School Resource Officers: Issues for Congress

The school shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, Great Mills High School in Great Mills, MD, and Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, TX, have generated renewed interest in what Congress might consider to enhance security at the nation’s schools. School resource officer (SRO) programs have been discussed as a possible strategy for increasing school safety. SROs are sworn law enforcement officers who are assigned to work at a school on a long-term basis. While there are no current figures on the number of SROs in the United States, data indicate that 42% of U.S. public schools reported that they had at least one full-time or part-time SRO present at least once a week during the 2015-2016 school year (SY).

There are multiple issues policymakers might consider should Congress take up legislation to promote SRO programs as a solution to school shootings, including the following:

How common are at-school homicides? On average, annually, 23 children ages 5-18 were victims of homicide at school from SY1992-1993 to SY2014-2015. There was a general downward trend in the number of school-related homicides of children between these two time periods. Also, to place the number of school-related homicides in context, during SY2014-2015 there were 1,168 homicides of children ages 5-18, of which 20 occurred at schools.

Can the presence of an SRO at a school prevent a school shooting? Much of the research evaluating the effectiveness of SRO programs has examined their effect on more common crimes and not school shootings, and the findings are mixed. Also potentially illuminating is a recent effort undertaken by the Washington Post that examined school shootings since 1999. It identified 197 incidences of gun violence during and near school hours and uncovered one instance when an SRO killed an active school shooter. Since the Post published its story there have been two other incidents where an SRO intervened during a school shooting. The extent to which the presence of an SRO has prevented a school shooting, however, is unknown.

What effect do SROs have on the school environment? SROs may have varied effects on school environments. While assigning an SRO to a school might serve as a deterrent to a potential school shooter, or provide a quicker law enforcement response in cases where a school shooting occurs, it may also escalate the consequences associated with students’ actions. SROs establish a regular law enforcement presence in schools and there is some concern their presence might result in more children either being suspended or expelled or entering the criminal justice system for relatively minor offenses. There is a limited body of research available regarding the effect SROs have on the school setting. One meta-analysis suggests the presence of SROs is associated with more suspensions and expulsions. Research findings regarding the effect SROs have on student arrests suggest that the presence of SROs might increase the chances that students are arrested for some low-level offenses such as disorderly conduct.

What steps can be taken to maximize the benefits of SRO programs? The Community Oriented Policing Services Office in the Department of Justice has identified several steps that can be taken that might improve outcomes for SRO programs, including developing a comprehensive school safety plan to help assess whether it is necessary to employ an SRO, being aware of potential pitfalls before agreeing to establish an SRO program, and selecting officers who are likely to succeed in a school environment and properly training those officers.

School Resource Officers: Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- SROs Are More than Armed Sentries

- How Prevalent Are SROs in Schools?

- Select Issues for Congress

- How Frequent are At-School Homicides?

- Could SROs Reduce the Number of School Shootings?

- A Brief Overview of the Literature on the Effectiveness of SRO Programs

- How Often Does the Presence of an SRO Stop or Deter a School Shooter?

- What Effect Do School Resource Officers Have on the School Environment?

- What Steps Can Be Taken to Maximize the Benefits of SRO Programs?

Summary

The school shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, Great Mills High School in Great Mills, MD, and Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, TX, have generated renewed interest in what Congress might consider to enhance security at the nation's schools. School resource officer (SRO) programs have been discussed as a possible strategy for increasing school safety. SROs are sworn law enforcement officers who are assigned to work at a school on a long-term basis. While there are no current figures on the number of SROs in the United States, data indicate that 42% of U.S. public schools reported that they had at least one full-time or part-time SRO present at least once a week during the 2015-2016 school year (SY).

There are multiple issues policymakers might consider should Congress take up legislation to promote SRO programs as a solution to school shootings, including the following:

- How common are at-school homicides? On average, annually, 23 children ages 5-18 were victims of homicide at school from SY1992-1993 to SY2014-2015. There was a general downward trend in the number of school-related homicides of children between these two time periods. Also, to place the number of school-related homicides in context, during SY2014-2015 there were 1,168 homicides of children ages 5-18, of which 20 occurred at schools.

- Can the presence of an SRO at a school prevent a school shooting? Much of the research evaluating the effectiveness of SRO programs has examined their effect on more common crimes and not school shootings, and the findings are mixed. Also potentially illuminating is a recent effort undertaken by the Washington Post that examined school shootings since 1999. It identified 197 incidences of gun violence during and near school hours and uncovered one instance when an SRO killed an active school shooter. Since the Post published its story there have been two other incidents where an SRO intervened during a school shooting. The extent to which the presence of an SRO has prevented a school shooting, however, is unknown.

- What effect do SROs have on the school environment? SROs may have varied effects on school environments. While assigning an SRO to a school might serve as a deterrent to a potential school shooter, or provide a quicker law enforcement response in cases where a school shooting occurs, it may also escalate the consequences associated with students' actions. SROs establish a regular law enforcement presence in schools and there is some concern their presence might result in more children either being suspended or expelled or entering the criminal justice system for relatively minor offenses. There is a limited body of research available regarding the effect SROs have on the school setting. One meta-analysis suggests the presence of SROs is associated with more suspensions and expulsions. Research findings regarding the effect SROs have on student arrests suggest that the presence of SROs might increase the chances that students are arrested for some low-level offenses such as disorderly conduct.

- What steps can be taken to maximize the benefits of SRO programs? The Community Oriented Policing Services Office in the Department of Justice has identified several steps that can be taken that might improve outcomes for SRO programs, including developing a comprehensive school safety plan to help assess whether it is necessary to employ an SRO, being aware of potential pitfalls before agreeing to establish an SRO program, and selecting officers who are likely to succeed in a school environment and properly training those officers.

The February 14, 2018, shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL; the March 20, 2018, shooting at Great Mills High School in Great Mills, MD; and the May 18, 2018, shooting at Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, TX, are the latest school shootings to grab the country's attention. While school shootings have occurred at least as far back as 1974,1 it was the 1999 mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, CO, that led many people to identify school shootings as a social problem. As one scholar noted, "[a]t the turn of the millennium, school shootings were an ascendant social problem, often because the events garnered public interest, which contributed to the perception that school shootings were a new form of violence occurring with increased frequency and intensity."2 Concerns about school shootings have led to an expansion of school violence prevention programs. Program actions range from removing graffiti on school grounds to the use of metal detectors and camera systems and the enforcement of zero-tolerance policies that mandate punishment for students who commit certain serious infractions.3 School resource officer (SRO) programs have emerged as one of the most popular strategies for increasing school safety.4

After the recent school shootings in Florida, Maryland, and Texas, policymakers have expressed an interest in what Congress could do to promote the expansion of SRO programs in schools. This report provides an overview of some of the relevant issues policymakers might consider.

SROs Are More than Armed Sentries

While recent interest in expanding SRO programs has focused on SROs' potential to deter or respond to active shooters, these officers are more than armed sentries waiting to engage a shooter. The duties of SROs can vary from one community to another, which makes it difficult to develop a single list of SRO responsibilities, but their roles can be placed into three general categories: (1) safety expert and law enforcer, (2) problem solver and liaison to community resources, and (3) educator.5 SROs may serve as safety experts and law enforcers by assuming primary responsibility for handling calls for service from the school, making arrests, issuing citations on campus, taking actions against unauthorized persons on school property, and responding to off-campus criminal activities that involve students.6 They serve as first responders in the event of critical incidents at the school. SROs can also help solve problems that are not necessarily crimes (e.g., bullying or disorderly behavior) and those that might contribute to criminal incidents (e.g., gang activity).7 Problem-solving activities conducted by SROs can include developing and expanding crime prevention efforts and community or restorative justice initiatives for students. SROs can also present courses on topics related to policing or responsible citizenship for students, faculty, and parents.8

|

Who Exactly is an SRO? A Clarification of the Nomenclature The term "school resource officer" (or "SRO") is sometimes used to refer to anyone who works in a school, wears a law enforcement-like uniform, and is responsible for a school's security. However, the term technically only applies to sworn law enforcement officers who are assigned to work at a school on a long-term basis.9 SROs differ from school safety officers, who are non-sworn civilians, typically with no arrest authority, who are employed by the local school. SROs are employed by a law enforcement agency to ensure the safety and security of students, faculty, staff, and visitors.10 SROs might also be confused with school police officers, who are sworn law enforcement officers who work in schools.11 The difference between SROs and school police officers is that the latter are employed by a school police department (e.g., the Los Angeles School Police Department) and not a city police department or sheriff's office. |

How Prevalent Are SROs in Schools?

The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education on how many U.S. schools have SROs comes from the National Center for Education Statistics' (NCES') spring 2016 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS).12 The 2016 SSOCS was based on a nationally representative stratified random sample of 3,553 public schools and collected data on a variety of topics including the location, enrollment size, and the type of schools (i.e., primary school, middle school, high school, or combined) that have SROs.13 Completed surveys were returned by 2,092 schools, yielding a response rate of 63% once the data was weighted to account for original sampling probabilities.14

NCES reports that 42% of U.S. public schools that participated in the SSOCS survey indicated they had at least one full-time or part-time SRO during the 2015-2016 school year (SY).15 At a minimum, these schools had one SRO present at activities happening in school buildings, on school grounds, on school buses, or at places that hold school-sponsored events or activities at least once a week.16 NCES reports that 22% of schools had a full-time SRO while 21% had a SRO who was as the school part-time.17 Data from the SSOCS for SY2015-2016 show that a greater proportion of high schools and schools with enrollments of 1,000 or more reported the presence of SROs. NCES reports that 68% of high schools had an SRO present at least once a week during SY2015-2016, compared to 59% of middle schools and 30% of elementary schools.18 Similarly, 77% of schools with enrollments of 1,000 or more students had an SRO present at least one day a week, compared to 47% of schools with enrollments of 999-500 students, 36% of schools with enrollments of 499-300 students, and 24% of schools with enrollments of less than 300 students.19

One limitation of the data is that they did not account for schools where SROs were present less than weekly. The SSOCS questionnaire for SY2015-2016 asked "during the 2015–16 school year, did you have any sworn law enforcement officers (including School Resource Officers) present at your school at least once a week? [emphasis original]." Another question, "how many of the following were present in your school at least once a week?", was followed by a list of security personnel, including full-time and part-time SROs, with instructions to "include all career sworn law enforcement officers with arrest authority, who have specialized training and are assigned to work in collaboration with school organizations."20 SROs, other sworn law enforcement officers, and security personnel who are at schools less frequently than weekly are not captured in the SSOCS data.

Select Issues for Congress

There are multiple issues policymakers might consider should Congress take up legislation to promote SRO programs, including the following:

- What is the likelihood that children will be killed at school?

- Can the presence of an SRO at a school prevent a shooting?

- What effect do SROs have on the school environment?

- What steps can be taken to maximize the benefits of SRO programs?

How Frequent are At-School Homicides?

One issue policymakers might consider is whether there is a need for a large-scale expansion of SRO programs. Policymakers might have an interest in increasing the presence of SROs stationed at schools across the country as a way of promoting school safety. If the desire to expand SRO programs is principally related to concerns about potential shootings, it may be worth considering whether there is an epidemic of schools shootings. Some suggest that the widespread media coverage of school shootings creates a "moral panic" that gives people a sense that the threat of children being victims of a school shooting is greater than it really is.21 Others say that the clarion call for a response to school shootings that protects children is well founded. In the sections that follow, available data are reviewed and discussed to better understand whether there is a need for additional resources to prevent school-based homicides.

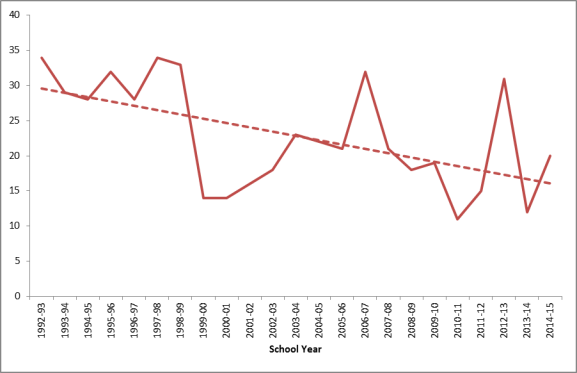

Figure 1 presents data on the number of at-school homicides of children ages 5-18 each school year from SY1992-1993 to SY2014-2015. On average, there have been 23 at-school homicides each school year from SY1992-SY1993 to SY2014-2015. While there were instances where there was a noticeable change in the number of at-school homicides from one school year to the next, the trend line (the dashed line in the figure) indicates that there has been a general downward trend in the number of at-school homicides during this period. Multiple-victim shooting incidents at schools in the United States can cause a spike in the number of at-school homicides. For example, the 20 students killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut accounted for nearly two-thirds of the at-school homicides during SY2012-2013. Without those deaths, the number of at-school homicides would have been in-line with the number of at-school homicides in SY2011-2012 and SY2013-2014. However, not all spikes in at-school homicides are attributable to multiple-victim schools shootings. There were 32 at-school homicides during SY2006-2007, and the deadliest school shooting during that year involved the deaths of five students at the Nickel Mines school in Pennsylvania. While any homicides that occur at schools would likely undermine a community's sense of their children's safety, data from this period indicate that most children who are victims of homicide are killed when they are not at school. NCES reported that during SY2014-2015 there were 1,168 homicides of children ages 5-18, of which 20 occurred at schools.22

Fighting, bullying, and other problem behaviors at schools are generally not driving the current debate about the potential expansion of SRO programs; it is multiple-victim shootings at schools that are driving the discussion. While data on the number of homicides at schools provides insight into the prevalence of violent deaths that occur at schools each school year, they do not indicate how many students are the victims of multiple-victim shooting incidents. Researchers at Northeastern University report that since 1996 there have been 16 multiple-victim shootings in schools (defined as shootings involving four or more victims and at least two deaths by firearms, excluding the assailant), and of those, eight were mass shootings (defined as incidents involving four or more deaths by firearm, excluding the assailant).23 The researchers characterized mass school shootings as rare and "not an epidemic."24 Their data also indicate that the number of fatal school shootings (defined as incidents where at least one individual is killed by firearms at school), of which mass school shootings is a subset, have decreased since the early 1990s. In SY2014-2015, approximately one per 6.7 million students was killed in fatal school shootings, and for most of the past 15 years the number of children killed in fatal school shootings was below this rate.25 Throughout most of the 1990s, the number of children killed in fatal school shootings was more than one per 5 million students, with a peak of approximately one per 1.8 million students in SY1992-1993 (the first year for which data were collected).

Could SROs Reduce the Number of School Shootings?

Interest in potentially expanding SRO programs has generally stemmed at least in part from the belief that the presence of an SRO could deter school shootings or, if a school shooting were to occur, that the SRO would be able to respond quickly and confront the attacker. Thus far, no publicly available research has evaluated whether SROs serve as an effective deterrent to school shootings or whether SROs reduce the loss of life when school shootings occur. In part, this may be due to methodological challenges when trying to measure things, in this case school shootings and deaths due to school shootings, that did not happen. There is some research on the effectiveness of SRO programs vis-à-vis school crime, but the findings are mixed.

A Brief Overview of the Literature on the Effectiveness of SRO Programs

Several groups of researchers used data from the 2005-2006 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) to evaluate the effect of SROs and security guards on school crime.26 Jennings et al. found that the number of SROs in a school had a statistically significant negative effect on the number of reported serious violent crimes, but not on the number of reported violent crimes.27 Maskaly et al. found that violent crime was generally higher in larger-sized schools and middle schools regardless of whether SROs or security guards were present. However, in a separate study researchers found that violent crime was higher in schools with only security personnel relative to schools with SROs, which suggests that SROs might be able to mitigate violent crime to some degree.28 Crawford and Burns found that the effect of SROs on serious violence and weapons-related offenses depended on whether SROs were stationed in high schools or schools with other grade levels.29 The presence of SROs did not have a statistically significant effect on reported serious violence in high schools, but there was a positive statistically significant effect of SROs on reported serious violence in schools of other grade levels. The presence of SROs also resulted in fewer reported attacks with a weapon and gun possession in lower grades, but not in high schools. SROs also had a positive statistically significant association with reported threatened attacks with a weapon and gun possession in high schools.

The conclusions of all the studies that utilized the 2005-2006 SSOCS data for their analyses are limited by the fact that the data are cross-sectional (i.e., they look at all schools in the survey at one point in time). Since the researchers did not collect data on reported crimes at schools included in the 2005-2006 SSOCS before or after the survey was conducted, they were unable to determine if crime was increasing prior to SROs being stationed at the schools or what happened to crime after SROs started working at the schools. As Maskaly et al. note,

any relationships identified here are correlational, and this precludes us from making any definitive statements about the causal order of security personnel and school crime. For instance, we are unable to determine if schools that were experiencing high crime decided to employ either SROs or private security guards to combat the school crime problem and/or whether the presence of and use-of-force capabilities of the SROs or private security guards specifically caused a reduction in school crime.30

Na and Gottfredson merged SSOCS data from three iterations of the survey (2003-2004, 2005-2006, and 2007-2008) which allowed them to attempt to evaluate whether the reported number of offenses decreased after schools started SRO programs (some schools, by chance, were included in more than one survey).31 The results of the analysis show that schools that added SROs did not have a statistically significant change in the rate of serious violent,32 non-serious violent,33 or property crimes.34 However, schools that added SROs reported a statistically significant increase in the rate of weapon and drug offenses.35 There are some limitations to this study, including the sample of schools included in the study is not representative of all schools in the United States (it over-represents secondary schools, large schools, and non-rural schools) and the effects of adding SROs may be confounded by the installation of other security devices (e.g., metal detectors) or other security-related policies.

The body of research on the ability of SRO programs to reduce school crime is limited. There are only a handful of studies on the effects of SROs on school crime and there are important limitations to the reported crime data utilized in the studies that have been published. For example, the SSOCS asks principals to provide data on the number of crimes at their schools, and it is possible that principals are not aware of all crimes in their schools and they might under-report crime out of fear of the effects of bad publicity.36 Additionally, there are limitations in the methods employed to isolate the effects of SROs on the outcomes of interest. The research that is available draws conflicting conclusions about whether SRO programs are effective at reducing school violence.

While research on the effectiveness of SRO programs largely focuses on their effect on school crime, studies have also evaluated what effect they have on student and staff perceptions of school safety. Some research suggests that the presence of SROs reduces fear of crime among students and increases feelings of safety,37 while other research suggests that the presence of SROs indicates to students that schools are unsafe places.38 Research by Travis and Coons shows how there can be conflicting opinions about the presence of SROs. In interviews with focus groups at 14 schools, many participants stated that one of the downsides to having an SRO at the school is that it gives the impression that there was something wrong with the school.39 On the other hand, participants from schools with at least one dedicated SRO also indicated that the presence of an SRO was accepted and generally desirable. The researchers noted that at no school did participants unanimously agree that they did not want an SRO at the school.40 Students' acceptance of an SRO presence appeared to be related to how the officer interacted with students. Students who felt the SRO was friendly and helpful had a more positive reaction to the officer's presence while students who felt their SRO was intrusive or used accusatory approaches had a more negative opinion.41 However, a study by Bachman, Randolph, and Brown suggests that students' perception of schools safety can be influenced by other factors, such as whether students have been victims of crime and whether gangs are present at the school.42 Their study also suggests that the presence of security guards43 increases fear of victimization at school in white students but not black students.

Research has also found that teachers and principals tend to have positive attitudes toward SROs and believe that their presence deters student misconduct and reduces school crime.44 For example, in focus groups conducted by Travis and Coon, high school teachers, more so than elementary and middle school teachers, thought the presence of an SRO was desirable.45 Also, teachers that worked in schools that served more impoverished communities wanted a greater police presence to assist with behavioral problems.

The research on how SROs effect the perception of crime in schools is also limited. Of the handful of studies on this topic, many collected data by surveying students from a small number of schools in one geographic area (e.g., schools in one city or in a certain portion of a state) or they relied on focus groups. This might raise questions about how generalizable the results of these studies are to students and schools in other areas. Also, these studies rely upon students and school employees' perception of school safety. Perception of school safety can be subjective. What is perceived to be a dangerous school by one student might be considered a relatively safe place by another student. As was revealed in research summarized above, this may be due to students' experience with victimization or a gang presence in the school. However, this is not to say that students' perceptions of school safety are unimportant. As one scholar notes, "[t]he reduction of student perception of danger at school should be viewed as an essential function of [SROs] because perception of danger at school has consistently been shown to negatively impact students' attendance, confidence, and academic performance."46

How Often Does the Presence of an SRO Stop or Deter a School Shooter?

As noted above, there is not a robust body of research addressing these issues. However, the role of SROs as first responders to school shootings has received increased attention since the Parkland, FL, school shooting. A recent Washington Post examination offers some insights on issues related to SROs and school shootings. Washington Post reporters identified more than 1,000 incidents of gunfire at primary or secondary schools using Nexis, news articles, open-source databases, law enforcement reports, information from school websites, and calls to schools and police departments between April 1999 and March 2018.47 They included only shootings that happened on school premises immediately before, during or just after classes in their examination, which reduced the number of incidents to 197. In those 197 incidents, the Washington Post found one instance in which an SRO stopped an active school shooter by returning fire.48

After the Washington Post published its article on school shootings, there were two incidents where SROs intervened after someone had opened fire at a school. In Dixon, IL, an SRO shot and wounded a shooter after the shooter fired at the officer while he was trying to flee.49 Also, an SRO interceded during the shooting at Great Mills High School in Maryland, but the shooter was later determined to have died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.50

Of the nearly 200 recorded incidents of gunfire in primary and secondary schools and on school grounds during school hours between 1999 and 2018,51 at least 68 of the schools employed an SRO or a security guard, including 4 of the 5 schools where, according to the Washington Post, the "worst rampages" took place.52 Whether the presence of an SRO at a school makes a shooter more or less likely to attack the school may depend in part on the shooter's desired outcome. Multiple examples of students who wanted to commit suicide by provoking armed security personnel to shoot them were found in the Washington Post's analysis.53 However, in at least one instance a school shooter deliberately selected an elementary school with no security personnel instead of the middle school he attended because his middle school had an armed security officer.54

As mentioned previously, many schools reported that they either did not have an SRO, or that the SRO works part-time. Having an SRO who works part-time could limit whatever deterrent effect an SRO's presence might have on a potential active shooter. For example, if the shooter is familiar with the SRO's schedule, the shooter might attempt to commit his crime when the SRO is not at the school. Also, it is possible that an SRO could not respond to an active shooter situation quicker than regular law enforcement if he or she is not at the school. However, a part-time SRO might provide some deterrent effect if it is known that an SRO is stationed at the school but a potential shooter is not familiar with the SRO's schedule.

What Effect Do School Resource Officers Have on the School Environment?

While recent interest in SROs programs has stemmed from proposals to use SROs as a strategy to prevent school shootings, it should be noted that SROs are more than armed sentries whose sole purpose is to stand guard and wait for an attack. SROs are sworn law enforcement officers who, among other things, patrol the school, investigate criminal complaints, and handle violators of the law. Therefore, while assigning an SRO to a school might improve relationships between law enforcement and youth, serve as a deterrent to a potential school shooter, or provide a quicker law enforcement response in cases where a school shooting occurs, it will also establish a regular law enforcement presence in the school. There might be some concern that onsite benefits and any potential deterrent effect generated by placing SROs in schools could be offset by the social costs that might arise by potentially having more children suspended or expelled from school or entering the juvenile justice system for relatively minor offenses. Similarly, concerns may arise about the monetary cost of adding SROs if a wide-scale expansion is envisioned.55 The use of SROs has occurred in the context of increasing concern about school security and the concomitant adoption of more security measures in schools and the adjustment of school discipline policies.

Fisher and Hennessy provide a systematic review and meta-analysis of research on the association between the presence of SROs in high schools and the use of exclusionary discipline (i.e., suspensions and expulsions).56 The question driving the research was whether the presence of SROs leads to greater use of suspensions and expulsions. Their analysis utilized two models, one that tested the effects of SROs on exclusionary discipline using studies with a pre-post design (i.e., evaluating discipline before and after SROs were assigned to the school) and one that used a comparison school design (i.e., evaluating differences in discipline at schools with and without SROs). The model using pre-post studies revealed that SROs are associated with a statistically significant increase in exclusionary discipline. The model using comparison school studies did not achieve statistical significance, but the authors note that the results were consistent with the pre-post model. They conclude that the presence of SROs in high schools is associated with higher levels of exclusionary discipline. The authors caution that much of the research on the effect that SROs have on school discipline is not methodologically rigorous (e.g., studies did not randomly assign SROs to schools, not enough data were collected to test changes in crime and disciplinary trends before and after an SRO was assigned to a school, studies that compared schools with and without SROs were poorly matched based on variables that could affect crime and school discipline), and the strength of their conclusions is only as viable as the underlying research. Also, reflecting the lack of robust research on SROs and their relationship with the use of exclusionary discipline, both models had small sample sizes.57

Theriot used data from a school district in the southeastern United States to test the criminalization of student misconduct theory.58 Theriot's analysis indicated that middle and high schools with SROs had higher arrest rates than schools without them, but the relationship between SROs and arrest rates disappeared when the analysis controlled for school-level poverty. More-nuanced results of the study indicated that students in schools with SROs were more likely than students in schools without them to be arrested for disorderly conduct, even when controlling for school-level poverty, which lends credence to the idea that student misbehavior is being criminalized. The research also revealed that schools with SROs had lower arrest rates for assault and possessing a weapon on school grounds. The researcher opined that this suggests SROs might serve as a deterrent for more serious crimes. For example, students might be less likely to bring a weapon to school if an SRO is present because they fear they might be caught. Students might also be less likely to fight if they believe they will be arrested for assault. A critique of Theriot's study notes that the analysis did not include data for a long enough period of time before SROs were assigned to some schools, and the control group (i.e., the non-SRO schools) still had some contact with law enforcement.59

Na and Gottfredson, discussed previously, also included an analysis of whether schools that added SROs had a greater percentage of crimes reported to law enforcement and whether a greater proportion of students were subject to "harsh discipline" (i.e., the student was removed, transferred, or suspended for five or more days).60 The researchers found that schools that added SROs were more likely to report non-serious violent crimes (i.e., physical attack or fights without a weapon and threat of physical attack without a weapon) to the police than schools that did not add SROs.61 The reporting of other types of crime and the reporting of crime overall were not affected by the addition of SROs. Na and Gottfredson conclude that their findings are "consistent with our prediction that increased use of SROs facilitates the formal processing of minor offenses."62 However, their analysis also found that students at schools that added SROs were not any more likely than students at schools that did not add SROs to be subject to harsh discipline for committing any offense that was reported to the police. Together, these studies suggest that the concern about the presence of SROs leading to increased use of the juvenile justice system for school-based minor offenses may be warranted, but many unanswered questions remain about the full range of potential positive and negative consequences of SROs.

What Steps Can Be Taken to Maximize the Benefits of SRO Programs?

Policymakers could have an interest in encouraging the expansion of SRO programs as a means to promote school safety, but at the same time be concerned about what effect SROs could have on the school environment. While evaluation research on the efficacy of particular program models or characteristics is limited, the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Office, an office within the Department of Justice, has identified several elements of a successful SRO program.63

First, the COPS guide suggests that all schools should develop a comprehensive school safety plan based on their school safety goals and a thorough analysis of the problem(s) the school is facing before determining if it is necessary to employ an SRO.64 In some instances, school safety plans might not require the deployment of an SRO. However, if after composing a school safety plan the school decides to use an SRO, there should be clear goals for the program. SROs should engage in problem-solving policing activities that directly relate to school safety goals and address identified needs, and data should be collected to determine whether the program is achieving its goals.

Second, the COPS guide suggests that schools and the law enforcement agencies that SROs work for should be aware of any pitfalls before agreeing to establish an SRO program.65 There may be philosophical differences between school administrators and law enforcement agencies about the role of the SRO. Law enforcement agencies focus on public safety while schools focus on educating students. Establishing an agreed-upon operating protocol or MOU is considered a critical element of an effective school-police partnership.66 The MOU should clearly state the roles and responsibilities of the actors involved in the program.

Third, the COPS guide suggests that selecting officers who are likely to succeed in a school environment—such as officers who can effectively work with students, parents, and school administrators; have an understanding of child development and psychology; and have public speaking and teaching skills—and properly training those officers are important components of a successful SRO program.67 While it is possible to recruit officers with some of the skills necessary to be effective SROs, it is nonetheless considered important to provide training so officers can hone skills they already have or develop new skills that can make them more effective. The Police Foundation, for instance, recommends that training for SROs focus on the following:

- child and adolescent development, with an emphasis on the effect of trauma on student behavior, health, and learning;

- subconscious (or implicit) bias that can disproportionately affect youth of color and youth with disabilities or mental health issues;

- crisis intervention for youth;

- alternatives to detention and incarceration, such as peer courts, restorative justice, etc.; and

- legal issues like special protections for students with disabilities.68

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Bryan Vossekuil, Robert A. Fein, and Marisa Reddy et al., The Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative: Implications for the Prevention of School Attacks in the United States, United States Secret Service and the Department of Education, Washington, DC, June 2004. |

| 2. |

Glenn W. Muschert, "Research in School Shootings," Sociology Compass, vol. 1, no. 1 (2007), p. 61. |

| 3. |

Matthew T. Theriot and Matthew J. Cuellar, "School Resource Officers and Students' Rights," Contemporary Justice Review, vol. 19, no. 3 (2016), p. 1. |

| 4. |

Ibid. |

| 5. |

Barbara Raymond, Assigning Police Officers to Schools, U.S. Department of Justice, Community Oriented Policing Services Office, Problem-oriented Guides for Police Response Guides Series No. 10, Washington, DC, April 2010, p. 2 (hereinafter, "Assigning Police Officers to Schools"). |

| 6. |

Ibid. |

| 7. |

Ibid., p. 4. |

| 8. |

Ibid., p. 5. |

| 9. |

The Police Foundation, Defining the Role of School-Based Police Officers, p. 2, http://www.policefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/PF_IssueBriefs_Defining-the-Role-of-School-Based-Police-Officers_FINAL.pdf (hereinafter, "Defining the Role of School-Based Police Officers"). |

| 10. |

Ibid. |

| 11. |

Ibid. |

| 12. |

M. Diliberti, M. Jackson, and J. Kemp, Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public Schools: Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2015–16 (NCES 2017-122), U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC, 2017 (hereinafter, "Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2015–16"). |

| 13. |

"School Resource Officers" were defined in the SSOCS as "career sworn law enforcement officers with arrest authority, who have specialized training and are assigned to work in collaboration with school organizations." |

| 14. |

Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2015–16, Table 9, p. 14. |

| 15. |

Ibid. |

| 16. |

According to the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), "Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey," 1982-1983 through 2015-2016, there were 98,277 public schools in the United States during SY2015-2016. If 42% of all U.S. public schools had an SRO on the premises at least once a week during SY2015-2016, approximately 41,300 schools would have had, at a minimum, a weekly SRO presence. |

| 17. |

Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2015–16, Table 9, p. 14. |

| 18. |

Ibid. |

| 19. |

Ibid. |

| 20. |

Principals were asked additional questions about the duties carried out by SROs/sworn law enforcement. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, School Survey on Crime and Safety, Principal Questionnaire, 2015-16 School Year, p. 10. |

| 21. |

Glenn W. Muschert, "Research in School Shootings," Sociology Compass, vol. 1, no. 1 (2007), pp. 65-67. |

| 22. |

Lauren Musu-Gillette, Anlan Zhang, and Ke Wang, et al., Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2017, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2018-036, Washington, DC, March 2018, p. 33. |

| 23. |

Allie Nicodemo and Lia Petronio, "Schools Are Safer Than They Were in the 90s, and School Shootings Are Not More Common Than They Used to Be, Researchers Say," in a blog by Northeastern University, February 26, 2018, http://news.northeastern.edu/2018/02/26/schools-are-still-one-of-the-safest-places-for-children-researcher-says/ (hereinafter, "Schools are Safer Than They Were in the 90s"). |

| 24. |

Other experts have characterized the number of mass school shootings as an epidemic. For example, Katsiyannis, Whitford, and Ennis note that "[c]learly, mass school shootings present an epidemic that must be addressed." Antonis Katsiyannis, Denise K. Whitford, and Robin Parks Ennis, "Historical Examination of United States Intentional Mass School Shootings in the 20th and 21st Centuries: Implications for Students, Schools, and Society," Journal of Family Studies, published online April 19, 2018. |

| 25. |

Schools are Safer Than They Were in the 90s. |

| 26. |

The SSOCS is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of approximately 3,500 public elementary and secondary schools that collects school-level data on crime and safety. |

| 27. |

For this study, "serious violent crime" included reported incidents of rape, sexual battery, robbery (strong armed and armed), aggravated assault, and threats of aggravated assault. "Violent crime" included all of the offenses defined as "serious violent crimes" plus the number of physical assaults, fights between students, and threats of assault without a weapon. Wesley G. Jennings, David N. Khey, and Jon Maskaly et al., "Evaluating the Relationship Between Law Enforcement and School Security Measures and Violent Crime in Schools," Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, vol. 11, no. 2 (2011), pp. 109-124. |

| 28. |

Violent crime" included reported incidents of rape, sexual battery, robbery (strong armed and armed), assault (aggravated and unarmed), threats of assault (aggravated and simple), and fights between students. Jon Maskaly, Christopher M. Donner, Jennifer Lanterman et al., "On the Association Between SROs, Private Security Guards, Use-of-Force Capabilities, and Violent Crime in Schools," Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, vol. 11, no. 2 (2011), pp. 159-176 (hereinafter, "On the Association Between SROs, Private Security Guards, Use-of-Force Capabilities, and Violent Crime in Schools"). |

| 29. |

"Serious violence" included incidents of rape, sexual battery, robbery, or aggravated assault. "Weapons-related violence" included threatened attacks with a weapon, attacks with a weapon, and gun possession. Charles Crawford and Ronald Burns, "Preventing School Violence: Assessing Armed Guardians, School Policy, and Context," Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, vol. 38, no. 4 (2015), pp. 631-647. |

| 30. |

"On the Association Between SROs, Private Security Guards, Use-of-Force Capabilities, and Violent Crime in Schools," p. 172. |

| 31. |

Chongmin Na and Denise C. Gottfredson, "Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offender Behaviors," Justice Quarterly, online publication, 2011 (hereinafter, "Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offender Behaviors"). |

| 32. |

"Serious violent" crimes included rape, sexual battery other than rape, robbery with or without a weapon, physical attack or fight with a weapon, and threat of physical attack with a weapon. |

| 33. |

"Non-serious violent" crimes included physical attack or fight without a weapon and threat of physical attack without a weapon. |

| 34. |

"Property" crimes included theft and vandalism. |

| 35. |

"Weapons and drug" offenses included possession of a firearm or explosive device; possession of a knife or sharp object; and distribution, possession, or use of illegal drugs or alcohol. |

| 36. |

Lawrence F. Travis III and Julie K. Coon, The Role of Law Enforcement in Public School Safety: A National Survey, July 10, 2005, p. 54 (hereinafter, "The Role of Law Enforcement in Public School Safety"). |

| 37. |

Margaret M Chrusciel, Scott Wolfe, and J. Andrew Hansen, et al., "Law Enforcement Executive and Principal Perspectives on School Safety Measures," Policing: An International Journal of Policing Strategies and Management, vol. 38, no. 1 (2015), p. 26 (hereinafter "Law Enforcement Executive and Principal Perspectives on School Safety Measures"). |

| 38. |

Cheryl Lero Jonson, "Preventing School Shootings: The Effectiveness of Safety Measures," Victims and Offenders, vol. 12, no. 6 (2017), p. 962. |

| 39. |

The Role of Law Enforcement in Public School Safety, p. 196. |

| 40. |

Ibid. |

| 41. |

Ibid., p. 198. |

| 42. |

Ronet Bachman, Antonia Randolph, and Bethany L. Brown, "Predicting Perceptions of Fear At School and Going to and From School for African American and White Students: The Effects of School Security Measures," Youth and Society, vol. 43, no. 2 (2011), pp. 705-726. |

| 43. |

The study by Bachman, Randolph, and Brown used data from 2005 School Crime Supplement of the National Crime Victimization Survey. Students who were a part of the survey were asked whether they had security guards and/or assigned police officers at their schools. The question does not make a distinction between school security guards and SROs. |

| 44. |

Law Enforcement Executive and Principal Perspectives on School Safety Measures, p. 26. |

| 45. |

The Role of Law Enforcement in Public School Safety, p. 198. |

| 46. |

Ben Brown, "Understanding and Assessing School Police Officers: A Conceptual and Methodological Comment," Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 34 (2006), p. 598. |

| 47. |

John Woodrow Cox and Steven Rich, "Scarred by school shootings: More than 187,000 students have been exposed to gun violence at school since Columbine," Washington Post, March 21, 2018 (hereinafter, "Scarred by school shootings"). |

| 48. |

This incident occurred at Granite Hills High School in El Cajon, CA. A student at the high school opened fire on the school building from the street using a shotgun. An El Cajon police officer who was recently assigned to the school responded to the sound of shots being fired. The officer fired at the shooter, wounding him. For more information on this incident, see Erin Texeira, Greg Kirkorian, and Scott Martelle, "5 Hurt in Gunfire at High School Near San Diego; Student is Held," Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2001. |

| 49. |

Matthew Walberg, "Things Could Have Gone Much Worse': Charges Filed Against Ex-Student Accused of Exchanging Gunfire With Cop at Dixon High School," Chicago Tribune, May 17, 2018. |

| 50. |

SRO Blaine Gaskill responded to the school shooting at Great Mills High School in St. Mary's County, MD, on March 20, 2018. Gaskill shot the student gunman's weapon at nearly the same moment that the gunman shot himself in the head. It is not clear if Gaskill's intervention stopped the shooter from firing at other students before turning his gun on himself. Lynh Bui, "Student gunman died of self-inflicted gunshot to head in Md. school shooting," The Washington Post, March 26, 2018. |

| 51. |

"Scarred by school shootings." The Washington Post identified 197 incidents of gun violence at 193 schools between April 1999 and March 2018 (i.e., there were 4 schools that experienced 2 shootings). |

| 52. |

"Scarred by school shootings." This analysis determined that of the five "worst rampages" between 1999 and 2018–Columbine, CO (1999); Santana High, CA (2001); Sandy Hook Elementary, CT (2012); Marshall County High, KY (2018); and Marjory Stoneman Douglas, FL (2018)–only Sandy Hook Elementary School did not employ an SRO or security guard. |

| 53. |

"Scarred by school shootings." |

| 54. |

Ibid. |

| 55. |

This report does not provide an estimate of how much it might cost to place an SRO in every school in the United States. However, some scholars have attempted to provide such an estimate. See, for example, Edward W. Hill, The Cost of Arming Schools: The Price of Stopping a Bad Guy with a Gun, Cleveland State University, Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, March 28, 2013, http://cua6.urban.csuohio.edu/publications/hill/ArmingSchools_Hill_032813.pdf. |

| 56. |

Benjamin W. Fisher and Emily Hennessy, "School Resource Officers and Exclusionary Discipline in U.S. High Schools: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis," Adolescent Research Review, vol. 1 (September 2016), pp. 217-233. |

| 57. |

The pre-post model used seven samples from four studies while the comparison school model used three samples from three studies. |

| 58. |

The analysis compared arrests at middle and high schools with SROs (SRO schools) to middle and high schools without SROs (non-SRO schools). The researcher took advantage of a natural experiment in the school district whereby the metropolitan city's police department placed an SRO in each middle and high school in the city while middle and high schools in the district that were outside the city limits did not have an SRO assigned to them. SROs were assigned based only on geography, not on a school's need, history of violence, or demographics. Schools outside of the city were patrolled by sheriff's deputies, who focused solely on law enforcement activities, were assigned to patrol more than one school, and received less school-based training than their SRO counterparts in the city. Matthew T. Theriot, "School Resource Officers and the Criminalization of Student Behavior," Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 37, no. 3 (May-June 2009), pp. 280-287. |

| 59. |

"Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offender Behaviors," p. 7. |

| 60. |

Ibid. |

| 61. |

It is possible that schools with SROs might have a higher number of reported crimes because either students or staff are more likely to report crimes to law enforcement since an SRO is present at the school or crimes committed at the school might be likely to be detected by law enforcement since an SRO is stationed at the school. |

| 62. |

"Police Officers in Schools: Effects on School Crime and the Processing of Offender Behaviors," p. 22. |

| 63. |

Assigning Police Officers to Schools. |

| 64. |

Ibid., p. 15. |

| 65. |

Ibid., p. 22. |

| 66. |

Ibid., p. 30. |

| 67. |

Ibid., p. 23. |

| 68. |

Defining the Role of School-Based Police Officers, p. 6. |