United States Special Operations Command Acquisition Authorities

United States Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is the Unified Combatant Command responsible for training, doctrine, and equipping all special operations forces of the Army, Air Force, Marine Corps and Navy. SOCOM has been granted acquisition authority by Congress to procure special operations forces-peculiar equipment and services.

There is a perception among some observers and officials that SOCOM possesses unique acquisition authorities that allow it to operate faster and more efficiently than the military departments.

SOCOM possesses unique acquisition authorities when compared with other combatant commands. However, SOCOM is generally held to the same statutory and regulatory acquisition requirements as the military departments and, in some instances, has less acquisition authority. There are no unique authorities granting SOCOM exemptions or waivers from acquisition requirements. But when it comes to acquisition, SOCOM is different than the military services.

SOCOM’s acquisition performance is influenced by the size of the organization, focus of its acquisitions (which are limited to special operations-specific goods and services), and smaller size of its programs in terms of both scope of development and dollars. The current SOCOM Acquisition Executive reiterated these points when he reportedly stated that “[SOCOM’s] ability to move relatively fast is a function of scale.”

These factors allow SOCOM to maintain the majority of its procurement programs at Category III levels, thereby reducing the oversight and bureaucratic burden, and allowing critical Milestone Decision Authority to remain at lower levels within the Command. As a result, some observers have argued that the SOCOM acquisition process is often capable of executing faster (and failing faster), maintaining closer communication between leadership and users, being more nimble, and fostering a culture willing to assume more risk.

United States Special Operations Command Acquisition Authorities

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- SOCOM Acquisition Authorities and Organization

- Legislative Framework

- SOCOM Acquisition Chain of Command

- SOCOM vs. Military Department Acquisition

- Legislative Framework

- Regulatory Framework

- Comparison of Acquisition Programs

- How SOCOM's Size Can Promote a Culture of Agility and Innovation

- Issues for Congress

- Can SOCOM Attributes be Replicated by the Military Services?

- Should Authorities Available to the Military Departments be Extended to SOCOM?

Figures

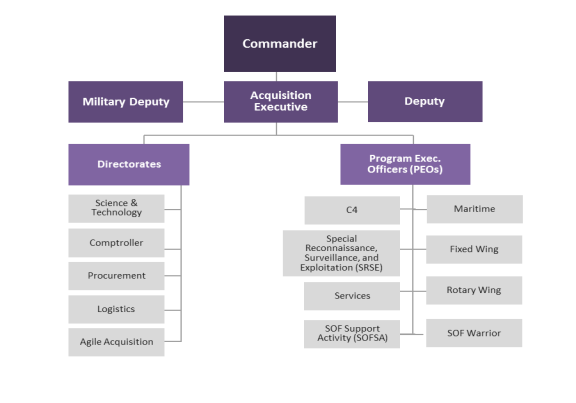

- Figure 1. SOF AT&L Organization Chart

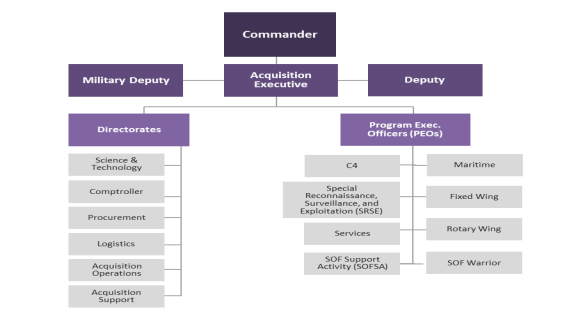

- Figure B-1. SOCOM SOF AT&L Chain of Command

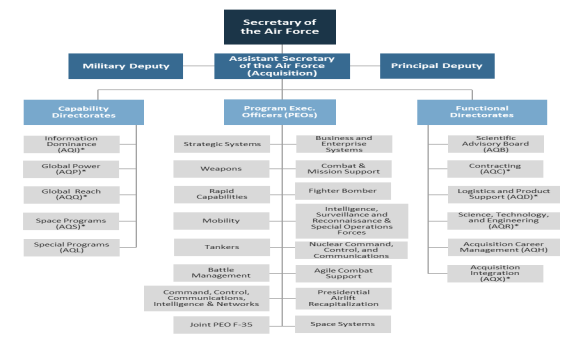

- Figure B-2. U.S. Air Force Secretary of the Air Force/Acquisitions Chain of Command

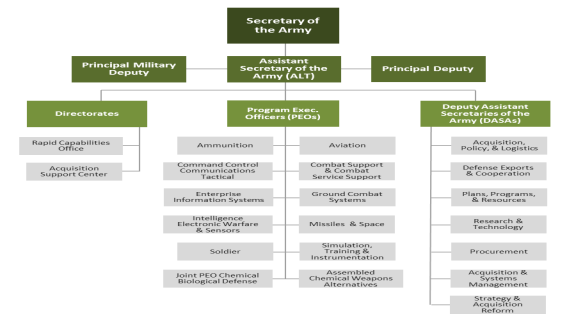

- Figure B-3. U.S. Army Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisitions, Logistics and Technology) Chain of Command

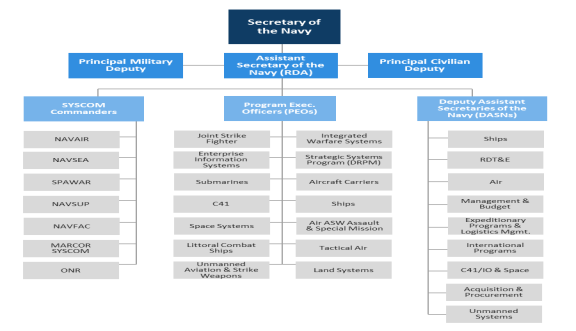

- Figure B-4. US Navy Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Research, Development & Acquisition) Chain of Command

Tables

Summary

United States Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is the Unified Combatant Command responsible for training, doctrine, and equipping all special operations forces of the Army, Air Force, Marine Corps and Navy. SOCOM has been granted acquisition authority by Congress to procure special operations forces-peculiar equipment and services.

There is a perception among some observers and officials that SOCOM possesses unique acquisition authorities that allow it to operate faster and more efficiently than the military departments.

SOCOM possesses unique acquisition authorities when compared with other combatant commands. However, SOCOM is generally held to the same statutory and regulatory acquisition requirements as the military departments and, in some instances, has less acquisition authority. There are no unique authorities granting SOCOM exemptions or waivers from acquisition requirements. But when it comes to acquisition, SOCOM is different than the military services.

SOCOM's acquisition performance is influenced by the size of the organization, focus of its acquisitions (which are limited to special operations-specific goods and services), and smaller size of its programs in terms of both scope of development and dollars. The current SOCOM Acquisition Executive reiterated these points when he reportedly stated that "[SOCOM's] ability to move relatively fast is a function of scale."

These factors allow SOCOM to maintain the majority of its procurement programs at Category III levels, thereby reducing the oversight and bureaucratic burden, and allowing critical Milestone Decision Authority to remain at lower levels within the Command. As a result, some observers have argued that the SOCOM acquisition process is often capable of executing faster (and failing faster), maintaining closer communication between leadership and users, being more nimble, and fostering a culture willing to assume more risk.

Introduction

In recent years, a number of observers have suggested that United States Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is generally more effective at acquisitions than the U.S. military departments, in part because of the perception that SOCOM has unique acquisition authorities.1 This report describes SOCOM's acquisition authorities for unclassified acquisition programs and compares these authorities to those granted to the military departments. It also compares the military departments' and SOCOM's chains of command, and the scope of acquisition activity and program oversight for those organizations. Finally, the report explores whether SOCOM has unique characteristics that influence how it conducts acquisition.

SOCOM Acquisition Authorities and Organization

The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-433) reorganized DOD's command and control structure, in part by establishing the current construct and authorities of combatant commands. There are 10 combatant commands: 6 geographic and 4 functional commands.2

SOCOM possesses unique acquisition authorities when compared with other combatant commands.3 SOCOM was established and granted its own acquisition responsibilities in the Fiscal Year (FY) 1987 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) (P.L. 99-661). SOCOM was the first combatant command endowed with acquisition authority and its own budget line for training and equipping its forces.4 The FY2016 NDAA (P.L. 114-92) granted limited acquisition authority to the U.S. Cyber Command, making CYBERCOM the second command to have current independent acquisition authority.5 However, SOCOM's acquisition authority is more expansive.

Legislative Framework

Title 10 U.S.C. Section 164(c) grants SOCOM authority to

- validate and establish priorities for requirements;

- ensure combat readiness;

- develop and acquire special operations-peculiar equipment and acquire special operations-peculiar material, supplies, and services; and

- ensure the interoperability of equipment and forces.

These authorities are applicable only to "special operations-peculiar items."6 If SOCOM wants to acquire a weapon system that is not special operations specific, the acquisition must be executed through one of the military departments. The military services are responsible for funding certain types of SOCOM training, service-common equipment, and professional services.7 For example, the Air Force provides SOCOM with C-130s and the Army provides the ammunition for service-common weapons to include the M4.8 SOCOM, in turn, can modify these systems to special operations-specific requirements.9

Pursuant to statute (10 U.S.C. 167), SOCOM has an Acquisition Executive who has the authority to10

- negotiate memoranda of agreement with the military departments to carry out the acquisition of equipment, material, and supplies;

- supervise the acquisition of equipment, material, supplies, and services;

- represent the command in discussions with the military departments regarding acquisition programs for which the command is a customer; and

- work with the military departments to ensure that the command is appropriately represented in any joint working group or integrated product team regarding acquisition programs for which the command is a customer.

These statutory authorities enable SOCOM to manage and oversee its acquisition programs, to negotiate with the military departments for systems to be provided to SOCOM, and to have input into military department acquisitions when SOCOM will be one of the customers of the acquisition program.

SOCOM Acquisition Chain of Command

Special Operations Force Acquisition, Technology and Logistics (SOF AT&L) is the organization within SOCOM that leads internal major procurement efforts. The SOCOM Commander is directly responsible for all portions of the command and the Acquisition Executive (AE) reports directly to the Commander. Falling under the AE are the Program Executive Offices (PEOs) and Directorates. This direct chain of command allows for rapid communication on purpose, intent, and decisionmaking (see Figure 1).11 The structure's design is similar to that of the other services, which also follow a Secretary/Commander-AE-PEO-PM structure (see Appendix B). One difference is that in the services, the Service Acquisition Executive reports to the Service Secretary, whereas in SOCOM the AE reports to the Commander.

|

|

Source: CRS version graphic based on SOCOM website: https://www.socom.mil/SOF-ATL/PublishingImages/OrgChart.jpg. |

Internal to SOCOM, the Commander generally delegates acquisition decision authority to the Acquisition Executive. The Acquisition Executive in turn generally further delegates the majority of Milestone Decision Authority (MDA) to the PEOs. SOCOM officials have asserted that this delegation enables more rapid decisionmaking and accelerates the acquisition process.12

SOCOM vs. Military Department Acquisition

The method SOCOM uses for acquisitions is similar to the acquisition processes used by the military services: they share the same general statutory and regulatory framework; training and education opportunities (i.e., access to Defense Acquisition University and National Defense University); and DOD oversight regime.

However, there are also significant differences, many of which relate to the size and scope of SOCOM and its authorities. Table 1 summarizes select similarities and differences.

|

SOCOM |

Military Departments |

|

|

SIMILARITIES |

||

|

Acquisition Authority |

Title 10 |

Title 10 |

|

Milestone Decision Authority (Major Defense Acquisition Program)a |

SOF Acquisition Executive |

Service Acquisition Executive |

|

Milestone Decision Authority (Major System)b |

SOF Acquisition Executive |

Service Acquisition Executive |

|

Organization Structure |

Program Managers Program Executive Officers Acquisition Executive |

Program Managers |

|

DIFFERENCES |

||

|

Procurement Appropriations (billions of dollars) |

$2 |

$22-$56c |

|

Number of CAT I Programs |

0 |

150 |

|

Acquisition Personnel |

~500 |

~35,000-57,000d |

|

Scope of Authority |

SOF Specific Acquisitions |

All Departmental Acquisitions |

Source: Data based on publicly available acquisition information and on DOD Instruction 5000.02, Operations of the Defense Acquisition System, August 10, 2017.

a. A Major Defense Acquisition Program (MDAP) is a DOD acquisition program that is not a highly sensitive classified program (as determined by the Secretary of Defense) and that is designated by the Secretary of Defense as an MDAP; or in the case of a program that is not for the acquisition of an automated information system (either a product or a service), that is estimated by the Secretary of Defense to require an eventual total expenditure for research, development, test, and evaluation of more than $300 million (based on FY1990 constant dollars) or an eventual total expenditure for procurement, including all planned increments or spirals, of more than $1.8 billion (based on FY1990 constant dollars).

b. A Major System is a program where the total expenditures for research, development, test, and evaluation for the system are estimated to be more than $115 million (based on FY1990 constant dollars); or the eventual total expenditure for procurement of the system is estimated to be more than $540 million (based on FY1990 constant dollars).

c. Service FY17 actual procurement appropriations (in billions): Air Force—$47.0; Army—$22.4; Navy—$55.8. Derived from Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), PROCUREMENT PROGRAMS (P-1), Department of Defense, February 13, 2018.

d. Department of Defense, ACQUISITION WORKFORCE STRATEGIC PLAN: FY2016 - 2021, Department of Defense, December 2016, p. 12, http://www.hci.mil/docs/DoD_Acq_Workforce_Strat_Plan_FY16_FY21.pdf. Are USSOCOM Authorities Unique?

Legislative Framework

SOCOM's statutory acquisition authorities are more limited than those of the military departments. SOCOM acquisition authority is restricted to Special Operations-specific items, while the military services have the authority to acquire any necessary goods and services. When SOCOM does exercise its authority, it adheres to the same oversight and documentation requirements as the services. As James Smith, the current SOCOM Acquisition Executive, reportedly stated:

We are absolutely subject to all of the same oversight and policy as the rest of DOD. Our workforce operates professionally within the same DOD 5000 directives, the same Federal Acquisition Regulation and the same Financial Management Regulation. I think it's important to understand that.... Give credit to our acquisition workforce for the results they achieve, and you might dismiss using USSOCOM as a benchmark for how to do acquisition under the assumption that we're somehow "different."13

In some instances, SOCOM may in fact have fewer acquisition authorities and flexibilities than the military departments, as in cases where statute specifically provides acquisition authorities to the military departments. For example, 10 U.S.C. 2216 established a Defense Modernization Account and granted authority for its use to the Secretary of Defense and the Secretaries of the military departments. Additionally, the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328, §2447d) granted a new reprogramming authority, referred to as a special transfer authority, to the Secretaries of the military departments in an effort to expedite the selection of prototype projects for production and rapid fielding.14

The FY2018 NDAA (P.L. 115-91, §809) required the Secretary of Defense to submit a report on the acquisition authorities available to the military departments that are not available to SOCOM, and to "determine the feasibility and advisability of providing such authorities to the Commander of the United States Special Operations Command."15

Regulatory Framework

The regulations governing acquisition are found in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) and the Defense Acquisition Regulations Supplement (DFARS). The DFARS provides DOD-specific regulations that government acquisition officials—and those contractors doing business with DOD—must follow in the procurement process for goods and services.16

SOCOM is not referenced or discussed in the FAR; the DFARS includes a brief definitional reference to SOCOM, defining it as a defense agency for the purposes of the DFARS.17

Each military service and many DOD components also have their own acquisition regulatory supplement that provides unique acquisition guidance. For example, the Army maintains the Army Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplements (AFARS) and the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) maintains the DLA Directive. SOCOM has its own supplement to the DFARS, known as the SOCOM Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (SOFARS). SOFARS Part 5601.101 defines the supplemental regulation's purpose as "provid[ing] the minimum essential implementation of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), and DOD FAR Supplement (DFARS)." SOCOM has also issued USSOCOM Directive 70-1, which seeks to set forth an overarching construct for acquisition, within the constraints of the FAR, DFAR, and SOFARS.18

There are no unique authorities granting SOCOM exemptions or waivers from acquisition requirements. The Office of the Secretary of Defense's issuances establishing policy, defining authorities, and assigning responsibility for acquisitions across all military services and defense agencies include

- The Defense Acquisition System (DOD Directive 5000.01),

- Operation of the Defense Acquisition System (DOD Instruction 5000.02), and

- Defense Acquisition of Services (DOD Instruction 5000.74).

As such, SOCOM acquisition personnel are bound by and act with the same freedoms and restrictions as the military services and defense agencies. For example, all large DOD acquisition programs are given an Acquisition Category (ACAT) designation based on dollar figures and program scope.19 These designations determine the level of oversight required for the program. SOCOM and the military departments adhere to the same oversight standards and dollar threshold for categorizing programs. (For more information on program categories and dollar thresholds, see Table A-1.)

Comparison of Acquisition Programs

According to officials, SOCOM has a total of six programs that exceed the category II dollar thresholds.20 Currently, the Silent Knight Radar program, which is developing a SOF-common terrain following/terrain avoidance radar system for use in SOF fixed wing and rotary wing aircraft, is one of SOCOM's largest with a total estimated procurement cost through FY2023 of at $391.7 million.21 FY2017 actual procurement funding budget for the program was $34 million.

In comparison, the military services have numerous major programs with significantly higher procurement appropriations. The Navy's 2017 appropriation for the Virginia Class submarine program ($5.39 billion) is 250% larger than SOCOM's entire FY2017 procurement appropriation ($2.08 billion). In FY2017, the SOCOM procurement appropriation was 1.5% of DOD's total procurement appropriation of $132.2 billion. See Table 2 for a comparison of the largest programs in the military services to that of SOCOM.

|

Service |

Program |

FY2017 Appropriation ($ in Millions) |

ACAT Type |

|

SOCOM |

Silent Knight Radar |

$34.0 |

II |

|

Air Force |

KC-46A Tanker Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle B-21 Raider |

$3,101.1 $1,634.8 $1,290.3 |

I I I |

|

Army |

Ah-64E Apache: Remanufacture/New Build UH-60 Black Hawk Abrams Tank Modifications/Upgrades |

$1,363.6 $1,305.9 $886.6 |

I I I |

|

Navy |

SSN 774 Virginia Class Submarine DDG 51 Arleigh Burke Class Destroyer CVN 78 Gerald R. Ford Class Nuclear Aircraft Carrier |

$5,394.6 $3,894.1 $2,752.1 |

I I I |

Sources: SOCOM figures from DOD FY2019 Budget Estimates and Service Amounts from Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller); Air Force, Army, and Navy figures from Chief Financial Officer February 2018 Program Acquisition Cost by Weapons System.

The different size and scope of the acquisition efforts result in SOCOM having a substantially smaller acquisition workforce than the services. SOCOM's acquisition workforce consists of approximately 500 civilian and military personnel, less than 1% of the total DOD acquisition workforce of 156,000.22 A number of analysts and government officials have argued that SOCOM benefits from its size relative to the military services.23 The current SOCOM Acquisition Executive also reiterated this point when he reportedly stated that "[SOCOM's] ability to move relatively fast is a function of scale."24

How SOCOM's Size Can Promote a Culture of Agility and Innovation

When compared to the military services, SOCOM can be seen to operate like a small business. Many analysts argue that small businesses and organizations can be more nimble, more innovative, and more adaptable than large enterprises.25 As Sir Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin Group, reportedly stated, "Small businesses are nimble and bold and can often teach much larger companies a thing or two about innovations that can change entire industries."26

A number of analysts also argue that small organizations can be more effective in communication, innovation and redesign, customer service, and risk-taking; while others point out that small organizations can be more agile and less bureaucratic.27 A 2004 congressional report identified SOCOM's unique size, culture, and close proximity to the warfighter as factors that can contribute to more effective acquisitions. According to the congressional report:

The successful use of the Special Operations Command acquisition authority below the acquisition category (ACAT) 1 level illustrates the transformation benefits of having a joint buyer, close to the user, maintain a streamlined acquisition process to deliver low dollar threshold systems rapidly to the warfighter.28

In discussing the SOCOM acquisition culture and the benefits of a flatter organization, a number of current and former SOCOM officials have stated that the lack of bureaucratic overhead allows the organization to identify emerging issues, modify programs that are underway, or, in certain cases, divest from programs more rapidly.29 This point has been highlighted by James "Hondo" Geurts, current Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition (and former SOCOM Acquisition Executive).30

Another factor that potentially enables SOCOM's culture of innovation and risk-taking in its acquisition programs is its general ability to execute programs below statutory and regulatory dollar figures that require more rigorous oversight. Because SOCOM programs have lower dollar thresholds, its programs do not generally receive the same level of scrutiny brought to bear on the more expensive and higher-profile programs of the military services.31

For example, the Nunn-McCurdy Act (10 U.S.C. §2433) requires DOD to report to Congress when an MDAP experiences cost overruns of 15% or more.32 There are currently more than 150 MDAPs in DOD; many of these programs have a larger budget in a single year than SOCOM's entire procurement budget for FY2017. If SOCOM's current CAT II program (Silent Knight Radar) experienced 100% cost growth (from approximately $391 million to $782 million), it would still not require a Nunn-McCurdy notification to Congress. In comparison, the cost growth associated with the procurement of the CVN-78 Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier ($1.4 billion) was approximately 70% of SOCOM's entire FY2017 procurement budget ($2.0 billion).33 Some analysts believe that these lower dollar thresholds allow SOCOM to operate below the radar, thus enabling a more nimble acquisition process and a culture that promotes "failing fast."34

Despite these perceived organizational advantages, SOCOM has experienced challenges in executing its acquisition programs. The Advanced SEAL Delivery System Program, intended to develop a covert submersible insertion vehicle, was documented by both the Government Accountability Office and RAND as experiencing considerable cost, schedule, and performance issues before finally being cancelled in 2009.35 This program illustrates observers' argument that it is not only the ability to succeed faster, but also to fail faster and adapt requirements or acquisition strategies faster, that gives SOCOM the ability to execute acquisitions more efficiently and effectively.

Additionally, SOCOM's statutory restriction to procure strictly SOF-peculiar equipment, modifications, and services enables a more focused, operations-oriented acquisition culture. In a National Defense interview, James Smith reportedly stated the following:

Our direct relationship to USSOCOM for the acquisition of only services and equipment that are unique to special operations gives us three primary advantages. First, USSOCOM is a combatant command with an extremely relevant ongoing mission. We're fully co-located and integrated with the staff here. We have a firsthand understanding of priorities and urgency that gives us a different appreciation for schedule emphasis. It's not a cliché to say that our operators will often accept the "80 percent" solution if we can get that solution into the fight sooner.36

The services, on the other hand, have a much broader acquisition mandate, including the acquisition of business systems, weapon procurement programs that must be integrated into joint operations, extensive logistic contracts, large- and small-scale platforms, and substantially more complex systems with multiple technologies and capabilities. This broader acquisition portfolio requires the services to manage acquisition programs across domains, using multiple acquisition processes, and to use different acquisition competencies.

Issues for Congress

Can SOCOM Attributes be Replicated by the Military Services?

SOCOM benefits from being a smaller organization with a more focused mission set and limited scope of acquisition authorities. Other SOCOM attributes, such as delegating more decisionmaking to lower levels and promoting a more risk-taking culture, may be transferable to the services. A number of current senior acquisition officials in the military services recently served in SOCOM and appear to be promoting more delegation of authority and cultural risk-taking in the services, including General Paul Ostrowksi, formerly a SOCOM PEO and currently the Principal Military Deputy to the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisition, Logistics and Technology), and James Guerts, formerly the SOCOM Acquisition Executive and currently the Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Research, Development and Acquisition). One potential issue for Congress may include the following:

- To what extent do current acquisition-related laws and regulations promote or inhibit a more efficient, less bureaucratic, and more balanced approach to risk in acquisitions?

Should Authorities Available to the Military Departments be Extended to SOCOM?

In some instances SOCOM has fewer acquisition authorities than the military departments. This occurs where legislation grants acquisition authorities or flexibilities to the military departments. The definition of military departments, codified in 50 U.S.C. 3004, does not include SOCOM. As a result, SOCOM may not receive new acquisition authorities provided by Congress and must work through the Secretary of Defense to obtain these authorities or seek a legislative change, potentially resulting in lost opportunities for SOCOM in its acquisition efforts. Potential associated issues for Congress may include the following:

- Based on the DOD report on acquisition authorities required in the 2018 NDAA, should additional acquisition authorities should be granted to SOCOM?

- Should the definition of military departments as they relate to acquisitions be modified to include SOCOM?

|

ACAT |

Reason for ACAT |

|

|

ACAT I |

|

|

|

ACAT II |

|

|

|

ACAT III |

Does not meet criteria for ACAT II or above |

Source: CRS analysis of DOD Instruction 5000.02, Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, 2015, amended to incorporate statutory changes based on enacted legislation since issuance of the instruction.

Notes:

a. The Special Interest designation is typically based on one or more of the following factors: technological complexity; congressional interest; a large commitment of resources; or the program is critical to the achievement of a capability or set of capabilities, part of a system of systems, or a joint program. Programs that already meet the MDAP threshold cannot be designated as Special Interest.

Appendix B. Comparison of Chains of Command

|

|

Figure B-2. U.S. Air Force Secretary of the Air Force/Acquisitions Chain of Command |

|

|

Source: CRS version graphic based on SAF/AQ websites: http://ww3.safaq.hq.af.mil/Organizations/ and http://ww3.safaq.hq.af.mil/Portals/63/documents/organizations/Air%20Force%20Acquisition%20Organizations.pdf?ver=2018-01-04-141543-547. Note: * Designates Deputy Assistant Secretary equivalent positions |

|

Figure B-3. U.S. Army Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisitions, Logistics and Technology) |

|

|

Source: CRS version graphic based on ASA (ALT) website: https://www.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/502980.pdf. |

|

Figure B-4. US Navy Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Research, Development & Acquisition) |

|

|

Source: CRS version graphic based on ASN (RDA) website: http://www.secnav.navy.mil/rda/Pages/ASNRDAOrgChart.aspx. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Alex Haber and Jeff Jeffress, "Supporting the fight for more effectiveness in DoD Acquisitions," The Hill, March 12, 2015, http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/homeland-security/235393-supporting-the-fight-for-more-effectiveness-in-dod; Special Operations Forces, AT&L, website, http://www.socom.mil/acquisition-authority, downloaded April 17, 2018; Courtney Hacker, We wanted to know SOCOM's top priorities, so we asked the guys in charge, Bloomberg Government, March 2, 2016, https://about.bgov.com/blog/we-wanted-to-know-socoms-top-priorities-so-we-asked-the-guys-in-charge/. |

| 2. |

Functional combatant commands operate worldwide across geographic boundaries and provide unique capabilities to geographic combatant commands and the services while Geographic commands operate in clearly delineated areas of operation and have a distinctive regional military focus. The geographic commands are as follows: AFRICOM: U.S. Africa Command, CENTCOM: U.S. Central Command, EUCOM: U.S. European Command, NORTHCOM: U.S. Northern Command, INDOPACOM: U.S. Indo Pacific Command (prior to June 2018, known as Pacific Command), and SOUTHCOM: U.S. Southern Command. The functional commands are as follows: SOCOM: U.S. Special Operations Command, STRATCOM: U.S. Strategic Command, TRANSCOM: U.S. Transportation Command, and CYBERCOM: U.S. Cyber Command. (Cyber Command became a unified command on May 4, 2018.) See also CRS In Focus IF10542, Defense Primer: Commanding U.S. Military Operations, by [author name scrubbed], Defense Primer: Commanding U.S. Military Operations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

In the FY2004 NDAA (P.L. 108-136, §848), Congress granted the Secretary of the Defense the ability to delegate limited acquisition authority to the Commander of United States Joint Forces Command for a period of three years. This authority was extended, and ultimately expired September 30, 2010. |

| 4. |

Congress modified 10 U.S.C. 167 to include a major force program (MFP) category for special operations forces. An MFP is "an aggregation of program elements [PE] that reflects a force or support mission of DOD and contains the resources necessary to achieve an objective or plan." MFP-11provides appropriated funds to SOCOM to procure SOF-peculiar equipment and services required to meet its requirements. As such, Congress sets the procurement budget for SOCOM and SOCOM is not dependent on the military departments for procurement funding. The definition for MFP can be found at https://www.dau.mil/glossary/pages/2192.aspx. For more information on MFPs and PEs, see CRS In Focus IF10831, Defense Primer: Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], Defense Primer: Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

CRS is unable to confirm the extent to which CYBERCOM will have an independent budget line for train and equip. In the FY2004 NDAA (P.L. 108-136, §848), Congress granted the Secretary of the Defense the ability to delegate limited acquisition authority to the Commander of United States Joint Forces Command for a period of three years. This authority was extended, and ultimately expired September 30, 2010. |

| 6. |

Per Department of Defense Directive 5100.03, DCMO, Support of the Headquarters of Combatant and Subordinate Unified Commands, special operations-peculiar is defined as: Equipment, material, supplies, and services required for special operations missions for which there is no Service-common requirement. These are limited to items and services initially designed for, or used by, special operations forces until adopted for Service-common use by one or more Military Service; modifications approved by the Commander, SOCOM, for application to standard items and services used by the Military Services; and items and services approved by the Commander, SOCOM, as critically urgent for the immediate accomplishment of a special operations mission. |

| 7. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Special Operations Forces Opportunities Exist to Improve Transparency of Funding and Assess Potential to Lessen Some Deployments, GAO-15-571, July 16, 2015, pp. 17-18. |

| 8. |

Ibid. |

| 9. |

Section 1211(b) of the FY 1988 and 1989 NDAA (P.L. 100-180) directed the Secretary of Defense to "provide sufficient resources for the commander of the unified combatant command for special forces...to carry out his duties and responsibilities, including particularly his duties and responsibilities relating to the following functions: (1) Developing and acquiring special operations-peculiar equipment and acquiring special operations-peculiar material, supplies, and services" (emphasis added). |

| 10. |

This position was established by the 2008 NDAA (P.L. 110-181). |

| 11. |

"An Interview with the Special Operations Forces Acquisition Executive James Geurts," Armor and Mobility Magazine, May 2014. |

| 12. |

Based on CRS conversations with senior SOCOM acquisition officials and the SOCOM Acquisition Executive, June 7, 2018. |

| 13. |

Vivienne Machi, "Q&A with SOCOM's New Acquisition Executive, James Smith," National Defense, February 8, 2018, http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2018/2/8/interview-with-socoms-new-acquisition-executive-james-smith. |

| 14. |

DOD has the authority to shift funds from one budget account to another in response to operational needs. For DOD, these transfers (sometimes colloquially called reprogrammings), are statutorily authorized by 10 U.S.C §2214 (Transfer of funds: procedure and limitations), which allows the Secretary of Defense to reallocate funds for higher priority items, based on unforeseen military requirements, after receiving written approval from the congressional defense committees. Specific authorities, such as the special transfer authority established by the FY2017 NDAA, or other limits to transfer or reprogramming authorities have also been added to these general authorities through provisions in annual defense authorization and appropriation acts. |

| 15. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 , Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 2810, 115th Cong., 1st sess., November 2017, H.Rept. 115-404 (Washington: GPO, 2017). |

| 16. |

DCAA Website: http://www.dcaa.mil/home/dfars (accessed May 4, 2018). |

| 17. |

DFARS 202 Subpart 202.1—Definitions. |

| 18. |

US Special Operations Command Directive 70-1 provided by email on August 15, 2017. |

| 19. |

Acquisition programs generally fall into one of two types: Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAP) and Major Systems (MS). See table notes a and b to Table 1 for additional discussions of the statutory requirements for an acquisition program to be designated an MDAP or an MS. |

| 20. |

Based on CRS conversations with senior SOCOM acquisition officials and the SOCOM Acquisition Executive, June 7, 2018. |

| 21. |

Department of Defense, Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Budget Estimates: United States Special Operations Command, February 2018, p. 7, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2019/budget_justification/pdfs/02_Procurement/14_USSOCOM_FY19%20PB_%200300_PROC_J-Book.pdf. |

| 22. |

GAO Report 17-332 Defense Acquisition Workforce, pg. 9. |

| 23. |

Eric L. Mikkelson, "Is SORDAC'S Rapid Acquisition Process Best Prepared to Field Solutions for Future Technological Challenges?" (Master's Thesis, Air University, 2016), p. 6. This point was reiterated to CRS by a number of current and former SOCOM officials in meetings spanning May-June, 2018. |

| 24. | |

| 25. |

Devra Gartenstein, "Advantages Small Companies Have Over Large Companies," Chron, April 5, 2018, http://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-small-companies-over-large-companies-23667.html. (accessed May 4, 2018). |

| 26. |

Jack Preston, Virgin, July 1, 2014, https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/start-ups-join-richard-branson-30-year-brainstorm. |

| 27. |

Michael Mazzeo, Paul Oyer, and Scott Schaeffer, "What small businesses do better than corporate America," Fortune, June 10, 2014, http://fortune.com/2014/06/10/what-small-businesses-do-better-than-corporate-america/ , (accessed on May 7, 2018); Larry Alton, "5 Competitive Advantages Startups Have Over Big Business," Entrepreneur, June 17, 2015, https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/247412, (accessed May 7, 2018). |

| 28. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Armed Services, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2004, Report to Accompany S. 1050, 108th Cong., 1st sess., May 13, 2003, S.Rept. 108-46, pp. 342-343. |

| 29. |

Interview with SOCOM leadership, 7 June 2018, and with former acquisition officials, May-June 2018. |

| 30. |

James "Hondo" Geurts reportedly stated "SOF acquisitions are accomplished in 1/10th the time, 1/10th the cost, 1/20th the people." James "Hondo" Geurts, "Special Operations Research, Development, & Acquisition Center (SORDAC) AFCEA 2014 Brief", 15. In another instance, Mr. Geurts reportedly stated "Velocity is my combat advantage. Iteration speed is what I'm after. Because if I can go five times faster than you, I can fail four times and still beat you to the target." See Andrew Clevenger, "SOCOM Acquisition Chief Embraces Change, Adaptability," DefenseNews, January 19, 2016, https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2016/01/20/socom-acquisition-chief-embraces-change-adaptability/. |

| 31. |

SOCOM Acquisition Executive James Smith, reportedly stated the followin: ... because of the relatively small size of SOF, most of our programs fall into the lowest Acquisition Category (ACAT). They require less oversight. We tailor our approach to these programs appropriately. The services are doing the same now but they're also responsible for large scale programs that are mandated to have greater oversight. That oversight comes with a cost and schedule impact. |

| 32. |

CRS Report R41293, The Nunn-McCurdy Act: Background, Analysis, and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 33. |

CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 34. |

Alex Haber and Jeff Jeffress, "Supporting the fight for more effectiveness in DoD acquisitions," The Hill, March 12, 2015, http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/homeland-security/235393-supporting-the-fight-for-more-effectiveness-in-dod (accessed on May 4, 2018). |

| 35. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Defense Acquisition: Advanced SEAL Delivery System Program Needs Increased Oversight, GAO-03-442, March 2003, pp. 8-10. Arena, Mark V., John Birkler, Malcolm MacKinnon, and Denis Rushworth, Advanced SEAL Delivery System: Perspectives and Options. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2001. https://www.rand.org/pubs/documented_briefings/DB352.html. |

| 36. |