FDA Regulation of Cannabidiol (CBD) Consumer Products: Overview and Considerations for Congress

Cannabidiol (CBD), a compound in the Cannabis sativa plant, has been promoted as a treatment for a range of conditions, including epileptic seizures, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, inflammation, and sleeplessness. However, limited scientific evidence is available to substantiate or disprove the efficacy of CBD in treating these conditions. In the United States, CBD is marketed in food and beverages, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)—products that are primarily regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA, 21 U.S.C. §§301 et seq.). CBD is also the active ingredient in Epidiolex, an FDA-approved pharmaceutical drug.

The Regulation of Marijuana and Hemp

CBD is derived from the Cannabis sativa plant (commonly referred to as cannabis), which includes both hemp and marijuana. Marijuana is a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA, 21 U.S.C. §§802 et seq.) and is regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Schedule I substances are subject to the most severe CSA restrictions and penalties. Except for purposes of federally approved research, it is a federal crime to grow, sell, or possess marijuana.

Until December 2018, hemp was included in the CSA definition of marijuana and was thus subject to the same restrictions. Legislative changes enacted as part of the 2018 farm bill (Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334) removed longstanding federal restrictions on the cultivation of hemp. No longer subject to regulation and oversight as a controlled substance by DEA, hemp production is now subject to regulation and oversight as an agricultural commodity by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The 2018 farm bill expanded the statutory definition of what constitutes hemp to include “all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers,” as long as it contains no more than a 0.3% concentration of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; 7 U.S.C. §1639o). All non-hemp cannabis and cannabis derivatives—including marijuana-derived CBD—are considered to be marijuana under the CSA and remain regulated by DEA.

Production and Marketing of Hemp Products

Legislative changes related to hemp enacted as part of the 2018 farm bill were widely expected to generate additional market opportunities for the U.S. hemp market. However, the farm bill explicitly preserved FDA’s authority under the FFDCA and Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA, 42 U.S.C. §262), including for hemp-derived products. Following enactment of the farm bill, in a December 2018 statement, FDA stated that it is “unlawful under the [FFDCA] to introduce food containing added CBD or THC into interstate commerce, or to market CBD or THC products as, or in, dietary supplements, regardless of whether the substances are hemp-derived.” The agency has maintained this view in subsequent communications.

Despite FDA’s determination, CBD continues to be widely marketed and sold in both food and dietary supplements in the United States. To date, FDA has generally prioritized enforcement against companies and products that pose the greatest risk to consumers—for example, CBD products claiming to treat Alzheimer’s or stop cancer cell growth.

In 2014, total U.S. CBD sales were a reported $108 million. In 2018, more than 1,000 companies produced and marketed CBD for the U.S. market, and U.S. CBD sales were estimated at $534 million, according to the Hemp Business Journal. That dollar amount is projected to exceed $1 billion in 2020 and to reach nearly $2 billion in 2022. This amount includes sales from hemp-derived CBD, marijuana-derived CBD (currently a Schedule I controlled substance), and pharmaceutical CBD (currently only Epidiolex).

Congressional Interest

Congress has expressed concern about the proliferation of CBD products marketed in violation of federal law and has called on FDA to provide guidance on lawful pathways for marketing hemp-derived CBD in food and dietary supplements. In absence of a regulatory framework for hemp-derived CBD, in the explanatory statement accompanying the FY2020 enacted appropriation, Congress directed FDA to issue a policy of enforcement discretion with respect to CBD products that meet the statutory definition of hemp. In addition to the activities directed in the explanatory statement, Congress could also take further legislative action in the future, such as requiring FDA to issue a regulation, under its FFDCA authorities, expressly permitting CBD that meets the definition of hemp to be used as a food additive or dietary supplement. Congress also could amend the FFDCA provisions that FDA has identified as restricting marketing of CBD in food and dietary supplements. In determining whether a legislative approach is appropriate, Congress may consider the potential for adverse health effects and other unintended consequences.

FDA Regulation of Cannabidiol (CBD) Consumer Products: Overview and Considerations for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- FDA Regulation of CBD Products

- Pharmaceutical Drugs

- Foods and Food Additives

- Animal Food and Feed Considerations

- Dietary Supplements

- Cosmetics and Personal Care Products

- Tobacco Products

- Alcohol Beverage Products

- Therapeutic Uses of CBD and Research Considerations

- Considerations for Congress: Marketing of CBD

- What Are the Circumstances Under Which FDA-Regulated Products Containing CBD Can Be Marketed Currently?

- What Is the Current State of the CBD Market?

- What Could Congress Do to Allow CBD to Be Marketed as a Food Additive or Dietary Supplement?

Figures

Tables

Summary

Cannabidiol (CBD), a compound in the Cannabis sativa plant, has been promoted as a treatment for a range of conditions, including epileptic seizures, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, inflammation, and sleeplessness. However, limited scientific evidence is available to substantiate or disprove the efficacy of CBD in treating these conditions. In the United States, CBD is marketed in food and beverages, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)—products that are primarily regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA, 21 U.S.C. §§301 et seq.). CBD is also the active ingredient in Epidiolex, an FDA-approved pharmaceutical drug.

The Regulation of Marijuana and Hemp

CBD is derived from the Cannabis sativa plant (commonly referred to as cannabis), which includes both hemp and marijuana. Marijuana is a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA, 21 U.S.C. §§802 et seq.) and is regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Schedule I substances are subject to the most severe CSA restrictions and penalties. Except for purposes of federally approved research, it is a federal crime to grow, sell, or possess marijuana.

Until December 2018, hemp was included in the CSA definition of marijuana and was thus subject to the same restrictions. Legislative changes enacted as part of the 2018 farm bill (Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334) removed longstanding federal restrictions on the cultivation of hemp. No longer subject to regulation and oversight as a controlled substance by DEA, hemp production is now subject to regulation and oversight as an agricultural commodity by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The 2018 farm bill expanded the statutory definition of what constitutes hemp to include "all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers," as long as it contains no more than a 0.3% concentration of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; 7 U.S.C. §1639o). All non-hemp cannabis and cannabis derivatives—including marijuana-derived CBD—are considered to be marijuana under the CSA and remain regulated by DEA.

Production and Marketing of Hemp Products

Legislative changes related to hemp enacted as part of the 2018 farm bill were widely expected to generate additional market opportunities for the U.S. hemp market. However, the farm bill explicitly preserved FDA's authority under the FFDCA and Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA, 42 U.S.C. §262), including for hemp-derived products. Following enactment of the farm bill, in a December 2018 statement, FDA stated that it is "unlawful under the [FFDCA] to introduce food containing added CBD or THC into interstate commerce, or to market CBD or THC products as, or in, dietary supplements, regardless of whether the substances are hemp-derived." The agency has maintained this view in subsequent communications.

Despite FDA's determination, CBD continues to be widely marketed and sold in both food and dietary supplements in the United States. To date, FDA has generally prioritized enforcement against companies and products that pose the greatest risk to consumers—for example, CBD products claiming to treat Alzheimer's or stop cancer cell growth.

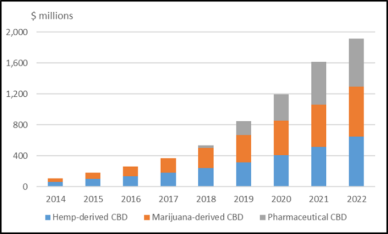

In 2014, total U.S. CBD sales were a reported $108 million. In 2018, more than 1,000 companies produced and marketed CBD for the U.S. market, and U.S. CBD sales were estimated at $534 million, according to the Hemp Business Journal. That dollar amount is projected to exceed $1 billion in 2020 and to reach nearly $2 billion in 2022. This amount includes sales from hemp-derived CBD, marijuana-derived CBD (currently a Schedule I controlled substance), and pharmaceutical CBD (currently only Epidiolex).

Congressional Interest

Congress has expressed concern about the proliferation of CBD products marketed in violation of federal law and has called on FDA to provide guidance on lawful pathways for marketing hemp-derived CBD in food and dietary supplements. In absence of a regulatory framework for hemp-derived CBD, in the explanatory statement accompanying the FY2020 enacted appropriation, Congress directed FDA to issue a policy of enforcement discretion with respect to CBD products that meet the statutory definition of hemp. In addition to the activities directed in the explanatory statement, Congress could also take further legislative action in the future, such as requiring FDA to issue a regulation, under its FFDCA authorities, expressly permitting CBD that meets the definition of hemp to be used as a food additive or dietary supplement. Congress also could amend the FFDCA provisions that FDA has identified as restricting marketing of CBD in food and dietary supplements. In determining whether a legislative approach is appropriate, Congress may consider the potential for adverse health effects and other unintended consequences.

Background

Cannabidiol (CBD), a compound in the Cannabis sativa plant, has been promoted as a treatment for a range of conditions, including epileptic seizures, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, inflammation, and sleeplessness. However, limited scientific evidence exists to substantiate or disprove the efficacy of CBD in treating these conditions. In the United States, CBD is being marketed in food and beverages, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS, the overarching term encompassing electronic cigarettes)—products that are primarily regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). CBD is also the active ingredient in Epidiolex, an FDA-approved pharmaceutical drug used to treat seizures associated with two rare and severe forms of epilepsy.

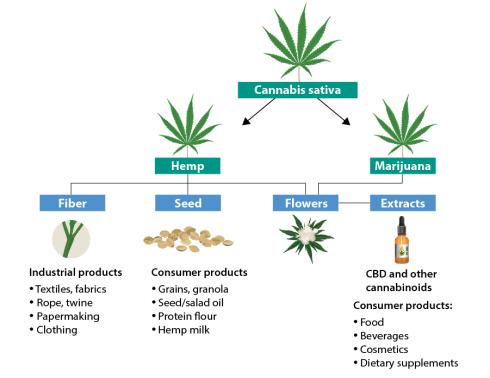

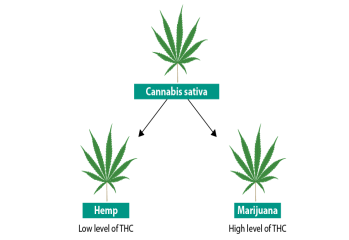

CBD is derived from the Cannabis sativa plant (commonly referred to as cannabis), which includes both hemp and marijuana (defined further below). CBD and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are thought to be the most abundant cannabinoids in the cannabis plant and are among the most researched cannabinoids for their potential medical value.1 THC—a psychoactive2 compound—is found at high levels in marijuana and low levels in hemp (see Figure 1).3

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Notes: This figure is intended to provide a high-level illustration of the relationship between cannabis, marijuana, and hemp, per the statutory distinction in the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). |

CBD, on the other hand, is generally considered to be nonpsychoactive and may be derived from either hemp or marijuana. As described below, this distinction is relevant for purposes of oversight by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), but generally not for FDA oversight. FDA has stated that it "treats products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds as it does any other FDA-regulated products—meaning they're subject to the same authorities and requirements as FDA-regulated products containing any other [non-cannabis] substance.4 This is true regardless of whether the cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds are classified as hemp under [7 U.S.C. Section 1639o] as amended by the 2018 [f]arm [b]ill."5 In contrast, the DEA does not regulate cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds that meet the statutory definition of hemp.

Botanically, marijuana and hemp are from the same species of plant, Cannabis sativa, but from different varieties or cultivars.6 Marijuana and hemp have separate definitions in U.S. law and are subject to different statutory and regulatory requirements.

Marijuana (as defined in statute) generally refers to the cultivated plant used as a psychotropic drug, either for medicinal or recreational purposes.7 Marijuana is a Schedule I controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA)8 and is regulated by DEA. Schedule I substances are subject to the most severe CSA restrictions and penalties; with exceptions for federally approved research, it is a federal crime to grow, sell, or possess the drug. Thus, under the CSA, the unauthorized manufacture, distribution, dispensation, and possession of marijuana and its derivatives (including marijuana-derived CBD) are prohibited.9

Hemp (as defined in statute separately from marijuana), on the other hand, may be legally cultivated under federal law, subject to oversight by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).10 Hemp is generally grown for use in the production of a wide range of products, including foods and beverages, personal care products, dietary supplements, fabrics and textiles, paper, construction materials, and other manufactured and industrial goods (see Figure 2).

Until December 2018, hemp was included in the CSA definition of marijuana and was thus subject to the same restrictions as marijuana. The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 farm bill; P.L. 115-334) removed hemp and its derivatives (including hemp-derived CBD) from the CSA definition of marijuana. As a result, hemp is no longer subject to regulation and oversight as a controlled substance by DEA. Instead, hemp production is now subject to regulation and oversight as an agricultural commodity by USDA. CBD and CBD-related products that do not meet the statutory definition of hemp (in 7 U.S.C. §1639o) continue to be prohibited (aside from lawful use for research purposes) under the CSA and remain regulated by DEA.

|

Related CRS Products CRS In Focus IF11250, FDA Regulation of Cannabidiol (CBD) Products CRS Report R44742, Defining Hemp: A Fact Sheet CRS In Focus IF10391, Hemp-Derived Cannabidiol (CBD) and Related Hemp Extracts CRS Report R44782, The Marijuana Policy Gap and the Path Forward Congressional Distribution memo on cannabis extraction methods is available to Congressional clients upon request |

Changes enacted in the 2018 farm bill related to hemp were expected by many to generate additional market opportunities for hemp-derived consumer products such as hemp-derived CBD. However, the farm bill also explicitly preserved FDA's authorities under the FFDCA and Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act, including for hemp-derived products.11 As mentioned above, cannabis and cannabis-derived FDA-regulated products are subject to the same authorities and requirements as FDA-regulated products—including pharmaceutical drugs, food, dietary supplements, and cosmetics—containing any other substance (whether cannabis-derived or otherwise). As described below, FDA has determined that it is unlawful to introduce food containing added CBD into interstate commerce, or to market CBD as or in dietary supplements.12 FDA has not made similar determinations for other FDA-regulated product categories (pharmaceutical drugs, cosmetics, and tobacco products).

FDA Regulation of CBD Products

In the United States, CBD is the active ingredient in the prescription drug Epidiolex. CBD is also being marketed in food and beverages, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products such as ENDS. Each of these product types is governed by different statutory and regulatory requirements, primarily administered by FDA. The agency also shares regulatory authority with other entities; for example, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), 13 with regard to alcoholic beverages, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), with regard to the advertising and promotion of certain CBD products. This section provides an overview of how FDA regulates drugs, food, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products, and the applicability of those requirements to products that contain CBD. Table 1 summarizes selected regulatory requirements by CBD product type.

Pharmaceutical Drugs

FDA, under the FFDCA, regulates the safety and effectiveness of prescription and nonprescription (over-the-counter, or OTC) drugs sold in the United States. Prescription drugs require health practitioner supervision to be considered safe for use—due to drug toxicity, potential harmful effect, or method of use—and may be dispensed only pursuant to a prescription.14 In contrast, OTC drugs may be used without a prescriber's authorization, provided they have an acceptable safety margin, low potential for misuse or abuse, and are adequately labeled so that consumers can self-diagnose the condition, self-select the medication, and self-manage the condition.15 The statutory definition of the term drug includes "articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals" and "articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals."16 In general, a new drug may not be introduced into interstate commerce without FDA approval.17

For purposes of new drug approval, except under very limited circumstances, FDA requires data from clinical trials to provide evidence of a drug's safety and effectiveness. Before testing in humans—called clinical testing—the drug's sponsor (usually its manufacturer) must file an investigational new drug (IND) application with FDA. Once a manufacturer completes clinical trials, it submits the results of those investigations, along with other information, to FDA in a new drug application (NDA).18 In reviewing an NDA, FDA considers whether the drug is safe and effective for its intended use; whether the proposed labeling is appropriate; and whether the methods used to manufacture the drug and the controls used to maintain the drug's quality are adequate to preserve the drug's identity, strength, quality, and purity.19 The NDA process can be used to obtain approval of both prescription and OTC drugs. If a sponsor wants to transfer an approved drug from prescription to OTC status (called an Rx-to-OTC switch), the sponsor must submit to FDA an NDA (or a supplement20 to an NDA) providing data to support the switch.21 As part of an NDA for an OTC drug, FDA may require the sponsor to conduct label comprehension studies assessing the extent to which consumers understand the information in the proposed labeling.22 FDA also may recommend that the sponsor conduct self-selection studies to assess whether consumers can appropriately self-select a drug based on the information on the labeling.23

In June 2018, FDA approved an NDA for the prescription drug Epidiolex, submitted by GW Pharmaceuticals, for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome in patients two years old and older.24 The active ingredient in Epidiolex is CBD, although its mechanism of action—that is, the mechanism by which it exerts its anticonvulsant effects—is not known.25 FDA approved Epidiolex in June 2018; at that time, the drug contained a chemical constituent of marijuana (CBD) that was considered a Schedule I controlled substance.26 Therefore, it could not be marketed unless rescheduled by the DEA. Upon FDA approval, Epidiolex no longer met the criteria for placement in Schedule I, as it now had an accepted medical use in the United States.27 On September 28, 2018, based on a recommendation from FDA, DEA issued an order placing FDA-approved drugs that contain cannabis-derived CBD and no more than 0.1% THC in Schedule V.28 Epidiolex is available by prescription and only at specialty pharmacies.29 It is the first (and only) pharmaceutical formulation of highly purified, plant-derived CBD available in the United States.30 Because Epidiolex is designated as an orphan drug (i.e., a drug that treats a rare disease or condition), it was awarded seven years of marketing exclusivity upon approval.31 This means that FDA cannot approve an NDA for the same drug—in this case, one that has CBD as its active ingredient—for the same disease or condition (i.e., for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients two years old and older) for seven years, with limited exceptions.32

Foods and Food Additives

The FFDCA defines food to mean "(1) articles used for food or drink for man or other animals, (2) chewing gum, and (3) articles used for components of any such article."33 FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) is responsible for oversight of human food, while FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) is responsible for oversight of animal food (feed). The FFDCA requires that all human and animal foods are safe to eat, produced in compliance with current good manufacturing practices (CGMPS), contain no harmful substances, and are truthfully labeled, among other things.34 Generally, food intended for human or animal consumption is not approved by FDA prior to marketing. However, any substance added to food is a food additive, subject to premarket review and approval by FDA.35 An exception to this is if a substance is generally recognized as safe (i.e., GRAS) under the conditions of its intended use, among qualified experts, or unless the use of the substance is otherwise excepted from the definition of a food additive.36 To obtain approval of a substance as a food additive, a person may submit to FDA a food additive petition, which proposes the issuance of a regulation prescribing the conditions under which the additive may be safely used.37 Food additives are approved for specific uses (e.g., to improve taste, texture, or appearance; to improve or maintain nutritional value; or to maintain or improve safety and freshness).38 If FDA determines, after reviewing the data submitted in a petition, that a proposed use of a food additive is safe, the agency issues a regulation authorizing that specific use of the substance.

The use of a food substance may be determined to be GRAS either through scientific procedures or, for a substance used in food before 1958, through scientific procedures or experience based on common use in food.39 FDA established a voluntary GRAS notification process that permits any person to notify the agency of a conclusion that a substance is GRAS under the conditions of its intended use in human food.40 A substance is considered GRAS on the basis of common knowledge about its safety for its intended use, and the data and information relied upon for the GRAS substance must be generally available.41 This is in contrast to the data and information used to support a food additive petition, which are generally privately held and submitted to FDA for evaluation. Additional information about the food additive petition process and submission of GRAS notifications is available in Appendix A.

Under the FFDCA, it is unlawful to introduce into interstate commerce a food (human or animal) to which a drug has been added—either an approved drug or a drug for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted and made public.42 There are several exceptions to this: (1) if the drug was marketed in food before it was approved as a drug or before clinical drug investigations were instituted; (2) if the Secretary has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, approving the use of such drug in the food; (3) if the use of the drug in the food is to enhance the safety of the food and not to have independent biological or therapeutic effects on humans, and the use is in conformity with specified requirements; or (4) if the drug is a new animal drug whose use is not unsafe under FFDCA Section 512.43 FDA has concluded, based on available evidence, that none of these are the case for CBD, and because CBD is an active ingredient in an approved drug, FDA has taken the position that it is unlawful to introduce into interstate commerce food containing added CBD (i.e., to use CBD as a food additive).44

However, according to FDA, cannabis-derived ingredients that do not contain CBD (or THC) may fall outside the scope of this prohibition.45 Foods containing parts of the hemp plant that include only trace amounts of CBD (e.g., hemp seed and ingredients derived from hemp seed) may be lawfully marketed under certain circumstances—pursuant to FDA approval as a food additive or a GRAS determination. In December 2018, FDA announced that it had completed its evaluation of three GRAS notices related to hemp seed-derived ingredients (i.e., hulled hemp seeds, hemp seed protein, and hemp seed oil).46 FDA had no questions regarding the company's conclusion that the use of such products as described in the notices is safe. Thus, FDA allowed them to be marketed in human foods—without food additive approval—for the uses specified in the GRAS notices, provided they comply with all other applicable requirements. Intended uses of the hemp seed-derived ingredients include adding them as a source of protein, carbohydrates, oil, and other nutrients to beverages (e.g., smoothies, protein drinks, and plant-based alternatives to dairy products), as well as to soups, dressings, baked goods, snacks, and nutrition bars.

While FDA has determined that it is unlawful to introduce into interstate commerce food to which CBD has been added, independent of CBD's status as a drug ingredient, CBD has not been approved as a food additive. FDA also has determined that "[b]ased on a lack of scientific information supporting the safety of CBD in food … it cannot conclude that CBD is [GRAS] among qualified experts for its use in human or animal food."47

Animal Food and Feed Considerations

As previously noted, the FFDCA definition of food includes animal food. Similar to food intended for human consumption, animal food is not subject to premarket approval by FDA unless it meets the definition of a food additive. In that case, it would be subject to the premarket requirements for food additives (or GRAS exemption). Depending on the claims made, certain animal feed/food may meet the FFDCA definition of a drug.48 Like human drugs, animal drugs require FDA approval prior to marketing.49 In some cases, animal food may be considered both a food and a drug simultaneously.50 Although premarket approval by FDA is not required for most animal food (excluding animal drugs), other federal and state rules govern their manufacture and sale. These include, for example, labeling requirements and ingredient definitions.51

As previously noted, it is a prohibited act, with certain exceptions, under the FFDCA to introduce into interstate commerce animal food to which a drug has been added—either an approved drug or a drug for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted and made public.52 Some cannabis-derived ingredients that do not contain CBD or contain only trace amounts of CBD (e.g., hemp seed and ingredients derived from hemp seed) may fall outside the scope of this prohibition and may be lawfully marketed pursuant to FDA approval as a food additive or a GRAS determination.53 However, to date, FDA has not approved any food additive petitions or evaluated any GRAS notices related to use of hemp seed and hemp-seed derived ingredients in animal food.54 In addition, as previously mentioned, FDA has stated that "[b]ased on a lack of scientific information supporting the safety of CBD in food … it cannot conclude that CBD is [GRAS] among qualified experts for its use in human or animal food."55

While FDA is the primary federal agency responsible for regulating the safety of food, the agency works with states and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) in the implementation of uniform policies for regulating the use of animal food products. For example, FDA provides scientific and technical assistance to the AAFCO ingredient Definition Request Process, the purpose of which is to "identify the safety, utility, and identity of ingredients used in animal feed."56 CVM recognizes ingredients listed in the Official Publication of the AAFCO as being acceptable for use in animal food. According to FDA, "there are no approved food additive petitions or ingredient definitions listed in the AAFCO OP for any substances derived from hemp, and we are unaware of any GRAS conclusions regarding the use of any substances derived from hemp in animal food."57 AAFCO has issued guidelines on hemp in animal food, which are generally consistent with FDA's policy.58 The guidelines also note that, based on discussions with FDA and the hemp industry,

materials and products that are CBD-infused need to be treated as drugs because the intended uses are largely associated with drug claims. This means that parts of the hemp plant will not be appropriate for approval as an animal feed ingredient. As such, products that contain CBD as a feed ingredient could be labeled adulterated or misbranded and be subject to regulatory actions by state agencies.59

Dietary Supplements

A dietary supplement is defined as a product (other than tobacco) that

- is intended to supplement the diet;

- is intended to be taken by mouth as a pill, capsule, powder, tablet, or liquid; and

- contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients: vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanicals, amino acids, and other substances or their constituents.60

Dietary supplements are generally regulated as food under the FFDCA61 and, as such, are not subject to premarket approval. Dietary supplements must comply with FDA's regulations prescribing CGMPs related to manufacturing, packaging, labeling, or holding dietary supplements to ensure their quality.62 A dietary supplement may not claim to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent a specific disease or class of diseases.63

FDA does not evaluate the safety and effectiveness of dietary supplements prior to marketing; however, supplements are subject to various statutory and regulatory requirements. Among other things, a firm that seeks to market a dietary supplement containing a new dietary ingredient (NDI) must notify FDA at least 75 days prior to marketing. The manufacturer or distributor of the dietary supplement that contains an NDI subject to the notification requirements may not market the supplement until 75 days after the filing date.64 An NDI is defined as a dietary ingredient that was not marketed as a dietary supplement in the United States before October 15, 1994.65 An exception to the NDI notification requirement is if the dietary ingredient was "present in the food supply as an article used for food in a form in which the food has not been chemically altered."66 In this case, the dietary ingredient would still be considered an NDI because it was not marketed prior to October 15, 1994, but it would be exempt from the notification requirement.67 An NDI notification must include a "history of use or other evidence of safety establishing that the dietary ingredient, when used under the conditions recommended or suggested in the labeling of the dietary supplement, will reasonably be expected to be safe," along with other information.68 FDA acknowledges receipt of the NDI notification and notifies the submitter of the date of receipt, which is also the NDI notification filing date. FDA must keep the information in the NDI notification confidential for the first 90 days after receiving it.69 If the manufacturer or distributor submits additional information in support of the NDI notification, FDA may reset the 75-day period and assign a new filing date.70 FDA does not approve NDI notifications. Instead, the agency generally issues one of four response letters: (1) a letter of acknowledgment without objection; (2) a letter listing deficiencies that make the notification incomplete; (3) an objection letter raising safety concerns based on information in the notification or identifying gaps in the history of use or other evidence of safety; or (4) a letter raising other regulatory issues with the NDI or dietary supplement (e.g., the NDI or supplement is excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement).71

Under the FFDCA, an article that is an active ingredient in an approved drug, or that has been authorized for investigation as a new drug and for which the existence of such clinical investigations has been made public, is excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement and may not be marketed as such.72 An exception to this is if FDA issues a regulation finding that the use of such substance in a dietary supplement is lawful. An article that is approved as a drug or being investigated as a drug may be marketed in or as a dietary supplement if it was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food prior to approval or clinical investigation (before the IND became effective).73 According to FDA, CBD is an active ingredient in an FDA-approved drug (i.e., Epidiolex), and it was authorized for investigation as a new drug for which substantial clinical investigations had been instituted and made public before its marketing as a dietary supplement. As such, FDA has determined that CBD may not be sold as a dietary supplement unless FDA promulgates regulations concluding otherwise, regardless of whether the CBD is hemp-derived or marijuana-derived.74 FDA has issued several public statements maintaining that it is unlawful to market CBD as, or in, dietary supplements.75

FDA may issue a regulation, after notice and comment, creating an exception that allows CBD to be marketed as a dietary supplement.76 Such a regulation may be requested by an interested person through the filing of a citizen petition.77 If an interested party has evidence challenging FDA's conclusion excluding CBD from the dietary supplement definition, the party may submit to FDA a citizen petition asking the agency to issue a regulation, subject to notice and comment, finding that the ingredient, when used as or in a dietary supplement, would be lawful. To date, FDA has not issued such a regulation for any substance (whether cannabis-derived or not) that is an active ingredient in an approved drug or is authorized for investigation as a new drug.78 If FDA were to issue a regulation allowing CBD to be marketed as a dietary supplement, that product likely would be expected to comply with the various requirements governing lawful marketing of supplements, including compliance with CGMPs and NDI notification. Despite FDA's determination that marketing CBD as a dietary supplement is unlawful, these products remain on the market.

On November 14, 2019, the Consumer Healthcare Products Association (CHPA) submitted a citizen petition to FDA, asking the agency to "exercise its statutory authority and discretion to engage in rulemaking that establishes a regulatory pathway to legally market dietary supplements containing [CBD] derived from hemp (as defined in 7 U.S.C. §1639o(1))" and to require that manufacturers of CBD-containing dietary supplements submit NDI notifications.79 It is unclear whether other citizen petitions have been submitted to FDA requesting that it issue a regulation allowing CBD to be marketed as a dietary supplement.

Cosmetics and Personal Care Products

The FFDCA defines cosmetics as "(1) articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body or any part thereof for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance and (2) articles intended for use as a component of any such articles; except that such term shall not include soap."80 FDA has the authority to take certain enforcement action against adulterated or misbranded cosmetics. A cosmetic is deemed adulterated if, among other things, it contains a poisonous or deleterious substance, or if it has been made or held in unsanitary conditions.81 A cosmetic is deemed misbranded if, among other things, "its labeling is false or misleading in any particular," or if the label lacks required information.82 In addition, if a product makes therapeutic claims (i.e., that its intended use is the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of a disease), FDA generally considers that product to be a drug (or a drug-cosmetic) and subject to the FFDCA drug requirements. If a company has not obtained approval of a new drug prior to marketing, it is in violation of the FFDCA. For example, in October 2019, FDA sent a warning letter to a manufacturer marketing a CBD body butter with therapeutic claims.83

However, FDA's authority over cosmetic products is generally more limited than for the other products that the agency regulates. FDA does not have the authority to conduct premarket review of cosmetic ingredients, nor can FDA require cosmetics manufacturers to submit data substantiating the safety of their cosmetics. While FDA regulations prohibit or restrict the use of certain ingredients in cosmetics, the regulations do not apply to any cannabis or cannabis-derived ingredients (e.g., CBD).84

Legislation has been introduced in the 116th Congress that would expand FDA's authority to regulate cosmetic products and would require a safety review of certain ingredients, among other things.85 If CBD were included in such a review and found to be unsafe for use in cosmetics, that finding would likely affect whether CBD could be marketed in cosmetics.

Tobacco Products

FDA regulates the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products, per its authorities in the FFDCA, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (TCA; P.L. 111-31). A tobacco product is defined as "any product made or derived from tobacco that is intended for human consumption, including any component, part, or accessory of a tobacco product (except for raw materials other than tobacco used in manufacturing a component, part, or accessory of a tobacco product)" that is not a drug, device, or drug-device combination product.86 Nicotine is an addictive chemical compound present in the tobacco plant. Tobacco products—including cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, hookah tobacco, and most ENDS—contain nicotine.87 Tobacco-derived nicotine (as well as any other tobacco-derived compound) meets the statutory definition of a tobacco product.88

In 2016, FDA promulgated regulations (known as the deeming rule)89 that extend authority over all products meeting the definition of a tobacco product that were not already subject to the FFDCA, including ENDS. In the deeming rule, FDA clarified its authority to regulate all components and parts associated with ENDS, including e-liquids. E-liquids, which can include nicotine, flavorings, and other ingredients, are heated in ENDS to create a vapor that a user inhales. If an e-liquid contains CBD and makes therapeutic claims, it may be considered an unapproved drug and may be in violation of the FFDCA. In addition, if an e-liquid contains any tobacco-derived compound (e.g., nicotine) and CBD, but does not make therapeutic claims for CBD, the product may still meet the statutory definition of a tobacco product because it includes tobacco-derived compounds. In such case, the product may be subject to FDA's tobacco regulatory authorities, although the product might not receive marketing authorization if it is determined that allowing the product to be marketed would not be appropriate for the protection of public health.90 However, if the e-liquid contains CBD only, with no tobacco-derived compounds, and does not make therapeutic claims, FDA's enforcement options might be limited. In this case, it would be unclear whether the product meets the statutory definition of a tobacco product and is therefore subject to FDA's tobacco regulatory authorities. FDA has stated that it intends to make a determination about regulating such products as tobacco products on a case-by-case basis.91

|

Requirements |

Pharmaceutical Drugs |

Foods and Food Additives |

Dietary Supplements |

Cosmetic Products |

Tobacco Products |

|

Example |

Epidiolex |

CBD-infused honey |

CBD oil |

Body lotion |

E-liquid |

|

Facility registration |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §360; 21 C.F.R. Part 207] |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §350d; 21 C.F.R. Part 1 Subpart H] |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §350d; 21 C.F.R. Part 1 Subpart H] |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387e] |

|

Product listing |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §360(j); 21 C.F.R. Part 207] |

No |

No |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387e(i)] |

|

Premarket review |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §355(a)] |

Noa |

No |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387j]b |

|

Compliance with CGMPs |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §351(a)(2)(B); 21 C.F.R. Part 210 and 211] |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §342(a); 21 C.F.R. Part 110] |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §342(g); 21 C.F.R. Part 111] |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387f(e); regulations not promulgated yet] |

|

Adverse event reporting |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §355(k); 21 C.F.R. §314.80] |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §379aa-1] |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387i(a)] |

|

Mandatory recall authority |

No (with the exception of controlled substancesc) |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §350l] |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §350l] |

No |

Yes [21 U.S.C. §387h(c)] |

|

Adulteration provisions |

21 U.S.C. §351 |

21 U.S.C. §342 |

21 U.S.C. §342; 21 U.S.C. §350b |

21 U.S.C. §361 |

21 U.S.C. §387b |

|

Misbranding provisions |

21 U.S.C. §352 |

21 U.S.C. §343 |

21 U.S.C. §343 |

21 U.S.C. §362 |

21 U.S.C. §387c |

Source: Table created by CRS based on 21 U.S.C. §§301 et. seq.

a. Food is generally not approved by FDA prior to marketing. However, food additives are subject to premarket review and approval by FDA unless generally recognized as safe (i.e., GRAS).

b. FDA has delayed enforcement of premarket review requirements for certain tobacco products—including ENDS—providing manufacturers more time to prepare for the review process. Accordingly, manufacturers may soon need to obtain FDA authorization for such products to remain on the market, or risk enforcement action.

c. In general, FDA does not have mandatory recall authority over drugs. Instead, FDA can ask a manufacturer to voluntarily recall a drug. However, the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (P.L. 115-271; the SUPPORT Act) authorized FDA to order a mandatory recall for a controlled substance that presents a public health risk [21 U.S.C. §360bbb–8d].

Alcohol Beverage Products

While TTB is the primary federal regulator of alcoholic beverages, FDA plays a role in determining what ingredients may be used in the production of alcoholic beverages. In general, before a hemp ingredient may be used in the production of an alcohol beverage product—whether it be a distilled spirit, wine, or beer—the producer may be required to request formula approval from TTB. Requirements are outlined in the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (27 U.S.C. §201 et seq.) and in regulation.92 For distilled spirits, for example, an approved formula is required to "blend, mix, purify, refine, compound, or treat spirits in a manner which results in a change of character, composition, class or type of the spirits;" any change in an approved formula requires a new filing.93 For wine, formula approval is required for "special natural wine, agricultural wine, and other than standard wine (except distilling material or vinegar stock)."94 For beer, formula approval is required for any fermented product that "is not generally recognized as a traditional process in the production of a fermented beverage designated as 'beer,' 'ale,' 'porter,' 'stout,' 'lager,' or 'malt liquor'" or to which certain ingredients are added.95 Specific labeling requirements also apply, and generally require prior approval.96 In addition, regarding interstate and foreign commerce in spirits, wine, and beer, it is unlawful for businesses to operate without a permit.97 Certain states and local jurisdictions might also have their own alcohol product prohibitions and production requirements, as well as restrictions on interstate commerce.

TTB's current policy is that the agency "will not approve any formulas for alcohol beverages that contain ingredients that are controlled substances under the CSA" (e.g., marijuana or marijuana-derived CBD).98 With regard to CBD derived from hemp, TTB is in the process of updating its guidance on the use of hemp ingredients to reflect changes in the 2018 farm bill. TTB also states that it consults with FDA on ingredient safety issues and, in some cases, may "require formula applicants to obtain documentation from FDA indicating that the proposed use of an ingredient in an alcohol beverage would not violate [FFDCA]."99 Thus, in general, TTB treats hemp-derived ingredients for alcohol beverage products as any other product ingredient. As such, any ingredients added to alcohol beverage products must be either an FDA-approved food additive or determined to be GRAS. As aforementioned, to date, FDA has evaluated GRAS determinations for three different hemp seed-derived ingredients that do not contain CBD, although allowed uses do not include addition to alcoholic beverages.100 With regard to CBD, FDA has determined that it is unlawful to introduce into interstate commerce food to which certain drug ingredients (e.g., CBD) have been added. Additionally, independent of CBD's status as a drug ingredient, CBD has not been approved as a food additive, and FDA has determined that "[b]ased on a lack of scientific information supporting the safety of CBD in food … it cannot conclude that CBD is [GRAS] among qualified experts for its use in human or animal food."101

Formulations seeking approval to use other types of hemp extracts as an ingredient—including but not limited to CBD—would likely not be approved by TTB, since these extracts have not been authorized for use in food by FDA.102

Therapeutic Uses of CBD and Research Considerations

Cannabinoids such THC and CBD interact with specific cell receptors in the brain and throughout the body to produce their intended effects. Although THC activates certain receptors that then produce euphoric or intoxicating effects,103 CBD has low affinity for those same receptors and therefore does not produce intoxicating effects.104 This property may make CBD an attractive compound for drug developers. In addition, preclinical (e.g., animal model) research suggests that CBD may interact with other brain-signaling systems that can produce therapeutic effects, such as the reduction of seizures, pain, and anxiety.105

The therapeutic benefits, or underlying mechanism of action for therapeutic benefits, of CBD remain uncertain, even in CBD-containing drugs that have been approved by regulatory agencies. For example, in the United States, GW Pharmaceuticals' Epidiolex (CBD) is approved for the treatment of seizures associated with two rare and severe forms of epilepsy. However, according to the drug's labeling, the mechanism by which the drug exerts its anticonvulsant effects is not known.106 In addition, while not yet approved in the United States, GW Pharmaceuticals' drug Sativex (nabiximols)—a cannabis extract spray containing a 1:1 ratio of CBD and delta-9 THC—has regulatory approval in more than 25 countries for the treatment of spasticity (muscle stiffness/spasm) due to multiple sclerosis (MS).107 In Canada, Sativex has conditional marketing authorization as an adjunctive treatment for neuropathic pain in adult patients with MS and "as adjunctive analgesic [pain relieving] treatment in adult patients with advanced cancer who experience moderate to severe pain during the highest tolerated dose of strong opioid therapy for persistent background pain."108 However, Phase III clinical trials previously conducted by GW Pharmaceuticals found that Sativex failed to show superiority over placebo in treating the pain of patients with advanced cancer who experience inadequate analgesia during optimized chronic opioid therapy.109 Furthermore, while CBD is predicted to have anti-inflammatory properties, which may play a role in its analgesic effects, preliminary evidence suggests that the analgesia is mediated by THC, and the extent to which CBD contributes to those therapeutic effects is unclear.110

CBD is the subject of numerous ongoing randomized controlled trials (RCTs).111 As of December 2019, a database maintained by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) lists numerous domestic and international ongoing RCTs involving cannabinoids—including CBD—as a treatment for a variety of conditions, including chronic pain, tremors associated with Parkinson's disease, and anxiety.112 GW Pharmaceuticals is also studying CBD and CBD variants in clinical trials for autism and schizophrenia.113 Other pharmaceutical manufacturers are conducting clinical trials with CBD and its variants for other indications, including severe acne and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).114 However, until such studies are completed, conclusive evidence supporting the use of CBD to treat various health conditions is limited.

In February 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a comprehensive review of fair- and good-quality systematic reviews of literature and high-quality primary research on cannabis and cannabinoids.115 NASEM did not make specific comparisons between cannabinoids derived from hemp versus marijuana, or between cannabinoids from low versus high THC strains of marijuana. However, for CBD or CBD-enriched cannabis specifically, the report noted research gaps among existing literature in treating numerous conditions, including cancer in general, chemotherapy-induced nausea, epilepsy, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other conditions.116 Nonetheless, CBD is promoted as treatment for a range of conditions, including PTSD, anxiety, inflammation, and sleeplessness—despite limited scientific evidence substantiating or disproving these claims.117

These research gaps can be attributed, in part, to the status of marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance under the CSA. Individuals who seek to conduct research on any controlled substance must do so in accordance with the CSA and other federal laws.118 DEA research requirements are more stringent for Schedule I and Schedule II substances than for substances in Schedules III-V. For example, for Schedule I substances such as marijuana, even if practitioners have a DEA registration for a substance in Schedules II-V, they must obtain a separate DEA registration for researching a Schedule I substance. In addition, due to its Schedule I status, the DEA strictly limits the quantity of marijuana manufactured each year. These requirements can prolong the process of acquiring marijuana (including marijuana-derived CBD) for research. As mentioned previously, the 2018 farm bill removed hemp and hemp derivatives (including hemp-derived CBD) from the CSA definition of marijuana, making them no longer subject to regulation and oversight as a controlled substance by DEA. DEA has confirmed that a DEA registration is no longer required to grow or research hemp plants and CBD preparations that meet the statutory definition of hemp.119 However, CBD preparations containing above the 0.3% delta-9 THC level (i.e., meeting the statutory definition of marijuana) continue to be subject to Schedule I CSA requirements. As a result, conducting research on these substances may continue to be a challenge.120

Considerations for Congress: Marketing of CBD

What Are the Circumstances Under Which FDA-Regulated Products Containing CBD Can Be Marketed Currently?

As mentioned previously, FDA has determined that at this time, CBD cannot be added to any food that is sold in interstate commerce and that CBD cannot be marketed as a dietary supplement. Although FDA could issue a regulation allowing CBD to be added to food or allowing its use in dietary supplements, the agency has never issued such a regulation for any substance (whether cannabis-derived or not) that is an approved drug or authorized for investigation as a new drug.121 Although FDA has determined that CBD (and THC) may not be added to food or marketed as a dietary supplement, the agency has not made this same determination for other compounds derived from cannabis, although those compounds may be subject to DEA restrictions; FDA's determination is specific to CBD and THC because both are active ingredients in FDA-approved drugs.122 FDA also has not determined that CBD may not be added to cosmetics;123 however, if a CBD-containing cosmetic product makes therapeutic claims (e.g., that it is intended to diagnose, treat, cure, mitigate, or prevent a disease), FDA would likely consider the product to be a drug subject to the new drug approval requirements.

CBD may be lawfully marketed as a drug, pursuant to FDA approval, and in compliance with applicable statutory and regulatory requirements. If a firm seeks to market CBD as a treatment or an otherwise therapeutic product, the firm generally would need to obtain premarket approval from FDA via the new drug approval pathway. To date, FDA has approved one CBD-containing drug, Epidiolex, which is available by prescription for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients two years old and older. Epidiolex is marketed by GW Pharmaceuticals.

On May 31, 2019, FDA held a public hearing "to obtain scientific data and information about the safety, manufacturing, product quality, marketing, labeling, and sale of products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds."124 Prior to the hearing, FDA had opened a docket to which interested stakeholders could submit a request for FDA to review scientific data and information about products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds.125 Although FDA has maintained that it is unlawful to add CBD to food or to market CBD as a dietary supplement, CBD continues to be marketed in violation of this determination. The agency has generally prioritized enforcement against companies and products that pose the greatest risk to consumers—for example, products making claims that CBD can treat Alzheimer's or stop cancer cell growth.126 FDA has said that it "does not have a policy of enforcement discretion with respect to any CBD products,"127 although this is expected to change in light of language included in the explanatory statement accompanying the FY2020 enacted appropriation (see "What Could Congress Do to Allow CBD to Be Marketed as a Food Additive or Dietary Supplement?").

Some industry stakeholders are recommending that, absent an FDA regulatory framework for CBD products, manufacturers and marketers of dietary supplements or foods that contain hemp or CBD comply with federal regulations for supplements and food in the interim to help ensure the quality of these CBD products. Such compliance would include facility registration, adherence to CGMPs, and meeting labeling requirements.128 In an effort to establish industry-wide standards, one organization has established its own third-party certification program designed for hemp food, dietary supplements, and cosmetic companies.129 This certification program is independent of federal requirements, and FDA has not validated or verified any third-party certification program for hemp.

What Is the Current State of the CBD Market?

At the retail level, consumer products labeled as containing CBD are being marketed and sold in food and beverages, cosmetics and personal care products, certain tobacco products, and dietary supplements—despite FDA's position that CBD may not be sold in food and beverages or dietary supplements. CBD-containing products that claim to meet the definition of hemp are sold through specialty retailers, such as natural/organic grocery stores, tobacco (or smoke) shops, yoga studios, and farmers' markets; through direct-to-consumer and online sales; from herbal practitioners; and by large retailers such as CVS and Walgreens.

Although some industry analysts foresee a strong market for marijuana-derived CBD, it remains prohibited (aside for lawful research purposes) under the CSA if the product does not meet the statutory definition of hemp in 7 U.S.C. §1639o. The DEA has confirmed that a DEA registration is not required to grow or research hemp plants and CBD preparations that meet the statutory definition of hemp.130 Despite the federal prohibition on growing, selling, or possessing marijuana, marijuana-derived CBD products that have not been approved by FDA have been made available in states where medical and/or recreational cannabis is legal under state law, in violation of federal law. Depending on where a CBD product is manufactured and sold, it may primarily be produced using only drug-grade cannabis and marketed as a medicinal or therapeutic product, in violation of FDA requirements. To date, most of the CBD products sold in states where medical and/or recreational cannabis is legal do not meet the statutory definition of hemp. Typically, these products contain 0.45% to 1.5% THC, with some products containing up to 9% THC—levels that could result in psychoactive effects by the user.131

In 2018, CBD sales in the United States were estimated at $534 million, according to the Hemp Business Journal.132 This amount includes sales from hemp-derived CBD products, marijuana-derived CBD products (currently a Schedule I controlled substance), and the FDA-approved drug Epidiolex. In 2018, more than 1,000 companies were producing and marketing CBD products for the U.S. market.133 Since 2014, when total CBD sales were a reported $108 million, U.S. sales of CBD have risen fivefold (Figure 3). In 2018, hemp- and marijuana-derived CBD sales were $240 million and $264 million, respectively, while sales of Epidiolex were estimated at $30 million (Figure 3).

Current projections of U.S. sales of CBD indicate expected growth over the next few years. Such sales are expected to exceed $1 billion in 2020 and reach nearly $2 billion in 2022, roughly split between the three markets (hemp-derived, marijuana-derived, and pharmaceutical CBD; see Figure 3). Others forecast sales well beyond these levels, with some predicting that sales of hemp-derived CBD will eventually dominate the cannabis market, since hemp-derived CBD does not tend to carry the stigma associated with marijuana.134 An ATKearney survey shows that U.S. consumers, regardless of age, strongly believe that cannabis can "offer wellness and therapeutic benefits," ranging from 74% to 83% of those surveyed across all age demographics.135 Some global markets where cannabis is legal are already reporting product shortages of CBD medicinal cannabis products.136 In the United States, growth in CBD sales is expected despite continued regulatory and legal uncertainty, given continued FDA, DEA, and state and local restrictions.

|

|

Source: Hemp Business Journal, The CBD Report: 2018 Industry Outlook, 2019 (New Frontier Data). Notes: All pharmaceutical channel sales are represented by the drug Epidiolex. |

What Could Congress Do to Allow CBD to Be Marketed as a Food Additive or Dietary Supplement?

Despite FDA's current determination that CBD cannot be marketed as a food additive or a dietary supplement, these products continue to be sold. In response, some members of Congress have expressed support for a regulatory framework for hemp-derived CBD in certain FDA-regulated consumer products. In absence of a regulatory framework for hemp-derived CBD products, Congress has directed FDA to issue a policy of enforcement discretion with respect to CBD products that meet the statutory definition of hemp that also come under FDA jurisdiction. More specifically, the explanatory statement accompanying the enacted FY2020 appropriation states that

[t]he agreement includes $2,000,000 for research, policy evaluation, market surveillance, issuance of an enforcement discretion policy, and appropriate regulatory activities with respect to products under the jurisdiction of the FDA which contain CBD and meet the definition of hemp, as set forth in section 297A of the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 (7 U.S.C. 16390). Within 60 days of enactment of this Act, the FDA shall provide the Committees with a report regarding the agency's progress toward obtaining and analyzing data to help determine a policy of enforcement discretion and the process in which CBD meeting the definition of hemp will be evaluated for use in products. The FDA is further directed to perform a sampling study of the current CBD marketplace to determine the extent to which products are mislabeled or adulterated and report to the Committees within 180 days of enactment of this Act.137

The statement does not explicitly require FDA to set a safe level or threshold for CBD in consumer products. However, the activities conducted pursuant to this directive may inform the establishment of such a level in the future. In addition to the activities directed in the explanatory statement, Congress also could take further legislative action, such as requiring FDA to issue a regulation, under its FFDCA authorities, expressly permitting CBD that meets the definition of hemp to be used as a food additive or dietary supplement. For example, such a regulation could prescribe the conditions under which CBD may be safely used as a food additive (e.g., to add flavor or nutritional value to food, in specified quantities, subject to specified labeling requirements). However, because FDA has never before issued such a regulation allowing an approved drug or a substance authorized for investigation as a new drug to be a food additive or added to a dietary supplement, it is not clear what such a regulation would look like.

Congress also could consider amending the FFDCA provisions that FDA has identified as restricting marketing of CBD in food and dietary supplements.138 For example, Congress could exclude from these provisions CBD that meets the statutory definition of hemp.139 However, even if the marketing of CBD-containing products were no longer restricted by these provisions, CBD-containing products may still be subject to other FFDCA requirements. For example, to lawfully market a CBD product as a dietary supplement, a firm may need to submit an NDI notification to FDA, in addition to meeting other statutory and regulatory requirements for supplements. To lawfully market CBD as a food additive, a firm would be expected to either obtain approval via a food additive petition or pursuant to a GRAS determination. As FDA has said that the agency "is not aware of any basis to conclude that CBD is GRAS among qualified experts for its use in human or animal food,"140 a food additive petition may be necessary.

As mentioned above, food and dietary supplements are not evaluated by FDA for safety and effectiveness prior to marketing. Given this fact, in determining whether a legislative approach is appropriate, Congress may consider the potential for adverse health effects and other unintended consequences. For example, clinical trials to support the approval of Epidiolex demonstrated the potential for liver injury at certain doses, and CBD may interact with other drugs or dietary supplements.141 Other concerns include the potential dosing and cumulative effects of exposure to CBD from multiple sources (e.g., food, supplements, and cosmetics); whether there are populations for whom CBD is not appropriate (e.g., pregnant or lactating women); and whether allowing CBD to be marketed as a supplement or food additive could undermine incentives for conducting clinical trials and obtaining evidence of safety and effectiveness to support drug approval.142

FDA's position with respect to the status of CBD impacts other agencies' and regulatory bodies' policies and guidance. For example, TTB consults with FDA on alcohol ingredient safety issues and generally requires that any ingredient added to alcohol beverages must be either an FDA-approved food additive or determined to be GRAS. CBD is not an approved food additive nor has it been found to be GRAS for use in alcohol or otherwise. It remains to be seen whether TTB would allow CBD that meets the definition of hemp to be added to alcoholic beverages if FDA issues a policy of enforcement discretion as directed by the explanatory statement accompanying the FY2020 enacted appropriation. Similarly, the AAFCO has issued guidelines on hemp in animal food, which are generally consistent with FDA's policy. A new policy of enforcement discretion issued pursuant to the language in the explanatory statement may affect AAFCO's guidelines. Additionally, in May 2019, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issued guidance that limits trademark registrations for CBD products. USPTO's guidance describes how it would review marks for cannabis and cannabis-related goods and services, and clarifies that compliance with federal law is a condition of federal trademark registration, regardless of the legality of the activities under state law. It further states that a "determination of whether commerce involving cannabis and cannabis-related goods and services is lawful requires consultation of several different federal laws," including the CSA, FFDCA, and the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334).143 Therefore, "registration of marks for foods, beverages, dietary supplements, or pet treats containing CBD will still be refused as unlawful under the FDCA, even if derived from hemp, as such goods may not be introduced lawfully into interstate commerce."144 Some claim that because the guidance does not specifically address cosmetic products, this could suggest that federal USPTO registration could be possible for such products; however, they also assert that USPTO is looking to FDA to further clarify conditions under which CBD foods, beverages, dietary supplements or pet treats may be lawfully marketed.145

Appendix A. Food Additive Petition Process and GRAS Notification Submission

Food Additive Petition Process

FDA has determined that CBD cannot be added to any food that is sold in interstate commerce. FDA is authorized to issue a regulation, after notice and comment, approving the use of a drug (e.g., CBD) as a food additive,146 although the agency has never done so for any substance.147 The FFDCA does not specify a process for FDA to issue such a regulation, other than that it must be after notice and comment.

In regard to the process for food additive approval, FDA is authorized to "by order establish a regulation" that prescribes the conditions under which a food additive may be safely used.148 The issuance of such regulation may be proposed by FDA on its own initiative or by an interested person via submission of a food additive petition.149 A food additive petition must include, in addition to any explanatory or supporting data, the following information:

- the name and all pertinent information relating to the food additive, including its chemical identity and composition (if possible);

- a statement of the conditions of its proposed use, including directions, recommendations, and suggestions, and the proposed labeling;

- "all relevant data bearing on the physical or other technical effect such additive is intended to produce, and the quantity of such additive required to produce such effect";

- a description of methods for determining the quantity of such additive in or on food, and any substance formed in or on food, because of its use; and

- full reports of safety investigations, including the methods and controls used in conducting such investigations.150

FDA may request that the petitioner also provide information about the manufacturing methods, facilities, and controls, as well as samples of the food additive (or articles used as its components) and samples "of the food in or on which the additive is proposed to be used."151 Additional requirements are specified in FDA regulations.152 Within 30 days of the petition filing date, FDA must publish notice in the Federal Register of the regulation proposed by the petitioner.153 Within 90 days of petition filing, FDA must issue either an order denying the petition or an order establishing a regulation prescribing the conditions under which the food additive may be used safely (e.g., particular foods in which it may be used, maximum quantity, labeling and directions).154 This 90-day period may be extended by FDA, as specified. FDA may not issue such a regulation if a fair evaluation of the data "fails to establish that the proposed use of the food additive, under the conditions of use to be specified in the regulation, will be safe," subject to specified limitations, or if a fair evaluation of the data "shows that the proposed use of the additive would promote deception of the consumer in violation of [the FFDCA] or would otherwise result in adulteration or in misbranding of food."155 FDA is authorized to fix a "tolerance limitation" if necessary to ensure safe use of the additive.156 In considering whether the use of a food additive is safe, FDA must consider, among other relevant factors, the probable consumption of the additive and cumulative effect in the diet.157 Any person adversely affected by such order may file objections with FDA and request a public hearing and may file for judicial review, as specified.158 Food additive regulations may be amended or repealed.159 An interested person may, for example, submit a food additive petition requesting issuance of a regulation allowing a new use of a previously approved additive.

If a food additive is already subject to an FDA regulation for the proposed intended use, it does not require premarket approval via a petition.160 Instead, that food additive may be marketed by complying with the applicable food additive regulation.

GRAS Notice Submission161

Any person may submit a notice to FDA expressing the view that a substance is GRAS and not subject to the premarket review requirements for food additives under FFDCA Section 409. A GRAS notice has seven parts, each of which must be included in a submission to FDA. If one of the seven parts of a GRAS notice is omitted, the submission must explain why that part does not apply. The seven parts of a GRAS notice are as follows:

- 1. signed statements and certification;

- 2. identity, method of manufacture, specifications, and physical or technical effect;

- 3. dietary exposure;

- 4. self-limiting levels of use;

- 5. experience based on common use in food before 1958;

- 6. narrative; and

- 7. a list of supporting data and information in the GRAS notice.

FDA evaluates the submission to determine whether to file it and then informs the submitter of the agency's decision. If FDA decides to file the GRAS notice, the agency sends a letter to the submitter with the filing date. The regulations do not specify a filing deadline for FDA. The regulations do state that FDA is required to respond to a GRAS notice within 180 days of filing. FDA may extend that timeframe by 90 days as needed. Filed GRAS notices are made public by FDA.162

Appendix B. Abbreviations Used in this Report

|

AAFCO |

Association of American Feed Control Officials |

|

CBD |

Cannabidiol |

|

CFSAN |

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition |

|

CGMPs |

Current Good Manufacturing Practices |

|

CSA |

Controlled Substances Act |

|

CVM |

Center for Veterinary Medicine |

|

DEA |

Drug Enforcement Administration |

|

ENDS |

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FFDCA |

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act |

|

FTC |

Federal Trade Commission |

|

GRAS |

Generally Recognized as Safe |

|

IND |

Investigational New Drug [application] |

|

NASEM |

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

|

NDA |

New Drug Application |

|

NDI |

New Dietary Ingredient |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

NLM |

National Library of Medicine |

|

OTC |

Over-the-counter |

|

RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

|

TCA |

Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act |

|

THC |

Tetrahydrocannabinol |

|

TTB |

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau |

|

USDA |

United States Department of Agriculture |

|

USPTO |

United States Patent and Trademark Office |

Source: Created by CRS.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Cannabinoids are the unique chemical compounds found in the plant, which are known to exhibit a range of psychological and physiological effects. |

| 2. |

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), psychoactive is defined as "having a specific effect on the brain," https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/media-guide/glossary. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines psychoactive substances as "substances that, when taken in or administered into one's system, affect mental processes, e.g. cognition or affect. This term and its equivalent, psychotropic drug, are the most neutral and descriptive term for the whole class of substances, licit and illicit, of interest to drug policy. 'Psychoactive' does not necessarily imply dependence-producing, and in common parlance, the term is often left unstated, as in 'drug use' or 'substance abuse,'" https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/terminology/psychoactive_substances/en/. |

| 3. |

Generally, 1% THC concentration is considered the threshold for cannabis to be considered non-psychotropic; marijuana plants often have a THC level of 5% or more. The threshold for differentiating between hemp and marijuana in federal law is 0.3% delta-9 THC. For more background information, see CRS Report R44742, Defining Hemp: A Fact Sheet. |

| 4. |

Consistent with FDA's language, this report uses the term substance instead of ingredient. |

| 5. |

FDA, "FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products: Questions and Answers," Question #2, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd#whatare. |

| 6. |

Plant varieties and cultivars both refer to unique characteristic of a particular plant. For additional information, see CRS Report R44742, Defining Hemp: A Fact Sheet. See also, "FDA and Cannabis: Research and Drug Approval Process," https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process. |

| 7. |

CSA §102(16) [21 U.S.C. §802(16)]. The CSA generally uses the spelling marihuana to refer to the cannabis plant and its derivatives, while this report uses the more common spelling marijuana. As defined in statute, marijuana refers to "all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L., whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; the resin extracted from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin" but does not include "hemp, as defined in section 297A of the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946; or the mature stalks of such plant, fiber produced from such stalks, oil or cake made from the seeds of such plant, any other compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such mature stalks (except the resin extracted therefrom), fiber, oil, or cake, or the sterilized seed of such plant which is incapable of germination." |

| 8. |

Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, P.L. 91-513; 21 U.S.C. §801 et. seq. |

| 9. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44782, The Marijuana Policy Gap and the Path Forward. |

| 10. |

Section 297A of the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 (AMA; 7 U.S.C. §1639o), as amended by the 2018 farm bill, defines hemp to mean "the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of that plant, including the seeds thereof and all derivatives, extracts, cannabinoids, isomers, acids, salts, and salts of isomers, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis." Among the identified isomers of THC, delta-9 THC is considered to be the dominant psychotropic compound in the cannabis plant. Other identified isomers of THC present in cannabis include delta-8 THC, delta-1 THC, and delta-6 THC. |

| 11. |

P.L. 115-334 §10113. |

| 12. |