Wastewater Infrastructure: Overview, Funding, and Legislative Developments

Changes from September 22, 2017 to May 22, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Wastewater Infrastructure: Overview, Funding, and Legislative Developments

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Estimated Funding Needs

- Funding for Wastewater Treatment Activities

- Clean Water State Revolving Fund Program

- Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program

- Other Federal Assistance Programs

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Department of Commerce

- How Localities Pay for

Construction CostsWastewater Infrastructure

- Legislative Activity

- Historical Activity

- Legislative Proposals in the 115th Congress

Summary

The collection and treatment of wastewater remains among the most important public health interventions in human history and has contributed to a significant decrease in waterborne diseases during the past century. Nevertheless, waste discharges from municipal sewage treatment plants into rivers and streams, lakes, and estuaries and coastal waters remain a significant source of water quality problems throughout the country.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) establishes performance levels to be attained by municipal sewage treatment plants in order to prevent the discharge of harmful wastes into surface waters. The act also provides financial assistance so that communities can construct treatment facilities and related equipment to comply with the law. Although approximately $95104 billion in CWA assistance has been provided since 1972, funding needs for wastewater infrastructure remain high. According to the most recent estimate by the Environmental Protection Agency and the states,The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that the nation's wastewater treatment facilities will need $271 billion over the next 20 years to meet the CWA's water quality objectives. Meeting the nation's wastewater infrastructure needs efficiently and effectively is likely to remain an issue of considerable interest to policymakers.

The CWA authorizes the principal federal program to support wastewater treatment plant construction and related eligible activities. Congress established the CWA Title II construction grants program in 1972, significantly enhancing what had previously been a modest grant program. Federal funds were provided through annual appropriations under a state-by-state allocation formula contained in the act. States used their allotments to make grants to cities to build or upgrade categories of wastewater treatment projects including treatment plants, related interceptor sewers, correction of infiltration/inflow of sewer lines, and sewer rehabilitation.

In 1987, Congress amended the CWA and created the State Water Pollution Control Revolving Fund (SRFIn 1987, Congress amended the CWA and created the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) program. This program represented a major shift in how the nation finances wastewater treatment needs. In contrast to the Title II construction grants program, which provided grants directly to localities, SRFsCWSRFs are loan programs. States use their SRFsCWSRFs to provide several types of loan assistance to communities, including project construction loans made at or below market interest rates, refinancing of local debt obligations, providing loan guarantees, and purchasing insurance.

In 2014, Congress revised the SRFCWSRF program by providing additional loan subsidies (including forgiveness of principal and negative interest loans) in certain instances. The law identifies a number of (P.L. 113-121). In addition, the 2014 act increased the types of projects as eligible for SRF assistance, including wastewater treatment plant construction, stormwater treatment and management, energy-efficiency improvements at treatment works, reuse and recycling of wastewater or stormwater, and security improvements at treatment works.

In both FY2016 and FY2017, Congress provided $1.394 billion for the clean water SRF program. President Trump's FY2018 budget proposal requests the same amount as provided for the previous two fiscal years. Although appropriation levels have remained consistent in recent years (in nominal dollars), policymakers have continued to propose changes to the funding program. Issues debated in connection with these proposals include extending SRF assistance to help states and cities meet the estimated funding needs, modifying the program to assist small and economically disadvantaged communities, and enhancing the SRF program to address a number of water quality priorities beyond traditional treatment plant construction—particularly the management of wet weather pollutant runoff from numerous sources, which is the leading cause of stream and lake impairment nationally.

The collection and treatment of wastewater remains among the most important public health interventions in human history and has contributed to a significant decrease in waterborne diseases during the past century. Nevertheless, waste discharges from municipal sewage treatment plants into rivers and streams, lakes, and estuaries and coastal waters remain a significant source of water quality problems throughout the country.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) establishes performance levels to be attained by municipal sewage treatment plants in order to prevent the discharge of harmful wastes into surface waters. The act also provides financial assistance so that communities can construct treatment facilities and related equipment to comply with the law. Although approximately $95 billion in CWA assistance has been provided since 1972, funding needs for wastewater infrastructure remain high. According to the most recent estimate by the Environmental Protection Agency and the states, the nation's wastewater treatment facilities will need $271 billion over the next 20 years to meet the CWA's water quality objectives. Meeting the nation's wastewater infrastructure needs efficiently and effectively is likely to remain an issue of considerable interest to policymakers.

The CWA authorizes the principal federal program to support wastewater treatment plant construction and related eligible activities. Congress established the CWA Title II construction grants program in 1972, significantly enhancing what had previously been a modest grant program. Federal funds were provided through annual appropriations under a state-by-state allocation formula contained in the act. States used their allotments to make grants to cities to build or upgrade categories of wastewater treatment projects including treatment plants, related interceptor sewers, correction of infiltration/inflow of sewer lines, and sewer rehabilitation.

In 1987, Congress amended the CWA and created the State Water Pollution Control Revolving Fund (SRF) program. This program represented a major shift in how the nation finances wastewater treatment needs. In contrast to the Title II construction grants program, which provided grants directly to localities, SRFs are loan programs. States use their SRFs to provide several types of loan assistance to communities, including project construction loans made at or below market interest rates, refinancing of local debt obligations, providing loan guarantees, and purchasing insurance.

In 2014, Congress revised the SRF program by providing additional loan subsidies (including forgiveness of principal and negative interest loans) in certain instances. The law identifies a number of types of projects as eligible for SRF assistance, including wastewater treatment plant construction, stormwater treatment and management, energy-efficiency improvements at treatment works, reuse and recycling of wastewater or stormwater, and security improvements at treatment works.

In both FY2016 and FY2017, Congress provided $1.394 billion for the CWSRF program. However, funding for the program increased by 22% in FY2018. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) provided $1.694 billion to the CWSRF program. In addition, Congress established the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program in 2014 (P.L. 113-121). WIFIA provides direct loans for an array of water infrastructure projects, including CWSRF-eligible projects. EPA issued its first WIFIA loan in April 2018. In FY2018, Congress appropriated $63 million to EPA for the WIFIA program (roughly double the FY2017 appropriation). EPA estimates that this funding will provide approximately $5.5 billion in credit assistance.In both FY2016 and FY2017, Congress provided $1.394 billion for the clean water SRF program. President Trump's FY2018 budget proposal requests the same amount as provided for the previous two fiscal years. Although appropriation levels have remained consistent in recent years (in nominal dollars), policymakers have continued to propose changes to the funding program. Issues debated in connection with these proposals include extending SRFCWSRF assistance.

SRFCWSRF program to address a number of water quality priorities beyond traditional treatment plant construction—particularly the management of wet weather pollutant runoff from numerous sources, which is the leading cause of stream and lake impairment nationally.

Introduction

Waste discharges from municipal sewage treatment plants into inland and coastal waters are a significant source of water quality problems throughout the country.1 Pollutants associated with municipal discharges include nutrients (which can stimulate growth of algae that can deplete dissolved oxygen or produce harmful toxins), bacteria and other pathogens (which may impair drinking water supplies and recreation uses), and metals and toxic chemicals from industrial and commercial activities and households.

The collection and treatment of wastewater remains among the most important public health interventions in human history and has contributed to a significant decrease in waterborne diseases during the past century.2 Funding these systems continues to be of interest to federal, state, and local officials and the general public.

Background

The Clean Water Act (CWA)3 establishes performance levels to be attained by municipal sewage treatment plants in order to prevent the discharge of harmful quantities of waste into surface waters and to ensure that residual sewage sludge meets environmental quality standards. It requires secondary treatment of sewage (equivalent to removing 85% of raw wastes),4 or treatment more stringent than secondary, where needed to achieve water quality standards necessary for recreational and other uses of a river, stream, or lake.

Over the past 40-plus years since the CWA was enacted,Although the nation has made considerable progress in controlling and reducing certain kinds of chemical pollution of rivers, lakes, and streams, much of it because of investments in wastewater treatment. Between 1968 and 1995, oxygen-depleting pollution5 discharged from sewage treatment plants nationwide declined by 45% despite increased industrial activity and a 35% growth in population. The since the 1972 CWA amendments,5 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and others argue that without continued infrastructure improvements, future population growth will erode many of the CWA achievements made to date in pollution reduction are necessary to maintain and expand these achievements.6

The total population served by sewage treatment plants that provide a minimum of secondary treatment increased from 85 million in 1972 to 234 million in 2012,7 representing 74% of the U.S. population at that time.8 About four million people are served by facilities that provide less than secondary treatment, but, according to EPA, these facilities have CWA conditional waivers from the secondary treatment requirement.9 About 21% of households are served by on-site septic systems, not by centralized municipal treatment facilities.10

Despite improvements, other water quality problems related to municipalities remain to be addressed. A key concern is "wet weather" pollution: overflows from combined sewers (sewers that carry sanitary and industrial wastewater, groundwater infiltration, and stormwater runoff that may discharge untreated wastes into streams) and sanitary sewers (sewers that carry only sanitary waste). Untreated discharges from these sewers, which typically occur during rainfall events, can cause serious public health and environmental problems, yet costs to control wet weather problems are high in many cases. In addition, toxic wastes discharged from industries and households to sewage treatment plants cause water quality impairments, operational upsets, and contamination of sewage sludge.

Estimated Funding Needs

Although approximately $95Congress has provided more than $104 billion in CWA assistance has been provided since 1972, funding needs for wastewater infrastructure remain high. According to the most recent estimate by the EPA and the states,11 the nation's wastewater treatment facilities will need $271 billion over the next 20 years to meet the CWA's water quality objectives. This estimate includes

- $197 billion for wastewater treatment and collection systems, which represent 73% of all needs;12

- $48 billion for combined sewer overflow corrections;

- $19 billion for stormwater management; and

- $6 billion to build systems to distribute recycled water.

These estimates do not include potential costs, largely unknown, to upgrade physical protection of wastewater facilities against possible terrorist attacks that could threaten water infrastructure systems, an issue of significant interest since September 11, 2001.

Needs for small communities represent about 12% of the total. The largest needs in small communities are for new conveyance systems (e.g., pipes), secondary treatment, system repair, and advanced treatment. Five states—New York, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Texas, and Alabama—accounted for 30% of the small community needs.

Funding for Wastewater Treatment Activities

In addition to prescribing municipal treatment requirements, the CWA authorizes the principal federal program to support wastewater treatment plant construction and related eligible activities. Congress established this program in the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-500), significantly enhancing what had previously been a modest grant program. Since then, Congress has appropriated approximately $95104 billion to assist cities in complyingsupport compliance with the act and achievingachievement of the overall objectives of the act: restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters.

Title II of P.L. 92-500 authorized grants to states for wastewater treatment plant construction under a program administered by the EPA. Federal funds were provided through annual appropriations under a state-by-state allocation formula contained in the act. The formula (which has been modified several times since 1972) was based on states' financial needs for treatment plant construction and population. States used their allotments to make grants to cities to build or upgrade categories of wastewater treatment projects, including treatment plants, related interceptor sewers, correction of infiltration/inflow of sewer lines, and sewer rehabilitation.

Amendments enacted in 1987 (P.L. 100-4) initiated a new program to support, or capitalize, State Water Pollution ControlClean Water State Revolving Funds (SRFsCWSRFs). States continue to receive federal grants, but now they provide a 20% match and use the combined funds to make loans to communities. Monies used for construction are repaid to states to create a "revolving" source of assistance for other communities.

In FY1989 and FY1990, Congress provided appropriations for both the Title II and Title VI programs. The SRFCWSRF program fully replaced the Title II program in FY1991. However, during the transition from Title II to Title VI, Congress began to provide earmarked water infrastructure grants to individual communities and regions. In subsequent years, the earmarked funds accounted for a significant amount of the total appropriation. General opposition to congressional earmarking stopped the practice in FY2011. Special project appropriations since that time have supported Alaska Native Village and U.S.-Mexico Border projects.13

Federal contributions to SRFsCWSRFs were intended to assist a transition to full state and local financing by FY1995. SRFsCWSRFs were to be sustained through repayment of loans made from the fund after that date. The intention was that states would have greater flexibility to set priorities and administer funding in exchange for an end to federal aid after 1994, when the original CWA authorizations expired. However, although most states believe that the SRFCWSRF is working well today, early funding and administrative problems plus remaining funding needs (discussed below) delayed the anticipated shift to full state responsibility. Congress has continued to appropriate funds to assist wastewater construction activities.

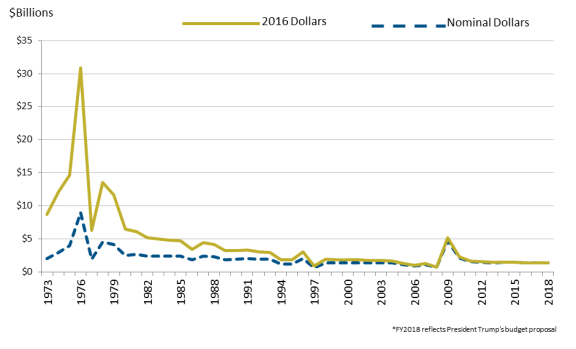

Figure 1 illustrates the history of EPA wastewater infrastructure appropriations in both nominal dollars and constant (20162018) dollars. The increase in FY2009 is due to a $4.0 billion increase in supplemental funds under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). As the figure indicates, the funding level has remained relatively stable overduring the past seven fiscal years. In both FY2016 and FY2017, Congress provided $1.394 billion for the clean water SRF program. The President's FY2018 budget proposal requests the same amount as the previous two fiscal years.

|

Figure 1. EPA Wastewater Infrastructure Annual Appropriations Nominal and Constant (2016) Dollars |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS using information from annual appropriations acts, committee reports, and explanatory statements presented in the Congressional Record. Amounts reflect applicable rescissions and supplemental appropriations, including $7.22 billion in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). Constant dollars calculated from Office of Management of Budget, Table 10.1, "Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940– Notes |

Clean Water State Revolving Fund Program

The SRFCWSRF program represented a major shift in how the nation finances wastewater treatment needs. In contrast to the Title II construction grants program, which provided grants directly to localities, SRFsCWSRFs are loan programs. States use their SRFsCWSRFs to provide several types of loanfinancial assistance to communities, including project construction loans made at or below market interest rates, refinancing of local debt obligations, providing loan guarantees, and purchasing insurance. States may also provide additional loan subsidies (including forgiveness of principal and negative interest loans) in certain instances. Loans are to be repaid to the SRFCWSRF within 30 years beginning within one year after project completion, and the locality must dedicate a revenue stream (from user fees or other sources) to repay the loan to the state.

States must agree to use SRFCWSRF monies first to ensure that wastewater treatment facilities are in compliance with deadlines, goals, and requirements of the act. After meeting this "first use" requirement, states may also use the funds to support other types of water quality programs specified in the law, such as those dealing with nonpoint source pollution and protection of estuaries. The CWA identifies a number of types of projects and activities as eligible for SRFCWSRF assistance. The Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA, P.L. 113-121) amended the list by adding several projects and activities.14

The current list includes15

- wastewater treatment plant construction,

- stormwater treatment and management,

- replacement of decentralized treatment systems (e.g., septic tanks),

- energy-efficiency improvements at treatment works,

- reuse and recycling of wastewater or stormwater, and

- security improvements at treatment works.

States must also agree to ensure that communities meet several specifications (such as requiring that locally prevailing wages be paid for wastewater treatment plant construction pursuant to the Davis-Bacon Act).16 In addition, SRFWRRDA amended the CWA to require that CWSRF recipients must use American-made iron and steel products in their projects.17

As under the previous Title II program, decisions on which projects will receive assistance are made by states using a priority ranking system that typically considers the severity of local water pollution problems, among other factors. States also evaluate financial considerations of the loan agreement (interest rate, repayment schedule, the recipient's dedicated source of repayment) under the SRFCWSRF program.

All states have established the legal and procedural mechanisms to administer the loan program and are eligible to receive SRFCWSRF capitalization grants. Some with prior experience using similar financing programs moved quickly. Others had difficulty in making a transition from the previous grants program to one that requires greater financial management expertise for all concerned. More than half of the states currently leverage their funds by using federal capital grants and state matching funds as collateral to borrow in the public bond market for purposes of increasing the pool of available funds for project lending. Cumulatively since 1988, leveraged bonds have comprised about 3534% of total SRFCWSRF funds available for projects; loan repayments comprise about 40%.18

Small communities and states with large rural populations have had challenges with the SRF program. Many small towns did not participate in the previous grants program and were more likely to require major projects to achieve compliance with the law. Yet manyCWSRF funding programs. Many of these communities have limited financial, technical, and legal resources and encounteredmay encounter difficulties in qualifying for and repaying SRFCWSRF loans. These communities often lack an industrial tax base and thus face the prospect of very high per capita user fees to repay a loan for the full capital cost of sewage treatment projects. Compared with larger cities, many are unable to benefit from economies of scale, which can affect project costs.19 However, since 1989, 6667% of all loans and other assistance (comprising 22% of total funds loaned) have gone to assist towns and cities with populations of less than 10,000.19

Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program

The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of 2014 (WIFIA) program provides another source of financial assistance for water infrastructure. Congress established the WIFIA program in the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA, P.L. 113-121).20WRRDA.21 The act, among other provisions, authorizes EPA to provide credit assistance (e.g., secured/direct loans or loan guarantees)22 for a range of wastewater and drinking water projects. Project costs must be $20 million or larger to be eligible for credit assistance. In rural areas (defined as populations of 25,000 or less), project costs must be $5 million or more. To fund this five-year pilot program, Congress authorized to be appropriated a total of $1.75 billion from FY2015 through FY2019.

In 2016, Congress appropriated the first funds to cover the subsidy cost of the program,2123 providing $20 million to EPA to begin making loans, and allowed the agency to use up to $3 million of the total for administrative purposes. In May 2017, Congress provided an additional $8 million for EPA to apply toward loan subsidy costs and an additional $2 million for EPA's administrative expenses.22

EPA expects to issue its first WIFIA loans in 2017.23 From the federal perspective, an advantage of WIFIA is that it can provide a large amount of credit assistance relative to the amount of budget authority provided. The volume of loans and other types of credit assistance that the programs can provide is determined by the size of congressional appropriations and calculation of the subsidy amount. EPA stated that the combined appropriation for subsidy costs ($25 million) will allow the agency to lend approximately $1.5 billion for water infrastructure projects.24 The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget proposal requested $29 billion to cover subsidy costs, which it estimated could provide $1.9 billion in credit assistance.25

Other Federal Assistance Programs26

began accepting loan applications for its WIFIA program in January 2017. EPA received 43 letters of interest from prospective borrowers in the agency's first round of funding solicitation. In aggregate, the prospective borrowers requested $6 billion in WIFIA loans.25 In July 2017, EPA selected 12 projects to continue the application process. The loan amounts requested for the projects ranged from $22 million to $625 million for a total of $2.3 billion.26

For FY2018, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), provided $63 million for the WIFIA program (including $8 million for administrative costs). EPA announced a second round of WIFIA funding on April 4, 2018. EPA estimated that its budget authority ($55 million) would provide approximately $5.5 billion in credit assistance.

Other Federal Assistance Programs27In addition to the water infrastructure assistance programs discussed above, which are administered by EPA, other federal agencies implement broader programs that may provide assistance for wastewater infrastructure projects.

Department of Agriculture

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) operates grant and loan programs for drinking water supply and wastewater facilities in rural areas, defined as areas of not more than 10,000 persons. For FY2017FY2018, Congress appropriated $571895 million for USDA's rural water and waste disposal grants and loans. For FY2018, the President's budget request proposed to eliminate funding for these programs.

Department of Housing and Urban Development

The Department of Housing and Urban Development administers the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. For FY2017FY2018, Congress provided $3.13 billion for these funds. Water and waste disposal projects compete with many other CDBG-funded public activities and have accounted for approximately 10% of total grant disbursements in recent years.27

Department of Commerce

The Department of Commerce's Economic Development Administration (EDA) provides project grants for construction of public facilities—including, but not limited to, water and sewer systems—as part of approved overall economic development programs in areas of lagging economic growth. For FY2017FY2018, the public works and economic development program is funded at $100118 million.

How Localities Pay for Construction Costs

Wastewater Infrastructure

The federal government directly funds only a small portion of the nation's annual wastewater treatment capital investment. State and local governments provide the majority of needed funds. Local governments have primary responsibility for wastewater treatment: They own and operate approximately 15,000 treatment plants nationwide.2830 Construction of these facilities has historically been financed with revenues from federal grants, state grants to supplement federal aid, and revenue from broad-based local taxes (property tax, retail sales tax, or, in some cases, local income tax). Where grants are unavailable—and especially since SRFsCWSRFs were established—local governments often seek financing by issuing bonds and then levying fees or charges on users of public services to repay the bonds in order to cover all or a portion of local capital costs. Almost all such projects are debt-financed (not financed on a pay-as-you-go basis from ongoing revenues to the utility). The principal financing tool that local governments use is issuance of tax-exempt municipal bonds. The vast majority of U.S. water utilities rely on municipal bonds and other debt to some degree to finance capital investments.29

Shifting the CWA aid program from categorical grants to the SRFCWSRF loan program in 1990 had the practical effect of making localities ultimately responsible for nearly 100% of project costs rather than less than 50% of costs.3032 This has occurred concurrently with other financing challenges—including the need to fund other environmental services, such as drinking water and solid waste management—and increased operating costs. (New facilities with more complex treatment processes are more costly to operate.) Options that localities face, if intergovernmental aid is not available, include raising additional local funds (through bond issuance, increased user fees, developer charges, or general or dedicated taxes), reallocating funds from other local programs, or failing to comply with federal standards. Each option carries with it certain practical, legal, and political problems.

Legislative Activity

Historical Activity

Authorizations of appropriations for SRFCWSRF capitalization grants expired in FY1994, making this an issue of congressional interest. Appropriations have continued, as shown in Figure 1. In the 104th Congress, the House passed a comprehensive reauthorization bill (H.R. 961), which included SRFCWSRF provisions to address problems that have arisen since 1987, including assistance for small and disadvantaged communities and expansion of projects and activities eligible for SRFCWSRF assistance. However, no legislation was enacted because of controversies over other parts of the bill.

One ongoing focus has been on projects needed to control wet weather water pollution (i.e., overflows from combined and separate stormwater sewer systems). The 106th Congress authorized $1.5 billion of CWA grant funding specifically for wet weather sewerage projects (in P.L. 106-554), because under the SRFCWSRF program, wet weather projects compete with other types of eligible projects for available funds. However, authorization for these wet weather project grants expired in FY2003 and has not been renewed. No funds were appropriated.

In several Congresses since the 107th, House and Senate committees have approved bills to extend the act's SRFCWSRF program and increase authorization of appropriations for SRFCWSRF capitalization grants, but no legislation has been enacted until recently. Issues debated in connection with these bills included extending SRFCWSRF assistance to help states and cities meet the estimated funding needs, modifying the program to assist small and economically disadvantaged communities, and enhancing the SRFCWSRF program to address a number of water quality priorities beyond traditional treatment plant construction—particularly the management of wet weather pollutant runoff from numerous sources, which is the leading cause of stream and lake impairment nationally.

The 113th Congress enacted considerable changes to the SRFCWSRF provisions of the CWA in 2014 (P.L. 113-121). These amendments addressed several issues, including extending loan repayment terms from 20 years to 30 years, expanding the list of SRFCWSRF-eligible projects, increasing assistance to Indian tribes, and imposing "Buy American" America" (iron and steel) requirements on SRFCWSRF recipients. The act also added a new provision that allows SRFCWSRF grants to be used for "forgiveness of principal" and "negative interest loans" under certain conditions.

The 2014 amendments did not address other long-standing or controversial issues, such as authorization of appropriations for SRFCWSRF capitalization grants (which expired in FY1994), state-by-state allocation of capitalization grants,3133 and applicability of prevailing wage requirements under the Davis-Bacon Act (which currently apply to use of SRFCWSRF monies).

As noted, the 2014 legislation also included provisions authorizing a five-year pilot program (WIFIA) for a new type of financing. The WIFIA program authorizes federal loans and loan guarantees for various types of wastewater and public drinking water infrastructure projects. The WIFIA program is intended to assist large water infrastructure projects, especially projects of regional and national significance, and to supplement but not replace other types of financial assistance, such as SRFs. In the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254), enacted in December 2016, Congress appropriated $20 million to EPA to begin making loans, and it allowed the agency to use up to $3 million of the total for administrative purposes. The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2017, signed by President Trump on May 5, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), provided an additional $8 million for EPA to apply toward loan subsidy costs and an additional $2 million for EPA's administrative expenses. EPA expects to issue its first WIFIA loans in 2017.32

In the 114th Congress, the Senate passed the Water Resources Development Act (S. 2848), which included several provisions involving wastewater funding. For the most part, these provisions were not included in the final version of this legislation, which Congress enacted in December 2016 (Water Infrastructure and Improvements for the Nation Act, P.L. 114-322).33

Legislative Proposals in the 115th Congress

Although interest in meeting the nation's water infrastructure needs is strong and likely to continue, proposals to provide financial assistance to local communities will compete with other objectives, including deficit reduction. It is uncertain how infrastructure programs will fare in these debates.

Legislative proposals introduced in the 115th Congress that include wastewater infrastructure related provisions are highlighted below.34

H.R. 465(Water Quality Improvement Act of 2017) would codifyidentified in Table 1 below.35 Table 1. Wastewater Infrastructure Legislative Proposals in the 115th CongressListed Chronologically with Identical Bills Grouped Together

Bill Number -Introduced Date

Primary Sponsor

Committee of Floor Action

Key Wastewater Provisions

Gibbs

Water Quality Improvement Act of 2017

an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA,35directEPA to carry out a pilot program to work with at least 15 communities desiring to implement an integrated CWA compliance plan, andrequirerequires EPA to update its 1997 combined sewer overflow affordability guidance document.It includesIncludes provisions that may alter the existing CWA framework.- H.R. 1068 (Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 2017) and H.R. 1071 (Assistance, Quality, and Affordability Act of 2017) would incorporate in the statute a governor's authority to transfer as much as 33% of the annual drinking water SRF or clean water SRF capitalization grant to the other fund.36

H.R. 1647(Water Infrastructure Trust Fund Act of 2017) would directS. 181January 20, 2017Brown

Directs the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to publish a report determining whether a domestic content preference requirement (e.g., iron, steel, and manufactured products) applies to identified federal public works and infrastructure programs, including the CWSRF. Prohibits federal funds or credit assistance for a program that lacks a domestic content preference.

Wicker

Small and Rural Community Clean Water Technical Assistance Act

Reported by the Committee on Environment and Public Works on May 17, 2017 (S.Rept. 115-71)

Authorizes EPA to issue grants to qualified nonprofit entities to provide technical assistance to owners and operators of "small" and "medium" wastewater treatment facilities.

Harper

Small and Rural Community Clean Water Technical Assistance Act

Fischer

Water Infrastructure Flexibility Act

Passed Senate on October 5, 2017; reported by the Committee on Environment and Public Works on May 25, 2017 (S.Rept. 115-87)

Codifies an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA. Establishes an Office of the Municipal Ombudsman to provide assistance to municipalities and requires EPA to update its 1997 combined several overflow affordability guidance document. Includes provisions that may alter the existing CWA permitting and compliance framework.

Smucker

Water Infrastructure Flexibility Act

Latta

Water Infrastructure Flexibility Act

Blumenauer

Water Infrastructure Trust Fund Act of 2017

TheInstructs Secretarywouldto provide a label for a fee of 3 cents per unit. Funds would be made available only when theclean water SRFCWSRF appropriation is not less than the average of the five preceding fiscal years. Funds made available for a fiscal year would be split equally between the clean water and drinking water SRF programs.H.R. 1673(H.R. 1673April 11, 2017Conyers

) would (1) establishEstablishes a trust fund with funds going to EPA to support clean water and drinking water SRFs and activities and totheUSDA for household water well systems; (2) direct. Directs EPA to report on water affordability nationwide, discriminatory practices of water and sewer service providers, and water system regionalization; (3) require. Requires states to use at least 50% of their capitalization grants to provide additional subsidization to disadvantaged communities; and (4) require. Requires states to permit recipients ofSRFCWSRF assistance to enter into project labor agreements under the National Labor Relations Act.- H.R. 1971, H.R. 2355, and S. 692 (Water Infrastructure Flexibility Act) would codify an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA, establish an Office of the Municipal Ombudsman to provide assistance to municipalities, and require EPA to update its 1997 combined several overflow affordability guidance document. It includes provisions that may alter the existing CWA permitting and compliance framework.

H.R. 2510(Water Quality Protection and Job Creation Act of 2017) would, among other provisions, amend the CWA (33 U.S.C. §2512)S. 1137May 16, 2017Cardin

Clean Safe Reliable Water Infrastructure Act

Reauthorizes combined sewer overflow grants under CWA Section 221.

DeFazio

Water Quality Protection and Job Creation Act of 2017

; reauthorize. Reauthorizes appropriations for the pollution control grant program(Section 1256); authorize. Authorizes appropriations for the watershed pilot programin Section 1274; amend. Amends appropriation authorization for the nonpoint source management programin Section 1329; amend the SRF. Amends the CWSRF grant agreement section(Section 1382)to require states to use at least 15% of theirSRFCWSRF grants to provide assistance to municipalities of fewer than 10,000 individuals that meet affordability criteria; amend SRF project eligibility (Section 1383). Amends CWSRF project eligibility to allow states to provide a limited amount ofgrantsgrants to (1) treatment works in small (less than 10,000) communities and (2) treatment works for energy and water efficiency activities; amend. Amends the priority list provisions(Section 1383)to, among other things, allow for the inclusion of nonpoint source projects; reauthorize. Reauthorizes appropriations for theSRF program; and reauthorizeCWSRF program. Reauthorizes appropriations for the sewer overflow grant program. H.R. 3009June 22, 2017Duncan

Sustainable Water Infrastructure Investment Act of 2017

Amends the tax code to provide that the volume cap for private activity bonds shall not apply to bonds for sewage (and drinking water) facilities.

Larson

America Wins Act

Establishes a carbon tax on fossil fuels. The revenues would support a variety of objectives. In particular, $6 billion would be allotted annually to support wastewater and drinking water infrastructure.

Booker

Establishes a grant program (administered by EPA and the Secretary of the Army) for water utilities to provide funding for job training and apprenticeship programs in the water infrastructure sector.

Boozman

Securing Required Funding for Water Infrastructure Now Act

Amends WIFIA by authorizing EPA to provide financial assistance (e.g., secured loans) to SRF programs to support eligible wastewater and drinking water projects. Although this is currently authorized under WIFIA, the new WIFIA section would authorize EPA to provide secured loans at subsidized interest rates for certain states, including states that received less than 2% of the SRF funds in the most recent year or states in which the President declared a major disaster in 2017 through the enactment date. Funding for the subsidized loans would be capped. Unlike other WIFIA assistance, the federal assistance under this section would be able to support 100% of project costs, and application fees would be waived. No funding would be available if the SRF program appropriation is less than the amount provided in FY2018.

Katko

Securing Required Funding for Water Infrastructure Now Act

Gillibrand

Protecting Infrastructure and Promoting the Economy Act

Establishes an EPA grant program to provide direct funding for wastewater and drinking water infrastructure projects. Projects include those eligible in the SRF programs.

Carbajal

Water Infrastructure Resiliency and Sustainability Act of 201

Establishes an EPA grant program to provide funding to owners or operators of water systems (including decentralized wastewater systems) to increase the resiliency or adaptability of the systems. Private recipients must have public sponsorship to receive funding.

Ellison

Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity, and Reliability Act of 2018

Establishes a new trust fund to support EPA and USDA water infrastructure programs, particularly the SRF programs. The fund would be financed with revenues generated by an increase in the corporate rate from 21% to 24.5%. (In 2017, P.L. 115-97 decreased the rate from 35% to 21%.) Directs EPA to conduct a study on affordability and effectiveness of SRF program funding, among other issues. Amends the CWA to authorize EPA to make grants to nonprofit organizations to provide technical assistance and training to rural and small municipalities. Establishes an EPA grant program for repairing or upgrading decentralized systems (e.g., septic tanks). Amends the CWSRF provisions so the (20%) state match would apply to FY2016 funding levels going forward. Prohibits CWSRF funds from supporting a new community unless used for decentralized wastewater systems. Alters the CWSRF eligibility categories to allow state or local government to purchase a privately owned treatment system. Increases the minimum subsidization in Section 1383(i) from 30% to 50%.

Booker

Residential Decentralized Wastewater System Improvement Act

Establishes an EPA program to provide grants to nonprofit entities. These entities provide subgrants (not to exceed $20,000) to low-income households for construction, refurbishing, and servicing of decentralized wastewater systems. Grants may be used to connect to a public wastewater system if deemed more cost effective by the nonprofit entity.

Booker

Amends the USDA Rural Utilities Service wastewater and drinking water grant and loan program.

Barrasso

America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018

Directs EPA to establish a stormwater funding taskforce to study and prepare recommendations regarding stormwater funding issues. Reauthorizes the WIFIA program. Directs EPA to carry out a pilot program (subject to appropriations) on Indian tribe lands to implement drinking water or wastewater projects. Authorizes EPA to issue grants to qualified nonprofit entities to provide technical assistance to owners and operators of "small" and "medium" wastewater treatment facilities. Codifies an integrated plan and permit approach into the CWA. Establishes an Office of the Municipal Ombudsman to provide assistance to municipalities and requires EPA to update its 1997 combined several overflow affordability guidance document. Includes provisions that may alter the existing CWA permitting and compliance framework. Instructs EPA to promote the use of green infrastructure. Directs EPA to disseminate information regarding effectiveness of alternative wastewater systems, including decentralized systems. For wastewater projects serving populations less than 2,500, an entity receiving SRF, WIFIA, or USDA funding must certify that it has considered decentralized systems as an alternative. Establishes a grant program (administered by EPA and the Secretary of the Army) for water utilities to provide funding for job training and apprenticeship programs in water infrastructure sector. Directs GAO to conduct a study on ways to create flexibility under WIFIA for small, rural, disadvantaged, and tribal communities

Source: Prepared by CRS. The above list of bills may not be exhaustive.

appropriations for the sewer overflow grant program in Section 1301.- H.R. 3009 (Sustainable Water Infrastructure Investment Act of 2017) would amend the tax code to provide that the volume cap for private activity bonds shall not apply to bonds for sewage (and drinking water) facilities.

- S. 181 would require the Government Accountability Office to publish a report determining whether a domestic content preference requirement (e.g., iron, steel, and manufactured products) applies to identified federal public works and infrastructure programs, including the clean water SRF. No federal funds or credit assistance could be made available for a program that lacks a domestic content preference.

- S. 518 (Small and Rural Community Clean Water Technical Assistance Act) would authorize EPA to issue grants to qualified nonprofit entities to provide technical assistance to owners and operators of "small" and "medium" wastewater treatment facilities.

- S. 1137 (Clean Safe Reliable Water Infrastructure Act) would codify in statute EPA's existing WaterSense Program and reauthorize combined sewer overflow grants under CWA Section 221.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

[author name scrubbed], who has retired from CRS, wrote the original version of this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Pursuant to the Clean Water Act, Section 305, states submit biennial reports to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) assessing the water quality of their surface waters. See EPA, National Summary of State Information, "Probable Sources of Impairments in Assessed Rivers and Streams," https://ofmpub.epa.gov/waters10/attains_nation_cy.control. |

|

| 2. |

See, for example |

|

| 3. |

The statutory name is the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, |

|

| 4. |

33 U.S.C. §1311 and §1314(d). Pursuant to these provisions, EPA issued regulations with specific secondary treatment requirements in 1973, including the 85% removal performance standard (38 Federal Register 22298, August 17, 1973). These regulations are codified in 40 C.F.R. Part 133. |

|

| 5. |

| |

| 6. |

|

|

| 7. |

See Table 3 in EPA, Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012, Report to Congress, 2016. |

|

| 8. |

At the end of 2012, the U.S. population was approximately 315 million. U.S. Census population clock, https://www.census.gov/popclock/. |

|

| 9. |

CWA Section 301(h) authorizes EPA (with the concurrence of a state) to modify the secondary treatment requirements under certain conditions. |

|

| 10. |

U.S. Census Bureau, American Housing Survey (AHS), Plumbing, Water, and Sewage Disposal Table, 2015, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html. |

|

| 11. |

EPA, Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012, Report to Congress, 2016, https://www.epa.gov/cwns. |

|

| 12. |

This includes $102 billion for wastewater treatment (38%) and $96 billion for conveyance systems, which includes new systems and repairs for older systems (35%). |

|

| 13. |

For more details, see CRS Report 96-647, Water Infrastructure Financing: History of EPA Appropriations, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|

| 14. |

P.L. 113-121, Title V, Subtitle A. |

|

| 15. |

33 U.S.C. §1383(c). |

|

| 16. |

33 U.S.C. §1382(b)(6), which references §1372. |

|

| 17. |

P.L. 113-121, Section 5004; 33 U.S.C. §1388. |

|

| 18. |

EPA, Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) National Information Management System Report, "U.S. National Total," https://www.epa.gov/cwsrf/clean-water-state-revolving-fund-cwsrf-national-information-management-system-reports. |

|

19.

|

|

20.

See, for example, Government Accountability Office, Federal Agencies Provide Funding but Could Increase Coordination to Help Communities, 2015. |

EPA website on |

|

P.L. 113-121, Title V, Subtitle C. For more information see CRS Report R43315, Water Infrastructure Financing: The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) Program, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

||

|

|

23.

Although WIFIA credit assistance may include direct loans and loan guarantees, EPA stated that based on experience from comparable government credit programs, the agency does not anticipate immediate demand for loan guarantee instruments. See EPA, WIFIA Program Handbook, 2017, https://www.epa.gov/wifia. |

The Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254). |

|

The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31). |

||

|

|

||

|

EPA, |

||

|

|

||

|

| ||

|

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, "National Expenditure Reports, FY2001- |

||

|

Based on data collected in 2012. See EPA, Clean Watersheds Needs Survey 2012, Report to Congress, 2016. |

||

|

See testimony of Aurel Arndt, American Water Works Association, in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, "The Federal Role in Keeping Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Affordable," 114th Cong., 2nd sess., April 7, 2016. According to a 2013 study, 48 states used tax-exempt financing to fund water infrastructure projects in 2012. See National Association of Clean Water Agencies and Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies, "The Impacts of Altering Tax-Exempt Municipal Bond Financing on Public Drinking Water and Wastewater Systems," 2013. |

||

|

Over the history of the construction grants program, federal grants generally covered from 55% to 75% of project costs (CWA §202). |

||

|

|

||

| 32. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43315, Water Infrastructure Financing: The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) Program, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|

|

For further details, see CRS In Focus IF10471, WRDA Legislation in the 114th Congress: Clean Water Act and Infrastructure Financing Provisions in S. 2848 and WIIN, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||

|

This list may not be exhaustive. |

||

| 35. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44223, EPA Policies Concerning Integrated Planning and Affordability of Water Infrastructure, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|

| 36. |

|