Prisoners’ Eligibility for Pell Grants: Issues for Congress

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322), which, among other things, made prisoners ineligible for Pell Grants. However, concerns about the financial and social costs of the growing prison population combined with concerns about the recidivism rate of released prisoners have led some policymakers to reconsider whether prisoners should be allowed to use Pell Grants to help cover the cost of postsecondary coursework. Pell Grants are intended to assist in making the benefits of postsecondary education available to eligible students who demonstrate financial need.

Under Department of Education (ED) regulations, any student who is “serving a criminal sentence in a federal or state penitentiary, prison, jail, reformatory, work farm, or other similar correctional institution” is not eligible to receive a Pell Grant. However, in 2015 ED used its authority under the Higher Education Act (HEA) to create the Second Chance Pell Experiment to determine if access to Pell Grants would increase the enrollment of incarcerated individuals in high-quality postsecondary correctional education programs. Under the experiment, participating institutions of higher education, in partnership with federal and/or state correctional institutions, award Pell Grants to students who are otherwise Pell-eligible except for being incarcerated in a federal or state institution. The experiment is expected to conclude in 2020.

There are several issues policymakers might consider if Congress chooses to take up legislation to reinstate prisoners’ eligibility for Pell Grants, including the following:

The Pell Grant program is a need based program that provides funds to all that qualify. Thus, restoring Pell Grant eligibility to all federal and state prisoners will increase Pell Grant program costs. Should tax dollars be used to educate convicted offenders before they are released from prison?

There are some prisoners who have been sentenced to death, whose sentences exceed their life expectancy, or who might be civilly committed indefinitely under sexually dangerous persons statutes after they have served their prison sentences. Should these prisoners be eligible to receive Pell Grants?

Educational attainment is lower among incarcerated adults than non-incarcerated adults and even prisoners with high school diplomas or general education development (GED) certificates might need additional assistance to help them prepare for the rigors of postsecondary education. Is there a need for additional investment in remedial education or adult basic education for prisoners to help them prepare for postsecondary education classes?

Under current law and regulation, to be eligible for a Pell Grant males who are subject to registration with the Selective Service System (SSS) must register or prove they were either not required by SSS to register or failed to register for an ED-qualifying reason. There is a higher incidence of not registering among men who have been incarcerated during some or all of the period between ages 18 to 25. Should this requirement be retained for incarcerated men, or should the process for proving exceptions be modified to facilitate Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated men?

There is a lack of rigorous evaluations that have isolated the effects postsecondary education has on recidivism, and little research on the best way to deliver postsecondary education in prisons. Should Congress take steps to promote data collection on the availability of, and participation in, postsecondary education to advance research on the effects of postsecondary education on recidivism?

There can be barriers to providing educational programming in a correctional environment (e.g., lack of classroom space and trained instructors, limitations on internet access) regardless of Pell Grant receipt. Are there steps Congress could take to mitigate these barriers?

A criminal history can be a barrier to securing employment in a variety of fields, either because some convicted offenders are prohibited from working in certain jobs due to a provision in law or regulation, or because employers are wary of hiring someone with a criminal history. Is there interest in undertaking any efforts to reduce the collateral consequences of a criminal history on post-release employment to allow the incarcerated student to fully realize the benefits of postsecondary education?

Prisoners' Eligibility for Pell Grants: Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Prison Populations and Postsecondary Education

- Background on Pell Grants for Incarcerated Individuals

- Current Pell Grant Eligibility

- Second Chance Pell Experiment

- Select Issues and Discussion

- Increased Pell Grant Program Costs

- Eligibility Factors

- Pell Grant Eligibility for Prisoners Who Might Not Be Released

- Pell Grant Eligibility of Individuals Who Lack Selective Service Registration

- Pell Grant Eligibility of Individuals Who Have Not Completed Secondary School

- Additional Research on the Effects of Postsecondary Education in Correctional Institutions

- Obstacles to Providing Access to Postsecondary Education in a Correctional Environment

- Unaccommodating Correctional Environments

- Complicated Systems of Responsibility for Correctional Education

- Inadequate Education Program Design

- Increasing Opportunities for Post-Release Employment

Summary

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322), which, among other things, made prisoners ineligible for Pell Grants. However, concerns about the financial and social costs of the growing prison population combined with concerns about the recidivism rate of released prisoners have led some policymakers to reconsider whether prisoners should be allowed to use Pell Grants to help cover the cost of postsecondary coursework. Pell Grants are intended to assist in making the benefits of postsecondary education available to eligible students who demonstrate financial need.

Under Department of Education (ED) regulations, any student who is "serving a criminal sentence in a federal or state penitentiary, prison, jail, reformatory, work farm, or other similar correctional institution" is not eligible to receive a Pell Grant. However, in 2015 ED used its authority under the Higher Education Act (HEA) to create the Second Chance Pell Experiment to determine if access to Pell Grants would increase the enrollment of incarcerated individuals in high-quality postsecondary correctional education programs. Under the experiment, participating institutions of higher education, in partnership with federal and/or state correctional institutions, award Pell Grants to students who are otherwise Pell-eligible except for being incarcerated in a federal or state institution. The experiment is expected to conclude in 2020.

There are several issues policymakers might consider if Congress chooses to take up legislation to reinstate prisoners' eligibility for Pell Grants, including the following:

- The Pell Grant program is a need based program that provides funds to all that qualify. Thus, restoring Pell Grant eligibility to all federal and state prisoners will increase Pell Grant program costs. Should tax dollars be used to educate convicted offenders before they are released from prison?

- There are some prisoners who have been sentenced to death, whose sentences exceed their life expectancy, or who might be civilly committed indefinitely under sexually dangerous persons statutes after they have served their prison sentences. Should these prisoners be eligible to receive Pell Grants?

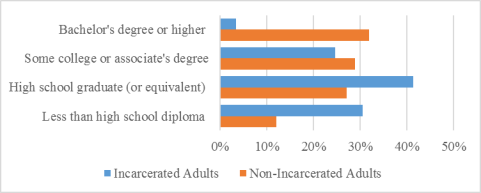

- Educational attainment is lower among incarcerated adults than non-incarcerated adults and even prisoners with high school diplomas or general education development (GED) certificates might need additional assistance to help them prepare for the rigors of postsecondary education. Is there a need for additional investment in remedial education or adult basic education for prisoners to help them prepare for postsecondary education classes?

- Under current law and regulation, to be eligible for a Pell Grant males who are subject to registration with the Selective Service System (SSS) must register or prove they were either not required by SSS to register or failed to register for an ED-qualifying reason. There is a higher incidence of not registering among men who have been incarcerated during some or all of the period between ages 18 to 25. Should this requirement be retained for incarcerated men, or should the process for proving exceptions be modified to facilitate Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated men?

- There is a lack of rigorous evaluations that have isolated the effects postsecondary education has on recidivism, and little research on the best way to deliver postsecondary education in prisons. Should Congress take steps to promote data collection on the availability of, and participation in, postsecondary education to advance research on the effects of postsecondary education on recidivism?

- There can be barriers to providing educational programming in a correctional environment (e.g., lack of classroom space and trained instructors, limitations on internet access) regardless of Pell Grant receipt. Are there steps Congress could take to mitigate these barriers?

- A criminal history can be a barrier to securing employment in a variety of fields, either because some convicted offenders are prohibited from working in certain jobs due to a provision in law or regulation, or because employers are wary of hiring someone with a criminal history. Is there interest in undertaking any efforts to reduce the collateral consequences of a criminal history on post-release employment to allow the incarcerated student to fully realize the benefits of postsecondary education?

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322). The act, among other things, made federal and state prisoners ineligible to receive Pell Grants. The Pell Grant program is the single largest source of federal grant aid supporting postsecondary education students. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 was passed during a period when federal and state policymakers were adopting increasingly punitive measures―such as establishing new crimes, increasing penalties for certain offenses, requiring convicted offenders to serve a greater proportion of their sentences before being eligible for release, and making convicted offenders ineligible for certain government assistance programs―as a means to combat violent crime. However, concerns about the financial and social costs of an increasing prison population and what prisons are doing to rehabilitate prisoners and prevent recidivism have led some policymakers to consider whether some of the "tough on crime" policies of the 1980s and 1990s need to be changed.

|

A Note About the Terminology Used in This Report The terms prisoner and incarcerated person/individual/adult are sometimes used interchangeably in popular lexicon, but they connote different things.1 Prisoner refers to individuals who have been sentenced and are incarcerated in a prison. Generally speaking, prisoners have been convicted of felonies, meaning an offense that carries a sentence of one year and one day or longer. Incarcerated person includes prisoners, but it also includes individuals who are convicted and serve their sentence in jail. Convicted offenders housed in jails are typically convicted of misdemeanors, which, if they carry a term of incarceration, require the offender to serve a jail sentence of one year or less. The current prohibition on receiving Pell Grants extends to both prisoners and incarcerated offenders serving a jail sentence for a misdemeanor (see below). Thus, in this report, the terms prisoner and incarcerated person will be used depending on the context. However, the current debate about expanding access to Pell Grants has largely focused on prisoners. This most likely stems from the fact that there are more prisoners than jail inmates and because prisons are more likely to offer postsecondary education programs because prisoners have more of an opportunity to complete these programs due to their longer sentences. In addition, much of the data and research on postsecondary education in a correctional setting focuses on prisoners and not all incarcerated persons. |

Policymakers have started to reconsider whether prisoners should be prohibited from utilizing Pell Grants to participate in postsecondary education programs while they are incarcerated. Legislation was introduced in the 115th and 116th Congresses that would have allowed incarcerated individuals to receive Pell Grants.2 As Senator Lamar Alexander noted "most prisoners, sooner or later, are released from prison, and no one is helped when they do not have the skills to find a job. Making Pell grants available to them in the right circumstances is a good idea."3 In addition, both the Obama Administration and Trump Administration recommended expanding Pell Grants or other targeted federal financial aid to prisoners who are eligible for release after serving a period of incarceration.4

However, reestablishing prisoners' eligibility for Pell Grants is not without controversy. Legislation was introduced in the 115th Congress that would have ended the Second Chance Pell Experiment, a program begun under the Obama Administration that evaluates the effects of granting prisoners access to Pell Grants.5 Opposition to allowing prisoners to receive Pell Grants stems from the belief that taxpayer money should not be used to finance the education of prisoners, especially if it might compromise assistance to non-prisoners.6 Of note, under current Pell Grant program rules, expanding Pell Grant eligibility to prisoners would not affect the eligibility of non-prisoners or award levels of non-prisoners.

This report provides a discussion of issues policymakers might consider if Congress takes up legislation to allow individuals incarcerated in federal and state facilities to receive Pell Grants. Before discussing these issues, the report offers a brief examination of relevant data on the prison population and the educational participation and attainment of incarcerated adults. This is followed by an overview of the history of the prohibition on allowing incarcerated individuals to receive Pell Grants, and a brief discussion of who is eligible for Pell Grants.

Prison Populations and Postsecondary Education

This section provides information on the number of prisoners in the United States from 1980 to 2018 and an overview of the latest recidivism data from the Department of Justice's Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). It also describes the educational attainment of prisoners, and their participation in and completion of educational programs offered to them.

The recent debate over prisoners' eligibility for Pell Grants is driven, in part, by concerns that the prohibition on prisoners receiving Pell Grants is hampering access to postsecondary education that could aid prisoners' rehabilitation, assist their efforts to find employment after being released, and help them become productive and law-abiding members of their communities. These concerns are combined with an acknowledgment that "tough on crime" policies contributed to a prison population that grew throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s and, because most offenders sentenced to prison will eventually be released, more people returning to their communities after serving a period of incarceration. The growth in the prison population combined with the Pell Grant ban means that an increasing number of prisoners are unable to participate in postsecondary education and large numbers of ex-prisoners are potentially returning to their communities without having enhanced skills or education while in prison that could aid them in becoming law-abiding citizens.

The prison population in the United States increased steadily from 1980 to 2009 before decreasing somewhat from 2010 to 2018 (the most recent year for which prison population data are available).7 There were approximately 1,471,000 prisoners under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities in 2018, compared to 330,000 prisoners in 1980. Increased prison populations are a function of increases in prison admissions, among other things, but growth in the prison population absent large increases in the percentage of convicted offenders who were sentenced to death or life in prison without the possibility of parole means that there has also been an increase in the number of people released from prison annually. Approximately 626,000 prisoners were released by state and federal correctional authorities in 2016, up from approximately 158,000 prisoners released in 1980.

A recent study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) found that 44% of prisoners released from custody in 2005 were rearrested in the first year after their release and 83% of released prisoners had been rearrested after nine years.8 A review of research on corrections-based educational programming suggests that prisoners who participate in postsecondary education while incarcerated recidivate at lower rates than prisoners who do not participate.9 However, methodological limitations in many of the studies mean that alternative explanations for the results―for example, that prisoners who took postsecondary coursework had a greater desire to reform themselves―cannot be excluded.

Employment and educational attainment have also been linked. Data from the Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS) indicate that the employment rate of adults ages 25-64 increases as their level of educational attainment increases. Sixty percent of adults without a high school diploma were in the labor force in 2017 compared to 87% of adults with at least a bachelor's degree. ACS data further indicate that incarcerated individuals have lower levels of educational attainment than the general population. Figure 1 shows that approximately one-third (31%) of incarcerated adults (age 25 or older) have less than a high school diploma, while 12% of non-incarcerated adults have not completed high school.10

While incarcerated individuals have relatively low levels of educational attainment, data suggests that a large percentage of prisoners are not advancing their education while they are incarcerated. Based on a survey of 1,546 inmates in state, federal, and private prisons, the Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reported that more than half (58%) did not further their education during their current period of incarceration.11 The NCES study did not ask prisoners whether the cost of postsecondary education prevented them from participating,12 but the Institute for Higher Education Policy notes that self-financing can be a barrier for prisoners who want to participate in postsecondary education while they are incarcerated.13

Background on Pell Grants for Incarcerated Individuals

Prior to 1992, all incarcerated individuals were eligible to receive aid under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA; P.L. 89-329, as amended), including Pell Grants and loans.14 Pell Grants are need-based aid that is intended to be the foundation for all federal need-based student aid awarded to undergraduates. A 1982 report by the General Accounting Office (now known as the Government Accountability Office; GAO) estimated that approximately 11,000 federal and state prisoners received Pell Grants in academic year (AY) 1979-1980.15 ED's Office of the Inspector General (OIG) estimated that about 25,000 prisoners each year received Pell Grants during the period from 1988 to 1992.16 The 1982 GAO report noted that some states and schools also provided considerable financial assistance to prisoners.

The 1980s and 1990s were marked by several policy initiatives at the state and federal level to augment penalties for convicted offenders. In addition, Congress was concerned about schools established solely to take advantage of the HEA Title IV funds provided to incarcerated students, and the possibility of high student loan default rates among individuals formerly or currently incarcerated.17 Some financial aid administrators questioned whether Pell Grants were the most appropriate source of rehabilitative aid for incarcerated students.18 The Higher Education Amendments of 1992 (P.L. 102-325) limited the eligibility of incarcerated students to HEA Title IV aid in several ways:

- Individuals who were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole and those who were sentenced to death were prohibited from receiving a Pell Grant.

- Pell Grant aid provided to incarcerated students in each fiscal year had to supplement and not supplant the level of postsecondary education assistance provided by the state to incarcerated individuals in FY1988.

- No incarcerated student was eligible to receive a loan (this remains current law).19

- The cost of attendance for incarcerated students was limited to tuition and fees, and required books and supplies (this remains current law).20

- An institution of higher education (IHE) became ineligible to participate in the HEA Title IV programs if more than 25% of its enrolled students were incarcerated (this remains current law).21

GAO published a report in 1994 in response to remaining congressional concerns regarding the use of Pell Grants by incarcerated individuals. The report provided data on the number of inmates receiving Pell Grants, described the effect of allowing incarcerated individuals to receive Pell Grants on grants for other needy students, and reviewed the research at that time on the effect of correctional education on recidivism rates.22 Using ED data for AY1993-1994, GAO reported that approximately 23,000 Pell Grant recipients were incarcerated (less than 1% of all recipients), and the average amount of the Pell Grant was the same regardless of whether individuals were incarcerated or not. Of Pell Grant recipients who were incarcerated, 39% were enrolled in public two-year IHEs, 35% were enrolled in private nonprofit four-year IHEs, and 12% were enrolled in public four-year IHEs. The remaining 14% of incarcerated students were enrolled in public, private nonprofit, or private for-profit programs that granted certificates (10%) or private nonprofit or private for-profit two-year IHEs (4%). GAO indicated that because the Pell Grant program operates as an entitlement for students, the number and amount of Pell Grants for incarcerated individuals had no effect on Pell Grant availability for individuals who were not incarcerated. Finally, GAO concluded that the studies on incarcerated students' participation in educational programming and recidivism "have resulted in conflicting findings" because isolating the effect of correctional education on recidivism was not possible in existing studies for two primary reasons: many interrelated factors affecting recidivism are difficult to define and measure, and an experimental design that randomly assigns prisoners to treatment and control groups would be necessary to eliminate the effect of motivated prisoners self-selecting into correctional education programs.23

The culmination of the "tough on crime" approach in setting federal policy was the enactment of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (VCCLEA, P.L. 103-322). The act, among other things, authorized grants to assist states that enacted "truth in sentencing" laws24 with building new prisons, expanded the number of offenses for which the federal death penalty applies, and established a series of new federal crimes. With respect to the HEA, the VCCLEA eliminated the supplement not supplant provision relating to Pell Grant funds made available to incarcerated individuals and the prohibition on Pell Grant receipt by individuals sentenced to life in prison or the death penalty. The VCCLEA also established the current prohibition against any individuals incarcerated in federal and state penal institutions receiving Pell Grants.

As a likely consequence of the newly enacted prohibition on prisoners receiving Pell Grants, combined with previously enacted prohibitions on the receipt of HEA Title IV student loans, the availability of postsecondary education programs to state prisoners and their enrollment in such programs declined. After prisoners were prohibited from receiving Pell Grants, approximately half of the postsecondary correctional education programs closed and those that remained were reduced in size.25 In addition, from 1991 to 2004 the percentage of state prison inmates enrolling in college courses declined from 14% to 7%.26

In 2008, Congress passed and President George W. Bush signed into law the Higher Education Opportunity Act (P.L. 110-315), which prohibited those individuals who upon completion of a period of incarceration for a forcible or nonforcible sexual offense were subject to an involuntary civil commitment from receiving Pell Grants. This prohibition was partially in response to the fact that 54 individuals who were civilly committed sex offenders in Florida had received Pell Grants in 2004.27

Current Pell Grant Eligibility

Under Department of Education (ED) regulations for HEA Title IV, an incarcerated student is defined as any "student who is serving a criminal sentence in a federal, state, or local penitentiary, prison, jail, reformatory, work farm, or other similar correctional institution."28 The definition does not include an individual who is confined in a correctional facility prior to the imposition of any criminal sentence or juvenile disposition, such as an individual confined in a local jail while awaiting trial. Similarly, it does not include students confined or housed in less restrictive settings such as halfway houses or home detention, or who are serving their sentences only on weekends.

To be eligible for a Pell Grant, a student must meet requirements established by Title IV of the HEA. Some requirements apply to all of the HEA Title IV student aid programs, and some are specific to the Pell Grant program.29 Among the requirements generally applicable to the HEA Title IV student aid programs for AY2018-2019 are the following:

- Students must have a high school diploma or a general educational development (GED) certificate; must have completed an eligible homeschool program; or must have shown an "ability to benefit" from postsecondary education and either be enrolled in an eligible career pathway program or have been initially enrolled in an eligible postsecondary program prior to July 1, 2012.30

- Males who are subject to registration with the Selective Service System (SSS) must be registered with the Selective Service.31

- Students must not be in default on any HEA Title IV student loan.

Specific eligibility requirements for the Pell Grant program that may be germane to criminal justice involved individuals include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Students must not be incarcerated in a federal or state penal institution.

- Students must not be subject to an involuntary civil commitment following incarceration for a sexual offense (as determined under the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI's) Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program).32

Therefore, students serving a sentence in a federal or state penal institution, operated by a federal or state government or a contractor, are ineligible for Pell Grants. Other alleged and convicted offenders, however, may be eligible for a Pell Grant. Those incarcerated in a juvenile justice facility or a local or county jail may be eligible. Individuals in a halfway house or home detention, serving a jail sentence only on weekends, or confined prior to the imposition of any criminal sentence or juvenile disposition are eligible for Pell Grants.33

The other HEA Title IV student aid programs also have eligibility rules for incarcerated students (see regulatory definition above). No incarcerated individual is eligible for any of the loan programs. Incarcerated students are eligible for the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) program and the Federal Work-Study (FWS) program.34 Despite statutory eligibility, it is unlikely that incarcerated individuals would receive FSEOG or FWS aid because such funds are limited, the aid is subject to additional eligibility requirements established by each IHE, and offering FWS jobs in a correctional setting would be difficult.35

Second Chance Pell Experiment

In 2015, ED initiated the Second Chance Pell Experiment to determine if access to Pell Grants would increase the enrollment of incarcerated individuals in high-quality postsecondary education programs. The initiative was part of the "Obama Administration's commitment to create a fairer, more effective criminal justice system, reduce recidivism, and combat the impact of mass incarceration on communities."36 HEA Section 487A authorizes the Secretary of Education to waive certain HEA Title IV statutory or regulatory requirements, except for requirements related to award rules, at a limited number of IHEs in order to provide recommendations for proposed regulations and initiatives. The Secretary used this waiver authority to implement the Second Chance Pell Grant Experiment. In promoting the experiment, ED highlighted research finding that making postsecondary education and training opportunities available to incarcerated individuals increases educational attainment, reduces recidivism, and improves post-release employment opportunities and earnings.37

Under the Second Chance Pell Experiment, participating IHEs, in partnership with federal and/or state prisons, award Pell Grants to individuals who are otherwise Pell-eligible except that they are incarcerated in a federal or state prison. Priority is given to students who are likely to be released from prison within five years. Incarcerated students must enroll in educational programs that lead to high-demand occupations from which such individuals are not legally barred. Education programs may not be offered through correspondence, but may be offered online.38 In addition, students must be able to complete such programs either while incarcerated or after being released. Participating IHEs must offer academic and career guidance, as well as transition services. Finally, the Pell Grant aid offered under the experiment must supplement and not supplant such postsecondary education assistance provided by the IHE, the prison, or another source.39

There are 65 IHEs participating in the experiment, enrolling approximately 8,500 inmates in the first year, 11,000 in the second year, and 10,000 in the third year of the experiment.40 More than one-half of the participating IHEs are public two-year colleges.41 Approximately two-thirds of participating IHEs already provided postsecondary correctional education prior to joining the experiment.42 Some IHEs experienced start-up difficulties related to accreditation approvals,43 the availability of adequate facilities and space, recruiting eligible prisoners, and enrolling a sufficient number of prisoners to make the program financially viable.44 Of the programs originally planned, approximately 35% were designed to award a postsecondary certificate, 47% were designed to award an associate's degree, and 18% were designed to award a bachelor's degree.45

ED generally issues reports of experiments that analyze and summarize IHE-reported outcomes and "address how the experiment: reduced administrative burden; avoided creating additional costs to taxpayers; and improved aid delivery services or otherwise benefited students."46 The reports are intended to inform federal legislative decisionmaking. In February 2019, ED announced that the experiment would be extended an additional year but did not provide an estimate of the release of any data or an evaluation of the program.47

In April 2019, GAO reported on the status of the Second Chance Pell Experiment (hereafter referred to as the 2019 GAO report).48 According to the report, in AY2017-2018, 59 schools disbursed $22.3 million in Pell Grants to over 6,000 prisoners under the experiment.49 Schools reported various challenges implementing the experiment including, but not limited to, prisoners not being registered for Selective Service, prisoners being in default on a HEA Title IV student loan, and prisoners and school staff having difficulty proving prisoner income and financial need.

Select Issues and Discussion

Many prisoners are interested in participating in postsecondary education,50 but one of the most significant barriers to prisoners taking college-level classes is their lack of resources.51 Providing access to Pell Grants could help reduce this barrier. However, there are several issues policymakers might consider before expanding access to Pell Grants, including overall program costs, whether the federal government should support more research on the effects of postsecondary education in correctional institutions, obstacles to providing access to postsecondary education in a correctional environment, and barriers returning prisoners might face when trying to find post-release employment related to their education.

Increased Pell Grant Program Costs

Expanding Pell Grant eligibility to some or all federal and state prisoners will increase Pell Grant program costs. The Pell Grant program is funded by a mix of annual discretionary appropriations and permanent mandatory appropriations. Expanding eligibility would increase both discretionary and mandatory costs.

The Pell Grant program is often referred to as a quasi-entitlement because, since AY1990-1991, eligible students receive the Pell Grant award level calculated for them without regard to available appropriations.52 Expanding eligibility without instituting other provisions would not reduce awards for any otherwise eligible individuals and would only expand the pool of eligible individuals.

The increase in program costs that would result from making federal and state prisoners eligible for Pell Grants who are currently ineligible would be limited by several provisions under current law:

- Students must have a high school diploma (or equivalent) or be enrolled in an eligible career pathway program that leads to high school completion and postsecondary credential attainment.53 As discussed above, 31% of incarcerated individuals do not have a high school diploma (or equivalent) and thus would only be eligible for a Pell Grant if enrolled in an eligible career pathway program.

- Students must not have already completed the curriculum requirements of a bachelor's or higher degree.54 As discussed above, 3% of incarcerated individuals have a bachelor's or higher degree.

- The Pell Grant award for incarcerated students may not exceed the cost of tuition and fees and, if required, books and supplies. The average AY2017-2018 Pell Grant was $4,032 for all undergraduates and $3,541 for students participating in the Second Chance Pell Experiment.55

Eligibility Factors

The following sections describe subgroups of individuals that may require additional consideration when extending Pell Grant eligibility.

Pell Grant Eligibility for Prisoners Who Might Not Be Released

If policymakers choose to reinstate prisoners' eligibility for Pell Grants, part of the justification for doing so is that taking college coursework might help prisoners obtain post-release employment and reduce their risk of recidivism. However, this reasoning raises a question about whether prisoners who might never be released should be eligible to receive Pell Grants. The current Second Chance Pell Experiment excludes individuals who are unlikely to be released and gives priority to students who are expected to be released within five years. Prisoners who might never be released include those who have been sentenced to periods of incarceration that would realistically exceed their natural life spans and those convicted of sex offenses who could be civilly committed to a secure psychiatric facility after serving their sentences because they are at high risk of committing a violent sex offense.

A study conducted by the Sentencing Project56 found that in 2016, a total of 161,957 state and federal prisoners were serving life sentences.57 This includes 108,667 prisoners sentenced to life with the possibility of parole (LWP) and 53,290 prisoners sentenced to life without parole (LWOP).58 Prisoners serving life sentences accounted for one out of every nine prisoners in 2016. The Sentencing Project also found that another 44,311 prisoners were serving virtual life sentences, which were defined as sentences where a prisoner would have to serve at least 50 years of incarceration before being eligible for release. Virtual lifers, while still technically eligible for release (i.e., they were not sentenced to LWOP), are prisoners whose sentences are so long they will most likely spend the rest of their lives in prison. Of note, the Sentencing Project's definition of virtual lifers does not include older prisoners who are sentenced to incarceration and might serve less than 50 years, but because of their advanced age are likely to die in prison. The number of prisoners serving life and virtual life sentences accounted for 14% of all inmates in 2016.59

The Sentencing Project's research found that a handful of states accounted for the majority of prisoners with LWP, LWOP, and virtual life sentences. Four states (California, Georgia, New York, and Texas) accounted for 55% of all prisoners serving LWP. Four states (California, Florida, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania) and the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) accounted for 53% of all prisoners serving LWOP. Five states (Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and Texas) accounted for 55% of prisoners with virtual life sentences.

The Sentencing Project also found that from 2003 to 2016 there was a 27% increase in the number of prisoners serving any type of life sentence, though the number of prisoners sentenced to LWOP increased by 59% while the number of prisoners sentenced to LWP increased by 18%.

When debating about possibly expanding eligibility for Pell Grants, policymakers might also consider whether civilly committed sex offenders, who might never be released, should be allowed to participate in the program. Laws regarding the civil commitment of sex offenders (also known as sexually violent predator or sexually dangerous persons statutes) allow for the involuntary civil commitment of certain sex offenders at the conclusion of their prison sentences. As of 2015, 20 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government had laws that allowed for the civil commitment of sexually violent predators and sexually dangerous persons.60 Individuals who are civilly committed are held until courts deem that they no longer meet the criteria for civil commitment.61 These individuals are held in secure treatment facilities. In general, for someone to be civilly committed the individual must have committed a qualifying sex offense, have a qualifying mental condition (e.g., a personality disorder or a paraphilia62), and be identified as high risk to commit another sexual offense as a result of the disorder.63

The Prison Policy Initiative reported that 5,430 offenders were civilly committed in 2016 in 15 states.64 Unlike most prison sentences, there is no set period of time for when someone who is civilly committed will be released. For example, Minnesota has yet to release any civilly committed sex offenders committed to its custody since the mid-1980s, and 40 individuals have died in custody.65

Pell Grant Eligibility of Individuals Who Lack Selective Service Registration

Congress may consider whether to amend the HEA Title IV and Pell Grant eligibility requirement for Selective Service registration because it is an obstacle for some men who have been involved in the criminal justice system. Most men aged 18–25 are required to register with the SSS.66 Men who are required to register and do not do so are ineligible for Pell Grants, unless they did not knowingly and willfully fail to register. Men ages 18-25 who are incarcerated are not required to register with the Selective Service while they are in prison. Some research shows that men who have been involved in the criminal justice system are at a higher risk for failing to register due to misunderstandings and misinformation.67

Under current regulations, a man who did not register may still achieve eligibility through one of several processes. If he was not required to register, he can provide evidence of his exception. If he is age 25 or younger, he can register. If he was unable to register for reasons beyond his control, he can provide evidence of the circumstances that prevented him from registering. If he has already served on active duty in the Armed Forces, he can provide evidence of such. If he did not knowingly and willfully fail to register, he may submit to his school an advisory opinion from the SSS that does not dispute his claim that he did not knowingly and willfully fail to register, and the school must not have evidence to the contrary.68 For incarcerated or previously incarcerated men 26 and older who failed to register, proving Pell Grant eligibility may be cumbersome. Some IHEs in the Second Chance Pell Experiment have advocated waiving the Selective Service registration requirement for incarcerated individuals in order to increase enrollments.69 The waiver could potentially reduce or eliminate the burden of proving eligibility or establishing eligibility for men 26 and older who were incarcerated at any time during the ages of 18 to 25.

Pell Grant Eligibility of Individuals Who Have Not Completed Secondary School

If postsecondary education completion by prisoners is a policy objective, the large proportion of prisoners who have not completed a secondary school education may also need to be addressed. As shown previously in Figure 1, approximately one-third of incarcerated individuals have not completed high school. There are two primary federal approaches for educating adults who have not completed secondary school: supporting elementary and secondary education and supporting postsecondary career pathways.

Many correctional systems spend a significant proportion of available funding on providing Adult Basic Education (ABE) and GED preparation courses.70 Even in cases where prisoners have a high school diploma or GED, they might still need remedial education in order to complete and pass college-level courses.71 Congress might consider whether there is a need for additional funding or a restructuring of programs to support ABE and GED preparation courses in prisons, or to diagnose learning disabilities in prisoners. There are several federal programs that provide some support that can be used for the secondary education of prisoners:

- The Adult Education and Family Literacy Act (AEFLA; P.L. 113-128), which provides grants to states for basic education for out-of-school adults, specifies that each state must subgrant funds to support educational activities for individuals in correctional institutions and for other institutionalized individuals. AEFLA provides formula grants to states that award competitive grants and contracts to local providers. States may award up to 20% of the funds made available to local providers for programs for corrections education and the education of other institutionalized individuals.72

- The Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (P.L. 115-224) supports the development of career and technical education (CTE) programs that impart technical or occupational skills at the secondary and postsecondary levels. The majority of funding is awarded as formula grants to states, which are authorized to spend up to 2% of their allocation to serve individuals in state institutions, such as state correctional institutions, juvenile justice facilities, and educational institutions that serve individuals with disabilities.73

- The Second Chance Act of 2007, as amended (P.L. 110-199), authorized a series of competitive grants to support offender reentry programs operated by state, local, and tribal governments and nonprofit organizations. These programs include the Adult and Juvenile State and Local Offender Demonstration Program, which may support adult education and training, among several allowable uses. Another of these programs is the Grant Program to Evaluate and Improve Educational Methods at Prisons, Jails, and Juvenile Facilities, which authorizes grants to evaluate and improve academic and vocational education in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities.74

Under current provisions in the HEA, schools may establish career pathway programs for students who are not high school graduates but can demonstrate an ability to benefit from postsecondary education. Students enrolled in career pathway programs may be eligible for Pell Grants and other HEA Title IV aid. A career pathway program combines occupational skills training, counseling, workforce preparation, high school completion, postsecondary education, and postsecondary credential attainment. The ability to benefit may be demonstrated by the student passing an examination approved by ED to be eligible for federal student aid, or by successfully completing six credit hours or 225 clock hours of college work applicable to a certificate or degree offered by a postsecondary institution.75 Ability to benefit tests must be proctored by a certified test administrator and given at an assessment center facility.76 Administering ability to benefit tests to incarcerated individuals might be challenging. If incarcerated individuals do not take the ability to benefit test, they would have to successfully complete six credit hours or 225 clock hours of college work to become eligible for HEA Title IV aid. Should Congress want to take additional steps to promote postsecondary educational pursuits of incarcerated individuals, it might consider encouraging the development of career pathway programs in correctional environments such that prisoners who have not completed high school may pursue postsecondary education with the aid of a Pell Grant.

Additional Research on the Effects of Postsecondary Education in Correctional Institutions

As outlined above, there is a lack of regular, comprehensive data on postsecondary education in correctional facilities. The evaluation literature on the effect of postsecondary education on recidivism would benefit from more routinely collected and complete data on postsecondary education that allows for methodologically rigorous studies. This suggests that there might be a role for the federal government to play in collecting and reporting data on postsecondary education in correctional institutions and supporting more rigorous evaluations of postsecondary education for prisoners.

BJS collects data on the prison population through its annual National Prisoner Statistics (NPS) program and its Survey of Prison Inmates (SPI). The First Step Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-391) requires BJS to collect data through the NPS on the number of federal prisoners who have a high school diploma or GED prior to entering prison, the number who obtain a GED while incarcerated, and the number of BOP facilities with remote learning capabilities. The SPI collects data related to prisoner participation in education and job training, but the data are collected sporadically.77 The most recent iteration was conducted in 2016. Prior to that, BJS conducted the SPI in 1974, 1979, 1986, 1991, 1997, and 2004, when it was known as the Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities. Neither the NPS or the SPI collects data on the types of degrees prisoners seek, how many receive a postsecondary certificate or degree, how much time they spend taking courses, how instruction is provided (e.g., onsite, through correspondence courses, online), or how postsecondary education programs are funded. Nonetheless, BJS has decades of experience collecting data on prison inmates from state correctional agencies and BOP. Congress could consider expanding BJS's mandate under 34 U.S.C. Section 10132 to require the collection and reporting of more detailed data on postsecondary education in correctional facilities. However, states participate in the NPS program voluntarily, so if data collection efforts become too burdensome there is the possibility that some state correctional systems will decline to participate. As a way of promoting state participation in data collection efforts, policymakers might also consider whether to make participation a condition of receiving grant funds under a program such as the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program.78

One limitation of both of the NPS program and the SPI is that they only collect data on prisoners while they are incarcerated. Variables that are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of postsecondary correctional education programs―such as rearrest, reconviction, and reincarceration; post-release educational attainment; post-release employment, and the nature of post-release employment; to just name a few―can only be collected after prisoners have been released, and sometimes several years after they have been released. Even though there are existing data sources that could be used to measure recidivism (e.g., criminal history records data maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or in state criminal history repositories), a new federally sponsored longitudinal data collection effort to track whether prisoners attain education credentials post-release or find employment post-release would enable additional research on the relationship between education and post-incarceration success. In addition, policymakers might consider whether to authorize the FBI to share criminal history records with non-governmental research organizations for the purpose of promoting and conducting recidivism research.79

Congress might also consider other ways to promote research on prisoners' postsecondary education and its impact on recidivism and employment. The literature on postsecondary correctional education lacks studies that utilized randomized controlled trials, which are regarded as the gold standard of social science research. While randomized controlled trials could help draw more definitive conclusions about whether participation in postsecondary education reduces recidivism, it might also undermine the aims of the proposed policy change. A randomized controlled trial would require prisoners to be randomly assigned to a treatment group (postsecondary education programming) or a control group (no postsecondary education programming). This means that some prisoners who might have otherwise enrolled in postsecondary education programming would not be allowed to access it while incarcerated. Although, there are ethical considerations when conducting randomized controlled trials on prisoners and they are afforded additional protections as subjects of behavioral science research studies.80 Congress could also promote more rigorous evaluations of postsecondary correctional education by providing funding to the National Institute of Justice―the research, development, and evaluation agency of the Department of Justice―that is specifically dedicated for this purpose.

It has been argued that evaluations of correctional education programs and other prison-based programming should focus on outcomes other than just recidivism and employment.81 Cessation of criminal activity is considered an important marker of rehabilitation. However, the emphasis on evaluating how correctional education programs affect recidivism means that little is known about the process whereby education programs help shape how released prisoners re-integrate into their communities.82 As noted previously, correctional education is believed to help prisoners improve their cognitive skills and abilities, which, in turn, enables them to continue their education and/or training upon release and secure gainful employment. While there is value in improving the quality of evaluations that assess the effect of correctional education on recidivism and employment, there might be value as well in better understanding how the availability of, and participation in, correctional education programs affect changes in motivation, literacy gains, development of concrete skills, disciplinary actions, postsecondary credits earned, and completion of educational programs.83

Policymakers might also consider whether the federal government should support research into ways to improve the delivery of postsecondary correctional education programs. There is a dearth of methodologically rigorous research on the best way to deliver postsecondary education in prison. For example, prior research seldom accounted for differences in the initial educational level of prisoners. Additionally, there is little research on the effectiveness of different modalities of providing postsecondary education (e.g., in-person instruction, correspondence courses, online learning) or whether the amount of time spent engaging in postsecondary education (i.e., the dosage) has an effect on recidivism.

Obstacles to Providing Access to Postsecondary Education in a Correctional Environment

The following sections describe considerations unique to providing and delivering postsecondary education in a correctional environment.

Unaccommodating Correctional Environments

Even if Congress were to provide access to Pell Grants for certain prisoners, factors related to the correctional environment might limit the ability of prisoners to participate in postsecondary education programs. Three recurring resource challenges identified by ED and GAO are space, access to educational equipment or supplies, and trained staff.84 In 2016, 14 states and BOP held more inmates than their maximum capacity.85 Correctional systems and institutions that are over capacity might not be able to provide sufficient classroom space to meet an increase in demand for postsecondary instruction. Prisons in rural areas might also have problems finding instructors who are nearby or are willing to commute to the prison in order to teach college courses. Additionally, even trained educators will require training on effective teaching strategies for correctional students and techniques and procedures for working in restrictive prison environments.86

It is not unusual for prisoners to be moved from one prison facility to another within the same state or within the federal prison system. Common reasons for the transfer of federal prisoners include security reclassification, medical treatment, and program participation. A prisoner who is transferred from one facility to another would be unable to complete a college course he or she is currently enrolled in if it is an in-person-only class not offered at the facility to which the prisoner is transferred. Programs that are accessible, integrated, and transferrable in every prison in a state or across the federal prison system may reduce the need for transferred prisoners to restart their postsecondary education in a new facility. The Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) argued that many of the resource problems that limit access to postsecondary education could be addressed by providing more access to online courses.87 However, many correctional agencies limit the ability of prisoners to access the internet. Congress might consider whether there are steps that could be taken to promote online postsecondary courses for prisoners. For example, Congress could support a program to develop and test security protocols for prisoner internet access that allows them access to specific, but not all, web content.

Complicated Systems of Responsibility for Correctional Education

There are a variety of arrangements through which educational programming is provided to prisoners. In some states, correctional education is the responsibility of the correctional agency; in other states, a separate entity is responsible for providing it, either through a correctional school district or through the state's education department.88 Having separate agencies responsible for confining prisoners and providing prisoner education can add additional layers of bureaucracy and the agencies' missions might, at times, conflict. Beyond this, in many states the warden of each correctional institution is the one who makes the decision about whether postsecondary education courses will be offered at the prison.89 Also, the warden can cancel postsecondary courses if he or she objects to them.

A 2019 GAO report described the importance of schools coordinating with prison staff and state corrections agencies.90 This suggests that for an effective expansion of educational activities to occur, there might be a need for states and BOP to have a uniform or coordinated curriculum across all correctional facilities in their respective systems. Policymakers might consider whether there is a need to promote more consistent policies in how states provide correctional education. For example, Congress could place conditions on federal funds to require state correctional departments to determine what type of postsecondary education courses will be available at each facility.

Inadequate Education Program Design

The educational programs accessed by prisoners may not be designed to increase their academic and post-release success given the unique attributes of the prison population. ED provides a research-based guide for developing education programs to help incarcerated adults transition successfully to their communities.91 For example, incarcerated individuals may benefit from supportive services. Support services may include assistance selecting academic programs, tutoring, assistance with study skills, assistance with financial literacy, academic and employment counseling, or other academic supports to help them succeed in individual courses and their program of study. For example, some individuals may require advice and assistance in choosing courses, educational programs, and careers that will transfer more easily to practical employment in their post-release communities of choice. Practical employment options for former prisoners are those that provide earnings that permit self-sufficiency, are open to individuals with a criminal record, and are available despite any possible residential or transportation constraints.

Some individuals may want to complete their program of study post-release. An incarcerated student who begins a postsecondary degree program through a postsecondary correctional education program may not be able to complete such degree before release and would benefit from the postsecondary correctional education program credits being fully transferrable or articulated to an educational program available to noninstitutionalized students. Strategic partnerships that ensure institutional courses are fully transferrable and articulated to multiple academic programs may increase the program completion rate.

Increasing Opportunities for Post-Release Employment

In addition to issues related to providing greater access to postsecondary education in prisons, policymakers might also consider issues related to prisoners being able to utilize the education and skills they learned during their coursework to secure post-release employment.

Vocational certificates are a form of postsecondary credential that is popular with prisoners. One study found that approximately one in three prisoners (29%) would like to enroll in courses where they could obtain certificates from colleges or trade schools, which is greater than the proportion of prisoners who reported that they would like to enroll in courses that offer an associate's degree (18%), bachelor's degree (14%), master's degree (5%), professional degree (1%), or doctorate degree (2%).92 However, it is important that the vocational training inmates receive while incarcerated is aligned with employment opportunities that are available in the local job markets to which inmates will return. As IHEP notes, "learning vocational skills that are quickly made obsolete by technological advances or that are irrelevant to local employment opportunities is a waste of money by funders and effort by students."93 Policymakers might consider whether there should there be mandated coordination between correctional agencies, state departments of labor, and business organizations to ensure that inmates are using Pell Grants to participate in postsecondary education programs that provide the skills needed to secure meaningful employment when they are released.

A criminal history can be a barrier to securing employment in a variety of fields, either because formerly incarcerated individuals are prohibited from working in the field due to a provision in law or regulation, or because employers are wary of hiring someone with a criminal history. One estimate suggested that in 2010, 12% of noninstitutionalized men had a felony conviction, and in 2014, 34% of unemployed working-age men had a criminal record.94 Increasing access to Pell Grants might be for naught if prisoners cannot get hired because of their criminal histories. Policymakers might consider whether there is a need to undertake efforts to reduce the collateral consequences of a criminal history on post-release employment. For example, Congress could consider expanding the Department of Labor's Federal Bonding Program for employers that hire recently released prisoners.95

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For example, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in its report on the skills, work experience, education, and training of prisoners notes, "the [Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competences] PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults … targeted a nationally representative sample of incarcerated adults (age 16 to 74) detained in state and federal prisons, and in private prisons housing state and federal inmates" [emphasis added]. Even though the sample only includes prisoners, NCES refers to the population as "incarcerated adults." Bobby D. Rampey, Shelley Keiper, and Leyla Mohadjer, et al., Highlights From the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults: Their Skills, Work Experience, Education, and Training: Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies: 2014, U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, NECS 2016-040, Washington, DC, November 2016, pp. 1-2 (hereinafter, "Highlights From the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults"). |

| 2. |

See, for example, H.R. 254 (115th Congress), S. 2423 (115th Congress), S. 1074 (116th Congress), H.R. 2168 (116th Congress), S. 2423 (116th Congress), and H.R. 254 (116th Congress). |

| 3. |

Erica L. Green, "Senate Leaders Reconsider Ban on Pell Grants for Prisoners," New York Times, February 15, 2018. |

| 4. |

U.S. Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2017 Budget, p. O-21; and White House, Proposals to Reform the Higher Education Act, March 18, 2019, p. 5. |

| 5. |

See the Kids Before Cons Act (H.R. 2007, 115th Congress). |

| 6. |

Allie Grasgreen, "Kids Before Cons Act aims to fight Pell Grants for prisoners," Politico, July 31, 2015. |

| 7. |

Jurisdiction refers to the legal authority of a state or federal correctional authority over a prisoners committed to its custody. Prisoners can be under a correctional authority's jurisdiction, but not housed in a facility operated by the authority. For example, prisoners can be housed in a private facility that contracts with the correctional authority or in a halfway house and still be under the correctional authority's jurisdiction. Data in this paragraph on the number of prisoners under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities from 1980 to 2016 was downloaded from U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT)―Prisoners, https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nps. Data on prisoners under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities is found under the "Quick Tables" tab and by clicking on the link to "Prisoners under the jurisdiction of state or federal correctional authorities, December 31, 1978-2016." Because the most recent data on the number of prisoners under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) is from 2016, these data were supplemented with data from a report published by the Vera Institute of Justice that provides information on prisoners under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities in 2018. Jacob Kang-Brown, Eital Schattner-Elmaleh, and Oliver Hinds, People in Prison in 2018, Vera Institute of Justice, April 2019. |

| 8. |

BJS used a sample of 67,966 inmates to represent 401,288 inmates released from prison in 30 states in 2005. In 2005, the inmates released in the 30 states represented 77% of all inmates released from state prisons that year. Mariel Alper, Matthew R. Durose, and Joshua Markman, 2018 Update on Prisoner Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-Up Period (2005-2014), U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 250975, Washington, DC, May 2018. |

| 9. |

See Francis T. Cullen and Cheryl Lero Jonson, "Rehabilitation and Treatment Programs," in Crime and Public Policy, ed. James Q. Wilson and Joan Petersilia, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 310; David B. Wilson, Catherine A. Gallagher, and Doris L. MacKenzie, "A Meta-Analysis of Corrections-Based Education, Vocation, and Work Programs for Adult Offenders," Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, vol. 37, no. 4, November 2000, pp. 347-368; and Lois M. Davis, Robert Bozick, and Jennifer L. Steele et al., Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2013. |

| 10. |

U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Tables B23006 and B26106. |

| 11. |

Highlights From the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults, p. 24. |

| 12. |

The survey asked prisoners why they did not want to enroll in an academic class or course of study. The cost of the course was not a listed reason for why prisoners did not want to enroll in the course, but 51% of prisoners listed "other" as the reason for not enrolling, which was the most common response. Highlights From the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults, p. 29. |

| 13. |

Laura E. Gorgol and Brian A. Sponsler, Unlocking Potential: Results of a National Survey of Postsecondary Education in State Prisons, Institute for Higher Education Policy, Washington, DC, May 2011, p. 14, http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/pubs/unlocking_potential-psce_final_report_may_2011.pdf, hereinafter, "Unlocking Potential." |

| 14. |

Title IV of the HEA authorizes several student aid programs: the Pell Grant program, Iraq and Afghanistan service grants, William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (DL) Program, Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) program, and Federal Work-Study (FWS) program. See CRS Report RL31618, Campus-Based Student Financial Aid Programs Under the Higher Education Act; and CRS Report R40122, Federal Student Loans Made Under the Federal Family Education Loan Program and the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program: Terms and Conditions for Borrowers. |

| 15. |

U.S. Government Accounting Office, Prisoners Receiving Social Security and Other Federal Retirement, Disability, and Education Benefits, GAO/HRD-82-43, July 22, 1982. |

| 16. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Abuses in Federal Student Grant Programs, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., October 27-28, 1993, S.Hrg. 103-491 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1994), p. 346. |

| 17. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, Reauthorizing the Higher Education Act of 1965, report to accompany S. 1150, 102nd Cong., 1st sess., November 12, 1991, S.Rept. 102-204 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1991). |

| 18. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, Legislative Recommendations for Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act and Related Measures Part 4: Title IV, CWS, NSDL, Need Analysis, General Provisions, Miscellaneous, committee print, 102nd Cong., 1st sess., May 1991, p. 231; and U.S. Congress, House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, Legislative Recommendations for Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act and Related Measures Appendix, committee print, 102nd Cong., 1st sess., May 1991, p. 177. |

| 19. |

HEA §484(b)(5). |

| 20. |

HEA §472(6). |

| 21. |

HEA §102(a)(3)(C). The Secretary of Education has the authority to waive the prohibition for a nonprofit institution that provides a two- or four-year program of instruction for which it awards an associate's degree or postsecondary certificate, or a bachelor's or associate's degree, respectively. |

| 22. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Pell Grants for Prison Inmates, GAO/HEHS-94-224R, August 5, 1994. |

| 23. |

The Pell Grant program is often referred to as a quasi-entitlement because, since AY1991-1992 and in most years prior to AY1991-1992, students who meet the statutory and regulatory eligibility requirements receive an award amount in accordance with statutory and regulatory provisions without reductions in award amounts or imposed recipient caps. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Pell Grants for Prison Inmates, GAO/HEHS-94-224R, August 5, 1994. |

| 24. |

Truth in sentencing (TIS) laws generally refer to practices that reduce the disparity between the sentence imposed by the court and the amount of time the sentenced offender serves by reducing or eliminating good time credits and/or parole eligibility. States that implemented TIS laws generally required prisoners to serve 85% of their sentences before being eligible for release. |

| 25. |

Jon Marc Taylor, "Alternative Funding Options for Post-Secondary Correctional Education (Part One)," Journal of Correctional Education, vol. 56, no. 1 (March 2005), p. 6. |

| 26. |

Lois M. Davis, Jennifer L. Steele, and Robert Bozick et al., How Effective is Correctional Education, and Where Do We Go from Here? The Results of a Comprehensive Evaluation, The RAND Corporation, Santa Monica , CA, 2014, p. 66, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR564.html (hereinafter, "How Effective is Correctional Education, and Where Do We Go from Here?"). |

| 27. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Education and Labor, COLLEGE OPPORTUNITY AND AFFORDABILITY ACT OF 2007, To accompany H.R. 4137, 110th Cong., 1st sess., December 19, 2007, H.Rept. 110-500, p. 253. |

| 28. |

34 C.F.R. §600.2. |

| 29. |

For information on the HEA Title IV student aid programs—Federal Pell Grants, Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, Federal Work-Study Program, and Direct Loans—see CRS Report R43351, The Higher Education Act (HEA): A Primer. |

| 30. |

The "ability to benefit" may be demonstrated by passing an examination approved by the Department of Education, or by successfully completing six credits or 225 clock hours of college work applicable to a certificate or degree offered by a postsecondary institution. A career pathway program combines occupational skills training, counseling, workforce preparation, high school completion, and postsecondary credential attainment. |

| 31. |

34 C.F.R. §668.37 provides mechanisms by which individuals may establish eligibility if not registered. |

| 32. |

The UCR Program's primary objective is to generate reliable information for use in law enforcement administration, operation, and management. |

| 33. |

For more information on the types of facilities, see Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, Federal Pell Grant Eligibility for Students Confined or Incarcerated in Locations That Are Not Federal or State Penal Institutions, GEN-14-21, December 8, 2014, https://ifap.ed.gov/dpcletters/GEN1421.html. |

| 34. |

For more information on FSEOG and FWS, see CRS Report RL31618, Campus-Based Student Financial Aid Programs Under the Higher Education Act. |

| 35. |

Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, Federal Student Aid Eligibility for Students Confined in Adult Correctional or Juvenile Justice Facilities, December 2014, p. 2. |

| 36. |

Department of Education, "U.S. Department of Education Launches Second Chance Pell Pilot Program for Incarcerated Individuals," press release, July 31, 2015, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-launches-second-chance-pell-pilot-program-incarcerated-individuals. |

| 37. |

Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, "Notice Inviting Postsecondary Educational Institutions To Participate in Experiments Under the Experimental Sites Initiative; Federal Student Financial Assistance Programs Under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as Amended," 80 Federal Register 45964-45966, August 3, 2015. |

| 38. |

HEA §484(k) prevents the receipt of HEA Title IV aid for correspondence courses that do not lead to a degree. |

| 39. |

Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, "Notice Inviting Postsecondary Educational Institutions To Participate in Experiments Under the Experimental Sites Initiative; Federal Student Financial Assistance Programs Under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as Amended," 80 Federal Register 45964-45966, August 3, 2015. |

| 40. |

Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, Schools Participating in Experimental Sites, April 12, 2018, https://experimentalsites.ed.gov/exp/pdf/ESIParticipants.pdf; Kelly Field, "Can a College Education Solve the Nation's Prison Crisis?", The Chronicle of Higher Education, December 19, 2017; and Vera Institute of Justice, "Statement from Vera on U.S. Department of Education's Decision to Renew Second Chance Pell," press release, February 14, 2019, https://www.vera.org/newsroom/press-releases/statement-from-vera-on-u-s-department-of-educations-decision-to-renew-second-chance-pell. |

| 41. |

Department of Education, "Institutions selected for participation in the Second Chance Pell experiment in the 2016-2017 award year," press release, July 7, 2016, http://www2.ed.gov/documents/press-releases/second-chance-pell-institutions.pdf, as downloaded by CRS on September 18, 2018. |

| 42. |

Ibid. |

| 43. |

Each education program must be covered by the IHE's primary accrediting agency in order for students enrolled in the program to be eligible for HEA Title IV aid. Accrediting agencies enforce standards that ensure that the education programs, training, or courses of study offered by an IHE are of sufficient quality to meet the stated objectives for which the programs, training, or courses are offered. |

| 44. |

Kelly Field, "Can a College Education Solve the Nation's Prison Crisis?", The Chronicle of Higher Education, December 19, 2017. |

| 45. |

Department of Education, "Institutions selected for participation in the Second Chance Pell experiment in the 2016-2017 award year," press release, July 7, 2016, http://www2.ed.gov/documents/press-releases/second-chance-pell-institutions.pdf, as downloaded by CRS on September 18, 2018. |

| 46. |

David Rhodes, Analysis of the Experimental Sites Initiative: 2009-10, Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, June 2011, pp. 3, 28. |

| 47. |

Vera Institute of Justice, "Statement from Vera on U.S. Department of Education's Decision to Renew Second Chance Pell," press release, February 14, 2019, https://www.vera.org/newsroom/press-releases/statement-from-vera-on-u-s-department-of-educations-decision-to-renew-second-chance-pell. |

| 48. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, FEDERAL STUDENT AID: Actions Needed to Evaluate Pell Grant Pilot for Incarcerated Students, GAO-19-130, March 5, 2019. |

| 49. |

Not all participating schools offered classes under the experiment in AY2017-2018. |

| 50. |

The NCES reported that 29% of prisoners would like to enroll in programs that lead to a certificate from a college or trade school; 18% would like to enroll in programs that lead to an associate's degree; 14% would like to enroll in programs that lead to a bachelor's degree; and 8% would like to enroll in program that lead to a master's, professional, or doctorate degree. Highlights From the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults, p. 28. |

| 51. |

Wendy Erisman and Jeanne Bayer Contardo, Learning to Reduce Recidivism: A 50-State Analysis of Postsecondary Correctional Education Policy, The Institute for Higher Education Policy, Washington, DC, November 2005, p. 37, http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/pubs/learningreducerecidivism.pdf (hereinafter, "Learning to Reduce Recidivism"). |

| 52. |

The Pell Grant program is not an entitlement because it is primarily funded through discretionary appropriations. |

| 53. |

A GED is the equivalent of a high school diploma, or the completion of an eligible homeschool program can also lead to eligibility. Other options for individuals seeking Pell Grant eligibility involve the completion of one of the ability to benefit alternatives and either being enrolled in an eligible career pathway program or being initially enrolled in an eligible postsecondary program prior to July 1, 2012. The ability to benefit alternatives are either passing an examination approved by ED to be eligible for federal student aid, or completing six credits or 225 clock hours of college work applicable to a certificate or degree offered by a postsecondary institution. A career pathway program combines occupational skills training, counseling, workforce preparation, high school completion, and postsecondary credential attainment. |

| 54. |