Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Changes from May 24, 2017 to October 24, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Paid Family Leave in the United States

- Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave

- State-Run Family Leave Insurance Programs

- Paid Family Leave in OECD Countries

- Recent Federal PFL Proposals

Figures

Summary

Paid family leave (PFL) refers to partially or fully compensated time away from work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs, such as the arrival of a new child or serious illness of a close family member. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA; P.L. 103-3) provides eligible workers with a federal entitlement to unpaid leave for a limited set of family caregiving needs, no federal law requires private-sector employers to provide paid leave of any kind. Currently, employees may access paid family leave if offered by an employer. In addition, workers in certain states may be eligible for state family leave insurance benefits that can provide some income support during periods of unpaid leave.

As defined in state law and federal proposals, family caregiving activities that are eligible for PFL or family leave insurance generally include caring for and bonding with a newly arrived child and attending to serious medical needs of certain close family members. Some permit leave for other reasons, but in practice, day-to-day needs for leave to attend to family matters (e.g., a school conference or lapse in child care coverage), minor illness, and preventativepreventive care are not included among "family leave" categories.

Employer provision of PFL in the private sector is voluntary. According to a national survey of employers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 13% of private-industry employees had access to PFL through their employers in March 20162017. The availability of PFL was more prevalent among professional and technical occupations and industries, high-paying occupations, full-time workers, and workers in large companies (as measured by number of employees). Recent announcements by several large companies indicate that access may be increasing among certain groups of workers.

In addition, some states have enacted legislation to create state paid family leave insurance (FLI) programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain caregiving activities. California, Rhode Island, and New Jersey currently operate FLI programs, which offer four to six weeks of benefits to eligible workers. Several states have enacted FLI programs, but they are not yet fully implemented and paying benefits. The New York program will begin implementation in 2018. The District of Columbia FLI legislation took effect in April 2017, with benefits payable starting in 2020. Implementation of Washington State's program is delayed until a financing mechanism is identified.

Many advanced-economy countries entitle workers to some form of paid family leave. Whereas some provide leave to employees engaged in family caregiving (e.g., of parents, spouses, and other family members), many emphasize leave for new parents, mothers in particular. The United States is the only OECDOrganization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member to not offer paid leave to new mothers.

The 115th Congress is considering proposals to expand national access to paid family leave. Key bills include the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act; S. 337/H.R. 947), which proposes to create a national wage insurance program for persons engaged in family caregiving activities or who take leave for their own serious health condition, and the Strong Families Act (S. 344, S. 1716), which would provide tax incentives to employers to voluntarily offer paid family and medical leave to employees.

Introduction

Paid family leave (PFL) refers to partially or fully compensated time away from work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs, such as the arrival of a new child or serious illness of a close family member. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA; P.L. 103-3) provides eligible workersworkers with a federal entitlement to unpaid leave for a limited set of family caregiving needs, no federal law requires private-sector employers to provide paid leave of any kind.1

Currently, employees may access paid family leavePFL if offered by an employer. In addition, some states have created family leave insurance (FLI) programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain (state-identified) family caregiving activities. In these states, workers can access paid family leavePFL by combining an entitlement to unpaid leave with state-provided insurance benefits. Congressional proposals to expand national access to paid family leave tend to expand upon these existing mechanisms. The Strong Families Act (S. 344, S. 1716) seeks to expand employer-provided paid family leavePFL through new tax incentives, and—similar to the state insurance approach—the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act; S. 337/H.R. 947) proposes to create a national wage insurance program that pays cash benefits to eligible individuals engaged in certain caregiving activities, including for the worker's own serious health condition.

Congressional Members who support increased access to paid leave generally cite as their motivation the significant and growing difficulties some workers face when balancing work and family responsibilities, and the financial challenges faced by many working families that put unpaid leave out of reach. In general, expected benefits of expanded access to paid family leavePFL include stronger labor force attachment for family caregivers and greater income stability for their families, and improvements to worker morale, job tenure, and other productivity-related factors. Potential costs include the financing of payments made to workers on leave, other expenses related to periods of leave (e.g., hiring a temporary replacement or productivity losses related to an absence), and administrative costs. The magnitude and distributions of costs and benefits will depend on how the policy is implemented, including the size and duration of benefits, how benefits are financed, and other policy factors.

This report provides an overview of paid family leave in the United States, summarizes state-level family leave insurance programs, notes paid family leavePFL policies in other advanced-economy countries, and notes recent federal proposals to increase access to paid family leave.

Paid Family Leave in the United States

Throughout their careers, many workers encounter a variety of family caregiving obligations that conflict with work time. Some of these are broadly experienced by working families but tend to be short in duration, such as episodic child care conflicts, school meetings and events, routine medical appointments, and minor illness of an immediate family member. Others are more significant in terms of their impact on families and the amount of leave needed, but occur less frequently in the general worker population, such as the arrival of a new child or a serious medical condition that requires inpatient care or continuing treatment. Although all these needs for leave may be consequential for working families, the term "family leave" is generally used to describe the latter, more significant, group of needs.

As defined in state law and federal proposals, family caregiving activities that are eligible for paid family leavePFL or leave insurance benefits generally include caring for and bonding with a newly arrived child and attending to the serious medical needs of certain close family members; some also allow leave or benefits for workers with certain military family needs. In practice, day-to-day needs for leave to attend to family matters (e.g., a school conference or lapse in child care coverage), minor illness (e.g., common cold), or preventativepreventive care are not included among family leave categories.2

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave

Employer provision of paid family leave (PFL)PFL in the private sector is voluntary. According to a national survey of employers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 13% of private-industry employees had access to PFL (separate from other leave categories) through their employer in March 20162017.3 These statistics, displayed in Table 1, further show that PFL was more prevalent among professional and technical occupations and industries, high-paying occupations, full-time workers, and workers in large companies (as measured by number of employees). Recent announcements by several large companies suggest that access may be increasing among certain groups of workers. Among new company policies announced in recent years, some emphasize parental leave (i.e., leave taken by mothers and fathers in connection with the arrival of a new child), and others offer broader uses of family leave.4

Table 1. Share of Private Industry Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave, March 2016

|

Category |

Percentage of Workers |

|

|

All Workers |

13% |

|

|

By Occupation |

||

|

Management, professional, and related |

24% |

|

|

Service |

7% |

|

|

Sales and office |

13% |

|

|

Natural resources, construction, and maintenance |

|

|

|

Production, transportation, and material moving |

6% |

|

|

By Industry |

||

|

Construction |

5% |

|

|

Manufacturing |

10% |

|

|

Trade, Transportation, and Utilities |

7% |

|

|

Information |

|

|

|

Financial Activities |

31% |

|

|

Professional and Technical Services |

27% |

|

|

Administrative and Waste Services |

6% |

|

|

Education and Health Services |

|

|

|

Leisure and Hospitality |

6% |

|

|

Other Services |

|

|

|

By Average Occupational-Wage Distribution |

||

|

Bottom 25% |

6% |

|

|

Second 25% |

11% |

|

|

Third 25% |

14% |

|

|

Top 25% |

24% |

|

|

By Hours of Work Status |

||

|

Full-time |

16% |

|

|

Part-time |

5% |

|

|

By Establishment Size |

||

|

1 to 99 employees |

|

|

|

100 to 499 employees |

|

|

|

500 or more employees |

23% |

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 20162017 Employee Benefits Survey, March 20162017, Table 32, http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/20162017/ownership/private/table32a.htm.

Notes: The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave "granted to an employee to care for a family member and includes paid maternity and paternity leave. The leave may be available to care for a newborn child, an adopted child, a sick child, or a sick adult relative. Paid family leave is given in addition to any sick leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee." Employees may be able to use other forms of paid leave (e.g., vacation time), or a combination of them, to provide care to a family member.

A 2017 study by the Pew Research Center (Pew) examined U.S. perceptions of and experiences with paid family and medical leave; its results provide insights into the need for such leave among U.S. workers and its availability for those who need it.5 Pew reports, for example, that 27% of persons who were employed for pay between November 2014 and November 2016 took leave (paid and unpaid) for family caregiving reasons or their own serious health condition over that time period, and another 16% had a need for such leave but were not able to take it.6 Among workers who were able to use leave, 47% received full pay, 36% received no pay, and 16% received partial pay. Consistent with BLS data, the Pew study indicates that lower-paid workers have less access to paid leave; among leave takers, 62% of workers in households with less than $30,000 in annual earnings reported they received no pay during leave, whereas this figure was 26% among those with annual household incomes at or above $75,000.

State-Run Family Leave Insurance Programs

Some states have enacted legislation to create state paid family leave insurance (FLI)FLI programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain caregiving activities. Three states—California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—have active programs. Three additional programs—those in New York, the District of Columbia, and Washington State—await implementation.7

Table 2 summarizes key provisions of state FLI laws and shows the following:

- The maximum weeks of benefits available to workers and wage replacement rates vary across states. Existing state FLI programs offer between 4 weeks (Rhode Island) and 6 weeks (California and New Jersey) of benefits. When its plan is implemented, the District of Columbia will offer 8 weeks of paid family leave in 2020, and Washington State will offer 12 weeks of paid family leave in the same year. New York will offer 12 weeks of benefits when its plan is fully implemented in 2021.

- Program eligibility typically involves in-state employment of a minimum duration, minimum earnings in covered employment, or contributions to the insurance funds.

- All state

family leave insurance programsFLI programs currently in operation are financed entirely by employee payroll tax receipts; however, when implemented, the DC program is set to be financed by employers. Washington State's program will be jointly financed by employers and employees.

- Some FLI programs, like those in Rhode Island and New York, provide job protection directly to workers who receive FLI benefits, meaning that employers must allow a worker to return to his or her job after leave has ended. Workers in other states may receive job protection if they are entitled to leave under federal or state family and medical leave laws, and coordinate such job-protected leave and FLI benefits.

|

State |

Year |

Qualifying Eventsa |

Benefit Formula |

Maximum Benefit in 2017 |

Weeks of Benefits |

Eligibility |

Financingb |

Job Protection |

|||||||

|

California |

2004 |

Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Serious health condition of a close family member.c |

Benefits are paid weekly and are calculated as a percentage of the worker's recent weekly earnings (55% in 2017), up to a maximum amount determined annually; minimum benefits are $50 per week. For a four-year period starting on January 1, 2018, wage replacement rates will be based on whether the worker's wages are at or above or below one-third of the state average wage, with workers with lower earnings receiving higher replacement rates. |

$1,173/week |

Six weeks for family care. |

Worker has earned $300 in wages in California that were subject to the insurance tax over the worker's "base period."d |

Payroll tax on employees. |

No |

|||||||

|

District of Columbia The DC Universal Paid Family Leave Act requires the mayor to start paying family leave benefits by July 1, 2020. Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Needs related to the military deployment of a close family member. Worker's own serious medical condition. For workers with average weekly wages less than or equal to 150% of 40 hours compensated at the DC minimum wage (i.e., "DC minimum weekly wage"), benefits are 90% of the worker's average weekly wage. For workers with average weekly wages above this threshold, benefits are 150% of the DC minimum weekly wage plus 50% of the average amount earned above the DC minimum weekly wage, up to a maximum amount. N/A Eight weeks, of which up to eight weeks may be for parental leave, up to six weeks for family leave, and up to two weeks for the worker's own medical leave. In general, at least 50% of work occurs in the District of Columbia for a covered DC-based employer. Has been a covered employee for at least one week during the 52 calendar weeks preceding the qualifying event for leave. Payroll tax on covered employers, which does not include the federal government. No |

2009 |

Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Serious health condition of a close family member.c |

Approximately 67% of average weekly wage (based on earnings in the eight calendar weeks immediately prior to the week in which the leave begins), up to a maximum amount. |

$633/week |

|

At least 20 calendar weeks in which the worker has covered New Jersey earnings of $168, or the worker has earned at least $8,400 in covered New Jersey employment in the 52 calendar weeks preceding the week in which leave began. |

Payroll tax on employees. |

No |

|||||||

|

New York |

Scheduled to phase in starting in 2018; fully implemented in 2021. |

Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Serious health condition of a close family member.c |

Benefits are calculated as a percentage of the employee's average weekly wage, up to a maximum amount determined by the product of the replacement rate in a given year and the New York average weekly wage. Replacement rates are scheduled to be 50% in 2018, 55% in 2019, 60% in 2020, and 67% in 2021. |

N/A |

8 weeks of family leave in 2018, 10 weeks in 2019 and 2020, and 12 weeks starting in 2021. |

Full-time employment for 26 weeks or 175 days of part-time employment. |

Payroll tax on employees. |

Yes |

|||||||

|

Rhode Island |

2014 |

Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Serious health condition of a close family member.c |

4.62% of wages received in the highest quarter of the worker's base period (i.e., approximately 60% of weekly earnings), up to a maximum.d The minimum weekly benefit is $89. In some cases the worker may receive a dependency allowance. |

$817/week |

|

In general, to be eligible a worker must have earned wages in Rhode Island, paid into the insurance fund, and received at least $11,520 in the base period; a separate set of criteria may be applied to persons earning less than $11,520.d |

Payroll tax on employees. |

Yes |

|||||||

|

Washington |

Not implemented due to lack of a financing mechanism. |

Arrival of a new child by birth or adoption. |

$250 per week if regularly working 35+ hours per week. Benefits pro-rated for persons who regularly worked less than 35 hours prior to leave. |

N/A |

Five weeks for parental leave. |

|

None |

Yes, under limited conditions. |

|||||||

|

District of Columbia |

|

Arrival of a new child by birth, adoption, or foster care. Serious health condition of a close family member. Needs related to the military deployment of a close family member. Worker's own serious medical condition. |

|

N/A |

Eight weeks, of which up to eight weeks may be for parental leave, up to six weeks for family leave, and up to two weeks for the worker's own medical leave. |

In general, at least 50% of work occurs in the District of Columbia for a covered DC-based employer. Has been a covered employee for at least one week during the 52 calendar weeks preceding the qualifying event for leave. |

Payroll tax on covered employers, which does not include the federal government. |

No Benefits may be extended to 18 weeks (i.e., 2 additional weeks of medical leave) if an employee's pregnancy results in incapacity. Worked at least 820 hours of employment during the qualifying period.dFederal employees are not covered. Payroll tax paid jointly by employees and employers, if the employer employs at least 50 workers. Otherwise, funded by employees. Yes, under limited conditions. |

Sources: California: California Unemployment Insurance Code §§3300-3306 and program information from http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/Paid_Family_Leave.htm. New Jersey: N.J. Stat. Ann. §43:21-25-56 and program information from http://lwd.dol.state.nj.us/labor/fli/fliindex.html. New York: New York Workers' Compensation §§200-242 and program information from https://www.ny.gov/programs/new-york-state-paid-family-leave. Rhode Island: Rhode Island General Laws §§28-41-34-35, and program information from http://www.dlt.ri.gov/tdi/. Washington: Revised Code of Washington Title 49 Chapter 49.86Substitute Senate Bill 5975, State of Washington, 65 Legislature, 2017, 3rd Special Session from http://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=5975&Year=2017. District of Columbia: Law L21-0264 published in DC Register, vol. 64, p. 3985.

a.

California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island also provide temporary disability benefits to workers through a state disability insurance program, and New York requires covered employers to provide temporary disability benefits to workers who are unable to work due to disability.

b.

In some states, family leave insurance benefits and disability insurance (i.e., for a worker's own medical condition) are financed separately. In these cases, the information in this column describes financing mechanisms for family leave insurance alone.

c.

Most states provide FLI benefits to workers who provide care to a family member with a serious health condition. The set of family members generally includes a child, parent, spouse or domestic partner, and grandparent; some states provide benefits for the care of other relatives such as grandchildren and siblings.

d.

For California, Rhode Island, and Washington, the "base period" or "qualifying period" is the first four of the last five completed quarters that precede the insurance claim. For example, a claim filed on February 6, 2017, is within the calendar quarter that begins on January 1, 2017 (i.e., the first calendar quarter). The base period for that claim is the four-quarter period (i.e., 12-month period) that starts on October 1, 2015.

|

A relatively small literature examines U.S. workers' access to and use of paid family leave and related labor market and social outcomes, with an emphasis on parental leave (i.e., leave related to the birth and care of new children). For the United States, studies of the state family leave insurance programs (see the "State-Run Family Leave Insurance Programs" section of this report) form an important branch of research. The broad coverage of these programs and availability of administrative data provide methodological advantages over studies of workers with employer-provided leave.8 California launched the first state family leave insurance program in the country in 2004, and is the most studied. Research findings indicate that greater access to paid family leave (i.e., through the California program) resulted in greater leave-taking among workers with new children, with some evidence that the increase in leave-taking was particularly pronounced among women who are less educated, unmarried, or nonwhite.9 Although the program was associated with greater leave-taking—in terms of incidence and duration of leave—for mothers and fathers, there is some indication that workers are not availing themselves of the full six-week entitlement offered by the California program, suggesting that barriers to leave-taking remain (e.g., financial constraints, work pressures).10 Maya Rossin-Slater reviews the broader literature on the impacts of maternity and paid family leave in the United States, Europe, and other high-income countries.11 She notes the wide variation in paid leave policies around the globe (see "Paid Family Leave in OECD Countries" section of this report), but nonetheless offers four general observations: (1) greater access to paid leave for new parents increases leave-taking; (2) access to leave can improve labor force attachment among new mothers, but leave entitlements in excess of one year can have the opposite effect (i.e., long separations can weaken labor force attachment among mothers); (3) access to leave can improve children's well-being, but extending the length of existing entitlements does not appear to further improve child outcomes; and (4) a limited literature on U.S. state-level family leave insurance programs does not reveal notable impacts (positive or negative) of these programs on employers, but further research on employers' experiences is needed. |

Paid Family Leave in OECD Countries

Many advanced-economy countries entitle workers to some form of paid family leave. Whereas some provide leave to employees engaged in family caregiving (e.g., of parents, spouse, and other family members), many emphasize leave for new parents, mothers in particular.

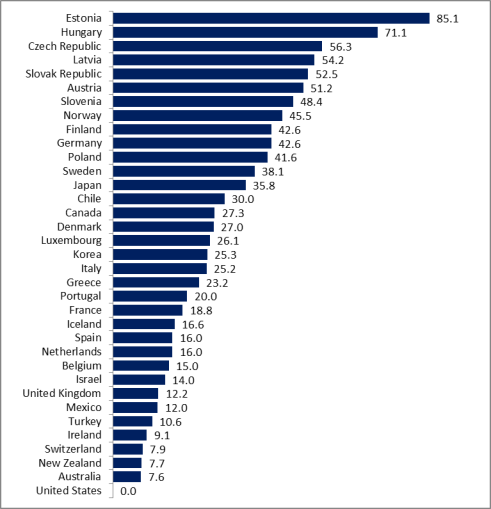

As of 20152016, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) family leave database counts 34 of its 35 members as providing some paid parental leave (i.e., to care for children) and maternity leave, with wide variation in the number of weeks and rate of wage replacement across countries. This is shown in Figure 1, which plots the OECD's estimates of weeks of full-wage equivalent leave available to mothers. Weeks of full-wage equivalent leave are calculated as the number of weeks of leave available multiplied by the average wage payment rate. For example, a country that offers 12 weeks of leave at 50% pay would be said to offer 6 full-wage equivalent weeks of leave (i.e., 12 weeks x 50% = 6 weeks).

|

Figure 1. Average Full-Wage Equivalent Weeks of Paid Leave Available to OECD Member Countries' Leave Provisions as of April |

|

|

Source: OECD, Family Database, Indicator Table PF2.1, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm. Notes: Leave available to mothers includes maternity leave and leave provided to care for children. Average full-wage equivalent weeks are calculated by the OECD as the product of the number of weeks of leave and "average payment rate," which describes the share of previous earnings replaced over the period of paid leave for "a person earning 100% of average national (2014) earnings." While federal law in the United States does not provide paid parental leave for private sector workers, some employers provide such leave voluntarily and some states have programs that provide wage insurance to workers on leave for selected family reasons; see section "Paid Family Leave in the United States" of this report for additional information.

A smaller share (27 of 35) of OECD countries provides paid leave to new fathers. In some cases, fathers are entitled to less than a week of leave, often at full pay (e.g., Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands), whereas others provide several weeks of full or partial pay (e.g., Portugal provides five weeks at full pay, and the United Kingdom provides 2 weeks at an average payment rate of 20.2%). Some countries provide a separate entitlement to fathers for child caregiving purposes. This type of parental leave can be an individual entitlement for fathers or a family entitlement that can be drawn from by both parents. In the latter case, some countries (e.g., Japan, Luxembourg, and Finland) set aside a portion of the family entitlement for fathers' use, with the goal of encouraging fathers' participation in caregiving. Figure 2 summarizes paid leave entitlements reserved for fathers in OECD countries in 2016; it plots the OECD's estimates of weeks of full-wage equivalent paternity leave and parental leave reserved for fathers.

OECD Member Countries' Leave Provisions as of April 2016 |

The OECD examined the availability of family caregiver leave among its member countries in 2011 and found that of the 25 countries for which it could identify information, 14 had polices providing paid leave to workers with ill or dying family members; these are summarized in Table 3.12 Qualifying needs for leave, leave entitlement durations, benefit amounts, and eligibility conditions varied considerably across the countries included in the OECD study.

|

Country |

Paid Caregiving Leave |

|

Australia |

Up to 10 days of leave for full-time employees to care for a sick family or household member. |

|

Belgium |

Two months of leave to provide palliative care to a terminally ill parent. Up to three months of leave to care for a family or household member who needs medical care. |

|

Canada |

Up to six weeks of income support, provided though the Employment Insurance Compassionate Care Benefit, for certain workers providing care to "a family member who is gravely ill and at the risk of dying." |

|

Denmark |

|

|

Finland |

100 to 360 days of "alternation leave" (i.e., a career break) for workers with significant work histories.a The absent employee's job must be filled on a fixed-term basis by an unemployed person. |

|

France |

21 days of leave to care for a close family member or household member who is terminally ill. |

|

Japan |

Up to 93 days (per ill family member) to provide care to certain close family members; compensation is conditioned on the worker being insured for at least 12 months by the public employment insurance service. |

|

Luxembourg |

Up to 5 days of leave when a spouse, parent, or child is terminally ill. |

|

Netherlands |

Up to 10 days of leave to care for a sick family member. |

|

Norway |

Up to 30 days (provided under two programs) for caregiving. |

|

Poland |

Up to 60 days of leave. |

|

Slovenia |

Up to 7 days to provide care to a coresident child or spouse, with additional days granted for severe illness. |

|

Spain |

Up to 3 days of leave to provide care to an ill family member. |

|

Sweden |

Up to 100 days to provide care to a family member of working age with a terminal illness. |

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), "Chapter 4: Policies to Support Family Carers" in Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long Term Care, OECD Health Policy Studies Series, 2011, http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/help-wanted-9789264097759-en.htm.

Notes: The table presents policies that the OECD was able to identify for a 2011 study of long-term care. An entitlement to paid leave is subject to country-specific eligibility conditions, and leave may not be fully compensated.

a.

The legislated right to alternation leave was updated after the 2011 OECD publication. The duration of leave was extended from 90-359 days to 100-369360 days, and work history requirements were extended from 10 years to 20 years. For more information, see http://tem.fi/en/job-alternation-compensation.

Recent Federal PFL Proposals

The overarching goal of the PFL proposals that have been considered by the 115th Congress is to increase access to leave by reducing the costs associated with taking leave. In general, two main approaches are proposed. The first is the creationestablishment of a national paid family leave insurance program (e.g., S. 337/H.R. 947); the second is to provide tax credits to employers that provide paid family leave to their employees (e.g., S. 344).13

In addition, the President's fiscal year 2018, such as that proposed in the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (S. 337/H.R. 947), would provide cash benefits to eligible individuals who are engaged in certain caregiving activities, potentially making the use of unpaid leave (e.g., as provided by FMLA or voluntarily by employers) affordable for some workers. A second approach, such as that proposed in the Strong Families Act (S. 1716 and an earlier, related bill of the same name, S. 344), aims to expand employer-provided leave by allowing employers to claim tax credits for a portion of wages paid to employees taking paid family leave; this approach potentially increases access to PFL for workers while reducing the costs to employers of providing the leave.13

In addition, the President's FY2018 budget proposes to provide six weeks of financial support to new parents through state unemployment compensation (UC) programs.14 A similar approach was taken in 2000 by the Clinton Administration, which—via Department of Labor regulations—allowed states to use their UC programs to provide UC benefits to parents who take unpaid leave under the FMLA, other approved unpaid leave, or otherwise take time off from employment after the birth or adoption of a child. The Birth and Adoption Unemployment Compensation rule took effect in August 2000, and was later removed from federal regulations in November 2003.15

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

Some Members have introduced proposals to increase access to other types of leave as well, such as paid sick leave. Proposed paid sick leave entitlements are relatively short in duration—typically 4 hours per 30 hours of work, up to a maximum of 56 hours per year—and could be used for a broader assortment of medical needs than are typically included in family and medical leave proposals. |

| 3. |

The |

| 4. |

Examples of companies that offer paid leave benefits for broader purposes include Facebook, which announced in 2017 that it would extend paid leave to those providing care to a sick family member (three days for short-term illness and six weeks for serious illness) and to bereavement (20 days for an immediate family member and 10 days for extended family), and Deloitte, which announced in September 2016 that it would offer its employees up to 16 weeks of paid leave for family caregiving. Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg announced Facebook's new leave policy at https://www.facebook.com/sheryl/posts/10158115250050177; Deloitte announced its new policy at https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/press-releases/deloitte-announces-sixteen-weeks-of-fully-paid-family-leave-time-for-caregiving.html. |

| 5. |

Juliana Horowitz, Kim Parker, Nikki Graf, and Gretchen Livingston, Americans Widely Support Paid Family and Medical Leave, but Differ Over Specific Policies, Pew Research Center, March 2017, http://pewresearch.org; hereinafter "Horowitz et al., 2017 |

| 6. |

These survey results are summarized on page 52 of Horowitz et al., 2017. For workers who took family and medical leave and those who had such a need but were unable to take leave, the areas of greatest demand were for leave to care for the worker's own serious health condition and for leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition. The report does not contain the questionnaire used to pose these questions, and so there is some uncertainty about how respondents interpret the term "serious health condition," which at least in the FMLA has a specific meaning (i.e., a health condition that requires inpatient care or continuing treatment by a health care provider). |

| 7. |

The New York program is scheduled to phase in starting in 2018 and be fully implemented by 2021. The District of Columbia paid family leave legislation took effect on April 7, 2017; the act requires the mayor to start paying family leave benefits by July 1, 2020. Washington State |

| 8. |

As noted in the "Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave" section of this report, employer-provided leave is concentrated among higher-paying occupations, larger firms, and certain industries. This lack of broad coverage creates challenges for researchers trying to disentangle, for example, the effects of leave-taking on employment and earnings outcomes from the effects of holding a high-paying professional job on the same outcomes. |

| 9. |

Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel, "The Effect of California's Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers' Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes," Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 32, no. 2 (2013), pp. 224-245. |

| 10. |

Charles Baum and Christopher Ruhm, The Effects of Paid Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes, NBER Working Paper 19741, 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19741; Ann Bartel, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, Jenna Stearns, and Jane Waldfogel, Paid Family Leave, Fathers' Leave-Taking, and Leave-Sharing in Dual-Earner Households, NBER Working Paper no. 21747, 2015, http://www.nber.org/papers/w21747. |

| 11. |

Maya Rossin-Slater, Maternity and Family Leave Policy, NBER Working Paper no. 23069, 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w23069. |

| 12. |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), "Chapter 4: Policies to Support Family Carers," in Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long Term Care, OECD Health Policy Studies Series, 2011, http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/help-wanted-9789264097759-en.htm. |

| 13. |

A bill proposing a new paid parental leave entitlement for federal workers (S. 362/H.R. 1022) has also been introduced. S. 1716 and S. 344 are closely similar, but S. 1716 allows the percentage of wages that can be claimed as a tax credit to vary according to the rate at which employers compensate employees who use family leave, and it removes a $3,000 maximum credit (per employee, per year) that may be claimed by an employer. |

| 14. |

Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf and Department of Labor, FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification, Employment and Training Administration, State Unemployment Insurance and Employment Service Operations, May 23, 2017, https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/CBJ-2018-V1-07.pdf. |

| 15. |

Information on unemployment compensation and family leave, and the Clinton Administration Birth and Adoption Unemployment Compensation Regulation is in CRS In Focus IF10643, Unemployment Compensation (UC) and Family Leave, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |