Poverty in the United States in 2018: In Brief

In 2018, approximately 38.1 million people, or 11.8% of the population, had incomes below the official definition of poverty in the United States. Poverty statistics provide a measure of economic hardship. The official definition of poverty for the United States uses dollar amounts called poverty thresholds that vary by family size and the members’ ages. Families with incomes below their respective thresholds are considered to be in poverty. The poverty rate (the percentage that was in poverty) fell from 12.3% in 2017. This was the fourth consecutive year since the most recent recession that the poverty rate has fallen.

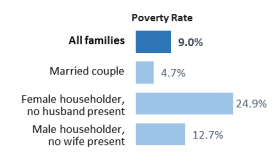

The poverty rate for female-householder families in 2018 (24.9%, down 1.3 percentage points from the previous year) was higher than that for male-householder families (12.7%) or married-couple families (4.7%), neither of which registered a decline from 2017.

Of the three age groups—children under 18, the working-age population, and those age 65 and older—the 65-and-older population used to have the highest poverty rates, but now has the lowest: 28.5% of the aged population was poor in 1966, but 9.7% was poor in 2018. People under 18, in contrast, had the highest poverty rate of the three age groups: 16.2% of this population was poor in 2018.

From 2017 to 2018, poverty rates fell among children (from 17.4% to 16.2%) and the working-age population (from 11.1% to 10.7%), but not among the aged population (9.7% in 2018).

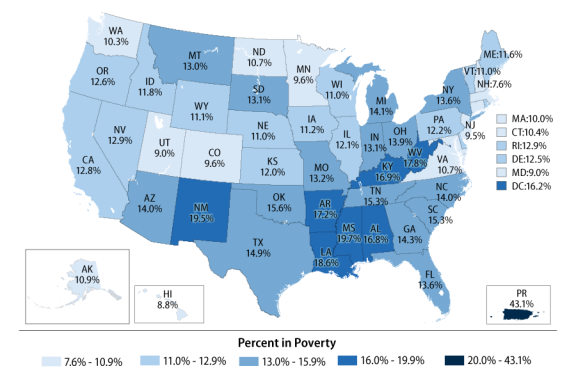

Poverty was not equally prevalent in all parts of the country. The poverty rate for Mississippi (19.7%) appeared highest but was in a statistical tie with New Mexico (19.5%). New Hampshire’s poverty rate (7.6%) was lowest in 2018.

Criticisms of the official poverty measure have inspired poverty measurement research and eventually led to the development of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). The SPM uses different definitions of needs and resources than the official measure.

The SPM includes the effects of taxes and in-kind benefits (such as housing, energy, and food assistance) on poverty, while the official measure does not. Because some types of tax credits are used to assist the poor (as are other forms of assistance), the SPM may be of interest to policymakers.

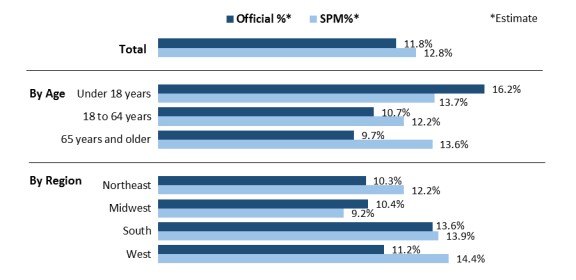

The poverty rate under the SPM (12.8%) was about 1 percentage point higher in 2018 than the official poverty rate (11.8%).

Under the SPM, the profile of the poverty population is slightly different than under the official measure. Compared with the official measure, poverty rates under the SPM were lower for children (13.7% compared with 16.2%) and higher for working-age adults (12.2% compared with 10.7%) and the 65-and-older population (13.6% compared with 9.7%).

While the SPM reflects more current measurement methods, the official measure provides a comparison of the poor population over a longer time period, including some years before many current antipoverty assistance programs had been developed. In developing poverty-related legislation and conducting oversight on programs that aid the low-income population, policymakers may be interested in these historical trends.

Poverty in the United States in 2018: In Brief

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- How the Official Poverty Measure Is Computed

- Historical Perspective

- Poverty for Demographic Groups

- Family Structure

- Age

- Race and Hispanic Origin

- Work Status

- Poverty Rates by State

- Supplemental Poverty Measure

- How the Official Poverty Measure Was Developed

- Motivation for a Supplemental Measure

- Official and Supplemental Poverty Findings for 2018

Figures

- Figure 1. Number of Persons Below Poverty and Poverty Rate, 1959 to 2018

- Figure 2. Poverty Rates of Families by Family Structure: 2018

- Figure 3. Poverty Rates by Age: 1959 to 2018

- Figure 4. Poverty Rates by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2018

- Figure 5. Percentage of People in Poverty in the Past 12 Months by State and for the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico: 2018

- Figure 6. Poverty Rates Under Official Measure and Supplemental Poverty Measure, for the U.S. Total, by Age, and by Region: 2018

Summary

In 2018, approximately 38.1 million people, or 11.8% of the population, had incomes below the official definition of poverty in the United States. Poverty statistics provide a measure of economic hardship. The official definition of poverty for the United States uses dollar amounts called poverty thresholds that vary by family size and the members' ages. Families with incomes below their respective thresholds are considered to be in poverty. The poverty rate (the percentage that was in poverty) fell from 12.3% in 2017. This was the fourth consecutive year since the most recent recession that the poverty rate has fallen.

- The poverty rate for female-householder families in 2018 (24.9%, down 1.3 percentage points from the previous year) was higher than that for male-householder families (12.7%) or married-couple families (4.7%), neither of which registered a decline from 2017.

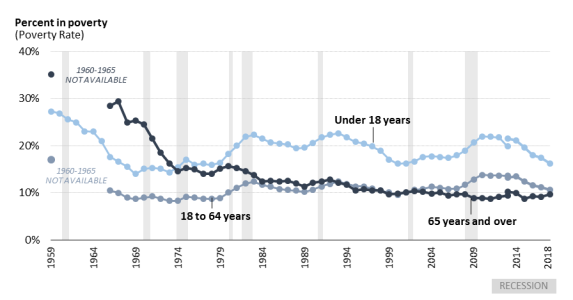

- Of the three age groups—children under 18, the working-age population, and those age 65 and older—the 65-and-older population used to have the highest poverty rates, but now has the lowest: 28.5% of the aged population was poor in 1966, but 9.7% was poor in 2018. People under 18, in contrast, had the highest poverty rate of the three age groups: 16.2% of this population was poor in 2018.

- From 2017 to 2018, poverty rates fell among children (from 17.4% to 16.2%) and the working-age population (from 11.1% to 10.7%), but not among the aged population (9.7% in 2018).

- Poverty was not equally prevalent in all parts of the country. The poverty rate for Mississippi (19.7%) appeared highest but was in a statistical tie with New Mexico (19.5%). New Hampshire's poverty rate (7.6%) was lowest in 2018.

Criticisms of the official poverty measure have inspired poverty measurement research and eventually led to the development of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). The SPM uses different definitions of needs and resources than the official measure.

- The SPM includes the effects of taxes and in-kind benefits (such as housing, energy, and food assistance) on poverty, while the official measure does not. Because some types of tax credits are used to assist the poor (as are other forms of assistance), the SPM may be of interest to policymakers.

- The poverty rate under the SPM (12.8%) was about 1 percentage point higher in 2018 than the official poverty rate (11.8%).

- Under the SPM, the profile of the poverty population is slightly different than under the official measure. Compared with the official measure, poverty rates under the SPM were lower for children (13.7% compared with 16.2%) and higher for working-age adults (12.2% compared with 10.7%) and the 65-and-older population (13.6% compared with 9.7%).

- While the SPM reflects more current measurement methods, the official measure provides a comparison of the poor population over a longer time period, including some years before many current antipoverty assistance programs had been developed. In developing poverty-related legislation and conducting oversight on programs that aid the low-income population, policymakers may be interested in these historical trends.

Introduction

In 2018, approximately 38.1 million people, or 11.8% of the population, had incomes below the official definition of poverty in the United States. The poverty rate (the percentage that were in poverty) fell from 12.3% in 2017, while the number of persons in poverty declined from 39.6 million.1

In this report, the numbers and percentages of those in poverty are based on the Census Bureau's estimates.2 While this official measure is often regarded as a statistical yardstick rather than a complete description of what people and families need to live,3 it does offer a measure of economic hardship faced by the low-income population: the poverty measure compares family income against a dollar amount called a poverty threshold, a level below which the family is considered to be poor. The Census Bureau releases these poverty estimates every September for the prior calendar year. Most of the comparisons discussed in this report are year-to-year comparisons. This report only considers a number or percentage to have changed from the previous year, or to be different from another number or percentage, if the difference has been tested to be statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. 4

However, in addition to the most recent year's data, this report presents a historical perspective as well as information on poverty for demographic groups (by family structure, age, race and Hispanic origin, and work status) and by state.

Over the past several decades, criticisms of the official poverty measure have led to the development of an alternative research measure called the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which the Census Bureau also computes and releases. Statistics comparing the official measure with the SPM are provided at the conclusion of this brief.

The SPM includes the effects of taxes and in-kind benefits (such as housing, energy, and food assistance) on poverty, while the official measure does not. Because some types of tax credits are used to assist the poor, as are other forms of assistance, the SPM may be of interest to policymakers. However, the official measure provides a comparison of the poor population over a longer time period, including some years before many current antipoverty assistance programs had been developed. In developing poverty-related legislation and conducting oversight on programs that aid the low-income population, policymakers may be interested in these historical trends.

How the Official Poverty Measure Is Computed

The Census Bureau determines a person's poverty status by comparing his or her resources against a measure of need. For the official measure, resources is defined as total family income before taxes, and the measure of "need" is a dollar amount called a poverty threshold. There are 48 poverty thresholds that vary by family size and composition. If a person lives with other people to whom he or she is related by birth, marriage, or adoption, the money income from all family members is used to determine his or her poverty status. If a person does not live with any family members, his or her own income is used. Only money income before taxes is used in calculating the official poverty measure, meaning this measure does not treat in-kind benefits such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), housing subsidies, or employer-provided benefits as income.

The poverty threshold dollar amounts vary by the size of the family (from one person not living in a family, to nine or more family members living together) and the ages of the family members (how many of the members are children under 18 and whether or not the family head is 65 years of age or older). Collectively, these poverty thresholds are often referred to as the poverty line. As a rough guide, the poverty line in 2018 can be thought of as $25,701 for a family of four, $19,985 for a family of three, $16,247 for a family of two, or $12,784 for an individual not living in a family, though the official measure is actually much more detailed.5

The threshold dollar amounts are updated annually for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. Notably, the same thresholds are applied throughout the country: no adjustment is made for geographic variations in living expenses.6

The official poverty measure used in this report is the federal government's definition of poverty for statistical purposes, such as comparing the number or percentage of people in poverty over time. A related definition of poverty, the poverty guidelines published by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is used for administrative purposes such as eligibility criteria for assistance programs and will not be discussed in this report.7

Historical Perspective

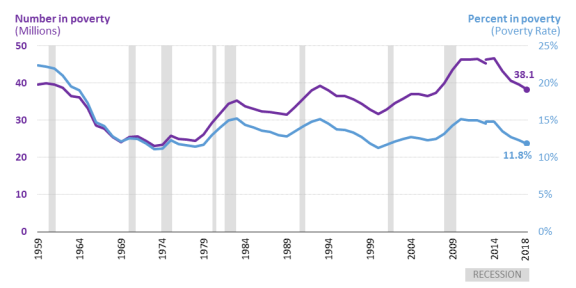

Figure 1 shows a historical perspective of the number and percentage of the population below the poverty line. The number in poverty and the poverty rates are shown from the earliest year available (1959), through the most recent year available (2018). Because the total U.S. population has grown over time, poverty rates are useful for historical comparisons because they control for population growth.

Poverty rates fell through the 1960s. Since then, they have generally risen and fallen according to the economic cycle, though during the most recent two expansions poverty rates did not fall measurably until four to six years into the expansion. Historically notable lows occurred in 1973 (11.1%) and 2000 (11.3).8 Poverty rate peaks occurred in 1983 (15.2%), 1993 (15.1%), and 2010 (15.1%).9

Poverty rates tend to rise during and after recessions, as opposed to leading economic indicators such as new housing construction, whose changes often precede changes in the performance of the overall economy. The poverty rate's lag is explainable in part by the way it is measured: it uses income from the entire calendar year.

Notably, the poverty rate in 2018 registered a fourth consecutive annual decrease since the most recent recession, though it remained higher than the rate in 2000, the most recent low point.

|

Figure 1. Number of Persons Below Poverty and Poverty Rate, 1959 to 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages, number of persons in millions. Shaded bars indicate recessions) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on poverty data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 1960-2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Historical Poverty Table 2, http://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/tables/time-series/historical-poverty-people/hstpov2.xls. Recession dates obtained from National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html. Notes: Two estimates are shown for 2013 because the Census Bureau implemented a change to the CPS ASEC income questions. This change was partially implemented with the 2013 data and fully implemented for the 2014 data. For 2013, some households received the old questionnaire and others the new, so that it would be possible to see the effect of changing the questionnaire as well as to be able to make consistent comparisons both before and after 2013. The CPS ASEC processing system was also updated for 2017, although those updates did not affect the overall poverty rate. For details, see John Creamer and Ashley Edwards, "Examining Poverty in 2016 and 2017 Using the Legacy and Updated Current Population Survey Processing System," U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, Working Paper #2019-28, July 30, 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2019/demo/SEHSD-WP2019-28.html. |

Poverty for Demographic Groups10

The drop in the U.S. poverty rate (from 12.3% in 2017 to 11.8% in 2018) affected some demographic groups more than others, notably people in female-householder families, children and the population aged 18 to 64, and the non-Hispanic white population. Details for selected demographic groups are described below.

Family Structure

Because poverty status is determined at the family level by comparing resources against a measure of need, vulnerability to poverty may differ among families of different compositions. In this section, poverty data by family structure are presented using the official poverty measure, with "families" defined as persons related by birth, marriage, or adoption to the householder (the person in whose name the home is owned or rented).11 In the "Supplemental Poverty Measure" section of this report, a different definition will be used.

Families with a female householder and no spouse present (female-householder families) have historically had higher poverty rates than both married-couple families and families with a male householder and no spouse present (male-householder families). This remained true in 2018: female-householder families experienced a poverty rate of 24.9%, compared with 4.7% for married-couple families and 12.7% for male-householder families. Unlike the other two family types, however, female-householder families experienced a decline in their poverty rate of 1.3%. Their 2018 rate of 24.9%, down from 26.2% in 2017, appeared to be among the lowest poverty rates for female-householder families on record.12

Among individuals not living in families, the poverty rate was 20.2% in 2018, not distinguishable from the previous year.

|

Figure 2. Poverty Rates of Families by Family Structure: 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, using data from Figure 9 and Table B-2 of Jessica L. Semega, Melissa A. Kollar, John Creamer, and Abinash Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html. Notes: The poverty rates above include only families with a householder (the survey's reference person for the household, typically the person in whose name the home is owned or rented). The Census Bureau defines a family as those living together related by birth, marriage, or adoption. |

Age

When examining poverty by age, three main groups are noteworthy for distinct reasons: under 18, 18 to 64, and 65 and older. People under age 18 are typically dependent on other family members for income, particularly young children below their state's legal working age. People aged 18 to 64 are generally thought of as the working-age population and typically have wages and salaries as their greatest source of income. People age 65 and older, referred to as the aged population, are often eligible for retirement, and those who do retire typically experience a change in their primary source of income.

Children and the working-age population experienced decreases in poverty. Among children, 11.9 million, or 16.2%, were poor, down from 12.8 million or 17.4% in 2017. Among the working-age population, 21.1 million, or 10.7%, were in poverty, down from 21.9 million or 11.1% in 2017. The aged population did not register any significant changes in its number in poverty or its poverty rate from 2017 to 2018: 5.1 million, or 9.7%, were poor.

From a historical standpoint, the poverty rate for those age 65 and over used to be the highest of the three groups. In 1966, people age 65 and over had a poverty rate of 28.5%, compared with 17.6% for those under 18 and 10.5% for working-age adults. By 1974, the poverty rate for people age 65 and over had fallen to 14.6%, compared with 15.4% for people under 18 and 8.3% for working-age adults. Since then, people under 18 have had the highest poverty rate of the three age groups, as shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3. Poverty Rates by Age: 1959 to 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages. Shaded bars indicate recessions) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, using data from Historical Poverty Table 3, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 1960-2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplements, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/tables/time-series/historical-poverty-people/hstpov3.xls. Recession dates obtained from National Bureau of Economic Research, http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html. Notes: Data are not available from 1960 to 1965 for persons age 65 and older and for persons aged 18 to 64. For each group, two estimates are shown for 2013 because the Census Bureau implemented a change to the CPS ASEC income questions. Some households received the old questionnaire and others the new, so that it would be possible to see the effect of changing the questionnaire. The CPS ASEC processing system was also updated for 2017. Those updates did not affect the overall poverty rate, nor the poverty rates for children or the population aged 18-64, though the 2017 poverty rate for the aged was 0.3 percentage points higher than under the legacy system. For details see John Creamer and Ashley Edwards, "Examining Poverty in 2016 and 2017 Using the Legacy and Updated Current Population Survey Processing System," U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, Working Paper #2019-28, July 30, 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2019/demo/SEHSD-WP2019-28.html. |

Race and Hispanic Origin13

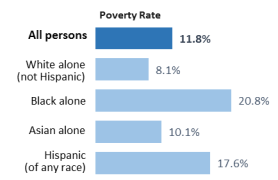

Poverty rates vary by race and Hispanic origin, as shown in Figure 4. In surveys, Hispanic origin is asked separately from race; accordingly, people identifying as Hispanic may be of any race. The poverty rate fell for non-Hispanic whites (from 8.5% in 2017 to 8.1% in 2018). Among blacks14 (20.8%), Asians15 (10.1%), and Hispanics (17.6%), the poverty rate did not register any statistically significant change from 2017.16

|

Figure 4. Poverty Rates by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, using data from Figure 4 and Table B-1 of Jessica L. Semega, Melissa A. Kollar, John Creamer, and Abinash Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html. Notes: People of Hispanic origin may be of any race. Additionally, respondents may identify with one or more racial groups. Except for "All persons" and "Hispanic," the remaining groups shown include those who identified with one race only. Data for Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and the population of two or more races are not shown separately. |

Work Status

While having a job reduced the likelihood of being in poverty, it did not guarantee that a person or his or her family would avoid poverty. Among the 18 to 64-year-old population living in poverty, 77.2% had jobs in 2018. Poverty rates among workers in this age group were 5.1% for all workers, 2.3% for full-time year-round workers, and 12.7% for part-time or part-year workers, none of which were measurably changed from the previous year. Similarly, no significant change was detected among those who did not work at least one week in 2018 (29.7% were poor).

Because poverty is a family-based measure, the change in one member's work status can affect the poverty status of his or her entire family. Among all 18 to 64-year-olds who did not have jobs in 2018, 58.9% lived in families in which someone else did have a job.17 Among poor 18 to 64-year-olds without jobs, 18.5% lived in families where someone else worked.18

Poverty Rates by State19

Poverty is not equally prevalent in all parts of the country. The map in Figure 5 shows states with relatively high poverty rates across parts of the Appalachians, the Deep South, and the Southwest, with the poverty rate in Mississippi (19.7%) among the highest in the nation, not statistically different from the rate in New Mexico (19.5%). The poverty rate in New Hampshire (7.6%) was lowest. When comparing poverty rates geographically, it is important to remember that the official poverty thresholds are not adjusted for geographic variations in the cost of living—the same thresholds are used nationwide. As such, an area with a lower cost of living accompanied by lower wages will appear to have a higher poverty rate than an area with a higher cost of living and higher wages, even if individuals' purchasing power were exactly the same in both areas.

Puerto Rico and 14 states experienced poverty rate declines from 2017 to 2018: one in the Midwest (Illinois), three in the Northeast (Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York); five in the South (Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and West Virginia); and five in the West (Arizona, California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington).20 Connecticut was the only state to experience an increase, and 35 states, as well as the District of Columbia, did not register a statistically significant change.21

|

Figure 5. Percentage of People in Poverty in the Past 12 Months by State and for the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico: 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on poverty data from Craig Benson and Alemayehu Bishaw, Poverty: 2017 and 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Brief ACSBR/18-02, Table 1, issued September 2019, using 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) and 2018 Puerto Rico Community Survey, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/acs/acsbr18-02.html. Notes: Data by state are based on the ACS while national-level data presented elsewhere in this report are based on the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC). The ACS reported a poverty rate of 13.1% for the United States in 2018, compared with 11.8% in the CPS ASEC. See footnote 19 for further details. |

Supplemental Poverty Measure

Criticisms of the official measure have led to the development of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). Described below are the development of the official measure, its limitations, attempts to remedy those limitations, the research efforts that eventually led to the SPM's first release in November 2011, and a comparison of poverty rates in 2018 based on the SPM and the official measure.22

How the Official Poverty Measure Was Developed

The poverty thresholds were originally developed in the early 1960s by Mollie Orshansky of the Social Security Administration. Rather than attempt to compute a family budget by using prices for all essential items that low-income families need to live, Orshansky focused on food costs.23 Unlike other goods and services such as housing or transportation, which did not have a generally agreed-upon level of adequacy, minimum standards for nutrition were known and widely accepted. According to a 1955 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food consumption survey, the average amount of their income that families spent on food was roughly one-third. Therefore, using the cost of a minimum food budget and multiplying that figure by three yielded a figure for total family income. That computation was possible because USDA had already published recommended food budgets as a way to address the nutritional needs of families experiencing economic stress. Some additional adjustments were made to derive poverty thresholds for two-person families and individuals not living in families to reflect the relatively higher fixed costs of smaller households.

Motivation for a Supplemental Measure

While the official poverty measure has been used for over 50 years as the source of official statistics on poverty in the United States, it has received criticism over the years for several reasons. First, it does not take into account benefits from most of the largest programs that aid the low-income population. For instance, it uses money income before taxes—meaning that it does not necessarily measure the income available for individuals to spend, which for most people is after-tax income. Therefore, any effects of tax credits designed to assist persons with low income are not captured by the official measure. The focus on money income also does not account for in-kind benefit programs designed to help the poor, such as SNAP or housing assistance.

The official measure has also been criticized for the way it characterizes families' and individuals' needs in the poverty thresholds. That is, the method used to compute the dollar amounts used in the thresholds, which were originally based on food expenditures in the 1950s and food costs in the 1960s, does not accurately reflect current needs and available goods and services.24 Moreover, the official measure does not take account of the sharing of expenses and income among household members not related by birth, marriage, or adoption. And, as mentioned earlier, the official thresholds do not take account of geographic variations in the cost of living.

In 1995, a panel from the National Academy of Sciences issued a report, Measuring Poverty: A New Approach, which recommended improvements to the poverty measure.25 Among the suggested improvements were to have the poverty thresholds reflect the costs of food, clothing, shelter, utilities, and a little bit extra to allow for miscellaneous needs; to broaden the definition of "family;" to include geographic adjustments as part of the measure's computation; to include the out-of-pocket costs of medical expenses in the measure's computation; and to subtract work-related expenses from income. An overarching goal of the recommendations was to make the poverty measure more closely aligned with the real-life needs and available resources of the low-income population, as well as the changes that have taken place over time in their circumstances, owing to changes in the nation's economy, society, and public policies (see Table 1).

After over a decade and a half of research to implement and refine the methodology suggested by the panel, conducted both from within the Census Bureau as well as from other federal agencies and the academic community, the Census Bureau issued the first report using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) in November 2011.26

|

Official Poverty Measure |

Supplemental Poverty Measure |

||

|

Resource units ("families") |

People related by birth, marriage, or adoption (official Census Bureau definition of "family"). People age 15 and older not related to anyone else in the household are considered as their own economic units. |

People related by birth, marriage, adoption, plus unrelated and foster children, and cohabiting partners and their children or other relatives (if any) are considered as "SPM resource units" (sharing resources and expenses together). |

|

|

Needs (thresholds) |

Vary according to family size and ages of family members. |

Vary according to the size and composition of the resource unit (see above). |

|

|

Dollar amounts based on the cost of a food plan for families in economic stress in the early 1960s, times three (with adjustments for two-person families and individuals). |

Dollar amounts based on consumer expenditure data for food, clothing, shelter, utilities, with adjustments by homeownership and mortgage or rental status. |

||

|

Updated for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. |

Based on most recent five years of consumer expenditure data (not fixed at one point and trended forward). |

||

|

No geographic cost adjustments. |

Housing costs geographically adjusted for metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas. |

||

|

Resources |

Money income before taxes (includes 18 private and government sources of income, including Social Security, cash assistance, and other sources of cash income). |

Money income (both private and government sources) after taxes ... minus: work expenses, child care expenses, child support paid, out-of-pocket medical expenses, plus: tax credits (such as the Child Tax Credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit) and the value of in-kind benefits (such as food and housing subsidies). |

Source: Congressional Research Service summary of methodological discussion in Liana Fox, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2018, http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-265.pdf.

Notes: For caveats, see the text of the section, "Supplemental Poverty Measure."

Official and Supplemental Poverty Findings for 201827

Compared with the official measure, the SPM takes into account greater detail of individuals' and families' living arrangements and provides a more up-to-date accounting of the costs and resources available to them. Because the SPM recognizes greater detail in relationships among household members and geographically adjusts housing costs, it provides an updated rendering, compared with the official measure, of the circumstances in which the poor live. In that context, some point out that the SPM's measurement of taxes, transfers, and expenses may offer policymakers a clearer view of how government policies affect the poor population today. However, the SPM was developed as a research measure, and the Office of Management and Budget set the expectation that it would be revised periodically to incorporate improved measurement methods and newer sources of data as they became available; it was not developed for administrative purposes. Conversely, the official measure's consistency over a longer time span makes it easier for policymakers and researchers to make historical comparisons.

Under the SPM, the profile of the poverty population is slightly different than under the official measure. The SPM was 1 percentage point higher in 2018 than the official poverty rate (12.8% compared with 11.8%; see Figure 6).28 More people aged 18 to 64 are in poverty under the SPM (12.2% compared with 10.7% under the 2018 official measure), as are people age 65 and over (13.6%, compared with 9.7% under the official measure). The poverty rate for people under age 18 was lower under the SPM (13.7% in 2018) than under the official measure (16.2%, with foster children included). Again, the SPM uses a different definition of resources than the official measure: the SPM includes in-kind benefits which generally help families with children; subtracts out work-related expenses, which are often incurred by the working-age population; and subtracts medical out-of-pocket expenses, which are incurred frequently by people age 65 and older.

|

Figure 6. Poverty Rates Under Official Measure and Supplemental Poverty Measure, for the U.S. Total, by Age, and by Region: 2018 (Poverty rates in percentages) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on data from Liana Fox, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, rev. October 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-268.html. Notes: Figures include unrelated individuals under age 15 (such as foster children), who are not usually included in official poverty estimates. |

With the geographically adjusted thresholds, the poverty rate in 2018 was lower under the SPM than under the official measure for the Midwest (9.2% compared with 10.4%), while it was higher than the official measure for the Northeast (12.2% compared with 10.3%), the West (14.4% compared with 11.2%), and the South (13.9% compared with 13.6%).

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

All data for 2017 are based on a revised processing system and were released by the Census Bureau in September 2019. They may not match previously published data. |

| 2. |

The national-level data in this report were obtained from the 2018 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Details on the official measure of poverty according to the CPS ASEC are available in Jessica L. Semega, Melissa A. Kollar, John Creamer, and Abinash Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html (hereinafter, Semega, Kollar, Creamer, and Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018). Accompanying detailed tabulations are available as well. Details on the Supplemental Poverty Measure, also based primarily on the 2018 CPS ASEC, are available in Liana Fox, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-268.html. State-level data in this report were obtained from the 2018 American Community Survey, also conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Details are available in Craig Benson and Alemayehu Bishaw, Poverty: 2017 and 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Brief ACSBR/18-02, September 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/acs/acsbr18-02.html. |

| 3. |

Semega, Kollar, Creamer, and Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, Appendix B. The characterization of the poverty measure as a statistical yardstick goes back decades. See, for example, "U.S. Changes Yardstick on Who Is Poor," Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1965, section 1B, p. 4. |

| 4. |

Not every apparent difference in point estimates is a real difference. The official poverty measure uses information from the CPS ASEC, which surveys about 95,000 addresses nationwide. All poverty data discussed here are therefore estimates, which have margins of error. Surveying a different sample would likely yield slightly different estimates of the poverty population or the poverty rate. Thus, even if the true poverty rate were exactly the same in two different years, it is possible to get survey estimates that appear different. In order to report that a change has occurred in the poverty rate—that is, that the difference between the estimates is likely not caused by sampling variability—the difference has to be large enough that fewer than 10% of all possible survey samples would produce a difference that large (and, conversely, 90% of the samples would not). Such a difference is said to be statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. Point estimates whose differences are not statistically significant are described in this report as "no discernible change," "no measurable change," "not statistically different," or "not distinguishable from … ", etc. |

| 5. |

To provide a general sense of the poverty line, the Census Bureau computes weighted averages of the thresholds within each size of family. For example, a family of three may consist of any of the following combinations: three adults, two adults and one child, or one adult and two children. Each combination has its own distinct threshold. The $19,985 figure cited represents an average of those family combinations, adjusted to reflect that some types of three-person families are more common than others. The averages are a convenience for the reader, but are not actually used to compute poverty status for statistical reports. In actual computations, 48 thresholds are used in the official measure. |

| 6. |

Unlike the poverty thresholds that are used to compute official poverty statistics, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) poverty guidelines used for administrative purposes do include separate amounts for Alaska and Hawaii. |

| 7. |

The official poverty measure described in this report was established in the Office of Management and Budget's Statistical Policy Directive 14, May 1978, reproduced on the Census Bureau's website at https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/about/history-of-the-poverty-measure/omb-stat-policy-14.html. It states that the official measure is to be used for statistical purposes, but should not be construed as required for administrative purposes. An example of an administrative use is as an eligibility criterion for assistance programs. A different measure, called the poverty guidelines, is published by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Though the poverty guidelines use the official thresholds as part of their computation, the HHS poverty guidelines are collectively a distinct poverty definition and are often used as a criterion in federal assistance programs. The HHS poverty guidelines are often referred to as the "federal poverty level" or FPL. See CRS Report R44780, An Introduction to Poverty Measurement, for further discussion. |

| 8. |

The poverty rates in 1973 and 2000, the lowest point estimates on record, are not statistically different from each other and are considered to be "tied" for lowest poverty rate. |

| 9. |

These poverty rates may not necessarily be distinguishable from the poverty rates in their adjacent years. See footnote 4 for an explanation of statistical significance. |

| 10. |

All data in this section were obtained from Semega, Kollar, Creamer, and Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018 unless otherwise noted. Data for families are available in Table B-2 of that report; data for the other demographic groups are available in Table B-1. |

| 11. |

Not included in this section are cohabiting couples, people living alone or with non-relatives, and people related to each other but not to the householder. Legally married same-sex couples, however, are included. The Census Bureau implemented revisions to its CPS ASEC processing system, which, along with other adjustments, updated processing for families to include same-sex families. Comparisons between 2017 and 2018 are based on the new processing system for both years. For details on how the new system affected the poverty estimates, see John Creamer and Ashley Edwards, "Examining Poverty in 2016 and 2017 Using the Legacy and Updated Current Population Survey Processing System," U.S. Census Bureau, Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, Working Paper #2019-28, July 30, 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2019/demo/SEHSD-WP2019-28.html. |

| 12. |

The 2018 poverty rate for female-householder families was not statistically different from the corresponding poverty rate in 2000 (25.4%). |

| 13. |

Since 2002, federal surveys have asked respondents to identify with one or more races; previously they could choose only one. The groups in this section represent those who identified with one race alone. Another approach is to include those who selected each race group either alone or in combination with one or more other races. Those data are also available on the Census Bureau's website at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.html where they are published in Appendix B of Semega, Kollar, Creamer, and Mohanty, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018 and in accompanying historical data tables. |

| 14. |

Includes blacks of Hispanic origin. |

| 15. |

Includes Asians of Hispanic origin. |

| 16. |

Poverty rates for the American Indian and Alaska Native population, the Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander population, and the population reporting two or more races had wide margins of error. The CPS ASEC's sample size was not large enough to provide precise estimates for these three smallest race categories. |

| 17. |

Congressional Research Service, author's tabulation using the 2019 CPS ASEC public use file. |

| 18. |

Ibid. |

| 19. |

These state estimates are based on the American Community Survey (ACS) instead of the CPS ASEC, because the Census Bureau recommends the ACS when comparing states and smaller geographic areas. Since the CPS ASEC surveys 90,000 to 100,000 addresses nationwide, it is sometimes difficult to obtain reliable estimates for small populations or small geographic areas – the sample may not have selected enough people from that group or area to provide a meaningful estimate. The ACS samples about 3.5 million addresses per year and therefore affords greater statistical precision for comparing states and smaller geographic areas. Unlike the CPS ASEC, however, which uses trained interviewers and detailed income questions, the ACS is filled out by the respondent on his or her own. Furthermore, the ACS is conducted continuously, and asks the respondents about their income in the previous 12 months, not necessarily the previous calendar year as in the CPS ASEC. For those reasons, poverty estimates from the ACS are often different from CPS ASEC estimates: the ACS reported a poverty rate of 13.1% for the U.S. in 2018, compared with 11.8% in the CPS ASEC. Poverty estimates from neither the ACS nor the CPS ASEC include Puerto Rico in the U.S. total. Puerto Rico's poverty rate was 43.1% in 2018. The ACS is not conducted in the other U.S. territories. |

| 20. |

The Census regions are as follows: |

| 21. |

Data collection errors were discovered in the 2017 data for Delaware. As a result, statistical testing for change in Delaware's poverty rate between 2017 and 2018 was not performed. Details on the data collection errors are available at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/errata/120.html. |

| 22. |

For a more thorough discussion of the SPM's development and methodology, see CRS Report R45031, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: Its Core Concepts, Development, and Use. |

| 23. |

While Orshansky did not attempt to compute a complete basket of goods and services, her focus on food costs was already a more detailed empirical approach to poverty measurement than were the dollar amounts used in the 1964 Economic Report of the President, issued by the Council of Economic Advisers (chapter 2, "The Problem of Poverty in America"). In that report, a flat figure of $3,000 was used for all families and $1,500 for unrelated individuals. See also Economic Report of the President (1964) https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/45#8135. For a thorough history of the official poverty measure, see Gordon Fisher, "The Development of the Orshansky Thresholds and Their Subsequent History as the Official U.S. Poverty Measure," 1992, rev. 1997, reproduced on the Census Bureau's website at https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/1997/demo/fisher-02.html. |

| 24. |

Criticisms have been discussed in the mainstream press as well as within academia. A 1988 article (Spencer Rich, "Drawing the Line Between Rich, Poor," The Washington Post, September 23, 1988, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1988/09/23/drawing-the-line-between-rich-poor/60f5dbeb-dab3-4a42-819a-2dea34e7854e/) documented dissatisfaction about the official measure. This came from both those claiming it was too high, citing its failure to capture the effects of in-kind benefits for the poor and its overstatement of inflation, and those claiming it was too low, based on the fact that if the thresholds were derived using more recent household consumption data, they would be based on roughly five times the cost of food, not three times as Orshansky had computed in the early 1960s. |

| 25. |

Constance F. Citro and Robert T. Michael, eds., Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. Panel on Poverty and Family Assistance: Concepts, Information Needs, and Measurement Methods. Committee on National Statistics, National Research Council. National Academies Press, Washington DC, 1995. Available at https://www.nap.edu/read/4759/chapter/1. |

| 26. |

26 The effort to consolidate the previous research and create the SPM was done under the auspices of an Interagency Technical Working Group (ITWG) led by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and received public commentary via a Federal Register notice (Federal Register, vol. 75 no. 101, Wednesday, May 26, 2010, pp. 29513-29514, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/05/26/2010-12628/developing-a-supplemental-poverty-measure). The Federal Register notice referenced a report by the ITWG ("Observations from the Interagency Technical Working Group on Developing a Supplemental Poverty Measure"), which has since been moved to a new URL at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/topics/income/supplemental-poverty-measure/spm-twgobservations.pdf. The comments that the Census Bureau received on that report are available on the Census Bureau's website at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/topics/income/supplemental-poverty-measure/redactedcomments.pdf. These and additional methodological documents on the SPM are available at https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/supplemental-poverty-measure/guidance/methodology.html. |

| 27. |

Data in this section are available in Liana Fox, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2019, Appendix Table A-2, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-268.html. |

| 28. |

To establish a fairer comparison with the SPM, a set of poverty estimates using the official measure was recomputed to include unrelated individuals under age 15 (such as foster children) who are not normally included in the official measure. |