Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2013-FY2022 Estimates and Issues

Changes from April 25, 2017 to April 30, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018 Estimates and Issues

Contents

- Introduction

- Estimates

- FY2016

- Overview of Decade (

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018) - Changes in Estimates in Current and Constant Dollars

- Agency Shares of Deferred Maintenance in Current and Constant Dollars

- Issues in Analyzing Deferred Maintenance

- Methodology

- Funding

- Assets

- Economic Conditions

Figures

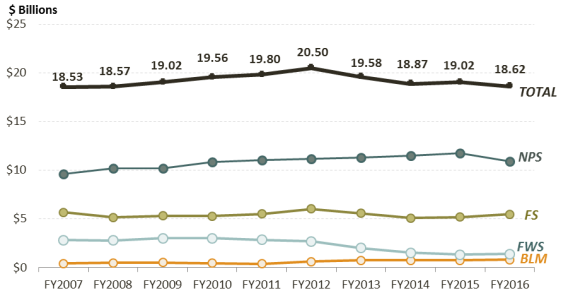

- Figure 1. Change in Deferred Maintenance by Agency in Current Dollars,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

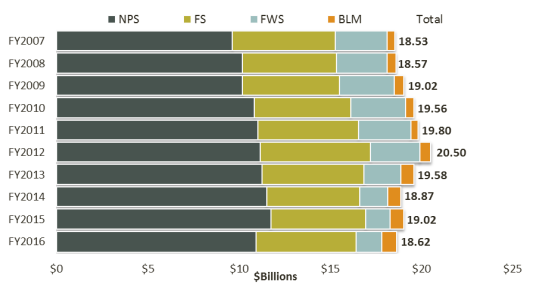

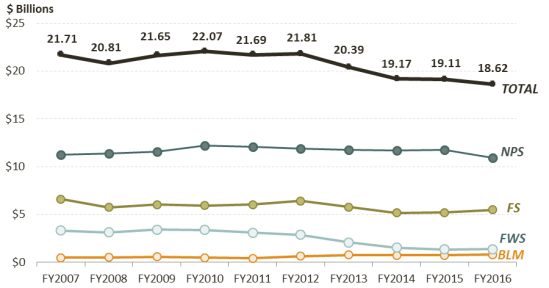

- Figure 2. Change in Deferred Maintenance by Agency in 2018 Constant Dollars,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

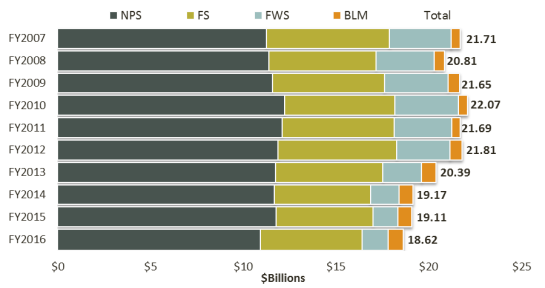

- Figure 3. Deferred Maintenance Total by Agency in Current Dollars,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 4. Deferred Maintenance Total by Agency in Constant Dollars,

FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018

Summary

Each of the four major federal land management agencies maintains tens of thousands of diverse assets, including roads, bridges, buildings, and water management structures. These agencies are the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), National Park Service (NPS), and Forest Service (FS). Congress and the Administration continue to focus on the agencies' deferred maintenance and repair of these assets—in essence, the cost of any maintenance or repair that was not done when it should have been or was scheduled to be done. Deferred maintenance and repair is often called the maintenance backlog.

In FY2016FY2018, the most recent year for which these estimates are available, the four agencies had combined deferred maintenance estimated at $18.6219.38 billion. This figure includes $10.9311.92 billion (5962%) in deferred maintenance for NPS, $5.4920 billion (2927%) for FS, $1.4030 billion (87%) for FWS, and $0.8196 billion (45%) for BLM. The estimates reflect project costs but exclude indirect costs.

Over the past decade (FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018), the total deferred maintenance for the four agencies rose and then fell,fluctuated, peaking in FY2012 and ending the decade relatively flat in current dollars. It increased overall by $0.0936 billion, from $18.5319.02 billion to $18.6219.38 billion, or 0.52%. Both the BLM and NPS estimates increased, whereas the FWS and FS estimates decreased. By contrast, in constant dollars, the total deferred maintenance estimate for the four agencies decreased from FY2007 to FY2016 by $3.09FY2009 to FY2018 by $3.61 billion, from $21.7122.99 billion to $18.6219.38 billion, or 1416%. The BLM estimate increased, whereas estimates for the other three agencies decreased.

In each fiscal year, NPS had the largest portion of the total deferred maintenance, considerably more than any of the other three agencies. FS consistently had the second-largest share, followed by FWS and then BLM. Throughout the past decade, the asset class that included roads comprised the largest portion of the four-agency combined deferred maintenance.

Congressional debate has focused on varied issues, including the level and sources of funds needed to reduce deferred maintenance, whether agencies are using existing funding efficiently, how to balance the maintenance of existing infrastructure with the acquisition of new assets, whether disposal of assets is desirable given limited funding, and the priority of maintaining infrastructure relative to other government functions.

Some question why deferred maintenance estimates have fluctuated over time. These fluctuations are likely the result of many factors, among them the following:

- Agencies have refined methods of defining and quantifying the maintenance needs of their assets.

- Levels of funding for maintenance, including funding to address the maintenance backlog, vary from year to year. Economic conditions, including costs of services and products, also fluctuate.

- The asset portfolios of the agencies change, with acquisitions and disposals affecting the number, type, size, age, and location of agency assets.

- Economic conditions, including costs of services and products, fluctuate.

The extent to which these and other factors affected changes in each agency's maintenance backlog over the past decade is not entirely clear. In some cases, comprehensive information is not readily available or has not been examined.

Introduction

TheEach of the four major federal land management agencies— has maintenance responsibility for tens of thousands of diverse assets in dispersed locations. These agencies are the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS), all within the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the Forest Service (FS) within the Department of Agriculture—have maintenance responsibility for more than 300,000 diverse assets in dispersed locations. These agencies maintain assets to preserve their functioning and to repair and replace components as needed.1

The infrastructure needs of the federal land management agencies have been a subject of significant federal and public attention for many years. Congressional and administrative attention has focused on deferred maintenance and repairs, defined as "maintenance and repairs that were not performed when they should have been or were scheduled to be and which are put off or delayed for a future period."2 "Maintenance and repair" include a variety of activities intended to preserve assets in an acceptable condition, including activities such as preventive maintenance and replacement of parts, systems, and components. These terms do not include activities intended to expand the capacity of assets to allow them to serve different purposes or significantly increased needs.3 Deferred maintenance and repairs often are called the maintenance backlog. The agencies assert that continuing to defer the maintenance and repair of facilities accelerates the rate of these facilities' deterioration, increases their repair costs, and decreases their value. Debate has focused on varied issues, including the level of funds needed to reduce deferred maintenance, whether agencies are using existing funding efficiently, the priority of deferred maintenance relative to regular maintenance, and whether additional sources of funds should be directed to maintenance. Other issues include how to balance the maintenance of existing infrastructure with the acquisition of new assets, whether disposal of assets is desirable given limited funding, and how much to prioritize maintaining infrastructure relative to other government functions.

Another issue relates to the dollar amount of deferred maintenance and the reasons for fluctuations over time. This report focuses on these issues. It first provides agency deferred maintenance estimates for FY2016FY2018, the most recent fiscal year for which this information is available. It also discusses changes in deferred maintenance over the past decade (FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018) and then identifies some of the factors that likely contributed to these changes.

Estimates

The agencies typically identify deferred maintenance through periodic condition assessments of facilities.34 FS currently reports an annual deferred maintenance dollar total composed of estimates for 1310 classes of assets. These classes include roads, buildings, trails, fencesbridges, and water systems, among others.45 DOI currently reports annual deferred maintenance composed of estimates for four broad categories of assets: (1) roads, bridges, and trails; (2) irrigation, dams, and other water structures; (3) buildings; and (4) other structures. The "other structures" category includes a variety of assets (e.g., recreation sites and hatcheries).

For each of the 10 years covered by this report, FS has reported the amount of deferred maintenance as a single figure. DOI agencies began reporting deferred maintenance as a single figure in FY2015.56 In prior years, DOI agencies reported estimates as a range. For FY2014, for instance, the range had an "accuracy level of minus 15 percent to plus 25 percent of initial estimate."67 According to DOI, a range had been used because "[d]uedue to the scope, nature, and variety of the assets entrusted to DOI, as well as the nature of deferred maintenance itself, exact estimates are very difficult to determine."78

FS estimates of deferred maintenance included in this report generally are taken from the agency's annual budget justifications to Congress.89 The DOI Budget Office provided the Congressional Research Service (CRS) with a deferred maintenance range for each DOI agency for each fiscal year from FY2007FY2009 to FY2014. From these ranges, CRS calculated mid-range figures. For instance, DOI estimated NPS deferred maintenance for FY2014 at between $9.31 billion and $13.70 billion. The CRS-calculated mid-range figure is $11.50 billion.910 This report reflects CRS's mid-range calculations for FY2007FY2009-FY2014 to facilitate comparison with FS estimates.1011 Since FY2015, the DOI Budget Office has provided CRS with a single estimate for each DOI agency, and those figures are used in this report. They represent deferred maintenance as of the end of the fiscal year (i.e., September 30).11

FY2016

The four agencies had a combined FY2016 deferred maintenance estimated at $18.62 billion.1212 For both FS and DOI agencies, the deferred maintenance estimates generally reflect project costs.13 Finally, totals shown in the body and in tables of this report may not add to 100% due to rounding.

FY2018

The four agencies had combined FY2018 deferred maintenance estimated at $19.38 billion.14 The agencies had widely varying shares of the total. NPS had the largest portion, 5962%, based on an estimate of $10.9311.92 billion.1315 The FS share was 2927% of the total, with an estimated deferred maintenance of $5.4920 billion. The FWS portion was 87%, reflecting the agency's deferred maintenance of $1.4030 billion. BLM had the smallest share, 45%, based on a backlog estimate of $0.8196 billion.

Each agency's deferred maintenance estimate for FY2016FY2018 consisted of various components. For FS, the single largest asset class was roads, which comprised 5961% of the FY2016FY2018 total of $5.4920 billion. The next largest asset class was buildings, which represented 2224% of the FS FY2016FY2018 total. The next two largest asset classes were trails (5%), fences (5%), and bridges (4%). Eightand bridges, each with 5%. Six other asset classes made up the remaining 6%.

For NPS, the largest asset category was roads, bridges, and trails, which comprised 5857% of the FY2016FY2018 deferred maintenance total of $10.9311.92 billion. The buildings category comprised 19% of the total, followed by 1718% for other structures and 6% for irrigation, dams, and other water structures.

Roads, bridges, and trails also reflected the largest share of BLM's FY2016FY2018 deferred maintenance, with 7669% of the $0.8196 billion total. Two other categories of assets had relatively comparable portions, specifically 1014% for buildings and 912% for other structures. The remaining 56% was for irrigation, dams, and other water structures.

Roads, bridges, and trails did not makemade up the largestsmallest portion of FWS's FY2016FY2018 deferred maintenance ($1.4030 billion), as it didunlike for the other agencies. RatherMoreover, the four asset categories had roughly comparable portions, as follows: 28% for other structures27% for buildings; 27% for buildingsother structures; 24% for roads, bridges, and trails; and 21% for irrigation, dams, and other water structuresirrigation, dams, and other water structures; and 22% for roads, bridges, and trails.

Overview of Decade (FY2007-FY2016FY2009-FY2018)

Changes in Estimates in Current and Constant Dollars

As shown in Table 1,14 and Figure 1, in current dollars,16 the total deferred maintenance estimate for the four agencies rose and then fell over the course of the decade, ending the decade relatively flat. It increased by $0.09 billion overall, from $18.53 billion to $18.62 billion, or 0.5showed considerable variation over the 10-year period from FY2009-FY2018,17 with a peak in FY2012.18 It ended the decade relatively flat, with an increase of $0.36 billion overall, from $19.02 billion to $19.38 billion, or 2%. Both the BLM and NPS estimates increased, by $0.3942 billion (9280%) and $1.3175 billion (1417%), respectively. By contrast, both the FWS and FS estimates decreased, by $1.4471 billion (5157%) and $0.1711 billion (32%), respectively.

Within these overall changes, there was considerable variation among agency trends. The NPS estimate increased fairly steadily over the decade, before falling in FY2016for several years, fell in FY2016, then rose again. The FS estimate was nearly the samesimilar at the beginning and end of the decade, although it fluctuated between $5.10 billion and $6.03 billion throughout the 10-year period. The BLM estimate also fluctuated, rising then falling in the first halffew years of the decade, then increasingrising, leveling off, and rising again to a new high at the end of the decade. The FWS estimate peaked in FY2010, then declined by more than half over the next six yearshad a generally steady decline during the first several years, leveled off somewhat after FY2015, and reached a decade low in FY2018. Figure 1 depicts the annual changes in current dollars for each agency and for the four agencies combined. Factors that might have contributed to the changes are discussed in the "Issues in Analyzing Deferred Maintenance" section, below.

By contrast, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, in constant dollars,19 the total deferred maintenance estimate for the four agencies decreased over the course of the decade by $3.09ten-year period by $3.61 billion, from $21.7122.99 billion to $18.6219.38 billion, or 1416%. Three agencies had overall decreases: $0.3337 billion (3%) for NPS, $1.1422 billion (1719%) for FS, and $1.922.34 billion (5864%) for FWS. However, the BLM estimate increased by $0.32 billion (6550%) over the 10-year period.

As was the case for current -dollar estimates, the overall changes in constant dollars reflected various fluctuations. The BLM estimate fell and rose during the period, with the lowest estimate in the middle of the period (FY2011)FY2011 and the highest at the end (FY2016FY2018). The FWS estimate exceeded $3 billion for each of the first fivefour years before dropping steeply over the next five years to less than half that level. The NPS estimate increased fairly consistently during the first five years, then declined fairly steadily over the next five years. The FS estimate showed considerable annual variation, consisting of several increases and several decreases within the overall reductionsix years to roughly one-third of the FY2009 level. The NPS estimate peaked in FY2010, then mainly declined, until increasing in FY2018. The FS estimate exceeded $6 billion for the first half of the 10-year period. It ranged roughly between $5 billion and $6 billion during the second half of the period, reaching a low of $5.20 billion in both FY2017 and FY2018. Figure 2 depicts the annual changes in constant dollars for each agency and for the four agencies combined.

Table 1. Estimated Deferred Maintenance by Agency in Current Dollars, FY2007-FY2016

(in billions of current dollars)

|

Agency |

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 | |

|

BLM |

0.42 | FY2018

0.47 |

0.53 |

0.44 |

0.40 |

0.61 |

0.74 |

0.74 |

0.75 |

0.81 | |

|

FWS |

2.83 | 0.96

2.79 |

3.01 |

3.02 |

2.85 |

2.70 |

2.01 |

1.53 |

1.33 |

1.40 | |

|

NPS |

9.61 | 10.17 NPS |

10.17 |

10.83 |

11.04 |

11.16 |

11.27 |

11.50 |

11.73 |

10.93 | |

|

FS |

5.66 | 11.92a

5.15 |

5.31 |

5.27 |

5.51 |

6.03 |

5.56 |

5.10 |

5.20 |

5.49 | |

|

Total |

18.53 | 5.20

18.57 |

19.02 |

19.56 |

19.80 |

20.50 |

19.58 |

18.87 |

19.02 |

18.62

|

18.39 19.38 |

Sources: Estimates for FS were taken from itsthe annual budget justification to Congress, except that the FY2016 estimate was-FY2018 estimates were provided by the FS. Estimates for Department of the Interior (DOI) agencies for FY2007FY2009-FY2014 were calculated by CRS based on deferred maintenance ranges provided by the DOI Budget Office; estimates for FY2015 and FY2016-FY2018 were provided by the DOI Budget Office.

Notes: BLM = Bureau of Land Management; FWS = Fish and Wildlife Service; NPS = National Park Service; FS = Forest Service.

a. This figure differs from NPS estimates for prior years, because it includes assets that are not owned by the NPS but for which the agency has maintenance responsibility. Excluding these assets, the FY2018 estimate for NPS was $11.50 billion.Table 2. Estimated Deferred Maintenance by Agency in Constant Dollars, FY2007-FY2016

(in billions of 20162018 constant dollars)

|

Agency |

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

BLM |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

0. |

|

FWS |

3. |

3. |

3. |

3. |

3.12 |

2.87 |

2.09 |

1. |

1. |

1. |

|

NPS |

11.26 |

11.40 |

11.58 |

12. |

12. |

11.87 |

11.74 |

11.68 |

11. |

10.93 |

|

FS |

6. |

5.77 |

6. |

5.95 |

6. |

6.41 |

5. |

5. |

5. |

5. |

|

Total |

21.71 |

|

21.65 |

22.07 |

21.69 |

21.81 |

20. |

19. |

19. |

18.62 |

Sources: FiguresCurrent dollar estimates for FS were taken from the annual budget justification to Congress, except that the FY2016-FY2018 estimates were provided by the FS. Current dollar estimates for Department of the Interior (DOI) agencies for FY2009-FY2014 were calculated by CRS based on deferred maintenance ranges provided by the DOI Budget Office; estimates for FY2015-FY2018 were provided by the DOI Budget Office.

Amounts in 2018 constant dollars were calculated by CRS using U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 3.9.4, "Price Indexes for Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment," for nondefense structures, third quarterannual indexes, at http://wwwhttps://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1#reqid=9&step=1&isuri=1iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey.

Notes: BLM = Bureau of Land Management; FWS = Fish and Wildlife Service; NPS = National Park Service; FS = Forest Service.

|

Figure 2. Change in Deferred Maintenance by Agency in 2018 Constant Dollars, |

|

|

Sources: Notes: BLM = Bureau of Land Management; FWS = Fish and Wildlife Service; NPS = National Park Service; FS = Forest Service. |

Agency Shares of Deferred Maintenance in Current and Constant Dollars

Throughout the decade, agency shares of the deferred maintenance totals differed, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. In both current and constant dollars, in each fiscal year NPS had the largest portion of total deferred maintenance and considerably more than any other agency. FS consistently had the second-largest share, followed by FWS and then BLM. Moreover, in both current and constant dollars, each agency's portion of the total annual deferred maintenance changed over the decade. Specifically, the NPS portion of the annual total grew overall throughout the period, from 5253% in FY2007 to 59% in FY2016FY2009 to 62% in FY2018. By contrast, the FS share of the total decreased over the 10-year period from 3128% to 2927%. The FWS component also declined, from 1516% to 87%, whereas the BLM portion rose from 23% to 4%.155%.20

The asset class or category that included roads typically comprised the largest portion of each agency's deferred maintenance. Roads represented the largest portion of FS deferred maintenance from FY2007 to FY2016FY2009 to FY2018. Over the 10-year period, the NPS roads, bridges, and trails category had the highest share of the agency's deferred maintenance, and irrigation, dams, and other water structures had the smallest. In mostsome years, the portion of NPS deferred maintenance for the "other structures" category exceeded the buildings portion, but in some years the reverse was the case. Roads, bridges, and trails also was the biggest category of BLM's deferred maintenance from FY2007 to FY2016FY2009 to FY2018. Although this category typically represented a majority of the FWS total deferred maintenance in the earlier part of the period, this has not been the case since FY2013. A decline in the dollar estimate for roads, bridges, and trails resulted in a sizeable drop in overall FWS deferred maintenance beginning in FY2013, as discussed below.

|

Figure 4. Deferred Maintenance Total by Agency in Constant Dollars, |

|

|

Sources: Notes: BLM = Bureau of Land Management; FWS = Fish and Wildlife Service; NPS = National Park Service; FS = Forest Service. |

Issues in Analyzing Deferred Maintenance

Fluctuations in deferred maintenance estimates are likely the result of many factors, among them estimation methods, levels of funding, and asset portfolios, and economic conditions, as discussed below. The extent to which these and other factors affected year-to-year changes in any one agency's maintenance backlog is unclear, in part because comprehensive information is not readily available in all cases or has not been examined. Therefore, the data in this report may not fully explain the changes in deferred maintenance estimates over time.

Methodology

Methods for assessing the condition of assets and estimating deferred maintenance have changed over the past decadeyears. As a result, it is unclear what portion of the change in deferred maintenance estimates is due to the addition of maintenance work that was not done on time and what portion may be due to changes in methods of assessing and estimating deferred maintenance. With regard to facility assessment, agencies have enhanced efforts to define and quantify the maintenance needs of their assets. Efforts have included collecting comprehensive information on the condition of facilities and maintenance and improvement needs. For instance, the first cycle of comprehensive condition assessments of NPS industry-standard facilities1621 was completed at the end of FY2006. However, through at least FY2018, NPS continuedNPS continues to develop business practices to estimate the maintenance needs of non-industrynonindustry-standard assets.1722 This category presents particular challenges because it includes unique asset types.1823

Alterations in methodology have contributed to changes in deferred maintenance estimates, as shown in the following examples for roads. The FY2015 FWS budget justification states that

[i]n 2012, Service leadership concluded that condition assessment practices and policies in place at that time were unintentionally producing higher than appropriate [deferred maintenance (DM)] cost estimates for some types of constructed real property. DM estimates for our extensive inventory of gravel and native surface roads are a major contributor to this challenge. In response, the FWS is refining its practices and procedures to improve consistency of DM cost estimates and their use in budget planning. Significant reductions in the DM backlog are resulting from this effort.1924

Subsequent FWS budget justifications have elaborated on changes to methods of estimating deferred maintenance for roads. For instance, the FY2017 document states that "[d]eferreddeferred maintenance estimates for our extensive inventory of roads were further classified to emphasize public use and traffic volume. As a result, minimally used administrative roads are now generally excluded from contributing to deferred maintenance backlog calculations."2025 Of note is that the roads, bridges, and trails category of FWS deferred maintenance declined substantially (by $1.18 billion, 81%) in the past fiveseveral years in current dollars, from $1.46 billion in FY2012 to $0.3328 billion in FY2016FY2018. This decline is reflected in the smaller FWS deferred maintenance total for FY2016FY2018 ($1.4030 billion). The FWS change in the method of estimating deferred maintenance for roads, bridges, and trails appears to be a primary reason for the decreased estimate for this category and total FWS deferred maintenance over the 10-year period.

Similarly, FS attributes variations in deferred maintenance during the decade partly to changes in the methodology for estimating roads. Since FY2008, the roads estimate has been limited to certain types of roads—passenger-car roads (Levels 3-5)—whereas prior year estimates included closed roads and high-clearance roads (Levels 1-2).21 Also26 For example, in FY2013 and FY2014, FS adjusted the survey methodology for passenger-car roads, with the goal of providing more accurate estimates of the roads backlog.22 Overall, the27 The FS estimate of deferred maintenance for roads fell considerably during the decade in current dollars, from $4.16 billion in FY2007 to $3.21 billion in FY2016.23in current dollars by $0.84 billion (22%) from FY2012 to FY2014, from $3.76 billion to $2.92 billion.28 The extent to which the drop is attributable to changes in methodology, including regarding the types of roads reflected in the estimates, is not certain.2429

Finally, in FY2014, the NPS first reflected deferred maintenance for unpaved roads as part of its total deferred maintenance estimate (in agency financial reports). The agency's total deferred maintenance increased in current dollars by $0.26 billion (4%) from FY2013 to FY2014, from $6.57 billion to $6.83 billion. DOI cited the inclusion of unpaved roads as among the reasons for changes in NPS deferred maintenance estimates,30 although the extent of the effect on NPS estimates is unclear.

Broader changes in methodology also occurred during the decade. For example, NPS previously usedDOI agencies had been using an accuracy range of -3015% to +5025% to derive the estimated range of deferred maintenance for industry-standard assets.25 The change to an accuracy range of -15% to +25% of the initial estimate31 The change to a single estimate beginning in FY2015 would have affected NPSDOI deferred maintenance estimates and CRS's calculations of mid-range figures as reflected in this report (through FY2014).

Funding

How much total funding is provided each year for deferred maintenance for the four agencies is unclear because annual presidential budget requests, appropriations laws, and supporting documents typically do not aggregate funds for deferred maintenance. Portions of deferred maintenance funding (for one or more of the four agencies) have come from agency maintenance and construction accounts, recreation fees, concession fees, and the Highway Trust Fund (Department of Transportation) for roads, the Timber Sale Pipeline Restoration Fund (for FS and BLM), NPS concession fees, and the NPS Centennial Challenge account, among other accounts.

In addition, among other accounts. Moreover, funding figures are not directly comparable to deferred maintenance estimates because the estimates are limited to project costs and thus do not reflect indirect costs, such as salaries and benefits for government employees. Annual appropriations figures typically reflect indirect costs. Evaluations of the sufficiency of federal funding for deferred maintenance may be hindered by the lack of total funding figures and by the incomparability of appropriations and deferred maintenance estimates.

Deferred maintenance estimates might vary due to economic conditions that are not related to agency efforts or within the control of facility managers. For example, if deferred maintenance estimates reflect costs of needed materials, fuel, supplies, and labor, then the cost of deferred maintenance might change as the costs of these products and services change.33 Further, DOI has noted that NPS deferred maintenance estimates could fluctuate with market trends and inflation.34 2635 seems to be incomplete or inconsistent in agency budget justifications. In some cases, budget justifications either do not provide FCI figures for assets or provide figures only for certain years. The FY2011 BLM budget justification, for example, notes in several places that the FCI was a new measurement beginning in 2009.27 In other cases, it is not clear ifwhether the FCI figures cover all agency assets or a subset of the assets. Together, the budget justifications present a mix of FCI information using quantitative measurements; percentage measurements; and qualitative statements, such as that a certain number or percentage of structures are in "good" condition, but without corresponding FCI figures.

Although amounts and impacts of deferred maintenance funding may not be readily available, the agencies at times have asserted a need for increased appropriations to reduce their backlogs. As a recent example, the FY2016 NPS budget justification sets out a proposal for increased funds to address deferred maintenance.28 In Interior Budget in Brief for FY2020 sets out a proposal for the establishment of a "Public Lands Infrastructure Fund," with revenues from energy development on federal lands, to be used for deferred maintenance needs of the four agencies (as well as the Bureau of Indian Education).36 As a second example, a 2017 audit report asserted that reducing the FS maintenance backlog "will require devoting the necessary resources over an extended period of time," and that "increasing wildfire management costs have left the agency without extra funding to concentrate on reducing deferred maintenance."37 Moreover, in the past, agencies sometimes attributed reductions in deferred maintenance (or slower rates of increase) in part to additional appropriations, such as those provided in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5).2938 The FY2016 FWS budget justification notes the ARRA funding as one factor contributing to a reduction in the backlog from the FY2010 high, for instance.30

Some observers and stakeholders have identified ways to potentially address deferred maintenance without solely relying on federal funding. For instance, a 2016 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) on NPS deferred maintenance listed various actions that NPS is taking at some park units. They include using donations, volunteers, and partnerships to assist with maintenance; leasing assets to nonfederal parties in exchange for rehabilitation or maintenance; and partnering with states in seeking transportation grants.40 As another example, a 2016 report by a research institute set out options including outsourcing certain agency operations to the private sector, establishing a franchising system for new park units, and disposal of assets.41

Assets

The asset portfolios of the four agencies vary considerably in terms of number, type, size, age, and location of agency assets. Although comprehensive data on these variables over the past decade are not readily available, it is likely that they affect agency maintenance responsibilities and maintenance backlogs. For instance, NPS has more assets than the other DOI agencies, a sizeable portion of which were constructed before 1900 or in the first half of the 20th century. Moreover, some of theseThe 2016 GAO report assessed various characteristics of the NPS maintenance backlog, including the age of park units. The agency determined that of the total FY2015 NPS deferred maintenance,42 park units established over 100 years ago had the largest share (32%). Further, park units established more than 40 years ago collectively accounted for 88% of all NPS deferred maintenance.43 Moreover, some NPS assets are in urban areas or are iconic structures, which could affect maintenance costs.31

The effect of changes in agency asset portfolios on deferred maintenance is not entirely clear. However, it could be asserted that the acquisition of assets, such as a sizeable number of large or iconic assets in relatively poor condition, would increase regular maintenance needs and the backlog, if maintenance is not performed when scheduled. Similarly, it could be argued that disposal of assets, such as a large quantity of old assets in poor condition, could reduce deferred maintenance.

Agencies have examinedFor instance, the NPS asserted that "when parks are created or when new land is acquired, the properties sometimes come with facilities that are in unacceptable condition or are unstable for the park or partner organizations.... When facilities are excess to the park ... they also contribute to the deferred maintenance backlog."45 Similarly, it could be argued that disposal of assets, such as a large quantity of old assets in poor condition, could reduce deferred maintenance. For example, a 2017 audit of the FS recommended that the agency "establish goals and milestones to aggressively reduce the number of unused or underused assets in the agency's portfolio" as one way to reduce maintenance backlogs given limited resources.46

Agencies examine whether to retain assets in their current condition or dispose of some assets, as the following examples indicate. FS has sought to reduce its maintenance backlog by conveying unneeded or underused administrative sites, as well as decommissioning roads, road and facility infrastructure, and nonpriority recreation sites.32 FWS attributed recent47 FWS has attributed reductions in deferred maintenance in part to "disposing of unneeded assets."33 NPS identified48 NPS identifies assets that are not critical to the agency's mission and that are in relatively poor condition for potential disposal. NPS laterIn the past, the agency has noted that although the agency seeks to improve the condition of its asset portfolio by disposing of assets, "analysis of removal costs versus annual costs often precludes the removal option."34

Economic Conditions

Deferred maintenance estimates might vary due to economic conditions that are not related to agency efforts or within the control of facility managers. For example, if deferred maintenance estimates reflect costs of needed materials, supplies, and labor, then the cost of deferred maintenance might change as the costs of these products and services change. Further, NPS noted that deferred maintenance estimates could fluctuate with market trends and inflation.35 In a wider economic context, FS noted that the increase (in current dollars) in the deferred maintenance estimate for roads from FY2006 to FY2007 was partly the result of rises in fuel prices and other associated construction costs.36

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Assets managed by the |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

This definition is taken from the Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

The |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The change to a single figure resulted from revisions to federal financial accounting standards that took effect in FY2015. See the Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Agency Financial Report, FY2014, p. 126, at http://www.doi.gov/pfm/afr/2014/upload/DOI-FY-2014-AFR.pdf. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ibid, p. 126. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

For instance, the FY2015 deferred maintenance estimate was taken from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Justification, p. 411, at https://www.fs.fed.us/about-agency/budget-performance. Information on the deferred maintenance |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

CRS calculated this mid-range figure as the average of the high and low estimates. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

In addition, policy discussions of agency deferred maintenance commonly have referred to a single mid-range estimate, as shown in this report. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The DOI Budget Office has provided deferred maintenance information to CRS periodically throughout the decade. These estimates are generally based on DOI financial reports and may differ from figures reported by the agencies independently. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.

|

|

Thus the estimates do not reflect indirect costs, such as salaries and benefits for government employees. |

For comparison, the four agencies combined had |

|||||||||||||||||

| 13. | This figures differs from NPS estimates for prior years, because it includes assets that are not owned by the NPS but for which the agency has maintenance responsibility. Excluding these assets, the FY2018 estimate for NPS was $11.50 billion, as reflected in DOI financial reports. | |||||||||||||||||||

For additional information on NPS deferred maintenance, see CRS Report R44924, The National Park Service's Maintenance Backlog: Frequently Asked Questions, by Laura B. Comay. 16.

|

|

"Current dollar" figures have not been adjusted for inflation. 17.

|

|

In this report, the 10-year period from FY2009-FY2018 is sometimes referred to as a "decade." 18.

|

|

For DOI agencies, for each year from FY2009-FY2014, CRS calculated a mid-range deferred maintenance figure based on the average of the high and low estimates provided by DOI to CRS. This report reflects CRS's mid-range calculations for these years, as previously noted. 19.

|

|

"Constant dollar" figures have been adjusted for inflation. |

| |||||||||||

|

An analysis of data over a longer period would provide additional perspective and in some respects a different one than presented in this report. For instance, in current dollars the four agencies had a combined deferred maintenance of $14.40 billion in FY1999, the first year for which estimates for all agencies are readily available. In contrast to the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Industry-standard assets include buildings, housing, campgrounds, trails, unpaved roads, water utilities, and wastewater utility systems. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. | See U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017, p. ONPS-Ops&Maint-17, at https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2017. Hereinafter cited as FY2017 NPS Budget Justification.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Currently |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2015, p. NWR-30, at http://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2015/upload/FY2015_FWS_Greenbook.pdf. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017, |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Phone communication between CRS and FS staff on March 17, 2015, and Forest Service annual budget justifications.

Information provided to CRS by the Forest Service Legislative Affairs Office on March 13, 2015. Other years during the decade had varying amounts of increase or decrease in the roads backlog related to prior years. An additional example of a change in assessing roads derives from FY2008. Since that year, the roads estimate has been limited to certain types of roads—passenger-car roads (Levels 3-5)—whereas prior year estimates included closed roads and high-clearance roads (Levels 1-2). The FS estimate of deferred maintenance for roads decreased in current dollars by $0.76 billion (18%) from FY2007 to FY2008, from $4.16 billion to $3.40 billion. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. |

Information provided to CRS by the Forest Service Legislative Affairs Office on March 13, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 23. |

Following the particular changes mentioned, the roads estimate decreased in current dollars by $0.76 billion from FY2007 to FY2008, and by $0.84 billion from FY2012 to FY2014. (Other years during the decade had varying amounts of increase or decrease related to prior years.) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 24. |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2007, p. 93. This source states that this was "the accepted industry accuracy range" at the time. CRS did not seek to establish how long this accuracy range was used by the NPS and whether it was used by other DOI agencies in any years during the decade examined. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 30.

|

|

Information provided to CRS by the DOI Budget Office on February 27, 2015. 31.

|

|

See, for example, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Agency Financial Report FY 2014, p. 126, at https://www.doi.gov/pfm/afr/2014. 32.

|

|

In addition to changes in methodology, the accuracy and consistency in agency application of estimation methods and in reporting on deferred maintenance may also affect estimates. For instance, the 2017 audit of FS deferred maintenance (for FY2014 and FY2015) identified inaccuracies and inconsistencies in some areas. See USDA 2017 FS Audit, pp. 27-31, at https://www.usda.gov/oig/webdocs/08601-0004-31.pdf. 33.

|

|

For example, the FS noted that an increase (in current dollars) in the deferred maintenance estimate for roads from FY2006 to FY2007 was partly the result of rises in fuel prices and other associated construction costs. See FY2009 FS Budget Justification, pp. 15-18, at http://www.fs.fed.us/publications/budget-2009/fy2009-forest-service-budget-justification.pdf. 34.

|

|

Information provided to CRS by the DOI Budget Office on February 27, 2015. |

The facilities condition index is an accepted industry measure of the condition of constructed assets at a specific point in time, and it serves as a performance measure for condition improvement. | |||||||||

| 27. | It is the ratio of the deferred maintenance to the current replacement value of the asset. As a general guideline, a facility with an FCI less than 0.15 is considered to be in acceptable condition. See U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. | USDA 2017 FS Audit, p. 6. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2016, p. NWR-31, at http://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2016/upload/FY2016_FWS_Greenbook.pdf. Information provided to CRS by DOI (for NPS) and by FS also attributed reductions or slower growth of deferred maintenance to ARRA funding. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 31. |

As one example, the NPS has identified deferred maintenance of Arlington Memorial Bridge at about $250 million, although estimates vary depending on the method for repairing, rehabilitating, or replacing the historic steel drawbridge span. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 32. |

See, for example, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fiscal Year 2008 President's Budget, Budget Justification, pp. 17-23 – 17-28, at http://www.fs.fed.us/publications/budget-2008/fy2008-forest-service-budget-justification.pdf. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 33. |

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2016, p. NWR-31, at http://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2016/upload/FY2016_FWS_Greenbook.pdf. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 34. |

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017, p. ONPS-Ops&Maint-14, at https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 35. |

Information provided to CRS by the DOI Budget Office on February 27, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||

| 36. | U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fiscal Year 2009 President's Budget, Budget Justification, pp. 15-18, at http://www.fs.fed.us/publications/budget-2009/fy2009-forest-service-budget-justification.pdf. 40.

|

|

Government Accountability Office, National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts, GAO-17-136, pp. 34-37, December 2016, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136. Hereinafter cited as GAO 2016 NPS Asset Maintenance Report. 41.

|

|

Property and Environment Research Center, Breaking the Backlog, 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem, February 2016, at https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/old/pdfs/BreakingtheBacklog_7IdeasforNationalParks.pdf. 42.

|

|

The total FY2015 deferred maintenance estimate cited by GAO was $11.9 billion. This figure is different than the figure reflected in this CRS report ($11.73 billion), because it reflects assets that are not owned by the agency but for which the agency has maintenance responsibility. 43.

|

|

GAO 2016 NPS Asset Maintenance Report, pp. 22-23, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136. Note that the year a park unit was established is not necessarily reflective of the age of the assets in the unit; for example, newly established units of the National Park System may contain historic properties. 44.

|

|

As one example, the NPS is undertaking a $227 million renovation of Arlington Memorial Bridge to address deferred maintenance. Recent deferred maintenance estimates for the bridge have varied depending on the method for repairing, rehabilitating, or replacing the historic steel drawbridge span. For information on the bridge restoration, see the NPS website at https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/management/bridge-rehabilitation.htm. 45.

|

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020, p. CONST-66, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/fy2020-nps-justification.pdf. 46.

|

|

USDA 2017 FS Audit, p. 11. 47.

|

|

See, for example, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, FY2020 Budget Justification, p. 83 and p. 127, at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/usfs-fy-2020-budget-justification.pdf. 48.

|

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2016, p. NWR-31, at http://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2016/upload/FY2016_FWS_Greenbook.pdf. 49.

|

U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017, p. ONPS-Ops&Maint-14, at https://www.doi.gov/budget/appropriations/2017. |