The Opioid Epidemic and Federal Efforts to Address It: Frequently Asked Questions

Over the last several years, there has been growing concern among the public and lawmakers in the United States about rising drug overdose deaths, which more than tripled from 1999 to 2014. In 2015, more than 52,000 people died from drug overdoses, and approximately 63% of those deaths involved an opioid.

Many federal agencies are involved in efforts to combat opioid abuse. The primary federal agency involved in drug enforcement, including diversion control efforts for prescription opioids, is the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The primary agency supporting drug treatment and prevention is the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The federal government also has several programs that may be used, or are specifically designed, to address opioid abuse. These range from law enforcement assistance in combatting drug trafficking to assistance for states in developing a coordinated response to address opioid abuse. These programs span across several departments, including (but not limited to) the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

Federal and state lawmakers have addressed opioid abuse as a public health concern in enacting legislation that focuses heavily on prevention and treatment. During the 114th Congress, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198) was enacted in the summer of 2016 and aimed to address the problem of opioid addiction in the United States. Further, the government enacted the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255)—a broader law that authorized new funding for medical research, amended the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approval process, and authorized additional funding to combat opioid addiction, among other things. Of note, CARA also addressed broader drug abuse issues, and the Cures Act largely addressed cures and treatment research. Congress also provided funds to specifically address opioid abuse in FY2017 appropriations.

This report answers common questions that have arisen as drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase. It does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse as a public health or criminal justice issue. The report is divided into the following sections:

Overview of Opioid Abuse;

Overview of Opioid Supply;

Select Federal Agencies and Programs that Address Opioid Abuse;

Recent Legislation; and

Opioid Abuse and State Policies.

The Opioid Epidemic and Federal Efforts to Address It: Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview of Opioid Abuse

- What is an opioid?

- How many Americans abuse opioids?

- What is the harm associated with opioid abuse?

- Which areas are experiencing a high number and/or rate of drug overdose deaths?

- Overview of Opioid Supply

- What is the recent history of the opioid supply in the United States?

- Prescription Drug Supply

- Heroin Supply

- Fentanyl Supply

- Where is the opioid supply threat greatest in the United States?

- Select Federal Agencies and Programs that Address Opioid Abuse

- Which HHS agencies address opioid abuse?

- What is SAMHSA's role in addressing opioid abuse?

- What is NIDA's role in addressing opioid abuse?

- What are other HHS agencies' roles in addressing opioid abuse?

- Which HHS grant programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

- Which Department of Justice (DOJ) agencies address opioid abuse?

- What is the Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA) role in addressing opioid abuse?

- Which DOJ programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

- How does the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) address opioid abuse?

- Which ONDCP programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

- Where can opioid-related grant funding data for states be found?

- What are the sources of national survey data on opioid abuse?

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

- Monitoring the Future Survey

- Recent Legislation

- What recent federal laws have been enacted that address the opioid epidemic?

- What programs authorized by CARA may be used to address opioid abuse?

- What opioid-related provisions were included in FY2017 appropriations?

- FY2017 Appropriations for CARA-Authorized, Opioid-Related Programs

- FY2017 Appropriations for Cures-Authorized, Opioid-Specific Programs

- FY2017 Appropriations for Other Opioid-Related Activities

- Opioid Abuse and State Policies

- What have the states done to combat opioid abuse?

- How have different states adapted their justice systems to deal with the opioid crisis?

Summary

Over the last several years, there has been growing concern among the public and lawmakers in the United States about rising drug overdose deaths, which more than tripled from 1999 to 2014. In 2015, more than 52,000 people died from drug overdoses, and approximately 63% of those deaths involved an opioid.

Many federal agencies are involved in efforts to combat opioid abuse. The primary federal agency involved in drug enforcement, including diversion control efforts for prescription opioids, is the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The primary agency supporting drug treatment and prevention is the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The federal government also has several programs that may be used, or are specifically designed, to address opioid abuse. These range from law enforcement assistance in combatting drug trafficking to assistance for states in developing a coordinated response to address opioid abuse. These programs span across several departments, including (but not limited to) the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP).

Federal and state lawmakers have addressed opioid abuse as a public health concern in enacting legislation that focuses heavily on prevention and treatment. During the 114th Congress, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198) was enacted in the summer of 2016 and aimed to address the problem of opioid addiction in the United States. Further, the government enacted the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255)—a broader law that authorized new funding for medical research, amended the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approval process, and authorized additional funding to combat opioid addiction, among other things. Of note, CARA also addressed broader drug abuse issues, and the Cures Act largely addressed cures and treatment research. Congress also provided funds to specifically address opioid abuse in FY2017 appropriations.

This report answers common questions that have arisen as drug overdose deaths in the United States continue to increase. It does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse as a public health or criminal justice issue. The report is divided into the following sections:

- Overview of Opioid Abuse;

- Overview of Opioid Supply;

- Select Federal Agencies and Programs that Address Opioid Abuse;

- Recent Legislation; and

- Opioid Abuse and State Policies.

Over the last several years, there has been growing concern among the public and lawmakers in the United States about rising drug overdose deaths, many of which involved opioids. Congress has responded to the issue through legislative activity and funding, while the Administration has sought to reduce supply and demand of illicit drugs through enforcement, prevention, and treatment.

This report does not provide a comprehensive overview of opioid abuse as a public health or criminal justice issue. Instead, it answers common questions that have arisen due to rising drug overdose deaths in the nation and the ensuing federal response.

Overview of Opioid Abuse

This section answers questions on the nature of opioid abuse in the United States. These questions provide background on the drugs that are abused, the associated harm to the population, and the extent of opioid abuse.

What is an opioid?

An opioid is a type of drug that when ingested binds to opioid receptors in the body—many of which control a person's pain and other functions. While these drugs are widely used to alleviate pain, some are abused by being taken in a way other than prescribed (e.g., in greater quantity) or taken without a doctor's prescription.1 Many prescription pain medications, such as hydrocodone and fentanyl, are opioids, as is heroin (an entirely illicit drug).

|

Terminology: Opioids and Opiates In current usage, the term "opioids" refers to all drugs derived from the opium poppy or emulating the effects of opium-derived drugs. Technically, the term "opiates" refers to natural compounds found in the opium poppy, and "opioids" refers to synthetic compounds that emulate the effects of opiates. In either case, the drugs act on opioid receptors in the brain. For this report, we rely on current usage of the term "opioids." |

How many Americans abuse opioids?

In its annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) does not collect data using the category "opioids"; rather, it collects data on use of heroin and misuse of prescription pain relievers. In 2016, SAMHSA estimated that 329,000 Americans age 12 and older were current users2 of heroin and approximately 3.8 million Americans were current "misusers"3 of prescription pain relievers.4

According to the same survey, an estimated 11.8 million people aged 12 and older misused opioids in the past year (i.e., the year preceding the date on which the individual responded to the survey) including 11.5 million misusers of pain relievers and 948,000 heroin users.5

In its annual survey of adolescent students, the Monitoring the Future Survey measures drug use behaviors among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. In 2016, 0.2% of surveyed adolescents were current users of heroin; 5.4% of surveyed 12th graders6 were current users of "narcotics other than heroin."7

What is the harm associated with opioid abuse?

There are short-term and long-term effects of abusing opioids, but the most severe among them is the risk of overdose and death. Drug overdose deaths more than tripled from 1999 to 2014.8 In 2015, more than 52,000 people died from drug overdoses, and approximately 63% of those deaths involved an opioid.9 More than 15,000 overdose deaths involved prescription opioids, representing almost half of all opioid overdoses.10 Also, while U.S. life expectancy (at birth) increased by 2.0 years overall (due to decreasing death rates related to heart disease, cancer, etc.) from 2000 to 2015, researchers have found that the increase in opioid-related drug poisoning death rate reduced overall life expectancy by 0.2 years during this same time.11

Reports indicate that recent increases in overdose deaths are most likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl and heroin.12 The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) states that fentanyl is largely to blame for the sharp increases in overdose deaths over the last several years. Further, NIDA explains that the number of fentanyl-related deaths is likely underestimated because some medical examiners do not test for fentanyl and some death certificates do not list specific drugs.13

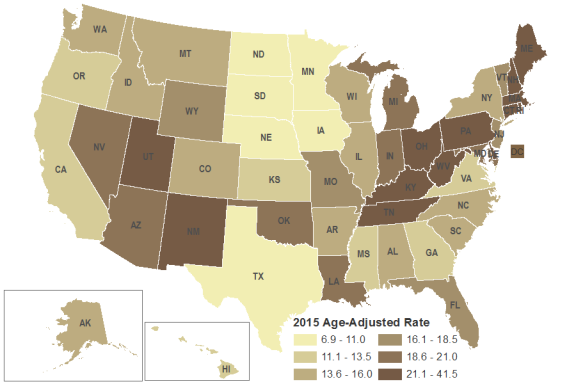

Which areas are experiencing a high number and/or rate of drug overdose deaths?

Opioids are the primary drugs involved in drug overdose deaths. The number and rate of drug overdose deaths varies by region of the United States. As might be expected, given it is the most populous state in the country, California had the highest number of drug overdose deaths (4,659) in 2015;14 however, not all states with the highest number of overdose deaths correspond with their high rank in population size. For example, Ohio had the second highest number of overdose deaths (3,310) and Massachusetts had the 9th highest number (1,724). These states rank 7th and 15th, respectively, in state population size.15

As shown in Figure 1, age-adjusted overdose death rates tell a different story than unstandardized numbers of overdose deaths. The Northeast and Appalachian regions, as well as certain Southwest states, have higher rates of drug overdose deaths compared to the rest of the country. As mentioned, fentanyl may be largely to blame for the sharp increases in overdose deaths over the last several years. According to a NIDA-funded study, in 2015 New Hampshire had the most fentanyl overdoses per capita, and nearly two-thirds of the 439 drug overdose deaths in the state involved fentanyl.16

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug Overdose Death Data, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Notes: CDC calculated age-adjusted death rates as deaths per 100,000 in population using the direct method and the 2000 standard U.S. population. Crude death rates are influenced by the age distribution of a state's population. Age-adjusting the rates ensures that differences from one year to another or between two areas are not due to differences in the age distribution of the states' populations. |

Overview of Opioid Supply

Heroin, fentanyl, and controlled prescription drugs17 have been ranked as the most significant drug threats to the United States.18 While the reported availability of controlled prescription drugs, which include opioids, has declined over the last several years, the reported availability of heroin has increased substantially. Further, there has been a rise in the availability of illicit fentanyl pressed into counterfeit prescription opioid pills.19

What is the recent history of the opioid supply in the United States?

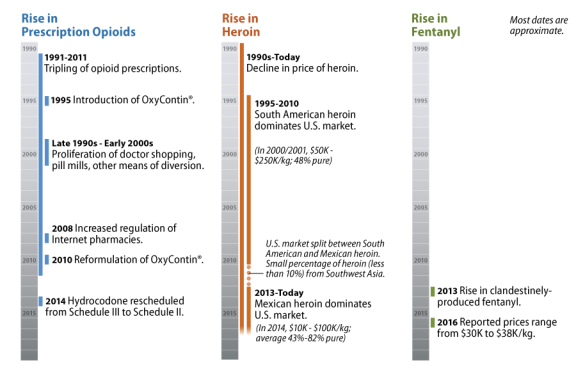

Opioids have been available in the United States since the 1800s, but the market for these drugs shifted significantly beginning in the 1990s. This section focuses on this latter period (see Figure 2)

Prescription Drug Supply

In the 1990s, the availability of prescription opioids, such as hydrocodone and oxycodone, increased as the legitimate production of these drugs and diversion of them increased sharply.20 This continued into the early 2000s, as abusers attained their prescription drugs through "doctor shopping," bad-acting physicians,21 pill mills,22 the Internet, pharmaceutical theft, prescription fraud, and family and friends.

How has the federal government responded to the proliferation of prescription drugs?

The federal government, along with state and local governments, undertook a range of approaches to reducing the unlawful prescription drug supply and prescription drug abuse, including diversion control through prescription drug monitoring programs,23 a crackdown on pill mills, the increased regulation of Internet pharmacies,24 the reformulation of OxyContin® (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release),25 and the rescheduling of hydrocodone.26

Some experts have highlighted the connection between the crackdown on the unlawful supply of prescription drugs and the subsequent rise in the heroin supply (as discussed in the next section) and abuse of the drug. Heroin is a cheaper alternative to prescription drugs that may be accessible to some who are seeking an opioid high. While most users of prescription drugs will not go on to use heroin, accessibility and price are central factors cited by patients with opioid dependence in their decision to turn to heroin.27

Heroin Supply

The trajectory of the heroin supply over the last several decades is much different than that of prescription opioids, but their stories are connected.28 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, white powder heroin produced in South America dominated the market east of the Mississippi River, and black tar and brown powder heroin produced in Mexico dominated the market west of the Mississippi.29 Most of the heroin destined for the United States at that time came from South America, while smaller percentages came from Mexico and Southwest Asia.

Price and purity varied considerably by region. The average retail-level purity of South American heroin was around 46%, which was considerably higher than that of Mexican, Southeast Asian, or Southwest Asian heroin. At the time, Mexican heroin was around 27% pure, while Southeast Asian and Southwest Asian heroin were around 24% and 30% pure, respectively.30 Prices for heroin fell dramatically in the 1990s—it was 55% to 65% less expensive in 1999 than in 1989.31

Over the last several years, heroin prices have further declined, while purity, in particular that of Mexican heroin, has increased. The availability of Mexican heroin has also grown. Over 90% of the heroin currently seized in the United States is from Mexico (while a much smaller portion is from South America). Mexico dominates the U.S. heroin market because of its proximity and its established transportation and distribution infrastructure, which improves traffickers' ability to satisfy U.S. heroin demand. Increases in Mexican production have ensured a reliable supply of low-cost heroin, even as demand for the drug has increased. Mexican traffickers have particularly increased their production of white powder heroin and may be targeting those who abuse prescription opioids.32

Fentanyl Supply

Exacerbating the current opioid problem is the rise of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl33 on the black market. Diverted pharmaceutical fentanyl represents only a small portion of the fentanyl market. Non-pharmaceutical fentanyl largely comes from China, and it is often mixed with or sold as heroin. It is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin, and over the last two years, reported prices ranged between $30,000 and $38,000 per kilogram. The increased potency of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl compounds, such as the recently emerged "gray death,"34 is extremely dangerous. Law enforcement expects that the fentanyl market will continue to expand in the future as new fentanyl products attract additional users.35

Where is the opioid supply threat greatest in the United States?

The supply of opioids varies by region. In 2016, approximately 45% of respondents to the National Drug Threat Survey (NDTS) reported heroin as the greatest drug threat in their area. In contrast, 8% of respondents reported heroin as the greatest threat in 2007. Reports of heroin as the greatest threat are concentrated in the Northeast, Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic regions.36 Additionally, DEA investigative reporting indicates high controlled prescription drug availability in cities throughout the United States.

Opioids are the main cause of drug overdose deaths. Reports indicate that increases in overdose deaths are most likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl and heroin. 37 The increasing availability of heroin throughout the United States largely, but not entirely, corresponds to high numbers of drug overdose deaths (see Figure 1). For example, New Mexico and Utah rank 8th and 9th, respectively, in the country in drug overdose deaths, but only 4.7% of NDTS respondents in the Southwest reported heroin as the greatest drug threat and 22.6% reported high availability of heroin in their region.38 The discrepancy between overdose deaths and drug threats may be explained by a number of factors, including the lethality of fentanyl.

Select Federal Agencies and Programs that Address Opioid Abuse

This section discusses the efforts of federal agencies under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Justice (DOJ), and the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) to combat opioid abuse. While many federal departments/agencies are involved in these efforts, this section focuses on those agencies that include drug prevention, treatment, or enforcement as a primary mission. It also includes grant-issuing agencies that specifically target drug abuse.

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), part of DOJ, is the primary federal agency involved in drug enforcement, including diversion control39 efforts for prescription opioids. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), part of HHS, is the primary federal agency supporting drug treatment and prevention. The federal government also has several programs (many of which are grant programs) that may be used, or are specifically designed, to address opioid abuse. These range from law enforcement assistance in combatting drug trafficking to assistance for states in developing a coordinated response to address opioid abuse. These programs span across several departments and agencies including, but not limited to, DOJ, HHS, and ONDCP.

This section does not address other federal agencies that support—but are not focused on—drug enforcement, treatment, or prevention. For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, part of the Department of Homeland Security, concentrates on customs, immigration, border security, and agricultural protection. While drug control is a part of what it does (through drug interdiction at the border), it is not a central focus of the agency's mission. Other agencies across the federal government also take part in drug control activities, but they are beyond the scope of this report.40

Which HHS agencies address opioid abuse?

Several agencies within HHS play roles in monitoring, researching, preventing, and/or treating opioid abuse. In most cases, opioid abuse—or drug abuse more generally—is a relatively small component of an agency's activities. Two HHS agencies focus on drug abuse: (1) SAMHSA and (2) the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

What is SAMHSA's role in addressing opioid abuse?

SAMHSA is the lead federal agency for increasing access to behavioral health services.41 SAMHSA supports community-based mental health and substance abuse treatment and prevention services through formula grants to the states and U.S. territories and through competitive grant programs to states, territories, tribal entities,42 local communities, and private entities. SAMHSA also engages in a range of other activities that support substance abuse prevention and treatment, such as technical assistance, data collection, and workforce development. Activities related to combatting opioid abuse are primarily administered by two centers within SAMHSA: the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.

What is NIDA's role in addressing opioid abuse?

NIDA is the lead federal agency for advancing and applying scientific research on the causes and consequences of drug abuse.43 NIDA conducts its own research and funds outside basic (laboratory), clinical, translational, and implementation research.44 NIDA-conducted or -funded research aims to advance basic science, prevention, treatment, and public health approaches to drug abuse. NIDA publishes research summaries to disseminate findings and raise awareness.

What are other HHS agencies' roles in addressing opioid abuse?

HHS agencies other than SAMHSA and NIDA also play a role in combatting opioid abuse. Examples include (but are not limited to) the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- CMS finances health care services, including substance abuse treatment services, through Medicare and the federal share of Medicaid.

- HRSA supports access to care, including access to substance abuse treatment services, for underserved populations.45

- CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control seeks to prevent injuries and deaths, including those caused by drug overdoses.

Which HHS grant programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

Below are examples of HHS grant programs (including cooperative agreements and contracts) that address or may be used to address opioid abuse; it is not an exhaustive list of such programs, which would include nearly all of the programs administered by SAMHSA's Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.46 Instead, this section focuses on programs and activities that HHS agencies have identified as part of their efforts to address the opioid crisis, as well as some examples of broader substance use disorder programs that may be used in part to address opioid use disorder.47

Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant (SABG)

The SABG supports services to prevent and treat substance use disorders. SAMHSA distributes SABG funds to states (including the District of Columbia, specified territories, and one tribal entity48) according to a formula. Each state may distribute SABG funds to local government entities and nongovernmental organizations in accordance with a required state plan for providing substance use disorder prevention and treatment services (and subject to other federal requirements).49 States are given flexibility in the use of SABG funds within the framework of the state plan and federal requirements. Each SABG grantee must expend at least 20% of its SABG allotment on primary prevention strategies.50

State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis Grants

The State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis grant program supports states in addressing the opioid abuse crisis through activities that supplement opioid-related activities undertaken by the state agency that administers the SABG.51 In FY2017 (the first year of this program), SAMHSA awarded formula grants to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Northern Marianas, Micronesia, Palau, and American Samoa.52

Strategic Prevention Framework for Prescription Drugs

The Strategic Prevention Framework for Prescription Drugs (SPF Rx), as part of SAMHSA's larger Strategic Prevention Framework, supports infrastructure development and prescription drug abuse prevention efforts. Eligibility is limited to states (including the District of Columbia, specified territories, and tribal entities) that have completed a Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant.

First Responder Training

The First Responder Training program aims to reduce the number of deaths and adverse events related to opioids and other prescription drugs.53 In FY2017 (the first year of this program), SAMHSA awarded 21 grants to states or other entities that will train first responders (and others) to "implement secondary prevention strategies, such as the administration of naloxone through FDA-approved delivery devices to reverse the effects of opioid overdose."54

Improving Access to Overdose Treatment

Under the Improving Access to Overdose Treatment grant program, SAMHSA awarded one grant in FY2017 (the first year of this program) to expand access to emergency treatment of opioid overdose (i.e., naloxone).55 The grantee is to develop best practices for prescribing naloxone and train others accordingly.56

Medication Assisted Treatment-Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction

The Medication Assisted Treatment-Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction (MAT-PDOA) program, as part of SAMHSA's Targeted Capacity Expansion program, supports states in expanding or enhancing the capacity to provide medication assisted treatment (i.e., the combined use of medication and psychosocial interventions to treat opioid addiction).

State Pilot Grant Program for Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women

The Pregnant and Postpartum Women program has historically supported residential substance use disorder treatment services for pregnant and postpartum women. In FY2017, SAMHSA awarded three newly authorized state pilot grants to:

(1) support family-based services for pregnant and postpartum women with a primary diagnosis of a substance use disorder, including opioid disorders;

(2) help state substance abuse agencies address the continuum of care, including services provided to women in nonresidential-based settings; and

(3) promote a coordinated, effective and efficient state system managed by state substance abuse agencies by encouraging new approaches and models of service delivery.57

These state pilot grants are in addition to new and continuing grants and contracts awarded under the larger Pregnant and Postpartum Women program.58

Building Communities of Recovery

For FY2017 (the first year of the program), SAMHSA awarded eight grants under its Building Communities of Recovery grant program to recovery-focused community organizations.59 Grantees are to use the funds to develop, expand, and enhance recovery support services such as peer support services and linkages to other services (e.g., housing or child care).60

Criminal Justice Activities

Under its "criminal justice activities" account, SAMHSA administers several grant programs that focus on drug courts and re-entry services for drug-involved criminal offenders. Through its Treatment Drug Court grants, SAMHSA seeks to improve treatment services for drug court clients.61 Through its Offender Reentry Program, SAMHSA supports screening, assessment, comprehensive treatment, and recovery support services for individuals re-entering the community from incarceration. 62

Prevention for States

Under the Prevention for States program, CDC supports state health departments in advancing their overdose prevention efforts in four areas:

- 1. making the best use of state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs),

- 2. improving relevant practices of health systems and insurers,

- 3. evaluating policies, and

- 4. responding rapidly to emerging situations.63

Enhanced State Surveillance of Opioid-Involved Morbidity and Mortality

Under the Enhanced State Surveillance of Opioid-Involved Morbidity and Mortality program, CDC awards cooperative agreements to states to improve surveillance of fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses by increasing timeliness of reporting, disseminating findings, and sharing data with CDC.64

Data-Driven Prevention Initiative

Under the Data-Driven Prevention Initiative, CDC supports state efforts to address the opioid crisis by increasing their capacity to collect and analyze data about opioid use disorder and overdose, developing strategies to change behaviors driving opioid use disorder, and collaborate with communities to develop more comprehensive programs.65

Rural Health Opioid Program

Under the Rural Health Opioid Program, HRSA supports the development of community consortiums to respond comprehensively to the opioid epidemic in their (rural) communities through the combined efforts of health care providers and other entities (e.g., social service organizations and law enforcement). Supported activities include outreach, care coordination, and recovery support services, among others.66

Substance Abuse Treatment Telehealth Network Grant Program

Under the Substance Abuse Treatment Telehealth Network grant program, HRSA supports the use of telehealth programs and networks to provide substance use disorder treatment in rural, frontier, and underserved communities.67As a secondary purpose, the program also supports the use of such programs to treat common chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes) in order to make the most of the investment in telehealth.

Which Department of Justice (DOJ) agencies address opioid abuse?

Several agencies within DOJ address opioid abuse through administrative efforts, research, grants, and enforcement of drug laws. DOJ agencies, primarily the DEA, enforce federal controlled substances laws in all states and territories.68 The Offices of the U.S. Attorneys are responsible for the prosecution of federal criminal and civil cases, which include cases against illicit drug traffickers, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmacies. The Office of Justice Programs (OJP), primarily through the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), addresses opioid abuse through research and grant support.

What is the Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA) role in addressing opioid abuse?

The DEA is a federal law enforcement agency that also has a regulatory function. While it conducts traditional law enforcement activities such as investigating drug trafficking (including trafficking of heroin and other opioids), it also regulates the flow of controlled substances in the United States. The Controlled Substances Act (CSA)69 requires the DEA to establish and maintain a closed system of distribution for controlled substances; this involves the regulation of anyone who handles controlled substances, including exporters, importers, manufacturers, distributors, health care professionals, pharmacists, and researchers.

Unless specifically exempted by the CSA, these individuals must register with the DEA. Registrants must keep records of all transactions involving controlled substances, maintain detailed inventories of the substances in their possession, and periodically file reports with the DEA, as well as ensure that controlled substances are securely stored and safeguarded.70 The DEA regulates over 1.5 million registrants.71

The DEA uses its criminal, civil, and administrative authorities to maintain a closed system of distribution and prevent diversion of drugs, such as prescription opioids, from legitimate purposes. Actions include inspections, order form requirements, education, and establishing quotas for Schedule I and II controlled substances.72 More severe administrative actions include immediate suspension orders and orders to show cause for registrations.73

Which DOJ programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

Below is a list of programs that have a direct or possible avenue to address opioid abuse. This list provides examples of such programs, and should not be considered exhaustive. Many DOJ programs have broad purpose areas for which funds can be used. While some focus on broad crime reduction strategies that might include efforts to combat drug-related crime, others are more focused on drug threats more specifically—the selected programs have purpose areas that are clearly linked to drug threats more specifically.

Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Program

Section 201 of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 (CARA; P.L. 114-198) authorized the Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Grant Program for states, units of local government, and Indian tribes. These grants are intended to provide services primarily relating to opioid abuse, including (1) treatment alternatives to incarceration programs, (2) collaboration between criminal justice and substance abuse agencies, (3) training and resources for first responders to administer opioid overdose reversal drugs, (4) investigation of illicit activities related to unlawful distribution of opioids, (5) medication-assisted treatment programs used by criminal justice agencies, (6) prescription drug monitoring programs, (7) programs to prevent and address opioid abuse by juveniles, (8) programs that utilize technology to secure containers for prescription drugs, (9) prescription drug take-back programs, and (10) a comprehensive opioid abuse response program.74 BJA administers this new grant program, and in FY2017 the bureau released two grant solicitations for it.75

Of note, the Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) was incorporated into the Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Grant Program.76 The Harold Rogers PDMP is a discretionary, competitive grant program administered by BJA. It was created to help law enforcement, regulatory entities, and public health officials analyze data on prescriptions for controlled substances. Law enforcement uses of PDMP data include (but are not limited to) investigations of physicians who prescribe controlled substances for drug dealers or abusers, pharmacists who falsify records in order to sell controlled substances, and people who forge prescriptions.77 These grants are for states and territories.

COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program

The Anti-Heroin Task Force program is a "competitive grant program designed to advance public safety by providing funds to investigate illicit activities related to the distribution of heroin or unlawful distribution of prescriptive opioids, or unlawful heroin and prescription opioid traffickers through statewide collaboration."78 Funds are distributed to state law enforcement agencies in states with high rates of primary treatment admissions for heroin and other opioids. Funding under the program must be used for investigative purposes, including activities related to the distribution of heroin or unlawful distribution or diversion of prescription opioids.

The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program79

The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program provides funding to state, local, and tribal governments for state and local initiatives, technical assistance, training, personnel, equipment, supplies, contractual support, and criminal justice information systems in eight program purpose areas. These purpose areas are (1) law enforcement programs; (2) prosecution and court programs; (3) prevention and education programs; (4) corrections and community corrections programs; (5) drug treatment and enforcement programs; (6) planning, evaluation, and technology improvement programs; (7) crime victim and witness programs (other than compensation); and (8) mental health and related law enforcement and corrections programs, including behavioral programs and crisis intervention teams. Given the breadth of the program, funds could be used for opioid abuse programs, but state and local governments that receive JAG funds are not required to use their funding for this purpose.

Drug Court Discretionary Grant Program80

The Drug Court Discretionary Grant program81 is meant to enhance drug court services, coordination, and substance abuse treatment and recovery support services. It is a discretionary grant program that provides resources to state, local, and tribal courts and governments to enhance drug court programs for nonviolent substance-abusing offenders. Drug courts are designed to help reduce recidivism and substance abuse among nonviolent offenders and increase an offender's likelihood of successful rehabilitation through early, continuous, and intense judicially supervised treatment, mandatory periodic drug testing, community supervision, appropriate sanctions, and other rehabilitation services.

The program doesn't specifically address opioid abuse, but drug-involved offenders, including opioids abusers, may be processed through drug courts where they receive treatment for drug addiction.

Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) Formula Grants82

The JJDPA authorizes the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) to make formula grants to states that can be used to fund the planning, establishment, operation, coordination, and evaluation of projects for the development of more-effective juvenile delinquency programs and improved juvenile justice systems. Funds provided to the state may be used for a wide array of juvenile justice related programs, such as substance abuse prevention and treatment programs, among many purpose areas. None of the program purpose areas deal specifically with combating opioid abuse, but they are broad enough that they could be used for this purpose.

JJDPA Title V Incentive Grants Program

The JJDPA83 authorizes OJJDP to make discretionary grants to the states that are then transmitted to units of local government in order to carry out delinquency prevention programs for juveniles who have come into contact with, or are likely to come into contact with, the juvenile justice system. Purpose areas include (but are not limited to) alcohol and substance abuse prevention services, educational programs, and child and adolescent health (as well as mental health) services. None of the program purpose areas deal specifically with combating opioid abuse, but they are broad enough that they could be used for this purpose.

How does the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) address opioid abuse?

The ONDCP is located in the Executive Office of the President and is responsible for creating policies, priorities, and objectives for the federal Drug Control Program. ONDCP's mission focuses on reducing the use, manufacturing, and trafficking of illicit drugs and the reduction of drug-related crime, violence, and drug-related health consequences. The director of ONDCP is responsible for developing a comprehensive National Drug Control Strategy (Strategy) to direct the nation's anti-drug efforts; developing a National Drug Control Budget (Budget) to implement the Strategy, including determining the adequacy of the drug control budgets submitted by contributing federal Drug Control Program agencies; and evaluating the effectiveness of the Strategy implementation by the various agencies contributing to the Drug Control Program.

In response to the opioid epidemic, the Trump Administration has requested increases for certain drug control measures in the FY2018 Budget.84 In addition, President Trump created the President's Commission on Combatting Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. In coordination with ONDCP, this commission issued a draft interim report recommending several executive actions to address the opioid epidemic.85 A final report was due on October 1, 2017, but the status of this report is unknown.86

Which ONDCP programs may be used to address opioid abuse?

High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) Program87

This program provides assistance to law enforcement agencies—at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels—that are operating in regions of the United States that have been deemed by ONDCP (in consultation with other agencies) as critical drug trafficking regions. The program aims to reduce drug production and trafficking through four means:

- 1. promoting coordination and information sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- 2. bolstering intelligence sharing between federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement;

- 3. providing reliable intelligence to law enforcement agencies so that they may be better equipped to design effective enforcement operations and strategies; and

- 4. promoting coordinated law enforcement strategies that rely upon available resources to reduce illegal drug supplies not only in a given area, but throughout the country.

The HIDTA program does not focus on a specific drug threat, such as heroin trafficking; instead, funds can be used to support the most pressing problems in a region. As such, when countering trafficking of heroin and other opioids is a top priority in a HIDTA region, funds may be used to support it. There are 28 HIDTAs, encompassing approximately 18% of U.S. counties and over 65% of the U.S. population.88 While this program is administered by ONDCP, the DEA plays a major role, with 600 authorized special agent positions dedicated to it.89

Drug Free Communities Support Program90

ONDCP manages the Drug Free Communities Support program, which provides grants to coalitions91 to implement comprehensive, long-term plans and programs to prevent and treat substance abuse among youth. These grants fund community-based coalitions made up of community leaders across 12 sectors, including businesses, law enforcement, and schools. Currently, there are 698 DFC-funded coalitions.92

Other ONDCP Programs

Under its Other Federal Drug Control Programs account, ONDCP offers drug court training and technical assistance grants, as well as support for other initiatives that may be used to combat opioid abuse.93

Where can opioid-related grant funding data for states be found?

HHS—For relevant state-specific HHS grants and funding data, see the grant web pages for SAMHSA,94 CDC,95 and HRSA.96

OJP—For state-specific data on grants and funding from OJP, see the OJP Award Data web page97 and search data by location.

ONDCP—ONDCP grant data are not currently available online. To view the HIDTA program map, see the DEA site for the HIDTA program.98

What are the sources of national survey data on opioid abuse?99

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

SAMHSA funds the NSDUH,100 which focuses primarily on the use of illegal drugs, alcohol, and tobacco (and also includes several modules that focus on other health issues).101 Each year, the NSDUH surveys approximately 68,000 non-institutionalized U.S. civilians, 12 years or older, including approximately 51,000 adults (aged 18 or older) and 17,000 adolescents (aged 12 to 17).102 The NSDUH is conducted in both English and Spanish. Participants are interviewed in their homes using a combination of personal interviewing and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing, which offers more privacy in order to encourage honest reporting of sensitive topics such as illicit drug use. The sample does not include homeless persons not living in a shelter, individuals in institutions (such as jails or hospitals), those who speak a language other than English or Spanish, or military personnel on active duty; these exclusions limit the generalizability of findings based on the NSDUH.103

Monitoring the Future Survey

NIDA funds the Monitoring the Future survey,104 which focuses primarily on secondary school students', college students', and young adults' drug-related beliefs, attitudes, and behavior. Each year, Monitoring the Future surveys approximately 50,000 U.S. students in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades in about 400 public and private schools.105 Participants complete questionnaires that are distributed in their normal classrooms and are self-administered. Each year, a random sample of the 12th grade students is selected to receive a follow-up questionnaire by mail every two years.

Recent Legislation

What recent federal laws have been enacted that address the opioid epidemic?

Federal legislation has taken a public health approach (i.e., focusing on prevention and treatment) towards addressing the nation's opioid crisis.106 Two major laws were enacted in the 114th Congress that address the opioid epidemic—the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA, P.L. 114-198) and the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act; P.L. 114-255). CARA focused primarily on opioids and also addressed broader drug abuse issues. The Cures Act authorized state opioid grants (in Division A) and included more general substance abuse provisions (in Division B) as part of a larger effort to address health research and treatment. Further, Congress appropriated funds to specifically address opioid abuse in FY2017 appropriations.

What programs authorized by CARA may be used to address opioid abuse?

Below are authorizations of appropriations in CARA, by administering agency and title/section of CARA. All dollar amounts below are rounded to the nearest million. Although CARA is generally discussed in the context of the opioid epidemic, a few of the authorizations of appropriations are not specific to opioids, but are related to substance use disorders more generally. These instances are noted with "(not specific to opioids)." Most of the authorizations of appropriations in CARA are annual (e.g., "$10 million annually for FY2017-FY2021"); however, two are for a period of years (e.g., "$5 million for the period FY2017-FY2021").

HHS Programs

- Title I, §107. Reducing Overdose Deaths: $5 million for the period FY2017-FY2021.

- Title I, §109. Reauthorization of NASPER (National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting) (not specific to opioids): $10 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($50 million for the entire period).

- Title I, §110. Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication Access: $5 million for the period FY2017-FY2019.

- Title II, §202. First Responder Training for Emergency Treatment of Known or Suspected Opioid Overdose: $12 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($60 million for the entire period).

- Title III, §301. Evidence-Based Prescription Opioid and Heroin Treatment and Interventions Demonstration: $25 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($125 million for the entire period).

- Title III, §302. Building Communities of Recovery [not specific to opioids]: $1 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($5 million for the entire period).

- Title V, §501. Reauthorization of Residential Treatment Program for Pregnant and Postpartum Women (not specific to opioids): $17 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($85 million for the entire period).

- Title VI, §601. State Demonstration Grants for Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Response: $5 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($25 million for the entire period).

ONDCP Program

- Title I, §103. Community-based Coalition Enhancement Grants to Address Local Drug Crises (not specific to opioids): $5 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($25 million for the entire period).

DOJ Program

- Title II, §201. Comprehensive Opioid Abuse: $103 million annually for FY2017-FY2021 ($515 million for the entire period).

What opioid-related provisions were included in FY2017 appropriations?

FY2017 Appropriations for CARA-Authorized, Opioid-Related Programs

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) provided $20 million for CARA-authorized HHS-administered programs.107 This included two programs that were opioid-specific and two that were not opioid-specific.108 The two opioid-specific programs are First Responder Training for Emergency Treatment of Known or Suspected Opioid Overdose ($12 million) and Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication Access ($1 million).109 The two non-opioid-specific programs are Building Communities of Recovery ($3 million) and Pregnant & Postpartum Women (with a $4 million increase over FY2016).110

Under DOJ, State and Local Law Enforcement Assistance account, Congress provided $103 million for "comprehensive opioid abuse reduction activities" that address opioid abuse consistent with underlying program authorities including those programs authorized by CARA—this is broken down in another section as most programs are not authorized by CARA.

Under the Department of Veterans Affairs, $50 million was provided for "continued implementation of the Jason Simcakoski Memorial and Promise Act [enacted as Title IX of CARA] and to bolster opioid and substance abuse prevention and treatment."111 Of note, CARA did not explicitly authorize funding for this program, but rather authorized the program activities of the Jason Simcakoski Memorial and Promise Act.

FY2017 Appropriations for Cures-Authorized, Opioid-Specific Programs

The second continuing resolution for FY2017 (P.L. 114-254) appropriated full-year FY2017 funding for the sole opioid-specific grant program authorized by Section 1003 of the Cures Act. The appropriated amount is $500 million, the same as the authorization.

FY2017 Appropriations for Other Opioid-Related Activities

Some programs and activities for which opioid abuse is not the primary focus (as authorized in statute) may spend some portion of their funding on opioid-related activities. For example, programs focused on substance abuse generally may address opioid abuse as part of the larger effort. CRS generally does not have a means for determining the proportion of funding for general substance abuse programs that ultimately goes toward opioid abuse. In some cases, however, the joint explanatory statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, specifies the amount of funding to be used to address opioid abuse. For example, the statement specifies $56 million for SAMHSA's Medication Assisted Treatment for Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction (MAT-PDOA) program, a component within a more general program called Targeted Capacity Expansion.112

Opioid-specific appropriations for HHS are not limited to SAMHSA. For example, the explanatory statement specifies that, within the total amount appropriated for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Center for Injury Prevention and Control, $112 million is to address prescription opioid overdose and $14 million is to address illicit opioid use risk factors.113 Within the total amount appropriated for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for Primary Health Care, the explanatory statement indicates that "not less than [$50 million] shall be awarded for services related to the treatment, prevention, and awareness of opioid abuse."114

As mentioned, under DOJ, the Consolidated Appropriations Act provided $103 million under the State and Local Law Enforcement Assistance account for "comprehensive opioid abuse reduction activities"; however, most of the funding for these activities was not new. Rather, part of the funding for the initiative came from the following programs: Drug Courts ($43 million), Veterans Treatment Courts ($7 million), Residential Substance Abuse Treatment ($14 million), Prescription Drug Monitoring ($14 million), and programs to address individuals with mental illness in the criminal justice system ($12 million).115

Additionally, under the DOJ, Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) account, $10 million was provided for competitive grants to statewide law enforcement agencies in states with high rates of primary treatment admissions for opioids. These funds must be used for "investigative purposes to locate or investigate illicit activities, including activities related to the distribution of heroin or unlawful distribution of prescription opioids, or unlawful heroin and prescription opioid traffickers through statewide collaboration."116

Opioid Abuse and State Policies

What have the states done to combat opioid abuse?

States have enacted laws that increase access to naloxone (an opioid overdose reversal drug), provide immunity from prosecution for those who seek assistance related to an overdose, enhance prescription drug monitoring programs, and broaden access to substance abuse treatment, among other things.117 Over the last few years, several state governors have declared the opioid problem to be a "state of emergency" or "public health emergency."118 Doing so has allowed governors to take swift, coordinated action to combat it. In Massachusetts, for example, then-Governor Deval Patrick utilized his emergency power to allow first responders to carry and administer naloxone, in addition to other actions.119

States are also developing opioid-related education initiatives. For example, in December 2014 Ohio enacted a law that required the health curriculum of each Ohio school district to include instruction in prescription opioid abuse prevention.120 In June 2017, Governor Wolf of Pennsylvania announced support for a bill that would establish a mandatory school-based substance abuse prevention and intervention program for all students in every grade from kindergarten through grade 12.121

State officials have been involved in a number of national initiatives including the drafting of coordinated policies and recommendations from the National Governors Association (NGA), reports on state legislation to increase access to treatment for opioid overdose from the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (NASADAD), and participation in the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis.122

How have different states adapted their justice systems to deal with the opioid crisis?

Across the country, states have adapted elements of their criminal justice responses—including police, court, and correctional responses123—in a variety of ways due to the opioid epidemic. While this section does not provide a state-by-state analysis, it highlights several examples of how states' justice systems have responded to the opioid crisis.

Many states are increasing law enforcement officer access to naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug.124 Officers receive training on how to identify an overdose and administer naloxone, and they carry the drug so they can respond immediately and effectively to an overdose. As of December 2016, over 1,200 police departments in 38 states had officers that carry naloxone.125 In addition, most states that have expanded access to naloxone have also provided immunity to those who possess, dispense, or administer the drug. Generally, immunity entails legal protections (for civilians) from arrest or prosecution and/or civil lawsuits for those who prescribe or dispense naloxone in good faith.126

Another criminal justice adaptation is the enactment of what are known as "Good Samaritan" laws to encourage individuals to seek medical attention (for themselves or others) related to an overdose without fear of arrest or prosecution. In general, these laws prevent criminal prosecution for illegal possession of a controlled substance under specified circumstances. While these laws vary by state as to what offenses and violations are covered, as of June 2017, 40 states and the District of Columbia have some form of Good Samaritan overdose immunity law.127

Most states have drug diversion or drug court programs128 for criminal defendants and offenders with substance abuse issues, including opioid abuse.129 Some states view drug courts as a tool to address rising opioid abuse and have moved to further expand drug court options in the wake of the opioid epidemic. In August 2016, representatives from several states that have been confronted with high opioid overdose death rates130 convened for the Regional Judicial Opioid Summit. Part of these states' action plans to address opioid abuse was to expand drug courts and other court diversion and sentencing options that provide substance-abuse treatment and alternatives to incarceration.131 Further, in April 2017 NGA announced that eight states would participate in a "learning lab" to develop best practices for dealing with opioid abuse treatment for justice-involved populations—including the expansion of opioid addiction treatment in drug courts.132

In recent years, several states have also enacted legislation increasing access to medication-assisted treatment for drug-addicted offenders who are incarcerated or have recently been released.133

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Opioids, May 2016, https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids. This CRS report uses the common term "abuse" to encompass a range of behaviors that are not limited to addiction. Such behaviors are variously described as "illicit use", "non-medical use", or "misuse", among other terms. See, for example, the terms used in American College of Preventive Medicine, Use, Abuse, Misuse & Disposal of Prescription Pain Medication: Clinical Reference, Washington, DC, 2011; and Federation of State Medical Boards, Model Policy on the Use of Opioid Analgesics in the Treatment of Chronic Pain, July 2013, pp. 15-18. |

| 2. |

Current use is defined as use in the past month. |

| 3. |

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines misuse of prescription drugs as "use in any way not directed by a doctor including use without a prescription of one's own medication; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than told to take a drug; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor." Prescription drugs do not include over-the-counter drugs. |

| 4. |

Subtypes of pain relievers include hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, morphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, oxymorphone, Demerol®, hydromorphone, and methadone. See HHS, SAMHSA, Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, September 2016, Tables 1.1A and 1.1B, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/population-data-nsduh/ and Methodological Summary and Definitions, Table C-1, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2016.htm#figc1. |

| 5. |

Some respondents fell into both categories, which is why the total (11.8 million) is lower than the two categories combined. See HHS, SAMHSA, Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, September 2017. See Tables 1.1A and 1.27A at https://www.samhsa.gov/data. |

| 6. |

8th and 10th graders were not asked about their use of narcotics other than heroin. |

| 7. |

Current use is defined as use in the past 30 days. Only drug use not under a doctor's orders is included. A list of narcotics, including Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet, is provided to the respondents. For more information, see Lloyd D. Johnston, Patrick M. O'Malley, and Richard A. Miech, et al., Monitoring the Future, National Survey Results on Drug Use: 2016 Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use, The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, January 2017. |

| 8. |

Rose A. Rudd, Puja Seth, and Felicita David, et al., Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2010–2015, HHS, CDC, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), December 30, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm. |

| 9. |

Ibid. This percentage has remained fairly steady over the last several years. In 2014, 60.9% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid. In 2015, 63.1% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid. |

| 10. |

These include deaths with underlying causes of unintentional drug poisoning, suicide drug poisoning, homicide drug poisoning, or drug poisoning. For more information, see HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Prescription Opioid Overdose Data, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html; and National Institute on Drug Abuse, Overdose Death Rates, September 2017, https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. |

| 11. |

Deborah Dowell, Elizabeth Arias, and Kenneth Kochanek, et al., "Contribution of Opioid-Involved Poisoning to the Change in Life Expectancy in the United States, 2000-2015," Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 318, no. 11 (September 19, 2017), pp. 1065-1067. |

| 12. |

HHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Prescription Opioid Overdose Data, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/overdose.html. |

| 13. |

HHS, NIH, NIDA, Addressing America's Fentanyl Crisis, April 6, 2017, https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2017/04/addressing-americas-fentanyl-crisis. |

| 14. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Drug Overdose Death Data, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html; and U.S. Census Bureau, State Population Totals Tables: 2010-2016, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/popest/state-total.html. |

| 15. |

Ibid. |

| 16. |

NDEWS Coordinating Center, NDEWS New Hampshire HotSpot Report, October 14, 2016, https://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/pubs/newhampshirehotspotreportphase1final.pdf. |

| 17. |

Not all controlled prescription drugs (CPDs) are opioids. For example, amphetamine is included in the CPD category. |

| 18. |

Drug Enforcement Administration, 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary, November 2016, https://www.dea.gov/resource-center/2016%20NDTA%20Summary.pdf. |

| 19. |

Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Budget, May 2017, p. 19. |

| 20. |

U.S. Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center, National Drug Threat Assessment 2005, February 2005. |

| 21. |

One such doctor was David Procter, who established a pill mill operation from 1992 through 2001 in South Shore, KY. He is viewed as the "godfather of pills." NPR, "How Heroin Made its Way From Rural Mexico to Small-Town America," May 19, 2015. |

| 22. |

"Pill mill" is a term used to describe a doctor, clinic, or pharmacy that is prescribing or dispensing narcotics inappropriately or for non-medical reasons. They may be disguised as independent pain-management centers. They tend to open and shut down quickly to evade law enforcement. |

| 23. |

For more information on prescription drug monitoring programs, see CRS Report R42593, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. |

| 24. |

In response to the problem of rogue Internet websites that illegally sell and dispense controlled prescription drugs, Congress passed the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-425), which amended the Controlled Substances Act to expressly regulate online pharmacies. For more information, see CRS Report R43559, Prescription Drug Abuse. |

| 25. |

FDA approved the reformulation of OxyContin® to make it harder to crush and abuse. FDA also required a label warning of its addictive quality. |

| 26. |

On August 22, 2014, the Drug Enforcement Administration published a final rule in the Federal Register that administratively reschedules hydrocodone combination products from Schedule III to Schedule II, which subjects anyone who manufactures, distributes, or dispenses hydrocodone combination products to the more stringent regulatory requirements and administrative, civil, and criminal sanctions that are applicable to Schedule II controlled substances. For more information on these actions, see CRS Report R43559, Prescription Drug Abuse. |

| 27. |

HHS, NIH, NIDA, Prescription Drugs and Heroin, December 2015; Pradip K. Muhuri, Joseph C. Gfroerer, and M. Christine Davies, Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States, HHS, SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, August 2013, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DataReview/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.pdf; Theodore J. Cicero, Matthew S. Ellis, and Hilary L. Surratt, "Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of Oxycontin," New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 367, no. 2 (July 12, 2012), pp. 187-189; DOJ, NDIC, National Drug Threat Assessment 2003, "Narcotics", January 2003; and DOJ, NDIC, National Drug Threat Assessment 2011, August 2011, p. 37. |

| 28. |

HHS, NIH, NIDA, Prescription Drugs and Heroin, December 2015, pp. 4-5. |

| 29. |

Heroin has several different forms, including black tar, brown powder, and white powder. For more information, see DEA, Drugs of Abuse, 2015 Edition, p. 38. |

| 30. |

DOJ, NDIC, National Drug Threat Assessment 2005, February 2005. |

| 31. |

Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy, The Price and Purity of Illicit Drugs: 1981 Through the Second Quarter of 2003, November 2004, p. 11. |

| 32. |

DEA, 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary, November 2016. |

| 33. |

Fentanyl and fentanyl compounds such as acetyl fentanyl and carfentanil are synthetic opioids with varying levels of potency. Fentanyl is a Schedule II narcotic and approved by the FDA. While some pharmaceutical fentanyl is diverted from legitimate use, illicit, non-pharmaceutical fentanyl is the largest fentanyl threat in the United States. For more information, see DEA, Fentanyl, https://www.dea.gov/druginfo/fentanyl.shtml. |

| 34. |

Gray death is a new illicit synthetic opioid mix that is reportedly 10,000 times more powerful than morphine. The formulations of seized samples have varied. |

| 35. |

DEA, 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary, November 2016. |

| 36. |

Ibid. |

| 37. |

HHS, CDC, Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2010–2015, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, December 30, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm. |

| 38. |

Ibid., pp. 156 and 158. |

| 39. |

Diversion control involves efforts to prevent, detect, and investigate the diversion of controlled substances from legitimate sources while ensuring an adequate supply for legitimate use. |

| 40. |

For a detailed look at agencies that conduct federal drug control activities, see the most recent budget summary from ONDCP: Office of National Drug Control Policy, FY2016 Budget and Performance Summary, December 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/fy2017_budget_summary-final.pdf. |

| 41. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44860, SAMHSA FY2018 Budget Request and Funding History: A Fact Sheet. |

| 42. |

Tribal entities eligible for SAMHSA-administered grants may include tribal governments and nongovernmental organizations. For more information, see CRS Report R44634, Behavioral Health Among American Indian and Alaska Natives: An Overview. |

| 43. |

HHS, NIH, NIDA, 2016-2020 NIDA Strategic Plan: NIDA's Mission, https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/strategic-plan/nidas-mission. |

| 44. |

For the actual and estimated extramural research funding (in recent years, the current year, and the coming year), see the row for "Drug Abuse (NIDA Only)" at HHS, NIH, Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC), at https://report.nih.gov/categorical_spending.aspx. |

| 45. |

Medically underserved populations, as designated by HRSA, may include those who are homeless, low-income, Medicaid-eligible, Native American, or migrant farmworkers (among others). See HHS, HRSA, Medically Underserved Areas and Populations (MUA/Ps), https://bhw.hrsa.gov/shortage-designation/muap. |

| 46. |

To find SAMHSA's grant announcements for the current fiscal year, grant awards by state, and other information about SAMHSA's grant programs, see https://www.samhsa.gov/grants. |

| 47. |

For opioid-focused programs administered by SAMHSA, CRS included SAMHSA's two largest substance abuse treatment programs, its criminal justice activities, and programs of regional and national significance (PRNS) that explicitly refer to opioids. For opioid-focused programs administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), see HHS, CDC, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, pp. 330-333. For opioid-focused programs administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration, see HHS, HRSA, "HRSA Awards $200 Million to Health Centers Nationwide to tackle Mental Health and Fight the Opioid Overdose Crisis," press release, September 14, 2017. |

| 48. |

The tribal entity is the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, which applies for SABG funds separately from the state of Minnesota; other tribal entities may receive a portion of SABG funds through the states in which they are located. |

| 49. |

Public Health Service Act (PHSA) §1932(b) (42 U.S.C. §300x-32(b)). |

| 50. |

PHSA §1922(a)(1) (42 U.S.C. §300x-22(a)(1)). |

| 51. |

The State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis grant program is authorized by Section 1003 of the 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255). |

| 52. |

HHS, SAMHSA, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, p. 207. |

| 53. |

The First Responder Training program is authorized by Section 202 of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA, P.L. 114-198). |

| 54. |

HHS, SAMHSA, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, p. 152; and SAMHSA, Individual Grant Awards, https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017. For more information see, CRS In Focus IF10741, Naloxone for Opioid Overdose: Regulation and Policy Options. |

| 55. |

Naloxone is a drug (an opioid antagonist) that can reverse opioid overdose by blocking the effects of other opioids. The Improving Access to Overdose Treatment grant program is authorized by Section 107(a) of CARA. For award information, see SAMHSA, Individual Grant Awards, https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017. |

| 56. |

HHS, SAMHSA, Improving Access to Overdose Treatment, Funding Opportunity Announcement No. SP-17-006. |

| 57. |

HHS, SAMHSA, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, p. 180. For award data, see SAMHSA, Individual Grant Awards, https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017. |

| 58. |

The Pregnant and Postpartum Women program is reauthorized and amended by Section 501 of CARA. |

| 59. |

"Recovery community organizations" are nonprofit organizations that mobilize resources to increase long-term recovery from substance use disorders and are governed by people in recovery. The Building Communities of Recovery grant program is authorized under Section 547 of the Public Health Service Act, as amended by Section 302 of CARA. For award data, see SAMHSA, Individual Grant Awards, https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2017. |

| 60. |

HHS, SAMHSA, Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act: Building Communities of Recovery, Funding Opportunity Announcement No. TI-17-015. |

| 61. |

For more information on drug courts, see CRS Report R44467, Federal Support for Drug Courts: In Brief. |

| 62. |

For more information on Treatment Drug Court grants and the Offender Reentry Program, see HHS, SAMHSA, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, pp. 194-200. |

| 63. |

HHS, CDC, Opioid Overdose: Prevention for States, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/states/state_prevention.html. |

| 64. |

HHS, CDC, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, pp. 330-333. |

| 65. |

HHS, CDC, FY2018 Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, pp. 330-333. |

| 66. |

HHS, HRSA, Rural Health Funding Opportunities, https://www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/programopportunities/fundingopportunities/. |

| 67. |

Ibid. |

| 68. |

The majority of drug crimes known to U.S. law enforcement are dealt with at the state level. For a broader discussion of domestic drug enforcement, see CRS Report R43749, Drug Enforcement in the United States: History, Policy, and Trends. |

| 69. |

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA), enacted as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-513), placed the control of select plants, drugs, and chemical substances under federal jurisdiction. |

| 70. |

For more details on the CSA regulatory requirements, see CRS Report RL34635, The Controlled Substances Act: Regulatory Requirements. |

| 71. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Improving Predictability and Transparency in DEA and FDA Regulation, Statement of Joseph T. Rannazzisi, Deputy Assistant Administrator, Office of Diversion Control, Drug Enforcement Administration, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., April 7, 2014, p. 1. |

| 72. |

Under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), there are five schedules under which substances may be classified—Schedule I being the most restrictive. Substances placed onto one of the five schedules are evaluated on potential for abuse, current scientific knowledge of the substance, risk to public health, and several other criteria. Of the more well-known opioids, heroin is categorized as a Schedule I drug, while oxycodone and hydrocodone have recognized medical use and are categorized as Schedule II. Per the CSA and regulation, the DEA establishes quotas to limit the quantity of Schedule I and II controlled substances that may be produced in a given calendar year. For more information on CSA regulations, see CRS Report RL34635, The Controlled Substances Act: Regulatory Requirements. |

| 73. |

See 21 C.F.R. §1301.36 and §1301.37. The DEA Administrator may issue an immediate suspension order that suspends a registrant's DEA registration and may do so simultaneously with an order to show cause proceeding if the continued registration (pending the administrative proceeding) would pose an imminent danger to the public health or safety. |

| 74. |

§201, P.L. 114-198. |

| 75. |

For more information on these solicitations and the Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Site-based Program, see U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Frequently Asked Questions about the Office of Justice Programs (OJP) Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Site-based and Training and Technical Assistance Grant Programs, February 2017, https://www.bja.gov/programs/CARA_FAQs_2.13.2017-Final.pdf. |

| 76. |

For more information on PDMPs, see CRS Report R42593, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. |

| 77. |

For more information on law enforcement use of PDMP data, see CRS Report R42593, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs. |

| 78. |

DOJ, Office of Community Policing Services, Fact Sheet: 2016 COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program, 2016, https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/2016AwardDocs/ahtf/FactSheet.pdf. |

| 79. |

See 34 U.S.C. §§10151-10152. For more information on the JAG program, see CRS Report RS22416, Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program: In Brief; and CRS In Focus IF10691, The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) Program. |

| 80. |

For more information on drug courts, see CRS Report R44467, Federal Support for Drug Courts: In Brief. |

| 81. |

34 U.S.C. §§10611-10619. |

| 82. |

See 34 U.S.C. §11131. |

| 83. |

34 U.S.C. §11311. |

| 84. |

Executive Office of the President, ONDCP, President Trump's First Budget Commits Significant Resources to Fight the Opioid Epidemic, May 23, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/05/23/president-trumps-first-budget-commits-significant-resources-fight-opioid. |

| 85. |

See Executive Office of the President, ONDCP, President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/presidents-commission. |

| 86. |

Executive Order, "Presidential Executive Order Establishing the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis," March 29, 2017. |

| 87. |

See 21 U.S.C. §1706. |

| 88. |

DEA, High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTAs), https://www.dea.gov/ops/hidta.shtml. |

| 89. |

Ibid. |

| 90. |

See 21 U.S.C. §1531 et seq. |