Five-Year Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing Program: History and Background

Changes from February 1, 2017 to August 23, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management's Five-Year Program for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing: History and Final Program for 2017-2022

Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Background

- Legal Framework

- Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act

- Other Federal Statutes

- National Environmental Policy Act

- Coastal Zone Management Act

- Five-Year Program Development Process

- Five-Year Programs Submitted in Earlier Years

- Five-Year Program for 2017-2022

- Market Conditions Affecting the 2017-2022 Program

- Offshore Resource Estimates for the 2017-2022 Program

- Moratoria and Withdrawals Affecting the 2017-2022 Program

- Proposed Leasing Schedule by Region

- Gulf of Mexico Region: Ten Lease Sales

- Alaska Region: One Lease Sale

- Atlantic Region: No Lease Sales

- Pacific Region: No Lease Sales

- Role of Congress

- Public Comment

- Oversight Hearings

- Legislation

- Review of Final Program

Figures

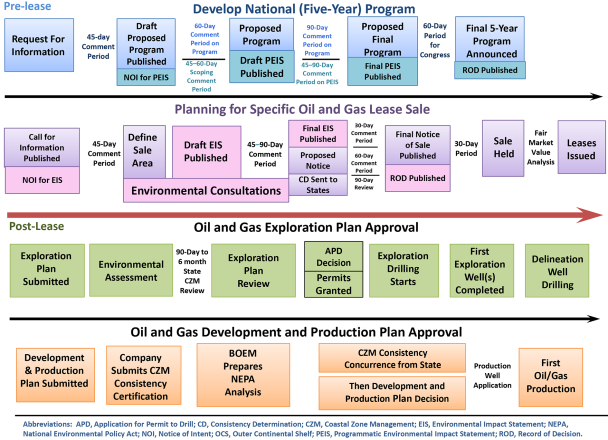

- Figure 1. OCS Oil and Gas Leasing, Exploration, and Development Process

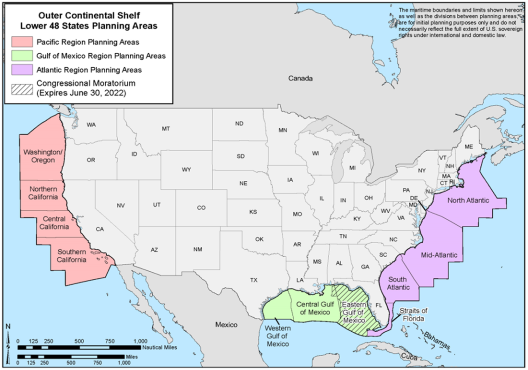

- Figure 2. BOEM's OCS Regions and Planning Areas, Lower 48 States

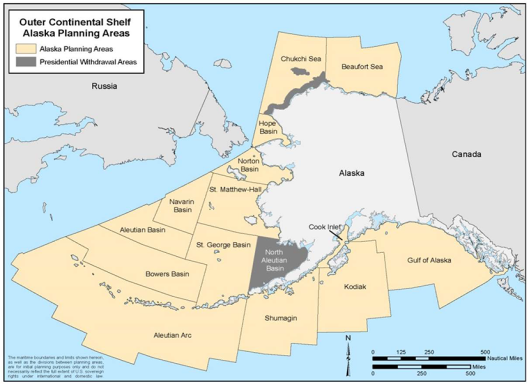

- Figure 3. BOEM's OCS Alaska Region and Planning Areas

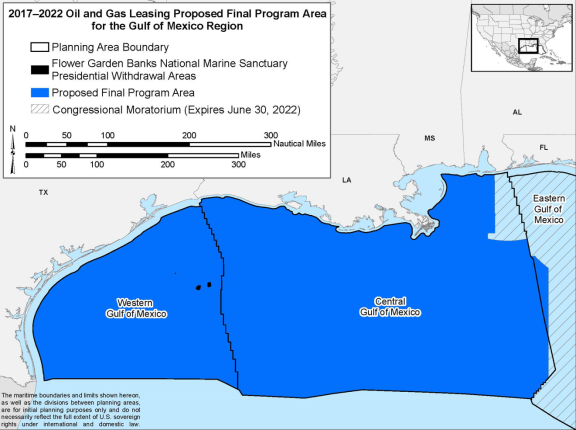

- Figure 4. BOEM's Final Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in the Gulf of Mexico

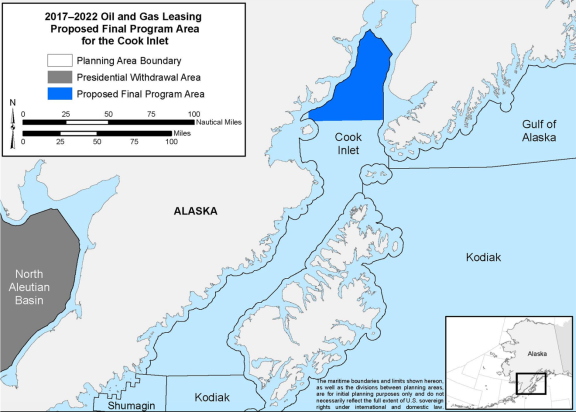

- Figure 5. BOEM's Final Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in Alaska

- Figure 6. BOEM's Originally Proposed Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in the Atlantic

Summary

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), within the Department of the Interior (DOI), has prepared a five-year plan—referred to by BOEM as a "five-year program"—for offshore oil and gas leasing on the U.S. outer continental shelf (OCS) from mid-2017 through mid-2022. Currently, BOEM is implementing a previous five-year program for the 2012-2017 period. BOEM develops the leasing programs underUnder Section 18 of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, as amended (OCSLA; 43 U.S.C. §§1331-1356b). The law requires, the Secretary of the Interior tomust prepare and maintain forward-looking plans —typically referred to as five-year programs—that indicate proposed public oil and gas lease sales in U.S. waters. In doing so, the Secretary must balance national interests in energy supply and environmental protection.

BOEM's development of a five-year program typically takes place over two or three years, during which successive drafts of the program are published for review and comment. All available leasing areas are initially examined, and the selection may then be narrowed based on economic and environmental analysis to arrive at a final leasing schedule. At the end of the process, the Secretary of the Interior must submit each program to the President and to Congress for a period of at least 60 days, after which the proposal may be approved by the Secretary and may take effect with no further regulatory or legislative action. BOEM also develops a programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) for the leasing program, as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. §4321). The PEIS examines the potential environmental impacts from oil and gas exploration and development on the outer continental shelf (OCS) and considers a reasonable range of alternatives to the proposed plan.

On January 17, 2017, former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell issued a record of decision approving BOEM's final offshore oil and gas leasing program for 2017-2022. The final program schedules 11 OCS lease sales, including 10 in the Gulf of Mexico and 1 in the Alaska region. No sales are scheduled for the Atlantic or Pacific regions. Three sales proposed in earlier drafts of the program—one in the Atlantic and two off of Alaska—were not ultimately included in the program. An incoming Administration could not revise a finalized program—for example, to restore excluded sales or to add new sales—without restarting the program development process.

On January 4, 2018, the Trump Administration released a draft proposed five-year program for 2019-2024, which would replace the final years of the Obama Administration program. The draft proposes a total of 47 lease sales during the five-year period, covering all four OCS regions. For more information on the 2019-2024 draft proposed program, see CRS Report R44692, Five-Year Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing Program for 2019-2024: Status and Issues in Brief.Congress has typically been actively involved during the planning phases of BOEM's five-year leasing programs. For example, Since 1980, nine distinct five-year programs and a revised version of one program have been submitted to Congress. The five-year programs have reflected the offshore oil and gas leasing policies of different presidential administrations, along with input from states, Members of Congress, and other stakeholders. In November 2016, then-Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell submitted BOEM's final offshore oil and gas leasing program for 2017-2022, and issued a record of decision approving the program in January 2017. The 2017-2022 program scheduled 11 lease sales in particular regions and planning areas of the OCS. BOEM identifies four OCS regions—the Gulf of Mexico region, the Alaska region, the Atlantic region, and the Pacific region—comprising a total of 26 planning areas. The 2017-2022 final program scheduled lease sales in two of these regions (10 sales in the Gulf of Mexico region and 1 in the Alaska region). No lease sales were scheduled for the other two regions of the OCS, the Atlantic region and the Pacific region. An Atlantic lease sale and two Alaska lease sales proposed in earlier versions of the program were not ultimately included.

The 114th Congress exercised both of these types of influence with respect to the program for 2017-2022. Further, although Congress's role under the OCSLA does not include direct approval or disapproval of the program, Members may directly influence the terms of a program through legislation. Some legislation in the 114th Congress, including H.R. 1487/S. 791, H.R. 1663, H.R. 3682, H.R. 4749, S. 1276, S. 1278, S. 1279, S. 2011, and S. 3203, would have altered the 2017-2022 program by adding certain lease sales or making other programmatic changes. Other bills, including H.R. 1895, H.R. 2630, H.R. 3927, H.R. 4535, S. 1430, S. 2155, and S. 2238, would have influenced the program by prohibiting leasing in various parts of the OCS. None of these bills was enacted. The 115th Congress could introduce legislation to alter the terms of the Administration's final program for 2017-2022, or it could choose not to do so.

Introduction

Under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA), as amended,1 the Department of the Interior (DOI) must prepare and maintain forward-looking five-year plans—referred to by DOI as "five-year programs"—that indicate proposed public oil and gas lease sales in U.S. waters over a five-year period.2 In preparing each program, DOI must balance national interests in energy supply and environmental protection.3 The lead agency within DOI responsible for the program is the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).4

BOEM's development of a five-year program typically takes place over two or three years, during which successive drafts of the program are published for review and comment. All available leasing areas are initially examined,5 and the selection may then be narrowed based on economic and environmental analysis to arrive at a final leasing schedule. At the end of the process, the Secretary of the Interior must submit each program to the President and to Congress for a period of at least 60 days, after which the proposal may be approved by the Secretary and may take effect with no further regulatory or legislative action.6

As required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the planning process includes a programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS).7 The PEIS examines the potential environmental impacts from oil and gas exploration and development on the outer continental shelf (OCS) and considers a reasonable range of alternatives to the proposed plan. Public comments from stakeholders, including state governors, companies, individuals, and public interest organizations, are addressed in both the PEIS and the five-year program itself. Because of the stages of review and comment required under both the OCSLA and NEPA, the Administration could not revise a finalized program—for example, to add new sales—without restarting the program development process. However, scheduled sales could potentially be canceled (but could not becancelled (but not added) during implementation of the program, based on requirements for environmental review that are associated with each individual sale.

On November 18, 2016, BOEM releasedthen-Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell submitted to Congress the third and final version of itsBOEM's oil and gas leasing program for 2017-2022.8 Former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell The Secretary issued a record of decision approving the final program on January 17, 2017.9 The final program was revised from a March 2016 proposed program (PP)10 and a January 2015 draft proposed program (DPP).11 The final program schedulesscheduled 11 lease sales on the OCS: 10 in the Gulf of Mexico region, 1 in the Alaska region, and none in the Atlantic or Pacific regions (see Table 3). Three sales proposed in earlier versions of the program—one in the Atlantic and two off of Alaska—were not ultimately included in the program.12

The leasing decisions in BOEM's five-year programs may affect the economy and environment of individual coastal states and of the nation as a whole. Accordingly, Congress has typically been actively involved in the planning process for the five-year programs. Under the OCSLA, Congress's review of BOEM's final program does not include approval or disapproval of the program. However, Members of Congress may influence the program in other ways. Members may convey their views on the Administration's proposals by submitting public comments on draft versions of the program during formal comment periods, and they may evaluate the program in committee oversight hearings. More directly, Members may introduce legislation to set or alter a program's terms. The 114thVarious Members of Congress pursued all these types of influence with respect to the proposed program for 2017-2022.

The first twothree sections of this report discuss the history and legal framework for BOEM's five-year offshore oil and gas leasing programs. Subsequent sections outline BOEMleasing programs and outline the agency's development process,. Subsequent sections briefly summarize previous programs, and analyze the program for 2017-2022. The final section of the report discusses the role of Congress, with a focus on congressional oversight and legislation related to the 2017-2022 program. For a status report on the 2017-20222019-2024 program and discussion of issues for Congress, see CRS Report R44692, Five-Year Program for Federal Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing Program for 2019-2024: Status and Issues in Brief.

Historical Background13

In 1953, Congress enacted two laws that addressed jurisdiction and rights off the coasts of the United States, including rights to regulation of subsurface oil and natural gas exploration and production. The first of these acts, the Submerged Lands Act,14 provides that coastal states are generally entitled to an area extending 3 geographical miles15 from their officially recognized coasts (or baselines).16 The second, the OCSLA, defined the OCS as "all submerged lands lying seaward of" state coastal waters that are subject to the jurisdiction and control of the United States.17 The OCSLA has as its primary purpose "expeditious and orderly development [of OCS resources], subject to environmental safeguards, in a manner which is consistent with the maintenance of competition and other national needs."18

As offshore activities expanded in the years following adoption of the OCSLA, Congress sought a means by which to allow for expedited exploration and production in order to achieve national energy goals while also providing for environmental protection, opportunities for state and local governments affected by offshore activity to have their voices heard, and a competitive bidding and leasing process.19 The product was the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act Amendments of 1978.20 This legislation added a number of new provisions to the OCSLA, including Section 18, which mandates the creation and maintenance of an OCS leasing program to "best meet national energy needs for the five-year period following its approval or reapproval."21 These five-year programs, which include schedules for lease auctions, have provided the framework for OCS oil and gas exploration and production ever since the first one was adopted by DOI in 1980.

Although the 1978 amendments were the last major overhaul to the OCSLA, Congress has taken other actions since that time that have altered the scope of offshore oil and gas exploration and production. The Deep Water Royalty Relief Act of 1995 attempted to encourage exploration and production in deep water by providing relief from otherwise applicable royalty payment requirements for some deepwater oil and natural gas production.22 The Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 directed the leasing of certain regions of the Gulf of Mexico for oil and gas exploration and production and placed a moratorium on leasing in other regions.23 It also created a mechanism for sharing revenues from leasing in the region with Gulf states and the Land and Water Conservation Fund.2324 Also, starting in 2008, Congress removed language from annual Interior appropriations legislation that had been in place to bar leasing and related activities in certain OCS regions.2425 These legislative actions helped to shape subsequent five-year programs.

Legal Framework25

26

The statutory framework governing BOEM's development of a five-year offshore oil and gas leasing program includes the OCSLA as well as other federal statutes, particularly NEPA and the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA).26

Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act

Section 18 of the OCSLA provides

:The Secretary [of the Interior] ... shall prepare and periodically revise, and maintain an oil and gas leasing program to implement the policies of this subchapter. The leasing program shall consist of a schedule of proposed lease sales indicating, as precisely as possible, the size, timing, and location of leasing activity which he determines will best meet national energy needs for the five-year period following its approval or reapproval.2728

Section 18 further provides that the OCS is to be managed in a manner "which considers economic, social, and environmental values" of the resources of the OCS as well as the potential impact of oil and gas exploration on the marine, coastal, and human environments.2829

Specifically, Section 18 directs the Secretary to schedule the timing and location of oil and gas exploration and production among the regions of the OCS based on consideration of a variety of factors, including existing geographical, geological, and ecological characteristics of the regions; relative environmental and other natural resource considerations of the regions; the relative interest of oil and natural gas producers in the regions; and the laws, goals, and policies of the states that would be affected by offshore exploration and production in the region. In addition to striking this balance, leasing under the five-year program must also "be conducted to assure receipt of fair market value for the lands leased and the rights conveyed by the Federal Government."2930 The OCSLA also requires that the five-year program include estimates on appropriations and staffing needs.30

The OCSLA also imposes a number of consultation requirements. During preparation of the five-year program, the Secretary of the Interior must "invite and consider suggestions for such program from any interested Federal agency, including the Attorney General, in consultation with the Federal Trade Commission, and from the Governor of any State which may become an affected State under such proposed program."3132 In addition to these mandatory consultation requirements, the Secretary may choose to consult with local government officials in affected states.3233

Once the Secretary has satisfied these consultation and other requirements and prepared a proposed program, that program must be submitted to the governor of each affected state for further comments at least 60 days prior to publication of the proposed program in the Federal Register.3334 The OCSLA also authorizes the Attorney General, in coordination with the Federal Trade Commission, to submit comments regarding potential effects of the proposed program on competition.3435 Subsequently, at least 60 days prior to its approval, the Secretary must submit the proposed program to Congress and the President, along with an explanation as to why any specific recommendation of the Attorney General or a state or local government was not accepted.3536 Once these steps have been completed, the Secretary is free to approve a final five-year program. The OCSLA also authorizes the Secretary to revise the five-year program at any time pursuant to a mandated review, although any revision that is "significant" must go through the process for the initial five-year program described above.36

The responsibilities of the Secretary of the Interior with respect to the five-year program under the OCSLA are carried out by BOEM. The regulations applicable to BOEM's preparation of the five-year program include details regarding these consultation requirements. For example, BOEM is required to send letters to governors of affected states requesting that they identify specific laws, goals, and policies that they would like BOEM to consider during preparation of the five-year program.3738 The regulations also outline requirements for publication of the proposed program in the Federal Register.

Other Federal Statutes

While the OCSLA and the applicable regulations guide the five-year planning process, other federal statutes also play a role in the program's formation. Two federal statutes that play a prominent role in the preparation of the five-year program are NEPA and the CZMA.

National Environmental Policy Act

Section 102(2)(C) of NEPA requires all federal agencies to prepare a detailed statement of the environmental impact of and alternatives to major federal actions significantly affecting the environment.3839 In many cases the process for compliance with this requirement includes an environmental assessment (EA) that determines whether an action is a major federal action significantly affecting the environment.3940 However, if the agency has determined that the proposed action is a major federal action without conducting an EA, then the agency moves directly to preparing the statement of the environmental impact of and alternatives to the proposed federal action, known as an environmental impact statement (EIS).4041 This is the case with BOEM's five-year programs; the significance of the program's impact on the environment is assumed. Therefore, BOEM prepares a programmatic EIS (PEIS)4142 concurrently with preparation of the five-year program. This process is explained in further detail throughout this report.

Coastal Zone Management Act42

43

Under the CZMA,4344 states are encouraged to enact coastal zone management plans to coordinate protection of habitats and resources in coastal waters.4445 The CZMA establishes a policy of preservation alongside sustainable use and development compatible with resource protection.4546 State coastal zone management programs that are approved by the Secretary of Commerce are eligible to receive federal monetary and technical assistance. State programs must designate conservation measures and permissible uses for land and water resources4647 and must address various sources of water pollution.4748

The CZMA also requires that the federal government and federally permitted activities comply with these state programs.4849 To that end, the BOEM regulations governing the five-year program provide that "[i]n development of the leasing program, consideration shall be given to the coastal zone management program being developed or administered by an affected coastal State."4950 The regulations require BOEM to request information concerning the relationship between a state's coastal zone management program and OCS oil and gas activity from both the governors of affected coastal states and the Secretary of Commerce prior to development of the leasing program.50

Five-Year Program Development Process51

52

BOEM's development of a five-year program typically takes place over two or three years, during which successive drafts of the program are published for review and comment. The drafts are also submitted to state governors and federal agencies and, in later stages, to Congress and the President (see discussion of consultation requirements in the "Legal Framework" section, above). Each step of the process involves additional public comment and environmental review. After the program takes effect, individual lease sales also undergo environmental review and public comment, as do companies' exploration and development plans on leased tracts. Figure 1 outlines the steps from development of the five-year program to actual oil and gas production in an individual well.

|

Figure 1. OCS Oil and Gas Leasing, Exploration, and Development Process |

|

|

Source: BOEM oil and gas leasing flow chart, at https://www.boem.gov/Oil-and-Gas-Energy-Program/Leasing/Five-Year-Program/BOEM-OCS-Oil-and-Gas-Leasing-Process-Diagram.aspx. |

Because of the analysis and review undertaken at each stage of drafting the five-year program, the successive drafts represent a winnowing process. The initial draft proposed program (DPP) examines all of the agency's available planning areas for oil and gas leasing,5253 analyzing them according to factors in Section 18 of the OCSLA and considering public input, in order to develop an initial schedule of proposed lease sales. In the next version of the plan, the proposed program (PP), only those areas listed in the initial schedule undergo further analysis and environmental review. On the basis of this more targeted analysis, BOEM might remove proposed sales but would not add new sales. The same is true for the final version of the plan—the agency may remove proposed sales at the final stage but maysubsequent versions of the program, BOEM might remove proposed sales on the basis of further analysis, but could not add new sales without reverting to an earlier stage of the process and undertaking new environmental reviews. The steps of the process are discussed in greater detail below.

- Step 1. Request for Information. BOEM initiates development of a new five-year program by publishing in the Federal Register a request for information (RFI) from interested parties concerning regional and national energy needs for the next five-year period; leasing interests of possible oil and gas producers; environmental concerns; and concerns of state and local governments, tribes, and the public, among other issues. The RFI for the 2017-2022 leasing program was published on June 16, 2014, and was followed by a comment period during which the agency received more than half a million comments.

5354

- Step 2. Draft Proposed Program/Notice of Intent for PEIS.

On the basis of its analysis and the public comments received in the RFI, BOEM publishes a draft proposed program (DPP) that represents the initial proposal for lease sales in the upcoming five-year period. The DPP isBOEM publishes a draft proposed program (DPP), the first of three decision documents leading up to BOEM's eventual final program.5455 The DPP analyzes all OCS planning areas available for leasingand identifies a preliminary list of areas proposed for lease sales over the next five years. It also contains a preliminary schedule for the proposed sales, taking into account comments received on the RFI, and identifies a preliminary lease schedule. BOEM published its DPP for 2017-2022 on January 29, 2015, with a comment period that closed on March 30, 2015.5556 BOEM received more than 1 million comments on the DPP.

When the DPP is published, BOEM also issues a notice of intent (NOI) to publish a programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) for the proposed lease areas and seeks public input (through a scoping process) on the issues that should be analyzed in the PEIS. The NOI for the 2017-2022 program was published on January 29, 2015, along with the DPP.5657

- Step 3. Proposed Program/Draft PEIS. After further analyzing the lease sale areas proposed in the DPP according to the required factors in Section 18 of the OCSLA, and taking into account the public comments received on the DPP, BOEM publishes a proposed program (PP)

for the five-year period. This second versionof the programrefines the proposed locations and timing for OCS oil and gas lease sales. BOEM submits the PP to Congress, state governors, and relevant federal agencies and also solicits public comment on the program. BOEM published the PP for 2017-2022 on March 15, 2016, with a comment period that closed on June 16, 2016.57

58The PP is accompanied by a draft PEIS analyzing the OCS areas that were identified for leasing at the DPP stage. The comment period for the 2017-2022 draft PEIS closed on May 2, 2016.58

- 59Step 4. Proposed Final Program/Final PEIS. The final document published by BOEM is the PFP, which is based on additional analysis of the factors in Section 18 of the OCSLA, along with analysis of the public comments received on the PP. The PFP is announced in the Federal Register and submitted to the President and Congress for a period of at least 60 days. Although Congress does not have an approval role for the PFP, the 60-day review period could allow for legislation to be introduced that would influence the outcome of the program. BOEM published the PFP for 2017-2022 on November 18, 2016.

5960

Along with the PFP, BOEM publishes a final PEIS that concludes the analysis of the areas proposed for leasing. The final PEIS is submitted to the President and Congress along with the PFP. BOEM released the final PEIS for the 2017-2022 program on November 18, 2016.6061

- Step 5. Approval of PFP by Secretary of the Interior. At least 60 days after

BOEM submits the PFPthe PFP is submitted to the President and Congress, the Secretary of the Interior may approve the PFP, which then becomes final. The Secretary publishes a record of decision for the final program. Former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell issued a record of decision approving the final program for 2017-2022 on January 17, 2017.61

62Five-Year Programs Submitted in Earlier Years62

63

Since 1980, eightnine distinct five-year programs and a revised version of one program have been submitted to Congress. Following the 60-day review period required by the OCSLA, each of these five-year programs has taken effect as an approved program. This section briefly discusses the previous submissions, dating back to 1980, as shown in Table 1.

|

Years |

Administration Submitting Plan |

Congress |

Number of Sales Listed in Submission |

Number of Sales Held |

Approximate Acres Leased (in millions)a |

|

2017-2022 |

Obama |

114th |

11 |

— | — |

|

2012-2017 |

Obama |

112th |

15 |

|

|

|

2007-2012 |

Obama / G. W. Bush |

111th / 110th |

16 / 21 |

11 |

21.7 |

|

2002-2007 |

G. W. Bush |

107th |

20 |

15 |

20.5 |

|

1997-2002 |

Clinton |

105th |

16 |

12 |

22.9 |

|

1992-1997 |

G. H. W. Bush |

102nd |

18 |

12 |

22.6 |

|

1987-1992 |

Reagan |

100th |

42 |

17 |

24.7 |

|

1982-1987 |

Reagan |

97th |

41 |

23 |

21.0 |

|

1980-1982 |

Carter |

96th |

36 |

12 |

4.1 |

Source: CRS.

a. Acreage leased is shown in BOEM, OCS Lease Sale Statistics, "All Lease Offerings," at http://www.boem.gov/OCS-Lease-Sale-Statistics-All-Lease-Offerings/.

b. The acreage total reflects acres leased for three of the sales (lease sales 249, 250, and 251) but acres bid on for one sale (lease sale 252), because acres leased were not yet available. Not all acres bid on are necessarily leased. c. The George W. Bush Administration developed the original program for 2007-2012 and submitted it to the 110th Congress with a lease schedule containing 21 sales. Following a court order in 2009, DOI revised the program under the Obama Administration and resubmitted it to the 111th Congress with a revised lease schedule containing 16 sales.

cd. This program was originally referred to as the Comprehensive Program 1980-1985, but the covered years were changed to 1980-1982 due mainly to judicial activity. California v. Watt, 688 F.2d 1290 (D.C. Cir. 1981).

The five-year programs have reflected the offshore oil and gas leasing policies of different presidential administrations, along with input from states, Members of Congress, and other stakeholders.

2012-2017 Program. The Obama Administration submitted the 2012-2017 five-year program to Congress under the direction of former Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar.63The program reflected Obama Administration2017-2022 Program. The 2017-2022 program was prepared and submitted to Congress by the Obama Administration. The program included 11 lease sales: 10 region-wide sales in the Gulf of Mexico and 1 sale in Alaska's Cook Inlet. As of early August 2019, 4 sales had been held. 2012-2017 Program. The 2012-2017 program was prepared and submitted to Congress by the Obama Administration.64 The program reflected the Administration's policies on offshore energy development in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and subsequent management reforms.6465 The submission consisted of 15proposed lease sales from August 2012 through August 2017lease sales, including 12 sales in the Gulf of Mexico and 3 sales in the Alaska region. Two of the three Alaska sales were later canceled.65As of late November 2016, 11; 13 lease saleshad beenwere held.66- 2007-2012 Program.67 The George W. Bush Administration prepared and submitted the 2007-2012 five-year program to Congress

under the direction of former Secretary of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne. This submission reflected the Bush Administration's policies on domestic energy production and environmental protection. The program went into effect in July 2007 with a schedule of 21 sales. DOI subsequently revised the schedule in accordance with a 2009 court order.68 The Obama Administration resubmitted the program to Congress in 2010, replacing the original lease sale schedule with a schedule consisting of 16 sales, and approved the leasing program after the 60-day review period.69 Eleven of the 16 sales were held. This five-year program expired in June 2012. - 2002-2007 Program. The 2002-2007 OCS oil and gas leasing plan was submitted to Congress in 2002 under

former Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton.70This submission was consistent with the George W. Bush Administration's policies on energy production.the George W. Bush Administration.70 The proposal consisted of a schedule of 20 lease sales, 15 of which were held before the program expired in June 2007. - 1997-2002 Program. The five-year program for the 1997-2002 period was submitted to Congress in 1996 under

former Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt.71The submission was consistent with national energy policies established during the Clinton Administration.the Clinton Administration.71 The submission listed 16 sales, 12 of which were held before the program expired in June 2002. - 1992-1997 Program. The five-year program for the 1992-1997 period was presented to Congress in 1992 under

former Secretary of the Interior Manuel Lujan.72Planning was consistent withthe George H. W. Bush Administrationpolicies on energy production..72 A schedule of 18 sales was submitted. Twelve sales were held before the program expired in June 1997. - 1987-1992 Program. This five-year program was presented to Congress in 1987 under

former Secretary of the Interior Donald Hodel.73The program reflected Reagan Administration policies.the Reagan Administration.73 The approved lease sale schedule contained 42 sales, 17 of which were held before the program expired in June 1992. - 1982-1987 Program. This submission was presented to Congress in 1982 under

former Secretary of the Interior James Watt.74It was consistent with the Reagan Administration's national energy policies.the Reagan Administration.74 The plan consisted of 41 sales, 23 of which were held before the program expired in June 1987. - 1980-1982 Program. The original Section 18 submission for domestic oil and gas leasing was envisioned during the passage of the 1978 Amendments to the OCSLA and was prepared starting in October 1978.75

Consistent with President Carter's "Energy Message" of April 5, 1979, the program was presented to Congress in April 1980 under the direction of former Secretary of the Interior Cecil D. AndrusThe program was presented to Congress in April 1980, consistent with President Carter's "Energy Message" of April 5, 1979.76 The proposal took effect as an approved plan in June 1980. Under this plan, DOI proposed 36 sales, 12 of which were held.This program was succeeded by the 1982-1987 program. - Lease Sales Held Prior to 1980. The domestic program for oil and gas leasing prior to 1980 encompassed almost 30 years of federal government lease sales conveying more than 3,000 tracts from October 1954 through September 1980.

Five-Year Program for 2017-2022

In November 2016, BOEM released the third andThe final version of itsBOEM's offshore oil and gas leasing program for 2017-2022.77 The final program schedules was approved in January 2017.77 It scheduled 11 lease sales in particular regions and planning areas of the OCS. BOEM identifies four OCS regions, —the Gulf of Mexico region, the Alaska region, the Atlantic region, and the Pacific region—comprising a total of 26 planning areas (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). The four regions are the Gulf of Mexico region, the Alaska region, the Atlantic region, and the Pacific region. The 2017-2022 final program schedules lease sales in two of these regions (Gulf of Mexico and Alaska). The sections below discuss BOEM's decisions for each region—and the market conditions, resource estimates, and other factors affecting the proposals—in greater detail.

Market Conditions Affecting the 2017-2022 Program78

U.S. offshore crude oil production accounted for 16% of U.S. total production in FY2015,79 a decline from FY2010, when offshore production represented 31% of U.S. total crude oil production.80During development of the 2017-2022 program, U.S. offshore crude oil production was declining in absolute terms and as a percentage of total U.S. production. Offshore production volumes declined by about 12% during this periodbetween 2010 and 2015, whereas U.S. total crude oil production increased by about 73% over 2010 levels.79 Offshore natural gas production also fell—by nearly 50%—between 2010 and 2015,80 while duringproduction soared to near-record levels of 9.4 million barrels per day (mbd), an increase of about 73% over FY2010 levels.81

Offshore natural gas accounted for 4% of U.S. total production in FY2015, also a decline from FY2010, when it represented 9.5% of the total.82 Offshore natural gas production volumes fell by nearly 50% between FY2010 and FY2015.83 During the same period, U.S. total annual natural gas production rose by more than 30%, from 21.3 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) to 28.7 Tcf.84

.81 The surge in total U.S. crude oil and natural gas production iswas the result of increased production of shale gas and shale oil in several unconventional onshore formations throughout the United States (e.g., Marcellus, Bakken, Permian Basin, and Eagle Ford). The increased U.S. oil production has helped to reduce imports, primarily from members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The onshore shale oil plays have lower production costs than the deepwater plays that are currently being explored and developed offshore.

As of November 1, 2016, there were 917 producing offshore oil and natural gas leases on 4.5 million acres of the OCS, out of a total of 3,431 active leases on 18.3 million offshore acres. Approximately 86% of the producing leases and 79% of the active leases were located in the Central Gulf of Mexico.85 In a low oil and natural gas price environment, the demand for the acquisition of new offshore leases is likely to be soft, which could impact future production levels. Overall, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) anticipates being explored and developed offshore. A low oil and natural gas price environment during the period of the program's development also contributed to softer demand for the acquisition of new offshore leases. Numbers of active and producing offshore leases declined between 2010 and 2015, and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) anticipated lower domestic investment in oil and gas projects over the 2015-2020 period.82

Nonetheless, offshore oil and gas production was projected to continue to make a significant contribution to the U.S. energy supply picture. Despite the trend of production decline offshore in the early part of the decade, the EIA anticipated that offshore crude oil production in the Gulf of Mexico would recover to record levels in 2017, because of a number of deepwater oil projects expected to come online based on earlier discoveries.83 lower domestic investment in oil and gas projects over the 2015-2020 period.86

|

|

|

|

|

Estimates by the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) of bonus bid revenues from offshore leasing in the next five fiscal years are much lower than for previous five-year periods.87 For example, in ONRR's FY2015 budget request, offshore bonus bid revenues were estimated at around $1 billion annually for FY2015-FY2019.88 In the most recent FY2017 budget request, estimated bonus bid revenues were closer to $500 million annually for FY2017-FY2021.89 The Office of Management and Budget's crude oil price estimates fell from $80-$90 per barrel in the FY2015 budget request to $50-$60 per barrel in the FY2017 budget request. The longer low oil prices persist, the more impact the decline will have on new investment.

Nonetheless, crude oil production on federal lands, particularly offshore, likely will continue to make a significant contribution to the U.S energy supply picture. The EIA anticipates that offshore crude oil production in the Gulf of Mexico will reach record levels of 1.91 mbd in 2017, because of the potential for new deepwater oil projects to come online.90 BOEM stated in the 2017-2022 PP that "energy diversification, including continued oil and natural gas production in the GOM [Gulf of Mexico], the primary OCS region currently available for energy production and development activities, remains vital ... and new production from other OCS regions can also contribute to meeting the country's energy needs."91

Offshore Resource Estimates for the 2017-2022 Program92

85

Oil and gas exploration and production proceed in stages, during which increasedadded data provide growing certainty about the volume of resources present. Prior to discovery by drilling wells, estimated volumes of oil and gas are termed undiscovered resources. When oil or gas is discovered, the volumes of that oil and gas are measured within pools or fields via well penetration or other technology, and are called reserves. Measured reserves are reportedWell owners report measured reserves to the Securities and Exchange Commission by the owners of the wells.93.86 Reserves have been reported for U.S. OCS areas that have been developed, such as the Central and Western Gulf of Mexico and some parts of the California coast, but no reserves of oil or gas have been reported along the Atlantic OCS, because there have been no discoveries. Only modest oil reserves have been reported on the Alaska OCS. Altogether, BOEM estimates that the U.S. OCS has 4.31 billion barrels of proven oil reserves and 16 Tcf6.7 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of dry gas, nearly all of which are located in the Central and Western Gulf of Mexico.94

According to BOEM, the U.S. OCS contains estimated undiscovered technically recoverable resources (UTRR) of 89.9 billion barrels of oil (Bbo) and 327.5 Tcf of natural gas (see Table 2).9588 The Gulf of Mexico contains about 54% of the UTRR for oil and an estimated 43% of the natural gas, with the vast majority of the resources in the Central Gulf of Mexico. About 90% of Alaska's UTRR estimates for oil and 80% for natural gas are contained in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. In preparing its five-year programs under the OCSLA, BOEM must consider the resource potential of individual OCS regions and planning areas along with other factors, such as potential environmental and socioeconomic impacts of oil and gas leasing.

Table 2. Oil and Gas Resource Estimates for the U.S. OCS, 2016

(undiscovered technically recoverable resources)

|

OCS Region |

Oil (Bbo) |

Natural Gas (Tcf) |

|

Alaska |

26.61 |

131.45 |

|

Atlantic |

4.59 |

38.17 |

|

Gulf of Mexico |

48.46 |

141.76 |

|

Pacific |

10.20 |

16.10 |

|

Total |

89.87 |

327.49 |

Source: BOEM, "Assessment of Undiscovered Technically Recoverable Oil and Gas Resources of the Nation's Outer Continental Shelf, 2016," Fact Sheet, at http://www.boem.gov/National-Assessment-2016/. For a discussion of undiscovered technically recoverable resources, see footnote 9588.

Notes: OCS = outer continental shelf; Bbo = billion barrels of oil; Tcf = trillion cubic feet.

BOEM has not updated its estimates since 2016.Moratoria and Withdrawals Affecting the 2017-2022 Program96

89

Some portions of the U.S. OCS were not available for leasing consideration in the 2017-2022 five-year program because U.S. Presidentspresidents had withdrawn those areasthem from consideration,9790 Congress had placed a moratorium on leasing in the areas, or the areas had a protected status that does not allow for oil and gas leasing. These unavailable areas, which BOEM did not consider for the 2017-2022 program, included the following.

- Areas in the Eastern and Central Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA) placed a moratorium on oil and gas leasing in almost all of the Gulf's Eastern planning area and a small portion of its Central planning area through 2022.

9891 - Alaska Withdrawal Areas. President Obama withdrew from disposition for leasing certain ocean areas in the Alaska region.

WithdrawalsAlaska withdrawals that affected the 2017-2022 programfor the Alaska regionincluded those for the North Aleutian Basin planning area, the Hanna Shoal portion of the Chukchi Sea planning area, and the Barrow and Kaktovik whaling areas in the Beaufort Sea(also see below).99 - National Marine Sanctuaries and Marine Monuments. National marine sanctuaries designated by the Secretary of Commerce, as well as national marine monuments established by U.S. Presidents, are withdrawn from future oil and gas leasing activities.100 Such protected areas have been designated in parts of the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and the Gulf of Mexico.

.92 In December 2016, after BOEM's publication of the final program, President Obama made additional Arctic withdrawals under the OCSLA,93 but these did not directly affect the 2017-2022 program, because none of the withdrawn areas overlapped with areas that BOEM had scheduled for leasing in the final program.94

withdrawals under the OCSLA. The President withdrew much of the U.S. Arctic from leasing disposition for an indefinite time period, including the entire Chukchi Sea planning area, almost all of the Beaufort Sea planning area, and planning areas in the North Bering Sea.101 The President also withdrew from leasing consideration certain areas of the Atlantic Ocean associated with major canyons and canyon complexes.102 The President's December 2016 withdrawals did not directly affect the 2017-2022 program, because none of the withdrawn areas overlapped with areas that BOEM had scheduled for leasing in the final program. However, the withdrawals would affect the areas that can be considered for leasing for future five-year programs.

Proposed Leasing Schedule by Region

BOEM's "tailored leasing strategy" separately considers each of the four U.S. ocean regions with respect to the criteria for leasing set out in Section 18 of the OCSLA (see "Legal Framework," above). For each region, BOEM weighs factors including the oil and gas resource potential of the region, existing infrastructure, other ocean uses, environmental issues, and state and local interests and concerns about offshore oil and gas development, among others.

On the basis of its regional analyses, BOEM included in the final program a total of 11 lease sales, all of which take place in either the Gulf of Mexico region or the Alaska region (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Table 3). No lease sales arewere scheduled for the other two regions of the U.S. OCS, the Atlantic region and the Pacific region. An Atlantic lease sale and two Alaska lease sales proposed in earlier versions of the program were not ultimately included. Table 3 shows the oil and gas lease sales scheduled in the program. BOEM stated that, altogether, the program makes available for leasing almost half of the undiscovered technically recoverable oil and gas resources on the U.S. OCS.103

Figure 2. BOEM's OCS Regions and Planning Areas, Lower 48 States

Figure 3. BOEM's OCS Alaska Region and Planning Areas Source: Both figures are from BOEM, 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing: Proposed Program, March 2016, p. 1-2, at http://www.boem.gov/2017-2022-Proposed-Program-Decision/.

|

Year |

Program Area |

Sale Numbera |

|

|

1. |

2017 |

Gulf of Mexico |

249 |

|

2. |

2018 |

Gulf of Mexico |

250 |

|

3. |

2018 |

Gulf of Mexico |

251 |

|

4. |

2019 |

Gulf of Mexico |

252 |

|

5. |

2019 |

Gulf of Mexico |

253 |

|

6. |

2020 |

Gulf of Mexico |

254 |

|

7. |

2020 |

Gulf of Mexico |

256 |

|

8. |

2021 |

Gulf of Mexico |

257 |

|

9. |

2021 |

Alaska - Cook Inlet |

258 |

|

10. |

2021 |

Gulf of Mexico |

259 |

|

11. |

2022 |

Gulf of Mexico |

261 |

Gulf of Mexico Region: Ten Lease Sales

The Gulf of Mexico is the most mature of the four BOEM regions, in that it contains BOEM region, with "the most abundant proven and estimated oil and gas resources, broad industry interest, and well-developed infrastructure."10497 The region accounts for about 97% of all U.S. offshore and gas production.10598 Also, the Central and Western Gulf states—including (Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama—) are supportive of offshore oil and gas activities. For all these reasons, the majority of the lease sales in the 2017-2022 program, as in previous programs, arewere scheduled in the Gulf region (10 of the 11 proposed sales).10699

The region includes three BOEM planning areas: the Western Gulf, the Central Gulf, and the Eastern Gulf (see Figure 4). Almost all of the Eastern Gulf and a small portion of the Central Gulf are closed to oil and gas leasing by the congressional moratorium imposed under GOMESA (see "Moratoria and Withdrawals Affecting the 2017-2022 Program," above). In earlier five-year programs, BOEM and its predecessor agencies scheduled separate sales in each of the three Gulf planning areas. For the 2017-2022 program, BOEM has replaced these area-specific sales with region-wide sales that offer all available lease blocks in the Gulf in each sale. BOEM stated that the change iswas intended "to provide greater flexibility to industry, including more frequent opportunities to bid on rejected, relinquished, or expired OCS lease blocks, as well as facilitating better planning to explore resources that may straddle the U.S.-Mexico boundary."107

|

Figure 4. BOEM's Final Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in the Gulf of Mexico |

|

|

Source: BOEM, 2017-2022 PP, "Maps," at http://www.boem.gov/Gulf-of-Mexico-Region-Program-Area/. |

The final program schedulesscheduled fewer lease sales in the Gulf—and fewer lease sales generally—than were contained in previous five-year programs (see Table 1). For example, the five-year program for 2012-2017 included 12 sales in the Gulf, and the revised program for 2007-2012 also contained 12 Gulf sales. Some Members of Congress expressed concerns about the lower number of lease sales during congressional hearings on the 2017-2022 program.108101 BOEM attributed the decrease to the consolidation of area-specific sales in the Gulf. With all available Gulf blocks offered at each sale, BOEM stated, each individual planning area is made available more times, even though the overall number of lease sales has decreased.109

Alaska Region: One Lease Sale

Interest in exploring for offshore oil and gas in the Alaska region of the U.S. OCS has grown as the region sees decreases in the areal extent of summer polar ice, allowing for a longer drilling season. Recent estimates of substantial undiscovered oil and gas resources in Arctic waters have also contributed to the increased interest.110103 However, the region's severe weather and perennial sea ice, and its lack of infrastructure to extract and transport offshore oil and gas, continue to pose challenges to new exploration. Among 15 BOEM planning areas in the region, the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas are the only two areas with existing federal leases, and only the Beaufort Sea has any producing wells in federal waters (from a joint federal-state unit). Stakeholders including the Statestate of Alaska, as well as some Members of Congress, seek to expand offshore oil and gas activities in the region. Other Members of Congress as well as some environmental groups oppose offshore oil and gas drilling in the Arctic, due to concerns about potential oil spills and about the possible contributions of these activities to climate change.

The Obama Administration at times expressed support for expanding offshore oil and gas exploration in the Arctic, while also pursuing safety regulations that aim to minimize the potential for oil spills.111104 In the five-year program for the period 2012-2017, BOEM included lease sales in three planning areas of the Alaska region: the Beaufort Sea, the Chukchi Sea, and Cook Inlet. However, in October 2015 BOEM canceled its scheduled Chukchi and Beaufort Sea lease sales for 2016 and 2017, citing difficult market conditions and low industry interest.112105

BOEM's earlier program drafts for 2017-2022 also included three Alaska lease sales—again, one each in the Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, and Cook Inlet planning areas. However, for the final program, BOEM removed the sales for the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, and retained only the sale for Cook Inlet (see Figure 5). BOEM stated that it weighed factors that favored sales in the Beaufort and Chukchi planning areas, including the significant hydrocarbon resources in those waters and the support of the Statestate of Alaska for the sales. Nonetheless, BOEM ultimately decided against the sales based on other factors, including "opportunities for exploration and development on [already] existing leases, the unique nature of the Arctic ecosystem, recent demonstration of constrained industry interest in undertaking the financial risks that Arctic exploration and development present, current market conditions, and sufficient existing domestic energy sources already online or newly accessible."113

|

|

|

BOEM noted in particular evidence of a declining industry interest in the Arctic OCS, in the face of low oil prices and Shell Oil Company's disappointing exploratory drilling effort in the Chukchi Sea in 2015.114107 The agency stated that the number of active leases on the Arctic OCS declined by more than 90% between February 2016 and November 2016, as companies relinquished leases they had acquired in previous years rather than incurring the costs of continued investment.115 BOEM observed that, based on the U.S. energy outlook for future years, industry interest in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas may likely to be stronger in years following the 2017-2022 period.116 Additionally, BOEM concluded that, because of the current overall strength of the domestic energy supply, the two Arctic lease sales were not immediately needed to satisfy U.S. energy needs.117

Figure 5. BOEM's Final Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in Alaska Source: BOEM, 2017-2022 PP, "Maps," at http://www.boem.gov/Alaska-Program-Areas/.

Subsequent to BOEM's publication of the final program, President Obama withdrew large portions of the Arctic OCS from future leasing consideration for an indefinite time period (see section on "Moratoria and Withdrawals Affecting the 2017-2022 Program")..110 The withdrawn areas dodid not overlap with BOEM's scheduled Alaska lease sale.

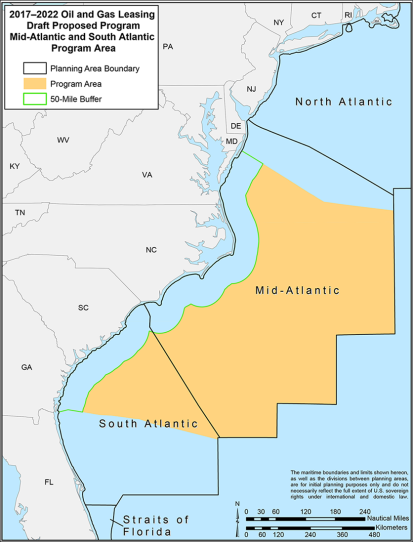

Atlantic Region: No Lease Sales

The final program for 2017-2022 excludesexcluded a lease sale in the Atlantic region that washad been proposed in the DPP version of the program. If conducted, it would have been the first offshore oil and gas lease sale in the Atlantic since 1983. proposed in the DPP version of the program. If conducted, it would have been the first offshore oil and gas lease sale in the Atlantic since 1983.

Geological and Geophysical (G&G) Activities in the Atlantic Ocean In addition to offshore oil and gas leasing, a separate issue for the Atlantic region is estimating the extent and location of its oil and gas resources. Earlier congressional and administrative moratoria on Atlantic leasing activities meant that geological and geophysical (G&G) surveys of the region's offshore resources could not be conducted over the past 30 years. Previous seismic surveys of the region's resources, dating from the 1970s, were accomplished with older technologies that are considered less precise than recent survey methods. In the past several years, BOEM has conducted environmental analysis for proposed new G&G surveys in the region, and it issued a record of decision (ROD) in July 2014 to allow the surveys to go forward. BOEM included in its record of decision measures to mitigate the impacts of G&G activities on marine life, such as time-area closures to protect the North Atlantic right whale and nesting sea turtles off of Florida. Some environmental advocacy groups, as well as some Members of Congress and other stakeholders, expressed opposition to the BOEM decision, arguing that the agency's analysis did not adequately account for the potential impacts of seismic surveys on marine mammals, among other issues. Following the 2014 ROD, a number of companies applied for permits to conduct G&G surveys in the Atlantic region. These applications are still under review by federal agencies and coastal states. The G&G permitting process is taking place outside of the five-year program, which is specifically concerned with lease sales. The House Energy and Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on Atlantic G&G testing in July 2015, during which some Members sought to expedite the permit review process while others opposed letting G&G testing go forward. Witnesses differed in their evaluations of the potential harm to Atlantic marine mammals from seismic activities. Members of Congress have also introduced legislation addressing Atlantic G&G activities. Some bills (such as S. 1279) aim to facilitate G&G surveys, while others (such as S. 2841) would prohibit such activities either in certain areas or throughout the Atlantic.

|

The lack of oil and gas activity in the Atlantic region in the past 30 years was due in part to congressional bans on Atlantic leasing imposed in annual Interior appropriations acts from FY1983 to FY2008, along with presidential moratoria on offshore leasing in the region during those years. Starting with FY2009, Congress no longer included an Atlantic leasing moratorium in annual appropriations acts. In 2008, President George W. Bush also removed the long-standing administrative withdrawal for the region.118111 These changes meant that lease sales could now potentially be conducted for the Atlantic. However, no Atlantic lease sale has taken place in the intervening years.119 As of December 2016, certain parts of the Atlantic are again under presidential moratorium (see section on "Moratoria and Withdrawals Affecting the 2017-2022 Program"), although other areas in the region would be available for leasing.

Figure 6. BOEM's Originally Proposed Program Area for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing in the Atlantic

(subsequently removed from the five-year program)

Source: 2017-2022 PP, p. 4-12.

For both the DPP and PP versions of the 2017-2022 program, BOEM analyzed of a variety of factors for the Atlantic region under Section 18 of the OCSLA. These factors included the region's resource potential and infrastructure needs, ecological and safety concerns, competing uses of the areas—especially by the Department of Defense and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)—and state and local attitudes toward drilling, among others. The initial analysis for the DPP resulted in a planned lease sale in a combined portion of the Mid- and South Atlantic planning areas in 2021 (see Figure 6). However, after the comment period and further analysis, BOEM removed the Atlantic sale in the PP. BOEM gave several reasons for the removal, including "strong local opposition, conflicts with other ocean uses, ... current market dynamics, ... [and] careful consideration of the comments received from Governors of affected states."120113 In particular, BOEM cited conflicts with existing uses, including ocean-dependent tourism, commercial and recreational fishing, commercial shipping and transportation, and Department of Defense and NASA uses.121 BOEM observed that some of these activities coexist with oil and gas activities in the Gulf of Mexico, which has a long history of offshore mineral production. By contrast, BOEM stated, because the Atlantic has little such history, the prospect of drilling has raised many concerns among those who use the ocean for competing purposes.122114

BOEM further cited the broader U.S. energy situation as a factor in its decision not to hold an Atlantic lease sale in the 2017-2022 period. The agency observed that the increases over the past decade in onshore oil and gas production have made national energy needs less pressing. BOEM stated that "domestic oil and gas production will remain strong without the additional production from a potential lease sale in the Atlantic."123

(subsequently removed from the five-year program) |

|

|

Source: 2017-2022 PP, p. 4-12. |

Pacific Region: No Lease Sales

Like other recent five-year programs, the 2017-2022 program schedules no lease sales for the Pacific region. No federal oil and gas lease sales have been held for the region since 1984, although some active leases with production remain in the Southern California planning area. Like the Atlantic region, the Pacific region was subject to congressional and presidential leasing moratoria for most of the past 30 years.124 Although these restrictions were lifted in FY2009, the governors of California, Oregon, and Washington continue to oppose offshore oil and gas leasing in the region.

|

Environmental Analysis for the 2017-2022 Program Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS). Along with BOEM's preparation of the five-year BOEM released its final PEIS for the 2017-2022 program on November 18, 2016. Although the PEIS process is separate from that of the five-year program, it informs the implementation of the leasing program. For example, when implementing the program, BOEM may apply exclusions or mitigation measures identified in the PEIS to avoid or reduce program impacts. In addition to the environmental analysis contained in the PEIS, which is associated with publication of the five-year program, later steps in the offshore leasing and production process also require environmental evaluation under NEPA. For example, NEPA reviews are required at the pre-lease sale, exploration, and development and production stages. See Figure 1 for more information. Mitigation Strategy. The final program also BOEM stated that the process prescribed by the OCSLA for developing the five-year program largely

|

Like other recent five-year programs, the 2017-2022 program scheduled no lease sales for the Pacific region. No federal oil and gas lease sales have been held for the region since 1984, although some active leases with production remain in the Southern California planning area. Like the Atlantic region, the Pacific region was subject to congressional and presidential leasing moratoria for most of the past 30 years.116 Although these restrictions were lifted in FY2009, the governors of California, Oregon, and Washington continue to oppose offshore oil and gas leasing in the region.117

Role of Congress

Congress can influence the Administration's development of a five-year program in a number of ways. Members of Congress may convey their views on the Administration's proposal by submitting public comments on a draft program during the formal comment periods, or they may evaluate the program in committee oversight hearings. More directly, Members may introduce legislation to set or alter a program's terms. Congress pursued all these types of influence with respect to the proposed program for 2017-2022. Congress also has a role under the OCSLA of reviewing each five-year program once it is finalized, but the OCSLA does not require that Congress directly approve the final program in order for it to be implemented.

The 114th Congress pursued all these types of influence with respect to the proposed program for 2017-2022. The 115th Congress could also address the 2017-2022 program—for example, through legislation to alter its terms—or could choose not to do so.

Public Comment

Members of Congress, along with other stakeholders such as state governors, interested agencies and organizations, and members of the public, may submit comments on draft versions of five-year programs. For the 2017-2022 program, BOEM received 15 comments from Members of Congress on its initial request for information (RFI), 12 comments from Members on the DPP, and 5 comments from Members on the PP. Some of these comments came from one or a few Members, and others had many signers (in some cases, 150 Members or more).125118 Some comments opposed the inclusion of certain regions in the program, whereas others supported the proposed lease sales or sought an expansion of lease areas and a higher number of sales. The comments also addressed related issues such as seismic testing in the Atlantic.

BOEM takes the public comments into account when developing successive drafts of a five-year program. Each draft contains an appendix summarizing the substantive comments that BOEM received on the previous version, including those from Members of Congress, and explaining BOEM's response to each.126119 BOEM may revise the program to partially or fully adopt a suggestion, or may explain why it declined to do so.

Oversight Hearings

The House or Senate may hold oversight hearings to evaluate a proposed five-year oil and gas leasing program. Such hearings help to inform Members in their legislative decisionmaking concerning the program and provide an opportunity for BOEM to hear Members' views. After BOEM released the DPP for 2017-2022, the House Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on the program on April 15, 2015.127120 Members and witnesses addressed issues such as the overall number of lease sales proposed for the program, whether leasing should occur in the Atlantic and Arctic, and whether seismic surveying should occur in the Atlantic, among others. On May 19, 2016, the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on the PP version of the program.128121 Members and witnesses discussed, among other issues, the PP's proposal for targeted rather than area-wide lease sales in Alaska and the factors that contributed to BOEM's decision to remove its earlier-proposed Atlantic lease sale from the 2017-2022 program.

Under the OCSLA, the final version of each five-year program must be submitted to Congress for a period of 60 days before the Secretary of the Interior can approve and implement the program.122 However, Congress does not directly approve or disapprove the program during this period. Instead, either during or outside the 60-day period, Congress could introduce legislation to alter the program. Legislation could, for example, remove a scheduled lease sale, add a new lease sale, or make broader changes to the program.

The 114th, 115th, and 116th Congresses all have considered legislation to alter implementation of the 2017-2022 program. Proposals have included bills to add specific lease sales to the program or require a different set of lease sales, to require certain minimum numbers of acres to be leased, to prohibit leasing in certain OCS areas, to defund the planning program, and to prohibit any revisions to the program, among other topics. Such bills have not been enacted to date. Additional legislation could potentially be considered as implementation of the program continues.

Author Contact Information

Laura B. Comay, SpecialistLegislation

Through legislation, Congress may direct specific terms for an upcoming program or modify a program that is currently in effect. Legislation could, for example, remove a scheduled lease sale, add a new lease sale, or make broader changes to the program.

The 114th Congress considered legislation that would have affected the 2017-2022 program, including the following bills, none of which was enacted.129

- H.R. 1487 and S. 791 would have required the Secretary of the Interior to use an earlier-proposed Bush Administration draft program for 2010-2015 (which was not adopted)130 as the final oil and gas leasing program for the years FY2015-FY2020.131 This earlier-proposed program would have held 31 lease sales, although H.R. 1487 and S. 791 direct that 3 of them would not be part of the FY2015-FY2020 program. The bills also would have required BOEM to conduct, within a year of enactment, a previously proposed sale in the Atlantic region that was removed from the final 2012-2017 program. The bills would have further required that BOEM conduct a lease sale at least every 270 days for any OCS planning area for which there is a commercial interest in purchasing leases. Additionally, the bills would have declared the FY2015-FY2020 program to be approved under NEPA, with no further environmental review needed.

- H.R. 1663 would have deemed BOEM's DPP for 2017-2022 (the initial draft released in January 2015) to be approved by the Secretary as the final program and would have added lease sales to the program. Lease sales would have been added for the Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, and Bristol Bay in the Alaska region; for all previously leased areas off the coast of Virginia; and for any other OCS area estimated to contain more than 5 billion barrels of oil or 50 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The bill also would have declared the final program to be approved under NEPA. In addition, the bill contained other offshore provisions, such as state revenue-sharing provisions.

H.R. 3682 would have amended the OCSLA to provide, among other things, that BOEM five-year programs must make available for leasing at least 50% of the available unleased acreage in each OCS planning area considered to have the largest undiscovered technically recoverable oil and gas resources. It also would have provided that the programs must include any OCS planning area estimated to contain more than 2.5 billion barrels of oil or 7.5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. In addition, the bill would have required BOEM to develop its five-year programs with the specific goal of increasing production by at least 3 million barrels of oil per day and 10 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day by 2032. The bill also would have amended the OCSLA to allow the Secretary to add additional areas to an approved leasing program under certain conditions.BOEM would have been required to finalize a leasing program for 2016-2021 that complied with these provisions. BOEM also would have been required to conduct a specific previously proposed lease sale in the Atlantic region that was removed from the final 2012-2017 program, as well as lease sales off of South Carolina and Southern California. The bill contained other offshore energy provisions as well, such as those concerning revenue sharing with the states and the organization of the DOI ocean energy agencies.- H.R. 4749 would have directed the Secretary to conduct a lease sale off of North Carolina no later than two years after the bill's enactment, with subsequent lease sales in this area each year in the ensuing five-year period. The bill provided for military protections and revenue sharing with coastal states.

- S. 1276 and S. 2011 would have amended the OCSLA with the same requirements as in H.R. 3682 for BOEM to lease areas with the largest undiscovered technically recoverable resources, including areas with certain amounts of oil and gas, as described above. Additionally, the bills would have reduced the portion of the Eastern Gulf of Mexico that is under a congressional leasing moratorium and would have added Eastern Gulf lease sales to the 2017-2022 program. The bills also contained state revenue-sharing and other offshore energy provisions. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on S. 1276 on May 19, 2015, and reported S. 2011 on September 9, 2015.

- S. 1278 would have required BOEM to conduct lease sales in Alaska's Cook Inlet planning area and a portion of the Beaufort Sea planning area in FY2016 and each fiscal year thereafter. In addition, the bill would have required that each five-year leasing program include at least three lease sales in each of the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea planning areas. The bill also would have required BOEM to extend existing leases in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas to cover 20 years if the holder desires, and it would have required revenue sharing with the state of Alaska. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on S. 1278 on May 19, 2015.

- S. 1279 would have required the Secretary to include the South Atlantic planning area in the 2017-2022 program and to conduct one lease sale in that area during FY2021 and two during FY2022. The bill contained provisions addressing potential conflicts with military operations in the area, consultations with state governors, and geological and geophysical surveys of resources, among other matters. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on S. 1279 on May 19, 2015.

- S. 3203 would have required the Secretary to include, in a leasing program prepared for FY2017 through FY2023, two lease sales in the Beaufort planning area, two in the Chukchi planning area, and two in the Cook Inlet planning area. The bill also would have provided for increased revenue sharing with the state of Alaska and would have made certain changes to lease terms for the Alaska region. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on S. 3203 on September 22, 2016.

Review of Final Program

Under the OCSLA, the final version of each five-year program must be submitted to Congress for a period of 60 days before the Secretary of the Interior can approve and implement the program.132 However, Congress does not directly approve or disapprove the program during this period. Instead, either during or outside the 60-day period, Congress could introduce legislation to alter the program. For example, in the 112th Congress, during the 60-day review period for the current five-year leasing program (for 2012-2017), Representative Doc Hastings introduced H.R. 6082, which would have replaced the submitted program with a congressionally developed plan containing additional lease sales, including 13 sales in the Gulf of Mexico, 7 sales in the Alaska region, 6 sales in the Atlantic, and 3 sales in the Pacific. The bill passed the House but did not become law. As discussed above, bills under consideration in the 114th Congress would have made changes to the lease sale schedule for the 2017-2022 program. Legislation to alter the program could potentially be considered in the 115th Congress.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

43 U.S.C. §§1331-1356b. The leasing program requirements were added in a 1978 amendment (P.L. 95-372; 92 Stat. 629). |

||

| 2. |

43 U.S.C. §1344. U.S. waters comprise an area referred to as the outer continental shelf, or OCS (43 U.S.C. §1331(a)). The OCS is an area of submerged lands, subsoil, and seabed that lies between the outer seaward reaches of a state's jurisdiction and the outer seaward reaches of U.S. jurisdiction. |

||

| 3. |

The Secretary of the Interior must ensure, "to the maximum extent practicable," that the timing and location of leasing occurs so as to "obtain a proper balance between the potential for environmental damage, the potential for the discovery of oil and gas, and the potential for adverse impact on the coastal zone." 43 U.S.C. §1344(a)(3). |

||

| 4. |

Prior to 2010, the Secretary of the Interior delegated this responsibility to the Minerals Management Service, and then to the Service's successor agency, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEMRE). The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), one of three successor agencies to BOEMRE, has had the responsibility since a departmental reorganization in October 2012. |

||

| 5. |

Some areas of the OCS may be unavailable for leasing because of presidential or congressional leasing moratoria or other types of protection. |

||

| 6. |

43 U.S.C. §1344(d). Congress does not approve or reject the program during the review period, but congressional review may lead to separate legislative action. |

||

| 7. |

42 U.S.C. §4321. For more information on environmental impact statements, see CRS Report RL33152, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation, by Linda Luther. |

||

| 8. |

BOEM, 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing: Proposed Final Program, November 2016, at https://www.boem.gov/2017-2022-OCS-Oil-and-Gas-Leasing-PFP/, hereinafter cited as "2017-2022 PFP." Along with the PFP, BOEM released a final programmatic environmental impact statement for the 2017-2022 program. The final program is published under the title "proposed final program," or PFP, because it must be reviewed by Congress and the President and approved by the Secretary of the Interior. Given the approval of the program on January 17, 2017, this report typically refers to the PFP as the "final program," except in citations. |

||

| 9. |

DOI, Record of Decision and Approval of the 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, January 17, 2017, at https://www.boem.gov/2017-2022-Record-of-Decision/. |

||

| 10. |

BOEM, 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing: Proposed Program, March 2016, at http://www.boem.gov/2017-2022-Proposed-Program-Decision/, hereinafter referred to as "2017-2022 PP." |

||

| 11. |

BOEM, 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing: Draft Proposed Program, January 2015, at http://www.boem.gov/2017-2022-DPP/, hereinafter referred to as "2017-2022 DPP." |

||

| 12. |

|

||

| 13. |

This section was prepared by Adam Vann, Legislative Attorney. |

||

| 14. |

43 U.S.C. §§1301 et seq. |

||

| 15. |

|

||

| 16. |

43 U.S.C. § |

||

| 17. |

43 U.S.C. §1331(a). |

||

| 18. |

43 U.S.C. §1332(3). |

||

| 19. |

P.L. 95-372, §102 (43 U.S.C. §1802). |

||

| 20. | |||

| 21. |

43 U.S.C. §1344(a). |

||

| 22. | |||

| 23. |

P.L. 109-432.

|

||

|

For further discussion of this appropriations-based moratorium, see CRS Report RL33404, Offshore Oil and Gas Development: Legal Framework, by Adam Vann. |

|||

|

This section was prepared by Adam Vann, Legislative Attorney. |

|||

|

16 U.S.C. §§1451-1464. |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(a). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(a)(1). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(a)(4). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(b). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(c)(1). |

|||

|

Ibid. |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(c)(2). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(d)(1). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(d)(2). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1344(e). |

|||

|

30 C.F.R. §556.16(b). |

|||

|

43 U.S.C. §1332(2)(C). For more information on NEPA, see CRS Report RL33152, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation, by Linda Luther. |

|||

|

40 C.F.R. §1501.3(a). |

|||

|

Ibid. |

|||

|