Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from October 24, 2017 to June 5, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Overview

- Why Do Organizations Value Diversity?

- Diversity and Cohesion

- Diversity and Effectiveness

- Diversity Management

- Diversity and the Civil-Military Relationship

- Diversity and Social Equality

- How Does DOD Define Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity?

- Diversity and Inclusion Policy

- Military Equal Opportunity Policy

- How Does DOD Manage Diversity and Equal Opportunity?

- Office

of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity (ODMEOfor Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (ODEI) - Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute (DEOMI)

- Military Departments

- How Have the Definition and Treatment of Protected Classes Evolved in the Armed Forces?

- Racial/Ethnic Inclusion

;: Background and Force Profile - The Civil War to World War II, Racial Segregation

- Desegregation in the Truman Era

- Civil Rights Movement and Anti-Discrimination Policies

- The Vietnam War and Efforts to Improve Race Relations

- Is the Racial/Ethnic Profile of the Military Representative of the Nation?

- Inclusion of Women

,: Background and Force Profile - Women's Participation in World War I and World War II

- Post-WWII and the Women's Armed Services Integration Act

- Equal Rights Movement and an All-Volunteer Force

- The 1990s: Increasing Roles for Women

- Recent Changes to Women's Assignment Policies

- Is the Gender Mix in the Military Representative of the Nation?

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Inclusion

;: Background and Force Profile - Advocacy and DOD Policy Formation in the 1970s and 1980s

- The Evolution of Don't Ask Don't Tell

- Repeal of Don't Ask Don't Tell (DADT)

- Post-DADT Integration

- Transgender Service Policies

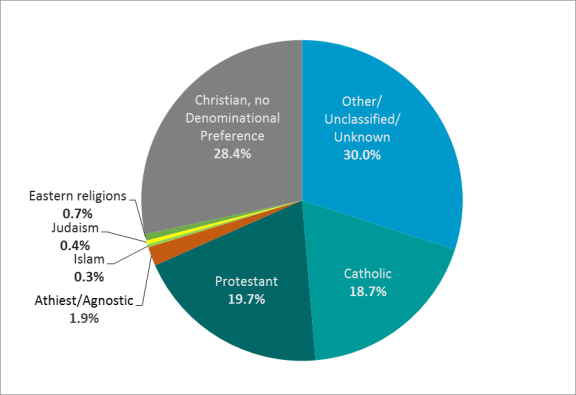

- Religious Inclusion: Background and Force Profile

- Is Religious Diversity in the Military Representative of the Nation?

- Military Diversity and Equal Opportunity Issues for Congress

- Diversity in Leadership

- Diversity and Inclusion at the Service Academies

- Management of Harassment

/and Discrimination Claims - Inclusion of Transgender Servicemembers

- Religious Discrimination and Accommodation

- Other Aspects of Diversity

- Are Diversity and Equal Opportunity Initiatives Needed in the Military?

Figures

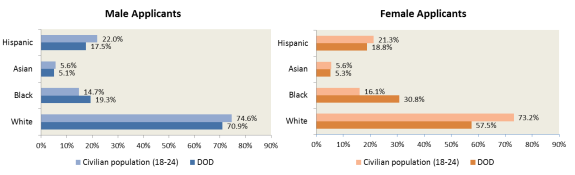

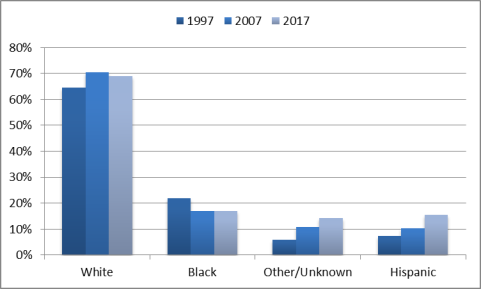

- Figure 1. DOD Active Duty Racial and Ethnic Representation

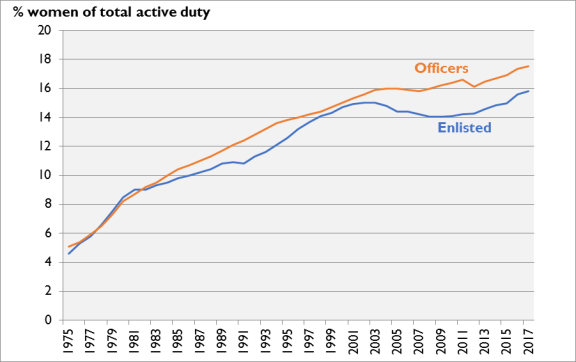

- Figure 2. Women Serving on Active Duty as a Percentage of Total Active Duty Force

- Figure 3. Female Representation in the Active Component

- Figure 4. Women in Combat Policy Changes and Female Propensity for Military Service

Figure 5. Non-prior Service Applicants for Active Component Enlistment by Gender and Race/Ethnicity - Figure

4. Religious6. Religious Diversity in the Active Duty Force - Figure

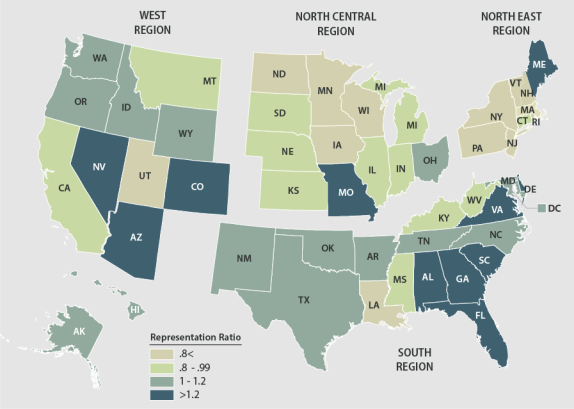

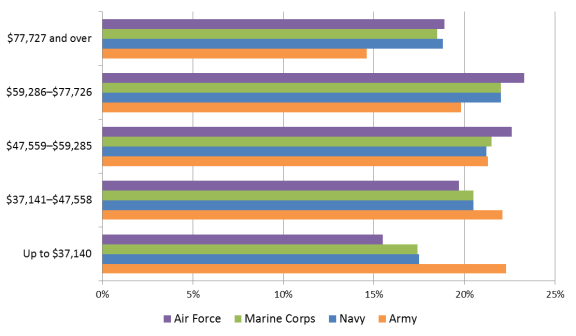

57. Representation Ratios for Non-prior Service Enlisted Accessions by State - Figure

68. Active Component Enlisted Accessions by Median Household Income

Tables

- Table 1. Diversity Goals for DOD and the Federal Workforce

- Table 2. Equal Opportunity Definitions in DOD Policy

- Table 3. Key Factors Measured in DEOCS

- Table 4. Selected Legislation for Command Climate Surveys Table 5. Military Fatal Casualties as a Result of the Vietnam War

- Table

56. Race and Ethnic Representationinin the ActiveDuty and Selected ReserveComponent and U.S. Population - Table

67. Racial/Ethnic Representation Among Post-secondary Degree Holders - Table

78. 1992 Presidential Commission on Women in Combat - Table

89. Female Representation in the Active Duty Armed Forces - Table

910. Timeline for DOD Transgender Policy Changes Table 11. Military Department Policy Regarding Religious Accommodation and Expression - Table

10. Service Academy Enrollment by Gender12. Female Enrollment at Service Academies

- Table

1113. Service Academy and U.S. Undergraduate Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity - Table

12.14. Estimated Gender Discrimination and Sexual Harassment at Service

Summary

Under Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the authority to raise and support armies; provide and maintain a navy; and provide for organizing, disciplining, and regulating them. Congress has used this authority to establish criteria and standards that must be met for individuals to be recruited into the military, to advance through promotion, and to be separated or retired from military service. Throughout the history of the armed services, Congress has established some of these criteria based on demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and sexual orientation. Actions by prior congresses and administrations to build a more diverse and representative military workforce have often paralleled efforts to diversify the federal civilian workforce.

Diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity are three terms that are often used interchangeably; however, there are some differences in how they are interpreted and applied between the Department of Defense (DOD) and civilian organizations. DOD's definitions of diversity and equal opportunity have changed over time, as have its policies toward inclusion of various demographic groups. These changes have often paralleled social and legal change in the civilian sector. The gradual integration of previously excluded groups into the military has been ongoing since the 19th century. In the past few decades there have been rapid changes to certain laws and policies regarding diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity in the Armed Forces. Since 2009, DOD policy changes and congressional actions have allowed individuals who are gay to serve openly with recognition for their same-sex spouses as dependents for the purpose of military benefits and opened all combat assignments to women. On June 30, 2016, DOD announced the end of restrictions on service for those transgender troops already openly serving. However, in August of 2017, President Donald J. Trump directed DOD to (1) continue to prohibit new transgender recruits, (2) review policies on existing transgender sevicemembers, and (3) restrict spending on surgical procedures related to gender transition.

Military manpower requirements derive from In the past few decades there have been rapid changes to certain laws and policies regarding diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity – in particular towards women serving in combat arms occupational specialties, and the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals. Some of these changes remain contentious and face continuing legal challenges.

Military manpower requirements derive from the National Military Strategy and are determined by the military services based on the workload and competencies required to deliver essential capabilities. Some argue that to effectively deliver these capabilities a workforce with a range of backgrounds, skills and knowledge is required. In this regard, DOD's pursuit of diversity is one means to acquire those necessary capabilities by broadening the potential pool of high-quality recruits and ensuring equal opportunities for advancement and promotion for qualified individuals throughout a military career. DOD has used diversity and equal opportunity programs and policies to encourage the recruitment, retention, and promotion of a diverse force that is representative of the nation.

Those who support broader diversity and equal-opportunity initiatives in the military contend that a more diverse force is a better performing and more efficient force. They point out that the nature of modern warfare has been shifting, requiring a range of new skills and competencies, and that these skills may be found in a more diverse cross-section of American youth. Many believe that it has always beenFilling these capability needs, from combat medics to drone operators, often requires a wide range of backgrounds, skills and knowledge. To meet their recruiting mission, the military services draw from a demographically diverse pool of U.S. youth. Some have argued that military policies and programs that support diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity can enhance the services' ability to attract, recruit and retain top talent. Other advocates for a diverse force believe that it is in the best interest of the military to recruit and retain a military force that is representative of the nation as a "broadly representative military force is more likely to uphold national values and to be loyal to the government—and country—that raised it." They contend that in order to reflect the nation it serves, the military should strive for diversity that mirrors the shifting demographic composition of civil society.

Some argue that historically underrepresented demographic groups continue to be at a disadvantage within the military and that efforts should be intensified to ensure equal opportunity for individuals in those groups. Some also contend that if the military is to remain competitive with private-sector employers in recruiting a skilled workforce, DOD should offer the same equal-opportunity rights and protections that civilian employees have.

Some who oppose the expansion of diversity and equal-opportunity initiatives have concerns about how these initiatives might be implemented and how they might impact military readiness. Some believereflects the demographics of the entire country.

Some contend that a military that is representative of the nation should also reflect its social and cultural norms. Such observers argue that popular will for social change should be the driving or limiting factor for DOD policies. Others oppose the expansion of certain diversity and equal opportunity initiatives due to concerns about how these initiatives might be implemented. For example, some contend that diversity initiatives could harm the military's merit-based system, leading to accessions and promotions that prioritizeput demographic targets ahead of performance criteria. Some contend that a military that is representative of the nation should also reflect the social and cultural norms of the nation. In this regard, they argue that the popular will for social change should be the driving factor for DOD policies. Others express concern that that the inclusion of some demographic groups is antithetical to military culture and could affect unit cohesion, morale, and readiness—particularly in elite combat units. In terms of equal opportunity and inclusion, some argue that the military has a unique mission that requires the exclusion of some individuals based on, for example, physical fitness level, education attainment, or social characteristics.

Overview

Under Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the authority to raise and support armies; to provide and maintain a navy; and to provide for organizing, disciplining, and regulating them. In the past, Congress has used this authority to establish criteria and standards for recruiting individuals into the military, promoting them, and separating or retiring them from military service. In many cases, Congress has delegated the authority to develop these criteria and standards to the Secretaries of Defense and the Military Departments. However, throughout the history of the armed services, Congress has passed legislation either limiting or expanding requirements for military service based on demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and sexual orientation. In the past decade, there have been rapid changes to laws and policies governing the integration of certain demographic groups in the Armed Forces. Since 2009, these changes have allowed individuals who are gay to serve openly1 and recognized their same-sex spouses as dependents2, opened submarine billets and combat assignments to women3, and have modified policies relating to the service of transgender troops.4 While all career fields are open to women, Congress has not passed legislation that would allow or require draft registration for women.5 In recent years Congress and the Administration have taken actions to build a more diverse and representative militarystandards. Others express concern that the inclusion of some demographic groups is antithetical to military culture and could affect unit cohesion, morale, and readiness. When addressing equal opportunity within the Armed Forces, some further note that the military has a unique mission that requires the exclusion of some individuals based on, for example, age, physical fitness level, education attainment, or other characteristics.

Overview

16 The commission's final report, From Representation to Inclusion: Diversity Leadership in the 21st-Century Military, noted that while great strides had been made in developing a diverse force, women and racial/ and ethnic minorities are still underrepresented in top leadership positions. In May 2011, the commission's report was released, and in August 2011 , then-President Barack Obama issued an Executive Order (EO 13583) calling for a coordinated government-wide initiative to promote diversity and inclusion in the federal workforce. In Section 528 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (P.L. 114-92), Congress reaffirmed a commitment to maintaining a diverse military stating:

Diversity contributes to the strength of the Armed Forces.... It is the sense of Congress that the United States should—(1) continue to recognize and promote diversity in the Armed Forces; and (2) honor those from all diverse backgrounds and religious traditions who have made sacrifices in serving the United States through the Armed Forces.

Military manpower requirements derive from National Military Strategy and are determined by the military services based on the workload required to deliver essential capabilities. The 2015 National Military Strategy highlights the importance of diversity in acquiring those capabilities, stating:

To enhance our warfighting capability, we must attract, develop, and retain the right people at every echelon. Central to this effort is understanding how society is changing… Therefore, the U.S. military must be willing to embrace social and cultural change to better identify, cultivate, and reward such talent.2

In this regard, DOD's pursuit of a diversity management program is one means to broaden the potential pool of high-quality recruits and to retain those individuals who can best fill required roles at every level.

DOD's definitions of diversity and equal opportunity have changed over time, as have its policies towards inclusion of various demographic groups in military service and occupational assignments. In some cases, these changes have come about in response to changes in law. Under Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the authority to raise and support armies; provide and maintain a navy, and to provide for organizing, disciplining, and regulating them. In the past, Congress has used this authority to establish criteria and standards for recruiting individuals into the military, promoting them, and separating or retiring them from military service. Throughout the history of the armed services, Congress has established some of these criteria based on demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and sexual orientation.

The gradual integration of different demographic groups into the military has continued since the 19th century; however, in the past decade there have been rapid changes to laws and policies with regard to diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity in the Armed Forces. Since 2009, DOD policy changes and congressional actions have allowed individuals who are gay to serve openly3 and recognized their same-sex spouses as dependents4, opened all combat assignments to women5, and, as of June 30, 2016, changed policies that restricted transgender troops from serving.6 Some feel that these changes are happening too quickly or should not happen at all citing potential negative impacts on military readiness and unit cohesion. Others argue that DOD's shifting policies reflect broader societal, cultural, and demographic shifts within the United States, and will create a stronger, more effective force.

ThisThis report is intended to support congressional oversight of DOD's diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity programs, policies, and management for uniformed personnel.7 The report starts by giving an overview of recent research on diversity and organizational management to demonstrate why organizations value diversity and what the findings on diversity meansuggest in a military context. The next sections outline DOD's military personnel policies, processes and organizational structure for managing diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity. Following that, the report examines how the concept of diversity and inclusion has evolved overthroughout the history of the Armed Forces and provides a snapshot of the current demographic composition of the military relative to the U.S. civilian population. Finally, the report addresses some of the current legislative and policy issues related to diversity in the Armed Forces.

Why Do Organizations Value Diversity?

Diversity is often defined as the variation of traits within groups of two or more people and may include both traits that are visible (e.g., sex, age, race) and invisible (e.g., knowledge, culture, values) traits. An Internet. An internet search on "diversity initiatives in the workplace," produces more than 1one million results. Given the emphasis placed on diversity by modern organizations it is important to understand why workforce diversity is valued and what that meanscan mean in the context of military personnel management.

Many argue that diversity is a core value of an egalitarian and multicultural society and organizations should seek diversity regardless of its relationship with performance metrics.78 From a human resource perspective, diversity is typically studied with regard to its impact on group dynamics and other factors that contribute to organizational performance. Two key factors that have been studied in both the civilian and military context are

- cohesion: commitment to other members of the group and the group's shared objectives; and

- effectiveness: the ability of the group to efficiently meet its objectives.

Studies on the impact of diversity on these factors have had mixed findings, leading some to argue that diversity is beneficial to organizational success, and others to suggest that it might be harmful.

Diversity and Cohesion

Military cohesion is often considered to be a positive group attribute that contributes to the team's ability to cooperate and perform at high levels under stressful conditions. There are varying definitions of cohesion. In the military context, the 1992 Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces defined it as

the relationship that develops in a unit or group where (1) members share common values and experiences; (2) individuals in the groups conform to group norms and behavior in order to ensure group survival and goals; (3) members lose their personal identity in favor of a group identity; (4) members focus on group activities and goals; (5) unit members become totally dependent upon each other for the completion of their mission and survival; and (6) group members meet all standards of performance and behavior in order not to threaten group survival.8

In this regard, military cohesion is often considered to be a positive group attribute that contributes to the team's ability to cooperate and perform at high levels under stressful conditions.

Some studies have found that higher overall levels of cohesion are associated with individual benefits of increased job satisfaction, retention, and better discipline outcomes.910 Meta-analysis of group performance and cohesiveness has suggested that, on average, cohesive groups perform better than non-cohesive groups.1011 Others note that where observed causal relationships between cohesion and group performance existsexist, it is more often the performance of the group that affects the level of cohesiveness (i.e., unit success leads to a more cohesive unit) rather than the opposite.11reverse.12

Recent studies of group cohesion focus on two ways that group cohesion develops.12

- 13Social cohesion is the extent to which group members like each other, prefer to spend their social time together, enjoy each other's company, and feel emotionally close to one another.

- Task cohesion is the shared commitment among members to achieving a goal that requires the collective efforts of a group.

Some behavioral research has found that interpersonal relationships that lead to social cohesion are established more readily between individuals with similar backgrounds, experiences and demographic characteristics.1314 In addition, some studies have found that teams with high levels of social cohesion have less conflict1415 and stronger support networks that, which may help individuals to better cope with stress.1516 In the military context, those who argue for more homogenous units1617 argue that these units develop stronger interpersonal bonds whichthat provide important psychological benefits and bolster unit resiliency when operating in highly stressful and austere environments.1718 They also argue that "out-group" members—those with different characteristics than the majority of others in the groups—may experience negative individual psychological effects as a result of poor social integration.

Other studies have found shared experiences can contribute to task cohesion and that this type of cohesion is a stronger predictor of group performance than social cohesion.1819 This leads some to argue that the "sameness" of individuals in a military unit is less important than the shared experiences of the unit. In this regard, some argue that military units that operate in an integrated manner can build task cohesion through integrated training.19

Diversity and Effectiveness

Some studies on the effectiveness of small groups have found that the presence of diversity (in particular racial and gender diversity) is associated with better creative problem solving, innovation, and improved decisionmaking.2021 These positive outcomes are sometimes attributed to the broader range of unique perspectives, knowledge, and experience available in diverse groups relative to homogenous groups. In this regard, thoseThose who argue for diversity initiatives in the military argue that a more diverse force has the potential to be more efficient and flexible, and able to meet a broader set of challenges.

Other studies have found that within diverse groups individuals with demographically similar characteristics tend to build strong in-group relationships to the detriment of the larger unit.2122 The presence of demographic "in-groups" has been found in some circumstances to negatively affect group productivity, particularly if active "fault lines" or biases exist between subgroups.2223 Those who argue against the integration of certain subgroups suggest that there are pervasive cultural biases that can contribute to interpersonal friction within military units and could distract from the unit's ability to perform under stress.

Diversity Management

While the direction and magnitude of the effects of diversity on group performance remain debatable, there is a wide body of literature that links the performance of diverse groups to leadership and management.2324 Among human resource professionals in the public and private sectors, the focus in workforce management has shifted from diversity acquisition (e.g., affirmative action and hiring quotas) to diversity management. Under the previous philosophy, employers set targets for accessions based on race, sex, or other attributes in order to bolster historically under-representedunderrepresented groups. More recent diversity management philosophies focus on building organizational culture and policies to better attract a diverse workforce and to accommodate career development for employees with different backgrounds.

Diversity and the Civil-Military Relationship

Given the U.S. military's unique role in society there are additional reasons why DOD might value diversitythat diversity could be of value within the defense establishment. In the military, the value of diversity is sometimes discussed in the contextas a facet of the civil-military (civ-mil) relationship. This relationship is explained by someSome explain this relationship as a trinity of civilian leadership, civil society, and military servicemembers.2425 Civilian leadership ultimately decides how to resource and employ the military. These decisionmakers are influenced by civilian society (their constituents). In an all-volunteer force, recruits are drawn from civil society. Some portion of civil society serves, has served, or is directly affected by those who serve. The strength of the relationship between civil society and those who serve has been tied to the willingness of a society to enter and engage in conflict, to accept advice from military leadership, and to provide resources to military forces.25 On the flip side, a military leadership that is disconnected from society may question the legitimacy of civilian leadership and decisionmaking in military matters.26

In 2015, less than 1% of the American population was serving on active duty, compared to 8.6% in World War II.27 As a consequence, fewer Americans know someone who is serving or has served. In this regard, some would argue that a diverse force that is representative of the nation is important to build stronger civ-mil relationships across all geographic, socio-economic, and demographic groups.

How Does DOD Define Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity?

On the other end, civilian leaders oversee the implementation of national security policies and hold military leaders accountable. One concern many have is that a cadre of military leaders who lack meaningful connections with civil society could question the legitimacy of civilian authority in military matters.27 In the context of such concern, advocates for a diverse force believe that such a force is in the best interest of society because "a broadly representative military force is more likely to uphold national values and to be loyal to the government—and country—that raised it."28 Another argument for demographic representation is based in social equality. From this perspective, many believe that the risks of military service should be shared equally among all qualified citizens, and not disproportionately the burden of certain geographic, demographic, or socioeconomic groups. Others note that military service confers various benefits, opportunities, and status within society (e.g., veterans' preference in federal or state hiring29, education benefits, specialized training). As a result, some social equality advocates argue that all qualified individuals should have equal opportunities to participate, earn the benefits, and advance within the military. Diversity, inclusion, and equal-opportunity initiatives often go hand-in-hand in workforce management. Although the three terms are often used interchangeably, there are some key differences in how they are interpreted and applied. While "diversity" is primarily used to discuss the variations in visible and invisible traits among employees in an organization, "inclusion" or "inclusiveness"democratic populous to hold civilian leaders accountable for decisions to enter and engage in conflict and to expend national resources to sustain a military force.26

"Equal opportunity" is used in the context of legal protections for individuals or groups of individuals from forms of discrimination in the workplace. Policies that promote diversity and equal opportunity are typically complementary and maycan help build an organizational culture of inclusiveness. In June 2015, DOD revised its policies and definitions for diversity and equal opportunity. DOD's current polices expand classes of protected individuals covered by the military equal opportunity definition to include sexual orientation.28

Diversity and Inclusion Policy

DOD's current diversity policies and plans stem from congressional and administration actions between 2008 and 2011. In the Duncan Hunter National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2009 (P.L. 110-417, Section 596), Congress authorized the creation of the Military Leadership Diversity Commission (MLDC). The commission's charter includes 16 tasks, one of which was to "develop a uniform definition of diversity to be used throughout DOD congruent with the core values and vision of DOD for the future workforce."2930 In 2011, the commission released its final report. In the same year, then-President Obama issued an Executive Order (EO 13583) calling for a coordinated government-wide initiative to promote diversity and inclusion in the federal workforce.3031

In 2012, DOD issued a five-year Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan that drew on many of the recommendations from the MLDC report and outlined three overarching goals intended to align with goals in the Government-Wide Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan published by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) (see Table 1).

|

OPM Strategic Goals |

DOD Strategic Goals |

|

Workforce Diversity. Federal agencies shall recruit from a diverse, qualified group of potential applicants to secure a high-performing workforce drawn from all segments of society. |

Employ an aligned strategic outreach effort to identify, attract, and recruit from a broad talent pool reflective of the best of the nation we serve. Position DOD to be an "employer of choice" that is competitive in attracting and recruiting top talent. |

|

Workplace Inclusion. Federal agencies shall cultivate a culture that encourages collaboration, flexibility, and fairness to enable individuals to contribute to their full potential and further retention. |

Develop, mentor, and retain top talent from across the total force. Establish DOD's position as an employer of choice by creating a merit-based workforce life-cycle continuum that focuses on personal and professional development through training, education, and developing employment flexibility to retain a highly |

|

Sustainability. Federal agencies shall develop structures and strategies to equip leaders with the ability to manage diversity, be accountable, measure results, refine approaches on the basis of such data, and engender a culture of inclusion. |

Ensure leadership commitment to an accountable and sustained diversity effort. Develop structures and strategies to equip leadership with the ability to manage diversity, be accountable, and engender an inclusive work environment that cultivates innovation and optimization within the Department. |

Sources: DOD Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan, 2012-2017; Government-Wide Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan, 2011.

Note: OPM is the U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

The DOD strategic plan placed an emphasis on diversity management over the workforce life-cycle (from recruitment to retirement) and highlighted the role of leadership in establishing an inclusive organizational climate. The plan also established new definitions of diversity and diversity management that apply to both uniformed personnel and DOD civilians:

Diversity31: All the different characteristics and attributes of the DOD's total force, which are consistent with DOD's core values, integral to overall readiness and mission accomplishment, and reflective of the Nation we serve.

Diversity Management: The plans made and programs undertaken to identify and promote diversity within the DOD to enhance DOD capabilities and achieve mission readiness.32

DOD's definition of diversity encompasses not only demographic characteristics, but also different backgrounds, skills, and experiences. The strategic plan does not outline targets or quotas for the recruitment, retention, or promotion of historically underrepresented demographic groups, nor does it prioritize diversity at the expense of military readiness. While DOD does not establish official diversity targets based on demographic profiles,33 , an inherent goal within the current definition is that the characteristics of the force should reflect the demographic characteristics of the U.S. population.34 Consistent with this, DOD regularly collects and reports on the demographic profile of the force which can then be compared to the demographic profile of the civilian population.

Military Equal Opportunity Policy

Equal opportunity typically refers to nondiscrimination protections for certain classes of individuals. DOD has civilian and military employees and operates both a Civilian Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Program and a Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) Program.3435 Military equal opportunity policies generally follow the precepts set in civilian civil rights law; however, many statutes and regulations that are applicable to civilian employment are not applicable to military service. The sources of uniformed servicemembers' rights, and restrictions thereon, include the Constitution, statute—including the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ)—DOD and service-level policies and regulations, and Executive Orders.

Congress has the authority to establish qualifications for and conditions of service in the armed forces. Whereas civilian law prevents discrimination based on age3536 or disability3637, the military is allowed, and in some cases compelled, by law to deny service opportunities to those unable to meet certain physical standards, and those above a certain age. For example, by statute,3738 a commissioned officer may be appointed only if he or she is "able to complete 20 years of active commissioned service before his sixty-second birthday ... is physically qualified for active service ... and has such other special qualifications as the Secretary of the military department concerned may prescribe by regulation."3839 Likewise, the law specifies persons who are ineligible to enlist.39

The Secretary of Defense has the general authority40 to prescribe policies and regulations for DOD employees, including those regulations pertaining to equal opportunity and nondiscrimination.41 In DOD's 2015 revision to its policy, the MEO definition more closely mirrors the civilian EEO definition. Another change in 2015 expanded the protected classes of individuals to prevent unlawful discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. In announcing this change, then-Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter stated

We have to focus relentlessly on the mission, which means the thing that matters most about a person is what they can contribute to it ... we must start from a position of inclusivity, not exclusivity.... Anything less is not just wrong—it's bad defense policy, and it puts our future strength at risk.4142

Table 2 shows a comparison of DOD's equal opportunity definitions for civilian employees and military servicemembers.4243 In 2016, DOD changed the MEO definition was changed to include gender identity under those protected from discrimination and harassment.

|

DOD Civilian Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Definition |

Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) Definition |

|

The right of all DOD employees to apply, work, and advance on the basis of merit, ability and potential, free from unlawful discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation when based on sex stereotyping), disability, age, genetic information, reprisal, or other unlawful factors. |

The right of all servicemembers to serve, advance, and be evaluated based on only individual merit, fitness, capability, and performance in an environment free from |

Source: Department of Defense, Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity in the DOD, DODD 1020.02E, June 8, 2015, Incorporating Change I, Effective November 29, 2016June 1, 2018.

NotesNote: DODD 1020.02E states that the civilian EEO program is governed by 42 U.S.C. §§2000e through 2000e-17, part 1614 of Title 29 C.F.R., chapter 14 of 29 U.S.C., and 5 U.S.C. §§2302(b)(1) and 7201.

Discrimination and harassment as described in military issuances include sexual harassment, hazing, intimidation, disparaging remarks, or threats against other servicememberservicemembers or civilians based on protected characteristics. Harassment also includes creating an intimidating or hostile work environment for individuals on the basis of protected characteristics. Harassment by military personnel may result in administrative actions (e.g., letters of reprimand, counseling, or low marks on annual performance evaluations) and may also be punishable under the UCMJ.43

How Does DOD Manage Diversity and Equal Opportunity?

DiversityDOD oversees diversity management and equal opportunity programs are overseen by DOD and implemented bywhile the military departments implement them. Programmatic components include research and data collection, training, and processes and procedures for military equal opportunity complaint resolution.

Office of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity (ODMEO)

The Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (ODEI)

The Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (formerly the Office of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity, (ODMEO) is the DOD organization responsible for promoting diversity in the DOD workforce, and it is overseen by the.45 The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. It was first established in 1994 as the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Equal Opportunity. ODMEO oversees this office. ODEI has oversight authority for the DOD Diversity and Inclusion Management Program, the DOD Military Equal Opportunity Program, the DOD Civilian Equal Employment Opportunity Program, and the DOD Civil Rights Program, and Harassment Prevention and Response in the Armed Forces Program. The Director . The Director of ODMEO also provides oversight and guidance to the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute (DEOMI). DOD component heads have oversight of MEO programs and are responsible for making required reports to the Secretary of Defense and Congress.44

Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute (DEOMI)

In 1971, DOD established the Defense Race Relations Institute (DRRI) with a mandate to

conduct training for Armed Forces personnel designated as instructors in race relations, develop doctrine and curricula in education for race relations, conduct research, perform evaluation of program effectiveness, and disseminate educational guidelines and materials for utilization throughout the Armed Forces.45

In 1979, DRRI became the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute as the organization evolved to address not only race, but other diversity and equal opportunity issues in DOD. Today DEOMI offers resident, nonresident and e-learning courses geared toward equal- opportunity advisors, counselors, and program managers across all military departments and components. DEOMI also conducts research to support policy-making and training and development programs, and provides a range of online resources for diversity management and equal opportunity programming.

DEOMI's Research Directorate administers the Defense Equal Opportunity Climate Survey (DEOCS). This survey is intended to be a tool to help commanders better gauge the morale in their units, identify potential issues or areas of strength, and improve their organizational culture. It measures factors associated with organizational effectiveness, equal opportunity/fair treatment, perceptions of sexual harassment, and sexual assault prevention and response (see Table 3). The DEOCS may be administered to any DOD agency and is used for both uniformed military personnel and civilian employees.

|

Organizational Effectiveness |

Equal Opportunity/ Fair Treatment |

Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) |

|

|

|

Source: DOD Sample DEOCS 4.0 Survey, DEOMI, January 1, 2014.

Note: The survey also allows for the addition of locally developed questions and allows respondents to provide written comments directly associated with discrimination/sexual harassment/SAPR.

The DEOCS is used at the unit level to establish a baseline assessment of the command climate Public Law Description P.L. 112-239, FY2013 NDAA Section 572: Requires commander of each military command to conduct a climate assessment for the purposes of preventing and responding to sexual assaults within 120 days of assuming command and at least annually thereafter. FY2014 NDAA Section 587: Requires results of command climate surveys to be provided to the commander and the next higher up in the chain of command and requires that a failure to conduct a command climate survey be noted in the commander's performance evaluation. Section 1721: Requires the Secretaries of the military departments to track compliance with statutory command climate survey requirements. Section 1751: Expresses a sense of congress regarding the importance of establishing a command climate where criminal activity can be reported free from the fear of retaliation or ostracism. Source: Public Law. and subsequent. Subsequent surveys are intended to track progress relative to the baseline. In recent years there has been a series of legislative initiatives that have enhanced requirements for the administration of command climate surveys (see Table 4). Many of these changes have beeninitiatives have come in response to growing concerns about command responses to sexual harassment/ and assault reports.48

Table 4. Selected Legislation for Command Climate Surveys

Military Departments

In practice, the military departments manage their own diversity programs and initiatives. MEO training, prevention, complaints, and resolutions are handled at the unit level through the chain of command. It is the commander's responsibility to establish a climate of inclusiveness and equal opportunity.4649 Accountability for senior leaders is achieved through command climate assessments (DEOCs) and through evaluations of character, and organizational climate/equal opportunity on performance evaluations. For example, "character"character is rated on senior enlisted evaluations for E7-E9's in the Navy. A "Greatly Exceeds Standards" rating for character requires that the individual "seamlessly integrate diversity into all aspects of the command," while a "Below Standards" rating describes the individual as "demonstrates exclusionary behavior, fails to value differences from cultural diversity."47

How Have the Definition and Treatment of Protected Classes Evolved in the Armed Forces?

DOD's current definition of Military Equal Opportunitymilitary equal opportunity protects servicemembers from unlawful discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex (including gender identity) or sexual orientation. However, throughout the history of the Armed Forces, these currently protected classes have beenwere excluded to varying degrees from military participation and occupational assignments by policy and statute. The history of integration in the military is detailed and often dependent on the political, social, and cultural context of the timeera. This section describes selected policy and statute changes made by Congress and the military statutory and policy changes that affected the treatment of various demographic groups over time. The following sections will also provide a snapshot of the current demographic profile of the Armed Forces.

Racial/Ethnic Inclusion;: Background and Force Profile

Racial minorities have volunteered or been drafted for service since the time of the American Revolution;4851 however, the military was a racially segregated institution until the mid-20th century. Under the widely accepted "separate but equal" philosophy of the time, these segregation policies were not considered to be unjust by many senior military and government officials. However, civil rights activists rejected this notion, and pushed for full racial integration across all segments of society, including the Armed Forces. Even as policy and statute changed over time to remove occupational and assignment barriers to racial/ethnic minorities, concerns about discrimination and equal opportunity have persisted.

The Civil War to World War II, Racial Segregation

The recruitment of racial minorities into the service through most of the 1800s and 1900s was not driven by a desire for a "diverse force," but instead was drivendiversity, but rather by practical manpower requirements. During the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, General Andrew Jackson's Army included both "Free Men of Color," and Choctaw Native Americans.4952 During the Civil War, approximately 186,000 black Americans served in the Union Army as part of sixteen segregated combat regiments, and some 30,000 served in the Union Navy. Following the Civil War, as part of what is commonly known as the Army Reorganization Act of 1866, Congress authorized the creation of permanent "colored" units consisting of two cavalry and four infantry regiments.5053 The act also authorized the recruitment and enlistment of 1,000 Native Americans to act as scouts. While the creation of these units guaranteed career opportunities for specific racial minorities, it also introduced an era of institutionalized segregation in the armed services.

In 1896, the Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson upheld state laws authorizing racial segregation under a "separate but equal" doctrine. Following the ruling, states proceeded to enact a series of segregation-based laws and the military services also began morebegan active implementation of racial segregation policies. Due to pressing needs for additional manpower in the Army, black soldiers made up approximately 11% of the Army's total strength in World War I and 13% of all those conscripted (in racially separate "white" and "colored" draft calls).5154 Hispanics, Native Americans, and Asian Americans were mostly drafted as "whites".52."55 However, there was confusion in some states as to how to treat draftees of Asian ethnicity. Chinese surnames appeared on both black and white draft lists.56 While black soldiers in the Army were often directed towards unskilled combat support or service support jobs, many also served as frontline combat troops.

During World War II, the War Department again issued separate draft calls for black and white servicemembers and maintained segregated training and unit assignments. The Army upheld a quota policy for the recruitment of black soldiers with a ceiling of 10% of total recruits.5357 In this era, the distribution of white and black servicemember between the officer and enlisted ranks and occupational specialties suggested some inequities in accession and assignment policies. In 1941, black soldiers in the Army accounted for 5% of the Infantry and less than 2% of the Air Corps, whereas they accounted for 15% of the less-prestigious Quartermaster Corps5458 and 27% of unassigned or miscellaneous detachments.5559 About 2% of the Navy was black, and with the exception of six men rated as regular seaman, all of them were enlisted steward's mates. None were officers.5660 At peak WWII manpower strength in 1945, black servicemembers accounted for 7.2% of the total military force but only 0.6% of the officer corps.5761 Army practices did not allow black officers to outrank or command white officers in the same unit, and some commanders preferred to assign white officers for command of black units.58

Although Asian-Americans had served in previous conflicts, during WWII there was confusion in some states as to how to treat draftees of Asian ethnicity, and Chinese surnames appeared on both black and white draft lists.59 It is estimated that approximately 20,000 Chinese Americans served in the Armed Forces during the war.60 62

Given Japan's role in the war there was a general public suspicion of Japanese Americans and some already serving in the military were removed from active duty or discharged.6163 However, approximately 6,000 Nisei (first-generation, American-born Japanese) served as interpreters or linguists in the war with about 3,700 serving in combat.6264 In addition, the Army formed a segregated unit comprised of about 4,500 Japanese-Americans within the 442d Regimental Combat Team (RCT) that fought in Italy and Central Europe.6365

Desegregation in the Truman Era

In December 1946, in response to what was seen as a worrisome increase in racial violence and tension across the United States, President Harry Truman issued an Executive Order establishing the President's Committee on Civil Rights.6466 The commission's mandate was to examine civil rights for all citizens; however, they did make certain recommendations for the military services. The commission's report, To Secure These Rights, noted that blacks and other minority servicemembers faced many barriers to equal treatment both within and outside the military. The commission advocated for (1) full racial integration within the military, (2) a ban on discrimination based on race or color, and (3) award of officer commissions and promotions based solely on merit.

In 1948, during his campaign for reelection, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which set in motion a purposeful desegregation effort.65

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.6668 This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.

The order also established the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Forces under chairmanship of Charles Fahy to understand the potential impact of integration on military efficiency. During the commission's inquiry, some military leaders advocated for maintaining the status quo due to concerns about inefficiencies that might arise from "impaired morale in mixed units."6769 The Fahy Committee's final report, released in 1950, expressed serious doubts about military officials' claims that integration would negatively affect morale and efficiency, finding instead evidence that existing segregation policies were contributing to inefficiencies through unfilled billets, training backlogs, and less capable units. In their conclusion, the committee stated:

As a result of its examination into the rules, procedures, and practices of the armed services, both past and present, the Committee is convinced that a policy of equality of treatment and opportunity will make for a better Army, Navy, and Air Force. It is right and just. It will strengthen the nation.68

Between 1949 and 1950 the military departments changed their policies regarding minority races to reflect the recommendations of the Fahy Committee and to echo the language of President Truman's Executive Order that there should be "equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons ... without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin."6971 By this time, Asian-Americans were no longer serving in segregated units; however, black units were still segregated.

The manpower needs of the Korean War (1950-1953) catalyzed racial integration in the services. Under pressure to rapidly build up and deploy forces, the Army lacked the time and resources to continue to operate separate training pipelines for black and white soldiers. On the battlefield, Army and Marine Corps commanders began assigning black soldiers to replace losses in white combat units by necessity. However, senior leaders in the Army were reluctant to change official policies, as stated by Army Lt. General Edward M. Almond in opposition to changes:

I do not agree that integration improves military efficiency; I believe it weakens it. I believe that integration was and is a political solution for the composition of our military forces because those responsible for the procedures ... do not understand the characteristics of the two human elements concerned... This is not racism—it is common sense and understanding. Those who ignore these differences merely interfere with the combat effectiveness of combat units.70

In response to political pressures for change, the Army initiated two scientific research studies of the performance of integrated units; one conducted internally by the Army G-1, and one through a contracted agency that was code named "Project Clear." Both studies concluded that contrary to widely held beliefs, unit performance was not negatively affected by integration, and that the practice of segregating units was in fact damaging to military effectiveness.7173

The Army dropped its 10% ceiling on the recruitment of black soldiers in 1950, and by 1953. By October 1953, basic training and unit assignments were no longer segregated, and the Army announced that 95% of African-American soldiers were serving in integrated units.74.72 In 1951, the Marine Corps announced a policy of racial integration.7375 By 1954, then-Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson announced that the last all-black active duty unit had been abolished. However, some Reserve and National Guards remained segregated or closed to black entrants into the 1960s.7476

Civil Rights Movement and Anti-Discrimination Policies

While DOD had announced the full integration of the active duty military in 1954, segregation was still widespread in National Guard and Reserve units and discrimination on military installations and in surrounding communities persisted.7577 In 1962, President John F. Kennedy authorized the President's Committee on Equal Opportunity in the Armed Forces to be chaired by Gerhard A. Gesell. The commission was the first to address equal opportunity in the forces since the Fahy Commission in 1950; its mandate was to determine the following.

1. What measures should be taken to improve the effectiveness of current policies and procedures in the Armed Forces with regard to equality of treatment and opportunity for persons in the Armed Forces?

2. What measures should be employed to improve equality of opportunity for members of the Armed Forces and their dependents in the civilian community, particularly with respect to housing, education, transportation, recreational facilities, community events, programs and activities?76

The commission found that while armed services policies were not discriminatory as written, there was a need for the military to improve recruitment, assignment, and promotion practices to achieve equal treatment of black servicemembers.7779 In addition, the commission noted particular hardships imposed on black servicememberservicemembers and their families when assigned to or transferred to installations in communities with high levels of segregation and discrimination in education, housing, transportation, and employment. For example, one-fourth of all Army and Navy installations were located in communities with segregated public schools.7880 The commission noted that black servicemembers and their families were

daily suffering humiliation and degradation in communities near bases at which they are compelled to serve ... community conditions are a constant affront and constant reminder that the society they are prepared to defend is a society that depreciates their rights to full participation as citizens.79

The commission's finding suggested that base commanders were not taking an aggressive role in identifying and addressing racial discrimination on base and within the communities. Some of the key recommendations of the commission were as follows.

- Expand and clarify the installation commander's role with respect to discrimination in the community.

- Develop mechanisms to tie an officer's performance ratings to their ability to establish a climate of equal opportunity.

- Initiate mandatory command training programs on discrimination and equal opportunity.

- Build biracial community working groups.

- Allow installation commanders to impose economic sanctions (boycotts/bans) on local businesses by prohibiting servicemembers from patronizing establishments that were racially discriminatory.

8082

- Establish equal opportunity offices and appoint officials for each of the military departments.

In response to the commission's recommendation, then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara8183 issued a new DOD policy in July 1963 to

conduct all of its [DOD's] activities in a manner which is free from racial discrimination, and which provides equal opportunity for all uniformed members and all civilian employees irrespective of their color.82

One year after the DOD's policy issuance, the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act of 196483 (P.L. 88-352) that outlawed discrimination or segregation on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.8485 DOD responded by issuing a new policy that prescribed policies and procedures for processing servicemember requests for legal action under the new law in cases of discrimination faced off-base.8586

The Vietnam War and Efforts to Improve Race Relations

Despite the DOD's new policy in response to the Gesell Commission recommendations, the 1960s brought an era of conflict abroad and social unrest at home. In 1965 the U.S. deployed combat troops to Vietnam. While in previous wars, recruitment of blacks was limited by quotas or segregation policies, during Vietnam there was a perception that blacks were disproportionally drafted, sent to Vietnam, assigned to serve in high-risk/high-casualty combat units, and being killed or wounded in battle.86 Feeding this perception were DOD statistics reported by the media indicating that between 1961 and 1966, blacks composed approximately 11% of the general population but accounted for nearly one-fourth of all enlisted Army personnel losses in Vietnam.87 In addition, the87

DOD draft data from 1964 show that among men aged 26-29, a greater percent of nonwhite males (50%) had been found unfit for service than white males (25%). However, of those who were qualified, 30.2% of the black male population was drafted compared with 18.8% of the white population.88 The final report of the National Advisory Commission on Selective Service88 noted that in October 1966 only 1.3% of local draft board members were black and state draft boards had zero black members.89 This lack of representation fed perceptions of favoritism towards white registrants. One of the recommendations of the commission was that local draft boards should "more realistically represent all elements of the public they serve.", including ethnic, of the population of the country."90

Studies following the Vietnam era have found little evidence of sustained or widespread institutional racism in draft and casualty statistics. As shown in Table 4, bydecisions. Generally, studies have found bias in draft deferments and inductions based on socioeconomic factors. Casualty statistics give a mixed picture as well. Black casualties in the early years of the war accounted for 22.4% of all troops killed in action in 1966; nevertheless, by 1973, at the end of U.S. military involvement in the war in 1973, total black fatalities were approximately 12.4% of the total casualties (see Table 5). In 1973. In that year, black servicemembers accounted for 18.4% of the active component Army enlisted corps and 16.9% of Marine Corps enlisted.89 Where studies have found bias in draft deferments and inductions is on socio-economic factors.

|

Race |

Number of Fatalities |

Percent of Total Fatalities |

|

White |

49,830 |

85.5% |

|

Black or African American |

7,243 |

12.4% |

|

Other |

1,147 |

2.0% |

|

Total |

58,220 |

100% |

Source: Vietnam Conflict Extract Data File of the Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS), National Archives and Records Administration, http://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html#race.

Notes: Figures include those who died as a result of the Vietnam War and include deaths between June 8, 1956, and May 28, 2006. The "Other" category under race includes Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Hispanic (one race), and Non-Hispanic (more than one race).

Between 1968 and 1970, perceived patterns of racial discrimination in both the military and surrounding communities contributed to an uptick in recorded violent incidents at military installations in the U.S. and overseas.9092 DOD ultimately was compelled to act after a 1971 incident at Travis Air Force Base, California, where an altercation in the barracks between a black Airman and a white Airman escalated into riots that ended in 135 arrests, 10 injuries, athe death of a civilian firefighter, and significant property damage.9193 In 1971, in response to the incident at Travis AFB and the recommendations of an inter-service task force on racial relations, DOD established the Race Relations Education Board, required race relations training for all servicemembers, and opened the Defense Race Relations Institute (DRRI)9294 on Patrick Air Force Base, Florida.

On April 5, 1972, following concerns about discrimination in the military justice system, then-Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird established the Task Force on the Administration of Military Justice in the Armed Forces to

- identify the nature and extent of racial discrimination in the administration of military justice;

- identify and assess the impact of factors contributing to disparity in punishment rates between racially identifiable groups;

- identify and assess racial patterns or practices in initiation of charges against individuals; and

- recommend changes to enhance equal opportunity for servicemembers.

9395

The Task Force found evidence of both intentional and unintentional discrimination toward racial minorities in the military justice system stating,

The Task Force believes that the military system does discriminate against its members on the basis of race and ethnic background. The discrimination is sometimes purposive; more often, it is not. Indeed, it often occurs against the dictates not only of policy but in the face of determined efforts of commanders, staff personnel and dedicated service men and women.94

The report proposed enactment of a specific legislative provision in the UCMJ to ban discrimination. However, this recommendation was not adopted and the UCMJ does not currently have any specific provision banning discrimination. The adoption of new anti-discriminationantidiscrimination policies, programs and protections along with the advent of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973 helped to alleviate some of the racial tensions that had plagued the Armed Forces for the better part of the 20th Centurycentury. Despite great strides in racial equality and nondiscrimination, some concerns about the treatment of and opportunities for racial minorities have persisted into the 21st century.95

Is the Racial/Ethnic Profile of the Military Representative of the Nation?

For over 50 years DOD has not prohibited qualified U.S. citizens of different races or ethnicity from serving in any occupation in the military. Recent concerns by DOD and others have focused on whether the racial/ethnic composition of the military is representative of the broader society. The military's racial and ethnic profile has changed littleshifted slightly over the past two decades, with approximately two-thirds of active duty members identifying as "white" and roughly one-fifth as black (see Figure 1). The percentage of Hispanic servicemembersfew decades. There was a surge in black enlistments in the late 1970s and 1980s, most significantly in the Army where black representation was above 30% from 1979 to 1981.99 Black representation declined to approximately 20% of the active component throughout the 1990s, and has dipped below 20% in the past decade (see Figure 1). However, black representation in the Army remains above 20% and overall, the black members are overrepresented in the Armed Forces relative to the total U.S. population. The percentage of Hispanic servicemembers has grown consistently in the past two decades, and has doubled since 1997. This is consistent with the growth of the Hispanic population in the United States and its higher propensity to enlist, which sometimes varies by racial/ethnic group. Between 2004 and 2010 as reported by youth surveys, Hispanic youth (male and female) had a higher average aided propensity96 for enlistment than their white or black counterparts.97

|

|

Source: Defense Manpower Data Center. Notes: Data includes all active duty members (officer and enlisted). Race and Hispanic origin are self-identified. The concept of race is separate from the concept of Hispanic origin. Hispanic may be more than one race (e.g., Hispanic and White or Hispanic and Black). |

According to data from the Defense Manpower Data Center, in 2017, thethe active duty enlisted corps wasis more racially diverse than the U.S. resident population with nonwhite servicemembers accounting for roughly one-third of all active duty enlisted and nearly 40% of all senior enlisted (see Table 523% of the total U.S. population ages 18-64. (see Table 6). Among enlisted minority groups in the active and reserve components, Asian and Hispanic servicemembers are underrepresented relative to the U.S. population and blacks and Pacific Islanders are overrepresented.

However, in the officer corps, and especially at the senior leadership level, racial and ethnic minorities are underrepresented relative to the enlisted corps and the U.S. population. For example, those of Hispanic origin account for about 17.5(age 18-64) account for approximately 18% of the population and 1718% of the active duty enlisted corps.100 However, Hispanic officers Hispanic servicemembers account for roughly 8% of the officer corps and less than 2% of General/Flag officers. It is important to note, whenWhen considering the demographic makeup of the officer corps, there areit is important to note that certain requirements that must be met to become a commissioned officer. For example, the attainment ofattaining a bachelor's degree (or higher) is a requirement for the appointment and advancement of most officers. Looking again at the Hispanic population, the percent of Hispanics in the officer corps is closer in terms of percentage of the pool of eligible officer candidates by educational attainment. While, those of Hispanic origin98101 account for nearly 18% of the U.S. population, they account for roughly 8% of all post-secondary degree holders (see Table 67).

Table 56. Race and Ethnic Representation in the Active Duty and Selected ReserveComponent and U.S. Population

As of August 2017

|

Active Duty | Rank and Grade |

White |

Black |

Asian |

Other Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander |

Multi/ Unknown |

Hispanic* |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

General/Flag Officer (O-7 and above) |

87. |

8. |

2.1% |

0.3% |

|

1. none | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Officer (all) |

2.4% 2.1% Officer (all) 77.3% 8.1% 5.2% 10.1% 0.5% 8.2% 7.6% Warrant Officer 69.0.% 16.0% 3.1% 0.8% 0.6% 10.4% 11.6% Senior Enlisted (E-7 and above) 63.1% 19.1% 3.8% 1.3% 1.2% 11.5% 14.3% Enlisted (all) 67.4% 18.5% 4.3% 1.3% 1.3% 7.3% 17.5% Total Active Duty 69.1% 16.8% 4.4% 1.2% 1.1% 7.5% 15.8% |

8.7% |

4.9% |

1.2% |

8.3% |

7.7% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Warrant Officer |

66.7% |

17.8% |

3.2% |

1.4% |

10.8% |

11.3% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Senior Enlisted |

62.3% |

20.1% |

3.9% |

2.3% |

11.4% |

14.0% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Enlisted (all) |

67.0% |

19.1% |

4.4% |

2.6% |

7.1% |

17.0% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total Active Duty |

68.7% |

17.3% |

4.5% |

2.3% |

7.3% |

15.4% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Selected Reserve |

General/Flag Officer (O-7 and above) |

91.3% |

4.0% |

2.3% |

0.8% |

1.7% |

3.0% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Officer (all) |

74.8% |

9.8% |

4.4% |

1.0% |

5.8% |

6.4% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Warrant Officer |

80.3% |

8.7% |

2.4% |

0.9% |

2.9% |

6.5% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Senior Enlisted |

76.1% |

14.7% |

2.4% |

1.3% |

5.5% |

9.5% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Enlisted (all) |

72.7% |

17.8% |

4.2% |

1.5% |

3.7% |

12.5% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total Selected Reserve |

73.9% |

16.5% |

4.2% |

1.5% |

4.0% |

11.5% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Resident Population (age 18-64, estimated) |

76.6% |

13.7% |

13.7% |

1. |

2. |

17. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources: Officer and Enlisted figures are as reported by the Defense Manpower Data Center, August 2017May 2018. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States, States, and Counties: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 20162017, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Release Date: July 1, 20162017.

Notes: Race and Hispanic origin are self-identified. ** The concept of race is separate from the concept of Hispanic origin. Hispanic may be more than one race (e.g., Hispanic and White or Hispanic and Black). Percentages for race should not be combined with percent Hispanic. The "Other" category includes Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders, and American Indian and Alaskan Natives.

Table 67. Racial/Ethnic Representation Among Post-secondary Degree Holders

U.S. Population andcompared with Active Duty Officer Corps

|

Race/Ethnic Origin |

% of Resident Population (age 18-64) |

% of Total Active Duty Officer Corps |

% of all Post-secondary Degree Holders (18 years and above) |

|

White |

76. |

|

|

|

Black |

13.7% |

8. |

8. |

|

Asian |

6. |

|

|

|

Hispanic* |

17. |

7. |

|

Sources:Sources: Officer and Enlisted figures are as reported by the Defense Manpower Data Center, August 2017May 2018. Educational Attainment of the Population 18 Years and Over, by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 20162017 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

Notes: Degree holders include Bachelor's, Master's, Professional, or Doctoral Degree.

* The concept of race is separate from the concept of Hispanic origin, Hispanic may be more than one race (e.g., Hispanic and White or Hispanic and Black).

Attaining the highest officer rankings (Admiral or General Officer) requires that individuals be competitively selected for competitively selected for promotion when eligible or "in zone" at different stages of their careers.99102 A 2014 study of Air Force promotion rates found no evidence of differential rates of promotion by race/ethnicity for approximately 93% of the cases observed, suggesting overall fairness in the promotion system.100 However103 However, where disparities existed, whites had more favorable promotion outcomes than African Americans or Hispanics or Hispanics with similar characteristics.101.104 The authors of the study found that career success is cumulative and that racial and ethnic minorityminority officers, on average,, were less likely to have achieved the early career milestones that are correlated with improved promotion prospects.102105

Other potential factors in racial diversity among senior military leaders are career field preferences and career field assignment policies. In a 2009 study of assignments and preferences, of Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) cadets, researchers found that African American cadets tend to prefer Combat Service Support branches whereas white cadets tended to gravitate towards Combat Arms branches.103106 Other studies have noted that racial minorities, particularly African Americans, are also underrepresented in Special Operations Forces (SOF) relative to their source population. For example, a 1999 RAND study found that black servicemembers were particularly underrepresented in SOF, compared to the source population.104107 This report cited both structural barriers (e.g., swimming requirements, Armed Service Vocational Aptitude Battery cutoff scores) and perceptual barriers (e.g., perceived racism, lack of knowledge/support in minority community for SOF careers, minority preferences for occupations with less risk or more civilian job transferability).105

Inclusion of Women,: Background and Force Profile

As with racial and ethnic groups, women have played a role in supporting and serving in the U.S. Armed Forces since the Revolutionary War. However, laws and policies regarding how many women may serve, their authorized benefits, and types of assignments have changed over the history of women's service. While the ceiling on the percentage of women allowed to serve in the military was repealed in 1967, women continued to be prohibited from serving in many occupations by statute and policy—particularly those occupations related to combat arms specialties.106109 In 1993, all laws prohibiting females from serving in any occupation were repealed; however, by DOD policy, women were still excluded from serving in units or occupations involved in direct ground combat. In 2013, the DOD rescinded the Direct Ground Combat and Assignment Rule, which had excluded women from assignment to units below the brigade level whose primary mission was to engage in direct combat on the ground. This rule had the effect of prohibiting women from assignments to certain combat arms occupations and units (e.g., infantry) and its removal was the last major policy barrier to women's service in all occupational fields. The services were required to fully implement this change no later than January 1, 2016; however, they were allowed to request a waiver from the Secretary of Defense for further exclusion of women from certain positions.107110 On December 3, 2015, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter ordered the military to open all combat jobs to women with no waivers or exceptions.108

Women's Participation in World War I and World War II

The first uniformed women served in the Army Nurse Corps (established in 1901) and the Navy Nurse Corps (1908). Both Army and Navy nurses served abroad during WWI in field hospitals, mobile units, evacuation camps, and convalescent hospitals as well as on troop transports.109112 However, women who served in the Army and Navy Nurse Corps were not eligible for retirement or veterans' benefits. During World War I, under the Naval Act of 1916, which authorized the Navy to enlist "citizens,"110113 the Navy Department enlisted approximately 13,000 women for service in the Navy and Marine Corps in clerical occupations.111114 These enlisted women were eligible for the same pay and benefits as their male counterparts. While women served in the Army Nurse Corps, the Army did not officially enlist any women in the regular service.112115

Before World War II, traditional attitudes towards women's roles in society and the military as a masculine organization were prevalent and thus there was little public interest in permanently integrating females into other occupations in the Armed Forces. In 1928, Major Everett S. Hughes, the chief Army planner for the development of the women's corps suggested that given shifting technology and rapid industrialization, women would inevitably play a role in future combat, and as such they should be "indoctrinated" into the Army's culture and processes. He also argued that separate structures for women and men would be inefficient, and that women should be afforded similar uniforms, ranks, and privileges.113 116 Senior officials put aside Hughes' recommendations and planning efforts were put aside by senior officials andby and they were not adopted.