Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Corporate Formation, Shell Companies, Real Estate, and Financial Transactions

Beneficial ownership refers to the natural person or persons who invest in, control, or otherwise reap gains from an asset, such as a bank account, real estate property, company, or trust. In some cases, an asset’s beneficial owner may not be listed in public records or disclosed to federal authorities as the legal owner. For some years, the United States has been criticized by international bodies for gaps in the U.S. anti-money laundering system related to a lack of systematic beneficial ownership disclosure. While beneficial ownership information is relevant to several types of assets, attention has focused on the beneficial ownership of companies, and in particular, the use of so-called “shell companies” to purchase assets, such as real property, and to store and move money, including through bank accounts and wire transfers. While such companies may be created for a legitimate purpose, there are also concerns that the use of some of these companies can facilitate crimes, such as money laundering. In the United States, corporations and other legal entities such as limited liability companies (LLCs) and partnerships are formed at the state level, not the federal level. Corporation laws vary from state to state, and most or all states do not collect, verify, and update identifying information on beneficial owners.

The U.S. government has long recognized the ability to create legal entities without accurate beneficial ownership information as a key vulnerability of the U.S. financial system. In 2006, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report entitled Company Formations: Minimal Ownership Information Is Collected and Available, which described the challenges of collecting beneficial owner data at the state level. The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s 2015 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment and its 2018 update identify the misuse of legal entities as a key vulnerability in the banking and securities sectors. The 2018 risk assessment additionally clarified that such vulnerability is further compounded by shell companies’ ability to transfer funds to other overseas entities. Such ongoing vulnerabilities have placed the United States under domestic and international pressure, including from the international Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to tighten its anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime with respect to beneficial ownership disclosure requirements. In its 2016 review of the U.S. government’s AML/CFT regime, FATF noted that the “lack of timely access to ... beneficial ownership information remains one of the most fundamental gaps in the U.S. context.” According to FATF, this gap exacerbates U.S. vulnerability to money laundering by preventing law enforcement from efficiently obtaining such information during the course of investigations.

Recent U.S. regulatory efforts and legislation have focused in particular on beneficial ownership disclosure related to the use of shell companies with hidden owners in the banking and real estate sectors. Recent federal regulatory tools include Treasury’s Customer Due Diligence (CDD) rule and use of Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs). Under the CDD Rule, effective since May 2018, certain U.S. financial institutions must establish and maintain procedures to identify and verify the beneficial owners of legal entities that open new accounts. The regulation covers financial institutions that are required to develop AML programs, including, banks, securities brokers and dealers, mutual funds, futures commission merchants, and commodities brokers. Covered financial institutions must collect identifying information on individuals who own 25% or more of legal entities. Since January 2016, Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has issued GTOs to require certain title insurance companies to collect and report identifying information about the beneficial owners of legal entities that conduct certain types of high-end residential real estate purchases. A number of legislative proposals have been introduced related to beneficial ownership disclosure in the 116th Congress. Some of these legislative proposals, such as H.R. 2513 and S. 1889, seek in various ways to impose certain duties on those who form corporations, LLCs, partnerships, or other legal entities to disclose their beneficial owners. These proposals would also mandate that such information be more readily available to authorities (such as federal and state law enforcement and regulatory agencies).

Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Corporate Formation, Shell Companies, Real Estate, and Financial Transactions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview

- Beneficial Ownership and U.S. Corporate Formation

- Beneficial Ownership and U.S. Real Estate

- Overview of Real Estate Transactions

- Money Laundering Risks Through Real Estate and Shell Companies

- U.S. Policy Responses

- History of U.S. Beneficial Ownership Policy and Legislation

- Current Beneficial Ownership Requirements

- Treasury's Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Rule

- Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs)

- Special Measures Applied to Jurisdictions, Financial Institutions, Classes of Transactions, or Types of Accounts of Primary Money Laundering Concern

- Treasury's Sanctions Programs and the 50% Rule Affecting Entities Owned by Sanctioned Persons

- Disclosure of "Substantial" U.S. Ownership for Tax Purposes

- Disclosure of Beneficial Ownership of Office Space Leased by the Federal Government

- Selected Policy Issues

- Sectors Not Covered by Treasury's CDD Rule

- Company Formation Agent Transparency

- Status of the GTO Program

- Establishing AML Requirements for Persons Involved in Real Estate Closings and Settlements

- Disclosure of Beneficial Ownership of U.S.-Registered Aircraft

- Status of International Efforts to Address Beneficial Ownership

- Evolution of the Global Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) Program

- Selected Legislative Proposals in the 116th Congress

- H.R. 2513, Corporate Transparency Act of 2019

- S. 1889, True Incorporation Transparency for Law Enforcement (TITLE) Act

Summary

Beneficial ownership refers to the natural person or persons who invest in, control, or otherwise reap gains from an asset, such as a bank account, real estate property, company, or trust. In some cases, an asset's beneficial owner may not be listed in public records or disclosed to federal authorities as the legal owner. For some years, the United States has been criticized by international bodies for gaps in the U.S. anti-money laundering system related to a lack of systematic beneficial ownership disclosure. While beneficial ownership information is relevant to several types of assets, attention has focused on the beneficial ownership of companies, and in particular, the use of so-called "shell companies" to purchase assets, such as real property, and to store and move money, including through bank accounts and wire transfers. While such companies may be created for a legitimate purpose, there are also concerns that the use of some of these companies can facilitate crimes, such as money laundering. In the United States, corporations and other legal entities such as limited liability companies (LLCs) and partnerships are formed at the state level, not the federal level. Corporation laws vary from state to state, and most or all states do not collect, verify, and update identifying information on beneficial owners.

The U.S. government has long recognized the ability to create legal entities without accurate beneficial ownership information as a key vulnerability of the U.S. financial system. In 2006, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report entitled Company Formations: Minimal Ownership Information Is Collected and Available, which described the challenges of collecting beneficial owner data at the state level. The U.S. Department of the Treasury's 2015 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment and its 2018 update identify the misuse of legal entities as a key vulnerability in the banking and securities sectors. The 2018 risk assessment additionally clarified that such vulnerability is further compounded by shell companies' ability to transfer funds to other overseas entities. Such ongoing vulnerabilities have placed the United States under domestic and international pressure, including from the international Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to tighten its anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime with respect to beneficial ownership disclosure requirements. In its 2016 review of the U.S. government's AML/CFT regime, FATF noted that the "lack of timely access to … beneficial ownership information remains one of the most fundamental gaps in the U.S. context." According to FATF, this gap exacerbates U.S. vulnerability to money laundering by preventing law enforcement from efficiently obtaining such information during the course of investigations.

Recent U.S. regulatory efforts and legislation have focused in particular on beneficial ownership disclosure related to the use of shell companies with hidden owners in the banking and real estate sectors. Recent federal regulatory tools include Treasury's Customer Due Diligence (CDD) rule and use of Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs). Under the CDD Rule, effective since May 2018, certain U.S. financial institutions must establish and maintain procedures to identify and verify the beneficial owners of legal entities that open new accounts. The regulation covers financial institutions that are required to develop AML programs, including, banks, securities brokers and dealers, mutual funds, futures commission merchants, and commodities brokers. Covered financial institutions must collect identifying information on individuals who own 25% or more of legal entities. Since January 2016, Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has issued GTOs to require certain title insurance companies to collect and report identifying information about the beneficial owners of legal entities that conduct certain types of high-end residential real estate purchases. A number of legislative proposals have been introduced related to beneficial ownership disclosure in the 116th Congress. Some of these legislative proposals, such as H.R. 2513 and S. 1889, seek in various ways to impose certain duties on those who form corporations, LLCs, partnerships, or other legal entities to disclose their beneficial owners. These proposals would also mandate that such information be more readily available to authorities (such as federal and state law enforcement and regulatory agencies).

Introduction

Beneficial ownership refers to the natural person or persons who invest in, control, or otherwise reap gains from an asset, such as a bank account, real estate property, company, or trust.1 In some cases, an asset's beneficial owner may not be listed in public records or disclosed to federal authorities as the legal owner. For some years, the United States has been criticized by international bodies for gaps in the U.S. anti-money laundering (AML) system related to a lack of systematic beneficial ownership disclosure.2 While beneficial ownership information is relevant to several types of assets, attention has focused on the beneficial ownership of companies, and in particular, the use of so-called "shell companies" to anonymously purchase assets, such as real property, and to store and move money, including through bank accounts and wire transfers. While such companies may be created for a legitimate purpose, there are also concerns that the use of some of these companies can facilitate crimes, such as money laundering. Recent U.S. regulatory steps and legislation have particularly focused on beneficial ownership disclosure related to the use of shell companies with hidden owners that conduct financial transactions or purchase assets.

In the context of AML regimes, law enforcement authorities as well as financial institutions and their regulators may seek beneficial ownership information to identify or verify the natural persons who benefit from or control financial assets held in the name of legal entities, such as corporations and limited liability companies.3 Drug traffickers, terrorist financiers, tax and sanctions evaders, corrupt government officials, and other criminals have been known to obscure their beneficial ownership of legal entities for money laundering purposes.4 To do so, they may form nominal legal entities, or "shell companies," which have no physical presence and generate little to no economic activity, but are used to anonymously store and transfer illicit proceeds.5 By relying on third-party nominees to serve as the legal owners of record for such shell companies, criminals can control and enjoy the benefits of the assets held by such companies while shielding their identities from investigators.

Although concealing beneficial ownership has long been a central element of many money laundering schemes, many jurisdictions around the world have not established or implemented policy measures that address beneficial ownership disclosure and transparency.6 According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)—an intergovernmental standards-setting body for AML and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT)—financial crime investigations are frequently hampered by the absence of adequate, accurate, and timely information on beneficial ownership.7 FATF has accordingly identified beneficial ownership transparency as an enduring AML/CFT policy challenge.8

Some U.S. government agencies have also long recognized that the ability to create legal entities without accurate beneficial ownership information is a key vulnerability in the U.S. financial system.9 Such ongoing vulnerabilities have placed the United States under domestic and international pressure, including from the FATF, to tighten its AML/CFT regime with respect to beneficial ownership disclosure requirements.

In recent years, various U.S. regulators have taken actions to address this issue, and congressional interest in this topic has increased. This report first provides selected case studies of high-profile situations where beneficial ownership has been obscured. It then provides an overview of beneficial ownership issues relating to corporate formation and in real estate transactions. Next, it describes the recent history of beneficial ownership policy and legislation. The report then discusses recent U.S. regulatory changes to address aspects of beneficial ownership transparency. Thereafter, the report analyzes selected current policy issues, including sectors not covered by existing Treasury regulations, the status of international efforts to address beneficial ownership, and the evolution of the Global Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) program. Finally, the report analyzes selected legislative proposals in the 116th Congress.

|

Selected Case Studies Obscuring beneficial ownership of assets located in the United States has been featured as a key element of several recent high-profile cases allegedly involving terrorist financing, sanctions evasion, proceeds of foreign corruption, and/or other illicit activity. Examples include the following:10 Iran Sanctions, Bank Melli, the Assa Corp., and the Alavi Foundation in New York. In 1995, the U.S. government placed economic sanctions on Iran, including the Iran-controlled Bank Melli. Despite such sanctions, Bank Melli continued to receive rental income from a Manhattan high-rise building. Its ownership stake in the building had been obscured by shell company intermediaries. The building was constructed in the 1970s by an Iranian charitable organization, the Alavi Foundation, with financing from Bank Melli. The bank apparently cancelled its loan on the building in 1989—timed in coordination with a decision to transfer part of the building's ownership stake from Alavi to a shell company known as Assa Corp. This entity was, in turn, wholly owned by Assa Co. Ltd., an entity established in Jersey, United Kingdom, and owned by Iranian citizens who represented the interests of Bank Melli.11 Venezuela's CLAP Program and Official Corruption. On May 3, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued a public advisory that described the financial risks associated with public corruption in Venezuela.12 One of several reported corruption schemes involves the misuse of Venezuela's government-sponsored food distribution program, Los Comités Locales de Abastecimiento y Producción, known in English by its Spanish acronym CLAP. Based on U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) data, FinCEN assessed that corrupt Venezuelan officials and their support networks "profit from the CLAP program through embezzlement and price manipulation schemes involving TBML [trade based money laundering] and front and shell companies." Some of the purported front and shell companies were incorporated in Florida and Delaware. Equatorial Guinea's Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue. On October 10, 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced that it had reached a settlement with Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, eldest son of Equatorial Guinea's current president.13 As part of the agreement, he committed to sell a $30 million Malibu, California, mansion, a Ferrari sports car, and Michael Jackson memorabilia that had been purchased with proceeds of alleged corruption. Despite an official government salary of approximately $60,000 per year, DOJ documents stated that he "used his position and influence as a government minister to amass more than $300 million worth of assets through corruption and money laundering…."14 To move his alleged illicit wealth to the United States for personal use, Nguema Obiang reportedly employed U.S. attorneys to establish shell companies formed under California law and to open U.S. bank accounts for those shell companies.15 He also employed U.S. real estate agents and used U.S. escrow companies to purchase all-cash high-end real estate in California and an aircraft.16 Misappropriation of Funds from 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). According to DOJ, more than $4.5 billion was allegedly diverted out of the Malaysian sovereign wealth fund 1MDB by its officials, their relatives, and other associates.17 1MDB funds were reportedly laundered through a series of complex transactions and shell companies with bank accounts in the United States and abroad. Lack of beneficial ownership of the companies and bank accounts contributed to corrupt funds passing through U.S. financial institutions and being used to acquire and invest in U.S.- and overseas-located assets. |

Overview

Beneficial Ownership and U.S. Corporate Formation

While beneficial ownership information is relevant to a variety of assets, recent policy attention has focused on the beneficial ownership of companies, and in particular, the use of shell companies to anonymously purchase assets, such as real property, and to store and move money, including through bank accounts and wire transfers.

FATF has estimated that over 30 million "legal persons" exist in the United States, and about 2 million new such legal persons are created each year in the states and territories owned by the United States.18 FATF defines legal persons to include entities such as corporations, limited liability companies (LLCs), various forms of partnerships, foundations, and other entities that can own property and are treated as legal persons.19 FATF considers trusts, which share some of the same characteristics, to be "legal arrangements."20 FATF recommends that countries mandate some degree of transparency in identifying beneficial owners, at least for law enforcement and regulatory purposes, for legal persons and legal arrangements.21 There are a range of legitimate reasons for wanting to create such entities, including diversification of risk with joint owners, tax purposes, limiting liability, and other reasons.22 However, such legal persons and arrangements can also be used to hide the identities of owners of assets, thereby facilitating money laundering, corruption, and financial crime. For this reason, FATF recommends countries take steps to ensure that accurate and updated information on the identities of beneficial owners be maintained and accessible to authorities.23

In the United States, corporations, LLCs, and partnerships are formed at the state level, not the federal level. Corporation laws vary from state to state, and the "promoter" of the corporation can choose in which state to incorporate or in which to form another legal entity, often paying a "corporate formation agent" within the state to file the required state-level paperwork.24 Such corporate formation agents may be attorneys, but are not always required to be attorneys. While state laws vary, most states share some basic requirements for forming a corporation or other entity, including the filing of the entity's articles of incorporation with the secretary of state. These articles often include the corporation's name, the business purpose of the corporation, and the corporation's registered agent and address for the purpose of accepting legal service of process if it is sued.25 While state requirements vary, most states do not collect, verify, or update identifying information on beneficial owners. Because no federal standards currently exist, a promoter of a corporation can choose to incorporate in a state with fewer disclosure requirements if they wish.

The FATF evaluation of the United States' AML system found that "measures to prevent or deter the misuse of legal persons and legal arrangements are generally inadequate" in the United States.26 FATF reported there were no mechanisms in place to record or verify beneficial ownership information in the states during corporate formation. They also warned that "the relative ease with which U.S. corporations can be established, their opaqueness and their perceived global credibility makes them attractive to abuse for money laundering and terrorism financing, domestically as well as internationally."27 In a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on June 19, 2019, witness Adam Szubin, former Under Secretary for the Treasury's Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, noted in the question-and-answer portion that the position of the United States as a leader in the financial system at times gave additional credibility to shell companies that had been formed in the United States anonymously by international criminals, enabling them to transact business or open bank accounts outside the United States through these companies with less scrutiny than they might otherwise have received.28

Beneficial Ownership and U.S. Real Estate

Overview of Real Estate Transactions

Some argue that land ownership, even more than ownership of other resources, involves both public and private aspects—such as urban planning, resources and environmental planning, and tax consequences.29 In the United States, however, unlike in many European countries, the federal government has almost no role in the purchase and sale of real estate.30 Real estate transactions in the United States are largely private contracts, and transfers may or may not be recorded publicly, although many buyers find it advantageous to do so.31 Most buyers of property finance their purchases with mortgages from banks. Investors or those who do not require such loans may engage in "all-cash" purchases, which simply means that no loans are involved and that the purchasers must come up with the necessary funds on their own. According to the National Association of REALTORS®, approximately 23% of residential real estate sales transactions were all-cash in 2017.32 Data from real estate data firm CoreLogic for 2016, however, put the figure at 46% for New York state, and similarly higher for some additional states.33

In addition to realtors, who may represent buyers or sellers (but are not required to be involved in transactions), escrow agents and title company agents also play a role in real estate transactions in the United States. Escrow agents essentially act as neutral middlemen in real estate sales, temporarily holding funds for either side. In cases where purchases are made in the name of an LLC, for instance, an escrow agent will look at operating agreements of the LLC to identify the person legally authorized to sign documents, but they generally have no specific duties to locate or identify beneficial owners.34 Usually, escrow agents are not part of title insurance companies or independent title agencies.35

After a buyer and seller agree on a sales price and sign a purchase and sales contract, real estate transactions are transferred to a land title company, most likely the American Land Title Association (ALTA). ALTA represents 6,300 title insurance agents and companies, from small, single-county operators to large national title insurers.36 Title insurance is a form of insurance that protects the holder from financial loss if there are previously undiscovered defects in a title to a property (such as previously undiscovered fraud or forgery, or various other situations). A typical title insurance company, before providing coverage to the buyer of a property, usually investigates prior sales of the property. This process often starts with examining public records tracing the property's history, its owners, sales, and any partial property rights that may have been given away.37 This title search investigation also normally includes tax and court records to give title companies an understanding of what they might be able to insure in their policies issued to buyers.38

Title insurers are the only professionals in the real estate community who currently have money laundering requirements, which were imposed through FinCEN's Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs), as detailed below. As part of this process, when real estate transactions fit the thresholds set in GTOs for certain covered metropolitan areas, title insurance companies work with real estate professionals representing buyers to collect the required beneficial ownership information.

Money Laundering Risks Through Real Estate and Shell Companies

The FATF 2016 evaluation warned that the lack of AML requirements on real estate professionals constituted a significant vulnerability for the United States' AML system.39 As detailed below, FinCEN exempted the real estate sector from AML requirements pursuant to the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-56).

In a 2015 study of the New York luxury property market, the New York Times found that LLCs with anonymous owners were being increasingly utilized in the New York luxury property market. The Times reported that in 2003, for example, one-third of the units sold in one high-end Manhattan building—the Time Warner building—were purchased by shell companies.40 By 2014, however, that figure had risen to over 80%, according to the article. And nationwide, the Times reported, nearly half of residential purchases of over $5 million were made by shell companies rather than named people, according to data from property data provider First American Data Tree studied by the Times.41

According to FinCEN, in 2017, 30% of all high-end purchases in six geographic areas involved a beneficial owner or purchaser representative who was also the subject of a previous suspicious activity report (SAR).42 A 2017 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reviewed available information on the ownership of General Services Administration (GSA) leased space that required higher levels of security as of March 2016, and found that GSA was leasing high-security space from foreign owners in 20 buildings.43 GAO could not obtain the beneficial owners of 36% of those buildings for high-security facilities leased by the federal government, including by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.44

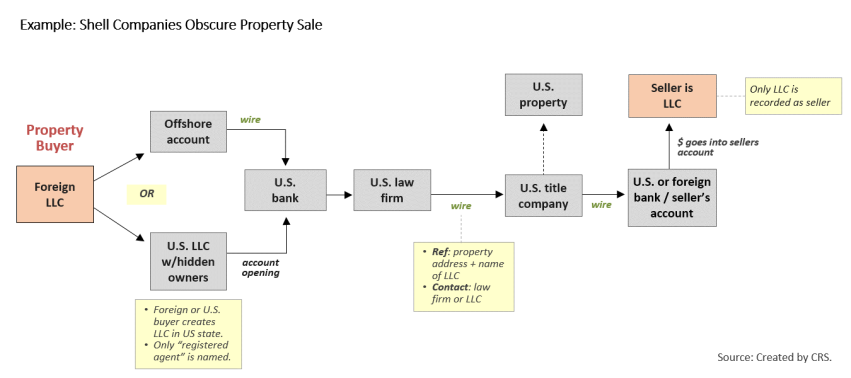

The Appendix provides an example of how an LLC with hidden owners might be used to purchase real estate in the United States with minimal information as to the natural persons behind the purchase or sale of the property.

U.S. Policy Responses

History of U.S. Beneficial Ownership Policy and Legislation

As previously noted, the U.S. government has long recognized the ability to create legal entities without accurate beneficial ownership information as a key vulnerability of the U.S. financial system.45 In 2006, GAO published a report entitled Company Formations: Minimal Ownership Information Is Collected and Available, which described the challenges of collecting beneficial owner data at the state level.46 The U.S. Department of the Treasury's 2015 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment and its 2018 update identify the misuse of legal entities as a key vulnerability in the banking and securities sectors.47 The 2018 risk assessment additionally clarified that such vulnerability is further compounded by shell companies' ability to transfer funds to other overseas entities.48

Such ongoing vulnerabilities have placed the United States under domestic and international pressure, including from FATF, to tighten its AML/CFT regime with respect to beneficial ownership disclosure requirements. In its 2016 review of the U.S. government's AML/CFT regime, FATF noted that the "lack of timely access to … beneficial ownership information remains one of the most fundamental gaps in the U.S. context."49 According to FATF, this gap exacerbates U.S. vulnerability to money laundering by preventing law enforcement from efficiently obtaining such information during the course of investigations. FATF further noted that this gap in the U.S. AML/CFT regime limits U.S. law enforcement's ability to respond to foreign mutual legal assistance requests for beneficial ownership information.50 By contrast, for instance, the European Union (E.U.), in 2015, enacted the E.U. Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which required member states to collect and share beneficial ownership information.51

Since at least the 110th Congress, legislation has been introduced to address long-standing concerns raised by law enforcement, FATF, and other observers over the lack of beneficial ownership disclosure requirements. For example, in the 110th Congress, Senator Carl Levin introduced S. 2956, the Incorporation Transparency and Law Enforcement Assistance Act, on May 1, 2008.52 In his floor statement introducing the bill, Senator Levin noted that the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS) had requested that he delay introduction of a bill in order for the NASS to first convene a task force in 2007 to examine state company formation practices.

In July 2007, the NASS task force issued a proposal. Rather than cure the problem, however, the proposal was full of deficiencies, leading the Treasury Department to state in a letter that the NASS proposal "falls short" and "does not fully address the problem of legal entities masking the identity of criminals." …. That is why we are introducing Federal legislation today. Federal legislation is needed to level the playing field among the States, set minimum standards for obtaining beneficial ownership information, put an end to the practice of States forming millions of legal entities each year without knowing who is behind them, and bring the U.S. into compliance with its international commitments.53

The 115th Congress considered a number of bills concerning beneficial ownership reporting, including S. 1454, the True Incorporation Transparency for Law Enforcement (TITLE) Act and the Corporate Transparency Act of 2017 (H.R. 3089 and S. 1717).

In the 116th Congress, the House Committee on Financial Services on June 11, 2019, passed and ordered to be reported to the House an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 2513, the "Corporate Transparency Act of 2019," introduced by Representative Maloney.54 Also, in the Senate, S. 1889 was introduced on June 19, 2019, by Senator Whitehouse with cosponsors, and a discussion draft bill was circulated June 10, 2019, by Senators Warner and Cotton. This report concludes with an analysis of selected introduced legislative proposals in the 116th Congress.

Current Beneficial Ownership Requirements

Several federal tools are available to address money laundering risks posed by entities that obscure beneficial ownership information, including Treasury's Customer Due Diligence (CDD) rule, use of Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs), and a provision in Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act. Treasury also uses various elements of its economic sanctions programs to address such risks. Finally, with regard to international cooperation, the U.S. government may obtain and share beneficial ownership information with foreign governments in the course of law enforcement investigations (see text box below). In other policy contexts that reach beyond money laundering issues, beneficial ownership has emerged as a concern related to entities' disclosure of U.S. ownership for tax purposes and entities that lease high-security government office spaces. Beneficial ownership issues are also relevant in other areas, such as securities, which are beyond the scope of this report.

Treasury's Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Rule

Pursuant to its regulatory authority under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)55—the principal federal AML statute—FinCEN has long administered regulations requiring various types of financial institutions to establish AML programs.56 The centerpiece of FinCEN's response to concerns about beneficial ownership transparency is its Customer Due Diligence Rule (CDD Rule), which went into effect in May 2018.57 Under the CDD Rule, certain U.S. financial institutions must establish and maintain procedures to identify and verify the beneficial owners of legal entities that open new accounts. The regulation covers financial institutions that are required to develop AML programs, including banks, securities brokers and dealers, mutual funds, futures commission merchants, and commodities brokers.58 Under the rule, covered financial institutions must now collect certain identifying information on individuals who own 25% or more of legal entities that open new accounts.59 The CDD Rule also requires covered financial institutions to develop customer risk profiles and to update customer information on a risk basis for the purposes of ongoing monitoring and suspicious transaction reporting. These requirements make explicit what has been an implicit component of BSA and AML compliance programs.

Geographic Targeting Orders (GTOs)

FinCEN has the authority to impose additional recordkeeping and reporting requirements on domestic financial institutions and nonfinancial businesses in a particular geographic area in order to assist regulators and law enforcement agencies in identifying criminal activity.60 This authority to impose so-called "Geographic Targeting Orders" (GTOs) dates back to 1988.61 GTOs may remain in effect for a maximum of 180 days unless extended by FinCEN. Section 274 of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (P.L. 115-44) replaced statutory language referring to coins and currency with "funds," thereby including a broader range of financial services, such as wire transfers. Several bills in the 116th Congress seek to address the use of GTOs to disclose the beneficial owners of entities involved in the purchase of all-cash real estate transactions (see text box below).

|

FinCEN's Use of GTOs to Combat Money Laundering in High-End Real Estate Since January 2016, FinCEN has issued GTOs to require certain title insurance companies to collect and report identifying information about the beneficial owners of legal entities that conduct certain types of high-end residential real estate purchases. On May 15, 2019, FinCEN reissued GTOs for12 metropolitan areas: Boston; Chicago; Dallas-Fort Worth; Honolulu; Las Vegas; Los Angeles; Miami; New York City; San Antonio; San Diego; San Francisco; and Seattle.62 In these jurisdictions, title insurance companies are required to report to FinCEN the identity of the natural persons behind shell companies used in all-cash purchases (purchases made without a bank loan or other similar form of external financing and made, at least in part, using currency, checks, money orders, funds transfers, or virtual currency) of residential real estate. In all noted jurisdictions, shell company transactions involving purchases of real estate worth $300,000 or more are subject to the current GTO requirements. FinCEN has indicated that "GTOs continue to provide valuable data" and that their reissuance "will further assist in tracking illicit funds and other criminal or illicit activity, as well as inform FinCEN's future regulatory efforts in this sector."63 Specifically, FinCEN has noted that approximately 30% of the transactions covered by GTOs have involved a beneficial owner or purchaser representative who was also the subject of a previous suspicious activity report.64 Similarly, other studies have concluded that all-cash real estate purchases by corporate entities fell by approximately 70% nationwide after the issuance of the GTOs.65 |

Special Measures Applied to Jurisdictions, Financial Institutions, Classes of Transactions, or Types of Accounts of Primary Money Laundering Concern

Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act (P.L. 107-56) added a new provision to the Bank Secrecy Act at 31 U.S.C. §5318A. This provision, popularly referred to as "Section 311," authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to impose regulatory restrictions, known as "special measures," upon finding that a foreign jurisdiction, a financial institution outside the United States, a class of transactions involving a foreign jurisdiction, or a type of account, is "of primary money laundering concern."

The statute outlines five special measures that Treasury may impose to address money laundering concerns. The second special measure authorizes the Secretary to require domestic financial institutions and agencies to take reasonable and practicable steps to collect beneficial ownership information associated with accounts opened or maintained in the United States by a foreign person (other than a foreign entity whose shares are subject to public reporting requirements or are listed and traded on a regulated exchange or trading market), or a representative of such a foreign person, involving a foreign jurisdiction, a financial institution outside the United States, a class of transactions involving a jurisdiction outside the United States, or a type of account "of primary money laundering concern."

Based on a review of Federal Register notices, FinCEN has neither proposed nor imposed the special measure involving the collection of beneficial ownership information.66

Treasury's Sanctions Programs and the 50% Rule Affecting Entities Owned by Sanctioned Persons

Beneficial ownership information is valuable in the context of economic sanctions administered by the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Under economic sanctions programs, assets of designated persons (i.e., individuals or entities) may be blocked (i.e., frozen), thereby prohibiting transfers, transactions, or dealings of any kind, extending to property and interests in property subject to the jurisdiction of the United States as specified in OFAC's specific regulations. As additional persons, including shell and front companies, are discovered to be associated (i.e., owned or controlled by, or acting or purporting to act for or on behalf of, directly or indirectly) with someone already subject to sanctions, OFAC may choose to designate those additional persons to be subject to sanctions.

In addition to persons explicitly identified on OFAC's Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) or Sectoral Sanctions Identification (SSI) lists, sanctions also apply to nonlisted entities that are owned, in part, by blocked persons.67 Current guidance states that sanctions also extend to entities that are at least 50% owned by sanctioned persons.68 Compliance with this so-called "50% Rule" requires financial institutions and others potentially doing business with designated persons or identified sectoral entities to understand an entity's ownership structure, including its beneficial owners.69

Disclosure of "Substantial" U.S. Ownership for Tax Purposes

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA; Subtitle A of Title V of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act; P.L. 111-147, as amended) is a key U.S. policy tool to combat tax evasion. Pursuant to FATCA, U.S. taxpayers are required to disclose to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) financial assets held overseas. In addition, FATCA requires certain foreign financial institutions to disclose information directly to the IRS when its customers are U.S. persons or when U.S. persons hold a "substantial" ownership interest—defined to mean ownership, directly or indirectly, of more than 10% of the stock (by vote or value) of a foreign corporation or of the interests (in terms of profits or capital) of a foreign partnership; or, in the case of a trust, the owner of any portion of it or the holder, directly or indirectly, of more than 10% of its beneficial interest.70 Foreign financial institutions that do not comply with reporting requirements are subject to a 30% withholding tax rate on U.S.-sourced payments.

According to FinCEN, some intergovernmental agreements that the United States negotiated with other governments to facilitate the implementation of FATCA "allow foreign financial institutions to rely on existing AML practices … for the purposes of determining whether certain legal entity customers are controlled by U.S. persons."71 The U.S. government committed in many of these agreements to pursue "equivalent levels of reciprocal automatic information exchange" on the U.S. financial accounts held by taxpayers of that foreign jurisdiction; there is, however, no reciprocity in FATCA.72 Various observers have debated whether legal entity ownership disclosure information provided to the IRS could be used by other federal entities for AML purposes.73

Disclosure of Beneficial Ownership of Office Space Leased by the Federal Government

Section 2876 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (NDAA; 10 U.S.C. 2661 note)74 requires the Defense Department to identify each beneficial owner of a covered entity proposing to lease accommodation in a building or other improvement that is intended to be used for high-security office space for a military department or defense agency.75 Prior to the enactment of Section 2876, in January 2017, the GAO reported that the General Services Administration (GSA) did not keep track of beneficial owners, including foreign owners, of high-security office space it leased for tenants that included the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).76 According to GAO, GSA began in April 2018 to implement a new lease requirement for prospective lease projects that requires offerors to identify and disclose whether the owner of the leased space, including an entity involved in the financing of the property, is a foreign person or a foreign-owned entity.77 In the 116th Congress, H.R. 392, the Secure Government Buildings from Espionage Act of 2019, seeks to expand the scope of the FY2018 NDAA's provisions.

|

International Information-Sharing Mechanisms If requested, the U.S. government may provide international mutual legal assistance to a foreign government seeking beneficial ownership information in the course of a foreign law enforcement investigation and as evidence in a foreign court. Foreign governments may request such assistance through formal means, including through mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs), as well as informal methods. Narrower bilateral executive agreements may also be negotiated with certain foreign governments in order to cover specific areas of law enforcement cooperation. FinCEN, for example, has a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or an exchange of letters in place with dozens of foreign financial intelligence units (FIUs) and some other foreign banking supervision authorities.78 FinCEN also shares and receives financial intelligence information through the Egmont Group, a global association of FIUs.79 Information that may be shared through the Egmont Group includes bank account information; a variety of financial reports on cross-border and currency transactions, suspicious transactions, and cash purchases; as well as criminal information, and records that may be on file with a public registry. FinCEN may also support foreign law enforcement in obtaining information related to major terrorism- or money laundering-related investigations through a process known as a 314(a) request, named after the provision in the USA PATRIOT Act (P.L. 107-56) that originally authorized this program.80 |

Selected Policy Issues

The current policy debate surrounding beneficial ownership disclosure is focused on addressing gaps in the U.S. AML regime and tracking changes made by the international community in its approach to addressing the problem. A key area of congressional activity involves evaluating the risks associated with lack of beneficial ownership information in the corporate formation and real estate sectors. The Treasury's current CDD rule mandates that financial institutions must collect information—for beneficial owners who hold more than 25% of an entity—upon opening an account for the entity. Some legislative proposals would mandate that this type of information be collected when such legal entities are formed, and that the information be reported to FinCEN or another central repository that authorities can access. International developments in beneficial ownership disclosure practices, including trends in the adoption of a program known as the Global Legal Entity Identifier System (LEI), also raise issues for U.S. policy consideration.

Sectors Not Covered by Treasury's CDD Rule

Even following the CDD rule's implementation, some critics argue that gaps remain in U.S. financial transparency requirements The CDD rule, for example, applies only to individuals who own 25% or more of a legal entity. Critics note that the 25% ownership threshold means that if five or more people share ownership, a legal entity may not name or identify any of them (only one management official). Also, the rule applies to new, but not existing, accounts. FATF, for example, has criticized the United States for lacking beneficial ownership requirements for corporate formation agents and real estate transactions. Neither sector is directly affected by the FinCEN rule, but recent legislation has been introduced to address both areas (see section below titled "Selected Legislative Proposals in the 116th Congress"). The following sections discuss potential gaps remaining in U.S. financial transparency requirements after implementation of the CDD rule.

Company Formation Agent Transparency

Third-party service providers known as "company formation agents" often "play a central role in the creation and ongoing maintenance and support of … shell companies."81 While these services are not inherently illegitimate, they can help shield the identities of a company's beneficial owners from law enforcement.82 According to a 2016 FATF report, formation agents handle approximately half of the roughly 2 million new company formations undertaken annually in the United States.83 As discussed, the regulation of company formation agents is primarily a matter of state law. Formation agents are not subject to the BSA or federal AML regulations.84 However, observers have argued that states have not served as effective regulators of the company formation industry.85 These perceived inadequacies with current oversight of the company formation industry have prompted a number of legislative proposals discussed below.

Status of the GTO Program

A number of policymakers have expressed interest in making FinCEN's GTOs targeting money laundering in high-end real estate permanent or otherwise expanding the scope of the current real estate GTO program. Section 702 of the Defending American Security from Kremlin Aggression Act of 2019 (S. 482) would require the Secretary of the Treasury to prescribe regulations mandating that title insurance companies report on the beneficial owners of entities that engage in certain transactions involving residential real estate. Section 214 of the COUNTER Act of 2019 (H.R. 2514), as amended in a mark-up session of the House Financial Services Committee on May 8, 2019, would require the Secretary of the Treasury to apply the real estate GTOs, which currently cover only residential real estate, to commercial real estate transactions.86 Section 129 of the Department of the Treasury Appropriations Act, 2019 (Title I of H.R. 264) would have required FinCEN to submit a report to Congress on GTOs issued since 2016, but it was not enacted.87

Establishing AML Requirements for Persons Involved in Real Estate Closings and Settlements

Section 352 of the USA PATRIOT Act (P.L. 107-56) requires all financial institutions to establish AML programs.88 In 2002, however, FinCEN exempted from Section 352 certain financial institutions, including persons involved in real estate closings and settlements, in order to study the impact of AML requirements on the industry.89 In 2003, FinCEN published an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) to solicit public comments on how to incorporate persons involved in real estate closings and settlements into the U.S. AML regulatory regime.90 Although no final rule has been issued, other developments have occurred. In 2017, FinCEN released a public advisory on the money laundering risks in the real estate sector.91 And in November 2018 a notice in the Federal Register on anticipated regulatory actions contained reference to renewed FinCEN plans to issue an ANPRM to initiate rulemaking that would establish BSA requirements for persons involved in real estate closings and settlements.92

Disclosure of Beneficial Ownership of U.S.-Registered Aircraft

To register an aircraft in the United States with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), applicants must certify their U.S. citizenship. Non-U.S. citizens may register aircraft under a trust agreement in which the aircraft's title is transferred to an American trustee (e.g., a U.S. bank). Investigations into the FAA's Civil Aviation Registry have revealed a lack of beneficial ownership transparency among aircraft registered through noncitizen trusts.93 Reports further indicate that drug traffickers, kleptocrats, and sanctions evaders have been among the operators of aircraft registered with the FAA through noncitizen trusts.94 Some Members of Congress have sought to address beneficial ownership transparency in the FAA's Civil Aviation Registry through legislation. If enacted, H.R. 393, the Aircraft Ownership Transparency Act of 2019, would require the FAA to collect identifying information, including nationality, of the beneficial owners of certain entities, including trusts, applying to register aircraft in the United States.95

Status of International Efforts to Address Beneficial Ownership

U.S. policymakers' interest in addressing beneficial ownership transparency has been elevated by a series of leaks to the media regarding the abuse of shell companies by money launderers, corrupt politicians, and other criminals, as well as sustained multilateral attention to the issue.96 In late 2018, information from such leaks reportedly contributed to a raid by German authorities on Deutsche Bank, one of the world's largest banks.97 Other major banks have become enmeshed in money laundering scandals involving the abuse of accounts associated with shell companies, including Danske Bank, Denmark's largest bank.98

The international community has taken steps to acknowledge and address the issue of a lack of beneficial ownership transparency in the context of anti-money laundering efforts.99 Some countries, including the United Kingdom, have created a public register that provides the beneficial owners of companies—and more countries have committed or are planning to do so. In April 2018, the European Parliament voted to adopt the European Commission's proposed Fifth Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Directive, which among other measures would require European Union member states to maintain public national-level registers of beneficial ownership information for certain types of legal entities.

The European Commission has also sought to identify third-country jurisdictions with "strategic deficiencies" in their national AML/CFT regimes, which pose "significant threats" to the EU's financial system.100 To this end, the Commission has identified eight criteria or "building blocks" for assessing third countries—one of which is the "availability of accurate and timely information of the beneficial ownership of legal persons and arrangements to competent authorities."101 In February 2019, the Commission released a proposed list of third countries with strategic AML/CFT deficiencies that included four U.S. territories: American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.102 A key criticism of the U.S. territories' AML/CFT regime was the lack of beneficial ownership disclosure requirements.

Evolution of the Global Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) Program

The origins of the LEI system lay in some of the problems highlighted in the 2008 financial crisis. These included excessive opacity as to credit risks, and to potential losses accrued across various affiliates of large financial conglomerates. For example, when Lehman Brothers failed in 2008, financial regulators and market participants found it difficult to gauge their financial trading counterparties' exposure to Lehman's large number of subsidiaries and legal entities, domestically and overseas. Partly to better track such exposures, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and G-20 helped to design and create the concept of the LEI system, starting in 2009.103

LEI is a voluntary international program that assigns each separate "legal entity" participating in the program a unique 20-digit identifying number. This number can be used across jurisdictions to identify a legally distinct entity engaged in a financial transaction, including a cross-border financial transaction, making it especially useful in today's globally interconnected financial system.104 The unique identifying number acts as a reference code—much like a bar code, which can be used globally, across different types of markets and for a wide range of financial purposes. These would include, for example, capital markets and derivatives transactions, commercial lending, and customer ownership, due diligence, and financial transparency purposes; as well as risk management purposes for large conglomerates that may have hundreds or thousands of subsidiaries and affiliates to track.105 A large international bank, for example, may have an LEI identifying the parent entity plus an LEI for each of its legal entities that buy or sell stocks, bonds, swaps, or engage in other financial market transactions. The LEI was designed to enable risk managers and regulators to identify parties to financial transactions instantly and precisely.

Although the origins of the LEI stemmed from concerns over credit risk and safety and soundness that surfaced during the 2008 financial crisis, the LEI may also have benefits for financial transparency. A May 2018 study from the Global Legal Entity Foundation found, based on multiple interviews with financial market companies, that the lack of consistent, reliable automated identifiers was creating a great burden on the financial industry; that most in the industry believed the "Know Your Customer" process of onboarding new clients would likely become more automated; and that "there is clearly an opportunity to align on one identifier to generate efficiencies."106 Similar conclusions were reached in a 2017 study by McKinsey & Co.107 The current LEI system is aimed more at tracking financial transactions of various affiliates, but creating a unified global identifier could be considered a natural first step toward more easily tracking ownership of affiliates as well.

Worldwide, more than 700,000 LEIs have been issued to entities in over 180 countries as of November 2017; however, use of the LEI remains largely voluntary as opposed to legally mandatory. In the United States and abroad, some aspects of financial reporting require use of the LEI and these, in substantial part, rely on voluntary implementation.

Some have called the lack of broader adoption of a common legal identifier a collective action problem.108 In a collective action problem, all participants in a system benefit if everyone participates; if only a few participate, those few bear high costs, as early adopters, with little benefit. Collective action problems are classic examples of situations where a government-organized solution may improve outcomes. Similarly, some argue that all parties would benefit if such LEIs were uniformly assigned, but there is no incentive to be a sole or early adopter.109 Academics have urged regulators to mandate the use of the LEI in regulatory reporting as a means of solving this collective action problem.110 Treasury's Office of Financial Research noted, "Universal adoption is necessary to bring efficiencies to reporting entities and useful information to the Financial Stability Oversight Council, its member agencies, and other policymakers."111

Selected Legislative Proposals in the 116th Congress112

In response to some of the issues discussed above, a number of lawmakers have introduced legislation that would require the collection of beneficial ownership information for both newly formed and existing legal entities. The subsections below discuss two of these proposals in the 116th Congress.

H.R. 2513, Corporate Transparency Act of 2019

In June 2019, the House Committee on Financial Services approved legislation that would require many small corporations and LLCs to report their beneficial owners to the federal government.113 Under H.R. 2513, the Corporate Transparency Act of 2019, newly formed corporations and LLCs would be required to report certain identifying information concerning their beneficial owners to FinCEN and annually update that information.114 The bill would also impose these reporting requirements on existing corporations and LLCs two years after FinCEN adopts final regulations to implement the legislation.115 Subject to certain exceptions, the bill defines the term beneficial owner to mean natural persons who "directly or indirectly"

- exercise "substantial control" over a corporation or LLC;

- own 25% or more of the equity of a corporation or LLC; or

- receive "substantial economic benefits" from a corporation or LLC.116

H.R. 2513's reporting requirements are limited to small corporations and LLCs. Specifically, the bill exempts a variety of regulated entities from its reporting requirements, in addition to any company that (1) employs more than 20 full-time employees, (2) files income tax returns reflecting more than $5 million in gross receipts, and (3) has an operating presence at a physical office within the United States.117

The bill would also authorize FinCEN to promulgate a number of rules. First, H.R. 2513 would allow FinCEN to adopt a rule requiring covered corporations and LLCs to report changes in their beneficial ownership sooner than the annual update required by the legislation itself.118 Second, the bill would direct the Treasury Secretary to promulgate a rule clarifying the circumstances in which an individual receives "substantial economic benefits" from a corporation or LLC for purposes of its definition of beneficial owner.119 Third, the legislation would require FinCEN to revise the CDD Rule within one year of the bill's enactment in order to bring the rule "into conformance" with the bill's requirements and reduce any "unnecessary" burdens on financial institutions.120

Finally, H.R. 2513 would impose civil and criminal penalties on persons who knowingly provide FinCEN with false beneficial ownership information or willfully fail to provide complete or updated information.121

S. 1889, True Incorporation Transparency for Law Enforcement (TITLE) Act

In June 2019, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse introduced legislation that would require states receiving funds under the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 to adopt transparent incorporation systems within three years of the bill's enactment.122 Specifically, S. 1889, the True Incorporation Transparency for Law Enforcement (TITLE) Act, would mandate that transparent incorporation systems require newly formed corporations and LLCs to report certain identifying information concerning their beneficial owners to their states of incorporation.123 Under the bill, a compliant formation system would also require corporations and LLCs to report changes in their beneficial ownership within 60 days.124 These requirements would apply to existing corporations and LLCs two years after a state's adoption of a compliant formation system.125 Subject to certain exceptions, S. 1889 defines the term beneficial owner to mean natural persons who "directly or indirectly" (1) exercise "substantial control" over a corporation or LLC, or (2) have a "substantial interest" in or receive "substantial economic benefits" from a corporation or LLC.126

Like H.R. 2513, S. 1889's requirements would be limited to small corporations and LLCs.127 Specifically, S. 1889 would allow states to exempt various regulated entities, in addition to any company that (1) employs more than 20 full-time employees, (2) files income tax returns reflecting more than $5 million in gross receipts, (3) has an operating presence at a physical office within the United States, and (4) has more than 100 shareholders.128 The bill would also impose civil and criminal penalties on persons who knowingly provide states with false beneficial ownership information or willfully fail to provide complete or updated information.129

Finally, S. 1889 would amend the BSA to include "any person engaged in the business of forming corporations or [LLCs]" in its definition of a regulated "financial institution," and would direct FinCEN to issue a proposed rule requiring such persons to establish AML programs.130

Appendix. Hypothetical Example of Shell Companies Obscuring U.S. Property Sale

|

Figure A-1. Shell Companies Obscure U.S. Property Sale: Hypothetical |

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Figure A-1 demonstrates hypothetically how hidden foreign or U.S. buyers might purchase real estate in the United States with minimal disclosure of their identities as hidden beneficial owners. First, foreign or U.S. individuals might establish a foreign-incorporated LLC, subject to that foreign jurisdiction's laws, which could present particular challenges to a U.S. law enforcement agency seeking to investigate the purchase. Alternately, foreign or U.S. individuals could create a U.S. LLC incorporated in a U.S. state with only a "registered agent" required to be disclosed under various states' laws.

A foreign LLC might pay for the property through a wire transfer from a foreign bank account. If the foreign LLC or the U.S. LLC were to open a U.S. bank account to pay for the purchase, then, if this were a new account opened since May 2018, the U.S.-regulated bank would look for beneficial owners owning more than 25% of the LLC, and keep records of that information. Currently, however, that information would not be reported to FinCEN automatically, and law enforcement would most likely require a subpoena to procure that information from the bank's records.

To create additional layers that could obscure the actual buyers of the property, the LLC, whether U.S. or foreign, could route the payment to the title company, which handles the real estate closing, through a law firm. Payments and wire transfers routed through law firms present an extra layer of information a prosecutor or law enforcement agent must go through to try to obtain details of individuals who own the LLC and are purchasing a property. Often the U.S. attorney-client privilege can make it more difficult to exercise this subpoena authority, without at least the possibility that a legal challenge may arise.

Finally, the payment is routed to the title company, which processes the property sale and distributes payment, normally to the seller's account. If the seller obscures his or her identity through an LLC as well, natural persons involved on both sides of the transfer may be hidden.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, 2014, p. 3, at https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf (hereinafter, FATF Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership). |

| 2. |

See FATF, Mutual Evaluation Report of the United States, 2016, at https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-United-States-2016.pdf; and FATF, Mutual Evaluation Report of the United States, 2006, at https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer/MER%20US%20full.pdf. |

| 3. |

See FATF, The FATF Recommendations, updated October 2018, at http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf. See also CRS Report RS21904, The Financial Action Task Force: An Overview. |

| 4. |

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), Guidance on Obtaining and Retaining Beneficial Ownership Information, FIN-2010-G001, March 5, 2010, at https://www.fincen.gov/resources/statutes-regulations/guidance/guidance-obtaining-and-retaining-beneficial-ownership. For FATF's definition of beneficial owner, see FATF, Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, p. 8. |

| 5. |

FinCEN, Potential Money Laundering Risks Related to Shell Companies, FIN-2006-G014, November 9, 2006, at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/guidance/AdvisoryOnShells_FINAL.pdf. |

| 6. |

See also CRS Report R44776, Anti-Money Laundering: An Overview for Congress; CRS In Focus IF11064, Introduction to Financial Services: Anti-Money Laundering Regulation; and CRS Report RL33315, Money Laundering: An Overview of 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and Related Federal Criminal Law. |

| 7. |

FATF, Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, p. 6. |

| 8. |

FATF, Concealment of Beneficial Ownership, 2018, p. 92, at https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/FATF-Egmont-Concealment-beneficial-ownership.pdf. |

| 9. |

U.S. Money Laundering Threat Assessment Working Group, U.S. Money Laundering Threat Assessment, 2005, at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/terrorist-illicit-finance/Documents/mlta.pdf. |

| 10. |

These cases are based on U.S. government public documents and are profiled here because of the alleged involvement of shell companies and the lack of beneficial ownership disclosure. The descriptions are not intended to either validate or dispute the charges or claims. |

| 11. |

See U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), "Acting Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces History Jury Verdict Finding Forfeiture of Midtown Office Building and Other Properties," June 29, 2017, at https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/acting-manhattan-us-attorney-announces-historic-jury-verdict-finding-forfeiture-midtown; U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Treasury Designates Bank Melli Front Company in New York City," December 17, 2008, at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp1330.aspx; and U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Implementation of Executive Order No. 12959 With Respect to Iran," in Federal Register, vol. 60, no. 154, August 10, 1995, pp. 40881-40888. |

| 12. |

FinCEN, Updated Advisory on Widespread Public Corruption in Venezuela, FIN-2019-A002, May 3, 2019, at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/advisory/2019-05-03/Venezuela%20Advisory%20FINAL%20508.pdf. |

| 13. |

DOJ, "Second Vice President of Equatorial Guinea Agrees to Relinquish More Than $30 Million of Assets Purchased with Corruption Proceeds," press release, October 10, 2014, at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/second-vice-president-equatorial-guinea-agrees-relinquish-more-30-million-assets-purchased. |

| 14. |

Ibid. |

| 15. |

U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Keeping Foreign Corruption Out of the United States: Four Case Histories, majority and minority staff report, February 4, 2010, at https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FOREIGNCORRUPTIONREPORTFINAL710.pdf. |

| 16. |

Ibid. |

| 17. |

DOJ, "U.S. Seeks to Recover Approximately $38 Million Allegedly Obtained from Corruption Involving Malaysian Sovereign Wealth Fund," February 22, 2019, at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-seeks-recover-approximately-38-million-allegedly-obtained-corruption-involving-malaysian. |

| 18. |

FATF, Mutual Evaluation of the United States, 2016, p. 153. |

| 19. |

FATF, Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, October 2014, p. 12. |

| 20. |

Ibid, p. 9. |

| 21. |

FATF, "Recommendation 24: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons and Recommendation 25: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Arrangements," The FATF Recommendations, updated October 2018. |

| 22. |

See Theresa A. Gabaldon and Christopher Sagers, Business Organizations, 2019, p. 7, at https://www.wklegaledu.com/Gabaldon-Business2. |

| 23. |

FATF, "Recommendation 24: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons and Recommendation 25: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Arrangements," The FATF Recommendations, updated October 2018. |

| 24. |

The promoter can either be an owner or controller, or the agent of the owner or controller. |

| 25. |

U.S. Legal.com, "Forming A Corporation," at https://corporations.uslegal.com/basics-of-corporations/forming-a-corporation/. |

| 26. |

FATF, Mutual Evaluation of the United States, 2016, p. 153. |

| 27. |

Ibid. |

| 28. |

Adam J. Szubin, Of Counsel, Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, in question and answer, testifying at Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on "Combating Kleptocracy: Beneficial Ownership, Money Laundering, and Other Reforms," June 19, 2019. |

| 29. |

See Ammon Lehavi, "Property and Secrecy," Real Property, Trust, and Estate Law Journal, vol. 50, iss. 3 (Winter 2016), pp. 381-437. |

| 30. |

Written comments of Steve Gottheim, Senior Counsel, American Land Title Association (ALTA), Conference Report: Money Laundering in Real Estate, convened by the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, March 25, 2018, p. 18. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

The National Association of REALTORS®, "All-Cash Sales: 23 Percent of Residential Sales in January 2017," March 2, 2017, at https://www.nar.realtor/blogs/economists-outlook/all-cash-sales-23-percent-of-residential-sales-in-january-2017. |

| 33. |

See National Association of REALTORS®, "Fewer Buyers Are Bringing All-Cash to Close," February 2, 3016, at https://magazine.realtor/daily-news/2016/02/05/fewer-buyers-are-bringing-all-cash-close. |

| 34. |

Written comments of Art Davis, Executive Director, American Escrow Association (AEA), Conference Report: Money Laundering in Real Estate, Convened by the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, March 25, 2018, p. 17. |

| 35. |

Ibid. |

| 36. |

Written comments of Steve Gottheim, Senior Counsel, American Land Title Association (ALTA), Conference Report: Money Laundering in Real Estate, Convened by the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, March 25, 2018, p. 18. |

| 37. |

Ibid. |

| 38. |

Ibid. |

| 39. |

FATF, Mutual Evaluation Report of the United States, 2016, p. 3. |

| 40. |

Louise Story and Stephanie Saul, "Stream of Foreign Wealth Flows to Elite New York Real Estate," New York Times, February 7, 2015. |

| 41. |

Ibid. |

| 42. |

FinCEN, Advisory to Financial Institutions and Real Estate Firms and Professionals, FIN-2017-A003, August 22, 2017, at https://www.fincen.gov/resources/advisories/fincen-advisory-fin-2017-a003. For regulations on suspicious activity reports, see 12 C.F.R. §1010.320. A suspicious activity report (SAR) is a form that certain financial institutions must file with FinCEN in case of suspected money laundering, fraud, or other suspected illicit activity. |

| 43. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Federal Real Property: GSA Should Inform Tenant Agencies When Leasing High-Security Space from Foreign Owners, GAO-17-195, January 2017, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681883.pdf. |

| 44. |

Ibid. |

| 45. |

U.S. Money Laundering Threat Assessment Working Group, U.S. Money Laundering Threat Assessment, pp. 48-49, 2005. |

| 46. |

GAO, Company Formations: Minimal Ownership Information is Collected and Available, GAO-06-376, April 2006, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-06-376. |

| 47. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, 2015, p. 36, at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/terrorist-illicit-finance/Documents/National%20Money%20Laundering%20Risk%20Assessment%20%E2%80%93%2006-12-2015.pdf. |

| 48. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, National Money Laundering Risk Assessment, 2018, pp. 28-45. |

| 49. |

FATF, Mutual Evaluation Report of the United States, 2016, p. 4, at https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-United-States-2016.pdf. |

| 50. |

MLATs are bilateral agreements that effectively allow prosecutors to enlist the investigatory authority of another nation to secure evidence—physical, documentary, and testimonial—for use in criminal proceedings by requesting mutual legal assistance. |

| 51. |

"Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, amending Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Directive 2005/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directive 2006/70/EC (Text with EEA relevance)," EUR-Lex, European Union, at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32015L0849. |

| 52. |

Among other provisions, the bill would have amended the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to mandate that each state that received funding from the Department of Homeland Security must have a state incorporation system. The bill would have required states to maintain information about the beneficial ownership of a corporation or limited liability company (LLC) for five years after the corporation or LLC terminated. It would have also imposed additional identification requirements for foreign beneficial owners of U.S. entities. The bill would have also required the U.S. Department of the Treasury to mandate that state corporate formation agents establish anti-money laundering compliance programs (as do other financial sector professionals). See also S. 569 in the 111th Congress and S. 1483 in the 112th Congress. |

| 53. |

Sen. Carl Levin (for himself and Sens. Coleman and Obama), "Statements on Introduced Bills and Joint Resolutions," Congressional Record, Senate Daily Edition, 110th Congress, 2nd Session, vol. 154, no. 71, May 1, 2008, pp. S3704-S3708. |

| 54. |

See H.R. 2513, 116th Congress (2019), at https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/bills-116pih-corporatetransparency.pdf. |

| 55. |

31 U.S.C. §5311 et seq; P.L. 91-508, as amended. |

| 56. |

FinCEN regulations are found in 31 C.F.R. Chapter X, and are generally organized by institution type. For example, AML standards for banks are found in 31 C.F.R. §1020.210, whereas standards for securities brokers and dealers are found in 31 C.F.R. §1023.210. |

| 57. |

31 C.F.R. §1010.230. |

| 58. |

31 C.F.R §1010.230(f). |

| 59. |

Specifically, covered financial institutions must collect the names, dates of birth, addresses, and Social Security or other government identification numbers from such persons. 31 C.F.R. §10101.230(b), requiring certification of beneficial owner form as included in Appendix A of the regulation. |

| 60. |

31 U.S.C. 5326(a); 31 C.F.R. §1010.370. |

| 61. |

P.L. 100-690, Tit. VI, §6185(c), 102 Stat. 4355. |

| 62. |

FinCEN, Geographic Targeting Order, November 15, 2018, at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/Real%20Estate%20GTO%20Order%20FINAL%20GENERIC%205.15.2019_508.pdf. |

| 63. |

FinCEN, FinCEN Reissues Real Estate Geographic Targeting Orders for 12 Metropolitan Areas, May 15, 2019, at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FAQs%20on%20Real%20Estate%20GTO%205.15.2019_508.pdf. |

| 64. |

FinCEN, Advisory to Financial Institutions and Real Estate Firms and Professionals, FIN-2017-A003, August 22, 2017. For regulations on suspicious activity reports, see 12 C.F.R. §1010.320. |

| 65. |

See Sean Hundtofte and Ville Rantala, Anonymous Capital Flows and U.S. Housing Markets, University of Miami Business School, research paper no. 18-3, May 28, 2018, at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3186634_code1807431.pdf?abstractid=3186634&mirid=1. |

| 66. |

For a full list of §311 actions, see FinCEN, "Special Measures for Jurisdictions, Financial Institutions, or International Transactions of Primary Money Laundering Concern," at https://www.fincen.gov/resources/statutes-and-regulations/311-special-measures. |

| 67. |