Class Action Lawsuits: A Legal Overview for the 115th Congress

A class action is a procedure by which a large group of entities (known as a “class”) may challenge a defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct in a single lawsuit, rather than through numerous, separate suits initiated by individual plaintiffs. In a class action, a plaintiff (known as the “class representative,” the “named representative,” or the “named plaintiff”) may sue the defendant not only on his own behalf, but also on behalf of other entities (the “class members”) who are similarly situated to the class representative in order to resolve any legal or factual questions that are common to the entire class.

Courts and commentators have recognized that class actions can serve several beneficial purposes, including economizing litigation and incentivizing plaintiffs to pursue socially desirable lawsuits. At the same time, however, class actions can occasionally subject defendants to costly or abusive litigation. Moreover, because the class members generally do not actively participate in a class action lawsuit, class actions pose a risk that the class representative and his counsel will not always act in accordance with the class members’ best interests. In an attempt to balance the benefits of class actions against the risks to defendants and class members, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 establishes a rigorous series of prerequisites that a federal class action must satisfy. For similar reasons, Rule 23 also subjects proposed class action settlements to the scrutiny of the federal courts.

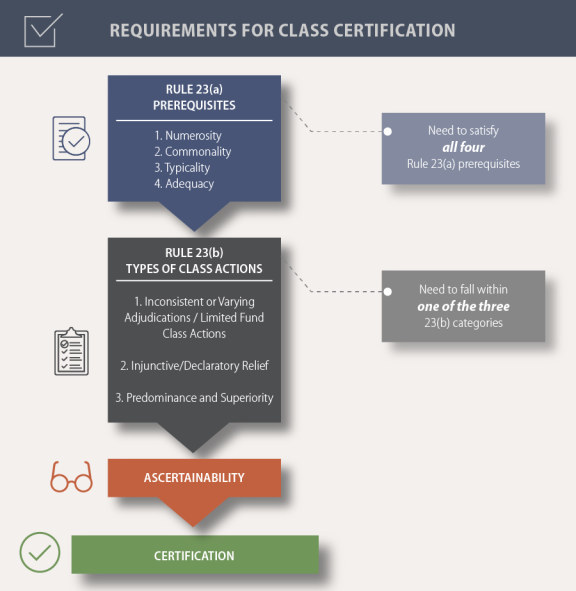

This report serves as a primer on class action litigation in the federal courts. It begins by discussing the purpose of class actions, as well as the risks class actions may pose to defendants, class members, and society at large. The report also discusses the prerequisites that a class action must satisfy before a court may “certify” it—that is, before a federal court may allow a case to proceed as a class action. An Appendix to the report also contains a reference chart that graphically illustrates those prerequisites for class certification. The report then discusses Rule 23’s restrictions on the parties’ ability to settle a certified class action. The report concludes by identifying ways in which Congress could modify the legal framework governing class actions if it were so inclined, with a particular focus on a bill currently pending in the 115th Congress that would effectuate a variety of changes to the class action system.

Class Action Lawsuits: A Legal Overview for the 115th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background on Class Actions

- The Purpose of the Class Action Device

- Economizing Litigation

- Aggregation of Individual Claims

- Protecting Defendants from Inconsistent Adjudications

- Risks of Class Actions

- Abusive and Costly Litigation

- Absent Class Members

- Lawyer-Driven Litigation

- How Class Actions Work

- Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(a)—Mandatory Class Prerequisites

- Numerosity (Rule 23(a)(1))

- Commonality (Rule 23(a)(2))

- Typicality (Rule 23(a)(3))

- Adequate Representation (Rule 23(a)(4))

- Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)—Additional Requirements for Various Types of Class Actions

- Incompatible Standards of Conduct/Limited Funds (Rule 23(b)(1))

- Injunctive or Declaratory Relief (Rule 23(b)(2))

- "Opt Out" Class Actions (Rule 23(b)(3))

- Ascertainability

- Courts Adopting an "Administrative Feasibility" Requirement

- Courts Rejecting an "Administrative Feasibility" Requirement

- Certification

- Subclasses and Certification as to Particular Issues

- Post-Certification

- Settlement

- Legislative Proposals for Changing Class Action Law

- Cohesiveness of the Class

- Codifying the Ascertainability Doctrine

- Divergent Incentives for Class Members and Class Counsel

Summary

A class action is a procedure by which a large group of entities (known as a "class") may challenge a defendant's allegedly unlawful conduct in a single lawsuit, rather than through numerous, separate suits initiated by individual plaintiffs. In a class action, a plaintiff (known as the "class representative," the "named representative," or the "named plaintiff") may sue the defendant not only on his own behalf, but also on behalf of other entities (the "class members") who are similarly situated to the class representative in order to resolve any legal or factual questions that are common to the entire class.

Courts and commentators have recognized that class actions can serve several beneficial purposes, including economizing litigation and incentivizing plaintiffs to pursue socially desirable lawsuits. At the same time, however, class actions can occasionally subject defendants to costly or abusive litigation. Moreover, because the class members generally do not actively participate in a class action lawsuit, class actions pose a risk that the class representative and his counsel will not always act in accordance with the class members' best interests. In an attempt to balance the benefits of class actions against the risks to defendants and class members, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 establishes a rigorous series of prerequisites that a federal class action must satisfy. For similar reasons, Rule 23 also subjects proposed class action settlements to the scrutiny of the federal courts.

This report serves as a primer on class action litigation in the federal courts. It begins by discussing the purpose of class actions, as well as the risks class actions may pose to defendants, class members, and society at large. The report also discusses the prerequisites that a class action must satisfy before a court may "certify" it—that is, before a federal court may allow a case to proceed as a class action. An Appendix to the report also contains a reference chart that graphically illustrates those prerequisites for class certification. The report then discusses Rule 23's restrictions on the parties' ability to settle a certified class action. The report concludes by identifying ways in which Congress could modify the legal framework governing class actions if it were so inclined, with a particular focus on a bill currently pending in the 115th Congress that would effectuate a variety of changes to the class action system.

Introduction

Class action lawsuits—that is, lawsuits by representative parties on behalf of a group of similar plaintiffs that have aggregated their claims in a single action—are frequently in the forefront of debates over the American private law system. According to the Supreme Court, class actions are the "most adventuresome" innovation in American law.1 To some commentators, the class action device is the tool that "gives American workers and consumers the power and ability to level the playing field, even when facing the most powerful corporations in the world."2 To others, class actions are typically brought "to essentially shakedown a defendant—hurting businesses and the American economy."3 Unsurprisingly then, class actions have been a frequent subject of debate in Congress.4

This report serves as a primer5 on class action law and analyzes areas that have been the focus of congressional discussions concerning class actions. The report first discusses the broader public policy debate over class actions, including why class actions exist and what risks they pose to the American system of civil justice. The report then details what a plaintiff is required to show under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in order to achieve class action "certification"—that is, in order to pursue an action on behalf of an entire class. Throughout, the report addresses the ways in which the Supreme Court and lower federal courts have attempted to balance the benefits of class actions against their potential drawbacks.

Lastly, this report discusses key aspects of class action litigation that have been the focus of recent congressional legislative debates. In particular, the report focuses on three areas which have been of particular concern: (1) the cohesiveness (or lack thereof) of the class; (2) ascertainability and administrative feasibility of the class action; and (3) divergent incentives and fees for class counsel compared with the benefits received by class members. The main lens for considering these areas is the Fairness in Class Action Litigation and Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency Act of 2017 (H.R. 985), which passed the House of Representatives in March 2017.6 Accordingly, this report considers how H.R. 985 would modify existing law, along with other potential avenues for change.

Background on Class Actions

The default rule in American litigation is that a lawsuit is conducted by, or on behalf of, the named parties only.7 Class actions, however, are an exception to this rule. A class action is a procedure by which a large group of entities—that is, a "class"8—may challenge a defendant's allegedly unlawful conduct in a single lawsuit, rather than through numerous, separate suits initiated by individual plaintiffs.9 Class actions have an ancient pedigree; analogues to class actions "have been recognized in various forms since the earliest days of English law,"10 and class actions have "been a fixture" of federal litigation in the United States "for over seventy-five years."11 Under the modern version of the class action, a plaintiff12 (known as the "class representative," the "named representative," or the "named plaintiff") may sue the defendant not only on his own behalf, but also on behalf of other entities (the "class members") who are similarly situated to the class representative in order to resolve legal or factual questions that are common to the entire class.13 To illustrate, if, for example, a large number of consumers all purchased a product that turned out to be defective, one of those consumers could potentially bring a single class action against the manufacturer on his own behalf as well as on behalf of all others who purchased the product, thereby eliminating the need for other plaintiffs to join that consumer's lawsuit or initiate their own separate lawsuits.14

Importantly, a class action differs from other forms of litigation involving large numbers of injured persons. In ordinary multiparty litigation, everyone seeking relief from the defendant is a party to the lawsuit and directly participates in the litigation.15 In a class action, by contrast, the class representative is "the only plaintiff[] actually named in the complaint";16 the class members are not formal parties to the lawsuit and typically do not directly guide the litigation.17 The class representative therefore "acts on behalf of the entire class."18 The class members, by virtue of not being directly "present before the court," are often referred to as being "absent" from the litigation.19

The Purpose of the Class Action Device

The Supreme Court has recognized that the class action device serves several purposes.

Economizing Litigation

First, as the Supreme Court has explained, a "principal purpose" of class actions is to advance "the efficiency and economy of litigation."20 By consolidating what would normally be multiple suits or a multiple-plaintiff litigation into a single suit sharing common questions, the class action is "designed to avoid . . . unnecessary filing of repetitious papers and motions."21 If every plaintiff had to independently prove and answer the same common questions, it would typically be "grossly inefficient, costly, and time consuming because the parties, witnesses, and courts would be forced to endure unnecessarily duplicative litigation."22 Class actions thereby potentially economize litigation by consolidating every class member's claim into a single proceeding.

Aggregation of Individual Claims

A class action also enables large numbers of persons injured by a defendant's unlawful conduct "to obtain relief as a group"23 when each class member's individual claim is "too small to justify the expense of a separate suit."24 Oftentimes, when a defendant inflicts comparatively small injuries to a large number of people, no plaintiff standing alone has a sufficient financial "incentive . . . to bring a solo action prosecuting his or her rights."25 As the Supreme Court has noted, a class action resolves this "problem by aggregating the relatively paltry potential recoveries into something worth someone's (usually an attorney's) labor."26

To illustrate, suppose a defendant injures a million consumers for $30.00 in damages each. If each plaintiff had to file a stand-alone suit to recover the money he lost, few would take the trouble to do so. As former federal Judge Richard Posner once colorfully noted, "Only a lunatic or a fanatic sues for $30"27 because the costs of prosecuting the lawsuit would far exceed the maximum award each victim could recover.28 Thus, some legal observers have argued that absent some other deterrent, like a successful criminal prosecution, the defendant's $30 million wrong would go unpunished, and the victims would remain uncompensated. If, however, an individual plaintiff could bring a single class action lawsuit on behalf of everyone the defendant wronged to resolve the common questions, then the plaintiff could potentially aggregate each class member's $30.00 loss, resulting in a potential $30 million recovery.29 That $30 million potential award would then make it economically rational for attorneys to expend time and resources to pursue the class's claims.30 Then, if the plaintiff ultimately prevailed in his class action, the resulting award could be divided among the plaintiff, his counsel, and the other class members.31 In this way, class actions compensate victims who might otherwise go uncompensated32 and punish wrongdoers who might otherwise go unpunished.33 However, as explained in greater detail below,34 a court's decision to not allow a particular lawsuit to proceed as a class action can effectively "sound the 'death knell' of the litigation on the part of the plaintiffs"35 because the individual plaintiff's claim will often be "too small to justify the expense of" prosecuting a non-class action lawsuit.36

Protecting Defendants from Inconsistent Adjudications

Lastly, the Supreme Court has stated that the class action serves to protect defendants from repeated and possibly inconsistent adjudications.37 By consolidating all potential plaintiffs' claims in a single proceeding, a defendant can obtain finality with respect to all future actions, rather than be subject to an unknown number of repeated suits and possibly inconsistent judgments.38 Finality benefits defendants by freeing them from "the distraction of litigation" and by allowing them to "proceed with [their] business affairs more clearly."39

Risks of Class Actions

While the Supreme Court has recognized that the class action device serves several useful purposes, the procedural mechanism also poses risks for the U.S. civil justice system.

Abusive and Costly Litigation

First, because a class action permits thousands or millions of class members to aggregate their claims,40 a defendant who opts to defend rather than settle a class action may face "potentially ruinous liability."41 Consequently, "even if a class's claim is weak, the sheer number of class members and the potential payout that could be required if all members prove liability might force a defendant to settle a meritless claim in order to avoid breaking the company."42 Thus, without effective legal safeguards, class actions could potentially encourage plaintiffs to file lawsuits that have minimal chances of success in order to extract settlements from defendants.43 While it would of course be inaccurate to conclude that all class actions are meritless or abusive, it is fair to say that plaintiffs have sometimes attempted to bring class action lawsuits that could charitably be described as fanciful or humorous. To name one example, a resident of California sued the manufacturer of Cap'n Crunch cereal for deceptive advertising, contending that the defendant had unlawfully misled consumers to believe that "Crunchberries" were made of fruit.44 The court presiding over that case, rather than permitting the case to proceed as a class action, dismissed the case in its entirety, opining that "the survival of the [plaintiff's] claim would require th[e] Court to ignore all concepts of personal responsibility and common sense."45

Additionally, even though class actions may economize litigation in some respects,46 class action litigation still "place[s] an enormous burden of costs and expense upon parties."47 As one federal district judge has maintained, almost "all class action law suits involve complex issues, which are costly to resolve and often result in protracted proceedings."48

Absent Class Members

Secondly, the fact that a class action permits a named plaintiff to represent absent class members raises the concern that the named plaintiff may not always zealously represent the class's interests. As noted above,49 class action litigation "is 'an exception to the usual rule that litigation is conducted by and on behalf of the individual named parties only.'"50 "Class members who are not parties to a class action suit" are generally "bound by the judgment in the suit,"51 even if they have not actively participated in the case in any way52—and, indeed, even if the parties and the court do not (and cannot) know the specific identities of each and every class member.53 Class actions thereby effectively "delegate" the "class members' right to a day in court . . . to the named plaintiff."54 Because class members usually do not control or actively participate in the litigation, class action litigation poses a risk that, without effective safeguards,55 the class representative may "'sell[] out' the interests of absent class members in favor of his or her own"56 self-interest or otherwise fail to fairly represent the class.57

Lawyer-Driven Litigation

Just as class members usually have no direct control over the class representative, class members also typically "have no control over class counsel."58 Because each class member's interest in the case is typically small, class members may have relatively little financial interest in the outcome of the litigation for the class as a whole. For instance, if class counsel obtains a favorable result for the class in the $30 million fraud example described above, each class member may win a maximum of only $30, but class counsel could potentially receive a sizable award of attorney's fees.59 For this reason, courts and commentators have expressed concern that plaintiffs' attorneys may not always act in the best interests of class members, particularly when negotiating a settlement with the defendant. As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit ("Seventh Circuit")60 explained,

Class counsel rarely have clients to whom they are responsive. The named plaintiffs in a class action, though supposed to be the representatives of the class, are typically chosen by class counsel; the other class members are not parties and have no control over class counsel. The result is an acute conflict of interest between class counsel, whose pecuniary interest is in their fees, and class members, whose pecuniary interest is in the award to the class.61

The structure of class actions may thereby give class counsel "an incentive to negotiate settlements that enrich themselves but give scant reward to" the class members62—who, by virtue of being nonparties, may lack a meaningful opportunity to safeguard their interests against enterprising plaintiff's attorneys.63

How Class Actions Work

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 governs the initiation and maintenance of class actions in federal64 court.65 A class action will not bind absent class members unless and until the court presiding over the case "certifies" the proposed class action under Rule 23.66 A court may not certify a class unless

- 1. the proposed class satisfies each of the four mandatory requirements established by Rule 23(a);67

- 2. the proposed class action falls into at least one of the three categories of class actions established by Rule 23(b);68 and

- 3. the membership of the proposed class is "ascertainable."69

A reference chart illustrating the prerequisites for class certification is available in the Appendix of this report.

A court's decision to grant or deny class certification "is often the defining moment" of a class action case.70 On the one hand, a court's decision to deny class certification may effectively "sound the 'death knell' of the litigation on the part of the plaintiffs"71 "because the representative plaintiff's claim is too small to justify the expense of" initiating and litigating an individual suit.72 On the other hand, a court's decision to grant class certification "may force a defendant to settle rather than incur the costs of defending a class action and run the risk of potentially ruinous liability,"73 even if the class's claims have only a minimal chance of success.74 Because the decision to grant or deny certification is so momentous, the Supreme Court has repeatedly instructed federal courts to conduct a "rigorous analysis" confirming that the prerequisites of Rule 23 are satisfied before certifying a class.75 The "court 'must resolve all factual or legal disputes relevant to class certification, even if they overlap with the merits'" of the class members' claims against the defendant.76 Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has cautioned that "merits questions may" only "be considered to the extent . . . that they are relevant to determining whether the Rule 23 prerequisites for class certification are satisfied."77

The court must conduct the class certification analysis at "an early practicable time" after the commencement of the class action.78 "The word 'practicable' imports some leeway in determining the timing of such a decision" by the court.79 Although "the issue of certification should generally be resolved prior to addressing the merits of the plaintiff's claims,"80 there is no categorical rule prohibiting courts from ruling on case-dispositive motions before deciding whether to certify the proposed class.81

"A party seeking class certification" bears the burden to "affirmatively demonstrate his compliance with" each of the requirements described below,82 and he must satisfy that burden "by a preponderance of the evidence."83 It is not sufficient to merely "plead compliance with the . . . Rule 23 requirements"; the plaintiff must instead introduce "evidence that the putative class complies with Rule 23."84

If a court determines that the class satisfies the requirements for certification, then Rule 23 directs the court to issue a certification order that defines the class and appoints class counsel.85 As explained later in this report,86 a court can certify "subclasses" with separate legal representation in a single action, and should do so where interests within the proposed class might diverge.87 Lastly, the court should then direct notice to the class members as required by Rule 23.88 The notice required depends on the category under which the class which is certified.89

The sections that follow analyze each of the requirements for class certification in detail.90

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(a)—Mandatory Class Prerequisites

First, a court may not certify a class action unless the proposed class satisfies all four of the mandatory requirements established by Rule 23(a).91 "Rule 23(a) ensures that the named plaintiffs are appropriate representatives of the class whose claims they wish to litigate. The Rule's four requirements—numerosity, commonality, typicality, and adequate representation—effectively limit the class claims to those fairly encompassed by the named plaintiff's claims."92

Numerosity (Rule 23(a)(1))

The plaintiff must first show that the proposed "class is so numerous that joinder of all members"—that is, identifying everyone who claims to be injured by the defendant's conduct and having them actively participate in the lawsuit as named parties—would be "impracticable."93 This prerequisite is known as the "numerosity" requirement.94 "The numerosity requirement exists because the power of class actions to bind absent class members carries due process risks and should be invoked only when necessary"—namely, when it would not be possible or practicable for all of the class members to participate as formal parties to the suit.95

Although the text of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 is "conspicuously devoid of any numerical minimum" of class members "required for class certification,"96 "numerosity is generally satisfied if there are more than 40 class members,"97 and generally unsatisfied if the proposed class contains 20 members or fewer.98 Courts give "classes with between 21 and 40 members . . . varying treatment"; "these midsized classes may or may not meet the numerosity requirement depending on the circumstances of each particular case."99 While the number of class members is the "starting point" of the numerosity analysis,100 "the number of members in a proposed class is not determinative of whether joinder is impracticable."101 Courts also consider a variety of other factors when evaluating numerosity, the most common of which include (i) whether the class members are geographically dispersed; (ii) the financial resources of the class members; (iii) the burden that multiple individual actions would place on the judiciary; and (iv) the ease with which class members may be identified.102

Commonality (Rule 23(a)(2))

The plaintiff must then show that "there are questions of law or fact common to the class."103 This prerequisite is known as the "commonality" requirement,104 and it exists to ensure that the claims of the full class are "limit[ed] . . . to those fairly encompassed by the named plaintiff's claims."105

In its 2010 decision in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, the Supreme Court explained that the commonality prerequisite requires more than an incidental common question within the class; rather, the plaintiff must establish that the claims "depend upon a common contention" that is of such a nature that "determination of its truth or falsity will resolve an issue that is central to the validity of each one of the claims in one stroke."106 Commentators generally agree that Wal-Mart expanded the significance of commonality.107 There, the Court reviewed a decision certifying a proposed class of approximately 1.5 million former and current female Wal-Mart employees. The plaintiffs asserted a sex discrimination against Wal-Mart under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, alleging that local Wal-Mart supervisors favored men over women when exercising their discretion over pay and promotion.108 The plaintiffs presented statistical evidence that local managers were disproportionately using their discretionary authority to favor men, but they did not present any evidence of an express corporate policy against women.109 The question before the Court was whether this proposed class met the requirement of commonality, given the different nature of the alleged discrimination faced by each class member. As the Court observed, the class members certainly raised "common questions"—for example, "[d]o all of us plaintiffs indeed work for Wal-Mart?" or "[d]o all of our managers have discretion over pay?" or even "[i]s that an unlawful employment practice?"110 Nevertheless, these sorts of questions were, in the view of the Court, insufficient to satisfy the commonality requirement, as "any competently crafted class complaint literally raises common 'questions.'"111

Instead, the Court explained that, to satisfy the commonality requirement, a plaintiff must "demonstrate that the class members 'have suffered the same injury.'"112 "This does not mean merely that" all of the class members have allegedly "suffered a violation of the same provision of law."113 Rather, the claims must depend on a common contention that is "capable of classwide resolution"; a classwide proceeding must "generate common answers apt to drive the resolution of the litigation."114 The Court explained that the plaintiffs in Wal-Mart could not satisfy that requirement because, due to the nature of the underlying Title VII claim, "it w[ould] be impossible to say that examination of all the class members' claims for relief will produce a common answer to the crucial question of why was I disfavored."115 Because the plaintiffs in Wal-Mart had presented no evidence of a general corporate policy of discrimination, there was no reason to believe that every class member could point to the same common answer.116 Lower courts have since affirmed that, as in Wal-Mart, a plaintiff generally cannot satisfy the commonality requirement "where the defendant's allegedly injurious conduct differs from plaintiff to plaintiff."117

Nevertheless, "commonality does not require perfect identity of questions of law or fact among all class members,"118 and there is no requirement "that every question be common" to the class.119 To the contrary, "even a 'single common legal or factual issue can suffice'" to satisfy the commonality requirement, provided that all class members have suffered from the same injurious conduct.120 For example, in Suchanek v. Sturm Foods, Inc., the Seventh Circuit concluded that the district court erred in finding that there was no commonality in a consumer class action involving Keurig-style coffee pods.121 The defendant in Suchanek sold a product which outwardly resembled the original Keurig-brand coffee pods, but which contained instant coffee rather than fresh coffee grounds.122 Plaintiffs argued that the packaging was deceptive and sought to certify a class on behalf of all consumers of the defendant's product in several states to resolve the common question of whether the packaging was in fact deceptive.123 The district court refused to certify the class action due to variation within the class members claims.124 For example, in the view of the district court, some class members may have purchased different versions of the packaging in question.125 However, the Seventh Circuit vacated the district court's order denying class certification, explaining that these differences within the proposed class did not preclude certification.126 The Seventh Circuit explained that all that mattered for commonality was the existence of a question decisive to all class members that was capable of a common resolution.127 The court concluded that the question of whether the packaging in question was materially misleading to a reasonable person satisfied the commonality requirement because the success of each class member's state law fraud claim depended, at least in part, on the basis of the answer to that question.128 Nor did it matter for the appellate court that some members of the proposed class were uninjured because, for example, they did not rely on the allegedly deceptive packaging.129 For the Seventh Circuit, "[h]ow many (if any) of the class members have a valid claim is the issue to be determined after the class is certified."130 In sum, although Wal-Mart reinforces that Rule 23(a)(2)'s commonality requirement is rigorous,131 cases like Suchanek indicate that the commonality requirement is not an insurmountable barrier to class certification.132

Typicality (Rule 23(a)(3))

Third, the proposed class representative must satisfy what is known as the "typicality" requirement133—that is, that "the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class."134 The primary purpose of the typicality requirement is to ensure that "the interests of the class and the class representatives are aligned 'so that the latter will work to benefit the entire class through the pursuit of their own goals.'"135 A proposed class will generally satisfy the typicality requirement if the class representative's claim against the defendant is based on roughly the same legal and factual basis as the claims of the absent class members that the class representative seeks to represent.136 "Representative claims are 'typical' if they are reasonably coextensive with those of absent class members; they need not be substantially identical."137 Thus, "even relatively pronounced factual differences" between the named plaintiff's claims and those of the class members "will generally not preclude a finding of typicality where there is a strong similarity of legal theories."138

Many courts, when evaluating whether a proposed class action satisfies the typicality requirement, also inquire whether the proposed class representative's claim "arises from the same event or practice or course of conduct that gives rise to the claims of other class members."139 In this respect, the typicality requirement "tend[s] to merge" with the commonality requirement,140 which likewise examines whether "the same conduct or practice by the same defendant gives rise to the same kind of claims from all class members."141 Other courts have suggested that typicality overlaps with the "adequate representation" requirement discussed below,142 which similarly seeks to ensure that representative parties "adequately protect the interests of the class."143

Adequate Representation (Rule 23(a)(4))

Fourth, a plaintiff must demonstrate that "the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class."144 This prerequisite is alternatively known as the "adequacy of representation" requirement,145 the "adequate representation" requirement,146 or just the "adequacy" requirement.147 The "adequate representation inquiry consists of two parts":

- 1. "The adequacy of the named plaintiffs as representatives of the proposed class's myriad members, with their differing and separate interests"; and

- 2. "The adequacy of the proposed class counsel."148

Adequacy of the Class Representative

"The adequacy inquiry" serves primarily "to uncover conflicts of interest between named parties and the class they seek to represent."149 "To assure vigorous prosecution" of the proposed class action, courts consider

- 1. "Whether the class representative has adequate incentive to pursue the class's claim"; and

- 2. "Whether some difference between the class representative and some class members might undermine that incentive."150

"Conflicts of interest between the named plaintiffs and the class they seek to represent" can potentially defeat class certification on adequacy grounds.151 Importantly, however, a conflict between the class representative and the absent class members will defeat class certification only if the conflict is "fundamental to the suit" and goes "to the heart of the litigation."152

The Supreme Court's opinion in Amchem Products v. Windsor illustrates this concept.153 In that case, the plaintiffs sought to certify a settlement-only class consisting of all persons who had either been exposed or who had a family member who was exposed to the defendant's asbestos—a class of unknown size that may well have contained tens of thousands of persons.154 The action sought to settle all present and future asbestos-related claims that might be brought against the defendant, once and for all, on behalf of this untold number of class members, some of whom were already sick and others of whom were presently uninjured and might never be injured in the future.155

The Supreme Court concluded that this proposed class action could not proceed for a number of reasons, one of which was that the class could not satisfy the adequacy requirement.156 The proposed class contained both the currently injured and those who might manifest an injury only in the future, leading to a "serious intra-class conflict."157 In particular, the uninjured plaintiffs had an interest in an "ample, inflation-protected fund for the future," while currently injured plaintiffs had the diametrically opposed interest of "generous immediate payments."158 Because of these conflicts of interest, the Court concluded that structural assurances of fairness, like separate subclasses with separate representation,159 were needed to ensure adequate representation.160 After Amchem, the lower courts have avoided similar conflicts of interest by certifying separate subclasses, each with their own counsel and class representative.161

Not all conflicts, however, require such treatment. Some conflicts are not fundamental, and therefore do not threaten class certification on adequacy grounds. For instance, most courts have agreed that a named plaintiff's eligibility for "incentive awards that are intended to compensate class representatives for work undertaken on behalf of a class . . . do not, by themselves, create an impermissible conflict between class members and their representatives," even if those incentive awards will result in the named plaintiff receiving more money than the absent class members.162 Because such awards do not dull the named plaintiff's motivation to "prosecute the action vigorously on behalf of the class," a named plaintiff who stands to receive an incentive award at the conclusion of the litigation will generally be able to adequately represent the class.163

In addition to assessing whether a fundamental conflict renders the named plaintiff unable to adequately represent the absent class members, a few courts also consider whether the proposed class representative "possess[es] a sufficient level of knowledge and understanding to be capable of 'controlling' or 'prosecuting' the litigation."164 Many other courts, however, "disfavor . . . 'attacks on the adequacy of a class representative based on the representative's ignorance'" about the litigation, especially in complex cases.165

Adequacy of Class Counsel

The adequacy inquiry also requires the court to evaluate the "competency and conflicts of class counsel."166 The court must ensure that the attorney who seeks to represent the class is "qualified, experienced, and generally able to conduct the litigation."167

Rule 23 "lists several non-exclusive factors that a district court must consider in determining 'counsel's ability to fairly and adequately represent the interests of the class,'"168 including

- 1. the work counsel has done in identifying or investigating potential claims in the action;

- 2. counsel's experience in handling class actions, other complex litigation, and the types of claims asserted in the action;

- 3. counsel's knowledge of the applicable law; and

- 4. the resources that counsel will commit to representing the class.169

Under this section, courts have also scrutinized any conflicts that a class representative may have with class counsel. As the Seventh Circuit explained in Eubank v. Pella Corporation, "[c]lass representatives are . . . fiduciaries of the class members, and fiduciaries are not allowed to have conflicts of interest without the informed consent of their beneficiaries."170 In that case, the court reversed an order certifying a class because the class counsel was the son-in-law of the class representative, leading to a "grave conflict of interest" because the class representative had less reason to attempt to constrain the fee to counsel.171 Other courts have found that representation is inadequate where the named plaintiff was a friend and former business partner with class counsel,172 or where the named plaintiff was an employee of class counsel.173

However, not every preexisting relationship between class counsel and the named plaintiff is fatal to class certification. In Levitt v. Southwest Airlines Co., for example, the Seventh Circuit upheld a class where one of the two class representatives was co-counsel with lead class counsel in a separate case.174 Although the Levitt court reduced the attorney's fee award by $15,000 because the attorney had failed to disclose the conflict, the court nonetheless affirmed the class certification order in part because counsel had successfully obtained a favorable settlement for the class.175

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)—Additional Requirements for Various Types of Class Actions

"In addition to the[] four general requirements" for classes established by Rule 23(a), "there are additional requirements that must be met depending on the type of class [action] the [plaintiff] seeks to certify."176 "There are three types of class actions that can be maintained, and Rule 23(b)(1)-(3) specifies the additional requirements that apply to each of them."177 If the proposed class action does not satisfy the requirements of any of those three categories, the court must deny class certification.178 As is true of the Rule 23(a) requirements, the court must perform "a rigorous analysis" to determine whether the Rule 23(b) requirements are satisfied.179

Incompatible Standards of Conduct/Limited Funds (Rule 23(b)(1))

Rule 23(b)(1) provides that a class action may be maintained if prosecuting separate actions by individual class members would create a risk of

(A) inconsistent or varying adjudications with respect to individual class members that would establish incompatible standards of conduct for the party opposing the class; or

(B) adjudications with respect to individual class members that, as a practical matter, would be dispositive of the interests of the other members not parties to the individual adjudications or would substantially impair or impede their ability to protect their interests.180

Class members have no right to opt out of a Rule 23(b)(1) class,181 as "allowing class members to opt out of the class and pursue individual claims would deplete the fund to the detriment of other class members."182

Inconsistent or Varying Adjudications (Rule 23(b)(1)(A))

"The phrase 'incompatible standards of conduct' refers to the situation where 'different results in separate actions would impair the opposing party's ability to pursue a uniform continuing course of conduct.'"183 So, for example, if separate lawsuits proceeding in different courts could result in one court ordering the defendant to reimburse a plaintiff from a retirement plan while another court prohibits the plaintiff from recovering anything from that plan, then "the risk of inconsistent orders . . . satisfies Rule 23(b)(1)(A)."184

Limited Fund Class Actions (Rule 23(b)(1)(B))

"Class actions certified under Rule 23(b)(1)(B) . . . typically involve limited pools of money that may not be adequate to cover the claims of all plaintiffs,"185 as may occur when there are "multiple claims to a single, tangible fund, such as a bank account, trust, insurance policy, or proceeds from a sale of an asset."186 In such cases involving "limited funds," "every award made to one claimant" would reduce "the amount of funds available to other claimants until, in the absence of equitable management of the fund, some claimants are able to obtain full satisfaction of their claims, while others are left with no recovery at all."187 Rule 23(b)(1)(B) therefore ensures "equitable distribution of those limited funds, so that the first plaintiffs bringing claims do not deprive later suing plaintiffs the opportunity to press their own claims."188 Rule 23(b)(1)(B) classes are therefore "designed to protect plaintiffs from one another."189

Injunctive or Declaratory Relief (Rule 23(b)(2))

A plaintiff may obtain class certification pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) by demonstrating that "the party opposing the class has acted or refused to act on grounds that apply generally to the class, so that final injunctive relief or corresponding declaratory relief is appropriate respecting the class as a whole."190 "Colloquially, 23(b)(2) is the appropriate rule to enlist when the plaintiffs' primary goal is not monetary relief, but rather to require the defendant to do or not do something that would benefit the whole class."191

In order to obtain class certification under Rule 23(b)(2), the plaintiff must demonstrate that "a single injunction or declaratory judgment would provide relief to each member of the class."192 Rule 23(b)(2) does "not authorize class certification when each individual class member would be entitled to a different injunction or declaratory judgment against the defendant."193 In other words, the relief sought by the proposed class must be "indivisible, benefitting all members of the (b)(2) [c]lass at once."194

Nor does Rule 23(b)(2) "authorize class certification when each class member would be entitled to an individualized award of monetary damages."195 Courts generally agree that "a 23(b)(2) class cannot seek money damages unless the monetary relief" sought is merely "incidental to the injunctive or declaratory relief" requested by the class.196

Rule 23(b)(2), like Rule 23(b)(1), generally "provides no opportunity for (b)(2) class members to opt out."197 Courts have concluded that "these procedural safeguards are not required because a (b)(2) class is presumed to be homogenous in nature, with few conflicting interests among its members."198 As a result, "all class members" of a certified Rule 23(b)(2) class will generally "be bound by a single judgment" at the conclusion of the litigation.199

"Opt Out" Class Actions (Rule 23(b)(3))

"The most common" type of class action is an action certified pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3),200 which authorizes "class actions for damages designed to secure judgments binding all class members save those who affirmatively elected to be excluded" from the class.201 "Rule 23(b)(3) applies to most classes seeking monetary relief."202 Unlike the two types of class action described above, Rule 23(b)(3) grants class members an opportunity to opt out of the class, as explained in greater detail below.203

"To qualify for certification under Rule 23(b)(3), a proposed class must meet two prerequisites beyond the Rule 23(a) prerequisites."204 The plaintiff must demonstrate that:

- 1. "The questions of law or fact common to class members predominate over any questions affecting only individual members"; and

- 2. "A class action is superior to other methods for fairly and efficiently adjudicating the controversy."205

These prerequisites are known as "predominance" and "superiority," respectively.206

Predominance

"The Rule 23(b)(3) predominance inquiry tests whether proposed classes are sufficiently cohesive to warrant adjudication by representation."207 The predominance requirement's "purpose is to 'ensure that the class will be certified only when it would achieve economies of time, effort, and expense, and promote uniformity of decision as to persons similarly situated, without sacrificing procedural fairness or bringing about other undesirable results.'"208 The predominance question is complex, and courts have not set forth a clear methodology for determining whether a proposed class action satisfies the predominance requirement.209 Most courts agree that "[t]he main concern of the predominance inquiry under Rule 23(b)(3) is the balance between" the "individual and common" questions raised by the proposed class action.210 "An individual question is one where 'members of a proposed class will need to present evidence that varies from member to member.'"211 A common question, by contrast, "is one where 'the same evidence will suffice for each member to make a prima facie showing [or] the issue is susceptible to generalized, class-wide proof.'"212 A plaintiff may satisfy the predominance requirement if the "issues that are 'susceptible to generalized, class-wide proof' are 'more prevalent or important'" to the case than the issues that require individualized proof.213

The Supreme Court has provided general guidelines on predominance. The most significant Supreme Court case on predominance is Amchem, discussed above.214 There, the Court rejected a class containing all persons who had either been exposed or who had a family member who was exposed to the defendant's asbestos.215 In considering whether to certify this class, the Court, explaining that the purpose of predominance is to test "whether proposed classes are sufficiently cohesive to warrant adjudication by representation," held that there were too many questions of too great a significance which were peculiar to the categories of class members and to individual class members for predominance to be met.216 Specifically, the Court noted the following:

Class members were exposed to different asbestos-containing products, for different amounts of time, in different ways, and over different periods. Some class members suffer no physical injury . . . each has a different history of cigarette smoking . . . . Differences in state law . . . compound these disparities.217

Amchem thus stands for the proposition that divergent questions on the facts or on the law within the class can defeat predominance. So, for example, many lower courts have held that a proposed class action may violate the predominance requirement if each class member's claim is governed by a materially different set of substantive laws, which can occur when class members who live in different states sue the defendant under different state laws.218 Where "variations in state law raise the potential for the application of multiple and diverse legal standards and a related need for multiple jury instructions" or "multiply the individualized factual determinations that the court would be required to undertake in individualized hearings,"219 those variations may "overwhelm the ability of the trier of fact meaningfully to advance the litigation through classwide proof" and thereby defeat predominance.220

However, the lower courts have not concluded that any difference of circumstance or damages within the class automatically means a failure to meet the predominance requirement. For example, the Seventh Circuit suggested that predominance could be satisfied in Suchanek v. Sturm Foods, Inc.,221 also discussed above.222 In that case, involving consumers in eight different states who had purchased instant-coffee coffee pods, the class of consumers would have encountered the allegedly deceptive advertising necessarily in a particularized context based on the individual's circumstances, leading to individualized questions on reliance and causation. Nonetheless, the court concluded that the question of whether the advertising was materially misleading could still be resolved on a class basis.223 The court explained that, because it "would be a straightforward matter" to resolve the individualized issues of reliance and causation in "individualized follow-on proceedings," class certification was likely appropriate.224

Similarly, courts have generally confirmed that individualized damages inquiries generally do not preclude class certification.225 Because "individual issues of damages" are often "easy to resolve because the calculations are formulaic" and "district courts have many tools to decide individual damages" in an efficient manner, individualized damages calculations will rarely eclipse the issues common to all class members.226 Thus, in most jurisdictions, the plaintiff "need not show that each member's damages . . . are identical" in order to obtain class certification.227

Lastly, a few federal appellate courts have held that "[e]ven if the common questions do not predominate over the individual questions so that class certification of the entire action is warranted, Rule 23 authorizes the district court in appropriate cases to isolate the common issues under Rule 23(c)(4)(A) and proceed with class treatment of these particular issues."228 However, the Fifth Circuit, in its oft-cited opinion in Castano v. American Tobacco Co., disagreed, stating that Rule 23(c)(4) may not be used to sever particular issues in order to avoid the application of predominance to the entire claim; according to the Fifth Circuit, Rule 23(c)(4) is simply a "housekeeping rule" which permits courts to certify particular issues when the class as a whole meets the other requirements of the Rule.229 The Third Circuit has adopted yet another approach, applying a multifactor test to determine whether it is appropriate to certify an issue class.230

Superiority

In addition to satisfying the predominance requirement, a plaintiff seeking certification of an opt-out class pursuant to Rule 23(b)(3) must also show that "a class action is superior to other methods for fairly and efficiently adjudicating the controversy."231 "The focus of this analysis is on 'the relative advantages of a class action suit over whatever other forms of litigation might be realistically available to the plaintiffs.'"232 To determine whether a class action would be superior to the available alternatives, the Rule sets out four factors for courts to consider:

(A) the class members' interests in individually controlling the prosecution or defense of separate actions;

(B) the extent and nature of any litigation concerning the controversy already begun by or against class members;

(C) the desirability or undesirability of concentrating the litigation of the claims in the particular forum; and

(D) the likely difficulties in managing a class action.233

These four factors are "nonexhaustive."234

The last of those four factors—"the likely difficulties in managing a class action,"235 also known as "manageability"—"is, by far, the most critical concern in determining whether a class action is a superior means of adjudication."236 To determine whether a proposed class action would be more manageable than alternative methods for adjudicating the dispute, the court must consider "the whole range of practical problems that may render the class action format inappropriate for a particular suit,"237 such as "potential difficulties in notifying class members of the suit, calculation of individual damages, and distribution of damages."238

The superiority inquiry asks not whether the proposed class action "will create significant management problems," but rather "whether it will create relatively more management problems than any of the alternatives" potentially available to the class members.239 If the mere existence of manageability problems was enough to defeat class certification, then no class action would ever be certified, as virtually "all class actions pose[] manageability concerns" by virtue of their scope and complexity.240

"The superiority of a class action also depends on the existence of a realistic alternative to class litigation."241 For instance, the court could compare the advantages and disadvantages of allowing the case to proceed as a class action to those of other adjudicatory procedures, such as "multiple individual actions, coordinated individual actions, consolidated individual actions, [or] test cases."242 However, a proposed class action generally satisfies the superiority requirement if the plaintiff's claims would likely not be adjudicated at all absent a class action.243

Proposed class actions are particularly likely to satisfy the superiority requirement "where recovery on an individual basis would be dwarfed by the cost of litigating on an individual basis."244 Where, by contrast, "individual damages run high," such that individual class members "have a substantial stake in the dispute and" consequently "do not lack the means of obtaining representation," then separate suits by individual plaintiffs may be a realistic and superior alternative to class action litigation.245

Notice and Opt-Out

"Class members are bound by [any] judgment" ultimately entered in a certified class action, "whether favorable or unfavorable."246 Thus, to protect the rights of absent class members, Rule 23(b)(3) affords class members an opportunity to withdraw from—that is, "opt out"247—of a certified Rule 23(b)(3) class.248 A person who opts out of a certified Rule 23(b)(3) class will not be bound by any judgment or settlement ultimately entered in the case.249 He may then, if he wishes, commence his own individual lawsuit challenging the defendant's alleged misconduct.250

Ascertainability

Most courts have concluded that, in addition to the aforementioned prerequisites enumerated in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(a)-(b), a plaintiff seeking to certify a class action must also show that the membership of the proposed class is "ascertainable."251 Although not articulated in Rule 23 explicitly, courts have concluded that Rule 23 implicitly requires the named plaintiff to prove that members of the proposed class are "ascertainable."252 To satisfy this "ascertainability" requirement, "the members of the proposed class" must be "readily identifiable."253 "The purpose of the ascertainability requirement is to avoid 'satellite litigation' over who is a member of the class and to 'properly enforce the preclusive effect of [a] final judgment' by clarifying 'who gets the benefit of any relief and who gets the burden of any loss.'"254

Significantly, however, courts have disagreed regarding what a plaintiff must prove in order to satisfy the ascertainability requirement.255 As explained below, some courts have required the named plaintiff to demonstrate an "administratively feasible mechanism" for determining whether putative class members fall within the class definition, while other courts have explicitly refused to adopt any such requirement.

Courts Adopting an "Administrative Feasibility" Requirement

For example, to certify a class action in the Third and Eleventh Circuits, the plaintiff must show that

- 1. "the class is defined with reference to objective criteria"; and

- 2. "there is a reliable and administratively feasible mechanism for determining whether putative class members fall within the class definition."256

To be "defined with reference to objective criteria,"257 membership in a class cannot be based on subjective considerations "such as class members' state of mind."258 The "administratively feasible" requirement, by contrast, mandates that there be "a 'manageable process'" to identify class members "that does not require much, if any, individual inquiry."259 "If individualized fact-finding or mini-trials will be required to prove class membership," then the proposed class action cannot "satisfy the ascertainability requirement."260 As a result, when a plaintiff alleges, for instance, that a defendant manufacturer falsely and deceptively advertised a product to the class members, but the plaintiff produces no evidence that it would ultimately be possible to identify which purchasers bought that product, that plaintiff cannot satisfy the administrative feasibility requirement.261 If, by contrast, "'objective records' . . . can 'readily identify'" who purchased the product in question, then the plaintiff can satisfy the administrative feasibility requirement.262

Courts Rejecting an "Administrative Feasibility" Requirement

Other courts, including the Second, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits, have concluded that the plaintiff is not required to "prove at the certification stage that there is a 'reliable and administratively feasible' way to identify all who fall within the class definition."263 Instead, plaintiffs in these jurisdictions need only demonstrate that membership in the proposed class is "defined clearly and based on objective criteria."264 So, for instance, a class composed of "persons who acquired specific securities during a specific time period" satisfies the objective criteria requirement, as the "subject matter, timing, and location" of those purchases are all a matter of objective fact.265 On the other hand, "classes that are defined by subjective criteria, such as by a person's state of mind, fail the objectivity requirement" even in jurisdictions that have not adopted the administrative feasibility requirement.266

Certification

If the plaintiff satisfies all of the applicable requirements discussed in the previous sections of this report,267 the court may enter an order "certify[ing] the action as a class action."268 "An order that certifies a class action must define the class and the class claims, issues, or defenses, and must appoint class counsel."269 Once a class is certified according to Rule 23, all class members—except for members of a Rule 23(b)(3) class who affirmatively opt out—are bound by the court's rulings in the case.270

Importantly, "certification of a class is always provisional in nature until the final resolution of the case."271 "A district court 'retains the ability to monitor the appropriateness of class certification throughout the proceedings and to modify or decertify a class at any time before final judgment.'"272

Ordinarily, interlocutory orders (that is, nonfinal judgments) are not appealable.273 Accordingly, a litigant may generally not immediately appeal a district court's order granting or denying class certification.274 However, because a district court's decision to grant or deny class certification is so consequential, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure grant the federal courts of appeals "broad discretion"275 to permit a litigant to file an interlocutory appeal "from an order granting or denying class action certification."276 Appellate courts apply a variety of legal standards when deciding whether to grant an interlocutory appeal of an order granting or denying class certification.277 However, most courts consider whether the class certification order is "manifestly erroneous,"278 as well as whether granting an interlocutory appeal will allow the appellate court to resolve an unsettled and important issue of class action law.279

Subclasses and Certification as to Particular Issues

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 authorizes the court to divide a class "into subclasses that are each treated as" a separate class for the purposes of the class action.280 Splitting a proposed class into subclasses may be appropriate, for example, "to prevent conflicts of interest" between subgroups of class members281 that might otherwise preclude class certification on adequacy282 grounds.283 "District courts have broad discretion in determining whether to . . . divide a class action into subclasses."284

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 also authorizes the court to permit an action to proceed as a class action only "with respect to particular issues."285 So, for instance, "if a case requires determinations of individual issues of causation and damages" that cannot be resolved classwide, "a court may 'bifurcate the case into a liability phase and a damages phase,'" whereby the court determines liability on a classwide basis and then conducts separate individualized hearings to determine each class member's damages.286

Post-Certification

"Once certified, the class action can then proceed to discovery, pretrial, and trial."287 The members of the certified class who do not (or cannot) opt out of the class will generally be bound by any judgment ultimately rendered in the case with respect to the issues that have been certified.288 Because a certified class action potentially presents "opportunities for abuse as well as problems for courts and counsel in the management of cases . . . a district court has both the duty and the broad authority to . . . enter appropriate orders governing the conduct of counsel and parties,"289 such as "orders that . . . determine the course of proceedings or prescribe measures to prevent undue repetition or complication in presenting evidence or argument."290

Settlement

Significantly, however, "very few class actions are tried";291 most instead culminate in a settlement.292 Just as a final judgment entered in a certified class action that proceeds to trial generally binds the absent class members, a class action settlement typically binds absent class members293 who do not (or cannot) opt out of the class.294 Because "plaintiffs in a class action may release claims that were or could have been pled in exchange for settlement relief"; a settlement agreement may thereby preclude class members from pursuing "claims not presented in the complaint" if those claims are "based on the identical factual predicate as that underlying the claims in the settled class action."295

Because the settlement of a certified class action will bind absent class members,296 "the claims, issues, or defenses of a certified class may be settled, voluntarily dismissed, or compromised only with the court's approval,"297 and "any class member may object to the" proposed settlement of a certified class action.298 "The court may approve" the proposed settlement "only after a hearing and on finding that it is fair, reasonable, and adequate."299 "The burden is on the settlement proponents to persuade the court that the agreement is fair, reasonable, and adequate for the absent class members who are to be bound by the settlement."300 Although different courts consider different factors when determining whether a proposed settlement is "fair, reasonable, and adequate,"301 the following factors are particularly common:

- whether the class members favor or disfavor the proposed settlement;

- the complexity, expense, and likely duration of the continued litigation that would occur if the court rejected the settlement;

- the likelihood that the class would prevail if the case proceeded to a trial on the merits; and

- the current stage of the litigation and the amount of discovery the parties have completed.302

When evaluating a proposed class action settlement, the court must also determine whether "any attorneys' fees claimed as part of the settlement are reasonable" and whether "the settlement itself is reasonable in light of those fees."303 To make that determination, the court assesses whether the proposed award of attorney's fees is "unreasonably excessive in light of the results achieved" by the proposed settlement.304

Additionally, the court must evaluate whether the proposed settlement will actually benefit the class in some meaningful way.305 The court must "be assured that the settlement secures an adequate advantage for the class in return for" absent class members giving up their "litigation rights against the defendants."306 So, for instance, a court may not approve a settlement that affords class counsel a substantial fee but gives the class nothing but effectively worthless injunctive relief.307

Legislative Proposals for Changing Class Action Law

As the foregoing discussion illustrates, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the federal courts interpreting those rules have attempted to balance the interests inherent in the class action device. If Congress concludes that Rule 23 and the judicial decisions interpreting it have properly struck that balance, it may leave the existing class action framework unchanged.

If, instead, Congress wishes to modify the existing laws governing class actions to make them more or less favorable to plaintiffs, defendants, class members, or class counsel, Congress has multiple options. Calls to modify the class action framework have primarily focused on three areas: (1) the cohesiveness (or lack thereof) of the class; (2) ascertainability and the administrative feasibility of the class action; and (3) divergent incentives and fees for class counsel compared with the benefits received by class members. For instance, Members of Congress have introduced a variety of proposals to change the class action system in recent years, including modifying Rule 23,308 restricting the ability of private parties to waive class action treatment in financial adviser contracts,309 and proposing that certain classes would be presumed to meet the requirement of commonality.310 Most notably, on March 9, 2017, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 985, known as the Fairness in Class Action Litigation and Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency Act of 2017 (FICALA).311 FICALA represents possibly the most sweeping set of proposed modifications to the class action device that has been proposed in years, suggesting a host of changes to the operation of class actions in federal courts.

Cohesiveness of the Class

Cohesiveness was the focus of the Supreme Court's attention in both Amchem and Wal-Mart, discussed above.312 In each of those cases, the Court reversed the certification of the class action because, in one way or another, the class claims had severe differences which made class treatment inappropriate.313 The Court in Wal-Mart framed the lack of cohesiveness as being about commonality—the lack of a single common question which could resolve an issue "central to the validity of each one of the claims in one stroke."314 In Amchem, this concern about cohesion centered on Rule 23(b)(3)'s predominance requirement: the number and importance of the disparate questions among the class members claims made class treatment inappropriate.315

As noted above, however, there is no consistent approach in the lower courts with respect to cohesiveness on either commonality or predominance.316 Splits have arisen between the federal courts as to a number of questions, such as the importance of individualized damages to the predominance inquiry317 and the use of the issue class to segregate the common issues notwithstanding predominance for the claim as a whole.318 Some commentators and judges (including some Supreme Court Justices in dissent) have argued that the courts have failed to strike the correct balance.319 Some have maintained that some courts have expanded class action certification beyond the bounds of what should be permissible particularly with respect to classes including both injured and uninjured parties, impermissibly broadening the traditional power of courts.320 Others disagree and argue that the courts have placed too much emphasis on cohesiveness at the expense of judicial efficiency, suggesting that the class action should be expanded further.321

As passed by the House, FICALA proposes to add several sections to Title 28 of the U.S. Code that would alter this area of class action law. Proposed 28 U.S.C. § 1716 would bar federal courts from certifying a class seeking monetary relief for personal injury or "economic loss" unless the plaintiff demonstrates that "each proposed class member suffered the same type and scope of injury as the named class representative."322 Every certification order in federal court would have to contain a determination "based on a rigorous analysis of the evidence presented" that the plaintiff certified this requirement.323 FICALA does not define the phrase "type and scope of injury."324

FICALA would also add 28 U.S.C. § 1720, which would prohibit so-called "issue classes," by prohibiting a federal court from issuing "an order granting certification . . . with respect to particular issues pursuant to Rule 23(c)(4)325 . . . unless the entirety of the cause of action from which the particular issues arise satisfies all the class certification prerequisites" of Rule 23.326

The committee report from the House Judiciary Committee (the "Committee Report")327 confirms that these sections are driven by concerns over cohesiveness. In particular, the Committee Report notes a goal of ensuring that "similarly injured people" are grouped in a single class action. The alleged purpose is to prevent "uninjured class members" receiving money that could go to those with actual injuries, in order to create "classes in which those who are most injured receive the most compensation."328 The Committee Report cites Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes as the source of the principle, particularly the Supreme Court's statement that "a class representative must be part of the class and possess the same interest and suffer the same injury as the class members."329 With respect to proposed Section 1720, the Committee Report suggests that the purpose of this provision is to codify the approach to issue classes announced by the Fifth Circuit in Castano v. American Tobacco Co., discussed above, that a "district court cannot manufacture predominance" by segregating the issues it wishes to certify into a separate predominance inquiry—rather, the court must evaluate predominance for the cause of action as a whole.330

Critics of FICALA, including those cited in the Committee Report, have argued that far from protecting absent class members, these provisions would simply lead to fewer individuals being able to obtain relief through class litigation. As these critics point out, the term "scope of injury" in proposed Section 1716 is undefined.331 Furthermore, these critics argue that at the early stage of litigation when class certification is supposed to occur, the exact "scope" of an injury cannot be measured with any precision, and the proposed section would effectively require "a decision on the merits before trial and before appropriate class members can even be identified."332 Because of this structure, FICALA critics argue that uninjured class members, or class members with different injuries, are an inevitable component of class actions, as membership in a class has never equated to an "entitlement to damages."333 Further, the critics argue that proposed Section 1720 would particularly threaten certain types of civil rights class actions, which can be maintained only as to particular issues such as liability because, as demonstrated in cases like Wal-mart v. Dukes,334 individualized questions tend to predominate in such suits.335

In some ways, the arguments above echo larger disputes. On the one hand, a relatively broader view of cohesiveness enables courts to provide resolutions for injured class members where they might not otherwise exist. For example, in Nassau County Strip Search Cases, the Second Circuit approved class treatment in a case involving an allegedly unconstitutional blanket strip search policy for Nassau County misdemeanor detainees.336 By approving class action treatment on the issues of whether the defendants had implemented the policy and whether they were liable for it, the court sidelined the individualized questions relating to whether some class members might have been appropriately searched.337 Nassau County serves as an example of a case where few of the class members would have had an incentive to seek redress individually for injury they had sustained—in this case, an allegedly unlawful strip search.338 As such, supporters of relaxation of cohesiveness would likely argue that Nassau County is indicative of why it is necessary to permit otherwise noncohesive classes to proceed and why the change proposed by Section 1717 to issue classes would harm plaintiffs.

On the other hand, some commentators have argued that resolving the rights of absent class members without a strong element of cohesion threatens the constitutional values of individual rights and separation of powers.339 According to these commentators, individual rights are threatened because noncohesive class actions undermine an individual's right to a "day in court."340 Where large classes resolve questions on behalf of absent class members on the basis of an opt-out system, absent class members may be deprived of the individual autonomy rights and the right to control their own cases, a problem that is less severe when classes are highly cohesive.341 Further, these commentators argue that separation of powers is undermined because the proper role of the courts is to resolve claims that are in front of them—it is the role of legislatures to devise solutions to generalized problems affecting large swaths of society.342 Where a class action is certified and the class members are not truly cohesive, especially where the damages are small and class members are unlikely to receive a meaningful benefit, courts, in the view of these commentators, act more like legislatures or administrative agencies by disciplining corporations and handing out bounties to class counsel, rather than by redressing individual rights and handing out relief to injured persons.343

Codifying the Ascertainability Doctrine

The circuit split over ascertainability discussed above344 has likewise captured the attention of policymakers. FICALA would add Section 1718 to Title 28 of the U.S. Code, which would forbid a federal court from granting certification of a class action without determining that there is "a reliable and administratively feasible mechanism" for determining whether putative class members fall within the class definition and for determining how to distribute to a substantial majority of class members any monetary relief secured.345 This new provision would codify the approach currently in use within the Third and Eleventh Circuits discussed above.346

To support this provision, the FICALA's Committee Report majority favorably cites a dissenting opinion by Judge Kayatta in the First Circuit, stating that district courts should have to "identify a culling method to ensure that the class, by judgment, includes only members who were actually injured."347 In response, the dissenting Members who signed the "Dissenting Views" portion of the Committee Report argue that the ascertainability requirement has been "rejected by most courts for good reason."348 The dissenters argue that the practical effect would be that many small claim consumer class actions would allow defendants to escape liability because the class is not ascertainable by this standard.349

These statements echo the debate in the federal courts on ascertainability.350 "Defendants in class actions" have "invok[ed] the ascertainability requirement with increasing frequency" in recent years "in order to defeat class certification."351 Some commentators have therefore called the ascertainability doctrine "one of the most contentious issues in class action litigation these days."352 Supporters of a rigorous ascertainability requirement—such as that adopted by the Third and Eleventh Circuits—maintain that requiring the proposed class representative to demonstrate an administratively feasible mechanism for determining whether putative class members fall within the class definition "serves several important policy objectives," such as

- eliminating administrative burdens "by insisting on the easy identification of class members";

- "protect[ing] absent class members by facilitating" notice to the class; and

- "protect[ing] defendants by ensuring that those persons who will be bound by the final judgment are clearly identifiable."353