The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: An Overview

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended) established the Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) to assist vulnerable individuals and their families during the transition to parenthood. Specifically, the program serves expectant and parenting teens, women, fathers, and their families. This includes women of any age who are survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, and stalking. The PAF program focuses on meeting the educational, social service, and health needs of eligible individuals and their children during pregnancy and the postnatal period.

The research literature indicates that pregnancy has high costs for individuals eligible for the PAF program. Teenage mothers and fathers tend to have less education and are more likely to live in poverty than their peers who are not parenting. Nearly one-third of adolescent females who have dropped out of high school cite pregnancy or parenthood as a reason. Parenthood can also influence whether students pursue postsecondary education. One analysis found that single young women who had children after enrolling in community college were 65% more likely to drop out than their same-age peers who did not have children after enrolling. The research literature further indicates that approximately 3% to 9% of women experience domestic violence during pregnancy. Some studies indicate that this risk is greater among low-income women.

The PAF program is administered by the Office of Adolescent Health (OAH) in the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH). HHS distributes PAF funding on a competitive basis to the states, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, and tribal entities. Through FY2018, HHS has awarded PAF funding to 30 states, the District of Columbia, and 5 tribal entities (“grantees”). These grantees can decide how to use funding under four purpose areas. Three of the purpose areas focus on providing services to the eligible expectant and parenting population through subgrants and partnerships. The fourth category focuses on public awareness about such services; however, HHS advises that grantees may not use funding solely for public awareness activities. In general, grantees have provided subgrants to school districts, community service organizations, and institutions of higher education (IHE) that directly serve the expectant and parenting population. Subgrantees have most frequently provided case management, referral services for other supports, group workshops on specific topics (e.g., pregnancy prevention), and home visiting services.

The PAF statute and the program grant announcements include requirements for state grantees and subgrantees in carrying out activities under the program. The authorizing law requires each subgrantee to provide an annual report to the grantee about expenditures, fulfilling program requirements, and how it meets the needs of participants. Grantees must prepare an annual report to HHS on information provided by subgrantees, including participant data. In FY2016, grantees (17 states and 3 tribal entities) reported serving 16,053 individuals. Of these participants, 55% were expectant or parenting mothers, 37% were children, and 8% were expectant or parenting fathers. Most expectant or parenting participants were ages 16 through 19, and nearly half of all participants were white, about one-third were black, and the remaining share were another race or multiracial. About half of all participants were Hispanic.

The ACA provides mandatory PAF funding of $25 million annually from FY2010 through FY2019. If Congress considers reauthorizing the program, it may look to emerging findings from a recent evaluation that may indicate the program is helping to keep pregnant and parenting students in the District of Columbia connected to their high schools. Among other topics, Congress may consider whether to establish guidelines regarding how the PAF program should interact with other, similar federal programs in the areas of education, health, and social services.

The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: An Overview

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Legislative History

- Vulnerability During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period

- The Role of PAF in Responding to Vulnerabilities

- Distribution and Use of Program Funds

- Activities Provided via High Schools, Community Service Centers, and IHEs

- Activities on Behalf of Victimized Women Who Are Pregnant or Parenting

- Public Awareness Activities

- Grant Requirements

- Approach for Providing Services and Selecting Partners

- Reporting on Expenditures and Performance

- Interaction with Other Program Funding

- Medical Accuracy

- Grants Awarded

- FY2016 Data on Program Subgrants, Participants, and Implementation

- Subgrants

- Participants

- Services Provided to Participants

- Trainings and Partnerships

- Program Effectiveness

- PAF in the Context of Other Federal Programs

- Education

- Social Services

- Health

- Issues for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1.Flow of PAF Funding and Examples of Supports Provided

- Figure 2.Jurisdictions Receiving Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) Grants

- Figure 3.PAF Participants by Age and Race, FY2016

- Figure 4.PAF Services Provided by Number of Participants, FY2016

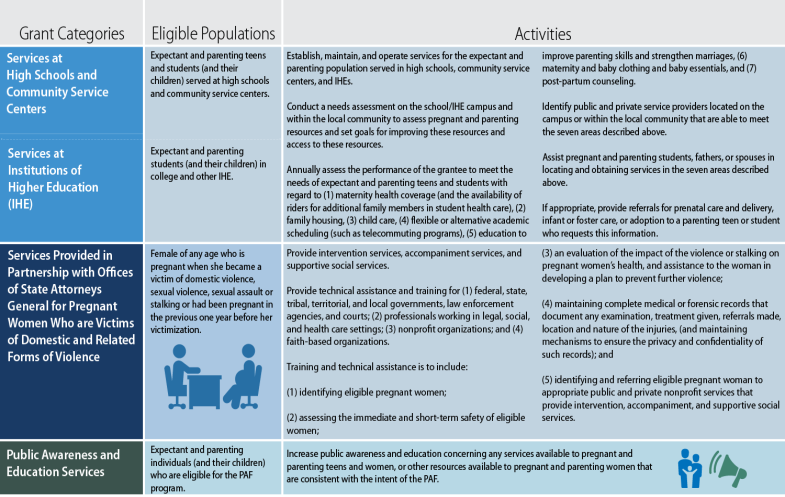

- Figure A-1. Eligible Populations and Activities Specified in Authorizing Law for the Four PAF Grant Categories (42 U.S.C. §18203)

Summary

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended) established the Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) to assist vulnerable individuals and their families during the transition to parenthood. Specifically, the program serves expectant and parenting teens, women, fathers, and their families. This includes women of any age who are survivors of domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, and stalking. The PAF program focuses on meeting the educational, social service, and health needs of eligible individuals and their children during pregnancy and the postnatal period.

The research literature indicates that pregnancy has high costs for individuals eligible for the PAF program. Teenage mothers and fathers tend to have less education and are more likely to live in poverty than their peers who are not parenting. Nearly one-third of adolescent females who have dropped out of high school cite pregnancy or parenthood as a reason. Parenthood can also influence whether students pursue postsecondary education. One analysis found that single young women who had children after enrolling in community college were 65% more likely to drop out than their same-age peers who did not have children after enrolling. The research literature further indicates that approximately 3% to 9% of women experience domestic violence during pregnancy. Some studies indicate that this risk is greater among low-income women.

The PAF program is administered by the Office of Adolescent Health (OAH) in the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH). HHS distributes PAF funding on a competitive basis to the states, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, and tribal entities. Through FY2018, HHS has awarded PAF funding to 30 states, the District of Columbia, and 5 tribal entities ("grantees"). These grantees can decide how to use funding under four purpose areas. Three of the purpose areas focus on providing services to the eligible expectant and parenting population through subgrants and partnerships. The fourth category focuses on public awareness about such services; however, HHS advises that grantees may not use funding solely for public awareness activities. In general, grantees have provided subgrants to school districts, community service organizations, and institutions of higher education (IHE) that directly serve the expectant and parenting population. Subgrantees have most frequently provided case management, referral services for other supports, group workshops on specific topics (e.g., pregnancy prevention), and home visiting services.

The PAF statute and the program grant announcements include requirements for state grantees and subgrantees in carrying out activities under the program. The authorizing law requires each subgrantee to provide an annual report to the grantee about expenditures, fulfilling program requirements, and how it meets the needs of participants. Grantees must prepare an annual report to HHS on information provided by subgrantees, including participant data. In FY2016, grantees (17 states and 3 tribal entities) reported serving 16,053 individuals. Of these participants, 55% were expectant or parenting mothers, 37% were children, and 8% were expectant or parenting fathers. Most expectant or parenting participants were ages 16 through 19, and nearly half of all participants were white, about one-third were black, and the remaining share were another race or multiracial. About half of all participants were Hispanic.

The ACA provides mandatory PAF funding of $25 million annually from FY2010 through FY2019. If Congress considers reauthorizing the program, it may look to emerging findings from a recent evaluation that may indicate the program is helping to keep pregnant and parenting students in the District of Columbia connected to their high schools. Among other topics, Congress may consider whether to establish guidelines regarding how the PAF program should interact with other, similar federal programs in the areas of education, health, and social services.

Introduction

The Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) seeks to improve the educational, health, and social outcomes for vulnerable individuals who are expectant or new parents and their children.1 PAF is administered by the Office of Adolescent Health (OAH) in the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) established the program and provided $25 million in annual mandatory funding for a 10-year period from FY2010 through FY2019.2

PAF funding is awarded competitively to the 50 states, District of Columbia (DC), U.S. territories, and tribal entities that apply successfully. The grantees may use the funds for any of the following purposes:

- providing subgrants to institutions of higher education (IHEs), high schools, or community service providers to enable these subgrantees to establish, operate, or maintain pregnancy or parenting services for the expectant and parenting population;

- providing, in partnership with the state attorney general's office, certain legal support, hotline, and other supportive services for women who experience domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking while they are pregnant or parenting an infant; and

- supporting, either directly or through a subgrantee, public awareness about PAF services for the expectant and parenting population, including individuals who are victims of domestic violence and sexual violence.

Through FY2018, HHS has awarded PAF funding to 30 states, DC, and 5 tribal entities. Generally, these grantees have provided PAF subgrants to high schools, community service organizations, and IHEs. Subgrantees reported most frequently using the funds to support case management, referrals to other supports, group workshops on specific topics (e.g., pregnancy prevention), and home visiting services.3

Congress may consider extending program funding beyond FY2019, when mandatory spending authority lapses. This report provides background to Congress about the program's implementation. It first discusses the history of PAF's enactment, the challenges facing vulnerable expectant and new parents who are eligible for PAF, and an overview of how program funding is distributed to meet those challenges consistent with the authorizing statute. Next, the report discusses selected program requirements. Data on participants and services provided in FY2016 are also presented, along with findings from an early evaluation showing the services to be effective in at least a limited context. The report then discusses the role of PAF in the context of other federal programs with certain overlapping or related goals, and it concludes with a brief discussion of considerations for Congress if it chooses to extend the program.

Background

Legislative History

Section 10212 of the ACA established PAF "to assist pregnant and parenting teens and women." The legislative language for the PAF program originated in an amendment by Senator Bob Casey that was printed in the Congressional Record on December 9, 2009, during Senate consideration of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R. 3590).4 This amendment was not subsequently offered on the floor. Instead, the PAF legislative language was included as an amendment to H.R. 3590 that was agreed to by the Senate on December 22, 2009. The Senate passed H.R. 3590, as amended, on December 24, 2009, with the PAF language at Section 10212. The House agreed to the Senate amendment to the bill on March 21, 2010.5

The PAF provision appears to have been added as a way to bolster supports for pregnant youth and women who might otherwise consider abortion.6 A press release from Senator Casey about PAF and selected other programs in the context of health care reform stated: "it was critically important to me to include positive support for vulnerable pregnant women, which the research clearly shows as the most effective way to reduce the number of abortions."7

Vulnerability During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period

The PAF program focuses on meeting the educational, social service, and health needs of vulnerable expectant and parenting individuals and their children during pregnancy and the postnatal period. The authorizing statute identifies these populations as expectant and parenting teens, college students, young adults, or women of any age who experience domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, and stalking.

About 194,400 births in the United States in 2017 (5.0%) were to teenagers aged 15 to 19.8 The research literature indicates that teen pregnancy has high costs for the families of teen parents and society more generally.9 Teenage mothers and fathers tend to have less education and are more likely to live in poverty than their peers who are not parents. Nearly one-third of teen girls who have dropped out of high school cite pregnancy or parenthood as a reason. Children of teenage mothers are more likely to have poorer education, health, and social outcomes than children of mothers who delay childbearing. In addition, teen births lead to larger societal impacts, such as costs related to public sector health care and lost tax revenue.10 Parenthood can also influence whether students pursue postsecondary education. For example, one analysis found that single young women who had children after enrolling in community college were 65% more likely to drop out than their same-age peers who did not have children after enrolling.11

PAF also provides supports for teens and women who are victims of domestic violence or sexual violence while they are pregnant or parenting an infant.12 The research literature indicates that approximately 3% to 9% of women experience domestic violence during pregnancy.13 Some studies indicate that this risk is greater among low-income women. Domestic violence is associated with heightened sexual risk-taking by the woman or her partner, such as inconsistent condom use and greater risk of having an unplanned pregnancy or induced abortion.14 Women victimized during pregnancy have poorer maternal health outcomes than women who are not abused, and their babies face health challenges. These women are 2 1/2 times more likely to report depressive symptoms than pregnant women who are not abused. Research on neonatal outcomes indicates that babies born to victimized women tend to have low birth weight and increased risk of pre-term birth, both of which are leading causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality.15

The Role of PAF in Responding to Vulnerabilities

As part of a process study about the PAF program, HHS has found that state and tribal grantees used their own needs assessments or needs assessments from other programs to determine that few supports have been available in communities to meet the needs of the pregnant and parenting population that is eligible for PAF, such as teens and other young parents.16 These other needs assessments were drawn from programs serving similar populations or seeking similar participant outcomes, such as the federal Personal Responsibility Education program (PREP) to prevent teen pregnancy and the federal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program.17 Grantees reported that in response to these assessments, they have focused on avoiding redundancy in services and building connections across agencies and providers. Specifically, the grantees reported that PAF funds are intended to

- fill gaps in services available to vulnerable expectant and parenting individuals, particularly supports for father engagement, mental health, transportation, and child care;

- enhance an existing service by adding or refining components and making services available to more vulnerable expectant and parenting individuals, such as by expanding the number of sites at which individuals are served; and/or

- improve coordination across state or tribal agencies to avoid duplication of program services and make services more readily accessible, such as through formal and informal partnerships, joint trainings, and sharing resources.18

Distribution and Use of Program Funds

HHS distributes PAF funding on a competitive basis to address the vulnerabilities of the expectant and parenting populations and their children. The 50 states, DC, territories, and tribal entities may apply for PAF funding (hereinafter, "state grantees").19 State grantees must specify how they intend to use the funds and identify the lead agency to administer such funds.20 In the most recent cohort of grantees, the state public health department was the most frequently designated lead agency. State departments of education or human services and other entities also served as lead agencies.21

State grantees determine how to use their PAF funding to serve the expectant and parenting population and their children within four purpose areas:

- providing subgrants to high schools and community service centers,

- providing subgrants to institutions of higher education (IHEs),

- partnering with offices of state attorneys general, and

- supporting public awareness activities, as provided either by state grantees directly or by their subgrantees and partners.

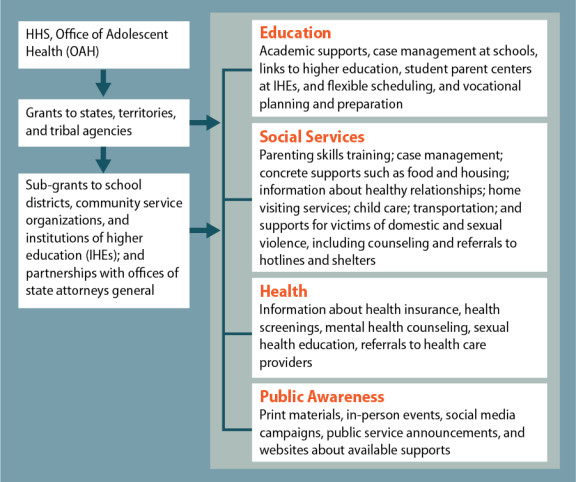

Figure 1 shows how PAF funding flows from the federal government to state grantees, and then on to subgrantees that directly support participants. It also includes examples of the types of supports that have been provided with PAF funding. In general, these supports can be grouped as education, social services, health, or public awareness activities.

Each purpose area specifies certain activities. The activities are generally the same for the high schools/community service centers and IHEs, and therefore are grouped together in the subsequent discussion. (Figure A-1 summarizes the four purpose areas, the populations they target, and the activities supported in each of the categories.)

Activities Provided via High Schools, Community Service Centers, and IHEs

State grantees provide subgrants to high schools, community service centers, and IHEs for these institutions to establish, maintain, or operate services for pregnant and parenting teens/students and their children. The law defines (1) "high school" as public and private schools that operate grades 7 through 12, 9 through 12, or 10 through 12; (2) "community service centers" as nonprofit organizations that provide social services to residents of a specific geographic area via direct service or by a contract with a local governmental agency; and (3) an "eligible institution of higher education" as a vocational school or public or nonprofit private college or university. Such institution of higher education must establish and operate, or agree to establish and operate (if it receives PAF funding), an office for pregnant and parenting students.22

The law specifies that subgrantees can carry out selected activities on campus and in the local community. Such activities include conducting a needs assessment to assess pregnancy and parenting resources on the campus and within the community, and setting goals for improving such resources and access to them. Other activities include annually assessing the performance of the subgrantee in meeting needs such as the inclusion of maternity coverage and availability of riders for additional family members in student health coverage, child care, flexible or alternative academic scheduling, parenting education, and basic provisions such as maternity and baby clothing and baby food. Further, subgrantees may use the funds to identify service providers on a high school or IHE campus or within the local community to help meet these needs; assist pregnant and parenting students, fathers, or spouses in locating and obtaining services to meet needs; and, if appropriate, provide referrals to service providers for prenatal care and delivery, infant or foster care, or adoption.23

IHEs must provide a 25% match of their grant awards with funds or nonmonetary support, such as services and facilities.24 This match is not required for high schools or community service centers.

Activities on Behalf of Victimized Women Who Are Pregnant or Parenting

State grantees partner with offices of state attorneys general to provide specified activities—intervention services, accompaniment services, and supportive social services—targeted to individuals of any age who are pregnant or have been pregnant in the past year and are of victims of domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, or stalking. The term "intervention services" means 24-hour telephone hotline services for police protection and referral to shelters. The term "accompaniment services" means assisting, representing, and accompanying a woman in seeking judicial relief for child support, child custody, restraining orders, and restitution for harm to persons and property; and help with filing criminal charges. It may include the payment of court costs and reasonable attorney and witness fees that are associated with the charges. The term "supportive social services" means transitional and permanent housing, vocational counseling, and individual and group counseling aimed at preventing domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, or stalking.25

This purpose area also focuses on providing training and technical assistance—related to domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual assault, and stalking against pregnant women or women who were pregnant within the past year—to specified entities, such as government agencies, professionals working in social services and other settings, and nonprofit organizations.

Public Awareness Activities

State grantees and/or their subgrantees can fund public awareness activities for the broader population of vulnerable expectant and parenting individuals, rather than focusing on the more-narrow populations as with the other grant categories. Such activities can include print materials, in-person events, social media campaigns, public services announcements, and websites. State grantees are responsible for setting guidelines or limits on how much funding is to be used for public awareness activities. The grant announcement specifies that information may not be provided about abortion services.26

|

PAF Grantee Profile: Washington State The Washington State Department of Health carries out PAF under multiple program purpose areas. It makes subgrants to the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, which uses funds to improve child care centers and parenting skills among young parents at those centers. Other subgrants fund a community service organization that provides parenting education and access to child developmental screenings statewide; and community service organizations that implement evidence-based or evidence-informed programs with home visiting, parenting skills classes, and prevention-focused youth development activities. Finally, the Washington State Attorney General's Office works with local agencies in four counties to implement the Futures Without Violence Safety Card intervention, which providers use to ask teen mothers a series of questions to facilitate referrals to related local services. The Attorney General's Office also partners with the state domestic violence and sexual assault coalitions to provide workshops on reproductive coercion and emergency contraception. Source: Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, Mathematica Policy Research. This is one example of the types of activities that can be funded by grantees, and Washington State was selected by CRS for illustrative purposes only. |

Grant Requirements

The PAF statute and the program grant announcements include requirements for state grantees and subgrantees in carrying out activities under the PAF program. For the purposes of this section, "grantees" generally means applicants; however, some of the requirements discussed apply only to applicants who were selected to receive PAF funding.

Approach for Providing Services and Selecting Partners

As part of their application for funding, state grantees must describe their approach for serving the expectant and parenting population and the outcomes they intend to achieve. Further, state grantees must specify how participants will be recruited and in which communities or sites they will be served. State grantees do not need to identify subgrantees (unless known) as part of the application but must describe the process and criteria for selecting them.

In describing the selection process, state grantees must articulate a plan for monitoring subgrantees and partnerships, including how to ensure that efforts are coordinated in serving the expectant and parenting population. State grantees have reported using a variety of different systems for monitoring subgrantees, including formal management information systems and online platforms. They also used other monitoring tools such as referral forms, participant surveys, and intake forms.27

Reporting on Expenditures and Performance

The PAF authorizing law requires each subgrantee to provide an annual report to the state grantee that (1) itemizes the expenditures used to serve the expectant and parenting population; (2) contains a review and evaluation of the performance of the subgrantee in fulfilling program requirements, based on performance criteria or standards established by the grantee; and (3) describes the subgrantee's achievements in meeting the needs of expectant and parenting individuals and the frequency with which they used services. Grantees must prepare an annual report to HHS on this information provided by subgrantees, the number of subgrantees that were awarded funds, and the number of expectant and parenting individuals who were served.28

PAF grant applications have directed state grantees to describe their plans for collecting performance data from all sites in which the grant is implemented and using data to improve the quality of programming. Grantees must submit selected performance data to HHS following each 12-month budget period, including data that generally fall into the following categories:

- the number of sites at which the grant was implemented, by type of site;

- the number of expectant and parenting individuals served, including data by sex, race, ethnicity, and age;

- the number of dependent children of an expectant or parenting student, teen, or young adult;

- the number of referrals provided to expectant and parenting individuals for selected services;

- the number of services in support of pregnant individuals, or individuals who were pregnant within the past year, who are victims of domestic or sexual violence;

- training and professional development of grantee or partner staff; and

- partnerships with subgrantees and other entities that help to implement PAF.29

(A subsequent section of this report provides some of this information for FY2016, including demographic information on participants, services and referrals provided, and training and partnerships.)

State grantees must also submit quarterly financial reports about their spending under the grant and have a plan for oversight of PAF funding, among related requirements.30

Interaction with Other Program Funding

The PAF grant announcements direct state grantees to include in their funding application the amount of funding available from other federal and nonfederal sources under various spending categories (e.g., personnel, equipment, supplies). Grantees must describe the resources available at each relevant site where the program will be implemented. HHS does not require state grantees or their subgrantees to report on how PAF funds interact with other sources of payment for similar services (e.g., Medicaid for health care services); however, grantees must describe in their funding application how PAF-funded services will contribute to and enhance, rather than supplant, the services already available.31

Medical Accuracy

Per the PAF grant announcements, state grantees must also ensure that materials used in activities funded under PAF are "medically accurate and complete." This means that information provided by state grantees or subgrantees is to be referenced to peer reviewed publications by educational, scientific, governmental, or health organizations. State grantees must describe the process they used to ensure medical accuracy, including how the review of materials was conducted and who was responsible for reviewing the materials.32

Grants Awarded

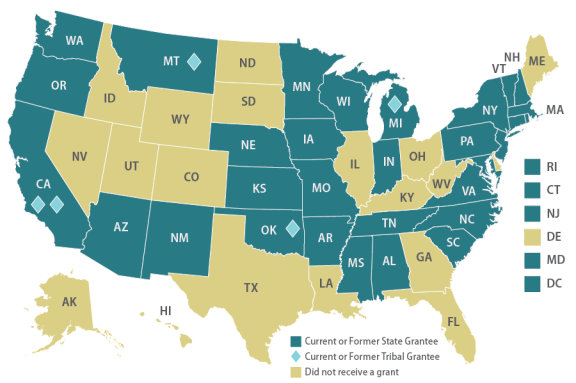

Through FY2018, OAH has awarded five rounds (or "cohorts") of funding to 30 states, DC, and five tribes across these cohorts (see Figure 2). (Table A-1 lists each of the grantees for each cohort.) Funding levels have generally ranged from $380,000 to $1,500,000 annually, with a mean of approximately $1,200,000.33

The grant periods have ranged from 1 year (cohort 4, FY2017) to 4 years (cohort 2, FY2013-FY2016). HHS shortened the grant period for cohort 3 grantees from 5 years to 3 years.34 HHS expects to provide funding for two to three additional grantees with FY2019 funding.35

FY2016 Data on Program Subgrants, Participants, and Implementation36

Subgrants

State grantees are not limited in how many subgrantees or which grant purpose areas they can fund; however, they may not use the funds solely for public awareness activities. The most recent information on state grantee distribution of funds is from FY2016. In that year, PAF funds supported 20 state and tribal grantees. Grantee activity included the following:

- 18 grantees made subgrants to high schools and community service providers;

- 3 grantees made subgrants to IHEs;

- 5 grantees partnered with state attorney general's offices to provide services regarding domestic or sexual violence; and

- 10 grantees supported public awareness activities.

Participants

HHS collects and reports data on the expectant and parenting individuals and their children who receive PAF services. In FY2016, the 20 grantees served 16,053 individuals. Of these participants, 55% were expectant or parenting mothers, 37% were children, and 8% were expectant or parenting fathers.

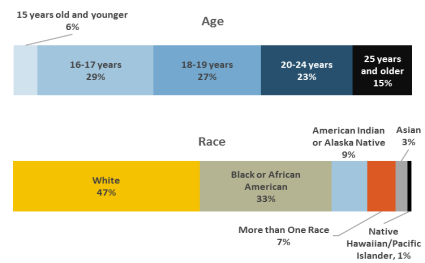

HHS provides race and age data for expectant and parenting mothers and fathers only (and not their children). Figure 3 displays this data for FY2016. More than half (56%) of the expectant and parenting individuals were ages 16 to 19, and almost one-quarter were ages 20 to 24. Another 6% were under the age of 15 and 15% were age 25 or older. Data on race are available for about 6 of 10 expectant and parenting participants. Of these participants, nearly half were white, about one-third were black, and the remaining share were another race or multiracial. Nearly half (46%) of the expectant and parenting participants who reported on ethnicity were Hispanic (not shown in figure).

In FY2016, most participants (11,562 out of 16,053 total) received services via high schools and community service providers that were subgrantees. Of these participants, most were expectant or parenting mothers (60%), followed by children (32%) and expectant or parenting fathers (8%). Nearly two-thirds of the mothers and fathers were in high school. By the end of FY2016, nearly all of the participants who were seniors in high school had graduated and slightly over half of those who were high school seniors or preparing for a GED had been accepted into an IHE. Less than 1 of 10 participants who were enrolled in high school had dropped out.

Also in FY2016, another 3,479 participants received services via IHEs that received subgrants. Most were children (55%), followed by expectant or parenting mothers (39%) or expectant or parenting fathers (6%). Of the parents, nearly all were ages 20 or older and the majority were in community colleges.

Finally, 666 participants received services related to domestic and sexual violence in FY2016. Of these, almost 71% were expectant or parenting mothers and 28% were their children.37

In certain grant cohorts, HHS has emphasized that grantees should serve selected populations. For example, the funding announcement for the fourth cohort (with funding that began in FY2017) emphasized that grantees should serve "marginalized" populations: youth involved in child welfare or juvenile justice; runaway and homeless youth; immigrants; individuals with disabilities; and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) youth.38 The funding announcement for the fifth cohort (with funding that began in FY2018) does not mention marginalized populations, and notes that PAF grantees should provide supports to young fathers only if they provide supports more broadly to pregnant and parenting girls and women.39

Services Provided to Participants

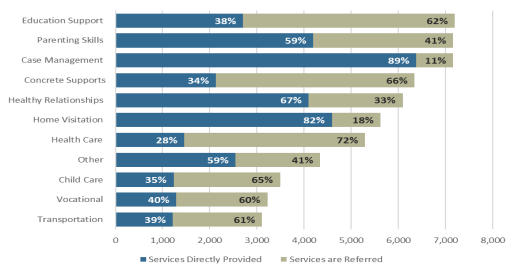

Figure 4 shows the number of participants by the PAF-funded services they received in FY2016. The figure also shows whether the services were provided directly by the 20 grantees that year (and their subgrantees, where applicable) or whether they were provided via organizations to which participants were referred. Of the 16,053 PAF participants in FY2016, the greatest number received educational services (7,195) followed by parenting skills training (7,161) and case management (7,157). Approximately one-third of participants (5,194) received health care services.40 Some services were more likely to be provided directly by grantees or subgrantees (e.g., case management and home visiting services), while other services were more likely to be provided by organizations to which recipients were referred (e.g., health care and concrete supports such as food, housing, clothing, and furniture).

HHS did not report services in FY2016 for victims of domestic violence based on whether the services were provided directly or by referral (and they therefore are not included in Figure 4). Grantees that served domestic violence victims most frequently provided supportive social services (404 participants), followed by accompaniment services (142 participants) and intervention services (275 participants).41

Trainings and Partnerships

State grantees report on the number of program facilitators who were trained and the partnerships they formed to support their PAF programs. In FY2016, state grantees reported that 322 new facilitators were trained and 1,280 facilitators received follow-up training. In addition, state grantees reported that over 2,900 professionals were trained on domestic or sexual violence against pregnant women or women who had been pregnant in the past year. Also that same year, state grantees reported that they worked with 355 formal and 878 informal partners, for a total of 1,213 partnerships. Partners are organizations that work with grantees and subgrantees to support their programs, either with or without a formal agreement with the grantee.

Program Effectiveness

HHS has contracted with Mathematica Policy Research, a social policy research organization, to conduct a process evaluation of how the PAF program is carried out and an impact evaluation about the effectiveness of the program in shaping youth outcomes.42 As discussed, the process evaluation provided background information on the design and implementation of the PAF programs in the second and third cohorts.43 The impact evaluation is measuring selected outcomes of PAF participants in California and DC.44 The outcomes vary depending on the site, and include those related to subsequent pregnancy, sexual risk behaviors, school engagement, educational attainment, or parenting skills.

Findings are available for the program in DC, where PAF-funded services were provided in nine high schools through a voluntary program known as New Heights.45 Case coordinators from the program were embedded at the schools to provide (1) one-on-one case management to help youth meet their educational goals; (2) weekly educational workshops held three times a week to provide supplemental education on relevant topics; and (3) in-kind incentives that students earn when they attain personal goals and use for purchasing items such as maternity and baby supplies. Researchers found that teen mothers in the program improved in school engagement and credits earned per year compared to teen mothers who attended the high schools immediately before the program was introduced. The participants were significantly more likely to have excused absences (and significant less likely to have unexcused absences), to attend more days of school per semester, and to graduate.

PAF in the Context of Other Federal Programs

Because of its cross-cutting approach to meeting the needs of the expectant and parenting population, PAF may overlap with activities of other programs serving the needs of broader populations. PAF can also play a role in referring expectant and parenting individuals to the other programs as appropriate, though the authorizing law does not reference these programs. Some examples of such programs in education, social services, and health are discussed in this section.

Education

PAF grantees may provide services to ensure that expectant and parenting individuals can successfully complete their secondary or postsecondary education. As shown in Figure 4, more than 3,000 PAF participants received child care services in FY2016. A similar program, the Child Care Access Means Parents in School Program (CCAMPIS), authorized under the Higher Education Act (HEA), authorizes funds for child care to low-income parents in postsecondary settings. The program has funded child care in a relatively small number of IHEs in about half of the states.46

Social Services

PAF grantees offer a variety of social services intended to improve self-sufficiency and parenting skills, ensure child well-being, and address domestic violence. A number of federal programs also seek to offer these kinds of supports to broader groups of individuals. For example, the MIECHV program provides home visiting services for families with young children who reside in communities that have concentrations of poor child health and other risk indicators. As shown in Figure 4, PAF grantees reported that home visiting was one of the most frequently provided services in FY2016. An evaluation of a home visiting program in Texas adapted for teen mothers has shown promise in reducing repeat pregnancies.47

Further, certain PAF grantees can use funding to provide adoption referrals. Under the federal Adoption Opportunities program, expectant parents can receive information about adoption. This program has provided funding to support training on infant adoption awareness.

Also as with PAF, two federal laws authorize supports for victims of domestic and related violence: the Family Violence Prevention Services Act (FVPSA) and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA). These laws have a broader focus than just pregnant women and parents, and reach more recipients than those targeted under PAF.

Health

PAF grantees may provide health-related supports or refer participants to supports provided through other entities. Several federal programs support relevant health care services but serve broader populations. For example, the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Services Block Grant Program aims to ensure that quality health care is provided to mothers and children, particularly those with low incomes. Similarly, Medicaid is a state-federal program that provides health insurance to low-income populations. One of the Medicaid eligibility pathways is available for pregnant women, and provides health care during pregnancy and 60 days postpartum.

Issues for Congress

If Congress considers reauthorizing the PAF program beyond FY2019, it may look to the impact evaluation discussed above to determine how well the program is meeting participants' needs. Early evidence indicates that the program may be helping to keep pregnant and parenting students in the District of Columbia attending and graduating from high school. Additional findings are forthcoming, and could help to inform policymakers further about PAF's efficacy.

Relatedly, Congress may also consider whether the program should play a role in building the evidence base for programming that supports participants. In nearly all PAF funding announcements, HHS has specified that grantees should provide services that are evidence-informed or evidence-based.48 A study of PAF grantees in the second and third cohorts found that nearly all grantees used evidence-based models, most commonly those for home visiting and parenting education; however, some grantees reported challenges with finding programming more narrowly tailored to the expectant and parenting population, even among existing evidence-based models.49

One potential reauthorization question is whether the PAF statute should have more parameters for how the program is to be carried out. As written, the statute requires each grantee to submit a report to HHS that includes information on subgrantee expenditures and performance, based on performance standards established by the grantee. The law does not provide further directives about how subgrantees should be monitored, and whether subgrantees or grantees are to meet specified performance outcomes for individuals or the program more broadly. While HHS has provided instructions about oversight via the grant announcements, these could change from one grant cycle to the next. Congress may consider whether the statute should have more explicit guidance about how HHS and grantees are to conduct oversight. Further, given the variety of services that can be provided in the program—from health and education supports to case management—Congress might examine whether the program should have uniform definitions of service categories and whether HHS should establish criteria for determining whether grantees and subgrantees have met the goals of the program.

Congress may also consider whether to establish guidelines for how the PAF program should interact with other, similar federal programs. As part of the process evaluation for the program, PAF recipients reported that they have used assessments from other programs and have attempted to coordinate with other programs to avoid duplication. In addition, some grantees reported in the process evaluation that they leveraged other public and private supports to bolster their PAF programming. Examples include funding from a governor's infant mortality budget, state general funds, and training and technical assistance provided through other federal programs, such as the MIECHV program.50 Given the similarities with other federal programs, Congress might consider whether the PAF law should require or encourage more formal linkages with such programs (e.g., through referrals to these programs, or needs assessments that are coordinated across programs) and whether the program should include directives about coordinating and reporting on funds from other federal programs.

Finally, Congress may be interested to learn more about whether PAF has assisted grantees in expanding and sustaining support for participants, or whether services were discontinued after the PAF funding period ended. This might be especially relevant for cohort 3 grantees, whose funding period was shortened from five to three years. HHS' research on a sample of former PAF grantees found that they have generally been able to continue services even after PAF funding ended. These grantees reported that they diversified their federal and other funding sources and created strong partnerships with other key stakeholders in their communities.51

Appendix. PAF Funding by Cohort and PAF Grant Categories

|

Cohort and Years |

Jurisdictions that Received Funding |

|

1 |

15 states (including DC) and 2 tribal entities: AK, CA, CT, DC, IN, MA, MN, MT, NM, NC, OR, TN, VT, VA, WA, Choctaw Nation of OK, and Inter-Tribal Council of MI, Inc. |

|

2 |

17 states and 3 tribal entities: CA, CT, MA, MI, MN, MT, NM, NC, NJ, OR, NY, SC, WA, WI, Choctaw Nation of OK, Confederate Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and Riverside-Bernardino County Indian Health Inc. in CA. |

|

3 |

3 states: MO, VT, and MS. |

|

4 |

15 states and 1 tribal entity: CA, IA, KS, MA, MI, MN, NJ, NY, OK, OR, PA, SC, VA, WA, WI, and Riverside- Bernardino County Indian Health Inc. in CA. |

|

5 |

23 states and 1 tribal entity: AL, AZ, CA, CT, KS, MD, MS, MI, MN, MS, MT, NE, NM, NY, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, VA, WA, WI, and United Indian Health Services, Inc. in CA. |

Source: Information compiled by CRS. See HHS, OASH, OAH, "Current Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) Grantees," for the list of cohort 5 grantees. See HHS, FY 2019 General Departmental Management Congressional Justification, p. 137.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Victoria L. Elliott, Analyst in Health Policy, helped lay the groundwork for this report. Paulo Ordoveza, Visual Information Specialist, assisted with the figures in the report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

The PAF authorizing statute refers to "pregnant and parenting students, fathers, or spouses" and "pregnant women" who are victims of domestic violence and related violence. This report refers to individuals eligible for PAF as the "expectant and parenting population" or "participants." The statute is at 42 U.S.C. §18201-18204. The program does not have accompanying regulations. |

| 2. |

Under the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-177), as amended, this mandatory funding is annually subject to sequestration as applied to nonexempt, nondefense accounts. This has resulted in PAF funding levels of $23.7 million (FY2013), $23.2 million (FY2014 and FY2015), $23.3 million (FY2016 and FY2017), and $23.5 million (FY2018). For further information on sequestration, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 3. |

This is based on information from 20 grantees that received funding from FY2013-FY2017. Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, Mathematica Policy Research, for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health (OASH), Office of the Adolescent Health (OAH), updated in February 2018 (hereinafter, Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth). |

| 4. |

The Casey amendment was SA 3098 and was proposed to amendment SA 2786. See U.S. Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 155 (December 9, 2009), pp. S12762 and S12825-S12826. Senator Amy Klobuchar cosponsored the amendment. |

| 5. |

H.R. 3590 was introduced as the Service Members Home Ownership Tax Act of 2009, and was passed by the House on October 8, 2009. The PAF language was included in SA 3276 to SA 2786, an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 3590, on December 22, 2009. See U.S. Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, vol. 155 (December 19, 2009), pp. S13503-S13504. |

| 6. |

The PAF authorizing law does not address abortion. A recent program grant announcement specifies that women served under the program may not be referred for abortion services. See HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001. |

| 7. |

Senator Bob Casey, "Faith Leaders Support Casey Alternative," press release, December 18, 2009, https://www.casey.senate.gov/newsroom/releases/faith-leaders-support-casey-alternative. |

| 8. |

Joyce A. Martin, et al., "Births: Final Data for 2017," HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics Report, vol. 67, no. 8, November 7, 2018. The CDC also tracks births for youth aged 10 to 14; however, their birth rate has been much lower than the rate of births for older teens. The birth rates were 0.2 births per 1,000 youth aged 10 to 14 and 18.8 births per 1,000 youth aged 15 to 19 in 2016. |

| 9. |

See CRS Report R45184, Teen Birth Trends: In Brief. |

| 10. |

Ibid. |

| 11. |

Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy), Preventing Teen Pregnancy Through Outreach and Engagement: Tips for Reaching Older Teens through Community Colleges, no date. |

| 12. |

Domestic violence is also referred to as "intimate partner violence." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the lead federal agency that addresses public health issues, refers to intimate partner violence as physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression by a current or former intimate partner. See CDC, "Intimate Partner Violence: Definitions." The term "victim" is sometimes used interchangeably with "survivor." Related terms are also discussed in CRS Report R42838, Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA): Background and Funding. |

| 13. |

Jeanne L. Alhusen et al., "Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes," Journal of Women's Health, vol. 24, no. 1 (January 2015) (hereinafter, Jeanne L. Alhusen et al., "Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes"). |

| 14. |

Sheri Madigan et al., "Association Between Abuse History and Adolescent Pregnancy: A Meta-Analysis," Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 55, no. 2 (August 2014). |

| 15. |

Jeanne L. Alhusen et al., "Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes." |

| 16. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, p. 5. |

| 17. |

For example, under the MIECHV program, states (including DC and the territories) and Indian tribes are required to conduct a needs assessment to identify communities in the jurisdiction with selected risk factors, determine the quality and capacity of existing programs or initiatives for home visiting programs, and determine the jurisdiction's capacity for providing substance abuse treatment and counseling to families and individuals in need of such support. The needs assessment must take into account, and coordinate with, selected other federal needs assessments. 42 U.S.C. §711(b)(2). |

| 18. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, pp. 6-7. |

| 19. |

42 U.S.C. §18201(7). The term "state" includes DC; any commonwealth, possession, or other territory of the United States, and any Indian tribe or reservation. |

| 20. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001. |

| 21. |

The state public health department administers PAF funds in 17 of the 23 jurisdictions that are funded as part of cohort 5 that began in 2018. The 17 states are CA, KS, MD, MA, MI, MN, MS, MT, NE, NY, OK, OR, PA, RI, VA, WA, and WI. In 3 of the 17 states, the department of health also includes the state health and human services agency (MI, MT, NE). NY coadministers the grant with Health Research Inc., a nonprofit organization that partners with the state on public health research. Four other states (AL, AZ, CT, and NM) administer the program through another state office or agency, such as the department of education. SC operates its program through a nonprofit organization, the Children's Trust Fund of South Carolina, which is authorized under state law and seeks to prevent child abuse and neglect. The single tribal entity is United Indian Health Services, Inc. in CA. See HHS, OASH, OAH, Current Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) Grantees. |

| 22. |

See 42 U.S.C. §18201(4). |

| 23. |

The grant application specifies that each site supported under this purpose area is expected to carry out the activities described in this paragraph. The statute provides that these activities are optional. |

| 24. |

42 U.S.C. §18203(b)(3). |

| 25. |

The term "violence" means actual violence and the risk or threat of violence. The terms are defined at 42 U.S.C. §18201. |

| 26. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001, pp. 15-16. |

| 27. |

Ibid, p. 19. |

| 28. |

42 U.S.C. §18203(b)(5) and (c). |

| 29. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001, pp. 75-80. HHS also provides guidance on performance outcomes. An older version of this guidance is online at HHS, OAH, "PAF Performance Measures," no date. See also, HHS, OASH, OAH, The Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF): Performance in the Second Year of Implementation, March 2016 (hereinafter, HHS, OASH, OAH, The Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF): Performance in the Second Year of Implementation). Appendix B includes the performance measures. |

| 30. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001, p. 26, pp. 39-40, and p. 68. |

| 31. |

Ibid., p. 16, pp. 32-33. |

| 32. |

Ibid., p. 16. |

| 33. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, p. 15. |

| 34. |

Ibid. No further information is available about the reasons for the shortened period. |

| 35. |

HHS, FY 2019 General Departmental Management Congressional Justification, p. 137. |

| 36. |

Information in this section is drawn from HHS, OASH, OAH, The Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF): Fiscal Year 2016, April 2017. Percentages in each category may not total 100% due to rounding. |

| 37. |

The number of participants in each of the first three categories (high schools/community service centers; IHEs; and via partnerships with state attorney general's offices) totals 15,707. HHS does not appear to have reported on the number of individuals reached through public awareness activities. Unlike for individuals served in high schools/community service centers, HHS does not include outcome data for the categories of individuals served via IHEs or via partnerships with state attorney general's offices. |

| 38. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Announcement and Application Instructions, Announcement Number AH-SP1-17-001. |

| 39. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, Announcement of Anticipated Availability of Funds for Support for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Women, Fathers, and Their Families, Funding Opportunity Number AH-SP1-18-001. |

| 40. |

In guidance, only the terms "education support services" and "health care services" appear to be defined. "Education support services" includes tutoring services, credit recovery, individualized graduation plans, flexible scheduling, homebound instruction for extended absences, general education diploma (GED) registration and enrollment, school re-enrollment assistance, college application assistance, financial aid resources or application assistance, and dropout prevention services. "Health care services" includes prenatal care, postpartum care, reproductive health, pediatric care, and primary care. See, HHS, OASH, OAH, The Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF): Performance in the Second Year of Implementation. |

| 41. |

Ibid. These service-related terms are defined earlier in the report. |

| 42. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, "Pregnancy Assistance Fund (PAF) Evaluation." |

| 43. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth. |

| 44. |

HHS, OASH, OAH, "Understanding the Effectiveness of Programs for Expectant and Parenting Teens," Positive Adolescents Future Fact Sheet, March 2017. In addition, the impact evaluation includes a program in Texas; however, Texas has not received funding under the PAF program. |

| 45. |

Subuhi Asheer et al., Positive Adolescent Futures Study, Raising the Bar: Impacts and Implementation of the New Heights Program for Expectant and Parenting Teens in Washington, DC, Mathematica for HHS, OASH, OAH, April 2017. The sample involved about 11,000 youth, of whom over 500 were parenting. |

| 46. |

U.S. Department of Education, Child Care Access Means Parents in School Program: Awards. Although pregnant and parenting students of high school age are generally eligible for programs under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the act does not focus on this population. |

| 47. |

Robert G. Wood and Ellen Kisker, Steps to Success: Implementing a Home Visiting Program Designed to Prevent Rapid Repeat Pregnancies Among Adolescent Mothers, Mathematica Policy Research for HHS, Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Office of Research, Planning and Evaluation (OPRE), OPRE Brief #2017-81, 2018. |

| 48. |

In this context, "evidence-informed" generally refers to new or emerging programs that are based in theory and have been implemented at least on a small scale. "Evidence-based" generally refers to programs that have been rigorously evaluated and show key impacts on certain outcomes. |

| 49. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth. |

| 50. |

Ann E. Person et al., The Pregnancy Assistance Fund: Launching Programs to Support Expectant and Parenting Youth, pp. 15-16. |

| 51. |

Subuhi Asheer et al., Sustaining Programs for Expectant and Parenting Teens, Mathematica Policy Research for HHS, OAH, May 2017. |