Cross-Border Data Sharing Under the CLOUD Act

Law enforcement officials in the United States and abroad increasingly seek access to electronic communications, such as emails and social media posts, stored on servers and in data centers in foreign countries. Because the architecture of the internet allows technology companies to store data at a great distance from the physical location of their customers, electronic communications that could serve as evidence of a crime often are not housed in the same country where the crime occurred. This disconnect has caused governments around the world, including the United States, to seek data stored outside their territorial jurisdictions. In the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act, Congress enacted one of the first major changes in years to U.S. law governing cross-border access to electronic communications held by private companies.

The CLOUD Act has two major components. The first facet addresses the U.S. government’s ability to compel technology companies to disclose the contents of electronic communications stored on the companies’ servers and data centers overseas. The Stored Communications Act (SCA) mandates that certain technology companies disclose the contents of electronic communications pursuant to warrants issued by U.S. courts based on probable cause that the communications contain evidence of a crime. But a dispute arose over whether warrants issued under the SCA could compel disclosure of data held outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. While the Supreme Court was set to resolve this issue in United States v. Microsoft, the CLOUD Act amended the SCA to require that technology companies provide data in their possession, custody, or control in response to an SCA warrant—regardless of whether the data is located in the United States. On April 17, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the change in law mooted the Microsoft case.

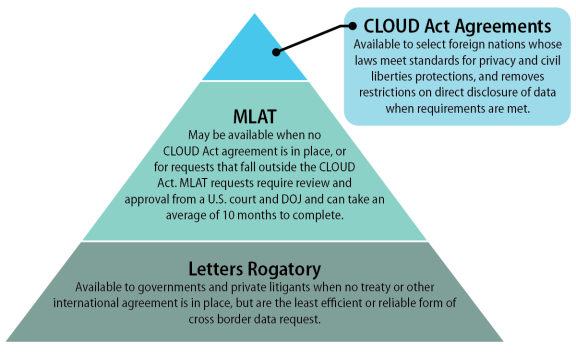

The second facet of the CLOUD Act addresses the reciprocal issue of foreign governments’ ability to access data in the United States as part of their investigation and prosecution of crimes. Prior to the CLOUD Act, foreign nations seeking data in the United States were required to request the assistance of the U.S. government through either mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs) or judicial instruments known as letters rogatory. Requests under either instrument are reviewed by U.S. courts before disclosure to the foreign nation can be authorized, but U.S. and foreign officials criticized the processes as inefficient and unable to accommodate the increasing number of data requests in the digital era.

The CLOUD Act responds to calls for modernization by authorizing the executive branch to conclude a new form of international agreement through which select foreign governments can seek data directly from U.S. technology companies without individualized review by the U.S. government. Agreements authorized by the CLOUD Act would remove legal restrictions on certain foreign nations’ ability to seek data directly from U.S. providers in cases involving “serious crimes” when not targeting U.S. persons, provided the Executive has determined that the foreign nation’s laws adequately protect privacy and civil liberties, among other requirements. While the CLOUD Act conditions approval of covered agreements upon a host of restrictions, commentators debate whether these agreements will provide adequate protections for privacy, human rights, and civil liberties.

Cross-Border Data Sharing Under the CLOUD Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview of ECPA and the SCA

- Prohibitions on Disclosure Under the SCA

- Mandatory Disclosure Under the SCA

- United States v. Microsoft Corp. and the CLOUD Act

- The Legislative Response to Microsoft in the CLOUD Act

- Resolving Conflicts with Foreign Law

- International Data Sharing After the CLOUD Act

- Letters Rogatory

- Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs)

- Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act

- Requirements for CLOUD Act Agreements

- Limitations on Orders Issued Under CLOUD Act Agreements

- Mandatory Rights Granted to the United States

- Judicial or Governmental Review of Orders Under CLOUD Act Agreements

- What Nations Are Eligible for CLOUD Act Agreements?

- Congressional Review of CLOUD Act Agreements

- Commentary on the CLOUD Act

- How Will CLOUD Act Agreements Interact with Existing Data Sharing Processes?

- Conclusion

Summary

Law enforcement officials in the United States and abroad increasingly seek access to electronic communications, such as emails and social media posts, stored on servers and in data centers in foreign countries. Because the architecture of the internet allows technology companies to store data at a great distance from the physical location of their customers, electronic communications that could serve as evidence of a crime often are not housed in the same country where the crime occurred. This disconnect has caused governments around the world, including the United States, to seek data stored outside their territorial jurisdictions. In the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act, Congress enacted one of the first major changes in years to U.S. law governing cross-border access to electronic communications held by private companies.

The CLOUD Act has two major components. The first facet addresses the U.S. government's ability to compel technology companies to disclose the contents of electronic communications stored on the companies' servers and data centers overseas. The Stored Communications Act (SCA) mandates that certain technology companies disclose the contents of electronic communications pursuant to warrants issued by U.S. courts based on probable cause that the communications contain evidence of a crime. But a dispute arose over whether warrants issued under the SCA could compel disclosure of data held outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. While the Supreme Court was set to resolve this issue in United States v. Microsoft, the CLOUD Act amended the SCA to require that technology companies provide data in their possession, custody, or control in response to an SCA warrant—regardless of whether the data is located in the United States. On April 17, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled that the change in law mooted the Microsoft case.

The second facet of the CLOUD Act addresses the reciprocal issue of foreign governments' ability to access data in the United States as part of their investigation and prosecution of crimes. Prior to the CLOUD Act, foreign nations seeking data in the United States were required to request the assistance of the U.S. government through either mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs) or judicial instruments known as letters rogatory. Requests under either instrument are reviewed by U.S. courts before disclosure to the foreign nation can be authorized, but U.S. and foreign officials criticized the processes as inefficient and unable to accommodate the increasing number of data requests in the digital era.

The CLOUD Act responds to calls for modernization by authorizing the executive branch to conclude a new form of international agreement through which select foreign governments can seek data directly from U.S. technology companies without individualized review by the U.S. government. Agreements authorized by the CLOUD Act would remove legal restrictions on certain foreign nations' ability to seek data directly from U.S. providers in cases involving "serious crimes" when not targeting U.S. persons, provided the Executive has determined that the foreign nation's laws adequately protect privacy and civil liberties, among other requirements. While the CLOUD Act conditions approval of covered agreements upon a host of restrictions, commentators debate whether these agreements will provide adequate protections for privacy, human rights, and civil liberties.

Law enforcement officials in the United States and abroad increasingly seek access to electronic communications, such as emails and social media posts, stored on servers and in data centers located in foreign countries.1 The architecture of the internet allows technology companies significant flexibility as to the geographic location where they may store collected data.2 As a result, electronic communications that may be evidence of a crime are not necessarily housed in the same country where the crime occurred.3 This disconnect has caused governments around the world, including the United States, to seek data stored outside their territorial jurisdictions in the course of law enforcement investigations.4 It also has led to debate over the extent to which national governments can compel private companies to disclose data stored in foreign nations and the degree to which civil liberties and privacy concerns should inform the proper procedure for sharing such data.5

In the United States, this debate largely has centered on the Stored Communications Act (SCA),6 which is part of the broader Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA).7 Although the SCA generally prohibits certain technology companies from disclosing the contents of electronic communications to third parties,8 it mandates disclosure to the U.S. government pursuant to a warrant based on probable cause that the communications contain evidence of a crime.9 In United States v. Microsoft Corp., the Supreme Court was set to address whether the United States could compel Microsoft to release emails housed in a data center in Ireland through a warrant issued under the SCA.10 But less than one month after oral argument, Congress passed and the President signed into law the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (CLOUD Act) as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018.11 The CLOUD Act amends the SCA and requires service providers subject to the SCA12 to release data in their possession, custody, or control in response to an SCA warrant—regardless of whether the data is located in the United States.13 After the U.S. government obtained a new warrant for the emails held in Ireland under the authority of the CLOUD Act, the Supreme Court deemed Microsoft moot.14

A second facet of the CLOUD Act addresses the reciprocal issue of foreign governments' desire to access data in the United States as part of their investigation and prosecution of crimes.15 Prior to the CLOUD Act, foreign nations seeking data in the United States generally were required to request the assistance of the U.S. government through either procedures established by mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs) or judicial requests known as letters rogatory.16 Requests under either instrument are reviewed by U.S. courts before disclosure to the foreign nation is authorized, but U.S. and foreign officials have criticized these processes as inefficient and unable to accommodate the increasing cross-border data demands in the digital era.17

The CLOUD Act responds to calls for modernization by authorizing the executive branch to conclude a new form of international agreement18 through which select foreign governments can seek data directly from U.S. technology companies without undergoing individualized review by the U.S. government.19 Agreements authorized by the CLOUD Act would remove legal restrictions on certain foreign nations' ability to seek data directly from U.S. providers in cases involving "serious crimes" when not targeting U.S. persons, provided that the United States has determined that the foreign nation's laws adequately protect privacy and civil liberties, among other requirements.20

This report reviews the development of cross-border data sharing laws in criminal matters in the United States.21 It begins with an overview of ECPA and the SCA.22 Next, the report discusses the questions raised in the Microsoft litigation and the impact of the CLOUD Act on those issues.23 Finally, the report examines the new form of international agreements authorized by the CLOUD Act and the commentary on the benefits and drawbacks of the potential new international data sharing agreements.24

Overview of ECPA and the SCA

Enacted in 1986, ECPA is one of the primary federal laws regulating disclosure of electronic communications held by private entities.25 ECPA is structured on three main titles. Title I, commonly referred to as the Wiretap Act, governs the interception of real-time wire, oral, or electronic communications.26 Title II added a new chapter to the United States Code entitled "Stored Wire and Electronic Communications and Transactional Records Access," and generally is referred to as the Stored Communications Act or SCA.27 The SCA applies to many forms of electronic communications and associated data, including emails;28 text messages;29 private messages, wall postings, and other comments made on or via social media sites;30 and private YouTube videos.31 Title III of ECPA regulates the use of a pen register, a device that allows users to capture the routing information associated with communications, such as telephone numbers dialed.32 Each title in ECPA contains restrictions on the circumstances in which the relevant data can be used or disclosed.33

As technology has evolved since ECPA's enactment in 1986, law enforcement has shifted its primary focus from the interception of live communications pursuant to the Wiretap Act to seeking the now-common forms of stored communications governed by the SCA.34 But the SCA does not apply the same provisions to every communication or data that falls under its ambit. Rather, the scope of the SCA may be impacted by whether the law is applied to a provider of "electronic communication services" (ECS) or "remote computing services" (RCS).35 Although some SCA requirements vary depending on the provider,36 the act has two core components that apply to both forms of provider: (1) prohibitions on disclosure of certain data and (2) mandatory disclosure provisions.37

Prohibitions on Disclosure Under the SCA

The first facet of the SCA is a restriction on providers' ability to share customers' electronic communications and their related records and information. Restrictions differ depending on the data at issue.38 For the contents of electronic communications (e.g., the body of an email), the SCA prohibits disclosure to "any person or entity," absent an exception, provided certain technical requirements are met.39 The SCA also prohibits both categories of provider from disclosing a "record or other information pertaining to a subscriber to or customer of such service" to the U.S. government.40 This prohibition, which concerns non-content information or "metadata," does not prohibit disclosure to private entities or foreign governments.41 The SCA enumerates several exceptions to the prohibition on disclosure of both content42 and non-content communications.43

Mandatory Disclosure Under the SCA

The second major component of the SCA is its rules that require providers to disclose customer communications and related records to the U.S. government.44 The SCA establishes a tiered system with differing procedures and standards governing when the U.S. government can demand that providers divulge stored communications.45 As described below, the SCA's standards for mandatory disclosure depend on a number of factors, including, among other things, the type of data sought; whether an ECS or RCS holds the data; the length of time the data has been stored; whether the data is content or non-content; and whether advanced notice has been given to the customer.46 The multitude of relevant factors can make the determination of whether disclosure is mandatory a complex and fact-specific evaluation.47

At the highest level, the SCA requires the U.S. government to obtain a warrant if the government seeks access from an ECS provider to the content of a communication that has been in "electronic storage" for 180 days or less.48 A warrant may be issued only if the U.S. government demonstrates probable cause that the communications sought establish evidence of a crime.49 If the communication has been stored for longer than 180 days, or if it is being "held or maintained" by an RCS "solely for the purpose of providing storage or computer processing services," the government can use a subpoena or a court order under 18 U.S.C. § 2703(d), provided notice is given to the customer.50 To obtain an order under this section—known as a Section 2703(d) order—the applicant must prove "specific and articulable facts, showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the contents of a[n] . . . electronic communication . . . are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation."51

In addition to the content of communications, the SCA permits access to non-content information with a warrant, but the government also may use a subpoena or a Section 2703(d) order to provide the customer notice.52 To access basic subscriber information, including the customer's name, address, phone number, length of service, and means of payment (including bank account numbers), the government may follow the more stringent requirements for obtaining a warrant or a Section 2703(d) order, but it also can use an administrative subpoena, which requires no prior authorization by a judicial officer or notice to the customer.53

United States v. Microsoft Corp. and the CLOUD Act

While the complexities of the SCA coupled with major changes in technology have led some to call for broad reforms to the law,54 one discrete issue—the extraterritorial application of the SCA—became the subject of particular interest as a result of a 2016 federal appellate court decision.55 As noted above, the SCA mandates that service providers disclose the content of electronic communications when the government obtains a warrant based on probable cause.56 In 2013, federal law enforcement officials sought an SCA warrant requiring Microsoft to disclose all emails and other information associated with an account with one of its customers.57 After finding that the United States demonstrated probable cause that the account was being used to further illegal drug trafficking, a United States magistrate judge issued a warrant requiring Microsoft to disclose the contents of an email account and all records or information associated with the account "[t]o the extent that the information . . . is within [Microsoft's] possession, custody, or control."58

Microsoft complied with the portion of the warrant seeking metadata about the user's account (e.g., the name, IP address, and telephone number associated with the account), which was stored in the United States, but it determined that the contents of the user's emails were held in a data center in Dublin, Ireland.59 Microsoft stores its users' emails in one of its many data centers around the world—most often the one closest to where users state they are from when signing up for the email service.60 Although Microsoft did not dispute that it had the ability to access the emails in Ireland using computers inside the United States, it declined to comply with the portion of the warrant seeking data stored overseas on the ground that the SCA's mandatory disclosure provisions did not apply extraterritorially.61

The district court initially overruled Microsoft's objections, and it held the company in civil contempt for failing to produce the emails.62 But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (Second Circuit) reversed those rulings in 2016.63 Relying on the presumption established by the Supreme Court that U.S. laws do not have effect outside U.S. territorial jurisdiction unless the law specifies otherwise,64 the Second Circuit held that the SCA does not authorize the seizure of emails stored exclusively on foreign servers.65 The United States appealed the Second Circuit's decision, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari in 2017 in United States v. Microsoft, Corp.66—a widely followed case that drew attention and amici curie briefs from a range of groups including privacy advocates, law enforcement officials, Members of Congress, 34 U.S. states and territories, and several foreign nations.67

The Legislative Response to Microsoft in the CLOUD Act

While the Microsoft appeal was pending before the Supreme Court, officials from the Department of Justice (DOJ) sought a legislative response to the Second Circuit's ruling.68 In a hearing before the House Committee on the Judiciary in June 2017,69 DOJ representatives argued that the Second Circuit's decision "effectively hamstrung the ability of law enforcement" to obtain data stored by U.S. service providers abroad, creating a "tremendous problem" that caused "substantial harm to public safety."70 Accordingly, DOJ proposed a draft bill that would amend provisions in ECPA, including provisions in the SCA, to state expressly that a service provider must comply with the law's mandatory disclosure requirements when the data is in the provider's possession, custody, or control—regardless of whether the data is located inside the United States.71 As described by DOJ, the proposal was intended to restore the "pre-Microsoft status quo when providers routinely complied" with SCA warrants for data stored abroad.72

In February 2018, identical bills—both titled the CLOUD Act—containing DOJ's proposed extraterritoriality provision were introduced in the House and Senate.73 The CLOUD Act was included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, which was passed by both chambers, and signed into law by the President on March 23, 2018.74 As enacted, the CLOUD Act amends ECPA by, among other things, including the following extraterritoriality provision:

A [provider] shall comply with the obligations of this chapter to preserve, backup, or disclose the contents of a wire or electronic communication and any record or other information pertaining to a customer or subscriber within such provider's possession, custody, or control, regardless of whether such communication, record, or other information is located within or outside of the United States.75

After the CLOUD Act's enactment, the United States obtained a new warrant seeking the emails at issue in its dispute with Microsoft under the authority of the new law.76 Because both the United States and Microsoft agreed that the new warrant replaced the prior warrant, the Supreme Court concluded that the case had become moot, and vacated the lower court's rulings with instructions to dismiss.77

Resolving Conflicts with Foreign Law

In addition to defining the extraterritorial reach of the mandatory disclosure provisions in ECPA, including the SCA, the CLOUD Act contains provisions designed to resolve potential conflicts of law that could arise if the United States seeks data stored abroad when the law of a foreign country prohibits disclosure.78 It does so by authorizing a provider to file a motion to quash or modify a data demand if

- the provider reasonably believes the target of the demand is not a U.S. person79 and does not reside in the United States;

- the provider reasonably believes disclosure would create a material risk of violating a foreign nation's law; and

- the foreign nation whose law may be violated has a data sharing agreement with the United States authorized by the CLOUD Act (discussed in more detail below80).81

A court may grant the providers' motion to modify or quash a government demand for data upon finding that three conditions are met: (1) the required disclosure would violate foreign law; (2) the interests of justice dictate that the demand should be quashed or changed; and (3) the target is not a U.S. person and does not reside in the United States.82 In determining whether the second condition is satisfied, courts must undertake a "comity analysis."83 Comity—or respect for foreign sovereignty84— is a legal doctrine that, among other things, permits courts to excuse violations of U.S. law, or moderate the sanctions imposed for such violations, when the violations are compelled by a foreign nation's law.85 Courts and commentators often have described the comity doctrine as vague and ill-defined,86 but the CLOUD Act specifically enumerates the factors courts should consider when determining whether comity principles support quashing or modifying a data demand.87

Notably, however, the CLOUD Act's comity factors and statutory right to a file a motion to quash or modify apply only to nations with which the United States has a data sharing agreement, as discussed below.88 For nations with no such agreement, the CLOUD Act preserves common law principles of comity.89 Common law comity principles generally dictate that U.S. legal obligations can be avoided as a result of foreign law only when the person or entity in question acted in good faith to avoid the conflict, but there remains a likelihood of severe sanctions in the foreign nation for failure to comply with foreign law.90 Ultimately, the comity analysis under either the CLOUD Act or common law principles is likely to be a highly fact-specific evaluation that depends on the specific circumstances of a demand for data stored overseas.

International Data Sharing After the CLOUD Act

In addition to expressly expanding the ability of the U.S. government to require service providers to release data stored outside the United States, the CLOUD Act addresses a reciprocal issue: limitations on foreign governments' ability to obtain data in the United States.91 As internet-based communications have become commonplace, evidence of criminal conduct frequently is derived from data stored on servers located outside the territorial jurisdiction of the nation where the crime was committed.92 Because technology companies headquartered in the United States hold a majority of the world's electronic communications on their servers, foreign governments frequently seek data held by U.S. companies.93 At the same time, ECPA prohibits service providers from disclosing the content of electronic communications directly to foreign governments absent a statutory exception or a warrant from a federal court.94

With ECPA acting as a "blocking statute" that prevents foreign governments from directly acquiring certain third-party data stored by private entities in the United States, foreign nations have sought the U.S. government's assistance in obtaining warrants that authorize disclosure.95 Prior to the CLOUD Act, there were two common international legal processes for obtaining a warrant in the United States: letters rogatory requests and MLATs.96

|

Three Forms of Cross-Border Data Sharing Letters Rogatory. Discretionary requests made between the courts of one country to the courts of another country that are available to governments and private litigants, which are generally seen as the least efficient and reliable method of obtaining evidence abroad.97 Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs). Treaties providing streamlined processes for cross-border evidence sharing between governments in criminal cases, which are reviewed by DOJ and a federal court for compliance with U.S. law.98 CLOUD Act Agreements. Executive agreements removing legal restrictions on certain foreign nations' ability to seek data directly from U.S. providers in cases involving "serious crimes" when not targeting U.S. persons, provided that the United States has determined that the foreign nation's laws adequately protect privacy and civil liberties.99 |

Letters Rogatory

Letters rogatory are requests made by a court in one nation to the court of another nation seeking assistance in obtaining evidence located abroad.100 Historically, letters rogatory were the principle mechanism for sharing evidence between nations.101 Whereas MLATs and agreements authorized under the CLOUD Act generally are limited to government-to-government requests in criminal cases (with some exceptions in early MLATs),102 criminal defendants and private litigants in civil cases may request that U.S. courts issue letters rogatory.103 Governments may also use letters rogatory to seek judicial assistance in obtaining evidence abroad when the United States does not have either an MLAT or a CLOUD Act agreement with a foreign nation.104

Letters rogatory are discretionary requests premised on principles of comity rather than an obligation under international law.105 There is no legal obligation or guarantee that the country receiving the request will respond,106 and the evidence sharing process has been described as time-consuming and unpredictable.107 Consequently, letters rogatory are often seen as the least preferable method of obtaining evidence abroad.108

Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs)

As investigations into complex, coordinated international crimes like money laundering and drug trafficking became more common in the 1970s, the United States and other nations began to enter into MLATs, which established standardized procedures for sharing of certain evidence across national boundaries in criminal matters.109 MLATs are treaties—most often bilateral treaties—in which nations agree to provide certain assistance to foreign governments in the investigation and prosecution of crimes.110 Whereas letters rogatory are discretionary requests, MLATs create treaty-based obligations governed by international law.111

While the requirements in each MLAT may differ depending on the specific terms of the treaty, MLATs generally obligate nations to summon witnesses, compel the production of documents and other evidence, issue warrants, and serve process in response to requests from the foreign government.112 MLATs typically also identify grounds for refusing requests.113 The United States has MLATs with more than 60 nations,114 but this accounts for less than half the nations in the world.115

Each party to an MLAT designates a central authority through which direct communications can be made.116 The central authority for the United States is the Office of International Affairs (OIA) in the Criminal Division of DOJ.117 When a request for legal assistance is submitted to the United States,118 OIA receives and conducts an initial review to ensure that the request contains all necessary information and comports with required formats.119 OIA then transmits the request to the U.S. Attorney in the jurisdiction where the witness or evidence is located.120 The U.S. Attorney brings the request before a federal district court by filing a request for a court order or warrant authorizing the United States to carry out the action sought by the foreign nation.121 Before authorizing the action, courts review the request to ensure that it complies with the underlying treaty and U.S. law and constitutional requirements.122 After a warrant or court order has been issued and the provider transfers the data to the U.S. government, OIA and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) review the material in an effort to minimize production of information that is not responsive to the request.123

According to the 2013 President's Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies, MLAT requests submitted to the United States take an average of approximately 10 months to complete.124 When the United States seeks data from foreign nations, some requests take "considerably longer,"125 especially when submitted to countries that are uncooperative or have less sophisticated legal systems.126 According to one U.S. official, the United States never receives a response to some requests.127

Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act

Although the MLAT process generally is seen as more predictable and efficient than letters rogatory,128 MLATs became the subject of criticism in recent years due to, among other things, the typical length of response time under such agreements and the fact that the United States does not have any MLAT with more than half the nations in the world.129 At the same time, the number of requests for assistance in obtaining data and other evidence in the United States has increased markedly. In its FY2017 budget request, DOJ stated that the number of requests for judicial assistance from foreign countries increased nearly 85%, and the number for requests for "computer records" increased over 1000%.130

As foreign governments' need for data located overseas has expanded, some nations have sought data directly from U.S. providers and passed legislation authorizing their governments to compel disclosure.131 These developments have placed U.S. technology companies at the intersection of potentially conflicting legal obligations: service providers may be both subject to foreign court orders compelling the release of data and prohibited by U.S. law from disclosing that data.132 The potentially conflicting obligations coupled with criticisms of the MLAT and letters rogatory processes led to proposals for changes in the international data sharing regime that ultimately culminated in the CLOUD Act.133

The CLOUD Act creates a third paradigm of international data sharing arrangements: the possibility of international agreements that remove legal restrictions on U.S. technology companies' ability to disclose data directly to certain foreign nations in response to "orders" issued by foreign nations.134 Whereas MLATs are "treaties" within the meaning of U.S. constitutional law—meaning they are binding international agreements concluded by the Executive after receiving the advice and consent of the Senate as provided in the Treaty Clause135—the CLOUD Act authorizes the United States to enter "executive agreements" with qualifying foreign nations.136 Executive agreements are binding international agreements entered into by the Executive based on a source of authority other than the Treaty Clause.137 The Executive's authority often is derived from legislation, as is the case in the CLOUD Act.138

The executive agreements authorized under the CLOUD Act would allow service providers to disclose the contents of electronic communications—both stored communications and real-time communications intercepted by wiretap—directly to requesting foreign governments with whom the United States has an authorized data sharing agreement.139 The act does so by removing ECPA's prohibitions on disclosure to such foreign governments.140 When a foreign nation with a CLOUD Act agreement issues an "order" seeking data from a provider in the United States, the provider can deliver the requested data without civil or criminal penalty under ECPA.141 By contrast, in the MLAT and letters rogatory processes, cross-border data requests initially are submitted to government entities rather than to the private party in possession of the data.142

Although the CLOUD Act authorizes executive agreements that would remove ECPA's prohibitions on disclosure, neither the act nor the agreements it authorizes create a legal obligation for service providers to comply with foreign governments' data demands.143 Rather, a foreign government's authority to issue an order seeking data must derive solely from its domestic law.144 Additionally, state or federal laws other than ECPA still may prohibit disclosure of particular classes of information.145

Requirements for CLOUD Act Agreements

The CLOUD Act contains a number of restrictions on the type of foreign governments with whom the United States can enter agreements and the nature of demands for data that qualifying foreign governments can issue to U.S. providers.146 Before an agreement concluded under the CLOUD Act can enter into force, the Attorney General, with the concurrence of the Secretary of State, must make four written certifications that are provided to Congress and published in the Federal Register:

- 1. the foreign nation's domestic law "affords robust substantive and procedural protections for privacy and civil liberties" in its data-collection activities, as determined based on at least seven statutory factors;147

- 2. the foreign government has adopted "appropriate" procedures to minimize the acquisition, retention, and dissemination of information concerning U.S. persons;

- 3. the executive agreement will not create an obligation that providers be capable of decrypting data, nor will it create a limitation that prevents providers from decryption;148 and

- 4. the executive agreement will require that any order issued under its terms will be subject to an additional set of procedural and substantive requirements, as discussed below.149

The CLOUD Act expressly states that these certifications are not subject to judicial or administrative review.150 But the act gives Congress the power to prevent a proposed executive agreement from entering into force through expedited congressional review provisions after the certifications are provided.151 Certifications must be renewed every five years, and recertifications trigger Congress's power to block renewal through expedited review processes.152 Additionally, if requested by the Committees on the Judiciary or Foreign Affairs in the House or the Committees on the Judiciary or Foreign Relations in the Senate, the executive branch must furnish to the requesting committee a summary of the factors it considered when determining that a foreign government satisfies the CLOUD Act's requirements.153

Limitations on Orders Issued Under CLOUD Act Agreements

The fourth certification required by the CLOUD Act mandates that any data sharing agreement concluded under the act contain a set of requirements related to foreign governments' orders issued to service providers. These include, among things,154 requirements that all orders

- identify a specific person, account, or other identifier that is the object of the order;155

- be premised on a "reasonable justification based on articulable and credible facts, particularity, and severity regarding the conduct under investigation";156

- not intentionally target a U.S. person (or person located in the U.S.) or target a non-U.S. person with the intention of obtaining information about a U.S. person;

- be issued for the purpose of obtaining information relating to the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution or a "serious "crime"—a term that the CLOUD Act states includes terrorism, but otherwise does not define;157

- comply with the domestic law of the issuing country;

- not be used to infringe freedom of speech; and

- satisfy additional requirements for real-time communications captured by wiretap.158

When a foreign government receives the requested data from the provider, it must promptly review the material and store any unviewed communications on a "secure system accessible only to those trained in applicable procedures . . . ."159 The "applicable procedures" must, to the maximum extent possible, comply with the minimization procedures in Section 101 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).160 Foreign governments may not issue an order at the request of the United States or any third-party government, and they may not disclose the content of communications of a U.S. person to the U.S. government except in cases involving significant harm or threat of harm to the United States or U.S. persons.161

Mandatory Rights Granted to the United States

The CLOUD Act requires that data sharing agreements grant certain powers to the U.S. government. Specifically, the foreign government must grant reciprocal rights of data access to the United States and allow the U.S. government to conduct periodic reviews of the foreign nation's compliance with the terms of the executive agreement.162 CLOUD Act agreements also must reserve the United States' right to "render the agreement inapplicable" for any order for which the United States concludes the agreement "may not properly be invoked."163

Judicial or Governmental Review of Orders Under CLOUD Act Agreements

The process for judicial or other government oversight of foreign nations' requests for data under the CLOUD Act differs from earlier international data sharing regimes. In both the MLAT and letters rogatory processes, a federal court reviews and approves a foreign government's request for information before issuing a warrant or court order.164 Such requests generally must satisfy U.S. legal standards and constitutional requirements, such as the Fourth Amendment probable cause standard.165 Several federal appellate courts have stated that an otherwise valid MLAT or letters rogatory request may be rejected if compliance would result in a violation of the Constitution.166 For MLAT requests, agencies in the executive branch conduct additional reviews for compliance with U.S. law before and after receiving judicial approval to execute a cross-border data request.167

Under CLOUD Act agreements, by contrast, foreign governments can submit orders directly on service providers.168 While those orders are "subject to review or oversight by a court, judge, magistrate, or other independent authority" in the foreign nation, the CLOUD Act does not require review or approval by a U.S. court or federal agency.169 And unlike MLATs and letters rogatory, the CLOUD Act contemplates that the judicial or other independent review in the foreign country could occur after a foreign government issued an order to a service provider.170 The ultimate result is that foreign nations' orders issued under the CLOUD Act are not required to undergo individualized review by any branch of the U.S. government, and U.S. courts are not required to analyze whether the foreign government's request complies with U.S. constitutional standards. This change appears to be intended to accelerate the data sharing process, especially in cases involving emergency or other time-sensitive requests.171 Rather than review each request individually, the United States' opportunity to scrutinize a foreign country's data demands primarily will occur during the periodic review of a foreign nation's compliance with its data sharing agreements and when evaluating whether a foreign nation's laws satisfy the CLOUD Act's eligibility requirements.172

What Nations Are Eligible for CLOUD Act Agreements?

The CLOUD Act does not specify by name what countries meet its requirements, and the Attorney General has not provided the requisite certifications for a proposed agreement as of the date of this report. Consequently, it is not clear which, if any, nations may be eligible for CLOUD Act agreements. However, in 2016, DOJ informed Congress that the United States sought legislation that would implement a potential bilateral data sharing agreement with the United Kingdom.173 While the draft bilateral agreement has not been made public, DOJ proposed legislation that the department stated was necessary to implement the potential agreement.174 The structure and many provisions of the CLOUD Act appear to have been derived—and in some cases taken verbatim—from DOJ's proposed legislation.175 Some commentators believe that the U.S.-U.K. agreement will be the first agreement to be certified by the executive branch and submitted to Congress for review under the CLOUD Act's expedited congressional review procedures, as discussed below.176

Congressional Review of CLOUD Act Agreements

The CLOUD Act provides for a mandatory 180-day period of congressional review before a proposed data sharing agreement can enter into force.177 The act also defines a number of procedures authorizing congressional consideration of a joint resolution of disapproval of an executive agreement on an expedited process. The procedures include among other things, automatic discharge of the congressional committees to whom the joint resolution has been referred within 120 days;178 waiver of certain points of order; limitations on and structuring of debate; and expedited treatment of a joint resolution received from the other chamber of Congress.179

If Congress enacts a joint resolution of disapproval during the 180-day review window, the CLOUD Act states that the proposed agreement may not enter into force.180 Such a joint resolution of disapproval would require passage by both chambers of Congress and the President's signature or a veto override.181 Because the CLOUD Act provides that proposed data sharing agreements will be submitted to Congress after already receiving the approval of two Cabinet-level executive officials—the Attorney General and Secretary of State—some commentators contend that a President would be unlikely to sign a joint resolution of disapproval, making a veto-proof majority necessary to block a proposed CLOUD Act agreement.182

Commentary on the CLOUD Act

The CLOUD Act has garnered both praise and criticism from observers.183 Some argue that the act provides a practical remedy for problems related to the globalization of evidence and the increased demand for data stored overseas in criminal cases.184 Supporters assert that the need for data stored abroad, which often is held by U.S. internet companies, has overburdened the legal architecture established in the MLAT and letters rogatory systems, rendering those systems "outdated and inefficient."185 Supporters also argue that the CLOUD Act provides adequate protection for privacy, civil liberties, and human rights.186 They contend that, absent the change in law, frustrated foreign governments that are unable to obtain data held by U.S. companies will exert extraterritorial application of their own laws or enact data localization laws187 that some believe impede the effective functioning of an open internet.188 Several major U.S. technology companies—including Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Oath—support the legislation, calling it an effective legislative solution that reduces conflicts of laws.189

Critics of the CLOUD Act argue that it poses a threat to civil liberties and human rights by lowering the standards previously necessary to obtain evidence in cross-border criminal investigations and prosecutions.190 They contend that the CLOUD Act's standard for individualized suspicion—"reasonable justification based on articulable and credible facts, particularity, legality, and severity regarding the conduct under investigation"—is vague and may not rise to the level of probable cause necessary to obtain a judicial warrant under U.S. law.191 Some argue that the executive branch's decision to certify a country as satisfying the CLOUD Act's standards should be subject to judicial or other review.192 Others contend that the concept that foreign nations' data requests do not need individualized review if the nations' domestic laws meet the act's eligibility criteria is flawed because foreign governments' real-world operations may not comport with their domestic laws and may change over time.193 Several critics of the CLOUD Act argue that it should require a foreign court or independent authority to approve a foreign government's order before the order is issued on a U.S. provider.194 Others contend, among other things, that the law should increase the requirements for foreign governments to obtain access to real-time communications to the same standards that apply to the United States' interception of live communications in the Wiretap Act.195

How Will CLOUD Act Agreements Interact with Existing Data Sharing Processes?

Executive agreements authorized by the CLOUD Act would supplement, not replace, existing avenues of international data sharing.196 Accordingly, requests for assistance would still be available through MLATs (when in effect) and letters rogatory.

When analyzed in light of existing data sharing processes, the CLOUD Act has the potential to result in a three-tiered system for cross-border data sharing in criminal matters. Those nations that are approved for CLOUD Act agreements could request data directly from U.S. service providers in cases involving "serious crimes"—provided they do not target U.S. persons or persons located in the United States and meet the CLOUD Act's other requirements.197 For nations that have an MLAT but no CLOUD Act agreement, or for data requests that fall outside the scope of the CLOUD Act, foreign governments can use the MLAT process.198 Finally, private litigants and nations that do not have a CLOUD Act agreement or an MLAT may request that their courts issue letters rogatory to the courts of the United States.199

|

|

Source: Supra §§ "Letters Rogatory"; "Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs)"; and "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act". |

Conclusion

While the CLOUD Act is likely to more clearly define the scope of U.S. officials' right to seek certain data stored overseas in the custody of U.S. providers, its broader impact on the international data sharing regime is less certain. As the internet continues to expand and become more globalized, law enforcement officials worldwide can be expected to continue to seek access to data stored on servers outside their territorial jurisdictions.200 Although the major technology companies responsible for maintaining a large share of the world's data are located in the United States,201 the United States accounts for less than 10% of the estimated 3 billion internet users worldwide.202 These demographics potentially could lead many nations to pursue CLOUD Act agreements, which would provide faster access to data held by U.S. providers. Whether the United States ultimately enters such agreements will depend on the willingness of the executive branch to certify foreign nations' eligibility and Congress's desire to block a proposed agreement through a joint resolution of disapproval enacted into law.

The impact of the CLOUD Act on privacy, human rights, and civil liberties interests similarly is difficult to predict.203 The act has the potential to create a three-tiered system of international data sharing, with the United States' most trusted foreign partners able to obtain data directly from U.S. companies without individualized review by the U.S. government.204 Because this system of direct access differs from existing international data sharing regimes, the manner in which data requests are administered, the type of data that is collected, and the degree of potential for abuse of the system, if any, may become more apparent over time.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, e.g., Andrew Keane Woods, Against Data Exceptionalism, 68 Stan. L. Rev. 729, 742-45 (2016) (analyzing trends of increased government demands for data located outside a nation's territorial jurisdiction); Data Stored Abroad: Ensuring Lawful Access and Privacy Protection in the Digital Era: Hearing Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 115th Cong. 1 (2017) [hereinafter Data Stored Abroad Hearing] (statement of Richard W. Downing, Acting Deputy Assistant Att'y Gen., U.S. Dep't of Justice), https://judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Downing-Testimony.pdf [hereinafter Downing Statement] (outlining challenges to U.S. and foreign government efforts to obtain data overseas). |

| 2. |

See, e.g., Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 2490-91 (2014) ("Cloud computing is the capacity of Internet-connected devices to display data stored on remove servers rather than on the device itself.");Woods, supra note 1, at 739 ("[O]ne of the greatest societal and technological shifts In recent years has been the move from storing data on a local machine—such as a cell phone or computer—to storing that data remotely on faraway servers, which can be accessed by a network such as the Internet."). |

| 3. |

See, e.g., Data Stored Abroad Hearing, supra note 1 (statement of Paddy McGuinness, Deputy Nat'l Sec. Advisor, U.K.), https://judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/McGuinness-Testimony.pdf [hereinafter McGuinness Statement] (discussing the need for U.K. law enforcement access to data stored in the United States); Hearing on International Conflicts of Law Concerning Cross Border Data Flow and Law Enforcement Requests Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 114th Cong. 22, 57-59 (2016) [hereinafter International Conflicts of Law Hearing] (statement of Brad Smith, President and Chief Legal Officer, Microsoft Corp.) [hereinafter Smith Statement] (discussing French requests for data stored by Microsoft following a 2015 terrorist attack in Paris). |

| 4. |

See supra notes 1-3. See also infra § "United States v. Microsoft Corp. and the CLOUD Act" (discussing the United States efforts to obtain data in Ireland); International Conflicts of Law Hearing, supra note 3, at 17-18 (statement of David Bitkower, Principal Assistant Deputy Att'y Gen., U.S. Dep't of Justice) [hereinafter Bitkower Statement] (listing examples of evidence gathered from American technology companies that was critical to solving crimes overseas); Peter Swire et al., A Mutual Legal Assistance Case Study: The United States and France, 34 Wis. Int'l L.J. 323, 327 (2016) (discussing "how the globalization of data is affecting even routine criminal investigations"). |

| 5. |

Compare, e.g., Jennifer Daskal, The Un-Territoriality of Data, 125 Yale L.J. 326, 329 (2015) (contending that the unique nature of data and the "physical disconnect between the location of data and the location of its user" undermines traditional notions of territorial sovereignty), with Woods, supra note 1, at 756-63 (arguing that data is compatible with existing conceptions of sovereignty and jurisdiction). See also infra § "Commentary on the CLOUD Act" (discussing commentary regarding the extent to which cross-border data sharing regimes should provide safeguards for privacy, human rights, and civil liberties). |

| 6. |

See 18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-2712. |

| 7. |

See P.L. 99-508, 100 Stat. 1848 (1986). |

| 8. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a). |

| 9. |

Id. § 2703(a). |

| 10. |

See No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369, slip op. at 2 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 11. |

See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, P.L. 115-141, div. V [hereinafter CLOUD Act]. |

| 12. |

As discussed in more detail below, the SCA applies to a provider of an "electronic communications service," defined in 18 U.S.C. § 2510(15), and a "remote computing service," defined in 18 U.S.C. § 2711(2). See infra "Overview of ECPA and the SCA." Unless otherwise indicated, the terms "service providers" or "providers" in this report reference both entities covered by the SCA. |

| 13. |

CLOUD Act § 103 (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2713). |

| 14. |

See No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369, slip op. at 2 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam) (vacating and remanding with instructions to dismiss as moot). |

| 15. |

See CLOUD Act § 102(3) (discussing foreign governments' need to "access electronic data held by communications-service providers in the United States" in the congressional findings). See also infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 16. |

See T. Markus Funk, Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties and Letters Rogatory: A Guide for Judges 1 (Fed. J. Center 2014), https://www.fjc.gov/sites/default/files/2017/MLAT-LR-Guide-Funk-FJC-2014.pdf; Woods, supra note 1, at 748-49. While MLATs and letters rogatory have been the standard legal avenues for seeking cross-border data, some information can be provided through informal channels, such as cooperative exchange between investigators. See Funk, supra, at 23. |

| 17. |

See, e.g., President's Review Grp. on Intelligence & Commc'ns Techs., Liberty and Security in a Changing World: Report and Recommendations 227 (2013) [hereinafter President's Review Group] ("The MLAT process . . . is too slow and cumbersome."); Downing Statement, supra note 1, at 7 ("[T]he [mutual legal assistance] process can lack the requisite efficiency for time-sensitive investigations and other emergencies, making it an impractical alternative to SCA warrants in many cases."); McGuinness Statement, supra note 3 ("It is widely acknowledged that MLAT processes are too slow for rapidly developing counter terrorism and serious crime investigations."). |

| 18. |

As used in this report, the term "international agreement" is intended to be a blanket term that includes all agreements between the United States and foreign nations that are intended to be binding under international law. Accord Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law: Treaties, Tentative Draft No. 2, § 102 cmt. a (2017). |

| 19. |

See infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 20. |

See id. |

| 21. |

Because this report focuses on data sharing in the context of criminal investigations, it does not address other, unrelated forms of information sharing, such as information sharing within an industry or with the government following a cyberattack, see CRS In Focus IF10163, Cybersecurity and Information Sharing, by [author name scrubbed], or information shared among private companies for commercial purposes, see Facebook, Social Media Privacy, and the Use and Abuse of Data, Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Commerce, Science, and Transportation 115th Cong. (Apr. 10, 2018). |

| 22. |

See infra § "Overview of ECPA and the SCA." Although constitutional provisions such as the Fourth Amendment are relevant to government access to personal data as part of a criminal investigation, see United States v. Warshak, 631 F.3d 266 (6th Cir. 2010) (holding that the government must obtain a warrant to access certain stored emails), the focus of this report is on statutory protections. |

| 23. |

See infra § "United States v. Microsoft Corp. and the CLOUD Act". |

| 24. |

See infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 25. |

See P.L. 99-508, 100 Stat. 1848 (1986). |

| 26. |

See id. tit. I, 100 Stat. at 1848-59 (codified in 18 U.S.C. §§ 2510-2521). |

| 27. |

Id. at 1860. |

| 28. |

See Theofel v. Farey-Jones, 359 F.3d 1066, 1077 (9th Cir. 2004), cert denied 543 U.S. 813 (2004). |

| 29. |

See Quon v. Arch Wireless Operating Co., Inc., 529 F.3d 892, 901 (9th Cir. 2008), rev'd on Fourth Amendment grounds sub nom. Quon v. City of Ontario, 560 U.S. 746 (2010). |

| 30. |

See Crispin v. Christian Audigier, 717 F. Supp. 2d 965, 980, 989 (C.D. Cal. 2010). |

| 31. |

See Viacom Intern. Inc. v. YouTube Inc., 253 F.R.D. 256, 264 (S.D.N.Y. 2008). |

| 32. |

P.L. 99-508, tit. III, 100 Stat. 1848, 1868-73 (codified in 18 U.S.C. §§ 3121-3127). |

| 33. |

See 18 U.S.C. §§ 2511(1), 2702; 3121. For additional analysis of ECPA and its provisions, see CRS Report R41733, Privacy: An Overview of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report R41734, Privacy: An Abridged Overview of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 34. |

See Orin Kerr, The Next Generation Communications Privacy Act, 162 U. Pa. L. Rev. 373, 394 (2014). |

| 35. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(1)-(2). |

| 36. |

A provider of ECS allows its customers "to send or receive wire or electronic communications." Id. § 2510(15). A provider of RCS provides "computer storage or processing services by means of an electronic communication system." Id. § 2711(2). |

| 37. |

See infra §§ "Prohibitions on Disclosure Under the SCA"; "Mandatory Disclosure Under the SCA." |

| 38. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2702. |

| 39. |

Providers of ECS may not disclose the contents of communication "while in electronic storage." Id. § 2702(a)(1). Providers of RCS may not disclose the contents of a communication that is "carried or maintained" by the service, provided two additional conditions are satisfied. Id. § 2702(a)(2). First, the communication must be maintained "on behalf of, and received by means of electronic transmission from (or created by means of computer processing of communications received by means of electronic transmission from), a subscriber or customer of such service." Id. § 2702(a)(2)(A). Second, the communication must be maintained "solely for the purpose of providing storage or computer processing services to such subscriber or customer, if the provider is not authorized to access the contents of any such communications for purposes of providing any services other than storage or computer processing." Id. § 2702(a)(2)(B). |

| 40. |

Id. § 2702(a)(3) ("a provider of remote computing service or electronic communication service to the public shall not knowingly divulge a record or other information pertaining to a subscriber to or customer of such service (not including the contents of communications covered by paragraph (1) or (2)) to any governmental entity."). The SCA defines "government entity" as "a department or agency of the United States or any State or political subdivision thereof." Id. § 2711(4). |

| 41. |

Id. § 2702(c)(6). Other federal or state laws may prohibit disclosure of particular classes of non-content information to foreign governments or private entities even if the SCA does not. See, e.g., id. § 2710 (restricting disclosure of "prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials"); 20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b) (restricting the disclosure of "education records" by education agencies or institutions that receive federal funds). |

| 42. |

Among other exceptions enumerated in 18 U.S.C. § 2702(b), providers may divulge the content of communications: to an addressee or intended recipient; as may be necessary incident to the rendition of the service or the protection of the rights of property of the provider of that service; or to the U.S. government, if the provider, in good faith, believes that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requires disclosure without delay. |

| 43. |

Exceptions to the prohibition on disclosure of non-content data are listed in 18 U.S.C. § 2702(c). These exceptions include, among things, disclosure (1) with the lawful consent of the customer or subscriber; (2) as may be necessarily incident to the rendition of the service or to the protection of the rights or property of the provider of that service; (3) to the U.S. government, if the provider, in good faith, believes that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requires disclosure without delay; (4) to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; and (5) to any non-U.S.-government person or entity. |

| 44. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2703. |

| 45. | |

| 46. |

See id. |

| 47. |

For example, whether disclosure of email content is required may depend on, among other factors, the technical architecture of the email system and whether the intended recipient opened the email. See United States v. Weaver, 636 F. Supp. 2d 769, 771 (C.D. Ill. 2009) (discussing how the SCA's mandatory disclosure requirements differ when applied to a "web-based email system" as compared to other email systems); Orin K. Kerr, A User's Guide to the Stored Communications Act, and a Legislator's Guide to Amending It, 72 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1208, 1220-24 (2004) (providing background on ECPA). (discussing the application of the SCA's mandatory disclosure provisions to various forms of email in transit and in storage). |

| 48. |

18 U.S.C. § 2703(a). "Electronic storage" is defined as "(A) any temporary, intermediate storage of a wire or electronic communication incidental to the electronic transmission thereof; and (B) any storage of such communication by an electronic communication service for purposes of backup protection of such communication." 18 U.S.C. § 2510(17). The case law generally holds that a user-opened email stored solely on the email provider's server is not in "electronic storage." See Theofel v. Farey-Jones, 359 F.3d 1066, 1077 (9th Cir. 2004) ("A remote computing service might be the only place a user stores his messages; in that case, the messages are not stored for backup purposes."); Fraser v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 135 F. Supp. 2d 623, 636 (E.D. Penn. 2001) ("[M]essages that are in post-transmission storage, after transmission is complete, are not covered by part (B) of the definition of 'electronic storage'"). |

| 49. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2703(a) (requiring that any warrant issued under the SCA be "issued using the procedures described in the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (or, in the case of a State court, issued using State warrant procedures) by a court of competent jurisdiction"); Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(d)(1) ("[A] magistrate judge—or if authorized . . . a judge of a state court of record—must issue the warrant if there is probable cause to search for and seize a person or property or to install and use a tracking device."). |

| 50. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2703(a); § 2703(b)(1)(B). |

| 51. |

Id. § 2703(d). |

| 52. |

See id. § 2703(c). |

| 53. |

See id. |

| 54. |

See, e.g., Kerr, supra note 34, at 376-78; Caroline Lynch, ECPA Reform 2.0. Previewing the Debate in the 115th Congress, Lawfare (Jan. 30, 2017), https://www.lawfareblog.com/ecpa-reform-20-previewing-debate-115th-congress. |

| 55. |

See Matter of Warrant to Search a Certain E-Mail Account Controlled and Maintained by Microsoft Corporation, 829 F.3d 197, 222 (2d Cir. 2016) [hereinafter Matter of Warrant], vacated and remanded with instructions to dismiss, United States v. Microsoft Corp., No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 56. |

See supra § "Mandatory Disclosure Under the SCA." |

| 57. |

See United States v. Microsoft Corp., No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369, slip. op. at 1 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 58. |

Id. |

| 59. |

Matter of Warrant, 829 F.3d at 204. |

| 60. |

See Matter of Warrant, 829 F.3d 197, 204-06 (2d Cir. 2016), vacated and remanded with instructions to dismiss, United States v. Microsoft Corp., No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 61. |

See id. at 209. |

| 62. |

Id. at 205. |

| 63. |

See id. at 222. |

| 64. |

See RJR Nabisco, Inc. v. European Cmty., 136 S.Ct. 2090, 2101 (2016); Morrison v. Nat'l Australia Bank Ltd., 561 U.S. 247, 266 (2010). |

| 65. |

See Matter of Warrant, 829 F.3d at 222. |

| 66. |

United States v. Microsoft Corp., 138 S.Ct. 356 (2017) (mem. op.), vacated and remanded with instructions to dismiss, No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 67. |

Among the more than 30 amici curie briefs were briefs filed by privacy groups; former law enforcement, national security and intelligence officials; 34 U.S. states and territories; the United Kingdom; Ireland; the European Commission (on behalf of the European Union); the New Zealand Privacy Commissioner; two U.S. Senators; and three Members of the U.S. House of Representatives. For a collection of amici briefs filed in Microsoft, see United States v. Microsoft Corp., SCOTUSblog (last visited Apr. 19, 2018), http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/united-states-v-microsoft-corp/. |

| 68. |

See Legislation to Permit Secure and Privacy-Protected Access to Cross-border Electronic Data for Law Enforcement to Combat Serious Crime and Terrorism [hereinafter 2017 DOJ Proposed Legislation], in Downing Statement, supra note 1, at app. A. The 2017 DOJ proposal also contained language derived from draft legislation prepared by DOJ in 2016 that addresses authorization for data sharing executive agreements, discussed infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." See infra note 174 (discussing the DOJ's legislative proposal in 2016). |

| 69. |

See Data Stored Abroad Hearing, supra note 1. |

| 70. |

Downing Statement, supra note 1, at 1. See also Letter from Samuel R. Ramer, Acting Assistant Att'y Gen., U.S. Dep't of Justice, to the Honorable Paul Ryan, Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives (May 24, 2017), https://judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Downing-Testimony.pdf [hereinafter Ramer Letter] ("Congress can address the ongoing and substantial damage to public safety caused by the Microsoft decision . . . ."). |

| 71. |

2017 DOJ Proposed Legislation, supra note 68, § 3(a). |

| 72. |

Ramer Letter, supra note 70, at 1. |

| 73. |

See H.R. 4943, 115th Cong. (2018); S. 2383, 115th Cong. (2018). The CLOUD Act, as introduced and later enacted into law, contains minor variations on DOJ's proposed extraterritorial provision by removing the reference to a "provider of . . . wire communications"—a term not used in ECPA. Compare 2017 DOJ Proposed Legislation, supra note 68, § 3(a), with CLOUD Act § 103(a)(1) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2713). The CLOUD Act also added the comity analysis, discussed infra § "Resolving Conflicts with Foreign Law," which was not in the 2017 DOJ proposal, and made certain changes to DOJ's proposed authorization for international data sharing agreements, discussed infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 74. |

See supra note 11. |

| 75. |

CLOUD Act § 103(a)(1) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2713). |

| 76. |

United States v. Microsoft Corp., No. 17-2, 548 U.S. __, 2018 WL 1800369, slip op. at 2 (U.S. Apr. 17, 2018) (per curiam). |

| 77. |

Id. |

| 78. |

CLOUD Act § 103(b) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2703(h)). |

| 79. |

The CLOUD Act defines "United States person" as a citizen or national of the United States, an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, an unincorporated business association in which a substantial number of members are citizens or lawfully admitted permanent residents, or a corporation that is incorporated in the United States. See CLOUD Act § 105(a) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2523(a)(2)). |

| 80. |

See infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 81. |

CLOUD Act § 103(b) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2703(h)). The foreign nation must also provide reciprocal rights allowing providers to quash or modify data demands in the foreign nation. See id. |

| 82. |

See id. |

| 83. |

See id. |

| 84. |

The classic definition of comity in U.S. law is derived from Hilton v. Guyot, an 1895 Supreme Court decision: "Comity," in the legal sense, is neither a matter of absolute obligation, on the one hand, nor of mere courtesy and good will, upon the other. But it is the recognition which one nation allows within its territory to the legislative, executive or judicial acts of another nation, having due regard both to international duty and convenience, and to the rights of its own citizens, or of other persons who are under the protection of its laws. 159 U.S. 113, 163–64 (1895). For additional background on the comity doctrine, see William S. Dodge, International Comity in American Law, 115 Colum. L. Rev. 2071 (2015). |

| 85. |

See Restatement (Fourth) of Foreign Relations Law: Jurisdiction, Tentative Draft No. 2, § 222 (2016) [Hereinafter Fourth Restatement: Jurisdiction TD 2] ("To the extent permitted by statute, regulation, or procedural rule, U.S. courts have discretion to excuse violations of U.S. law . . . on the ground that the violations are compelled by another state's law, if: (a) the person in question appears likely to suffer severe sanctions for failing to comply with foreign law; and (b) the person in question had acted in good faith to avoid the conflict."); id. at § 222 reporters' n.10 (stating that the defense of foreign state compulsion "reflects the practice of states in the interests of comity."). See also Société Internationale v. Rogers, 357 U.S. 197, 211 (1958) (ordering lower court to devise less severe sanctions for failure to produce banking records when "the very fact of compliance by disclosure . . . will itself constitute the initial violation of Swiss laws"); Gucci Am., Inc. v. Weixing Li, 768 F.3d 138 (2d Cir. 2014) (directing the district court to "undertake a comity analysis" due to the "apparent conflict between the obligations set forth in [an American court's injunction] and applicable Chinese banking law"); In re Sealed Case, 825 F.2d 494, 498 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (reversing dismissal of a contempt order and noting that the "government concedes that it would be impossible for the bank to comply with the contempt order without violating the laws of country Y on country Y's soil), cert denied sub nom, Roe v. United States, 484 U.S. 963 (1987). |

| 86. |

See, e.g., JP Morgan Chase Bank v. Altos Hornos de Mexico, S.A. de C.V., 412 F.3d 418, 423 (2d Cir. 2005) ("International comity . . . has never been well-defined."); Turner Entm't Co. v. Degeto Film GmbH, 25 F.3d 1512, 1518 (11th Cir. 1994) (describing "respect for the acts of our fellow sovereign nations" as a "rather vague concept referred to in American jurisprudence as international comity"); Anne-Marie Slaughter, Court to Court, 92 Am. J. Int'l L. 708, 708 (1998) ("Comity . . . is a concept with almost as many meanings as sovereignty."); Joel R. Paul, Comity in International Law, 32 Harv. Int'l L.J. 1, 4 (1991) ("[D]espite ubiquitous invocation of the doctrine of comity, its meaning is surprisingly elusive."). |

| 87. |

The CLOUD Act lists seven factors that the court "shall take into account, as appropriate[,]" in its comity analysis: (A) the United States' interests; (B) the foreign governments' interests; (C) the likelihood, extent, nature and penalties that the provider or its employees could face under foreign law; (D) the location and nationality of the target of the demand, and the nature and extent of the target's connections with the United States and the foreign nation; (E) the nature and extent of the provider's ties to and presence in the United States; (F) the importance of the information to the investigation to be disclosed; (G) the ability to access the information through other means; and (H) the investigative interests of the foreign nation if the data is sought by the United States on behalf of a foreign nation. See CLOUD Act § 103(b) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2703(h)(3)). |

| 88. |

See CLOUD Act § 103(b) (adding 18 U.S.C. § 2703(h)). See also § Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act. |

| 89. |

See CLOUD Act § 103(c). |

| 90. |

See Fourth Restatement: Jurisdiction TD 2, § 222. |

| 91. |

See CLOUD Act §§ 104-105. |

| 92. |

See supra notes 1-3. See also Letter from Peter J. Kadzik, U.S. Ass't Att'y Gen., to the Hon. Joseph R. Biden, President, U.S. Senate (July 15, 2016), https://tinyurl.com/y7b7fhaw [hereinafter Kadzik Letter] ("Foreign governments investigating criminal activities abroad increasingly require access to electronic evidence from U.S. companies that provide electronic communications to millions of their citizens and residents. Such data is often stored or accessible only in the United States . . . ."). |

| 93. |

See Tiffany Lin and Mailyn Fidler, Cross-Border Data Access Reform: A Primer on the Proposed U.S.-U.K. Agreement 2 (2017), https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/33867385/2017-09_berklett.pdf?sequence=1 ("Tech companies in the U.S. hold a majority of electronic data, meaning U.K. police investigating a crime in London, for example, may need to access emails stored by a U.S.-based provider."); Woods, supra note 1, at 780 ("[T]he vast majority of the world's Internet users store their data with U.S. firms . . . ."); McGuinness Statement, supra note 3 ("Most communications services are operated by companies based in the United States."). |

| 94. |

See 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(3). |

| 95. |

See, e.g., Aldert Gidari, The Cross-Border Data Fix: It's Not So Simple, Center for Internet and Society, Stanford Law School (Jun. 16, 2017) ("[L]aw enforcement outside the U.S. can't get data for their legitimate investigations from U.S. providers because the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) prohibits such disclosures; that is, ECPA is a classic blocking statute."); Data Stored Abroad Hearing, supra note 1 (statement of Richard Salgado, Dir. of Law Enforcement and Information Security, Google Inc.), https://judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Salgado-Testimony.pdf [hereinafter Salgado Statement] ("ECPA includes a broad, so-called 'blocking' provision that restricts the circumstances under which U.S. service providers may disclose the content of users' communications to foreign governments."). |

| 96. |

See Funk, supra note 16, at 1. |

| 97. |

See infra § "Letters Rogatory." |

| 98. |

See infra § "Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs)." |

| 99. |

See infra § "Executive Agreements Authorized by the CLOUD Act." |

| 100. |

See Intel Corp. v. Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., 542 U.S. 241, 248 n.2 (2004) ("[A] letter rogatory is the request by a domestic court to a foreign court to take evidence from a certain witness.") (emphasis in original) (quoting Harry Leroy Jones, International Judicial Assistance: Procedural Chaos and A Program for Reform, 62 Yale L.J. 515, 519 (1953)); US. Dep't of State, Preparation of Letters Rogatory, Travel.State.Gov, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/travel-legal-considerations/internl-judicial-asst/obtaining-evidence/Preparation-Letters-Rogatory.html [hereinafter Preparation of Letters Rogatory] ("Letters rogatory are requests from courts in one country to the courts of another country requesting the performance of an act which, if done without the sanction of the foreign court, could constitute a violation of that country's sovereignty."). |

| 101. |

See Peter Swire & Justin D. Hemmings, Mutual Legal Assistance in an Era of Globalized Communications: The Analogy to the Visa Waiver Program, 71 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 687, 695 (2017) ("[I]nternational information sharing continued to rely on principles of comity and letters rogatory up until 1977."). |

| 102. |