Gun Control: National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Operations and Related Legislation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) administers a computer system of systems that is used to query federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial criminal history record information (CHRI) and other records to determine an individual’s firearms transfer/receipt and possession eligibility. This FBI-administered system is the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). NICS, or parallel state systems, must be checked and the pending transfer approved by the FBI or state point of contact before a federally licensed gun dealer may transfer a firearm to any customer who is not also a federally licensed gun dealer. Current federal law does not require background checks for intrastate (same state), private-party firearms transactions between nondealers, though such checks are required under several state laws.

In the 116th Congress, the House of Representatives passed three bills that would expand federal firearms background check requirements and firearms transfer/receipt and possession ineligibility criteria related to domestic violence.

The Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8), a “universal” background check bill, would make nearly all intrastate, private-party firearms transactions subject to the recordkeeping and NICS background check requirements of the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA). For the past two decades, many gun control advocates have viewed the legal circumstances that allow individuals to transfer firearms intrastate among themselves without being subject to the licensing, recordkeeping, and background check requirements of the GCA as a “loophole” in the law, particularly within the context of gun shows. Gun rights supporters often oppose such measures, underscoring that it is already unlawful to knowingly transfer a firearm or ammunition to a prohibited person. In addition, some observers object to these circumstances being characterized as a loophole, in that the effects of the underlying provisions of current law are not unintended or inadvertent.

The Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112) would lengthen the amount of time firearms transactions could be delayed pending a completed NICS background check from three business days under current law to several weeks. The timeliness and accuracy of FBI-administered firearms background checks through NICS—particularly with regard to “delayed proceeds”—became a matter of controversy following the June 17, 2015, Charleston, SC, mass shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The assailant in this incident had acquired a pistol following a three-business-day-delayed sale under current law and an unresolved background check. While it has never been definitely determined whether the assailant’s arrest record would have prohibited the firearms transfer, this incident prompted gun control advocates to label the three-business-day delayed transfer provision of current law as the “Charleston loophole.” Gun rights supporters counter that firearms background checks should be made more accurate and timely, so that otherwise eligible customers are not wrongly denied a firearms transfer, and ineligible persons are not allowed to acquire a firearm.

The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585) would expand federal firearms ineligibility provisions related to domestic violence to include former dating partners under court-ordered restraints or protective orders and persons convicted of misdemeanor stalking offenses. Gun control advocates see this proposal as closing off the “boyfriend loophole.” Gun rights supporters are wary about certain provisions of this proposal that would allow a court to issue a restraining order ex parte; that is, without the respondent/defendant having the opportunity for a hearing before a judge or magistrate.

This report provides an overview of federal firearms background check procedures, analysis of recent legislative action, discussion about possible issues for Congress, and related materials.

Gun Control: National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Operations and Related Legislation

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Federal Firearms Statutes

- Firearms and Ammunition Ineligibility

- Firearms Commerce as a Business

- Private Party Transfers

- ATF Form 4473, Firearms Transaction Record

- 1993 Brady Act and Background Checks

- NICS Process Under Federal Law

- NICS Responses

- NICS-Queried Computer Systems and Files

- NICS Participation: POCs and Non-POCs

- NICS Transactions, November 30, 1998, Through 2018

- FBI NICS Section Brady Denials Appealed and Overturned

- NICS Denials and Firearm Retrieval Actions

- NICS Section Budget

- Improving NICS Access to Prohibiting Records

- 116th Congress and NICS Operations-Related Legislation

- The Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8)

- Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112)

- Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585)

- Qualifying Domestic Violence Protection Order (DVPO)

- Qualifying Misdemeanor Conviction of Domestic Violence (MCDV)

- "Intimate Partner" Definition

- "Misdemeanor Crime of Stalking"

- "Protection Orders" or "Court-Order Restraints"

Figures

- Figure 1. Point of Contact (POC) and Non-POC States

- Figure 2. Firearms-Related NICS Background Check Transactions

- Figure 3. Firearms-Related Background Checks Pursuant to the Brady Act

- Figure 4. Brady Act Denials Appealed and Overturned

- Figure 5. FBI Firearm Retrieval Action Referrals to ATF

- Figure 6. National Criminal History Improvement Program (NCHIP) and NICS Amendments Record Improvement Program (NARIP) Funding

Tables

- Table A-1. FBI NICS Section-Conducted Background Checks and Denials, 1998-2018

- Table A-2. FBI NICS Section Denials by Prohibited Category, 2018 and 1998-2018

- Table A-3. State and Local POC Agency-Conducted Firearms-Related Background Checks Facilitated Through NICS, November 30, 1998-2015

- Table A-4. State and Local POC Denials by Prohibiting Categories, 2014 and 2015

- Table C-1. Permanent Brady Permit Chart

- Table D-1. NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007

Summary

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) administers a computer system of systems that is used to query federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial criminal history record information (CHRI) and other records to determine an individual's firearms transfer/receipt and possession eligibility. This FBI-administered system is the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). NICS, or parallel state systems, must be checked and the pending transfer approved by the FBI or state point of contact before a federally licensed gun dealer may transfer a firearm to any customer who is not also a federally licensed gun dealer. Current federal law does not require background checks for intrastate (same state), private-party firearms transactions between nondealers, though such checks are required under several state laws.

In the 116th Congress, the House of Representatives passed three bills that would expand federal firearms background check requirements and firearms transfer/receipt and possession ineligibility criteria related to domestic violence.

The Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8), a "universal" background check bill, would make nearly all intrastate, private-party firearms transactions subject to the recordkeeping and NICS background check requirements of the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA). For the past two decades, many gun control advocates have viewed the legal circumstances that allow individuals to transfer firearms intrastate among themselves without being subject to the licensing, recordkeeping, and background check requirements of the GCA as a "loophole" in the law, particularly within the context of gun shows. Gun rights supporters often oppose such measures, underscoring that it is already unlawful to knowingly transfer a firearm or ammunition to a prohibited person. In addition, some observers object to these circumstances being characterized as a loophole, in that the effects of the underlying provisions of current law are not unintended or inadvertent.

The Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112) would lengthen the amount of time firearms transactions could be delayed pending a completed NICS background check from three business days under current law to several weeks. The timeliness and accuracy of FBI-administered firearms background checks through NICS—particularly with regard to "delayed proceeds"—became a matter of controversy following the June 17, 2015, Charleston, SC, mass shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The assailant in this incident had acquired a pistol following a three-business-day-delayed sale under current law and an unresolved background check. While it has never been definitely determined whether the assailant's arrest record would have prohibited the firearms transfer, this incident prompted gun control advocates to label the three-business-day delayed transfer provision of current law as the "Charleston loophole." Gun rights supporters counter that firearms background checks should be made more accurate and timely, so that otherwise eligible customers are not wrongly denied a firearms transfer, and ineligible persons are not allowed to acquire a firearm.

The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585) would expand federal firearms ineligibility provisions related to domestic violence to include former dating partners under court-ordered restraints or protective orders and persons convicted of misdemeanor stalking offenses. Gun control advocates see this proposal as closing off the "boyfriend loophole." Gun rights supporters are wary about certain provisions of this proposal that would allow a court to issue a restraining order ex parte; that is, without the respondent/defendant having the opportunity for a hearing before a judge or magistrate.

This report provides an overview of federal firearms background check procedures, analysis of recent legislative action, discussion about possible issues for Congress, and related materials.

Introduction

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) administers a computer system of systems that is used to query federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial criminal history record information (CHRI) and other records to determine if an individual is eligible to receive and possess a firearm.1 This FBI-administered system is the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). This system, or parallel state systems, must be checked and the transfer approved by an FBI NICS examiner or state point of contact (POC) before a federally licensed gun dealer may transfer a firearm to any customer who is not similarly licensed federally as a gun dealer.

Under current law, persons who buy and sell firearms repeatedly for profit and as a principal source of their livelihood must be licensed federally as gun dealers. Federally licensed gun dealers—otherwise known as federal firearms licensees (FFLs)—are permitted to engage in interstate and, by extension, intrastate (i.e., within a state) firearms commerce with certain restrictions. For example, they may not transfer a handgun to an unlicensed, out-of-state resident.

Conversely, persons who occasionally buy and sell firearms for personal use, or to enhance a personal collection, are not required to be licensed federally as a gun dealer. Those unlicensed persons, however, are prohibited generally from making interstate firearms transactions—that is, engaging in interstate firearms commerce—without engaging the services of a federally licensed gun dealer. On the other hand, current law does not require background checks for intrastate, private-party firearms transactions between nondealing, unlicensed persons, though such checks might be required under several state laws.2 Nevertheless, it is unlawful for anybody, FFLs or private parties, to transfer a firearm or ammunition to any person they have reasonable cause to believe is a prohibited person (e.g., a convicted felon, a fugitive from justice, or an unlawfully present alien).3

In the 116th Congress, the House of Representatives has passed three bills that would significantly expand the federal firearms background check requirements and the current prohibitions on the transfer or receipt and possession of firearms related to domestic violence. Those bills are the

- Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8), a bill to expand federal firearms recordkeeping and background check requirements to include private-party, intrastate firearms transfers;

- Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112), a bill to extend the amount of time allowed to delay a firearms transfer, pending a completed background check to determine an individual's eligibility; and

- Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585), a bill to expand firearms transfer or receipt and possession prohibitions to include dating partners with histories of domestic violence and stalking misdemeanors.

In addition, several multiple-casualty shootings have highlighted possibly systemic vulnerabilities in the NICS-related federal background check procedures, particularly with regard to making records on prohibited persons accessible to federal data systems queried as part of the federal background check process.4 This report provides an overview of federal firearms statutes related to firearms transactions in interstate and intrastate commerce, dealer licensing, receipt and possession eligibility, NICS background check procedures, analysis of recent legislative action, and discussion about possible issues for Congress.

Federal Firearms Statutes

Two major federal statutes regulate firearms commerce and possession in the United States. The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA; 18 U.S.C. §921 et seq.) regulates all modern (nonantique) firearms.5 In addition, the National Firearms Act, enacted in 1934 (NFA; 26 U.S.C. §5801 et seq.), regulates certain other firearms and devices that Congress deemed to be particularly dangerous because they were often the weapons of choice of gangsters in the 1930s.6 Such weapons include machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, suppressors (silencers), a catch-all class of concealable firearms classified as "any other weapon," and destructive devices (e.g., grenades, rocket launchers, mortars, other big-bore weapons, and related ordnance).

Congress passed both the NFA and GCA to reduce violent crimes committed with firearms. More specifically, the purpose of the GCA is to assist federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial law enforcement in the ongoing effort to reduce crime and violence.7 It is not intended to place any undue or unnecessary federal restrictions or burdens on citizens in regard to lawful acquisition, possession, or use of firearms for hunting, trapshooting, target shooting, personal protection, or any other lawful activity.8

Many observers have long noted that the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King provided the impetus to pass the GCA. Perhaps equally compelling were the August 1, 1966, University of Texas tower mass shooting9 and social unrest that accompanied the 1960s.10

Under the Attorney General's delegation, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) is the principal agency that administers and enforces these statutes.11 In addition, ATF administers several provisions of the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA) with regard to the importation of certain firearms, firearms parts, and ammunition that are also regulated under the GCA and NFA.12

For the most part, however, the FBI maintains NICS and administers the background check provisions of the GCA.13 Nonetheless, as discussed below, ATF is charged with investigating whether denied persons made false statements in connection with a firearms transfer; when filling out federal firearms transaction forms. In addition, ATF is also charged with firearms retrieval actions, whenever delayed transactions and incomplete background checks possibly result in prohibited persons acquiring firearms.

Firearms and Ammunition Ineligibility

The GCA sets firearms eligibility age restrictions under certain circumstances, as well as prohibits various categories of persons from firearms receipt and possession, among other factors. For example, as enacted, the GCA prohibits federally licensed gun dealers (i.e., FFLs) from transferring

- a long gun (shoulder-fired rifle or shotgun) or ammunition to anyone under 18 years of age; and

- a handgun or ammunition suitable for a handgun to anyone under 21 years of age.14

In 1994, Congress amended the GCA to prohibit anyone from transferring a handgun to a juvenile, or anyone under 18 years of age.15 Congress also made it unlawful for a juvenile to possess a handgun.16 Congress also provided exceptions to these juvenile transfer and possession prohibitions. Exceptions include temporary transfers in the course of employment in ranching or farming, in target practice, or hunting, all with the written consent of the parents or guardians and in accordance with federal and state laws; for self- or household-defense; or in other specified situations.17

Under the GCA, as amended, there are 10 categories of persons prohibited from receiving firearms. For 9 of those categories, those persons are also prohibited from possessing a firearm. More specifically, under 18 U.S.C. §922(g), there are nine categories of persons prohibited from shipping, transporting, receiving, or possessing a firearm or ammunition, which has been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce:18

- 1. persons convicted in any court of a felony crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year and state misdemeanors punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding two years;

- 2. fugitives from justice;

- 3. unlawful users or addicts of any controlled substance;19

- 4. persons adjudicated as "a mental defective,"20 found not guilty by reason of insanity, or committed to mental institutions;

- 5. unauthorized immigrants and nonimmigrant visa holders (with exceptions in the latter case);21

- 6. persons dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Armed Forces;

- 7. persons who have renounced their U.S. citizenship;

- 8. persons under court-order restraints related to harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner or child of such intimate partner;22 and

- 9. persons convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence.23

Under 18 U.S.C. §922(n), there is a 10th class of persons prohibited from shipping or transporting firearms or ammunition, or from receiving (but not possessing) firearms or ammunition that had been shipped or transported in interstate or foreign commerce:

- 1. persons under indictment in any court of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year.24

It is unlawful for any person under any circumstances to sell or otherwise dispose of a firearm or ammunition to any of the prohibited persons enumerated above, if the transferor (seller, federally licensed or unlicensed) has reasonable cause to believe that the transferee (buyer/recipient) is prohibited from receiving those items.25

Firearms Commerce as a Business

Under the GCA as enacted, persons who, or firms that, are "engaged in the business" of importing, manufacturing, or selling firearms must be federally licensed.26 In 1986, Congress amended the GCA to define the term "engaged in the business." For dealers it means:

a person who devotes time, attention, and labor to dealing in firearms as a regular course of trade or business with the principal objective of livelihood and profit through the repetitive purchase and resale of firearms, but such term shall not include a person who makes occasional sales, exchanges, or purchases of firearms for the enhancement of a personal collection or for a hobby, or who sells all or part of his personal collection of firearms.27

ATF issues federal firearms licenses to firearms importers, manufacturers, dealers, pawnbrokers, and collectors.28 As summarized by ATF in January 2016 guidance:

A person engaged in the business of dealing in firearms is a person who "devotes time, attention and labor to dealing in firearms as a regular course of trade or business with the principal objective of livelihood and profit through the repetitive purchase and resale of firearms."

Conducting business "with the principal objective of livelihood and profit" means that "the intent underlying the sale or disposition of firearms is predominantly one of obtaining livelihood and pecuniary gain, as opposed to other intents, such as improving or liquidating a personal firearms collection."

Consistent with this approach, federal law explicitly exempts persons "who make occasional sales, exchanges, or purchases of firearms for the enhancement of a personal collection or for a hobby, or who sells all or part of his personal collection of firearms."29

Under the GCA, only FFLs are allowed to transfer firearms commercially from one state to another, that is, to engage in interstate (or foreign) firearms commerce.30 At the same time, it would be highly improbable for any firearms business to compete successfully in the U.S. civilian gun market by only selling firearms manufactured in the state in which it does business; that is, to engage exclusively in intrastate commerce. As a practical matter, any person who deals in firearms as a business, either in interstate or intrastate commerce, needs to be federally licensed firearms manufacturer, importer, or dealer.31

FFLs may transfer a long gun—a shoulder-fired rifle or shotgun—to unlicensed persons from another state as long as such transfers are legal in both states and they meet in person to make the transfer.32 However, FFLs may not transfer a handgun to any unlicensed resident of another state.33 Since 1986 there have been no similar restrictions on the interstate transfer of ammunition, because Congress repealed those restrictions at the request of ATF.34 Furthermore, a federal firearms license is not required to sell ammunition; however, such a license is required to either manufacture or import ammunition.

In addition, FFLs are required to maintain bound logs of firearms acquisitions and dispositions to and from their business inventories by date, make, model, and serial number of individual firearms and transactions records for firearms sales to unlicensed, private persons.35 ATF periodically inspects these FFLs to monitor their compliance with federal and state law.

Under current law, there are statutory prohibitions against ATF, or any other federal agency, maintaining a registry of firearms or firearms owners.36 Nevertheless, the system of recordkeeping described above allows ATF agents to trace, potentially, the origins of a firearm from manufacturer or importer to a first retail sale and buyer. ATF agents assist other federal agencies, as well as state and local law enforcement, with criminal investigations.37 The ATF also makes technical judgements about firearms, including the appropriateness of manufacturing and importing certain makes and models of firearms and firearms parts.

As described in greater detail below, since November 30, 1998, all FFLs are required to initiate a background check for both handguns and long guns on any prospective firearms purchaser who is otherwise unlicensed federally to engage in firearms commerce as a business.38 The FBI facilitates these background checks nationwide through NICS. However, for some states, these FBI-facilitated background checks are routed to state or local authorities (points of contact, or POCs) for all firearms (handguns and long guns), or just for handgun transfers or permits for other states.

Private Party Transfers

For the most part, the GCA does not regulate firearms transactions between two unlicensed persons, who reside in the same state; that is, private-party, intrastate firearms transfers. Such transfers are not covered under current federal law as long as the parties are:

- not "engaged in the business" of dealing in firearms "as a regular course of trade or business with the principal objective of livelihood and profit";

- residents of the same state, where the transfer is made;

- not prohibited from receiving or possessing firearms; and

- the recipients are of age (at least 18 years old).39

It follows, therefore, that private firearms transactions between persons who are not "engaged in the business" of firearms dealing and, thus, who are not required to be federally licensed, are not covered by the recordkeeping or the background check provisions of the GCA if those parties reside in the same state. The meaning of "state of residence" is not defined in the GCA, but ATF has defined the term to mean:

The State in which an individual resides. An individual resides in a State if he or she is present in a State with the intention of making a home in that State. If an individual is on active duty as a Member of the Armed Forces, the individual's State of residence is the State in which his or her permanent duty station is located. An alien who is legally in the United States shall be considered to be a resident of a State only if the alien is residing in the State and has resided in the State for a period of at least 90 days prior to the date of sale or delivery of a firearm.40

However, these intrastate, private firearms transactions and other matters such as possession, registration, and the issuance of licenses to firearms owners may be covered by state laws or local ordinances. As noted above, unlicensed persons are prohibited generally from engaging in interstate and intrastate firearms commerce as a business; however, they are permitted to change state residences and take their privately owned non-NFA firearms with them under federal law, but they must comply with the laws of their new state of residence.41

The GCA generally prohibits an unlicensed person from directly transferring any firearm—handgun or long gun—to any other unlicensed person who resides in another state.42 Similarly, it is unlawful for an unlicensed person to receive a firearm from any unlicensed person who resides in another state. On the other hand, the GCA does not prohibit an unlicensed person from transferring a firearm to an out-of-state FFL, who may be willing to serve as a proxy for an unlicensed person to transfer a firearm or firearms to another unlicensed person who resides in the state where the FFL is licensed federally to do business. The facilitating, out-of-state FFL, in turn, must treat that firearm as if it were part of his business inventory, triggering the recordkeeping and background check provisions of the GCA. Generally, the facilitating FFL will charge a fee for such transactions conducted on behalf of an unlicensed person, which would likely be passed on to the unlicensed buyer/transferee in most cases.43

According to a 2015 survey, about one-in-five firearms transfers (22%) are conducted privately between unlicensed persons.44 In addition, a 2016 survey of state and federal prisoners—conducted by the Department of Justice (DOJ), Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS)—who possessed a firearm during the offense for which they were serving time suggested that

- more than half (56%) had either stolen the firearm (6%), found it at the scene of the crime (7%), or obtained it off the street or from the underground market (43%);

- most of the remainder (25%) had obtained the firearm from a family member or friend, or as a gift; and

- seven percent had purchased the firearm under their own name from a licensed firearm dealer, or FFL.45

Based on this survey data, private firearms sales at gun shows or any similar venue did not appear to be a significant source of guns carried by these offenders, while private transfers among family members, friends, and acquaintances did appear to account for a significant source of such firearms.46

ATF Form 4473, Firearms Transaction Record

The ATF Form 4473 and bound log of firearms acquisitions and dispositions are the essential federal documents underlying the recordkeeping process mandated by the GCA. Both FFLs and prospective, federally unlicensed purchasers must truthfully and completely fill out, and sign, an ATF Form 4473. Prospective purchasers attest to three things:

- 1. they are not prohibited persons,

- 2. they are who they say they are, and

- 3. they are the actual buyers.

Straw purchases are a federal crime. It is illegal for anybody to pose as the actual buyer, when in fact he is buying the firearm for someone else. Making any materially false statement to an FFL is punishable by a fine and/or up to 10 years imprisonment.47 There is also a lesser penalty for making any false statement or representation in any record (e.g., the Form 4473) that an FFL is required to maintain. Some straw purchases are also prosecuted under this provision. Violations are punishable by a fine and up to five years imprisonment.48

For their part, FFLs must verify a prospective purchaser's name, date of birth, state residency, and other information by examining government-issued identification, which most often include a state-issued driver's license.

FFLs must also file completed Form 4473s in their records. If a purchased firearm from FFLs should be recovered at any crime scene, ATF can trace a firearm from its original manufacturer or importer to the first-time FFL retail seller and the first-time private buyer (by the make, model, and serial number of the firearm). Successful firearms traces have generated leads in criminal investigations. In addition, aggregated firearms trace data provide criminal intelligence on illegal firearms trafficking patterns.

1993 Brady Act and Background Checks

After six years of debate, Congress passed the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, 1993 (Brady Act).49 Sponsors of the Brady Act initially proposed requiring a seven-day waiting period for handgun transfers. Instead, Congress amended the GCA with the Brady Act to require electronic background checks on any federally unlicensed individual seeking to acquire a firearm from an FFL. The Brady Act included both interim and permanent provisions.

Under the interim provisions, FFLs were required to contact local chief law enforcement officers (CLEOs) to determine the eligibility of prospective customers to be transferred a handgun. CLEOs were given up to five business days to make such eligibility determinations.50 From February 28, 1994, to November 29, 1998, under the interim provisions, 12.7 million firearms background checks (for handguns) were completed, resulting in 312,000 denials.51

The permanent provisions of the Brady Act became effective when the FBI activated the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) on November 30, 1998.52 Under these provisions, FFLs are required to initiate a background check through NICS on any prospective unlicensed customer, who seeks to acquire a firearm from them through a sale, trade, or redemption of firearms exchanged for collateral. Failure to conduct a NICS check is punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and one year imprisonment, or both.53 FFLs may engage in firearms transfers among themselves without conducting background checks.

The Brady Act includes a provision that prohibits the establishment of a registration system of firearms, firearms owners, or firearms transactions or dispositions with NICS-generated records, except for records on NICS denials for persons who are prohibited from receiving or possessing firearms under the GCA.54 In addition, in the FY2012 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress included a permanent appropriations limitation that requires the FBI to destroy background check records within 24 hours on persons who are eligible to receive firearms.55

From November 30, 1998, through 2018, the FBI NICS Section facilitated nearly 305 million firearms-related background checks transactions.56 Corresponding data on individual background checks and denials under the permanent provisions of the Brady Act are given and discussed below for both the FBI and for point of contact states that have chosen to either fully or partially implement the Brady Act.

NICS Process Under Federal Law

Building on the GCA firearms transaction recordkeeping process, the completed and signed ATF Form 4473 serves as the authorization for an FFL to initiate a check through NICS. The FFL submits a prospective firearms transferee's name, sex, race (or ethnicity), complete date of birth, and state of residence to the FBI through NICS.57 Social security numbers and other numeric identifiers are optional, but the submission of these data could possibly increase the timeliness of the background check and reduce misidentifications.58

NICS Responses

The NICS Section is to respond to an FFL or POC state official with a NICS Transaction Number (NTN) and one of four outcomes as follows, as described in greater detail below:

- 1. "proceed" with transfer or permit/license issuance, because a prohibiting record was not found;

- 2. "denied," indicating a prohibiting record was found;

- 3. "delayed proceed," indicating that the system produced information that suggested the prospective purchaser could be prohibited; or

- 4. "canceled" for insufficient information provided.59

In the case of a "proceed," the background check record is purged from NICS within 24 hours;60 "denied" requests are kept indefinitely. Under the third outcome, "delayed proceed," a firearms transfer may be "delayed" for up to three business days while NICS examiners or state designees (i.e., POCs) attempt to ascertain whether the person is prohibited.

"Delayed proceeds" are often the result of partial, incomplete, and/or even ambiguous criminal history records. The FBI NICS Section often must contact state and local authorities to make final firearms eligibility determinations. Under federal law, at the end of the three-business-day period following a "delayed proceed," FFLs may proceed with the transfer at their discretion if they have not heard from the NICS Section about those matters. The NICS Section, meanwhile, will continue to work the NICS adjudications for up to 30 days, at which point the background checks will drop out of the NICS examiner's queue if unresolved. At 88 days, all pending background check records are purged from NICS, even when they remain unresolved. About two-thirds of FBI NICS Section-administered background checks are completed within hours, if not minutes. Nearly one-fifth are delayed, but are completed within the three-business-day delayed transfer period.

If the FBI ascertains that the person is not in a prohibited status at any time within this 88-day period, then the FBI contacts the FFL through NICS with a "proceed" response. If the person is subsequently found to be prohibited, the FBI also contacts the FFL to ascertain whether a firearms transfer had been completed following the three-business-day "delayed transfer" period. If so, the FBI makes a referral to ATF. In turn, ATF initiates a firearms retrieval process. Such circumstances are referred as a "delayed denial," or more colloquially described as "lying and buying."

By comparison, standard denials are known as "lying and trying," under the supposition that most persons knew they were prohibited before they filled out the ATF Form 4473 and underwent a background check. ATF is also responsible for investigating standard denials based on FBI NICS Section referrals. As noted above, making any false statement to an FFL in connection with a firearms transfer is punishable under two GCA provisions.61

As part of the NICS process, under no circumstances are FFLs informed about the prohibiting factor upon which denials are based.62 However, denied persons may challenge the accuracy of the underlying record(s) upon which their denials are based.63 They would initiate this process by requesting (usually in writing) the reason for their denial from the agency that initiated the NICS check (the FBI or POC). Under the Brady Act, the denying agency has five business days to respond to the request.64 Upon receipt of the reason and underlying record for their denials, the denied persons may challenge the accuracy of that record. If the records are found to be inaccurate, the denying agency is legally obligated under the Brady Act to correct that record.65 If the denials are overturned within 30 days, the transfers in question may proceed.66 Otherwise, FFLs must initiate another background check through NICS on the previously denied prospective purchaser.67

NICS-Queried Computer Systems and Files

The feasibility of establishing NICS was largely founded upon the interstate sharing of federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial criminal history record information (CHRI) electronically through FBI computer systems and wide area network (WAN).68 Based on the prospective customer's name and other biographical descriptors, NICS queries four national data systems for records that could disqualify a customer from receiving and possessing a firearm under federal or state law. Those systems include the:

- Interstate Identification Index (III) for records on persons convicted or under indictment for felonies and serious misdemeanors;

- National Crime Information Center (NCIC) for files on persons subject to civil protection orders and arrest warrants, immigration law violators, and known and suspected terrorists;

- NICS Indices for federal and state record files on persons prohibited from possessing firearms, which would not be included in either III or NCIC; and

- Immigration-related databases maintained by the Department of Homeland Security's Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for non-U.S. citizens.69

An internal FBI inspections report found that access to N-DEx could have helped reveal that the individual, who later shot and killed nine people in a Charleston, SC, church, had an arrest record that was possibly sufficient grounds to deny him a firearms transfer.70 N-DEx is a repository of unclassified criminal justice files that can be shared, searched, and linked across jurisdictional boundaries.

For more information about these computer systems and files see Appendix B.

NICS Participation: POCs and Non-POCs

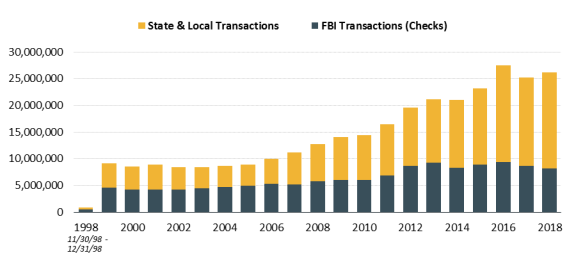

As shown in Figure 1, under the Brady Act, states may opt to conduct firearms-related background checks entirely or partially for themselves through state and local agencies serving as POCs, or they may opt to have such checks handled entirely by the FBI, through its NICS Section, which is part of the FBI's Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division.

- In 13 full POC states, an FFL initiates a firearms-related background check under the Brady Act by contacting a state or local agency serving as a POC for both long gun- and handgun-related transfers. These states are CA, CO, CT, FL, HI, IL, NJ, NV, OR, PA, TN, UT, and VA.

- In four partial POC states, an FFL initiates a firearms-related background check by contacting the state and local agencies serving as POCs for handgun transfers, and by contacting the NICS Section through a call center for long gun transfers. These states are MD, NH, WA, and WI.

- In three partial POC states, an FFL initiates a firearms-related background check under the Brady Act by contacting the state and local agencies serving as POCs for handgun permits, and contacts the NICS Section through a call center for long gun transfers. These states include IA, NC, and NE.

- In 36 jurisdictions (30 states, the District of Columbia, and the five U.S. territories), an FFL initiates a firearms-related background check by contacting the NICS Section through a call center for all firearms-related background checks, both long gun and handgun transfers. These thirty states are AK, AL, AR, AZ, DE, GA, ID, IN, KS, KY, LA, MA, ME, MI, MN, MO, MS, MT, ND, NM, NY, OH, OK, RI, SC, SD, TX, VT, WY, and WV. The five territories are AS, GU, MP, PR, and VI.

- Twenty-five states are "Brady exempt," meaning that certain valid, state-issued handgun and concealed carry weapons (CCW) permits may be presented to the FFL in lieu of a background check for firearms transfers through the NICS Section or state and local agencies serving as POCs. Those states are AK, AR, AZ, CA, GA, HI, IA, ID, KS, KY, LA, MI, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, NV, OH, SC, SD, TX, UT, WV, and WY. For further information, see Appendix C.

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. |

NICS Transactions, November 30, 1998, Through 2018

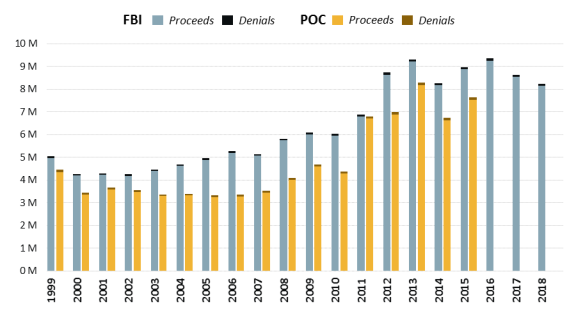

Figure 2 shows annual NICS transactions from November 30, 1998, through 2018 (20 years and one month). FBI transactions are shown on the base of the columns and the state and local POC transactions are shown on the top of the columns. Over this period, the FBI NICS Section and state and local agencies serving as POCs made 304.6 million NICS transactions. The NICS Section handled 128.6 million of these transactions (42.2% of all NICS transactions), whereas POCs initiated 176 million transactions (57.8% of all NICS transactions).

There is a one-to-one correspondence between FBI NICS transactions and individual background checks, and the 128.6 million FBI transactions—that is, background checks—resulted in 1.6 million denials (1.24%). Some of these FBI NICS Section-administered background checks were for firearms transactions involving multiple firearms; consequently, NICS transactions/background checks serve as an imperfect proxy for firearms sales.

Unlike FBI NICS background checks, some state background checks involved more than one background check transaction. In some states, for example, there may be permitting or licensing processes that could take several weeks and administrators would run multiple NICS queries on a single applicant. In other cases, a background check administrator might be unclear about an applicant's first and last name and would run two NICS queries on the applicant, reversing both names as first and last names. More fundamentally, some states are running periodic NICS queries on concealed carry permit holders. These periodic rechecks are not considered individual background checks.

The FBI does not have the state data to report on how many state and local background checks correspond with those transactions. Nor does the FBI report the total number of state and local firearms transfer or license denials. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), however, collects and analyzes the data as part of its Firearm Inquiry Statistics Program and reports annually on the total number of firearms-related background checks and related denials conducted under the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (P.L. 103-159).

In June 2017, BJS reported that state and local POCs had conducted 81.7 million firearms-related background checks from November 30, 1998, through 2015. According to the FBI, these POC-conducted background checks corresponded with 123.3 million NICS transactions. About 54.9% of these state transactions involved background checks related to firearms permits/licenses, an unreported percentage of which were for concealed carry permits. It is also noteworthy that some state-issued concealed-carry permits exempt the holder from any further background checks for non-NFA firearms. Hence, state and local NICS transactions also serve as an imperfect proxy for firearms sales. See Appendix C for a list of state permits that have been certified by ATF as Brady exempt.

From 2006 through 2018, total NICS transactions more than doubled from 10 million to 26 million or more, peaking in 2016 at 27.5 million and then dropping to 25.2 million in 2017, and rising again to 26.2 million in 2018. For the same years, total NICS transactions/checks handled entirely by the FBI NICS Section increased from 5.3 million to 9.4 million from 2006 to 2016, then dropped to 8.6 million in 2017, and dropped again to 8.2 million in 2018. In addition, NICS transactions handled by state and local agencies increased from 4.8 million to 18.2 million from 2006 to 2016, then dropped to 16.6 million in 2017, but rose again to 17.9 million in 2018.

In Figure 2 POC transactions account for an increasing proportion of all NICS transactions, but as discussed above some POC background checks involve more than one NICS transaction, whereas each NICS Section transaction corresponds with a single background check. As shown in Figure 3, for the years 1999 through 2015, the FBI CJIS Division's NICS Section conducted as many or more background checks than state or local POC agencies.

Figure 3 also shows the number of annual denials made pursuant to federal or state law. As noted above, over the 20 years and one month, the FBI CJIS Division's NICS Section conducted 128.7 million background checks, resulting in nearly 1.6 million denials, for an overall initial denial rate of 1.2%. As discussed below, about 2.7% of those denials were appealed and eventually overturned.

BJS reported that state and local POC agencies conducted nearly 81.7 million background checks from November 30, 1998, through 2015 for firearms transfers and permits.71 To date, BJS has not published any data for state and local POC agencies for 2016, 2017, and 2018. Nevertheless, for those 17 years and one month, POC checks resulted in nearly 1.46 million denials, for an overall denial rate of 1.8%, according to BJS. For the same years (and one month), the FBI NICS Section processed 102.4 million background checks, resulting in 1.27 million denials of firearms transfers, for an overall denial rate of 1.2%. See Appendix A for the data shown in Figure 3, as well as FBI and POC denials by prohibiting categories.

FBI NICS Section Brady Denials Appealed and Overturned

As with other screening systems, particularly those that are largely name-based, false positives occur as part of the NICS process, but the frequency of these misidentifications is unreported. Nevertheless, the FBI has taken steps to mitigate false positives (i.e., denying a firearms transfer to an otherwise eligible person). In July 2004, DOJ issued a regulation that established the NICS Voluntary Appeal File (VAF), which is part of the NICS Indices (described above). DOJ was prompted to establish the VAF to minimize the inconvenience incurred by some prospective firearms transferees (purchasers) who have names or birth dates similar to those of prohibited persons. So as not to be misidentified in the future, these persons agree to authorize the FBI to maintain personally identifying information about them in the VAF as a means to avoid future delayed transfers. As noted above, current law requires that NICS records on approved firearm transfers, particularly information personally identifying the transferee, be destroyed within 24 hours.

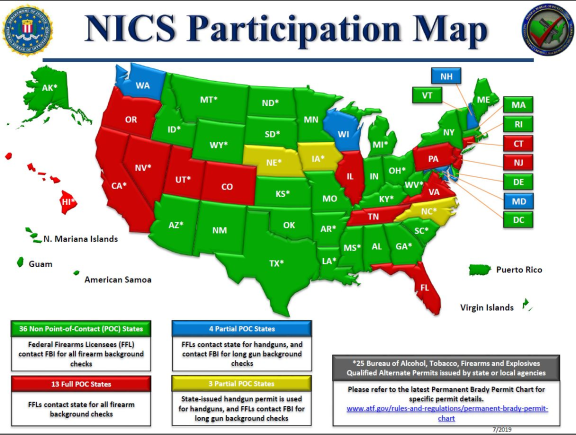

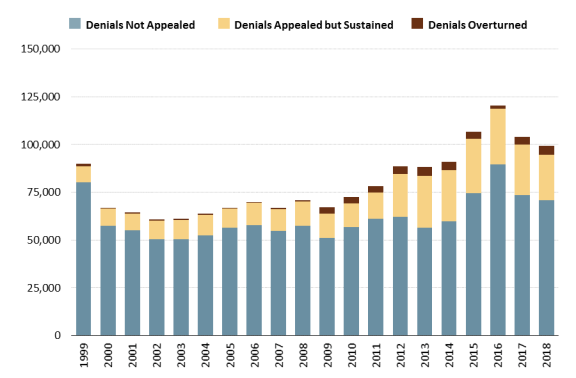

|

Figure 4. Brady Act Denials Appealed and Overturned 1999-2018 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. |

Figure 4 shows annual NICS Section denials, denials appealed but sustained, and denials overturned from November 30, 1998, through 2018. During this time, it appears that about one-fifth of NICS Section denials were appealed, and about one-tenth of those appealed denials were overturned, or an estimated 2.7% of NICS Section denials, according to the annual CJIS Division's NICS operations reports.72 The majority of these overturned denials were due to misidentifications.73 In any screening system, such as NICS, there is a balance between false positives and false negatives. Misidentifications and improperly interpreted criminal history and other records would constitute false positives. Allowing an otherwise prohibited person to acquire a firearm would constitute a false negative.

Under the GCA, there is also a provision that allows the Attorney General (previously, the Secretary of the Treasury) to consider petitions from a prohibited person for "relief from disabilities" and to have his firearms transfer and possession eligibility restored.74 Since FY1993, however, a limitation (or "rider") on the ATF annual appropriations for salaries and expenses has prohibited the expenditure of any appropriated funding for ATF to process such petitions from individuals.75

Conversely, under the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-180), any federal agency that submits any records on individuals considered to be too mentally incompetent to be trusted with a firearm under the GCA must provide an avenue of administrative relief to those individuals, so if their mental health or other related conditions improve, their firearms rights and privileges may be restored. As a condition of grant eligibility, as described below, states must provide similar administrative avenues of relief for those purposes, that is, "disability relief." See Appendix D for a list of states that have enacted and implemented ATF-certified relief from disability programs under P.L. 110-180.

NICS Denials and Firearm Retrieval Actions

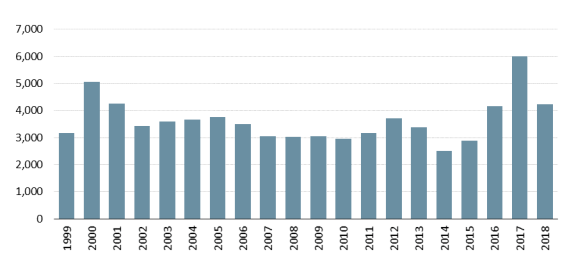

Figure 5 shows annual NICS denials and firearm retrieval action from November 30, 1998, through 2018. For the 20 years and one month, the NICS section made an average of 3,600 firearm retrieval action referrals to the ATF annually for follow-up. In many of these cases, an otherwise prohibited person had been transferred a firearm. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), following up on these possibly illegal firearms receipts—or "delayed denial investigations"—consumes an increasing and considerable amount of ATF resources. For example, such investigations accounted for 32% of ATF investigations opened in FY2003 and 53% in FY2013.76

|

Figure 5. FBI Firearm Retrieval Action Referrals to ATF 1999-2018 |

|

|

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation |

It appears that in a relatively small percentage of cases the suspected offenders have been prosecuted federally for what is commonly known as either "lying and buying" or "lying and trying." According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), ATF processed 3,933 delayed denials in FY2017. Of those denials, 38 cases were referred to U.S. Attorney's Offices for prosecution. Nine of those cases were federally prosecuted.77

Also in a relatively small percentage of cases, an FFL could potentially proceed with a firearms transfer after the three-business-day delayed transfer period has expired, but never receive a final NICS determination; or the FFL could potentially decline to transfer the firearm to an unlicensed customer until he received a definitive NICS Section response, which the FFL may not receive from the FBI.78

NICS Section Budget

NICS is maintained and administered by the FBI Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division and its NICS Section, located in Clarksburg, WV. Recent increases in the volume of firearms-related commerce and attendant background checks have strained the NICS Section and additional staff and funding has been requested by the FBI, which Congress has provided through appropriated funding.79 For FY2016, the NICS Section program budget allocation was $81 million and 668 funded permanent positions.80 As described below, for FY2019, the FBI anticipated that the NICS Section program budget would be allocated $103 million and 679 positions, representing a $22 million and 11 position increase over FY2016. The Administration's FY2020 request would increase FY2020 NICS Section program budget to $115 million and 719 positions.

For FY2017, the Obama Administration requested $121.1 million for the NICS program, including an additional $35 million. Of this budget increase $15 million was requested to sustain 75 professional support positions funded for FY2016; and another $20 million was requested to hire 160 contractors to support NICS firearms background checks and related activities. The remaining $5.1 million was requested to annualize operational costs associated with the NICS base budget. Report language accompanying both the Senate- and House-reported FY2017 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies appropriations bills (S. 2837 and H.R. 5393) indicated that those bills would have provided the requested $35 million for NICS. The Explanatory Statement accompanying H.R. 244, submitted by the House Committee on Appropriations Chair, Representative Rodney Frelinghuysen, indicated that P.L. 115-31 included $511.3 million for CJIS, and that this amount would fully support CJIS programs, including NICS.81

For FY2018, the Trump Administration requested $79.2 million for the NICS program, including an additional $8.9 million to fund an additional 85 permanent positions.82 Such an increase would have brought the number of funded permanent positions for the NICS program to 676.83 According to the FBI, the enacted NICS budget allocation for FY2018 was $111.3 million and 679 positions.84 For FY2019, the Administration did not request any budget increases for the FBI or NICS. The FBI anticipated that the FY2019 NICS budget and staff allocation would be about $103 million and 679 positions.85

For FY2020, the Administration has requested a NICS budget increase of $4.23 million and 40 positions and $7.8 million in base budget increases, which would bring the total FY2020 NICS budget to $115 million and 719 positions.86 House-report language accompanying the FY2020 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act (H.R. 3055) indicates that this bill would fully support the NICS Section operations and activities for the upcoming fiscal year.87

Improving NICS Access to Prohibiting Records

The efficacy of NICS and firearms-related background checks is dependent in large part on state and local governments making criminal history record information (CHRI), as well as other disqualifying records (e.g., mental incompetency records), accessible electronically to several different national data sharing systems maintained by the FBI. As described above, those systems include principally the III, NCIC, and the NICS Indices. Congress, meanwhile, has authorized two grant programs to incentivize state and local governments to maintain CHRI and other disqualifying records and make them accessible to NICS in a timely manner.

Under the Brady Act, Congress authorized a grant program known as the National Criminal History Improvement Program (NCHIP), the initial goal of which was to improve electronic access to firearms-related disqualifying records, felony indictment, and conviction records, for the purposes of both criminal and noncriminal background checks.

Congress passed the NICS Improvement Amendments Act (NIAA) of 2007 (P.L. 110-180)88 following the April 16, 2007, Virginia Tech tragedy.89 Along the lines of the Brady Act, the NIAA included provisions designed to encourage states, tribes, and territories to make available to the Attorney General certain records related to persons who are disqualified from acquiring a firearm, particularly records related to domestic violence misdemeanor convictions and restraining orders, as well as mental health adjudications. As a framework of incentives and disincentives, the Attorney General was authorized to make grants, waive grant match requirements, or reduce law enforcement grant assistance depending upon a state's compliance with the act's goals of bringing firearms-related disqualifying records online.

The Attorney General was required to report annually to Congress on federal department and agency compliance with the act's provisions. The Attorney General, in turn, has delegated responsibility for grant-making and reporting to DOJ's Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). BJS designated the grant program under the act as the "NICS Act Record Improvement Program (NARIP)," although congressional appropriations documents generally referred to it as "NICS improvement" or the "NICS Initiative" program.

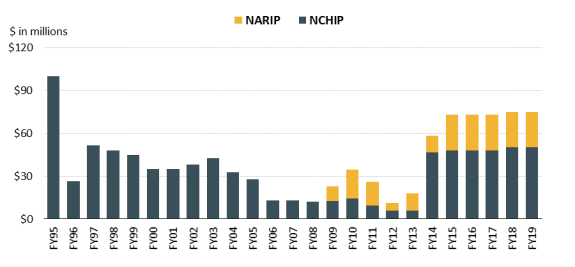

Figure 6 shows annual congressional appropriations for NCHIP and NARIP for FY1995-FY2019. Over this 25-year period, Congress has appropriated nearly $859 million for NCHIP and $201 million for NARIP, for a total of $1.06 billion. During this time period, NCHIP grants were made available to states for purposes other than just identifying persons ineligible to receive firearms, such as identifying persons ineligible to hold positions involving vulnerable populations (e.g., children, disabled, and elderly). Nevertheless, the principal purpose of NCHIP was to improve the accuracy and timeliness of background checks, particularly those administered pursuant to the Brady Act.

For FY2009 through FY2013, Congress authorized $1.3 billion in appropriations for NARIP. Actual appropriations, however, fell short of such authorizations. For those fiscal years, Congress appropriated $63.6 million for NARIP, although neither the House nor Senate Committee on Appropriations adopted "NARIP" as a grant program designation. Instead, the appropriations statute provided such funding for the grant-making activities authorized under P.L. 110-180.

For FY2014 through FY2019, Congress continued to appropriate funding for both NCHIP and the grant-making activities authorized under P.L. 110-180 (i.e., NARIP) under the "NICS Initiative," even though the authorization for appropriations under P.L. 110-180 had lapsed. For those years, Congress appropriated $429.5 million for NCHIP and NARIP, or the "NICS Initiative," of which $137 million was set aside for purposes authorized under NIAA, bringing total appropriated NARIP funding for FY2009 through FY2019 to $200.6 million. Under the NICS Initiative, BJS has awarded a total of $142 million in NARIP grants to 30 states and one Native American tribe from FY2009 through FY2018.90 To date, however, BJS has not levied any of the reward and penalty provisions of NIAA, possibly because of methodological difficulties in ascertaining state progress towards meeting the goals of this act.

With NICS Initiative grants (NCHIP and NARIP) in part, state and local governments have increased the availability of mental health- and domestic violence-related records to NICS Indices and other data systems queried by NICS. For example, from CY2007 to CY2018, the number of mental health records in the NICS Indices increased from 518,49991 to 5,419,894,92 a 9.5-fold increase. The number of misdemeanor crime of domestic violence (MCDV) records in the NICS Indices increased from 46,28693 to 175,376,94 nearly tripling (a 278.9% increase). Many instances domestic violence misdemeanor crimes are serious enough in nature that the records are deposited in the III, meaning the offenders were fingerprinted.

A Department of Justice-sponsored report found that in many cases such criminal records are not adequately flagged in the III for firearms eligibility determination purposes, leading to NICS delayed transfers in some cases.95 Inadequately flagged records in the III increase the possibility that a prohibited person might be transferred a firearm after the NICS three-business-day delayed transfer period expires. Similarly, it was reported that domestic violence protection orders are increasingly being placed in the NICS Indices, even though the authors of the report argued that it would probably be most appropriate to place such records in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), so that such records would be available to law enforcement for purposes besides firearms-related background checks.96

Responding to these issues in part, Congress passed the Fix NICS Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-141). The act reauthorized NARIP, as well as authorized appropriations of $125 million annually for FY2018 through FY2022. It also reauthorized NCHIP itself, as well as authorized appropriations of $250 million annually for FY2018 through FY2022. For FY2018, Congress appropriated $75 million for the "NICS Initiative," of which $25 million was set aside for purposes authorized under NIAA, as amended by the Fix NICS Act (or NARIP).97 For FY2019, Congress appropriated the same amount and set aside.98

For FY2020, the Administration has requested $65 million for NCHIP and $10 million for NARIP.99 The House-reported Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations bill (H.R. 3055; H.Rept. 116-101) would provide $80 million for these grant programs under the "NICS Initiative," of which $27.5 million would be set aside for purposes authorized under NIAA, as amended by the Fix NICS Act (or NARIP).100

116th Congress and NICS Operations-Related Legislation

This final section of the report briefly summarizes NICS-related legislative action to date in the 116th Congress. It then provides a summary and some analysis of three bills that have passed the House and await Senate action.

In the 116th Congress, the House has passed three bills that would expand federal firearms-related background check requirements. On January 8, 2019, Representative Mike Thompson introduced the Bipartisan Background Checks Bill of 2019 (H.R. 8), a bill that would require a background check for most private-party, intrastate firearms sale, or "universal" background checks.101 On February 6, 2019, the House Committee on the Judiciary held a hearing on "Preventing Gun Violence in America."102 On February 8, 2019, Representative James Clyburn introduced the Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112), a bill to lengthen the number of days a firearms transfer could be delayed pending a final firearms eligibility determination. On February 13, 2019, the House Committee on the Judiciary amended and ordered reported both bills: H.R. 8 (H.Rept. 116-11) and H.R. 1112 (H.Rept. 116-12). On February 27 and 28, 2019, respectively, the House amended and passed H.R. 8 and H.R. 1112.

On March 7, 2019, Representative Karen Bass introduced the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585). On March 27, 2019, the House Committee on the Judiciary amended and reported H.R. 1585. This bill includes provisions that would expand existing firearms transfer/receipt and possession prohibitions to include dating partners with histories of domestic violence and persons convicted of stalking-related misdemeanor offenses. The House passed H.R. 1585 on April 4, 2019.

Also, of note, on March 13, 2019, the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies held a hearing on "Gun Violence Prevention and Enforcement."103 On March 18, 2019, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) released its FY2020 congressional budget request that includes a $4.2 million increase for the NICS, which would bring the total program budget to $114.7 million for FY2020. 104 On the same date, the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) released its congressional budget request that includes $75 million for state, local, tribal, and territorial governments to upgrade criminal and mental incompetency records and make those records accessible to NICS for firearms eligibility determination purposes.105

On June 3, 2019, the House Committee on Appropriations reported an FY2020 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies (CJS) Appropriations bill (H.R. 3055, H.Rept. 116-101). House report language indicates that the bill would fully support the FBI request for increased NICS funding.106 The bill would also provide $80 million for OJP-administered NICS improvement grants under NCHIP and NARIP.107

On September 26, 2019, Senate Committee on Appropriations reported an FY2020 CJS Appropriations bill (S. 2584; S.Rept. 116-127). Senate report language indicates that the bill $131 million to increase NICS capacity and efficacy.108 This amount is $16.3 million above the Trump Administration's FY2020 request. The bill would also provide $78.3 million for OJP-administered NICS improvement grants under NCHIP and NARIP, of which $25 is for the latter program.109

In addition, on March 26, 2019, the Senate Committee on the Judiciary held a hearing on "Red Flag Laws: Examining Guidelines for State Action."110 Seventeen states and the District of Columbia have passed "Red Flag" laws.111 These laws essentially allow concerned persons, including family members in some cases, to petition a court to file an extreme risk protection order against an individual that would allow for the suspension of that individual's firearms eligibility under certain circumstances. These state laws vary considerably from state to state. Related proposals in the 116th Congress would make subjects of such protective orders ineligible to receive or possess firearms under federal law in any state or would establish grant programs to encourage states to adopt such laws.

On September 10, 2019, the House Committee on the Judiciary ordered reported such a bill, the Extreme Risk Protection Order Act (H.R. 1236).112 In addition, this Committee also ordered reported the Disarm Hate Act (H.R. 2708), which make persons convicted of a misdemeanor hate crime ineligible to receive or possess a firearm or ammunition.113

The Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8)

The Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 8), a "universal" background check bill, would expand federal firearms background checks and, hence, recordkeeping requirements under the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA; 18 U.S.C. §921 et seq.) to include firearms transfers made in the same state (intrastate) between unlicensed persons. H.R. 8 would essentially prohibit unlicensed persons from transferring a firearm to any other unlicensed person, unless a federally licensed firearms dealer, or FFL, takes possession of such firearm and facilitates such a transaction by running a background check on the unlicensed prospective transferee (buyer).

H.R. 8 includes exceptions for transfers between immediate family members; U.S. military, law enforcement members, or armed private security professionals in the course of official duties; temporary transfers under circumstances involving an imminent threat of bodily harm or death; and legitimate activities involving target shooting, hunting, trapping, or fishing.

H.R. 8 would prohibit any implementing regulations that would (1) require FFLs to facilitate private firearms transactions; (2) require unlicensed sellers or buyers to maintain any records with regard to FFL-facilitated background checks; or (3) place a cap on the fee FFLs may charge for facilitating a private firearms transfer. H.R. 8 would also prohibit FFLs from transferring possession of, or title to, any firearm to any unlicensed person, unless the FFL provides notice of the proposed private firearm transfer prohibition under this bill. Further, H.R. 8 would extend a provision of current law that prohibits the DOJ from charging a fee for a NICS background check.

Under H.R. 8, facilitating FFLs would be required to treat firearms to be transferred on behalf of any unlicensed persons as if they were part of their business inventory. Thus, they would be required to comply with the GCA recordkeeping and background check requirements. As part of this process, FFLs would enter the firearm(s) to be exchanged into their bound log of firearms acquisitions and dispositions. The FFLs and unlicensed prospective transferees would then complete and sign a firearms transaction forms (ATF Form 4473) under penalty of law that everything entered onto that form was truthful. FFLs would then initiate a background check on the intending transferee through NICS. And either the FBI NICS Section or a state or local authority—point of contact (POC)—would conduct a background check to determine an intending transferee's firearms eligibility. Such a requirement, if enacted, would close off what some have long characterized as the "Gun Show loophole."114

For the past two decades, many gun control advocates have viewed the legal circumstances that allow individuals to transfer firearms intrastate among themselves without being subject to the licensing, recordkeeping, and background check requirements of the GCA as a "loophole" in the law, particularly within the context of these intrastate, private transactions at gun shows and other public venues or through the internet.115 Gun control advocates also maintain that expanding background checks to cover intrastate, private-party firearms sales would help stem gun trafficking; that is, the illegal diversion of firearms from legal channels of commerce to the black market, where federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial laws could be evaded. They maintain that prohibited persons or their friends or acquaintances could easily buy a firearm at a gun show, from an online seller, or in a person-to-person "private" sale.116 They also point to studies that suggest that there is moderate evidence that expanded background checks might reduce firearms-related homicides and suicides.117 Gun control advocates underscore that 20 states and the District of Columbia (DC) currently have laws that require background checks for certain types of firearms transfers not currently covered by federal law. Although these laws vary considerably from state to state, 11 states and DC require background checks for nearly all firearms transfers.118

Gun rights advocates contend that intrastate, private transfers are regulated already under federal law, in that it is a felony to transfer a firearm or ammunition knowingly to an underage or prohibited person.119 They contend further that most criminals would not submit to a background check. They ask, "Why would anyone submit to a background check unless they believed they were not prohibited and would pass?"

Moreover, they argue that making private-party, intrastate transfers subject to the recordkeeping and background check provisions of the GCA could potentially criminalize firearms transfers under circumstances that could be characterized as legitimate and lawful. For example, it has been argued that H.R. 8 might prohibit a person from sharing a firearm with another person while target shooting on one's own property.120 Although H.R. 8 would provide exceptions for "temporary transfers" for target shooting and other related activities, some gun rights advocates argue that such exceptions are too narrow. For example, they argue further that H.R. 8 would prohibit a person from loaning a neighbor a firearm for a hunting trip with a background check being required for both the loan to the neighbor and the return of the firearm to its lawful owner. Perhaps more fundamentally, H.R. 8 would prohibit a person from loaning a firearm to another person—who may be facing some threat of death or serious bodily injury—for self-defense purposes, unless that threat were "imminent."121

Gun rights advocates might also see such a measure as a significant step towards a national—albeit decentralized—registry of firearms and firearms owners, since its practical implementation would likely necessitate recordkeeping on such transfers.122 Such advocates cite an Obama Administration, Department of Justice official who observed that "universal background checks" are unenforceable without a comprehensive registry of firearms.123

Legislation to expand federal recordkeeping and background check requirements to cover private, intrastate firearms transfers saw action in the 106th and 108th Congresses following the April 20, 1999, Columbine, CO, high school mass shooting;124 in the 113th Congress following the December 14, 2012, Newtown, CT, elementary school mass shooting;125 and in the 114th Congress following the December 2, 2015, San Bernardino, CA, social services center all-staff meeting and June 12, 2016, Orlando, FL, Pulse night club mass shootings.126

Over time, related legislative proposals have varied in the scope and type of intrastate, private party (nondealer) firearms exchanges between federally unlicensed persons that would fall under their respective background check provisions. Since the 113th Congress, such proposals fall under two basic types that, respectively, have been labeled as either "Universal" or "Comprehensive" background check bills.

"Comprehensive" background checks would cover transfers at gun shows and similar public venues (e.g., flea markets and public auctions) and firearms that are advertised via some public fora, including newspaper advertisements and the Internet.127

"Universal" background checks would cover private transfers under a much wider set of circumstances (sales, trades, barters, rentals, or loans), with more limited exceptions.128

In the Senate, from the 113th Congress forward, the principal sponsors of "universal" background check bills have been Senators Charles Schumer, Christopher Murphy, and Richard Blumenthal.129 The principal sponsors of "comprehensive" background check amendments have been Senators Joe Manchin and Pat Toomey.130 "Universal" background check bills were introduced in the House in the 113th and 114th Congresses.131 While Representatives Peter King and Mike Thompson introduced proposals that were similar to Manchin-Toomey "comprehensive" background check bills in the past three Congresses,132 they have sponsored and supported a "universal" background check proposal (H.R. 8) in the 116th Congress.

Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112)

The House-passed Enhanced Background Checks Act of 2019 (H.R. 1112) would revise the GCA background check provision to lengthen the delayed sale period, which is three business days under current law. Under H.R. 1112, for background checks that do not result in a "proceed with transfer" or "transfer denied," the FBI NICS Section and POC state officials would have 10 business days to place a hold on a firearms-related transaction. At the end of 10 business days, the prospective transferee could petition the Attorney General for a final firearms eligibility determination. If the FFL does not receive a final determination within 10 days of the date of the petition, he or she could proceed with the transfer.

The timeliness and accuracy of FBI-administered firearms background checks through NICS—particularly with regard to "delayed proceeds"—became a matter of controversy following the June 17, 2015, Charleston, SC, mass murder at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The assailant had acquired a handgun from an FFL in the Columbia, SC, area. According to press accounts, the NICS check on the assailant was initiated on April 11, 2015 (a Saturday).133 The FBI found an arrest record for him, but the arrest record was ambiguous with regard to the arrest's final disposition and the assailant's firearms receipt and possession eligibility. Therefore, the NICS response to the FFL was to delay the transfer for three business days as required under federal law. At his discretion, the FFL made the transfer on April 16, 2015 (a Thursday) as allowed under federal law. According to FBI, the NICS check would have remained active in the NICS examiner's queue for 30 days (until May 11, 2015), and would have remained in an "active status" in the NICS system for 88 days (until July 8, 2015).

According to the assailant's arrest record, he had been processed for arrest by the Lexington County, SC, Sheriff's Department, so the FBI contacted the Lexington County court, sheriff's department, and prosecutor's office. The Lexington County Sheriff's Department responded that it did not have a record on the alleged assailant and advised the NICS examiner to contact the City of Columbia, SC, Police Department. However, the NICS examiner contacted the West Columbia, SC, Police Department, because it was listed on the NICS contact sheet for Lexington County. In turn, the West Columbia Police Department responded that it did not have a record on the alleged assailant either. The NICS examiner reportedly focused on Lexington County and missed the fact that the City of Columbia, SC, Police Department was listed as the contact for Richland County, the county in which most of the City of Columbia, SC, is located. Consequently, the NICS examiner did not contact the Columbia, SC, Police Department, the agency that actually held the arrest record for the assailant.134

If the FBI had ascertained during the 88 days that this person was prohibited, the NICS examiner would have likely contacted the FFL to verify whether a firearms transfer had been made after the three-business-day delay, and then would have notified the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) and a firearms retrieval action would have possibly been taken by that agency. In this case, the FBI did not ascertain that the assailant was possibly a prohibited person until after the June 17, 2015, mass shooting. Some gun control advocates have characterized these circumstances as the "Charleston loophole."135

In addition to the "Charleston loophole," gun control advocates sometimes refer to "delayed proceeds" that could result in a possibly prohibited person acquiring a firearm after three business days have expired as "default proceeds."136 They argue that extending the delayed proceed period would reduce the chance that an otherwise prohibited person might inadvertently be transferred a firearm, a circumstance that would likely necessitate an ATF firearms retrieval action had more time been allotted to complete the background check.

According to data acquired by a gun control advocacy group, about 3.59% of FBI-administered background checks in 2017 were unresolved after a delayed proceed response and the three-business-day window had passed. To this advocacy group, this suggested that a relatively small number of people (310,232) would be affected, and any inconvenience to them would be outweighed by increasing the probability that a prohibited person might be prevented from acquiring a firearm.137

According to the FBI, it referred 6,004 "delayed denial" cases to the ATF in 2017 that could have possibly resulted in a finding of ineligibility and subsequent firearms retrieval action. In addition, the FBI reported that 4,864 of those cases involved individuals who were possibly prohibited and had probably acquired a firearm.138