Israel: Major Issues and U.S. Relations

Changes from December 22, 2017 to February 12, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- U.S.-Israel Relations:

Current StatusKey Concerns

- Israeli-Palestinian Issues

Jerusalem:Overview- Assessment

- Jerusalem

- New U.S. Stance

Reactions and PolicyNew U.S. Stance andImplications- Settlements

- Regional Security Issues

- Iran and Its Allies

- Lebanon-Syria Border Area and Hezbollah

- Palestinians

- Domestic Israeli Developments

U.S.-Israel Relations: Current Status

For decadesKey Concerns

Since the Cold War, strong bilateral relations have fueled and reinforced significant U.S.-Israel cooperation in many areas, including regional security. Nonetheless, at various points throughout the relationship, U.S. and Israeli policies have diverged on some important issues. Significant differences regarding regional issues—notably Iran and the Palestinians—arose or intensified during the Obama Administration.1 Since President Donald Trump's inauguration in January 2017, he and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu have discussed ways "to advance and strengthen the U.S.-Israel special relationship, and security and stability in the Middle East."2

A number of issues have significant implications for U.S.-Israel relations. They include

Various controversies regardingIsraeli-Palestinian issues anddiplomatic efforts to addresscontroversies surrounding them, including President Trump's December 2017 recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announced plan to relocate the U.S. embassy in Israel there.- Regional security issues (including those involving Iran, Hezbollah,

Syria, and Hamasand Syria) and U.S.-Israel cooperation. - Israeli domestic political issues, including an ongoing criminal investigation of Prime Minister Netanyahu.

For background information and analysis on these and other topics, including aid, arms sales, and missile defense cooperation, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R44281, Israel and the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, coordinated by [author name scrubbed].

|

|

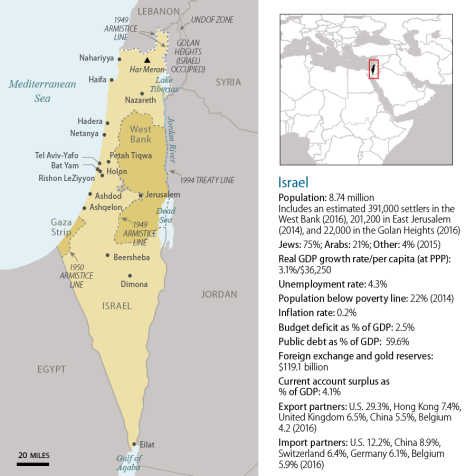

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed] using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2013); the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency GeoNames Database (2015); DeLorme (2014). Fact information from CIA, The World Factbook; Economist Intelligence Unit; IMF World Outlook Database; Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. All numbers are estimates and as of 2017 unless specified. Notes: United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) withdrew to Israeli-controlled territory in the Golan Heights in September 2014. The West Bank is Israeli-administered with current status subject to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiation. The status of the Gaza Strip is a final status issue to be resolved through negotiations. Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative. |

Israeli-Palestinian Issues

President Trump has stated aspirations to help broker a final-status Israeli-Palestinian agreement as the "ultimate deal." The President's advisors on Israeli issues include his senior advisor Jared Kushner (who is also his son-in-law), special envoy Jason Greenblatt, and U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman.3 Various political developments during 2017 (some of which are discussed below) have raised questions about whether and when a new U.S.-backed diplomatic initiative might surface. For example, some of President Trump's statements have fueled public speculation about the level of his commitment to a negotiated "two-state solution," a conflict-ending outcome that U.S. policy has largely advocated since the Israeli-Palestinian peace process began in the 1990s.

A number of aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have remained relatively constant in recent years. There has been little or no change in the gaps between Israeli and Palestinian positions on key issues of dispute since the last round of direct, U.S.-brokered talks broke down in April 2014. Additionally, Israel maintains overarching control of the security environment in Israel and the West Bank. Palestinians have been divided since 2007 between a Palestinian Authority (PA) administration with limited self-rule in specified West Bank urban areas—led by the Fatah movement and PA President Abbas—and Hamas control in the Gaza Strip. The Palestinians also face major questions regarding future leadership.4

In late 2017, the leading Palestinian factions took tentative steps toward more unified rule. In October, Fatah and Hamas reached an Egyptian-mediated agreement aimed at allowing the Fatah-led PA greater administrative control over Gaza.5 The PA gained at least nominal control of Gaza's border crossings with Israel and Egypt in November, but a larger handover of control has been delayed since early December. It is unclear whether this handover will take place, or whether the unity agreement—like similar agreements since 2007—will remain unimplemented.6 The question appears to center on Hamas's willingness to cede control of security in Gaza.7 PA President Abbas has maintained that he will not accept a situation where PA control is undermined by Hamas's militia.8

Since President Trump took office, he and officials from his Administration have expressed desires to broker a final-status Israeli-Palestinian agreement. Many of their statements, however, have raised questions about whether and when a new U.S.-backed diplomatic initiative to pursue that goal might surface, as well as broader questions about the U.S. role in the peace process.1 In December, President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announced his intention to relocate the U.S. embassy there from Tel Aviv. In response, Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas publicly rejected U.S. sponsorship of the peace process.2 Many other countries opposed President Trump's statements on Jerusalem. This opposition was reflected in December action at the United Nations (see "Jerusalem" below). These U.S. steps have changed the context for Israeli and Palestinian discussions on their respective political priorities. These discussions, in turn, have influenced Administration decisions to reduce or delay aid to the Palestinians. Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and other Israeli officials generally have welcomed Trump Administration actions emphasizing Israel's connection with Jerusalem. Some commentators assert that such developments may be emboldening various Israeli leaders to expand settlement building in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, and to seek greater Israeli control over areas whose status was previously reserved for negotiation.3 However, some prominent Israeli figures have speculated that the Administration might seek concessions from Israel in return for actions that appear to benefit Israel.4 While Netanyahu may be encouraging Administration rhetoric that threatens to reduce or halt aid to Palestinians under certain conditions,5 other Israelis have expressed concern that sudden or total aid cutoffs to the Palestinians could destabilize the Gaza Strip or the broader region.6 Israeli security officials are supposedly contemplating sending food and medicine to Gaza to prevent the difficult humanitarian situation from "spiraling into violence."7 PLO Chairman Abbas reportedly has refused to engage with U.S. officials "charged with the political process,"8 and Palestinian leaders are discussing political and diplomatic alternatives. Citing alleged U.S. bias favoring Israel, Palestinian leaders are seeking to counteract U.S. influence on the peace process by increasing the involvement of other actors like the European Union and Russia.9 In a January speech, Abbas accused Israel of "killing" the peace process and advocated greater unity between Hamas-controlled Gaza and the Palestinians over whom Abbas (and his Fatah faction) presides in the West Bank. Abbas also made remarks calling Israel "a colonialist project that is not related to Judaism."10 The Palestinian Central Council (a PLO advisory body) recommended that the PLO suspend its recognition of Israel, stop its security coordination with Israel (a suggestion the Council also made in 2015), and struggle "in all forms" against Israeli occupation.11 To date, Abbas has not suspended recognition of Israel or security cooperation with it. Speculation continues about possible Palestinian international initiatives aimed at pressuring Israel or bolstering global recognition of Palestinian statehood.12

Observers debate how the President's December decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announce plans for moving the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem (discussed below) might complicate any attempt to relaunch Israeli-Palestinian talks in 2018.9 Some commentators surmise that the Administration probably expects leaders from Arab states (such as Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Egypt) to continue their support for a U.S.-led peace process, despite their initial negative reactions to the President's decision in public, because of their widely reported interest in working with the United States and Israel to counter Iran's influence in the region.10Notes: According to the Department of State: (1) The West Bank is Israeli occupied with current status subject to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiation. (2) The status of the Gaza Strip is a final status issue to be resolved through negotiations. (3) The United States recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in 2017 without taking a position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty. (4) Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative. See https://www.state.gov/p/nea/ci/is/.

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed] using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2013); the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency GeoNames Database (2015); DeLorme (2014). Fact information from CIA, The World Factbook; Economist Intelligence Unit; IMF World Outlook Database; Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. All numbers are estimates and as of 2017 unless specified.

Israeli-Palestinian Issues

Overview

1118

Palestinians appear to view their national aspirations as being undermined by the prospect of indefinite Israeli control over large swaths of the West Bank,22 and by Netanyahu's insistence that whatever sovereignty Palestinians achieve will be limited in scope.23 Abbas has voiced concern about the possible removal of core issues of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—namely, Jerusalem's status and Palestinian refugees' rights—from the negotiating table.24 Reportedly, the Administration has suggested addressing the Palestinian demand for a capital in East Jerusalem by having the capital in a West Bank neighborhood (Abu Dis) outside of Jerusalem's current municipal boundaries.25Whether Arab state leaders will move toward or away from supporting the peace process may partly depend on Arab state positions on a resumption of peace negotiations could depend on a number of factors. Their stances may partly hinge on Arab public opinion regarding Jerusalem, Israeli settlements, and other controversial topics. TheseArab leaders' stancesviews could also depend on the extent to whichhow much they believe that coordination with the United States and Israel to counteragainst Iran is tied to cooperation on the peace process.19 A separate issue is whether Arab state support would be sufficient to engage Palestinian officials in a new diplomatic initiative, given the difficulties with past initiatives, questions regarding Palestinian leadership overall,convince Palestinian leaders to engage in negotiations despite ongoing political controversies with the United States and Israel, difficulties with past peace initiatives, questions regarding Abbas's continued leadership,20 and divided rule in the West Bank and Gaza.21

and divided rule in the West Bank and Gaza.12

The implications of the President's Jerusalem decision for the U.S. and Israeli approaches to Palestinian issues remain in question. One article speculated that leaders from Israel's political right would feel emboldened to pressure Netanyahu to boost Israelis' presence in Jerusalem and the West Bank. Yet, the same article reported that some Israelis anticipate possible demands from President Trump for future Israeli concessions to the Palestinians.13

Possible presidential or legislative initiatives could address

- U.S. aid to Israel and the Palestinians.

- U.S. policy on a two-state solution and other issues of dispute (including security, borders, settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the status of Jerusalem).

- U.S. contributions to and participation in certain United Nations and other international bodies.14

- U.S. approaches to other regional and international actors that have roles in Israeli-Palestinian issues.

Jerusalem: New U.S. Stance and Implications

Via a presidential document that he signed on December 6, 2017, President Trump proclaimed "that the United States recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel and that the United States Embassy to Israel will be relocated to Jerusalem as soon as practicable."1526 A December deadline for presidential action under the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995 (P.L. 104-45) precipitated the timing of the President's decision.

Despite his proclamation on the planned embassy relocation, the President ultimately did sign a waiver (citing national security grounds) in response to the December deadline.16 So long as the embassy has not officially opened in Jerusalem, the waiver is required every six months under P.L. 104-45 to prevent a 50% limitation on spending from the general "Acquisition and Maintenance of Buildings Abroad" budget. This limitation would otherwise apply in the following fiscal year.27

In making his decision, President Trump departed from the decades-long U.S. executive branch practice of not recognizing Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem or any part of it.1728 The western part of Jerusalem that Israel has controlled since 1948 has served as the seat of its government since shortly after its founding as a state. Israel officially considers Jerusalem (including the eastern part it unilaterally annexed after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, while also expanding the city's municipal boundaries) to be its capital. In explaining the President's decision, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Satterfield said on December 10, "This step was recognition of simple reality."18

The President stated—in a December 6 speech accompanying his proclamation—that he was not taking a position on "specific boundaries of the Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem," and would continue to consider the city's final status to be subject to Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. On January 25, President Trump made additional remarks on Jerusalem while appearing with Prime Minister Netanyahu in Davos, Switzerland. The President said, "We took Jerusalem off the table, so we don't have to talk about it anymore," before telling Netanyahu, "You won one point [on Jerusalem], and you'll give up some points later on the negotiation, if it ever takes place."37 A few days later, the President's envoy on the peace process, Jason Greenblatt, said, "When President Trump made his historic decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, he was … absolutely clear that the United States has not prejudged any final status issues, including the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem."38 Israeli officials welcomed the President's decision on Jerusalem. In January 2018, the Knesset amended a Basic Law on Jerusalem to require a supermajority vote to transfer any area of Jerusalem to a foreign power. The action is largely symbolic because the law itself can be amended by a simple majority vote.39 As mentioned above, in response to the U.S. decision on Jerusalem, Palestinian leaders have publicly alleged U.S. bias favoring Israel and have rejected a peace process in which the United States is the sole mediator. 1933 Palestinians envisage East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state. The President did not explicitly mention Palestinian aspirations regarding Jerusalem. He called on all parties to maintain the "status quo" arrangement at holy sites, including the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif.20most of which are in East Jerusalem's Old City.34 Echoing past statements,2135 the President said that the United States would support a two-state solution if both sides agree to it. In mid-December, a senior Administration official was quoted as saying "we cannot imagine Israel would sign a peace agreement that didn't include the Western Wall."36

the President said that the United States would support a two-state solution if both sides agree to it.

|

Jordan and Jerusalem Perhaps more than any other Arab state, Jordan has a significant stake in any development affecting the status of Jerusalem. Jordan and its king, Abdullah II, maintain a custodial role—recognized by Israel and the Palestinians—over the Old City's Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif and its holy sites. This area is the third-holiest in Islam (after Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia). Also, Palestinians make up a large portion (probably a majority) of Jordan's population, so any situation involving possible discontent or unrest among Palestinians has the potential to affect Jordan directly. In a December 13 speech before the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in Istanbul, Turkey, King Abdullah characterized President Trump's December decision on Jerusalem as "dangerous" and as having undermined efforts to resume the peace process. The king focused particular criticism on the unilateral nature of the decision "outside the framework of a comprehensive solution that fulfils all the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people to liberty and an independent state, with East Jerusalem as its capital."22 After a December 19 meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron, King Abdullah said—in reference to a possible U.S. plan for a Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative—"We will have to hope and pray that, actually, over the next two months, our American colleagues will articulate the next phase of this challenge, and, hopefully, to be able to build on that."23 |

Israeli officials welcomed the President's decision. Reactions from other international actors—including key Arab and European countries—were mostly negative. Several governments warned that recognizing Jerusalem as Israel's capital and preparing for an embassy move could lead to the collapse of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and to violence, and some.40 Some asserted that the decision was "not in line" with U.N. Security Council resolutions.2441 On December 18, 2017, the United States vetoed a draft Security Council resolution (that was backed by all other 14 members of the Council) that. The resolution would have reaffirmed past Security Council resolutions on Jerusalem, nullified actions purporting to alter "the character, status or demographic composition of the Holy City of Jerusalem," and called upon all states to refrain from establishing diplomatic missions in Jerusalem.2542 On December 21, the U.N. General Assembly adopted a nonbinding resolution (by a vote of 128 for, nine9 against, and 35 abstaining) that contained language similar to the draft Security Council resolution.26

Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas characterized the President's decision as a U.S. withdrawal "from undertaking the role it has played over the past decades in sponsoring the peace process."27 Other Palestinian leaders also denounced the decision. In the immediate aftermath, Palestinian demonstrators clashed with Israeli authorities in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Protests also took place in other Muslim-majority countries. These demonstrations then abated.

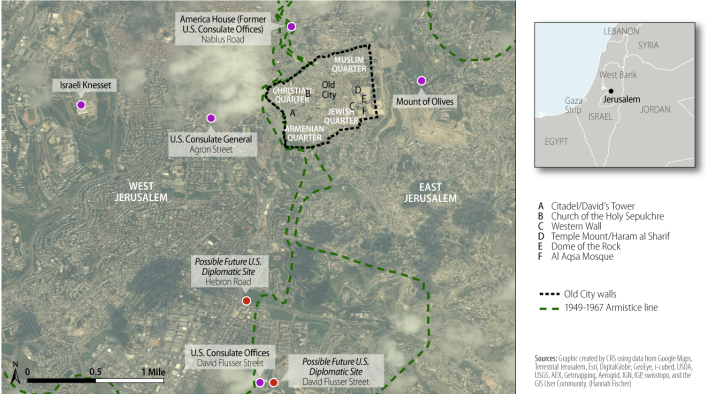

Many Members of Congress have expressed support for President Trump's decision,28 while others have voiced opposition29 or warned about possible negative consequences.30 Congress could consider a number of legislative and oversight options. With regard to the planned embassy move, these could focus on funding, timeframe and logistics, progress reports, and security for embassy facilities and staff. Past media reports have identified a number of sites owned or leased by the U.S. government in Jerusalem—including the existing Consulate General that deals with the Palestinians—as possible venues for an embassy (see Figure 2).31 Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said on December 12 that "nothing [is] going to happen in the next couple of years because it'll take us that time to get to a stage that we can begin to actually implement the building itself. So it's probably no earlier than three years out.... And we do expect that authorizers will support the move."32

Note: All locations and lines are approximate. Israel relies on the following strengths to manage potential threats to its security and existence: Another Israeli strength is the support it receives from the United States. Israeli officials closely consult with U.S. counterparts in an effort to influence U.S. decision-making on key regional issues. Israel's leaders and supporters routinely make the case to U.S. officials that Israel's security and the broader stability of the region remain critically important for U.S. interests. They also argue that Israel has multifaceted worth as a U.S. ally and that the Israeli and American peoples share core values.49 U.S. decision-makers' views could influence the type and level of support that the United States might provide to address threats Israel perceives. These views could also influence how Israel might continue its stated policy of "defending itself, by itself" while also receiving external assistance. They also could influence the extent to which the United States places conditions on the support it provides to Israel. Iran remains of primary concern to Israeli officials largely because of (1) Iran's antipathy toward Israel, (2) Iran's broad regional influence, and (3) the possibility that Iran will not face nuclear program constraints in the future. As mentioned above, in recent years Israel and Arab Gulf states have discreetly cultivated closer relations with one another in efforts to counter Iran.50 Prime Minister Netanyahu remains publicly skeptical of the 2015 international agreement on Iran's nuclear program, calling in a September 2017 speech before the U.N. General Assembly for the agreement's signatories to "fix it or nix it."51 Many other Israeli officials have accepted the nuclear agreement, and some have characterized it in positive terms. Netanyahu welcomed President Trump's decision in October 2017 to refrain from certifying Iran's compliance with the nuclear accord (under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, P.L. 114-17). The President asserted that he could not certify that the suspension of sanctions on Iran in relation to the 2015 agreement was "appropriate and proportionate" to the measures taken by Iran to terminate its illicit nuclear program.52 Israeli officials are closely following U.S. deliberations with European countries in response to the President's January statement that if these countries cannot agree to "fix flaws" in the deal, "the United States will not again waive sanctions."53 Netanyahu and his supporters in government reportedly favor the prospect of a toughened U.S. and international sanctions regime on matters not directly connected to Iran's nuclear program, such as Iran's development of ballistic missiles and its sponsorship of terrorist groups.54 Media reports indicate that many current and former officials from Israel's military and security establishment may favor the preservation of the nuclear deal because of doubts about achieving international consensus regarding stricter limits on Iran's conduct.55 | |

| |

|

Note: All locations and lines are approximate. |

Settlements

Various U.S. actions and statements feed into the overall conversation within Israel about settlement activity. According to one media source from late 2017, as Netanyahu tries to "balance the demands of his pro-settlement coalition partners with the opposition from the international community," settlement opponents' concerns focus on activity in remote areas of the West Bank as well as possible preparatory moves to develop geographically sensitive areas of Jerusalem.33

To date, the Trump Administration has been less publicly critical than the Obama Administration of Israeli settlement-related announcements and construction activity.34 However, in February 2017, the White House press secretary released a statement with the following passage:

While we don't believe the existence of settlements is an impediment to peace, the construction of new settlements or the expansion of existing settlements beyond their current borders may not be helpful in achieving that goal. As the President has expressed many times, he hopes to achieve peace throughout the Middle East region.35

In September 2017, Netanyahu told settler leaders that U.S. officials had told him privately that the Administration was prepared to tolerate limited settlement building and would not distinguish between settlement "blocs" (generally closer to Israel proper) and so-called isolated settlements.36 According to Nickolay Mladenov, the U.N. Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, about 80% of settlement moves in 2017 were in and around major Israel population centers, with 20% in more remote areas of the West Bank.37 One former U.S. official has written, "About 90,000 [settlers] live deep in the West Bank on the Palestinian side of the Security Barrier.... As time passes, the situation becomes ever more complicated."38

By late 2017, Administration responses to Israeli settlement-related announcements mostly took the form of general statements of policy rather than reactions to the particulars—arguably contributing to some uncertainty about U.S. views and intentions vis-à-vis settlements. One media report in October suggested that Israel was coordinating settlement plans to some extent with U.S. officials.39 However, in late October, the Israeli Knesset (parliament) delayed action on a proposed bill aimed at expanding Jerusalem's municipal boundaries to include various West Bank settlements, following apparent intervention by the Administration. An unnamed senior U.S. official reportedly said that "the U.S. is discouraging actions that it believes will unduly distract the principals from focusing on the advancement of peace negotiations. The Jerusalem expansion bill was considered by the administration to be one of those actions."40

Regional Security Issues

For decades, Israel has relied on the following perceived advantages to manage potential threats to its security and existence:

- overwhelming regional conventional military superiority;

undeclared but universally presumed nuclear weapons capability;41 and- de jure or de facto arrangements with the authoritarian leaders of its Arab state neighbors aimed at preventing regional conflict.

Israeli officials closely consult with U.S. counterparts in an effort to influence U.S. decisionmaking on key regional issues. Reflecting Israeli concerns about these issues and about potential changes in levels of U.S. interest and influence in the region, some of Israel's leaders and supporters make the case to U.S. officials and lawmakers that Israel's security and the broader stability of the region continue to be critically important for U.S. interests. They also argue that Israel has substantial and multifaceted worth as a U.S. ally beyond temporary geopolitical considerations and shared ideals and values.42

U.S. decisionmakers' views on these points could influence the type and level of support that the United States might provide to address threats Israel perceives, or how Israel might continue its traditional prerogative of "defending itself, by itself" while also receiving external assistance. They also could influence the extent to which the United States places conditions on the support it provides to Israel.

Since late 2010, a number of countries in the region have experienced significant turmoil, leading to heightened uncertainty with regard to situations on or near Israel's borders. These situations involve governments and nonstate groups, along with flows of people, goods, and weapons. To some extent, these developments may have reduced the conventional military threats facing Israel.

The following are significant (and sometimes overlapping) threats facing Israel.

Iran and Its Allies

Although many Israeli officials have accepted the 2015 international agreement on Iran's nuclear program, and some even have characterized it in positive terms, Iran remains of primary concern to Israel largely because of (1) Iran's antipathy toward it, (2) Iran's broad regional influence, and (3) the possibility that Iran will not face nuclear program constraints in the future. Netanyahu remains publicly skeptical of the Iranian nuclear agreement, calling in a September 2017 speech before the U.N. General Assembly for the agreement's signatories to "fix it or nix it."43

Netanyahu welcomed President Trump's decision in October 2017 to refrain from certifying Iran's compliance with the nuclear accord (under the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, P.L. 114-17). The President asserted that he could not certify that suspension of sanctions on Iran in relation to the 2015 agreement was "appropriate and proportionate" to the measures taken by Iran to terminate its illicit nuclear program.44 Netanyahu and his supporters in government reportedly favor the prospect of a toughened U.S. and international sanctions regime on matters not directly connected to Iran's nuclear program, such as Iran's development of ballistic missiles and its sponsorship of terrorist groups.45 Media reports indicate that many current and former officials from Israel's military and security establishment may favor the preservation of the nuclear deal because of doubts about achieving international consensus regarding stricter limits on Iran's conduct.46

Lebanese Hezbollah is one major Iranian ally with the ability to threaten Israel. Hamas (with its main base of operations in the Gaza Strip) is also largely aligned with Iran, but somewhat less so than Hezbollah, perhaps because of Hamas's Sunni Islamist and Palestinian nationalist characteristics. In recent years, Israel and Arab Gulf states have discreetly cultivated closer relations with one another in efforts to counter Iran.47

Lebanon-Syria Border Area and Hezbollah

During 2017, Israeli officials have increasingly focused on concerns about Iranian influence near Israel's northern borders with Lebanon and Syria. The government of Bashar al Asad has regained control of much of Syria's territory, with assistance from Iran, various Iran-backed militias, and Russia.48 Israel has alleged that Iran aspires to establish territorial corridors to the Mediterranean coast, and to have some kind of military presence along those corridors.49 In his September address before the U.N. General Assembly, Prime Minister Netanyahu said

We will act to prevent Iran from establishing permanent military bases in Syria for its air, sea and ground forces. We will act to prevent Iran from producing deadly weapons in Syria or in Lebanon for use against us. And we will act to prevent Iran from opening new terror fronts against Israel along our northern border.50

In this context, U.S. National Security Advisor Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster publicly warned in December of the prospect forof Iran to havehaving a "proxy army on the borders of Israel."51

Accordingly, Israel reportedly has

- continued airstrikes on targets inside Syria to prevent weapons transfers to Hezbollah in Lebanon, and increased warnings about threats from Hezbollah;

5260

reportedlycarried out airstrikes aimed at discouraging Iran from constructing and operating bases or advanced weapons manufacturing facilities in Syria;5361 and- sought to influence agreements

betweenamong Russia, the United States, and Jordan on de-escalation zones in southern Syria, especially by seeking Russian help in keeping Hezbollah and other Iranian allies as far as possible from the Israeli border.54

In December, after an alleged Israeli strike on a base in Syria that was supposedly controlled by Iran, a report surfaced about Prime Minister Netanyahu previously communicating to Syrian President Asad Israel's readiness to act against Iranian bases.55 62 To date, Russia has apparently tolerated some Israeli military operations in or near Syrian airspace. ItsRussia's maintenance of advanced air defense systems and its other interests in Syria could affect future Israeli operations.

Hezbollah has challenged Israel's security near the Lebanese border for decades.56 In recent years, Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's weapons buildup—including reported upgrades to the range and precision of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.57 During Syria's civil war, Israel has reportedly provided various means of support to rebel groups in the vicinity of the Syria-Israel border in order to prevent Hezbollah or other Iran-linked groups from controlling the area.58

Various incidents in 2017 have increased speculation about future conflict between Israel and Hezbollah and potential consequences for Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and others.59 In November, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced his resignation (which he withdrew a month later), citing "unacceptable" Iranian influence over Lebanese politics. In response, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah accused Saudi Arabia (the country where Hariri announced the resignation) of inciting Israel to attack Lebanon.60 Nasrallah also said that a new Israel-Hezbollah clash was possible but unlikely, and this assertion appears to track with the tone of Israeli political discourse and the near-term views of many Israeli experts.61

Palestinians

The threat to Israel from the unresolved conflict with the Palestinians may have less destructive potential in immediate military terms than threats from Iran's and Hezbollah's missiles and other capabilities. However, if the conflict remains unresolved, it could have long-term political implications that fuel wider regional or global problems for Israel. Three major conflicts between Israel and Palestinian militant groups in the Gaza Strip (most prominently, Hamas) have taken place in 2008-2009, 2012, and 2014. Some analysts have speculated about the possibility that conflict could resume,62 but as of December 2017, Hamas appears to be acting against Salafist militants in Gaza whose rocket launches into Israel may represent an effort to trigger a new round of Israel-Hamas hostilities.63 Israel appears to have increased its capacity to detect and destroy tunnels that gave Hamas some advantages in previous conflict situations.64

Domestic Israeli Developments

February 2018 Cross-Border Incident Raises Tensions On February 10, 2018, a cross-border incident involving Israeli, Iranian, and Syrian forces raised regional tensions. After an Israeli helicopter reportedly downed an Iranian drone that was allegedly in Israeli airspace, Israeli forces launched a reprisal attack against targets in Syria. Under fire from Russian-origin Syrian air defense systems, an Israeli F-16 was reportedly hit. It crashed in Israeli territory, with the two occupants ejecting (one was hospitalized). Israel then launched another attack against what Israeli officials described as multiple Syrian air defense positions and Iranian military sites inside Syria.63 The Israel Air Force called it "the biggest and most significant attack" it has conducted against Syrian air defenses since the 1982 Lebanon war.64 Although the incident's implications are unclear, a number of key actors have made statements in the aftermath. Israeli officials warned Iran that it would not tolerate an Iranian military foothold at its doorstep, while also stating that Israel does not seek to escalate conflict.65 Secretary of Defense James Mattis characterized Israel's actions as self-defense and expressed full U.S. support for them.66 Fueling speculation that the Israeli attacks may have come close to areas where Russian personnel are stationed, Russia's foreign ministry called for restraint and said that it is "absolutely unacceptable to create threats to the lives and security of Russian soldiers."67 Observers speculate about how the incident will affect these actors' calculations going forward.68 Hezbollah has challenged Israel's security near the Lebanese border for decades.69 In recent years, Israeli officials have sought to draw attention to Hezbollah's weapons buildup—including reported upgrades to the range and precision of its projectiles—and its alleged use of Lebanese civilian areas as strongholds.70 During Syria's civil war, Israel reportedly has provided various means of support to rebel groups in the vicinity of the Syria-Israel border in order to prevent Hezbollah or other Iran-linked groups from controlling the area.71 Speculation persists about future conflict between Israel and Hezbollah and potential consequences for Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and others.72 One January 2018 analysis stated that the "balance of deterrence" between Israel and Hezbollah remains strong and "weighs against either side deliberately launching a war," while the "risk of miscalculation" has grown "as various actors in Syria seek to consolidate influence."73A number of controversial

domestic developments are taking place in Israel.65 Several of the government's opponents and critics have voiced warnings about government initiatives depicted as targeting dissent or undermining the independence of key Israeli institutions such as the media, the judiciary, and the military. Controversial Knesset legislation may be forthcoming to define Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people in a basic law,6674 and limit the Supreme Court's power of judicial review over legislation.67

Some on the right side of the political spectrum have joined the criticism, expressing concerns about the future of democracy in Israel. OneA November 2017 media article characterized the split on the Israeli right as being between a past generation (including Israeli President Reuven Rivlin) that "were sticklers for defending minority rights and the rule of law" and "a newer, more populist and partisan politics epitomized by Mr. Netanyahu's government."68 Contention surrounding these issues may be heightened by the possibility of early77 Early elections (legally, elections are required by 2019) may heighten contention surrounding these issues if the governing coalition splits over Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, thean ongoing criminal investigation into Prime Minister Netanyahu's conduct, or some other issue.

As 2017 progressed, a legal probe of Prime Minister Netanyahu turned into a criminal investigation—in connection with allegations of various types of corruption—that some observers speculate or some other issue.

Police are investigating Netanyahu for alleged corruption. Some observers speculate that the investigation could threaten his term of office or lead to early elections.69.78 Netanyahu has dismissed the allegations.

One media account summarizes the two specific investigations in which Netanyahu is a suspect as followsThere are two specific investigations:

Case 1000 revolves around gifts he[Netanyahu] received from businessmen, including cigars and champagne. Netanyahu's lawyers say they were simply presents from long-time friends, with no quid pro quo.

Case 2000 focuses on suspicions Netanyahu negotiated with the publisher of Israel's best-selling newspaper for better coverage in return for curbs on the competition. The prime minister's lawyers say Netanyahu never seriously considered any such deal.70

Two of Netanyahu's closest associates and attorneys were arrested in early November, bolstering speculation that charges—if Israel's attorney general introduces them—could come sometime in 2018.71 The Knesset is considering legislation that would prohibit police from publicizing investigative findings against government officials before an attorney general's decision to prosecute. However, after facing criticism that such a bill would be self-serving, Netanyahu has said that the legislation would not apply to his case.72

If elections take place in the near future, Netanyahu (if he runs) could face challenges from figures on the right of the political spectrum (including Education Minister Naftali Bennett, Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman, former minister Gideon Saar, and the previous defense minister Moshe Ya'alon), or nearer the center or left (former finance minister Yair Lapid, current finance minister Moshe Kahlon, and new Labor Party leader Avi Gabbay).84

Author Contact Information Before the Jerusalem announcement, some developments raised questions about the viability of a U.S.-brokered peace process. For example, statements by President Trump fueled public speculation about the level of his commitment to a negotiated "two-state solution," a conflict-ending outcome that U.S. policy has largely advocated since the Israeli-Palestinian peace process began in the 1990s. Additionally, some media reports suggested that Israel was coordinating its West Bank settlement construction plans with U.S. officials. Danny Zaken, "Israel, US coordinated on settlement construction," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, October 23, 2017. Adam Rasgon, "Abbas Slams Trump Jerusalem Move as 'Condemned, Unacceptable,'" jpost.com, December 6, 2017. Loveday Morris and Ruth Eglash, "With Trump in Power, Emboldened Israelis Try Redrawing Jerusalem's Boundaries," Washington Post, January 12, 2018. Derek Stoffel, "Trump's Jerusalem declaration: a gift to Israel, but price tag may be high," CBC News, December 12, 2017. Full text: Trump and Netanyahu remarks in Davos, Times of Israel, January 25, 2018. Isabel Kershner, "Trump's Threat to Cut Palestinian Aid Worries Israelis," New York Times, January 4, 2018. "IDF chief said to warn Gaza war likely if humanitarian crisis persists," Times of Israel, February 4, 2018. "PA 'Maintains' Communications with US, Consul 'Invited' to PLO Central Council Session," Al-Hayah Online (translated from Arabic), January 13, 2018, Open Source Enterprise LIW2018011368005965. The President's advisors on Israeli-Palestinian issues include his senior advisor Jared Kushner (who is also his son-in-law), special envoy Jason Greenblatt, and U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman. Ahmad Melham, "Abbas reaches out to Europeans to help rebuild negotiations framework," Al-Monitor Palestine Pulse, January 31, 2018; Khaled Abu Toameh and Stuart Winer, "Palestinians court Russia as new broker in peace process," Times of Israel, February 2, 2018. "PA's Abbas Says Palestinians Want Peace, Reject US Sponsorship of Peace Process," Palestine Satellite Channel Television (translated from Arabic), January 14, 2018, Open Source Enterprise LIW2018011470870087. For information on an ongoing Fatah-Hamas negotiating process mediated by Egypt, see "Palestinian reconciliation deal dying slow death," Times of Israel, February 2, 2018. "Palestinian Central Council calls for struggle against Israel 'in all forms,'" Al Arabiya English, January 16, 2018. See, e.g., "Arabs to seek world recognition of East Jerusalem as Palestinian capital," Times of Israel, January 6, 2018; "Palestinians seek to join UN as full member – report," Times of Israel, January 7, 2018. Pew Research Center, "Republicans and Democrats Grow Even Further Apart in Views of Israel, Palestinians," January 23, 2018. Bryant Harris, "Trump moves exacerbate growing US partisan divide over Israel," Al-Monitor Congress Pulse, January 23, 2018; Ron Kampeas, "Why Democrats sat on their hands when Donald Trump celebrated recognizing Jerusalem as the capital of Israel," Jewish Telegraphic Agency, February 1, 2018. Amir Tibon, "Trump 'Firmly Committed' to Restarting Peace Process, Pence Says in Egypt Ahead of Israel Visit," Ha'aretz, January 20, 2018. Saudi Press Agency, "Basis for Resolving Palestinian-Israeli Conflict Depends on International References, Arab Peace Initiative" January 6, 2018. See, e.g., David Kirkpatrick, "Tapes Reveal Tacit Acceptance by Arabs of Jerusalem Decision," New York Times, January 7, 2018. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. See, e.g., Yaroslav Trofimov, "Middle East Crossroads: Israel, Saudi Arabia Can't Manage Closer Ties," Wall Street Journal, February 2, 2018. See CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. "Palestinians condemn Israeli plans to annex West Bank," Al Jazeera, January 1, 2018. David M. Halbfinger, "As a 2-State Solution Loses Steam, a 1-State Plan Gains Traction," New York Times, January 6, 2018. See, e.g., "PA's Abbas Says Palestinians Want Peace, Reject US Sponsorship of Peace Process," Palestine Satellite Channel Television (translated from Arabic), January 14, 2018, Open Source Enterprise LIW2018011470870087. For another observer's view, see Lara Friedman, "Taking Issues 'Off the Table' - First Jerusalem, Now Refugees," Huffington Post, January 5, 2018. "Jerusalem embassy: Abbas says Trump plan 'slap of the century,'" BBC News, January 14, 2018. For more speculation about possible Administration ideas, see Uri Savir, "Trump radicalizes US Mideast policies," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, February 4, 2018. White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Presidential Proclamation Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem, December 6, 2017. Under P.L. 104-45, if a U.S. embassy has not officially opened in Jerusalem by the deadline, a 50% limitation on spending from the general "Acquisition and Maintenance of Buildings Abroad" budget would apply in the following fiscal year unless the President signs a waiver asserting a national security interest in preventing the spending limitation. Despite his proclamation on the planned embassy relocation, the President ultimately did sign a waiver in response to the December deadline. Presidential Determination No. 2018-02, December 6, 2017. So long as the embassy has not officially opened in Jerusalem, the waiver is required every six months under P.L. 104-45 to keep the spending limitation from taking effect. See, e.g., Scott R. Anderson and Yishai Schwartz, "How to Move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem," November 30, 2017. U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem, Transcription for Telephonic Press Briefing with Acting Assistant Secretary David Satterfield, December 10, 2017. White House, Office of the Press Secretary, WTAS: Support For President Trump's Decision To Recognize Jerusalem As Israel's Capital, December 7, 2017. See, e.g., Letter from Senator Dianne Feinstein to President Trump, dated December 1, 2017, available at https://twitter.com/SenFeinstein/status/938095387952500737/photo/1. See, e.g., Statement from Senator Tim Kaine, available at https://www.kaine.senate.gov/press-releases/kaine-statement-on-trump-announcement-on-jerusalem. White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Statement by President Trump on Jerusalem, December 6, 2017. For information on the "status quo" arrangement, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. Steve Holland, "Trump likes two-state solution, but says he will leave it up to Israelis, Palestinians," Reuters, February 23, 2017. Eric Cortellessa, "White House 'cannot envision situation' where Western Wall is not part of Israel," Times of Israel, December 15, 2017. Full text: Trump and Netanyahu remarks in Davos, Times of Israel, January 25, 2018. "Trump said to mull unveiling peace plan even if Abbas maintains boycott," Times of Israel, February 2, 2018. Ruth Levush, "Israel: Restrictions on Ceding Areas in Jerusalem Municipality to Foreign Entities," Global Legal Monitor, Law Library of Congress, January 5, 2018. In the initial aftermath, protests occurred in the West Bank and Gaza and other Muslim-majority countries, but did not significantly escalate. Permanent Representatives of Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, and United Kingdom, Joint Declaration following Security Council meeting on Jerusalem (PRs from France, Italy, Germany, Sweden and UK), December 8, 2017. See footnote 42 for information on some past U.N. Security Council resolutions (UNSCRs) pertaining to Jerusalem. U.N. document S/2017/1060, "Egypt: Draft Resolution." Relevant UNSCRs pertaining to Jerusalem include 242 (1967), 252 (1968), 267 (1969), 298 (1971), 338 (1973), 446 (1979), 465 (1980), 476 (1980), 478 (1980), and 2334 (2016). UNSCR 478 (1980) called upon states that had established diplomatic missions at Jerusalem to withdraw such missions. Footnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

United Nations Press Release, General Assembly Overwhelmingly Adopts Resolution Asking Nations Not to Locate Diplomatic Missions in Jerusalem and new Labor Party leader Avi Gabbay). In December, thousands of Israelis—who appear to come mostly from Israel's "anti-Netanyahu" camp—have protested Netanyahu's alleged corruption, though polls still suggest that Netanyahu may retain an advantage over those who seek to succeed him.73

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, e.g., "Israeli officials: US abstention was Obama's 'last sting,' showed his 'true face,'" Times of Israel, December 24, 2016; Jeffrey Goldberg, "The Obama Doctrine," The Atlantic, April 2016; Jason M. Breslow, "Dennis Ross: Obama, Netanyahu Have a 'Backdrop of Distrust,'" PBS Frontline, January 6, 2016; Sarah Moughty, "Michael Oren: Inside Obama-Netanyahu's Relationship," PBS Frontline, January 6, 2016. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, "Readout of the President's Call with Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel," January 22, 2017. See also Aron Heller, "After Obama, Israel's Netanyahu relishing in Trump love fest," Associated Press, October 19, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

Friedman's nomination and Senate confirmation (which took place via a 52-46 vote) attracted attention because of his past statements and financial efforts in support of controversial Israeli settlements in the West Bank, and his sharp criticism of the Obama Administration, some Members of Congress, and some American Jews. At Friedman's February 16, 2017, nomination hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he apologized for and expressed regret regarding many of the critiques he previously directed at specific people. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

See CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. |

CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. |

Grant Rumley and Neri Zilber, "Can Anyone End the Palestinian Civil War?" foreignpolicy.com, October 16, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. |

Ibid.; Saud Abu Ramadan et al., "Hamas Deal to Cede Gaza Control Sets Up Showdown Over Guns," Bloomberg, October 2, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. |

Matthew Levitt and Aviva Weinstein, "How Hamas' Military Wing Threatens Reconciliation With Fatah," foreignaffairs.com, November 29, 2017. For additional background, see Avi Issacharoff, "Sick of running Gaza, Hamas may be aiming to switch to a Hezbollah-style role," Times of Israel, October 1, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. |

Margaret Talev and Jennifer Jacobs, "Jerusalem Divides Trump's Team and Complicates Kushner's Peace Plan," Bloomberg, December 6, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. |

See, e.g., Olivier Knox, "Five things to watch in Trump's Jerusalem speech," Yahoo News, December 5, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. |

CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. |

David M. Halbfinger et al., "President Calls Jerusalem Shift 'The Right Thing,'" New York Times, December 7, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. |

The United States withdrew from the U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization in October 2017, largely owing to its actions in the Israeli-Palestinian sphere. CRS Insight IN10802, U.S. Withdrawal from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), by [author name scrubbed]. Israel subsequently withdrew from UNESCO. Additionally, Section 7048(c) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), prohibits funding in support of the U.N. Human Rights Council unless the Secretary of State determines "that participation in the Council is important to the national interest of the United States and that the Council is taking significant steps to remove Israel as a permanent agenda item." |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. |

White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Presidential Proclamation Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem, December 6, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

Presidential Determination No. 2018-02, December 6, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. |

See, e.g., Scott R. Anderson and Yishai Schwartz, "How to Move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem," November 30, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. |

U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem, Transcription for Telephonic Press Briefing with Acting Assistant Secretary David Satterfield, December 10, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. |

White House, Office of the Press Secretary, Statement by President Trump on Jerusalem, December 6, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20. |

For information on the "status quo" arrangement, see CRS Report RL33476, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. |

Steve Holland, "Trump likes two-state solution, but says he will leave it up to Israelis, Palestinians," Reuters, February 23, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. |

King Abdullah II website, Remarks by His Majesty King Abdullah II at the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation Summit, Istanbul, Turkey, December 13, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. |

King Abdullah II website, King holds talks with President Macron in Paris, December 19, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24. |

Permanent Representatives of Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, and United Kingdom, Joint Declaration following Security Council meeting on Jerusalem (PRs from France, Italy, Germany, Sweden and UK), December 8, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

U.N. document S/2017/1060, "Egypt: Draft Resolution." Relevant U.N. Security Council resolutions (UNSCRs) pertaining to Jerusalem include 242 (1967), 252 (1968), 267 (1969), 298 (1971), 338 (1973), 446 (1979), 465 (1980), 476 (1980), 478 (1980), and 2334 (2016). UNSCR 478 (1980) called upon states that had established diplomatic missions at Jerusalem to withdraw such missions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. |

Adam Rasgon, "Abbas Slams Trump Jerusalem Move as 'Condemned, Unacceptable,'" jpost.com, December 6, 2017. Vice President Pence postponed a December trip to the region, citing domestic political demands. Before the postponement, some Christian leaders in the region had refused to meet with him. Michael Jansen, "Christian and Muslim leaders boycott Mike Pence's Holy Land visit," Irish Times, December 15, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

White House, Office of the Press Secretary, WTAS: Support For President Trump's Decision To Recognize Jerusalem As Israel's Capital, December 7, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. |

See, e.g., Letter from Senator Dianne Feinstein to President Trump, dated December 1, 2017, available at https://twitter.com/SenFeinstein/status/938095387952500737/photo/1. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. |

See, e.g., Statement from Senator Tim Kaine, available at https://www.kaine.senate.gov/press-releases/kaine-statement-on-trump-announcement-on-jerusalem. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Raphael Ahren, "Jerusalem of Trump: Where the president-elect might put the US embassy," December 13, 2016; Efraim Cohen, "How Trump Could Make Quick Move to Jerusalem For U.S. Israel Embassy," New York Sun, December 13, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Felicia Schwartz and Jess Bravin, "U.S. Plans Jerusalem Embassy in 2019," Wall Street Journal, January 19, 2018. 46.

|

|

Full text: Trump and Netanyahu remarks in Davos, Times of Israel, January 25, 2018. 47.

|

|

Mark Landler, "Trump Administration Presses to Relocate Embassy to Jerusalem by 2019," New York Times, January 19, 2018: "Scouting a site, commissioning a design and building the embassy compound could take up to six years, according to State Department officials, and cost $600 million to $1 billion." |

Secretary Tillerson, Remarks at Town Hall, Washington, DC, December 12, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||

| 33. |

David M. Halbfinger and Isabel Kershner, "Israel Presses Forward on West Bank Settlement Plans, but Guardedly," New York Times, October 17, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34. |

Nathan Guttman, "Bibi Tells Settlers: 'Don't Be Piggy,'" Jewish Daily Forward, September 27, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35. |

White House Office of the Press Secretary, Statement by the Press Secretary, February 2, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36. |

Jacob Magid and Alexander Fulbright, "PM to settler leaders: US told Israel not to be a pig on settlement building," Times of Israel, September 27, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37. |

United Nations Secretary-General, Note to Correspondents: Nickolay Mladenov - Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace process - Briefing to the Security Council on the Situation in the Middle East - Report on UNSCR 2334 (2016), December 18, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38. |

Hady Amr, "Jerusalem: After 30 Years of Hope and Failure, What's Next for Israel/Palestine?" foreignpolicy.com, December 11, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39. |

Danny Zaken, "Israel, US coordinated on settlement construction," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, October 23, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40. |

"Trump administration concerned about bill that would add West Bank settlements to Jerusalem," Jewish Telegraphic Agency, October 29, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Israel is not a party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and maintains a policy of "nuclear opacity" or amimut. A 2014 report examining data from a number of sources through the years estimated that Israel possesses an arsenal of around 80 nuclear weapons. Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, "Israeli nuclear weapons, 2014," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 70(6), 2014, pp. 97-115. The United States has countenanced Israel's nuclear ambiguity since 1969, when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and U.S. President Richard Nixon reportedly reached an accord whereby both sides agreed never to acknowledge Israel's nuclear arsenal in public. Eli Lake, "Secret U.S.-Israel Nuclear Accord in Jeopardy," Washington Times, May 6, 2009. No other Middle Eastern country is generally thought to possess nuclear weapons. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marty Oliner, "US-Israel relationship: More critical than ever," The Hill, May 3, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

51.

Neri Zilber, "Israel's secret Arab allies," New York Times, July 15, 2017. |

Israel Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu's Speech at the United Nations General Assembly, September 19, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

For information on President Trump's decision, see CRS Report R44942, Options to Cease Implementing the Iran Nuclear Agreement, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

54.

Jeremy Diamond, "Trump issues warning, but continues to honor Iran deal," CNN, January 12, 2018. |

See, e.g., Jonathan Ferziger and Udi Segal, "Netanyahu's Challenge: Help Trump Fix or Scrap the Iran Deal," Bloomberg, October 18, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Barak Ravid, et al., "Netanyahu at Odds With Israeli Military and Intelligence Brass Over Whether to Push Trump to Scrap Iran Nuclear Deal," Ha'aretz, September 16, 2017; Laura Rozen, "Ex-Netanyahu national security adviser urges US to keep Iran deal," Al-Monitor, October 2, 2017; Mark Landler, "Ehud Barak, Israeli Hawk and No Friend of Iran, Urges Trump to Keep Nuclear Deal," New York Times, October 11, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47. |

See, e.g., December 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy, op. cit.; Neri Zilber, "Israel's secret Arab allies," New York Times, July 15, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dion Nissenbaum, "As ISIS Fades, a New Focus on Iran—White House retools Mideast strategy, sees Iranian military as next challenge," Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See, e.g., Yossi Melman, "The Middle East quagmire," Jerusalem Report, October 16, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Israel Prime Minister's Office, PM Netanyahu's Speech at the United Nations General Assembly, September 19, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dion Nissenbaum, "Pentagon Sees a Threat to Israel," Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Israel said to have hit Hezbollah convoys dozens of times," Times of Israel, August 17, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rory Jones, "Israel Warned Syria About Iranian Military Presence," Wall Street Journal, December 5, 2017; "Israel airstrike hits suspected Syrian chemical weapons plant," Deutsche Welle, September 7, 2017 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55. |

Rory Jones, "Israel Warned Syria About Iranian Military Presence," Wall Street Journal, December 5, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56. |

CRS Report R44759, Lebanon, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 57. |

See, e.g., Andrew Exum, "The Hubris of Hezbollah," The Atlantic, September 18, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58. |

Rory Jones, et al., "Israel Gives Cash, Aid to Rebels in Syria," Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59. |

For possible conflict scenarios, see Exum, op. cit.; and Michael Eisenstadt and Jeffrey White, "A War Without Precedent: The Next Hizballah-Israel Conflict," American Interest, September 19, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60. |

"Lebanon army chief warns of Israel threat amid political crisis," Reuters, November 21, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 61. |

Ibid.; Melman, "The Israel-Sunni Alliance," op. cit. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62. |

See, e.g., Nathan Thrall and Robert Blecher, "Stopping the next Gaza war," New York Times, July 31, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63. |

Jack Moore, "Hamas Is Arresting and Torturing Jihadis to Prevent War with Israel," newsweek.com, December 19, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 64. |

Ben Caspit, "How Israel is bringing an end to Hamas' tunnels," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, December 11, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65. |

See, e.g., Mazal Mualem, "Knife fight at the Knesset," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, October 24, 2017. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63.

|

|

Judah Ari Gross, "IDF, Syrian rebels identify regime targets hit in reprisal strikes," Times of Israel, February 11, 2018; Aron Heller and Sarah el Deeb, "Israel Says it Has Carried Out a 'Large Scale Attack' Against Iranian Targets in Syria," Associated Press, February 10, 2018. 64.

|

|

Gross, op. cit. 65.

|

|

See, e.g., "Minister: Iran will need 'time to digest' how Israel hit covert military sites," Times of Israel, February 11, 2018. 66.

|

|

"US defense secretary: Israel has 'absolute right to defend itself' against Iran," Times of Israel, February 12, 2018. 67.

|

|

Isabel Kershner, et al., "Israel Loses Jet and Then Hits at Iran in Syria," New York Times, February 11, 2018. 68.

|

|

See, e.g., Ibid.; Rory Jones, "Iran Looms over Israel-Syria Clash," Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2018. 69.

|

|

CRS Report R44759, Lebanon, by [author name scrubbed]. 70.

|

|

See, e.g., Spyer and Blanford, op. cit.; Andrew Exum, "The Hubris of Hezbollah," The Atlantic, September 18, 2017. 71.

|

|

Rory Jones, et al., "Israel Gives Cash, Aid to Rebels in Syria," Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2017. 72.

|

|

For possible conflict scenarios, see Exum, op. cit.; and Michael Eisenstadt and Jeffrey White, "A War Without Precedent: The Next Hizballah-Israel Conflict," American Interest, September 19, 2017. 73.

|

|

Spyer and Blanford, op. cit. |

See, e.g., Lahav Harkov, "Government says it will push Jewish nation-state bill for first vote soon," jpost.com, December 18, 2017. Although the basic law's direct effect would be largely symbolic, some observers are concerned that the bill might further undermine the place of Arabs in Israeli society . |

|

See, e.g., "Jewish Home unveils draft of bill to weaken High Court," Times of Israel, December 19, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

77.

Lahav Harkov, "Netanyahu: I've Been Talking to Americans About Annexing Settlements," jpost.com, February 12, 2018. |

Isabel Kershner, "Israel's Right Also Sees A Threat to Democracy," New York Times, November 1, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ben Caspit, "Netanyahu versus Israel," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, September 20, 2017; Ronen Bergman and Holger Stark, "Submarine affair's secrets are coming to the surface," Ynetnews, October 17, 2017. Separate investigations or reports implicate other figures from Netanyahu's Likud party or the government coalition, including |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Maayan Lubell, "Israel pushes on with law seen protecting PM under criminal probe," Reuters, November 27, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ben Caspit, "Israeli police turn up heat on Netanyahu," Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, November 7, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 73. | Mualem, "Israelis not ready to topple Netanyahu over corruption," op. cit. 82.

|

|

"Poll: Most Israelis want Netanyahu to resign if police recommend indictment," Times of Israel, December 24, 2017. 83.

|

|

Olmert was convicted in 2014 and served a 16-month prison sentence from 2016 to 2017. Ian Deitch, "Israel's ex-PM Ehud Olmert released from prison," Associated Press, July 2, 2017. 84.

|

See, e.g., "Poll: Lapid-Kahlon alliance would defeat Netanyahu's Likud in fresh elections," Times of Israel, January 14, 2018; Ravit Hecht, "Was Leaving Likud the Mistake of Moshe Ya'alon's Life? An Interview with Israel's Ex-defense Minister," Ha'aretz, January 25, 2018. |