Overtime Exemptions in the Fair Labor Standards Act for Executive, Administrative, and Professional Employees

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is the primary federal statute providing labor standards for most, but not all, private and public sector employees. The FLSA standards require that “non-exempt” employees working excess hours in a workweek receive pay at the rate of one-and-a-half times their regular rate for hours worked over 40 hours. The requirements in the FLSA for overtime pay beyond this threshold refer to the “maximum hours,” but the FLSA does not actually limit the number of hours that may be worked. Instead, it establishes standards for the pay required for hours beyond 40 hours in a workweek. The FLSA also provides several exemptions to the maximum hours requirement, some of the largest of which are the EAP (executive, administrative, and professional employees, or “white collar”) exemptions. In effect, these exempt employers from overtime pay requirements for certain employees. The FLSA authorizes the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to “define and delimit” the EAP exemptions, rather than setting the specific parameters of the exemptions in the law itself. Since defining and delimiting the EAP exemptions upon the enactment of the FLSA in 1938, DOL has adjusted their parameters eight additional times, most recently in a 2016 rule. In August 2017, a U.S. District Court invalidated the 2016 rule and DOL has subsequently indicated that it is in the process of formulating a new proposal on the EAP exemptions.

As will be discussed in detail in the remainder of this report, the major features of DOL’s rulemaking on the EAP exemptions are as follows:

In every rulemaking since 1938, DOL has required that EAP employees meet three tests to qualify for exemption from overtime pay (i.e., when employees are exempt, employers are not required to pay them for work in excess of 40 hours): (1) exempt employees must perform certain EAP duties (“duties” test), (2) exempt employees must be salaried (“salary basis” test), and (3) exempt employees must earn a salary in excess of the level set by DOL (“salary level” test).

From 1949 to 2004, DOL used a “long” duties test paired with a relatively lower salary level along with a “short” duties test paired with a relatively higher salary level to determine exemption for EAP employees. The main difference between the long and short duties tests was a quantitative limit in the long test on the amount of time an EAP employee could spend performing nonexempt work (no more than 20% in a workweek). During this 55-year period of using long and short tests, the salary level for the short test averaged 149% of the salary for the long test. The logic of using the two approaches was that higher-salaried employees were more likely to meet all requirements for exemption, while lower-salaried employees needed a more-stringent duties test to qualify for exemption.

In the 2004 rulemaking, DOL switched from the long and short tests to a standard duties test and salary level test for exemption. The standard duties test did not include a quantitative limit on the percentage of time performing nonexempt work, making it closer in nature to the defunct short duties test. In addition, the new standard salary level test was lower than the inflation-adjusted salary levels used in the previous short tests. In other words, the 2004 rule generally paired a short duties test with a salary level below the short test levels used in the past.

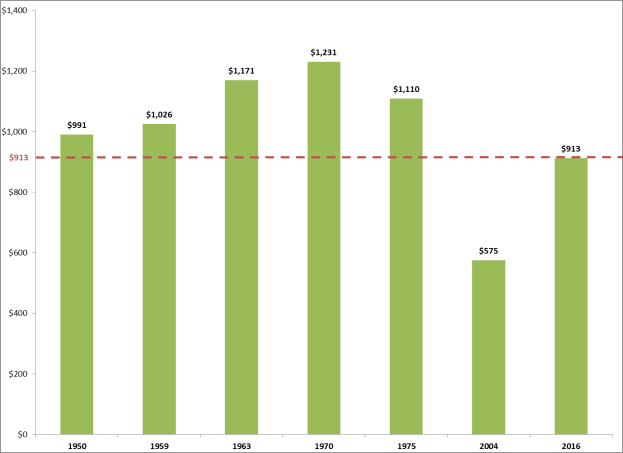

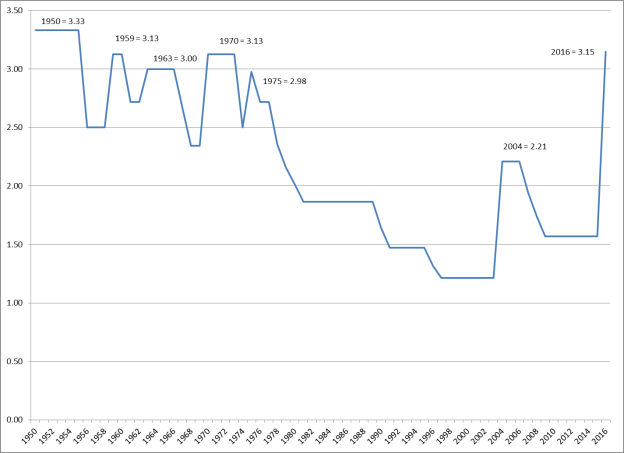

The 2016 rule, which was subsequently invalidated, increased the standard salary level and left the standard duties test unchanged. Compared to the six previous rulemakings using the short and/or standard tests for exemption, the salary level in the 2016 rule ($913 per week) is below the inflation-adjusted levels in all but the 2004 rule. In addition, the ratio of the salary level test to the weekly minimum wage equivalent (40 hours per week at the prevailing minimum wage) in the 2016 rule is 3.15. The average ratio at the time of enactment of each new EAP salary threshold from 1949 through 2016 is 2.99, with a high of 3.33 (1949) and a low of 2.21 (2004).

Since 1938, measures of the salary level have fluctuated according to DOL’s identification of data sources most suitable for studying wage distributions and the department’s determinations of the proportion and types of workers who should be below salary thresholds, as well as its determinations of whether regional, industry, or cost-of-living considerations should be factored into salary tests.

Overtime Exemptions in the Fair Labor Standards Act for Executive, Administrative, and Professional Employees

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Recent Developments

- Goals and Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

- Economic Context at the Time of the FLSA Enactment

- EAP Provisions in the FLSA

- Discretion of the Secretary of Labor to Define and Delimit

- The EAP Exemption Tests

- The Duties Test

- The Salary Level Test

- Comparison of EAP Salary Levels

Figures

Tables

Summary

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is the primary federal statute providing labor standards for most, but not all, private and public sector employees. The FLSA standards require that "non-exempt" employees working excess hours in a workweek receive pay at the rate of one-and-a-half times their regular rate for hours worked over 40 hours. The requirements in the FLSA for overtime pay beyond this threshold refer to the "maximum hours," but the FLSA does not actually limit the number of hours that may be worked. Instead, it establishes standards for the pay required for hours beyond 40 hours in a workweek. The FLSA also provides several exemptions to the maximum hours requirement, some of the largest of which are the EAP (executive, administrative, and professional employees, or "white collar") exemptions. In effect, these exempt employers from overtime pay requirements for certain employees. The FLSA authorizes the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to "define and delimit" the EAP exemptions, rather than setting the specific parameters of the exemptions in the law itself. Since defining and delimiting the EAP exemptions upon the enactment of the FLSA in 1938, DOL has adjusted their parameters eight additional times, most recently in a 2016 rule. In August 2017, a U.S. District Court invalidated the 2016 rule and DOL has subsequently indicated that it is in the process of formulating a new proposal on the EAP exemptions.

As will be discussed in detail in the remainder of this report, the major features of DOL's rulemaking on the EAP exemptions are as follows:

- In every rulemaking since 1938, DOL has required that EAP employees meet three tests to qualify for exemption from overtime pay (i.e., when employees are exempt, employers are not required to pay them for work in excess of 40 hours): (1) exempt employees must perform certain EAP duties ("duties" test), (2) exempt employees must be salaried ("salary basis" test), and (3) exempt employees must earn a salary in excess of the level set by DOL ("salary level" test).

- From 1949 to 2004, DOL used a "long" duties test paired with a relatively lower salary level along with a "short" duties test paired with a relatively higher salary level to determine exemption for EAP employees. The main difference between the long and short duties tests was a quantitative limit in the long test on the amount of time an EAP employee could spend performing nonexempt work (no more than 20% in a workweek). During this 55-year period of using long and short tests, the salary level for the short test averaged 149% of the salary for the long test. The logic of using the two approaches was that higher-salaried employees were more likely to meet all requirements for exemption, while lower-salaried employees needed a more-stringent duties test to qualify for exemption.

- In the 2004 rulemaking, DOL switched from the long and short tests to a standard duties test and salary level test for exemption. The standard duties test did not include a quantitative limit on the percentage of time performing nonexempt work, making it closer in nature to the defunct short duties test. In addition, the new standard salary level test was lower than the inflation-adjusted salary levels used in the previous short tests. In other words, the 2004 rule generally paired a short duties test with a salary level below the short test levels used in the past.

- The 2016 rule, which was subsequently invalidated, increased the standard salary level and left the standard duties test unchanged. Compared to the six previous rulemakings using the short and/or standard tests for exemption, the salary level in the 2016 rule ($913 per week) is below the inflation-adjusted levels in all but the 2004 rule. In addition, the ratio of the salary level test to the weekly minimum wage equivalent (40 hours per week at the prevailing minimum wage) in the 2016 rule is 3.15. The average ratio at the time of enactment of each new EAP salary threshold from 1949 through 2016 is 2.99, with a high of 3.33 (1949) and a low of 2.21 (2004).

- Since 1938, measures of the salary level have fluctuated according to DOL's identification of data sources most suitable for studying wage distributions and the department's determinations of the proportion and types of workers who should be below salary thresholds, as well as its determinations of whether regional, industry, or cost-of-living considerations should be factored into salary tests.

Recent Developments

The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) published an updated rulemaking for the overtime exemptions for executive, administrative, and professional (EAP) employees on May 23, 2016, with an effective date of December 1, 2016. However, on November 22, 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas issued a preliminary injunction blocking the implementation of the rule. In its ruling, the District Court concluded, in part, that DOL does not have the legal authority to use a salary level test as part of defining the EAP exemptions. Subsequently, on December 1, 2016, the Department of Justice (DOJ), on behalf of DOL, filed a notice to appeal the injunction to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. On June 30, 2017, DOJ filed its reply brief in the case and requested that the Court of Appeals reverse the judgment of the district court (related to the legal authority of DOL to use salary level as part of the EAP exemption) but not rule on the validity of the salary level set in the 2016 rule. Finally, on August 31, 2017, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas ruled that DOL exceeded its authority by setting the threshold at the salary level in the 2016 rule and thus invalidated the 2016 rule. Subsequently, DOJ dropped its June 30 appeal of the original district court ruling.1

DOL issued a request for information (RFI) related to the EAP exemptions on July 25, 2017.2 Specifically, DOL's RFI seeks information from the public regarding the EAP exemptions to assist in formulating a proposal to revise them.

Goals and Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is the primary federal statute providing labor standards for most, but not all, private and public sector employees. Its major provisions include a federal minimum wage, overtime pay requirements, child labor protections, and recordkeeping requirements.3 The FLSA also created the Wage and Hour Division (WHD) within DOL to administer and enforce the act.

The FLSA was enacted in 1938 and has been amended numerous times, primarily for the purposes of expanding coverage or increasing the federal minimum wage rate. In enacting the FLSA, Congress noted the "existence, in industries engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, of labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standard of living necessary for health, efficiency, and general well-being of workers."4 As such, the FLSA was intended to "correct and as rapidly as practicable to eliminate" these detrimental conditions "without substantially curtailing employment or earning power."5 The correction of detrimental conditions was to be achieved through the establishment of a federal minimum wage, overtime pay requirements, and child labor protections.

The FLSA applies to employees who have an "employment relationship" with an employer. That is, the FLSA covers most workers but does not include individuals not considered employees (e.g., independent contractors). FLSA provisions are extended to individuals under two types of coverage—"enterprise coverage" and "individual coverage." An individual is covered if they meet the criteria for either category.6 Around 132 million workers, or 83% of the labor force, are currently covered by the FLSA.7

It is important to note that while the FLSA sets standards for minimum wages, overtime pay, and child labor, it does not regulate many other employment practices. For example, the FLSA does not require certain practices or benefits often associated with an employment relationship, such as paid time off, premium pay for weekend work, or fringe benefits. In addition, the FLSA does not limit the number of hours an employee may be required to work in a day or a week. Rather, it requires that a covered employee be compensated with premium pay for overtime hours worked.

Section 7(a) of the FLSA specifies requirements for overtime pay for weekly hours worked in excess of the maximum hours. In general, unless an employee is specifically exempted in the FLSA, he or she is considered to be a covered nonexempt employee and must receive pay at the rate of one-and-a-half times ("time-and-a-half") the regular rate for any hours worked in excess of 40 hours in a workweek. Employers may choose to pay more than time-and-a-half for overtime or to pay overtime to employees who are exempt from overtime pay requirements under the FLSA.

Although coverage is generally widespread, the FLSA exempts certain employers and employees from all or parts of the FLSA. For example, exemptions are provided to EAP employees, individuals employed at retail stores that do not have interstate operations, and agricultural employees. The focus of this report is on the EAP exemptions provided in the FLSA.

Economic Context at the Time of the FLSA Enactment

While the FLSA now extends broad minimum wage, overtime pay, and child labor protections to all individuals "employed by an employer," coverage was not as common when the law was enacted in 1938. Currently, the FLSA covers more than 80% of the labor force.8 Initially, the FLSA did not cover employees in entire sectors, including farm labor, retail trade, domestic and personal service, or public service, nor did it cover the self-employed. At the time of enactment, it was estimated that the FLSA covered about 11 million employees, or roughly one-third of wage and salary earners in the United States.9 The vast majority, or about 9.3 million, of these 11 million employees were in manufacturing, transportation, or mineral industries.10 Later amendments to the FLSA, most notably in 1961 and 1966, increased the scope of coverage so that most employees are now covered by the provisions of the FLSA.11

At the time the FLSA was enacted in 1938, employment was mostly in manual, or "blue-collar," occupations. Even though changes in data collection and occupational and industrial classification make comparing employment composition over time difficult, based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the broad trend in the past 80 years has clearly been toward an increasing share of employment in service occupations, many of which are "white-collar."12 Illustrative of this trend, employment in the "professional, technical, and kindred" occupations increased from less than 5% in 1910 to nearly 25% by 2000.13 More broadly, in their analysis of the 11 major occupation groups over time, Wyatt and Hecker find that

Five of the major occupation groups increased as a share of the total, while six declined. All of the ones that declined, except for private household workers, consist of occupations that produce, repair, or transport goods and are concentrated in the agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, and transportation industries. The five that increased are the so-called white-collar occupations, plus service workers, except private household. The four major groups that are white-collar occupations include mostly occupations having to do with information, ideas, or people (many in the service group also work with people); are more concentrated in services-producing industries; and, at least for professional and managerial occupations, have higher-than-average education requirements. In aggregate, the five groups that increased [white-collar occupations] went from 24 percent to 75 percent of total employment, while the six groups that declined went from 76 percent to 25 percent over the 90-year period [1910-2000].14

Putting the original estimates of FLSA coverage together with the changing occupational composition of the workforce since the FLSA was enacted indicates a workforce that is vastly different now than it was in 1938. While white-collar occupations are not a perfect proxy for those covered by the EAP exemptions in the FLSA (as will be discussed below), the increase of white-collar occupations and the decrease of blue-collar occupations since 1938 has implications for the EAP exemptions. This is discussed in more detail in subsequent sections of this report, but, in essence, an exemption enacted in 1938 that was designed to cover a portion (i.e., executive, administrative, and professional employees) of a minority of the workforce (white-collar occupations) is now relevant for a considerably higher share of the workforce.

EAP Provisions in the FLSA

Section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA states, in part, that the minimum wage (Section 6) and overtime (Section 7) provisions of the act "shall not apply with respect" to

any employee employed in a bona fide executive, administrative, or professional capacity (including any employee employed in the capacity of academic administrative personnel or teacher in elementary or secondary schools), or in the capacity of outside salesman (as such terms are defined and delimited from time to time by regulations of the Secretary. (Italics added.)

Rather than define the terms "executive," "administrative," or "professional," the FLSA authorizes the Secretary of Labor to define and delimit these terms "from time to time" through regulations.15

The legislative history of the EAP exemptions does not provide much information on their intended scope.16 Although not necessarily elaborated upon at the time of enactment, the general rationale for including the EAP exemptions in the FLSA is often construed to be related to the type of work and the presumed labor market power of EAP employees: (1) the nature of the work performed by EAP employees seemed to make standardization difficult, and thus the output of EAP employees was not as clearly associated with hours of work per day as the output for typical nonexempt work (e.g., manual labor); and (2) bona fide EAP employees were considered to have other forms of compensation (e.g., above-average benefits, greater opportunities for advancement, greater job security, greater mobility) not available to nonexempt workers.17 Thus, the compensating advantages of being an EAP employee in 1938 (a small portion of the workforce) could have been seen as a tradeoff for being exempt from the overtime protections of the FLSA.

Discretion of the Secretary of Labor to Define and Delimit

Despite a lack of detailed legislative history on the intent of the scope of the EAP exemptions, two aspects of Section 13(a)(1) are notable in terms of the implied discretion given to the Secretary of Labor to define and delimit the exemptions for executive, administrative, and professional employees.

First, the term "bona fide" was included as part of the EAP exemptions presumably to distinguish it from a general exemption for white-collar workers or even from the subset of all executive, administrative, or professional employees.18 More generally, of the 10 exemptions delineated in Section 13(a) of the originally enacted FLSA, only the exemptions in Section 13(a)(1) included the qualifier "in a bona fide ... capacity" for the class of employees to which the exclusion applies. The other exemptions in Section 13(a) were either specifically delineated or broadly defined. For example, Section 13(a)(8) provided an exemption from minimum wage and overtime provisions to "any employee employed in connection with the publication of any weekly or semiweekly newspaper with a circulation of less than three thousand the major part of which circulation is within the county where printed and published," while Section 13(a)(6) exempted from the minimum wage and overtime provisions "any employee employed in agriculture."

Second, the statutory language of the FLSA directing the administrator of the WHD to define and delimit the EAP exemptions was nearly singular in the exemptions delineated in Section 13 and implies broad discretionary authority. That is, while almost all legislation involves some degree of interpretation on the part of the implementing agency, the authority given to DOL in the Section 13(a)(1) exemptions ("as defined and delimited by regulations of the Administrator") is notable for its explicitness. Of the 10 exemptions delineated in Section 13(a) of the originally enacted FLSA, the only other one that included an explicit requirement for DOL to define a term is Section 13(a)(10), which provided a minimum wage and overtime exemption to "any individual employed within the area of production (as defined by the Administrator), engaged in handling, packing, storing, ginning, compressing, pasteurizing, drying, preparing in their raw or natural state, or canning of agricultural or horticultural commodities for market, or in making cheese or butter or other dairy products." However, even the authority granted to the WHD administrator in Section 13(a)(10) was limited to defining an "area of production," rather than allowing for an exemption for an entire segment of the labor force as the authority granted in Section 13(a)(1) did.

In summary, the Section 13(a)(1) exemptions stand out from the other Section 13(a) exemptions included in the original FLSA because of a qualifying condition ("bona fide") for the type of employee to be exempt and the authority given to DOL to operationalize the exemptions for bona fide EAP employees. The only guidance that the statute provided was that some executive, administrative, and professional employees, but not all, should be exempt from the minimum wage and overtime provisions of the FLSA. From the time of the first rulemaking around the EAP exemptions, DOL recognized the breadth of its authority in regulating the exemptions. For example, in the hearings conducted to make recommendations for the 1940 rule, the Presiding Officer noted that Congress's use of the "word 'delimited' as well as the word 'defined' is a further indication of the extent of the [WHD] Administrator's discretionary power under this section of the act" and that the administrator "is responsible not only for determining which employees are entitled to the exemption, but also for drawing the line beyond which the exemption is not applicable."19 Thus, the lack of statutory specificity for these exemptions and the delegation of authority to DOL to set their parameters has led to the use of a broadly similar methodology, but different and changing data and units of analysis, to set the salary level threshold in the almost 80 years since the FLSA was enacted. Although Congress has amended the FLSA multiple times since 1938, the statutory language creating the Section 13(a)(1) exemptions has remained largely unchanged and the operational EAP exemptions are changed, or not changed, depending on the priorities of a given administration.

The EAP Exemption Tests

Although the determinations established through rulemaking have changed over time, to qualify for an exemption under Section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA, a current employee generally has to meet all of the following criteria:

- 1. An employee must be paid a predetermined and fixed salary (the "salary basis" test).20

- 2. An employee must perform executive, administrative, or professional duties (the "duties" test).21

- 3. An employee must be paid above the threshold established in the rulemaking process, typically expressed as a per week rate (the "salary level" test).22

These three tests were established through rulemaking starting in 1938.23 While the salary basis test (i.e., the requirement that an exempt employee is paid a fixed salary and not hourly) has remained constant throughout the EAP rulemakings, the duties tests and, particularly, the salary level tests have evolved. These two tests have worked in conjunction as screens for exemption. The main themes in the evolution of the duties and salary level tests are discussed in the sections below. The Appendix includes more detailed descriptions of the salary level methodologies used in each of the eight EAP rules from 1940-2016.

The Duties Test

Since its first rulemaking on the EAP exemptions, DOL has defined this part of the test in terms of "duties" actually performed rather than occupational titles. In recommending to DOL that duties-based (rather than occupation- or title-based) criteria for exemption be maintained in the 1940 rulemaking, the Presiding Officer at the DOL hearings noted that the

final and most effective check on the validity of the claim for exemption is the payment of a salary commensurate with the importance supposedly accorded the duties in question. Furthermore, a title alone is of little or no assistance in determining the true importance of an employee to the employer. Titles can be had cheaply and are of no determinative value.24

This interpretation—consideration of actual duties performed rather than occupational titles—has been maintained in all subsequent regulations on the EAP exemptions.

The duties tests for EAP exemptions have evolved in roughly three phases:

- Long Tests (1938-1949). Following enactment of the FLSA in 1938, DOL issued regulations defining required duties for exemption for two categories of employees—"executive and administrative" and "professional"—and required salary thresholds for exemption for each of these two categories. The 1940 rule split the first category into two—executive and administrative—thus creating the three distinct exempt EAP categories that remain in use today. These first two rules (1938 and 1940) established a series of tests that described the duties employees must perform in order to satisfy the duties test for EAP exemption from overtime. These duties tests, which became known as the "long" tests, were paired with corresponding salary levels to form the exemption tests.

- Long and Short Tests (1950-2003). Starting with the 1949 rule (effective in 1950), DOL created a second set of duties tests, which became known as the "short" test, to be used concurrently with the existing "long" duties tests. These two tests, and two separate corresponding salary levels, remained in place until the 2004 rule.

- The long tests combined relatively lower salary thresholds with a duties test that included quantitative limits on the percentage of work time an exempt employee could spend on nonexempt work. Specifically, to qualify under the long test (and thus the lower salary threshold), an EAP-exempt employee could spend no more than 20% of work hours in a workweek on nonexempt work activities (i.e., work not closely related to the duties of a bona fide administrative, executive, or professional employee).

- The short duties test developed in the 1949 rule was less stringent and combined a higher salary threshold with a shorter duties test that did not include a quantitative limit on nonexempt work. Instead, the short test required that an exempt employee must have as a "primary duty" those of a bona fide executive, administrative, or professional employee. The "primary duty" means the principal, main, or major duty and is not strictly defined in terms of time spent on particular activities.25 For example, assistant managers at retail establishments who supervise and direct other employees (exempt work) might have management as their primary duty even if they spend more than half of their time running a cash register (nonexempt work).

- Standard Tests (2004-present). The 2004 rule eliminated the long and short tests for EAP exemption and created a single "standard" duties test and a single salary level. The 2016 rule maintains the standard duties test for EAP exemption. The standard tests do not include a time limit on the performance of nonexempt work by exempt employees and are substantively similar to the defunct short tests.

Table 1 provides a comparison of the elements of the duties tests used for EAP exemption over time.

|

Long (1940–2003) |

Short (1949–2003) |

Standard (2004–Present) |

|

|

Executive |

|

|

|

|

Administrative |

|

|

|

|

Professional |

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of 29 C.F.R. §541.

The Salary Level Test

In addition to the salary basis and duties tests, DOL established a salary level in implementing the provisions of Section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA. Since the enactment of the FLSA in 1938, DOL has required that an employee earn above a certain salary in order to qualify for the EAP exemption. That is, a bona fide executive, administrative, or professional employee, as determined by duties performed, must also earn at least a certain amount in weekly (or less frequent) salary to be exempt from entitlement to overtime pay.

Throughout the history of defining and delimiting the EAP exemption, DOL has frequently asserted that the salary paid to an EAP employee is the "best single test" of exempt status.26 In the 1949 rule, for example, DOL concluded that the salary level test added a "completely objective and precise measure" that served as an "aid in drawing the line between exempt and nonexempt employees."27 That said, setting the salary level threshold for exemption requires judgments about the appropriate line between exempt and nonexempt employees and, as demonstrated by the eight final rules since 1938, reflect the priorities and methods of the administrations regulating the exemptions.

Since the FLSA was enacted, the salary level threshold has been raised eight times, including the 2016 increase (see Table 2). Increases have occurred through intermittent rulemaking by the Secretary of Labor, with periods between adjustments ranging from 2 years (1938–1940) to 29 years (1975–2004). From the first adjustment to the salary threshold in 1940 until the sixth adjustment in 1975, DOL issued rules periodically, in intervals ranging from 2 to 9 years. The two rules after 1975, however, were issued 29 and 12 years, respectively, after the previous rules.

|

Enactment |

Executive (Long) |

Administrative (Long) |

Professional (Long) |

All EAP (Short) |

Implementation Period |

|

1938 |

$30 |

$30 |

— |

— |

|

|

1940 |

$30 |

$50 |

$50 |

— |

9 days |

|

1949 |

$55 |

$75 |

$75 |

$100 |

32 days |

|

1958 |

$80 |

$95 |

$95 |

$125 |

76 days |

|

1963 |

$100 |

$100 |

$115 |

$150 |

31 days |

|

1970 |

$125 |

$125 |

$140 |

$200 |

30 days |

|

1975 |

$155 |

$155 |

$170 |

$250 |

41 days |

|

Standard Test for EAP |

|||||

|

2004 |

$455 |

122 days |

|||

|

2016 |

$913 |

192 days |

|||

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, "Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees," 81 Federal Register 32401, May 23, 2016; and CRS analysis of Federal Register, various years.

Note: Implementation Period is the number of days between publication of the EAP rulemaking in the Federal Register and the effective date of the updated salary levels.

As noted above, DOL added the new short test to the already existing long test, creating a two-test system of exemption. From 1949 until 2004, the long duties test was accompanied by a lower salary threshold and the short test was accompanied by a higher salary threshold. Importantly, as will be discussed below, DOL determined the EAP salary level thresholds for the long test first, and the short test salary level was typically set as percentage of the long test salary levels. In the period when two tests existed (1949-2004), short test salary levels as a percentage of long test levels ranged from 182% (1949) to 130% (1963), with an average of 149%.28 Finally, the 2004 final rule combined the tests into a single standard duties test and one salary threshold, and the 2016 rule maintains the standard duties test and single salary level (though it raised this level).

The methodologies that DOL used in the eight revisions to the EAP salary level since 1938 have differed in specifics but generally may be categorized into three periods based on the approaches used to define and delimit the EAP exemptions: the 1940 and 1949 rules; the 1958, 1963, 1970, and 1975 rules; and the 2004 and 2016 rules.29 The history of establishing salary level thresholds shows that while DOL has wide discretion in the operationalization of the statutory EAP exemptions, path dependence also plays in important role, as administrations generally incorporated parts of methodologies from previous rules into the current rule. In particular, once the concept of income-based proportionality was introduced in the 1958 rule, future rules incorporated it, albeit in distinctly different ways.

Income-Based Proportionality: Choosing a Wage Distribution

A fundamental question, if not the fundamental question, facing DOL since it was authorized to define and delimit the EAP exemption has been where and how to draw the line between nonexempt employees (entitled to overtime pay) and exempt employees (not entitled to overtime pay). Each of the tests—salary basis, duties, and salary level—can be adjusted to make the exemption narrower or broader. For example, a broad exemption might include salaried and hourly employees, a duties test based on occupational titles, and a low salary threshold. On the other hand, a narrow exemption might include only salaried employees, a detailed duties test, and a high salary threshold. Under the broad exemption, many employees would qualify and therefore not be entitled to overtime pay, while under the narrow exemption, fewer would qualify and therefore more employees would be entitled to overtime pay. Because the salary basis has remained unchanged and duties tests have remained largely similar since the 1940s (with some exceptions in 1949 and 2004), the salary level test has provided much of the demarcation function. The level at which the salary threshold is drawn thus plays a decisive role in determining the scope of the EAP exemptions.

The 2016 final rule notes that the regulatory history of the salary level test "reveals a common methodology used, with some variations" such that "in almost every case, the Department examined a broad set of data on actual wages paid to salaried employees and then set the long test salary level at an amount slightly lower than might be indicated by the data."30 The policy choices and emphases of the administration regulating the exemptions drive the variations embedded in the broadly common methodology. In evaluating the salary level thresholds, it is important to note that proposals to update them for "inflation" (whether a price or wage index) from a given point in time are not simply technical adjustments. Rather, as will be shown in the summary of the various rulemaking methodologies below, proposals to update the salary level thresholds from a given point in time through the use of an inflation measure essentially lock in prior methodological and data choices that were used in determining a particular salary level threshold in the past.

The 1940 and 1949 Rules

The first two rules after enactment of the FLSA—1940 and 1949—used multiple sources of data and reference points to amend the salary thresholds. These included the salary threshold's distance from the prevailing federal minimum wage,31 the various state salary level thresholds for EAP exemptions in statute at the time, differences between "prevailing minimum salaries" for exempt personnel and average salaries for nonexempt personnel, government pay scales for administrative and professional employees, and data on average salaries in selected nonexempt occupations (e.g., office boys, hand-bookkeepers, clerks, workers in the full-fashioned hosiery industry). The range of sources used reflected in part the data available at the time, but it also illustrates the difficulty in comparing methodologies over time. For example, the 1949 rule relied heavily on the change from 1940 to 1949 in average weekly earnings for employees in manufacturing industries (not occupations) to determine the increase in the salary threshold for executive employees in 1949, which was increased from $30 to $55 per week. Given the data limitations, this method of basing a threshold increase for an exempt occupation on average wage increases for nonexempt employees in an industry may have been reasonable at the time. However, once the new threshold was set at $55 in 1949, it provided a baseline (i.e., a dollar threshold) upon which future increases, using different sources of data, were established, thus locking in parts of previous methodologies.

Although a specific percentile in a wage distribution (e.g., the 20th percentile of wages for exempt occupations) was not used to establish the salary level for the EAP exemptions, both the 1940 and 1949 rules emphasized placing the thresholds "somewhere near the lower end of the range of prevailing salaries for these employees."32 Using the lower end of the range of prevailing salaries of EAP employees was based on DOL's goal of not denying bona fide EAP employees (based on an examination of the long test duties) the exemption. In addition, DOL rejected the use of regional or industry-based thresholds and indicated that a lower threshold would serve that goal by not excluding bona fide EAP employees in lower wage industries and regions of the country.33 Finally, it should be noted that these early decisions in setting the EAP salary levels for exemption—using the lower end of the salary range, using multiple criteria and data, and recognizing that using a single threshold should not deny the exemption to bona fide employees in low-wage industries and regions—took place in the context of a more robust "long" duties test.34

The 1958, 1963, 1970, and 1975 Rules

The rulemakings in 1958, 1963, and 1970 (and implicitly the 1975 rule because it updated existing salary levels by the Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers, or CPI-U) used the general approach of reviewing salary levels of exempt EAP employees and analyzing the minimum salaries they were paid compared to higher salaries of nonexempt employees. A central policy choice in rulemaking on the EAP exemptions has been, and continues to be, how to set the salary threshold at a level such that only a small percentage of bona fide EAP employees are denied the exemption, while also ensuring that an adequate differentiation exists between the salary of a nonexempt worker and the exempt worker supervising that nonexempt worker.

The 1958 rule, however, was the first to introduce a specific percentile to define income-based proportionality. That is, while the pre-1958 rules noted the importance of setting the salary level threshold at the lower end of the salary range for EAP employees and of considering regional, firm-size, and industry differentials in wage levels, the 1958 rule operationalized the salary threshold with an explicit target of setting the thresholds at levels "at which no more than about 10 percent of those in the lowest-wage region, or in the smallest size establishment group, or in the smallest-sized city group, or in the lowest-wage industry of each of the categories would fail to meet the tests." Thus, the 1958 rule, also known as the "Kantor method" after the DOL administrator who developed it, established the principle that the salary threshold would not disqualify more than 10% of exempt EAP employees (as determined through passing the long duties test) in any of four categories: region, establishment size, city, or industry. All subsequent rules have used a specific percentile on a wage distribution to establish the threshold for exemption from overtime pay.

It is important to note that the 10% principle established in 1958 and used in the three subsequent rulemakings on the EAP exemptions (1963, 1970, and 1975) was possible because of wage distribution data available from the Wage and Hour and Public Contracts (WHPC) division of DOL, a data source not available for the 2004 and 2016 rules.35 The WHPC reports typically included data on EAP-exempt employee salaries by geographic regions, establishment size, city size, and industry group. In addition, the reports included earnings data on the highest paid nonexempt employees who were being supervised by the lowest paid exempt executive employee in each establishment. The WHPC collected data on actual salaries paid to EAP employees as part of its investigations on compliance with the FLSA and the EAP exemptions.36 That is, as was noted by DOL in 1969, in the WHPC data "establishments selected for investigation by the WHPC are for the most part those in which there is a reason to believe that a violation [of the FLSA] exists." DOL noted that that a "large proportion of these establishments tend to be in the South and in nonmetropolitan areas."37

Thus, establishing the salary threshold for the EAP exemptions in this period primarily started with a wage distribution consisting of salaries of actually exempt EAP employees (based on the long duties test) in firms investigated by DOL. Even within this common wage distribution, however, the operationalization seems to have varied in at least two ways:

- The unit of analysis varied between the establishment and the employee. For example, in increasing the salary level threshold for executive exemption from $80 to $100 per week in the 1963 rule, DOL noted that 13% of the establishments in the survey paid one or more of their executive employees less than $100 per week.38 Yet, in increasing the salary level threshold for executive exemption from $100 to $125 per week in the 1970 rule, DOL noted that 20% of executive employees determined to be exempt based on the long duties test earned less than $130 per week.39

- The Kantor method established the principle that the salary level threshold for EAP exemption should disqualify no more than 10% of EAP employees from exemption in four categories: region, establishment size, city, or industry. In practice, however, this was difficult to achieve. For example, the 1970 rule increased the salary threshold from $100 to $125 per week, a level which about 11% of all administrative employees' earnings were below. Yet, 18% of administrative employees in the South, 10% in the small-firm size category (0-9 employees), 16% in nonmetropolitan areas, and 16% in the retail industry earned below the $125 per week threshold. Unless there was convergence of salaries for EAP employees across all four categories, the Kantor method would be difficult to operationalize.

The 2004 and 2016 Rules

The 2004 and 2016 rules maintained the concept of proportionality but the operationalization of this concept was different from past demarcations, mostly due to the changing nature of available data, making comparisons across time difficult. Specifically, the 2004 rule on the EAP exemptions eliminated the long and short duties tests in favor of a single, standard duties test (the 2016 rule kept the standard test) and used a wage distribution from a data source that included exempt and nonexempt employees to set the salary level threshold for exemption.

In setting the standard salary level in the 2004 rule, DOL noted its intention to establish the updated level based on the methodology in the 1958 rule (the Kantor method, described above).40 DOL did not have available data on actual salaries paid to EAP exempt employees when it was creating the 2004 and 2016 rules (as it did when devising the methodology used in the 1958 rule and the similar methodologies used in setting the salary levels in the rulemakings from 1963 through 1975). Rather, DOL used survey data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) in determining the salary level for the standard test (which replaced the long and short tests).41

In recognition of the fact that the CPS salary data covered both exempt and nonexempt workers and of the creation of a standard duties test (as opposed to two tests with two different salary levels), DOL set the 2004 salary level at a point in the earnings distribution that would exclude from exemption approximately 20% of full-time salaried workers in the South (lowest wage region) and 20% of full-time salaried workers in the retail industry (lower wage industry). Thus, DOL set the salary level at the 20th percentile of all full-time salaried employees (exempt and nonexempt) in the South and the retail industry, rather than at the 10th percentile of exempt employees.42

In setting the standard salary level for exemption in the 2016 final rule, DOL again used CPS data on salaried workers to establish a wage distribution from which the threshold is derived. As with the 2004 rule, DOL established the salary level to exclude from exemption a certain percentage of EAP employees. However, it used different criteria than the 2004 rule and thus established a higher salary level than a methodology comparable to 2004 would have produced, based on the following:

- DOL set the standard salary level equal to the 40th percentile (rather than the 20th percentile) of weekly earnings of full-time salaried (i.e., nonhourly) workers in the lowest-wage Census region, which is currently the South region.43 That is, about 40% of full-time salaried workers in the South region earn at or below $913 per week ($47,476 annually);44

- DOL does not include salaries in the retail industry as a demarcation point for exemption. In rejecting the inclusion of the retail industry salaries in the salary level estimation, DOL noted that the historical parity between low-wage areas and low-wage industries does not exist at the 40th percentile and thus multiple duties tests would have been required to include these two salary levels. Specifically, DOL noted that the salary level at the 40th percentile for the retail industry was below the historical range for the extant short test and would thus not serve as a demarcation in conjunction with the standard duties test;45

- DOL does not exclude from its salary analysis employees who are excluded on a regulatory or statutory basis from FLSA coverage or the salary requirement for overtime exemption.46 In other words, the salary distribution includes employees who would not be subject to either the salary test for overtime exemption (e.g., doctors, lawyers) or those excluded from FLSA coverage.

In establishing the salary level at the 40th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried employees, rather than the 20th percentile used in 2004, DOL argues that the 2004 threshold was too low because of the elimination of the long tests and the adoption of a standard test based on the short duties test.47 That is, the individual long tests for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions prior to 2004 had been accompanied by relatively lower salary thresholds, while the short test had been accompanied by a relatively higher salary threshold. DOL adopted the $913 salary level to "correct the mismatch" between the standard salary level, based on the previous long test levels, and the standard duties test, based on the previous short test.48

Thus, while the 2004 and 2016 rules followed the general methodology used in previous rules of setting a demarcation at a specific point on a wage distribution, the methodologies differ in important ways from previous rules and from each other. Specifically, the 2004 and 2016 rules

- established the salary level threshold on a wage distribution of all salaried employees, rather than on a distribution of exempt employees;

- accounted for some—region and industry in 2004, and region in 2016—but not all of the four-part criteria used in previous rules; and

- used different percentiles—20th (2004) and 40th (2016)—than were used in previous rules.

Comparison of EAP Salary Levels

Data in Figure 1 and Figure 2 compare the 2016 EAP standard salary level to two reference points often used in contextualizing the EAP salary levels—the Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) and the federal minimum wage. The CPI-U, for example, was used to update the EAP salary levels in the 1975 rule and was proposed (but ultimately not adopted) as the automatic updating mechanism in the 2016 rule. The federal minimum wage has been used as a reference point for the EAP salary threshold as early as the 1940 rule, when DOL noted that the assumption that bona fide executive employees earn "compensatory privileges"49 would fail unless those employees earned "substantially higher" than the federal minimum wage.50 Thus, comparing the EAP salary levels over time to price changes (CPI-U) and another federally regulated wage (minimum wage) provides context for the rule changes.

Data in Figure 1 show the 2016 standard salary level of $913 per week compared to the previous inflation-adjusted weekly salary levels used in the short test (1949-1975) and the standard test (2004). Data in Figure 2 compare the standard and short test salary levels and minimum wage historically.

The standard duties and short duties tests have been used to illustrate how EAP salary levels established by DOL have changed over time. These two tests are used as the basis for this comparison here, because, as noted previously, the standard duties test is quite comparable to the short duties test and is thus more appropriate than the salary threshold associated with the long duties test for comparing the value of the salary threshold over time.51 Upon introducing the standard duties test in 2004, DOL acknowledged that differences between the standard and short duties tests were minimal:

Given the lack of data on the duties being performed by specific workers in the Current Population Survey, the Department concludes that it is impossible to quantitatively estimate the number of exempt workers resulting from the deminimis differences in the standard duties tests compared to the current short duties tests.52

Compared to the 2016 salary level of $913 per week, the short test salary level would have been higher in 2016 had the short test's levels been indexed to the CPI-U at the time of enactment in all but the 2004 adjustment. That is, indexing the EAP salary levels to inflation at the point of any of the changes from 1949 through 1975 would have resulted in a 2016 salary level ranging from $991 per week ($78 above the 2016 level) to $1,231 per week ($318 above the 2016 level). On the other hand, if the EAP standard salary level had been indexed to CPI-U from the 2004 adjustment, it would be $575 per week in 2016 ($338 less than the 2016 level). Thus, as derived from the data in Figure 1, the real value of the threshold for the standard test fell from an average of $1,106 in the 1950–1975 period to $575 in 2004 (a decrease of 48%). If the 2016 rule had not been invalidated, the 2016 threshold would have decreased in real terms by 17% from the average of the short test level but increased by 59% in real terms from the 2004 level.

Data in Figure 2 show the ratios of the EAP short test salary level to the federal minimum wage over time. While the federal minimum wage rate is not regulated by DOL (i.e., rate changes are enacted only by amendments to the FLSA), it has traditionally been used explicitly by DOL as a benchmark when establishing the EAP salary thresholds. As noted in the 2004 rule, the legislative history indicates that the EAP exemptions were "premised on the belief that the workers exempted typically earned salaries well above the minimum wage."53 As one of many examples, the 1963 rule noted "[I]n nearly a quarter century of administering the act ... the salary test established for executives ... has fluctuated between 73 and 120 times the statutory hourly minimum wage applicable at the time, the arithmetical mean being 92."54 This comparison then guided DOL's establishment of the salary threshold for executive and administrative employees at 80 times the prevailing the prevailing hourly minimum wage at the time.

To match the EAP salary level formats (weekly), federal hourly minimum wage rates were converted to full-time weekly amounts by multiplying the hourly wage by 40 hours. From 1950 through 1975, the ratios averaged 2.94. This ranged from 3.33 in the first half of the 1950s (when the EAP salary level was $100 per week, and the federal minimum wage was equal to a 40-hour weekly amount of $30) to 2.34 in 1968-1969 (when the EAP salary level was $150 per week, and the federal minimum wage was equal to a 40-hour weekly amount of $64). From 1976 through 2003, a period of time in which no adjustments were made to the EAP salary levels, the ratio of the EAP short test salary level to the federal minimum wage steadily declined, with brief plateaus due to minimum wage increases. The average ratio in the period from 1976 through 2003 was 1.7, bottoming out in the period from 1997-2003 at 1.21 (when the EAP salary level was $250 per week, and the weekly federal minimum wage was $206). Following the 2004 increase in the EAP short test salary level to $455 per week, the ratio increased to 2.21. It then declined to 1.57 following increases in the minimum wage in 2007 through 2009. Finally, the ratio increased to 3.15, with the 2016 EAP short test salary level of $913 per week and a federal minimum wage of $290 (on a weekly basis).

Appendix. History of EAP Salary Level Test Rulemaking

1940 Rule

The Secretary of Labor updated the salary level for the EAP exemptions for the first time in 1940 (following the initial tests established at the time the FLSA became effective in 1938). The Secretary maintained the salary level for executive employees ($30 per week), increased it for administrative employees (from $30 to $50 per week), and added a salary level for a new category, professional employees ($50 per week).55

In setting the salary level in 1940, DOL noted two points about updating it. First, the terminology in the EAP exemptions in the FLSA (Section 13(a)(1)) "implies a status which cannot be attained by those whose pay is close to or below" the prevailing federal minimum wage, which was $0.30 per hour at the time.56 In other words, DOL argued that an EAP salary level too close to the federal minimum wage would not be indicative of an exempt employee as intended by the FLSA. Second, DOL noted that the "bona fide" aspect of the EAP exemptions (i.e., a "bona fide executive, administrative, or professional") was "best shown by the salary paid."57

In leaving the salary level for the executive exemption unchanged from the established level of $30 per week, DOL chose to "retain a comparatively low salary requirement," in part because of the absence "of data to show that the present $30 requirement has proved unsatisfactory."58 DOL reached its conclusion to maintain the $30 level primarily by determining that state overtime EAP exemptions salary thresholds at the time were near $30, considering "compensating advantages" that executives enjoy over nonexempt employees (e.g., authority over workers, opportunities for promotion, paid vacation, job security), and noting that a higher salary level for executives (thus increasing the "penalty" for overtime hours) would not result in "employment spreading" because the nature of executive work is not as shareable as administrative or professional work.59

In increasing the salary level for the administrative exemption from $30 to $50 per week, DOL did not include a limit on nonexempt work for employees in this category. As a result, DOL concluded that "when this valuable guard against abuse [i.e., the limit on the performance of nonexempt work] is removed, it becomes all the more important to establish a salary requirement for the exemption of administrative employees, and to set the figure therein high enough to prevent abuse."60 DOL also noted that if a large percentage of employees in a "highly routinized occupation" are exempted from overtime protection, then the salary level "fails to act as a differentiating factor between the clerical and the administrative employee."61 As such, DOL set the $50 per week salary level primarily on the basis of the federal government's wage schedule at the time for clerical and administrative employees, but also on the basis of data from two occupations in the private sector.62 WHD salary data for stenographers (a "highly routinized occupation") showed that less than 1% of them earned more than $2,400 annually ($200 per month) at the time, meaning that the exemption would only affect those with "truly responsible positions."63 The same WHD salary data showed that only 8% of bookkeepers ("one of the most routine of all the normal business occupations") earned more than $50 per week, but almost 50% of accountants and auditors (a group that "requires in general far more training, discretion, and independent judgement" than bookkeepers) earned at least $50 per week.64

Finally, DOL defined a new category of exempt workers—professional employees. The test for this new group, which like administrative employees did not include a cap on the percentage of time spent on nonexempt work, was set at $200 per month. Given the lack of available data on professional employees at the time, DOL relied primarily on data from the Federal Personnel Classification Board, which determined wage schedules for "professional" and "subprofessional" employees. The average annual salaries were $2,850 for the top grade of subprofessional workers and $2,250 for lowest grade of professional workers, thus making the dividing line about $2,550.65

The 1949 Rule

The next change to the EAP exemptions occurred in 1949. The Secretary increased the salary level for executive employees from $30 to $55 per week, for administrative employees from $50 to $75 per week, and for professional employees from $50 to $75 per week.66 In addition, the 1949 rule established a short test that included a higher salary threshold of $100 per week paired with a shorter test of compliance with EAP duties.

Similar to the 1940 rule, DOL concluded in the 1949 rule that the salary test was a "vital element" in the regulation of the EAP exemptions. Specifically, DOL noted that not using updated salary levels weakens the effectiveness of the salary level as a demarcation between exempt and nonexempt workers, increases misclassification, and complicates enforcement by failing to screen out "obviously nonexempt" employees.67 In considering the increased salary levels for the EAP exemptions, DOL noted that "actual data showing the increases in the prevailing minimum salary levels of bona fide executive, administrative, and professional employees" since the previous threshold was established in 1940 would be the "best evidence" on which to base the new levels. In the absence of data on actual minimum salary levels of bona fide EAP employees, DOL considered changes in wage rates and earnings of nonexempt employees as the "best and most useful evidence" available to establish new salary levels for exemption.68

DOL increased the salary level for executive employees from $30 to $55 per week. It primarily based its decision on the changes in average weekly earnings in the manufacturing industry. That is, average earnings in different parts of the manufacturing industry had increased by more than $25 per week from 1940 to 1949, which implied an increase to at least $55 per week for an executive to qualify for exemption.69 In justifying a new threshold at the lower end of changes in earnings for nonexempt employees, DOL indicated consideration must be given to lagging executive salaries in certain geographic regions, industries, and small establishments.70

DOL increased the salary level for administrative and professional employees from $50 to $75 per week. As with the 1940 rule, DOL relied on wage data for white-collar workers in general (rather than wage data for nonexempt workers that it used to update the threshold for executive employees), with a particular focus on clerical workers (e.g., bookkeepers), accountants, engineers, and federal government workers classified as "professional."71 More generally, DOL indicated that the updated salary level "must exclude the great bulk of nonexempt persons if it is to be effective."72

Finally, DOL added what would become known as the "short test" for EAP exemptions in the 1949 rule and created a two-test system of exemption (including the already established long test) that would remain in place until the 2004 rule. Specifically, DOL created special provisions for "high salaried" EAP employees, such that if an employee earned at least $100 per week and had a "primary duty" as an executive, administrative, or professional, he or she would be exempt from overtime protection.73 In setting the initial short test salary level at $100 per week, DOL noted that with "only minor or insignificant exceptions," employees who earned $100 per week and had as their "primary duty" work characteristic of an executive, administrative, or professional met all the requirements of exemption under the short test as well.74

DOL justified a new, separate short test for duties and salary on the basis of findings that75

- the higher the salaries they were paid, the more likely employees were to meet all requirements for exemption;

- the use of a higher salary threshold with a lower, more qualitative duties test (compared to the percentage cap on nonexempt work in the long test) was intended to provide a "short-cut test of exemption" to ease administration of the EAP exemptions;

- the short test salary level needed to be "considerably higher" than the long test level so that it would include employees about whose exemption status there was normally no question; and

- the new short test was unlikely to lead to "injustice" because a bona fide EAP employee not meeting the higher salary test would still be likely to qualify for exemption under the long test.

The 1958 Rule

The next change to the EAP exemptions occurred in 1958. The Secretary increased the salary level for executive employees from $55 to $80 per week and for administrative and professional employees from $75 to $95 per week.76 In addition, the 1958 rule increased the salary threshold for the short test from $100 to $125 per week.

The 1958 rule, consistent with the previous rulemaking on the EAP exemptions, emphasized the importance of setting the salary levels near the lower end of the salary range for each of the exempt categories, as part of demarcating bona fide EAP employees "without disqualifying [from exemption] any substantial number of such employees."77 Specifically, DOL attempted to establish a salary level for EAP exemptions at which no more than about 10% of EAP employees in the lowest-wage region, smallest-establishment group, smallest-city group, or lowest-wage industry would fail to qualify for exemption.78

To achieve this target of no more 10% of EAP employees failing to qualify for exempt status, DOL proceeded in two main stages. First, it used survey data on the range of salaries actually paid to employees who qualified for the overtime exemptions. DOL then compared the percentage of exempt employees at different salary levels across all four criteria—lowest-wage region, smallest-establishment group, smallest-city group, and lowest-wage industry—to determine the level at about which only 10% of actually exempt EAP employees in each category would not qualify. Because the salary thresholds differ across the four target groups, DOL could not set the level such that exactly 10% of employees in each group would not qualify. For example, DOL noted in the analysis for executive employees accompanying the 1958 rule that for employees found to be exempt, 10% in the lowest-wage region (South) were paid less than $75 per week, 10% in the smallest-establishment group (1-7 employees) were paid less than $75 per week, 9% in the smallest-city group (population of less than 2,500) were paid less than $75 per week, and 6% in the lowest-wage industry group (services) were paid less than $75 per week.79 In the 1958 final rule, DOL set the actual salary level threshold at $80 per week. Second, because the salary survey data were collected in 1955, DOL adjusted the salary levels indicated in the survey data by changes in nonexempt manufacturing worker earnings from 1955-1958.80

DOL adjusted the short test salary level to $125 per week by maintaining the approximate percentage differential established in the 1949 rule between the long test levels for administrative and professional employees and the short test levels for high earners.81

The 1963 Rule

The next change to the EAP exemptions occurred in 1963. The Secretary increased the salary level for executive employees from $80 to $100 per week, for administrative employees from $95 to $100 per week, and for professional employees from $95 to $115 per week.82 In addition, the 1963 rule increased the salary threshold for the short test from $125 to $150 per week.

The 1963 rule used WHD survey data from 1961 on actual salaries paid to EAP exempt employees, which showed that83

- of establishments employing executive employees, 13% paid one or more of these employees less than $100 per week;

- of establishments employing administrative employees, 4% paid one or more of these employees less than $100 per week; and

- of establishments employing professional employees, 12% paid one or more of these employees less than $115 per week.

In setting the updated salary levels, DOL noted that salary thresholds of $100 per week for executive and administrative employees and $115 per week for professional employees would "bear approximately the same relationship" to the salary thresholds established in the previous adjustment in 1958. That is, according to the 1963 rule, at the adoption of the 1958 salary levels, 10% of establishments employing executive employees paid one or more of these employees less than $80 per week and 15% of establishments employing administrative or professional employees paid one or more of these employees less than $95 per week.84 It is important to note here that one of the difficulties in comparing salary level thresholds over time is not only the different methodologies used but also the way the data are reported. The standard used in the 1963 rule—the percentage of establishments with "one or more employees" in a particular earnings category—is different from the 1958 standard, which referred to percentages of individuals in the earning distribution. Yet the 1963 rule characterized the 1958 findings in establishment terms (i.e., percentage of establishments with earners), not in individual terms (i.e., percentage of individuals).

Finally, DOL adjusted the short test salary level to $150 per week (from $125 per week). Neither the proposed nor the final rule elaborated on the rationale for the increased short test salary level, but the increase to $150 per week maintained similar ratios of short-to-long test salary levels for executives (from 156% to 150%) and professionals (from 132% to 130%), while increasing the ratio for administrative employees (from 132% to 150%).

The 1970 Rule

The next change to the EAP exemptions occurred in 1970. The Secretary increased the salary level for executive and administrative employees from $100 to $125 per week and for professional employees from $115 to $140 per week.85 In addition, the 1970 rule increased the salary threshold for the short test from $150 to $200 per week.

The 1970 rule relied on an approach similar to that used in the previous updates by analyzing actual salaries paid to EAP exempt employees. DOL found, as with previous rulemakings, that the survey data supporting the 1970 rule generally showed that the EAP salary level had become less of a line of demarcation for bona fide EAP employees since the previous salary level adjustment. Among the survey data findings were the following:

- In 19% of establishments with exempt executive employees, the lowest-paid executive employee earned less than the highest-paid nonexempt employee, which DOL noted was "very significant evidence that the current salary tests are no longer meaningful;"86

- 5% of exempt executive employees had salaries of $100 per week (the exemption threshold at the time);87

- 3% of exempt administrative employees had salaries of $100 per week (the exemption threshold at the time); and88

- 5% of exempt professional employees had salaries of less than $120 per week (the exemption threshold at the time was $115).89

As a whole, DOL noted that the EAP exemptions salary levels had to be increased to maintain their role as a demarcation for bona fide EAP employees and to eliminate from exemption such employees whose status as bona fide executive, administrative, or professional employees was "questionable in view of their low salaries."90

The new salary levels set in the 1970 rule meant that the percentages of exempt executive, administrative, and professional employees earning below the new thresholds would rise to 14%, 11%, and 17%, respectively.91

Finally, DOL adjusted the short test salary level to $200 per week (from $150 per week). This increased the ratio of short-to-long test salary levels to 160% (from 150%) for executive and administrative employees and to 143% (from 130%) for professional employees.

The 1975 Rule

The next change to the EAP exemptions occurred in 1975. The Secretary increased the salary level for executive and administrative employees from $125 to $155 per week and for professional employees from $140 to $170 per week. In addition, the 1975 rule increased the salary threshold for the short test from $200 to $250 per week.92 The rates set in 1975 were based on adjusting the 1970 salary levels by changes in the Consumer Price Index from 1970 to 1975.

Unlike any of the previous EAP rulemakings, DOL intended the updated levels to be in effect only for an interim period, pending the completion of a study by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).93 In setting the EAP salary levels in 1975, DOL noted that the "rapid increase in cost of living" since 1970 (the year of the previous EAP salary level adjustments) had "substantially impaired the current salary tests as effective guidelines" for determining the EAP exemptions. Thus, while the inflationary conditions necessitated the issuance of interim rates instead of waiting for the results of the BLS study, DOL also made it clear that the use of interim rates was not to be considered precedent for EAP exemptions rulemaking.94

The 2004 Rule

The Secretary updated the salary level for the EAP exemptions for the seventh time in 2004.95 Following 29 years in which the EAP exemptions had not been changed, the Secretary made several changes96 to the EAP salary and duties tests; the two primary changes were the following:

- Creation of a standard salary level. The 2004 rule harmonized the salary tests across exemption categories into a single standard salary level test of $455 per week, which was approximately equal to the 20th percentile of full-time salaried employees in the lowest-wage Census region (South) and in the lowest-wage industry sector (retail) in 2004;97 and

- Elimination of long and short tests. The 2004 rule created a single, standard duties test to replace the separate long and short tests. The 2004 rule required that an EAP employee's "primary duty" must consist of exempt work, as opposed to previous rulemaking limiting the percentage of work time an EAP employee could perform on work not considered executive, administrative, or professional. The elimination of the quantitative limit on nonexempt work made the standard test similar to the short test in use since 1949.

In setting the standard salary level in the 2004 rule, DOL noted its intention to establish the updated salary level based on the methodology in the 1958 rule (the "Kantor long test"), which set the long test salary threshold at a level at which no more than about 10% of EAP employees in the lowest-wage region, smallest-establishment group, smallest-city group, or lowest-wage industry group would fail to qualify for exemption.98

In 2004, DOL did not have available the type of data (i.e., the actual salaries paid to EAP exempt employees) it used in devising the methodology used in the 1958 rule and the similar methodologies used in setting the salary levels in the rulemakings from 1963 through 1975. Rather, DOL used survey data from the Current Population Survey in determining the salary level for the single, standard test (which replaced the long and short tests). In recognition of the fact that the CPS salary data covered both exempt and nonexempt workers and of the creation of a standard duties test (as opposed to two tests with two different salary levels), DOL set the 2004 salary level at a point in the earnings distribution that would exclude from exemption approximately 20% of full-time salaried workers in the South (lowest-wage region) and 20% of full-time salaried workers in the retail industry (lower-wage industry). Thus, DOL set the salary level at the 20th percentile of all full-time salaried employees (exempt and nonexempt) in the South and the retail industry, rather than at the 10th percentile of exempt employees. As part of the estimation process, DOL excluded from its salary analysis employees who are excluded on a regulatory or statutory basis from FLSA coverage or the salary requirement for overtime exemption.99

The 2016 Rule

The 2016 final rule, the eighth update since 1938, makes two main changes to the salary level exemptions:

- Increases the standard salary level. Effective December 1, 2016, the standard salary level for the EAP exemption is $913 per week, which is the 40th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census region (South);100 and

- Creates automatic updates to the salary level. The rule implements a mechanism to automatically update the EAP salary level thresholds.101 Starting January 1, 2020, and every three years thereafter, the standard salary level threshold will equal the 40th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time nonhourly workers in the lowest-wage Census region (South).102

The 2016 rule does not change the duties tests for EAP exemptions, and it leaves in place the single, standard test established in the 2004 rule.

In setting the standard salary level for exemption in the 2016 final rule, DOL again used CPS data on salaried workers to establish a wage distribution from which the threshold is derived. As with the 2004 rule, DOL established the salary level to exclude from exemption a certain percentage of EAP employees. However, it used different criteria than the 2004 rule and thus established a higher salary level than a methodology comparable to 2004 would have produced, based on the following:

- DOL set the standard salary level equal to the 40th percentile (rather than the 20th percentile) of weekly earnings of full-time salaried (i.e., nonhourly) workers in the lowest-wage Census region, which is currently the South region.103 That is, about 40% of full-time salaried workers in the South region earn at or below $913 per week ($47,476 annually);104

- DOL does not include salaries in the retail industry as a demarcation point for exemption. In rejecting the inclusion of the retail industry salaries in the salary level estimation, DOL noted that the historical parity between low-wage areas and low-wage industries does not exist at the 40th percentile and thus multiple duties tests would have been required to include these two salary levels;105

- DOL does not exclude from its salary analysis employees who are excluded on a regulatory or statutory basis from FLSA coverage or the salary requirement for overtime exemption.106 In other words, the salary distribution includes employees who would not be subject to either the salary test for overtime exemption (e.g., doctors, lawyers) or those excluded from FLSA coverage.

In establishing the salary level at the 40th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried employees, rather than the 20th percentile used in 2004, DOL argues that the 2004 threshold was too low because of the elimination of the long tests and the adoption of a standard test based on the short duties test.107 That is, the individual long tests for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions prior to 2004 had been accompanied by relatively lower salary thresholds, while the short test had been accompanied by a relatively higher salary threshold. DOL adopted the $913 salary level to "correct the mismatch" between the standard salary level, based on the previous long test levels, and the standard duties test, based on the previous short test.108

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For additional information, see https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime/final2016/litigation.htm. |

| 2. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, "Request for Information; Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees," 82 Federal Register 34616-34619, July 26, 2017. The comment period for the RFI closed on September 25, 2017. |

| 3. |