Respirable Crystalline Silica in the Workplace: New Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standards

Changes from May 31, 2017 to September 29, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Respirable Crystalline Silica in the Workplace: New Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standards

Contents

- Overview of the New Standards

- Crystalline Silica in the Workplace

- Rationale for the New Standards

- Permissible Exposure Limit

- Previous PELs

- NIOSH Recommended PEL

- Compliance Schedule

- Projected Costs and Benefits

- Opposition to the New Standards

- Cost Projections

- Benefit Projections

- Legislative Activity

- Legal Challenges

Summary

On March 25, 2016, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the Department of Labor (DOL) published new standards regulating exposure to crystalline silica in the workplace. Under the new standards, the Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) for crystalline silica will be reduced to 50 µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter of air). Employers will be required to monitor crystalline silica exposure if workplace levels may exceed 25 µg/m3 for at least 30 days in a year and provide medical monitoring to employees in those workplaces. In the case of construction workers, medical monitoring is required only if the new standards require workers to wear respirators for at least 30 days in a year.

Construction industry employers are exempt from the PEL and exposure monitoring requirements if they comply with the engineering controls and work practices specified in the new standards. The new standards are scheduled to be phased in over the next five years, beginning June 23, 2017, with different implementation dates for construction, general industry, and hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

OSHA projects that the new crystalline silica standards will prevent 642 deaths per year, costing employers just over $1 billion annually. The net monetary benefits of the new standards are projected to be $7.6 billion annually based on reducedreduced mortality and morbidity related to exposure to crystalline silica.

Groups representing employers, labor, and manufacturers have filed court challenges to the new standards. Employer and manufacturer groups claim that OSHA projections are inaccurate and that compliance may not be feasible. Labor groups want stronger medical surveillance of exposed workers and protections for workers showing evidence of medical conditions linked to crystalline silica exposure.

Overview of the New Standards

On March 25, 2016, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the Department of Labor (DOL) published in the Federal Register new standards governing exposure to respirable crystalline silica in the workplace.1 Key features of the new crystalline silica standards include the following requirements for employers:

- protect workers when exposure to respirable crystalline silica exceeds the new Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) of 50 µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter of air), as an eight-hour time-weighted average (TWA), through the use of engineering controls, or if such controls are not effective, the use of respirators;

- measure workers' exposure to respirable crystalline silica if such exposure may reach or exceed levels of 25 µg/m3 as an eight-hour TWA;

- limit workers' access to areas where they may be exposed to respirable crystalline silica;

- offer medical exams, including chest x-rays and lung function tests, every three years to workers exposed to crystalline silica at or above the level of 25 µg/m3 as an eight-hour TWA for 30 or more days in a year or to construction workers required to wear respirators for 30 or more days in a year;

- train workers to limit exposure to respirable crystalline silica; and

- maintain records of workers' exposure to respirable crystalline silica and employer-provided medical exams.

These new standards will be phased in over a five-year period, beginning June 23, 2017, with different implementation dates for construction, general industry, and hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

The standards provide employers in the construction industry an exemption from the PEL and requirement to measure employee exposure to crystalline silica if these employers follow the engineering controls and work practices of the new standards, as outlined in Table 1 of the new standards. For example, if a stationary masonry saw is used in construction, the employer is exempt from the PEL and requirement to measure silica exposure if the following controls and practices are used:

Use saw equipped with integrated water delivery system that continuously feeds water to the blade. Operate and maintain tool in accordance with manufacturer's instructions to minimize dust emissions.2

Crystalline Silica in the Workplace

Crystalline silica is a compound found in the earth's crust. It is a component of soil, sand, and other natural materials. The three most common forms of crystalline silica are quartz, cristobalite, and tridymite. Crystalline silica in dust commonly occurs when workers cut, saw, grind, drill, or crush materials such as glass, stone, rock, concrete, brick, or industrial sand. Exposure also occurs when industrial sand is used in abrasive operations, such as sandblasting, and in the hydraulic fracturing (fracking) process.3

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) estimates that 1.7 million workers are exposed to crystalline silica in the workplace.4 However, NIOSH's estimates are based on 1986 data, which were published in 1991.5 In the preamble to its new crystalline silica standards, OSHA estimates that more than 2.3 million workers are potentially exposed to crystalline silica in the workplace, including more than 2 million workers in the construction industry.6

Crystalline silica particles can be 100 times smaller than normal sand particles. Because of their small size, these particles can easily enter the human respiratory system. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)7 and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) National Toxicology Program has identified crystalline silica as a human carcinogen.8 The respiration of crystalline silica has been associated with the incurable disease silicosis and other respiratory diseases, such as pulmonary tuberculosis and lung cancer; auto-immune diseases, such as scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus; and renal disease and renal changes.9

The health effects of crystalline silica and the link between occupational exposure to crystalline silica and silicosis and other diseases have been known since the beginning of the 20th century, when cases of "consumption" and "phthisis" were documented among miners, stonecutters, glass workers, and other workers in the United States and other countries.10 In 1931, several hundred workers died of acute silicosis after being exposed to silica during the construction of Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation's Hawk's Nest Tunnel in Gauley Bridge, WV, making this exposure one of the deadliest single incidents of occupational disease in American history.11

The federal government, under the provisions of the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Act (EEOICPA), currently provides a $150,000 cash benefit and health benefits to workers, or their survivors, who contracted chronic silicosis as a result of digging tunnels in Alaska and Nevada used for the underground testing of atomic weapons.12

Rationale for the New Standards

In the preambles to its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) and Final Rule, OSHA lays out a detailed rationale for the new crystalline silica standards. OSHA claims that based on an extensive review of existing literature and research that identifies links between exposure to crystalline silica and various medical conditions, including silicosis, cancers, renal conditions, and other diseases, the new standards will prevent more than 600 silica-related deaths each year and reduce monetarized benefits by reducing mortality and morbidity, which far exceed projected costs of compliance.

In preparing its new crystalline silica standards, OSHA conducted a Preliminary Quantitative Risk Assessment and Final Quantitative Risk Assessment. Both assessments consisted of an extensive review of published literature and research on the health effects of occupational exposure to crystalline silica. OSHA performed these risk assessments in compliance with Section 6(b)(5) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act), which states, in part,

Development of standards under this subsection shall be based upon research, demonstrations, experiments, and such other information as may be appropriate. In addition to the attainment of the highest degree of health and safety protection for the employee, other considerations shall be the latest available scientific data in the field, the feasibility of the standards, and experience gained under this and other health and safety laws ... 13

Before the Preliminary Quantitative Risk Assessment, a draft health effects review document was subject to external peer review in accordance with Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines.14 As a result of the Final Quantitative Risk Assessment, OSHA concludes in the preamble to its Final Rule:

[T]here is convincing evidence that inhalation exposure to respirable crystalline silica increases the risk of a variety of adverse health effects, including silicosis, NMRD (such as chronic bronchitis and emphysema), lung cancer, kidney disease, immunological effects, and infectious tuberculosis (TB).15

Permissible Exposure Limit

The new standards set a uniform PEL of 50 µg/m3 measured as an eight-hour TWA. If workers are exposed to crystalline silica above the PEL, they must be protected through engineering controls, such as using water to control dust generated by a work process or respirators provided by the employer. Because the PEL is measured as an eight-hour TWA, a worker can be exposed to levels above the PEL periodically during the work day, provided that his or her average exposure over eight hours does not exceed the 50 µg/m3.

Previous PELs

Prior to the promulgation of the new crystalline silica standards, the OSHA occupational safety and health standards (the old standards) did not include a universal PEL for all industries and types of crystalline silica. In addition, the PELs in the old standards, as published in the Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.), are not directly comparable to the new PELs. The PELs in the old standards are expressed as a formula of volume of crystalline silica per cubic meter of air, divided by the percentage of silicon dioxide (SiO2); or as millions of particles per cubic foot of air, divided by the percentage of SiO2.16

In its NPRM on the new standards, OSHA reports that the particle-count methodology used to determine the number of particles per cubic foot of air is obsolete.17

In its NPRM, OSHA also provides the following estimates of the old-standard PELs expressed using the new methodology of µg/m3, measured as an eight-hour TWA:

- quartz in general industry: 100 µg/m3;

- quartz in construction industry: 250 µg/m3;

- quartz in shipyard industry: 250 µg/m3;

- cristobalite in all industries: 50 µg/m3; and

- tridymite in all industries: 50 µg/m3.18

The old-standard PELs trace their history to a report from the U.S. Public Health Service in 1929, which examined exposure to silica among workers in the granite-cutting industry in Barre, VT.19 The report recommended an exposure limit of between 10 million and 20 million particles per cubic foot (mppcf) for dust containing approximately 35% free silica (which includes crystalline silica) in the form of quartz and stated that this level could be "obtained by the use of economically practicable ventilating devices applied to the source of the dust."20 A review of the report stated,

It should be pointed out that the limit established was not found to prevent the occurrence of silicosis. It was found, however, that there seemed to be no particular liability to pulmonary tuberculosis where the concentration of dust was within this limit.21

OSHA's Original PELs

Section 6(a) of the OSH Act required OSHA to convert existing federal occupational safety and health standards and national consensus standards into OSHA standards within two years of enactment of the OSH Act.22 In 1971, OSHA's original PELs for crystalline silica were promulgated based on the existing PELs provided in regulations implementing the Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act of 1936, which established certain standards for federal contractors.23 The Walsh-Healey regulations were based on the 1968 Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) established by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH).24 The ACGIH TLVs were based on the recommendations in the 1929 U.S. Public Health Service Report.25

OSHA's Attempt to Update the PELs

In 1989, OSHA updated nearly all of its PELs, including those for crystalline silica.26 The updated PELs for general industry were not increased, but rather were converted from the outdated formulas to measures of µg/m3 of air. In 1992, OSHA proposed changing the crystalline silica PELs for the construction, agriculture, and maritime industries such that all industries would have the same PELs of 100 µg/m3 for quartz and 50 µg/m3 for cristobalite and tridymite.27 These changes would have resulted in a reduction in the PELs for the construction and maritime industries. In 1992, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit vacated the 1989 changes to the PELs and mooted the 1992 proposed changes, thus returning the PELs back to their original levels set in 1971.28 These 1971 levels are replaced by the new PELs promulgated in 2016.

NIOSH Recommended PEL

In 1974, NIOSH issued a recommended PEL for crystalline silica of 50 µg/m3, measured as a 10-hour workday, 40-hour week TWA.29 In response to this recommendation, OSHA in 1974 published an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) seeking public comments on whether a new crystalline silica standard should be promulgated based on the NIOSH recommendation or any other factors.30 More than 40 years after the NIOSH recommendation and the ANPRM, the new OSHA crystalline silica PEL will essentially match the NIOSH recommendation, although it will be measured as an average over an eight8-hour day.

Compliance Schedule

The new crystalline silica standards taketook effect June 23, 2016. However, employers arewere not required to comply with the new standards at that time. Rather, compliance will be implemented according to the following schedule:

- construction industry—September 23, 2017,31 except for provisions related to the analysis of air samples, which require compliance by June 23, 2018;

- good faith compliance assistance—On September 20, 2017, OSHA announced that during the first 30 days of enforcement of the standards for the construction industry, the agency would provide compliance assistance, rather than issue citations, to employers making "good faith efforts" to comply with the new standards.32

general industry (except hydraulic fracturing) and maritime industry—two years after the effective date (June 23, 2018), except for medical surveillance, which is required to begin for employees exposed at or above the PEL for 30 days in a year by June 23, 2018, and for employees exposed at or above the level of 25 µg/m3 by June 23, 2020; and- hydraulic fracturing—two years after the effective date (June 23, 2018), except for medical surveillance, which is required to begin for employees exposed at or above the PEL for 30 days in a year by June 23, 2018, and for employees exposed at or above the level of 25 µg/m3 by June 23, 2020, and also except for engineering controls provisions, which require compliance by June 23, 2021.

Projected Costs and Benefits

OSHA projects that the implementation of its new crystalline standards will prevent 642 silica-related deaths per year and produce annual benefits of approximately $8.7 billion through mortality and morbidity reductions.3233 OSHA also projects that annual benefits will be more than eight times greater than the annual projected costs of compliance with the new standards. The projected annualized costs of compliance with the standards are just over $1 billion with 64% of these costs coming from implementing engineering controls. Table 1 provides OSHA's projected costs and benefits of the new crystalline silica standards.

|

Annualized Costs |

3% Discount Rate |

|

|

Engineering Controls (includes Abrasive Blasting) |

$661,456,736 |

|

|

Respirators |

$32,884,224 |

|

|

Exposure Assessment |

$96,241,339 |

|

|

Medical Surveillance |

$96,353,520 |

|

|

Familiarization and Training |

$95,935,731 |

|

|

Regulated Area Access Control |

$2,637,136 |

|

|

Written Exposure Control Plan |

$44,273,091 |

|

|

Total Annualized Costs (point estimate) |

$1,029,781,777 |

|

|

Annual Benefits |

Number of Cases Prevented |

3% Discount Rate |

|

Fatal Lung Cancers (midpoint estimate) |

124 |

|

|

Fatal Silicosis and other Nonmalignant Respiratory Diseases |

325 |

|

|

Fatal Renal Disease |

193 |

|

|

All Silica-Related Mortality |

642 |

$6,398,159,903 |

|

Silicosis Morbidity |

918 |

$2,228,753,312 |

|

Estimated Annual Benefits (midpoint estimate) |

$8,686,913,216 |

|

|

Estimated Net Benefits |

$7,657,131,439 |

Source: Department of Labor, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 81 Federal Register 16400, March 25, 2016.

Notes: Assumes a 3% discount rate. Projections using a 7% discount rate are available in the source document.

Opposition to the New Standards

After OSHA published the NPRM on the new crystalline silica standards on September 12, 2013, several groups representing employers expressed their opposition to the proposed changes. These groups argued that OSHA had significantly underestimated the projected costs of the new standards and that the declining rate of silicosis deaths indicated that stricter standards and lower PELs were not necessary.

Cost Projections

In a March 2015 report, the Construction Industry Safety Coalition (CISC), made up of 25 trade associations representing employers that may be affected by the new standards, estimates that the proposed new standards will cost employers $4.9 billion annually.3334 The CISC estimates annual direct compliance costs of $3.9 billion and indirect costs due to higher prices for building materials of more than $1 billion. The CISC's cost estimate is significantly higher than OSHA's cost estimate of just over $1 billion in the preamble to the Final Rule.

Benefit Projections

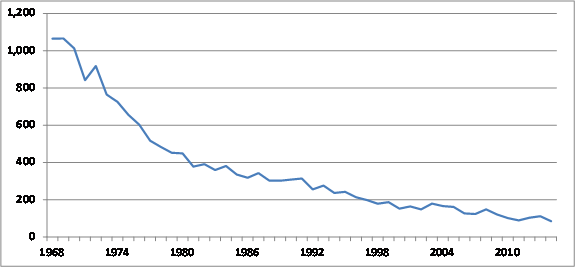

The Crystalline Silica Panel of the American Chemistry Council (ACC), composed of representatives from mining and mineral associations and industries, claims that evidence shows the current OSHA crystalline silica PELs are effective at reducing silica-related deaths and thus do not need to be changed.3435 The ACC claims that data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate a nearly 90% reduction in annual silicosis deaths between 1968 and 2010. The ACC attributes this reduction, in part, to the current PELs adopted in 1971.

The CDC states that the reduction in silicosis deaths in this period is likely due to two factors.3536 First, the higher numbers of deaths in the early period of the data may be capturing workers who were exposed to crystalline silica and contracted silicosis before the original OSHA PELs were implemented in 1971, mine safety regulations under the Coal Mine Safety and Health Act of 19693637 and the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977,3738 and a greater use of engineering controls and other measures to control crystalline silica exposure. Second, there has been a reduction in the number of workers in heavy industries, such as the mining industry, where silica exposure is prevalent.3839 In the preamble to its NPRM, OSHA calls these factors identified by the CDC "reasonable."3940

In addition, the ACC claims that better compliance with current PELs, not lower PELs, is the key to reducing silicosis deaths among workers. Annual silicosis mortality data are shown in Figure 1.

In public comments in response to the NPRM, the ACC, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Utility Contractors Association, and the National Federation of Independent Business all argued that OSHA's projection of the new standards preventing 162 annual deaths from silicosis and nonmalignant respiratory diseases in the NPRM exceeded the number of silicosis-related deaths reported in 2010 by the CDC and cited this as evidence that OSHA had overstated the benefits of the proposed standards.4041 In response to these objections, OSHA claims that commenters are making "apples and oranges" comparisons because the industry's objections focus on the number of deaths attributable to silicosis only, whereas OSHA's projections are for the number of deaths from silicosis and other nonmalignant respiratory diseases prevented by the new standards.4142

|

Figure 1. Annual Deaths Attributable to Silicosis in the United States 1968-2014 |

|

|

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Occupational Respiratory Mortality System (NORMS) National Database, http://webappa.cdc.gov/ords/norms-national.html.

|

Legislative Activity

In Section 115 of its FY2016 appropriations bill, S. 1695, the Senate Committee on Appropriations included a provision that would have prohibited OSHA from spending any appropriated funds to implement any change to the crystalline silica standards until

- a review is conducted, after the date of enactment, by a small business advocacy review (SBAR) panel (commonly referred to as a SBREFA panel) under the provisions of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) of 1996, and a report of this panel is submitted to OSHA;

4243 - OSHA commissions a study by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), and reports on the results of this study to the Senate Committees on Appropriations and Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions within one year of enactment of the legislation, to examine

- the epidemiological justification for reducing the crystalline silica PEL, "including consideration of the prevalence or lack of disease and mortality associated" with the current PELs;

- the ability to collect and measure samples of crystalline silica at levels below the proposed PELs and below the level of 25 µg/m3;

- the ability of regulated industries to comply with the proposed standards;

- the ability of various types of personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect workers from crystalline silica exposure; and

- the costs of various types of PPE compared with the costs of engineering controls and work practices.

S. 1695 would have appropriated $800,000 to OSHA to conduct the NAS study. S. 1695 was reported by the Senate Committee on Appropriations, but was not voted on by the Senate. The crystalline silica provisions were not included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, P.L. 114-113.

Legal Challenges

In the weeks after the Final Rule was published, legal challenges to the new crystalline silica standards,4344 in the form of petitions for review by the U.S. Court of Appeals, were initiated by groups representing employers, labor, and manufacturers.4445 The U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation has ruled that these petitions for review will be consolidated in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.45

Labor groups object to the medical surveillance provisions in the new standards. The National Building Trades Union (NBTU) wants medical surveillance to be required whenever workers are exposed to crystalline silica above the PEL, rather than after 30 days of exposure at or exceeding the 25 µg/m3 level or after 30 days of respirator use in construction.4647 Although the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) supports the new standards, it would like a provision in the new standards to require that workers be temporarily removed from jobs with exposure to crystalline silica upon a doctor's recommendation after medical surveillance similar to the medical removal provisions in OSHA's standard for exposure to cadmium.47

In addition to objections to the projected costs and benefits of the rule, employer and manufacturer groups, such as the Associated General Contractors of America and National Association of Manufacturers, argue that compliance with the new crystalline silica standards is not feasible given current technology and work practices.4849

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Department of Labor, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 81 Federal Register 16286, March 25, 2016. A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking was published on September 12, 2013 (78 Federal Register 56274). |

|

| 2. |

29 C.F.R. §1926.1153(c). |

|

| 3. |

For additional information on the hydraulic fracturing, see CRS Report R43148, An Overview of Unconventional Oil and Natural Gas: Resources and Federal Actions. |

|

| 4. |

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), "Workplace Safety and Health Topics: Silica," http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/silica/. |

|

| 5. |

NIOSH, Work Related Lung Disease Surveillance Report, October 1991, pp. 38-39, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/91-113/pdfs/91-113.pdf. |

|

| 6. |

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 81 Federal Register 16418, March 25, 2016. |

|

| 7. |

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts: Volume 100C, A Review of Human Carcinogens, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Lyon, France, 2012, pp. 355-406, http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100C/mono100C.pdf. |

|

| 8. |

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), National Toxicology Program, Report on Carcinogens: 13th Edition, October 2014, https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/annualreport/2015/glance/roc/index.html. |

|

| 9. |

NIOSH, "Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," NIOSH Hazard Review, April 2002, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-129/pdfs/2002-129.pdf. |

|

| 10. |

See for example Frederick Hoffman, "Mortality from Consumption in Dusty Trades," Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor, vol. 79 (November 1908), pp. 633-875; and General Report of the Miners' Phthisis Committee (Pretoria, South Africa): The Government Printing and Stationary Office of the Union of South Africa, 1916). For a complete history, see David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, "Consumption, Silicosis, and the Social Construction of Industrial Disease," Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, vol. 64 (1991), pp. 481-498. |

|

| 11. |

The exact number of deaths is unknown with some estimates exceeding 1,000 cases. The preamble to H.J.Res. 449 in the 74th Congress (1936) to authorize the Secretary of Labor to appoint a board of inquiry to investigate health conditions of public utility workers claims that 476 worker deaths and an additional 1,500 nonfatal cases of silicosis. An epidemiological study conducted in 1986 estimates more than 700 deaths related to the Hawk's Nest Tunnel construction. Martin Cherniak, The Hawk's Nest Incident: America's Worst Industrial Disaster, ed. 112-170 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986). |

|

| 12. |

42 U.S.C. §§7384r-7384s. |

|

| 13. |

29 U.S.C. §655(b)(5). |

|

| 14. |

Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Final Information Quality Bulletin for Peer Review, M-05-03, December 16, 2004, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/omb/memoranda/fy2005/m05-03.pdf. |

|

| 15. |

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 81 Federal Register 16381, March 25, 2016. |

|

| 16. |

29 C.F.R. §1910.1000 Table Z-3. |

|

| 17. |

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 78 Federal Register 56274, September 12, 2013. |

|

| 18. |

Ibid., p. 56275. |

|

| 19. |

A. E. Russell et al., The Health of Workers in Dusty Trades: II. Exposure to Siliceous Dust (Granite Industry), U.S. Public Health Service, Public Health Bulletin No. 187, July 1929, https://outside.vermont.gov/dept/VTLIB/Shared%20Documents/Health%20of%20workers%20in%20dusty%20trades.%202.%20Exposure%20to%20siliceous%20dust.pdf. |

|

| 20. |

Ibid., p. 205. |

|

| 21. |

U.S. Public Health Service, "The Health of Workers in Dusty Trades: Exposure of Workers to Siliceous Dust in the Granite Industry," Public Health Reports, vol. 44, no. 30 (July 26, 1929), pp. 1833-1835. |

|

| 22. |

29 U.S.C. 655(a). |

|

| 23. |

P.L. 74-846 with implementing regulations concerning exposure to crystalline silica at 41 C.F.R. §50-204.50. |

|

| 24. |

DOL, "Air Contaminants," 54 Federal Register 2332, January 19, 1989. |

|

| 25. |

Ibid., p. 2521. |

|

| 26. |

Ibid., p. 2332. |

|

| 27. |

DOL, "Air Contaminants," 57 Federal Register 26002, June 12, 1992. |

|

| 28. |

AFL-CIO v. OSHA, 965 F.2d 962 (1992). |

|

| 29. |

NIOSH, "Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Crystalline Silica," 1974, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/1970/75-120.html. |

|

| 30. |

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Crystalline Silica," 39 Federal Register 44771, December 27, 1974. |

|

| 31. |

The initial compliance date for construction of June 23, 2017, was extended by OSHA to September 23, 2017, via a memorandum published on the OSHA website on April 6, 2017, at https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=INTERPRETATIONS&p_id=31082. |

|

| 32. |

This policy was announced by OSHA in a memorandum published on the OSHA website at https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=INTERPRETATIONS&p_id=31292.

|

|

|

Environomics, Inc., Costs to the Construction Industry and Job Impacts from OSHA's Proposed Occupational Exposure Standards for Crystalline Silica, Construction Industry Safety Coalition, March 23, 2015, https://www.abc.org/Portals/1/Documents/CISC%20estimates%20for%20costs%20and%20jobs%20 |

||

|

American Chemistry Council, "Crystalline Silica Panel Statement on Proposed OSHA Silica Standard," news release, February 12, 2014, https://www.americanchemistry.com/Media/PressReleasesTranscripts/ACC-news-releases/Crystalline-Silica-Panel-Statement-on-Proposed-OSHA-Silica-Standard.html. |

||

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Silicosis Mortality, Prevention, and Control-United States, 1968-2002," Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Reports, vol. 54, no. 16 (April 29, 2005), pp. 401-405. |

||

|

P.L. 91-173. |

||

|

The CDC cites as an example the mining industry, which went from 989,400 employees in 1980 to 512,200 employees in 2002. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Silicosis Mortality, Prevention, and Control-United States, 1968-2002," Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Reports, vol. 54, no. 16 (April 29, 2005), p. 404. |

||

|

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 78 Federal Register 56298, September 12, 2013. |

||

|

DOL, "Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica," 81 Federal Register 16587-16588, March 25, 2016. |

||

|

Ibid., p. 16590. |

||

|

A Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) panel review was conducted on the proposed new crystalline silica standards in 2003. This provision would have required a new SBREFA panel review. For additional information on the small business advocacy review (SBAR) process, see CRS Report R43625, SBA Office of Advocacy: Overview, History, and Current Issues. |

||

|

Judicial review of OSHA standards is authorized by Section 6(f) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act [29 U.S.C. §655(f)] and must be initiated within 60 days of the promulgation of the standard. |

||

|

See, for example, N. Am.'s Bldg. Trades Unions v. OSHA, D.C. Cir., No. 16-1326, petition for review 4/1/16; AFL-CIO v. OSHA, 3rd Cir., No. 16-1774, petition for review 4/1/16; and State Chamber of Okla. v. OSHA, 10th Cir., No. 16-9518, petition for review 4/4/16. For additional information on judicial review of federal rulemaking, see CRS Report R41546, A Brief Overview of Rulemaking and Judicial Review. |

||

|

In re: Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Final Rule: Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica, 81 Fed. Reg. 16285, Issued on March 25, 2016, J.P.M.L. No. 139, April 13, 2016. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2112(a)(3), the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation selected the venue at random from all of the U.S. Court of Appeals Circuits in which petitions for review had been filed within 10 days of the promulgation of the standard. |

||

|

Bruce Rolfsen, "Silica Rule Prompts Rush of Court Petitions," Bloomberg BNA Occupational Safety and Health Daily, April 4, 2016. |

||

|

29 C.F.R. §1910.1027(l)(11). |

||

|

|