Pre-Merger Review and Challenges Under the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act

Preserving competition is an overarching purpose of federal laws governing business mergers. Though other federal laws, including the Sherman Act, seek to address anticompetitive behavior relating to monopolization, two federal statutes, in particular, address harms that may result from proposed mergers. Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers “in any line of commerce or in any activity affecting commerce” that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act) prohibits unfair methods of competition, which includes any activity that violates Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

Pursuant to the Clayton and FTC Acts, Congress authorized the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to determine whether a proposed merger would substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. Title II of the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act (HSR Act) requires transacting parties, which exceed certain sizes, to report significant planned mergers and acquisitions to the FTC and DOJ so that the agencies may determine whether the proposed transactions raise anticompetitive concerns. If the FTC or DOJ determines that such concerns exist, the agencies may commence administrative or judicial proceedings to block the proposed transaction. Reviewing courts and administrative law judges consider a variety of factors when determining whether a proposed merged complies with federal antitrust laws.

This report examines the primary statutes and processes that govern federal pre-merger review and merger challenges.

Pre-Merger Review and Challenges Under the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Pre-Merger Review: Application of the Clayton Act and FTC Act

- The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act and the Pre-Merger Review Process

- Substantive Review of Proposed Mergers by the FTC and the DOJ

- Mergers Within the Same Industry (Horizontal Mergers)

- Product Markets

- Geographic Markets

- Evaluation of Potential Harms

- Market Entry, Efficiencies, and Other Considerations

- Mergers in Related Industries (Vertical Mergers)

- Potential Actions Following Completion of the Pre-Merger Review Process

- Merger Challenges by the DOJ

- Merger Challenges By the FTC

- Conclusion

Summary

Preserving competition is an overarching purpose of federal laws governing business mergers. Though other federal laws, including the Sherman Act, seek to address anticompetitive behavior relating to monopolization, two federal statutes, in particular, address harms that may result from proposed mergers. Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits mergers "in any line of commerce or in any activity affecting commerce" that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act) prohibits unfair methods of competition, which includes any activity that violates Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

Pursuant to the Clayton and FTC Acts, Congress authorized the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to determine whether a proposed merger would substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. Title II of the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act (HSR Act) requires transacting parties, which exceed certain sizes, to report significant planned mergers and acquisitions to the FTC and DOJ so that the agencies may determine whether the proposed transactions raise anticompetitive concerns. If the FTC or DOJ determines that such concerns exist, the agencies may commence administrative or judicial proceedings to block the proposed transaction. Reviewing courts and administrative law judges consider a variety of factors when determining whether a proposed merged complies with federal antitrust laws.

This report examines the primary statutes and processes that govern federal pre-merger review and merger challenges.

Introduction

Pursuant to the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act), Congress charged the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) with reviewing whether proposed mergers comport with federal antitrust laws and preventing anticompetitive mergers.1 This report discusses statutes governing federal pre-merger review,2 along with DOJ and FTC guidelines for assessing whether a proposed merger complies with statutory requirements. This report also discusses the DOJ's and FTC's processes for challenging a merger prior to its consummation.

Pre-Merger Review: Application of the Clayton Act and FTC Act

While other federal laws, including the Sherman Act, seek to deter anticompetitive harms caused by monopolization and agreements to restrain trade,3 two federal statutes, the Clayton and the FTC Acts, relate particularly to proposed mergers. Section 7 of the Clayton Act applies to mergers "in any line of commerce" when their effect "may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly" unless the merger is statutorily exempt. 4 Section 5 of the FTC Act5 prohibits unfair methods of competition and includes any activity that violates Section 7 of the Clayton Act.6 The FTC generally applies standards similar to DOJ's when assessing transactions under Section 7 of the Clayton Act pursuant to Section 5 of the FTC Act.7

By prohibiting mergers that negatively affect competition,8 the Clayton and FTC Acts aim to preserve rather than enhance competition9 and to protect overall market competition rather than individual competitors.10 Accordingly, mergers may injure market competitors but not violate antitrust laws.11 Moreover, because Section 7 of the Clayton Act and Section 5 of the FTC Act aim to prevent anticompetitive harms from occurring, they look to the likelihood of future harm.12 To violate these statutes, therefore, the transaction must be likely, rather than certain, to have an anticompetitive effect.13

The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act and the Pre-Merger Review Process

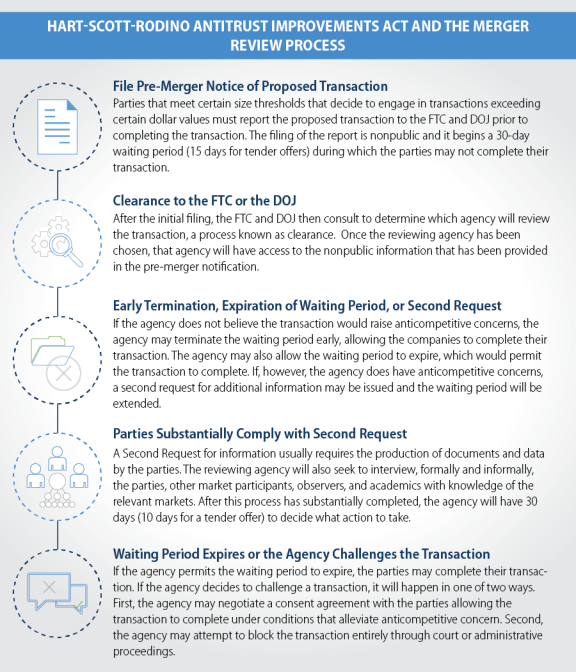

The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act (HSR Act) requires businesses exceeding certain sizes to report proposed mergers and other transactions valued above specified thresholds14 to the DOJ and FTC so that the agencies may examine whether those transactions comply with federal antitrust laws.15 Businesses may only complete the proposed merger once the statutory waiting period has expired (typically 30 days after filing the report, but 15 days in the case of a cash tender offer, or such other time if the agency shortens or extends the waiting period).16 If the agency determines that the merger would be likely to lessen competition substantially, the agency may either negotiate with the transacting parties to address its concerns or act to block the merger.17

As part of the notice filed under the HSR Act, the transacting parties must provide certain non-public information to the agencies, including (1) information about themselves, including their balance sheets; (2) information related to the proposed transaction's planning and execution; and (3) information regarding the product, service, and geographic markets in which they operate.18 Information submitted during the process is exempt from the Freedom of Information Act and the agency cannot make it public except in the course of an administrative or judicial proceeding.19

Upon reviewing the pre-merger notification, the DOJ or FTC seeks clearance from the other agency to investigate the transaction.20 When both agencies request clearance, the agency with the most expertise in reviewing transactions in the relevant markets generally conducts the investigation21 subject to jurisdictional limitations.22 The agency selected to investigate the proposed merger reviews information provided by the transacting parties and other market participants.23 Prior to the expiration of the 30-day waiting period, the reviewing agency decides whether (1) to issue a second request for more information or (2) to allow the transaction to complete, either by terminating the waiting period early or by letting the waiting period expire without taking further action.24 If the parties voluntarily withdraw their filing and subsequently refile, the required waiting period restarts.25

If, during the initial waiting period, the reviewing agency needs additional information to assess whether the prospective merger complies with antitrust laws, the agency may require the transacting parties to provide further information and documents (commonly referred to as the "Second Request").26 The reviewing agency may also gather evidence from entities that are not transacting parties.27 For example, the agency may interview, either informally or under oath, customers and other market participants or seek information from industry observers and academics.28

Once the parties have substantially complied29 with the Second Request, the reviewing agency has 30 days (or 10 days, in the case of a cash tender offer) to review the information and decide how to proceed.30 If parties fail to comply substantially with the Second Request, the reviewing agency may request a federal district court to order compliance and to extend the waiting period during the time it takes to reach substantial compliance.31 If the waiting period expires, the parties may complete the transaction.32 Depending upon the merger's complexity, a significant amount of time might pass between the reviewing agency's issuance of a Second Request and a final decision.33

A summary of the clearance process is depicted in Figure 1.

|

|

Source: 15 U.S.C. § 18a. |

Substantive Review of Proposed Mergers by the FTC and the DOJ

The FTC and DOJ employ shared guidelines to assess whether a proposed merger is permissible under the FTC and Clayton Acts.34 These standards apply to various types of transactions, including mergers between competing entities or potentially competing entities in a relevant market (horizontal mergers) and mergers between non-competing entities that operate within related industries (vertical mergers).35 Because horizontal and vertical mergers raise somewhat different competitive concerns, they are discussed separately below.

Mergers Within the Same Industry (Horizontal Mergers)

The FTC and DOJ use the Horizontal Merger Guidelines ("Guidelines") when reviewing whether a proposed merger between competitors raises anticompetitive concerns under the Clayton and FTC Acts.36 The Guidelines adopt "a fact-specific process through which the [FTC or DOJ], guided by their extensive experience, apply a range of analytical tools to the reasonably available and reliable evidence to evaluate competitive concerns in a limited period of time."37 The Guidelines primarily examine whether a proposed merger would unduly enhance the transacting parties' "market power," which is a firm's ability, without causing economic harm to itself, to raise prices, reduce output, reduce innovation, or otherwise harm consumers.38 The agencies view a proposed merger's probable enhancement of market power as increasing the likelihood that the merger will substantially lessen competition. To identify lines of commerce and geographic areas that the merger may affect and gauge its impact on the transacting parties' market power, a reviewing agency, assessing a horizontal merger under the Clayton or FTC Act, first defines the relevant product and geographic markets.39

Product Markets

A "product market" consists of "all products 'reasonably interchangeable by consumers for the same purposes.'"40 To identify product markets that the merger would affect, the reviewing agency generally employs the "Hypothetical Monopolist Test," which examines whether consumers in the market would be able to switch from one product to a close substitute in response to a small but significant price increase or benefit reduction. 41 If consumers could switch products, the agency next considers whether they could do so in sufficient numbers to render any price increase or benefit reduction unprofitable to the responsible party.42 If a sufficient number of consumers would likely switch from one product to another, the agency might find those products to belong to the same product market.43

The DOJ's 2016 suit to block Deere and Company's ("John Deere") acquisition of Monsanto, Co.'s Precision Planting ("Precision Planting") subsidiary illustrates how a reviewing agency defines a product market.44 In this suit, the DOJ defined the relevant product market as high-speed precision planting systems that were factory-installed on new planters or retrofitted on existing planters.45 The DOJ argued that other types of planting systems were not "effective substitutes" for high-speed systems, making it unlikely that high-speed planting systems users would switch to those alternatives, even if prices for high-speed systems rose significantly.46

In another recent case, the DOJ sued to block the proposed merger of Aetna, Inc. and Humana, Inc.—two large health insurance companies that offer Medicare Advantage plans, which provide benefits akin to traditional Medicare benefits along with other benefits.47 The DOJ concluded that the proposed Aetna-Humana merger would affect the market for Medicare Advantage policies.48 The DOJ found, however, that traditional Medicare was not part of the relevant market because the DOJ believed that, given a small but significant Medicare Advantage plan price increase or benefit reduction, seniors enrolled in those plans would be unlikely to switch to traditional Medicare in sufficient numbers.49 The district court agreed, finding that Medicare Advantage policies, but not traditional Medicare, constituted the relevant market.50

Geographic Markets

With respect to the relevant geographic markets, the Supreme Court has stated: "Congress prescribed a pragmatic, factual approach to the definition of the relevant market and not a formal legalistic one. The geographic area selected must, therefore, both correspond to the commercial realities of the industry and be economically significant."51 Depending on the products and services at issue, a reviewing agency could identify the geographic market as the entire United States or a smaller region.52 For instance, when DOJ reviewed John Deere's proposed acquisition of Precision Planting, the agency found the sale of high-speed precision planting systems to be a national market.53 For the Aetna-Humana merger, DOJ defined the relevant geographic markets as "hundreds of counties across the United States" where Aetna and Humana compete to enroll seniors in Medicare Advantage plans.54

Measuring Market Power

After defining the relevant market, the reviewing agency identifies the market participants, their market shares, and the level of market concentration.55 A reviewing agency typically begins a market-power assessment by comparing existing market concentration with the likely concentration following the merger.56 To measure market concentration, reviewing agencies typically employ the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), which is calculated by "summing the squares of individual firms' market shares."57 Some U.S. courts also rely on HHI calculations to assess whether a transaction would create market power.58 Under the Merger Guidelines, the DOJ and FTC presumptively deem transactions that increase a market's HHI by 200 or more points and result in the HHI being above 2500 (a highly concentrated market) to lessen competition substantially.59 However, "[t]he presumption may be rebutted by persuasive evidence" that the transaction likely would not have anticompetitive consequences.60

Evaluation of Potential Harms

In addition to considering market concentration impacts, the FTC and DOJ might consider the market impacts of other factors in the transaction61 as discussed below.62

Potential Effects on Pricing

Because mergers reduce the number of market participants, a merged entity, facing less competition, might be more likely to engage in behavior harmful to consumers, such as raising prices.63 If consumers treat the transacting parties' products as substitutes, a reviewing agency might be concerned that the merged entity could behave anti-competitively.64 To illustrate, when the DOJ sued to block Anthem, Inc., from acquiring competing health insurance provider, Cigna, Corp, the DOJ argued that the companies competed head-to-head to sell insurance to employers with more than 5,000 employees in the national market and in fourteen state markets, and were often finalists in competitive bidding.65 The DOJ further contended that the merger, by eliminating competition between the two companies, would encourage the merged entity to raise prices unilaterally above otherwise competitive levels.66

Potential Effects on Product Output

The reviewing agency might also consider whether, in markets with largely homogenous products, a merged entity would have incentives either to suppress its output by slowing production or to reduce its production capacity in order to elevate prices.67 For example, a merged entity might reduce the excess capacity of one of its components, which pre-merger had been constraining a rise in market prices. 68 The merger might also provide the merged entity with a larger sales base, increasing the benefits of a price hike caused by reducing output.69 The Merger Guidelines provide an illustrative example of how a merged entity might reduce product output and thereby increase prices for consumers:

Firms A and B both produce an industrial commodity and propose to merge. The demand for this commodity is insensitive to price. Firm A is the market leader. Firm B produces substantial output, but its operating margins are low because it operates high-cost plants. The other suppliers are operating very near capacity. The merged firm has an incentive to reduce output at the high-cost plants, perhaps shutting down some of that capacity, thus driving up the price it receives on the remainder of its output. The merger harms customers, notwithstanding that the merged firm shifts some output from high-cost plants to low-cost plants.70

Potential Effects on Innovation

A reviewing agency may also consider a merger's potential effects on innovation.71 It may find that "combining two of a very small number of firms with the strongest capabilities to successfully innovate in a specific direction" hinders innovation in the market.72 For example, when the DOJ reviewed Dow Chemical's ("Dow") proposed merger with E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company ("DuPont"), it observed that Dow and DuPont competed head-to-head in producing and selling certain herbicides and that DuPont had recently introduced a new herbicide that competed directly with one marketed by Dow.73 The agency found that competition between the two companies had "spurred research, development and marketing of new and improved" products and that the merger would eliminate such competition.74 Ultimately, DuPont agreed to divest its market-leading herbicide to address the DOJ's competition concerns.75 In another example, the DOJ cited potential negative impacts on innovation when it opposed AT&T, Inc.'s ("AT&T") proposed acquisition of T-Mobile US ("T-Mobile").76 Because T-Mobile competed with AT&T in innovation, the DOJ cited T-Mobile's potential loss as a primary reason for seeking an injunction.77

Coordination Among Firms

A reviewing agency may also examine whether a merger would unacceptably magnify market participants' opportunities for coordinated interaction, which is "conduct by multiple firms that is profitable for each of them only as a result of the accommodating reactions of others."78 One example of coordinated interaction is parallel action, which is when one market participant raises prices (or makes some other change), and other market participants take the same action in lockstep.79 In considering the risk of coordinated interaction, the FTC and DOJ generally take the view that the fewer participants in a given market, the more likely they are to engage in parallel action following a merger.80

For example, when the DOJ challenged AT&T's proposed acquisition of T-Mobile, the agency identified the potential for coordinated interaction as a reason to block the transaction.81 The DOJ claimed that, if AT&T acquired T-Mobile, the number of nationally competitive wireless service providers would decrease from four to three.82 The DOJ contended that T-Mobile's strategy of positioning its service as a lower-priced alternative to services offered by AT&T and other major service providers constrained AT&T and the other providers from increasing their prices.83 The DOJ asserted that eliminating T-Mobile as a competitor might lead the remaining competitors to coordinate, resulting in higher prices nationwide for wireless services.84 Similarly, the FTC was concerned that H.J. Heinz, Co.'s proposed merger with Beech-Nut Nutrition Corp. might lead the remaining major baby food producers to coordinate their behavior and raise prices above competitive levels.85

Market Entry, Efficiencies, and Other Considerations

In assessing a proposed merger's anticompetitive effect, the reviewing agency may also consider factors that support the transaction. The ability of other competitors to enter the market indicates the degree to which the merged entity could constrain behavior and pricing within that market.86 Easy market entry suggests that a proposed merger is less likely to reduce market competition, while significant barriers to entry, such as the need to engage in lengthy research and development or obtain regulatory approvals, suggests that a proposed merger would be more likely to reduce market competition.87

Additionally, the DOJ and FTC recognize that "a primary benefit of mergers to the economy is their potential to generate significant efficiencies and thus enhance the merged firm's ability and incentive to compete[.]"88 Greater efficiency could provide benefits such as cost-reduction or increased services,89 potentially offsetting anticompetitive concerns raised by the merger provided, however, that "[t]he greater the potential adverse competitive effect of a merger, the greater must be the cognizable efficiencies, and the more they must be passed through to customers[.]"90To support a proposed merger, the potential market efficiencies must be unlikely to be accomplished by a means other than the merger.91 They must also be reasonably verifiable and cannot "arise from anticompetitive reductions in output or service."92 The reviewing agency might also consider, among other things, whether one of the parties to a proposed merger has failed or is failing (i.e., whether it would soon exit the relevant markets as a competitor even if it did not merge with a competitor).93

Mergers in Related Industries (Vertical Mergers)

The DOJ and FTC also may examine a proposed merger's impact on product and geographic markets in which the transacting parties do not compete, if the transaction may nonetheless have a negative effect on competition in those markets.94 This situation generally arises when a merger would lead to one business entity controlling two or more stages of production and distribution normally done by separate entities—a situation known as vertical integration or a "vertical merger."95 In part because these transactions do not affect competition between actual or potential competitors and they can create competition-enhancing efficiencies,96 the agencies tend to view vertical transactions as less likely to be anticompetitive than horizontal transactions.97

The Horizontal Merger Guidelines, most recently amended in 2010, do not provide guidance on vertical mergers.98 The 1984 Guidelines were the last version to address vertical mergers directly.99 Those guidelines took the view that vertical mergers generally posed a less immediate threat to competition than horizontal mergers, in part because vertical integration involved entities that did not compete at the same level in the market and therefore had no impact on market concentration.100 However, the DOJ and FTC have taken enforcement action against some vertical mergers that the agencies viewed as substantially lessening competition, generally through consent agreements.101 In such cases, the agencies have considered whether the merged entity would have incentives to foreclose competition in part of the market (e.g., by cutting off an important avenue for distribution of a product or service or by eliminating customer access to a product or service) and whether the transaction would increase incentives for coordinated anticompetitive conduct in affected markets, among other factors.102

For instance, Comcast Corp.'s ("Comcast") joint venture involving NBC Universal, Inc. ("NBC") and General Electric Co. ("GE") was a high-profile example of vertical integration.103 In that transaction, Comcast, a powerful distributor of programming content, proposed to engage in a joint venture with GE that would enable Comcast to obtain effective control over NBC, an important programming content provider.104 The DOJ ultimately permitted the transaction, subject to conditions contained in a consent agreement.105 For example, because DOJ was concerned that Comcast could restrict competing online video program distributors from providing their customers access to NBC-owned programming, thereby driving consumers to Comcast's cable services,106 the consent agreement required the joint venture to make its programming available to online video distributers on equivalent terms offered to traditional programming distributors (e.g., other cable providers, satellite providers).107

Potential Actions Following Completion of the Pre-Merger Review Process

Upon completing its review of a proposed merger, the reviewing agency decides whether (1) to permit the merger to consummate; (2) to take any action to block the merger; or (3) to negotiate with the transacting parties to place conditions on the merger's completion that alleviate the agency's anticompetitive concerns.108 The agencies permit most proposed transactions to complete without conditions.109 If the reviewing agency seeks to block a merger,110 the agency may bring an action against the transaction in a judicial and/or administrative proceeding (depending upon whether the DOJ or the FTC is the reviewing agency).111 In these circumstances, the transacting parties may abandon the deal112 or contest the government's case before a federal or administrative law judge.113

Merger Challenges by the DOJ

The DOJ pursues potential violations of the Clayton Act in federal court.114 Section 15 of the Clayton Act vests power to prevent and restrain violations of Section 7 in the federal district courts, and grants the DOJ authority to institute such proceedings.115 The DOJ may initially seek a preliminary injunction to block a merger from proceeding while litigation is ongoing. 116 To shorten the potential duration of litigation, the DOJ and transacting parties often agree to consolidate the motion for a preliminary injunction with a motion for a permanent injunction. 117 To obtain a permanent injunction against a merger, the DOJ must show by a preponderance of the evidence that the proposed transaction would violate the applicable antitrust law118—a higher standard than required to obtain a preliminary injunction.119

In assessing whether a merger violates antitrust laws, the reviewing court is not bound by the DOJ's administrative review determination.120 If the district court denies the DOJ's request for a permanent injunction, the transacting parties may complete the proposed transaction.121 If the DOJ obtains a permanent injunction, which the transacting parties do not challenge or which a court upholds on appeal, the merger may not go forward.122 The DOJ and the transacting parties may also enter into a consent agreement to resolve the dispute. Such agreements might require one or both of the merging parties to divest particular assets or engage in other actions to alleviate potential anticompetitive effects of the transaction.123 When the DOJ has reached a consent agreement with the transacting parties, it will typically file both (1) a motion for an injunction in federal district court; and (2) a proposed consent agreement for approval by the court, along with other documents, such as a Hold Separate Order.124 The Hold Separate Order usually outlines the assets that the transacting parties must keep separate from the merged entity, and the parties must typically sell or spin off these assets into independent companies to alleviate the anticompetitive concerns raised by the merger.125 Once the reviewing court has approved the Hold Separate Order, the transacting parties may generally consummate the merger in accordance with the order's terms.126

Under the Tunney Act (also known as the Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act), the DOJ must file consent agreements to resolve antitrust concerns with a federal court and, at the same time, publish the proposed agreement in the Federal Register for public comment prior to the court entering a judgment.127 The DOJ also must file any written comments related to the proposal with the court and publish them in the Federal Register.128 At the close of the comment period (typically 60 days), the DOJ must file with the court and publish in the Federal Register a response to the comments.129 After the agency has addressed the public comments, the reviewing court may enter a final judgment approving the consent order with the agreed-upon conditions,130 provided that the court finds the consent agreement to be in the public interest.131

Merger Challenges By the FTC

The FTC's process for challenging proposed transactions is different from the DOJ's. Unlike the DOJ, the FTC may use enforcement tools available under the FTC Act in addition to those available under the Clayton Act to challenge proposed mergers.132 And whereas the DOJ process for blocking mergers under the Clayton Act involves seeking injunctive relief in federal district court, the FTC has several administrative and judicial avenues to prevent mergers that violate antitrust laws.133 Under Section 11 of the Clayton Act, the FTC can challenge proposed mergers in most areas of commerce, with some exceptions, via an administrative adjudication that can be appealed to a federal court of appeals.134 The FTC also has administrative processes available to review proposed mergers that may be unfair methods of competition under Section 5(b) of the FTC Act.135 Section 13(b) of the FTC Act further provides the FTC authority to request a court to enjoin, preliminarily and permanently, activities that would violate the statutes the FTC administers.136

When the FTC decides to challenge a proposed merger and has not reached a consent agreement with the transacting parties, the agency typically files a motion for a preliminary injunction under Section 13(b) of the FTC Act in federal court alleging that the transaction would violate both Section 7 of the Clayton Act and Section 5 of the FTC Act.137 Section 13(b) of the FTC Act requires courts to issue preliminary injunctions "[upon] a proper showing that weighing the equities and considering the Commission's likelihood of ultimate success, such action would be in the public interest[.]"138

Around the same time that it files a motion for a preliminary injunction, the FTC will often commence administrative proceedings under the FTC and Clayton Acts by issuing a complaint and beginning proceedings before an FTC administrative law judge (ALJ)139 to determine whether the proposed transaction would violate federal law and any remedies.140 If the federal district court grants the preliminary injunction, the transacting parties may not complete the transaction during the administrative proceedings.141 The FTC has the option to continue administrative review of a merger even if the court denies its motion for a preliminary injunction and the transaction closes.142 However, if the court denies the FTC's request for a preliminary injunction, FTC rules require the administrative proceedings to be automatically stayed while the FTC determines whether to continue.143

The Federal Trade Commissioners review all ALJ initial decisions when the agency has also filed a motion for a preliminary injunction in federal court.144 When reviewing an ALJ's initial decision, the FTC staff and the parties provide briefs to the Commission and the Commission may hear oral arguments before issuing a final decision.145 If the Commission decides that a transaction would substantially lessen competition, the parties have the option to appeal to a federal appellate court "within whose jurisdiction the respondent resides or carries on business or where the challenged practice was employed."146 If the parties decide not to appeal, the litigation ends and the parties cannot complete the transaction.147

In practice, the FTC may use both judicial and administrative processes to challenge proposed transactions, but it typically uses only administrative processes when it enters consent agreements with transacting parties because Congress has granted the Federal Trade Commissioners authority to approve consent agreements.148 If a consent agreement is reached, the FTC publishes the proposed complaint, the proposed consent agreement, and an analysis of the proposed consent agreement for public comment149 for a period of 30 days.150 The Federal Trade Commissioners rule on the consent agreement.151

Because consent agreements involving mergers may require divestitures, such agreements may involve Hold Separate Orders, requiring the parties to keep certain assets separate after completing their transaction. If the consent agreement involves a Hold Separate Order, the Commission may issue (i.e., vote to approve as opposed to merely publish) the complaint and the Hold Separate Order when it publishes the proposed consent agreement for comment.152 Following the public comment period and any resulting adjustments to the consent agreement, the final decision and consent agreement may be submitted to the Commission for approval.153 If the Commission approves, the FTC generally issues a complaint, if it has not already done so, and a Final Decision and Order, which incorporates the consent agreement and ends the proceedings.154

Conclusion

Federal antitrust law prohibits mergers and acquisitions that may substantially lessen competition. As the primary federal agencies charged with enforcing federal antitrust laws, the DOJ and FTC follow a congressionally mandated process that requires parties exceeding certain sizes to notify the agencies of sizable transactions so that one of the agencies may determine whether the planned transaction would violate antitrust laws. Highly fact-specific, the DOJ and FTC apply Section 7of the Clayton Act and Section 5 of the FTC Act, respectively, by assessing the proposed transaction's likely impact on competition within relevant markets identified by the agencies. After examining any evidence, the agencies may permit the transaction to proceed, negotiate with the parties to reach an agreement that alleviates antitrust concerns, or block the transaction.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a (giving the DOJ and the FTC authority to review mergers required to be reported prior to completion); id. § 21 (granting the FTC authority to prevent mergers that would substantially lessen competition via adjudication); id. § 25 (granting the DOJ authority to seek preliminary and permanent injunctions of mergers before their completion from a federal court); id. § 45 (granting the FTC authority to proceed administratively against unfair methods of competition); id. § 53(b) (granting the FTC authority to seek a preliminary or permanent injunction against any practice that may violate any statute overseen by the FTC). Section 7 of the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 ("Clayton Act"), as amended, applies to any acquisition of stock or assets within interstate commerce within the United States. 15 U.S.C. § 18. It encompasses mergers as well as acquisitions of some or all of the stock or assets of one entity by another. United States v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours, & Co., 353 U.S. 586, 588 (1957) ("Section 7 is designed to arrest in its incipiency not only the substantial lessening of competition from the acquisition by one corporation of the whole or any part of the stock of a competing corporation, but also to arrest in their incipiency restraints or monopolies in a relevant market which, as a reasonable probability, appear at the time of suit likely to result from the acquisition by one corporation of all or any part of the stock of any other corporation. ... Acquisitions solely for investment are excepted, but only if, and so long as, the stock is not used by voting or otherwise to bring about, or in attempting to bring about, the substantial lessening of competition."). For purposes of this report, the word "merger" will encompass all transactions to which the Clayton Act applies. |

| 2. |

These statutes are Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act ("Sherman Act"), 15 U.S.C. §§1-2, Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18; Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act ("FTC Act"), 15 U.S.C. § 45, and the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976 ("HSR Act"), 15 U.S.C. § 18a. |

| 3. |

Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1-2, prohibit unreasonable restraints on trade and monopolization, and may also apply to proposed transactions. See U.S. Dep't of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm'n, Horizontal Merger Guidelines § 1(2010) [hereinafter "Merger Guidelines"], https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010. At the time of its 1914 enactment, Section 7 of the Clayton Act primarily addressed stock acquisitions. 38 Stat. 730, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 18 (1946). In 1950, Congress expanded Section 7's scope to encompass both stock and asset acquisitions and clarified that it covered all types of transactions, whether between direct competitors or otherwise. See Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 317 (discussing the legislative history of the Section 7 amendments). With Section 7, Congress sought to "arrest restraints of trade in their incipience and before they develop into full-fledged restraints violative of the Sherman Act." S. Rep. No. 1771, at 6 (1950) (emphasis added). For that reason, Section 7 is generally applied to mergers prior to their completion. See Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 323 (noting that "[s]tatutes existed for dealing with clear-cut menaces to competition ... [m]ergers with a probable anticompetitive effect were to be proscribed by [Section 7]"). |

| 4. |

15 U.S.C. § 18. Private parties and state attorneys general may also bring actions under Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Id. § 26; California v. American Stores Co., 495 U.S. 271 (1990) (recognizing a state's ability to obtain divestitures as a remedy under the Clayton Act). |

| 5. |

15 U.S.C. § 45. |

| 6. |

See FTC v. Motion Picture Advert. Serv. Co., 344 U.S. 392, 394-95 (1953) ("It is also clear that the Federal Trade Commission Act was designed to supplement and bolster the Sherman Act and the Clayton Act – to stop in their incipiency acts and practices which, when full blown, would violate those Acts, as well as to condemn as 'unfair methods of competition' existing violations of them.") (internal citations omitted). |

| 7. |

See Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1 (explaining that the Guidelines outline analytical techniques applicable to the Sherman Act, Clayton Act, and FTC Act, and that the Clayton Act is of most particular relevance); Statement of Enforcement Principles Regarding "Unfair Methods of Competition" Under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, 80 Fed. Reg. 57,056 (2015) (explaining that the FTC will only use its Section 5 authority alone if enforcement under the Sherman Act or Clayton Act would not be sufficient). |

| 8. |

Under the Sherman and Clayton Acts, "persons" include natural persons and "corporations and associations existing under or authorized by the laws of either the United States, the laws of any Territories, the laws of any State, or the laws of any foreign country." 15 U.S.C. § 12. The Sherman and Clayton Acts apply to businesses wholly owned and operated in the United States as well as to businesses organized under a foreign country's laws, having their primary base of operation in a foreign country, or owned by a foreign government, provided that such businesses engage in commerce within the United States. Id. § 12. Section 5 of the FTC Act applies to "persons, partnerships, or corporations" with some exceptions. Id. § 45(a). Corporations are defined by the FTC Act to include any company, whether incorporated or unincorporated, "which is organized to carry on business for its own profit or that of its members." Id. § 44. The Sherman, Clayton, and FTC Acts cover "commerce," which includes any trade or commerce activity conducted by persons between the states, territories, the District of Columbia, and foreign nations. Id. §§ 12, 44. |

| 9. |

See Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 320 (1962) ("Taken as a whole, the legislative history [of amendments to Section 7 of the Clayton Act] illuminates congressional concern with the protection of competition, not competitors, and its desire to restrain mergers only to the extent that such combinations may tend to lessen competition.") (emphasis in original);); Merger Guidelines, supra note 3,, § 1 ("The [FTC and DOJ] seek to identify and challenge competitively harmful mergers while avoiding unnecessary interference with mergers that are either competitively beneficial or neutral."). |

| 10. |

Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 320. |

| 11. |

See id. (noting that nothing in the Clayton Act or its legislative history evidences an intent to prohibit the merger of two small companies in order for them to better compete with a larger firm); John Lenore & Co. v. Olympia Brewing Co., 550 F. 2d 495, 500 (9th Cir. 1977) (holding that a private plaintiff did not have standing to sue under the Clayton Act based on harm suffered as a competitor). |

| 12. |

See United States v. Von's Grocery, 384 U.S. 270, 278 (1966) (explaining that Section 7 requires "a prediction of [a transaction's] impact upon competitive conditions in the future"); United States v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours, & Co., 353 U.S. 586, 588 (1957) ("For it is the purpose of the Clayton Act to nip monopoly in the bud."); Motion Picture Advert. Serv., 344 U.S. at 394-95 (stating that Section 5 aimed "to stop in their incipiency acts and practices which, when full blown, would violation [the antitrust laws]"). |

| 13. |

See FTC v. Procter & Gamble, Co., 386 U.S. 568, 577 (1967) ("The core question is whether a merger may substantially lessen competition, and necessarily requires a prediction of the merger's impact on competition, present and future."); Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 323 ("Congress used the words 'may be substantially to lessen competition' (emphasis supplied), to indicate that its concern was with probabilities, not certainties."); Hosp. Corp. of Am. v. FTC, 807 F. 2d 1381, 1389 (7th Cir. 1986) ("Section 7 does not require proof that a merger or other acquisition has caused higher prices in the affected market. All that is necessary is that the merger create an appreciable danger of such consequences in the future."). |

| 14. |

The FTC must revise the reporting thresholds yearly. 15 U.S.C. § 18a(a). Currently, if the size of a transaction exceeds $80.8 million, the transaction must be reported under the HSR Act when one party has net total annual sales or total assets exceeding $16.2 million and the other party has net annual sales or total assets exceeding $161.5 million, and all transactions exceeding a value of $323 million must be reported. 82 Fed. Reg. 8524 (Jan. 26, 2017). |

| 15. |

FTC Premerger Notification Office, Introductory Guide III: To File or Not to File 1 (updated Sept. 2008), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/premerger-introductory-guides/guide2.pdf (observing that the HSR Act was "designed to provide the [FTC and the DOJ] with information about large mergers and transactions before they occur"). |

| 16. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a(b). The statute permits the agencies to end the waiting period early for individual mergers. Id. |

| 17. |

Antitrust Modernization Comm'n, Report And Recommendations 151 (2007), http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/amc/report_recommendation/amc_final_report.pdf [hereinafter "AMC Report"] (Under the system created by the HSR Act, "the agencies are able to challenge mergers before they are consummated, and seek injunctions blocking the merger, partial divestitures that would adequately address the competitive concerns, or other appropriate relief."). |

| 18. |

Id. § 18a(d) (requiring the FTC to issue regulations that specified the form, information, and documentary material required by the notice). The rules for filing and the information and forms required to be filed are located at 16 C.F.R. Pt. 803. |

| 19. |

15 U.S.C.§ 18a(h). This limitation expressly provides that it does not "prevent disclosure to either body of Congress or to any duly authorized committee or subcommittee of the Congress." Id. |

| 20. |

See AMC Report, supra note 17, at 132-35; Am. Bar Assoc. Sec. of Antitrust Law, The Merger Review Process: A Step-by-Step Guide to U.S. and Foreign Merger Review 254-55 (4th ed. 2012) [hereinafter "ABA Merger Review Guide"]; FTC, Premerger Notification and Merger Review Process, https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/mergers/premerger-notification-and-merger (last visited Aug. 21, 2017). For the substantive standard, see infra, "Substantive Review of Proposed Mergers by the FTC and the DOJ". |

| 21. |

ABA Merger Review Guide, supra note 20, at 254-55 ("The greater the expertise or prior dealings that an agency has had with respect to an industry or the specific firms involved in the proposed transaction, the more likely it will be that that agency's request for clearance will ultimately be granted."). |

| 22. |

For example, Section 11 of the Clayton Act does not permit the FTC to enforce the Clayton Act against certain transactions overseen by the Surface Transportation Board, Federal Communications Commission, the Secretary of Transportation, or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 15 U.S.C. § 21. Furthermore, the FTC is prohibited from enforcing Section 5 of the FTC Act against "banks, savings and loan institutions described in section 57a(f)(3) of [Title 15], Federal credit unions described in section 57a(f)(4) of [Title 15], common carriers subject to the Acts to regulate commerce, air carriers and foreign air carriers subject to part A of subtitle VII of title 49, and persons, partnerships, or corporations insofar as they are subject to the Packers and Stockyards Act, 1921, as amended [7 U.S.C. §§ 181, et seq.], except as provided in section 406(b) of said Act [7 U.S.C. 227(b)]." Id. § 45(a). |

| 23. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1. |

| 24. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a(b). |

| 25. |

16 C.F.R. § 803.12 (permitting the voluntary withdrawal and resubmission of notification of a transaction without an additional filing fee); see also AMC Report, supra note 17, at 157. |

| 26. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a(e). In the second request, the agency generally asks for documents and data that will provide the agency with a more granular look at the relevant markets. See 16 C.F.R. § 803.20; FTC Premerger Notification Office, Model Request for Additional Information and Documentary Material (Second Request) (revised Aug. 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/attachments/merger-review/guide3.pdf. |

| 27. |

15 U.S.C. § 18(d)-(e) (allowing the FTC and DOJ to require the submission of materials relevant to evaluating the transaction pursuant to the antitrust laws); see also id. § 46 (granting the FTC the authority to "gather and compile information concerning, and to investigate from time to time the organization, business, conduct, practices, and management of any person, partnership, or corporation engaged in or whose business affects commerce" with certain exceptions); id. § 49 (allowing the FTC to obtain documentary evidence as well as witness testimony); 28 C.F.R.§ 0.40 (creating the Antitrust Division within the DOJ and vesting it with authority to issue and enforce civil investigative demands pursuant to the antitrust laws); Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 2.2 (describing sources of evidence for pre-merger review). |

| 28. |

15 U.S.C. § 18(d)-(e); see also id. § 46; id. § 49; 28 C.F.R.§ 0.40; Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 2.2. |

| 29. |

The HSR Act permits the reviewing agency to extend the waiting period following receipt by the reviewing agencies of "all the information ... required to be submitted pursuant to such request, or [] if such request is not fully complied with, the information and documentary material submitted and a statement of the reasons for such noncompliance." 15 U.S.C. § 18a(e)(2). See also 16 C.F.R. § 803.3 (outlining the information required for statements of noncompliance). |

| 30. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a(e). If this timeline cannot be met, the parties and the reviewing agency may agree to extend the waiting period following substantial compliance with a second request. ABA Merger Review Guide, supra note 20 at 405. |

| 31. |

15 U.S.C. § 18a(e)(2) and (g)(2) (permitting a court to extend the waiting period when parties have failed to substantially comply with second requests). See, e.g., FTC v. McCormick & Co., Inc., No. 88–1128, 1988 WL 43791 at *2 (D.D.C. 1988) (enjoining parties from consummating their merger because they had not yet substantially complied with the FTC's second request for information). |

| 32. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 157 (noting that the parties may not complete their transaction until after substantial compliance with the Second Request and that once substantial compliance has been met and the waiting period has expired the parties are free to complete their transaction). |

| 33. |

See Brent Kendall, U.S. Antitrust Reviews of Mergers Get Longer, Wall St. J. (June 7, 2015), http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-antitrust-reviews-of-mergers-get-longer-1433724741 (discussing data indicating an increase in the average length of transaction reviews where the agencies issued a Second Request from 7 months to 10 months and making note of some transactions in review for over one year). |

| 34. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 47-48. The Merger Guidelines state that they provide an interpretation of the application of the Sherman Act, Clayton Act, and FTC Act to proposed mergers, but opine most particularly upon the Clayton Act. Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1. |

| 35. |

15 U.S.C. § 18. See also Andres I. Gavil, William E. Kovacic, Jonathan B. Baker, Antitrust Law in Perspective: Cases, Concepts and Problems in Competition Policy 418 (2002) (noting that, in addition to horizontal and vertical mergers, there are also conglomerate transactions which involve entities in unrelated lines of business, which may also be reviewed). |

| 36. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1 ("These Guidelines principally describe how the Agencies analyze mergers between rival suppliers[.]"). The most recent Merger Guidelines revision was completed in 2010. See DOJ, Merger Enforcement, https://www.justice.gov/atr/merger-enforcement (last visited Sept. 1, 2017) (showing the previous versions of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines). |

| 37. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1. |

| 38. |

Id. § 1. See also Eastman Kodak v. Image Tech Services, 504 U.S. 451, 464 (1992) (defining market power as "the power to force a competitor to do something he would not otherwise do in a competitive market"). |

| 39. |

Id. § 4. |

| 40. |

City of New York v. Grp. Health Inc., 649 F.3d 151, 155 (2d Cir. 2011) (quoting Geneva Pharm. Tech. Corp. v. Barr Labs. Inc., 386 F.3d 485, 496 (2d Cir. 2004)). See also Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 325 ("The outer boundaries of a product market are determined by the reasonable interchangeability of use or the cross-elasticity of demand between the product itself and substitutes for it."). |

| 41. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 4.1. |

| 42. |

Id. |

| 43. |

See id. ("The hypothetical monopolist test requires that a product market contain enough substitute products so that it could be subject to post merger exercises of market power significantly exceeding that existing absent the merger."). See also Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 325 (1962) (finding it necessary "to examine the effects of a merger in each such economically significant submarket to determine if there is a reasonable probability that the merger will substantially lessen competition"). |

| 44. |

See Shruti Singh and Jack Kaskey, Deere to Buy Precision Planting Unit from Monsanto, Bloomberg (Nov. 3, 2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-03/deere-to-buy-precision-planting-equipment-unit-from-monsanto. |

| 45. |

Compl. at 10-12, United States v. Deere & Co., No. 16 Civ. 08515 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 31, 2016). |

| 46. |

Id. See also Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 325 ("[W]ithin this broad market, well-defined submarkets may exist which, in themselves, constitute product markets for antitrust purposes."). Following the complaint issued by DOJ, John Deere and Monsanto abandoned the deal. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Deere Abandons Proposed Acquisition of Precision Planting from Monsanto (May 1, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/deere-abandons-proposed-acquisition-precision-planting-monsanto. |

| 47. |

Compl. at 9-11, United States v. Aetna, Inc., No. 16 Civ. 01494 (D.D.C. Jul. 21, 2016). |

| 48. |

Id. |

| 49. |

Id. |

| 50. |

United States v. Aetna, Inc., 240 F.Supp.3d 1, 41 (D.D.C. 2017). The district court permanently enjoined the transaction, finding it likely would substantially lessen competition in the market for Medicare Advantage policies in the relevant geographic areas. Id. at 98-99. Following the ruling, the parties abandoned the transaction. David Kleban & Jonathan H. Hatch, A tale of two mergers: Following their losses in DOJ merger challenges, Anthem fights on and Aetna gives up, Antitrust Update (Feb. 17, 2017), https://www.antitrustupdateblog.com/a-tale-of-two-mergers-following-their-losses-in-doj-merger-challenges-anthem-fights-on-and-aetna-gives-up/. |

| 51. |

Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 336. |

| 52. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 4.2. See also Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 336 ("Thus, although the geographic market in some instances may encompass the entire Nation, under other circumstances it may be as small as a single metropolitan area."). |

| 53. |

Compl. at 12, United States v. Deere & Co., No. 16 Civ. 08515 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 31, 2016). |

| 54. |

Compl. at 11, United States v. Aetna, Inc., No. 16 Civ. 01494 (D.D.C. Jul. 21, 2016). All parties agreed that the geographic market should be defined at the county level and the court accepted that definition. Aetna, Inc., 240 F.Supp.3d at 19. |

| 55. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 5. |

| 56. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 5.3. |

| 57. |

Id. The Merger Guidelines identify three general levels of market concentration: (1) unconcentrated markets with HHI below 1500; (2) moderately concentrated markets with HHI of between 1500 and 2500; and (3) highly concentrated markets with HHI above 2500. Id. |

| 58. |

See, e.g., ProMedica Health Sys., Inc. v. FTC, 749 F.3d 559, 570 (6th Cir. 2014) (observing that HHI calculations can suggest that a merger would enhance a business entity's market power); FTC v. H.J. Heinz, Co., 246 F.3d 708, 716 (D.C. Cir. 2001) (stating that an increase in HHI of more than 500 points "creates, by a wide margin, a presumption that the merger will lessen competition"). |

| 59. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 5.3 ("Mergers resulting in highly concentrated markets that involve an increase in the HHI of more than 200 points will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power."). |

| 60. |

Id. For example, the DOJ alleged in its complaint to permanently enjoin the sale of Precision Planting to John Deere that the sale was presumptively anticompetitive because the transaction resulted in an extremely high HHI measure. Specifically, the HHI measure for precision planting system market before the merger, according to the DOJ, was 3,800, indicating an already highly concentrated market. The DOJ predicted that the merger would cause the HHI to "exceed 7,600" – an increase far above the 200 points needed for the transaction to be presumptively anticompetitive. Compl. at 12-16, United States v. Deere & Co, No. 16 Civ. 08515 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 31, 2016). |

| 61. |

See United States v. Gen. Dynamics, 415 U.S. 486, 498 (1974) (indicating that a full examination of a market's "structure, history, and probable future" is needed to assess a merger's probable anticompetitive effect); Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, ("These Guidelines should be read with the awareness that merger analysis does not consist of uniform application of a single methodology."). |

| 62. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 1. |

| 63. |

Id. § 6. |

| 64. |

Id. |

| 65. |

Compl. at 9-14, United States v. Anthem, Inc. and Cigna Corp., No. 16 Civ. 01493 (D.D.C. Jul. 21, 2016). The district court agreed with the DOJ that the merger would substantially lessen competition in the market in fourteen states and issued a permanent injunction against the transaction. United States v. Anthem, Inc., 236 F. Supp. 3d 171, 201 (D.D.C. 2017). The district court decided that it did not need to reach the question of whether the merger would be anticompetitive in the market for sales to national accounts nationwide. Id. at 206. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C Circuit ("D.C. Circuit") upheld the injunction on appeal. United States v. Anthem, 855 F.3d 345 (D.C. Cir. 2017). |

| 66. |

Compl. at 9-14, United States v. Anthem, Inc. and Cigna Corp., No. 16 Civ. 01493 (D.D.C. Jul. 21, 2016). |

| 67. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 6.3. |

| 68. |

Id. |

| 69. |

Id. |

| 70. |

Id. |

| 71. |

Id. § 6.4. |

| 72. |

Id. |

| 73. |

Compl. at 1-2, 10-11 United States v. Dow Chemical Co., No. 17 Civ. 01176 (D.D.C. Jun. 15, 2017). |

| 74. |

Id. at 10. |

| 75. |

Proposed Final Judgement at 7, United States v. Dow Chemical Co., No. 17 Civ. 01176 (D.D.C. Jun. 15, 2017). |

| 76. |

Compl. at 13, United States v. AT&T Inc., No. 11 Civ. 01560 (D.D.C. Aug. 31, 2011). |

| 77. |

Id. Following the issuance of the complaint, the parties abandoned the transaction. Michael J. de la Merced, AT&T Ends $39 Billion Bid for T-Mobile, NY Times (Dec. 19, 2011), https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/12/19/att-withdraws-39-bid-for-t-mobile/?_r=0. |

| 78. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 7. |

| 79. |

Id. |

| 80. |

Id. §7.1 (observing that market concentration is an integral factor considered by the reviewing agencies when assessing the risk that coordinated effects may result from a proposed merger). |

| 81. |

Compl. at 16, United States v. AT&T Inc., No. 11 Civ. 01560 (D.D.C. Aug. 31, 2011). See also Compl. at 2-5, United States v. Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, 13 Civ. 00127 (D.D.C. Jan. 31, 2013) (arguing that the elimination of Modelo, a beer manufacturer and distributor, as a competitor for InBev, its proposed acquirer, and other beer producers, would substantially lessen competition because Modelo's aggressive competitive strategies constrained prices to a degree understated by Modelo's raw market share); Final Judgment at 10, United States v. Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, 13 Civ. 00127 (D.D.C. Oct. 24, 2013) (requiring the sale of Modelo's beer brewing capabilities within the United States to preserve Modelo as a competitor as a condition of merger approval). |

| 82. |

Compl. at 16, United States v. AT&T Inc., No. 11 Civ. 01560 (D.D.C. Aug. 31, 2011). |

| 83. |

Id. at 12-13, 16-17. |

| 84. |

Id. at 16-17. |

| 85. |

Compl., FTC v. H.J. Heinz, Co., No. 00 Civ. 1688 (D.D.C. Jul. 14, 2000). The D.C. Circuit agreed with the FTC. FTC v. H.J. Heinz, Co., 246 F.3d 708, 724-25 (D.C. Cir. 2001) (finding that the merger could create a "durable duopoly" which likely would incentivize coordinated interaction to the detriment of competition). |

| 86. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, at § 9. |

| 87. |

United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 51 (2001) (en banc) (per curiam) ("'Entry barriers' are factors (such as certain regulatory requirements) that prevent new rivals from timely responding to an increase in price above the competitive level") (internal citations omitted); Reazin v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kan., Inc. 899 F. 2d 951, 968 (10th Cir. 1990) ("Entry barriers are particular characteristics of a market which impede entry by new firms into that market ...."). Daniel E. Lazaroff, Entry Barriers and Contemporary Antitrust Litigation, 7 U.C. Davis Bus. L.J. 1, 4-5 (2005) (explaining that courts have considered barriers to entry to include, among other things, legal license requirements, higher capital costs on new entrants, entrenched customer brand loyalty, and patents). |

| 88. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, at § 10. |

| 89. |

Id. |

| 90. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, § 9-10. |

| 91. |

Id. |

| 92. |

Id. |

| 93. |

Id. § 11. |

| 94. |

See FTC v. Procter & Gamble Co., 386 U.S. 568, 577 (1967) ("All mergers are within the reach of [Section] 7, and all must be tested by the same standard, whether they are classified as horizontal, vertical, conglomerate, or other."); United States v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 353 U.S. 586, 592 (1956) ("We hold that any acquisition by one corporation of all or any part of the stock of another corporation, competitor or not, is within the reach of [Section 7] whenever the reasonable likelihood appears that the acquisition will result in a restraint of commerce, or in the creation of a monopoly in any line of commerce."). |

| 95. |

See Brown Shoe, Inc. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 323 (1962) ("Economic arrangements between companies standing in a supplier-customer relationship are characterized as 'vertical.'"). |

| 96. |

See Robert Bork, The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself 51 (1978) ("Foreclosure [that results from vertical integration] may occasionally be a threat to individual firms. It is never a threat to competition"); James A. Keyte & Kenneth B. Schwartz, Getting Vertical Mergers Through the Agencies: "Let's Make a Deal", 29 Antitrust 10, 12-15 (Summer 2015) (noting that by the 1980s, the reviewing agencies "appeared to be taking notice of the emerging economic thinking that vertical mergers rarely result in a substantial lessening of competition and typically generate significant procompetitive efficiencies."). |

| 97. |

See U.S. Dep't of Justice, Antitrust Division Policy Guide to Merger Remedies 5 (2011) ("Accordingly, in appropriate vertical merger matters the Division will consider tailored conduct remedies designed to prevent conduct that might harm consumers while still allowing the efficiencies that may come from the merger to be realized. ") [hereinafter "DOJ Consent Decree Guide"], https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2011/06/17/272350.pdf; Keyte & Schwartz, supra note 96 at 10 (explaining that the agencies rarely litigate against vertical mergers because there is little case law and they "appear to appreciate the complexity and difficulty of proving that a vertical merger will substantially harm competition or result in anticompetitive effects given the absence of a structural presumption and the likelihood [of] cognizable, merger-specific efficiencies."). |

| 98. |

Merger Guidelines, supra note 3, at n.1 ("These Guidelines do not cover vertical or other types of non-horizontal acquisitions."). |

| 99. |

See U.S. Dep't of Justice, Merger Guidelines 24 (1984), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2007/07/11/11249.pdf [hereinafter "1984 Guidelines"]. |

| 100. |

Id. Due to the age and the infrequency with which the 1984 Guidelines are cited, their value as substantive guidance for current agency review of vertical integration may be limited. Keyte & Schwartz, supra note 96 at 11 ("In addition to the scarcity of vertical merger case law, the Agencies' most recent guidelines regarding the analysis of vertical mergers – the Vertical Guidelines – are over three decades old, are infrequently cited, and provide only a modicum of insight into how the Agencies currently make enforcement decisions about vertical mergers."). |

| 101. |

Keyte & Schwartz, supra note 96 at 10-15 (observing that the DOJ and FTC rarely litigate vertical integration cases, but do take action to address competitive concerns raised by vertical transactions); M. Howard Morse, Vertical Mergers: Recent Learning, 53 Bus. Law. 1217 (1998) (collecting cases from the 1990s in which the FTC and DOJ took action to alleviate what they perceived as potentially anticompetitive effects of vertical integration). |

| 102. |

Phillip Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law ¶¶1004-1005, at 158-70 (3d ed. 2009) (describing foreclosure and coordination concerns that may be raised by vertical integration); Keyte & Schwartz, supra note 96 at 12-15. |

| 103. |

See Reuters Staff, Comcast Completes NBC Universal Merger, Reuters (Jan. 29, 2011), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-comcast-nbc-idUSTRE70S2WZ20110129. |

| 104. |

Compl. at 6-9, United States v. Comcast Corp., No. 11 Civ. 00106 (D.D.C. Jan. 18, 2011). Comcast eventually bought GE out of its share of the joint venture. Amy Chozick & Brian Stetler, Comcast Buys Rest of NBC in Early Sale, N.Y. Times: Media Decoder (Feb. 12, 2013, 4:54 PM), https://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/12/comcast-buying-g-e-s-stake-in-nbcuniversal-for-16-7-billion/. |

| 105. |

Final Judgment, United States v. Comcast Corp., No. 11 Civ. 00106 (D.D.C. Sept. 1, 2011). |

| 106. |

Compl. at 19-23, United States v. Comcast Corp., No. 11 Civ. 00106 (D.D.C. Jan. 18, 2011). |

| 107. |

Final Judgment at 9-14, United States v. Comcast Corp., No. 11 Civ. 00106 (D.D.C. Sept. 1, 2011). |

| 108. |

FTC, Premerger Notification and Merger Review Process, https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/mergers/premerger-notification-and-merger (last visited Aug. 21, 2017). See also DOJ Consent Decree Guide, supra note 97 at 1-2, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2011/06/17/272350.pdf; FTC, Frequently Asked Questions About Merger Consent Order Provisions, https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/mergers/merger-faq (last visited Aug. 21, 2017). |

| 109. |

See H.R. Rep. No. 114-449, at 2-3 (2016) ("For the vast majority of transactions, the antitrust enforcement agencies will grant an early termination of the statutory waiting period or simply allow the waiting period to expire without taking any formal action[.]").This House Report was produced to accompany the Standard Mergers and Acquisition Through Equal Reviews Act of 2015 (SMARTER Act). H.R. 2745, 114th Cong. (2015). The bill would have aligned the FTC's pre-merger enforcement authority with the DOJ's. The bill was passed by the House on March 23, 2016, and referred to the Senate, but never became law. A new version of the bill has been introduced in the 115th Congress. H.R. 659, 115th Cong. (2017). |

| 110. |

H.R. Rep. No. 114-449, at 40 (2016) (dissenting views) (noting that lawsuits to stop mergers from proceeding are "exceedingly rare"). |

| 111. |

15 U.S.C. § 21 (granting the FTC authority to prevent mergers that would substantially lessen competition via adjudication); id. § 25 (granting the DOJ the authority to seek preliminary and permanent injunctions of mergers before their completion from a federal court); id. § 45 (granting the FTC authority to proceed administratively against unfair methods of competition); id. § 53(b) (granting the FTC authority to seek a preliminary or permanent injunction against any practice that may violate any statute overseen by the FTC). |

| 112. |

See Michael B. Bernstein, Kelly Schoolmeester, & Francesca M. Pisano, U.S. Competition Law – Merger Enforcement: 2015 Year in Review 9 (Feb. 29, 2016). This appears to have been what happened when the DOJ filed suit to block AT&T's proposed acquisition of T-Mobile. A few months after the DOJ filed its case in federal court, the parties abandoned the deal. Michael J. de la Merced, AT&T Ends $39 Billion Bid for T-Mobile, NY Times (Dec. 19, 2011), https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/12/19/att-withdraws-39-bid-for-t-mobile/?_r=0. A similar fate befell John Deere's planned acquisition of Precision Planting from Monsanto. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Deere Abandons Proposed Acquisition of Precision Planting from Monsanto (May 1, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/deere-abandons-proposed-acquisition-precision-planting-monsanto. |

| 113. |

For example, in 2016 the DOJ filed a complaint to block Anthem's planned acquisition of Cigna. Compl., United States v. Anthem, Inc. and Cigna Corp., No. 16 Civ. 01493 (D.D.C. Jul. 21, 2016). After consideration, the district court agreed with the DOJ that the merger likely would substantially lessen competition in the market for sales to national account within fourteen states, and that the merger would substantially less competition in the market for sales to large group employers in Richmond, VA, entering a permanent injunction against the transaction in February 2017. United States v. Anthem, Inc., 236 F. Supp. 3d 171, 201 (D.D.C. 2017). The D.C. Circuit upheld the district court's injunction in the case. United States v. Anthem, 855 F.3d 345 (D.C. Cir. 2017). Initially, Anthem filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court. Eric Kroh, Anthem Appeals $54B Cigna Merger Case to Supreme Court, Law360 (May 5, 2017), https://www.law360.com/articles/920964/anthem-appeals-54b-cigna-merger-case-to-supreme-court. However, after a state court judge ruled in Cigna's favor in a state corporate law case related to the deal in May 2017, the parties abandoned the deal and Anthem withdrew its Supreme Court petition. See Anthem v. United States, 137 S.Ct. 2250 (Jun. 12, 2017) (dismissing petition for writ of certiorari); Brent Kendall, Anna Wilde Mathews, & Peg Brickley, Delaware Judge Frees Cigna to Exit Anthem Merger, Wall St. J. (May 11, 2017), https://www.wsj.com/articles/delaware-judge-frees-cigna-to-exit-anthem-merger-1494537564. |

| 114. |

15 U.S.C. § 25. Only the FTC has authority to enforce the FTC Act. See id. § 45(a)-(b) (granting enforcement powers to the FTC). |

| 115. |

Id. § 25. |

| 116. |

Id. For a preliminary injunction to be issued, the DOJ generally must show "a reasonable likelihood of success on the merits and whether the balance of equities tips in its favor." United States v. Siemens Corp. 621 F.2d 499, 505 (2d Cir. 1980) (applying the quoted standard in antitrust case where the government sought to enjoin an acquisition). |

| 117. |

H.R. Rep. No. 114-449, at 3 (2016); AMC Report, supra note 17, at 130. |

| 118. |

See United States v. Anthem, 236 F. Supp. 3d 171, 259 (D.D.C. 2017); United States v. Aetna, 240 F.Supp.3d 1, 19 (D.D.C. 2017); United States v. Oracle Corp., 331 F. Supp. 2d 1098, 1109 (N.D. Cal. 2004); AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 119. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 120. |

ProMedica Health Sys., Inc. v. FTC, 749 F.3d 559, 570 (6th Cir. 2014), AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 121. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. Notably, if the DOJ or FTC does appeal a denial of a preliminary or permanent injunction, the merger may consummate nonetheless. See FTC v. Whole Foods Market, Inc., 548 F.3d 1028, 1033 (D.C. Cir. 2008). The FTC challenged Whole Foods Market, Inc.'s planned acquisition of Wild Oats Market, Inc. Id. at 1032. The district court denied the agency's request for a preliminary injunction. Id. at 1033. The FTC filed a motion for an injunction pending appeal, which the D.C. Circuit denied. Id. The parties consummated the transaction and the appellate case continued. Id. Eventually, the D.C. Circuit reversed the district court's decision denying the preliminary injunction. Id. at 1041. |

| 122. |

15 U.S.C. §§ 25, 27. |

| 123. |

See DOJ Consent Decree Guide, supra note 97, at 6-7. |

| 124. |

H.R. Rep. No. 114-449, at 3 (2016). For example, after reviewing Monsanto's proposed acquisition of Delta and Pine Land Company in 2007, the parties and the DOJ reached a consent agreement that permitted the transaction with certain conditions. On the same day that the DOJ filed a complaint asking the court to enjoin the transaction, it also filed a proposed final judgment and a Hold Separate Order. See Compl. at 1-2, United States v. Monsanto Co., No. 7 Civ. 00992 (D.D.C. May 31, 2007); Proposed Final Judgment, United States v. Monsanto Co., No. 7 Civ. 00992 (D.D.C. May 31, 2007); Proposed Hold Separate and Preservation of Assets Stipulation and Order, United States v. Monsanto Co., No. 7 Civ. 00992 (D.D.C. May 31, 2007). |

| 125. |

See, e.g., Proposed Hold Separate and Preservation of Assets Stipulation and Order, United States v. Anheuser Busch InBev, No. 11 Civ. 01483 (D.D.C. Jul. 20, 2016); Proposed Hold Separate and Preservation of Assets Stipulation and Order, United States v. Monsanto Co., No. 7 Civ. 00992 (D.D.C. May 31, 2007). See also FTC, Frequently Asked Questions About Merger Consent Order Provisions, https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/mergers/merger-faq (last visited Aug. 21, 2017): A hold separate order keeps the "eggs unscrambled" pending divestiture by requiring the divestiture assets to be operated separately from and independently of respondent's business. It preserves the assets to be divested and maintains interim competition (as well as the Commission's remedial options if it changes its views on the scope of assets to be divested after the public comment period) by preventing commingling with the respondent's business. It prevents the transfer of competitively sensitive information. The purpose is to prevent interim competitive harm and to preserve the viability and competitiveness of the assets pending divestiture. By taking the assets out of the hands of the respondent, they should be better protected from intentional or unintentional physical or intangible deterioration that would impact their ability to be operated in a manner that maintains or restores competition. Further, the respondent should be unable to exercise any market power it might have gained from the merger. As an alternative to (and sometimes in conjunction with) taking control of the assets from the respondent, a monitor trustee may be used to oversee the operations and maintenance of the assets. |

| 126. |

Robert Lipstein, Michael Van Arsdall, & Britton Davis, With Remedies Agreed We Can Close Our Deal, Right?, Law360 (Oct. 11, 2012), https://www.crowell.com/files/With-Remedies-Agreed-We-Can-Close-Our-Deal-Right.pdf; David Ingram, In U.S. Mergers, No One Waits for this Waiting Period, Reuters (Mar. 5, 2014), http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-antitrust-tunney-analysis-idUSBREA240D620140305. |

| 127. |

15 U.S.C. § 16(b)-(h). |

| 128. |

Id. § 16(b). |

| 129. |

Id. § 16(d). |

| 130. |

DOJ Consent Decree Guide, supra note 97, at 6 (2011), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2011/06/17/272350.pdf (noting that depending upon the transaction, either structural remedies, conduct remedies, or both may be appropriate). See, e.g., Final Judgment, United States v. Monsanto Co., No. 7 Civ. 00992 (D.D.C. Nov. 6, 2008). |

| 131. |

15 U.S.C. § 16(e). |

| 132. |

See 15 U.S.C. § 21 (allowing the FTC to enforce Section 7 via an administrative process); id. § 45(b) (allowing the FTC to pursue violations of Section 5 of the FTC Act administratively); id. § 53(b) (permitting the FTC to seek preliminary and permanent injunctions in federal court to restrain violations of any statute overseen by the FTC). |

| 133. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 134. |

15 U.S.C. § 21. |

| 135. |

Id. § 45(b). Under this provision, the Commission may issue a complaint setting forth the conduct it has reason to believe is in violation of the Act, after which the person accused of violating the Act would have the opportunity to be heard at an administrative trial before an administrative law judge. Fed. Trade Comm'n, A Brief Overview of the Federal Trade Commission's Investigative and Law Enforcement Authority (Jul. 2008), https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-do/enforcement-authority (noting that administrative proceedings under the Clayton Act are similar to those under the FTC Act). |

| 136. |

15 U.S.C. § 53(b). |

| 137. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 130. |

| 138. |

15 U.S.C. § 53(b). The FTC has the authority under Section 13(b) of the FTC Act to request a permanent injunction preventing the transaction's completion at the same time that the agency requests a preliminary injunction. Id. § 53(b). However, in contrast to the practice of the DOJ, the FTC generally does not file motions for preliminary and permanent injunctions at the same time. AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 139. |

AMC Report, supra note 17, at 138. |

| 140. |

15 U.S.C. § 45(b); id. § 21. |

| 141. |