Child Nutrition Programs: Current Issues

The term child nutrition programs refers to several U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) programs that provide food for children in institutional settings. These include the school meals programs—the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program—as well as the Child and Adult Care Food Program, Summer Food Service Program, Special Milk Program, and Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program.

The most recent child nutrition reauthorization, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA; P.L. 111-296), made a number of changes to the child nutrition programs. In some cases, these changes spurred debate during the law’s implementation, particularly in regard to updated nutrition standards for school meals and snacks. On September 30, 2015, some of the authorities created by the HHFKA expired. Efforts to reauthorize the child nutrition programs in the 114th Congress, while not completed, considered several related issues and prompted further discussion about the programs. There were no substantial reauthorization attempts in the 115th Congress.

Current issues discussed in this report include the following:

Nutrition standards for school meals and snacks. The HHFKA required USDA to update the nutrition standards for school meals and other foods sold in schools. USDA issued final rules on these standards in 2012 and 2016, respectively. Some schools had difficulty implementing the nutrition standards, and USDA and Congress have taken actions to change certain parts of the standards related to whole grains, sodium, and milk.

Offerings in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP). There have been debates recently over whether the FFVP should include processed and preserved fruits and vegetables, including canned, dried, and frozen items. Currently, statute permits only fresh offerings.

“Buy American” requirements for school meals. The school meals programs’ authorizing laws require schools to source foods domestically, with some exceptions, under Buy American requirements. Efforts both to tighten and loosen these requirements have been made in recent years. The enacted 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334) instructed USDA to “enforce full compliance” with the Buy American requirements and report to Congress within 180 days of enactment.

Congregate feeding in summer meals. Under current law, children must consume summer meals on-site. This is known as the “congregate feeding” requirement. Starting in 2010, Congress funded demonstration projects, including the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) demonstration, to test alternatives to congregate feeding in summer meals. Congress has increased funding for Summer EBT in recent appropriations cycles and there have been discussions about whether to continue or expand the program.

Implementation of the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). The HHFKA created CEP, an option for qualifying schools, groups of schools, and school districts to offer free meals to all students. Because income-based applications for school meals are no longer required in schools adopting CEP, its implementation has created data issues for federal and state programs relying on free and reduced-price lunch eligibility data.

Unpaid meal costs and “lunch shaming.” The issue of students not paying for meals and schools’ handling of these situations has received increasing attention. Some schools have adopted what some term as “lunch shaming” practices, including throwing away a student’s selected hot meal and providing a cold meal alternative when a student does not pay. Congress and USDA have taken actions recently to reduce instances of student nonpayment and stigmatization.

Paid lunch pricing. One result of new requirements in the HHFKA was price increases for paid (full price) lunches in many schools. Attempts have been made—some successfully—to loosen these “paid lunch equity” requirements in recent years.

Child Nutrition Programs: Current Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Current Issues

- Nutrition Standards for School Meals and Snacks

- Background

- Implementation and Changes

- Other Proposals

- "Fresh" in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP)

- "Buy American" in School Meals Programs

- Alternatives to Congregate Feeding in Summer Meals

- Summer EBT Demonstration

- Other Summer Demonstrations

- Other Proposals

- Community Eligibility Provision

- Unpaid Meal Costs and "Lunch Shaming"

- Paid Lunch and Other School Food Pricing

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The term child nutrition programs refers to several U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) programs that provide food for children in institutional settings. These include the school meals programs—the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program—as well as the Child and Adult Care Food Program, Summer Food Service Program, Special Milk Program, and Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program.

The most recent child nutrition reauthorization, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA; P.L. 111-296), made a number of changes to the child nutrition programs. In some cases, these changes spurred debate during the law's implementation, particularly in regard to updated nutrition standards for school meals and snacks. On September 30, 2015, some of the authorities created by the HHFKA expired. Efforts to reauthorize the child nutrition programs in the 114th Congress, while not completed, considered several related issues and prompted further discussion about the programs. There were no substantial reauthorization attempts in the 115th Congress.

Current issues discussed in this report include the following:

Nutrition standards for school meals and snacks. The HHFKA required USDA to update the nutrition standards for school meals and other foods sold in schools. USDA issued final rules on these standards in 2012 and 2016, respectively. Some schools had difficulty implementing the nutrition standards, and USDA and Congress have taken actions to change certain parts of the standards related to whole grains, sodium, and milk.

Offerings in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP). There have been debates recently over whether the FFVP should include processed and preserved fruits and vegetables, including canned, dried, and frozen items. Currently, statute permits only fresh offerings.

"Buy American" requirements for school meals. The school meals programs' authorizing laws require schools to source foods domestically, with some exceptions, under Buy American requirements. Efforts both to tighten and loosen these requirements have been made in recent years. The enacted 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334) instructed USDA to "enforce full compliance" with the Buy American requirements and report to Congress within 180 days of enactment.

Congregate feeding in summer meals. Under current law, children must consume summer meals on-site. This is known as the "congregate feeding" requirement. Starting in 2010, Congress funded demonstration projects, including the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) demonstration, to test alternatives to congregate feeding in summer meals. Congress has increased funding for Summer EBT in recent appropriations cycles and there have been discussions about whether to continue or expand the program.

Implementation of the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). The HHFKA created CEP, an option for qualifying schools, groups of schools, and school districts to offer free meals to all students. Because income-based applications for school meals are no longer required in schools adopting CEP, its implementation has created data issues for federal and state programs relying on free and reduced-price lunch eligibility data.

Unpaid meal costs and "lunch shaming." The issue of students not paying for meals and schools' handling of these situations has received increasing attention. Some schools have adopted what some term as "lunch shaming" practices, including throwing away a student's selected hot meal and providing a cold meal alternative when a student does not pay. Congress and USDA have taken actions recently to reduce instances of student nonpayment and stigmatization.

Paid lunch pricing. One result of new requirements in the HHFKA was price increases for paid (full price) lunches in many schools. Attempts have been made—some successfully—to loosen these "paid lunch equity" requirements in recent years.

Introduction

The term child nutrition programs refers to several U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) programs that provide food to children in institutional settings. The largest are the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP), which subsidize free, reduced-price, and full-price meals in participating schools.1 Also operating in schools, the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program provides funding for fruit and vegetable snacks in participating elementary schools, and the Special Milk Program provides support for milk in schools that do not participate in NSLP or SBP. Other child nutrition programs include the Child and Adult Care Food Program, which provides meals and snacks in child care and after-school settings, and the Summer Food Service Program, which provides food during the summer months.2

The child nutrition programs were last reauthorized by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA, P.L. 111-296). On September 30, 2015, some of the authorities created or extended by the HHFKA expired. However, these expirations had a minimal impact on program operations, as the child nutrition programs have continued with funding provided by annual appropriations acts.3

In the 114th Congress, lawmakers began but did not complete child nutrition reauthorization, which refers to the process of reauthorizing and potentially making changes to multiple permanent statutes—the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, the Child Nutrition Act, and sometimes Section 32 of the Act of August 24, 1935. Both committees of jurisdiction—the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry and the House Committee on Education and the Workforce—reported reauthorization legislation (S. 3136 and H.R. 5003, respectively). This legislation died at the end of the 114th Congress, as is the case for any bill that has not yet passed both chambers and been sent to the President at the end of a Congress. There were no significant child nutrition reauthorization efforts in the 115th Congress; however, 2018 farm bill proposals and the final enacted bill included a few provisions related to child nutrition programs.

The implementation of the HHFKA, child nutrition reauthorization efforts in the 114th Congress, and the child nutrition-related topics raised during 2018 farm bill negotiations have raised issues that may be relevant for Congress in future reauthorization efforts or other policymaking opportunities. These issues often relate to the content and type of foods served in schools: for example, the nutritional quality of foods and whether foods are domestically sourced. Other issues relate to access, including alternatives to on-site consumption in summer meals and implementation of the Community Eligibility Provision, an option to provide free meals to all students in certain schools. Stakeholders in these issues commonly include school food authorities (SFAs; school food service departments that generally operate at the school district level), hunger and nutrition-focused advocacy organizations, and food industry organizations, among others.

This report provides an overview of these and other current issues in the child nutrition programs. It does not cover every issue, but rather provides a high-level review of some recent issues raised by Congress and/or program stakeholders, drawing examples from legislative proposals in the 114th and 115th Congresses. References to CRS reports with more detailed information or analysis on specific issues are provided where applicable, including the following:

- For an overview of the structure and functions of the child nutrition programs, see CRS Report R43783, School Meals Programs and Other USDA Child Nutrition Programs: A Primer.

- For more information on the child nutrition reauthorization proposals in the 114th Congress, see CRS Report R44373, Tracking the Next Child Nutrition Reauthorization: An Overview.

- For a summary of the HHFKA, see CRS Report R41354, Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization: P.L. 111-296.

|

Program |

Authorizing Statutes |

Regulations |

|

National School Lunch Program (NSLP) |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1751 et seq.) |

7 C.F.R. 210 et seq. |

|

School Breakfast Program (SBP) |

Child Nutrition Act, Section 4 (42 U.S.C. 1773) |

7 C.F.R. 220 et seq. |

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 17 (42 U.S.C. 1766) |

7 C.F.R. 226 et seq. |

|

Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 13 (42 U.S.C. 1761) |

7 C.F.R. 225 et seq. |

|

Special Milk Program (SMP) |

Child Nutrition Act, Section 3 (42 U.S.C. 1772) |

7 C.F.R. 215 et seq. |

|

Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP) |

Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 19 (42 U.S.C. 1769a) |

n/aa |

Current Issues

Nutrition Standards for School Meals and Snacks

Background

School meals must meet certain requirements to be eligible for federal reimbursement, including nutritional requirements. These nutrition standards were last updated following the enactment of the HHFKA, which required USDA to update the standards for school meals and create new nutrition standards for "competitive" foods (e.g., foods sold in vending machines, a la carte lines, and snack bars) within a specified timeframe.4 Specifically, the law required USDA to issue proposed regulations for competitive foods nutrition standards within one year after enactment and for school meals nutrition standards within 18 months after enactment. The law also provided increased federal subsidies (6 cents per lunch) for schools meeting the new requirements and funding for technical assistance. The nutrition standards in the HHFKA were championed by a variety of organizations and stakeholders, including nutrition and public health advocacy organizations, food and beverage companies, school nutrition officials, retired military leaders, and then-First Lady Michelle Obama.5

The precise nutritional requirements were largely written in the subsequent regulations, not the HHFKA. USDA-FNS published the final rule for school meals in January 2012 and the final rule for competitive foods in July 2016.6 As required by law, the nutrition standards were based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (now the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies).7 For school meals, the updated standards increased the amount of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains in school lunches and breakfasts.8 They also instituted limits on calories, sodium, whole grains, and proteins in meals and restricted milk to low-fat (unflavored) and fat-free (flavored or unflavored) varieties. Other requirements included a provision that senior high school students must select a half-serving of fruits or vegetables with a reimbursable meal. Similarly, the nutrition standards for competitive foods limited calories, sodium, and fat in foods sold outside of meals, among other requirements.9 The standards applied only to non-meal foods and beverages sold during the school day (defined as midnight until 30 minutes after dismissal) and include some exceptions for fundraisers.

Implementation and Changes

The meal standards began phasing in during school year (SY) 2012-2013, and the competitive foods standards took effect in SY2014-2015.10 However, sodium limits and certain whole grain requirements for school meals were scheduled to phase in over multiple school years.11 Some schools experienced challenges implementing the changes, reporting difficulty obtaining whole grain and low-sodium products, issues with student acceptance of foods, reduced participation, increased costs, and increased food waste. These accounts were shared in news stories and by the School Nutrition Association (SNA), a national, nonprofit professional and advocacy organization representing school nutrition professionals.12 Studies by the U.S. Government Accountability Office and USDA confirmed that many of these issues were present in SY2012-2013 and SY2013-2014, the first two years of implementation.13 SNA advocated for certain changes to the standards, while other groups called for maintaining the standards, arguing that they were necessary for children's health and that implementation challenges were easing with time.14

In January 2014, USDA removed weekly limits on grains and protein.15 Then, in the FY2015, FY2016, and FY2017 appropriations laws, Congress enacted provisions that loosened the milk, whole grain, and/or sodium requirements from SY2015-2016 through SY2017-2018.16 USDA implemented similar changes for SY2018-2019 in an interim final rule.17 In December 2018, USDA published a final rule that indefinitely changes these three aspects of the standards starting in SY2019-2020.18 Specifically, the rule

- allows all SFAs to offer flavored, low-fat (1%) milk as part of school meals and as beverages sold in schools,19 and requires unflavored milk to be offered alongside flavored milk in school meals;

- requires SFAs to adhere to a 50% whole grain-rich requirement (the original regulations required 100% whole grain-rich starting in SY2014-2015);20 states may make exemptions to allow SFAs to offer nonwhole grain-rich products; and

- maintains Target 1 sodium limits from SY2019-2020 through SY2023-2024, implements Target 2 limits starting in SY2024-2025 and thereafter, and eliminates Target 3 limits (the strictest target).21

Table 2 provides a timeline from the 2012 final rule to the 2018 final rule, showing the ways in which milk, whole grain, and sodium requirements have been modified over time. Apart from these changes, the nutrition standards for school meals remain largely intact. The changes to the milk requirements also affect other beverages sold in schools; otherwise, the nutrition standards for competitive foods have not been changed substantially.

Table 2. Legislative and Regulatory Changes to the Milk, Whole Grain, and Sodium Requirements for School Meals (2012-2018)

|

Policy Provision |

Milk |

Whole Grains |

Sodium |

|||

|

USDA-FNS January 2012 final rulea |

Required flavored milk to be fat-free and unflavored milk to be low-fat (1%) or fat-free by SY2012-2013. |

Required 50% of grains to be whole-grain rich by SY2012-2013 for lunches and by SY2013-2014 for breakfasts; required 100% whole grain-rich by SY2014-2015. |

Created maximum weekly levels of sodium for breakfasts and lunches based on a student's grade level. Scheduled Target 1 limits for SY2014-2015, Target 2 limits for SY2017-2018, and Target 3 limits for SY2022-2023. |

|||

|

FY2015 appropriation (§§751 and 752 of P.L. 113-235) |

n/a |

Required USDA to allow states to exempt SFAs demonstrating hardship from the 100% whole grain requirement from December 2014 through SY2015-2016. Exempted SFAs must comply with the 50% requirement. |

Postponed reductions in sodium below Target 1 indefinitely ("until the latest scientific research establishes the reduction is beneficial for children"). |

|||

|

FY2016 appropriation (§733 of P.L. 114-113) |

n/a |

Extended exemptions through SY2016-2017. |

Same language as FY2015. |

|||

|

FY2017 appropriation (§747 of P.L. 115-31) |

Required USDA to allow states to grant hardship-based exemptions to SFAs to offer flavored low-fat (1%) milk from May 2017 through SY2017-2018. |

Extended exemptions through SY2017-2018. |

Retained Target 1 through SY2017-2018. |

|||

|

USDA-FNS November 2017 interim final ruleb |

Allowed all SFAs to offer flavored low-fat (1%) milk in SY2018-2019. |

Extended exemptions through SY2018-2019. |

Retained Target 1 through SY2018-2019. |

|||

|

USDA-FNS December 2018 final rulec |

Allows all SFAs to offer flavored low-fat (1%) milk in SY2019-2020 and thereafter. |

Institutes 50% whole grain requirement for all SFAs starting in SY2019-2020 and thereafter. Allows states to grant exemptions to SFAs to offer grains that are not whole-grain rich. |

Retains Target 1 in SY2019-2020 through SY2023-2024, implements Target 2 starting in SY2024-2025 and thereafter, and eliminates Target 3. |

Notes: n/a indicates that the law did not include pertinent content. The FY2017 appropriation was enacted shortly after the November 2017 interim final rule but is presented before it in this table because of the school years that each policy affected. Not shown are (1) the FY2012 appropriations act, which retained Target 1 indefinitely and prohibited the establishment of any whole grain requirements that did not define "whole grain," and (2) USDA guidance and regulations that lifted weekly maximums on whole grains starting in 2012.

a. USDA-FNS, "Nutrition Standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs," 77 Federal Register 17, January 26, 2012, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/01/26/2012-1010/nutrition-standards-in-the-national-school-lunch-and-school-breakfast-programs.

b. USDA-FNS, "Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements; Interim Final Rule," 82 Federal Register 56703, November 30, 2017, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/11/30/2017-25799/child-nutrition-programs-flexibilities-for-milk-whole-grains-and-sodium-requirements.

c. USDA-FNS, "Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements: Final Rule," 83 Federal Register 63775, December 12, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/12/12/2018-26762/child-nutrition-programs-flexibilities-for-milk-whole-grains-and-sodium-requirements.

Other Proposals

Legislative proposals related to the nutrition standards were considered in the 115th Congress. For example, the House-passed version of 2018 farm bill (one version of H.R. 2) would have required USDA to review and revise the nutrition standards for school meals and competitive foods. According to the bill, the revisions would have had to ensure that the standards, particularly those related to milk, "(1) are based on research based on school-age children; (2) do not add costs in addition to the reimbursements required to carry out the school lunch program … and (3) maintain healthy meals for students."22 This provision was not included in the enacted bill.

Child nutrition reauthorization proposals in the House and Senate during the 114th Congress also would have altered the nutrition standards. The House committee's proposal (H.R. 5003) would have required USDA to review the school meal standards at least once every three years and revise them as necessary, following certain criteria.23 In addition, under the proposal, fundraisers by student groups/organizations would no longer have had to meet the competitive food standards and any foods served as part of a federally reimbursable meal would have been allowed to be sold a la carte.24 The Senate committee's proposal (S. 3136) would have required USDA to revise the whole grain and sodium requirements for school meals within 90 days after enactment. Although not included in the proposal itself, negotiations between the Senate committee, the White House, USDA, and the School Nutrition Association resulted in an agreement that these revisions, if enacted, would have reduced the 100% whole grain-rich requirement to 80% and delayed the Target 2 sodium requirement for two years.25

"Fresh" in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP)

Under current law, fruit and vegetable snacks served in FFVP must be fresh.26 According to USDA guidance, fresh refers to foods "in their natural state and without additives."27 In recent years, some have advocated for the inclusion of frozen, dried, canned, and other types of fruits and vegetables in the program, while others have advocated for continuing to maintain only fresh products.28 Stakeholders on both sides include agricultural producers and processors.

The 2014 farm bill (Section 4214 of P.L. 113-79) funded a pilot project that incorporated canned, dried, and frozen (CDF) fruits and vegetables in FFVP in a limited number of states. USDA selected schools in four states (Alaska, Delaware, Kansas, and Maine) that reported difficulty obtaining, storing, and/or preparing fresh fruits and vegetables. According to the final (2017) evaluation, 56% of the pilot schools chose to incorporate CDF fruits and vegetables during an average week of the demonstration.29 Schools most often introduced dried and canned fruits, which resulted in decreased vegetable offerings and increased fruit offerings in the FFVP. However, there was no significant impact on students' vegetable consumption, while fruit consumption declined on FFVP snack days (likely because students consumed a smaller quantity of fruit when it was dried or canned). There was also no significant impact on student participation. Student satisfaction with FFVP decreased slightly during the pilot, parents' responses to the pilot were mixed, and school administrators (who opted into the pilot) generally favored the changes.

Legislative proposals to change FFVP offerings on a more permanent basis have also been considered. For example, in the 115th Congress, the House version of H.R. 2 would have allowed CDF and puréed forms of fruits and vegetables in FFVP and removed "fresh" from the program name. This provision was not included in the enacted bill. In the 114th Congress, child nutrition reauthorization legislation in the House (H.R. 5003) included a similar proposal to allow participating schools to serve "all forms" of fruits and vegetables as well as tree nuts. The Senate committee's proposal (S. 3136) would have provided temporary hardship exemptions for schools with limited storage and preparation facilities or limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables that would have allowed them to serve CDF fruits and vegetables in FFVP. Such schools would have to transition to 100% fresh products over time.

"Buy American" in School Meals Programs

Schools participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and/or School Breakfast Program (SBP) must comply with federal requirements related to sourcing foods domestically. These requirements are outlined in the school meals programs' authorizing laws and clarified in USDA guidance.

Under the Buy American requirements, schools participating in the NSLP and/or SBP in the 48 contiguous states must purchase "domestic commodities or products … to the maximum extent practicable."30 Statute defines "domestic commodities or products" as those that are both produced and processed substantially in the United States. Accompanying conference report language elaborated that "processed substantially" means the product is processed in the United States and contains over 51% domestically grown ingredients, and this definition is also included in USDA guidance (discussed below).31 USDA regulations essentially restate the statutory requirement.32

USDA has issued guidance on how SFAs and state agencies should implement the Buy American requirements. The most recent guidance (as of the date of this report) was published in a June 2017 memorandum.33 According to USDA-FNS guidance, the Buy American requirements apply to any foods purchased with funds from the nonprofit school food service account, whether or not they are federal funds (children's paid lunch fees, for example, also go into the nonprofit school food service account).34 The guidance encourages SFAs to integrate Buy American into their procurement processes; for example, by monitoring the USDA catalog for appropriate products and placing Buy American language in solicitations, contracts, and other procurement documents. The guidance explains that SFAs are permitted to make exceptions to the Buy American requirements on a limited basis when a product "is not produced or manufactured in the U.S. in sufficient and reasonably available quantities of a satisfactory quality" or when "competitive bids reveal the costs of a U.S. product are significantly higher than the non-domestic product."35 SFAs must interpret when this is the case and document any exceptions they make. SFAs may also request a waiver from the requirements for a product that does not meet these criteria. State agencies must review SFAs' compliance with the Buy American requirements, including any exceptions an SFA has made, and take corrective action when necessary.

The enacted 2018 farm bill (Section 4207 of P.L. 115-334) included a provision requiring USDA to "enforce full compliance" with the Buy American requirements and "ensure that States and school food authorities fully understand their responsibilities" within 180 days of enactment. In addition, the bill requires USDA to submit a report to Congress by the 180-day deadline on actions taken and plans to comply with the provision. The provision clarifies the definition of domestic products for the purposes of USDA's enforcement, stating that domestic products are those that are "processed in the United States and substantially contain … meats, vegetables, fruits, and other agricultural commodities" produced in the United States, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, or any territory or possession of the United States, or "fish harvested" in the Exclusive Economic Zone or by a U.S.-flagged vessel. The provision in the enacted bill amended a related provision in the Senate-passed version of the farm bill.36

Proponents of stricter requirements have cited economic and food safety reasons for domestic sourcing and expressed particular concern over sourcing from China.37 Others have argued for maintaining or increasing schools' discretion in food procurement, arguing that high-quality domestic options are not always available or cost-effective.38

Alternatives to Congregate Feeding in Summer Meals

Under current law, summer meals are generally provided in "congregate" or group settings where children come to eat while supervised. These meals are provided through the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) and the National School Lunch Program's Summer Seamless Option (SSO).39 In recent years, policymakers have weighed different proposals and tested alternatives to congregate meals in SFSP and SSO. Some of these alternatives focus on rural areas, which may face particular barriers to onsite consumption of summer meals. According to a May 2018 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, states commonly reported that reaching children in rural areas was "very" or "extremely" challenging in SFSP.40

Summer EBT Demonstration

The 2010 Agriculture Appropriations Act (Section 749(g) of P.L. 111-80) provided $85 million in discretionary funding for "demonstration projects to develop and test methods of providing access to food for children in urban and rural areas during the summer months." One of these is the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC or Summer EBT) project, which began in summer 2011 and has continued each summer since (as of the date of this report) in a limited number of states and Indian Tribal Organizations.41 The project provides electronic food benefits to households with children eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. Depending on the site and year, either $30 or $60 per month is provided on an electronic benefits transfer (EBT) card for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Participants in jurisdictions providing benefits through SNAP can redeem benefits for SNAP-eligible foods at any SNAP-authorized retailer, while participants in the WIC EBT jurisdictions are limited to the smaller set of WIC-eligible foods at WIC-authorized retailers.42

An evaluation of Summer EBT was conducted from FY2011 through FY2013.43 The study, which used a random assignment design, found a significant decline in the prevalence of very low food security among participants (9.5% of control group children experienced very low food security compared to 6.4% in the Summer EBT group).44 It also showed improvements in children's consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Both the WIC and SNAP models showed increased consumption, but increases were greater at sites operating the WIC model.45

Congress has provided subsequent funding for Summer EBT projects (see Table 3). Most recently, the third FY2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-6) provided $28 million for the Summer EBT demonstration. Awardees for summer 2017 were Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, Oregon, Virginia, and the Chickasaw and Cherokee nations.46 For summer 2018, USDA also awarded grants to Tennessee and Texas.47 Many of these jurisdictions participated in Summer EBT in previous summers as well. In October 2018, USDA-FNS announced a new strategy for determining grant recipients in FY2019, stating that the agency will prioritize new states that have not participated before, statewide projects, and projects that can operate in the summers of 2019 through 2021.48

There were proposals in the 114th and 115th Congresses to expand Summer EBT. For example, the Senate committee's child nutrition reauthorization proposal in the 114th Congress (S. 3136) would have allowed a portion of SFSP's mandatory funding to cover Summer EBT and authorized up to $50 million in discretionary funding for the program. In addition, in its FY2017 budget proposal, the Obama Administration recommended expansion of Summer EBT nationwide with a phase-in over 10 years.49 Freestanding bills in the 114th and 115th Congresses had similar objectives.50

|

Demonstration Type |

Fiscal |

Appropriation |

|

All summer demonstration projects |

FY2010 |

85.0 (available until expended) |

|

FY2011 |

n/a |

|

|

FY2012 |

n/a |

|

|

FY2013 |

n/a |

|

|

FY2014 |

n/a |

|

|

Summer EBT only |

FY2015 |

16.0 |

|

FY2016 |

23.0 |

|

|

FY2017 |

23.0 |

|

|

FY2018 |

28.0 |

|

|

FY2019 |

28.0 |

Source: Enacted appropriations laws for FY2010-FY2019.

Notes: Appropriations for the summer demonstration projects are generally contained in the "Child Nutrition Programs" section of enacted appropriations acts. However, the FY2016 appropriations act included $7 million for these projects in a general provision (§741).

Other Summer Demonstrations

Funding from the 2010 Agriculture Appropriations Act (Section 749(g) of P.L. 111-80) was also used for other demonstration projects. One of these, the Enhanced Summer Food Service Program (eSFSP), took place during the summers of 2010 through 2012 in eight states.51 It included four initiatives: (1) incentives for SFSP sites to lengthen operations to 40 or more days, (2) funding to add recreational or educational activities at meal sites, (3) meal delivery for children in rural areas, and (4) food backpacks that children could take home on weekends and holidays.

Evaluations of eSFSP were published from 2011 to 2014. Summer meal participation rates rose during the demonstration periods for all four initiatives.52 In addition, children in the meal delivery and backpack demonstrations had consistent rates of food insecurity from summer to fall (this was not measured for the other initiatives).53 However, the results from these evaluations should be interpreted with caution due to a small sample size, the lack of a comparison group, and potential confounding factors.54

Another demonstration project, also operating under authority provided by the 2010 Agriculture Appropriations Act, provided exemptions from the congregate feeding requirement to SFSP and SSO outdoor meal sites experiencing excessive heat each summer since 2015 (as of the date of this report).55 Exempted sites must continue to serve children in congregate settings on days when heat is not excessive, and provide meals in another form (e.g., a take-home form) on days of excessive heat. USDA also offers exemptions on a case-by-case basis for other extreme weather conditions. This demonstration has not been evaluated.

Other Proposals

There were other proposals and hearings related to congregate feeding in SFSP in recent years.56 For example, in the 114th Congress, committee-reported child nutrition reauthorization proposals in the Senate and the House (S. 3136 and H.R. 5003, respectively) would have enabled some rural meal sites to provide SFSP meals for consumption offsite. Specifically, both proposals would have allowed offsite consumption for children (1) in rural areas (H.R. 5003 to a more limited extent than S. 3136) and (2) in nonrural areas in which more than 80% of students are certified as eligible for free or reduced-price meals. The bills would have also permitted congregate feeding sites to provide meals to be consumed offsite episodically under certain conditions such as extreme weather or public safety concerns.

Community Eligibility Provision

The HHFKA created the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), an option to provide free meals (lunches and breakfasts) to all students in schools with high proportions of students who automatically qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.57 CEP became available to schools nationwide starting in SY2014-2015, and participation has increased since then. As of SY2016-2017, more than 20,700 schools participated in CEP, according to data from the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a nonprofit advocacy organization.58 This is roughly 22% of NSLP schools.59

Several groups have expressed support for CEP during its implementation, arguing that the provision improves access to meals, reduces stigma associated with receiving free or reduced-price meals, and reduces schools' administrative costs.60 Others have sought to change the option. For example, in the 114th Congress, the House's committee-reported child nutrition reauthorization bill (H.R. 5003) would have restricted schools' eligibility for CEP, which the committee majority argued was "to better target resources to those students in need, while also ensuring all students who are eligible for assistance continue to receive assistance."61

One secondary effect of CEP is that it has created data issues for other nonnutrition federal and state programs.62 Many programs, most notably the federal Title I-A program (the primary source of federal funding for elementary and secondary schools), use free and reduced-price lunch data to determine eligibility and/or funding allocations. These data come from school meal applications, which are no longer collected under CEP's automatic eligibility determination process. For more information on this issue, see CRS Report R44568, Overview of ESEA Title I-A and the School Meals' Community Eligibility Provision.63

Unpaid Meal Costs and "Lunch Shaming"

Students may qualify for free meals, or they may have to pay for reduced-price or full-price meals.64 In recent years, the issue of students owing and not paying their meal costs, and schools' responses to such situations, has received increased attention. In many cases, schools serve students a regular meal, charging the unpaid meal cost and creating a debt that they may try to collect later from the family. In other cases, schools respond with what some have called "lunch shaming" practices—most commonly, taking or throwing away a student's selected hot foods and providing an alternative cold meal or, less commonly, barring children from participation in school events until debt is repaid or having children wear a visual indicator of meal debt (e.g., a stamp or sticker). Lunch shaming instances have largely been reported in news articles from different states, and there are limited national data available on the prevalence of such practices (available data are discussed in the text box below).65

Many school districts report that unpaid meal costs create a financial burden on their meal programs (see text box below for more detail).66 In addition to federal funds, student payments for full and reduced-price meals are a primary source of revenue for school food programs. Schools have an interest in collecting this revenue to help fund operations.67 Also, according to federal regulations, if schools are unable to recover unpaid meal funds, the money becomes "bad debt" and the school or school district must use other nonfederal funding sources to cover the costs.68

Starting in 2010, Congress and USDA have taken actions to address the issue of unpaid meal costs. Section 143 of the HHFKA required USDA to examine states' and school districts' policies and practices regarding unpaid meal charges. As part of the review, the law required USDA to "prepare a report on the feasibility of establishing national standards for meal charges and the provision of alternate meals" and, if applicable, make recommendations related to the implementation of the standards. The law also permitted USDA to take follow-up actions based on the findings from the report.69

USDA's subsequent Report to Congress in June 2016 ultimately did not recommend national standards, but instead recommended "clarifying and updating policy guidance on specific national policies impacting unpaid meal charges and facilitating the development and distribution of best practices to support decision making by States and localities."70 USDA-FNS followed up with a memorandum requiring SFAs to institute and communicate, by July 1, 2017, a written meal charge policy, which was to include instructions on how to address situations in which a child does not pay for a meal.71 USDA-FNS also provided clarification through webinars, other memoranda, and a best practice guide.72

In the Report to Congress, USDA stated that its recommendation was based on findings from a study published by USDA-FNS in March 2014 and a Request for Information (RFI) on "Unpaid Meal Charges" published by USDA-FNS in October 2014.73 The findings from both the study and the RFI—which garnered 462 comments—showed that meal charge policies were largely determined at the school and school district levels rather than the state level. The responses to the RFI also indicated that such policies ranged in formality, with varying degrees of review (e.g., some required school board approval while others did not) and enforcement. In the RFI comments, school and district officials generally expressed a preference for local control of meal charge policies, while national advocacy groups generally favored national standards.

|

Data on Unpaid Meal Costs and "Lunch Shaming" There are limited national data available on the prevalence of "lunch shaming" practices. However, there are data on unpaid meal costs and schools' reported responses to these costs. For example, USDA-FNS's study published in March 2014 examined the policies and practices of a nationally representative sample of SFAs in SY2011-2012. That study found that 58% of SFAs reported incurring unpaid meal charges prior to recovery attempts.74 Of these SFAs, 50.4% served the equivalent of a reimbursable meal to students unable to pay, 38.0% served an alternative meal (e.g., a cold meal), 5.4% combined these approaches, 4.9% did something else, and 1.3% did not serve a meal.75 On average, SFAs recovered 31% of lost revenues from unpaid meals. USDA-FNS's RFI published in October 2014 also shed light on schools' and school districts' perspectives and policies regarding unpaid meal charges.76 According to USDA's analysis of the comments, many school and district officials said that they allowed a certain number of charges before providing an alternative meal or cutting students off from meals.77 The most common reported alternative meal was a cheese or peanut butter and jelly sandwich, a fruit or vegetable, and unflavored milk. Generally, school districts' policies were more lenient for elementary school students and stricter for middle and high school students. Many officials reported that unpaid meal charges were a financial burden on their school food service account, both in terms of lost revenue and the costs associated with collecting debt from families. |

The topics of lunch shaming and unpaid meal costs also surfaced in the 115th Congress. For example, a provision in the FY2018 appropriations law stated that funds appropriated in the law could not be used in ways that result in discrimination against children eligible for free or reduced-price meals, including the practices of segregating children and overtly identifying children by special tokens or tickets (note that this does not pertain to children paying for full-price meals).78 Legislative proposals in the 115th Congress included the Anti-Lunch Shaming Act of 2017 (H.R. 2401/S. 1064), which sought to establish national standards for how schools treat children unable to pay for a meal.79

Unpaid meal costs and lunch shaming have also been active topics at the state level. In recent years, a number of states have enacted legislation aimed at addressing these issues.80 For example, in 2018, Illinois passed legislation that requires schools to serve a regular (reimbursable) meal to students who do not pay and allows school districts to request an offset from the state for debts exceeding $500.81

Paid Lunch and Other School Food Pricing

The HHFKA created new requirements related to schools' pricing of paid lunches (sometimes referred to as "paid lunch equity" requirements).82 Specifically, the law required all NSLP-participating SFAs to review their average price of paid lunches and, if necessary, gradually increase prices based on a formula.83 The law also gave SFAs the option to meet the requirements with specified nonfederal funding sources instead of raising prices.84

According to the Senate committee report on the HHFKA, the requirements were intended "to ensure that children receiving free and reduced price lunches receive the full value of federal funds."85 Prior to the paid lunch equity requirements, a USDA study found that federal subsidies for free and reduced-price lunches were cross-subsidizing other aspects of the meals programs, likely including paid lunches.86 This can occur because federal reimbursements for free, reduced-price, and paid lunches are all mixed into the same SFA-run "nonprofit school food service account" (NSFSA).87 Some observers argue, however, that raising prices may reduce participation in paid lunches.88

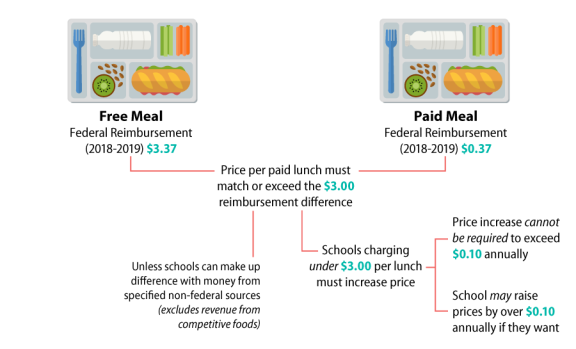

Under the paid lunch equity formula, the price per paid lunch must eventually match or exceed the difference between the federal reimbursements for free and paid lunches. If this is not the case, schools must increase prices over time until they make up the difference. For example, the federal reimbursement was $3.37 for free lunches and $0.37 for paid lunches SY2018-2019 for some schools.89 Under the requirements, if schools were not charging at least $3.00 per paid lunch, they would be required to increase the price of a paid lunch gradually, based on a formula, until they closed the gap (see Figure 1). Schools cannot be required to raise the price by more than 10 cents annually, but they may choose to do so.

|

Figure 1. Paid Lunch Equity Formula An Example of Schools' Pricing of Paid Lunches Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 Using SY2018-2019 Reimbursement Rates |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Section 205 of P.L. 111-296. Notes: If schools are charging under the reimbursement difference (based on their average price of a paid lunch in October of the previous school year), they must increase the price of paid lunches by at least 2% plus the percentage change in food inflation. Schools may round down to the nearest $0.05. |

The HHFKA also included related requirements for revenue from "nonprogram" (i.e., competitive) foods.90 The law required that any revenue from nonprogram foods accrue to the SFA-run NSFSA. In practice, this prevents revenue from competitive foods from being used for other school purposes outside of food service. The law also required that, broadly speaking, revenue from nonprogram foods equal or exceed the costs of obtaining nonprogram foods (see the regulations for a specific formula).91

In June 2011, USDA-FNS published an interim final rule implementing the requirements starting in SY2011-2012, offering some flexibility for that first year.92 USDA subsequently provided certain exemptions through agency guidance for SY2013-2014 through SY2017-2018 for SFAs "in strong financial standing," as determined by state agencies based on different criteria.93 For SY2018-2019, the enacted FY2018 appropriation (Section 775 of P.L. 115-141) expanded the exemptions, requiring only SFAs with a negative balance in the NSFSA as of January 31, 2018, potentially to have to raise prices for paid meals.94

Other legislative proposals related to the paid lunch equity requirements were considered in recent Congresses. For example, the House committee's child nutrition reauthorization proposal in the 114th Congress would have eliminated the requirements.95 The Senate committee's proposal would have replaced the requirements with a broader "non-federal revenue target," which could have come from household payments for full-price lunches or other state and local contributions.96

Appendix. Acronyms Used in This Report

CACFP: Child and Adult Care Food Program

CDF: Canned, dried, or frozen

CEP: Community Eligibility Provision

eSFSP: Enhanced Summer Food Service Program

FFVP: Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program

HHFKA: Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act

NSFSA: Nonprofit school food service account

NSLP: National School Lunch Program

SBP: School Breakfast Program

SFA: School food authority

SFSP: Summer Food Service Program

SMP: Special Milk Program

SSO: Summer Seamless Option

Summer EBT or SEBTC: Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children

SY: school year

USDA-FNS: U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Randy Alison Aussenberg, CRS Specialist in Nutrition Assistance Policy; Katie Jones, CRS Analyst in Housing Policy; and Alyse Minter, CRS Research Librarian, assisted with this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

These three meal categories are subsidized by the federal government in increasing amounts. For the reimbursement rates for school year (SY) 2018-2019, see USDA-FNS, "National School Lunch, Special Milk, and School Breakfast Programs, National Average Payments/Maximum Reimbursement Rates," 83 Federal Register 34105, July, 19, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/07/19/2018-15465/national-school-lunch-special-milk-and-school-breakfast-programs-national-average-paymentsmaximum. |

| 2. |

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is typically reauthorized with the child nutrition programs but is not considered a child nutrition program because it is not administered in institutional settings. For more information on WIC, see CRS Report R44115, A Primer on WIC: The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. |

| 3. |

Most of the child nutrition programs are "appropriated entitlements," meaning that the authorizing law sets a level of spending that Congress must fulfill through an appropriation. In FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018, enacted annual appropriation laws and continuing resolutions enabled the child nutrition programs to continue operating. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10266, An Introduction to Child Nutrition Reauthorization. |

| 4. |

Section 201 and Section 208 of P.L. 111-296. |

| 5. |

See, for example, C. Schwartz and M. Wootan, "How a Public Health Goal Became a National Law: The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010," Nutrition Today, January 16, 2019, pp. 6-8, https://journals.lww.com/nutritiontodayonline/Abstract/publishahead/How_a_Public_Health_Goal_Became_a_National_Law_.99960.aspx; N. Confessore, "How School Lunch Became the Latest Political Battleground," The New York Times Magazine, October 7, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/12/magazine/how-school-lunch-became-the-latest-political-battleground.html; and Nia-Malika Henderson, "President Obama signs child nutrition bill, a priority for first lady," Washington Post, December 13, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/12/13/AR2010121302407.html. |

| 6. |

USDA-FNS, "Nutrition Standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs," 77 Federal Register 17, January 26, 2012, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/01/26/2012-1010/nutrition-standards-in-the-national-school-lunch-and-school-breakfast-programs; USDA-FNS, "National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in School as Required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Final Rule," 81 Federal Register 50131, July 29, 2016, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/07/29/2016-17227/national-school-lunch-program-and-school-breakfast-program-nutrition-standards-for-all-foods-sold-in. For current nutritional requirements, see 7 C.F.R. 210.10 for the NSLP and 7 C.F.R. 220.8 for the SBP. |

| 7. |

Section 201, Section 208, and Section 441 of P.L. 111-296. |

| 8. |

See USDA-FNS, Comparison of Previous and New Regulatory Requirements, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/comparison.pdf. |

| 9. |

Related information is available at the USDA-FNS website: https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/tools-schools-focusing-smart-snacks. |

| 10. |

For the original implementation schedule based on the January 2012 final rule, see USDA-FNS, Implementation Timeline, http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/implementation_timeline.pdf. Most of the lunch requirements took effect in SY2012-2013, while most breakfast requirements took effect in SY2013-2014. |

| 11. |

Ibid. |

| 12. |

For examples of news coverage, see B. Wood, Students, parents, educators displeased with new school lunch standards, Deseret News, September 27, 2012, https://www.deseretnews.com/article/865563339/Students-parents-educators-displeased-with-new-school-lunch-standards.html; and L. Lopez, "We're Still Hungry!" Student Lunches Leave Stomachs Rumbling, NBCLA, September 26, 2012, https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/Los-Angeles-Unified-School-District-LAUSD-Nutrition-School-Lunch-No-Kid-Hungry-171439851.html. Also see School Nutrition Association, Stories from the Frontlines: School Cafeteria Professionals Discuss Challenges with New Standards, May 28, 2014, https://schoolnutrition.org/5—News-and-Publications/2—Press-Releases/Press-Releases/Stories-from-the-Frontlines—School-Cafeteria-Professionals-Discuss-Challenges-with-New-Standards/. |

| 13. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Implementing Nutrition Changes Was Challenging and Clarification of Oversight Requirements Is Needed, January 2014, https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/660427.pdf; Standing et al., Special Nutrition Program Operations Study: State and School Food Authority Policies and Practices for School Meals Programs School Year 2012-13, prepared by Westat for USDA-FNS, October 2016; J. Murdoch et al., Special Nutrition Program Operations Study, SY 2013-14 Report, prepared by 2M Research Services, 2016; GAO, USDA Has Efforts Underway to Help Address Ongoing Challenges Implementing Changes in Nutrition Standards, September 2015, https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/672477.pdf. Numerous studies have examined the efficacy of the nutrition standards in these and more recent school years in terms of a number of programmatic outcomes, including participation rates, food waste, and nutritional quality. It is beyond the scope of this report to review this entire body of literature. |

| 14. |

For example, see School Nutrition Association, 2014 Position Paper on Federal Child Nutrition Programs, https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/Legislation_and_Policy/SNA_Policy_Resources/SNA2014PositionPaper.pdf; and archived USDA-FNS web page, Support for Healthy Meals Standards Continues to Grow, May 2014, https://www.fns.usda.gov/pressrelease/2014/012714. |

| 15. |

USDA-FNS, "Certification of Compliance With Meal Requirements for the National School Lunch Program Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010," 79 Federal Register 325, January 3, 2014, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/01/03/2013-31433/certification-of-compliance-with-meal-requirements-for-the-national-school-lunch-program-under-the. |

| 16. |

P.L. 113-235, P.L. 114-113, and P.L. 115-31. |

| 17. |

USDA-FNS, "Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements; Interim Final Rule," 82 Federal Register 56703, November 30, 2017, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/11/30/2017-25799/child-nutrition-programs-flexibilities-for-milk-whole-grains-and-sodium-requirements. |

| 18. |

USDA-FNS, "Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements: Final Rule," 83 Federal Register 63775, December 12, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/12/12/2018-26762/child-nutrition-programs-flexibilities-for-milk-whole-grains-and-sodium-requirements. |

| 19. |

The final rule also allows flavored, low-fat milk to be served to children ages six and older in CACFP and SMP. |

| 20. |

USDA-FNS, Grain Requirements for the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program, SP 30-2012, April 26, 2012, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/SP30-2012os.pdf. "Whole grain-rich" products must contain at least 50% whole-grains, and the remaining grain, if any, must be enriched. |

| 21. |

The sodium targets set incrementally stricter weekly caps on sodium in school meals based on a student's grade level. The standards included three incrementally stricter targets that were to phase in over time (Target 1, Target 2, and Target 3). For example, for high school students, school lunches must contain ≤1,420 milligrams (mg) of sodium under Target 1, ≤1,080 mg under Target 2, and ≤740 mg under Target 3, on average over the school week. |

| 22. |

Section 4205 of H.R. 2 (as engrossed in the House on June 21, 2018). |

| 23. |

The Secretary of Agriculture, with consultation from school stakeholders, would have been required to certify that certain requirements were met, including that the regulations were age-appropriate, did not increase the costs of implementing the school meals programs, and did not discourage students from participating in the school meals programs. |

| 24. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44373, Tracking the Next Child Nutrition Reauthorization: An Overview. |

| 25. |

The SNA posted a January 15, 2016, statement of the terms of the agreement at https://schoolnutrition.org/News/AgreementReachedOnSchoolNutritionStandards/. The terms were also discussed in a colloquy between Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow and Senator John Hoeven during the committee's markup. |

| 26. |

Section 19 of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1769a). |

| 27. |

USDA-FNS, Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program: A Handbook for Schools, December 2010, p. 15, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/handbook.pdf. |

| 28. |

American Frozen Food Institute, House Support Expansion Letter of FFVP in CNR, April 7, 2016, http://www.affi.org/assets/resources/public/house-support-letter-expansion-of-ffvp-in-cnr-april-2016_2.pdf; United Fresh, National Produce Leaders FFVP Letter to House, April 21, 2016, https://www.unitedfresh.org/content/uploads/2016/05/National-Produce-Leaders-FFVP-Letter-to-House.pdf. |

| 29. |

USDA-FNS, Evaluation of the Pilot Project for Canned, Frozen, or Dried Fruits and Vegetables in the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (FFVP-CFD): Volume I: Report, prepared by Mathematica Policy Research, January 2017, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/FFVP-CFD.pdf. |

| 30. |

Section 12(n) of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1760(n)). Alaska is exempt and Hawaii and Puerto Rico are subject to separate but related requirements. |

| 31. |

U.S. Congress, Conference Committee, William F. Goodling Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act of 1998, conference report to accompany H.R. 3874, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., H.Rept. 105-786 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1998), p. 38. According to USDA guidance, more than 51% means that more than 51% of a product's "food components," as defined in 7 C.F.R. 210.2 (meats/meat alternatives, grains, vegetables, fruits, and fluid milk) and as measured by weight or volume must be domestically grown in the United States or U.S. territories. |

| 32. |

7 C.F.R. 210.21 and 7 C.F.R. 220.16. |

| 33. |

USDA-FNS, Compliance with and Enforcement of the Buy American Provision in the National School Lunch Program, SP 38-2017, June 30, 2017, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/SP38-2017os.pdf. |

| 34. |

Ibid. |

| 35. |

Ibid., p. 3. |

| 36. |

Section 12622 of H.R. 2 (as passed in the Senate on June 28, 2018). |

| 37. |

See, for example, National Council of Farmer Cooperatives et al., Enforcement of Buy American Provision Letter, December 2015, http://ncfc.org/letter/enforcement-of-buy-american-provision/; Murphy.senate.gov, Murphy, Feinstein, Boxer Call On Schools to Buy American & Support Local Farmers, https://www.murphy.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/murphy-feinstein-boxer-call-on-schools-to-buy-american-and-support-local-farmers; Lamalfa.house.gov, LaMalfa and Garamendi Introduce the "American Food for American Schools" Act, March 1, 2017, https://lamalfa.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/lamalfa-and-garamendi-introduce-the-american-food-for-american-schools. |

| 38. |

H. Bottemiller Evich, USDA's enforcement of 'Buy American' regulations strains school-meal programs, PoliticoPro, March 5, 2018. |

| 39. |

To learn more about these programs, see CRS Report R43783, School Meals Programs and Other USDA Child Nutrition Programs: A Primer. |

| 40. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Summer Meals: Actions Needed to Improve Participation Estimates and Address Program Challenges, May 2018, pp. 23-30, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/692193.pdf. |

| 41. |

USDA-FNS, Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC), https://www.fns.usda.gov/ops/summer-electronic-benefit-transfer-children-sebtc. |

| 42. |

Collins et al., Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (SEBTC) Demonstration: Summary Report, prepared by Abt Associates Inc. for USDA-FNS, May 2016, p.5, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/sebtcfinalreport.pdf. Also see USDA-FNS, WIC Food Packages - Regulatory Requirements for WIC-Eligible Foods, April 2018, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-food-packages-regulatory-requirements-wic-eligible-foods. |

| 43. |

The first year—the proof-of-concept year—was evaluated to test the feasibility of the EBT delivery system and to prepare for full implementation in demonstration sites for the following year. The second year—the full implementation year—evaluated the impact of SEBTC on improving children's food security and nutritional status in the summer time. Finally, the third year compared the impact of two benefit levels, $60 and $30, to determine the effect of different benefit levels on improving food security and nutritional status. Final reports and status reports to Congress are available on the USDA-FNS website, http://www.fns.usda.gov/ops/summer-electronic-benefit-transfer-children-sebtc. |

| 44. |

Collins et al., Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer for Children (SEBTC) Demonstration: Evaluation Findings for the Full Implementation Year, prepared by Abt Associates, Mathematica Policy Research, and Maximus (Alexandria, VA: USDA-FNS, 2013), p. 105. Very Low Food Security (VLFS) is the lowest of four levels of food security; USDA defines it as "At times during the year, eating patterns of one or more household members were disrupted and food intake reduced because the household lacked money and other resources for food." Improvements in VLFS varied significantly between Summer EBT sites. |

| 45. |

Ibid., p. 124. |

| 46. |

USDA-FNS, USDA Announces Summer EBT Grants; Includes New States, Rural Communities, June 28, 2017, https://www.fns.usda.gov/pressrelease/2017/006617. |

| 47. |

Ibid. |

| 48. |

Grants.gov, Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer for Children (Summer EBT) Grant Program: Fiscal Year 2019 Request for Applications, USDA-FNS, October 31, 2018, https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=310059. |

| 49. |

Details about the Obama Administration's Nationwide Summer EBT proposal are available in the FY2017 budget USDA-FNS Explanatory Notes on pp. 32-34, http://www.obpa.usda.gov/32fns2017notes.pdf. |

| 50. |

For example, see the Stop Child Summer Hunger Act of 2015 (S. 1539/H.R. 2715) in the 114th Congress and the Stop Child Summer Hunger Act of 2018 (H.R. 6516/S. 3268) in the 115th Congress. |

| 51. |

USDA-FNS, "Enhanced Summer Food Service Program (eSFSP)," https://www.fns.usda.gov/ops/enhanced-summer-food-service-program-esfsp. The eSFSP pilot states were Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Kansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, and Ohio. |

| 52. |

Elinson et al., Evaluation of the Summer Food Service Program Enhancement Demonstrations: 2012 Demonstration Evaluation Report, prepared by Westat for USDA-FNS, 2014, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/esfsp2012.pdf. |

| 53. |

Elinson et al., Evaluation of the Summer Food Service Program Enhancement Demonstrations: 2011 Demonstration Evaluation Report, prepared by Westat for USDA-FNS, November 2012, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/eSFSP_2011Demo_0.pdf. |

| 54. |

See chapter 6.2, "Study Strengths and Limitation," of Elinson et al., Evaluation of the Summer Food Service Program Enhancement Demonstrations: 2012 Demonstration Evaluation Report, prepared by Westat for USDA-FNS, 2014, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/esfsp2012.pdf. |

| 55. |

USDA-FNS, "Demonstration Project for Non-Congregate Feeding for Outdoor Summer Meal Sites Experiencing Excessive Heat with Q&As," May 24, 2018, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/sfsp/SP14_SFSP04-2018os.pdf. |

| 56. |

For example, see S. 613/H.R. 1728 and S. 1966 in the 114th Congress and H.R. 203 in the 115th Congress. During 114th Congress hearings, witnesses testified about SFSP and summer alternatives before the House Committee on Education and the Workforce (April 15, 2015; June 16, 2015; June 24, 2015) and the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry (May 7, 2015). In the 115th Congress, witnesses testified about SFSP and summer alternatives before the House Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education (July 17, 2018). |

| 57. |

Section 104 of the HHFKA added paragraph (F), "Universal Meal Service in High Poverty Areas" to Section 11(a)(1) of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (NSLA; 42 U.S.C. 1759a(a)(1)(F)). For more information about how CEP works, see CRS Report R43783, School Meals Programs and Other USDA Child Nutrition Programs: A Primer. Aside from CEP, schools may also provide universal free meal service through the "Provision 2" and "Provision 3" options. CEP is unique in that no school meal applications are required. For information on other options, see the USDA-FNS website, http://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/provisions-1-2-and-3. |

| 58. |

Food Research and Action Center, "Community Eligibility Continues to Grow in the 2016–2017 School Year," March 2017, http://www.frac.org/wp-content/uploads/CEP-Report_Final_Links_032317.pdf. |

| 59. |

The 22% represents 20,721 schools participating in CEP in SY2016-2017 out of 95,642 schools participating in NSLP in FY2017, according to participation data from USDA-FNS. This is an estimate because the time periods do not match precisely. |

| 60. |

For example, see No Kid Hungry, How the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) Can Help, http://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/programs/school-breakfast/about-the-community-eligibility-provision; Food Research and Action Center, Facts: Community Eligibility Provision, http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/frac-facts-community-eligibility-provision.pdf; and Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), Community Eligibility: Making High-Poverty Schools Hunger Free, October 1, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/community-eligibility-making-high-poverty-schools-hunger-free. |

| 61. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Education and the Workforce, Improving Child Nutrition and Education Act of 2016, report to accompany H.R. 5003, 114th Congress, 2nd session, H.Rept. 114-852, (Washington, DC: GPO, 2016), p. 54, https://www.congress.gov/114/crpt/hrpt852/CRPT-114hrpt852-pt1.pdf. Eligibility for CEP depends on a school's identified student percentage (ISP), the share of enrolled students who are identified as eligible for free school meals through direct certification. Under current law, a school, school district, or group of schools within a district must have an ISP of 40% or greater to use CEP. The House committee-reported bill would have increased this proportion to 60% or greater, reducing schools' eligibility for the option. |

| 62. |

Ibid., p. 163. |

| 63. |

Also see M. Levin and Z. Neuberger, Improving Direct Certification Will Help More Low-Income Children Receive School Meals, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and Food Research and Action Center, July 25, 2014, p. 3, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/implications-of-community-eligibility-for-the-education-of-disadvantaged. |

| 64. |

Exceptions include Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) schools/districts, which provide free meals to all students. Some have noted that providing free meals to all students can prevent lunch shaming. See, for example, James Weill, "How to stop school lunch shaming? Leave kids out of it," The Hill, http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/education/333003-how-to-stop-school-lunch-shaming-leave-kids-out-of-it; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Report to Congress: Review of Local Policies on Meal Charges and Provision of Alternate Meals, June 2016, at https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/unpaidmealcharges-report.pdf. |

| 65. |

See, for example, B. Duhart, Kids banned from field day if they owe lunch money. School says there's a $55,000 tab, NJ.com, June 13, 2018, https://www.nj.com/camden/index.ssf/2018/06/parent_claims_district_lunch_shams_kids_officials.html; S. Brown, Mass. Bill To Prevent 'Meal Shaming' Of Schoolchildren Unlikely To Pass This Session, WBUR.org, May 15, 2018, http://www.wbur.org/edify/2018/05/15/meal-shaming-bill; I. Hrynkiw, 'I need lunch money,' Alabama school stamps on child's arm, AL.com, June 13, 2016, https://www.al.com/news/birmingham/index.ssf/2016/06/gardendale_elementary_student.html; Dallas Morning News, Texas children could use school food pantry, avoid lunch shaming under proposed legislation, April 20, 2017, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/education/2017/04/20/texas-children-use-school-food-pantry-avoid-lunch-shaming-proposed-legislation. |

| 66. |

USDA, Report to Congress: Review of Local Policies on Meal Charges and Provision of Alternate Meals, June 2016, p. 5, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/unpaidmealcharges-report.pdf. |

| 67. |

USDA-FNS, "Unpaid Meal Charges: Clarification on Collection of Delinquent Meal Payments," July 8, 2016, p. 2, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/SP47-2016os.pdf. |

| 68. |

7 C.F.R. 200.426. |

| 69. |

Specifically, Section 143 of the HHFKA authorized USDA to (1) implement standards, (2) implement demonstration projects, or (3) further study the feasibility of the recommendations. |

| 70. |

USDA, Report to Congress: Review of Local Policies on Meal Charges and Provision of Alternate Meals, June 2016, p. 5, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/unpaidmealcharges-report.pdf. |

| 71. |

USDA-FNS, "Unpaid Meal Charges: Local Meal Charge Policies," July 8, 2016, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/SP46-2016os.pdf. The best practice guide is called "2017 Edition: Overcoming the Unpaid Meal Challenge: Proven Strategies from Our Nation's Schools," available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/2017-edition-overcoming-unpaid-meal-challenge-proven-strategies-our-nations-schools. |

| 72. |

For a list of resources, see USDA-FNS, "Unpaid Meal Charges," https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-meals/unpaid-meal-charges. |

| 73. |

May et al., Special Nutrition Program Operations Study: State and School Food Authority Policies and Practices for School Meals Programs School Year 2011-12, prepared by Westat under Contract No. AG-3198-D-10-0048 (Alexandria, VA: USDA-FNS, March 2014), pp. 147-148, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/SNOPSYear1.pdf; USDA-FNS, "Request for Information: Unpaid Meal Charges," 79 Federal Register 62095, October 16, 2014, https://www.regulations.gov/docketBrowser?rpp=25&po=0&dct=PS&D=FNS-2014-0039. |

| 74. |

May et al., Special Nutrition Program Operations Study: State and School Food Authority Policies and Practices for School Meals Programs School Year 2011-12, prepared by Westat under Contract No. AG-3198-D-10-0048 (Alexandria, VA: USDA-FNS, March 2014), pp. 147-148, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/SNOPSYear1.pdf. |

| 75. |

Ibid. |

| 76. |

USDA-FNS, "Request for Information: Unpaid Meal Charges," 79 Federal Register 62095, October 16, 2014, https://www.regulations.gov/docketBrowser?rpp=25&po=0&dct=PS&D=FNS-2014-0039. |

| 77. |

USDA, Report to Congress: Review of Local Policies on Meal Charges and Provision of Alternate Meals, June 2016, p. 3-5, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/unpaidmealcharges-report.pdf. |

| 78. |

See Section 768 (Title VII of Division A) of P.L. 115-141, which references Section 9(b)(10) of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1758(b)(10)) and 7 C.F.R. 245.8. |

| 79. |

Specifically, the legislation would have prohibited SFAs from (1) publicly identifying children who cannot pay for a meal or those who have meal debt, (2) having those children perform chores or other activities, and (3) throwing away a child's meal. See Section 2 of H.R. 2401 and S. 1064 (identical text). |

| 80. |

School Nutrition Association, State Legislation and Policy Reports, 2016-2018, https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/Legislation_and_Policy/State_and_Local_Legislation_and_Regulations/SNA-2018-Third-Quarter-State-Legislative-Report.pdf; D. Temkin, and A. Cox, State policies to address school lunch shaming, Child Trends, February 2018, https://www.childtrends.org/state-policies-address-school-lunch-shaming. |

| 81. |

Illinois State Legislature, Hunger-Free Students' Bill of Rights Act (Public Act 100-1092), https://legiscan.com/IL/bill/SB2428/2017. |

| 82. |

Section 205 of P.L. 111-296, codified at 42 U.S.C. 1760(p) and 7 C.F.R. 210.14. |

| 83. |

7 C.F.R. 210.14 and Section 12(p) of the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act (42 U.S.C. 1760(p)). |

| 84. |

Ibid. Financial support from nonfederal sources must be "for the direct support for paid lunches." Revenue from competitive foods and funds specified for the School Breakfast Program, free or reduced-price lunches, or other child nutrition programs cannot be used. |

| 85. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, report to accompany S. 3307, 111th Congress, 2nd session, S.Rept. 111-178, (Washington, DC: GPO, 2010), pp. 37-38, https://www.congress.gov/111/crpt/srpt178/CRPT-111srpt178.pdf. |

| 86. |

S. Bartlett, F. Glantz, and C. Logan, School Lunch and Breakfast Cost Study-II, USDA-FNS, Office of Research, Nutrition and Analysis, final report, April 2008, https://www.fns.usda.gov/school-lunch-and-breakfast-cost-study-ii. |

| 87. |

7 C.F.R. 210.14. These three meal categories are subsidized by the federal government in increasing amounts. For example, in school year 2018-19, the federal reimbursement was $0.37 for paid lunches, $2.97 for reduced-price lunches, and $3.37 for free lunches for many schools. |

| 88. |

For example, see School Nutrition Association, 2015 Position Paper Reauthorization of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act: Modify Section 205, https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/Legislation_and_Policy/SNA_Policy_Resources/6-2015PP-PaidLunchEquityOnePager.pdf. |

| 89. |

USDA-FNS, "National School Lunch, Special Milk, and School Breakfast Programs, National Average Payments/Maximum Reimbursement Rates," 83 Federal Register 34105, July, 19, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/07/19/2018-15465/national-school-lunch-special-milk-and-school-breakfast-programs-national-average-paymentsmaximum. |

| 90. |

Section 206 of P.L. 111-296. |

| 91. |

7 C.F.R. 210.14. |

| 92. |