The State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report: Scope, Aid Restrictions, and Methodology

The State Department’s annual release of the Trafficking in Persons report (commonly referred to as the TIP Report) has been closely monitored by Congress, foreign governments, the media, advocacy groups, and other foreign policy observers. The 109th Congress first mandated the report’s publication in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA; Div. A of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, P.L. 106-386).

The number of countries covered by the TIP Report has grown over time. In the 2019 TIP Report, released on June 20, 2019, the State Department categorized 187 countries, including the United States. Countries were placed into one of several lists (or tiers) based on their respective governments’ level of effort to address human trafficking between April 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019. An additional category of special cases included three countries that were not assigned a tier ranking because of ongoing political instability (Libya, Somalia, and Yemen).

Its champions describe the TIP Report as a foundational measure of government efforts to address and ultimately eliminate human trafficking. Some U.S. officials refer to the report as a crucial tool of diplomatic engagement that has encouraged foreign governments to elevate their antitrafficking efforts. Its detractors question the TIP Report’s credibility as a true measure of antitrafficking efforts, suggesting at times that political factors, such as the desire to maintain positive bilateral relations with a given country, distort its country assessments. Some foreign governments perceive the report as a form of U.S. interference in their affairs.

Continued congressional interest in the TIP Report and its country rankings has resulted in numerous key modifications to the country-ranking process and methodology. Modifications have included the creation of the special watch list, limiting the length of time a country may remain on a subset of the special watch list, modifying some of the criteria for evaluating antitrafficking efforts, establishing a list of governments that recruit and use child soldiers and subjecting these countries to potential security assistance restrictions, and prohibiting the least cooperative countries on antitrafficking matters from participating in authorized trade negotiations. These modifications were often included as part of broader legislative efforts to reauthorize the TVPA, whose current authorization for appropriations expires at the end of FY2021.

Recent Developments

Largely due to congressional concerns that the report’s methodology lacks transparency and is susceptible to political pressure, in January 2019 Congress passed two bills that further modified key aspects of the annual country-ranking and reporting process. Taken together, the Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act of 2018 (2018 TVPPRA; P.L. 115-425) and the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2017 (2017 TVPRA; P.L. 115-427) reduce to a degree the State Department’s flexibility and discretion in assigning tier rankings to countries, and may result in increases in the number of countries that fall into the lowest-effort category (Tier 3). The 2018 TVPRRA also broadened the criteria for listing child soldier countries, potentially leading to greater numbers of countries that are listed.

Ensuring that countries perceive the TIP Report as credible is crucial to its effectiveness in motivating governments to improve their antitrafficking efforts. Changes introduced to strengthen the credibility of the TIP Report’s methodology, however, have also resulted in a ranking process and antitrafficking criteria that have shifted and grown more complex over time, raising potential policy questions. Congress may consider whether the report’s antitrafficking expectations and rankings are perceived by countries as inconsistent or overly elaborate. Congress also may consider if the prospect of achieving an improved ranking in the TIP Report can sometimes appear beyond reach, potentially eroding the TIP Report’s ability to motivate countries to improve their antitrafficking efforts.

The State Department's Trafficking in Persons Report: Scope, Aid Restrictions, and Methodology

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- TIP Report Scope

- Country Narratives and Country Lists ("Tiers")

- 2019 TIP Report Country Lists

- Reporting Requirements Related to the Special Watch List

- Mid-Year Interim Assessment

- Watch List Automatic Downgrades and Downgrade Waivers

- Justifications for Country-Ranking Changes

- Information on Tier 3 Upgrades Pursuant to the TPA

- Child Soldier Reporting Requirements

- Other Required Information in the TIP Report

- Standards and Definitions for Determining Country Rankings

- Four Minimum Standards

- Twelve Criteria for Serious and Sustained Efforts

- Factors for Evaluating Significant Efforts

- Country-Ranking Decision Flow

- Actions Against Governments Failing to Meet Minimum Standards

- Aid Restrictions for Tier 3 Countries

- Aid Authorized by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961

- Sales and Financing Authorized by the Arms Export Control Act

- Funding for Educational and Cultural Exchanges

- Loans and Other Funds Provided by Multilateral Development Banks and the International Monetary Fund

- Presidential Determinations, Waivers, and Certifications

- Trade Restrictions for Tier 3 Countries

- Security Assistance Restrictions for Child Soldier Countries

- Exceptions and Presidential Determinations, Certifications, and Waivers

- Impacts of Restrictions and Waivers

- TIP Report Methodology

- Report Release

- Illustrative Draft Cycle

- Information Sources

- Global Law Enforcement Data

- Human Trafficking Trends

- Criticisms and Alternatives to the TIP Report

- Lack of Consistent and Transparent Evaluations

- Political Motivation Behind Rankings

- Treatment of the United States

- Emphasis on Prosecution

- Insufficient Coverage of Key Themes

- Other Global Reports and Databases

- Legislative Outlook

Figures

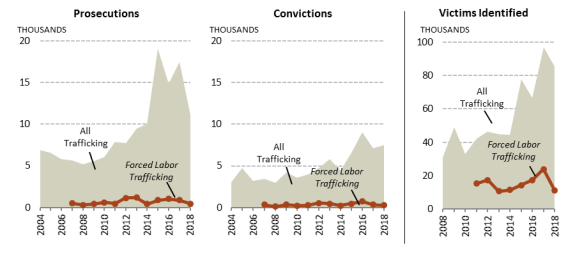

- Figure 1. Key Legislative Changes to the TIP Report, 2000-2019

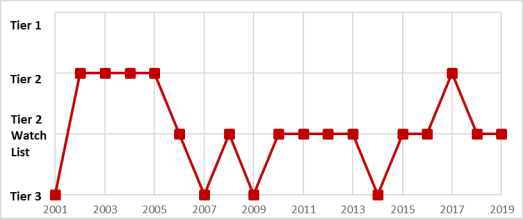

- Figure 2. 2019 TIP Report: Country Rankings

- Figure 3. Country-Ranking Decisions: Which Tier in the TIP Report?

- Figure 4. TIP Report: Typical Draft and Review Process

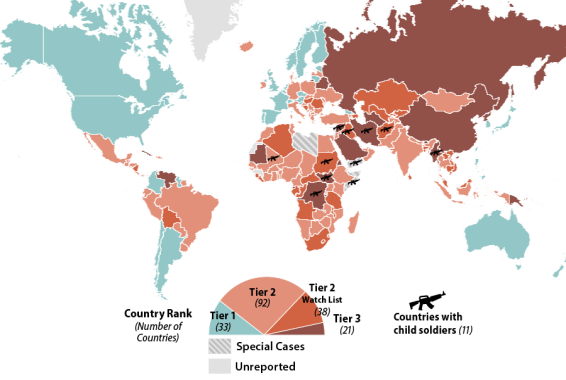

- Figure 5. Global Law Enforcement Data from TIP Reports, 2004-2018

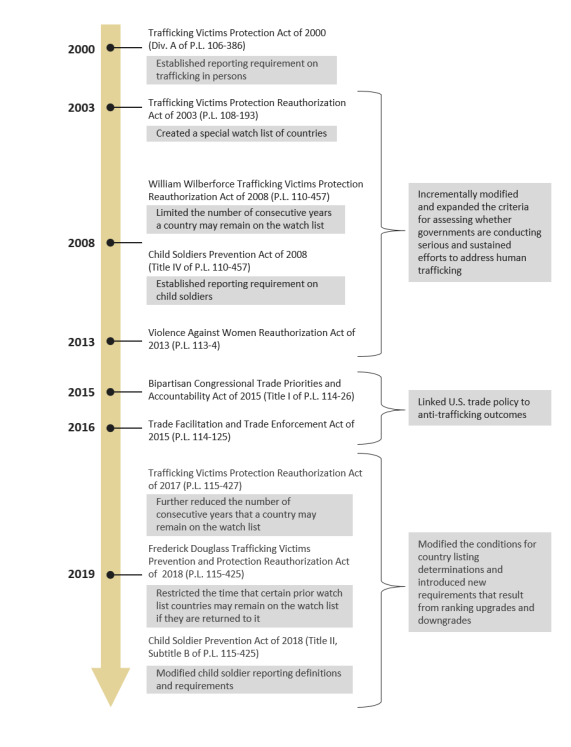

- Figure 6.Malaysia: Historical TIP Rankings, 2001-2019

Tables

- Table 1. Tier 2 Watch List Countries for More than Two Consecutive Years

- Table 2. Aid Restrictions and Waivers for Tier 3 Countries, Pursuant to the TVPA, FY2004-FY2020

- Table 3. Aid Restrictions and Waivers to Child Soldier Countries, Pursuant to the CSPA, FY2011-FY2020

- Table A-1.Tier 1 Countries in the 2019 TIP Report

- Table A-2.Tier 2 Countries in the 2019 TIP Report

- Table A-3.Tier 2 Watch List Countries in the 2019 TIP Report

- Table A-4.Tier 3 Countries in the 2019 TIP Report

Summary

The State Department's annual release of the Trafficking in Persons report (commonly referred to as the TIP Report) has been closely monitored by Congress, foreign governments, the media, advocacy groups, and other foreign policy observers. The 109th Congress first mandated the report's publication in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA; Div. A of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, P.L. 106-386).

The number of countries covered by the TIP Report has grown over time. In the 2019 TIP Report, released on June 20, 2019, the State Department categorized 187 countries, including the United States. Countries were placed into one of several lists (or tiers) based on their respective governments' level of effort to address human trafficking between April 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019. An additional category of special cases included three countries that were not assigned a tier ranking because of ongoing political instability (Libya, Somalia, and Yemen).

Its champions describe the TIP Report as a foundational measure of government efforts to address and ultimately eliminate human trafficking. Some U.S. officials refer to the report as a crucial tool of diplomatic engagement that has encouraged foreign governments to elevate their antitrafficking efforts. Its detractors question the TIP Report's credibility as a true measure of antitrafficking efforts, suggesting at times that political factors, such as the desire to maintain positive bilateral relations with a given country, distort its country assessments. Some foreign governments perceive the report as a form of U.S. interference in their affairs.

Continued congressional interest in the TIP Report and its country rankings has resulted in numerous key modifications to the country-ranking process and methodology. Modifications have included the creation of the special watch list, limiting the length of time a country may remain on a subset of the special watch list, modifying some of the criteria for evaluating antitrafficking efforts, establishing a list of governments that recruit and use child soldiers and subjecting these countries to potential security assistance restrictions, and prohibiting the least cooperative countries on antitrafficking matters from participating in authorized trade negotiations. These modifications were often included as part of broader legislative efforts to reauthorize the TVPA, whose current authorization for appropriations expires at the end of FY2021.

Recent Developments

Largely due to congressional concerns that the report's methodology lacks transparency and is susceptible to political pressure, in January 2019 Congress passed two bills that further modified key aspects of the annual country-ranking and reporting process. Taken together, the Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act of 2018 (2018 TVPPRA; P.L. 115-425) and the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2017 (2017 TVPRA; P.L. 115-427) reduce to a degree the State Department's flexibility and discretion in assigning tier rankings to countries, and may result in increases in the number of countries that fall into the lowest-effort category (Tier 3). The 2018 TVPRRA also broadened the criteria for listing child soldier countries, potentially leading to greater numbers of countries that are listed.

Ensuring that countries perceive the TIP Report as credible is crucial to its effectiveness in motivating governments to improve their antitrafficking efforts. Changes introduced to strengthen the credibility of the TIP Report's methodology, however, have also resulted in a ranking process and antitrafficking criteria that have shifted and grown more complex over time, raising potential policy questions. Congress may consider whether the report's antitrafficking expectations and rankings are perceived by countries as inconsistent or overly elaborate. Congress also may consider if the prospect of achieving an improved ranking in the TIP Report can sometimes appear beyond reach, potentially eroding the TIP Report's ability to motivate countries to improve their antitrafficking efforts.

Introduction

The State Department estimates that globally there are 24.9 million victims of human trafficking, also commonly referred to as modern slavery.1 Several international mechanisms exist to define and address human trafficking, such as the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (the Palermo Protocol) and the United Nations (U.N.) Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. In the United States, Congress has led efforts to eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons domestically and internationally, particularly with its enactment of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-386). Division A of that act, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA), established U.S. antitrafficking policy to (1) prevent trafficking, (2) protect trafficking victims, and (3) prosecute and punish traffickers (known as the three Ps).2

A key element of the TVPA's foreign policy objectives involved a new requirement for the Secretary of State to produce an annual report on human trafficking and to rank foreign governments based on their antitrafficking efforts. In the ensuing reports, which the State Department titled as Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports, the department developed a ranking system in which the best-ranked countries were identified as Tier 1 and the worst-ranked as Tier 3. Moreover, the TVPA stipulated that the worst performers (Tier 3 countries) in the TIP Report could be subject to potential restrictions on certain types of U.S. foreign aid and other U.S. and multilateral funds—a policy that is intended to motivate countries to avoid Tier 3 by prioritizing antitrafficking efforts.

The TIP Report's annual release remains a topic of widespread interest among international and domestic stakeholders, including Congress. Since the TVPA's enactment 19 years ago, Congress has continued to adjust the requirements associated with how countries are ranked in the TIP Report, as well as the policy consequences of such rankings (see Figure 1). These changes were often the result of congressional dissatisfaction with some aspect of the TIP Report:

- Due to difficulty discerning differences among Tier 2 countries, Congress modified the TVPA in 2003 to create a special watch list, composed of countries that deserve enhanced scrutiny.

- Out of concern that countries were listed for too many consecutive years on the special watch list, Congress modified the TVPA in 2008 to limit the number of years a country may remain on it.

- In response to the plight of children exploited in armed conflict, Congress modified the TVPA in 2008 to require the State Department to identify countries whose governments recruit and use child soldiers, with identified countries subject to potential security assistance restrictions.

- With the objective of linking U.S. trade policy to antitrafficking outcomes, Congress in 2015 prohibited Tier 3 countries from participating in authorized trade negotiations.3

- Reflecting continued concern over country-ranking decisions, Congress modified the TVPA in 2019 to impose further limitations on how long countries may remain on the special watch list, and to require that the State Department provide justifications for changing a country's tier ranking.

- Desiring stronger action against child soldiering, Congress in 2019 expanded the child soldier country listing requirements by including the recruitment or use of child soldiers by police or other security forces, and requiring additional and public reporting on the use of waivers and exceptions for security assistance restrictions to listed countries.

- As a result of greater awareness of antitrafficking best practices, Congress has also continued to expand incrementally and modify definitions pertaining to the expected antitrafficking efforts that guide country-ranking determinations.

A key question is whether changes to the TIP Report's methodology and ranking process, meant to bolster the report's legitimacy and incentivize countries to boost their antitrafficking efforts, also run the risk of increasing the complexity of these factors in a manner that undermines the report's impact.4

This CRS report describes the legislative provisions that govern the U.S. Department of State's production of the annual TIP Report, reviews country-ranking trends in the TIP Report, and identifies recent congressional oversight of and legislative activity to modify the TIP Report.

|

Figure 1. Key Legislative Changes to the TIP Report, 2000-2019 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Congress.gov. |

TIP Report Scope

The contents of each annual TIP Report are governed by two provisions, one in the TVPA, as amended, and a second in the Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008 (CSPA; Title IV of P.L. 110-457), as amended.5 In addition, current law requires the President and the Secretary of State to prepare related follow-on documentation for certain categories of countries. These include reporting requirements that were added to the TVPA as part of TVPA reauthorization acts, as well as requirements contained in the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA; Title I of P.L. 114-26, the Defending Public Safety Employees' Retirement Act), as amended.

Country Narratives and Country Lists ("Tiers")

The TVPA, as amended, establishes the core contents of the TIP Report. Specifically, it requires the Secretary of State to submit to appropriate congressional committees an annual report, due not later than June 1 each year, which describes, on a country-by-country basis,6

- government efforts to eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons;

- the nature and scope of trafficking in persons in each country; and

- trends in each government's efforts to combat trafficking.

|

What Are Severe Forms of Trafficking in Persons? The TVPA defines severe forms of trafficking in persons to mean (A) sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age; or (B) the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.7 This definition is largely consistent with the definition of trafficking in persons contained in the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children8 (adopted by the U.N. in 2000, often referred to as the "Palermo Protocol"). TIP Reports use the terms trafficking in persons, severe forms of trafficking in persons, and human trafficking interchangeably, and in recent years have also described human trafficking as modern slavery. The 2019 TIP Report states, "The United States considers 'trafficking in persons,' 'human trafficking,' and 'modern slavery' to be interchangeable umbrella terms that refer to both sex and labor trafficking."9 The report emphasizes that human trafficking as defined under the Palermo Protocol does not require movement across national borders, nor the transport or movement of the victim from one place to another. It illustratively describes manifestations of human trafficking to include sex trafficking, child sex trafficking, forced labor, bonded labor (also known as debt bondage), domestic servitude, forced child labor, and unlawful recruitment and use of child soldiers.10 Some government and nongovernmental entities may apply different definitions to refer to human trafficking, sometimes conflating human trafficking with human smuggling, illegal adoptions, international trade in human organs, child pornography, and prostitution. |

Central to the content of the TIP Report, as required by the TVPA, is a set of country lists, based on whether governments are achieving four minimum standards that the law prescribes for the elimination of severe forms of trafficking in persons (for information on the minimum standards see the "Standards and Definitions for Determining Country Rankings" section below). Specifically, the TVPA requires the report to include11

- A list of countries whose governments fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of severe forms of trafficking in persons; TIP Reports describe this list as Tier 1.12

- A list of countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards but are making significant efforts to become compliant; TIP Reports describe this list as Tier 2.

- A list of countries whose governments do not fully comply and are not making significant efforts to become compliant; TIP Reports describe this list as Tier 3.

In addition, in accordance with the 2003 amendments to the TVPA, which required the creation of a new "special watch list," TIP Reports since 2004 have listed countries on what the State Department describes as the Tier 2 Watch List.13 For further discussion, see section on "Reporting Requirements Related to the Special Watch List."

Finally, the CSPA requires that the TIP Report include a separate list of countries whose governments recruit or use child soldiers. (See "Child Soldier Reporting Requirements" below.)

Tier 3 countries and child soldier countries are subject to potential aid and other restrictions (for details, see section on "Actions Against Governments Failing to Meet Minimum Standards").

2019 TIP Report Country Lists

The country lists from the 2019 TIP Report, which covered developments from April 2018 through March 2019, are illustrated by Figure 2 below. Complete country lists are in

Appendix A.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on U.S. Department of State, 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report, June 20, 2019. |

Reporting Requirements Related to the Special Watch List

The TVPA, as amended, requires the Secretary of State to submit to appropriate congressional committees a special watch list composed of countries determined by the Secretary of State to require special scrutiny during the following year. This requirement to develop a special watch list was first enacted in the TVPA reauthorization of 2003.14

The TVPA mandates that this list be composed of three types of countries: (1) countries upgraded in the most recent TIP Report and now assessed to be fully compliant with the minimum standards (from Tier 2 to Tier 1); (2) countries upgraded in the most recent TIP Report and now assessed to be making significant efforts toward compliance with the minimum standards (from Tier 3 to Tier 2); and (3) a subset of Tier 2 countries in which

- the estimated number of victims is very significant or significantly increasing and the country is not taking proportional concrete actions;15 or

- there is a failure to provide evidence of increasing efforts to combat severe forms of trafficking in persons, compared to the previous year.16

Although the TVPA, as amended, authorizes the special watch list to be submitted separately from the TIP Report, the State Department introduced it as a feature in the 2004 TIP Report.17 Beginning with that report, the department included an additional list of countries in the annual TIP Report, called the Tier 2 Watch List. This Tier 2 Watch List is composed of the special watch list countries that fall into the third category of countries described above—those that would otherwise be listed as Tier 2 except that the number of victims is large and growing and the country is not taking proportional concrete actions, or there is a failure to provide evidence of increasing antitrafficking efforts.18

Mid-Year Interim Assessment

The TVPA, as amended, requires the Secretary of State to submit to appropriate congressional committees by February 1 each year an interim assessment of the progress made by each special watch list country since the last TIP Report.19 These mid-year assessments are typically brief, stating both positive and negative developments in each special watch list country. Readers are unable to predict, based solely on these reports, whether a country's ranking will improve, remain the same, or decline in the next TIP Report.

Watch List Automatic Downgrades and Downgrade Waivers

The TVPA, as amended, requires that a country on the special watch list (in practice, the Tier 2 Watch List) for two consecutive years be subsequently listed among those whose governments do not fully comply and are not making significant efforts to become compliant (Tier 3).20 The President may waive this automatic downgrade for one additional year (as of a January 2019 amendment, see below) if the President determines and reports credible evidence justifying a waiver because

- the country has a written plan to begin making significant efforts to become compliant with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking in persons;

- the written plan, if implemented, would constitute significant efforts to become compliant with the minimum standards; and

- the country is devoting sufficient resources to implement the plan.21

The requirement to limit the length of time a country may remain on the watch list was enacted in the TVPA reauthorization of 2008.22 The first year in which it came into effect was 2009 and the first year in which a Tier 2 Watch List country was downgraded because of its time in this tier category was 2013.

The 2017 TVPRA, enacted in January 2019, reduced the presidential waiver authority to the current one-year duration from a prior maximum of two consecutive years, effectively reducing the maximum consecutive number of years a country may be listed on the Tier 2 Watch List from four years to three years.23

"Special Rule" Restriction

The 2018 TVPPRA, also enacted in January 2019, created a new "special rule" for countries that are listed on the Tier 2 Watch List for three or more consecutive years (two years and any additional years as a result of a presidential waiver) and are subsequently downgraded to Tier 3. These countries, if they are then later returned to the Tier 2 Watch List, may be listed on the Tier 2 Watch List for no more than one consecutive year. These conditions apply to prior country lists since December 23, 2008, the date of enactment of the 2008 TVPRA.24

Among Tier 2 Watch List countries in the 2019 TIP Report, the above new restrictions appear to limit the State Department's flexibility to list Bolivia, Gabon, Laos, Malaysia, and Uzbekistan on the Tier 2 Watch List again next year.

2019 TIP Report Watch List Downgrades and Downgrade Waivers

In the 2019 TIP Report, three countries were downgraded to Tier 3 after two or more consecutive years on the Tier 2 Watch List:

- Cuba (downgraded after four consecutive years on the Tier 2 Watch List);

- The Gambia (downgraded after two consecutive years); and

- Saudi Arabia (downgraded after four consecutive years).

A total of seven countries received waivers to stay on the Tier 2 Watch List for more than two consecutive years (see Table 1). All seven countries have now exhausted the new three consecutive year duration limitation.

Table 1. Tier 2 Watch List Countries for More than Two Consecutive Years

Country Rank Outcomes in the 2016-2019 TIP Reports

|

Country |

2016 TIP Report |

2017 TIP Report |

2018 TIP Report |

2019 TIP Report |

|

Algeria |

Tier 3 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Bangladesh |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Hungary |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Iraq |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Liberia |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Montenegro |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

|

Nicaragua |

Tier 2 |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Tier 2 Watch List |

Source: U.S. Department of State, TIP Reports, 2016-2019.

|

How Is Congress Notified of Watch List Downgrade Waivers? Credible evidence in support of downgrade waivers is to be submitted to the Senate Foreign Relations and the House Foreign Affairs Committees. Within 30 days after such congressional notification, the TVPA, as amended, also requires the Secretary of State to provide a detailed description of the credible information supporting the determination on a publicly available website maintained by the State Department, and to offer to brief the Senate Foreign Relations and House Foreign Affairs Committees on the written plans for significant efforts to become compliant with the minimum standards.25 |

Justifications for Country-Ranking Changes

The 2017 TVPRA added a new requirement that the TIP Report include a justification for each country that is ranked differently than it was in the prior year's TIP Report. In particular, the law requires a "detailed explanation" on how "concrete actions" taken or not taken by the country contributed to the listing change, "including a clear linkage between such actions and the minimum standards."26 (See "Four Minimum Standards" below.)

Information on Tier 3 Upgrades Pursuant to the TPA

Pursuant to the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA), as amended, the President is also separately required to submit to appropriate congressional committees information on countries upgraded from Tier 3 in the prior year's TIP Report. Pursuant to the TPA, the President must submit detailed descriptions of credible evidence supporting these upgrades.27 The detailed descriptions may be accompanied by copies of documents providing such evidence.

Child Soldier Reporting Requirements

|

Who Is a Child Soldier? Pursuant to the CSPA, as amended, the term "child soldier" refers to persons under age 18 who (i) take direct part in hostilities as a member of government armed forces, police, or other security forces; or (ii) are compulsorily recruited into governmental armed forces, police, or other security forces (or are under 15 years old and are voluntarily recruited), including in noncombat support roles; or (iii) are recruited or used in hostilities by non-state armed forces, including in noncombat support roles. |

Congress enacted the Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008 (CSPA) as part of its 2008 reauthorization of the TVPA.28 A key element of the CSPA is the requirement to include in the annual TIP Report an additional list of foreign governments that recruit or use child soldiers in their armed forces, police, or other security forces, or in government-supported armed groups.29 Government-supported armed groups include paramilitaries, militias, and civil defense forces.

The 2019 TIP Report placed 11 countries on the CSPA list: Afghanistan, Burma, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Iran, Iraq, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.30

Other Required Information in the TIP Report

In addition to the required country lists, the TVPA requires the State Department to include other information in the annual TIP Report. This includes31

- information on what the United Nations (U.N.), Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and other multilateral organizations, as appropriate, are doing to prevent their employees, contractors, and peacekeeping forces from engaging in human trafficking or exploiting victims of trafficking;

- information on changes in the global patterns of human trafficking, including prevalence data, disaggregated by source, transit, and destination countries, as well as nationality, gender, and age;

- information on emerging human trafficking issues; and

- information on "promising practices in the eradication of trafficking in persons."32

Standards and Definitions for Determining Country Rankings

As discussed above, the TIP Report is the evaluates of each government's commitment to eliminating severe forms of trafficking in persons. Countries are assessed based on whether they are complying with, or making significant efforts to comply with, four minimum standards prescribed by the TVPA, as amended.33 The TVPA defines the four minimum standards and 12 related criteria, and also provides guidance on the factors that the State Department is to consider when determining whether a country that is not compliant with the minimum standards is nonetheless making significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance.

While the four minimum standards have not been amended since the TVPA was first enacted, the criteria for evaluating what constitutes serious and sustained efforts to eliminate trafficking, which relate to the fourth standard, have been modified and expanded through multiple reauthorizations of the TVPA since 2000.34 The factors relating to significant efforts (which are separate from and not to be confused with the current 12 criteria) have also been modified through recent reauthorizations.35

Although these provisions prescribe the means through which the State Department is to evaluate the efforts of foreign governments, State Department officials may exercise considerable discretion in categorizing countries (for further discussion, see "Criticisms and Alternatives to the TIP Report.")

Four Minimum Standards

The TVPA identifies four minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking, which governments are expected to achieve:36

- 1. Governments should prohibit severe forms of trafficking in persons and punish such acts.

- 2. Governments should prescribe punishment commensurate with that of grave crimes for the knowing commission of any act involving sex trafficking induced by force, fraud, or coercion; sex trafficking involving a child; or any act that includes rape, kidnapping, or which causes death.

- 3. Governments should prescribe punishment for the knowing commission of any severe form of trafficking in persons that is sufficiently stringent to deter future acts and adequately reflect the heinous nature of the offense.

- 4. Governments should make serious and sustained efforts to eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons.

Twelve Criteria for Serious and Sustained Efforts

In assessing whether governments are achieving the fourth minimum standard, that of making serious and sustained efforts to eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons, the TVPA initially included seven criteria, or indicative factors.37 Subsequent TVPA reauthorizations amended the TVPA to modify some of the original criteria and expand the list. There are currently 12 criteria:

- 1. Enforcement and prosecution—whether governments vigorously investigate and prosecute acts of severe forms of trafficking in persons, including convicting and sentencing those responsible for such acts.38

- 2. Victim protection—whether governments protect victims of severe forms of trafficking in persons, encourage their assistance in the investigation and prosecution of such trafficking, and ensure that victims are not inappropriately incarcerated, filed, or otherwise penalized for unlawful acts resulting directly from having been trafficked.39

- 3. Trafficking prevention—whether governments have adopted measures to prevent severe forms of trafficking in persons.40

- 4. International cooperation—whether governments cooperate with other governments in the investigation and prosecution of severe forms of trafficking in persons and whether governments have entered into bilateral, multilateral, or regional law enforcement cooperation and coordination arrangements with others.41

- 5. Extradition—whether governments extradite those charged with acts of severe forms of trafficking in persons on terms and to an extent similar to those charged with other serious crimes.

- 6. Trafficking patterns and human rights protections—whether governments monitor migration patterns for evidence of severe forms of trafficking in persons and whether law enforcement responses to such evidence are both consistent with the vigorous investigation and prosecution of acts of such trafficking and with the protection of a victim's human rights.

- 7. Enforcement and prosecution of public officials—whether governments vigorously investigate, prosecute, convict, and sentence public officials who participate in or facilitate severe forms of trafficking in persons, as well as whether governments take all appropriate measures against officials who condone such trafficking.42

- 8. Foreign victims—whether noncitizen victims of severe forms of trafficking in persons are insignificant as a percentage of all victims in a country.43

- 9. Partnerships—whether governments have entered into effective and transparent partnerships, cooperative arrangements, or agreements that have resulted in concrete and measurable outcomes with the United States or other external partners.44

- 10. Self-monitoring—whether governments systematically monitor their efforts to satisfy certain above-listed criteria and publicly share periodic assessments of such efforts.45

- 11. Progress—whether governments achieve appreciable progress in eliminating severe forms of trafficking in persons, compared to the previous year's assessment.46

- 12. Demand reduction—whether governments have made serious and sustained efforts to reduce demand for commercial sex acts and international sex tourism.47

Factors for Evaluating Significant Efforts

Countries that are not compliant with the four minimum standards can avoid the worst (Tier 3) ranking if they are deemed to be making significant efforts to become compliant. In determining whether a government is making significant efforts to become compliant with the four minimum standards, the TVPA requires the Secretary of State to consider the following factors:

- the extent to which a country is a source, transit, or destination for severe forms of trafficking in persons;

- the extent of noncompliance with the minimum standards by the countries, including in particular whether public officials are involved in severe forms of trafficking in persons;

- what measures are reasonable, due to resource and capability constraints, to bring the government into compliance with the minimum standards;

- the extent to which the government is devoting sufficient budgetary resources to investigate acts of severe trafficking in persons, to investigate, prosecute, convict and sentence persons responsible, to obtain restitution for human trafficking victims, to protect and support human trafficking victims, and to prevent severe forms of trafficking in persons;48 and

- the extent to which the government has consulted with domestic and international civil society organizations and has taken concrete actions to improve the provision of services to human trafficking victims as a result.49

In addition, if the government itself exhibits patterns or policies of trafficking, forced labor, sexual slavery, or child soldiers, the Secretary of State is instructed to consider this as proof of a failure to make significant efforts.50

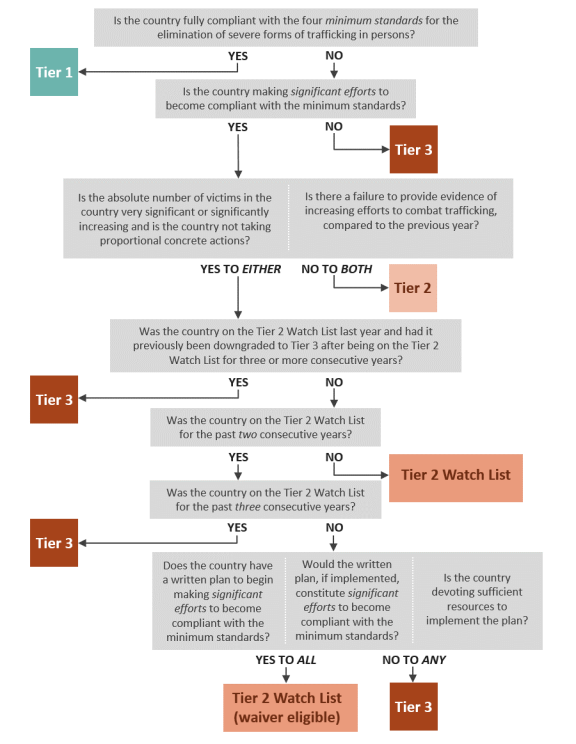

Country-Ranking Decision Flow

Taken in their entirety, the TVPA's prescribed standards and guidelines for country-ranking determinations, and its time duration restrictions and related waiver provisions for consecutive Tier 2 Watch List determinations, create a complex decision-flow process for determining each country's ranking (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Country-Ranking Decisions: Which Tier in the TIP Report? |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on the TVPA, as amended. |

Actions Against Governments Failing to Meet Minimum Standards

Aid Restrictions for Tier 3 Countries

The TVPA established that certain types of foreign assistance may not be provided to governments that are not committed to meeting the minimum standards for the elimination of severe forms of trafficking in persons (Tier 3 countries):

It is the policy of the United States not to provide nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related foreign assistance to any government that—

(1) does not comply with minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking; and

(2) is not making significant efforts to bring itself into compliance with such standards.51

The TVPA's provisions to restrict certain types of U.S. aid and certain other categories of U.S. and multilateral funding to Tier 3 countries began with the 2003 TIP Report. Funding subject to potential restriction includes nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related foreign assistance authorized pursuant to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, sales and financing authorized by the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and educational and cultural exchange funding, as well as loans and other funding provided by multilateral development banks and the International Monetary Fund.

Aid Authorized by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961

Nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related foreign assistance is defined in the TVPA as assistance authorized pursuant to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA) except for the following:52

- Assistance authorized under Chapter 4 of part II of the FAA (Economic Support Fund) in support of programs, projects, or activities conducted by nongovernmental organizations and eligible for Development Assistance under Chapter 1 of part I of the FAA.

- International Narcotics Control assistance authorized under chapter 8 of part I of the FAA.

- Any other counternarcotics assistance authorized under Chapters 4 or 5 of part II of the FAA (Economic Support Fund and International Military Education and Training), subject to certain congressional notification procedures.53

- Disaster relief assistance, including any assistance under Chapter 9 of part I of the FAA (International Disaster Assistance).

- Antiterrorism assistance authorized under Chapter 8 of part II of the FAA.

- Refugee assistance.

- Humanitarian and other development assistance in support of programs conducted by nongovernmental organizations under Chapters 1 and 10 of the FAA.54

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation programs authorized under Title IV of Chapter 2 of part I of the FAA.

- Other trade-related or humanitarian assistance programs.

Sales and Financing Authorized by the Arms Export Control Act

Pursuant to the TVPA, nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related foreign assistance subject to aid restriction also includes

- sales or financing on any terms authorized by the AECA—with the exception of sales or financing provided for narcotics-related purposes if congressionally notified.55

Funding for Educational and Cultural Exchanges

In the case of countries that do not receive such nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related foreign assistance, the TVPA authorizes the President to withhold funding for participation by officials or employees of Tier 3 countries in educational and cultural exchange programs.56

Loans and Other Funds Provided by Multilateral Development Banks and the International Monetary Fund

The TVPA authorizes the President to instruct the U.S. Executive Directors of each multilateral development bank and of the International Monetary Fund to vote against and otherwise attempt to deny loans or other uses of funds to Tier 3 countries.57

Presidential Determinations, Waivers, and Certifications

Between 45 and 90 days after submission of the annual TIP Report (due June 1), the TVPA requires the President to make a determination regarding whether and to what extent antitrafficking aid restrictions are to be imposed on Tier 3 countries during the following fiscal year.58 (See Table 2 below.) Typically issued near the beginning of the fiscal year and published in the Federal Register, the presidential determinations address the following:

- Applicability of aid restrictions—whether to withhold nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related assistance authorized by the FAA and the AECA, and whether to withhold funding for education and cultural exchanges and loans and other funds provided by multilateral development banks and the International Monetary Fund;

- Duplication of aid restrictions—whether ongoing, multiple, broad-based restrictions, comparable to those specified by the TVPA, on assistance in response to human rights violations are already in place;

- Subsequent compliance—whether the Secretary of State has found that the government of a Tier 3 country is now compliant with the minimum standards or is making significant efforts to become compliant; and

- National interest concerns—whether to continue assistance, in part or in whole, because it would promote the purposes of the TVPA or is otherwise in the national interest of the United States—including when the continuation of assistance is necessary to avoid significant adverse effects on vulnerable populations, such as women and children.

Pursuant to the TVPA, the President may selectively waive aid restrictions for national interest concerns, including by exercising a waiver for one or more specific programs, projects, or activities. Following the initial presidential determination required by the TVPA, as amended, the President may make additional determinations to waive, in part or in whole, aid restrictions on Tier 3 countries.59

As part of the President's determinations, the TVPA also requires the President to include a certification by the Secretary of State that no counternarcotics or counterterrorism assistance authorized by the FAA or arms sales and financing authorized by the AECA is intended to be received or used by any agency or official who has participated in, facilitated, or condoned a severe form of trafficking in persons.60

|

Fiscal Year |

Aid Restricted |

Full National Interest Waivers |

Partial National Interest Waivers |

Waivers Due to Subsequent Compliance |

|

FY2004 |

Burma, Cuba, North Korea |

none |

Liberia, Sudan |

Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Dominican Republic, Georgia, Greece, Haiti, Kazakhstan, Suriname, Turkey, Uzbekistan |

|

FY2005 |

Burma, Cuba, North Korea |

none |

Equatorial Guinea, Sudan, Venezuela |

Bangladesh, Ecuador, Guyana, Sierra Leone |

|

FY2006 |

Burma, Cuba, North Korea |

Ecuador, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia |

Cambodia, Venezuela |

Bolivia, Jamaica, Qatar, Sudan, Togo, United Arab Emirates |

|

FY2007 |

Burma, Cuba, North Korea |

Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Uzbekistan |

Iran, Syria, Venezuela, Zimbabwe |

Belize, Laos |

|

FY2008 |

Burma, Cuba |

Algeria, Bahrain, Malaysia, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Uzbekistan |

Iran, North Korea, Syria, Venezuela |

Equatorial Guinea, Kuwait |

|

FY2009 |

Burma, Cuba, Syria |

Algeria, Fiji, Kuwait, Papua New Guinea, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan |

Iran, North Korea |

Moldova, Oman |

|

FY2010 |

Cuba, North Korea |

Chad, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mauritania, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan |

Burma, Eritrea, Fiji, Iran, Syria, Zimbabwe |

Swaziland |

|

FY2011 |

Eritrea, North Korea |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Dominican Republic, Kuwait, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan |

Burma, Cuba, Iran, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2012 |

Eritrea, Madagascar, North Korea |

Algeria, Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Turkmenistan, Yemen |

Burma,a Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Iran, Venezuela, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2013 |

Cuba, Eritrea, Madagascar, North Korea |

Algeria, Central African Republic, Kuwait, Libya, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Iran, Sudan, Syria, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2014 |

Cuba, Iran, North Korea |

Algeria, Central African Republic, China, Guinea-Bissau, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Uzbekistan, Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Syria, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2015 |

Iran, North Korea, Russia |

Algeria, Central African Republic, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, Uzbekistan, Yemen |

Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Syria, Venezuela, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2016 |

Iran, North Korea |

Algeria, Belarus, Belize, Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Kuwait, Libya, Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Thailand |

Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Russia, South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2017 |

Iran, North Korea |

Algeria, Belarus, Belize, Burma, Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Djibouti, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, Suriname, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Russia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, Zimbabwe |

none |

|

FY2018 |

Iran, North Korea |

Belarus, Belize, Burundi, Central African Republic, China, Comoros, Republic of Congo, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Mauritania, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Russia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela |

none |

|

FY2019 |

Bolivia, Burma, Burundi, China, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Iran, North Korea, Laos, Mauritania, Russia, South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela |

Belarus, Turkmenistan |

Belize, Eritrea, Papua New Guinea |

none |

|

FY2020 |

Burundi, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, The Gambia, Iran, North Korea, Mauritania, Russia, Syria |

Belarus, Bhutan, Comoros, Papua New Guinea, Turkmenistan, Venezuela |

Burma, Democratic Republic of Congo, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan |

TBD |

Sources: Determination of the President of the United States, Nos. 2003-35 (68 FR 53871), 2004-46 (69 FR 56155), 2005-37 (70 FR 57481), 2006-25 (71 FR 64431), 2008-4 (72 FR 61037), 2009-5 (73 FR 63839), 2009-29 (74 FR 48365), 2010-15 (75 FR 67017, 68411), 2011-18 (76 FR 62599), 2012-16 (77 FR 58921, as amended by 77 FR 61046), 2013-16 (78 FR 58861), 2014-16 (79 FR 57699), 2016-01 (80 FR 62435), 2016-12 (81 FR 70311), 2017-15 (82 FR 50047), 2019-05 (83 FR 65281); The White House, "Presidential Memorandum on Determination with Respect to the Efforts of Foreign Governments Regarding Trafficking in Persons," October 18, 2019.

a. Indicates that following the President's delegation of authority on February 3, 2012 (see 77 FR 11375), the Secretary of State revised Presidential Determination No. 2011-18 on February 6, 2012, to waive prohibitions on U.S. support for assistance to Burma through international financial institutions. See U.S. Department of State Public Notice No. 7799 (77 FR 9295). Other residential delegations of authority were issued on July 29, 2013, for Syria (78 FR 48027) and on October 5, 2015, for Yemen (78 FR 6505).

Trade Restrictions for Tier 3 Countries

Pursuant to the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA), as amended, trade authorities procedures may not apply to any implementing bill submitted with respect to an international trade agreement involving the government of a country listed as Tier 3 in the most recent annual TIP Report.61 The trade authorities procedures described in the TPA are critical for the fast-tracking of international trade agreements, such as a free trade agreement.

The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 created an exception to the TPA's initial prohibitions.62 This exception authorizes trade agreement negotiations to proceed with Tier 3 countries, but only if the President specifies in a letter to appropriate congressional committees that the country in question has taken "concrete actions to implement the principal recommendations with respect to that country in the past recent annual report on trafficking in persons."63 The letter must include a description of the concrete actions and supporting documentation of credible evidence of each concrete action (e.g., copies of relevant laws, regulations, and enforcement actions taken, as appropriate). Moreover, the letter must be made available to the public.

|

Other Requirements Related to Noncompliant Countries Amendments to the TVPA in 2019 created new additional requirements related to noncompliant countries. State Department Communications with Certain Watch List Countries. Pursuant to amendments made by the 2017 TVPRA, for countries that were upgraded from Tier 3 to the Tier 2 Watch List in the latest TIP Report, no later than 180 days after the report's release, the State Department is to develop and present to the country's government an action plan for further improving the country's ranking. Action plans shall include concrete actions that the government can take to address deficiencies in order to meet Tier 2 standards, and include short-term and multi-year goals.64 A separate provision pertaining to countries that were downgraded to the Tier 2 Watch List requires that the Secretary of State "not less than annually" provide the foreign minister of each such country a copy of the TIP Report and information relating to the country's downgrade, including steps that the country must take to be considered for a Tier ranking upgrade (among other required elements).65 USAID Strategies. Pursuant to amendments made by the 2018 TVPPRA, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is to integrate child protection and trafficking risk reduction strategies into its development strategies for Tier 3 and Tier 2 Watch List countries. USAID is to develop strategies for these countries to "address the root causes of insecurity" that leave children vulnerable to trafficking, and that monitor progress to prevent and address violence against children in post-conflict and post-disaster areas.66 |

Security Assistance Restrictions for Child Soldier Countries

Pursuant to the CSPA, as amended, countries listed in the most recent TIP Report as having recruited or used child soldiers are prohibited from participating in certain types of security assistance and cooperation activities.67 These restrictions include

- licenses for direct commercial sales of military equipment;

- foreign military financing for the procurement of defense articles and services, as well as design and construction services;68

- excess defense articles;69

- international military education and training;70 and

- peacekeeping operations and other programs.71

Presidential waiver determinations relating to CSPA restrictions have also referenced some Department of Defense (DOD) security cooperation authorities that by law cannot be utilized if they are "otherwise prohibited by any provision of law" as being potentially restricted by the CSPA. This has included DOD's "train and equip" authority for building the capacity of foreign defense forces, now codified at 10 U.S.C. 333.72

Other forms of U.S. security assistance to CSPA-listed countries may continue to be provided under the law, although constraints may be applied as a matter of policy.

Exceptions and Presidential Determinations, Certifications, and Waivers

CSPA security assistance restrictions may not apply if one of four circumstances is invoked.73

- Peacekeeping exception. Assistance may continue to child soldier countries for peacekeeping operations that support military professionalization, security sector reform, heightened respect for human rights, peacekeeping preparation, or the demobilization and reintegration of child soldiers.

- International military education and training and nonlethal supplies exception. Assistance for international military education and training may be provided through the Defense Institute for International Legal Studies or the Center for Civil-Military Relations at the Naval Post-Graduate School, and nonlethal supplies to child solider countries may continue for up to five years, if the President certifies to appropriate congressional committees that (1) such assistance will directly support professionalization of the military; and (2) the country is taking "reasonable steps to implement effective measures to demobilize child soldiers ... and is taking reasonable steps in the context of its national resources to provide demobilization, rehabilitation, and reintegration assistance to those former child soldiers."74

- National interest waiver. The President may waive the CSPA security assistance restrictions if the President determines that such a waiver is in the national interest of the United States and certifies to the appropriate congressional committees that the country's government is "taking effective and continuing steps to address the problem of child soldiers."75 The President is to notify the appropriate committees of the waiver and the justification within 45 days of granting a waiver. Presidential determinations concerning waivers are typically published in the Federal Register near the beginning of the fiscal year. (See Table 3 below.).

- Reinstatement certification. Security assistance otherwise prohibited by the CSPA may be reinstated if the President certifies to appropriate congressional committees that the government of the listed country has (1) implemented measures, including an action plan and actual steps to stop recruiting and using child soldiers, and (2) implemented policies and mechanisms to prohibit and prevent future recruitment or use of child soldiers.

Table 3. Aid Restrictions and Waivers to Child Soldier Countries, Pursuant to the CSPA, FY2011-FY2020

|

Fiscal Year |

Aid Restricted |

Full National Interest Waivers |

Partial National Interest Waivers |

Waivers Due to Subsequent Compliance |

|

FY2011 |

Burma, Somalia |

Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Yemen |

none |

none |

|

FY2012 |

Burma, Somalia, Sudan |

Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

Chad |

|

FY2013 |

Burma, Sudan |

Libya, South Sudan, Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Somaliaa |

none |

|

FY2014 |

Burma, Central African Republic, Rwanda, Sudan, Syria |

Chad, South Sudan, Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia |

none |

|

FY2015 |

Burma, Sudan, Syria |

Rwanda, Somalia, Yemen |

Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan |

none |

|

FY2016 |

Burma, Sudan, Syria, Yemen |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Somalia |

South Sudan |

none |

|

FY2017 |

Sudan, Syria, Yemen |

Burma, Iraq, Nigeria |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan |

none |

|

FY2018 |

Sudan, Syria |

Mali, Nigeria |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Yemenb |

none |

|

FY2019 |

Burma, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Syria |

Iraq, Mali, Niger, Nigeria |

Somalia, South Sudan, Yemen |

none |

|

FY2020 |

Burma, Iran, Sudan, Syria |

Afghanistan, Iraq |

Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, Yemen |

TBD |

Sources: Determination of the President of the United States, Nos. 2011-4 (75 FR 75855), 2012-01 (76 FR 65927), 2012-18 (77 FR 61509), 2013-17 (78 FR 63367), 2014-18 (79 FR 69755), 2015-13 (80 FR 62431), 2016-14 (81 FR 72683), 2017-14 (82 FR 49085), 2018-13 (83 FR 53363); The White House, "Presidential Determination and Certification with Respect to the Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008," October 18, 2019.

a. Following the President's delegation of authority on August 2, 2013 (see 78 FR 72789), the Secretary of State revised Presidential Determination No. 2012-18 on August 14, 2013, to partially waive restrictions on Somalia to allow for assistance under the Peacekeeping Operations authority for logistical support and troop stipends in FY2013. This State Department decision was not published in the Federal Register.

b. In at least two instances, the President has delegated authority to the Secretary of State to make additional CSPA determinations with respect to Yemen: on September 29, 2015 (80 FR 62429), and on September 28, 2016 (81 FR 72681). In August 2018, the Secretary of State partially waived FY2018 restrictions on Yemen to allow for assistance under the Peacekeeping Operations authority. This State Department decision was not published in the Federal Register.

Reporting Requirements for Exceptions and Waivers

The President is required to submit an annual report to the appropriate congressional committees that includes the list of countries notified that they were listed as a child soldier country pursuant to the CSPA (all listed countries are to be notified of their inclusion of the list); descriptions and amounts of any assistance withheld; a list of waivers or exceptions exercised and justifications for each waiver and exception; and descriptions and amounts of any assistance provided as a result of waivers or exceptions. The report is to be submitted by June 15 of the following year and, pursuant to the CSPA of 2018, is also to be included in the TIP Report.76

Impacts of Restrictions and Waivers

The prospect of aid and other restrictions against Tier 3 countries and child soldier countries may work to create greater incentives for countries to improve their antitrafficking efforts. To the extent that this approach can be expected to be effective (a punitive approach cannot address capacity issues on the part of the government in question, for example), it is arguably undermined by the executive branch's use of waivers, a practice that has sometimes drawn criticism from some Members of Congress. On the other hand, the use of waivers allows the executive branch to balance the desire to push for antitrafficking improvements against potential unintended human security consequences or negative impacts on other foreign policy goals.

The Trump Administration has generally provided fewer waivers for Tier 3 countries than had prior Administrations. President Trump opted not to provide any waivers for FY2019 assistance for 17 Tier 3 countries (see Table 2), thereby restricting assistance to more countries than had been restricted by any prior determination since the TVPA's passage. The Administration described the decision as "strong action … to hold accountable those governments that have persistently failed to meet the minimum standards for combating human trafficking in their countries," and declared that "this administration will no longer use taxpayer dollars to support governments that consistently fail to address trafficking."77 The decision reportedly delayed some aid programs and created confusion among aid organizations concerning which programs are impacted.78 Some Members of Congress criticized in particular the impact on programs to combat Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They noted, for example, that the Administration appeared to be applying restrictions to aid implemented by nongovernmental organizations, and that the TVPA also explicitly justifies a presidential waiver for the purpose of avoiding significant adverse effects to vulnerable populations.79 For FY2020, the President fully restricted assistance to 11 Tier 3 countries, while also providing a broad national interest waiver for any "programs, projects, activities, and assistance to respond to the threat posed by the Ebola virus disease."80

|

Security Assistance Restrictions in Appropriations FY2019 appropriations for the Department of State and Department of Defense contained provisions that additionally prohibit certain types of security assistance from being used to support military training or operations that involve child soldiers. Similar provisions have also been included in prior appropriations measures in recent years.

|

TIP Report Methodology

The TVPA created the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (J/TIP) within the State Department, whose director holds the rank of Ambassador-at-Large.83 The J/TIP director is charged with overseeing the annual publication of the TIP Report, among other responsibilities laid out in the TVPA. In parallel to the drafting of the introductory material and the country narratives, the department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) initiates the process for identifying countries to be included in the list of governments that recruit and use child soldiers. Each TIP Report is to cover country developments beginning in April of the preceding year each year and ending in March of the year of the report's issuance.84

Report Release

Although not required by law, the State Department has always publicly released the report and the Secretary of State has personally presided over its launch. The report, however, has never been published by its statutory June 1 deadline.85 In addition to the statutory deadline for the annual release of the report, current law includes two other provisions related to the TIP Report's release:

- Translation requirement. Pursuant to the Advance Democratic Values, Address Nondemocratic Countries, and Enhance Democracy Act of 2007, the Secretary of State is required to "expand the timely translation" of the TIP Report, among other reports prepared by the State Department.86 Current law further specifies that the TIP Report is to be translated "into the principal languages of as many countries as possible, with particular emphasis on nondemocratic countries, democratic transition countries, and countries in which extrajudicial killings, torture, or other serious violations of human rights have occurred."87

- Award ceremony. Pursuant to the TVPA reauthorization of 2008, the timing of the TIP Report's release corresponds to a requirement for the Secretary of State to host an annual ceremony for recipients of the Presidential Award for Extraordinary Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons.88 Current law provides that the Secretary-hosted ceremony occur "as soon as practicable after the date on which the Secretary submits to Congress the [TIP R]eport...."89

|

What Other Required Reports Address International Human Trafficking Matters? Congress requires the executive branch to prepare and submit several other reports that address, at least in part, human trafficking matters. These include reports prepared by the Departments of State, Justice, and Labor.

|

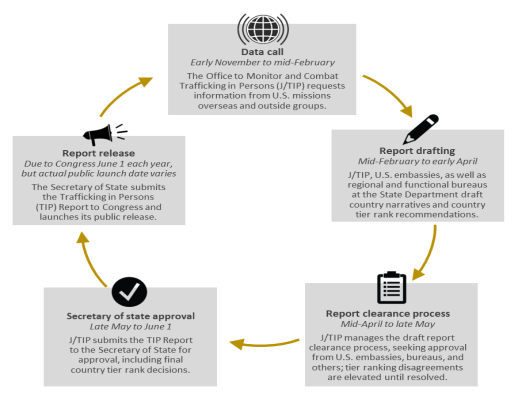

Illustrative Draft Cycle

The annual process for drafting and releasing the TIP Report involves a period of worldwide information gathering, followed by an intense process of report drafting, led by J/TIP, but involving significant input from U.S. diplomatic missions and consular posts overseas as well as regional and functional bureaus (see Figure 4). According to the State Department's Office of Inspector General (OIG), the annual rush to meet the report's statutory release deadline may increase tensions over disagreements between bureaus and J/TIP regarding the draft country narratives and proposed tier rankings.93

Over time, the report draft cycle has evolved. Beginning with preparations for the 2010 TIP Report, for example, the State Department began to issue annual notices in the Federal Register, requesting information from nongovernmental groups on whether governments meet the TVPA's minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking.94 A 2012 OIG inspection report of the J/TIP Office identified several other internal process changes that resulted in a significant reduction of tier ranking disputes.95

|

|

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Human Trafficking: State Has Made Improvements in Its Annual Report but Does Not Explicitly Explain Certain Tier Rankings or Changes, GAO-17-56, December 2016, and U.S. Department of State and the Broadcasting Board of Governors, Office of Inspector General, Inspection of the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, ISP-I-12-37, June 2012. |

Information Sources

According to the State Department, information used to prepare the report is based on a variety of sources, including U.S. embassies, government officials, nongovernmental and international organizations, published reports, news articles, academic studies, and research trips. U.S. diplomatic posts and domestic agencies report on human trafficking issues throughout the year and the TIP Report incorporates information based on meetings with government officials, local and international nongovernmental representatives, officials of international organizations, journalists, academics, and survivors.

Global Law Enforcement Data

Pursuant to the TVPA reauthorization of 2003, Congress added a new criterion for governments to achieve full compliance with the minimum standards for the elimination of severe forms of trafficking in persons: providing the State Department with data on trafficking investigations, prosecutions, convictions, and sentences.96 Beginning with the 2004 TIP Report, the State Department has included this information in its TIP Reports—on a country-by-country basis, as well as in aggregate on a global and regional basis (see Figure 5).

Human Trafficking Trends

An implicit objective of the TVPA was to leverage the country-ranking process of the TIP Report to motivate foreign governments to prioritize and address human trafficking. Some suggest the TIP Report can be used as a potent form of soft power, both as a "name-and-shame" or "blacklist" process and as a mechanism for country-by-country monitoring of antitrafficking progress. Research has indicated that the TIP Report, and potentially other reports like it, may mobilize domestic and international pressure for policy change.97 However, while some countries appear to be responsive to the TIP Report, others remain intractable. In the 2019 TIP Report, more than 80% of the 187 ranked countries remained noncompliant with the minimum standards laid out by the TVPA for eliminating trafficking in persons.

Pathways to the Top. Several countries' rankings have improved from Tier 3 to Tier 1:

- Bahrain was rated Tier 3 in 2001 and 2002 before eventually achieving a Tier 1 rating for the first time in 2018.

- Guyana was rated Tier 3 in 2004 and experienced multiple years on the Tier 2 Watch List before attaining a Tier 1 rating for the first time in 2017.

- Israel was rated Tier 3 in 2001 and eventually improved to Tier 1 by 2012.

- South Korea was rated Tier 3 in 2001 and immediately improved to Tier 1 the following year.

Progress in Reverse. Other countries that used to be fully compliant with the minimum standards to eliminate trafficking (Tier 1) have since become noncompliant, including, for example, the following:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina began as a Tier 3 country in 2001 and attained Tier 1 status in 2010, but has been rated as either Tier 2 or Tier 2 Watch List every year since then (it was Tier 2 Watch List in 2019).

- Denmark, Germany, Italy, and Poland, which had previously been rated as Tier 1 countries nearly every consecutive year since the TIP report's inception, were all ranked as Tier 2 in the 2019 TIP Report.98

- Hungary, which attained Tier 1 status in 2007, but dropped to Tier 2 Watch List in 2017 and has remained there since.

- Malawi, which was ranked Tier 1 in 2006 and 2007, but has since been rated as either Tier 2 or Tier 2 Watch List (it was Tier 2 Watch List in 2019).

- Mauritius began as a Tier 1 country in 2003 and has since vacillated between compliant and noncompliant. After dropping to Tier 2 Watch List in 2015, it rose to Tier 2 in 2016, where it has remained since.

- Nicaragua was rated as Tier 1 from 2012 to 2014 but dropped to Tier 2 in 2015 and then to Tier 2 Watch List in 2017, where it has remained.

- Nepal attained Tier 1 status in 2005, but has since been rated Tier 2.

No Change. The rankings of several other countries have been unchanged.

- Unchanged Tier 1: Australia, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States.99

- Unchanged Tier 2: El Salvador, Kosovo, Palau, and Uganda.100

- Unchanged Tier 3: Eritrea and North Korea.101

Of the 38 countries on the Tier 2 Watch List in the 2019 TIP Report, 18 had been on the Tier 2 Watch List in 2018, and 7 required waivers to remain on the Tier 2 Watch List for their third consecutive year (see Table 1).

Criticisms and Alternatives to the TIP Report

Although many observers view the TIP Report as a credible reflection of global efforts to address human trafficking, others criticize the methodology behind the rankings.

Lack of Consistent and Transparent Evaluations

Some observers have been critical of the methodology used to evaluate foreign country efforts and assign tier rankings. In a 2012 report from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), the TIP Report was praised as having "gained wide credibility for its thoroughness" and "recognized as the definitive work by the anti-trafficking community on the status of anti-trafficking efforts."102 The OIG report, however, also noted other countries' arguments that "the U.S. Government's annual assessment is flawed and its tier-ranking system subjective."

In December 2016, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report assessing the State Department's TIP Report and country-ranking procedures.103 The GAO report assessed that the State Department lacked consistent and explicit explanations to justify upgrades and downgrades, which the report found problematic. It stated: "The lack of an explicit explanation for most of State's decisions to upgrade or downgrade countries to a different tier could limit the ability of internal and external stakeholders to understand the justification for tier changes and, in turn, use the report as a diplomatic tool to advance efforts to combat trafficking."104 (A January 2019 amendment to the TVPA to require concrete justifications for tier ranking changes is aimed at addressing these concerns—see "Justifications for Country-Ranking Changes" above.)

Some country rankings, initially proposed by J/TIP in early drafts of the TIP Report, have reportedly been disputed by other parts of the State Department, including regional bureaus and senior leadership. According to the 2012 OIG Report, "the number of tier-ranking disputes between regional bureaus and J/TIP declined from 46 percent of all countries ranked in 2006 to 22 percent of those ranked in 2011."105 No comprehensive analysis has yet been published documenting the number of such disputes in the years since then.

Political Motivation Behind Rankings

Some observers allege that political considerations influence rankings and that countries may be downgraded due partly to a reticence to share information with the United States. On August 3, 2015, a Reuters news article reported that tier-ranking disputes for 2015 TIP Report involved 17 countries and that the J/TIP Office "won only three of those disputes, the worst ratio in the 15-year history of the unit."106 The article indicated that countries whose rankings were disputed included China, Cuba, India, Malaysia, Mexico, and Uzbekistan—all of which reportedly received better rankings than the J/TIP Office had recommended.

In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in July 2017, then-J/TIP Director and Ambassador-at-Large Susan Coppedge declined to identify the specific number of tier-ranking disputes that preceded the release of the 2016 TIP Report. She stated, however, that the "vast majority" of the State Department's staff recommendations to the Secretary of State—encompassing those of J/TIP and the regional bureaus—were consensus recommendations.107 In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the 2017 TIP Report, Coppedge noted that department staff could not agree on five countries' tier rankings.108

In 2017, Reuters reported that then-Secretary of State Tillerson chose not to include Burma, Afghanistan, and Iraq on the child soldiers list despite reports that children had been in the ranks of the armed forces and/or government-affiliated militias in those countries; the decision reportedly prompted internal protest via the State Department's dissent channel.109 According to Reuters, an anonymous official stated that Tillerson's decision to leave Iraq and Afghanistan off the list appeared to have been "made following pressure from the Pentagon to avoid complicating assistance to the Iraqi and Afghan militaries." On June 18, 2019, a Reuters article reported that Secretary of State Pompeo had chosen not to include Saudi Arabia on the child soldier's list over the objection of J/TIP officials.110 The 2019 TIP Report noted reports that Saudi Arabia had provided salaries, training, and other support to "Sudanese combatants which included children aged 14-17 years old, who may have been used in direct hostilities in Yemen;" according to J/TIP Director and Ambassador-at-Large John Cotton Richmond, the department determined that that information was not sufficient to warrant Saudi Arabia's inclusion on the child soldiers list.111 According to the Reuters article, some human rights advocates attributed the decision to political pressure to maintain the U.S.-Saudi relationship.112

|

Case Study: Alleged Political Influence in Malaysia's Ranking in the 2015 and 2016 TIP Reports Many observers alleged that Malaysia's rankings in the 2015 and 2016 TIP Reports were influenced by factors unrelated to the Malaysian government's efforts to eradicate human trafficking. After four consecutive years on the Tier 2 Watch List from 2010 through 2013, Malaysia was downgraded in 2014, as required by law, to Tier 3 for lack of significant progress to combat human trafficking. In 2015 and 2016, however, the State Department ranked Malaysia as a Tier 2 Watch List country (see Figure 6 below).