U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations During President Trump’s First Year in Office: Comparative Analysis with Recent Presidents

This report, in light of continued Senate interest in the judicial confirmation process during a President’s first year in office, provides statistics related to the nomination and confirmation of U.S. circuit and district court nominees during the first year of the Trump presidency (as well as during the first year of each of his three immediate predecessors—Presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton).

Some of the report’s findings regarding circuit court nominations include the following:

The number of U.S. circuit court vacancies decreased by 1, from 17 to 16, during the first year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of circuit court judgeships that were vacant decreased from 9.5% to 8.9%.

During his first year in office, President Trump nominated 19 individuals to U.S. circuit court judgeships, of whom 12 (or 63%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.

Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 15 (79%) were men and 4 (21%) were women.

Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 17 (89%) were white and 2 (11%) were Asian American.

The average age of President Trump’s first-year circuit court nominees was 49.

Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 16 (84%) received a rating of well qualified from the American Bar Association, 2 (11%) received a rating of qualified, and 1 (5%) received a rating of not qualified.

The average length of time from nomination to confirmation for President Trump’s first-year circuit and district court nominees (combined) was 115 days, or approximately 3.8 months.

Each of the circuit court nominees confirmed during President Trump’s first year in office was confirmed by roll call vote (and none by unanimous consent or voice vote).

Of the 12 circuit court nominees confirmed during President Trump’s first year in office, 11 received more than 20 nay votes at the time of confirmation (and of the 11, 9 received more than 40 nay votes).

Some of the report’s findings regarding district court nominations include the following:

The number of U.S. district court vacancies increased by 38, from 86 to 124, during the first year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of district court judgeships that were vacant increased from 12.8% to 18.4%.

During his first year in office, President Trump nominated 49 individuals to U.S. district court judgeships, of whom 6 (12%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.

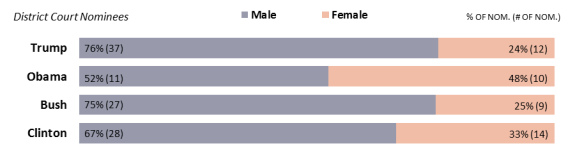

Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 37 (76%) were men and 12 (24%) were women.

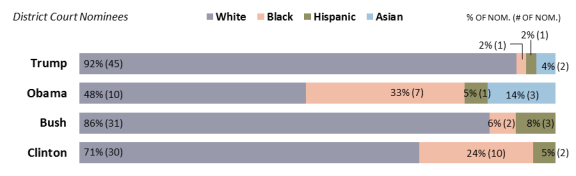

Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 45 (92%) were white, 2 (4%) were Asian American, 1 (2%) was African American, and 1 (2%) was Hispanic.

The average age of President Trump’s first-year district court nominees was 51.

Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump’s first year in office, 26 (53%) received a rating of well qualified, 20 (41%) received a rating of qualified, and 3 (6%) received a rating of not qualified from the American Bar Association.

Each of the district court nominees confirmed during President Trump’s first year in office was confirmed by roll call vote (and none by unanimous consent or voice vote).

Of the six district court nominees confirmed during President Trump’s first year in office, two received more than five nay votes.

U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations During President Trump's First Year in Office: Comparative Analysis with Recent Presidents

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Article III Lower Courts

- U.S. Courts of Appeals

- U.S. District Courts

- U.S. Circuit and District Court Vacancies

- Percent Change in Number of Vacancies from Beginning of First Year to Beginning of Second Year of a Presidency

- Long-Lasting Vacancies that Continued to Exist After a President's First Year

- Number and Percentage of Nominees Confirmed

- U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

- U.S. District Court Nominees

- Select Demographic Characteristics of Nominees

- U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

- Gender

- Race

- Age at Time of Nomination

- U.S. District Court Nominees

- Gender

- Race

- Age at Time of Nomination

- Ratings of Nominees by the American Bar Association

- U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

- U.S. District Court Nominees

- Time from Nomination to Confirmation

- Floor Consideration of Nominations

- Use of Cloture to Reach Confirmation

- Use of Roll Call Votes to Confirm Nominees

- Number of 'Nay' Votes Received at Time of Confirmation

Figures

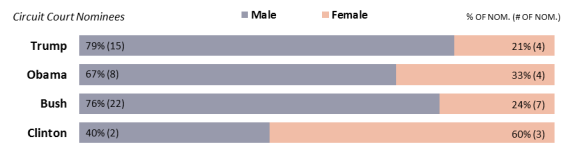

- Figure 1. Number and Percentage of U.S. Circuit Court Nominees by Gender

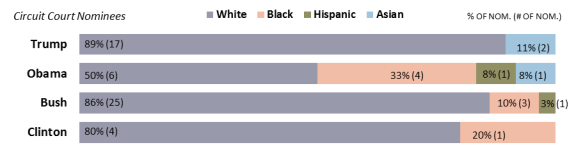

- Figure 2. Number and Percentage of U.S. Circuit Court Nominees by Race

- Figure 3. Number and Percentage of U.S. District Court Nominees by Gender

- Figure 4. Number and Percentage of U.S. District Court Nominees by Race

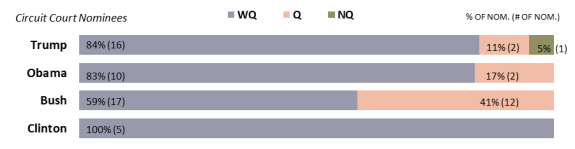

- Figure 5. Ratings of U.S. Circuit Court Nominees by the American Bar Association

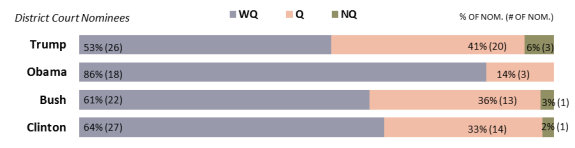

- Figure 6. Ratings of U.S. District Court Nominees by the American Bar Association

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Circuit and District Court Vacancies at the Beginning of the First and Second Years of Select Presidencies

- Table 2. U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees: Number Nominated, Number Confirmed, and Percentage Confirmed

- Table 3. Average and Median Number of Days from Nomination to Confirmation for Nominees Confirmed During First Year of Presidency

- Table 4. Number of U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees Waiting Specified Period of Time from Nomination to Confirmation

- Table 5. Frequency of Confirmation by Voice Vote/Unanimous Consent or Roll Call Vote

- Table 6. Number of 'Nay' Votes Received at Time of Confirmation

Summary

This report, in light of continued Senate interest in the judicial confirmation process during a President's first year in office, provides statistics related to the nomination and confirmation of U.S. circuit and district court nominees during the first year of the Trump presidency (as well as during the first year of each of his three immediate predecessors—Presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton).

Some of the report's findings regarding circuit court nominations include the following:

- The number of U.S. circuit court vacancies decreased by 1, from 17 to 16, during the first year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of circuit court judgeships that were vacant decreased from 9.5% to 8.9%.

- During his first year in office, President Trump nominated 19 individuals to U.S. circuit court judgeships, of whom 12 (or 63%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.

- Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 15 (79%) were men and 4 (21%) were women.

- Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 17 (89%) were white and 2 (11%) were Asian American.

- The average age of President Trump's first-year circuit court nominees was 49.

- Of individuals nominated to circuit court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 16 (84%) received a rating of well qualified from the American Bar Association, 2 (11%) received a rating of qualified, and 1 (5%) received a rating of not qualified.

- The average length of time from nomination to confirmation for President Trump's first-year circuit and district court nominees (combined) was 115 days, or approximately 3.8 months.

- Each of the circuit court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office was confirmed by roll call vote (and none by unanimous consent or voice vote).

- Of the 12 circuit court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office, 11 received more than 20 nay votes at the time of confirmation (and of the 11, 9 received more than 40 nay votes).

Some of the report's findings regarding district court nominations include the following:

- The number of U.S. district court vacancies increased by 38, from 86 to 124, during the first year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of district court judgeships that were vacant increased from 12.8% to 18.4%.

- During his first year in office, President Trump nominated 49 individuals to U.S. district court judgeships, of whom 6 (12%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.

- Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 37 (76%) were men and 12 (24%) were women.

- Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 45 (92%) were white, 2 (4%) were Asian American, 1 (2%) was African American, and 1 (2%) was Hispanic.

- The average age of President Trump's first-year district court nominees was 51.

- Of individuals nominated to district court judgeships during President Trump's first year in office, 26 (53%) received a rating of well qualified, 20 (41%) received a rating of qualified, and 3 (6%) received a rating of not qualified from the American Bar Association.

- Each of the district court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office was confirmed by roll call vote (and none by unanimous consent or voice vote).

- Of the six district court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office, two received more than five nay votes.

Introduction

The process by which lower federal court judges are nominated by the President and considered by the Senate has, in recent decades, been of continuing interest to Senators. During recent Senate debates over judicial nominations, differing perspectives have been expressed about the relative degree of success of a President's nominees in gaining Senate confirmation, compared with nominees of other recent Presidents.1 Senate debate has also concerned whether a President's judicial nominees, relative to the nominees of other recent Presidents, encountered more difficulty or had to wait longer, before receiving consideration by the Senate Judiciary Committee or up-or-down floor votes on confirmation.2 Of related concern to the Senate have been the potential effects of delaying, or at other times rushing, the process by which judicial vacancies are filled.3

This report provides information and analysis on several aspects of the judicial nomination and confirmation process during President Donald Trump's first year in office (as well as during the first year of each of his three immediate predecessors—Presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton).

Most of the statistics presented and discussed in this report were generated from an internal CRS judicial nominations database. Other data sources, however, are noted where appropriate. The statistics account only for nominations made to U.S. circuit court and U.S. district court judgeships.

Article III Lower Courts

Article III, Section I of the Constitution provides, in part, that the "judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." It further provides that Justices on the Supreme Court and judges on lower courts established by Congress under Article III have what effectively has come to mean life tenure (i.e., holding office "during good Behaviour").4 Along with the Supreme Court, the courts that constitute the Article III courts in the federal system are the U.S. circuit courts of appeals, the U.S. district courts, and the U.S. Court of International Trade.

As mentioned above, this report concerns nominations made by President Trump and other recent Presidents to the U.S. circuit courts of appeals and the U.S. district courts. Outside the scope of the report are the occasional nominations that these Presidents made to territorial district courts5 and the nine-member U.S. Court of International Trade.6

U.S. Courts of Appeals

The U.S. courts of appeals take appeals from federal district court decisions and are also empowered to review the decisions of many administrative agencies. Cases presented to the courts of appeals are generally considered by judges sitting in three-member panels. Courts within the courts of appeals system are often called "circuit courts" (e.g., the First Circuit Court of Appeals is also referred to as the "First Circuit"), because the nation is divided into 12 geographic circuits, each with a U.S. court of appeals.7 One additional nationwide circuit, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, has specialized subject matter jurisdiction.

Altogether, 179 judgeships for these 13 courts of appeals are currently authorized by law. The First Circuit (comprising Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico) has the fewest number of authorized appellate court judgeships, 6, while the Ninth Circuit (comprising Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) has the most, 29.

U.S. District Courts

U.S. district courts are the federal trial courts of general jurisdiction. There are 91 Article III district courts: 89 in the 50 states, plus one in the District of Columbia and one more in Puerto Rico. Each state has at least one U.S. district court, while some states (specifically California, New York, and Texas) have as many as four.

Altogether, 673 Article III U.S. district court judgeships are currently authorized by law.8 Congress has authorized between 1 and 28 judgeships for each district court. The Eastern District of Oklahoma (Muskogee) has 1 authorized judgeship, the smallest number among Article III district courts, while the Southern District of New York (Manhattan) and the Central District of California (Los Angeles) each have 28 judgeships, the most among Article III district courts.

U.S. Circuit and District Court Vacancies

Opportunities for a President to make circuit and district court appointments arise when judgeships are vacant or are scheduled to become vacant. Various factors influence the number of such opportunities a President will have during his tenure in office. One such factor, at the start of a presidency, is the number of judicial vacancies already in existence (i.e., the judicial vacancies a President inherits when taking office). The number of inherited vacancies, in turn, is influenced by various factors. These include the frequency with which judicial departures occurred and new judgeships were statutorily created in the years or months immediately prior to a new presidency; the extent to which the outgoing President, during this same period, made nominations to fill judicial vacancies; and the rate at which the Senate confirmed these nominations before the new President took office.

Table 1 reports the number of U.S. circuit and district court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the first and second years of a presidency, as well as the corresponding percentage of authorized circuit and district court judgeships that were vacant at these times.9

As shown by the table, the number of U.S. circuit court vacancies declined by 1, from 17 to 16, from the beginning of the first year to the beginning of the second year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of circuit court judgeships that were vacant at the beginning of President Trump's first year in office was 9.5%, while the percentage vacant at the beginning of his second year was 8.9%.

The number of U.S. district court vacancies increased by 38, from 86 to 124, from the beginning of the first year to the beginning of the second year of the Trump presidency. The percentage of district court judgeships that were vacant at the beginning of President Trump's first year in office was 12.8%, while the percentage vacant at the beginning of his second year was 18.4%.

Table 1. U.S. Circuit and District Court Vacancies at the Beginning of the First and Second Years of Select Presidencies

|

U.S. Circuit Court Judgeships |

U.S. District Court Judgeships |

|||||||

|

Beginning of First Year |

Beginning of Second Year |

Beginning of First Year |

Beginning of Second Year |

|||||

|

President |

# Vacant |

% Vacant |

# Vacant |

% Vacant |

# Vacant |

% Vacant |

# Vacant |

% Vacant |

|

Trump |

17 |

9.5 |

16 |

8.9 |

86 |

12.8 |

124 |

18.4 |

|

Obama |

13 |

7.3 |

19 |

10.6 |

40 |

5.9 |

81 |

12.0 |

|

Bush, G.W. |

26 |

14.5 |

30 |

16.8 |

54 |

8.2 |

66 |

10.0 |

|

Clinton |

17 |

9.5 |

22 |

12.3 |

90 |

14.0 |

95 |

14.7 |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Note: The vacancy data for the beginning of the first year of a presidency reflects vacancies that existed on January 1 prior to a President being inaugurated on January 20. The vacancy data for the beginning of the second year of a presidency reflects vacancies that existed on January 1 of the start of a President's second calendar year in office.

Percent Change in Number of Vacancies from Beginning of First Year to Beginning of Second Year of a Presidency

U.S. Circuit Courts

There was a 5.9% decrease (from 17 to 16) in the number of U.S. circuit court vacancies that existed at the beginning of President Trump's first year in office compared to the beginning of his second year.10

The largest percentage increase in the number of circuit court vacancies from the beginning of the first year to the beginning of the second year of a presidency occurred during the Obama presidency (a 46.2% increase from 13 to 19). The number of vacancies during the corresponding period of the George W. Bush presidency increased by 15.4% (from 26 to 30) and by 29.4% (from 17 to 22) during the Clinton presidency.

U.S. District Courts

There was a 44.2% increase (from 86 to 124) in the number of U.S. district court vacancies that existed at the beginning of President Trump's first year in office compared to the beginning of his second year. Of the four Presidents, this was the second-largest percentage increase in the number of district court vacancies from the beginning of the first year to the second year of a presidency.11

The largest percentage increase in the number of district court vacancies from the beginning of the first year to the beginning of the second year of a presidency occurred during the Obama presidency (a 102.5% increase from 40 to 81). The number of vacancies during the corresponding period of the George W. Bush presidency increased by 22.2% (from 54 to 66) and by 5.6% (from 90 to 95) during the Clinton presidency.

Long-Lasting Vacancies that Continued to Exist After a President's First Year

For each of the presidencies included in this part of the analysis, there continued to exist—after a President's first year in office—a number of long-lasting U.S. circuit and district court vacancies at the beginning of a President's second year in office. For the purposes of this report, these long-lasting judicial vacancies are defined as those judgeships that first became vacant during a prior presidency.

U.S. Circuit Courts

Of the 16 circuit court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the Trump presidency (i.e., vacant as of January 1, 2018), 10 (62.5%) had become vacant during the Obama presidency. The 10 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 368 days while President Obama was in office (with a median vacancy length of 119 days).12

Of the 19 circuit court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the Obama presidency (i.e., vacant as of January 1, 2010), 9 (47.4%) had become vacant during the George W. Bush presidency. The 9 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 1,308 days while President Bush was in office (with a median vacancy length of 820 days).

Of the 30 circuit court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the George W. Bush presidency (i.e., vacant as of January 1, 2002), 22 (73.3%) had become vacant during the Clinton presidency. The 22 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 741 days while President Clinton was in office (with a median vacancy length of 483 days).13

U.S. District Courts

Of the 124 district court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the Trump presidency, 79 (63.7%) had become vacant during the Obama presidency. The 79 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 612 days while President Obama was in office (with a median vacancy length of 449 days).

Of the 81 district court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the Obama presidency, 32 (39.5%) had become vacant during the George W. Bush presidency. The 32 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 410 days while President Bush was in office (with a median vacancy length of 278 days).

Of the 66 district court vacancies that existed at the beginning of the second year of the George W. Bush presidency, 38 (57.6%) had become vacant during the Clinton presidency. The 38 judgeships were vacant, on average, for 515 days while President Clinton was in office (with a median vacancy length of 354 days).14

Number and Percentage of Nominees Confirmed

Table 2 reports the number of individuals nominated to U.S. circuit and district court judgeships during President Trump's first calendar year in office (i.e., from January 20, 2017, through December 31, 2017), and also reports the number and percentage of nominees confirmed during the same period. The table also provides the same statistics for each of the first calendar years of his three immediate predecessors—Presidents Obama (2009), Bush (2001), and Clinton (1993).15

Table 2. U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees: Number Nominated, Number Confirmed, and Percentage Confirmed

First Year of Select Presidencies

|

U.S. Circuit Court Nominees |

U.S. District Court Nominees |

|||||||

|

President |

Year |

Number Nominated |

Number Confirmed |

Percentage Confirmed |

Number Nominated |

Number Confirmed |

Percentage Confirmed |

|

|

Trump |

2017 |

19 |

12 |

63% |

49 |

6 |

12% |

|

|

Obama |

2009 |

12 |

3 |

25% |

21 |

9 |

43% |

|

|

Bush, G.W. |

2001 |

29 |

6 |

21% |

36 |

22 |

61% |

|

|

Clinton |

1993 |

5 |

3 |

60% |

42 |

24 |

57% |

|

Source: Congressional Research Service.

U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

Overall, during his first year in office, President Trump nominated 19 individuals to U.S. circuit court judgeships, of whom 12 (or 63%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.16

Both the number and percentage of individuals confirmed as circuit court judges in 2017 were greater than the number and percentage of circuit court nominees confirmed during the first year of each of the other three presidencies included in Table 2.17

The number of individuals confirmed as U.S. circuit court judges during these other three years ranged from a low of 3 (during each of the first years of the Obama and Clinton presidencies) to a high of 6 (during the first year of the Bush presidency). The percentage of individuals confirmed during the first year of these three presidencies ranged from a low of 21% (during the first year of the Bush presidency) to a high of 60% (during the first year of the Clinton presidency).

In addition to having more circuit court nominees confirmed during his first year in office compared to each of the first years of his three immediate predecessors, the number of individuals confirmed as circuit court judges during President Trump's first year in office was also the greatest number of nominees confirmed to such judgeships during the first year of any presidency since at least 1945.18

Additionally, the percentage of nominees confirmed in 2017 (63%) was the highest percentage of circuit court nominees confirmed during the first year of any presidency since 1981 (when 8 of 9, or 89%, of circuit court nominees were confirmed during President Reagan's first year in office).19

U.S. District Court Nominees

During his first year in office, President Trump nominated 49 individuals to U.S. district court judgeships—of whom 6 (12%) were also confirmed during the first year of his presidency.

Both the number and percentage of individuals confirmed as district court judges in 2017 were lower than the number and percentage of such nominees confirmed during the first year of each of the other three presidencies included in Table 2.

The number of individuals confirmed as U.S. district court judges during these other three years ranged from a low of 9 (during the first year of the Obama presidency) to a high of 24 (during the first year of the Clinton presidency). The percentage of individuals confirmed during these three other years ranged from a low of 43% (also during the first year of the Obama presidency) to a high of 61% (during the first year of the Bush presidency).

In contrast to the postwar record high number of circuit court nominations confirmed during President Trump's first year in office, the number of individuals confirmed as district court judges (six) was the fewest number of district court nominees confirmed by the Senate during the first year of any presidency since at least 1945.20 The percentage of district court nominees confirmed (12%) was also the smallest percentage of district court nominees confirmed during the first year of any presidency for the same period.21

The first year of the Trump presidency is the second instance since 1945 of a President having fewer than half of the individuals he nominated to district court judgeships during his first year in office also confirmed by the Senate during his first year. The first instance of this occurring was during the Obama presidency in 2009, when fewer than half (43%) of President Obama's first-year district court nominees were also confirmed by the Senate during his first year in office.

The first year of the Trump presidency is also the third instance since 1945 of fewer than 10 district court nominees being confirmed by the Senate during a President's first year in office (with 6 confirmed in 2017).22 Prior to 2017, Presidents Obama and Eisenhower had the fewest number of district court nominees confirmed during the first year of a presidency (each had 9 confirmed in 2009 and 1953, respectively).23

Select Demographic Characteristics of Nominees

The demographic diversity of individuals nominated to U.S. circuit and district court judgeships during a President's first year in office has varied across recent presidencies.24 Note, though, that the numerical breakdown in the demographic characteristics of individuals a President nominates during his first year in office is not necessarily predictive of the final numerical breakdown in the characteristics of all the individuals he nominates during his entire term in office.25

U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

Gender

Figure 1 provides, for President Trump and his three immediate predecessors, the breakdown in the number and percentage of men and women appointed to U.S. circuit court judgeships during a President's first year in office. Of individuals nominated during President Trump's first year in office, 79% (15 of 19) were men and 21% (4) were women.

In terms of the percentage of individuals nominated during his first year in office, President Trump had—among the four Presidents—the lowest percentage of nominees who were women (21%). In terms of the number of nominees who were women, President Trump tied President Obama for nominating the second greatest number of women to circuit court judgeships during a President's first year in office (with 4 female nominees apiece).

Of the four Presidents, President Clinton had the greatest percentage of nominees who were women during his first year in office (60%), while President George W. Bush nominated the greatest number of women during his first year in office (7).

|

Figure 1. Number and Percentage of U.S. Circuit Court Nominees by Gender President's First Year in Office |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Race

Figure 2 shows the racial background of individuals nominated to U.S. circuit court judgeships during each President's first year in office. Of individuals nominated during President Trump's first year, 89% (17 of 19) were white and 11% (2) were Asian American. Of the four Presidents, President Trump had the greatest percentage and number of Asian American individuals among his first-year nominees (11% and 2, respectively).

Overall, of the four Presidents, President Trump had the smallest percentage of non-white individuals among his first-year nominees (11%). Each of the two non-white nominees during his first year in office was Asian American. No African American or Hispanic individuals were nominated to circuit court judgeships during this period.26 President Clinton had fewer non-white circuit court nominees during his first year in office (1 nominee compared to 2 for President Trump) but also nominated fewer individuals during his first year (4 nominees compared to 19 for President Trump).

|

Figure 2. Number and Percentage of U.S. Circuit Court Nominees by Race President's First Year in Office |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Of the four Presidents, President Obama nominated, during his first year in office, both the greatest percentage and number of non-white individuals to circuit court judgeships (50%, or 6 of 12 nominees). As shown by the figure, President Obama nominated the greatest percentage and number of African Americans to circuit court judgeships during his first year (33%, or 4 of 12 nominees) and, along with President George W. Bush, was one of two Presidents to nominate a Hispanic individual to a circuit court judgeship during his first year in office. President Obama was also, along with President Trump, one of two Presidents to nominate at least one Asian American to a circuit court judgeship during his first year.

Age at Time of Nomination

Of the four Presidents considered here, President Trump's first-year U.S. circuit court nominees were the youngest (both in terms of the average and median age at the time of nomination). The average age of his nominees when first nominated was 49, while the median age was 48.

President Obama's first-year circuit court nominees were the oldest (both in terms of the average and median age at the time of nomination). Both the average and median age of his nominees were 55.27

President Clinton's first-year circuit court nominees had an average age of 53 and a median age of 54, while President George W. Bush's first-year nominees had an average age of 50 and a median age of 49.

Overall, of President Trump's 19 first-year circuit court nominees, 58% (11 of 19) were under the age of 50 and 11% (2) were over the age of 55. In contrast, of President Obama's first-year circuit court nominees, 8% (1 of 12) was under the age of 50 and 33% (4) were over the age of 55.

Of President George W. Bush's first-year circuit court nominees, 52% (15 of 29) were under the age of 50 and 10% (3) were over the age of 55. Of President Clinton's first-year circuit court nominees, none were under the age of 50 and 20% (1 of 5) was over the age of 55.

U.S. District Court Nominees

Gender

Figure 3 provides the breakdown in the number and percentage of men and women appointed to U.S. district court judgeships during a President's first year in office. Of individuals nominated during President Trump's first year in office, 76% (37 of 49) were men and 24% (12) were women.

Of the four Presidents, President Trump nominated the lowest percentage of women to district court judgeships during his first year in office (24%). In terms of the number of women nominated during his first year, he nominated the second greatest number of women (12).

Of the four Presidents, President Obama nominated the greatest percentage of women during his first year in office (48%, or 10 of 21 nominees), while President Clinton nominated the greatest number of women during his first year (14).

|

Figure 3. Number and Percentage of U.S. District Court Nominees by Gender President's First Year in Office |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Race

Figure 4 shows the racial background of individuals nominated to U.S. district court judgeships during each President's first year in office. Of individuals nominated during President Trump's first year, 92% (45 of 49) were white, 4% (2) were Asian American, 2% (1) were African American, and 2% (1) were Hispanic. President Trump was, along with President Obama, one of two Presidents to nominate at least one Asian American to a district court judgeship his first year in office.

Overall, of the four Presidents, President Trump had the smallest percentage of non-white individuals among his first-year nominees (8%), as well as the fewest number of non-white nominees (4). Compared to the other three Presidents considered here, President Trump nominated the smallest percentage and fewest number of African American and Hispanic individuals to district court judgeships during his first year in office.

|

Figure 4. Number and Percentage of U.S. District Court Nominees by Race President's First Year in Office |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Overall, of the four Presidents, President Obama, during his first year, nominated both the greatest percentage and largest number of non-white individuals to district court judgeships (52%, or 11 of 21 nominees). President Obama had the greatest percentage of African Americans and Asian Americans among his first-year district court nominees (33% and 14%, respectively). He also had the largest number of Asian Americans among his first-year nominees (3). President Clinton had the largest number of African Americans among his first-year district court nominees (10), while President Bush had the greatest percentage and largest number of Hispanics among his first-year nominees (8% and 3).

Age at Time of Nomination

Of the four Presidents, President Trump's first-year district court nominees were the oldest (in terms of the average age at the time of nomination). The average age of his nominees when they were first nominated was 51. The median age was 50.

President Obama's first-year district court nominees had an average age of 50 and a median age of 51 (the oldest median age of district court nominees among the four Presidents). President George W. Bush's first-year nominees had an average age of 49 and a median age of 50, while President Clinton's first-year district court nominees had an average age of 49 and a median age of 48.

Overall, of President Trump's first-year district court nominees, 47% (23 of 49) were under the age of 50 and 29% (14) were over the age of 55.

Of President Obama's first-year district court nominees, 43% (9 of 21) were under the age of 50 and 24% (5) were over the age of 55. Of President George W. Bush's first-year district court nominees, 44% (16 of 36) were under the age of 50 and 19% (7) were over the age of 55. Of President Clinton's first-year district court nominees, 62% (26 of 42) were under the age of 50 and 14% (6) were over the age of 55.

Ratings of Nominees by the American Bar Association

Since 1953, every presidential Administration, except those of George W. Bush and Donald Trump, has sought ABA pre-nomination evaluations of its prospective U.S. circuit and district court nominees. During the Bush presidency, as well as during the current Administration, the ABA has provided post-nomination evaluations of nominees.

The ABA's Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary is responsible for evaluating all individuals nominated to U.S. circuit and district court judgeships. The committee is comprised of 15 lawyers with varied professional experiences and backgrounds. According to the ABA, the evaluation by the committee focuses strictly on a candidate's professional qualifications—specifically, a candidate's integrity, professional competence, and judicial temperament—and does not take into account an individual's philosophy, political affiliation, or ideology. Note that some have, at times, disputed this characterization.28

In evaluating integrity, the committee states that it "considers the prospective nominee's character and general reputation in the legal community, as well as the prospective nominee's industry and diligence."29 In evaluating professional competence, it assesses a prospective nominee's "intellectual capacity, judgment, writing and analytical abilities, knowledge of the law, and breadth of professional experience."30 And in evaluating judicial temperament the committee considers "the prospective nominee's compassion, decisiveness, open-mindedness, courtesy, patience, freedom from bias, and commitment to equal justice under the law."31

As stated above, the ABA, at present, provides post-nomination evaluations of individuals nominated to U.S. circuit and district court judgeships. At the conclusion of the evaluation process, each member of the ABA committee rates the candidate as "well qualified," "qualified," or "not qualified" and independently conveys his or her rating to the chair.32 If the candidate is found "not qualified" (either unanimously or by a majority of the committee), the committee determined that the nominee does "not meet the committee's standards with respect to one or more of its evaluation criteria—integrity, professional competence, or judicial temperament."33

There are instances when the committee is not unanimous in its rating of a nominee. When this happens, "the majority rating represents the committee's official rating of the prospective nominee."34 The statistics presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6 reflect the percentage and numerical breakdown of the committee's official ratings for individuals nominated during each President's first year in office (whether that rating was unanimous or supported by a majority of the committee).

The evaluations of judicial candidates are provided by the ABA on an advisory basis. It is solely in a President's discretion as to how much weight to place on a judicial candidate's ABA rating. Consequently, a "not qualified" ABA rating of a judicial candidate in some instances may dissuade a President from nominating an individual, while in other instances the President may nominate regardless of the rating. The evaluations submitted by the ABA are similarly advisory when it comes to final Senate action on judicial nominations.

U.S. Circuit Court Nominees

As shown by Figure 5, of President Trump's U.S. circuit court nominees, 84% (16 of 19) received a rating of well qualified, 11% (2) received a rating of qualified, and 5% (1) received a rating of not qualified.

The percentage of President Trump's first-year circuit court nominees who received a rating of well-qualified (84%) was the second highest among the four Presidents (with 100% of President Clinton's first-year circuit court nominees having received a rating of well qualified).

As shown by Figure 5, a majority of a President's circuit court nominees have, at least for the data included here, received a rating of "well qualified." Consequently, a President who submits relatively more nominations is also likely to have more nominees who are rated as well qualified than a President who submits fewer nominations. For example, of the four presidencies examined here, Presidents Bush and Trump submitted the greatest number of circuit court nominations to the Senate during each of their first years in office. President Trump had the second greatest number of nominees rated as well qualified (while President George W. Bush had the most nominees rated as well qualified).

Of the four Presidents considered here, President Trump had the only U.S. circuit court nominee who was rated as not qualified by the ABA during the first year of a presidency.35

U.S. District Court Nominees

As shown by Figure 6, of President Trump's U.S. district court nominees, 53% (26 of 49) received a rating of well qualified, 41% (20) received a rating of qualified, and 6% (3) received a rating of not qualified.

The percentage of President Trump's first-year U.S. district court nominees who received a rating of well qualified, 53%, was the lowest percentage of nominees among the four Presidents who received a rating of well qualified (while the percentage of his nominees who received a rating of qualified was 41%). President Obama had the highest percentage of his first-year district court nominees rated as well qualified (86%).

As shown by Figure 6, a majority of a President's district court nominees have, at least for the data included here, received a rating of "well qualified." Consequently, a President who submits relatively more nominations is also likely to have more nominees who are rated as well qualified than a President who submits fewer nominations. For example, of the four presidencies examined here, President Trump submitted the greatest number of district court nominations to the Senate during his first year in office, and he also had the second greatest number of nominees rated as well qualified. And President Clinton submitted the second greatest number of district court nominations and had the greatest number who received a rating of well qualified.

Of the four Presidents, President Trump had both the greatest percentage (6%) and number (3) of first-year U.S. district court nominees who were rated as not qualified by the ABA.36 Presidents Bush and Clinton each had one first-year district court nominee rated as not qualified.

Of the four Presidents considered here, President Trump is also the sole President to have at least one circuit court nominee and at least one district court nominee rated as not qualified during his first year in office.

Time from Nomination to Confirmation

Table 3 reports the average and median number of days that elapsed from nomination to confirmation for all U.S. circuit and district court nominees who were confirmed during a President's first year in office.37 As shown by the table, the average number of days from nomination to confirmation for U.S. circuit and district court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office was 115 days. The median number of days from nomination to confirmation was 109 days.

Table 3. Average and Median Number of Days from Nomination to Confirmation for Nominees Confirmed During First Year of Presidency

U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees, Combined

|

Number of Days from Nomination to Confirmation |

||||

|

President |

Year |

Total Number of Nominees Confirmed |

Average |

Median |

|

Trump |

2017 |

18 |

115 |

109 |

|

Obama |

2009 |

12 |

137 |

130 |

|

Bush, G.W. |

2001 |

28 |

108 |

96 |

|

Clinton |

1993 |

27 |

52 |

55 |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Of the four Presidents included in the table, President Trump's first-year nominees had the second longest average and median number of days from nomination to confirmation (President Obama's nominees had the longest average and median—137 and 130 days, respectively).

The average and median number of days from nomination to confirmation for President Trump's first-year nominees represent a departure from the upward trend in the length of time first-year nominees waited to be confirmed during the previous three presidencies. Specifically, it is the first instance over the past several presidencies in which the average and median wait times from nomination to confirmation of a President's first-year nominees were both shorter than the average and median wait times of his immediate predecessor's first-year nominees.38

The decline in the average and median wait times for President Trump's first-year nominees (relative to President Obama's first-year nominees) occurred, in part, as a result of the shorter time nominees waited on the Executive Calendar to be confirmed once reported by the Senate Judiciary Committee. For example, President Trump's first-year nominees waited, on average, 34 days from committee report to confirmation (with a median wait of 19 days). In contrast, President Obama's first-year nominees waited, on average, 60 days from committee report to confirmation (with a median wait of 43 days).

Table 4 reports, for nominees confirmed during a President's first year in office, the number of U.S. circuit and district court nominees who waited a specified period of time from nomination to confirmation. For example, of the 12 U.S. circuit court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office, 6 were confirmed less than 100 days after being nominated; 4 were confirmed between 100 and 149 days after being nominated; 2 were confirmed between 150 and 200 days after being nominated; and none waited more than 200 days to be confirmed.

Table 4. Number of U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees Waiting Specified Period of Time from Nomination to Confirmation

Nominees Confirmed During First Year of Presidency

|

|

Number of Days from Nomination to Confirmation |

|||||

|

President |

Type of Court |

Number of Nominees Confirmed |

Less than 100 |

100 to 149 |

150 to 200 |

More than 200 |

|

Trump |

Circuit |

12 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

|

District |

6 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Obama |

Circuit |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

District |

9 |

2 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Bush, G.W. |

Circuit |

6 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

District |

22 |

15 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Clinton |

Circuit |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

District |

24 |

21 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Source: Congressional Research Service.

As shown by Table 4, the first year of the Trump presidency is the first time since 1993 (the first year of the Clinton presidency) when at least half of a President's first-year circuit court nominees were confirmed within fewer than 100 days after being nominated.39

One of President Trump's circuit court nominees, James C. Ho, was confirmed 59 days after being nominated. Another one of his circuit court nominees, Amul R. Thapar, was confirmed 65 days after being nominated. These were the shortest wait times, since 1993,40 from nomination to confirmation for any U.S. circuit court nominee confirmed during a President's first year in office.

President Trump's U.S. district court nominees were distributed equally across three of the specified periods of time—two waited less than 100 days from nomination to confirmation; two waited between 100 and 149 days; and two waited 150 to 200 days.

As shown by the table, President Trump was, of the four Presidents, the sole President who had at least one-third of his district court nominees (2 of 6) wait 150 or more days from nomination to confirmation.41

One of President Trump's district court nominees, Dabney L. Friedrich, was confirmed 173 days after being nominated. Another of his district court nominees, Scott L. Palk, was confirmed 171 days after being nominated.42 These were the longest wait times, since 2001,43 from nomination to confirmation for any U.S. district court nominee confirmed during a President's first year in office.

Floor Consideration of Nominations

Floor consideration of U.S. circuit and district court nominations during the first year of the Trump presidency frequently involved the use of the cloture process to reach Senate confirmation. Additionally, the confirmation of nominees always occurred by roll call vote (rather than by unanimous consent or voice vote) and, for most circuit court nominations, was marked by a relatively high number of 'nay' votes among Senators not belonging to the President's party.

Use of Cloture to Reach Confirmation

In practice, Senate floor consideration of U.S. circuit or district court nominations follows one of two procedural tracks.44 Historically, most of these nominations have reached confirmation under the terms of unanimous consent agreements. On this procedural track, the Senate by unanimous consent not only takes up nominations for floor consideration, but also arranges for them to either receive up-or-down confirmation votes or be confirmed simply by unanimous consent.45

At other times, however, unanimous consent to reach confirmation may not always be attainable. In these instances, the procedural track, for a nomination to move forward without unanimous consent, involves the Senate, after taking up the nomination, voting on a cloture motion to bring floor debate to a close. If the requisite majority under Senate rules supports closing debate, an "up-or-down" confirmation vote on the nomination must be held after a limited period for consideration.46

During the first year of the Trump presidency, the cloture process (rather than unanimous consent) has been the primary means by which confirmation votes have been reached on U.S. circuit and district court nominations. Cloture was used for each of the 12 circuit court nominations that received a final up-or-down vote and for 5 of the 6 district court nominations that received a final vote. In contrast, during the first years of the other three presidencies included in this report's analysis, the cloture process was used once to reach an up-or-down vote on a circuit or district court nomination.47

The routine use of cloture to reach final votes on U.S. circuit and district court nominations also occurred recently during the Obama presidency (although, as discussed above, not during his first year in office). For 13 months following the November 21, 2013, reinterpretation of Rule XXII (i.e., during part of President Obama's fifth year in office and most of his sixth year in office), votes on confirmation, including for uncontroversial judicial nominations, no longer were reached by unanimous consent, but instead by the cloture process.48

Overall, the cloture process was used a total of 85 times during this period of the Obama presidency to reach up-or-down votes on U.S. circuit and district court nominations.49 Used primarily in the past to close debate on a relatively small number of nominations that did not enjoy wide bipartisan support, the cloture motion became, until the last day of the 113th Congress, the invariable procedural tool used to reach confirmation votes for circuit and district court nominations.50

Use of Roll Call Votes to Confirm Nominees

The Senate may confirm nominations by unanimous consent, voice vote, or by recorded roll call vote. When the question of whether to confirm a nomination is put to the Senate, a roll call vote will be taken on the nomination if the Senate has ordered "the yeas and nays."

Historically, the Senate has confirmed most district and circuit court nominations by unanimous consent or by voice vote. In recent decades, however, confirmations by roll call votes have become more common, and during the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, they were the most common way that the Senate confirmed lower court nominations.51

For the purposes of this report and the data reported below, any nominations that were confirmed by unanimous consent or confirmed by voice vote are included in the same category (i.e., the nominations were not approved by roll call vote).

Of the four presidencies included in Table 5, the Trump presidency is the only one in which all of a President's first-year circuit and district court nominees were confirmed by roll call vote. Specifically, as shown by the table, each of the 12 U.S. circuit court nominees and 6 U.S. district court nominees confirmed in 2017 were approved by roll call vote (and none by voice vote or unanimous consent).

As was the case with President Trump's first-year circuit court nominees, all of the circuit court nominees confirmed during each of the first years of the Obama and George W. Bush presidencies were confirmed by roll call vote.

Table 5. Frequency of Confirmation by Voice Vote/Unanimous Consent or Roll Call Vote

Nominees Confirmed During the First Year of a Presidency

|

Number of Nominees Confirmed by |

||||

|

President |

Court Type |

Number of Nominees Confirmed |

Voice Vote |

Roll Call Vote |

|

Trump |

Circuit |

12 |

0 |

12 |

|

District |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

|

Obama |

Circuit |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

District |

9 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

G.W. Bush |

Circuit |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

District |

22 |

7 |

15 |

|

|

Clinton |

Circuit |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

District |

24 |

24 |

0 |

|

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Notes: For the purposes of this report, any nominations that were confirmed by unanimous consent or confirmed by voice vote are included in the same category (i.e., the nominations were not approved by roll call vote).

In contrast to each of President Trump's first-year district court nominees being confirmed by roll call vote, 4 of 9 of President Obama's first-year district court nominees and 7 of 22 of President George W. Bush's first-year district court nominees were confirmed by voice vote or unanimous consent.

Each of the circuit and district court nominees confirmed during the first year of the Clinton presidency were confirmed by voice vote or unanimous consent.

There are a number of institutional and political factors that may, in part, help to explain the more common occurrence, since the mid-1990s, of roll call votes being used to confirm U.S. circuit and district court nominees (including for many nominees considered uncontroversial).52 Some scholars, for example, have noted that as the confirmation process itself has become more contentious, Senators might use roll call votes for many, if not all, nominations as a way to slow down the process or to indicate their concerns, more generally, with the judicial appointment process.53 Roll call votes might also provide Senators who are motivated by ideological or policy considerations with a way to express their views about, or attempt to influence, the appointment process.54 Additionally, the use of roll call votes allows Senators to go on record in support or opposition to a President's nominees. Such position-taking by Senators might be important to constituents, political activists, and various interest groups.55

Number of 'Nay' Votes Received at Time of Confirmation

Table 6 reports, for U.S. circuit and district court nominees who were confirmed by roll call vote during the first year of a presidency, the number of 'nay' votes his or her nomination received at the time of confirmation.

Table 6. Number of 'Nay' Votes Received at Time of Confirmation

Nominees Confirmed During the First Year of a Presidency

|

Confirmed by Roll Call Vote - Number of NAYs Received |

||||||||

|

President |

Court Type |

0 |

1 to 5 |

6 to 10 |

11 to 15 |

16 to 20 |

More than 20 |

Total Confirmed by Roll Call Vote |

|

Trump |

Circuit |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

11 |

12 |

|

District |

2 |

2 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

6 |

|

|

Obama |

Circuit |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

District |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

|

|

Bush, G.W. |

Circuit |

5 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

|

District |

15 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

15 |

|

|

Clinton |

Circuit |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

|

District |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

|

Source: Congressional Research Service.

As shown by the table, 11 of 12 U.S. circuit court nominations that were approved by the Senate during President Trump's first year in office received more than 20 nay votes at the time of confirmation. Of these 11 nominations, the average number of nay votes was 43 (the median number of nay votes was also 43). No other presidency included in the table had as many circuit court nominees who were opposed by 20 or more Senators in recorded roll call votes.

Of the six district court nominees confirmed during President Trump's first year in office, two were confirmed without receiving any nay votes while the other four nominees confirmed received at least one nay vote.

Two of the district court nominees confirmed during the first year of the Trump presidency, Scott L. Palk and Trevor N. McFadden, were, of the total 22 district court nominees confirmed by roll call vote during the first years of the Trump, Obama, and Bush presidencies, the only two district court nominees who received any nay votes at the time of confirmation (none of President Clinton's first-year district court nominees were confirmed by roll call vote).56

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Amber Wilhelm, Graphics Specialist in the Publishing and Editorial Resources Section of CRS, for her work on the figures included in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, for example, Sen. Chuck Grassley, "Executive Session," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, May 16, 2016, p. S2811. See also Sen. Dianne Feinstein, "Executive Session," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, December 14, 2017, p. S8024. |

| 2. |

See, for example, views on these and related issues in floor remarks by Senators Grassley and Feinstein in "Nominations," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, May 5, 2014, p. S2635 (Grassley); and in "Executive Calendar," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, November 2, 2017, p. S6985 (Feinstein). |

| 3. |

See, for example, floor remarks by Senator Feinstein, "Executive Session," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, December 14, 2017, pp. SS8023-SS8024. See also floor remarks by Senator Blunt, "Executive Session," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, daily edition, December, 13, 2017, p. S7991. |

| 4. |

Pursuant to this constitutional language, Article III judges may hold office for as long as they live or until they voluntarily leave office. A President has no power to remove them from office. Article III judges, however, may be removed by Congress through the process of impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate. |

| 5. |

The territorial district courts were established by Congress pursuant to its authority to govern the territories under Article IV of the Constitution. Judicial appointees to these territorial judgeships serve 10-year terms, with one judgeship each in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, and two in the U.S. Virgin Islands. While American Samoa is an overseas territory of the United States, it does not have a federal district court and has not been incorporated into a federal judicial district. The High Court of American Samoa is the court of general jurisdiction for the territory. The High Court has limited jurisdiction to hear cases under particular federal statutes. See Michael W. Weaver, "The Territory Federal Jurisdiction Forgot: The Question Of Greater Federal Jurisdiction In American Samoa," Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association, vol. 17 (March 2008), p. 325. |

| 6. |

The predecessors of the U.S. Court of International Trade were the Board of General Appraisers (1890-1926) and the U.S. Customs Court (1926-1980), both of which were responsible for resolving controversies related to appraisals of imported goods and the classification of tariffs. In 1956, a congressional act declared that the U.S. Customs Court was established under Article III of the Constitution, thereby "extending to the judges [on the court] the same rights to tenure and undiminished salary that were guaranteed to judges of the district and appellate courts." See Federal Judicial Center, "U.S. Customs Court, 1926-1980," online at https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/u.s.-customs-court-1926-1980. In 1980, Congress reorganized the U.S. Customs Court as the U.S. Court of International Trade. In reorganizing the Court, "Congress signaled its intention to use the expertise of the Court of International Trade ... to handle the federal judiciary's trade litigation, which was much more likely to concern enforcement of trade agreements than disputes about tariffs." See Federal Judicial Center, "U.S. Court of International Trade, 1980-Present," online at https://www.fjc.gov/history/courts/u.s.-court-international-trade-1980-present. |

| 7. |

In this report, nominations to U.S. courts of appeals judgeships are frequently referred to as "circuit court nominations." |

| 8. |

This total includes 10 temporary judgeships. See the U.S. Courts website at http://www.uscourts.gov/JudgesAndJudgeships/AuthorizedJudgeships.aspx. |

| 9. |

The percentage of U.S. circuit and district court judgeships that were vacant is calculated by dividing the number of circuit or district court vacancies that existed on a particular date by the number of authorized circuit or district court judgeships that were authorized on that same date. Note that, over the course of the four presidencies included in this analysis, the number of authorized circuit court judgeships remained constant (179 judgeships). The number of authorized district court judgeships, however, varied (645 judgeships authorized during the Clinton presidency, 661 during the Bush presidency, and 673 during the Obama and Trump presidencies). |

| 10. |

Of the four Presidents considered here, he was the only one for whom the number of circuit court vacancies declined from the beginning of his first year in office to the beginning of his second year. |

| 11. |

It is also, of the four presidencies considered here, the only instance of there being more than 100 district court vacancies at either the beginning of the first or second year of a presidency. |

| 12. |

The average is the arithmetic mean, while the median indicates the middle value for a particular set of numbers. In this case, the median is the middle value for the number of days each vacancy existed during a particular presidency. Although the average (also referred to as the mean) is the more commonly used measure, the median is less affected by outliers or extreme cases, e.g., vacancies that existed for an unusually long or short amount of time. Consequently, the median might be a better measure of central tendency. |

| 13. |

A detailed list of vacancies (rather than summary statistics) for the beginning of the second year of the Clinton presidency is not available and, thus, is not included in this part of the analysis. |

| 14. |

As noted in the discussion of circuit court vacancies, a detailed list of vacancies (rather than summary statistics) for the beginning of the second year of the Clinton is not available and, thus, is not included in this part of the analysis. |

| 15. |

For the purpose of this report, a President's first year in office is considered the period of time from his inauguration on January 20 of his first year to December 31 of the same year. |

| 16. |

The seven individuals who were not confirmed during the first year of the Trump presidency were returned to the President under the provisions of Senate Rule XXXI, paragraph 6 of the Standing Rules of the Senate. Each of the individuals was renominated by President Trump in 2018 during the second session of the 115th Congress (which corresponds to the second calendar year of the Trump presidency). |

| 17. |

A determination of a President's success, relative to other Presidents, in having his nominees confirmed by the Senate might depend, in part, upon whether one considers the number or percentage of nominations approved by the Senate as the primary criterion in measuring a President's success. The number of a President's nominations approved by the Senate represents the actual number of individuals appointed to the federal bench by a President. Even if a relatively large number of a President's nominees are not confirmed by the Senate, a relatively large number of his nominees might nonetheless still be confirmed (i.e., the two are not mutually exclusive). Consequently, a President might still have a similar impact as his predecessors on the makeup of the federal judiciary by virtue of the total number of his nominees confirmed by the Senate. In contrast, the percentage of a President's nominations approved by the Senate represents the fact that there is variation in the overall number of judicial nominations submitted by different Presidents to the Senate. Variation in the number of nominations submitted by a President reflects, in part, the number of vacancies that exist during that President's time in office. Given that the number of authorized judgeships is relatively fixed (barring the creation of new judgeships), it is possible that a President might prefer to have a relatively greater number of his nominees appointed to the bench rather than a relatively greater percentage of his nominees. For example, a President might be likely to prefer to have appointed 50 U.S. circuit court judges (representing 28% of all authorized circuit court judgeships)—even if he nominated 100 individuals to such judgeships (for a 50% confirmation rate)—rather than to have appointed 25 U.S. circuit court judges (representing 14% of all authorized circuit court judgeships) after having nominated 30 individuals to such judgeships (for an 83% confirmation rate). Note, though, that another President might be more focused on the percentage of nominations approved as a measure of success. |

| 18. |

The previous record for the most circuit court nominations confirmed during the first year of a presidency in the postwar period was shared by Presidents Kennedy and Nixon—each of whom had 11 nominees confirmed in 1961 and 1969, respectively. |

| 19. |

Of the 10 Presidents during the postwar period who assumed office following a general election rather than as the result of an incumbent President's death or resignation (i.e., excluding Presidents Truman, Johnson, and Ford), the record for the greatest percentage of circuit court nominees confirmed during a first year is held by President Carter (100%) followed by Presidents Reagan (89%), Nixon (85%), and Kennedy (73%). |

| 20. |

Previously during the postwar period the fewest number of district court nominees were confirmed during the first years of the Eisenhower and Obama presidencies—when nine nominees were confirmed in 1953 and 2009, respectively. During President Truman's partial first year in office (1945), the Senate confirmed 10 district court nominees. During President Ford's partial first year (1974), the Senate confirmed 11 district court nominees. President Johnson did not have any nominees confirmed for the approximately five weeks he served as President in 1963. However, during the first full year he was in office—from November 22, 1963, through November 21, 1964, the Senate confirmed 14 district court nominees. |

| 21. |

Previously during the postwar period the smallest percentage of district court nominations confirmed during the first year of a presidency occurred during the Obama presidency, when 43% of those nominated were confirmed that same year. |

| 22. |

Excluding President Johnson's abbreviated year in 1963. |

| 23. |

In contrast to the first year of the Obama presidency, however, all nine of President Eisenhower's district court nominees were also confirmed during his first year in office (i.e., for a 100% confirmation rate in 1953). |

| 24. |

For additional information related to the demographic characteristics of federal judges see CRS Report R43426, U.S. Circuit and District Court Judges: Profile of Select Characteristics, by [author name scrubbed]. See also CRS Insight IN10754, Select Demographic and Other Characteristics of Recent U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 25. |

For example, of those individuals nominated to circuit and district court judgeships by President Obama during his first year in office, two (6.1%) were Hispanic. In contrast, of all the individuals nominated to U.S. circuit and district court judgeships by the end of his presidency, 37 (9.6%) were Hispanic. |

| 26. |

Of the four Presidents, President Trump was the only President not to nominate an African American individual to a circuit court judgeship and was one of two (along with President Clinton) not to nominate an Hispanic individual to a circuit court judgeship. |

| 27. |

There is likely a positive relationship between the age of a nominee when appointed to the bench and the length of time he or she serves as an active judge prior to retiring, resigning, assuming senior status, or dying while in active service. For example, of the 55 U.S. circuit court nominees appointed by President Obama during his time in office, 2 have since stepped down from active service. Both were over the age of 55 at the time of being appointed to the bench. Or, for example, of President Clinton's 26 first-year district court nominees who were appointed while under the age of 50, 8 (30.8%) are still serving as active judges while none of the 6 individuals he appointed during his first year who were over the age of 55 are still serving as active judges. |

| 28. |

See, for example, Seung Min Kim and John Bresnahan, "Republicans step up defense of 'not qualified' judicial nominees," Politico, December 10, 2017, online at https://www.politico.com/story/2017/12/10/trump-judicial-nominees-republicans-287911. |

| 29. |

American Bar Association, Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary, What It Is and How It Works (2017), p. 3, online at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/uncategorized/GAO/Backgrounder.authcheckdam.pdf (hereinafter ABA, What It Is and How It Works). |

| 30. |

Ibid. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

For additional discussion and historical analysis of the "Not Qualified" rating given by the American Bar Association to U.S. circuit and district court nominees, see CRS Insight IN10814, U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees Who Received a Rating of "Not Qualified" from the American Bar Association: Background and Historical Analysis, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 33. |

ABA, What It Is and How It Works, p. 6. |

| 34. |

Ibid., p. 7. Of the ratings given to President Trump's first-year nominees, the committee's ratings were more often unanimous than not. Of President Trump's 19 first-year U.S. circuit court nominees, 13 (68%) received a unanimous rating from the committee—whether that rating was well qualified, qualified, or not qualified—while 6 (32%) received a rating that was not unanimous among committee members. Of President Trump's 49 first-year U.S. district court nominees, 30 (61%) received a unanimous rating from the committee while 19 (39%) received a rating that was not unanimous among committee members. |

| 35. |

Specifically, L. Steven Grasz, nominated by President Trump to the Eighth Circuit, received a unanimous rating of not qualified. He was confirmed by the Senate on a party-line vote of 50-48 on December 12, 2017. See CBS/AP, "Leonard Steven Grasz, Trump judicial pick rated 'not qualified,' OK'd by Senate," December 13, 2017, online at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/leonard-steven-grasz-trump-judicial-pick-not-qualified-okd-senate. Prior to the Grasz confirmation, the last U.S. circuit court nominee rated as not qualified by the ABA and confirmed by the Senate was Thomas J. Meskill. He was nominated by President Ford to the Second Circuit on January 16, 1975, and confirmed by a vote of 54-36 in the Senate on April 22, 1975. |

| 36. |

One of the district court nominees, Brett J. Talley, was not confirmed by the Senate. His nomination was returned to the President on January 3, 2018, and not resubmitted to the Senate for consideration. The nominations of the other two nominees who received not qualified ratings (Charles B. Goodwin and Holly Lou Teeter) are, as of April 25, 2017, pending on the Senate Executive Calendar. The last U.S. district court nominee rated as not qualified by the ABA and confirmed by the Senate was Gregory F. Van Tatenhove. He was nominated by President G.W. Bush to the Eastern District of Kentucky on September 13, 2005, and confirmed by voice vote in the Senate on December 21, 2005. |

| 37. |

As noted previously, the average is the arithmetic mean, while the median indicates the middle value for a particular set of numbers. In this case, the median is the middle value for the number of days from nomination to confirmation for a particular President's circuit or district court nominees. Although the average (also referred to as the mean) is the more commonly used measure, the median is less affected by outliers or extreme cases, e.g., nominees whose elapsed time from first nomination to confirmation was unusually long or short. Consequently, the median might be a better measure of central tendency. |

| 38. |

Although the Carter, Reagan, and G.H.W. Bush presidencies are not represented in Table 3, the decline in the average and median wait times from nomination to confirmation for President Trump's first-year nominees is only the second such decline in wait times since at least the Reagan presidency. The average and median number of days from nomination to confirmation for first-year nominees increased from the Carter to the Reagan presidency and from the Reagan to the G.H.W. Bush presidency. The average and median wait times decreased from the G.H.W. Bush presidency to the Clinton presidency. |

| 39. |

The relatively faster speed by which President Trump's circuit court nominees were confirmed likely contributed to the record high number of circuit court nominees who were confirmed during a President's first year in office (and discussed above in the section of the report titled "Number and Percentage of Nominees Confirmed"). |

| 40. |

In 1993, M. Blaine Michael was confirmed 55 days after being nominated by President Clinton. |

| 41. |

The relatively slower speed by which President Trump's district court nominees were confirmed likely contributed to the record low number of district court nominees who were confirmed during a President's first year in office (and discussed above in the section of the report titled "Number and Percentage of Nominees Confirmed"). |

| 42. |

Note that Scott L. Palk was first nominated by President Obama for the same judgeship on December 16, 2015. He is one of several U.S. district court nominees who were first nominated during the 7th or 8th year of the Obama presidency, did not receive a floor vote during the Obama presidency, and were subsequently renominated during the Trump presidency. |

| 43. |

In 2001, John D. Bates was confirmed 174 days after being nominated by President George W. Bush. |

| 44. |

For an in-depth discussion of the procedures used by the Senate to process U.S. circuit and district court nominations see CRS Report R43762, The Appointment Process for U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations: An Overview, by [author name scrubbed]. The procedural information provided in this section draws on that report. |

| 45. |

Senate floor consideration of a judicial nomination by unanimous consent typically is scheduled by the majority leader in consultation with the minority leader and with all interested Senators. The majority leader, in such consultation, ordinarily seeks to establish that, if requested on the floor, no Senator will object to the nomination receiving a vote on confirmation. If this can be established, the leader will make the unanimous consent request at a convenient agreed-upon time. |

| 46. |

Following the reinterpretation, on November 21, 2013, of the application of Rule XXII to floor consideration of presidential nominations (and the continued use of the reinterpretation of Rule XXII since that date), the vote threshold by which cloture is invoked on a nomination is a simple majority of Senators voting on a cloture motion, provided a minimal quorum of 51 is present, rather than three-fifths of the Senate. For further discussion of the reinterpretation of Rule XXII during the 113th Congress see CRS Report R43331, Majority Cloture for Nominations: Implications and the "Nuclear" Proceedings of November 21, 2013, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 47. |