Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview

Changes from March 26, 2018 to February 4, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview

Contents

Summary

The Antideficiency Act (31 U.S.C. 1341-1342, 1511-1519) generally bars the obligation of funds in the absence of appropriations. Exceptions are made under the act, including for activities involving "the safety of human life or the protection of property." The interval during the fiscal year when appropriations for a particular project or activity are not enacted into law, either in the form of a regular appropriations act or a continuing resolution (CR), is referred to as a funding gap or funding lapse. Although funding gaps may occur at the start of the fiscal year, they may also occur any time a CR expires and another CR (or the regular appropriations bill) is not enacted immediately thereafter. Multiple funding gaps may occur within a fiscal year.

When a funding gap occurs, federal agencies are generally required to begin a shutdown of the affected projects and activities, which includes the prompt furlough of non-excepted personnel. The general practice of the federal government after the shutdown has ended has been to retroactively pay furloughed employees for the time they missed, as well as employees who were required to come to work.

Although a shutdown may be the result of a funding gap, the two events should be distinguished. This is because a funding gap may result in a total shutdown of all affected projects or activities in some instances but not others. For example, when funding gaps are of a short duration, agencies may not have enough time to complete a shutdown of affected projects and activities before funding is restored. In addition, the Office of Management and Budget has previously indicated that a shutdown of agency operations within the first day of the funding gap may be postponed if a resolution appears to be imminent.

Since FY1977, 1920 funding gaps occurred, ranging in duration from 1 day to 2134 full days. These funding gaps are listed in Table 1. About half of these funding gaps were brief (i.e., three days or less in duration). Notably, many of the funding gaps that occurred during this period do not appear to have resulted in a "shutdown." Prior to the issuance of the opinions in 1980 and early 1981 by then-Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti, while agencies tended to curtail some operations in response to a funding gap, they often "continued to operate during periods of expired funding." In addition, some of the funding gaps after the Civiletti opinions did not result in a completion of shutdown operations due to both the funding gap's short duration and an expectation that appropriations would soon be enacted. Some of the funding gaps during this period, however, did have a broader impact on affected government operations, even if only for a matter of hours.

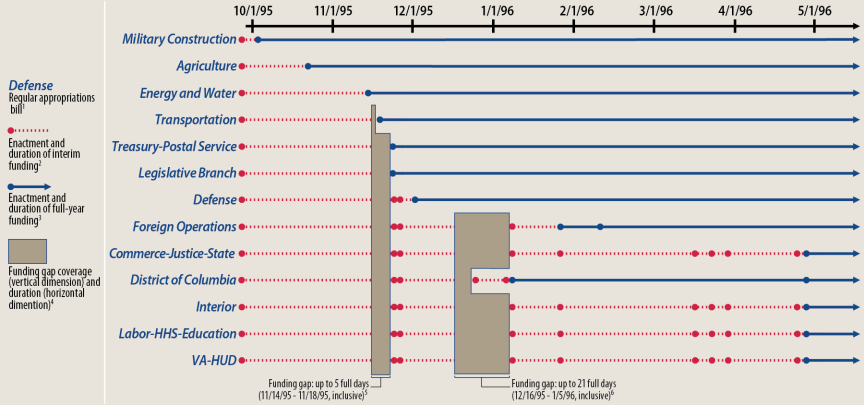

Two of the most recent funding gaps occurred in FY1996, amounting to 5 days and 21 days. The chronology of regular and continuing appropriations enacted during FY1996 is illustrated in Figure 1.

At the beginning of FY2014 (October 1, 2013), none of the regular appropriations bills had been enacted, so a government-wide funding gap occurred. It concluded on October 17, 2013, after lasting 16 full days. During FY2018, there was a funding gap when a CR covering all of the regular appropriations bills expired on January 19, 2018. It concluded on January 22, 2018, after lasting two full days.

The most recent funding gap occurred during FY2018FY2019, when a CR covering all of the federal agencies and activities funded in 7 of the 12 regular appropriations bills expired on January 19December 21, 2018. It concluded on January 22, 201825, 2019, after lasting two34 full days.

For a general discussion of federal government shutdowns, see CRS Report RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]Clinton T. Brass.

Background

The routine activities of most federal agencies are funded annually by one or more of the regular appropriations acts. When action on the regular appropriations acts is delayed, a continuing appropriations act, also sometimes referred to as a continuing resolution or CR, may be used to provide interim budget authority.1

Since FY1952the federal fiscal year was shifted to October 1-September 30 beginning with FY1977, all of the regular appropriations acts have been enacted by the beginning of the fiscal year in only four instances (FY1977, FY1989, FY1995, and FY1997), andalthough CRs were not needed for interim funding in only for threeone of these fiscal years. CRs were enacted for FY1977 but only to fund certain unauthorized programs whose funding had been droppedexcluded from the regular appropriations acts.2 Further, no CRs were enacted for FY1953, even though all but one of the regular appropriations was enacted after the start of the fiscal year.3

The Antideficiency Act (31 U.S.C. 1341-1342, 1511-1519) generally bars the obligation or expenditure of federal funds in the absence of appropriations.4 Exceptions under the act include activities involving "the safety of human life or the protection of property."53 The interval during thea fiscal year when appropriations for a particular project or activity are not enacted into law, either in the form of a regular appropriations act or a CR, is referred to as a funding gap or funding lapse.4.6 Although funding gaps may occur at the start of the fiscal year, they may also occur any time a CR expires and another CR (or the relevant regular appropriations bill) is not enacted immediately thereafter. Multiple funding gaps may occur within a fiscal year.

In 1980 and early 1981, then-Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti issued opinions The Civiletti letters state that, in general, the Antideficiency Act requires that if Congress has enacted no appropriation beyond a specified period, the agency may make no contracts and obligate no further funds except as "authorized by law." In addition, because no statute generally permits federal agencies to incur obligations without appropriations for the pay of employees, the Antideficiency Act does not, in general, authorize agencies to employ the services of their employees upon a lapse in appropriations, but it does permit agencies to fulfill certain legal obligations connected with the orderly termination of agency operations. The second letter, from January 1981, discusses the more complex problem of interpretation presented with respect to obligational authorities that are "authorized by law" but not manifested in appropriations acts. In a few cases, Congress has expressly authorized agencies to incur obligations without regard to available appropriations. More often, it is necessary to inquire under what circumstances statutes that vest particular functions in government agencies imply authority to create obligations for the accomplishment of those functions despite a lack of current appropriations. It is under this guidance that exceptions may be made for activities involving "the safety of human life or the protection of property."6clarifying the need for the federal government to begin terminating regular activities upon the occurrence of a funding gap.7 As a consequence of these more strict guidelines, when a funding gap occurs, executive agencies begin a shutdown of the affected projects and activities, which includes the promptin two letters to the President that have been put into effect through guidance provided to federal agencies under various Office of Management and Budget (OMB) circulars clarifying the limits of federal government activities upon the occurrence of a funding gap.5

8

Under current practice, although a shutdown may be the result of a funding gap, the two events should be distinguished. This is because a funding gap may result in a shutdown of all affected projects or activities in some instances but not in others. For example, when a funding gap is of a short duration, agencies may not have enough time to complete a shutdown of affected projects and activities before funding is restored. In addition, the Office of Management and Budget has previously indicated that a shutdown of agency operations within the first day of a funding gap may be postponed if it appears that an additional CR or regular appropriations act is likely to be enacted that same day.9

To avoid funding gaps, proposals have previously been offered to establish an "automatic continuing resolution" (ACR) that would provide a fallback source of funding authority for activities, at a specified formula or level, in the event that timely enactment of appropriations is disrupted. The fundingFunding would become available automatically and remain available as long as needed so that a funding gap would not occur. Although the House and Senate have considered ACR proposals in the past, none has been enacted into law on a permanent basis.

Funding Gaps Since FY1977

As illustrated in Table 1, there have been 1920 funding gaps since FY1977.109 The enactment of a CR on the day after the budget authority in the previous CR expired, which has occurred oftenin several instances, is not counted in this report as involving a funding gap because there was no full day for which there was no available budget authority. For example, between FY2000 and FY2018, "next-day" CRs were enacted on 21 occasions.

Almost allA majority of the funding gaps occurred between FY1977 and FY1995. During this period of 19 fiscal years, 15 funding gaps occurred.

Multiple funding gaps have occurred during a single fiscal year in four instances: (1) three gaps covering a total of 28 days in FY1978, (2) two gaps covering a total of 4four days in FY1983, (3) two gaps covering a total of 3three days in FY1985, and (4) two gaps covering a total of 26 days in FY1996.

days in FY1985, and (4) two gaps covering a total of 26 days in FY1996.

Seven of the funding gaps commenced with the beginning of the fiscal year on October 1. The remaining 11 funding gaps occurred at least more than one day after the fiscal year had begun. Ten of the funding gaps ended in October, four ended in November, three ended in December, and one ended in January.

Funding gaps have ranged in duration from 1 to 21 full days. Six of the eight lengthiest funding gaps, lasting between 8 days and 17 days, occurred between FY1977 and FY1980—before the Civiletti opinions were issued in 1980 and early 1981. After the issuance of these opinions, the duration of funding gaps in general shortened considerably, typically ranging from one day to three days. Of these, most occurred over a weekend.

|

Fiscal Year |

Final Date of Budget Authoritya |

Full Day(s) of Gapb |

Date Gap Terminatedc |

|

1977 |

Thursday, 09/30/76 |

10 |

Monday, 10/11/76 |

|

1978 |

Friday, 09/30/77 |

12 |

Thursday, 10/13/77 |

|

Monday, 10/31/77 |

8 |

Wednesday, 11/09/77 |

|

|

Wednesday, 11/30/77 |

8 |

Friday, 12/09/77 |

|

|

1979 |

Saturday, 09/30/78 |

17 |

Wednesday, 10/18/78 |

|

1980 |

Sunday, 09/30/79 |

11 |

Friday, 10/12/79 |

|

1982 |

Friday, 11/20/81 |

2 |

Monday, 11/23/81 |

|

1983 |

Thursday, 09/30/82 |

1 |

Saturday, 10/02/82 |

|

Friday, 12/17/82 |

3 |

Tuesday, 12/21/82 |

|

|

1984 |

Thursday, 11/10/83 |

3 |

Monday, 11/14/83 |

|

1985 |

Sunday, 09/30/84 |

2 |

Wednesday, 10/03/84 |

|

Wednesday, 10/03/84 |

1 |

Friday, 10/05/84 |

|

|

1987 |

Thursday, 10/16/86 |

1 |

Saturday, 10/18/86 |

|

1988 |

Friday, 12/18/87 |

1 |

Sunday, 12/20/87 |

|

1991 |

Friday, 10/05/90 |

3 |

Tuesday, 10/09/90 |

|

1996 |

Monday, 11/13/95 |

5 |

Sunday, 11/19/95 |

|

Friday, 12/15/95 |

21 |

Saturday, 01/06/96 |

|

|

2014 |

Monday, 09/30/13 |

16 |

Thursday, 10/17/13 |

|

2018 |

Friday, 01/19/18 |

2 |

Monday, 1/22/18 |

2019 Friday, 12/21/18 34 Friday, 1/25/19Source: Compiled by CRS with data from the Legislative Information System of the U.S. Congress

Source: Compiled by CRS.

Notes:

a. Budget authority expired at the end of the date indicated. For example, for the first FY1996 funding gap, budget authority expired at the end of the day on Monday, November 13, 1995, and the funding gap of five full days commenced on Tuesday, November 14, 1995. The enactment of a CR on the day after the previous CR expired, which has occurred oftenon several occasions, is not counted as involving a funding gap.

b. Full days are counted as beginning after because there was no full day for which there was no available budget authority.

b. Full days are counted as the number of days for which no budget authority was available, beginning after the final day on which budget authority was available and ending the day before the gap terminatedbefore new budget authority was enacted. For example, for the first FY1996 funding gap, the full days of the gap were from November 14, 1995, through November 18, 1995, for a total of five full days.

c. Gap terminated due toby the enactment of a continuing resolution or one or more regular appropriations acts.

Seven of the funding gaps commenced with the beginning of the fiscal year on October 1. The remaining 13 funding gaps occurred at least more than one day after the fiscal year had begun. Ten of the funding gaps ended in October, four ended in November, three ended in December, and three ended in January. Funding gaps have ranged in duration from 1 to 34 full days. Six of the 8 lengthiest funding gaps, lasting between 8 days and 17 days, occurred between FY1977 and FY1980—before the Civiletti opinions were issued and for which there was no government shutdown. Between 1980 and 1990, the duration of funding gaps was generally shorter, typically ranging from one day to three days. In most cases these occurred over a weekend with only limited impact in the form of government shutdown activities. All obligations incurred in anticipation of the appropriations and authority provided in this joint resolution are hereby ratified and confirmed if otherwise in accordance with the provisions of the joint resolution.11Notably, many of the funding gaps that occurred since FY1977 do not appear to have resulted in a "shutdown." Prior to the issuance of the Civiletti opinions, the expectation was that agencies would not shut down during a funding gap.10 Continuing resolutions typically included language ratifying obligations incurred prior to the resolution's enactment. For example, the first CR for FY1980 provided

1112 In addition, some of the funding gaps after the Civiletti opinions did not result in a completion of shutdown operations due to both a funding gap's short duration and an expectation that appropriations would soon be enacted. For example, during the three-day FY1984 funding gap, "no disruption to government services" reportedly occurred, due to both the three-day holiday weekend and the expectation that the President would soon sign into law appropriations passed by the House and Senate during that weekend.1213

Some of the funding gaps during this period, however, did have a broader impact on affected government operations, even if only for a matter of hours. For example, in response to the one-day funding gap that occurred on October 4, 1984, a furlough of non-excepted personnel for part of that day was reportedly implemented.1314 It should be noted that when most of these funding gaps occurred, one or more regular appropriations measures had been enacted, so any effects were not felt government-wide. For example, the three funding gaps in FY1978 were limited to activities funded in the Departments of Labor and Health, Education, and Welfare Appropriations Act. Similarly, 8 of 13 regular appropriations acts had been enacted prior to the three-day funding gap in FY1984.

The most recent funding gaps—two in FY1996, one in FY2014, one in FY2018, and one in FY2018FY2019—all resulted in a widespread cessation of non-excepted activities and furlough of associated personnel. The legislative history and the impact of these funding gaps are summarized below.

FY1996

The two FY1996 funding gaps occurred between November 13 and 19, 1995, and December 15, 1995, through January 6, 1996. The chronology of regular and continuing appropriations enacted during that fiscal year is illustrated in Figure 1. In the lead-up to the first funding gap, only 3 out of the 13 regular appropriations acts had been signed into law,1415 and budget authority, which had been provided by a CR1516 since the start of the fiscal year, expired at the end of the day on November 13. On this same day, President Clinton vetoed a CR1617 that would have extended budget authority through December 1, 1995, because of the Medicare premium increases contained within the measure.1718 The ensuing funding gap reportedly resulted in the furlough of an estimated 800,000 federal workers.1819 After five days, a deal was reached to end the shutdown and extend funding through December 15.1920 Agencies that had been zeroed out in pending appropriations bills were funded at a rate of 75% of FY1995 budget authority. All other agencies were funded at the lower of the House- or Senate-passed level of funding contained in the FY1996 full-year appropriations bills. The CR also included an agreement between President Clinton and Congress regarding future negotiations to lower the budget deficit within seven years.20

|

|

Source: CRS Report R42647, Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Recent Practices, by Notes: (1) In FY1996, the annual appropriations process anticipated the enactment of 13 "regular appropriations" bills. (2) Interim funding was provided through 13 continuing resolutions (CRs) of varying coverage and duration. For a list of these CRs and their enactment dates, see Table 4 in CRS Report R42647, Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Recent Practices, by (3) Full-year funding was provided through eight regular appropriations acts (P.L. 104-32, P.L. 104-37, P.L. 104-46, P.L. 104-50, P.L. 104-52, P.L. 104-53, P.L. 104-61, and P.L. 104-107), two full-year CRs (P.L. 104-92 and P.L. 104-99), and an omnibus appropriations act (P.L. 104-134). For Foreign Operations and District of Columbia, although full-year funding was initially provided in CRs, final action on annual appropriations (P.L. 104-107 and P.L. 104-134) superseded that funding. (4) The "coverage" of the funding gap refers to those regular appropriations bills that had not been enacted during all or some of the days during which the funding gap occurred. The "duration" of the funding gap is calculated here as the number of full days affected by the lapse in funding. Full days are counted as beginning after the final day on which budget authority was available and ending the day before funding resumed. (5) Interim funding was enacted late in the day on November 19, 1995 (P.L. 104-54). As a consequence, in many instances agency operations may not have restarted until the following day. (6) Three interim funding measures included full-year funding for certain activities (P.L. 104-69, P.L. 104-91, and P.L. 104-92). However, this provision of agency- or program-specific, full-year funding is not reflected in the figure, which focuses on the enactment of entire regular appropriations bills. |

During the first FY1996 funding gap and prior to the second one, an additional four regular appropriations measures were enacted, and three others were vetoed.2122 The negotiations on the six remaining bills were unsuccessful before the budget authority provided in the CR expired at the end of the day on December 15, 1995.2223 Reportedly, about 280,000 executive branch employees were furloughed during the funding gap between December 15, 1995, and January 6, 1996.2324 A CR to provide benefits for veterans and welfare recipients and to keep the District of Columbia government operating was passed and signed into law on December 22, 1995.2425 The shutdown officially ended on January 6, 1996, when the first of a series of CRs to reopen affected agencies and provide budget authority through January 26, 1996,2526 was enacted.26

FY2014

This funding gap commenced at the beginning of FY2014 on October 1, 2013. None of the 12 regular appropriations bills for FY2014 was enacted prior to the beginning of the funding gap. In addition, as of the beginning of the fiscal year, an interimNor had a CR to provide budget authority for the projects and activities covered by those 12 bills was also notbeen enacted. On September 30, however, an ACR was enacted to cover FY2014 pay and allowances for (1) certain members of the Armed Forces, (2) certain Department of Defense (DOD) civilian personnel, and (3) other specified DOD and Department of Homeland Security contractors (H.R. 3210; P.L. 113-39, 113th Congress).

At the beginning of this 16-day funding gap, more than 800,000 executive branch employees were reportedly furloughed.2728 This number was reduced during the course of the funding gap due to the implementation of P.L. 113-39 and other redeterminations of whether certain employees were excepted from furlough.2829 Prior to the resolution of the funding gap, congressional action on appropriations was generally limited to a number of narrow CRs to provide funding for certain programs or classes of individuals.2930 Of these, only the Department of Defense Survivor Benefits Continuing Appropriations Resolution of 2014 (H.J.Res. 91; P.L. 113-44) was enacted into law.

On October 16, 2013, the Senate passed H.R. 2775, which had been previously passed by the House on September 12, with an amendment. This amendment, in part, provided interim continuing appropriations for the previous year's programs and activities through January 15, 2014. Later that same day, the House agreed to the Senate amendment to H.R. 2775. The CR was signed into law on October 17, 2013 (P.L. 113-46), thus ending the funding gap.

FY2018

At the beginning of FY2018, none of the 12 regular appropriations bills had been enacted, so the federal government operated under a series of CRs. The first, P.L. 115-56, provided government-wide funding through December 8, 2017. The second, P.L. 115-90, extended funding through December 22, and the third, P.L. 115-96, extended it through January 19, 2018. In the absence of agreement on legislation that would further extend the period of these CRs, however, a funding gap began with the expiration of P.L. 115-96 at midnight on January 19. A furlough of federal personnel began over the weekend and continued through Monday of the next week, ending with enactment of a fourth CR, P.L. 115-120, on January 22.

FY2019At the beginning of FY2019, 5 of the 12 regular appropriations bills had been enacted in two consolidated appropriations bills.31 The remaining seven regular appropriations bills were funded under two CRs.32 The first CR, P.L. 115-245, provided funding through December 7, 2018. The second CR, P.L. 115-298, extended funding through December 21, 2018. When no agreement was reached on legislation to further extend the period of these CRs, a funding gap began with the expiration of P.L. 115-298 at midnight on December 21, 2018. Because of this funding gap, federal agencies and activities funded in these seven regular appropriations bills were required to shut down.

The funding gap ended when a CR, P.L. 116-5, was signed into law on January 25, 2019, which ended the partial government shutdown and allowed government departments and agencies to reopen. The funding gap lasted 34 full days.

Author Contact Information

James V. SaturnoAuthor Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report is based on work published in prior CRS Reports by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]Robert Keith and Jessica Tollestrup.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For a discussion of CRs generally, see CRS Report R42647, Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Recent Practices, by |

|||

| 2. |

P.L. 94-473 made continuing appropriations through March 31, 1977. P.L. 95-16 extended the date of the budget authority provided in P.L. 94-473 through April 30, 1977. |

|||

| 3. |

| |||

| 4. |

The Antideficiency Act is discussed in CRS Report RL30795, General Management Laws: A Compendium, by [author name scrubbed] et al. In addition, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) provides information about the act online at http://www.gao.gov/ada/antideficiency.htm. |

|||

| 5. |

See 31 U.S.C. §1342. During a funding gap, personnel and related activities that are determined to be necessary for the "the safety of human life or the protection of property," or fall under other allowable exceptions, are referred to as "excepted." Under Department of Justice guidance (discussed later in this report), agencies may incur obligations ahead of appropriations for these "excepted" purposes. |

|||

|

In most cases, funding provided in regular appropriations acts is available to be obligated only |

||||

|

The text of the opinions is included in Appendices IV and VIII to the GAO report Funding Gaps Jeopardize Federal Government Operations, PAD-81-31, March 3, 1981. |

||||

|

|

7.

See 31 U.S.C. §1342. During a funding gap, personnel and related activities that are determined to be necessary for the "the safety of human life or the protection of property," or fall under other allowable exceptions, are referred to as "excepted." In the annually revised Circular No. A-11, OMB provides guidance to executive branch agencies on how to prepare for and operate during a funding gap, including how to determine "excepted" purposes for which agencies may incur obligations ahead of appropriations. |

For a discussion of federal government shutdowns, see CRS Report RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects, coordinated by |

||

|

See, for example, |

||||

|

FY1977 marked the first full implementation of the congressional budget process established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, which moved the beginning of the fiscal year to October 1. |

||||

|

|

For example, Senator Warren Magnusen, chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, inserted into the Congressional Record guidelines provided within GAO for FY1980, stating that they believed that it was "not the intent of Congress that GAO close down until an appropriate measure has been passed" and that, as a consequence, they should restrain FY1980 obligations to "only those essential to maintain day-to-day operations." Congressional Record, October 1, 1979, p. 26974. 11.

|

|

P.L. 96-86, §117. |

GAO, Funding Gaps Jeopardize Federal Government Operations, PAD-81-31, March 3, 1981, p. 2. GAO further stated, "Short of telling employees not to show up for work, Federal officials have responded to gaps by cutting or postponing all non-essential obligations—particular personnel actions, travel, and the award of new contracts—in an attempt to continue the operations of programs for which they are responsible." Media reports related to funding gaps prior to FY1982 also suggest that little or no shutdown occurred. See, for example, Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Continued Funding, 1977," vol. XXXII, pp. 789-790; Washington Post, "Payroll Crisis Is Staved Off and HEW, Labor," October 14, 1977; National Journal, "Congress Fails to Make Appropriations Deadline," October 8, 1977; Congressional Quarterly Weekly, "Abortion Agreement Ends Funding Deadlock," December 10, 1977, p. 2547; Washington Post, "Funding Lags as Fiscal Year Begins," October 3, 1978; "and Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Pay, Abortion Issues Delay Hill Funding Bills," vol. XXXV, pp. 270-277. |

|

Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Congress Clears 2nd Continuing Resolution," vol. XXXIX, 1983, pp. 528-531. |

||||

|

For further information, see Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Last-Minute Money Bill Was Largest Ever," vol. XXXX pp. 444-447; Robert Pear, "Senate Works Past Deadline on Catchall Government Spending Bill," New York Times, October 4, 1984, p. A29; and Monica Borkowski, "Looking Back; Previous Government Shutdowns," New York Times, November 11, 1995. |

||||

|

The Military Construction Appropriations Act, H.R. 1817 (P.L. 104-32), was enacted on October 3, 1995. The Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, |

||||

|

H.J.Res. 115 (104th Cong.). |

||||

|

William J. Clinton, "Message to the House of Representatives Returning Without Approval Continuing Resolution Legislation," November 13, 1995, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1995, Book 2, July 1 to December 31, 1995, p. 1755. See also CQ Today, "Clinton Vetoes Stopgap Bill to Keep Federal Government Open," November 14, 1995. |

||||

|

For example, see U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, Subcommittee on Civil Service, Government Shutdown I: What's Essential? hearings, 104th Cong., 1st sess., December 6 and 14, 1995 (Washington: GPO, 1997), pp. 6 and 265. |

||||

|

As provided in 2 CRs: H.J.Res. 123 (P.L. 104-54) and H.J.Res. 122 (P.L. 104-56). |

||||

|

For a summary of the first FY1996 funding gap and government shutdown, see Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Overview: Government Shuts Down Twice Due to Lack of Funding," 104th Cong., 1st sess. (1995), vol. LI, pp. 11-3 through 11-6; CQ Weekly, "Special Report—Budget Showdown: Day by Day," November 18, 1995. |

||||

|

The Department of Transportation and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, H.R. 2002 (P.L. 104-50), was enacted on November 15, 1995. The Treasury, Postal Service, and General Government Appropriations Act, H.R. 2020 (P.L. 104-52), was enacted on November 19, 1995. The Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, H.R. 2492 (P.L. 104-53), was enacted on November 19, 1995. The Department of Defense Appropriations Act, H.R. 2126 (P.L. 104-61), was enacted on December 1, 1995. The Department of Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, H.R. 1977 (104th Cong.), was vetoed on December 18, 1995. The Department of Veterans Affairs and Housing and Urban Development, and Independent Agencies Appropriations Act, H.R. 2099 (104th Cong.), was vetoed on December 18, 1995. The Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, H.R. 2076 (104th Cong.), was vetoed on December 19, 1995. |

||||

|

As of the end of the day on December 15, 1995, the six regular appropriations bills that had yet to be enacted were the (1) Department of Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act; (2) Department of Veterans Affairs and Housing and Urban Development, and Independent Agencies Appropriations Act; (3) Departments of Commerce, Justice, State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act; (4) Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act; (5) Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act; and (6) District of Columbia Appropriations Act. |

||||

|

For further information on the effects of the second FY1996 funding gap, see Dan Moran and Stephen Barr, "When Shutdown Hit Home Ports, GOP Cutters Trimmed Their Sails," Washington Post, January 8, 1996. |

||||

|

H.J.Res. 134 (P.L. 104-94). H.R. 1358 (P.L. 104-91) and H.R. 1643 (P.L. 104-92) were also enacted on January 6. These two CRs provided budget authority for some federal government activities until the end of FY1996. |

||||

|

For a summary of the second FY1996 funding gap and government shutdown, see Congressional Quarterly Almanac, "Overview: Government Shuts down Twice Due to Lack of Funding," 104th Cong., 1st sess. (1995), vol. LI, pp. 11-3 through 11-6; CQ Weekly, "Funding Expires Again in Budget Stalemate," December 23, 1995; CQ Today, "Congress Clears Bills to Reopen Government," January 8, 1996. |

||||

|

See, for example, Wall Street Journal, "More Than 800,000 Federal Workers Are Furloughed," October 1, 2013. Estimates in this and other media reports were based upon the totals provided by agencies in their contingency plans, which are available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/contingency-plans. These totals do not include legislative or judicial branch employees. |

||||

|

See, for example, Washington Post, "Pentagon Will Order Almost All Furloughed Civilian Employees Back to Work," October 5, 2013; and Washington Post, "Agencies Increasingly Calling Back Furloughed Workers," October 10, 2013. |

||||

|

These CRs included H.J.Res. 70, H.J.Res. 71, H.J.Res. 72, H.J.Res. 73, H.J.Res. 75, H.J.Res. 76, H.J.Res. 77, H.J.Res. 79, H.J.Res. 80, H.J.Res. 82, H.J.Res. 83, H.J.Res. 84, H.J.Res. 85, H.J.Res. 89, H.J.Res. 90, H.J.Res. 91, and H.R. 3230. |

||||

| 31. |

P.L. 115-245 provided funding for FY2019 for the Department of Defense and the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education; P.L. 115-244 provided funding for Energy and Water Development, Legislative Branch, and Military Constructions and Veterans Affairs. |

|||

| 32. |

Department of Agriculture and Related Agencies; Departments of Commerce and Justice, Science and Related Agencies; Financial Service and General Government; Department of Homeland Security; Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies; Department of State and Foreign Operations; and Departments of Transportation and Housing and Urban Development. |