Terrorism Risk Insurance: Overview and Issue Analysis for the 116th Congress

Prior to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, coverage for losses from such attacks was normally included in general insurance policies without additional cost to the policyholders. Following the attacks, such coverage became expensive, if offered at all. Some observers feared the absence of insurance against terrorism loss would have a wider economic impact, because insurance is required to consummate a variety of transactions (e.g., real estate). For example, if real estate deals were not completed due to lack of insurance, this could have ripple effects—such as job loss—on related industries. Terrorism insurance was largely unavailable for most of 2002, and some have argued that this adversely affected parts of the economy; others suggest the evidence is inconclusive.

Congress responded to the disruption in the insurance market with the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002 (TRIA; P.L. 107-297), which created a temporary three-year Terrorism Insurance Program. Under TRIA, the government would share the losses on commercial property and casualty insurance should a foreign terrorist attack occur, with potential recoupment of this loss sharing after the fact. TRIA requires insurers to make terrorism coverage available to commercial policyholders but does not require policyholders to purchase the coverage. The program expiration date was extended in 2005 (P.L. 109-144), 2007 (P.L. 110-160), and 2015 (P.L. 114-1). Through these reauthorizations, the prospective government share of losses has been reduced and the recoupment amount increased, although the 2007 reauthorization also expanded the program to cover losses from acts of domestic terrorism. Following P.L. 114-1, the TRIA program was slated to expire at the end of 2020.

In general terms, if a terrorist attack occurs under TRIA, the insurance industry covers the entire amount for relatively small losses. For a medium-sized loss, the government assists insurers initially but is then required to recoup the payments it made to insurers through a broad levy on insurance policies afterwards—the federal role is to spread the losses over time and over the entire insurance industry and insurance policyholders. As the size of losses grows larger, the federal government covers more of the losses without this mandatory recoupment. Ultimately, for the largest losses, the government is not required to recoup the payments it has made, although discretionary recoupment remains possible. The precise dollar values where losses cross these small, medium, and large thresholds are uncertain and will depend on how the losses are distributed among insurers.

The specifics of the current program are as follows: (1) a terrorist act must cause $5 million in insured losses to be certified for TRIA coverage; (2) the aggregate insured losses from certified acts of terrorism must be $180 million in a year for the government coverage to begin (this amount increases to $200 million in 2020); and (3) an individual insurer must meet a deductible of 20% of its annual premiums for the government coverage to begin. Once these thresholds are met, the government covers 81% of insured losses due to terrorism (this amount decreases to 80% in 2020). If the insured losses are less than $37.5 billion, the Secretary of the Treasury is required to recoup 140% of government outlays through surcharges on TRIA-eligible property and casualty insurance policies. As insured losses rise above $37.5 billion, the Secretary is required to recoup a progressively reduced amount of the outlays. At some high insured loss level, which will depend on the exact distribution of losses, the Secretary would no longer be required to recoup outlays.

Since TRIA’s passage, the private industry’s willingness and ability to cover terrorism risk have increased. According to data collected by the Treasury, in 2017, approximately 78% of insureds purchased the optional terrorism coverage, paying $3.65 billion in premiums. Over the life of the program, premiums earned by unrelated insurers have totaled $38 billion. This relative market calm has been under the umbrella of TRIA coverage and in a period in which no terrorist attacks have occurred that resulted in government payments under TRIA. It is unclear how the insurance market would react to the expiration of the federal program, although at least some instability might be expected were this to occur. In the 116th Congress, standalone legislation to extend the TRIA program for seven years (H.R. 4634 and S. 2877) was considered, and P.L. 116-94, enacted December 20, 2019, included language extending TRIA to December 31, 2027.

Terrorism Risk Insurance: Overview and Issue Analysis for the 116th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-94; H.R. 4634; S. 2877)

- Goals and Specifics of the Current TRIA Program

- Terrorism Loss Sharing Criteria

- Initial Loss Sharing

- Recoupment Provisions

- Program Administration

- TRIA Consumer Protections

- Preservation of State Insurance Regulation

- Coverage for Nonconventional Terrorism Attacks

- Nuclear, Biological, Chemical, and Radiological Terrorism Coverage

- Cyberterrorism Coverage

- Background on Terrorism Insurance

- Insurability of Terrorism Risk

- International Experience with Terrorism Risk Insurance

- Previous U.S. Experience with "Uninsurable" Risks

- The Terrorism Insurance Market

- Post-9/11 and Pre-TRIA

- After TRIA

- Evolution of Terrorism Risk Insurance Laws

Tables

Summary

Prior to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, coverage for losses from such attacks was normally included in general insurance policies without additional cost to the policyholders. Following the attacks, such coverage became expensive, if offered at all. Some observers feared the absence of insurance against terrorism loss would have a wider economic impact, because insurance is required to consummate a variety of transactions (e.g., real estate). For example, if real estate deals were not completed due to lack of insurance, this could have ripple effects—such as job loss—on related industries. Terrorism insurance was largely unavailable for most of 2002, and some have argued that this adversely affected parts of the economy; others suggest the evidence is inconclusive.

Congress responded to the disruption in the insurance market with the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002 (TRIA; P.L. 107-297), which created a temporary three-year Terrorism Insurance Program. Under TRIA, the government would share the losses on commercial property and casualty insurance should a foreign terrorist attack occur, with potential recoupment of this loss sharing after the fact. TRIA requires insurers to make terrorism coverage available to commercial policyholders but does not require policyholders to purchase the coverage. The program expiration date was extended in 2005 (P.L. 109-144), 2007 (P.L. 110-160), and 2015 (P.L. 114-1). Through these reauthorizations, the prospective government share of losses has been reduced and the recoupment amount increased, although the 2007 reauthorization also expanded the program to cover losses from acts of domestic terrorism. Following P.L. 114-1, the TRIA program was slated to expire at the end of 2020.

In general terms, if a terrorist attack occurs under TRIA, the insurance industry covers the entire amount for relatively small losses. For a medium-sized loss, the government assists insurers initially but is then required to recoup the payments it made to insurers through a broad levy on insurance policies afterwards—the federal role is to spread the losses over time and over the entire insurance industry and insurance policyholders. As the size of losses grows larger, the federal government covers more of the losses without this mandatory recoupment. Ultimately, for the largest losses, the government is not required to recoup the payments it has made, although discretionary recoupment remains possible. The precise dollar values where losses cross these small, medium, and large thresholds are uncertain and will depend on how the losses are distributed among insurers.

The specifics of the current program are as follows: (1) a terrorist act must cause $5 million in insured losses to be certified for TRIA coverage; (2) the aggregate insured losses from certified acts of terrorism must be $180 million in a year for the government coverage to begin (this amount increases to $200 million in 2020); and (3) an individual insurer must meet a deductible of 20% of its annual premiums for the government coverage to begin. Once these thresholds are met, the government covers 81% of insured losses due to terrorism (this amount decreases to 80% in 2020). If the insured losses are less than $37.5 billion, the Secretary of the Treasury is required to recoup 140% of government outlays through surcharges on TRIA-eligible property and casualty insurance policies. As insured losses rise above $37.5 billion, the Secretary is required to recoup a progressively reduced amount of the outlays. At some high insured loss level, which will depend on the exact distribution of losses, the Secretary would no longer be required to recoup outlays.

Since TRIA's passage, the private industry's willingness and ability to cover terrorism risk have increased. According to data collected by the Treasury, in 2017, approximately 78% of insureds purchased the optional terrorism coverage, paying $3.65 billion in premiums. Over the life of the program, premiums earned by unrelated insurers have totaled $38 billion. This relative market calm has been under the umbrella of TRIA coverage and in a period in which no terrorist attacks have occurred that resulted in government payments under TRIA. It is unclear how the insurance market would react to the expiration of the federal program, although at least some instability might be expected were this to occur. In the 116th Congress, standalone legislation to extend the TRIA program for seven years (H.R. 4634 and S. 2877) was considered, and P.L. 116-94, enacted December 20, 2019, included language extending TRIA to December 31, 2027.

Introduction

Prior to the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, insurers generally did not exclude or separately charge for coverage of terrorism risk. The events of September 11, 2001, changed this as insurers realized the extent of possible terrorism losses. Estimates of insured losses from the 9/11 attacks are more than $45 billion in current dollars, the largest insured losses from a nonnatural disaster on record. These losses were concentrated in business interruption insurance (34% of the losses), property insurance (30%), and liability insurance (23%).1

Although primary insurance companies—those that actually sell and service the insurance policies bought by consumers—suffered losses from the terrorist attacks, the heaviest insured losses were absorbed by foreign and domestic reinsurers, the insurers of insurance companies. Because of the lack of public data on, or modeling of, the scope and nature of the terrorism risk, reinsurers felt unable to accurately price for such risks and largely withdrew from the market for terrorism risk insurance in the months following September 11, 2001. Once reinsurers stopped offering coverage for terrorism risk, primary insurers, suffering equally from a lack of public data and models, also withdrew, or tried to withdraw, from the market. In most states, state regulators must approve policy form changes. Most state regulators agreed to insurer requests to exclude terrorism risks from commercial policies, just as these policies had long excluded war risks. Terrorism risk insurance was soon unavailable or extremely expensive, and many businesses were no longer able to purchase insurance that would protect them in future terrorist attacks. In some cases, such insurance is required to consummate various transactions, particularly in the real estate, transportation, construction, energy, and utility sectors. Although the evidence is largely anecdotal, some were concerned that the lack of coverage posed a threat of serious harm—such as job loss—to these industries, in turn threatening the broader economy.

In November 2002, Congress responded to the fears of economic damage due to the absence of commercially available coverage for terrorism with passage of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA).2 TRIA created a three-year Terrorism Insurance Program to provide a government reinsurance backstop in the case of terrorist attacks. Prior to the 116th Congress, the TRIA program was amended and extended in 2005,3 2007,4 and 2015.5 Following the 2015 amendments, the TRIA program was set to expire at the end of 2020. (A side-by-side of the original law and the 2005, 2007, and 2015 reauthorization acts is in Table 1.)

The executive branch has been skeptical about the TRIA program in the past. Bills to expand TRIA were resisted by then-President George W. Bush's Administration,6 and previous presidential budgets under then-President Barack Obama called for changes in the program that would have had the effect of scaling back the TRIA coverage.7 The Trump Administration has not called for specific changes to TRIA, but has indicated that it is "evaluating reforms…to further decrease taxpayer exposure."8

The insurance industry largely continues to support TRIA,9 as do commercial insurance consumers in the real estate and other industries that have formed a "Coalition to Insure Against Terrorism" (CIAT).10 However, not all insurance consumers have consistently supported the renewal of TRIA. For example, the Consumer Federation of America has questioned the need for the program in the past.11

Although the United States has suffered attacks deemed "terrorism" since the passage of TRIA, no acts of terrorism have been certified and no payments have occurred under TRIA. For example, although the April 2013 bombing in Boston was termed an "act of terror," by the President,12 the insured losses in TRIA-eligible insurance from that bombing did not cross the $5 million statutory threshold to be certified under TRIA. (See precise criteria under the TRIA program below.)

Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-94; H.R. 4634; S. 2877)

H.R. 4634 was introduced on October 11, 2019, and ordered reported following a House Financial Services Committee hearing and markup.13 The House passed the bill on a 385-22 vote on November 18, 2019. The Senate Banking Committee held a hearing on the issue in June 2019,14 and S. 2877 was introduced November 14, 2019, and reported without a written report on December 3, 2019.

Both H.R. 4634 and S. 2877 would extend the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program by seven years, until December 31, 2027, with the various mandatory recoupment provisions (Section 103(e)(7)(E)(i)) also extended. During the House committee markup, two reporting requirements were added to the bill: (1) the Treasury would be directed to add to the annual ongoing report on market conditions an evaluation of the availability and affordability of terrorism risk insurance for places of worship; and 2) the Comptroller General would be directed to report on cyberterrorism and TRIA. S. 2877, as introduced, also included these reporting requirements.

The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (H.R. 1865 as amended) included the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2019 in Division I, Title V. The House passed the bill on December 17, 2019, and the Senate did so on December 19, 2019. The President signed H.R. 1865 into law (P.L. 116-94) on December 20, 2019.

Goals and Specifics of the Current TRIA Program

The original TRIA legislation's stated goals were to (1) create a temporary federal program of shared public and private compensation for insured terrorism losses to allow the private market to stabilize; (2) protect consumers by ensuring the availability and affordability of insurance for terrorism risks; and (3) preserve state regulation of insurance. Although Congress has amended specific aspects of the original act, the operation of the program generally usually follows the original statute. The changes to the program have largely reduced the government coverage for terrorism losses, except that the 2007 amendments expanded coverage to domestic terrorism losses, rather than limiting the program to foreign terrorism. The 2019 extension made no substantive changes except for extending the program.

Terrorism Loss Sharing Criteria

To meet the first goal, the TRIA program creates a mechanism through which the federal government could share insured commercial property and casualty losses with the private insurance market. 15 The role of federal loss sharing depends on the size of the insured loss. For a relatively small loss, there is no federal sharing. For a medium-sized loss, the federal role is to spread the loss over time and over the entire insurance industry. The federal government provides assistance up front but then recoups the payments it made through a broad levy on insurance policies afterwards. For a large loss, the federal government is to pay most of the losses, although recoupment is possible (but not mandatory) in these circumstances as well. The precise dollar values where losses cross these small, medium, and large thresholds are uncertain and will depend on how the losses are distributed among insurers. For example, for loss sharing to occur, an attack must meet a certain aggregate dollar value and each insurer must pay out a certain amount in claims—known as its deductible. For some large insurers, this individual deductible might be higher than the aggregate threshold set in statute, meaning that loss sharing might not actually occur until a higher level than the figure set in statute.

The criteria under the TRIA program in 2019 are as follows:

- 1. An individual act of terrorism must be certified by the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security and Attorney General; losses must exceed $5 million in the United States or to U.S. air carriers or sea vessels for an act of terrorism to be certified.

- 2. The federal government shares in an insurer's losses due to a certified act of terrorism only if "the aggregate industry insured losses resulting from such certified act of terrorism" exceed $180 million (increasing to $200 million in 2020). 16

- 3. The federal program covers only commercial property and casualty insurance, and it excludes by statute several specific lines of insurance.17

- 4. Each insurer is responsible for paying a deductible before receiving federal coverage. An insurer's deductible is proportionate to its size, equaling 20% of an insurer's annual direct earned premiums for the commercial property and casualty lines of insurance specified in TRIA.

- 5. Once the $180 million aggregate loss threshold and 20% deductible are met, the federal government would cover 81% of each insurer's losses above its deductible until the amount of losses totals $100 billion.

- 6. After $100 billion in aggregate losses, there is no federal government coverage and no requirement that insurers provide coverage.

- 7. In the years following the federal sharing of insurer losses, the Secretary of the Treasury is required to establish surcharges on TRIA-eligible property and casualty insurance policies to recoup 140% of some or all of the outlays to insurers under the program. If losses are high, the Secretary has the authority to assess surcharges, but is not required to do so. (See "Recoupment Provisions" below for more detail.)

Initial Loss Sharing

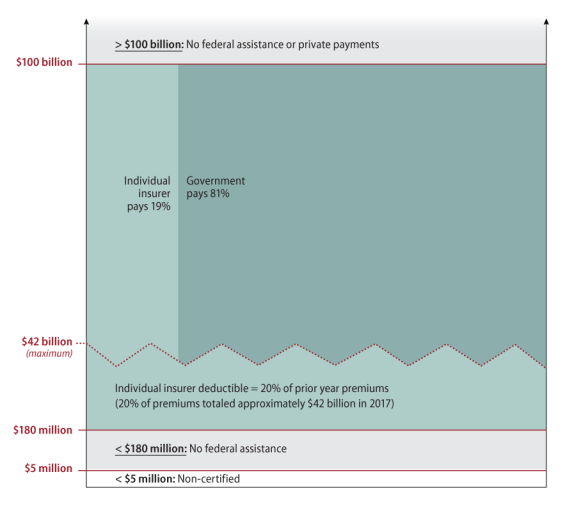

The initial loss sharing under TRIA can be seen in Figure 1, adapted from a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report. The exact amount of the 20% deductible at which TRIA coverage would begin depends on how the losses are distributed among insurance companies. In the aggregate, 20% of the direct-earned premiums for all of the property and casualty lines specified in TRIA totaled approximately $42 billion in 2017, according to data collected by the Treasury Department. TRIA coverage is likely, however, to begin well under this amount as the losses from an attack are unlikely to be equally distributed among insurance companies.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), adapted from Congressional Budget Office, Federal Reinsurance for Terrorism Risks: Issues in Reauthorization, August 1, 2007, p. 12. Note: Aggregate of all individual insurer deductibles totaled approximately $42 billion in 2017, according to Department of the Treasury data and CRS calculations. Loss sharing is likely to begin well under this amount as the distribution of terrorism losses is unlikely to be equally spread among insurers. |

Recoupment Provisions

The precise amount TRIA requires the Treasury to recoup after the initial loss sharing is determined by the interplay between a number of different factors in the law and insurance marketplace. The general result of the recoupment provisions is that, for attacks that result in under $37.5 billion in insured losses,18 the Treasury Secretary is required to recoup 140% of the government outlays through surcharges on property and casualty insurance policies. For events with insured losses over $37.5 billion, the Secretary has discretionary authority to recoup all the government outlays and may be required to partially recoup the government outlays depending on the size of the attacks and the amount of uncompensated losses paid by the insurance industry. (See the Appendix for more information on exact recoupment calculations.)

If the requirement for recoupment is triggered, TRIA, as amended by P.L. 116-94, requires the government to recoup all payments prior to the end of FY2029, with an accelerated schedule if the payments occurred prior to end of 2023. Thus such recoupment would be completed within a 10-year timeframe following enactment. For an attack causing significant insured loses, however, this requirement could result in high surcharges being applied for a relatively short time. The recoupment surcharges are to be imposed as a percentage of premiums paid on all TRIA-eligible property and casualty insurance policies, but the Secretary has the authority to adjust the amount of the premiums taking into consideration differences between rural and urban areas and the terrorism exposures of different lines of insurance.

Program Administration

The administration of the TRIA program was originally left generally to the Treasury Secretary. This was changed somewhat in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010.19 The act created a new Federal Insurance Office (FIO) to be located within the Department of the Treasury. Among the duties specified for the FIO in the legislation was to assist the Secretary in the administration of the Terrorism Insurance Program.20

TRIA Consumer Protections

TRIA addresses the second goal—to protect consumers—by requiring insurers that offer TRIA-covered lines of insurance to make terrorism insurance available prospectively to their commercial policyholders. This coverage may not differ materially from coverage for other types of losses. Each terrorism insurance offer must reveal both the premium charged for terrorism insurance and the possible federal share of compensation. Policyholders are not, however, required to purchase coverage under TRIA.21 If a policyholder declines to purchase terrorism coverage, the insurer may exclude terrorism losses. Federal law does not limit what insurers can charge for terrorism risk insurance, although state regulators typically have the authority under state law to modify excessive, inadequate, or unfairly discriminatory rates.

Preservation of State Insurance Regulation

TRIA's third goal—to preserve state regulation of insurance—is expressly accomplished in Section 106(a), which provides that "Nothing in this title shall affect the jurisdiction or regulatory authority of the insurance commissioner [of a state]." The Section 106(a) provision has two exceptions, one permanent and one temporary (and expired): (1) the federal statute preempts any state definition of an "act of terrorism" in favor of the federal definition and (2) the statute briefly preempted state rate and form approval laws for terrorism insurance from enactment to the end of 2003. In addition to these exceptions, Section 105 of the law also preempts state laws with respect to insurance policy exclusions for acts of terrorism.

Coverage for Nonconventional Terrorism Attacks

The TRIA statute does not specifically include or exclude property and casualty insurance coverage for terrorist attacks according to the particular methods used in the attacks, such as nuclear, biological, chemical, and radiological (NBCR) and cyberterrorism risks. Such nonconventional means, however, have the potential to cause losses that may or may not end up being covered by TRIA and have been a source of particular concern and attention in the past.

Nuclear, Biological, Chemical, and Radiological Terrorism Coverage

Some observers consider a terrorist attack with some form of NBCR weapon to be the most likely type of attack causing large scale losses. 22 The current TRIA statute does not specifically include or exclude NBCR events; thus, the TRIA program in general would cover insured losses from terrorist actions due to NCBR as it would for an attack by conventional means. The term insured losses, however, is a meaningful distinction. Except for workers' compensation insurance, most insurance policies that would fall under the TRIA umbrella include exclusions that would likely limit insurer coverage of an NCBR event, whether it was due to terrorism or to some sort of accident, although these exclusions have never been legally tested in the United States after a terrorist event.23 If these exclusions are invoked and do indeed limit the insurer losses due to NBCR terrorism, they would also limit the TRIA coverage of such losses. Language that would have specifically extended TRIA coverage to NBCR events was offered in the past,24 but was not included in legislation as enacted. In 2007, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) was directed to study the issue and a GAO report was issued in 2008, finding that "insurers generally remain unwilling to offer NBCR coverage because of uncertainties about the risk and the potential for catastrophic losses."25 In the past, legislation (e.g., H.R. 4871 in the 113th Congress) would have provided for differential treatment of NBCR attacks under TRIA, but such legislation has not been enacted.

Cyberterrorism Coverage

Concern regarding potential damage from cyberterrorism has grown as increasing amounts of economic activity occur online. The TRIA statute does not specifically address the potential for cyberterrorism, thus, there was uncertainty about such attacks would be covered in the same manner as terrorist attacks using conventional means. In 2016, state insurance regulators introduced a new Cyber Liability line of insurance, raising questions as to whether coverage under this line would be covered under TRIA, or whether it would not be covered under the law's exclusion of "professional liability" insurance. The Department of the Treasury released guidance in December 2016 clarifying that "stand-alone cyber insurance policies reported under the 'Cyber Liability' line are included in the definition of 'property and casualty insurance' under TRIA."26

Despite Treasury's guidance, cyberterrorism coverage remains a particular concern. The Treasury Department devoted a specific section of the latest report on TRIA to cyber coverage, reporting that 50% of standalone cyber insurance policies (based on premium value) included terrorism coverage. The take-up rate for those choosing cyber coverage that is embedded in policies covering additional perils was 54%. These rates are similar to, but slightly lower than, the 62% take-up rate for general terrorism coverage found across all TRIA-eligible lines.27

P.L. 116-94 includes a requirement for the Comptroller General to study and report on cyberterrorism, including the potential costs of cyberattacks, the new, state-defined cyber liability line of insurance's adequacy, the private market's ability to adequately price cyber risks, and the TRIA structure's appropriateness for covering cyberterrorism.

Background on Terrorism Insurance

Insurability of Terrorism Risk

Stripped to its most basic elements, insurance is a fairly straightforward operation. An insurer agrees to assume an indefinite future risk in exchange for a definite current premium. The insurer pools a large number of risks such that, at any given point in time, the ongoing losses will not be larger than the current premiums being paid, plus the residual amount of past premiums that the insurer retains and invests, plus, in a last resort, any borrowing against future profits if this is possible. For the insurer to operate successfully and avoid failure, it is critical to accurately estimate the probability of a loss and the severity of that loss so that a sufficient premium can be charged. Insurers generally depend upon huge databases of past loss information in setting these rates. Everyday occurrences, such as automobile accidents or natural deaths, can be estimated with great accuracy. Extraordinary events, such as large hurricanes, are more difficult, but insurers have many years of weather data, coupled with sophisticated computer models, with which to make predictions.

Many see terrorism risk as fundamentally different from other risks, and thus it is often perceived as uninsurable by the private insurance market without government support for the most catastrophic risk. The argument that catastrophic terrorism risk is uninsurable typically focuses on lack of public data about both the probability and severity of terrorist acts. The reason for the lack of historical data is generally seen as a good thing—few terrorist attacks are attempted and fewer have succeeded. Nevertheless, the insurer needs some type of measurable data to determine which terrorism risks it can take on without putting the company at risk of failure. As a replacement for large amounts of historical data, insurers turn to various forms of terrorism models similar to those used to assess future hurricane losses. Even the best model, however, can only partly replace good data, and terrorism models are still relatively new compared with hurricane models.

One prominent insurance textbook identifies four ideal elements of an insurable risk: (1) a sufficiently large number of insureds to make losses reasonably predictable; (2) losses must be definite and measurable; (3) losses must be fortuitous or accidental; and (4) losses must not be catastrophic (i.e., it must be unlikely to produce losses to a large percentage of the risks at the same time).28 Terrorism risk in the United States would appear to fail the first criterion as terrorism losses have not proved predictable over time. Losses to terrorism, when they occur, are generally definite and measurable, so terrorism risk could pass under criteria two. Such risk, however, also likely fails the third criterion due to the malevolent human actors behind terrorist attacks, whose motives, means, and targets of attack are constantly in flux. Whether it fails the fourth criterion is largely decided by the underwriting actions of insurers themselves (i.e., whether the insurers insure a large number of risks in a single geographic area that would be affected by a terrorist strike). Unsurprisingly, insurers generally have sought to limit their exposures in particular geographic locations with a conceptually higher risk for terrorist attacks, making terrorism insurance more difficult to find in those areas.

International Experience with Terrorism Risk Insurance29

Although the U.S. experience with terrorism is relatively limited, other countries have dealt with the issue more extensively and have developed their own responses to the challenges presented by terrorism risk. Spain, which has seen significant terrorist activity by Basque separatist movements, insures against acts of terrorism via a broader government-owned reinsurer that has provided coverage for catastrophes since 1954. The United Kingdom (UK), responding to the Irish Republican Army attacks in the 1980s, created Pool Re, a privately owned mutual insurance company with government backing, specifically to insure terrorism risk. In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks, many foreign countries reassessed their terrorism risks and created a variety of approaches to deal with the risks. The UK greatly expanded Pool Re, whereas Germany created a private insurer with government backing to offer terrorism insurance policies. Germany's plan, like the United States' TRIA, was created as a temporary measure. It has been extended since its inception, most recently until the end of 2019.30 Not all countries, however, concluded that some sort of government backing for terrorism insurance was necessary. Canada specifically considered, and rejected, creating a government program following September 11, 2001.31

Previous U.S. Experience with "Uninsurable" Risks

Terrorism risk post-2001 is not the first time the United States has faced a risk perceived as uninsurable in private markets that Congress chooses to address through government action. During World War II, for example, Congress created a "war damage" insurance program and it expanded a program insuring against aviation war risk following September 11, 2002. 32 Since 1968, the National Flood Insurance Program has covered most of the insured flooding losses in the United States.33

The closest previous analog to the situation with terrorism risk may be the federal riot reinsurance program created in the late 1960s. Following large scale riots in American cities in the late 1960s, insurers generally pulled back from insuring in those markets, either adding policy exclusions to limit their exposure to damage from riots or ceasing to sell property damage insurance altogether. In response, Congress created a riot reinsurance program as part of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968.34 The federal riot reinsurance program offered reinsurance contracts similar to commercial excess reinsurance. The government agreed to cover some percentage of an insurance company's losses above a certain deductible in exchange for a premium paid by that insurance company. Private reinsurers eventually returned to the market, and the federal riot reinsurance program was terminated in 1985.

The Terrorism Insurance Market

Post-9/11 and Pre-TRIA

The September 2001 terrorist attacks, and the resulting billions of dollars in insured losses, caused significant upheaval in the insurance market. Even before the attacks, the insurance market was showing signs of a cyclical "hardening" of the market in which prices typically rise and availability is somewhat limited. The unexpectedly large losses caused by terrorist acts exacerbated this trend, especially with respect to the commercial lines of insurance most at risk for terrorism losses. Post-September 11, insurers and reinsurers started including substantial surcharges for terrorism risk, or, more commonly, they excluded coverage for terrorist attacks altogether. Reinsurers could make such rapid adjustments because reinsurance contracts and rates are generally unregulated. Primary insurance contracts and rates are more closely regulated by the individual states, and the exclusion of terrorism coverage for the individual insurance purchaser required regulatory approval at the state level in most cases. States acted fairly quickly, and, by early 2002, 45 states had approved insurance policy language prepared by the Insurance Services Office, Inc. (ISO, an insurance consulting firm), excluding terrorism damage in standard commercial policies.35

The lack of readily available terrorism insurance caused fears of a larger economic impact, particularly on the real estate market. In most cases, lenders prefer or require that a borrower maintain insurance coverage on a property. Lack of terrorism insurance coverage could lead to defaults on existing loans and a downturn in future lending, causing economic ripple effects as buildings are not built and construction workers remain idle.

The 14-month period after the September 2001 terrorist attacks and before the November 2002 passage of TRIA provides some insight into the effects of a lack of terrorism insurance. Some examples in September 2002 include the Real Estate Roundtable releasing a survey finding that "$15.5 billion of real estate projects in 17 states were stalled or cancelled because of a continuing scarcity of terrorism insurance"36 and Moody's Investors Service downgrading $4.5 billion in commercial mortgage-backed securities.37 This picture, however, was not uniform. For example, in July 2002, The Wall Street Journal reported that "despite concerns over landlords' ability to get terrorism insurance, trophy properties were in demand."38 CBO concluded in 2005 that "[TRIA] appears to have had little measurable effect on office construction, employment in the construction industry, or the volume of commercial construction loans made by large commercial banks," but CBO also noted that a variety of economic factors at the time "could be masking positive macroeconomic effects of TRIA."39

After TRIA

TRIA's "make available" provisions addressed the availability problem in the terrorism insurance market, as insurers were required by law to offer commercial terrorism coverage. However, significant uncertainty existed as to how businesses would react, because there was no general requirement to purchase terrorism coverage and the pricing of terrorism coverage was initially high. 40 Analyzing the terrorism insurance market in the aftermath of TRIA is challenging as well since there was no consistent regulatory reporting by insurers until P.L. 114-1 required detailed reporting, which Treasury began in 2016. Before this time, data on terrorism insurance typically stemmed from insurance industry surveys or rating bureaus. In examining the terrorism insurance market since TRIA, it is also important to note that no terrorist attacks have occurred that reached TRIA thresholds, thus property and casualty insurance has not made any large scale payouts for terrorism damages.

The initial consumer reaction to the terrorism coverage offers was relatively subdued. Marsh, Inc., a large insurance broker, reported that 27% of their clients bought terrorism insurance in 2003. This take-up rate, however, climbed relatively quickly to 49% in 2004 and 58% in 2005. Marsh reported that, since 2005, the overall take-up rate has remained near 60%, with Marsh reporting a rate of 62% in 2017.41 The Treasury reports based on industry data calls have found similar or higher take-up rates. For 2017, Treasury found that the take-up rate based on premium volumes was 62%, whereas based on policy counts, the rate was 78%.42

The price for terrorism insurance has appeared to decline over time, although the level of pricing reported may not always be comparable between sources. The 2013 report by the President's Working Group on Financial Markets, based on survey data by insurance broker Aon, showed a high of above 7% for the median terrorism premium as a percentage of the total property premium in 2003, with a generally downward trend, and more recent values around 3%.43 The trend may be downward, but there has been variability, particularly across industries. For example, Marsh reported rates in 2009 as high as 24% of the property premium for financial institutions and as low as 2% in the food and beverage industry.44 In the 2013 Marsh report, this variability was lower as 2012 rates varied from 7% in the transportation industry and the hospitality and gaming industry to 1% in the energy and mining industry.45 In 2017, Marsh found rates varying from 10% in hospitality and gaming to 2% in energy and mining and construction industries. The 2018 Treasury report, based on lines of insurance, not on industry category, found premiums varying from 6.1% in excess workers' compensation to 1.4% in ocean marine in 2017.46

Treasury found that the total premium amount paid for terrorism coverage in 2017 was approximately $3.65 billion, or 1.75%, of the $209.15 billion in total premiums for TRIA-eligible lines of insurance.47 Since the passage of TRIA, Treasury estimates that a total of approximately $38 billion was earned for terrorism coverage by non-related insurers, with another $7.4 billion earned by captive insurers (i.e., insurers who are owned by the insureds).

In general, the capacity of insurers to bear terrorism risk has increased over the life of the TRIA program. The combined policyholder surplus among all U.S. property and casualty insurers was $686.9 billion at the end of 2017 compared to $408.6 billion (inflation adjusted) at the start of 2002.48 This $686.9 billion has been bolstered by the estimated $38 billion in premiums paid for terrorism coverage over the years without significant claims payments. The policyholder surplus, however, backs all property and casualty insurance policies in the United States and is subject to depletion in a wide variety of events. For example, extreme weather losses could particularly draw capital away from the terrorism insurance market, because events such as hurricanes share some characteristics—low frequency and the possibility of catastrophic levels of loss—with terrorism risk.

Evolution of Terrorism Risk Insurance Laws

Table 1 presents a side-by-side comparison of selected provisions from the original TRIA law, along with the reauthorizing laws of 2005, 2007, and 2015.

|

Provision |

Original 2002 Law |

2005 Reauthorization |

2007 Reauthorization |

2015 Reauthorization |

|

Title |

Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002 |

Terrorism Risk Insurance Extension Act of 2005 |

Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2007 |

Terrorism Risk Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015 |

|

Expiration Date |

December 31, 2005 |

December 31, 2007 (§2) |

December 31, 2014 (§3(a)) |

December 31, 2020 (§101) |

|

"Act of Terrorism" Definition |

For an act of terrorism to be covered under TRIA, it must be a violent act committed on behalf of a foreign person or interest as part of an effort to coerce the U.S. civilian population or influence U.S. government policy. It must have resulted in damage within the United States or to a U.S. airliner or mission abroad. Terrorist act is to be certified by the Secretary of the Treasury in concurrence with the Attorney General and Secretary of State. |

No Change. |

Removed requirement that a covered act of terrorism be committed on behalf of a foreign person or interest (thus expanding coverage to domestic terrorism). (§2) |

Removed Secretary of State from certification process and inserted Secretary of Homeland Security. (§105) |

|

Limitation on Act of Terrorism Certification in Case of War |

Terrorist act would not be covered in the event of a war, except for workers' compensation insurance. (§102(1)(B)(I)) |

No Change. |

No Change. |

No Change. |

|

Minimum Damage To Be Certified |

Terrorist act must cause more than $5 million in property and casualty insurance losses to be certified. (§102(1)(B)(ii)) |

No Change. |

No Change. |

No Change. |

|

Aggregate Industry Loss Requirement/Program Trigger |

No Provision |

Created a "program trigger" that would prevent coverage under the program unless "aggregate industry losses resulting from such certified act of terrorism" exceed $50 million in 2006 and $100 million for 2007. (§6) |

No Change. Program trigger remains at $100 million until 2014. (§3(c)) |

Program trigger increased $20 million per year until it reaches $200 million in 2020. (§102) |

|

Insurer Deductible |

7% of earned premium for 2003, 10% of earned premium for 2004, 15% of earned premium for 2005. (§102(7)) |

Raised deductible to 17.5% for 2006 and 20% for 2007. (§3) |

No Change. Deductible remained at 20% until 2014. (§3(c)) |

No Change. Deductible remained at 20% for each calendar year of the program. (§106) |

|

Covered Lines of Insurance |

Commercial property and casualty insurance, including excess insurance, workers' compensation, and surety but excluding crop insurance, private mortgage insurance, title insurance, financial guaranty insurance, medical malpractice insurance, health or life insurance, flood insurance, or reinsurance. |

Excluded commercial auto, burglary and theft, professional liability (except for directors and officers liability), and farm owners multiple peril from coverage. (§3) |

No Change. |

No Change. |

|

Mandatory Availability |

Every insurer must make available terrorism coverage that does not differ materially from coverage applicable to losses other than terrorism. (§103(c)) |

No Change. Mandatory availability extended through 2007. (§2(b)) |

No Change. Mandatory availability extended through 2014. (§3(c)) |

No Change. Mandatory availability in effect for each calendar year of the program. (§106) |

|

Insured Loss Shared Compensation |

Federal share of losses will be 90% for insured losses that exceed the applicable insurer deductible. (§103(e)) |

Reduced federal share of losses to 85% for 2007. (§4) |

No Change. Federal share remained at 85% through 2014. |

Reduced federal share one percentage point per year until it reaches 80%. (§102) |

|

Cap on Annual Liability |

Federal share of compensation paid under the program will not exceed $100 billion and insurers are not liable for any portion of losses that exceed $100 billion unless Congress acts otherwise to cover these losses. |

No Change. |

Removed the possibility that a future Congress could require insurers to cover some share of losses above $100 billion if the insurer has met its individual deductible. Requires insurers to clearly disclose this to policy holders. |

No Change. |

|

Payment Procedures if Losses Exceed $100,000,000,000 |

After notice by the Secretary of the Treasury, Congress determines the procedures for payments if losses exceed $100 billion. |

No Change. |

Required Secretary of the Treasury to publish regulations within 240 days of passage regarding payments if losses exceed $100 billion. (§4(c)) |

No Change. |

|

Aggregate Retention Amount Maximum |

$10 billion for 2002-2003, $12.5 billion for 2004, $15 billion for 2005 |

Raised amount to $25 billion for 2006 and $27.5 billion for 2007. (§5) |

No Change. Aggregate retention remained at $27.5 billion through 2014. |

Raises amount $2 billion per year until it reaches $37.5 billion. Beginning in 2020, sets the amount equal to annual average of the sum of insurer deductibles for previous three years. (§104) |

|

Mandatory Recoupment of Federal Share |

If insurer losses are less than the aggregate retention amount, a mandatory recoupment of the federal share of the loss will be imposed. If insurer losses are over the aggregate retention amount, such recoupment is at the discretion of the Secretary of the Treasury. |

No Change. |

Increases total recoupment amount to be collected by the premium surcharges to 133% of the previously defined mandatory recoupment amount. Full mandatory recoupment must occur by September 30, 2017. (§4(e)(1)) |

Increases total recoupment amount to be collected by the premium surcharges to 140% of the previously defined mandatory recoupment amount. Full mandatory recoupment must occur by September 30, 2024. (§104) |

|

Recoupment Surcharge |

Surcharge is limited to 3% of property-casualty insurance premium and may be adjusted by the Secretary to take into account the economic impact of the surcharge on urban commercial centers, the differential risk factors related to rural areas and smaller commercial centers, and the various exposures to terrorism risk across lines of insurance. (§103(e)(8)) |

No Change. |

Removed 3% limit for mandatory surcharge. |

No Change. |

Source: The Congressional Research Service using public laws obtained from the Government Publishing Office through http://www.congress.gov.

Notes: Section numbers for the initial TRIA law are as codified in 15 U.S.C. §6701 note. Section numbers for P.L. 109-144, P.L. 110-160, and P.L. 114-1 are from the legislation as enacted.

Appendix. Calculation of TRIA Recoupment Amounts

Table A-1 contains illustrative examples of how the recoupment for the government portion of terrorism losses under TRIA might be calculated in the aggregate for various sizes of losses. The total amount of the combined deductibles in the table is simply assumed to be 30% of the insured losses for illustrative purposes. (The actual deductible amount is, as detailed above, based on the total amount of premiums collected by each insurer.) Without knowing the actual distribution of losses due to a terrorist attack, it is impossible to know what the actual total combined deductible amount would be. Table conclusions with regard to recoupment, however, hold across different actual deductible amounts.49

The specific provisions of the law define the "insurance marketplace aggregate retention amount" (Column F) for 2019 as the lesser of $37.5 billion or the total amount of insured losses (Column A). The "mandatory recoupment amount" (Column G) is defined as the difference between $37.5 billion and the aggregate insurer losses that were not compensated for by the program (i.e., the total of the insurers' deductible (Column B) and their 19% loss share (Column C)). If the aggregate insured loss is less than $37.5 billion, the law requires recoupment of 140% of the government outlays (Column H). For insured losses over $37.5 billion, the mandatory recoupment amount decreases, thus the Secretary would be required to recoup less than 133% of the outlays. Depending on the precise deductible amounts, the uncompensated industry losses (Column D) may eventually rise to be greater than $37.5 billion, which would then mean that the mandatory recoupment provisions would not apply. The Secretary would still retain discretionary authority to apply recoupment surcharges no matter what level uncompensated losses reached.

|

Column A |

Column B |

Column C |

Column D |

Column E |

Column F |

Column G |

Column H |

|

Theoretical Insured Losses |

Theoretical Combined Insurer Deductible |

Insurer 19% Share of Insured Losses |

Insurance Industry Un-compensated Losses |

Government 81% Share of Insured Losses |

Aggregate Retention Amount |

Mandatory Recoupment Amount |

Required Recoupment Amount |

|

$0.50 |

$0.15 |

$0.07 |

$0.22 |

$0.28 |

$0.50 |

$0.28 |

$0.40 |

|

$1.0 |

$0.3 |

$0.13 |

$0.4 |

$0.6 |

$1.0 |

$0.6 |

$0.8 |

|

$5.0 |

$1.5 |

$0.67 |

$2.2 |

$2.8 |

$5.0 |

$2.8 |

$4.0 |

|

$10.0 |

$3.0 |

$1.33 |

$4.3 |

$5.7 |

$10.0 |

$5.7 |

$7.9 |

|

$20.0 |

$6.0 |

$2.66 |

$8.7 |

$11.3 |

$20.0 |

$11.3 |

$15.9 |

|

$30.0 |

$9.0 |

$3.99 |

$13.0 |

$17.0 |

$30.0 |

$17.0 |

$23.8 |

|

$37.5 |

$11.3 |

$4.99 |

$16.2 |

$21.3 |

$37.5 |

$21.3 |

$29.8 |

|

$50.0 |

$15.0 |

$6.65 |

$21.7 |

$28.4 |

$37.5 |

$15.9 |

$22.2 |

|

$75.0 |

$22.5 |

$9.98 |

$32.5 |

$42.5 |

$37.5 |

$5.0 |

$7.0 |

|

$100.0 |

$30.0 |

$13.30 |

$43.3 |

$56.7 |

$37.5 |

$0 |

$0 |

Source: U.S. Treasury, TRIA statute as amended; calculations by CRS.

Notes: Totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding. For illustrative purposes, the combined insurer deductible amount set at 30% of the insured loss size; actual deductible varies depending on the distribution of events.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Insurance Information Institute (III), Background on: Terrorism Risk and Insurance, at https://www.iii.org/article/background-on-terrorism-risk-and-insurance; III figures further adjusted using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

| 2. |

P.L. 107-297; 116 Stat. 2322, codified at 15 U.S.C. §6701 note. For more information, see CRS Report RS21444, The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act of 2002: A Summary of Provisions, by Baird Webel. |

| 3. |

P.L. 109-144; 119 Stat. 2660. For more information, see CRS Report RL33177, Terrorism Risk Insurance Legislation in 2005: Issue Summary and Side-by-Side, by Baird Webel. |

| 4. |

P.L. 110-160; 121 Stat 1839. For more information, see CRS Report RL34219, Terrorism Risk Insurance Legislation in 2007: Issue Summary and Side-by-Side, by Baird Webel. |

| 5. |

P.L. 114-1; 129 Stat 3. For more information, see CRS Report R43849, Terrorism Risk Insurance Legislation in the 114th Congress: Issue Summary and Side-by-Side Analysis, by Baird Webel. |

| 6. |

See, for example, the Statement of Administration Policy on H.R. 2761 dated December 11, 2007, at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/110-1/hr2761sap-h.pdf. |

| 7. |

See, for example, Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the United States, FY2011, p. 184, at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BUDGET-2011-PER/pdf/BUDGET-2011-PER.pdf. |

| 8. |

OMB, A Budget for a Better America – President's Budget FY2020, p. 83, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/budget-fy2020.pdf. |

| 9. |

See, for example, "U.S. insurers seek renewal of federal 'backstop' against acts of terrorism," Reuters, March 5, 2019, at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-insurance-terrorism-program-idUSKCN1QM1CI. |

| 10. |

See the CIAT website at http://www.insureagainstterrorism.org. |

| 11. |

Consumer Federation of America, "Growing Insurer Surplus Calls into Question Industry Need for Congressional Renewal of Terrorism Insurance," May 8, 2013, at http://consumerfed.org/news/666. |

| 12. |

The White House, "Statement by the President," press release, April 16, 2013, at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/04/16/statement-president. |

| 13. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development, and Insurance and Subcommittee on National Security, International Development, and Monetary Policy, Protecting America: The Reauthorization of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, hearing on H.R. 4634, 116th Cong., 1st sess., October 16, 2019, at https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404481. Also see https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=404489. |

| 14. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, The Reauthorization of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, hearing, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 18, 2019, at https://www.banking.senate.gov/hearings/the-reauthorization-of-the-terrorism-risk-insurance-program. |

| 15. |

Commercial insurance is generally insurance purchased by businesses in contrast to personal lines of insurance, which is purchased by individuals. This means damage to individual homes and autos, for example, would not be covered under the TRIA program. Property and casualty insurance generally includes most lines of insurance except for life insurance and health insurance. The TRIA statutory definition in §102(11) specifically excludes "(i) federal or private crop insurance; (ii) private mortgage insurance or title insurance; (iii) financial guaranty insurance issued by monoline insurers; (iv) medical malpractice insurance; (v) health or life insurance, including group life insurance; (vi) federal flood insurance; (vii) reinsurance or retrocessional reinsurance; (vii) commercial automobile insurance; (ix) burglary and theft insurance; (x) surety insurance; (xi) professional liability insurance; or (xii) farm owners multiple peril insurance." |

| 16. |

15 U.S.C. §6701 note, §103(e)(1)(B). |

| 17. |

15 U.S.C. §6701 note, §102(11). |

| 18. |

This $37.5 billion figure is the current one and has been increased over time from $10 billion at the beginning of the TRIA program. Beginning in 2020, this will be indexed according to the total of the insurer deductibles averaged over the previous three years. |

| 19. |

P.L. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376. |

| 20. |

§502 of P.L. 111-203, codified at 31 U.S.C. §313(c)(1)(D). |

| 21. |

Although the purchase of terrorism coverage is not required under federal law, the interaction of TRIA and state laws on workers' compensation insurance results in most businesses being required to purchase terrorism coverage in workers' compensation policies. |

| 22. |

There is some variance in the acronym used for such attacks. The U.S. Department of Defense, for example, uses "CBRN," rather than NCBR, in its Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms; see p. 34 at https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/dictionary.pdf. |

| 23. |

Insurers might have attempted to exclude the September 11, 2001, losses under existing war risk exclusions, but did not generally attempt to do so. |

| 24. |

See, for example, H.R. 2761 (110th Congress) as passed by the House on September 19, 2007, and H.Rept. 110-318, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CRPT-110hrpt318/pdf/CRPT-110hrpt318.pdf. |

| 25. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), TERRORISM INSURANCE: Status of Coverage Availability for Attacks Involving Nuclear, Biological, Chemical, or Radiological Weapons, GAO-09-39, December 12, 2008, at http://gao.gov/products/GAO-09-39. |

| 26. |

Department of the Treasury, "Guidance Concerning Stand-Alone Cyber Liability Insurance Policies Under the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program," 81 Federal Register 95313, December 27, 2016. |

| 27. |

Department of the Treasury, Federal Insurance Office (FIO), Report on the Effectiveness of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, June 2018, p. 55. |

| 28. |

Emmett J. Vaughan and Therese Vaughan, Fundamentals of Risk and Insurance (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003), p. 41. |

| 29. |

For more information on other countries' programs addressing terrorism risk, see GAO, Terrorism Risk Insurance: Comparison of Selected Programs in the United States and Foreign Countries, GAO-16-316, April 12, 2016, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-316. |

| 30. |

Extremus Versicherungs AG, "Neue Bedingungen, Staatsgarantie verlängert," at https://www.extremus.de/index.php/aktuelles/news. |

| 31. |

For a discussion of the approach in Canada, see the following from the Canadian law firm McMillan: Lyon, Carol, "Does Canada Need a Terrorism Risk Insurance Scheme?" McMillan Insurance Bulletin, December 2015, at https://mcmillan.ca/Does-Canada-need-a-terrorism-risk-insurance-scheme. |

| 32. |

For more information, see "Aviation Insurance Program," at https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ash/ash_programs/aviation_insurance/. |

| 33. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44593, Introduction to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), by Diane P. Horn and Baird Webel. |

| 34. |

P.L. 90-448; 82 Stat. 476. The act also created state Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans and a Federal Crime Insurance Program. |

| 35. |

Jeff Woodward, "The ISO Terrorism Exclusions: Background and Analysis," IRMI Insights, February 2002, at http://www.irmi.com/expert/articles/2002/woodward02.aspx. |

| 36. |

The Real Estate Roundtable, "Terror Insurance Drag on Real Estate Still Climbing," Roundtable Weekly, September 19, 2003. |

| 37. |

"Moody's Downgrades Securities on Lack of Terrorism Insurance," Wall Street Journal, September 30, 2002, p. C14. |

| 38. |

Smith, Ray A., "Office-Building Demand Rises Despite Vacancies," Wall Street Journal, July 24, 2002, p. B6. |

| 39. |

Congressional Budget Office, Federal Terrorism Reinsurance: An Update, January 2005, pp. 10-11, at http://www.cbo.gov/publication/16210. |

| 40. |

Although there is no requirement in federal law to purchase terrorism coverage, businesses may be required by state law to purchase the coverage. This is particularly the case in workers' compensation insurance. Market forces, such as requirements for commercial loans, may also compel businesses to purchase terrorism coverage. |

| 41. |

Marsh, Inc., 2018 Terrorism Risk Insurance Report, April 2018, p. 1. |

| 42. |

FIO, Report on the Effectiveness of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, June 2018, p. 30. |

| 43. |

President's Working Group on Financial Markets, The Long-Term Availability and Affordability of Insurance for Terrorism Risk, April 2014, p. 26. |

| 44. |

Marsh, Inc., The Marsh Report: Terrorism Risk Insurance 2010, p. 14. |

| 45. |

Marsh, Inc., 2013 Terrorism Risk Insurance Report, May 2013, p. 12. |

| 46. |

FIO, Report on the Effectiveness of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, June 2018, p. 20. |

| 47. |

FIO, Report on the Effectiveness of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Program, June 2018, pp. 72-74. Calculations by CRS. |

| 48. |

AM Best, Best's Aggregates & Averages, Property-Casualty, 2002 Edition, p. 2; and AM Best, Best's Aggregates & Averages, Property-Casualty, 2018 Edition, p. 2. Inflation adjustment from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' CPI inflation calculator at https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. Actual 2002 figure is $293.5 billion. |

| 49. |

For more detailed TRIA scenarios, including different loss distribution assumptions, see CBO, Federal Reinsurance for Terrorism Risk in 2015 and Beyond: Working Paper 2015-04, June 10, 2015, pp. 11-14, at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50171. |