The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Block Grant: Legislative Issues in the 116th Congress

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; P.L. 104-193). That law culminated four decades of debate about how to revise or replace the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program. Most AFDC assistance was provided to families headed by single mothers who reported no work in the labor market, and the debates focused on whether such aid led to dependency on assistance by discouraging work and the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

TANF provides a fixed block grant to states ($16.5 billion total per year) that has not been adjusted at either the national or state levels since 1996. The TANF block grant is based on expenditures in the AFDC program in the early to mid-1990s, and thus the distribution of funds among the states has been “locked in” since that time. The purchasing power of the block grant has also declined over time due to inflation. Since 1997, it has lost 36% of its initial value.

The debates that led to the creation of TANF in 1996 focused on the terms and rules around public assistance to needy families with children. However, PRWORA created TANF as a broad-purpose block grant. States may use TANF funds “in any manner that is reasonably calculated” to achieve the block grant’s statutory purposes, which involve TANF providing states flexibility to address the effects or the root causes of economic and social disadvantage of children. For pre-TANF programs, public assistance benefits provided to families comprised 70% of total spending. In FY2018, such public assistance comprised 21% of all TANF spending. States spend TANF funds on activities such as child care, education and employment services (not necessarily related to families receiving assistance), services for children “at risk” of foster care, and pre-kindergarten and early childhood education programs. There are few federal rules and little accountability for expenditures other than those made for assistance.

Before the 1996 law, many states experimented with programs to require work or participation in job preparation activities for AFDC recipients. PRWORA established “work participation requirements.” Most of these requirements relate to a performance system that applies to the state as a whole, and are not requirements that apply to individuals. The system requires states to meet a minimum work participation rate (WPR). The complex rules of the WPR can be met through several different routes in addition to engaging unemployed recipients in job preparation activities: caseload reduction, state spending beyond what is required under TANF, and assistance to needy parents who are already working. In FY2018, all but one state met the participation standard. A total of 18 states met their minimum WPR through caseload reduction alone.

Spending on assistance and the number of individuals receiving assistance have both declined substantially since the mid-1990s. The reduction in the assistance caseload was caused more by a decline in the percentage of those who were eligible receiving benefits than a decline in the number of people who met TANF’s state-defined definitions of financial need. Assistance under TANF alleviates less poverty than it did under AFDC. While there have been expansions in other low-income assistance programs since PRWORA was enacted, such as the refundable tax credits from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the child tax credit, those programs do not provide ongoing assistance on a monthly basis.

Some of the TANF reauthorization bills introduced in the 115th and 116th Congresses attempt to focus a greater share of TANF dollars on activities related to assistance and work. Additionally, these bills would revise the system by which state programs are assessed on their performance in engaging assistance recipients in work or job preparation activities.

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Block Grant: Legislative Issues in the 116th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- The Debates That Led to the Creation of TANF

- TANF Funding Levels and Distribution among the States

- Distribution of Funding Among the States

- Impact of Inflation on the Value of the Block Grant

- Contingency Funds for Recessions

- Legislation Related to Funding Levels and Distribution

- Use of Funds

- Authority to Spend TANF Funds and Count MOE Dollars

- TANF Expenditures

- Legislative Proposals on the Use of TANF Funds

- Work Requirements

- Performance Measurement: The Minimum Work Participation Rate

- Alternative Ways of Meeting the Minimum WPR

- Meeting the Minimum WPR in 2018

- Sanctions for Refusing to Comply with Work Requirements

- TANF Legislation Addressing Work Participation

- Outcome Measures of Performance

- Universal Engagement

- The TANF Caseload Decline and Child Poverty

- Caseload Decline: Reduction in Need or Fewer Families in Need Receiving Benefits?

- Child Poverty and Its Alleviation

- TANF Legislation Addressing the Caseload Decline and Child Poverty

- Conclusion

Figures

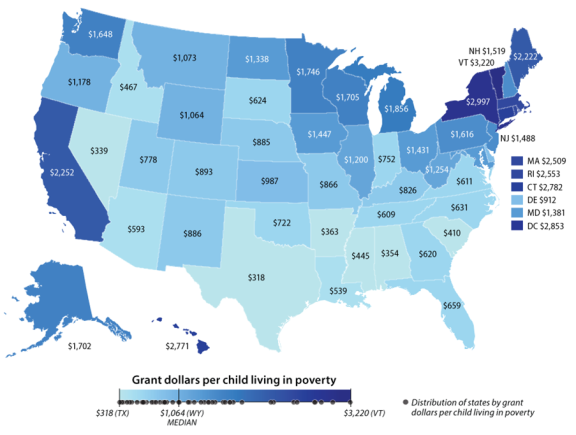

- Figure 1. State Family Assistance Grant Dollars Per Child in Poverty, by State

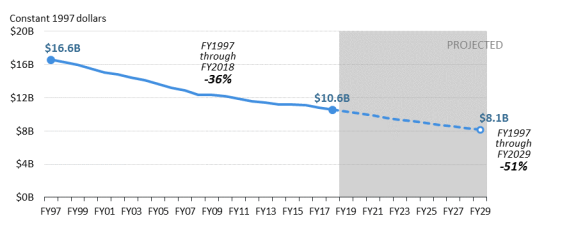

- Figure 2. Purchasing Power of the TANF Basic Block Grant: FY1997–FY2029

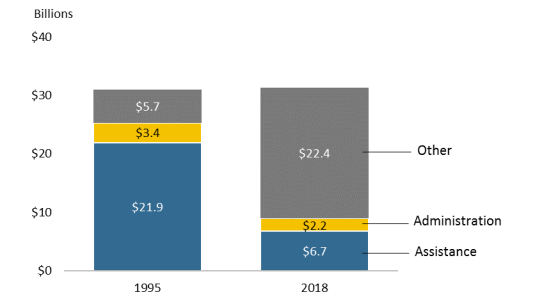

- Figure 3. Total Federal and State Spending on Assistance Under AFDC in FY1995 and Under TANF in FY2018

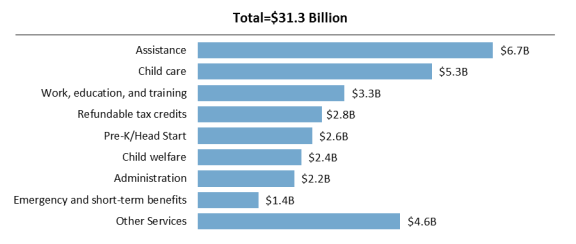

- Figure 4. Federal and State TANF Expenditures by Activity, FY2018

- Figure 5. Federal and State TANF Expenditures by Category and State, FY2018

- Figure 6. Participation in Employment or Job Preparation Activities Among TANF Work-Eligible Individuals, FY2018

- Figure 7. Estimated AFDC- and TANF-Eligible Populations and the Share Receiving Benefits: Selected Years 1995 to 2016

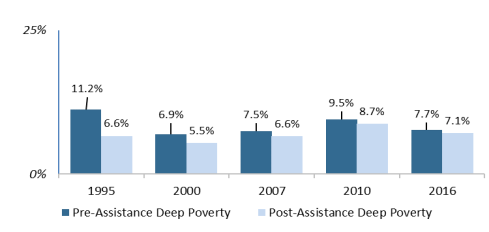

- Figure 8. Child Poverty Rates Based on Pre- and Post-assistance Income, Selected Years 1995 to 2016

- Figure 9. Child Deep Poverty Rates Based on Pre- and Post-assistance Income, Selected Years 1995 to 2016

Tables

- Table 1. TANF Legislation: Funding Levels and Distribution of Funds

- Table 2. TANF Legislation: Use of TANF and MOE Funds for Benefits and Services

- Table 3. TANF Legislation: Work Participation Provisions

- Table 4. Pre- and Post-assistance Poverty Gaps for Families with Children, Selected Years 1995 to 2016

- Table 5. TANF Legislation: Child Poverty Reduction and Incentives for Caseload Reduction

Summary

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; P.L. 104-193). That law culminated four decades of debate about how to revise or replace the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program. Most AFDC assistance was provided to families headed by single mothers who reported no work in the labor market, and the debates focused on whether such aid led to dependency on assistance by discouraging work and the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

TANF provides a fixed block grant to states ($16.5 billion total per year) that has not been adjusted at either the national or state levels since 1996. The TANF block grant is based on expenditures in the AFDC program in the early to mid-1990s, and thus the distribution of funds among the states has been "locked in" since that time. The purchasing power of the block grant has also declined over time due to inflation. Since 1997, it has lost 36% of its initial value.

The debates that led to the creation of TANF in 1996 focused on the terms and rules around public assistance to needy families with children. However, PRWORA created TANF as a broad-purpose block grant. States may use TANF funds "in any manner that is reasonably calculated" to achieve the block grant's statutory purposes, which involve TANF providing states flexibility to address the effects or the root causes of economic and social disadvantage of children. For pre-TANF programs, public assistance benefits provided to families comprised 70% of total spending. In FY2018, such public assistance comprised 21% of all TANF spending. States spend TANF funds on activities such as child care, education and employment services (not necessarily related to families receiving assistance), services for children "at risk" of foster care, and pre-kindergarten and early childhood education programs. There are few federal rules and little accountability for expenditures other than those made for assistance.

Before the 1996 law, many states experimented with programs to require work or participation in job preparation activities for AFDC recipients. PRWORA established "work participation requirements." Most of these requirements relate to a performance system that applies to the state as a whole, and are not requirements that apply to individuals. The system requires states to meet a minimum work participation rate (WPR). The complex rules of the WPR can be met through several different routes in addition to engaging unemployed recipients in job preparation activities: caseload reduction, state spending beyond what is required under TANF, and assistance to needy parents who are already working. In FY2018, all but one state met the participation standard. A total of 18 states met their minimum WPR through caseload reduction alone.

Spending on assistance and the number of individuals receiving assistance have both declined substantially since the mid-1990s. The reduction in the assistance caseload was caused more by a decline in the percentage of those who were eligible receiving benefits than a decline in the number of people who met TANF's state-defined definitions of financial need. Assistance under TANF alleviates less poverty than it did under AFDC. While there have been expansions in other low-income assistance programs since PRWORA was enacted, such as the refundable tax credits from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the child tax credit, those programs do not provide ongoing assistance on a monthly basis.

Some of the TANF reauthorization bills introduced in the 115th and 116th Congresses attempt to focus a greater share of TANF dollars on activities related to assistance and work. Additionally, these bills would revise the system by which state programs are assessed on their performance in engaging assistance recipients in work or job preparation activities.

Introduction

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant provides grants to states, the District of Columbia, territories, and tribes to help them finance a wide range of benefits and services that address economic disadvantage among children.1 It is best known as a source to help states finance public assistance benefits provided to needy families with children. However, a state may use its TANF funds "in any manner that is reasonably calculated" to help achieve TANF's statutory goals to assist families so that children may live in their own homes or with relatives; end dependence on government benefits for needy parents through work, job preparation, and marriage; reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and promote the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

TANF was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; P.L. 104-193). That law provided TANF program authority and funding through FY2002. Since that original expiration of funding, TANF has been funded through a series of extensions (one for five years, and others for shorter periods of time). Most current TANF policies date back to the 1996 law.

The major TANF issues facing the 116th Congress stem from questions about whether or not TANF's current policy framework allows states to de-emphasize addressing the original concerns that led to the creation of TANF, which centered on the terms and conditions under which needy families with children could receive public assistance benefits. Most families receiving public assistance in TANF's predecessor programs were headed by single mothers. TANF public assistance (for the remainder of this report, the term "assistance" will be used) takes the form of payments to families to help them meet ongoing basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. The assistance is often paid in cash (a monthly check), but it might also be paid on behalf of families in the form of vouchers or payments to third parties. To be eligible for assistance, a family must have a minor child and be determined as "needy" according to the rules of the state. The amount of the assistance benefit is also determined by the state. In July 2017, the monthly TANF assistance benefit for a family of three ranged from $170 a month in Mississippi to $1,021 per month in New Hampshire.2

To provide context for a discussion of TANF issues in the 116th Congress, this report

- describes the main issues discussed in the debates leading to the enactment of PRWORA in 1996;

- provides an overview of the TANF block grant and its funding;

- discusses current uses of TANF funds;

- describes how states are held accountable for achieving the federal goals of TANF and the "work participation requirements"; and

- discusses the decline in the TANF caseload and the implications for how it affects child poverty.

The report also describes legislation introduced in the 115th and the 116th Congress as it relates to the issues of TANF funding levels and distribution, the uses of funds, and the "work participation" requirements.

|

TANF Bills Discussed in This Report This report provides an overview of the issues raised during recent TANF debates. The bills discussed in it are those introduced in the 115th or 116th Congresses that proposed multi-year reauthorizations of TANF:

|

This report does not address all potential issues related to TANF, particularly those related to issues of family structure (a discussion of responsible fatherhood issues, for example, can be found in CRS Report RL31025, Fatherhood Initiatives: Connecting Fathers to Their Children).

The Debates That Led to the Creation of TANF

The modern form of assistance to needy families with children dates back to the mothers' pensions (sometimes called "widows' pensions") funded by state and local governments beginning in the early 20th century. Federal funding for these programs was first provided in the Social Security Act of 1935, through grants to states in the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program, later renamed the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program. The purpose of these grants was to help states finance assistance to help mothers (mostly single mothers and widows or women married to a disabled father) stay at home and care for their children.

The goal of keeping mothers out of the labor force to rear their children was met by resistance from some states and localities. Politically, any consensus regarding this policy goal eroded over time, 3 as increasing numbers of women—particularly married white women—joined the labor force. Additionally, those receiving assistance were increasingly African American families where the father was alive but absent.4 Benefits and the terms and conditions under which benefits were provided varied considerably by state.5 A series of administrative and court decisions in the 1950s and 1960s made the terms under which AFDC was provided more uniform across the states, though income eligibility thresholds and benefit levels continued to vary considerably among states up to the end of AFDC and the enactment of TANF.

In 1969, the Nixon Administration proposed ending AFDC and replacing it with a negative income tax. While the program would have provided an income guarantee, it also would have gradually phased out benefits as an incentive to work. This proposal passed the House twice but never passed the Senate.6 In 1972, the Senate Finance Committee proposed to guarantee jobs to AFDC recipients who had school-age children.7 This proposal was not adopted in the full Senate. President Carter proposed combining the negative income tax with a public service jobs proposal. This, too, was not enacted.

In 1981, during the Reagan Administration, the focus of debates over assistance to needy families shifted to a greater emphasis on work requirements and devolution of responsibility to the states. In 1982, President Reagan proposed to shift all responsibility for AFDC to the states, while the federal government would assume all responsibility for Medicaid. This was not enacted.

The 1980s also saw an increasing concern that single parents were becoming dependent on assistance. Research showed that while most individuals used AFDC for short periods of time, some received assistance for long periods.8 There was continuing concern that receipt of AFDC—assistance generally limited to single mothers—led to more children being raised in single parent families. The Family Support Act of 1988 established an education and training program and expanded participation requirements for AFDC recipients. Additionally, the federal government and states fielded numerous experiments that tested approaches to moving assistance recipients (mostly single mothers) into work. These experiments indicated that mandatory participation in a program providing employment services could increase employment and earnings and reduce receipt of assistance.9

The cash assistance caseload began to increase in 1988, rising to its historical peak in March of 1994. Amid that caseload increase, then-Presidential candidate Bill Clinton pledged to "end welfare as we know it." The subsequent plan created by the Clinton Administration was not adopted; instead, House Republicans crafted a plan following the 1994 midterm elections that became the basis of the legislation enacted in 1996. PRWORA created TANF and established

- a statutorily set amount of funding to states under the TANF basic block grant through FY2002;

- new rules for assistance recipients, such as a five-year time limit on federally funded benefits; and

- a broad-purpose block grant, giving states flexibility in how funds are used.

TANF Funding Levels and Distribution among the States

The bulk of TANF funding is in the form of a basic block grant. Both the total amount of the basic block grant ($16.5 billion per year) and each state's share of the grant are based on the amount of federal and state expenditures in TANF's predecessor programs (AFDC and related programs) in the early to mid-1990s. States must also expend a minimum amount of their own funds on TANF or TANF-related programs under the maintenance of effort (MOE) requirement. That minimum totals $10.4 billion per year. The MOE is based on state expenditures in the predecessor programs in FY1994.

PRWORA froze funding at both the national and state levels through FY2002. TANF has never been comprehensively reauthorized; rather, it has been extended through a series of short-term extensions and one five-year extension. Thus, a funding freeze that originally was to run through FY2002 has now extended through FY2019. There have been no adjustments for changes—such as inflation, the size of the cash assistance caseload, or changes in the poverty population—to the total funding level or each state's level of funding.

Distribution of Funding Among the States

While there were some federal rules for the AFDC program, states determined their own income eligibility levels and benefit amounts paid under it. There were wide variations among the states in benefit amounts, and some states varied benefit amounts by locality. In January 1997, the maximum AFDC benefit for a family of three was $120 per month in Mississippi (11% of the federal poverty level) and $703 per month in Suffolk County, NY (63% of the federal poverty level).10

The variation in AFDC benefit amounts created wide differences in TANF funding relative to each state's number of children in poverty because PRWORA "locked in" these historical variations in the funding levels among the states. The state disparities in TANF funding, measured as the TANF grant per poor child, have persisted. Figure 1 shows that, generally, Southeastern states have lower grants per child living in poverty than states in the Northeast, on the West Coast, or in the Great Lakes region.

PRWORA included a separate fund, supplemental grants, that addressed the funding disparity among the states. From FY1998 to FY2011, supplemental grants were made to 17 states, all in the South and West, based on either low grant amounts per poor person or high rates of population growth.11 Supplemental grants were funded at $319 million (compared to the $16.5 billion in the basic TANF block grant), and hence had a limited effect on total TANF grant per poor child. Funding for these grants expired at the end of June 2011 and has not been reauthorized by Congress since.

Impact of Inflation on the Value of the Block Grant

Over time, inflation has eroded the value (purchasing power) of the TANF block grant and the MOE spending level. While annual inflation has been relatively low since FY1997 (averaging 2.1% per year), the decline in TANF's purchasing power has compounded to a loss in value of 36% from FY1997 to FY2018. Under the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO's) January 2019 inflation projections, if TANF funding remains at its current (FY2019) level through FY2029, the value of the TANF block grant would degrade even further, falling to half of its value in FY1997.

Figure 2 shows the decline in the value of the TANF grant from FY1997 through FY2018, and as projected under the CBO January 2019 economic forecast.

Contingency Funds for Recessions

PRWORA established a contingency fund (originally $2 billion) that would be available in states with high unemployment or increased food assistance caseloads. Its funding was depleted in the last recession (exhausted in FY2010). Beginning with FY2011, the fund has received appropriations of $608 million per year.

The fund provides extra grants for states that

- have high and rising unemployment (a 6.5% unemployment rate that is also at least 110% of the rate in the prior two years) or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) caseloads that are at least 10% higher than they were in 1994 or 1995; and

- spend more from their own funds than they spent in FY1994.

The law provides that a state may receive up to 20% of its basic block grant in contingency funds; however, the funds are paid on a first-come-first-served basis. If the appropriation is insufficient to pay the full amount of contingency funds, they are prorated to the qualifying states.

Both population growth and the increase in the rate at which SNAP-eligible households receive benefits have resulted in most states continuing to meet the SNAP caseload trigger for contingency funds through FY2019. Thus, most states with sufficient state spending on TANF-related activities could continue to draw from the contingency fund. The fund generally spends all of its total each year, regardless of the health of the economy—and thus, it is not serving its original purpose to provide a source of counter-cyclical funding.

Legislation Related to Funding Levels and Distribution

The bills discussed in this report, with the exception of the RISE Out of Poverty Act (H.R. 7010, 115th Congress), would maintain the overall TANF funding level and its distribution among the states, essentially extending the funding freeze that has prevailed since FY1997. A five-year reauthorization was proposed in the Jobs and Opportunity with Benefits and Services for Success Act, both as reported from the House Ways and Means Committee in the 115th Congress (H.R. 5861) and in its revised version in the 116th Congress (H.R. 1753/S. 802). Both versions of the bill would eliminate the TANF contingency fund and use savings to offset an equal increase in mandatory child care spending. The Promoting Employment and Economic Mobility Act (S. 3700; 115th Congress) would have been a three-year reauthorization.

H.R. 7010 would have indefinitely authorized funding for TANF. It would have provided for both an initial increase in TANF funding and ongoing annual increases. The initial increase for each state would have reflected both inflation and child population growth since 1997; future increases would have increased the block grant annually for those factors. While H.R. 7010 would not have redistributed funds among the states, the increases in funding would have been greater for those states that experienced faster child population growth than for those with slower growth, no growth, or population losses.12 In addition to the higher, capped funding amount of the basic block grant, H.R. 7010 would have provided open-ended (unlimited) matching funds for subsidized employment and to guarantee child care to certain populations. It would also have increased TANF contingency funds.

Table 1 summarizes provisions related to TANF funding levels and the distribution of funds in selected legislation introduced in the 115th and 116th Congresses.

|

Provision |

Current Law |

H.R. 5861 (115th Congress) |

S. 3700 (115th Congress) |

H.R. 7010 |

|

|

Years of TANF funding |

Funding expires at the end of FY2019. |

Five years, through FY2023. |

Five years, through FY2024. |

Three years, through FY2021. |

Indefinitely. |

|

TANF block grant funding increased? |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes, funds are increased for inflation and child population growth since FY1997. For later years, annual funding increases for inflation and/or child population growth. |

|

Addresses historical funding disparities among the states? |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Includes "supplemental grants" in the base amount for future funding increases and larger increases for states with faster child population growth. |

|

Contingency fund |

$608 million per year. |

$0, with funds for child care increased by $608 million per year. |

$0, with funds for child care increased by $608 million per year. |

$608 million per year. |

$2.5 billion for the first year, adjusted for inflation and population growth each subsequent year, |

|

Additional TANF grants to states |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Matching grants (at a 50% rate) for subsidized employment and unlimited matching funds (at the Medicaid matching rate) to guarantee child care for certain populations. |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on current law and bill text.

Use of Funds

Though most of the debates leading to PRWORA in 1996 and the creation of TANF focused on assistance to needy families with children, the law as written created a broad-purpose block grant. Thus, TANF is not a program. It is a funding stream that is used by states for a wide range of benefits and services.

Authority to Spend TANF Funds and Count MOE Dollars

States have broad discretion on how they expend federal TANF grants. States may use TANF funds "in any manner that is reasonably calculated"13 to accomplish the block grant's statutory purposes, which involve TANF increasing the flexibility of states in operating programs designed to

- provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives;

- end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage;

- prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies and establish annual numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies; and

- encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.14

There are no requirements on states to spend TANF funds for any particular benefit or activity. Current law does not have a statutory definition of "core activities" to guide states to prioritize spending among the wide range of benefits and services for which TANF funds may be used. States also determine what is meant by "needy" for activities related to the first two statutory goals of TANF. And states may use federal TANF funds for activities related to reducing out-of-wedlock pregnancies and promoting two-parent families without regard to need.

In addition to expending federal funds on allowable TANF activities, federal law permits states to use a limited amount of these funds for other programs. A maximum of 30% of the TANF block grant may be used for the following transfers or expenditures:

- transfers to the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG);

- transfers to the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) (the maximum transfer to the SSBG is set at 10% of the basic block grant); and

- a state match for reverse commuter grants, providing public transportation from inner cities to the suburbs.

The range of expenditures on activities that states may count toward the maintenance of effort requirement is—like the authority to spend federal funds—quite broad. The expenditures need not be "in TANF" itself, but in any program that provides benefits and services to TANF-eligible families in cash assistance, child care assistance, education and job training, administrative costs, or any other activity designed to meet TANF's statutory goals. States may count expenditures made by local governments toward the MOE requirement. Additionally, there is a general rule of federal grants management that permits states to count as a state expenditure third-party (e.g., nongovernmental) in-kind donations, as long as they meet the requirements of providing benefits or services to TANF-eligible families and meet the requirements for the types of activities that states may count toward the MOE requirement.15

Most federal rules about state accountability apply only to expenditures on assistance and families receiving assistance. TANF has few federal rules for the other expenditure categories. Thus, the federal rules under the CCDBG (e.g., the CCDBG health and safety requirements) apply only to federal TANF dollars transferred to CCDBG. These rules do not apply to TANF funds spent on child care but not transferred to CCDBG. The same principle applies to spending in most other expenditure categories where federal programs exist (e.g., child welfare services and early childhood education, such as Head Start). There is also little in the way of accountability for TANF spending other than assistance spending.

TANF Expenditures

Expenditures on TANF assistance have shrunk as a share of total TANF spending. As shown in Figure 3, total (federal and state) expenditures on assistance totaled $21.9 billion in FY1995 under AFDC.16 This accounted for more than 7 out of 10 dollars spent on AFDC and related programs. However, by FY2018 assistance accounted for 1 out of 5 TANF dollars.17

Figure 4 shows the national total of TANF federal and state dollars by activity in FY2018. Most states shifted spending toward areas such as refundable tax credits and child welfare, pre-kindergarten, and other services. Additionally, for child care and work education and training, the reported expenditures are the total expenditures made from TANF and MOE funds—not necessarily expenditures to support families receiving assistance.

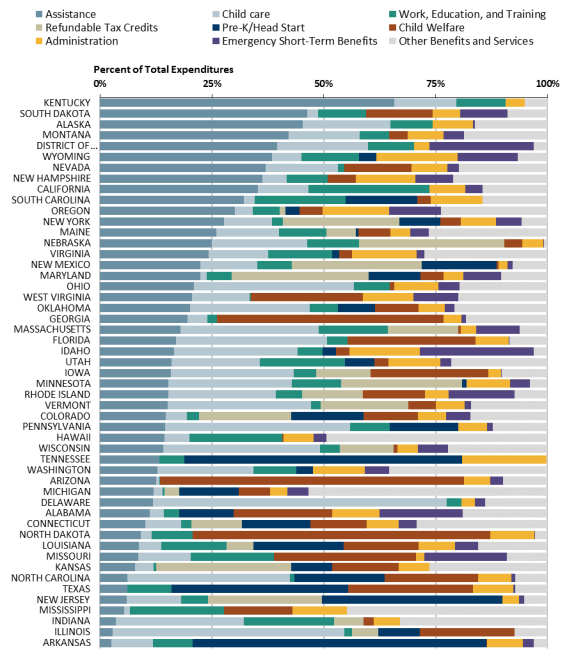

There is also considerable variation among the states in the share of spending devoted to each of these major categories of expenditures. Figure 5 shows expenditures by major category and state for FY2018. States are sorted by the share of their total expenditures devoted to assistance. The figure shows a wide range of expenditure patterns among the states. For example, the share of total expenditures devoted to assistance range from a low of 2.5% (Arkansas) to a high of 65.8% (Kentucky). Child care expenditures vary from zero in two states (Tennessee and Texas) to a high of 65.6% (Delaware).

TANF's flexible funding permits states to use TANF funds in different and innovative ways. For example, states used TANF funds to develop nurse home visiting programs prior to the creation of the primary federal program (Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting).18 States also used the flexibility inherent in TANF to develop subsidized jobs programs and different models of subsidizing jobs, including subsidizing private sector jobs.19

Legislative Proposals on the Use of TANF Funds

The Jobs and Opportunity with Benefits and Services for Success Act, both as reported from the House Ways and Means Committee in the 115th Congress (H.R. 5861) and its revised version in the 116th Congress (H.R. 1753/S. 802), has provisions that would require at least 25% of TANF expenditures from federal funds and expenditures counted as MOE dollars to be spent on "core" activities. The bills would provide a statutory definition of "core" activities that includes assistance, work activities, work supports, case management, and nonrecurrent short-term benefits. They would prohibit direct spending on child care within TANF by requiring that TANF dollars be transferred to the CCDBG in order for states to use federal TANF funds for child care, and they would restrict TANF spending on child welfare services. They would also phase out the ability of states to count the value of donated, in-kind services toward their MOE spending requirement. Additionally, they would limit TANF funds to providing benefits and services only to families with incomes under 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). The version in the 116th Congress would prohibit direct spending on early childhood education with TANF federal dollars.

The RISE Out of Poverty Act (H.R. 7010, 115th Congress) would not have directly limited states' use of basic block grant funds, though it had some provisions related to standards for cash benefit amounts that could affect state spending on assistance versus other benefits and services. H.R. 7010 also had separate matching funds for subsidized employment and guaranteed child care.

S. 3700 (115th Congress) would not have restricted the use of TANF funds. Rather, it would have required additional reporting by states on TANF expenditures. It would have required separate reports on the amount of TANF spending on (1) families that received assistance, and (2) those below 200% of the federal poverty level.

Table 2 summarizes provisions related to the use of TANF funds in legislation proposed in the 115th and 116th Congresses.

|

Provision |

Current Law |

H.R. 5861 |

S. 3700 |

H.R. 7010 (115th Congress) |

|

|

"Core activities" defined? |

No |

Yes: assistance, work activities, work supports, case management, and nonrecurrent short-term benefits. |

Yes: assistance, work activities, work supports, case management, and nonrecurrent short-term benefits. |

No, but requires additional reporting on spending for families receiving assistance and those below 200% of poverty. |

No |

|

States must spend a certain percentage of federal funds on "core activities"? |

No |

Yes: 25% |

Yes: 25% |

No |

No |

|

Financial need-tested for all activities? |

No financial need-test for activities related to reducing out-of-wedlock births or promoting two-parent families. States define need-test for assistance and services to end dependency on government benefits. |

Yes, limits all TANF benefits or services to families below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). |

Yes, limits all TANF benefits or services to families below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). |

No, but requires states to report on expenditures for families by poverty level. |

No |

|

Spending on child care allowed? |

Yes |

Prohibits spending federal TANF funds on child care within TANF, but expands transfer authority to the child care block grant. |

Prohibits spending federal TANF funds on child care and early childhood education within TANF, but expands transfer authority to the child care block grant. |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Spending on child welfare allowed? |

Yes |

Prohibits spending federal TANF funds on child welfare within TANF, but provides transfer authority to the child welfare services program. |

Limits spending federal TANF funds on child welfare within TANF to 10% of the block grant (either within TANF or transferred to the child welfare services program). |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Limitations on transfers to other programs |

Maximum of 30% of TANF funds can be transferred to the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG). Transfers to SSBG limited to 10% of the block grant. |

Maximum of 50% of TANF funds can be transferred to CCDBG, the Child Welfare Services program, and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Program (WIOA). Transfers to Child Welfare Services limited to 10% of the block grant. |

Maximum of 50% of TANF funds can be transferred to CCDBG, the Child Welfare Services program, and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Program (WIOA). Transfers to Child Welfare Services limited to 10% of the block grant. |

Retains current law. |

Retains current law. |

|

Eliminates third-party contribution counted towards MOE? |

No |

Yes, phases out third-party contributions toward the MOE. |

Yes, phases out third-party contributions toward the MOE. |

No |

No |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on current law and bill text.

Work Requirements

A major focus of the debates that led to the enactment of PRWORA was how to move assistance recipients into employment. Under AFDC law, most adult recipients were reported as not working (at least, not working in the formal labor market). In the 1980s and 1990s, both the federal government and the states conducted a series of demonstrations of different employment strategies for AFDC recipients, which concluded that mandatory work participation requirements—in combination with funded employment services—could, on average, increase employment and earnings and reduce assistance expenditures. These demonstrations also found that if such requirements and services were further combined with continued government support to supplement wages, family incomes could, on average, be increased.20 Mandatory participation requirements meant that if an individual did not comply with work requirements, they would be sanctioned through a reduction in their family's benefit.

TANF implemented work requirements through a performance system that applies to the state, rather than implementing requirements on individuals; thus, the mandatory work participation requirements that apply to individual recipients are determined by the states rather than federal law. States have considerable flexibility in how they may implement their requirements.

Performance Measurement: The Minimum Work Participation Rate

The performance standard states must meet, or risk being penalized, is a minimum work participation rate (WPR).21 The minimum WPR is a performance standard for the state; it does not apply directly to individual recipients. The TANF statute requires states to have 50% of their families receiving assistance who have a "work-eligible individual" meet standards of participation in work or activities—that is, a family member must be in specified activities for a minimum number of hours.22 There is a separate participation standard of 90% that applies to the two-parent families. A state that does not meet its minimum WPR is at risk of being penalized through a reduction in its block grant.23

The WPR represents the percentage of families with a work-eligible individual who are either working or participating in job preparation activities. Federal rules list those activities, and also require participation for a minimum number of hours per week (which vary by family type). Federal TANF law limits the extent to which states may count pre-employment activities such as job search and readiness or education and training.

Alternative Ways of Meeting the Minimum WPR

The complex rules of the WPR can be met through several different routes in addition to engaging unemployed recipients in job preparation activities: assistance paid to needy parents who are already working, caseload reduction, and state spending beyond what is required under TANF.

States receive credit toward their minimum WPR for "unsubsidized employment"—employment of a work-eligible individual in a regular, unsubsidized job. In the early years of TANF, states began to increase aid to families that obtained jobs while they received assistance. States changed the rules of their programs to allow families with an adult who went to work while on TANF to continue receiving assistance at higher earnings levels and for longer periods of time after becoming employed. This policy helped states meet their minimum WPR, as unsubsidized employment counts toward meeting that requirement. Additionally, such "earnings supplements" helped raise incomes of working recipients.

In recent years, states have implemented new, separate programs that provide assistance to low-income working parents. For example, Virginia has a program that provides $50 per month for up to one year to former recipients who work and are no longer eligible for regular TANF assistance. Other states, such as California, provide small (e.g., $10 per month) TANF-funded supplements to working parents who receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. Because these programs are TANF-funded and are assistance, they too help states meet the minimum WPR requirements.

The statutory work participation targets (50% for all families, 90% for two-parent families) can be reduced by a "caseload reduction credit." This credit reduces the participation standard one percentage point for each percentage point decline in the number of families receiving assistance since FY2005.24 Additionally, under a regulatory provision, a state may get extra credit for caseload reduction if it spends more than is required under the TANF MOE. Because of the caseload reduction credit, the effective standards states face are often less than the 50% and 90% targets, and they vary by state and by year.

Another practice states have engaged in to help meet their minimum WPR is aiding families in "solely state-funded programs"—those funded with state dollars that do not count toward the TANF MOE. If a family is assisted with state monies not counted toward the TANF MOE, the state is not held accountable for that family by TANF's rules. Many states have moved two-parent families out of TANF and into solely state-funded programs, as these families carry a higher minimum work participation rate. In FY2018, 25 jurisdictions reported no two-parent families in their TANF assistance caseload, though all but two of these jurisdictions did aid two-parent families. Some states have excluded other families from TANF, particularly those less likely to be employed. For example, Illinois assists several categories of families in a non-TANF, solely state-funded program: parents with infants, refugees, pregnant women, unemployed work-eligible individuals not assigned to an activity, and individuals in their first month of TANF receipt.25

Meeting the Minimum WPR in 2018

In FY2018, all states except Montana met their all-family (50%) minimum WPR standard. In that year,

- 18 states met their minimum all-family WPR through caseload reduction alone; and

- 4 additional states plus Puerto Rico met their minimum all-family WPR through a combination of caseload reduction and credit for state spending in excess of what is required under MOE rules.

That is, 23 jurisdictions met their mandatory work participation standard without needing to engage a single recipient in work or job preparation activities. Note that these jurisdictions did report that some recipients in some of their families were working or engaged in job preparation activities, although they did not have to be in order to meet federal requirements.

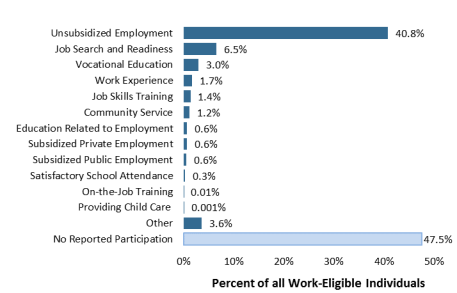

In terms of participation in work or job preparation activities in FY2018, states relied heavily on "unsubsidized employment" (i.e., families that receive TANF assistance while a work-eligible member is employed in a regular, unsubsidized job). As shown in Figure 6, participation in unsubsidized employment was the most common activity, with a monthly average of 40.8% of TANF work-eligible individuals reporting unsubsidized employment during FY2018.

In terms of funded employment services, the highest rate of participation among work-eligible individuals was 6.5% in job search and readiness in FY2018. In that year, 3.0% of work-eligible individuals participated in vocational educational training. Close to half of all work-eligible individuals reported no work or participation in activities during a typical month in FY2018.

Sanctions for Refusing to Comply with Work Requirements

Work requirements mean that participation in work or a job activity is mandatory for certain recipients of assistance. Individuals who do not comply with a work requirement risk having their benefits reduced or ended; thus, such financial sanctions operate as an enforcement mechanism.

TANF requires a state to sanction a family by reducing or ending its benefits for refusing to comply with work requirements; however, under current law TANF does not prescribe the sanction the state must use, and the amount of the sanction is determined by the state. Most states ultimately end benefits to families who do not comply with work requirements, though a lesser sanction is often used for first, and sometimes second, instances of noncompliance.

States can define "good cause" and other exceptions for families refusing to comply, allowing them to avoid sanctions. Additionally, federal law and regulations provide protections against sanctioning certain recipients. States are prohibited from sanctioning single parents with a child under the age of six if the parent cannot obtain affordable child care. States can also provide a waiver of program rules (including work requirements) for victims of domestic violence.

TANF Legislation Addressing Work Participation

Data indicating that nearly half of all work-eligible individuals were not engaged in activities in a typical month and states' reliance on unsubsidized employment has raised concerns that states have not focused on moving unemployed recipients into work. The effectiveness of the minimum WPR standard—the primary federal provision to motivate states to try to engage unemployed recipients—has been questioned. As discussed above, the caseload reduction credit has lowered the minimum WPR required of states, sometimes to zero. States have engaged in various practices to help them meet the minimum WPR. Even with relatively low rates of participation in job preparation activities, most states have met their WPR, raising the question as to whether states are "hitting the target, but missing the point."26

Outcome Measures of Performance

The Jobs and Opportunity with Benefits and Services for Success Act, both as reported from the House Ways and Means Committee in the 115th Congress (H.R. 5861) and its revised version in the 116th Congress (H.R. 1753/S. 802), would replace the minimum WPR with a new performance system based on employment outcomes. H.R. 5861 would have replaced the WPR with employment outcomes based on the measures used in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) programs,27 measuring employment rates and earning levels among those who exit TANF assistance. Each state would have been required to negotiate performance levels with HHS. States that failed to meet those levels would have been at risk of being penalized. The proposal would also have required the development of a model to adjust the outcomes statistically for differences across states in the characteristics of their caseloads and economic conditions.

H.R. 1753/S. 802 introduced in the 116th Congress would also end the minimum WPR, but replace it with a different outcome measure: the number of people who have left TANF assistance and are employed after six months divided by the total TANF caseload. Each state would negotiate a performance level with HHS on this measure, and risk being penalized through a reduction in its block grant if it fell short of that level. States would also be required to collect and report data on the WIOA measures that were contained in the 115th Congress version of the bill, but these would be for informational purposes only.

The other bills discussed in this report would have retained the WPR. However, S. 3700 (115th Congress) would have required the collection of WIOA-like performance measure data and a study by HHS of the impact of moving from the WPR to a performance system based on outcome measures.

Examining outcomes is often intuitively appealing. Outcomes such as job entry or leaving assistance with a job seem to measure more aptly whether TANF is achieving its goal of ending dependence of needy parents on government benefits through work. However, outcome measures can have their own unintended consequences in terms of influencing the design of state programs. The most commonly cited unintended consequence is "cream skimming," improving performance outcomes through serving only those most likely to succeed and leaving behind the hardest-to-serve. The statistical adjustment models contained in these proposals attempt to mitigate the incentive to "cream skim," but such models might not capture all relevant differences in caseload characteristics.

In addition, it can be argued that outcomes do not directly measure the effectiveness of a program. Some families would leave the cash assistance rolls even without the intervention of a program. The effectiveness of a program can also be measured by whether the program made a difference: that is, did it result in more or speedier exits from the program and improve a participant's employment and earnings? That can only be measured by an evaluation of the impact of a program. There is research indicating that long-term impacts of labor force programs are not necessarily related to short-term outcome measures.28

Universal Engagement

Current law requires that each adult (or minor who is not in high school) be assessed in terms of their work readiness and skills. States have the option to develop an Individual Responsibility Plan (IRP) on the basis of that assessment, in consultation with the individual, within 90 days of the recipient becoming eligible for assistance. As of July 2017, 37 states and the District of Columbia had IRP plans for TANF assistance recipients.29 Under current law, the contents of the plan must include an assessment of the skills, prior work experience, and employability of the recipient. The IRP is also required to describe the services and supports that the state will provide so that the individual will be able to obtain and keep employment in the private sector.

In 2002, the George W. Bush Administration proposed, as part of its TANF reauthorization, a "universal engagement" requirement. The legislation written to implement the Administration's reauthorization proposal would have required states to create a written individualized plan for each family. This universal engagement proposal passed the House three times between 2002 and 2005 and was included in bills reported from the Senate Finance Committee during that period, but it was never enacted.

H.R. 5861, the version of the Jobs and Opportunity with Benefits and Services for Success Act in the 115th Congress, revived the notion of requiring a plan for each work-eligible individual. The plan, required within 60 days of an individual becoming eligible for benefits, would have incorporated a requirement that the individual participate in the same activities that currently count toward the WPR for the minimum number of hours that currently apply in the rules for WPR participation. The minimum hours vary by family type (e.g., 20 hours per week for single parents, 30 for other family types). States would have had the ability to determine the sanction for noncompliance.

H.R. 1753/S. 802, the revised version of this bill in the 116th Congress, directs states to require that all work-eligible individuals who have been assessed and have an individualized plan, except single parents caring for infants, engage in the listed activities for a minimum number of hours based on the individuals' family types. Further, it specifies a formula (hours of participation divided by required hours) for sanctioning families with individuals who refuse to comply with work requirements, instead of allowing states to determine the sanction. States with families who fail to meet these requirements would be at risk of being penalized through a reduction in their block grant.

The requirement in H.R. 1753/S. 802 that all work-eligible individuals participate or be subject to sanction may raise a number of issues:

- As discussed, current law and regulations afford protections against sanctioning single parents with children under six who cannot obtain affordable child care, and victims of domestic violence. It is unclear how these protections would interact with a new "universal engagement" proposal.

- The emphasis on an individual participation requirement—rather than a participation rate—may raise questions about whether other groups should be exempted or afforded special treatment. For example, should ill, disabled, aged parent, or caretaker recipients be exempt from requirements? Further, individuals with disabilities must be accommodated in the workplace, and reduced hours is one of the potential accommodations. Thus, if Congress were to consider requiring disabled individuals to work, it might consider special dispensations for them that included a reduced-hour requirement.

- Research suggests that mandatory participation requirements result in fairly large amounts of noncompliance.30 The bill specifies how that noncompliance would be dealt with—a proportional reduction in benefits—but evidence is lacking on the impacts of that specific sanction versus other forms of sanctioning. The pre-1996 research, while finding that sanctioning was important in enforcing mandatory requirements, which led to higher employment and lower assistance, did not produce evidence on whether any specific form of sanctioning was more effective than others.

H.R. 7010 (115th Congress) also included "universal engagement" provisions, but their general intent was to require that each family have a plan rather than to enforce work participation requirements. This bill also would have required states, before sanctioning noncomplying recipients, to notify the family of the noncompliance; provide the noncomplying individual with an opportunity for a face-to-face meeting; and consider whether the noncompliance resulted from mental or physical barriers to employment, limited English proficiency, or failure to receive or access services in the family's plan.

Table 3 summarizes the work participation provisions of the selected TANF legislation in the 115th and 116th Congresses.

|

Provision |

Current Law |

H.R. 5861 |

S. 3700 |

H.R. 7010 (115th Congress) |

|

|

Primary performance measure for the work program |

Work Participation Rate (WPR). |

Employment outcomes, percentage of those who exited assistance employed and their earnings. These outcomes were patterned on those in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). |

Job entry rate—employed leavers divided by the total TANF caseload. Also, WIOA-like outcome measures collected and published for informational purposes. |

WPR, but would require states to collect WIOA-like employment outcomes and HHS to study impact of moving from WPR to a performance system based on outcome measures. |

WPR |

|

Credit toward work performance measure for caseload reduction |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes, but the caseload reduction credit would be limited so that the minimum WPR could not be below 20%. |

No |

|

Limitations on counting educational activities as engagement in work. |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes, but with some additional flexibility to count education for recipients engaged in education and training through performance-based contracts (contracts that pay full amounts only for individuals that secure employment). |

No |

|

Universal engagement (requiring that each adult recipient has a plan). |

No |

Yes, and with individual work requirements incorporated into the plan. |

Yes, and with individual work requirements incorporated into the plan. |

No |

Yes |

|

Sanctions for refusing to engage in work |

Determined by states. |

Determined by states. |

Requires the sanction to be computed by dividing the number of hours engaged in an activity by the total required hours of engagement. |

Determined by states. |

Determined by states, but states prohibited from imposing "full family" and lifetime sanctions. Also requires a pre-sanction review process. |

|

Demonstration projects |

State plan requirements may be waived to operate demonstration projects that further the purposes of TANF. |

No |

No |

Yes, permits up to 10 states to conduct demonstration projects to carry out different engagement strategies. TANF requirements suspended, if needed, to conduct demonstration. |

No |

The TANF Caseload Decline and Child Poverty

The debate that led to the creation of TANF in 1996 focused on assistance to needy families with children—primarily those with one parent, usually a mother without employment in the formal labor market. As discussed earlier in this report, three provisions of law largely shaped the current TANF landscape:

- limited funding for TANF;

- TANF's broad authority for states to use funds on a wide range of activities, which has allowed states to use TANF funds for activities unrelated to assistance and the population receiving assistance; and

- the mandatory work participation rates, which provide states incentives to reduce the cash assistance caseload as well as expand aid to families with earnings.

Caseload Decline: Reduction in Need or Fewer Families in Need Receiving Benefits?

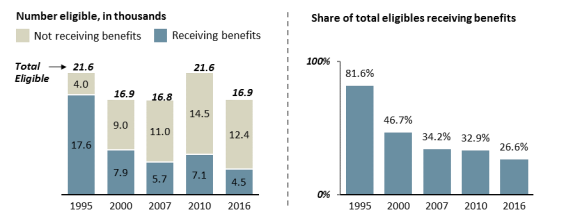

Figure 7 shows estimates that fewer eligible people actually received cash assistance for selected years over the period covered. The selected years include 1995, the year before the enactment of PRWORA; 2000 and 2007, which both represent peaks in the economic cycle; 2010, the year following the end of the most recent recession; and 2016, the most recent year for which data are available. The figure shows that the population eligible for assistance has varied with the economic cycle. However, except for a brief uptick in the caseload during the most recent recession, the number of people receiving assistance has generally declined.

The TANF caseload decline resulted from both a decline in the population eligible for assistance (the population in need) and a decline in the share of the eligible population actually receiving benefits; however, much of it was the result of the decline in the share of the eligible population receiving benefits. In 1995, 81.6% of estimated AFDC-eligible individuals received benefits. In 2016, 26.6% of people estimated to be eligible for TANF cash assistance received benefits.

Child Poverty and Its Alleviation

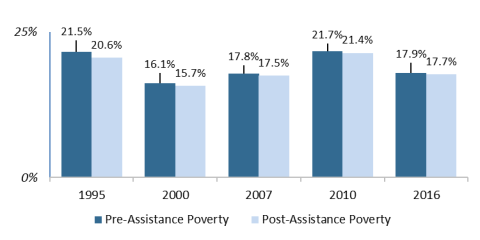

How has the decline in the share of eligible individuals affected the child poverty rate? Figure 8 compares the national child poverty rate using income that does not include assistance and income with assistance (AFDC in 1995, TANF thereafter) included. In the selected years the figure covers, both AFDC and TANF reduced the child poverty rate by less than 1 percentage point. In 1995, AFDC income reduced the observed poverty rate by 0.9 percentage points. In 2016, TANF reduced the observed poverty rate by 0.2 percentage points.

Though AFDC did relatively little to change the child poverty rate, it did reduce the severity of poverty for children. Figure 9 compares the child deep poverty rate (family incomes under 50% of the poverty threshold) using income that does not include assistance and income with assistance (AFDC in 1995, TANF thereafter) included. AFDC income reduced the deep child poverty rate from 11.2% to 6.6% in 1995. In contrast, TANF assistance decreased the child deep poverty rate from 7.7% to 7.1% in 2016.

Another way to examine how the decline in the share of individuals eligible for TANF has diminished the role assistance has played in alleviating child poverty is to examine the pre- and post-assistance aggregate poverty gap. The poverty gap for a poor family is the difference between its poverty threshold and total money income. For example, if a family's poverty threshold is $25,000 and it has money income equal to $20,000, its poverty gap is $5,000. If another family with the same poverty threshold has money income equal to $10,000, its poverty gap is $15,000. The poverty gap for a nonpoor family is, by definition, $0. The aggregate poverty gap is the poverty gap for each poor family summed, and it therefore represents a measure of the depth of poverty (in dollars) for every family in the country combined. If the aggregate gap were somehow filled (i.e., if the family in the first example earned or received an extra $5,000, the family in the second earned or received an extra $15,000, and this same pattern repeated for all families in poverty) poverty would be eliminated.

Table 4 shows the pre- and post-assistance poverty gaps for families with children for selected years from 1995 to 2016 in constant (inflation-adjusted) 2016 dollars. In 1995, AFDC reduced the poverty gap by over $24 billion (more than 27% of the pre-assistance poverty gap of approximately $90 billion). After 1996, the poverty gap varied with the economic cycle. However, the share of the gap that was reduced by TANF assistance declined throughout the period in both dollar and percentage terms. In 2016, TANF cash assistance reduced the poverty gap by approximately $4 billion, or 5.7%.

Table 4. Pre- and Post-assistance Poverty Gaps for Families with Children, Selected Years 1995 to 2016

(Dollar amounts are in billions of constant 2016 dollars)

|

|

Pre-assistance Gap |

Post-assistance Gap |

Difference |

Percentage Reduction in the Poverty Gap |

|

1995 |

$89.734 |

$65.258 |

$24.476 |

27.3% |

|

2000 |

59.454 |

50.523 |

8.931 |

15.0 |

|

2007 |

71.361 |

64.813 |

6.548 |

9.2 |

|

2010 |

86.626 |

79.555 |

7.071 |

8.2 |

|

2016 |

68.335 |

64.448 |

3.887 |

5.7 |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) analysis based on estimates from the TRIM3 microsimulation model.

Note: Constant 2016 dollars were computed using the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Though dollar amounts are affected by inflation adjustment (e.g., they would be different if a different price index was used), the percentage reduction in the poverty gap is not affected by the method of adjusting for inflation.

TANF Legislation Addressing the Caseload Decline and Child Poverty

The drop in the share of TANF-eligible individuals who receive benefits may raise the question of whether a goal of TANF should be caseload reduction per se, regardless of whether or not the size of the population in need is growing. Under TANF, the primary incentive for states to maintain or reduce the number of families receiving assistance is that states are provided a limited amount of TANF funds. States bear the financial risk of the costs of an increase in the number of families receiving assistance. Such an increase would mean a state would have fewer TANF funds to spend on activities other than assistance. The state might have to use more non-TANF dollars if it wanted to make up the shortfall. On the other hand, fewer families receiving assistance frees up funds to use for such activities. All the bills discussed in this report would maintain a limitation on TANF funds distributed to states to finance assistance, though the RISE Out of Poverty Act (H.R. 7010, 115th Congress) would increase those funds for inflation and population growth.31

All the bills discussed in this report would either eliminate or limit the caseload reduction credit against the TANF work participation standards. This would eliminate or limit one incentive for states to reduce their assistance caseload. However, states would still have the incentive to reduce their caseload because of limited funding.

The bills discussed in this report that would require a minimum percentage of TANF spending be on "core" activities do not directly address the question of whether the caseload decline has left a population unserved. They would constrain states in what they spend TANF dollars on, not who benefits from this spending. States would be able to meet the requirement by spending a sufficient amount on work activities, but those dollars could serve disadvantaged parents who do not receive assistance.

H.R. 7010 would have required states to have procedures in place, such as pre-sanction reviews, and prohibit full-family sanctions for failure to meet program requirements. These provisions could have affected the share of the TANF-eligible population that receives assistance.

All of the bills discussed in this report except S. 3700 (115th Congress) would make child poverty reduction a goal of the TANF block grant. H.R. 7010 would have also required states to determine family budgets sufficient to meet needs and required them to ensure that the amount of assistance paid by the state meets those needs. This is not a requirement under current law. Under AFDC, states were required to determine a dollar standard of "need," but were not required to pay assistance in the amount of "need."

Table 5 summarizes provisions related to child poverty reduction and incentives for caseload reduction in selected TANF legislation proposed in the 115th and 116th Congress.

|

Provision |

Current Law |

H.R. 5861 |

S. 3700 |

H.R. 7010 (115th Congress) |

|

|

Capped funding |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, though funding is increased and then adjusted for inflation and population growth. |

|

Credit against work standards for caseload reduction |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes, but limited to a 20 percentage point credit. |

No |

|

Sanction policy |

Determined by states. |

Determined by states. |

Requires pro-rata sanction for refusal to work. |

Determined by states. |

Prohibits full-family sanctions, requires pre-sanction reviews of the individualized plan. |

|

Reduction in child poverty a statutory goal? |

No |

Yes, reducing child poverty by increasing employment entry, retention, and advancement of needy parents added as a goal. |

Yes, reducing child poverty by increasing employment entry, retention, and advancement of needy parents added as a goal. |

No |

Yes, reducing poverty among children added as a goal. |

|

Standards for benefits |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Requires states to determine a dollar amount sufficient to meet basic economic needs and ensure that assistance amounts meet those needs. |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on current law and bill text.

Conclusion

The debates that led to the creation of TANF focused on the terms and conditions under which assistance for needy families with children had been provided. However, Congress created TANF as a broad-purpose block grant that funds a wide range of benefits and services related to childhood economic disadvantage. Since the mid-1990s, states have shifted spending from assistance to those other TANF-funded benefits and services. Spending on assistance fell as the number of families and individuals receiving assistance fell. Much of the decline in the assistance caseload resulted from a drop in the share of eligible people receiving benefits. A substantial number of children and their parents were eligible for TANF assistance but did not receive it; in 2016, an estimated total of 12.4 million individuals were eligible but did not receive TANF assistance, compared to 4.5 million individuals who received benefits at some point in that year. The result was a diminished impact of assistance on alleviating child poverty.

Other means-tested programs have grown in terms of spending and recipients (e.g., the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the child credit, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Medicaid). However, these programs do not provide ongoing cash assistance to families to meet basic needs. SNAP provides food assistance, Medicaid provides medical assistance, and the refundable tax credits—the EITC and the refundable portion of the child credit—provide families with income only once a year at tax refund time.

If policymakers conclude there is an unmet need for ongoing cash assistance to families to meet basic needs, they might consider changes to TANF or consider other alternatives outside of TANF. A common feature of most of the bills discussed in this report is an attempt to focus a greater share of TANF dollars on activities related to assistance and work, and revamp the way state programs are assessed on their performance in engaging assistance recipients in work or job preparation activities. The elimination of the caseload reduction credit would remove one of the incentives to reduce the number of families receiving assistance.

However, there are proposals that would go beyond changes to TANF to address issues related to economic security for families with children. In 2019, a National Academy of Sciences panel on child poverty proposed converting the child tax credit, with a refundable portion that is currently paid once a year through tax refunds, into a monthly, almost universal child allowance. The NAS proposal would provide the child allowance to families both with and without earnings. The NAS stated:

The principal rationale for a child allowance paid on a monthly basis is that it would provide a steady, predictable source of income to counteract the irregularity and unpredictability of market income…. Because the child allowance would be available to both low-income and middle-class families, it would carry little stigma and would not be subject to the varying rules and administrative discretion of a means-tested program, thereby promoting social inclusion.32

Other proposals would seek to guarantee jobs or subsidize jobs. For example, the ELEVATE Act (H.R. 556/S. 136), introduced by Representative Danny Davis and Senator Wyden, would provide matching grants to states (100% federally funded grants during recessions) to subsidize wage paying jobs for individuals.

These proposals echo some of the proposals that were made during past debates. Guaranteed incomes—a child allowance is, in effect, a guaranteed income for families with children—and guaranteed or expanded jobs programs were both proposed in the past. Should Congress again consider such proposals, they may raise issues that have been recurring themes in the debates on policies for low-income individuals, such as whether benefits should be universal or targeted; whether intervention should be in the form of income, services, or employment; whether there should be behavioral conditions (e.g., a requirement to work) attached to aid; and whether policies should be determined nationally or at the state and local levels.33

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report benefitted from the contributions of Kara Billings, Conor Boyle, Patrick Landers, Karen Lynch, and Emilie Stoltzfus of the Domestic Social Policy Division of CRS. Amber Wilhelm produced the figures for the report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For detail on TANF financing and federal rules, see CRS Report RL32748, The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Primer on TANF Financing and Federal Requirements. |

| 2. |

Christine Heffernan, Benjamin Goehring, and Ian Hecker et al., Welfare Rules Databook: State TANF Policies as of July 2017, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, OPRE Report 2018-109, pp. 122-123. |

| 3. |

Steven M. Teles, Whose Welfare? (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1998). |

| 4. |

A report on the characteristics of families receiving assistance in 1942 showed that in the 16 states included in the study, 78.6% of the children were white. See Agnes Leisy, Families Receiving Aid to Dependent Children, October 1942, Federal Security Agency, Social Security Board, March 1945. In 1953, it was reported that 63% of "families" were white. In 1958, 58% of families were white. See Social Security Administration, Bureau of Public Assistance, Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of Families Receiving Aid to Dependent Children, Late 1958, Bureau of Public Assistance Report Number 42, Undated. By 1969, half of the caseload was white. See U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, social and Rehabilitation Service, Preliminary Report of Findings—1969 AFDC Study, MCSS Report AFDC-1 (69), March 1970. |

| 5. |

Winifred Bell, Aid to Dependent Children (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965). |

| 6. |

Vincent J. Burke and Vee Burke, Nixon's Good Deed: Welfare Reform (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974). |

| 7. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Finance Committee, Social Security Amendments of 1972, Report of the Committee on Finance United States Senate to Accompany H.R. 1, 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., 1972, S. Rpt. 92-1230 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1972). |

| 8. |

Mary Jo Bane and David T. Ellwood, Transitions from Welfare to Work, (Cambridge, MA: Urban Systems and Engineering, 1983); David T. Ellwood, Targeting "would-be" long-term recipients of AFDC (Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, 1986); and LaDonna A. Pavetti, The Dynamics of Welfare and Work: Exploring the Process by Which Women Work Their Way Off Welfare (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, May 1993). |

| 9. |

See CRS Report R45317, Research Evidence on the Impact of Work Requirements in Need-Tested Programs. |

| 10. |

The January 1997 and historical AFDC benefit amounts for selected years can be found in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Ways and Means, 1998 Green Book. Background Material and Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means, committee print, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., May 19, 1998, WMCP 105-7. |

| 11. |

The 17 states were Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah. |

| 12. |

The basic block grant for states that experienced population losses would not have declined because of those losses. |

| 13. |

Section 404(a)(1) of the Social Security Act. |

| 14. |

In addition, states may also expend federal TANF grants on any activity financed by pre-TANF programs. These are known as "grandfathered" activities. Examples of activities that do not meet a TANF goal but may be financed by TANF grants include foster care payments and funding for juvenile justice activities, if they were financed in the pre-TANF programs. |

| 15. |

The general rule is at 45 C.F.R. §75.306. This rule is referred to in TANF-specific regulations at 45 C.F.R. §263.2(e). |

| 16. |

Technically, in TANF the term assistance also includes some TANF-funded child care and transportation aid. The TANF financial data do not distinguish between child care and transportation aid that meets the definition of "assistance" versus those type of expenditures that do not meet the definition of assistance. |

| 17. |

The spending amounts in Figure 3 are measured in nominal dollars to focus on the change in the composition of TANF dollars. Nominal dollars do not consider the impact of inflation. The impact of inflation on the TANF block grant is discussed in "Impact of Inflation on the Value of the Block Grant." |

| 18. |

The Pew Center on the States, States and the New Federal Home Visiting Initiative: An Assessment from the Starting Line, 2011. |

| 19. |

Mary Farrell, Sam Elkin, and Joseph Broadus, et al., Subsidizing Employment Opportunities for Low Income Families. A Review of State Employment Programs Created Through the TANF Emergency Fund, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, OPRE Report 2011-38, December 2011. |

| 20. |

For more information on these findings, see CRS Report R45317, Research Evidence on the Impact of Work Requirements in Need-Tested Programs. |

| 21. |

The details of the calculation of the WPR can be found in CRS Report RL32748, The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: A Primer on TANF Financing and Federal Requirements. |

| 22. |

Families without a work-eligible individual are excluded from the participation rate calculation. It excludes families where the parent is a nonrecipient (e.g., disabled and receiving Supplemental Security Income or an ineligible noncitizen) or the children in the family are being cared for by a nonparent relative (e.g., grandparent, aunt, uncle) who does not receive assistance on his or her own behalf. |

| 23. |

States can avoid the penalty if they enter into a corrective compliance plan and achieve their minimum WPR within the time frame of that plan. States can also request not to be penalized if they have "reasonable cause" for not achieving their minimum WPR. |

| 24. |