Navy Virginia-Class Submarine Program and AUKUS Submarine (Pillar 1) Project: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from October 4, 2017 to November 28, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- U.S. Navy Submarines

- U.S. Attack Submarine Force Levels

- Force-Level Goal

- Force Level at End of FY2016

- Los Angeles- and Seawolf-Class Boats

- Virginia (SSN-774) Class Program

- General

- Past and Projected Annual Procurement Quantities

- Multiyear Procurement (MYP)

- Joint Production Arrangement

- Cost-Reduction Effort

- Schedule and Cost Performance on Deliveries

- Virginia Payload Module (VPM)

- Acoustic Superiority and Other Improvements

- FY2018 Funding Request

- Submarine Construction Industrial Base

- Projected SSN Force Levels

- Relative to 66-Boat Force Level Goal

- Projected Valley from FY2025 to FY2036

- SSN Deployments Delayed Due to Maintenance Backlogs

- Navy Testimony

- Press Reports

Issues for Congress- FY2018 Funding

- Impact of CR on Execution of FY2018 Funding

- Achieving a 66-Boat SSN Force

- Number of Additional Boats Needed in 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

- Time Needed to Achieve a 66-Boat Force

- Ability of Industrial Base to Achieve Higher Production Rates

- Cost to Achieve and Maintain 66-Boat SSN Force

- Mitigating Projected SSN Force-Level Valley

- Overview

- Extending a Few SSN-688 Service Lives to Age 36 or 37

- Refueling a Few SSN-688s

- Procuring Additional Virginia-Class Boats in Near Term

- Press Reports

- Navy Plans for Building VPM-Equipped Virginia-Class Boats

- Three Virginia-Class Boats Built with Defective Parts

- Reported Problem with Hull Coating

- Issues Raised in December 2016 DOT&E Report

- Legislative Activity for FY2018

- Congressional Action on FY2018 Funding Request

- FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/S. 1519)

- House

- Senate

- Conference Report

FY2018 DOD Appropriations Act (Division A of H.R. 3219)- House Committee Report

- House Floor Consideration

Tables

Summary

The Navy has been procuring Virginia (SSN-774) class nuclear-powered attack submarines since FY1998. The two Virginia-class boats requested for procurement in FY2018 are to be the 27th and 28th boats in the class. The 10 Virginia-class boats programmed for procurement in FY2014-FY2018 (two per year for five years) are being procured under a multiyear-procurement (MYP) contract.

The Navy estimates the combined procurement cost of the two Virginia-class boats requested for procurement in FY2018 at $5,532.7 million, or an average of $2,766.4 million each. The boats have received a total of $1,647.0 million in prior-year "regular" advance procurement (AP) funding and $580.4 million in prior-year Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) AP funding. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests the remaining $3,305.3 million needed to complete the boats' estimated combined procurement cost. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget also requests $1,920.6 million in AP funding for Virginia-class boats to be procured in future fiscal years, bringing the total FY2018 funding request for the program (excluding outfitting and post-deliverypostdelivery costs) to $5,225.9 million.

The Navy plans to build one of the two Virginia-class boats scheduled to be procured in FY2019, and all Virginia-class boats procured in FY2020 and subsequent years, with an additional mid-bodymidbody section, called the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), that contains four large-diameter, vertical launch tubes that the boats would use to store and fire additional Tomahawk cruise missiles or other payloads, such as large-diameter unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests $72.9 million in research and development funding for the Virginia Payload Module (VPM).

The Navy's previous force-level goal was to achieve and maintain a 308-ship fleet, including 48 SSNs. The Navy's new force-level goal, released in December 2015, is to achieve and maintain a 355-ship fleet, including 66 SSNs. The Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan was developed in association with the previous 308-ship force-level goal, and consequently does not include enough SSNs to achieve and maintain a force of 66 SSNs. CRS estimates that 19 SSNs would need to be added to the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve and maintain a 66-boat SSN force. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that 16 to 19 would need to be added to the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve and maintain a 66-boat SSN force. Taking into account the capacity of the submarine construction industrial base and the Navy's current plan to also build Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarines in coming years, CRS and CBO estimate that the earliest a 66-boat SSN force could be achieved might be the mid- to late 2030s.

From FY2025 to FY2036, the number of SSNs is projected to experience a dip or valley, reaching a minimum of 41 boats (i.e., 25 boats, or about 38%, less than the 66-boat force-level goal) in FY2029. This projected valley is a consequence of having procured a relatively small number of SSNs during the 1990s, in the early years of the post-Cold War era. Some observers are concerned that this projected valley in SSN force levels could lead to a period of heightened operational strain for the SSN force, and perhaps a period of weakened conventional deterrence against potential adversaries. The projected SSN valley was first identified by CRS in 1995 and has been discussed in CRS reports and testimony every year since then. The Navy has been exploring options for mitigating the projected valley. Procuring additional Virginia-class boats in the near term is one of those options. In that connection, the Navy has expressed interest in procuring an additional Virginia-class boat in FY2021. Congress also has the option of funding the procurement of one or more additional Virginia-class boats in FY2018-FY2020.

Introduction

This report provides background information and issues for Congress on the Virginia-class nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) program. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests $5,225.9 million in procurement and advance procurement (AP) funding for the program. Decisions that Congress makes on procurement of Virginia-class boats could substantially affect U.S. Navy capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

The Navy's Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine program, previously known as the Ohio Replacement or SSBN(X) program, is discussed in another CRS report.1

For an overview of the strategic and budgetary context in which the Virginia-class program and other Navy shipbuilding programs may be considered, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed].

Background

U.S. Navy Submarines2

The U.S. Navy operates three types of submarines—nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs),3 nuclear-powered cruise missile and special operations forces (SOF) submarines (SSGNs),4 and nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs). The SSNs are general-purpose submarines that can (when appropriately equipped and armed) perform a variety of peacetime and wartime missions, including the following:

- covert intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), much of it done for national-level (as opposed to purely Navy) purposes;

- covert insertion and recovery of SOF (on a smaller scale than possible with the SSGNs);

- covert strikes against land targets with the Tomahawk cruise missiles (again on a smaller scale than possible with the SSGNs);

- covert offensive and defensive mine warfare;

- anti-submarine warfare (ASW); and

- anti-surface ship warfare.

During the Cold War, ASW against Soviet submarines was the primary stated mission of U.S. SSNs, although covert ISR and covert SOF insertion/recovery operations were reportedly important on a day-to-day basis as well.5 In the post-Cold War era, although anti-submarine warfare remained a mission, the SSN force focused more on performing the other missions noted on the list above. In light of the recent shift in the strategic environment from the post-Cold War era to a new situation featuring renewed great power competition that some observers conclude has occurred, ASW against Russian and Chinese submarines may once again become a more prominent mission for U.S. Navy SSNs.6

U.S. Attack Submarine Force Levels

Force-Level Goal

The Navy's previous force-level goal was to achieve and maintain a 308-ship fleet, including 48 SSNs. The Navy's new force-level goal, released in December 2015, is to achieve and maintain a 355-ship fleet, including 66 SSNs.7 For a review of SSN force level goals since the Reagan Administration, see Appendix A.

Force Level at End of FY2016

The SSN force included more than 90 boats during most of the 1980s, when plans called for achieving a 600-ship Navy including 100 SSNs. The number of SSNs peaked at 98 boats at the end of FY1987 and has declined since then in a manner that has roughly paralleled the decline in the total size of the Navy over the same time period. The 52 SSNs in service at the end of FY2016 included the following:

- 36 Los Angeles (SSN-688) class boats;

- 3 Seawolf (SSN-21) class boats; and

- 13 Virginia (SSN-774) class boats.

Los Angeles- and Seawolf-Class Boats

A total of 62 Los Angeles-class submarines, commonly called 688s, were procured between FY1970 and FY1990 and entered service between 1976 and 1996. They are equipped with four 21-inch diameter torpedo tubes and can carry a total of 26 torpedoes or Tomahawk cruise missiles in their torpedo tubes and internal magazines. The final 31 boats in the class (SSN-719 and higher) were built with an additional 12 vertical launch system (VLS) tubes in their bows for carrying and launching another 12 Tomahawk cruise missiles. The final 23 boats in the class (SSN-751 and higher) incorporate further improvements and are referred to as Improved Los Angeles class boats or 688Is. As of the end of FY2016, 26 of the 62 boats in the class had been retired.

The Seawolf class was originally intended to include about 30 boats, but Seawolf-class procurement was stopped after three boats as a result of the end of the Cold War and associated changes in military requirements. The three Seawolf-class submarines are the Seawolf (SSN-21), the Connecticut (SSN-22), and the Jimmy Carter (SSN-23). SSN-21 and SSN-22 were procured in FY1989 and FY1991 and entered service in 1997 and 1998, respectively. SSN-23 was originally procured in FY1992. Its procurement was suspended in 1992 and then reinstated in FY1996. It entered service in 2005. Seawolf-class submarines are larger than Los Angeles-class boats or previous U.S. Navy SSNs.8 They are equipped with eight 30-inch-diameter torpedo tubes and can carry a total of 50 torpedoes or cruise missiles. SSN-23 was built to a lengthened configuration compared to the other two ships in the class.9

Virginia (SSN-774) Class Program

General

The Virginia-class attack submarine (see Figure 1) was designed to be less expensive and better optimized for post-Cold War submarine missions than the Seawolf-class design. The Virginia-class design is slightly larger than the Los Angeles-class design,10 but incorporates newer technologies. Virginia-class boats currently cost about $2.7 billion each to procure. The first Virginia-class boat entered service in October 2004.

Past and Projected Annual Procurement Quantities

Table 1 shows annual numbers of Virginia-class boats procured from FY1998 (the lead boat) through FY2017, and numbers scheduled for procurement under the FY2018-FY2022 Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP).

|

FY98 |

FY99 |

FY00 |

FY01 |

FY02 |

FY03 |

FY04 |

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

FY19 |

FY20 |

FY21 |

FY22 |

|

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on U.S. Navy data.

|

|

Source: U.S. Navy file photo accessed by CRS on January 11, 2011, at http://www.navy.mil/search/display.asp?story_id=55715. |

Multiyear Procurement (MYP)

The 10 Virginia-class boats shown in Table 1 for the period FY2014-FY2018 (referred to as the Block IV boats) are being procured under a multiyear procurement (MYP) contract11 that was approved by Congress as part of its action on the FY2013 budget, and awarded by the Navy on April 28, 2014. The eight Virginia-class boats procured in FY2009-FY2013 (the Block III boats) were procured under a previous MYP contract, and the five Virginia-class boats procured in FY2004-FY2008 (the Block II boats) were procured under a still-earlier MYP contract. The four boats procured in FY1998-FY2002 (the Block I boats) were procured under a block buy contract, which is an arrangement somewhat similar to an MYP contract.12 The boat procured in FY2003 fell between the FY1998-FY2002 block buy contract and the FY2004-FY2008 MYP arrangement, and was contracted for separately.

The Navy, as part of its FY2018 budget submission, may request approval for a new MYP contract for Virginia-class boats to be procured in FY2019-FY2023 (referred to as the Block V boats). Although this MYP contract would begin in FY2019—the budget for which Congress will consider in 2018—the Navy in the past has asked for authority for submarine MYP contracts one year prior to the first year of the requested contract period to provide the Navy more time to negotiate the details of the MYP contract.

Joint Production Arrangement

Overview

Virginia-class boats are built jointly by General Dynamics' Electric Boat Division (GD/EB) of Groton, CT, and Quonset Point, RI, and Huntington Ingalls Industries' Newport News Shipbuilding (HII/NNS), of Newport News, VA. GD/EB and HII/NNS are the only two shipyards in the country capable of building nuclear-powered ships. GD/EB builds submarines only, while HII/NNS also builds nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and is capable of building other types of surface ships.

The arrangement for jointly building Virginia-class boats was proposed to Congress by GD/EB, HII/NNS, and the Navy, and agreed to by Congress in 1997, at the outset of Virginia-class procurement.13 A primary aim of the arrangement is to minimize the cost of building Virginia-class boats at a relatively low annual rate in two shipyards (rather than entirely in a single shipyard) while preserving key submarine-construction skills at both shipyards.

Under the arrangement, GD/EB builds certain parts of each boat, HII/NNS builds certain other parts of each boat, and the yards have taken turns building the reactor compartments and performing final assembly of the boats. GD/EB has built the reactor compartments and performing final assembly on boats 1, 3, and so on, while HII/NNS has done so on boats 2, 4, and so on. The arrangement has resulted in a roughly 50-50 division of Virginia-class profits between the two yards and preserves both yards' ability to build submarine reactor compartments (a key capability for a submarine-construction yard) and perform submarine final-assembly work.14

Navy's Proposed Submarine Unified Build Strategy (SUBS)

The Navy, under a plan it calls the Submarine Unified Build Strategy (SUBS), is proposing to build Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines jointly at GD/EB and HII/NNS, with most of the work going to GD/EB. As part of this plan, the Navy is also proposing to adjust the division of work on the Virginia-class attack submarine program so that HII/NNS would receive a larger share of the work for that program than it has received in the past. Key elements of the Navy's proposed plan include the following:

- GD/EB is to be the prime contractor for designing and building Columbia-class boats;

- HII/NNS is to be a subcontractor for designing and building Columbia-class boats;

- GD/EB is to build certain parts of each Columbia-class boat—parts that are more or less analogous to the parts that GD/EB builds for each Virginia-class attack submarine;

- HII/NNS is to build certain other parts of each Columbia-class boat—parts that are more or less analogous to the parts that HII/NNS builds for each Virginia-class attack submarine;

- GD/EB is to perform the final assembly on all 12 Columbia-class boats;

- as a result of the three previous points, the Navy estimates that GD/EB would receive an estimated 77%-78% of the shipyard work building Columbia-class boats, and HII/NNS would receive 22%-23%;

- GD/EB is to continue as prime contractor for the Virginia-class program, but to help balance out projected submarine-construction workloads at GD/EB and HII/NNS, the division of work between the two yards for building Virginia-class boats is to be adjusted so that HII/NNS would perform the final assembly on a greater number of Virginia-class boats than it would have under a continuation of the current Virginia-class division of work (in which final assemblies are divided more or less evenly between the two shipyards); as a consequence, HII/NNS would receive a greater share of the total work in building Virginia-class boats than it would have under a continuation of the current division of work.15

The Navy described the plan in February 25, 2016, testimony before the Seapower and Projection Forces subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee. At that hearing, Navy officials testified that:

In 2014, the Navy led a comprehensive government-Industry assessment of shipbuilder construction capabilities and capacities at GDEB and HII-NNS to formulate the Submarine Unified Build Strategy (SUBS) for concurrent OR [Ohio replacement, i.e., Columbia-class] and Virginia class submarine production. This build strategy's guiding principles are: affordability, delivering OR on time and within budget, maintaining Virginia class performance with a continuous reduction in costs, and maintaining two shipbuilders capable of delivering nuclear-powered submarines. To execute this strategy, GDEB has been selected as the prime contractor for OR with the responsibilities to deliver the twelve OR [Ohio replacement] submarines [i.e., GD/EB will perform final assembly on all 12 boats in the program]. HII-NNS will design and construct major assemblies and OR modules leveraging their expertise with Virginia construction [i.e., HII/NNS will build parts of Ohio replacement boats that are similar to the parts it builds for Virginia-class boats]. Both shipbuilders will continue to deliver [i.e., perform final assembly of] Virginia class submarines throughout the period with GDEB continuing its prime contractor responsibility for the program. Given the priority of the OR Submarine Program, the delivery [i.e., final assembly] of Virginia class submarines will be adjusted with HII-NNS performing additional deliveries. Both shipbuilders have agreed to this build strategy.16

Cost-Reduction Effort

The Navy states that it achieved a goal of reducing the procurement cost of Virginia-class submarines so that two boats could be procured in FY2012 for a combined cost of $4.0 billion in constant FY2005 dollars—a goal referred to as "2 for 4 in 12." Achieving this goal involved removing about $400 million (in constant FY2005 dollars) from the cost of each submarine. (The Navy calculated that the unit target cost of $2.0 billion in constant FY2005 dollars for each submarine translated into about $2.6 billion for a boat procured in FY2012.)17

Schedule and Cost Performance on Deliveries

As noted in CRS testimony in 2014,18 the Virginia (SSN-774) class attack program has been cited frequently in recent years as an example of a successful acquisition program. The program received a David Packard Excellence in Acquisition Award from DOD in 2008. Although the program experienced cost growth in its early years that was due in part to annual procurement rates that were lower than initially envisaged and challenges in restarting submarine production at Newport News Shipbuilding,19 the lead ship in the program was delivered within four months of the target date that had been established about a decade earlier, and ships in recent years have been delivered largely on cost and ahead of schedule. As a recent exception to that record, a March 13, 2017, press report states the following:

The luster is off a bit for the Virginia-class submarine building program, long considered a model US Navy construction effort that routinely brings down the building time and cost for each successive sub. One submarine has just missed its contract delivery date — pushed back even more when sea trials were halted to return to port — and shipbuilders are working harder to keep construction on schedule....

Problems seem to stem from two primary factors: the move in 2011 to double the submarine construction rate from one to two per year has strained shipyards and the industrial base that supplies parts for the subs; and the Navy has successively reduced contractual building times as shipbuilders grew more experienced with building the submarines, cutting back on earlier, highly-trumpeted opportunities to beat deadlines.

The situation seemingly came to a head March 2 shortly after the submarine Washington began its initial sea trials off the Virginia coast. The submarine, fitting out at Huntington Ingalls Newport News Shipbuilding, has been falling behind schedule for some time, missing a targeted summer 2016 delivery date and a scheduled Jan. 7 commissioning ceremony. More delays ensued in January when, according to the Navy, a problem was found with the hatch seating surface in the large lockout trunk access hatch, requiring a notice to Congress that the ship would miss its Feb. 28 contract delivery date and a rescheduled March 25 commissioning date.

It's not the first time a Virginia-class submarine has missed a contract delivery date. The first two subs were late, and in late 2007 the North Carolina, the third Virginia, was delivered by Newport News seven weeks late because of welding issues. But since then, every submarine delivered by Newport News and Virginia class prime contractor General Dynamics Electric Boat has been delivered by the contract date or more often, earlier, causing something of a competition between the two yards.

Rear Adm. Michael Jabaley, program executive officer for submarines at Naval Sea Systems Command, was aboard the Washington for the sea trials but would not specify the exact problem that caused officials to take the highly unusual move of cutting short the sea trials.

Initial sea trials, he said March 9, are "a focused, two-and-a-half-day period where you certify the full capability of the ship from a propulsion, from a safety and recovery standpoint." If an issue comes up that impacts the ability to continue trials, he said, "you're coming back in. And that's what we did.

"We're working through this particular issue, and the delivery and commissioning date for the Washington is under review as a result," he added. "But my estimation is that we'll come through it relatively quickly."

But even with the sub's late delivery, Jabaley remains hopeful that by the end of the completion cycle — including post-delivery tests and a nearly six-month-long post shakedown availability overhaul – the planned date by which the completed, ready-for-operations submarine is turned over to commanders will still be met.

"Washington will deliver very close to schedule," Jabaley said, "and at delivery to the type commander she will be as early or earlier than almost any other submarine we've delivered in terms of getting her to the type commander as an operational asset."

So far, the Navy said, costs are not rising.

"The last nine Virginia submarines, (New Hampshire SSN 778 through Illinois SSN 786) have all been delivered under target cost and within Navy budget," Jabaley said. "Current projections are that all remaining Block III submarines (Washington SSN 787 through Delaware SSN 791) will also deliver under target cost and within Navy budget."...

The 2011 ramp-up from one to two submarines ordered each year strained the shipbuilders and the submarine industrial base. Electric Boat and Newport News, who share equally in building each sub, had to hire more workers, injecting a level of inexperience into their work forces with a consequent rise in the amount of work needing to be redone. Some parts suppliers have struggled to keep up with increased demand, and late deliveries and quality problems have become more frequent.

"Both shipbuilders hired additional people to account for the increase to two submarines per year," Jabaley said. "As a result, obviously when you bring in an influx of new people your level of experience goes down.

"There is always a certain amount of rework in any manufacturing endeavor, and submarine construction is no different," he said. "It is something we monitor closely. We knew there would be what we call the green labor effect as we went up to two per year. But we have in general satisfactorily come through that."

The building schedule has also been significantly reduced since the first four Block I Virginias were contracted for an 84-month building period, reduced to 74 months for the six Block IIs. The eight Block III subs — those currently under construction — are set for a 66-month building times, and Block IVs will be reduced further to 62 and then 60 months.

The first three Block IIIs were delivered by the contract date, Jabaley noted, but the streak was broken with Washington. Sources noted concerns that Colorado, the next submarine to be delivered from Electric Boat, is challenged to meet her Aug. 31 delivery date, but Jabaley expressed confidence the program would work through its problems, declaring that, "at this point, Colorado is on schedule and we're working very hard for her and subsequent ships — Indiana's the one after her — to meet their contract delivery dates."

The late delivery of the Washington is "not indicative of a systemic problem," Jabaley said. "What this is is a recognition that we have challenged the shipbuilders.

"The Virginia class continues to be a high-performing program with each successive submarine delivering with improved quality, less deferred work, and reduced acquisition cost."20

Virginia Payload Module (VPM)

The Navy plans to build one of the two Virginia-class boats scheduled to be procured in FY2019, and all Virginia-class boats procured in FY2020 and subsequent years, with an additional mid-bodymidbody section, called the Virginia Payload Module (VPM). The VPM, with a reported length of 83 feet, 9.75 inches,21 contains four large-diameter, vertical launch tubes that would be used to store and fire additional Tomahawk cruise missiles or other payloads, such as large-diameter unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).22

The four additional launch tubes in the VPM could carry a total of 28 additional Tomahawk cruise missiles (7 per tube),23 which would increase the total number of torpedo-sized weapons (such as Tomahawks) carried by the Virginia class design from about 37 to about 65—an increase of about 76%.24

In constant FY2010 dollars, the Navy in January 2015 estimated the nonrecurring engineering (i.e., design) cost of the VPM as $725 million, the production cost for the first VPM-equipped boat as $409 million, and the production cost for subsequent VPM-equipped boats as $305 million. Using DOD's deflator for procurement costs other than pay fuel and medical, the figure of $305 million in constant FY2010 dollars equated to about $340 million in FY2017 dollars. Given the current Virginia-class unit procurement cost of about $2.7 billion, an additional cost of $340 million would represent an increase of roughly 13% in unit procurement cost.

A September 23, 2016, press report stated that the Navy, in a July 29, 2016, report to Congress on the VPM project, now estimates that VPM costs will come in below nonbinding cost targets that were established by the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) in December 2013:

The non-recurring engineering costs [of the VPM project], in fiscal year 2010 dollars, are forecast to be $725 million, below the $800 million threshold and $750 million objective. The VPM cost for the lead boat to receive the new tubes is estimated to be $409 million, below the $475 million threshold and $425 objective, according to the report. And the VPM price tag for follow-on submarines is slated to be $305 million, below the $350 million threshold and $325 million objective cost, the report states.25

Building Virginia-class boats with the VPM would compensate for a sharp loss in submarine force weapon-carrying capacity that will occur with the retirement in FY2026-FY2028 of the Navy's four Ohio-class cruise missile/special operations forces support submarines (SSGNs).26 Each SSGN is equipped with 24 large-diameter vertical launch tubes, of which 22 can be used to carry up to 7 Tomahawks each, for a maximum of 154 vertically launched Tomahawks per boat, or 616 vertically launched Tomahawks for the four boats. Twenty-two Virginia-class boats built with VPMs could carry 616 Tomahawks in their VPMs.

A November 18, 2015, press report states the following:

The Virginia-class submarine program is finalizing the Virginia Payload Module design and will start prototyping soon to reduce risk and cost as much as possible ahead of the 2019 construction start, according to a Navy report to Congress.

According to the "Virginia Class Submarine Cost Containment Strategy for Block V Virginia Payload Module Design" report, dated Aug. 31 but not received by the Senate until mid-October, the Navy says late Fiscal Year 2015 and early FY 2016 is a "critical" time period for the program....

The Naval Sea Systems Command's (NAVSEA) engineering directorate will update cost estimates soon based on the final concept design, but so far the program has been successful in sticking to its cost goals. The program had a threshold requirement of $994 million and an objective requirement of $931 million in non-recurring engineering costs, and as of January 2015 the program estimated it would end up spending $936 million. The first VPM module is required to cost $633 million with an objective cost of $567 million, and the most recent estimate puts the lead ship VPM at $563 million. Follow-on VPMs would be required to cost $567 million each with an objective cost of $527 million, and the January estimate puts them at an even lower $508 million.27

The joint explanatory statement for the FY2014 Department of Defense (DOD) Appropriations Act (Division C of H.R. 3547/P.L. 113-76 of January 17, 2014) required the Navy to submit biannual reports to the congressional defense committees describing the actions the Navy is taking to minimize costs for the VPM.28 The first such report, dated July 2014, is reprinted in Appendix C.29

Acoustic Superiority and Other Improvements

In addition to the VPM, the Navy is introducing other improvements to the Virginia-class design that are to help maintain the design's acoustic superiority over Russian and Chinese submarines. A November 18, 2017, press report states:

The Navy is now launching the most technologically advanced attack submarine it has ever developed by christening the USS South Dakota—a Block III Virginia-Class attack submarine engineered with a number of never-before-seen undersea technical innovations.

While service officials say many of the details of this new "acoustic superiority" Navy research and development effort are, naturally, not available for public discussion, the USS South Dakota has been a "technology demonstrator to prove out advanced technologies," Naval Sea Systems Command Spokeswoman Colleen O'Rourke told Scout Warrior.

Many of these innovations, which have been underway and tested as prototypes for many years, are now operational as the USS South Dakota enters service; service technology developers have, in a general way, said the advances in undersea technologies built, integrated, tested and now operational on the South Dakota include quieting technologies for the engine room to make the submarine harder to detect, a new large vertical array and additional "quieting" coating materials for the hull, Navy officials explained.

The USS South Dakota was christened by the Navy Oct. 14 at a General Dynamics Electric Boat facility in Groton, Ct.

"As the 7th ship of Block III, the PCU South Dakota (SSN 790) will be the most advanced VIRGINIA class submarine on patrol," O'Rourke said.

In recent years, the service has been making progress developing new acoustics, sensors and quieting technologies to ensure the U.S. retains its technological edge in the undersea domain—as countries like China and Russia continue rapid military modernization and construction of new submarines.

The impetus for the Navy's "acoustic superiority," is specifically grounded in the emerging reality that the U.S. undersea margin of technological superiority is rapidly diminishing in light of Russian and Chinse advances.

Described as a technology insertion, the improvements will eventually be integrated on board both Virginia-Class submarines and the now-in-development next-generation nuclear-armed boats called the Columbia-Class.

Some of these concepts, described as a fourth generation of undersea technology, are based upon a "domain" perspective as opposed to a platform approach—looking at and assessing advancements in the electro-magnetic and acoustic underwater technologies, Navy developers explained.

"Lessons learned from South Dakota will be incorporated into Block V and later Virginia Class submarines, increasing our undersea domain advantage and ensuring our dominance through the mid-century and beyond," O'Rourke added.30

A November 2, 2017, press report states:

The Navy has developed a Tactical Submarine Evolution Plan that looks at rapidly inserting capability upgrades into the Virginia-class attack submarine mid-contract and considers long-term undersea warfare priorities such as converting the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) production line into a guided-missile submarine (SSGN) line in the late 2030s.

The Navy's Undersea Warfare Directorate (OPNAV N97) started the plan under previous director Vice Adm. Bill Merz, who now serves as the deputy chief of naval operations for warfare systems (OPNAV N9), and has been continued under current acting director Brian Howes.

Howes, speaking Thursday [November 2] at the Naval Submarine League's annual symposium, said the next iteration of the Virginia-class submarine program, Block V, begins in Fiscal Year 2019, but currently if a new capability were developed after the design is complete, it would have to wait to be fielded in the next Block VI in FY 2023.

"We need to have the opportunity to have mid-block insertions into our platforms," he said.

Much like the Submarine Warfare Federated Tactical Systems that inserts combat upgrades into submarines every other year, Howes said the Tactical Submarine Evolution Plan (TSEP) would create "a ready menu of mature and maturing technology that we will insert when ready."

Though headed by OPNAV N97, the Program Executive Office for Submarines and the Virginia class program office are involved and wholeheartedly onboard.

"There's a continuous conveyor belt running, and developers who have an idea get on that conveyor belt, and if they can develop it and achieve the requisite reliability and producibility by the time that conveyor belt comes around for production then they can get into the next version … that's going to be fielded. If they miss that one, then the conveyor belt goes back around again and they get another shot at it in two years," PEO [Program Executive Officer] Subs Rear Adm. Michael Jabaley said at the conference of SWFTS and the Acoustics Rapid Commercial-off-the-shelf Insertion (ARCI) program that does the same thing on the computer processor side.

"So we want to try to implement that into shipbuilding. The time sequence is different of course—we're somewhat constrained by five-year multiyear procurement contracts, and we have previously tried to hold to a tech baseline letter at the beginning of the block that says the most efficient way to build 10 ships, all per this plan. One of the things that the TSEP looks at is, under the [chief of naval operations]'s theme of getting faster, waiting five years to insert the next technological development may not be the best thing for us to do. So we're willing to take risk, we're willing to look at breakthrough technologies that come, and if it makes sense to insert them mid-block then we're willing."

This concept somewhat blurs the lines of future Blocks VI and VII and the eventual move to the SSN(X) attack sub program. The Virginia class has been upgraded in each block to improve manufacturing, reduce lifecycle costs, and add a mid-body Virginia Payload Module with additional missile tubes. Though two more iterations of upgrades are planned, the submarine community is finding they're running out of space to add more capability.

"We are running out of design margin in this great platform, and there are some fleet needs which this platform cannot do. So as a result, under Adm. Merz's leadership, we've started the discussion of how we're going to leverage our block improvement conveyor belt to wring out as much as we can for future blocks of Virginia, while setting us up for success after Virginia," Howes said. TSEP would identify "capabilities that we are going to demand our shipbuilders inject into this platform, and if it can't be injected into this platform we're going to design it into [SSN(X)]."

Jabaley said the Virginia program had already had its acquisition program baseline extended from 30 boats to the current 48, which the program is scheduled to reach in FY 2033—but will likely hit even sooner, as the Navy looks at speeding up Virginia-class submarine construction.

"Then we'll make the decision, do we extend the APB again or will it be time to move on to a future submarine design?" Jabaley said. Though old assumptions point to moving to SSN(X) in FY 2034, as TSEP inserts more capability upgrades into the subs at a faster pace, "if technology, threat, environment, budget all conspire to say it makes more sense to start it earlier, start it later, then that's what we'll do."

Howes told USNI News that "there is a need for a dedicated funding line to support this conveyor belt, and we are in discussions inside the Navy and with [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] as to what that would look like. Ideally, first we'd get those resources from within, through cost-savings. One way or another we're going to start this up—the design effort, the technology development, it gets faster with resources; there is a need for resources and we are having those discussions today as part of our [FY 2019 budget] deliberations."31

A July 9, 2016, press report states:

The United States Navy is moving swiftly to make sure that its submarines are not eclipsed by new threats such as Russia's new Project 885 Yasen-class attack boats. While the U.S. Navy has talked about its efforts to maintain its technological superiority over potential foes, the service's two top undersea warfare officers detailed their Acoustic Superiority Program at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies on July 8.

"This is our response to the continued improvement in our peer competitors' submarine quality," Rear Adm. Michael Jabaley, the Navy's program executive officer for submarines, said. "The Russians with the production of the Severodvinsk SSGN took a significant step forward in their acoustic ability. We want to maintain pace ahead of that. We never want to reach acoustic parity, we always want to be better than anything any other country is putting out there in the submarine domain."

The future USS South Dakota (SSN-790) will be the first acoustic superiority test submarine when she is delivered in late 2017. During her one-year post-shakedown availability (PSA) in 2018, South Dakota will receive some fairly significant modifications from the baseline Virginia-class submarine that are expected to be tested at sea starting in 2019 and running through 2020.

The modifications include new acoustical hull coatings, a series of machinery improvements inside the hull and the addition of two new large vertical sonar arrays—one on each side. The new sonar arrays "provide a significant advantage in the ability to detect other submarines before you yourself are in a position to be detected," Jabaley said. Meanwhile, the machinery improvements also promise some "significant return on investment."

Additionally, South Dakota will receive a new enhanced propulsor design, which is being added during construction. However, if the new propulsor design proves to be less than successful, the Navy plans to replace it during the boat's post-shakedown availability. "South Dakota will have an improved enhanced hybrid propulsor that we have developed with DARPA," Jabaley said. "It promises to present a significant acoustic advantage."

If the modifications trialed on South Dakota prove to be successful, then the technologies will be adopted for use on future Virginia-class boats as well as the future Ohio Replacement Program (ORP) ballistic missile submarines. "The lessons we learn, we will learn from her [South Dakota], will then drive what we install on future ships including Ohio Replacement and what we back-fit on existing Virginias," Jabaley said.32

A March 28, 2016, press report states:

The submarine community is focused on maintaining access and boosting acoustic superiority after operating in relatively permissive environments for several years, two Navy officials told USNI News.

Director of Undersea Warfare Rear Adm. Charles Richard told USNI News in a March 22 interview that the submarine community knows how to operate in a stealthy mode, but "we're not taking our stealth for granted and we're not taking this competitive advantage we have for granted."

To that end, he said, the Navy is building an upcoming Virginia-class attack submarine, the future USS South Dakota (SSN-790), with acoustic superiority features for the fleet to test out and ultimately include in both attack and ballistic missile submarines in the future.

Richard said the under-construction South Dakota will feature a large vertical array, a special coating and machinery quieting improvements inside the boat. The boat is on track to deliver early despite the changes, he said. Once South Dakota joins the fleet—in 2018, according to the boat's commissioning committee—lessons learned from the acoustic superiority features will help inform enhancements built into future Virginia class boats and the Ohio Replacement Program boomers, as well as the legacy Ohio-class ballistic missile subs and some Virginia-class boats.

"Stealth is the cover charge, stealth is the price of admission, and while we have great access now we don't take that for granted either," Richard said.

"Making the right investments to maintain acoustic superiority over a potential adversary" is of high importance to the Navy today, and the South Dakota project represents "a clear national investment in acoustic superiority."

Program Executive Officer for Submarines Rear Adm. Michael Jabaley told USNI News in a March 3 interview that acoustic superiority items, some of which will be built into the ship and some of which will be added during the ship's post shakedown availability, "will kind of become the standard for what we do in various forms between Ohio Replacement, future Virginias and even backfit some on the Ohios and some of the delivered Virginias to make sure that submarine force is pacing the threat of these new highly capable submarines that are being delivered" from other navies like Russia and China.

Jabaley added that as the Navy looks at its next class of attack submarines, the SSN(X), stealth will be a key factor in the design and could lead to the Navy selecting an electric drive or other advanced propulsion system to eliminate as much noise as possible.33

FY2018 Funding Request

The Navy estimates the combined procurement cost of the two Virginia-class boats requested for procurement in FY2018 at $5,532.7 million, or an average of $2,766.4 million each. The boats have received a total of $1,647.0 million in prior-year "regular" advance procurement (AP) funding and $580.4 million in prior-year Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) AP funding. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget requests the remaining $3,305.3 million needed to complete the boats' estimated combined procurement cost. The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget also requests $1,920.6 million in AP funding for Virginia-class boats to be procured in future fiscal years, bringing the total FY2018 funding request for the program (excluding outfitting and post-deliverypostdelivery costs) to $5,225.9 million.

The Navy's proposed FY2018 budget also requests $72.9 million in research and development funding for the Virginia Payload Module (VPM). The funding is contained in Program Element (PE) 0604580N, entitled Virginia Payload Module (VPM), which is line 134 in the Navy's FY2018 research and development account.

Submarine Construction Industrial Base

In addition to GD/EB and HII/NNS, the submarine construction industrial base includes hundreds of supplier firms, as well as laboratories and research facilities, in numerous states. Much of the total material procured from supplier firms for the construction of submarines comes from single or sole source suppliers. For nuclear-propulsion component suppliers, an additional source of stabilizing work is the Navy's nuclear-powered aircraft carrier construction program.3034 In terms of work provided to these firms, a carrier nuclear propulsion plant is roughly equivalent to five submarine propulsion plants. Much of the design and engineering portion of the submarine construction industrial base is resident at GD/EB; smaller portions are resident at HII/NNS and some of the component makers.

Projected SSN Force Levels

Relative to 66-Boat Force Level Goal

Table 2 shows the Navy's projection of the number of SSNs over time if the Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan were fully implemented. The FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan was developed in association with the previous 308-ship force-level goal (which included a 48-boat force-level goal for SSNs). Consequently, as can be seen in the table, the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan does not include enough SSNs to achieve and maintain a force of 66 SSNs.

Table 2. Projected SSN Force Levels

As shown in Navy's FY2017 30-Year (FY2017-FY2046) Shipbuilding Plan

|

Fiscal year |

Annual procurement quantity |

Projected number of SSNs |

Force level relative to |

Force level relative to previous 48-boat goal |

||

|

Number of ships |

Percent |

Number of ships |

Percent |

|||

|

17 |

2 |

52 |

-14 |

-21% |

||

|

18 |

2 |

53 |

-13 |

-20% |

||

|

19 |

2 |

52 |

-14 |

-21% |

||

|

20 |

2 |

52 |

-14 |

-21% |

||

|

21 |

1 |

51 |

-15 |

-23% |

||

|

22 |

2 |

48 |

-18 |

-27% |

||

|

23 |

2 |

49 |

-17 |

-26% |

||

|

24 |

1 |

48 |

-18 |

-27% |

||

|

25 |

2 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

26 |

1 |

45 |

-21 |

-32% |

3 |

-6% |

|

27 |

1 |

44 |

-22 |

-33% |

4 |

-8% |

|

28 |

1 |

42 |

-24 |

-36% |

6 |

-13% |

|

29 |

1 |

41 |

-25 |

-38% |

7 |

-15% |

|

30 |

1 |

42 |

-24 |

-36% |

6 |

-13% |

|

31 |

1 |

43 |

-23 |

-35% |

5 |

-10% |

|

32 |

1 |

43 |

-23 |

-35% |

5 |

-10% |

|

33 |

1 |

44 |

-22 |

-33% |

4 |

-8% |

|

34 |

1 |

45 |

-21 |

-32% |

3 |

-6% |

|

35 |

1 |

46 |

-20 |

-30% |

2 |

-4% |

|

36 |

2 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

37 |

2 |

48 |

-18 |

-27% |

||

|

38 |

2 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

39 |

2 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

40 |

1 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

41 |

2 |

47 |

-19 |

-29% |

1 |

-2% |

|

42 |

1 |

49 |

-17 |

-26% |

||

|

43 |

2 |

49 |

-17 |

-26% |

||

|

44 |

1 |

50 |

-16 |

-24% |

||

|

45 |

2 |

50 |

-16 |

-24% |

||

|

46 |

1 |

51 |

-15 |

-23% |

||

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy's FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan. Percent figures rounded to nearest percent.

Projected Valley from FY2025 to FY2036

As also shown in Table 2, the number of SSNs is projected to experience a dip or valley in FY2025-FY2036, reaching a minimum of 41 boats (i.e., 25 boats, or about 38%, less than the 66-boat force-level goal) in FY2029. This projected valley is a consequence of having procured a relatively small number of SSNs during the 1990s, in the early years of the post-Cold War era. Some observers are concerned that this projected valley in SSN force levels could lead to a period of heightened operational strain for the SSN force, and perhaps also a period of weakened conventional deterrence against potential adversaries. The projected SSN valley was first identified by CRS in 1995 and has been discussed in CRS reports and testimony every year since then.

SSN Deployments Delayed Due to Maintenance Backlogs

In recent years, a number of the Navy's SSNs have had their deployments delayed due to maintenance backlogs at the Navy's four government-operated shipyards, which are the primary facilities for conducting depot-level maintenance work on Navy SSNs. Delays in deploying SSNs can put added operational pressure on other SSNs that are available for deployment.

Navy Testimony

On March 29, 2017, the Navy testified that

The high operational tempo in the post 9/11 era combined with reduced readiness funding and consistent uncertainty about when these reduced budgets will be approved have created a large maintenance mismatch between the capacity in our public shipyards and the required work. This has resulted in a large maintenance backlog which has grown from 4.7 million man-days to 5.3 million man-days between 2011 and 2017. Today, despite hiring 16,500 new workers since 2012, Naval Shipyards are more than 2,000 people short of the capacity required to execute the projected workload, stabilize the growth in the maintenance backlog and eventually eliminate that backlog. This shortfall, coupled with reduced workforce experience levels (about 50 percent of the workforce has less than five years of experience) and shipyard productivity issues have impacted Fleet readiness through the late delivery of ships and submarines. The capacity limitations and the overall priority of work toward our Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBNs) and Aircraft Carriers (CVN) have resulted in our Attack Submarines (SSNs) absorbing much of the burden, causing several submarine availabilities that were originally scheduled to last between 22 and 25 months to require 45 months or more to complete. These delays not only remove the submarines from the Fleet for extended periods of time, but also have an impact on the crews' training and morale. This situation reached a boiling point this past summer when in order to balance the workload, the Navy decided to defer a scheduled maintenance availability on the USS BOISE (SSN 764) that will effectively take her off line until 2020 or later. Although the Navy has not made a final decision on BOISE, she will likely be contracted to the private sector at additional cost to the Navy in 2019.35

Press Reports

A November 6, 2017, press report states:

The good news? The US submarine fleet is meeting day-to-day demands around the world, without having to do the extra-long deployments that have ground down surface ships and sailors. The bad news? A massive maintenance backlog that could idle 15 submarines for months—costing an estimated seven to 15 years of time at sea—means fewer subs would be ready to reinforce forward-deployed forces in a crisis.

"If you have a submarine that's tied up in the shipyard, then obviously they're not operating," Vice Adm. Joseph Tofalo told me. "It's probably most manifest in our ability to surge in time of crisis. We meet our combatant commander (COCOM) demand on a day to day basis, but the impact would be, if there's a crisis, then your surge tank is low."

Tofalo and other officers at last week's Naval Submarine League conference made clear they're laboring mightily to make up for the shortfall. The Navy wants to build more new Virginia-class submarines, and faster, while extending the service lives of the Virginia and Los Angeles boats it already has. It is adjusting work schedules and outsourcing "about a million man-hours of [maintenance] work…over five years" from maxed-out government-owned yards to private shipyards Newport News and Electric Boat, Tofalo said. (Many in Congress would like it to outsource more). As Commander, Submarine Forces, Tofalo has also streamlined the training schedule to concentrate on the most challenging missions, especially the kind of high-intensity warfare against an advanced adversary that a crisis might require....

... submarine deployments have averaged 182 days over the last three years. That almost perfectly tracks the official norm of six months overseas and 12 months doing maintenance and training at home. In fact, deployment timelines have trended downward lately.

There are exceptions: The USS Jacksonville recently did eight months on its final tour before retiring....

While there have been few delays due to over-long deployments, however, there have been delays due to over-long maintenance periods. Over the last eight years, Tofalo told the conference, six submarines "have taken or are projected to take 50 percent to 100 percent longer to complete their overhauls than expected." The current backlog affects 15 submarines and could cost the Navy almost 15 years of time at sea, although there's a mitigation plan in place to halve that.

What's going wrong? "This is a long term issue," Tofalo told me. "It started back in the nineties." The Navy cut back from eight public shipyards to four. Then it increased the shipyard workload by converting four Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) to Tomahawk cruise missile carriers (SSGNs). Then it increased the workload again by deciding to overhaul the Ohios to keep them in service longer, which allowed more time to develop the $128 billion replacement program, the Columbia class. Older, more efficient workers retired en masse, forcing the yards to hire and train a new generation.

Meanwhile budget caps, sequestration cuts, continuing resolutions, government shutdowns, and hiring freezes made it harder to get work done. "It's this perfect storm of a lot of stuff over two decades, and then you throw on top of it sequestration, the Budget Control Act and the unpredictability of funding," Tofalo said.

"We've had a backlog of maintenance that started with sequestration," echoed Adm. James Caldwell, head of Naval Reactors (NR). "We've got a very young and inexperienced work force in the yards… roughly 50 percent is under five years of experience. We've also had emerging work" (i.e. unplanned extra maintenance).

So, Caldwell continued, "we sharpened our pencils and looked at schedules and made those work better for us, and actually we've substantially reduced the months of backlog" from 177 (14.75 years) to 81 (6.75 years). "We are hiring in the shipyards (with) very aggressive training plan," he said. "We've had to change our paradigm….We don't have years and years to develop a mechanic."...

The Navy is also looking at extending the lives of at least some of its aging Los Angeles attack subs. As each boat approaches its planned retirement date, said Rear Adm. Michael Jabaley, Program Executive Officer for Submarines, it is subjected to an in-depth study to see if it can do one more deployment.36

An October 31, 2017, press report states:

A massive maintenance backlog has idled 15 nuclear-powered attack submarines for a total of 177 months, and the Navy's plan to mitigate the problem is jeopardized by budget gridlock, two House Armed Services Committee staffers told Breaking Defense.

That is almost 15 submarine-years, the equivalent of taking a boat from the 2018 budget and not adding it back until 2033.

While only Congress can pass a budget and lift caps on spending, the staffers said, part of the solution is in the Navy's hands: outsource more work to private-sector shipyards, something the Navy does not like to do.

As the submariner community prepares to gather in Washington, D.C. for the annual Naval Submarine League symposium, a lot of subs are in rough shape. The most famous case is the USS Boise, which was scheduled to start an overhaul at the government-run Norfolk Naval Shipyard in September 2016 and is still waiting. The government finally gave up and awarded a $385.6 million contract for the work to privately run Newport News Shipbuilding – just across the James River—this month. All told, the Navy says the Boise will be out of service for 31 months longer than originally planned.

But Boise isn't the only one. Figures provided to us by HASC show 14 other submarines are affected, with projected delays ranging from two months (USS Columbia, Montpellier, and Texas) to 21 (Greeneville). And the Navy can't simply send them back to sea, since without the maintenance work, the submarines can't be certified as safe to dive....

The Navy does have a plan to mitigate the problem, but it can't get rid of it. If the Navy were able to move money, reshuffle schedules, extend certifications, and take other steps, then it would get many of the suns into maintenance sooner and slash time lost across the fleet to 81 months.

That's still almost seven years that submarines could be at sea but aren't. If you put all this on a single notional sub, it would lose 23 percent of its normal service life....

... the mitigation plan itself is in jeopardy. Three of the overhauls are scheduled to start in fiscal year 2018, which began a month ago, without a federal budget. Instead, Congress has passed a stopgap Continuing Resolution, which puts government spending on autopilot, with little leeway to make the kind of adjustments the mitigation plan requires....

Past BCA [Budget Control Act]-imposed cuts and Continuing Resolutions bear part of the blame for the Navy's problems today, the HASC staffers said, as well as the mass retirements of Reagan-era craft. Today, the Navy has fewer ships to meet an unchanged workload, meaning each ship must deploy longer. As a result ships not only miss their originally planned overhaul dates, messing up the maintenance schedule, but they also come in with more wear, tear, and breakdowns than projected, causing their overhauls to take longer. That means they can't deploy on time, which means the ships they would have relieved must stay on station longer, which means those ships will have more maintenance issues, ad infinitum....

The attack submarine force has an additional complication. It is nuclear powered. Key maintenance can only be done in a handful of specifically equipped yards by specially trained workers. The Navy prefers to do this in-house, but its nuclear-capable public yards have limited capacity, and they prioritize ballistic missile submarines – which make up the bulk of the nation's nuclear deterrent—and aircraft carriers over the much more numerous attack subs. If maintenance schedules slip on a missile sub or carrier, attack subs get bumped down the list.

That's why the Navy finally outsourced the Boise's repairs to Huntington-Ingalls Industries' Newport News shipyard in Virginia. That's one of two private yards in the country that can do nuclear work—the other is General Dynamics' Electric Boat in New England. Unlike the public yards, the HASC staffers said, these private yards still have some spare capacity and will have it for "the next five years." After that, work on the next ballistic missile submarine, the Columbia class, will pick up and the private yards will be at capacity too.37

A June 15, 2017, press report states:

The Navy has faced massive backlogs of submarine and aircraft carrier maintenance work at its four public shipyards in recent years, at times pushing nearly ten percent of its workload into the next year.

But if 2017 was the year that bow wave of deferred maintenance caught the attention of lawmakers, it was also the year the Navy made great strides in addressing the problem – despite having a ten percent higher than average workload this year, the yards will end the year with about a quarter of the maintenance backlog they began the year with, the Naval Sea Systems Command commander Vice Adm. Tom Moore told USNI News.

2017 had all the markings of a tough year as it approached. The Navy had scheduled 5.4 million man-days of work across the four naval shipyards, above the average workload from 2013 to 2016 of 4.9 million man-days. As much as 400,000 man-days of work on the 2016 schedule were being deferred to 2017, which was pretty consistent with the backlog being carried over from year to year recently. The four yards were still short of their manpower goal of 36,100 workers. And several "problem children" attack submarines were still on the books, in some cases years after they were first brought into a shipyard for the start of a maintenance availability, due to a lack of available workers to complete those jobs.

Despite all those challenges the shipyards had to face this year, they will leave 2017 in better shape than they came in, Moore assured. Less than 100,000 man-days of work will be pushed into 2018. The workforce stands above 34,000 already and will continue to grow closer to the 36,100 target. And four of the "problem children" will complete their availabilities and return to the fleet this year, ending the strain they put on the yards by continually upping the backlog size and lowering on-time completion rates.38

A June 1, 2017, press report states:

Last week's 2018 budget request lays the groundwork to get attack submarine USS Boise (SSN-764) into an overdue maintenance availability in 2019, with a private shipyard taking over the maintenance effort to get the sub out of its two-year holding pattern.

Boise has been used over and over again during this past year as the example of the Navy's public shipyard backlog. The four yards are struggling to get ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs) out on time, with the aircraft carriers being the second priority—meaning the attack submarine fleet is facing the brunt of the backlog. In the case of Boise, the Navy didn't bother to keep the sub at the repair yard, allowing the sub's dive certification to expire as it sat pier-side at Naval Station Norfolk. On the other hand, in the case of USS Albany (SSN-753), the other frequently used example, the attack sub entered the yard and spent 48 months there instead of a planned 24, with the workforce distracted by SSBN and CVN work elsewhere in the yard.

Now, according to Navy budget documents, "to help reduce [Naval Shipyard] workload and better align workload to capacity, FY 2018 funds planning for private sector submarine maintenance to reduce the impact to follow-on maintenance work. These efforts minimize the more expensive future execution of deferred current work, maximize utilization of private and public maintenance capacity, and support [the Navy's Optimized Fleet Response Plan that outlines maintenance and deployment schedules]. Deferred maintenance in FY 2016 included the cancellation of the USS BOISE maintenance availability due to insufficient capacity at the [Naval Shipyards]."

Navy spokesman Lt. Seth Clarke told USNI News that "the Boise maintenance availability was originally scheduled for Norfolk Naval Shipyard in FY 2016 but was removed from the shipyard due to insufficient capacity to accomplish the work. Boise is now scheduled for a private shipyard availability in FY 2019. The FY 2018 budget includes $89 million for advanced planning for the Boise availability."

Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) commander Vice Adm. Tom Moore told USNI News today that Boise's availability would be competitively bid between Huntington Ingalls' Newport News Shipbuilding and General Dynamics Electric Boat, the two yards that build and maintain nuclear-powered submarines. He said the yards didn't have the capacity to take on another submarine maintenance availability earlier than 2019—Electric Boat has the USS Montpelier (SSN-765) and Newport News Shipbuilding has USS Columbus (SSN-762)—so the Navy will devote 2018 funding to the Boise maintenance planning work and will fund the availability in 2019.

A FY 2019 maintenance availability would amount to a two-and-a-half- to three-and-a-half-year delay in getting the attack submarine into its maintenance period. Tack onto that a year-and-a-half period between when the sub returned home from its last deployment, in January 2015, and when it was originally set to go in for maintenance, and the result is that many sailors – including current Commanding Officer Cmdr. Chris Osborn—will serve a whole tour aboard the ship without deploying overseas.

Navy testimony to lawmakers previously described the situation as having "reached a boiling point this past summer, when in order to balance our workload the Navy decided to defer a scheduled maintenance availability on USS Boise (SSN-764) that will effectively take her offline until 2020 or later."39

A March 30, 2017, press report states:

Despite a hiring push to increase the size of the workforce over the last several years, Naval Sea Systems Command is still short 2,000 workers in its public yards, the head of NAVSEA told lawmakers on Wednesday [March 29].

Vice Adm. Tom Moore told the Senate Armed Service subcommittee on readiness and management support that the Navy has seen the backlog of work in its public yards grow from 4.7 million man-days in 2011 to about 5.3 million man-days this year.

In 2015, NAVSEA had a goal of hiring up to 33,500 workers across its four public yards by the end of fiscal year 2016.

"Today, despite hiring 16,500 new workers since 2012, Naval shipyards are more than 2,000 people short of the capacity required to execute the projected workload," read NAVSEA's written testimony for the hearing.

The testimony said the shortage and the inexperience of the work force—half have less than five years of experience—have extended maintenance availabilities for attack and ballistic missile submarines and aircraft carriers to more than twice their planned length.

Maintenance backlogs have expanded due to increased operational tempo and the slowness of passing budgets, which further delays the yards' ability to execute the work.

"The situation reached a boiling point this past summer, when in order to balance our workload the Navy decided to defer a scheduled maintenance availability on USS Boise (SSN-764) that will effectively take her offline until 2020 or later," the testimony reads.

Following the hearing, Moore told USNI News that the additional personnel would begin the process of clearing backlog and move the service in a positive direction for ship repair.

"What we try and do is try and manage by rearranging schedules to fit what the fleet needs in terms of operational schedules, but eventually it's an inefficient way to do the work," Moore said.

"The current plan, if we can get to the 2,000 additional people we'd like to get to, that will stabilize. We won't grow the backlog anymore, and out past fiscal year 2020 the workload drops off and we'll eventually start working that backlog off in the future."

Moore predicted if the yards get the needed workers the Navy could work off the backlog in maintenance by 2023.40

Issues for Congress

FY2018 Funding

One issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy's FY2018 procurement, advance procurement (AP), and research and development funding requests for the Virginia-class program. In considering this issue, Congress may consider several factors, including the amount of work the Navy is proposing to fund for the program in FY2018 (discussed further in the sections below about achieving a 66-boat SSN force and mitigating the projected valley in SSN force levels), and whether the Navy has accurately priced the work it is proposing to do in FY2018.

Impact of CR on Execution of FY2018 Funding

Another potential issue for Congress concerns the impact of using a continuing resolution (CR) to fund DOD for the first few months of FY2018.3141 Division D of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (H.R. 601/P.L. 115-56 of September 8, 2017) is the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018, a CR that funds government operations through December 8, 2017. Consistent with CRs that have funded DOD operations for parts of prior fiscal years, DOD funding under this CR is based on funding levels in the previous year's DOD appropriations act—in this case, the FY2017 DOD Appropriations Act (Division C of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 [H.R. 244/P.L. 115-31 of May 5, 2017]). Also consistent with CRs that have funded DOD operations for parts of prior fiscal years, this CR prohibits new starts, year-to-year quantity increases, and the initiation of multiyear procurements utilizing advance procurement funding for economic order quantity (EOQ) procurement unless specifically appropriated later. Division D of H.R. 601/P.L. 115-56 of September 8, 2017, does not include any anomalies for Department of the Navy acquisition programs.32

A Navy point paper on the potential effects of a CR on FY2018 Department of the Navy programs states in part (emphasis added):

The following contacts are scheduled to be awarded in Q1 FY18 [the first quarter of FY2018] and would be impacted by a 3 month CR without legislative relief. OMB has already said they are not accepting any requests for legislative relief. Accordingly, these programs will be delayed.

- Columbia Class AP $843M (Oct 2017)

- VA Class submarine AP [work funded with advance procurement funding] $1,921M (Oct 2017)

- CMV-22 (Nov 2017)

- JLTV (Dec 2017)

- KC-130J (Dec 2017)

- Trident Missile subsystems (Nov 2017)

- RAM (Dec 2017)

- Griffin (Dec 2017)

- ESSM (Dec 2017)

- Hellfire Missiles (Dec 2017)33

An August 3, 2017, table of CR impacts to FY2018 DOD programs that was reportedly sent by DOD to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in August 2017 states that the CR will impact the execution of the following:

- about $68.4 million in Virginia-class advance procurement (AP) funding (within a total of about $1,920.6 million of such funding), starting on October 1, 2017; and

about $117.3 million in Virginia-class procurement funding (within a total of about $3,305.3 million of such funding), starting on March 1, 2018.34

44Achieving a 66-Boat SSN Force

Another issue for Congress concerns the Navy's new 66-boat force-level goal for SSNs, which has prompted discussions about how many SSNs would need to be added to the Navy's 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve a 66-boat force, how quickly a 66-boat force could be achieved, how easily the submarine construction industrial base could take on the additional work, and how much it would cost to achieve and maintain a force of 66 SSNs.

Number of Additional Boats Needed in 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

CRS estimates that achieving a 66-boat SSN force would require adding 19 SSNs to the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan. CBO estimates that achieving a 66-boat SSN force would require adding 16 to 19 SSNs to the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan.35

As one possible approach for adding 16 to 19 SSNs to the 30-year shipbuilding plan, 12 Virginia-class boats could be added by inserting a second Virginia-class boat in each of the 12 years (FY2021, FY2024, and FY2026-FY2035) when the Navy also plans to procure a Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine. In other words, the production rate for Virginia- and Columbia-class boats, respectively, in these 12 years would be changed from the currently planned rate 1+1 to a new rate of 2+1. The other four to seven Virginia-class boats that would be needed to get to a total of 16 to 19 additional Virginia-class boats would then be added in years where the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan currently calls for a Virginia- and Columbia-class procurement rate of 2+0, so as to convert those four to seven years into years with a 3+0 rate.

Navy officials, beginning in 2016, have expressed interest in procuring an additional Virginia-class boat in FY2021, so as to convert that year from 1+1 to 2+1. Congress also has the option of funding the procurement of additional Virginia-class boats in FY2018-FY2020. This option is discussed further below, in the section discussing options for mitigating the projected SSN force level valley.

Time Needed to Achieve a 66-Boat Force

CRS and CBO estimate that increasing the SSN procurement rate along the lines described above would permit the SSN force to reach a total of 66 boats by the mid- to late 2030s. Given the capacity of the submarine construction industrial base (see next section), CRS and CBO estimate that this might be the earliest that a 66-boat SSN force could be achieved.

A November 15, 2017, press report states:

The Navy's undersea warfare division is eyeing a stable two-a-year attack submarine rate to reach its ultimate goal of a 66-SSN fleet, despite calls from outside the service to build a larger navy faster.

Acting director of undersea warfare (OPNAV N97) Brian Howes told USNI News today that the service plans to build two Virginia-class submarines a year, which would allow them to reach a 66-boat force by 2048. Building two a year even in years when the Navy buys Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines would be an increase compared to previous plans, which had just one Virginia sub in years when the Navy also bought an SSBN....

... Howes said the OPNAV staff and N97 specifically are committed to two a year.

"All of the divisions in N9 are working on how to establish the right industrial base sustaining rate to build to the levels we need. We talked about at the Sub League Symposium that that's two per year for us, SSNs. If you stay on two per year you end up at the force objective, which is 66. It's in the out-years, but it's stability, and it allows us to maintain the industrial base and not have peaks and valleys in the profile," Howes said in an interview today.

"There's value in having that stable production profile. There may be opportunities to increase that profile, but it's over and above a stable profile. The surface community, the expeditionary community, the aviation community are also looking at similar stable profiles. Where's our objective? What should the profile be to achieve that objective over time?"...

Howes made clear "we're not saying no" to building more than two attack submarines per year, but for now the emphasis is on a predictable and stable build rate for industry.

"If we say we're going to do three a year, we need to give [industry] a signal to do it, and then have them build out their facilities" for a higher build-rate, he said, but an increase to three a year would be dependent on proven industrial base capacity and additional resources—which would likely involve a repeal of the Budget Control Act and its strict spending limits, he said, so the Navy would have a topline to support not only buying more subs but also buying more ships, aircraft, people, and other things needed for a balanced larger force.

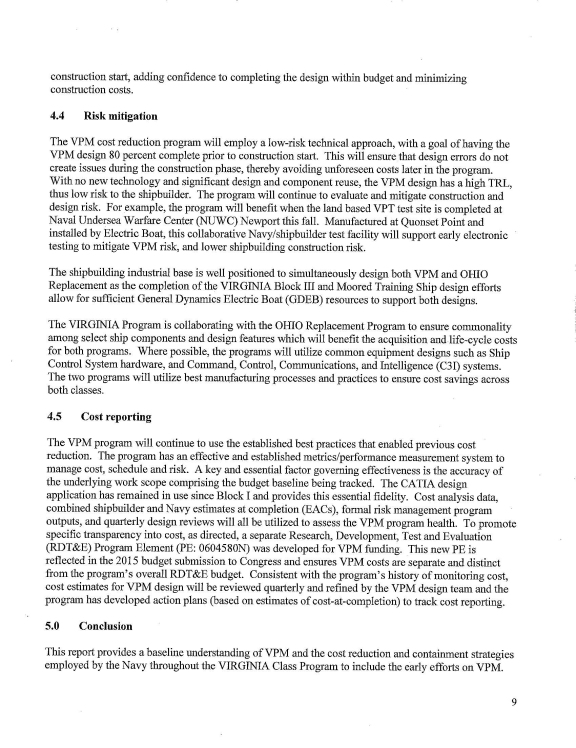

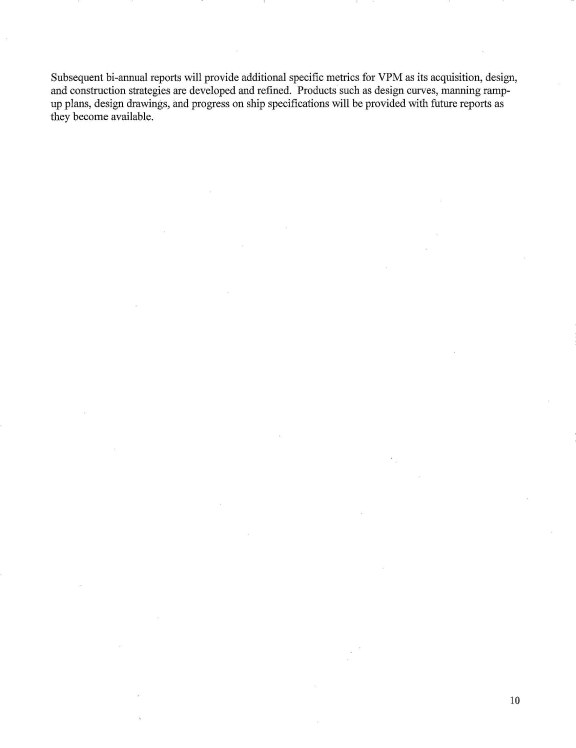

Howes comments are the second this month on the Navy's commitment to building two attack subs a year and no more. Vice Adm. David Johnson, the military deputy to the Navy's acquisition chief, said earlier this month that industry needed to prove it could reliably maintain a 60-month build cycle during two-a-year acquisition before the Navy would consider buying three a year. Those comments were made from a program and industrial base health standpoint, whereas Howes' comments speak to the Navy's requirements and funding intentions....