The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Changes from June 15, 2018 to April 7, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight,

April 7, 2021

Programs, and Activities

Libby Perl

The federal Fair Housing Act, enacted in 1968 as Title VIII Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Contents

- Introduction

- A Brief Overview of the Fair Housing Act

- HUD's Involvement in Enforcement of the Fair Housing Act

- HUD Funding for State, Local, and Private Nonprofit Fair Housing Programs

- Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP)

- Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP)

- Funding for FHAP and FHIP

- HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and Enforcement Data

- Other HUD Efforts to Prevent Discrimination in Housing

- HUD's Equal Access to Housing Regulations

- HUD Guidance

- Use of Criminal Background Checks

- Nuisance Ordinances and Victims of Crime, Including Domestic Violence

- People with Limited English Proficiency

- Requirement for HUD and Grant Recipients to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing (AFFH)

- AFFH Process for Specific HUD Grantees

- The Old Process: Analysis of Impediments

- The New Rule: The Assessment of Fair Housing

- Proposed Legislation to Prevent Implementation of the AFFH Rule

- HUD Decision to Delay Implementation of the AFFH Rule

- Other Requirements Overseen by HUD's Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- Section 3, Economic Opportunities for Low- and Very Low-Income Persons

- Limited English Proficiency

Figures

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The federal Fair Housing Act, enacted in 1968 as Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act (P.L. 90-284), of the Civil Rights Act (P.L. 90-284),

Specialist in Housing Policy

prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing based on race, color, religion,

national origin, sex, familial status, and handicap. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), through its Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO),

receives and investigates complaints under the Fair Housing Act and determines if there is reasonable cause to believe that discrimination has occurred or is about to occur.

State and local fair housing agencies and private fair housing organizations also investigate complaints based on federal, state, and local fair housing laws. In fact, ifIf alleged discrimination takes place in a state or locality with its own similar fair housing enforcement agency, HUD must refer the complaint to that agency. Two programs administered by FHEO provide federal funding to assist state, local, and private fair housing organizations:

-

The Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) funds state and local agencies that HUD certifies as having

their own laws, procedures, and remedies that are substantially equivalent to the federal Fair Housing Act. Funding is used for such activities as capacity building, processing complaints, administrative costs, and training. In

FY2018,FY2021, the appropriation for FHAP was $23.9 million. - 24.4 million.

The Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) funds eligible entities, most of which are private nonprofit

organizations. Funds are used for investigating complaints, including testing (comparing outcomes when members of a protected class attempt to obtain housing with outcomes for those not in a protected class), education, outreach, and capacity building. In

FY2018FY2021, the appropriation for FHIP was $39.6 million.

66.3 million, an additional $20 million of which was provided in the American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2).

Another provision of the Fair Housing Act requires that HUD affirmatively furtherfurt her fair housing (AFFH). As part of this requirement, recipients of certain HUD funding—jurisdictions that receive Community Planning and Development grants and Public Housing Authorities—go through a processare to certify that they are affirmatively furthering fair housing. In July 2015, HUD issued a new rule governing the process, called the Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH). The rule provided that funding recipients are to assess their jurisdictions and regions for fair housing issues (including areas of segregation, racially and ethnically concentrated areas of poverty, disparities in access to opportunity, and disproportionate housing needs), identify factors that contribute to these fair housing issues, and set priorities and goals for overcoming them. HUD is to provide data for program participants to use in preparing their AFHs, as well as a tool that helps program participants through the AFH process. However, as of May 2018, HUD has indefinitely delayed implementation of the AFFH rule. In response, a group of advocacy organizations has filed a lawsuit challenging HUD's failure to implement and enforce the rule.

Among other activities undertaken by HUD'

Within two years of publication of the final rule, HUD suspended it indefinitely, in May 2018. Within another two years,

HUD issued a different final rule, entitled “Preserving Community and Neighborhood Choice,” which became effective on September 8, 2020. Grant recipients are to certify that they have taken an action rationally related to “promoting one or more attributes of fair housing”—that it is “affordable, safe, decent, free of unlawful discrimination, and accessible as required

under civil rights laws.” The Biden Administration has asked HUD to examine the effects of both repealing the 2015 rule and

implementing the new one on the agency’s duty to affirmatively further fair housing.

Among other activities undertaken by HUD’s FHEO are efforts to prevent discrimination that may not be explicitly directed against protected classes under the Fair Housing Act. This includes issuing a regulation to prohibit discrimination in HUD programs based on sexual orientation and gender identity and releasing new guidance in 2016 addressing several issues: the use of criminal background checks in screening applicants for housing, local nuisance ordinances that may disproportionately affect victims of domestic violence, and failure to serve people who have limited English proficiency.

FHEO also oversees efforts to ensure that clients with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) have access to HUD programs. Guidance from FHEO helps housing providers determine how best to provide translation services, and HUD also receives a small appropriation through the Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity account for the agency to translate documents and provide translation on the phone or at events. Another requirement overseen by FHEO is Section 3, which provides employment and training opportunities for low- and very low-income persons. Section 3 requirements apply to hiring associated with certain housing projects funded by HUD.

Introduction

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 23 link to page 31 link to page 23 link to page 25 link to page 32 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 A Brief Overview of the Fair Housing Act .......................................................................... 2 HUD’s Involvement in Enforcement of the Fair Housing Act................................................. 4 HUD Funding for State, Local, and Private Nonprofit Fair Housing Programs .......................... 5

Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) ..................................................................... 5

Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) ....................................................................... 6 Funding for FHAP and FHIP ....................................................................................... 7

HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and Enforcement Data ................................................... 8 Other HUD Efforts to Prevent Discrimination in Housing ................................................... 11

HUD’s Equal Access to Housing Regulations .............................................................. 12 HUD Guidance ....................................................................................................... 13

Use of Criminal Background Checks ..................................................................... 14

Nuisance Ordinances and Victims of Crime, Including Domestic Violence .................. 15 People with Limited English Proficiency ............................................................... 15

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing ............................................................................. 16

Status of HUD AFFH Regulations.............................................................................. 17

Limited English Proficiency ........................................................................................... 18

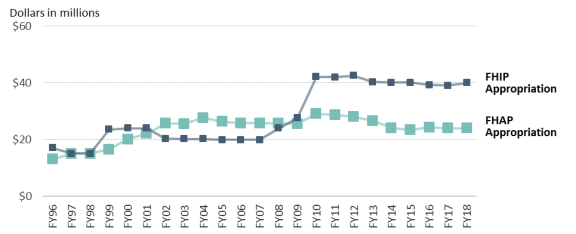

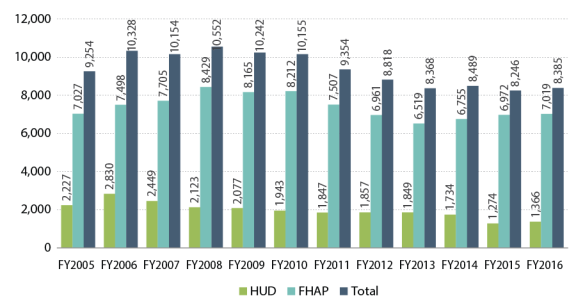

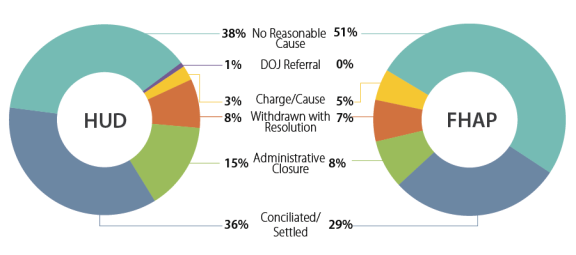

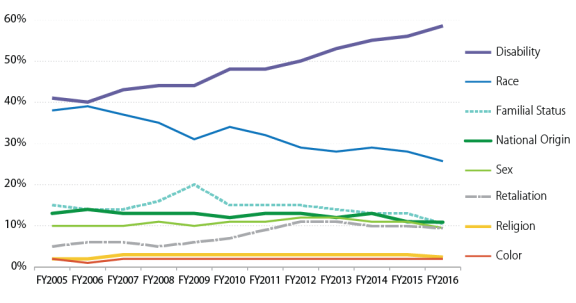

Figures Figure 1. FHAP and FHIP Funding Trends, FY1996-FY2021 ................................................ 8 Figure 2. Number of Complaints Filed with HUD and FHAP Agencies ................................... 9 Figure 3. HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint Disposition ................................................... 10 Figure 4. HUD and FHAP Complaints Filed by Protected Status .......................................... 11

Tables

Table A-1. Funding for FHAP and FHIP, FY1996-FY2021 .................................................. 20 Table B-1. Comparison of AFFH Processes ....................................................................... 28

Appendixes Appendix A. FHAP and FHIP Funding Table..................................................................... 20 Appendix B. Chronology of AFFH Proposed and Final Rules, 2015-2020.............................. 22

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 29

Congressional Research Service

link to page 19 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Introduction The Fair Housing Act was enacted as Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-284).1 As initial y The Fair Housing Act was enacted as Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-284).1 As initially enacted, the Fair Housing Act prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing based on race, color, religion, and national origin. In 1974, Congress added sex as a protected category (the Housing and Community Development Act, P.L. 93-383), and in 1988 it added familial status and handicap (the Fair Housing Amendments Act, P.L. 100-430). The Fair

Housing Act also prohibits retaliation when individuals attempt to exercise their rights (or assist

others in exercising their rights) under the law.2

2

This report discusses the Fair Housing Act from the perspective of the activities undertaken and

programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and its Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity (FHEO). For information about legal aspects of the Fair Housing Act, such as types of discrimination, exceptions to the law, and discussion of

court precedent, see CRS Report 95-710, The Fair Housing Act (FHA): A Legal Overview.

HUD and FHEO play a role in enforcing the Fair Housing Act by receiving, investigating, and making determinations regarding complaints of Fair Housing Act violations. FHEO also oversees federal funding to state, local, and nonprofit organizations that investigate fair housing complaints based on federal, state, or local laws through the Fair Housing Assistance Program and Fair

Housing Initiatives Program.

The Fair Housing Act also requires that HUD affirmatively further fair housing (AFFH). While

not defined in statute, affirmatively furthering fair housing has been found by courts to mean doing more than simply refraining from discrimination, and working to end discrimination and segregation.33 In July 2015, HUD released new regulations thata rule to govern how certain recipients of HUD funding (those receiving Community Planning and Development formula grants and Public Housing Authorities) must affirmatively further fair housing. However, as of the date of this report, HUD had delayed implementation of new regulations.

Additionally, HUD and FHEO have takenIn 2018, HUD suspended enforcement of the 2015 AFFH rule, and on August 7, 2020, it issued a new rule that repealed and replaced the 2015

AFFH rule.

Additional y, under the Obama Administration, HUD and FHEO took steps to protect against

steps to protect against discrimination not explicitly directed against members of classes protected under the Fair Housing Act—issuing regulationsa rule to prevent discrimination in HUD programs based on sexual orientation and gender identity (the equal access to housing rule), and providing guidance to prevent discrimination that may arise from criminal background checks, nuisance ordinances, and failure to provide housing to those who do not speak English.

After a brief summaryWhile the Trump Administration

released a proposed rule to make changes to the equal access to housing rule, it did not become final. Further, under the Biden Administration HUD wil consider discrimination based on sex to include sexual orientation and gender identity in al housing, an expansion of the protections in

the equal access to housing rule, which applied only to HUD programs.4

1 42 U.S.C. §3601 et seq. 2 42 U.S.C. §3617. 3 For more information, see the section of the report entitled “ Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing”. 4 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Memorandum: Implementation of Executive Order 13988 on the Enforcem ent of the Fair Housing Act, February 11, 2021, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/FHEO/documents/WordenMemoEO13988FHActImplementation.pdf (hereinafter Mem orandum : Im plementation of Executive Order 13988 on the Enforcem ent of the Fair Housing Act).

Congressional Research Service

1

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

After a brief summary of the Fair Housing Act, this report discusses each of these Fair Housing

activities, as wel as another initiative administered by FHEO, Limited English Proficiency.

, this report discusses each of these Fair Housing activities, as well as two other initiatives administered by FHEO, Limited English Proficiency and Section 3, the latter of which provides economic opportunities for low- and very low-income persons.

A Brief Overview of the Fair Housing Act

A Brief Overview of the Fair Housing Act The Fair Housing Act protects specified groups from discrimination in obtaining and maintaining housing. The act applies to the rental or sale of dwellingdwel ing units with exceptions for single-family homes (as long as the owner does not own more than three single-family homes) and dwellings dwel ings

with up to four units where one is owner-occupied.4 5

Discrimination based on the following characteristics is prohibited under the act:

- Race

- Color

- . In cases where the statute defines a protected characteristic, or there is additional relevant information on

exemptions or how a protected category is interpreted, it is included here. The terms race, color,

and national origin are not defined in the Fair Housing Act statute.

Race Color Religion—The statute provides an exemption for religious organizations to rent

or sellor sel property they own or operate to members of the same religion (as long as membership is not restricted based on race, color, or national origin).5 - National origin

Sex—Courts have found discrimination based on sex to include sexual harassment, and HUD regulations establish standards for quid pro quo and hostile environment sexual harassment that violates the Fair Housing Act.6However, sex does not expressly include sexual orientation. Note, however, that discrimination based on nonconformity with gender stereotypes may be covered by the Fair Housing Act as discrimination based on sex. For more information, see CRS6 National origin Sex—In February 2021, HUD released a memo stating that it would begin accepting complaints for discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, and that FHEO would conduct “al other activities involving the application, interpretation, and enforcement of the Fair Housing Act’s prohibition on sex discrimination to include discrimination because of sexual orientation and gender identity.”7 HUD issued this guidance in response to the 2020 decision, Bostock v. Clayton County, in which the Supreme Court held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred employers from firing an individual for being gay or transgender.8 HUD’s guidance explains that “the Fair Housing Act’s sex discrimination provisions are comparable to those of Title VII and that they likewise prohibit discrimination because of sexual orientation and gender identity.” Further, courts have found discrimination based on sex to include sexual harassment, and HUD regulations outline quid pro quo and hostile environment sexual harassment that violates the Fair Housing Act.9 Discrimination based on nonconformity with gender stereotypes may also be unlawful sex-based discrimination under the Fair Housing Act.10 5 42 U.S.C. §3603. For more information about this exception, see CRS Report 95-710, The Fair Housing Act (FHA): A Legal Overview,Familial6 42 U.S.C. §3607(a). 7 Memorandum: Implementation of Executive Order 13988 on the Enforcement of the Fair Housing Act . 8 For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10496, Supreme Court Rules Title VII Bars Discrimination Against Gay and Transgender Em ployees: Potential Im plications. 9 24 C.F.R. §100.600. 10 For more information, see CRS Report 95-710, The Fair Housing Act (FHA): A Legal Overview. Congressional Research Service 2 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities Familial status—The statute defines familial status to mean parents or others having custody of one or more children under age 18.711 Familial status discrimination does not apply to housing dedicated to older persons.8Handicap912 Handicap13—The statute defines handicap as having a physical or mental impairment thatsubstantiallysubstantial y limits one or more major life activities, having a record of such impairment, or being regarded as having such an impairment.101115 Major life activities means"“functions such as caring for one's’s self, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning and working."12

”16 Note that states and localities may have fair housing laws with broader protections than those encompassed in the federal Fair Housing Act, including such protected classes as age, sexual orientation, or source of income (prohibiting discrimination against those relying on government subsidies to pay for housing).

The Fair Housing Act protects individuals in the covered classes from discrimination in a range of

activities involving housing. Some of the specific types of activities that are prohibited include

the following:13

- 17

Refusing to rent or

sellsel , refusing to negotiate for a rental or sale, or otherwise making adwellingdwel ing unavailable - Discriminating in the terms, conditions, or privileges of sale or rental or in the services and facilities provided in connection with a sale or rental.

- Making, printing, or publishing notices, statements, or advertisements that indicate preference, limitation, or discrimination in connection with a sale or rental based on protected class.

-

Representing that a

dwellingdwel ing is not available -

Inducing, for profit, someone to

sellsel or rent based on the representation that members of a protected class are moving to the neighborhood (sometimes referred to as blockbusting). -

Refusing to

allowal ow reasonable modifications or reasonable accommodations for persons with a disability. Reasonable modifications involve physical changes to the property while reasonable accommodations involve changes in rules, policies, practices, or services to accommodate disabilities. -

Discriminating in

"“residential real estate related transactions,"” including the provision of loans andsellingsel ing, brokering, or appraising property.14 Retaliating18 11 42 U.S.C. §3602(k). 12 42 U.S.C. §3607(b). 13 Although the term “disability” has come to be preferred, the Fair Housing Act still uses the word “handicap.” 14 42 U.S.C. §3602(h). 15 24 C.F.R. §100.201. 16 Ibid. 17 Unless otherwise noted, prohibited activities are listed at 42 U.S.C. §3604. 18 42 U.S.C. §3605. Congressional Research Service 3 link to page 8 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities Retaliating (i.e., coercing, intimidating, threatening, or interfering) against anyone attempting to exercise rights under the Fair Housing Act.15

HUD'19

HUD’s Involvement in Enforcement of the Fair Fair Housing Act

HUD, together with state and local fair housing agencies and private fair housing organizations, investigates fair housing complaints. HUD receives complaints from individuals who believe they have been subject to discrimination or are about to experience discrimination. If the discrimination takes place in a state or locality with its own similar fair housing enforcement agency, sometimes referred to as a Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) agency, HUD must

refer the complaint to that agency.1620 (See the " “Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP)"” section of this report for more information about state and local agencies.) In addition, if a complaint involves a challengechal enge to zoning or land use laws, then HUD must refer the case to the Department of Justice (DOJ).1721 HUD also refers complaints with possible criminal violations or patterns or

practices of discrimination to DOJ.18

22

Once an individual has filed a complaint with HUD, or HUD has filed a complaint on its own initiative, a notice is served on the party allegedal eged to have discriminated. That party, in turn, has the opportunity to file a response to the complaint.1923 HUD investigates complaints to determine if

there is reasonable cause to believe a discriminatory practice has occurred or is about to occur.20 24 While an investigation is ongoing, HUD may also engage in conciliation to try to reach an agreement between the parties.2125 Conciliation requires voluntary participation of both parties. Relief can be sought both for the aggrieved party and for the public interest. If parties do not reach an agreement, then HUD determines whether there is reasonable cause to believe

discrimination occurred or was about to occur.22

No26 No Reasonable Cause: If HUD finds no reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred, then it dismisses the complaint. While not part of the statutory process, HUD mayallowal ow the person submitting the complaint to ask for reconsideration of the denial.23- 27

Reasonable Cause: If HUD finds reasonable cause to believe that discrimination

occurred, it issues a charge—a written statement of facts on which the

determination of reasonable cause is based.

2428 Either party may request that the case be heard in court, but if neither party makes this election, then the case is 19 42 U.S.C. §3617. 20 42 U.S.C. §3610(f). 21 42 U.S.C. §3610(g)(2)(C). 22 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Annual Report on Fair Housing, FY2012-2013, November 7, 2014, p. 27, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=2012-13annreport.pdf. 23 42 U.S.C. §3610(a). 24 42 U.S.C. §3610(g). 25 42 U.S.C. §3610(b). 26 42 U.S.C. §3610(g), 24 C.F.R. §103.400. 27 See HUD’s website at https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/complaint-process, accessed February 22, 2021. 28 42 U.S.C. §3610(g), 24 C.F.R. §103.405. Congressional Research Service 4 link to page 11 link to page 11 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activitiescase be heard in court, but if neither party makes this election, then the case isheard before an administrative law judge.2529 If the case goes to federal court, then HUD transfers the case to DOJ.26

30

Aggrieved parties may seek actual monetary damages. The law also allowsal ows an administrative law

judge to impose a civil penalty "“to vindicate the public interest"” (amounts vary based on whether

there have been previous infractions) and to order injunctive relief.27

31

If an individual withdraws a complaint, no longer cooperates, or cannot be reached for follow -up,

then HUD closes the complaint as an administrative closure.28

In FY2016, there were 1,366 complaints filed with HUD.29 Of those, 2.5% led to HUD issuing a charge, 35.8% were settled through conciliation, and 37.7% resulted in a finding of no reasonable cause.30 The remainder of complaints either had an administrative closure (where complainants did not continue to pursue their complaints), were withdrawn with a resolution, or were referred to DOJ. 32

For more information on complaints, see "“HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and Enforcement Data."

Data.” HUD Funding for State, Local, and Private Nonprofit Fair Housing Programs

HUD oversees two programs that promote fair housing at the state and local level: the Fair

Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) and the Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP). FHAP funds state and local fair housing agencies, and FHIP funds eligible entities that largely include private nonprofit organizations.3133 These recipients in turn supplement HUD'’s efforts to promote fair housing, detect discrimination, investigate complaints, and enforce the fair housing law. The

following subsections describe FHAP and FHIP and provide funding levels for the programs.

Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP)

FHAP funds state and local agencies that HUD certifies as having their own laws, procedures, and remedies that are substantiallysubstantial y equivalent to the federal Fair Housing Act.3234 The Fair Housing statute requires HUD to refer complaints that violate state and local fair housing laws to the certified agencies responsible for enforcing them (in jurisdictions that have such agencies).3335 At the time of the enactment of the Fair Housing Act, multiple states and local jurisdictions had

enacted their own laws and established agencies for their enforcement.34

36

Funding to assist state and local agencies in enforcing fair housing laws was first provided in the FY1980 Appropriations Act for HUD (P.L. 96-103) after a budget request from the Carter Administration. The FY1980 budget justifications discussed limitations in the ability ) after a budget request from the Carter 29 42 C.F.R. §3612. 30 State of Fair Housing Annual Report to Congress, FY2018 -FY2019, p. 29, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/FHEO/documents/FHEO%20Report%202020%20-%20Printable%20Version.pdf (hereinafter, FY2018-FY2019 Annual Fair Housing Report to Congress).

31 42 U.S.C. §3612(g)(3). 32 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Handbook 8024.1, Title VIII Complaint Intake, Investigation, and Conciliation, pp. 9-1, https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/80241c9FHEH.pdf.

33 Kenneth T emkin, Tracy McCracken, and Veralee Liban, Study of the Fair Housing Initiatives Program , U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, May 2011, p. 21, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/FHIP_2011.pdf. 34 42 U.S.C. §3610(f)(3). 35 42 U.S.C. §3610(f)(1). 36 See, for example, Housing and Home Finance Agency, Fair Housing Laws: Summaries and Text of State and Municipal Laws (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964). See also U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking and the Currency, Subcommittee on Housing and Urban Affairs, S. 1358, S. 2114, and 2280 Relating to Civil Rights and Housing, 90th Cong., 1st sess., August 21-23, 1967, pp. 491-496.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 11 link to page 11 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Administration. The FY1980 budget justifications discussed limitations in the ability of states to handle fair housing complaints referred from HUD, and that in many cases complaints had to be sent back to HUD for processing.3537 The President'’s budget proposed funding for financial and technical assistance to assist states in handling fair housing complaints, with first-year funding provided for capacity building, and subsequent years'’ funding based on the number of complaints processed by each agency. Funding continues to be based on the number of complaints handled

by FHAP agencies. Congress followed the Administration'’s FY1980 request and appropriated $3.7 mil ion $3.7 million for the program. The appropriation initially initial y supported 31 state and local agencies.36 38 At the end of FY2016FY2019, there were 8577 state and local agencies, which represents a gradual reduction over recent years as agencies withdrew from the program; in FY2009, 113 FHAP

agencies were funded.37

39

Activities for which FHAP agencies receive funding include capacity building, processing complaints, administrative costs, training, and special enforcement efforts.3840 When a FHAP agency receives a fair housing complaint, it goes through much the same process as HUD.3941 The

agency conducts an investigation, and, as the investigation is ongoing, works on conciliation with the parties. For more information on complaints, see “HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and

Enforcement Data.”

the parties. In FY2016, there were 7,019 complaints filed with FHAP agencies around the country.40 Of these, 5.3% led to FHAP agencies finding reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred, 28.9% were settled through conciliation, and 50.7% resulted in a finding of no reasonable cause.41 The remainder of complaints had an administrative closure or were withdrawn with a resolution. For more information on complaints, see "HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and Enforcement Data."

Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP)

Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) The Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) was created as part of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1987 (P.L. 100-242) as a demonstration program and was made permanent in 1992 (P.L. 102-550). Through FHIP, HUD enters into contracts or awards competitive grants to eligible

eligible entities—including state and local governments, nonprofit organizations, or other public or private entities, including FHAP agencies—to participate in activities resulting in enforcement of federal, state, or local fair housing laws, and for education and outreach. The majority of FHIP

grantees are private nonprofit organizations.

FHIP was added to the Fair Housing law in recognition of the fact that additional assistance was needed to detect fair housing violations and enforce the law. In particular, FHIP authorized funding for organizations to conduct testing whereby matched pairs of individuals, one with protected characteristics and the other without, both attempt to obtain housing from the same providers.

providers. HUD funds three activities that are provided for under the statute:42

- 42

37 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY1980 Budget Justifications, p. Q-2. 38 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY1981 Budget Justifications, p. P-7. 39 FY2018-FY2019 Annual Fair Housing Report to Congress, p. 52; and FY2009 Budget Justifications, p. O-3, http://archives.hud.gov/budget/fy09/cjs/fheo1.pdf.

40 24 C.F.R. §115.302 and §115.304. 41 HUD regulations spell out criteria that must be in state and local laws. 24 C.F.R. §115.204. 42 42 U.S.C. §3616a. A fourth activity, the Administrative Enforcement Initiative, is not currently funded. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Fair Housing Initiatives Program Application and Award Policies and Procedures Guide, July 2015, p. 246, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=fhipappguide729.docx. T he Administrative Enforcement Initiative funded state and local governments that administer laws that are substantially equivalent to the federal Fair Housing Act. 24 C.F.R. §125.201. However, these entities already receive funding under FHAP.

Congressional Research Service

6

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Private Enforcement Initiative:43 Provides funds for fair housing enforcement

organizations to investigate violations of the federal Fair Housing Act and similar state and local laws, and to obtain enforcement of the laws. Fair housing enforcement organizations are private nonprofit organizations that receive and investigate complaints about fair housing, test fair housing compliance, and bring enforcement actions for violations.

4444 Organizations may receive Private Enforcement Initiative funding if they have at least one year of experience participating in these activities. -

Education and Outreach Initiative:45 The statute provides for awards to fair

housing enforcement organizations, private nonprofit organizations, public

entities, and state or local FHAP agencies to be used for national, regional, local, and community-based education and outreach programs. Such activities include developing brochures, advertisements, videos, presentations, and training materials.

46 - 46

Fair Housing Organization Initiative:47 Provides funding for existing fair

housing enforcement organizations or new organizations to build their capacity to provide fair housing enforcement.

Organizations that receive FHIP funding investigate fair housing complaints brought to them by individuals individuals and also initiate their own investigations. If there is evidence that discrimination occurred, then FHIP agencies can help individuals file complaints with HUD or a state or local

FHAP agency, or bring a private action in court.

Funding for FHAP and FHIP Appropriations for FHIP have not been authorized since FY1994 (P.L. 102-550), and FHAP was

never separately authorized (Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act general y was authorized at such sums as necessary48) but Congress has continued to provide funding for the two programs in

every year through FY2021.

In FY2020, both programs received additional funding as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (P.L. 116-136), $1.5 mil ion for FHAP and $1 mil ion for FHIP, to address issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic. FHAP funds were available for education and outreach, technology needs, fair housing testing, and staffing related to increased complaints.49 FHIP funds were directed to the Education and Outreach Initiative, with half of the

funds set aside for a national media campaign and the other half awarded to applicants for general

education and outreach around Fair Housing Act rights and responsibilities.

FY2021 FHIP funding also increased as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The

American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2) appropriated $20 mil ion for FHIP grantees to address fair

43 42 U.S.C. §3616a(b), 24 C.F.R. §125.401. 44 42 U.S.C. §3616a(h). 45 42 U.S.C. §3616a(d), 24 C.F.R. §125.301. 46 See, for example, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY2020 Fair Housing Initiatives Notice of Funding Availability, May 11, 2020, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/SPM/documents/FHIP_Education_and_Outreach_TechnicalCorrection_5.6.2020_FR-6400-N-21A-TC.pdf.

47 42 U.S.C. §3616a(c), 24 C.F.R. §125.501. 48 42 U.S.C. §3618. 49 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Notice: Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP) COVID-19 Funds, April 20, 2020, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Main/documents/FHAP-COVID-19-Funds.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 11 link to page 23 link to page 23

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

housing complaints, conduct investigations, engage in education and outreach, and account for

increased program delivery costs.

Figure 1, below, shows funding for FHAP and FHIP since FY1996. (Funding for FHAP and FHIP

In FY2018, appropriations were approximately $24 million for FHAP and almost $39 million for FHIP. These are reductions from peak funding, which occurred between FY2010 and FY2012. In FY2010, FHAP funding reached $29 million and in FY2012 FHIP funding was nearly $43 million. Prior to FY2010, funding for FHIP was significantly lower than what it has been since that time. In FY2010, funding for FHIP jumped from almost $28 million, at that point the most that had ever been appropriated for the program, to $42 million. The President's budget for FY2010 proposed increased funding for a mortgage fraud prevention initiative, through FHIP. And while Congress appropriated additional funds for FHIP, it was not done as a separate set-aside for mortgage fraud prevention.48 The same year, funding for FHAP increased by nearly $4 million. While funding for FHAP has fallen to its previous levels, funding for FHIP has remained well above the FY2009 level, ranging between $39 million and $42 million. Figure 1, below, shows these funding trends. For exact amounts For exact amounts

appropriated since FY1996, see the Appendix.

see Appendix A.)

Figure 1. FHAP and FHIP Funding Trends, FY1996- |

|

FY2021

Source: For |

HUD and FHAP Agency Complaint and Enforcement Data

A Note About Fair Housing Data

HUD issues annual reports |

HUD reports the number of fair housing complaints it receives as well wel as those received by FHAP agencies. In recent years, the number of complaints filed with both HUD and FHAP agencies has declined, from a high of 10,552 in FY2008 to 8,385 in FY20167,729 in FY2019, the most recent year in which data are available.5152 During this time period, the number of FHAP agencies decreased from 108 operating at the end of FY2008 to 8577 at the end of FY2019.53 See at the end of FY2016.52 In addition, complaints received by private fair housing organizations (those not receiving FHAP funding), as reported by the National Fair Housing Alliance, decreased slightly between 2008 and 2015, with about 500 fewer requests in 2015 than the 20,173 reported in 2008.53 See Figure 2 for HUD and FHAP Figure 2 for HUD and FHAP

agency complaints between FY2005 and FY2016.

FY2008 and FY2019. Figure 2. Number of Complaints Filed with HUD and FHAP Agencies FY2005-FY2016 |

|

FY2008-FY2019

Source: HUD Annual Reports on Fair Housing, FY2008- |

src=/annualreport.

Complaints filed with HUD and FHAP agencies rarely result in charges against housing

providers. In fact, in many cases there is a finding of no reasonable cause to pursue the complaint—38% 37% of complaints for HUD and 5155% for FHAP agencies in FY2016.FY2019.54 HUD conciliated and settled 36% of cases in FY2016FY2019, with FHAP agencies doing so for 2920% of cases. Only 32% of complaints to HUD and 58% of those to FHAP agencies resulted in a charge being filed in FY2016. FY2019. Approximately a quarter21% of complaints for HUD were either administrative closures, meaning generally

general y that complainants did not continue to pursue their complaints, or were withdrawn after some kind of resolution. For FHAP agencies, 1517% of cases were either administrative closures or withdrawn with resolution. SeeSee Figure 3 for HUD and FHAP agency complaint dispositions in FY2016.

FY2016 |

|

|

Recent years have brought a change in the types of complaints received by HUD and FHAP agencies. Approximately 10 years ago, in FY2005, the percentagesFY2016FHEOAnnualReport.pdf.

Since FY2005, the highest percentage of fair housing complaints filed have been based on disability. Until that time, the percentage of complaints based on race and disability were had been nearly equal: 38% and 41% of total complaints, respectively.55 However, by FY2016FY2019 the

percentage of complaints based on disability increased to 5962%, and race declined to 26%.56 (Note that in calculating complaint percentages HUD takes into account the fact that one case may allege multiple al ege multiple bases for discrimination. As a result, the sum of percentages for all al types of discrimination exceeds 100%.) Other protected categories—familial status, Familial status complaints have also declined somewhat during this period, while other protected categories—national origin, sex, religion, and color—have

remained at about the same levels during the same time period. HUD also reports the number of complaints based on retaliation, which have increased from approximately 5% in FY2005 to 913% in FY2016FY2019. See

Figure 4 for complaints filed by protected class in FY2016.

through FY2019.

The high percentage of complaints based on disability may in part have to do with additional protections for people with disabilities. Unlike other protected statuses, the Fair Housing Act imposes affirmative duties on housing providers to make "“reasonable accommodations" for individuals ” for individuals with disabilities. Under the law, it is discriminatory to refuse to allowal ow residents with disabilities disabilities to make physical changes to the premises, at their own expense, in order to afford

them full enjoyment of the premises.5457 Examples of reasonable accommodations include changes to a unit such as widening doorways, installinginstal ing a ramp or grab bars, or lowering cabinets.5558 In addition, the law gives residents with disabilities the right to request "“reasonable accommodations"accommodations” in the rules, policies, practices, or services that may ordinarily apply to housing residents. It is considered discrimination under the Fair Housing Act to refuse to make a 55 FY2008 Annual Report on Fair Housing, p. 3. 56 FY2018-FY2019 Annual Fair Housing Report to Congress, p. 24. 57 42 U.S.C. §3604(f)(3)(A). 58 See Reasonable Modifications Under the Fair Housing Act, Joint Statement of T he Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Justice, March 5, 2008, p. 4, https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/reasonable_modifications_mar08.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

10

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

reasonable accommodation in order to give residents with disabilities reasonable accommodation in order to give residents with disabilities an equal opportunity to use and enjoy their dwelling unit.56dwel ing unit.59 Examples of reasonable accommodations include making parking spaces available to residents with disabilities or allowingal owing assistance animals in a property that does not otherwise allow pets.57al ow pets.60 An accommodation is not considered reasonable if it imposes an undue financial or administrative burden, or if it fundamentallyfundamental y alters the nature of the housing provider'provider’s operations.58 In FY201661 In FY2019, the failure to make a reasonable accommodation was the

second-most frequently raised issue in complaints, representing 4043% of HUD and FHAP complaints raised in cases filed (after discriminatory terms, conditions, privileges, services, and

facilities in the rental or sale of property).59

62 Figure 4. HUD and FHAP Complaints Filed by Protected Status FY2005-FY2016 |

|

FY2005-FY2019

Source: HUD Annual Reports on Fair Housing, FY2008-FY2016, available at http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD? src=/annualreport. Note: Percentages represent the number of discrimination |

Other HUD Efforts to Prevent Discrimination in Housing

In recent years, HUD has in Housing During the Obama Administration, HUD issued regulations and guidance to protect individuals from discrimination that may not be explicitly directed against protected classes under the Fair 59 42 U.S.C. §3604(f)(3)(B). 60 Reasonable Accommodations Under the Fair Housing Act, Joint Statement of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Justice, May 17, 2004, http://www.nhl.gov/offices/fheo/library/huddojstatement.pdf.

61 Ibid., p. 7. 62 FY2018-FY2019 Annual Fair Housing Report to Congress, p. 26. HUD calculates percentages based on total number of complaints as a percentage of all cases filed. Because each case can contain more than one basis for a complaint, the sum of percentages exceeds 100%.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 5 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Housing Act. In one case, HUD used its authority to prevent discrimination in the programs it administers by issuing regulations prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. HUD has also released guidance to inform housing providers and localities about policies that may seem faciallyfacial y neutral but could have discriminatory effects in violation of the Fair Housing Act. These include policies regarding criminal background checks, local nuisance ordinances that prohibit certain behaviors, and treatment of people with limited English proficiency.

proficiency.

The following subsections describe HUD'’s regulations regarding equal access to housing as well wel

as several guidance documents HUD released during 2016.

HUD'’s Equal Access to Housing Regulations

In 2012, HUD published a final rule providing for equal access to HUD housing programs regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.63 The Fair Housing Act does not expressly protect individuals from discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. (Note, however, that discrimination based on nonconformity with gender stereotypes may be covered by the Fair Housing Act as discrimination based on sex.)60 However, HUD,, and at the time of the rule’s publication, HUD did not interpret discrimination based on sex to include sexual orientation and gender identity. (In February 2021, HUD announced it would interpret

discrimination based on sex more expansively. See “A Brief Overview of the Fair Housing Act”.) As a result, HUD issued the rule pursuant to its charge to ensure equal access to its programs, and

to provide "“decent housing and a suitable living environment for every American family," published a final rule in 2012 providing for equal access to HUD housing programs regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.61 .”64

The regulations promulgated by the rule apply to all al HUD housing programs, including loan programs. Housing in these programs must be made available without regard to actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status.6265 In addition, the rule provided that property owners, program administrators, and lenders may not inquire about sexual orientation or

gender identity of an applicant for or occupant of HUD-insured or HUD-assisted housing.63

66

Application of Equal Access Rules to Emergency Shelters

The 2012 regulations contained an exception to the prohibition on inquiries into sex when an individual individual is an applicant or occupant of temporary emergency shelter where there may be shared bedrooms or bathrooms or to determine the number of bedrooms to which a family is entitled. However, theThe exception resulted in a number of commenters to the proposed rule expressing concern about

transgender individuals'’ ability to gain access to single-sex shelters in accordance with their gender identity. While HUD noted that it was not mandating a policy on placement of transgender persons, it said it would monitor how programs operate and issue additional guidance if necessary.

necessary.

2016 Final Rule: In February 2015, based on this monitoring, HUD followed up by issuing a notice governing Community Planning and Development (CPD) programs—Community Development Block Grants, HOME Investment Partnerships (HOME), Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA), Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG), and the Continuum of Care program.64 In the notice, 67 In the notice,

63 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Equal Access to Housing in HUD Programs Regardless of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity,” 77 Federal Register 5662-5676, February 3, 2012, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-02-03/pdf/2012-2343.pdf. 64 77 Federal Register 5672. 65 24 C.F.R. §5.105(a)(2)(i). 66 77 Federal Register 5674. 67 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Notice CPD-15-02, Appropriate Placement for Transgender

Congressional Research Service

12

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

HUD clarified that it expected placement in single-sex shelters to occur in accordance with an individual'individual’s gender identity. HUD followed this notice, in November 2015, with a proposed rule that would apply to HUD CPD programs.6568 A final rule was released on September 21, 2016, and

was effective one month later.66

69

The final rule requires that placement in facilities with shared sleeping and/or bath accommodations occur in conformance with a person'’s gender identity. In addition, the final rule removed the general prohibition in the 2012 regulation on asking questions about sexual orientation and gender identity so that providers can ask questions to ensure they are complying

with the rule.67 However, the70 The rule provides that individuals shall shal not be asked "intrusive"“intrusive” questions or "“asked to provide anatomical information or documentary, physical, or medical evidence of the individual'individual’s gender identity."68”71 The final rule also updated the definition of gender identity as it

applies to all al HUD programs and defined "perceived"“perceived” gender identity.69

HUD Guidance

72

2020 Proposed Rule: On July 24, 2020, HUD released a proposed rule to make changes to the 2016 equal access rule. The proposed rule stated that HUD had reconsidered the 2016 rule’s provisions, and that providers operating single-sex facilities should be able to consider biological sex, and make their own determinations about biological sex, in making placement decisions,

without regard to gender identity.73 According to HUD, “the 2016 Rule impermissibly restricted single-sex facilities in a way not supported by congressional enactment, minimized local control, burdened religious organizations, manifested privacy issues, and imposed regulatory burdens.”74

The 2020 proposed rule was not made final.

HUD Guidance In 2016, HUD released several guidance documents that inform housing providers and local communities about policies and practices that may violate the Fair Housing Act by having a

discriminatory effect on members of a protected class. The guidance addresses how use of criminal background checks, nuisance ordinances, and treatment of people with limited English proficiency can potentiallypotential y result in discrimination against members of protected classes. The guidance discusses situations where . The guidance discusses situations where

Persons in Single-Sex Em ergency Shelters and Other Facilities, February 20, 2015, https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/Notice-CPD-15-02-Appropriate-Placement-for-Transgender-Persons-in-Single-Sex-Emergency-Shelters-and-Other-Facilities.pdf.

68 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Equal Access in Accordance W ith an Individual’s Gender Identity in Community Planning and Development Programs,” 80 Federal Register 72642, November 20, 2015, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-11-20/pdf/2015-29342.pdf.

69 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Equal Access in Accordance With an Individual’s Gender Identity in Community Planning and Development Programs,” 81 Federal Register 64763-64782, September 21, 2016, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-09-21/pdf/2016-22589.pdf. 70 Ibid., p. 64765. 71 Ibid., p. 64782. 72 81 Federal Register 64782. T he new definition of gender identity is “the gender with which a person identifies, regardless of the sex assigned to that person at birth and regardless of the person’s perceived gender identity.”

Perceived gender identity is “the gender with which a person is perceived to identify based on that person’s appearance, behavior, expression, other gender related characteristics, or sex assigned to the individual at birth or identified in documents.” 73 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Making Admission or Placement Determinations Based on Sex in Facilities Under Community Planning and Development Housing Programs, ” 85 Federal Register 44811, July 24, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-07-24/pdf/2020-14718.pdf.

74 85 Federal Register 44812.

Congressional Research Service

13

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

discrimination could occur and the balancing test used to determine if policies or practices have a

discrimination could occur and the balancing test used to determine if policies or practices have a discriminatory effect.

discriminatory effect.

Disparate Impact

Each of the HUD guidance documents described in this section relies on a burden-shifting test for determining discriminatory effects discrimination, which is also referred to as disparate impact discrimination. The test is drawn from case law and HUD regulations published in 2013.75 In 2015, the Supreme Court added clarity to the issue when it held that disparate impact claims are cognizable under the Fair Housing Act and outlined the burden-shifting test that should be applied for assessing disparate impact discrimination claims. The burden-shifting test applied by the Supreme Court was similar, but not identical, to the test outlined in HUD’s prior regulations and guidance. In September 2020, HUD issued a new disparate impact rule modifying the one issued in 2013.76 HUD stated that modifications were made to bring the rule into alignment with the Supreme Court decision as understood by HUD.77 As of the date of this report, the 2020 disparate impact rule had not gone into effect because a federal district court, as part of a legal chal enge to the rule, issued a preliminary injunction enjoining HUD from implementing or enforcing the rule.78 President Biden has issued a memorandum directing HUD to examine the effects of the 2020 disparate impact rule on HUD’s duty to comply with the Fair Housing Act.79 For more information, see CRS Report R44203, Disparate Impact Claims Under the Fair Housing Act.

Use of Criminal Background Checks

In April 2016, HUD’Use of Criminal Background Checks

In April 2016, HUD's Office of General Counsel released guidance applying the Fair Housing Act to use of criminal background checks in screening prospective tenants for housing.70 Unlike HUD'80 Unlike HUD’s regulations regarding discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, the guidance is directed at all al housing providers subject to the Fair Housing Act, not just HUD programs. While individuals with a record of arrests or convictions are not protected under the

Fair Housing Act, HUD'’s guidance noted that African American and Hispanic individuals are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system, and that screening for criminal records could have discriminatory effect or disparate impact based on race or national origin,

which may be prohibited under the act.

HUD’s guidance on this issue states that, in screening for criminal history (including arrest records), “arbitrary and overbroad criminal history-related bans are likely to lack a legal y sufficient justification.”81 If a housing provider does take criminal history into account, HUD’s 75 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Implementation of the Fair Housing Act ’s Discriminatory Effects Standard,” 78 Federal Register 11459, February 15, 2013, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2013-02-15/pdf/2013-03375.pdf. T he regulations were codified at 24 C.F.R. §100.500.

76 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Act, “HUD’s Implementation of the Fair Housing Act ’s Disparate Impact Standard,” 85 Federal Register 60288, September 24, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-09-24/pdf/2020-19887.pdf. 77 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “HUD’s Implementation of the Fair Housing Act ’s Disparate Impact Standard,” 84 Federal Register 42857, August 19, 2019, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-08-19/pdf/2019-17542.pdf.

78 T he final rule is at 85 Federal Register 60288, September 24, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-09-24/pdf/2020-19887.pdf. T he grant of the order of preliminary injunction was made in Massachusetts Fair Housing Center and Housing Works, Inc. v. HUD, available at http://prrac.org/pdf/massachusetts-di-pl-decision.pdf. 79 U.S. President (Biden), “Redressing Our Nation’s and the Federal Government ’s History of Discriminatory Housing Practices and Policies,” 86 Federal Register 7487-7488, January 26, 2021, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-01-29/pdf/2021-02074.pdf.

80 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate -Related T ransactions, April 4, 2016, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=HUD_OGCGuidAppFHAStandCR.pdf.

81 Ibid., p. 10.

Congressional Research Service

14

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

guidance states that the policy should be tailored to serve a “which may be prohibited under the act. For more information about discriminatory effects, also called disparate impact, see CRS Report R44203, Disparate Impact Claims Under the Fair Housing Act, by David H. Carpenter.

HUD's guidance on this issue states that, in screening for criminal history (including arrest records), "arbitrary and overbroad criminal history-related bans are likely to lack a legally sufficient justification."71 If a housing provider does take criminal history into account, HUD's guidance states that the policy should be tailored to serve a "substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest"” and consider the particulars of an individual'’s circumstances such as

type of crime and amount of time that has passed since a conviction occurred.72

82 Nuisance Ordinances and Victims of Crime, Including Domestic Violence

In September 2016, HUD released guidance about application of the Fair Housing Act to

nuisance ordinances that may result in victims of crime, particularly domestic violence, losing their housing.73 So-called83 So-cal ed nuisance ordinances, enacted at the local level, require property owners to abate—to lessen or remove—a nuisance associated with their property. The types of activities categorized as nuisances depend on jurisdiction, and may have to do with upkeep of the property itself, but they can also include disruptive behavior, criminal activity, or callscal s to law enforcement that exceed a certain minimum number. Similarly, lease provisions may consider callscal s to law

enforcement a lease violation, potentially potential y resulting in eviction. As described in the HUD guidance, callscal s from victims of domestic violence to law enforcement can result in evictions after landlords have been cited for violating nuisance ordinances for exceeding a minimum number of calls

cal s to law enforcement.74

84

The HUD guidance points out that a nuisance ordinance could have a discriminatory effect, potentiallypotential y violating the Fair Housing Act, if it is enforced disproportionately against victims of domestic violence resulting in discrimination based on sex.7585 In such a case, the burden would shift to the government enforcing the nuisance ordinance to show that the nuisance ordinance is

necessary to achieve a substantial, legitimate, and nondiscriminatory interest, and that there is no

less-discriminatory alternative.

People with Limited English Proficiency

Another area of potential discrimination where HUD released guidance in 2016 is limited English proficiency, with guidance released just days after that regarding nuisance ordinances.7686 While the

Fair Housing Act does not prohibit discrimination based on the language someone speaks, it is possible that this practice could have a discriminatory effect based on race or national origin.77 87 Language-related restrictions could include requiring that tenants speak English or turning away

tenants who do not speak English, particularly if low-cost translation services are available.78

88

If someone were to challengechal enge language-related restrictions, the same balancing test described in the other HUD guidance would apply. If a policy or behavior is shown to have a discriminatory effect, then the burden shifts to the housing provider to show that the practice is necessary to

82 Ibid. 83 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Enforcement of Local Nuisance and Crime-Free Housing Ordinances Against Victims of Domestic Violence, Other Crime Victims, and Others Who Require Police or Emergency Services, September 13, 2016, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=FinalNuisanceOrdGdnce.pdf.

84 Ibid., pp. 3-5. 85 Ibid., p. 8. 86 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of General Counsel Guidance on Fair Housing Act Protections for Persons with Lim ited English Proficiency, September 15, 2016, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=lepmemo091516.pdf.

87 Ibid., p. 2. 88 Ibid., p. 4.

Congressional Research Service

15

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

effect, then the burden shifts to the housing provider to show that the practice is necessary to serve a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest, and that no less-discriminatory

alternative is available.

Requirement for HUD and Grant Recipients to

Affirmatively FurtherFurthering Fair Housing (AFFH)

In addition to prohibiting discrimination, the Fair Housing Act, since its inception, has required HUD and other federal agencies that administer programs related to housing and urban

development to administer their programs in a way that affirmatively furthers fair housing.79

89

What "“affirmatively further fair housing" (AFFH)” means is not defined in statute. Various courts, in decisions regarding HUD'’s obligations, have concluded that it means more than refraining from discrimination.8090 For example, a federal court decision in 1973 interpreting the AFFH section of

the Fair Housing Act regarding residents of public housing stated

Action must be taken to fulfill, as much as possible, the goal of open, integrated residential housing patterns and to prevent the increase of segregation, in ghettos, of racial groups whose lack of opportunities the Act was designed to combat.81

91

A 1987 federal appellateappel ate court decision looked at the legislative history of the Fair Housing Act, saying that the "law'“law’s supporters saw the ending of discrimination as a means toward truly opening the nation'’s housing stock to persons of every race and creed."” And with that goal in

mind, the court stated

This broader goal suggests an intent that HUD do more than simply not discriminate itself; it reflects the desire to have HUD use its grant programs to assist in ending discrimination and segregation, to the point where the supply of genuinely open housing increases.82

92

In addition to HUD, the AFFH requirement has also been applied, via statute, regulation, and

competitive grants, to recipients of HUD funding. The requirement applies to communities, states, and insular areas that receive formula funds through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), HOME Investment Partnerships, Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA), and Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) programs, as well wel as to Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) that administer both Public Housing and Section 8 programs.8393 Applicants for HUD'HUD’s competitive grants are required to certify that they will wil affirmatively further fair housing

as part of the grant application process.94

89 42 U.S.C. §3608(d), (e)(5). 90 See, for example, NAACP v. HUD, 817 F.2d 149, 155 (1st Cir. 1987) (“Finally, every court that has considered the question has held or stated that T itle VII imposes upon HUD an obligation to do more than simply refrain from discriminating (and from purposefully aiding discrimination by others)”).

91 Otero v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F.2d 1122, 1134 (2nd Cir. 1973). 92 NAACP v. HUD, 817 F.2d at 155. 93 Statutory requirements are at 42 U.S.C. §5304(b)(2) (CDBG) and 42 U.S.C. §1437c-1(d)(16) (Public Housing Authorities). Regulations require recipients of HOME, HOPWA, and ESG funds to affirmatively further fair housing as part of the consolidated planning process. See 24 C.F.R. §91.225, §91.325, and §91.425. Prior to the consolidated plan, recipients were required to affirmatively further fair housing as part of the Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy (P.L. 101-625).

94 See, for example, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, General Administrative Requirements and Term s for HUD Financial Assistance Awards, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/SPM/documents/GeneralAdministrationRequirementsand%20T ermsforHUDAssistanceAwards2.pdf .

Congressional Research Service

16

link to page 25 link to page 25 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Status of HUD AFFH Regulations Over the years, HUD has enforced the AFFH requirement first through guidance, and then

through regulations. HUD’s AFFH regulations have changed under the previous two presidential administrations. Prior to 2015, HUD had not issued regulations regarding AFFH, and instead provided guidance for HUD grantees to follow, cal ed an Analysis of Impediments (AI). In 2015, and again in 2020, HUD issued final rules governing the AFFH requirement. Below is a chronology of the AFFH rulemaking process, resulting in subsequent sets of regulations. (For

more information about the details of each policy, including AI and AFFH, see Appendix B.)

On July 16, 2015, HUD released an AFFH rule requiring states and communities

receiving HUD formula grants, as wel as PHAs, to affirmatively further fair

housing by conducting an Assessment of Fair Housing (AFH).95 The AFH process was implemented and enforced for approximately two years (2016-2017).

On January 5, 2018, HUD issued a notice stating that it would delay

implementation of the AFFH rule for local governments receiving more than $500,000 in CDBG funds until after October 31, 2020 (other jurisdictions were not yet required to submit AFHs).96 On May 23, 2018, HUD issued several more notices, the effect of which was to delay implementation of the 2015 rule indefinitely and revert to the former process of affirmatively furthering fair housing, the AI.97

On January 14, 2020, HUD released a proposed AFFH rule.98 Before the rule

could be finalized, HUD issued a different final rule, on August 7, 2020, entitled “Preserving Community and Neighborhood Choice.”99

The 2020 final rule states that HUD need not go through the notice and comment

process normal y required of rulemaking under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) due to an APA exception for matters “relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts.” The rule took effect on September 7, 2020.

On January 26, 2021, the Biden Administration issued a presidential

memorandum to HUD, directing the agency to “take al steps necessary to examine the effects of the August 7, 2020, rule entitled ‘Preserving Community

and Neighborhood Choice’ … including the effect that repealing the July 16,

95 Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing,” 80 Federal Register 42272, July 16, 2015, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-07-16/pdf/2015-17032.pdf.

96 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing: Extension of Deadline for Submission of Assessment of Fair Housing for Consolidated Plan Participants” 83 Federal Register 683-685, January 5, 2018, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-01-05/pdf/2018-00106.pdf. 97 See Appendix B, “HUD Decision to Delay Implementation of the 2015 AFFH Rule,” for citations to the three notices.

98 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing,” 85 Federal Register 2041-2061, January 14, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-01-14/pdf/2020-00234.pdf.

99 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Preserving Community and Neighborhood Choice,” 85 Federal Register 47899-47912, August 7, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-08-07/pdf/2020-16320.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

17

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

2015, rule entitled ‘Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing’ has had on HUD’s statutory duty to affirmatively further fair housing.”100

Limited English Proficiency In addition to administering fair housing programs and enforcing the law, FHEO oversees HUD’s compliance with limited English proficiency (LEP) requirements to ensure that persons with limited English proficiency have access to HUD programs. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

prohibits discrimination in federal y assisted programs on the basis of race, color, or national origin.101 One aspect of this prohibition has been ensuring that LEP individuals have access to federal programs (lack of access may be considered discrimination based on national origin).102 In 2000, President Clinton signed an executive order to require federal agencies to publish guidance for recipients of federal funding about ensuring that LEP individuals have access to programs and

services.103 In 2007, HUD issued final guidance to recipients of HUD funding about factors to

consider in meeting the needs of LEP clients.104

HUD’s guidance applies to al recipients of funding, including state and local governments,

PHAs, and for-profit and nonprofit housing providers, and also includes recipients that receive funds indirectly, such as subgrantees of state CDBG or HOME grants. The guidance directs recipients “to take reasonable steps to ensure meaningful access to their programs and activities by LEP persons.”105 The guidance lays out four factors for recipients to consider in determining how to serve LEP clients: (1) the number or proportion of LEP clients likely to be served or

encountered by the recipient, (2) how frequently eligible LEP persons are encountered by the recipient, (3) the nature and importance of the program or service in people’s lives, and (4) the

recipient’s resources and the cost of LEP services.106

Depending on a recipient’s analysis of these factors, it may opt to provide translation services on an as-needed basis by contracting with translation companies; or, if LEP clients are more frequent, it may decide to hire either a translator or bilingual staff. Recipients may also decide to have a wide number of documents translated or translate only the most critical documents. Enforcement of LEP requirements occurs through such avenues as compliance reviews or

investigating complaints.107

100 T he White House (President Biden), “Redressing Our Nation’s and the Federal Government’s History of Discriminatory Housing Practices and Policies,” presidential memorandum, 86 Federal Register 7487-7488, January 26, 2021, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-01-29/pdf/2021-02074.pdf.

101 42 U.S.C. §2000d. 102 See Department of Justice, “Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding T itle VI Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficiency Persons,” 67 Federal Register 41457, June 18, 2002, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2002-06-18/pdf/02-15207.pdf.

103 T he White House (President Clinton), “Improving Access to Services for Persons With Limited English Proficiency,” Executive Order 13166, 65 Federal Register 50121-50122, August 16, 2000, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2000-08-16/pdf/00-20938.pdf.

104 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Final Guidance to Federal Financial Assistance Recipients Regarding T itle VI Prohibition Against National Origin Discrimination Affecting Limited English Proficient Persons,” 72 Federal Register 2732, January 22, 2007, htt ps://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-03-16/pdf/E7-4794.pdf. 105 72 Federal Register, p. 2740. 106 Ibid. 107 Ibid., p. 2476. See also 28 C.F.R. §§42.106-42.107.

Congressional Research Service

18

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Congress set aside $400,000 for HUD to translate materials as part of the FY2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 110-161) and has continued to set aside funding since that time, ranging from $300,000 to $500,000. Funding has been used to translate HUD documents, provide translation services at HUD events, provide phone translations for cal ers to HUD, and acquire

technology, among other services.108

Section 3, Economic Opportunities for Low- and Very Low-Income Persons

Until November 30, 2020, FHEO oversaw HUD’s Section 3 program, through which Public and Indian Housing Authorities and grant recipients of HUD housing and community development construction or rehabilitation funds are to provide employment and training opportunities for low- and very low-income persons, particularly those residing in assisted housing. After release of new Section 3 regulations, on September 29, 2020, the offices overseeing HUD’s programs that are subject to Section 3 wil oversee the program’s requirements and FHEO is no longer involved.109

108 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, FY2015 Budget Justifications, p. D-8, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=fy15cj_fair_hsng_prog.pdf. 109 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Enhancing and Streamlining t he Implementation of Section 3 Requirements for Creating Economic Opportunities for Low- and Very Low-Income Persons and Eligible Businesses,” 85 Federal Register 61524, 61567, September 29, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/29/2020-19185/enhancing-and-streamlining-the-implementation-of-section-3-requirements-for-creating-economic.

Congressional Research Service

19

link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Appendix A. FHAP and FHIP Funding Table The table below shows FHAP and FHIP funding from FY1996 to the present.

Table A-1. Funding for FHAP and FHIP, FY1996-FY2021

(Dol ars in mil ions)

Fair Housing Assistance Program

Fair Housing Initiatives Program

(FHAP)

(FHIP)

President’s

President’s

Fiscal Year

Budget Request

Appropriation

Budget Request

Appropriation

1996

15.0

13.0

30.0

17.0

1997

15.0

15.0

18.0

15.0

1998

15.0

15.0

24.0

15.0

1999

23.0

16.5

29.0

23.5

2000

20.0

20.0

27.0

24.0

2001

21.0

22.0

29.0

23.9

2002

23.0

25.6

22.9

20.3

2003

25.6

25.5

20.3

20.1

2004

29.8

27.6

20.3

20.1

2005

27.1

26.3

20.7

19.8

2006

22.7

25.7

16.1

19.8

2007

24.8

25.7

19.8

19.8

2008

24.8

25.6

20.2

24.0

2009

25.0

25.5

26.0

27.5

2010

29.5

29.0

42.5

42.1a

2011

28.2

28.7

32.3

42.0

2012

29.5

28.0

42.5

42.5

2013

24.6

26.6

41.1

40.3

2014

24.6

24.1

44.1

40.1

2015

23.3

23.3

45.6

40.1

2016

23.3

24.3

45.6

39.2

2017

21.9

24.3

46.0

39.2

2018

24.3

23.9

39.2

39.6

2019

24.3

23.9

36.2

39.6

2020

24.3

25.0b

36.2

46.0b

2021

23.9

24.4

39.6

66.3c

Sources: HUD Congressional Budget Justifications for FY1996-FY2021; the explanatory materials accompanying the FY2020 Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, P.L. 116-94, at http://docs.house.gov/bil sthisweek/20191216/BILLS-116HR1865SA-JES-DIVISION-H.pdf; the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, P.L. 116-136; the explanatory materials accompanying the FY2021 Consolidated Appropriations

Congressional Research Service

20

The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities

Act (P.L. 116-260 ) at https://docs.house.gov/bil sthisweek/20201221/BILLS-116RCP68-JES-DIVISION-L.pdf; and the American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2). Notes: Amounts for the President’s FY2010 and FY2011 budget requests do not include funding proposed for the Transformation Initiative. a. The President’s budget request for FY2010 included additional FHIP funding to address mortgage fraud.