing hostilities.

Political Situation

The leadership partnership (referred to as the national unity government) brokered in the wake of the disputed 2014 election by the United States between President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Abdullah Abdullah has encountered extensive difficulties but remains intact.5 Outward signs of tensions between the two seem to have receded in the past year, and in September 2017 the U.N.'s Special Representative for Afghanistan described them as having a "good working relationship."6 However, a trend in Afghan society and governance that worries some observers is increasing fragmentation along ethnic and ideological lines.7 Such fractures have long existed in Afghanistan but were relatively muted during Hamid Karzai's presidency.8 These divisions are sometimes seen as a driving force behind some of the political upheavals that have challenged Ghani's government over the past two years.

- Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum, who has criticized Ghani's government for favoring Pashtuns at the expense of the Uzbek minority Dostum claims to represent,9 left Afghanistan for Turkey in May 2017. Dostum's departure came in the wake of accusations that he engineered the kidnapping and assault of a political rival, prompting speculation that his departure was an attempt to avoid facing justice in Afghanistan.10 Dostum returned to Afghanistan in July 2018, quelling protests by his supporters.11

- In May 2017, representatives of several ethnic parties, all of them senior government officials, visited Dostum and announced from Ankara the formation of a new political coalition termed the Coalition for the Salvation of Afghanistan (or Ankara Coalition).12 The group called on President Ghani to implement political reforms and introduce a less-centralized decisionmaking process.13

- Ghani's December 2017 dismissal of Atta Mohammad Noor, the powerful governor of the northern province of Balkh who defied Ghani by remaining in office for several months before resigning in March 2018, may also portend more serious political divisions, possibly along ethnic lines, in 2018.14 Noor is one of the most prominent members of the Jamiat-e-Islami party, which is seen to represent the country's Tajik minority.15

- Leaders of the Ankara Coalition, including Dostum and Noor, launched an electoral alliance called the Grand National Coalition of Afghanistan in July 2018; Karzai also announced his support. One analyst speculates that while the coalition represents a real political threat to Ghani, it is a "divided alliance of historic rivals without a unified vision for Afghanistan's future" and "will likely devolve into disunity."16

After multiple delays, parliamentary and district council elections are currently scheduled for October 20, 2018. In February 2018 testimony, Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan said, "It is vital that parliamentary ... elections take place this year."17 However, in light of the current delay (parliament's mandate expired in June 2015 but was extended indefinitely by a presidential decree due to security concerns), that timeline appears uncertain. Continued contention among electoral commissioners18 and an ethnically motivated dispute over electronic identity cards may further challenge the government's ability to hold elections this year.19 Security concerns persist as well: insurgent attacks have targeted a number of voter registration centers and Afghan officials report that nearly 1,000 of 7,400 polling stations are in areas outside of the government's control.20 Some observers have called for district council elections to be delayed further and held alongside the 2019 presidential election, arguing that holding them before settling broader questions of local governance and autonomy "risks perpetuating the long-standing fallacy in Afghan statebuilding: if subnational structures are built on paper, state legitimacy will follow."21 Others, anticipating election-related instability or even violence, have proposed postponing all currently scheduled elections in favor of a wholesale reworking of the Afghan political system to make it less centralized.22

Reconciliation Efforts and Obstacles

For years, the U.S. and Afghan governments and various neighboring states have engaged in efforts to bring about a political settlement with insurgents.23 Because of many insurgents' views, a settlement is likely to require difficult political compromises on issues such as women's rights or the Afghan constitution.24 The Obama Administration backed reconciliation with the stipulation that any settlement be Afghan-led and require insurgent leaders to (1) cease fighting, (2) accept the Afghan constitution, and (3) sever any ties to Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.25 In his August 2017 speech laying out a new strategy for Afghanistan (more below), President Trump referred to a "political settlement" as an outcome of an "effective military effort," but did not elaborate on what U.S. goals or conditions might be as part of this putative political process.

In 2018, a number of developments indicate potential progress toward peace talks. In February 2018, President Ghani offered direct talks with the Taliban "without preconditions" and proposed confidence-building measures such as prisoner exchanges.26 The Taliban effectively rejected that offer (as it has rejected similar overtures from Kabul in the past) with the announcement of its spring offensive on April 25, 2018. Ghani followed up on his offer for talks without preconditions by declaring, in June 2018, a unilateral, nationwide ceasefire. The Taliban reciprocated, leading to a three day ceasefire during which Taliban fighters and Afghan forces socialized, prayed together, and visited areas controlled by the other.27 A grassroots, nationwide series of peace marches and demonstrations also demonstrated popular support for a cessation of hostilities.28 However, a second, conditional three-month ceasefire offered by the Afghan government in August 2018 seems to have failed to materialize, given continued fighting. One analyst, citing Taliban sources, suggests that the Taliban assault on Ghazni (more below) may have been intended to "push back against any impression that U.S. military action was forcing [the Taliban] into negotiations."29

While the Taliban have long expressed a willingness to negotiate directly with the United States,30 the official U.S. position for years has been that the Taliban can only negotiate with the Afghan government in an "Afghan-led, Afghan-owned" process.31 U.S. officials have indicated that dialogue between Taliban figures and Kabul representatives "is occurring off the stage."32 It is unclear how receptive the Taliban, or elements thereof, might be to such negotiations.33 However, reports in July 2018 indicate that the Trump Administration is contemplating authorizing direct U.S.-Taliban talks, or may have done so, with some Taliban figures stating that preliminary interactions have already taken place.34 In September 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo named former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad as a "special advisor" to serve as "the State Department's lead person" for reconciliation efforts.35 Some have questioned the appointment, citing Khalilzad's views on Pakistan.36

Military and Security Situation

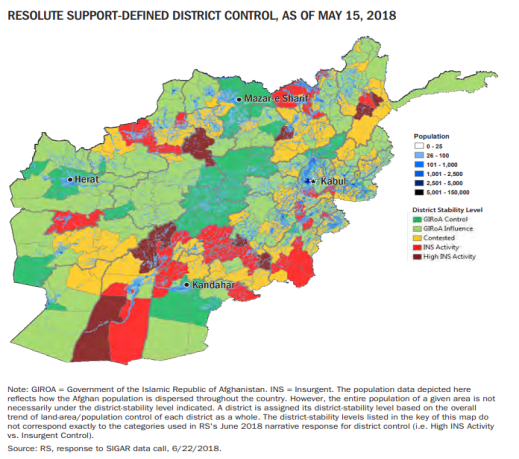

In early 2018, "Afghanistan has become CENTCOM's main effort" as U.S. operations in Iraq and Syria wind down.37 While U.S. commanders have asserted that the ANDSF performs well despite taking heavy casualties, insurgent forces retain, and by some measures are increasing, their ability to contest and hold territory and to launch high profile attacks. The Taliban has made gains throughout the south, which is considered to be the group's stronghold, while showing signs of strength even outside their traditional bases of operations (see Figure 1). U.S. officials have often emphasized the Taliban's failure to capture a provincial capital since their week-long seizure of Kunduz city in northern Afghanistan in September 2015, but two, Farah and Ghazni, have been briefly overrun in 2018 so far (in May and August, respectively). Secretary of Defense James Mattis described the Taliban assault on Ghazni, which left hundreds dead, as a failure, saying "every time they take something…they're unable to hold it."38

General John Nicholson, the former U.S. commander in Afghanistan who was replaced by General Austin Miller in August 2018, said at his final press briefing that month that "the strategy is working, "" citing "progress toward reconciliation,"39 echoing encouraging assessments from other U.S. officials, who cite the new strategy to justify their optimism.40 Outside assessments are generally more negative; in February 2018, former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel called the situation in Afghanistan "worse than it's ever been."41 Others question the very rationale of continued American military engagement; Karl Eikenbery, who served as the commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan and later as U.S. ambassador, said in August 2018 that "we continue to fight simply because we are there."42

|

|

Source: SIGAR July 30, 2018, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress. |

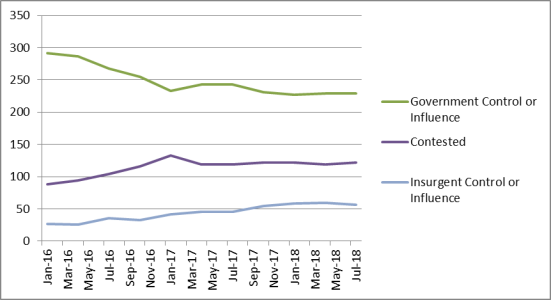

Arguably complicating assessments that the situation in Afghanistan is a stalemate or improving, the extent of territory controlled or contested by the Taliban has steadily grown in recent years by most measures (see Figure 2). In its July 30, 2018, report, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) reported that the share of districts under government control or influence is 56%, with 14% under insurgent control or influence, and the remaining 30% contested; those figures are unchanged from the past two SIGAR quarterly reports.43

While the Taliban retain the ability to conduct high profile urban attacks (including a string of such assaults in early 2018),44 they also demonstrate considerable tactical capabilities.45 Due to the high levels of casualties inflicted by the Taliban, the Trump Administration has reportedly urged Afghan forces to pull out of some isolated outposts and rural areas in a strategy that resembles approaches taken by prior Administrations.46 The May 2016 killing of then-Taliban head Mullah Mansour by a U.S. strike demonstrated Taliban vulnerabilities to U.S. intelligence and combat capabilities, although it did not have a measurable effect on Taliban effectiveness; it is unclear to what extent current leader Haibatullah Akhundzada exercises effective control over the group and how he is viewed within its ranks.47 Overall, the amount of U.S. munitions used in Afghanistan has increased, with 4,361 weapons released in 2017 (up from 1,337 in 2016), the highest annual figure since 2011; 2018 is on track to surpass 2017 by a considerable margin.48

|

|

Source: SIGAR Quarterly Reports. Notes: The y-axis represents the number of districts, of which the U.S. government counts 407 in Afghanistan. |

A significant share of U.S. operations are aimed at the local IS affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, also known as ISIS-K). This group appears to be a growing factor in U.S. and Afghan strategic planning, although there is debate over the degree of threat the group poses.49 ISKP and Taliban forces have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences.50 In April 2018, a U.S. airstrike killed the ISKP leader (himself a former Taliban commander) in northern Jowzjan province, which NATO described as "the main conduit for external support and foreign fighters from Central Asian states into Afghanistan."51 American officials are reportedly tracking attempts by IS fighters to enter Afghanistan and use Afghan territory as a base from which to plan and conduct international operations.52 ISKP has also claimed responsibility for a number of large-scale attacks, including multiple bombings targeting Afghanistan's Shiite minority.

ANDSF Development and Deployment

The effectiveness of the ANDSF is key to the security of Afghanistan. As of June 2018, SIGAR reports that Congress has appropriated at least $72.8 billion for Afghan security forces since 2002. Since 2014, the United States generally has provided around 75% of the estimated $5 billion a year to fund the ANDSF, with the balance coming from U.S. partners ($1 billion annually) and the Afghan government ($500 million). The FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) conference report authorizes and the FY2018 defense appropriation provides the Administration's request of $4.9 billion for the ANDSF. The Administration's FY2019 request seeks $5.2 billion for the ANDSF, and the House- and Senate-passed versions of the FY2019 NDAA (H.R. 5515) would authorize the appropriation of the requested amount.

Major concerns about the ANDSF raised by SIGAR, DOD, and others include

- absenteeism and the fact that about 35% of the force does not reenlist each year, and that the rapid recruitment might dilute the force's quality;53

- widespread illiteracy within the force;54

- credible allegations of child sexual abuse and other potential human rights abuses;55 and

- casualty rates often described as unsustainable, including over 6,700 combat deaths in 2016 (up from 5,500 the previous year) and "about 10,000" in 2017.56

Key metrics related to ANDSF performance, such as casualties, attrition rates, and personnel strength, were classified by U.S. Forces-Afghanistan (USFOR-A) in response to a request from the Afghan government starting with the October 2017 SIGAR quarterly report and remain withheld; SIGAR previously published those metrics as part of its quarterly reports.57

Components of the ANDSF include the following:

The Afghan National Army (ANA). Of its authorized size of 227,000, the ANA (all components) has about 196,000 personnel, an actual reduction of over 8,000 since May 2017. Its special operations component, trained by U.S. Special Operations Forces, numbers nearly 20,000, and is used extensively to reverse Taliban gains: their efforts reportedly make up 70%-80% of the fighting.58

Afghan Air Force (AAF). Afghanistan's Air Force is a key focus of U.S. advisory and support operations. Since FY2010, the United States has appropriated approximately $6.4 billion for the AAF, resulting in some "notable accomplishments."59 It has been mostly a support force but, since 2014, has progressively increased its bombing operations in support of coalition ground forces. As AAF capabilities have grown, "so have concerns over disregard for civilians in harm's way;" dozens of civilians may have been killed in an April 2018 Afghan aerial operation in Kunduz province.60

|

The current train, advise, and assist mission in Afghanistan, Resolute Support Mission (RSM), is led by NATO, and NATO partners have been heavily engaged in Afghanistan since 2001. At its height in 2012, the number of NATO and non-NATO partner forces in Afghanistan reached 130,000, around 100,000 of whom were American. As of September 2018, RSM is made up of around 16,000 troops from 39 countries, of whom 8,475 are American. This represents an increase of about 3,000 troops from NATO and other partner countries. At the NATO summit in July 2018, NATO leaders extended their financial commitment to Afghan forces to 2024 (previously 2020).61 |

Afghan National Police (ANP). U.S. and Afghan officials believe that a credible and capable national police force is critical to combating the insurgency. However, many assessments of the ANP are negative. A 2017 SIGAR report asserted that after years of disagreements between the United States and European partners over the role and mission of the force, "tension over the purpose of the ANP and the role of the advisory mission remain today," with the ANP losing around a quarter of the force annually due to heavy casualties, morale issues, and attrition.62

U.S. Troop Levels and Authorities

At a February 2017 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, General Nicholson indicated that the United States had a "shortfall of a few thousand" troops that, if filled, could help break the "stalemate."63 A subsequent National Security Council-led review of U.S. strategy that included plans for more troops was reportedly held up due to disagreements within the Administration.64

In June 2017, President Trump delegated to Secretary Mattis the authority to set force levels, reportedly limited to around 3,500 additional troops, in June 2017; Secretary Mattis signed orders to deploy them in September 2017.65 Those additional forces (all of which are dedicated to RSM) have arrived in Afghanistan, putting the total number of U.S. troops in the country at around 14,000.66

Beyond additional troops, U.S. forces now have broader authority to operate independently of Afghan forces and "attack the enemy across the breadth and depth of the battle space," expanding the list of targets to include those related to "revenue streams, support infrastructure, training bases, infiltration lanes."67 This has been demonstrated in a series of operations, beginning in the fall of 2017, against Taliban drug labs. These operations, often highlighted by U.S. and Afghan officials, seek to degrade what is widely viewed as one of the Taliban's most important sources of revenue, namely the cultivation, production, and trafficking of narcotics.68 Some have questioned the impact of these strikes, especially in the context of the United States' overall counternarcotics strategy.69 In November 2017, the United Nations reported that the total area used for poppy cultivation in 2017 reached an all-time high of 328,000 hectares, an increase of 63% from 2016 and 46% higher than the previous record in 2014; similarly, opium production increased by 87%.70

|

New U.S. Strategy In a national address on August 21, 2017, President Trump announced a "new strategy" for Afghanistan and South Asia that includes several pillars:

Despite widespread expectations that he would discuss prospects for the deployment of additional troops, President Trump stated "we will not talk about numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities."71 Criticizing the previous Administration's use of "arbitrary timetables," the President did not specify what conditions on the ground might necessitate or allow for alterations to the strategy going forward. Some have characterized the strategy as "short on details" and serving "only to perpetuate a dangerous status quo."72 Others welcomed the strategy, contrasting it favorably with proposed alternatives such as a full withdrawal of U.S. forces (which President Trump conceded was his "original instinct") or heavy reliance on contractors.73 |

Pakistan and Other Neighbors

The United States has encouraged Afghanistan's neighbors to support a stable and economically viable Afghanistan. The neighbor considered most crucial to Afghanistan's security is Pakistan. President Trump has directly accused Pakistan of "housing the very terrorists that we are fighting."74 Afghan leaders, along with U.S. military commanders, attribute much of the insurgency's power and longevity either directly or indirectly to Pakistan; President Ghani said in June 2017 that Pakistan was waging an "undeclared war of aggression" on his country.75 Experts debate the extent to which Pakistan is committed to Afghan stability or is attempting to exert control in Afghanistan through ties to insurgent groups, most notably the Haqqani Network, which is an official, semiautonomous component of the Taliban.76 DOD reports on Afghan stability have repeatedly identified militant safe havens in Pakistan as a threat to security in Afghanistan, though some question the validity of that charge in light of the Taliban's increased territorial control within Afghanistan itself.77

Pakistan sees Afghanistan as potentially providing strategic depth against India.78 Pakistan may also view a weak and destabilized Afghanistan as preferable to a strong, unified Afghan state (particularly one led by a Pashtun-dominated government in Kabul). However, at least some Pakistani leaders have stated that instability in Afghanistan could rebound to Pakistan's detriment; Pakistan has struggled with indigenous Islamist militants of its own.79 Pakistan may also anticipate that improved relations with Afghanistan's leadership could limit India's influence in Afghanistan.

About 2 million Afghan refugees have returned from Pakistan since 2001, but approximately 2.4 million more remain in Pakistan and Pakistan is pressing many of them to return; the forced return of several hundred thousand since 2016 may raise questions under international law and exacerbate humanitarian problems in Afghanistan.80 Afghanistan-Pakistan relations are further complicated by a long-standing border dispute over which violence has broken out on several occasions (Kabul does not accept the 1893 "Durand Line" as a legitimate international border).

Afghanistan largely maintains cordial ties with its other neighbors, including the post-Soviet states of Central Asia, though some warn that rising instability in Afghanistan may complicate those relations.81 In the past year, multiple U.S. commanders have warned of increased levels of assistance, and perhaps even material support, for the Taliban from Russia and Iran, both of which cite IS presence in Afghanistan to justify their activities.82 Both nations were opposed to the Taliban government of the late 1990s, but reportedly see the Taliban as a useful point of leverage vis-a-vis the United States. Afghanistan may also represent a growing priority for China in the context of broader Chinese aspirations in Asia and globally.83

Revised Regional Approach

In his August 2017 speech, President Trump identified a new approach to Pakistan, saying "We can no longer be silent about Pakistan's safe havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban, and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond."84 In the same speech, President Trump praised Pakistan as a "valued partner," citing the close U.S.-Pakistani military relationship. However, the Trump Administration announced in January 2018 plans to suspend security assistance to Pakistan in a decision that could impact hundreds of millions of dollars in aid.85 That and similar moves could provoke retaliatory measures from Pakistan, including the closure of air and ground supply routes used to supply U.S. and coalition forces, though no such actions have been taken to date.86 In February 2018, CENTCOM Commander General Joseph Votel stated, "Recently we have started to see an increase in communication, information sharing, and actions on the ground," but that these "positive indicators" have "not yet translated into the definitive actions we require Pakistan to take against Afghan Taliban or Haqqani leaders."87

In his speech, President Trump also encouraged India to play a greater role in Afghan economic development; this, along with other Administration messaging, has compounded Pakistani concerns over Indian activity in Afghanistan.88 India has been the largest regional contributor to Afghan reconstruction, but New Delhi has not shown an inclination to pursue a deeper defense relationship with Kabul. Afghans themselves may be divided on the wisdom of cultivating stronger ties with India.89 Neither Iran nor Russia was mentioned in the President's speech, and it is unclear how, if at all, the U.S. approach to them might hashave changed as part of the new strategy.

Economy and U.S. Aid

Economic development is pivotal to Afghanistan's long-term stability, though indicators of future growth are mixed. Decades of war have stunted the development of most domestic industries, including mining.90 The economy has also been hurt by a steep decrease in the amount of aid provided by international donors. Afghanistan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown an average of 7% per year since 2003, but growth slowed to 2% in 2013 while aid cutbacks and political uncertainty about the post-2014 security situation caused a further reduction in growth to between 1% and 2% 2014-2017, with a slight recovery forecast for 2018.91 Social conditions in Afghanistan remain equally mixed. On issues ranging from human trafficking92 to religious freedom to women's rights, Afghanistan has, by all accounts, made significant progress since 2001, but future prospects in these areas remain uncertain.

Congress has appropriated more than $126 billion in aid for Afghanistan since FY2002, with about 62% for security and 28% for development (and the remainder for civilian operations, mostly budgetary assistance, and humanitarian aid).93 President Trump's FY2019 budget requests $5.2 billion for the ANDSF, $500 million in Economic Support Funds, and smaller amounts to help the Afghan government with tasks like combatting narcotics trafficking. This is roughly even with the overall FY2017 enacted level of about $5.6 billion (down from nearly $17 billion in FY2010). These figures do not include the cost of U.S. combat operations (including related regional support activities), which was estimated at a total of $752 billion since FY2001 in a July 2017 DOD report, with approximately $45 billion requested for each of FY2018 and FY2019.94

Outlook

Given the continued battlefield stalemate, and the Trump Administration's mostly military-focused strategy intended to reverse it, many view the termination of the conflict as the most important determinant of Afghanistan's future and the success of U.S. efforts there. Meanwhile, continued Taliban attacks throw the security challenge into sharp relief, and insurgent and terrorist groups may make further gains in 2018.95 Hopes for a negotiated settlement have risen considerably in mid-2018, inspired by such events as the June 2018 nationwide ceasefire and reports of a reversal of U.S. policy on direct U.S.-Taliban talks. These developments have not yet produced any meaningful progress toward a settlement. Moreover, political dynamics, particularly the increasing willingness of political actors to directly challenge the legitimacy and authority of the central government, even by extralegal means, may pose an even more serious threat to Afghan stability in 2018 and beyond.

After nearly 17 years of war, Members of Congress and other U.S. policymakers may seek to challenge or broaden their conceptions of what "victory" in Afghanistan looks like, examining the array of potential outcomes, how these outcomes might harm or benefit U.S. interests, and what the relative levels of U.S. engagement and investment required to attain them are.96 U.S. policymakers seek to bring insurgents to the negotiating table by achieving an insurmountable advantage on the battlefield through increased U.S. military activity and by capitalizing on the enhanced capacity of the ANDSF. At the same time, they may also examine how the United States can leverage its assets, influence, and experience in Afghanistan, as well as those of Afghanistan's neighbors and international organizations, to encourage and perhaps incentivize more equal and inclusive service delivery and governance.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, for example, Lolita Baldor, "Gen. Joseph Dunford: There are signs of progress in Afghan war," Associated Press, March 25, 2018. |

| 2. |

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, October 30, 2017. |

| 3. |

"Operation Freedom's Sentinel, Quarterly Report to Congress, Jan. 1 to Mar. 31, 2018," Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations, May 21, 2018. |

| 4. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia, August 21, 2017. |

| 5. |

See, for example, Mujib Mashal, "Afghan Chief Executive Abdullah Denounces President Ghani as Unfit for Office," New York Times, August 11, 2016. |

| 6. |

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, Briefing to the United Nations Security Council by the Secretary-General's Special Representative for Afghanistan, Mr. Tadamichi Yamamoto, September 25, 2017. |

| 7. |

Frud Bezhan, "Leaked Memo Fuels New Allegations Of Ethnic Bias In Afghan Government," RFERL, November 20, 2017. |

| 8. |

See, for example, Azam Ahmed and Habib Zahori, "Afghan Ethnic Tensions Rise in Media and Politics," New York Times, February 18, 2014. |

| 9. |

"Afghan leaders trade barbs as government splits widen," Reuters, October 25, 2016. |

| 10. |

"Afghan Vice-President Dostum flies to Turkey amid torture claims," BBC, May 20, 2017. Several of Dostum's bodyguards were sentenced to five years in jail in November 2017 for their involvement in the incident. |

| 11. |

"DOSTUM RETURNS: VP calls on north to cease protests," Afghanistan Times, July 23, 2018. |

| 12. |

The group is made up of Dostum's Uzbek Junbish-e-Milli; the Tajik Jamiat-e-Islami (led by Foreign Minister Salahuddin Rabbani); and the Hazara Hizb-e-Wahdat-e-Islami. |

| 13. |

Pamela Constable, "Political storm brews in Afghanistan as officials from ethnic minorities break with president, call for reforms and protests," Washington Post, July 1, 2017. |

| 14. |

James Mackenzie and Matin Sahak, "Stand-off over powerful Afghan governor foreshadows bitter election fight," Reuters, January 7, 2018; "Powerful Afghan Governor Resigns, Ending Standoff With Ghani," Radio Free Europe, March 22, 2018. |

| 15. |

"Powerful Afghan regional leader ousted as political picture clouds," Reuters, December 18, 2017. |

| 16. |

Scott DesMarais, "Afghan Government on Shaky Ground Ahead of Elections," Institute for the Study of War, July 31, 2018. |

| 17. |

Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan Testimony on the Administration's South Asia Strategy on Afghanistan, U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, February 6, 2018. |

| 18. |

Ali Yawar Adili, "Afghanistan Election Conundrum (1): Political pressure on commissioners puts 2018 vote in doubt." Afghanistan Analysts Network, November 18, 2017. |

| 19. |

Hamid Shalizi, "Who is an Afghan? Row over ID cards fuels ethnic tension," Reuters, February 8, 2018. |

| 20. |

"Afghanistan: Kabul voter centre suicide attack kills 57," BBC, April 22, 2018; Azizullah Hamdard, "Nearly 950 polling stations out of govt's control," Pajhwok, March 25, 2018. |

| 21. |

Frances Z. Brown, "Local Governance Reform in Afghanistan and the 2018 Elections," U.S. Institute of Peace, November 9, 2017. |

| 22. |

See, for example, Abdul Waheed Ahmad, "A Weak State, But a Strong Society in Afghanistan," War on the Rocks, February 27, 2018; Haroun Mir, "Should Afghanistan postpone presidential election?" Asia Times, June 6, 2018. |

| 23. |

In 2011, U.S. diplomats held their first meetings with Taliban officials of the post-2001 period, and subsequent U.S.-Taliban meetings led to the 2014 release of U.S. prisoner of war Bowe Bergdahl in exchange for the release to Qatar of five senior Taliban captives from the Guantanamo detention facility. An agreement to reopen the Taliban office in Qatar (first opened in June 2013 and closed shortly thereafter under U.S. pressure) also was reached in 2014, and that office remains the Taliban's sole official representation. |

| 24. |

The 2016 reconciliation with the government of one insurgent faction, Hizb-e-Islami-Gulbuddin (HIG), led by former mujahedin party leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, is seen by some as a possible template for further work toward a political settlement. Hekmatyar, who is held responsible for a number of potential war crimes during Afghanistan's post-1992 civil war, periodically allied with the Taliban after 2002 and carried out a number of deadly attacks on U.S. and Afghan forces. After months of negotiations, a reconciliation agreement was signed between Afghan officials and Hekmatyar representatives on September 22, 2016. In May 2017, Hekmatyar returned to Kabul, rallying thousands of supporters at a speech in which he criticized the NUG, leading to concerns about whether he would play a constructive role in Afghan politics; he has since continued that criticism while calling on the Taliban to negotiate. Andrew E. Kramer, "Once-Feared Afghan Warlord Is Still Causing Trouble, but Talking Peace," New York Times, March 4, 2018. |

| 25. |

Steve Coll, Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan (Random House, 2018), pp. 447-448. |

| 26. |

Hamid Shalizi and James Mackenzie, "Afghanistan's Ghani offers talks with Taliban 'without preconditions,'" Reuters, February 28, 2018. |

| 27. |

"Taliban and Security Forces Celebrate Eid Together," Tolo News, June 16, 2018. |

| 28. |

Ali Mohammed Sabawoon, "Going Nationwide: The Helmand peace march initiative," Afghanistan Analysts Network, April 23, 2018. |

| 29. |

Borhan Osman, "As New U.S. Envoy Appointed, Turbulent Afghanistan's Hopes of Peace Persist," International Crisis Group, September 5, 2018. |

| 30. |

Pamela Constable, "Taliban appeals to American people to 'rationally' rethink war effort," Washington Post, February 14, 2018; Ayaz Gul, "Taliban Categorically Rejects Peace Talks With Afghan Government," Voice of America, May 16, 2017. |

| 31. |

See, for example, Rebecca Kheel, "Tillerson sees place for Taliban in Afghan government," The Hill, October 23, 2017. |

| 32. |

Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via Teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan, May 30, 2018. |

| 33. |

Borhan Osman, "A Negotiated End to the Afghan Conflict," United States Institute of Peace, June 18, 2018. |

| 34. |

Mujib Mashal and Eric Schmitt, "White House Orders Direct Taliban Talks to Jump-Start Afghan Negotiations," New York Times, July 15, 2018; "Taliban sources confirm Qatar meeting with senior US diplomat," BBC, July 30, 2018. For more, see CRS Insight IN10935, Momentum Toward Peace Talks in Afghanistan?, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 35. |

Michele Kelemen, "Zalmay Khalilzad Appointed As U.S. Special Advisor To Afghanistan," NPR, September 5, 2018. |

| 36. |

Kathy Gannon, "New US adviser to Afghanistan raises hackles in region," Associated Press, September 5, 2018. |

| 37. |

Department of Defense Press Briefing By Major General Hecker via Teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan, February 7, 2018. |

| 38. |

Media Availability with Secretary Mattis en route to Bogota, Colombia, Department of Defense, August 16, 2018; W.J. Hennigan, "Exclusive: Inside the U.S. Fight to Save Ghazni From the Taliban," Time, August 23, 2018. |

| 39. |

Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan, August 22, 2018. |

| 40. |

Jim Garamone, "Dunford Encouraged by Afghan, Coalition Efforts in Afghanistan," DoD News, March 23, 2018. |

| 41. |

Aaron Mehta, "Interview: Former Pentagon chief Chuck Hagel on Trump, Syria and NKorea," Defense News, February 3, 2018. |

| 42. |

Quoted in Mujib Mashal, "'Time for This War in Afghanistan to End,' Says Departing U.S. Commander," New York Times, September 2, 2018. |

| 43. |

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, July 30, 2018. |

| 44. |

Max Fisher, "Why Attack Afghan Civilians? Creating Chaos Rewards Taliban," New York Times, January 28, 2018. |

| 45. |

Alec Worsnop, "From Guerilla to Maneuver Warfare: A Look at the Taliban's Growing Combat Capability," Modern War Institute, June 6, 2018. |

| 46. |

Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Helene Cooper, "Newest U.S. Strategy in Afghanistan Mirrors Past Plans for Retreat," New York Times, July 28, 2018. |

| 47. |

For evidence of division and discontent within the Taliban, see Theo Farrell and Michael Semple, "Ready for Peace? The Afghan Taliban after a Decade of War," Royal United Services Institute, January 2017. |

| 48. |

AFCENT Airpower Summary, July 31, 2018. |

| 49. |

See, for example, Kyle Rempfer, "Is ISIS gaining 'serious' ground in Afghanistan? Russia says yes. The US says no," Military Times, March 26, 2018. According to media accounts, of the 14 U.S. battlefield casualties in 2017, as many as 9 were killed in anti-ISKP operations, along with at least 2 CIA personnel. Thomas Gibbons-Neff, "Pentagon identifies Special Forces soldier killed battling Islamic State in Afghanistan," Washington Post, August 18, 2017; Adam Goldman and Matthew Rosenberg, "A Funeral of 2 Friends: C.I.A. Deaths Rise in Secret Afghan War," New York Times, September 6, 2017. |

| 50. |

See, for example, Amira Jadoon, et al., "Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties," CTC Sentinel, Vol. 11, Issue 4, April 26, 2018; Najim Rahim and Rod Nordland, "Taliban Surge Routs ISIS in Northern Afghanistan," New York Times, August 1 2018. |

| 51. |

NATO Resolute Support Media Center, "Top IS-K commander killed in northern Afghanistan," April 9, 2018. |

| 52. |

Helene Cooper, "U.S. Braces for Return of Terrorist Safe Havens to Afghanistan," New York Times, March 12, 2018. |

| 53. |

Additionally, an October 2017 SIGAR report revealed that nearly half of all foreign military trainees that went absent without leave (AWOL) while in U.S.-based training (152 of 320). Those 152 AWOL Afghan trainees make up around 6% of the 2,537 Afghans who came to the United States for training between 2005 and 2017, compared with just .07% of trainees from other countries. SIGAR-18-03-SP, "U.S.-Based Training for Afghanistan Security Personnel: Trainees Who Go Absent Without Leave Hurt Readiness and Morale, And May Create Security Risks," October 17, 2017. |

| 54. |

Most estimates put the rate of illiteracy within the ANDSF at over 60%, but reliable figures may not exist. SIGAR reported in January 2014 that means of measuring the effectiveness of ANDSF literacy programs were "limited," and that judgment seems not to have changed in the years since. That SIGAR report described the stated goal of 100% proficiency at a first grade level and 50% proficiency at a third grade level as "unattainable" and "unrealistic." A follow up report at the end of 2014 reiterated concerns about the availability and reliability of literacy data, saying that "no one appeared to know the overall literacy rate of the [ANDSF]." |

| 55. |

See SIGAR Report 17-47, "Child Sexual Assault in Afghanistan: Implementation of the Leahy Laws and Reports of Assault by Afghan Security Forces," June 2017 (released on January 23, 2018). |

| 56. |

Mashal and Sukhanyar, op. cit. |

| 57. |

Shawn Snow, "Report: US officials classify crucial metrics on Afghan casualties, readiness," Military Times, October 30, 2017. |

| 58. |

Helene Cooper, "Afghan Forces Are Praised, Despite Still Relying Heavily on U.S. Help," New York Times, August 20, 2017. |

| 59. |

Inspector General, U.S. Department of Defense, "Progress of U.S. and Coalition Efforts to Train, Advise, and Assist the Afghan Air Force," January 4, 2018. The United States is slated to procure around 30 Black Hawks for the AAF by the end of 2018 as part of a plan to replace the current Afghan fleet of 46 Russian-origin Mi-17s with 159 Black Hawks by 2023. Rahim Faiez, "Afghans soon to fly missions with Black Hawks from US," Associated Press, March 26, 2018. |

| 60. |

Najim Rahim and Mujib Mashal, "Afghan Leaders Admit Civilians Were Killed in Anti-Taliban Bombing," New York Times, April 3, 2018. |

| 61. |

Brussels Summit Declaration, issued July 11, 2018. |

| 62. |

"Reconstructing the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: Lessons From the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan," Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, September 23, 2017. |

| 63. |

Statement for the record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander, U.S. Forces – Afghanistan before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan, February 9, 2017. |

| 64. |

Susan Glasser, "The Trump White House's War Within," Politico, July 24, 2017. Some participants reportedly expressed skepticism that a few thousand more troops could meaningfully impact dynamics on the ground, pointing to previous "surges" that did not do so, and raised concerns about an open-ended U.S. commitment in a country where U.S. troops have already been deployed for nearly two decades. Others countered that the relative cost of the U.S. commitment in Afghanistan is a worthy investment when viewed against the cost of a terrorist attack the absence of U.S. forces might allow, comparing it to "term-life insurance." Asawin Suebsaeng and Spencer Ackerman, "$700 Billion and 16 Years at War Is a 'Modest Amount,' U.S. Officers Say," Daily Beast, July 24, 2017. |

| 65. |

Tara Copp, "Mattis signs orders to send about 3,500 more US troops to Afghanistan," Military Times, September 11, 2017. |

| 66. |

Dan Lamothe, "Trump added troops in Afghanistan. But NATO is still short of meeting its goal," Washington Post, November 9, 2017. As of September 30, 2017, the total number of active duty and reserve forces in Afghanistan was 15,298. Defense Manpower Data Center, Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country Quarterly Report, September 2017. |

| 67. |

Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan, November 20, 2017. |

| 68. |

Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan estimated in a February 6, 2018, Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing that 65% of Taliban revenues are derived from narcotics. |

| 69. |

Kyle Rempfer, "Doubts rise over effectiveness of bombing Afghan drug labs," Military Times, February 5, 2018. |

| 70. |

"Afghanistan Opium Survey 2017," United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, November 15, 2017. |

| 71. |

For more on the debate around the merits of revealing troop levels, see Jon Donnelly, "Analysis: Why Won't Trump Discuss Troop Numbers?" CQ News, August 23, 2017. |

| 72. |

Rebecca Kheel, "Dems: Trump 'has no strategy" for Afghanistan," The Hill, August 21, 2017. |

| 73. |

Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, "'It's a hard problem': Inside Trump's decision to send more troops to Afghanistan," Washington Post, August 21, 2017. |

| 74. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia, August 21, 2017. |

| 75. |

Eltaf Najafizada and Chris Kay, "Ghani Says Afghanistan Hit by 'Undeclared War' From Pakistan," Bloomberg, June 6, 2017. |

| 76. |

For more, see CRS In Focus IF10604, Al Qaeda and Islamic State Affiliates in Afghanistan, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 77. |

Author interviews with Pakistani military officials, Islamabad, Pakistan, February 21, 2018. |

| 78. |

Larry Hanauer and Peter Chalk, "India's and Pakistan's Strategies in Afghanistan: Implications for the United States and the Region," RAND Center for Asia Pacific Policy, 2012. |

| 79. |

Jon Boone, "Musharraf: Pakistan and India's backing for 'proxies' in Afghanistan must stop," Guardian, February 13, 2015; author interviews with Pakistani military officials, Islamabad, Pakistan, February 2018. |

| 80. |

Asad Hashim, "Afghan refugees return home amid Pakistan crackdown," Al Jazeera, February 26, 2017; Nassim Majidi, "From Forced Migration to Forced Returns in Afghanistan: Policy and Program Implications," Migration Policy Institute, November 29, 2017. |

| 81. |

Ivan Safranchuk, "Afghanistan and Its Central Asian Neighbors: Toward Dividing Insecurity," Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2017. |

| 82. |

Carlotta Gall, "In Afghanistan, U.S. Exits, and Iran Comes In," New York Times, August 5, 2017; Justin Rowlatt, "Russia 'arming the Afghan Taliban', says US," BBC, March 23, 2018. |

| 83. |

Thomas Ruttig, "Climbing on China's Priority List: Views on Afghanistan from Beijing," Afghanistan Analysts Network, April 10, 2018; Michael Martina, "Afghan troops to train in China, ambassador says," Reuters, September 6, 2018. |

| 84. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia, August 21, 2017. |

| 85. |

Mark Landler and Gardiner Harris, "Trump, Citing Pakistan as a 'Safe Haven' for Terrorists, Freezes Aid," New York Times, January 4, 2018. |

| 86. |

Pakistan closed its ground and air lines of communication (GLOCs and ALOCs, respectively) to the United States after the latter suspended security aid during an earlier period of U.S.-Pakistan tensions in 2011-2012. |

| 87. |

Statement of General Joseph L. Votel, Commander, U.S. Central Command before the House Armed Services Committee on Terrorism and Iran: Defense Challenges in the Middle East, February 27, 2018. |

| 88. |

Author interviews with Pakistani military and political officials, Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan, February 2018. |

| 89. |

Author interview with Afghan officials, Islamabad, Pakistan, February 24, 2018. |

| 90. |

Much attention has been paid to Afghanistan's potential mineral and hydrocarbon resources, which by some estimates could be considerable but have yet to be fully explored or developed. Once estimated at nearly $1 trillion, the value of Afghan mineral deposits has since been revised downward, but those deposits reportedly have attracted interest from the Trump Administration. Mark Landler and James Risen, "Trump Finds Reason for the U.S. to Remain in Afghanistan: Minerals," New York Times, July 25, 2017. Additionally, Afghanistan's geographic location could position it as a transit country for others' resources. The United States has emphasized the development of a Central Asia-South Asia trading hub, dubbed a "New Silk Road" (NSR), in an effort to keep Afghanistan economically viable and perhaps also to counter a similar Chinese initiative ("One Belt, One Road"). |

| 91. |

World Bank Data, last updated October 17, 2017. |

| 92. |

Afghanistan was ranked as "Tier 2" in the State Department Trafficking in Persons Report for 2017, an improvement from 2016 when Afghanistan was ranked as "Tier 2: Watch List" on the grounds that the Afghan government was not demonstrating increased efforts against trafficking since the prior reporting period. |

| 93. |

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, July 30, 2018. |

| 94. |

Estimated Cost to Each U.S. Taxpayer of Each of the Wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, July 2017. Available at http://www.govexec.com/media/gbc/docs/pdfs_edit/section_1090_fy17_ndaa_cost_of_wars_to_per_taxpayer-july_2017.pdf. |

| 95. |

See, for example, Daniel R. Coats, Director of National Intelligence, Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community, February 13, 2018: "The overall situation in Afghanistan probably will deteriorate modestly this year [2018] in the face of persistent political instability, sustained attacks by the Taliban-led insurgency, unsteady Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) performance, and chronic financial shortfalls." |

| 96. |

See, for example, Max Fisher, "In Afghanistan's Unwinnable War, What's the Best Loss to Hope For?" New York Times, February 1, 2018; Susan Rice, "Tell the Truth About Our Longest War," New York Times, March 14, 2018. |